Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

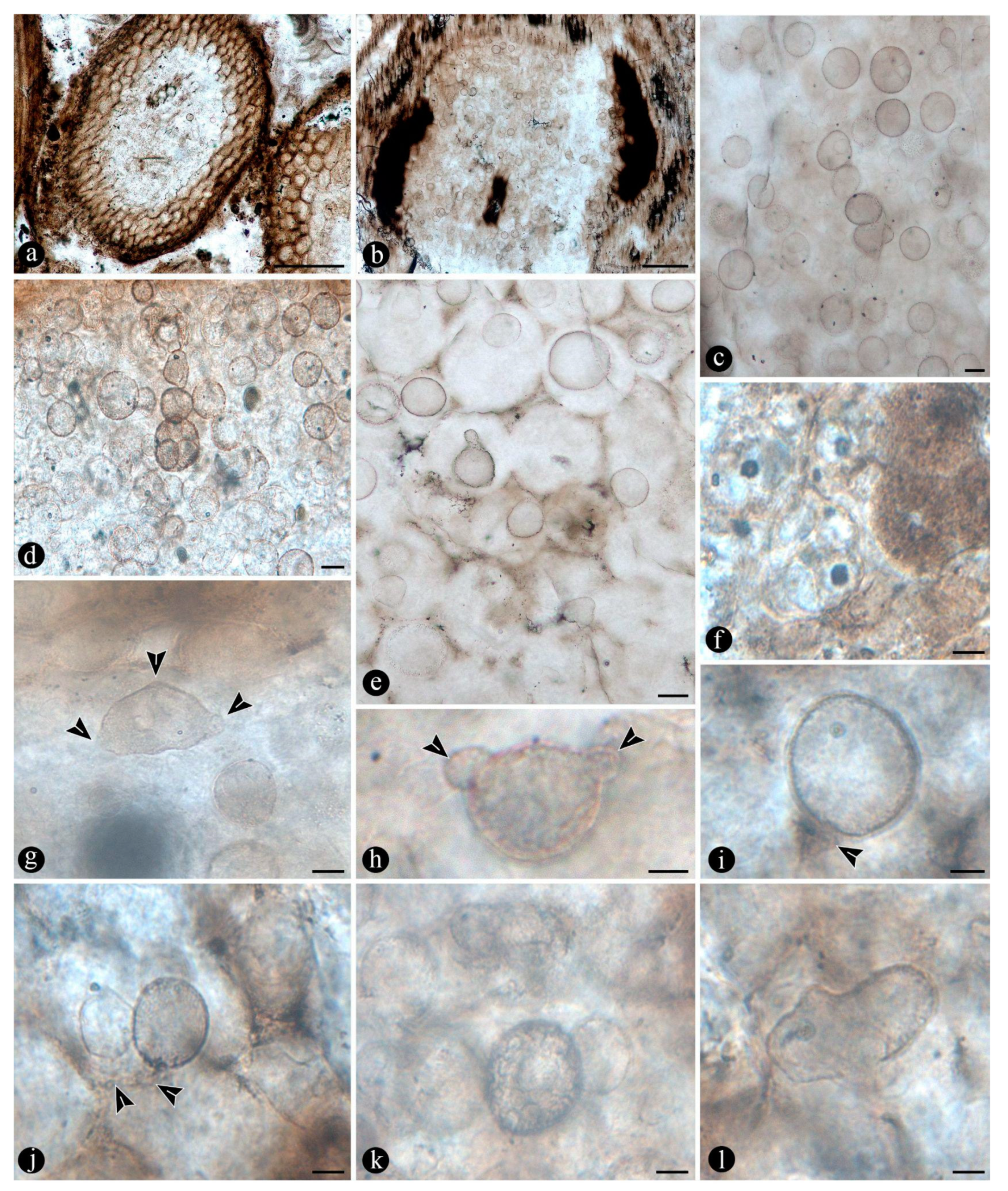

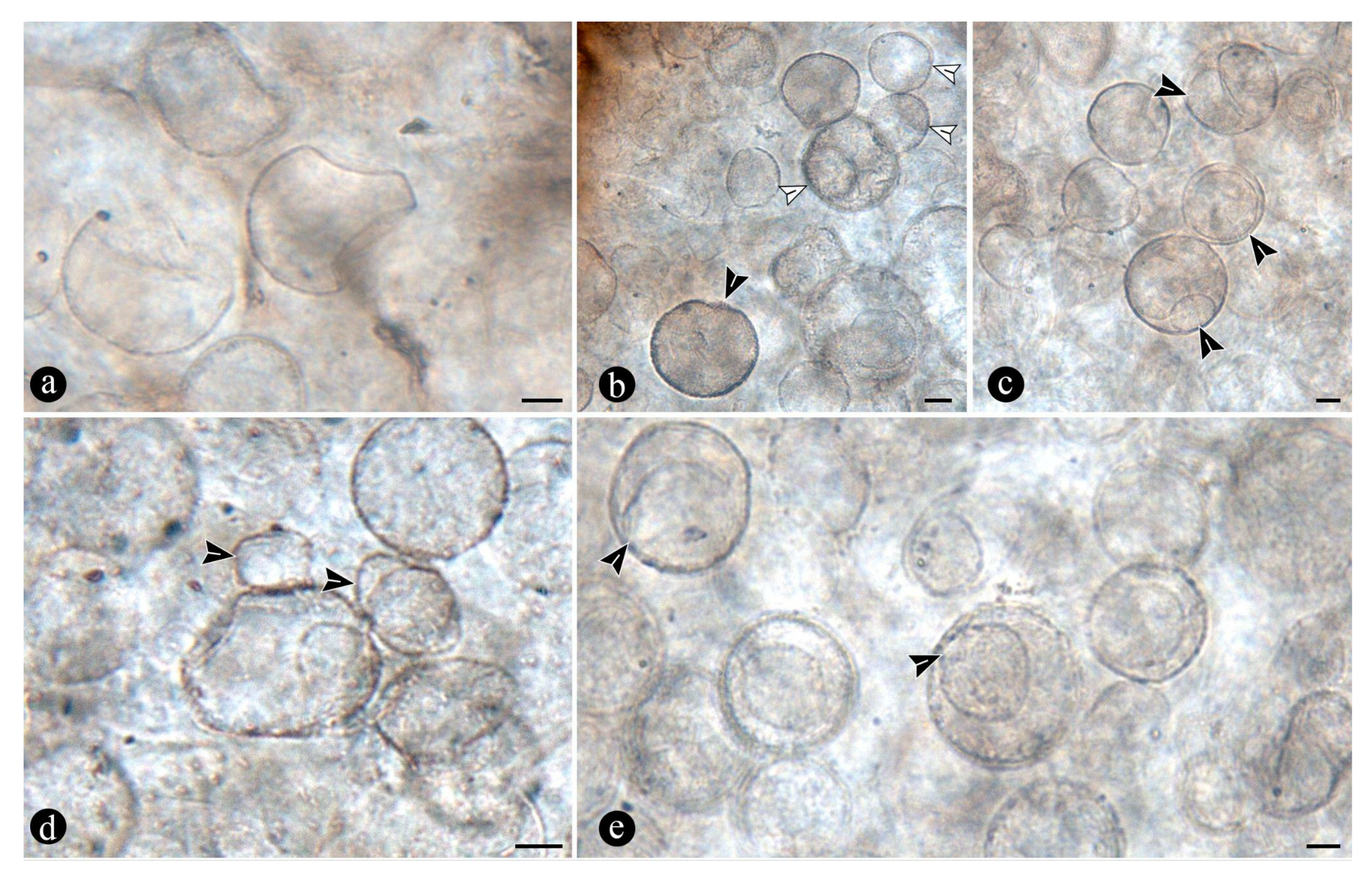

