1. Introduction

The urban structure is important for the function of the town. It is also important for the inhabitants’ everyday lives. In the towns, the number of facilities like schools, public buildings, transport, shops, and green and blue areas like parks, sports, and water is important. Besides the number of them and the areas, the spatial distribution in the town is also important. The distance and accessibility from living areas influence satisfaction. The availability of green space is one of many sub-factors in the lives of urban residents, which can then be generally expressed in terms of quality of life. Often, the conditions of a place for the inhabitants to live in are labeled with the composite term ‘liveability’ [

1]. A good mixture of urban patterns supports the needs of inhabitants. For example, the heterogeneous urban mixture supports inhabitants’ walking and leisure-time physical activities [

2,

3].

There are several advantages concerning the existence of green areas in the city. They enhance mental health and social cohesion. Access to green spaces has been linked to reduced stress, improved mood, and overall better mental health. Parks and green areas serve as communal spaces where people can gather and foster community and social interaction [

4]. The aesthetic and recreational value exists. Green areas enhance the visual appeal of urban landscapes and provide spaces for recreational activities, contributing to a higher quality of life [

5]. Green areas improve air quality because they help filter pollutants and produce oxygen, leading to cleaner air in urban environments. Green spaces serve for temperature regulation [

4]. They can mitigate the urban heat island effect by providing shade and cooling through evapotranspiration, making cities more comfortable during hot weather. The last benefit is economic. Green spaces can increase property values and attract businesses and tourism, boosting the local economy.

Assessing green and leisure areas’ access, satisfaction, and distribution is challenging. While it is possible to calculate the total area of green spaces, including parks and woodlands, two cities with the same amount of green space can differ significantly in how these areas are distributed. A large green area located at the town’s edge may only be accessible to nearby residents, making it less suitable for daily relaxation for other inhabitants of the town.

The investigation of urban structure has a long history. The Nature of Cities was written in 1945 and states the basic arrangements of cities by Harris and Ullman in 1945 [

6]. The structure of towns and cities is under fluent evolution. Nowadays, processing spatial data by geographical information systems (GIS) opens the opportunity to process spatial data automatically. GIS software helps to find new information and patterns in the city structure. A list of attempts can be found in the literature. To assess street-network integration, building density, and land-use mixture, Ye and Nes proposed the method of space syntax, space matrix, and mixed-use index (MXI) [

7]. The authors evaluated three new towns and one old town in the Netherlands, where the old town has a higher value land-use mixture than the new towns. The MXI tool by Hoek quantifies the degree of land-use diversity [

8]. It works in detail with data about the gross floor area of retail, working places (offices, factories), educational activities, and leisure activities (cinemas, ...) in each urban block.

The IPEN project (

https://www.ipenproject.org) calculates the walkability index of cities by the composition of four partial indexes: Connectivity index, Entropy index, Floor area ratio, and Household density. So, the walkability positively depends on the level of entropy of land use and heterogeneity [

9].

A new opportunity exists to research spatial land use patterns using colocation analysis. The use of this type of analysis is presented in this article. The base data is used from the Copernicus program – project Urban Atlas. [

10,

11]. The Urban Atlas data are available across more than 780 European functional urban areas. These data are used in several research projects [

12,

13,

14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Colocation Patterns in ArcGIS Pro

One type of data mining task is finding associations of co-occurring phenomena. The associations can be found in the Market Basket Analysis (MBA), a data mining method. Source data is a set of transactions with a list of co-occurring goods in the shopping basket. The transaction length varies and depends on the number of goods customers buy. The idea of an MBA could be generalized to other spheres, not only analyzing customers’ shopping behavior.

The spatial association of co-occurrence is not a frequent spatial analysis. One earlier idea is in the article of Koperski and Han about the combination of spatial and non-spatial ante decent and consequent in association rules concerning proximity to the beach and the house price [

15]. The spatial form of MBA or common spatial association analysis is not preset directly in GIS software. The variant of MBA could be considered the colocation analysis.

A colocation pattern is defined as a subset of spatial features whose instances frequently occur in each other’s proximity in a spatial domain [

16]. The colocation analysis is one newer spatial analysis in ArcGIS Pro 3. The tool Colocation Analysis belongs to the Spatial Statistics toolbox. Colocation measures local spatial association patterns, or colocation, between two categories of point features using the collocation quotient statistic [

17].

