1. Introduction

In the recent decades, an increasing use of fossils have raised the level of greenhouse gases (GHG), especially carbon dioxide (CO

2), in the atmosphere. CO

2 concentration in atmosphere has increased from 280 ppm, from the inception of an industrial era, to an alarming 410 ppm [

1,

2,

3]. Worldwide efforts are being devoted to curb excess amount of CO

2 from atmosphere to minimize its detrimental effect such as global warming. Carbon capture utilization and sequestration (CCUS) is a process to achieve net zero carbon emission either by CO

2 sequestration or by utilizing CO

2 as a raw feed stock to produce chemical and fuels [

4]. Electrochemical conversion of CO

2 into value added chemicals is emerging as a potential technology [

5]. Electrochemical reactor or electrolyzer is used to study electrochemical CO

2 reduction reaction (eCO

2RR), and some popular electrolyzers include a batch-cell, H-cell (with and without flow), flow electrolyzer (with catholyte), zero-gap membrane electrode assembly (MEA), and microfluidic reactor [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Despite substantial research in the field of electrochemistry, there are some bottlenecks such as CO

2 carbonation [

10,

11,

12,

13] and gas diffusion layer (GDL) flooding [

14,

15,

16,

17] that are preventing its realization to industrial scale. Besides a good catalyst, a robust electrolyzer design is required for optimal cell performance.

Electrochemical reduction of CO

2 is a complex physical phenomenon. It includes simultaneous physical and chemical processes such as hydrodynamics in free and porous media, mass transfer, heat transfer, gas/liquid two phase flow, gas/liquid inter-phase mass transfer, chemical and electrochemical reactions, and charge conservation. A comprehensive numerical model is required to address the intricacy associated with an electrolyzer operation. An early attempt was made by Gupta et al. [

18] by presenting a mathematical model for the estimation of local CO

2 concentration and local pH in a boundary layer over a planar electrode at a certain current density. Hashiba et al. [

19] presented a 1-D model for the aqueous system, assuming 100% CH

4 faradaic efficiency, with 100

m thick hydrodynamic boundary layer near the working electrode. This model was used to demonstrate the effect of electrolyte buffer capacity on CO

2 mass transport and pH profile within the boundary layer. Corpus et al. [

20] coupled the continuum model, 1-D planar electrode model with associated boundary layer, with covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy (CMA-ES) scheme to identify the kinetic rate parameters in Tafel equation without mass transfer limitation effect. Traditional method for obtaining the kinetic rate parameters is accompanied by unquantifiable errors that leads to overprediction of current density. Bui [

21] developed 1-D transient boundary layer model with copper (Cu) planar electrode to study pulsed CO

2 electrolysis. This work established that pulsing dynamically changes pH and CO

2 concentration near solid Cu electrode, which favors C

2+ products. Qui et al. [

22] developed 2-D transient models for batch-cell, planar flow cell, and gas diffusion electrode (GDE) flow cells to study the temporal and spatial variations in local CO

2 concentration and its effect on product selectivity, mainly alcohols. Other than batch-cell and H-cell, numerical models for CO

2 reduction in flow-electrolyzers have been reported in the literature, as well. Whipple et al. [

23] developed a 2D numerical model for microfluidic electrolyzer to evaluate catalyst under various cell operating conditions, and to study the effect of pH on reactor efficiency. Weng et al. published three numerical models for flow electrolyzers: a 1-D GDE model [

24], represents the cathodic section of flow-electrolyzer, with silver (Ag) catalyst to demonstrate the superiority of GDE over planar electrode, zero-gap membrane electrode assembly (MEA) model [

25] with Ag catalyst to study gas-fed (full-MEA) and liquid-fed (exchange-MEA) configurations, and this model was extended to include copper (Cu) kinetics [

26]. Kas et al. [

27] developed the 2-D numerical model for GDE to emphases on the concentration gradients in the flow channels. Ehlinger et al. [

28] used 1-D planar electrode model to fit the kinetics for hydrogen formation from bicarbonates; subsequently, kinetic parameters from planar electrode model were simulated in 1-D MEA model to study flooding and to perform sensitivity analysis of MEA design and operating parameters. Besides, in numerous studies numerical modeling is used to support experimental findings such as carbonation, water management, local pH and species concentration, and electrolyzer optimization [

14,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Aforementioned references in the literature are about planar electrode (solid electrode) in batch-cell or H-cell, or flow type H-cell, and GDE in H-cell with flow configuration or in flow electrolyzers including microfluidic cell, flow electrolyzer with catholyte and zero-gap MEA. Despite the limited utility of batch-cell in the field of electrochemistry, its significance in the characterization of electrocatalyst cannot be forsaken/undermined, however, a limited number of modeling and optimization studies are available on batch-cell compared to the wealth of knowledge on flow electrolyzers. To date, there is no study available in literature on the numerical modeling of batch-cell with working electrodes other than planar electrode, whereas, most of the researched electrocatalysts are available in nano-particle form [

5,

36,

37] that requires some support in order to be tested in an electrolyzer. Gas diffusion layer electrode (GDLE), and glassy carbon electrode (GCE) are employed to support electrocatalyst available in nano-particle form [

38]. Generally, batch-cell has three electrodes including working electrode (WE) where CO

2 reduction takes place, counter electrode (CE) completes the circuit, and reference electrode (RE) that provides control over WE. Batch-cell modeling with different working electrodes could provide useful insight regarding local species concentration that influences the rate of eCO

2RR.