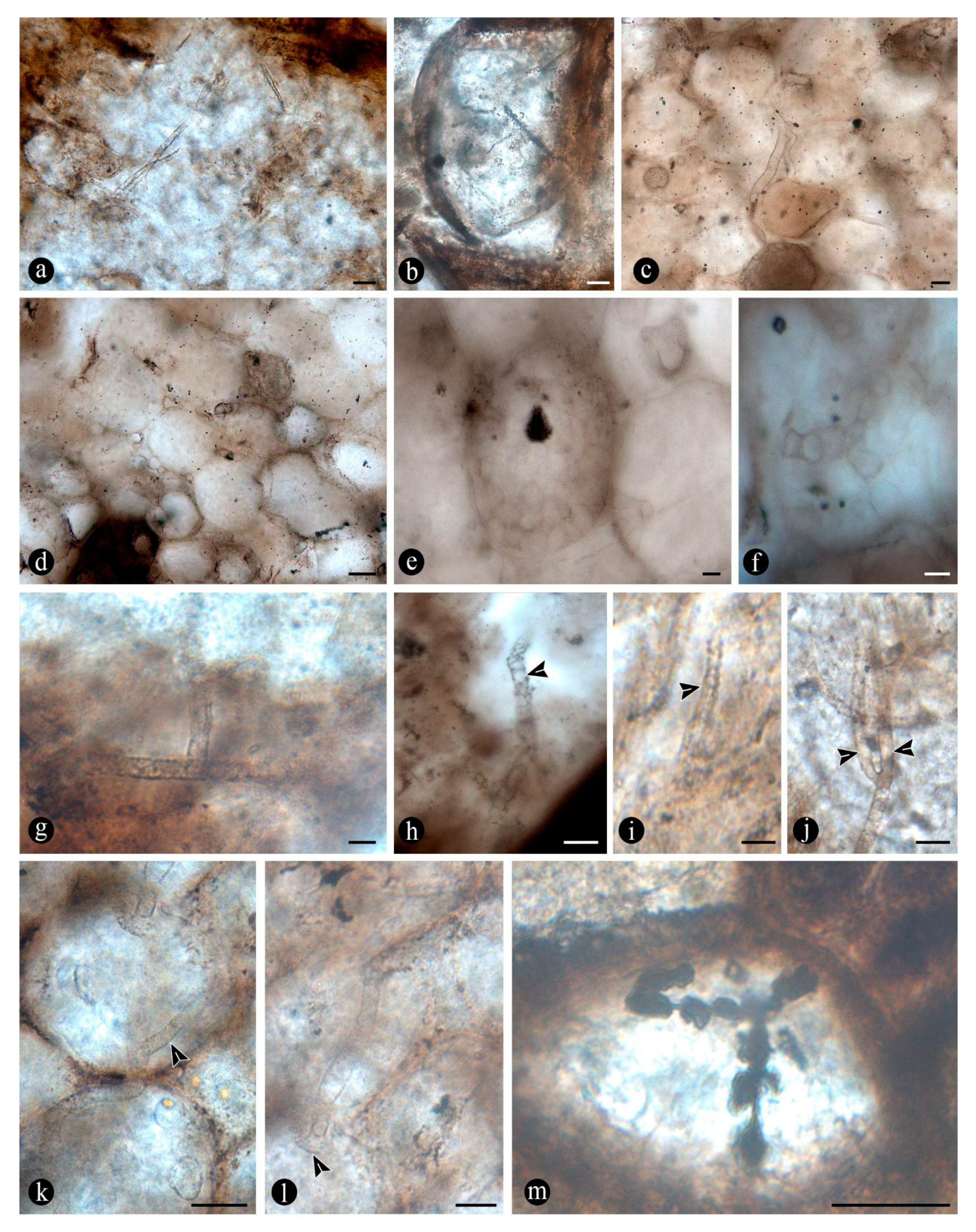

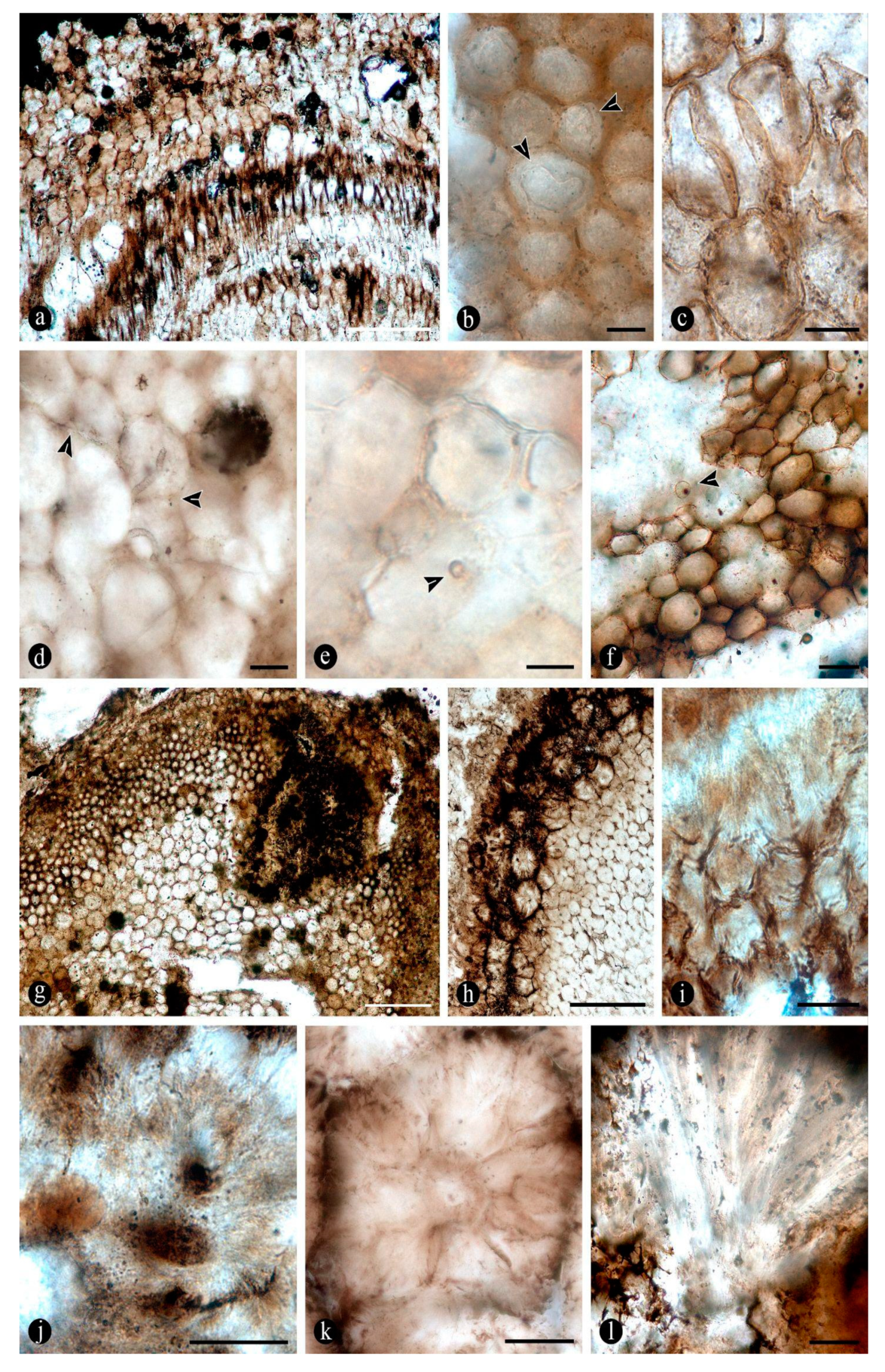

2. Results

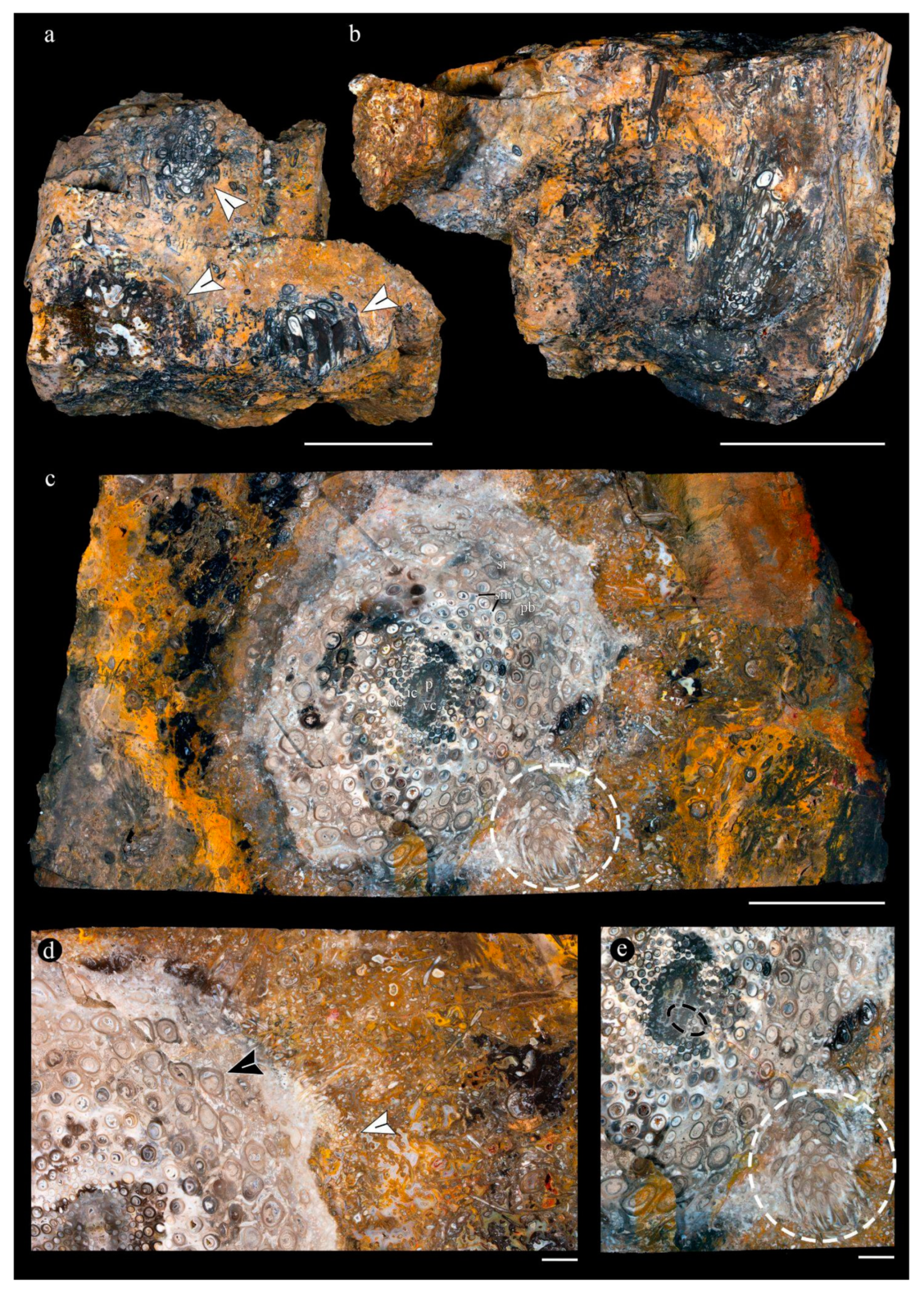