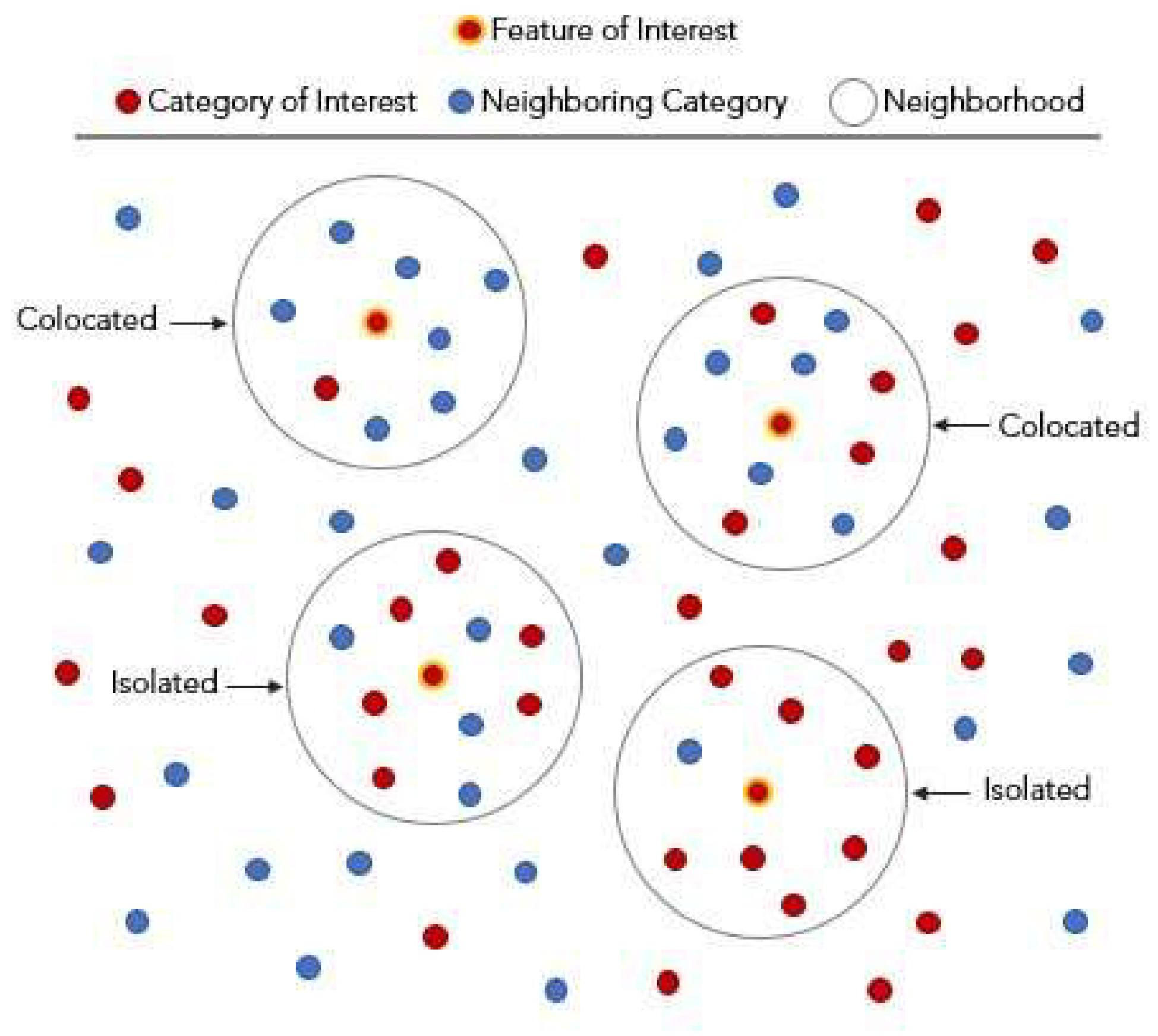

Compared to MBA, which analyses transactions of many co-occurring phenomena, the tool for colocation analysis in ArcGIS Pro software considers and evaluates only two categories. It means that the first category is taken as the category of interest (red points), and the second is taken as the neighboring category (blue points) in

Figure 1. Colocation analysis finds out whether one category tends to occur near another category (collocate) and how strong this tendency is by using the collocation coefficient statistic. The delimitation of neighbors could be taken in three optional ways. The first is

K nearest neighbors, the second is the

Distance band, and the third is

Spatial Weight from the Matrix File.

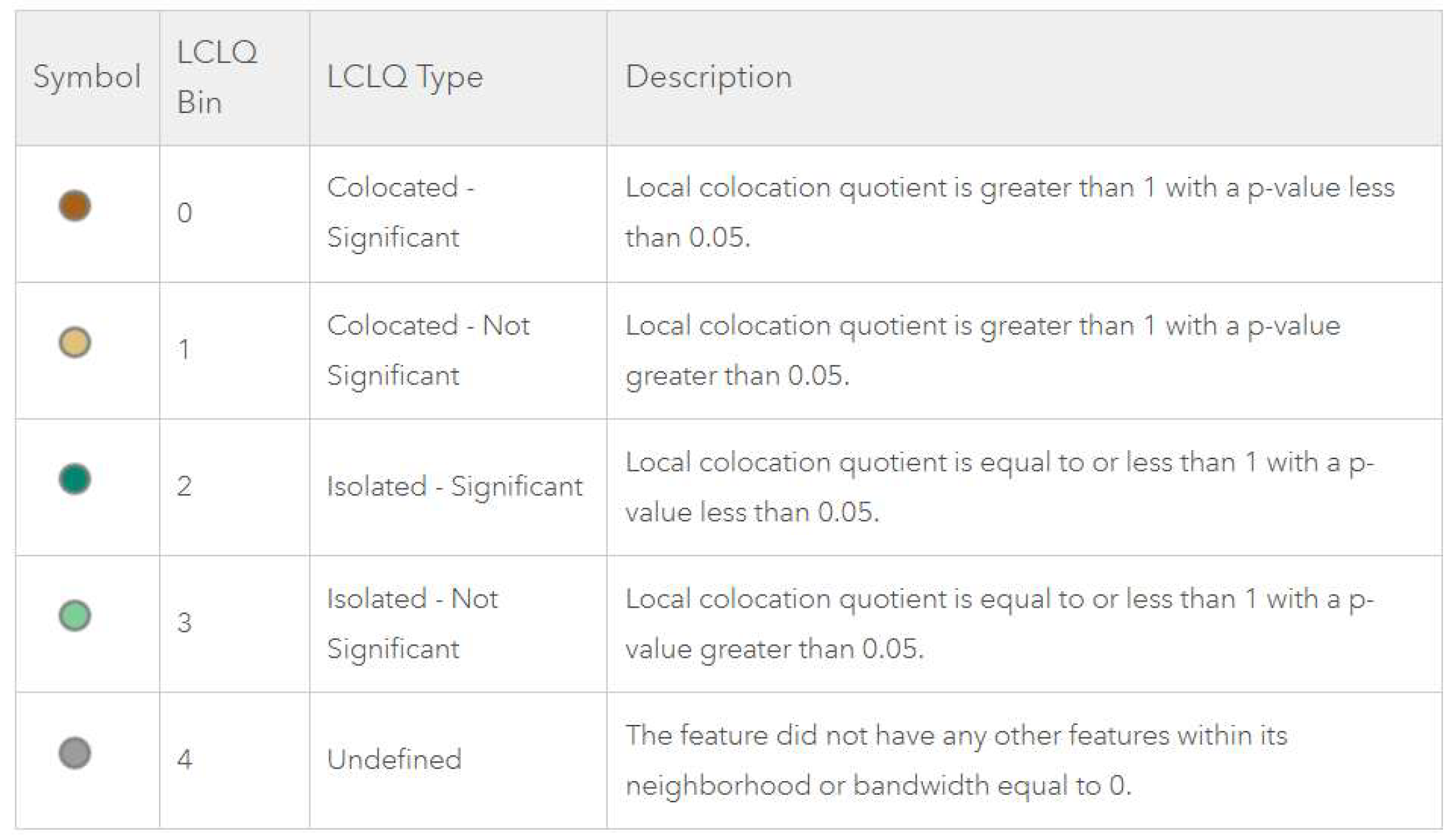

The results are presented as a new point layer where each point receives the value of the

colocation quotient (LCLQ) with statistical evaluation of significance by p-value. Each point is finally assigned into five groups:

collocated significantly,

collocated non-significantly,

isolated significantly,

isolated non-significantly and

undefined in the new point feature class. An expressive symbology is assigned for the new result point layer (

Figure 2). An important remark is that the colocation analysis for the two investigated input layers is not symmetrical. The results differ when the two input layers (Category of Interest and Neighboring Category) are switched. After switching, the first category is evaluated as a neighbor of the second category, now the category of interest.