In this study, a 1-D, steady state, isothermal, single-phase numerical model is developed for batch-cell with three different WEs including solid electrode (SE), glassy carbon electrode (GCE), and gas diffusion layer electrode (GDLE) [

39,

40]. Numerical model is validated with the experimental results of CuAg

0.5Ce

0.2 catalyst, developed indigenously in our lab, in a batch-cell with GCE. Numerical model is further tested with the published experimental results of Ebaid et al. [

41] for CO

2 reduction over Cu foil in a gas-tight electrolyzer with anion exchange membrane separating cathode and anode. Experimental setup details of the former catalyst including catalyst synthesis, batch-cell operation, and results analysis are reported in the supplementary information. Numerical model is then used to investigate total current density (TCD) behavior with variation in batch-cell parameters including boundary layer thickness, CL porosity, CL thickness, nature of an electrolyte and electrolyte strength. This study provides information to the experimentalist regarding the selection of working electrode, and the critical analysis of key parameters associated with the batch-cell that could be adjusted for desired performance.

Although, numerical model demonstrates the complex physical and chemical processes inside the boundary layer and the porous catalyst layer (GCE, GDLE), and it shows good agreement with experimental findings, but some assumptions have been adopted in the model that should be replaced in future work with relevant physics to capture even more realistic results. In batch-cell experiments, CO

2 saturated electrolyte is the only source of CO

2, and CO

2 concentration decreases with time, while in the model CO

2 concentration is fixed at the interface of bulk of an electrolyte and boundary layer. Boundary layer thickness is a strong function of stirring speed, higher stirring speed results in a thinner boundary layer and vice versa is possible, but in the model boundary layer thickness is adopted from the literature [

7,

21,

24,

27,

42], and the impact of various boundary layer thickness have been discussed in detail. Cu based electrocatalysts are known for producing range of gaseous and liquid CO

2 reduction products. During the batch-cell operation, there is a high probability that some of the CO

2 reduction products interact with each other, and influence pH, CO

2 solubility, and species transport. To avoid the model complexity, it is assumed that liquid products do not participate in any reaction. Temperature variations are common in a batch-cell mainly due to the application of applied voltage and heat of reactions, and it could impact the rate of eCO

2RR, however, isothermal conditions have been assumed for this study. This discussion highlights potential pathways in batch-cell modeling research work.