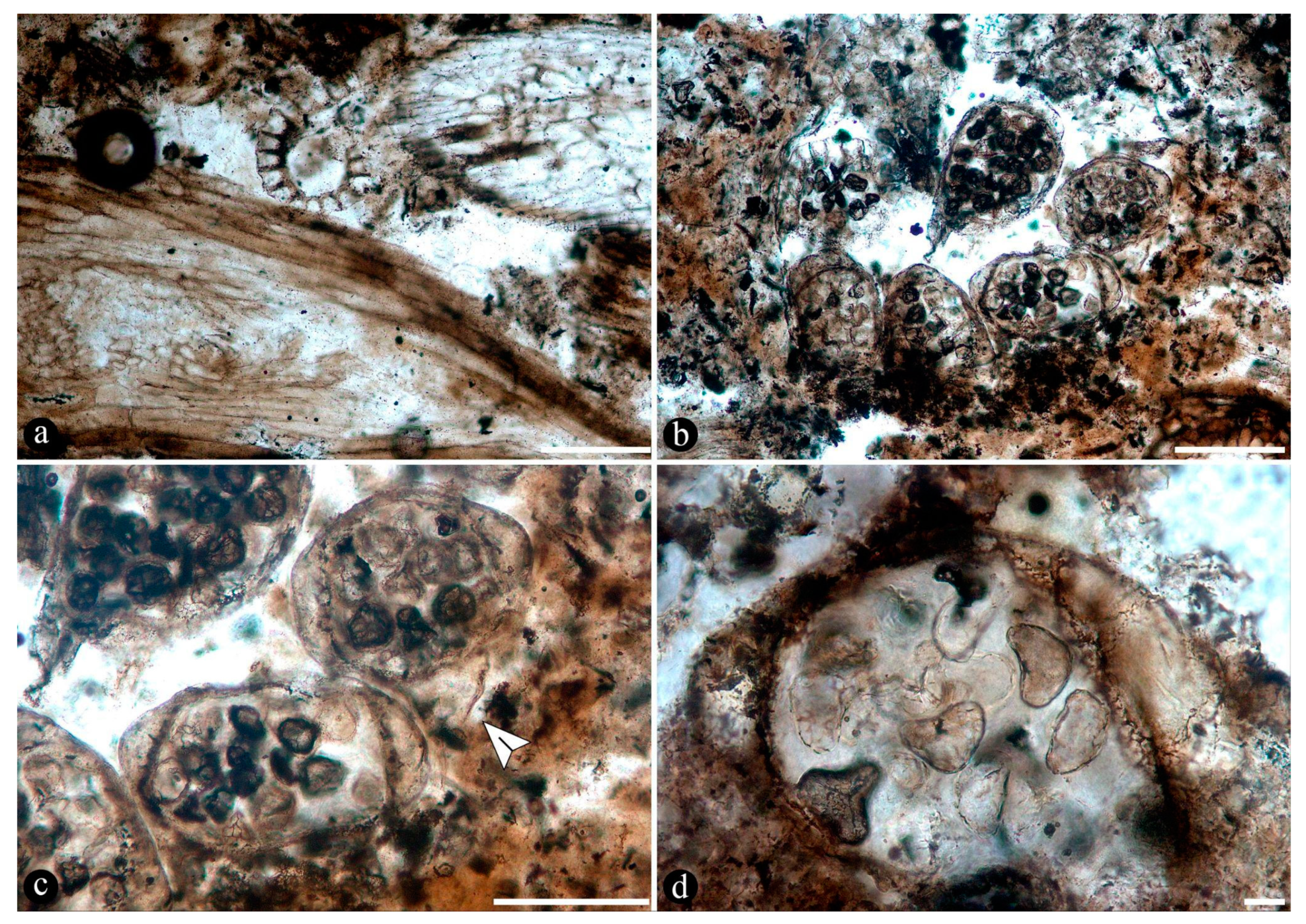

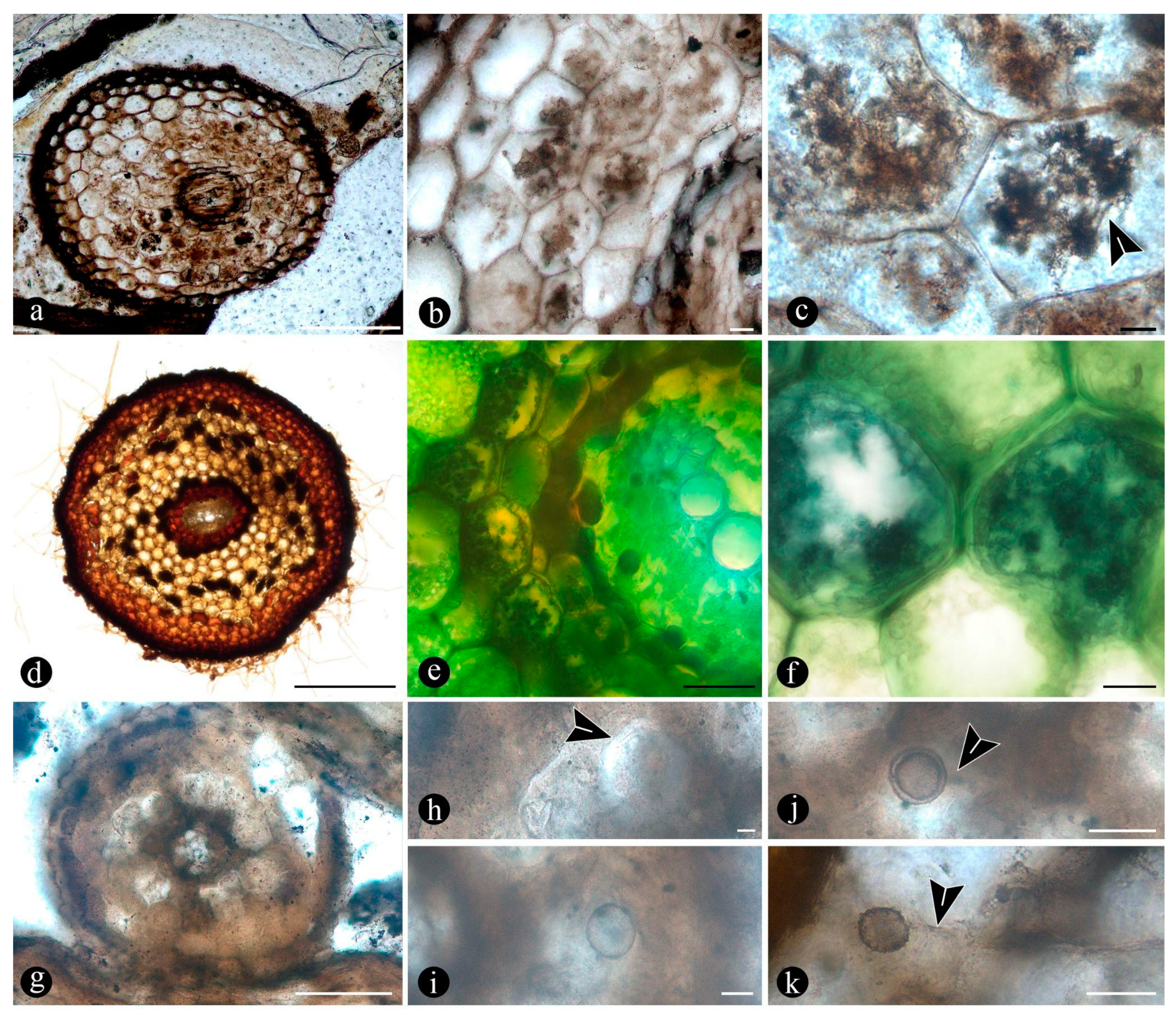

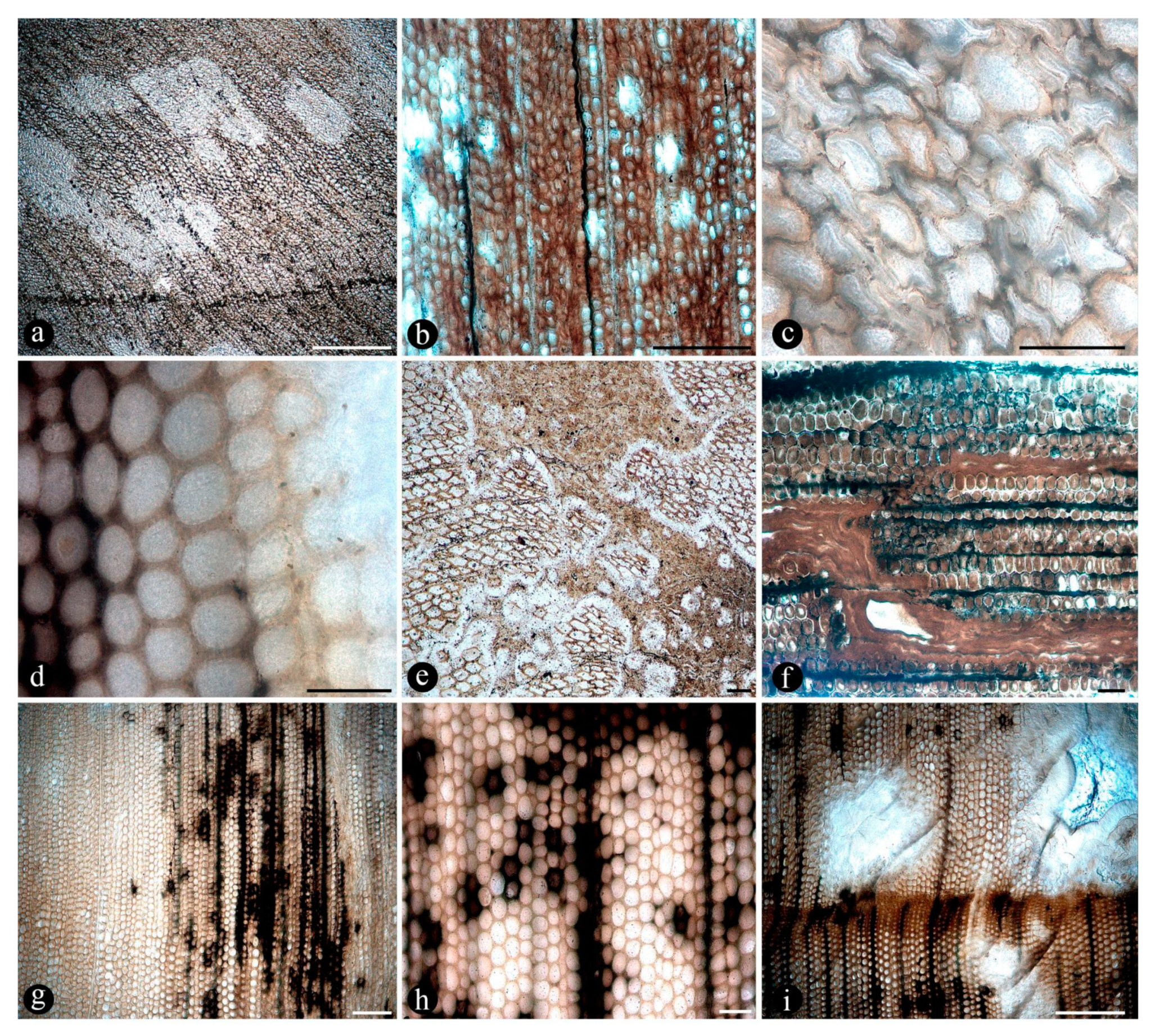

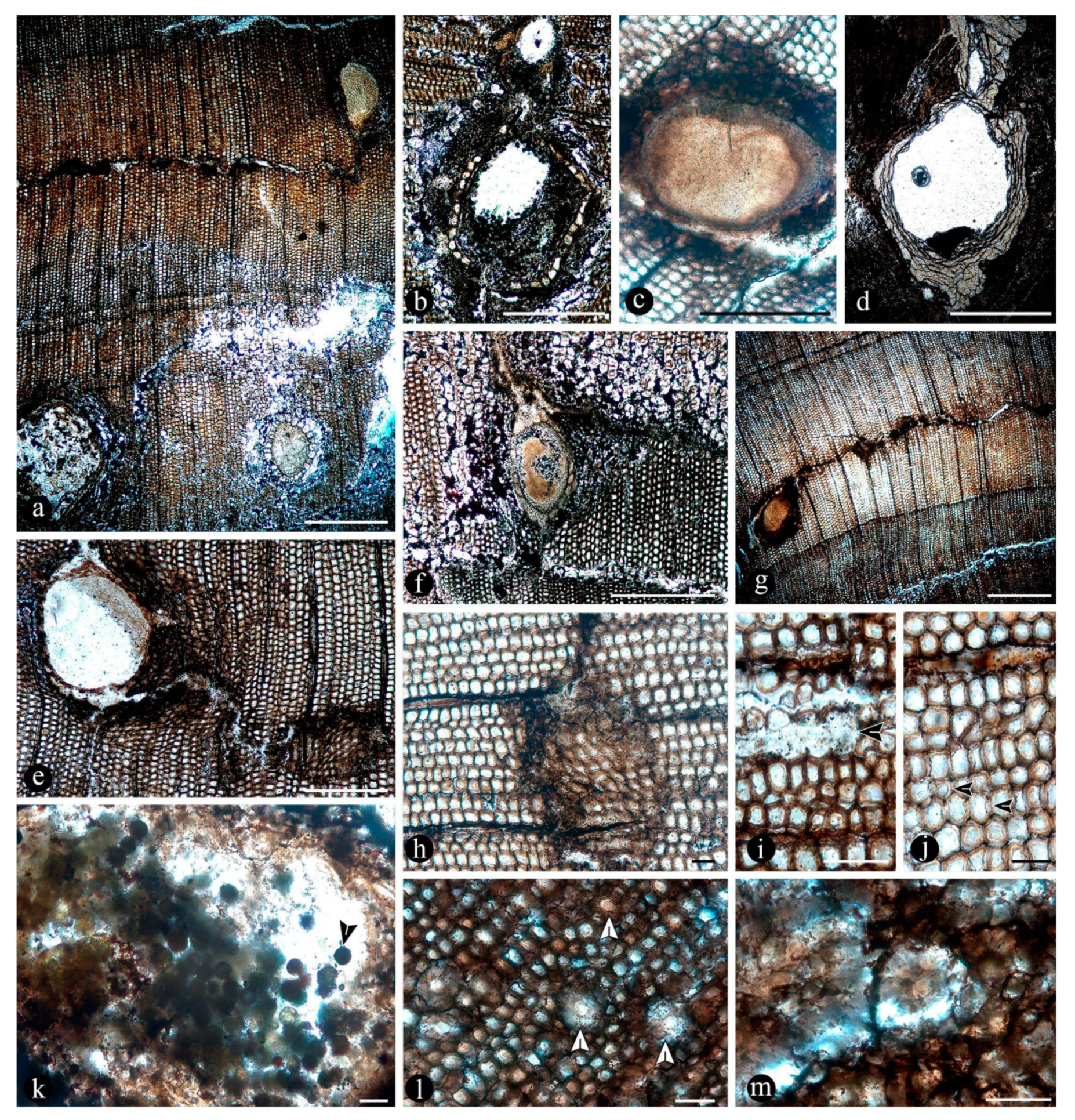

2.1. Composition of the Main Chert Blocks (Includes Spatial Arrangement and Habit Within Individual Cherts and Relationships Among Chert Blocks)