2.2. Urban Atlas Data

The Urban Atlas is a joint initiative of the Directorate General REGIO and the European Union’s Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. The Urban Atlas provides pan-European comparable land cover and land use information for the selected Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) in Europe and the United Kingdom. The European Urban Atlas was designed to compare the land use patterns in major European cities and provide benchmarking for these cities [

10].

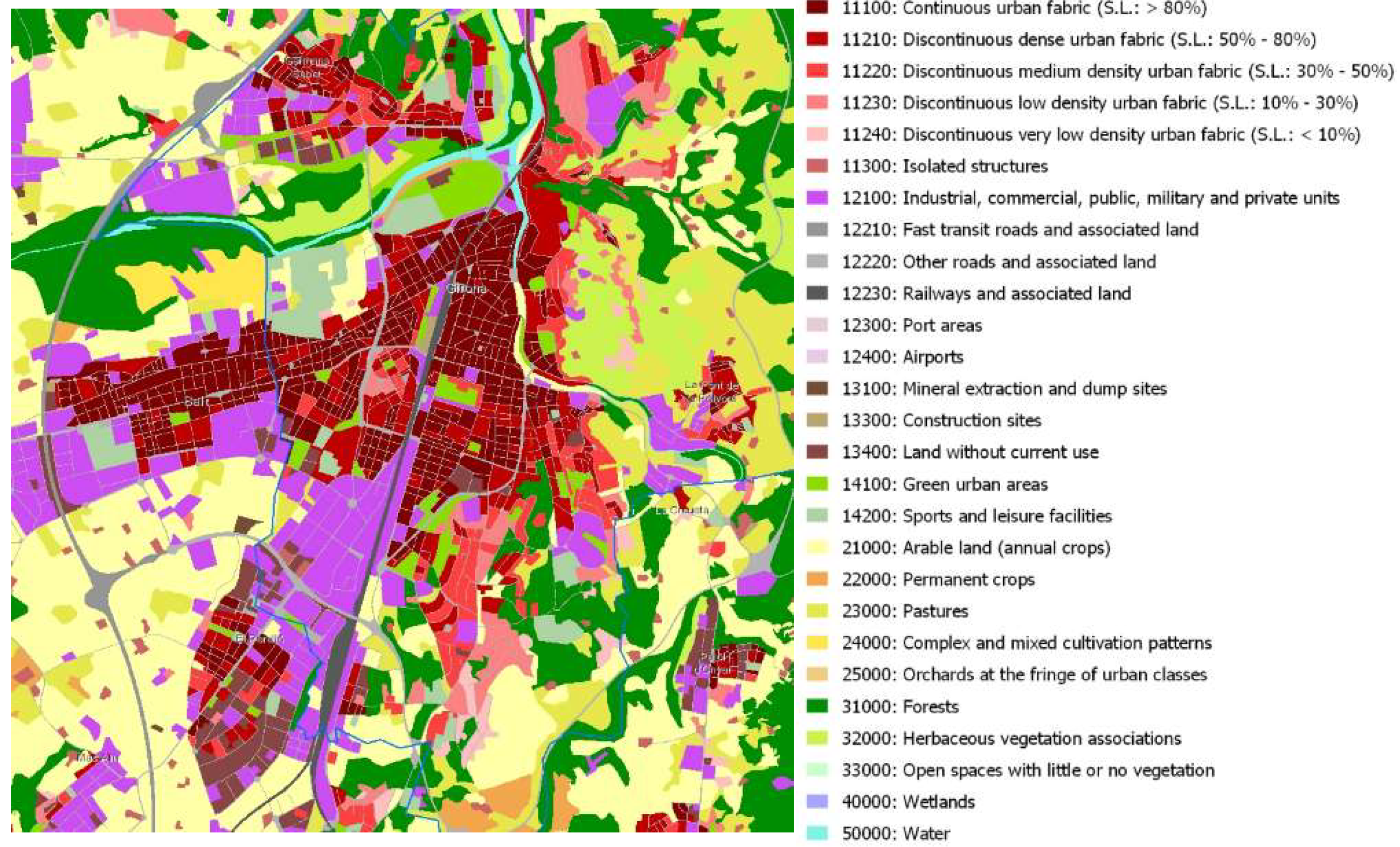

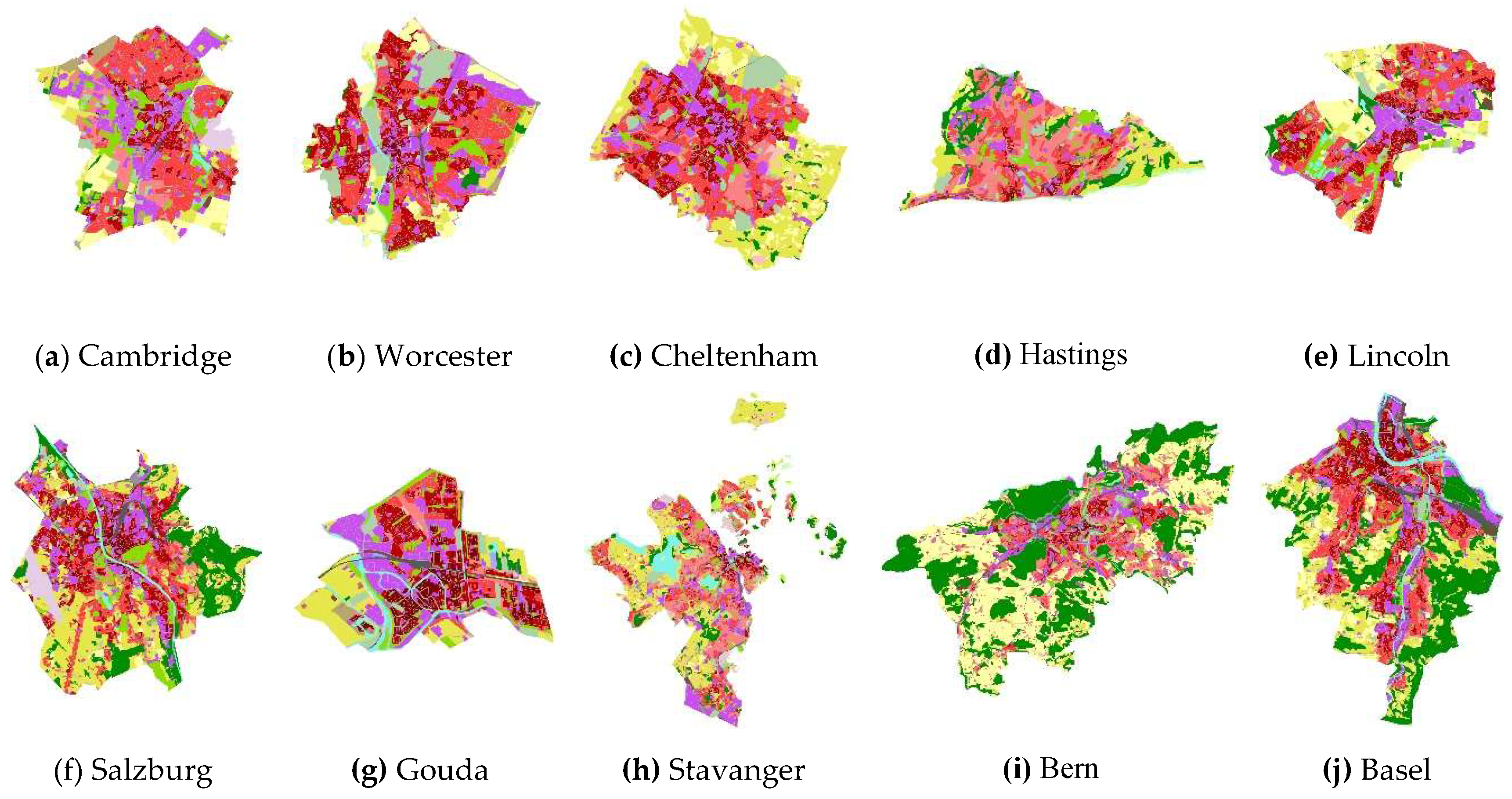

The Urban Atlas Land Use comprises 27 land use classes distributed among five thematic groups: Artificial surfaces, Agricultural areas, Natural and (semi)natural areas, Wetlands and Water. Each of the 27 classes is assigned a 5-digit code in nomenclature to express the belonging class and level of hierarchy (

Figure 3). The source data are publicly available in vector format in the geoDB database. The shapes of the data are polygons with codes of land use types. The data structure and mapping procedure are described in the Mapping Guide [

18]. The data contains the whole area of the Functional Urban Area (FUA) and the delimitation of the city core of the FUA. For the presented research, only the Cores of cities were extracted. A delivery report and unified legend with assigned colors for each land use accompany the data (