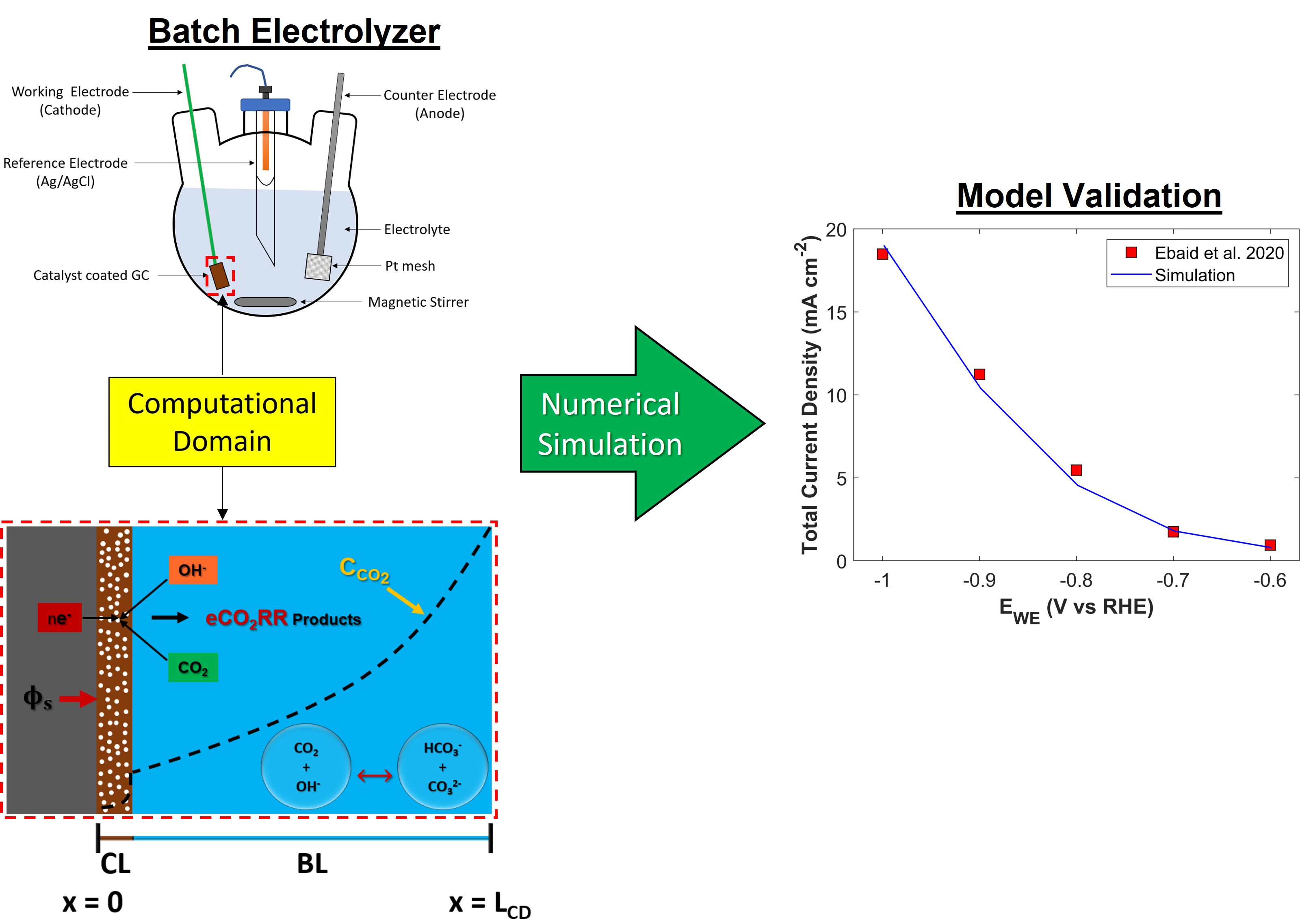

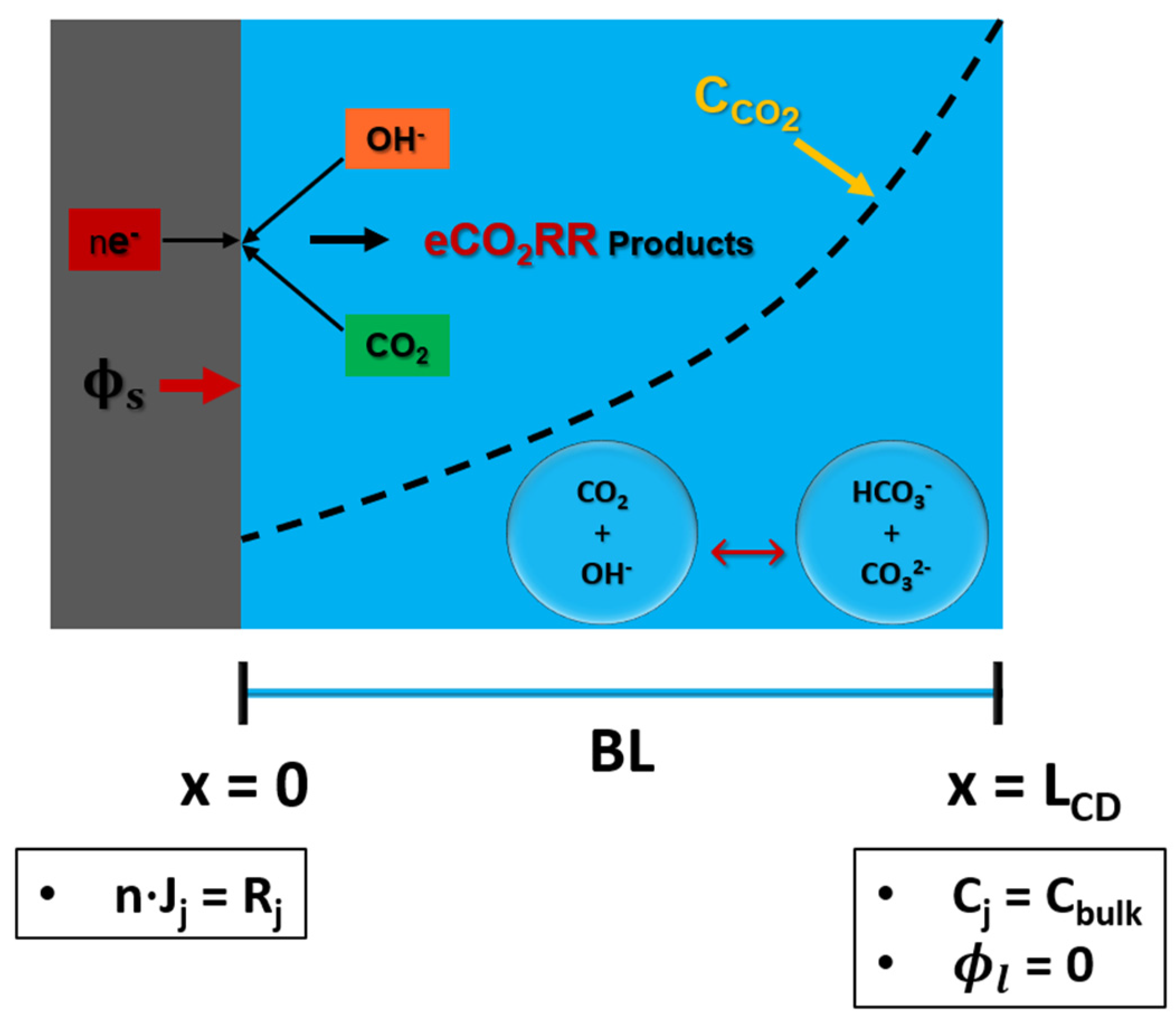

2. Numerical Model

The region of interest for numerical modeling in batch-cell is a WE (glassy carbon electrode), where CO

2 is reduced. GCE has a solid flat surface, coated with CL. Boundary layer (BL) is formed on the surface of catalyst that governs mass transfer of species between bulk of an electrolyte and WE, while bulk of an electrolyte achieves uniformity due to constant stirring. Therefore, computational domain (CD) for GCE has two important regions: porous catalyst layer (CL), and BL. A schematic of CD is shown in the

Figure 1 with all the necessary boundary conditions. The CD is modeled as 1D.

A comprehensive numerical model is developed to deconvolute the physio-electrochemical phenomenon such as mass transfer due to diffusion and electromigration, charge conservation, electrochemical reaction, and chemical reactions in the CD. A total of 6 species have been modeled: dissolved CO

2, hydroxyl ions (OH

-1), bicarbonate ions (HCO

31-), carbonate ions (CO

32-), protons (H

+), and potassium ions (K

+). Catalyst used in this study reduces CO

2 to five different products with higher selectivity for C

2+ products: carbon mono-oxide (CO), methane (CH

4), ethylene (C

2H

4), ethanol (C

2H

5OH), and propanol (C

3H

7OH). Alongside these products, a competing parasitic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) also takes place. The electrochemical reaction for each of these products is given in the

Table 1 [

36]. It is assumed that gaseous products (H

2, CO, CH

4, C

2H

4) bubble out as soon as they are produced, while liquid phase products act as neutral species, and do not participate in any reaction. Water (H

2O) is assumed to be ubiquitous specie in CD; therefore, it is not included in the modeling. Electrolyte is a 1 M KOH solution. Besides electrochemical conversion of CO

2 into useful products, a considerable amount of CO

2 reacts reversibly with the hydroxyl ions (OH

-1) to produce bicarbonates (HCO

3-1), and carbonates (CO