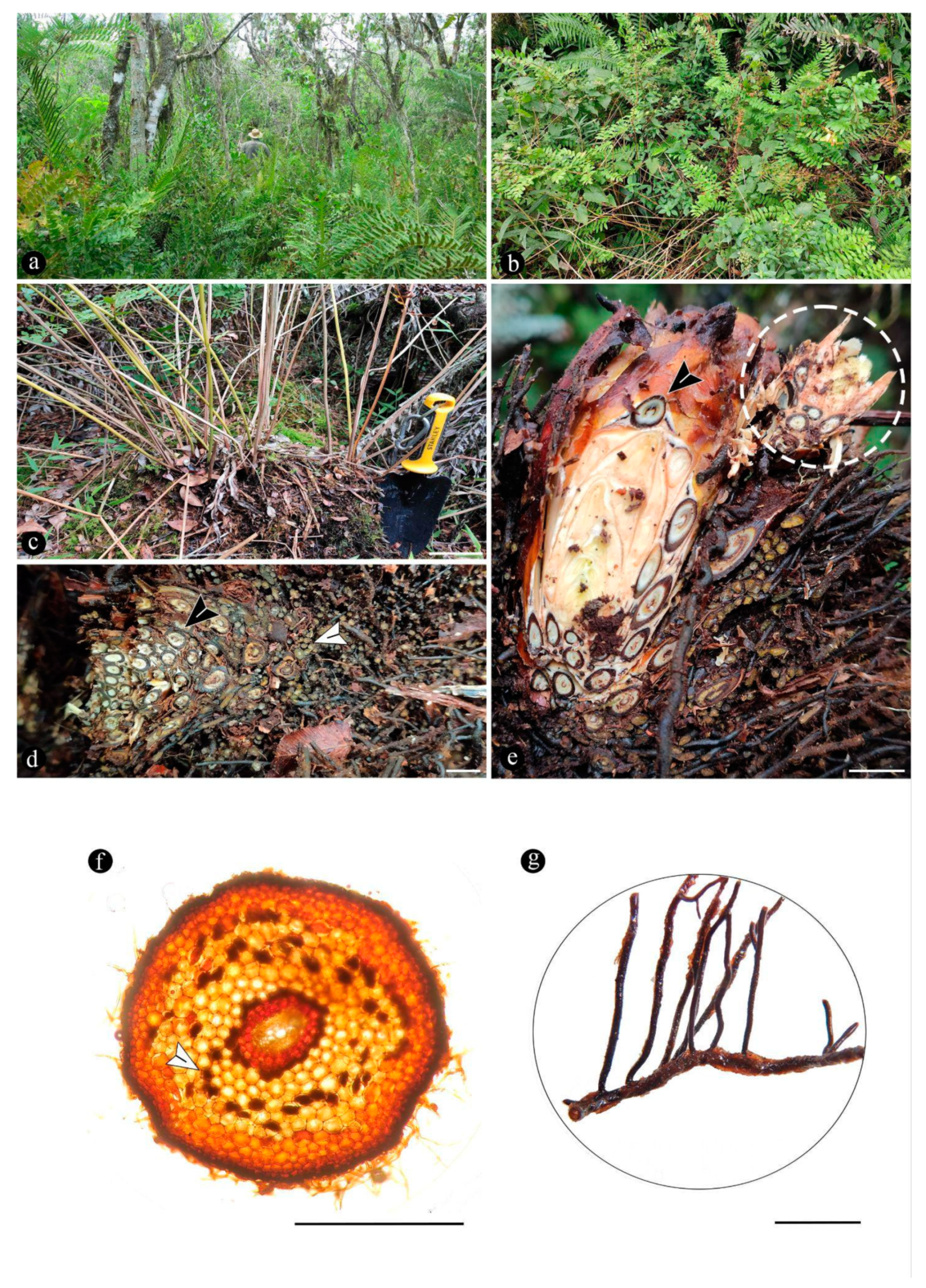

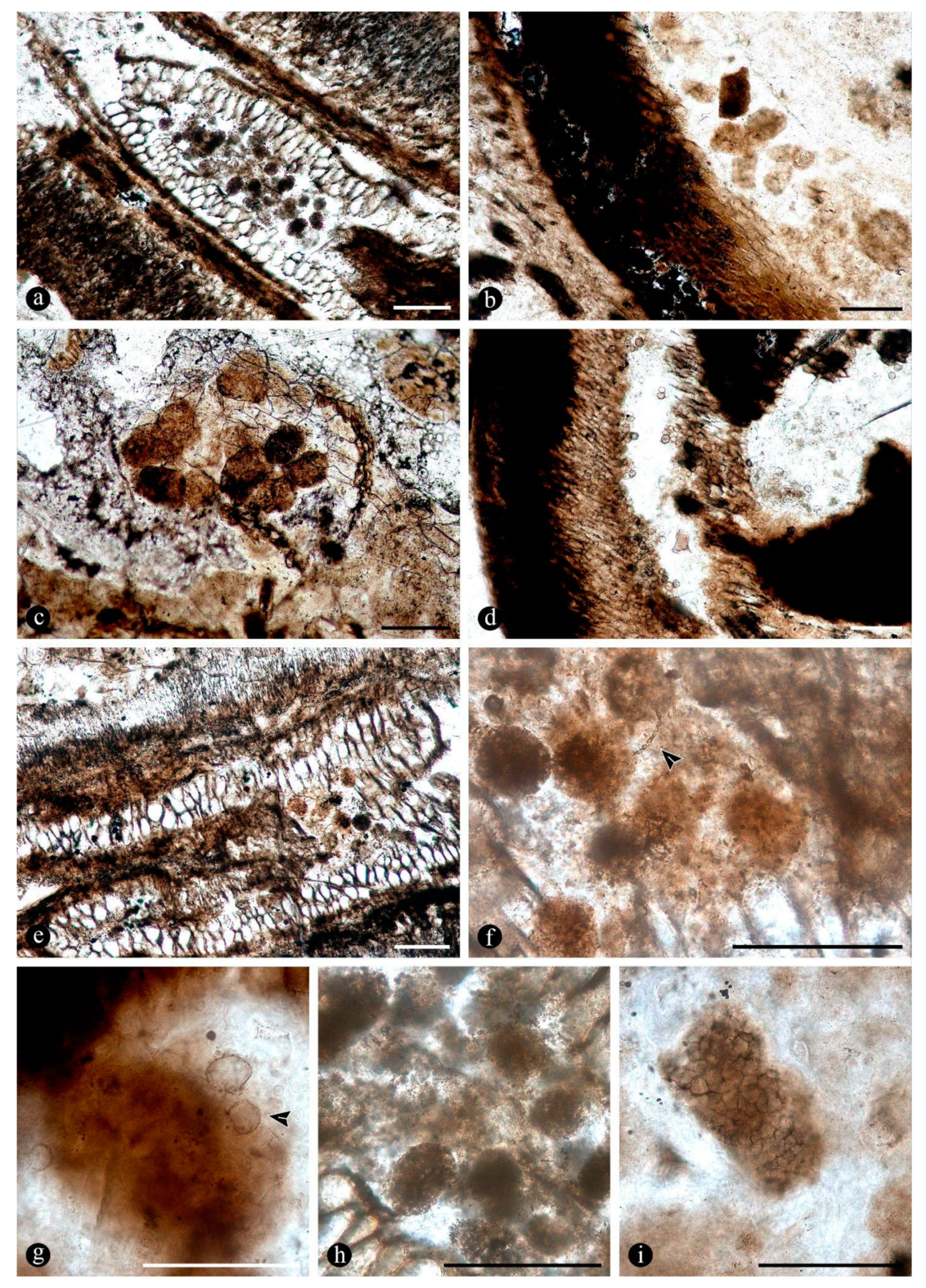

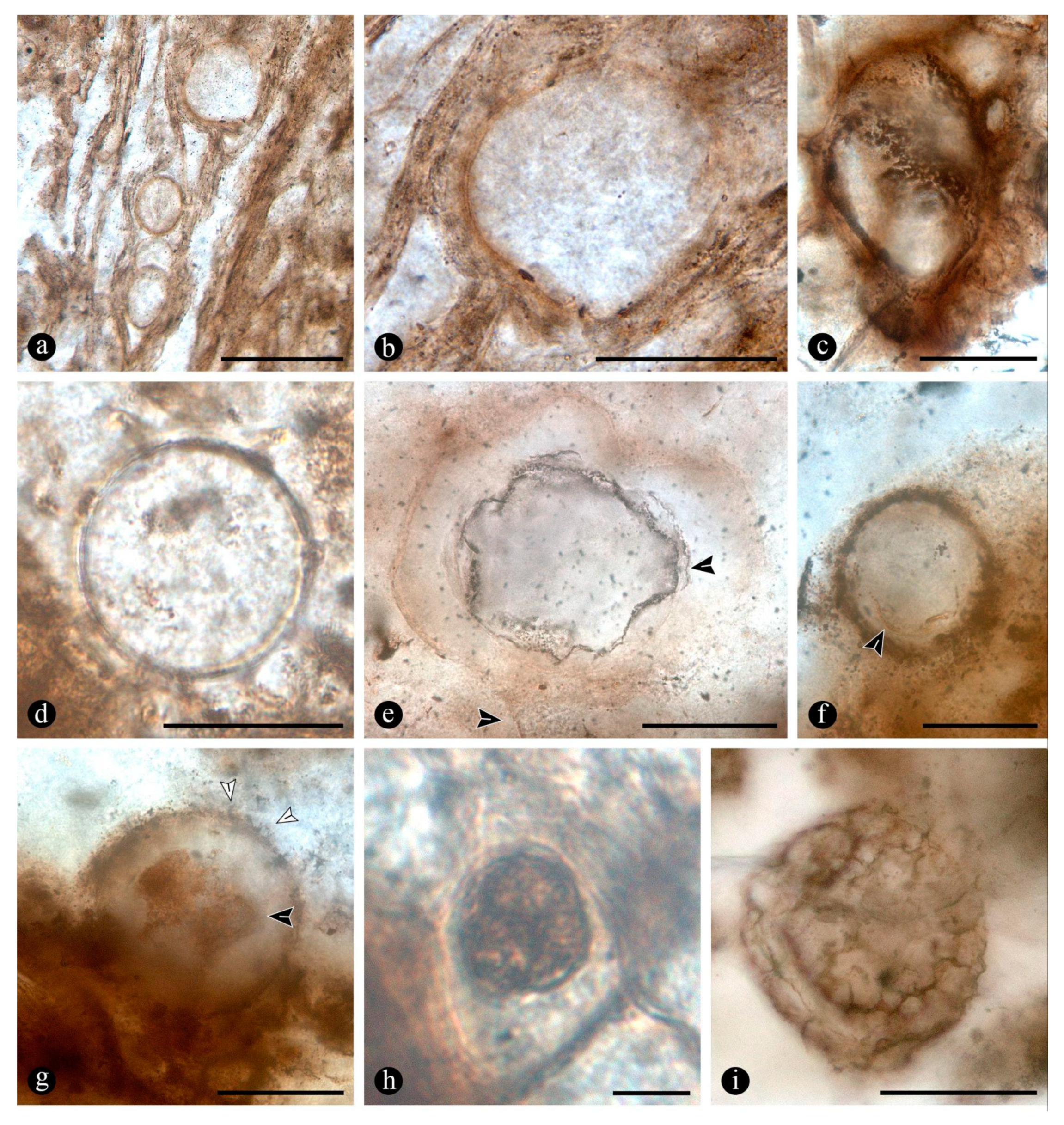

2.2. Associated Plants

2.3. Composition of the Main Chert Blocks (Include Spatial Arrangement and Habit Within Individual Cherts and Relationships Among Chert Blocks)

3. Discussion

Microbial Community

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Geological Context of the Studied Area

4.2. Preparation and Imaging of Fossil Material

4.3. Surface 3D-Scanning of Fossils

4.4. Surface 3D-Scanning of Fossils

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jablonski, D.; Gould, S.J.; Raup, D.M. The Nature of the Fossil Record: A Biological Perspective. In Patterns and Processes in the History of Life; Raup, D.M., Jablonski, D., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1986; pp. 7–22. ISBN 978-3-642-70833-6. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.R. The Taphonomy of Plant Macrofossils. In The Processes of Fossilization; Donovan, S.K., Ed.; Belhaven Press: London, 1991; pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, R.A. Plant Taphonomic Processes. In Taphonomy; Allison, P.A., Briggs, D.E.G., Eds.; Topics in Geobiology; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1991; ISBN 978-1-4899-5036-9. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T.N.; Krings, M.; Taylor, E.L. Fossil Fungi; Academic Press: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L.; Krings, M. Paleobotany: The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bomfleur, B.; McLoughlin, S.; Vajda, V. Fossilized Nuclei and Chromosomes Reveal 180 Million Years of Genomic Stasis in Royal Ferns. Science 2014, 343, 1376–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfleur, B.; Decombeix, A.L.; Escapa, I.H.; Schwendemann, A.B.; Axsmith, B. Whole-Plant Concept and Environment Reconstruction of a Telemachus Conifer (Voltziales) from the Triassic of Antarctica. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 174, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, C.J.; Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L.; Cúneo, N.R.; Boucher, L.D.; Yao, X.L. Osmunda (Osmundaceae) from the Triassic of Antarctica: An Example of Evolutionary Stasis. Am. J. Bot. 888, 85, 1998.