Figure 3). The data used in the presented research are from the latest version, where 2018 is the reference year.

2.3. Spatial Preprocessing and Analysis of Data

Colocation analysis works only with the point feature class. Urban Atlas uses polygon representation. The necessary step for data preparation was converting a polygon layer of land use to a point layer using the Feature To Point tool in ArcGIS Pro. The preferred position of the centroid was inside each polygon. Each polygon of land use is represented by a centroid for the next processing. The tool automatically copies the origin attribute data, like the code_2018 of land use, to the output point layer.

The colocation analysis considers only two categories simultaneously. In the case of using Urban Atlas data, several suitable combinations of pairs exist. Some combinations make no sense, like the colocation of orchards and airports, because the categories are not frequent. The results of these types of combinations bring no useful information for interpretation.

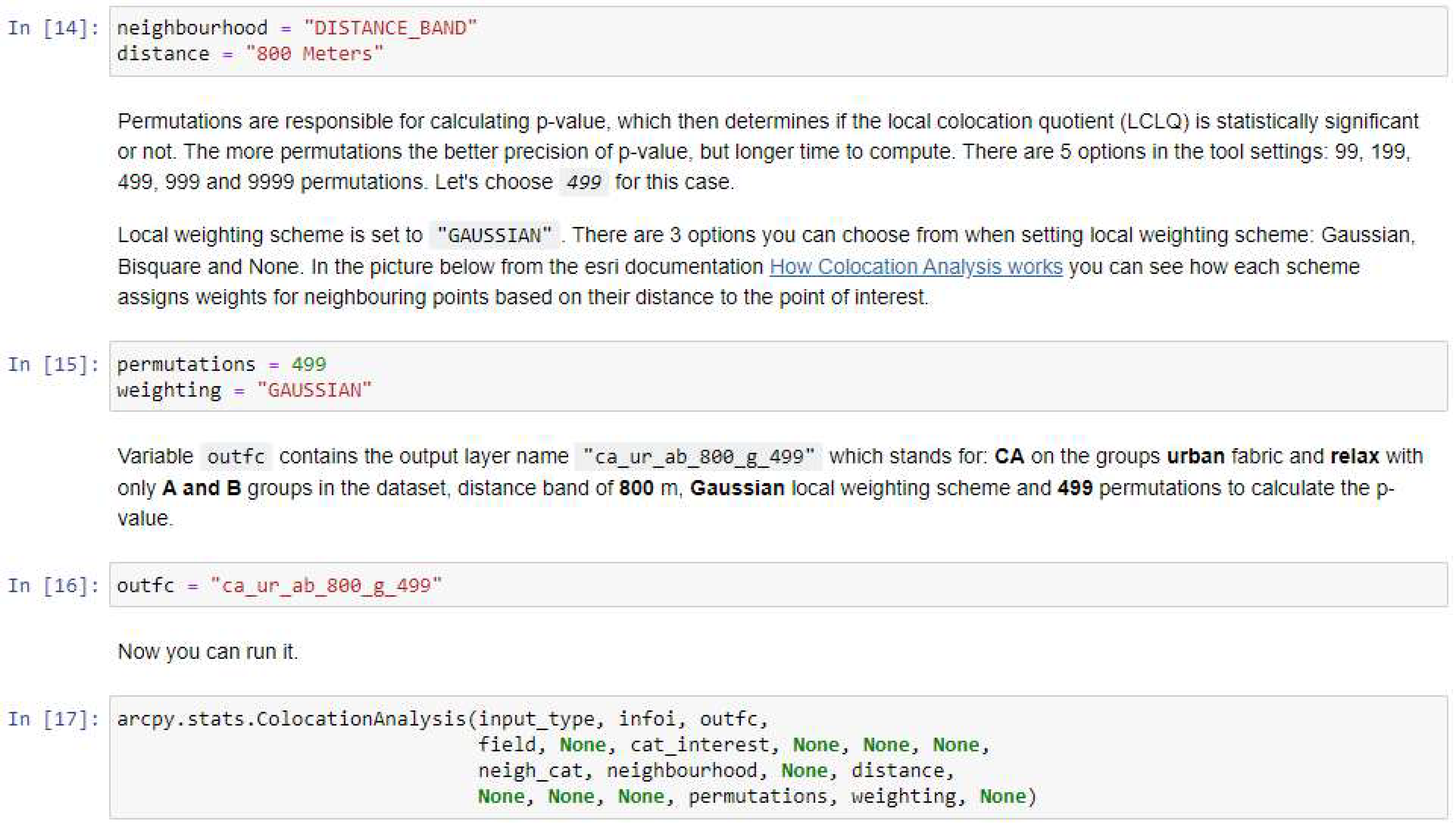

The Jupyter Notebook with Python code cells for ArcGIS Pro was used to automate the processing. This Jupyter notebook labeled