32-) ions. These reactions govern local pH in CD. Due to high pH (~1 M KOH pH=14) of an electrolyte, only the reactions in the

Table 2 have been considered in the model [

43]. Precipitation of bicarbonate (KHCO

3), and carbonate (K

2CO

3) salts are ignored in the numerical model. Although, salt build-up has a substantial deteriorating effect on the CL [

11,

12] and it also increases required cell potential if experiment is carried out for extended period [

10], but in case of batch-cell modeling, this phenomenon can be ignored as a fresh electrolyte solution is used for each batch cell experiment [

12].

Specie balance is used to model concentration of species in the CL, and the BL.

N

j describes the molar flux of specie j in CD, while source terms on the right hand represents the consumption and the generation of species due to chemical and electrochemical reactions, respectively. Nernst-Planck equation is invoked for the molar flux of species in CD [

40].

First term on the right-hand side is the diffusion of species according to the Fick’s law, while the second term represents the electro-migration of charged species; therefore, the second becomes zero for neutral species such as dissolved CO

2. The diffusion of species in porous CL is corrected using Bruggeman correlation [

44]. The effective diffusion coefficient (

) of species in porous CL depends on its porosity (

), and tortuosity (

).

An additional equation is required for electrolyte potential (

) to close the degree of freedom; therefore, electroneutrality equation is included in the model.

Nernst-Planck equation assumes dilute-solution theory [

24,

40]. Modeled domain is not dilute under specified conditions; however, it is a reasonably good assumption as the TCD is around 100 mA cm

-2. Concentrated solution theory requires additional diffusion coefficients which are not available in the literature.

The chemical consumption/generation term is defined as follows;

is the stoichiometric coefficient. It is negative for reactant species, and positive for product species. and are the forward and the reverse reaction rate constants, respectively. is an equilibrium constant.