- Schwendemann, A.B.; Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L.; Krings, M. Organization, Anatomy, and Fungal Endophytes of a Triassic Conifer Embryo. Am. J. Bot. 2010, 97, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.N. Evolution of the Fern Family Osmundaceae Based on Anatomical Studies. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. Univ. Mich. 1971, 23, 105–169. [Google Scholar]

- DiMichele, W.A.; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Olszewski, T.D.; Labandeira, C.C.; Pandolfi, J.M.; Wing, S.L.; Bobe, R. Long-Term Stasis in Ecological Assemblages: Evidence from the Fossil Record. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 285–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, M.; Monjau, T.; Rosche, C. Synopsis of Osmunda (Royal Ferns; Osmundaceae): Towards Reconciliation of Genetic and Biogeographic Patterns with Morphologic Variation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 205, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escapa, I.H.; Cúneo, N.R. Fertile Osmundaceae from the Early Jurassic of Patagonia, Argentina. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 173, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, W.D.; Ash, S.R. A Review of Selected Triassic to Early Cretaceous Ferns. J. Plant Res. 1994, 107, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagasti, A.J.; Massini, J.G.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Channing, A. Millerocaulis Zamunerae Sp. Nov. (Osmundaceae) from Jurassic, Geothermally Influenced, Wetland Environments of Patagonia, Argentina. Alcheringa Australas. J. Palaeontol. 2016, 40, 456–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, X.; Sun, T. Two New Species of Mesozoic Tree Ferns (Osmundaceae: Osmundacaulis) in Eurasia as Evidence of Long-Term Geographic Isolation. Geosci. Front. 2020, 11, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfleur, B.; Grimm, G.W.; McLoughlin, S. The Fossil Osmundales (Royal Ferns)—a Phylogenetic Network Analysis, Revised Taxonomy, and Evolutionary Classification of Anatomically Preserved Trunks and Rhizomes. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tryon, R.M.; Tryon, A.F. Ferns and Allied Plants: With Special Reference to Tropical America; Springer: New York, NY, 1982; ISBN 978-1-4613-8164-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, E. A New Specimen of Millerocaulis (Osmundales: Osmundaceae) from the Cerro Negro Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Antarctica. Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. Nueva Ser. 2010, 12, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, G.W.; Kapli, P.; Bomfleur, B.; McLoughlin, S.; Renner, S.S. Using More Than the Oldest Fossils: Dating Osmundaceae with Three Bayesian Clock Approaches. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K.A. Jurassic Hot Spring Deposits of the Deseado Massif (Patagonia, Argentina): Characteristics and Controls on Regional Distribution. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2011, 203, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Massini, J.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Channing, A. First Glimpse of the Silicified Hot Spring Biota from a New Jurassic Chert Deposit in the Deseado Massif, Patagonia, Argentina. Ameghiniana 2016, 53, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankhurst, R.J.; Riley, T.R.; Fanning, C.M.; Kelley, S.P. Episodic Silicic Volcanism in Patagonia and the Antarctic Peninsula: Chronology of Magmatism Associated with the Break-up of Gondwana. J. Petrol. 2000, 41, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, D.M. Subdivisión litofacial e interpretación del volcanismo jurásico (Grupo Bahía Laura) en el este del Macizo del Deseado, provincia de Santa Cruz. Rev. Asoc. Geológica Argent. 2004, 59, 727–742. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, R.J.; Leat, P.T.; Sruoga, P.; Rapela, C.W.; Márquez, M.; Storey, B.C.; Riley, T.R. The Chon Aike Province of Patagonia and Related Rocks in West Antarctica: A Silicic Large Igneous Province. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 81, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.R.; Leat, P.T.; Pankhurst, R.J.; Harris, C. Origins of Large Volume Rhyolitic Volcanism in the Antarctic Peninsula and Patagonia by Crustal Melting. J. Petrol. 2001, 42, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N.J.; Underhill, J.R. Controls on the Structural Architecture and Sedimentary Character of Syn-Rift Sequences, North Falkland Basin, South Atlantic. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2002, 19, 417–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K.A. A Large and Complete Jurassic Geothermal Field at Claudia, Deseado Massif, Santa Cruz, Argentina. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2014, 275, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.I.; García Massini, J.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K. Conifer Root Nodules Colonized by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Jurassic Geothermal Settings from Patagonia, Argentina. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 181, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.I.; García Massini, J.L.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K.A. Sooty Molds from the Jurassic of Patagonia, Argentina. Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 1464–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Massini, J.L.; Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K.C.; Sagasti, A.J.; Krings, M. Filamentous Cyanobacteria and Associated Microorganisms, Structurally Preserved in a Late Jurassic Chert from Patagonia, Argentina. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2021, 107, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.P.; Rowe, N.P. Fossil Plants and Spores: Modern Techniques; Geological Society of London, 1999; ISBN 978-1-86239-035-5.

- Hass, H.; Rowe, N.P. Thin Section and Wafering. In Fossil Plant and Spores: Modern Techniques.; Jones, T.P., Rowe, N.P., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, 1999; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bercovici, A.; Hadley, A.; Villanueva-Amadoz, U. Improving Depth of Field Resolution for Palynological Photomicrography. Palaeontol. Electron. 2009, 12, 0–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zarlavsky, G.E. Histología Vegetal: Técnicas Simples y Complejas; 1st ed.; Sociedad Argentina de Botánica: Buenos Aires, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, P.J.; Ivany, L.C.; Schopf, K.M.; Brett, C.E. The Challenge of Paleoecological Stasis: Reassessing Sources of Evolutionary Stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 11269–11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.; Angiolini, C. Population Structure of Osmunda Regalis in Relation to Environment and Vegetation: An Example in the Mediterranean Area. Folia Geobot. 2011, 46, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.; Angiolini, C. Ecological Responses of Osmunda Regalis to Forest Canopy Cover and Grazing. Am. Fern J. 2010, 100, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimešová, J.; Ottaviani, G.; Charles-Dominique, T.; Campetella, G.; Canullo, R.; Chelli, S.; Janovský, Z.; Lubbe, F.C.; Martínková, J.; Herben, T. Incorporating Clonality into the Plant Ecology Research Agenda. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, A.; Petersen, R.L. Longevity of Interrupted Fern Colonies. Southeast. Nat. 2015, 14, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalos, J.L.; Ottaviani, G.; Chelli, S.; Rea, A.; Elder, S.; Dobrowolski, M.P.; Mucina, L. Plant Clonality in a Soil-Impoverished Open Ecosystem: Insights from Southwest Australian Shrublands. Ann. Bot. 2022, 130, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burr, M.D.; Botero, L.M.; Young, M.J.; Inskeep, W.P.; McDermott, T.R. Observations Concerning Nitrogen Cycling in a Yellowstone Thermal Soil Environment. In Geothermal Biology and Geochemistry in Yellowstone National Park: Proceeding of the Thermal Biology Institute Workshop, Yellowstone National Park, W.Y.; Inskeep, W.P., Ed.; Montana State University Publications, 2005; pp. 171–182.

- Price, E.A.C.; Marshall, C. Clonal Plants and Environmental Heterogeneity – An Introduction to the Proceedings. Plant Ecol. 1999, 141, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, D.G.; Channing, A.; Campbell, K.A.; Zamuner, A. Jurassic Geothermal Landscapes and Fossil Ecosystems at San Agustín, Patagonia, Argentina. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2010, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguraiuja, R.; Zobel, M.; Zobel, K.; Moora, M. Conservation of the Endemic Fern Lineage Diellia (Aspleniaceae) on the Hawaiian Islands: Can Population Structure Indicate Regional Dynamics and Endangering Factors? Folia Geobot. 2008, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.I.; Massini, J.L.G.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K. Conifer Root Nodules Colonized by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Jurassic Geothermal Settings from Patagonia, Argentina. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 181, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.I.; García Massini, J.L.; Escapa, I.H.; Guido, D.M.; Campbell, K.A. Sooty Molds from the Jurassic of Patagonia, Argentina. Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 1464–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escapa, I.H.; Garcia Massini, J.L.; Nunes, C.; Guido, D. Assembling a Jurassic Puzzle: Anatomically Preserved Conifer Remains in Hot Spring Deposits from Santa Cruz Province, Argentina.; Minesota, USA, 2018.

- Escapa, I.H.; Elgorriaga, A.; Nunes, C.; Scasso, R.; Cúneo, N.R. Megafloras Del Jurásico En La Cuenca de Cañadón Asfalto: Biomas En Transformación.; Puerto Madryn, 2022; pp. 878–901.

- Iglesias, A.; Artabe, A.E.; Morel, E.M. The Evolution of Patagonian Climate and Vegetation from the Mesozoic to the Present. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 103, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regiones de humedales de la Argentina; Benzaquén, L. , Blanco, D.E., Bo, Kandus, P., Lingua, G., Minotti, P., Quintana, R., Eds.; 1st ed.; Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, Fundación Humedales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017; ISBN 978-987-29811-6-7. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Martin, F.M.; Selosse, M.-A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal Ecology and Evolution: The Past, the Present, and the Future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüßler, A.; Walker, C. The Glomeromycota: A Species List with New Families and New Genera; Createspace Independent Pub: Gloucester, England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, J.B.; Redecker, D. Two New Families of Glomales, Archaeosporaceae and Paraglomaceae, with Two New Genera Archaeospora and Paraglomus, Based on Concordant Molecular and Morphological Characters. Mycologia 2001, 93, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press, 2010; ISBN 978-0-08-055934-6.