1_colocation_analysis.ipynb was designed by Adam Toth in his master’s thesis[

19]. The notebook is freely accessible on GitHub

GISAdamToth/ArcGIS_Notebooks_thesis [

20]. This notebook solves the data preparation and automation of colocation analysis above Urban Atlas data with different parameters in detailed steps. Text markdowns with textual explanations of partial steps accompany the Python code cells (

Figure 4). The commands work with the Map window in ArcGIS Pro to show partial preprocessing results and the final output layer of collocated or isolated points. Switching between the Notebook and Map windows is possible after each important step.

The notebook is mainly prepared for one specific task: finding patterns of urban fabrics (building blocks) and spaces for relaxing. The selected combination of two types is mainly considered the colocation that could express the living conditions of inhabitants. The research question is to find in which parts of the city are significantly collocated housing blocks (Category of Interest) with green areas and sports and leisure activities (Neighboring Category) in suitable proximity. Parts of the city where housing blocks are more significantly collocated with areas for relaxation are better for the everyday living of inhabitants. The opposite situation is where building blocks are significantly isolated from the area for relaxing spaces, which is worse for inhabitants. The step-by-step processing of data is demonstrated in the example of Katowice conurbation in Poland from the Urban Atlas dataset.

The urban fabric is divided into the Urban Atlas data into six categories according to the density of urban fabric (

Figure 3). Codes of all these categories start with code 11xxx (from

Continuous urban fabric - 11100 to

Isolated structures - 11300). All polygons from these six categories are recoded automatically to one new class

of urban fabric in Jupyter Notebook using Python code. The next two categories,

Green urban areas (14100) and

Sports and leisure facilities (14200) are recorded as the next new class, labeled

relax. Both new classes are stored in a new polygon feature layer

urban_relax that is subsequently converted to the point layers. This first part of the Notebook is about the preprocessing of data.

The cordial is Python code cells that calculate Colocation analysis by calling

arcpy.stats.ColocationAnalysis() from

arcpy library (

Figure 4). The advantage is that the user can set and change the input parameters in Python commands, such as

distance band (400 meters),

method (Distance or K nearest neighbors), and set

number of permutations. The analysis results are visible directly in the Map window in ArcGIS Pro. In Katowice’s case, some bookmarks to interesting city places have been prepared. The colocation analysis also produces a graph of the relationship between the local colocation quotient and p-value for each explored point (

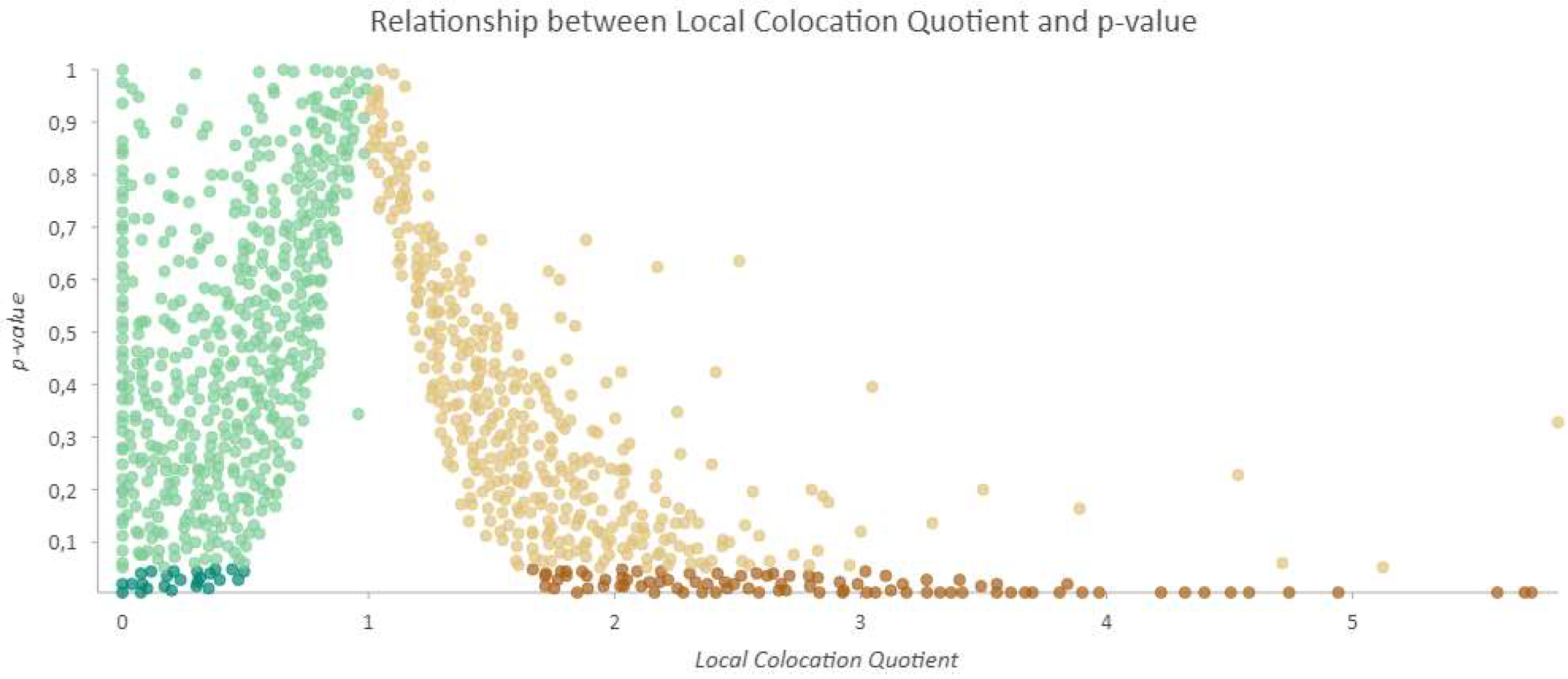

Figure 5). The same point symbology setting is used for isolated and collocated points, according to the legend in

Figure 2.