The electrochemical source term in specie balance is defined as;

The term (

) represents molar weight of species.

is the effective surface area available for CO

2 reduction in porous CL domain,

represents the electron transferred in each reaction

,

is the partial current density, and F is the Faraday’s constant. The electrode kinetics or electrochemical reaction kinetics are modeled using concentration dependent Butler-Volmer (BV) equation [

45]. The BV equation describes both anodic half reaction, and cathodic half reaction. The BV equation reduces to Tafel equation that describes the electrochemical conversion of dissolved CO

2 into products at WE. A detailed derivation of the Tafel equation is provided in the supplementary information. The final form of the Tafel kinetic equation used in the model is;

This formulation of Tafel kinetic equation is adopted from Bui [

21]. Tafel equation has several unknown parameters that are either the direct inputs to simulation or obtained through data fit to experimental findings.

is applied cell voltage, while

is evaluated by solving Nernst-Planck equation, and electroneutrality equation (see equation 2, and 5).

is the thermodynamic potential available in literature for almost all product species.

represents the reaction order of CO

2 for specific product specie. It could be obtained either through experimental data fitting of CO

2 reduction at various applied potential as reported in previous studies by Weng [

25] or through rigorous microkinetic modeling discussed by Rae [

42]. According to the density functional theory (DFT) calculations,

is the number of elementary steps in reduction of CO

2 towards certain product specie [

21], which is the most simplified way to obtain this parameter. In this model,

for all product species are taken from the reference [

21], and it is listed for each CO

2 reduction product in

Table 4.

is the pH rate ordering parameter. It is evaluated through experimental data fit of current density vs. pH at a specified applied voltage [

21].

values for each CO

2 reduction product are listed in

Table 4.

and

are local CO

2 concentration, and local pH, respectively. These values are quite challenging to obtain experimentally; therefore, simulation is performed using experimental input to get these values.

is the reference concentration that is set to 1 M.

is the transfer coefficient, while

is the exchange current density. More on these parameters will be discussed in the next section.

Charge conservation in CD is modeled using the following equations.

Ohm’s law is used to define the relation between current and voltage.

reparents the conductivity solid catalyst, and liquid electrolyte. In porous CL, effective conductivity is used according to the Bruggeman correlation.

Concentration of dissolved CO

2 in 1 M KOH at STP is 24.57 mM. It is estimated using Henry’s law, and it is corrected for electrolyte strength using Sechenov’s constants [

46].

is the Henry’s constant for CO

2, which is defined as [

47,

48];

In case of an electrolyte with high concentration of ions, solubility of CO

2 is reduced. Reduced CO

2 solubility in an electrolytic solution is evaluated using Sechenov’s constants [

46].

is the Sechenov’s constant, and

is the molar concentration of ions. Sechenov’s constants value are provided in

Table 3.

At x=L

CD, the concentration of species is set to the bulk of an electrolyte. CO

2 starts diffusing from the interface of BL and bulk of an electrolyte to reach the surface of CL, where it undergoes eCO

2RR. Since, CL is a porous domain, it offers more active sites for CO

2 reduction, but due to intricate network of pores, diffusion of CO

2 inside CL is reduced. The nature of eCO

2RR products depend on the catalyst. The thickness/length of BL is about 100

[

21]. However, this value changes with the stirring speed (in RPM). Voltage (

) is applied at x=0, whereas it is assumed that RE is located at the interface of BL and bulk of an electrolyte (x=L

CD), where electrolyte potential is set to zero (

). Moreover, steady state, and isothermal conditions have been assumed.

2.1. Kinetic Parameters from Experimental Data

In this section, Tafel equation parameters for each CO

2 reduction product are obtained from the experimental data. Experimental data is provided in

Table S1 (refer to supplementary information). Tafel kinetic equation discussed in the last section (see equation 9) is used to estimate kinetic parameters. Equation 9 has six unknown parameters including

,

,

,

,

,

. Parameter values for

, and

are provided in

Table 4. Parameters

, and

are listed in

Table 5.

, and

values are reported in

Table 6.

Local CO

2 concentration, and pH values are estimated by simulating experimental data. Experimental TCD is set as a boundary condition. Mass flux boundary condition, estimated from experimental partial current density (PCD), is used for dissolved CO

2 and hydroxyl ions (OH

-1) species balance. In this way, local average CO

2 concentration, and local average pH values are estimated in CD. These values are provided in

Table 5.

Remaining two parameters

, and

are obtained through comparing with experimental data. Information provided in

Table 4, and

Table 5 is used to evaluate the normalized current density.

Tafel equation is simplified as;

The slope, and the intercept of the equation 23 provide

, and

, respectively. Normalized current density plots as a function of overpotential for each experimentally recorded CO

2 reduction product are shown in

Figure S3.