- Kessler, M.; Jonas, R.; Strasberg, D.; Lehnert, M. Mycorrhizal Colonizations of Ferns and Lycophytes on the Island of La Réunion in Relation to Nutrient Availability. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2010, 11, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, Y.-L. Phylogenetic Distribution and Evolution of Mycorrhizas in Land Plants. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 299–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnert, M.; Krug, M.; Kessler, M. A Review of Symbiotic Fungal Endophytes in Lycophytes and Ferns – a Global Phylogenetic and Ecological Perspective. Symbiosis 2017, 71, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozynski, K.A.; Malloch, D.W. The Origin of Land Plants: A Matter of Mycotrophism. Biosystems 1975, 6, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C. Coevolution of Roots and Mycorrhizas of Land Plants. New Phytol. 2002, 154, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, M.; Kessler, M. Review Mycorrhizal Relationships in Lycophytes and Ferns. Fern Gaz. 2016, 20, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Younus, M. A Field Survey of Mycorrhizal Associations in Ferns of Pakistan. New Phytol. 1981, 87, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C. Mycorrhizal Associations and Other Means of Nutrition of Vascular Plants: Understanding the Global Diversity of Host Plants by Resolving Conflicting Information and Developing Reliable Means of Diagnosis. Plant Soil 2009, 320, 37–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C. Biological reviews. 2004, pp. 473–495.

- Wright, D.P.; Scholes, J.D.; Read, D.J. Effects of VA Mycorrhizal Colonization on Photosynthesis and Biomass Production of Trifolium Repens L. Plant Cell Environ. 1998, 21, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yu, F.-H.; Alpert, P.; Dong, M. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Reduce Effects of Physiological Integration in Trifolium Repens. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C.; Graham, J.-H.; Smith, F.A. Functioning of Mycorrhizal Associations along the Mutualism–Parasitism Continuum. New Phytol. 1997, 135, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiak, M.; Olejniczak, P.; Lembicz, M. Diversified Impact of Mycorrhizal Inoculation on Mother Plants and Daughter Ramets in the Clonally Spreading Plant Hieracium Pilosella L. (Asteraceae). Plant Ecol. 2019, 220, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittebiere, A.-K.; Benot, M.-L.; Mony, C. Clonality as a Key but Overlooked Driver of Biotic Interactions in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2020, 43, 125510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dighton, J. Fungi in Ecosystem Processes, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-37152-8. [Google Scholar]

- Huey, C.J.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Uda, M.N.A.; Zulhaimi, H.I.; Jaafar, M.N.; Kasim, F.H.; Yaakub, A.R.W. Mycorrhiza: A Natural Resource Assists Plant Growth under Varied Soil Conditions. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, R.S.; Sheehan, K.B.; Stout, R.G.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Henson, J.M. Thermotolerance Generated by Plant/Fungal Symbiosis. Science 2002, 298, 1581–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, R.S.; Litvintseva, A.; Sheehan, K.B.; Henson, J.M.; Rodriguez, R.J. Fungi from Geothermal Soils in Yellowstone National Park | Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 5193–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streitwolf-Engel, R.; Van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wiemken, A.; Sanders, I.R. The Ecological Significance of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Effects on Clonal Reproduction in Plants. Ecology 2001, 82, 2846–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, M.; Kottke, I.; Setaro, S.; Pazmiño, L.F.; Suárez, J.P.; Kessler, M. Mycorrhizal Associations in Ferns from Southern Ecuador. Am. Fern J. 2009, 99, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura-Tsujita, Y.; Hirayama, Y.; Sakoda, A.; Suzuki, A.; Ebihara, A.; Morita, N.; Imaichi, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Colonization in Field-Collected Terrestrial Cordate Gametophytes of Pre-Polypod Leptosporangiate Ferns (Osmundaceae, Gleicheniaceae, Plagiogyriaceae, Cyatheaceae) | Mycorrhiza. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channing, A.; Edwards, D. Yellowstone Hot Spring Environments and the Palaeo-Ecophysiology of Rhynie Chert Plants: Towards a Synthesis. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, F.K. Aquatic Phycomycetes; 2d rev. ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, H.L.; Hunter, B.B. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi, 4th ed.; APS Press: St. Paul, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, G.W. How to Know Freshwater Algae. Pictured Key Nature Series., 3rd ed.; Wm. C. Brown Company Publishers: Dubuque, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, R.T.; Baker, T.; Burbridge, S.M. Arcellaceans (Thecamoebians) as Proxies of Arsenic and Mercury Contamination in Northeastern Ontario Lakes. J. Foraminifer. Res. 1996, 26, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalier-Smith, T. A Revised Six-Kingdom System of Life. Biol. Rev. 1998, 73, 203–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, M.W. Straminipilous Fungi: Systematics of the Peronosporomycetes Including Accounts of the Marine Straminipilous Protists, the Plasmodiophorids and Similar Organisms; Kluwer Academic Publishers: London, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, D.H.; Small, E.B. Phylum Ciliophora. In The illustrated guide to the Protozoa; Lee, J.J., Leedale, G.F., Bradbury, P., Eds.; Society of Protozoologists, Allen Press Inc.: Lawrence, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 371–656. [Google Scholar]

- Mesterfield, R. Order Arcellinida. In The illustrated guide to the Protozoa; Lee, J.J., Leedale, G.F., Eds.; Society of Protozoologists, Allen Press Inc.: Lawrence, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 827–859. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, D.J. Free-Living Freshwater Protozoa. A Color Guide.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Karling, J.S. The Plasmodiophorales, 1st ed.; The author: New York city, 1942; pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Heger, T., J.; Foissner, W. Ecology and Biodiversity of Testate Amoebae in Freshwater Habitats. Hydrobiologia 2009, 634, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Huann-Ju, H.; Chang, H.-S. Five Species of Pythium, Two Species of Pythiogeton New for Taiwan and Pythium Afertile. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 1976, 17, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, M.W. Morphology and Taxonomy of the Oomycetes, with Special Reference to Saprolegniaceae, Leptomitaceae and Pythiaceae. New Phytol. 1969, 68, 751–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalgutkar, R.M.; Jansonius, J. Synopsis of Fossil Fungal Spores, Mycelia and Fructifications; Palynologists, Contribution Series, Ed.; American Association of Stratigraphic: Dallas, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karling, J.S. Chytridiomycetarum Iconographia; Lubrecht & Cramer Ltd: Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Longcore, J.E. Chytridiomycete Taxonomy since 1960. Mycotaxon 1996, 60, 149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Longcore, J.E. Chytridiomycota. In Systematics and Evolution of Fungi; Springer, 1995.

- Gleason, F.H.; Scholz, B.; Jephcott, T.G.; van Ogtrop, F.F.; Henderson, L.; Lilje, O.; Kittelmann, S.; Macarthur, D.J. Key Ecological Roles for Zoosporic True Fungi in Aquatic Habitats. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLeo, K.; Donat, K.; Min-Venditti, A.; Dighton, J. A Correlation between Chytrid Abundance and Ecological Integrity in New Jersey Pine Barrens Waters. Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimington, W.R.; Duckett, J.G.; Field, K.J.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Pressel, S. The Distribution and Evolution of Fungal Symbioses in Ancient Lineages of Land Plants. Mycorrhiza 2020, 30, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimington, W.R.; Pressel, S.; Duckett, J.G.; Bidartondo, M.I. Fungal Associations of Basal Vascular Plants: Reopening a Closed Book? New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1394–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W.G. The Ecology of the Freshwater Algae Potamogeton in the English Lakes. J. Ecol. 1954, 42, 366–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, P.J.; Petrini, O. Fungal Endophytes in Phragmites Australis. Mycol. Res. 1992, 96, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Channing, A.; Wujek, D.E. Preservation of Protists within Decaying Plants from Geothermally Influenced Wetlands of Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, United States. PALAIOS 2010, 25, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krings, M.; Harper, C.J.; White, J.F.; Barthel, M.; Heinrichs, J.; Taylor, E.L.; Taylor, T.N. Fungi in a Psaronius Root Mantle from the Rotliegend (Asselian, Lower Permian/Cisuralian) of Thuringia, Germany. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2017, 239, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, S.; Bomfleur, B. Biotic Interactions in an Exceptionally Well Preserved Osmundaceous Fern Rhizome from the Early Jurassic of Sweden. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016, 464, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bippus, A.C.; Escapa, I.H.; Wilf, P.; Tomescu, A.M.F. Fossil Fern Rhizomes as a Model System for Biotic Interactions across Geologic Time: Evidence from Patagonia; PeerJ Inc. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.B. British Fungi, Part 2; Jarrold Publishing: Norwich, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.B. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes; Kew Botanical Garden: Surrey, England, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, P.F.; Kirk, P.M. Fungal Families of the World; CAB International: Surrey, England, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; Minter, D.W. Dictionary of the Fungi, 3rd ed.; CABI Europe: UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W. Anderson Compendium of Soil Fungi, 2nd ed.; IHW-Verlag: Eching, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Osono, T. Ecology of Ligninolytic Fungi Associated with Leaf Litter Decomposition. Ecol. Res. 2007, 22, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.K.; Mishra, R.R. Fungi Associated with the Fronds of Pteris Vittata L. (Pteridaceae). Trop. Ecol. 29-33, 35, 1994.

- Kumar, D.S.; Hyde, K.D. Endophytic Fungal Assemblages in Fern Species: A Preliminary Study. Mycoscience 2004, 45, 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, R.J.; Ferrari, M.A. Role of the Fungus Penicillium in the Formation of Appressoria and Pathogenicity in Plants. Mycol. Res. 93, 345–353.

- Chandra, G.; Chatter, K.F. Microbiology Reviews. 2014, pp. 345–379.