The next part of the Jupyter Notebook is the section where the results are generated with different parameter settings like distance band, number of permutations, and the weighting scheme. The local weighting scheme specifies the kernel type that will be used to provide the spatial weighting. The kernel defines how each feature is related to other features within its neighborhood. The options are Gaussian, Bisquare and none. Users can compare the resulting number of collocated or isolated points depending on the values of parameters in the same city.

3. Results

The results could be evaluated in two ways. Firstly, by a total number of significantly collocated and isolated points. An interesting part of the evaluation is exploring the localities in cities where clusters of collocated or isolated points dominate.

3.1. Katowice City

Katowice, a city in Poland, has around 280 thousand inhabitants. From whole functional urban areas, only the core was clipped. The core of the Katowice conurbation consists of several towns, like Bytom, Zabrze Chorzow, Gliwice, Sosnoviec, Swietochlowice, Myslovice, Ruda Slaska, Tychy etc. After merging categories into the urban fabric class and relax class, the inputs represent 11,745 for urban fabric and 2,400 points for relax. The reasonable distance for walking is 400 meters [

21,

22]. The base parameters for colocation analysis were:

distance band = 400 m and

permutation= 499 with

weighting scheme = Gaussian. The analysis results show that 601 points collocated significantly, 3,215 points collocated not significantly, 380 points isolated significantly, and 7,491 isolated not significantly. For the next evaluation, the most interesting points are significant.

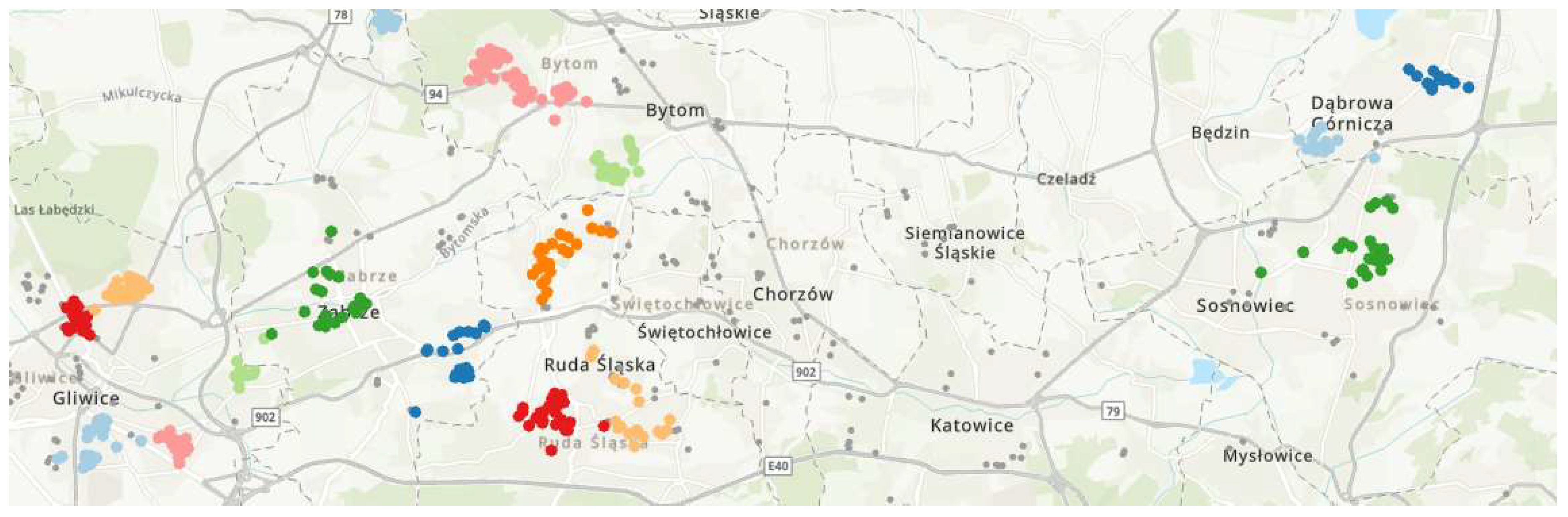

Collocated points prevail in the northwest towns, whereas the isolated points dominate mostly on the outskirts and southeast of the conurbation. Detailed examples of Gliwice and Ruda Slaska are in

Figure 6. The city of Tychy in the south is somewhat independent in this respect, and it has both collocated and isolated clusters.

The significantly isolated are points near the central railway station in Katowice (

Figure 7). There are only several very small green areas. Exploring the clusters of significantly isolated buildings with the origin land use classes helps to find the reason for the situation. In these localities, the buildings are surrounded by polygons with class 12100

Industrial, commercial, public, military, and private units (violet color) (

Figure 7b). Considering base Urban Atlas land use classes is also important when interpreting groups of isolated points of urban fabrics located on the outskirts. That case revealed that classes like meadows or arable lands surrounded low-density urban fabrics. This situation of isolated urban fabrics from green areas like parks is not crucial for people because another type of green nature surrounds them.

Finally, the investigation of all clusters to find the number and localization were explored. The clustering method DBSCAN (Density-based Clustering) from the Spatial Statistics toolbox was used in ArcGIS Pro. The HDBSCAN variant of DBSCAN was used. This method, labeled

Self-adjusting, uses varying distances to separate clusters of varying densities from sparser noise [

23]. This method needs only one input parameter – the minimum number of features per cluster. The minimum was set to 10 points in one cluster. The distance of points is not fixed in the process of clustering. All points that are not assigned to any clusters are labeled as noise (grey color).

For the Katowice conurbation, 16 clusters of significantly collocated points exist. Surprisingly, they are located in smaller towns like Gliwice, Bytom, Ruda Slaska, Zabrze and Sosnovies (

Figure 8). Directly in the Katowice, no cluster of significantly collocated points bigger than 10 exists. The 234 points were assigned as noise from the 601 total collocated points. The rest of the points crates 16 clusters.

The clustering method HDBSCAN with an input parameter minimum of 10 points in the cluster was applied to significantly isolated points. Two clusters of isolated points are identified directly in Katowice. A total of 17 isolated clusters exist in conurbation. They comprise 356 points, where 24 points remain as noise points. Two clusters of isolated points are placed directly in Katowice. This result correctly complemented the previous result of missing clusters of collocated points in the Katowice center. It means that urban fabrics are more isolated from green areas and areas for sports and leisure activities in Katowice than other towns in the conurbation.