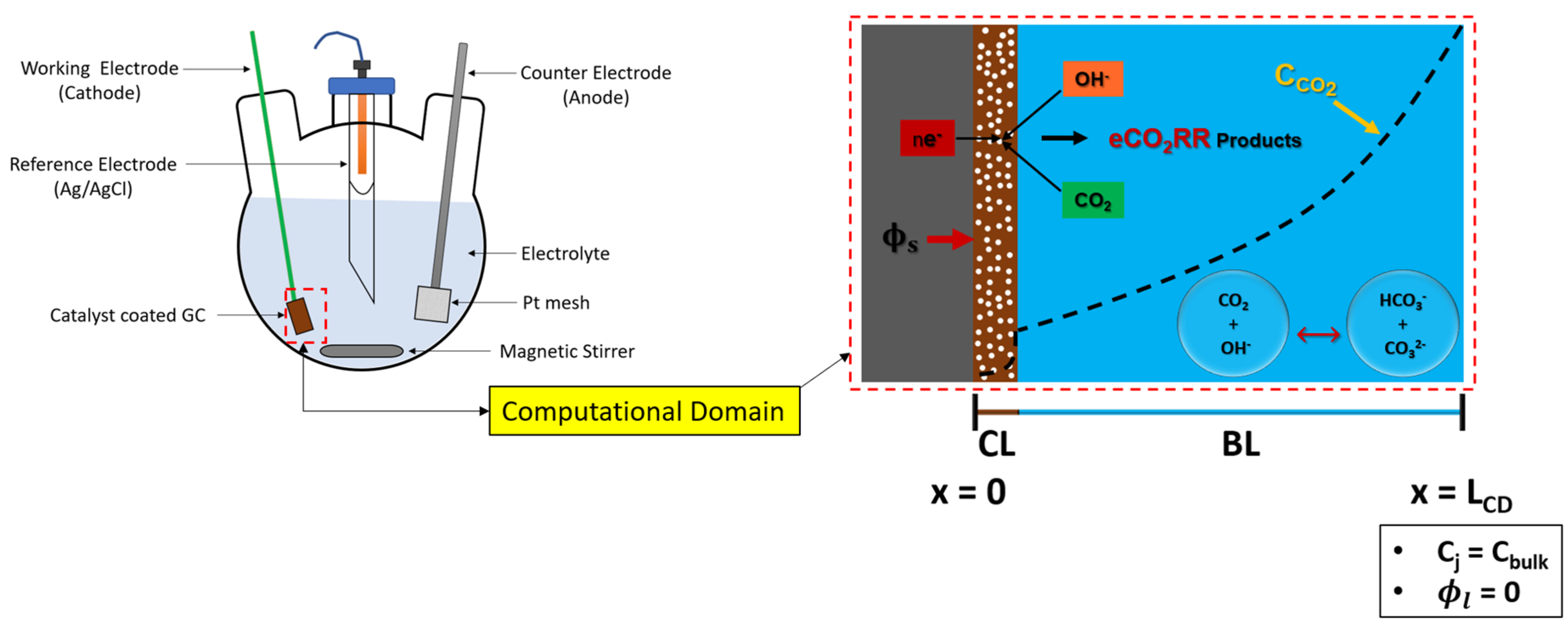

2.2. Numerical Model for Solid Electrode (SE) and Gas Diffusion Layer Electrode (GDLE)

In this section, numerical model for other two WEs have been presented: solid electrode (SE), and gas diffusion layer electrode (GDLE). In practical, SE is made up of a single metal such as copper (Cu), but, in this study, it is assumed that SE is made-up of catalyst CuAg0.5Ce0.2 used in the experiments. GDLE is a GDL paper that contains both macro pores (carbon fibers), and micro pores (carbon powder). A layer of catalyst is coated on top of micro pores layer of GDL paper. Electrochemical kinetic parameters obtained in the previous section are used to simulate both electrodes.

2.2.1. Solid Electrode Numerical Model

A schematic of CD for SE is shown in

Figure 2. There is only boundary layer (BL) in the CD of SE. CD contains six species: dissolved CO

2, OH

-, HCO

3-, CO

3=, H

+, K

+. Concentration of these species is set to the bulk of an electrolyte at (x=L

CD). CO

2 diffuses from the interface of BL and the bulk of an electrolyte (x=L

CD) to reach the surface of the electrode. Electrochemical reaction happens at the surface of the electrode (x=0). Therefore, Neumann flux boundary condition is used to model the consumption and production of CO

2 and OH

- ions at the surface of an electrode (x=0), respectively. Voltage (

) is applied at surface of the electrode, while electrolyte potential (

) is set to 0 at x=L

CD, assuming that RE is placed at this location. In case of SE, length of the CD is similar to the thickness of the BL, and the length of the CD is 100

m. All the other parameters are similar to the GCE.