- Chandra, G.; Chater, K. Developmental Biology of Streptomyces from the Perspective of 100 Actinobacterial Genome Sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, M.; Sbrana, C.; Avio, L.; Citernesi, A.S.; Logi, C. Differential Hyphal Morphogenesis in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi during Pre-Infection Stages. New Phytol. 1993, 125, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannier, N.; Bittebiere, A.-K.; Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Mony, C. AM Fungi Patchiness and the Clonal Growth of Glechoma Hederacea in Heterogeneous Environments. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittebiere, A.-K.; Benot, M.-L.; Mony, C. Clonality as a Key but Overlooked Driver of Biotic Interactions in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2020, 43, 125510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannier, N.; Mony, C.; Bittebiere, A.-K.; Michon-Coudouel, S.; Biget, M.; Vandenkoornhuyse, P. A Microorganisms’ Journey between Plant Generations. Microbiome 2018, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarze, F.W.M.R. Wood Decay under the Microscope. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Nilsson, N.; Daniel, D. Variable Resistance of Pinus Sylvestris Wood Components to Attack by Wood Degrading Bacteria. In Recent Advances in Wood Anatomy; Donaldson, L.A., Singh, A.P., Butterfield, B.G., Whitehouse, L., Eds.; New Zealand Forest Research Institute: Rotorua, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Singh, A.P. Micromorphological Characteristics of Wood Biodegradation in Wet Environments: A Review. IAWA J. 2000, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Kim, Y.S. ; Singh Tripti Bacterial Degradation of Wood. In Secondary Xylem Biology; Kim, Y.S., Funada, R., Singh, A.P., Eds.; Elsevier Inc., 2016; pp. 169–190.

- Shigo, A.L.; Marx, H.G. Compartimentalization of Decay in Trees. Bull. US Dep. Agric. 1977, 405, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, A.C. International biodeterioration & biodegradation. 1996,.

- Labandeira, C.C.; Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, J.I.; Estep, J.W. The Role of Insects in Late Jurassic to Middle Cretaceous Ecosystems. In Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin: Albuquerque, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, D.W.; Taylor, E.L. Evidence of Oribatid Mite Detritivory in Antarctica during the Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic. J. Paleontol. 2004, 78, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.A. Potential of Oribatid Mites in Biodegradation and Mineralization for Enhancing Plant Productivity. Acarol. Stud. 2019, 1, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tidwell, W.D.; Clifford, H.T. Three New Species of Millerocaulis (Osmundaceae) from Queensland, Australia. Aust. Syst. Bot. 1995, 8, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Rozario, A.; Labandeira, C.; Guo, W.-Y.; Yao, Y.-F.; Li, C.-S. Spatiotemporal Extension of the Euramerican Psaronius Component Community to the Late Permian of Cathaysia: In Situ Coprolites in a P. Housuoensis Stem from Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2011, 306, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.D. Frass Characteristics for Identifying Insect Borers (Lepidoptera: Cossidae and Sesiidae; Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in Living Hardwoods. Can. Entomol. 1977, 109, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.D. Guide to Insect Borers in North American Broadleaf Trees and Shrubs; United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service: New Orleans, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Greppi, C.D.; García Massini, J.L.; Pujana, R.R. Saproxylic Arthropod Borings in Nothofagoxylon Woods from the Miocene of Patagonia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 571, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrylenko, D.; Winterhalter, J.J. Insectos Del Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapí; Administración General de Parques Nacionales y Turismo. 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, M.; Grove, S.J.; Richardson, A.M.M.; Mohammed, C.L. Brown Rot in Inner Heartwood: Why Large Logs Support Characteristic Saproxylic Beetle Assemblages of Conservation Concern. In Insect biodiversity and dead wood: proceedings of a symposium for the22nd International Congress of Entomology; Grove, G.J., Simon, J., Hanula, J.L., Eds.; Department of Agriculture Forest Service, SouthernResearch Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2006; pp. 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kukor, J.J.; Martin, M.M. Cellulose Digestion inMonochamus Marmorator Kby (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae): Role of Acquired Fungal Enzymes. J. Chem. Ecol. 1986, 12, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wotton, R.S.; Malmqvist, B.; Muotka, T.; Larsson, K. Fecal Pellets from a Dense Aggregation of Suspension-Feeders in a Stream: An Example of Ecosystem Engineering. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendemann, A.B.; Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L.; Krings, M.; Dotzler, N. Combresomyces Cornifer from the Triassic of Antarctica: Evolutionary Stasis in the Peronosporomycetes. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2009, 154, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, E.; Krokene, P.; Berryman, A.A.; Franceschi, V.R.; Krekling, T.; Lieutier, F.; Lönneborg, A.; Solheim, H. Mechanical Injury and Fungal Infection Induce Acquired Resistance in Norway Spruce. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Krokene, P.; Christiansen, E.; Krekling, T. Anatomical and Chemical Defenses of Conifer Bark against Bark Beetles and Other Pests. New Phytol. 2005, 167, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokene, P.; Nagy, N.E.; Krekling, T. Traumatic Resin Ducts and Polyphenolic Parenchyma Cells in Conifers. In Induced Plant Resistance to Herbivory; Schaller, A., Ed.; Springer Science, 2008; pp. 147–169.

- Shain, L. Dynamic Responses of Differentiated Sapwood to Injury and Infection. Phytopathology 1979, 69, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgins, J.W.; Christiansen, E.; Franceschi, V.R. Induction of Anatomically Based Defense Responses in Stems of Diverse Conifers by Methyl Jasmonate: A Phylogenetic Perspective. Tree Physiol. 2004, 24, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokene, P.; Nagy, N.E.; Krekling, T. Traumatic Resin Ducts and Polyphenolic Parenchyma Cells in Conifers. In Induced plant resistance to herbivory; Schaller, A., Ed.; Springer: Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, L.G.; Guindeo, A.; Peraza, C.; de Palacios, P. La Madera y Su Anatomía; Fundacion Conde del Valle de Salazar, Mundi-prensa y AiTiM: Madrid, España, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rombola, C.F.; Greppi, C.D.; Pujana, R.R.; García Massini, J.L.; Bellosi, E.S.; Marenssi, S.A. Brachyoxylon Fossil Woods with Traumatic Resin Canals from the Upper Cretaceous Cerro Fortaleza Formation, Southern Patagonia (Santa Cruz Province, Argentina). Cretac. Res. 2022, 130, 105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonello, P.; Blodgett, J.T. Pinus Nigra–Sphaeropsis Sapinea as a Model Pathosystem to Investigate Local and Systemic Effects of Fungal Infection of Pines. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 63, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortle, W.C. Mechanisms of Compartmentalization of Decay in Living Trees. Phytopathology 1979, 69, 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, I. Dynamic Responses of Differentiated Sapwood to Injury and Infection. Phytopathology 1919, 69, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, E.; Franceschi, V.R.; Nagy, N.E.; Krekling, T.; Berryman, A.A.; Krokene, P.; Solheim, H. Traumatic Resin Duct Formation in Norway Spruce (Picea Abies (L.) Karst.) after Wounding or Infection with a Bark Beetle-Associated Blue-Stain Fungus, Ceratocystis Polonica. In Physiology and genetics of tree-phytophage interactions; Lieutier, F., Mattson, W.J., Wagner, M.R., Eds.; Les Colloques de I’INRA: Versailles, 1999; pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Pérez, L.A.; Zulueta-Rodríguez, R.; Andrade-Torres, A. Micorriza arbuscular, Mucoromycotina y hongos septados oscuros en helechos y licófitas con distribución en México: una revisión global. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2017, 65, 1062–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgushi, T. Herbivore-Induced Indirect Interaction Webs on Terrestrial Plants: The Importance of Non-Trophic, Indirect, and Facilitative Interactions. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2008, 128, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, F.S.; Deere, J.A.; Egas, M.; Eizaguirre, C.; Raeymaekers, J.A.M. The Diversity of Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics: Comparing the Feedbacks between Ecology and Evolution across Scales. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.-D.; Liu, R.-J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Associated with Common Pteridophytes in Dujiangyan, Southwest China. Mycorrhiza 2004, 14, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, U.; Nakashima, C.; Crous, P.W. Cercosporoid Fungi (Mycosphaerellaceae) 1. Species on Other Fungi, Pteridophyta and Gymnospermae. IMA Fungus 2013, 4, 265–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachi, S.; Loreau, M. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Productivity in a Fluctuating Environment: The Insurance Hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1463–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vislobokova, I.A. The Concept of Macroevolution in View of Modern Data. Paleontol. J. 2017, 51, 799–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples* | Distance between individuals from center to center (cm) | Diameter (cm) | Number of petiole cycles | Ramifications measurements (smaller individuals) | Petioles diameter (cm) | Roots diameter (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramification | Diameter | Number of petiole cycles | ||||||

| MPM-Pb 16096 | 15 | 7 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| MPM-Pb 16097 | 20 | 13 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 5 | - | - |

| - | - | - | 2 | 3 | 5 | - | - | |

| - | - | - | 3 | 4 | 6 | - | - | |

| - | 7 | 10 | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| - | 6 | 8 | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| MPM-Pb 16084-16085 | - | 14 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16086 | - | 5 | 5 | - | - | - | 1.5-10 | 0.6-1.8 |

| MPM-Pb 16087 | - | 13 | 10 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16088 | 10 | 10 | - | - | - | 1.8-73 | - | |

| MPM-Pb 16089 | - | 2.5 | 5 | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | 1.5 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| MPM-Pb 16090 | - | 8 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16091 | - | 14 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16092 | - | - | - | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16093 | - | 16 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16094 | - | 11 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MPM-Pb 16095 | - | 12 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yañez et al. 596 | 6.2 | 4.6-7 | 5-7 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 4-10.2 | 0.35-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).