3.2. Investigation of a Group of Similar Cities

The next investigation processes the set of cities using the same steps to find the applicability of colocation analysis. Ten European cities were processed. The cores extracted from FUAs were taken. The question is how they differ or are common in the results of colocation analysis. Ten cities were chosen based on other investigations where the similarity based on frequent item sets of neighboring of all categories was completed [

24]. Based on frequent item sets, the previous investigation considers all categories from Urban Atlas, contrary to the presented investigation of colocation, which only includes two categories. The cities are Cambridge, Worcester, Cheltenham, Hasting, Lincoln (England), Salzburg (Austria), Gouda (Netherlands), Stavanger (Norway), Bern and Basel (Switzerland).

The same parameters as Katowice conurbation were set for colocation analysis for each city. The values were

distance band = 400 m and

permutation= 499 with

weighting scheme = Gaussian. The same parameter settings allow comparison of towns. The results are visible in

Table 1. The number of colocated points is smaller than isolated points except Basel. The number of collocated or isolated points depends on the size of the town. These investigated towns are much smaller than the Katowice conurbation. In comparing these ten towns, the span of points is in the interval from 2 to 48 for significantly collocated. The span of significantly isolated points is from 0 to 96. The best situation is in Basel, where there are no isolated points of urban fabrics from green areas and areas for sports and leisure activities. So, Bern is a very livable town, according to that analysis. A detailed exploration of each town detects the specific localization of clusters.

4. Discussion

The Jupyter Notebook for processing colocation is very helpful. Besides the text explanation and step-by-step running, the variant parameter setting is possible. Moreover, the application for another city from Urban Atlas is possible.

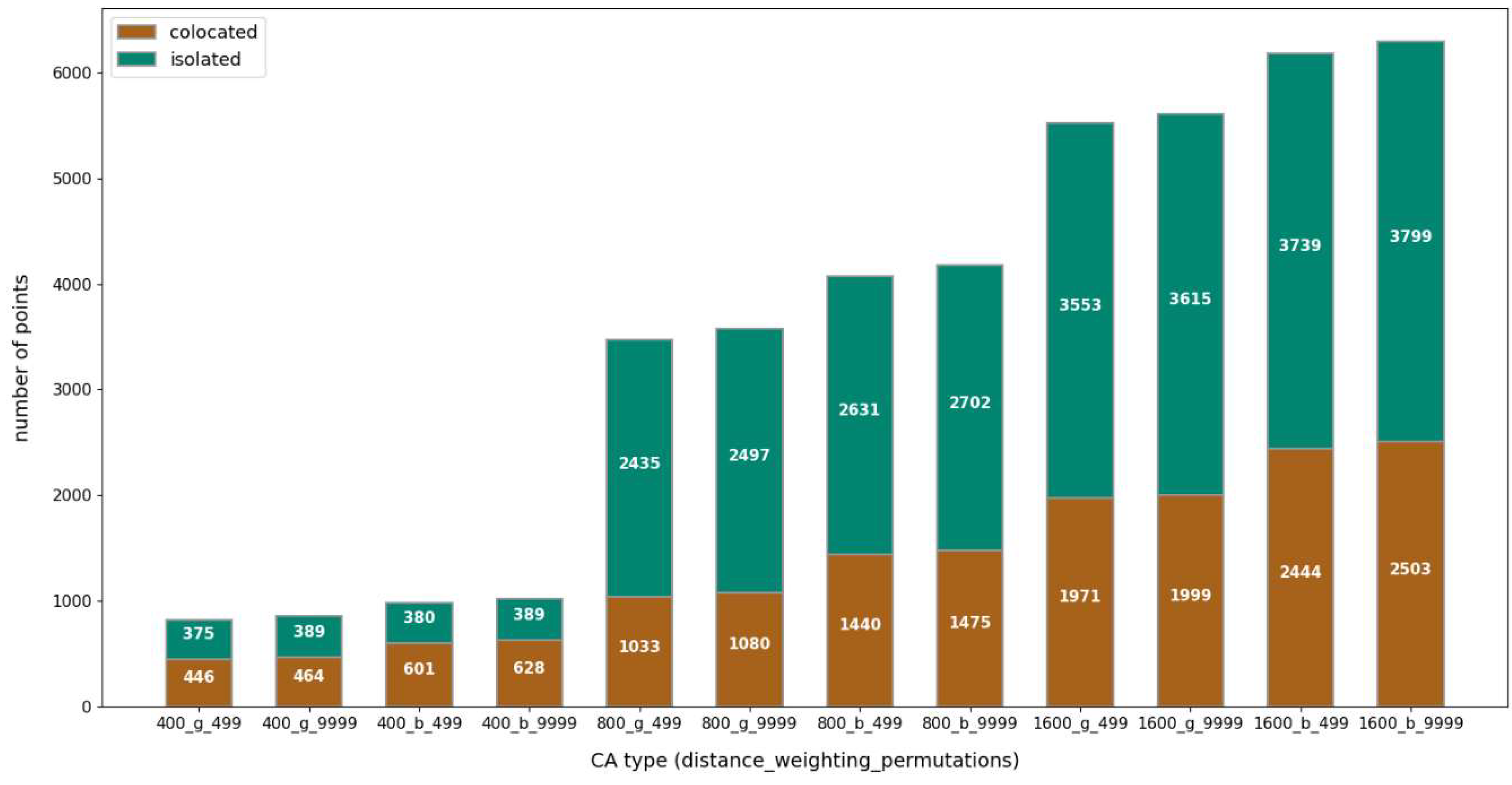

The setting of parameters has an obvious impact on results. Especially the increasing distance to the relax areas produces a higher number of colocated points. Experimentally, the distances 400, 800 and 1600 meters were set. Alternatively, two values of permutation 499 and 9999 were used. Moreover, two weighting schemes were experimented with: Gaussian and Bisquare. All combinations produce 12 results for one city. Multiple colocation analyses in the Python cycle were run to make the influence of setting parameters visible. All new collocated layers were stored in the separate map group layer. The results are presented in the table and chart in the Jupyter notebook for the Katowice conurbation. The chart is in

Figure 10.

There are three leaps in the number of points visible from the chart. The biggest one is related to the change of the distance band. The greater the distance, the greater the number of significantly collocated and isolated points. The increase from 400 to 800 meters produces nearly two times higher values. An interesting fact connected to the distance band is that with the 400-meter distance band, the number of colocated points is higher than isolated points, whereas with 800 and 1600 meters is the reverse situation, the number of isolated points is higher than collocated.