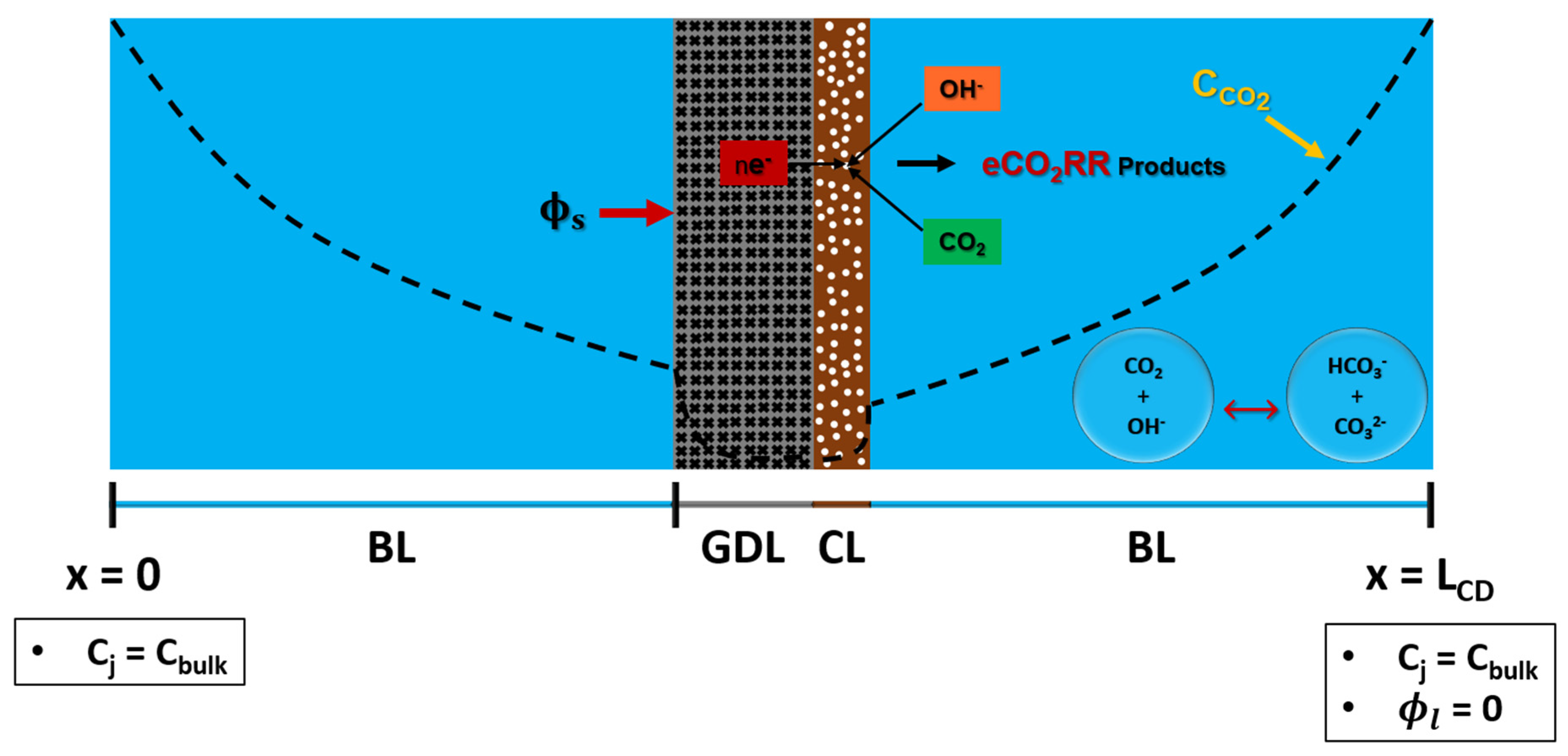

2.2.2. Gas Diffusion Layer Electrode Numerical Model

GDLE has a porous structure. Gas diffusion layer (GDL) paper has a layer of macro pores (carbon fibers), and a thin layer of micro pores (carbon power). However, it is assumed that GDL paper has a uniform structure with same pore size, and it has isotropic porosity. CL that is coated on top of GDLE has a porous structure, as well. GDLE computational domain is shown in

Figure 3. Porous nature of GDLE allows reactant species to diffuse from both front (with catalyst layer), and back (without catalyst layer). CD has 4 regions: two boundary layers, porous GDL, and porous CL. CD contains dissolved CO

2, OH

-, HCO

3-, CO

3=, H

+, and K

+. Concentration of species is set to bulk on an electrolyte at x=0, and x=L

CD. CO

2 diffuses from both ends of the CD to reach CL, where it undergoes eCO

2RR. GDL serves two important functions: it supports the CL, and acts as a medium for electronic conductor. Voltage (

) is applied at the interface of GDL/BL. It is assumed that RE is located at x=L

CD, and the electrolyte potential (

) at this location is set to zero.