The second leap is related to the type of local weighting scheme. When the Bisquare weighting was applied, the number of points was greater than for the case of Gaussian weighting. The nature of these weighting schemes causes this. The Gaussian curve has a steeper decline in the weight assigned to neighboring points than Bisquare, which decreases the number of important neighbouring points and the significance of the LCLQ.

The last and smallest leap in the chart is related to the number of permutations. The Esri tool documentation says that with 499 and 9999 permutations, the smallest possible pseudo p-values are 0.004 and 0.0002, respectively, and all other pseudo p-values will be even multiples of this value [

17]. Using more permutations leads to a more detailed, precise p-value, which causes a slight increase in the number of collocated and isolated points. The experiment with the number of permutations verifies it. Nevertheless, the longer time the calculation takes for more permutations.

The results of the analyses also depend on the quality and detail of the underlying input data. The Urban Atlas data has a relatively large mapping unit and may not affect smaller green spaces or facilities for leisure sports activities. Including a class of Forests (31100) on the outskirts of cities could also influence the result. However, since the data is converted to a point representation, the forested areas would be converted to a single point - centroid - which may be at a greater distance than the collocation distance set. Then, the forest area would not even be considered when searching the surroundings.

The improvement and increase of green areas are not easy tasks in cities. Despite its dense urban fabric, it is hard to incorporate green areas in historical centers with medieval layouts. The initiatives try to improve the situation. The Urban Blooms Project in Innsbruck aims to bring nature into pedestrian zones and transform parts of Innsbruck’s old town into green oases with seating areas, small meadows, and play spaces [

25] .

Alternatively, another Urban Atlas data class could be used in colocation analysis. The presented investigation is oriented to the livable cities from the point of view of residents. Potentially interesting colocation could be found for these classes: 13100 - Mineral extraction and dump sites, 1330 – Construction sites, 12100 – Industrial and commercial units or 13400 – Land without current use. It could reveal spaces for the economic development of cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation Zdena Dobesova and Adam Toth; methodology Zdena Dobesova; software Adam Toth; validation Zdena Dobesova and Adam Toth; formal analysis, investigation, Adam Toth ; resources, data curation, Adam Toth; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review & editing, Zdena Dobesova; visualisation Adam Toth; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition Zdena Dobesova. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was created within the project of “Analysis, modelling, and visualisation of spatial phenomena by geoinformation technologies III” (IGA_PrF_2024_018) with the support of the Internal Grant Agency of Palacký University Olomouc.

Data Availability Statement

The source data are available under Copernicus Urban Atlas Data. The result data of collocation for Katowice city are available on Git Hub GISAdamToth/ArcGIS_Notebooks_thesis together with Jupyter notebook in package .ppkx for ArcGIS Pro. [

20]

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rypl, O.; Macků, K.; Pászto, V. The quality of life in Czech rural and urban spaces. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Owen, N.; Kerr, J.; Cardon, G.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F. Perceived neighborhood environmental attributes associated with adults’ leisure-time physical activity: Findings from Belgium, Australia and the USA. Health Place 2013, 19, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dyck, D. Associations of Neighborhood Characteristics with Active Park Use. Int J Health Geogr 2013, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, P.; Bai, X. Benefits and co-benefits of urban green infrastructure for sustainable cities: six current and emerging themes. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1039–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keniger, L.E.; Gaston, K.J.; Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A. What Are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013, 10, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.D.; Ullman, E.L. The Nature of Cities. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 1945, 242, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Nes, A.v.N. Quantitative tools in urban morphology: combining space syntax, spacematrix and mixed-use index in a GIS framework. Urban Morphol. 2014, 18, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoek, J. Towards a Mixed-Use Index (MXI) as a Tool for Urban Planning and Analysis. In Urbanism: PhD. Research 2008-2012; Hoeven, F.D. van der, Smit, Ed.; IOS Press: Delft, 2009; ISBN 9781607500773. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Chapman, J.; Christiansen, L.B.; Coffee, N.; Salvo, D.; du Toit, L.; Dygrýn, J.; et al. International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency Data Hub: Urban Atlas Available online:. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/e006507d-15c8-49e6-959c-53b61facd873 (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Copernicus, Land Monitoring Service, Urban Atlas. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/local/urban-atlas (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Prastacos, P.; Lagarias, A.; Chrysoulakis, N. Using the Urban Atlas dataset for estimating spatial metrics. Methodology and application in urban areas of Greece. Cybergeo 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, M.; Löhnertz, M.; Schröder, C.; Aksoy, E.; Fons, J.; Garzillo, C.; Wildman, A.; Kuhn, S.; Prokop, G.; Cugny-Seguin, M. 2018.

- Dobesova, Z. Experiment in Finding Look-Alike European Cities Using Urban Atlas Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2020, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koperski, K.; Han, J. Discovery of Spatial Association Rules in Geographic Information Databases. In Proceedings of the Advances in Spatial Databases; Egenhofer, M.J., Herring, J.R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Portland, ME, 1995; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, S.; Sander, J. Statistically Significant Co-Location Pattern Mining. In Encyclopedia of GIS; Shekhar, S., Xiong, H., Zhou, X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 2204–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Esri Colocation Analysis (Spatial Statistics) Available online:. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/colocationanalysis.htm (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- European Environment Agency Mapping Guide v6. 2020.

- Toth, A. ArcGIS Notebooks Creation for Data Processing of European Cities and Countries. master, Palacky University, Faculty of Science, 2024.

- Toth, A. GISAdamToth/ArcGIS_Notebooks_thesis Available online:. Available online: https://github.com/GISAdamToth/ArcGIS_Notebooks_thesis (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Poelman, H. A Walk to the Park? Assessing Access to Green Areas in Europe’s Cities; 2018; Vol.

- Dobešová, Z.; Hýbner, R. Optimal Placement of the Bike Rental Stations and Their Capacities in Olomouc. In Geoinformatics for Intelligent Transportation; Ivan, I., Benenson, I., Jiang, B., Horák, J., Haworth, J., Inspektor, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 51–60 ISBN 978-3-319-11462-0.

- Esri DBSCAN - Help Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/3.3/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/densitybasedclustering.htm.

- Dobesova, Z.; Dinh, T.; Novak, P. Exploring Urban Land Use Patterns by Pattern Mining and Unsupervised Learning. in print.

- Weittenhiller, C. Urban Blooms: Oasis in Innsbruck’s Old Town Available online:. Available online: https://www.innsbruck.info/blog/en/art-culture/urban-blooms-oasis-in-the-old-town-of-innsbruck (accessed on 20 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).