2.3. Numerical Simulation

Numerical model developed in this study is simulated using COMSOL Multiphysics v6.1 environment. COMSOL uses finite element technique to discretize the differential equations. MUMPS direct general solver is used to solve set of algebraic equations (Ax=B). Total number of nodes in CD are 200; number of nodes in CL domain, and BL domain are set to 150, and 50, respectively. Information required to simulate the model is provided in

Table 6.

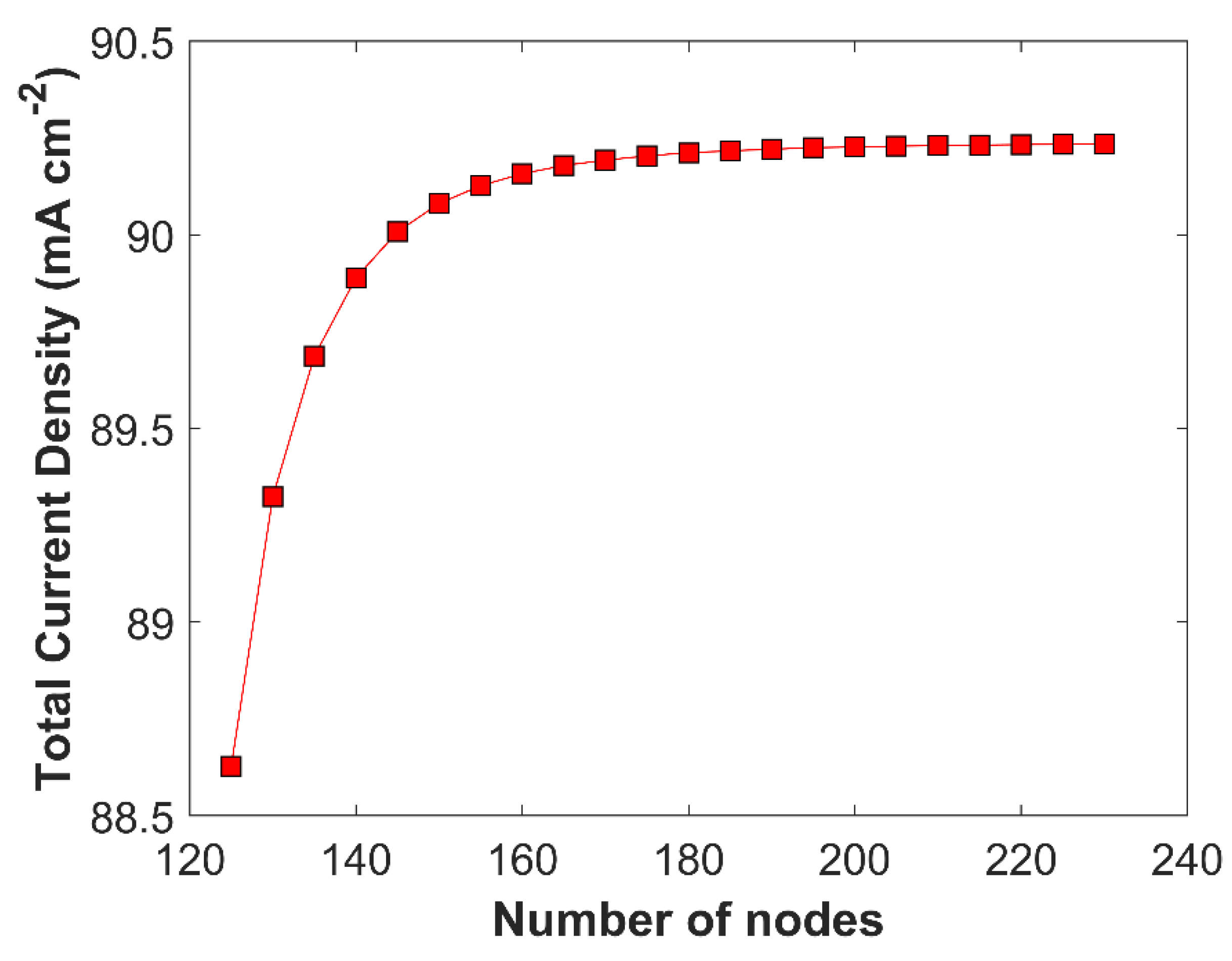

Grid independent study is performed to check the model consistency and robustness. CL domain is more sensitive to species concentration gradient than the BL domain, as eCO

2RR happens inside the pores of CL; therefore, smaller element size (0.30

m) is used CL domain, comparing with BL domain with relatively bigger element size (0.67

m). Grid independent solution is obtained when the variation in the TCD, at a fixed applied cathodic voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE, goes below 1% by increasing number of nodes (decreasing element size) in CD. Grid independent solution is shown in

Figure 4.

2.4. Numerical Model Validation

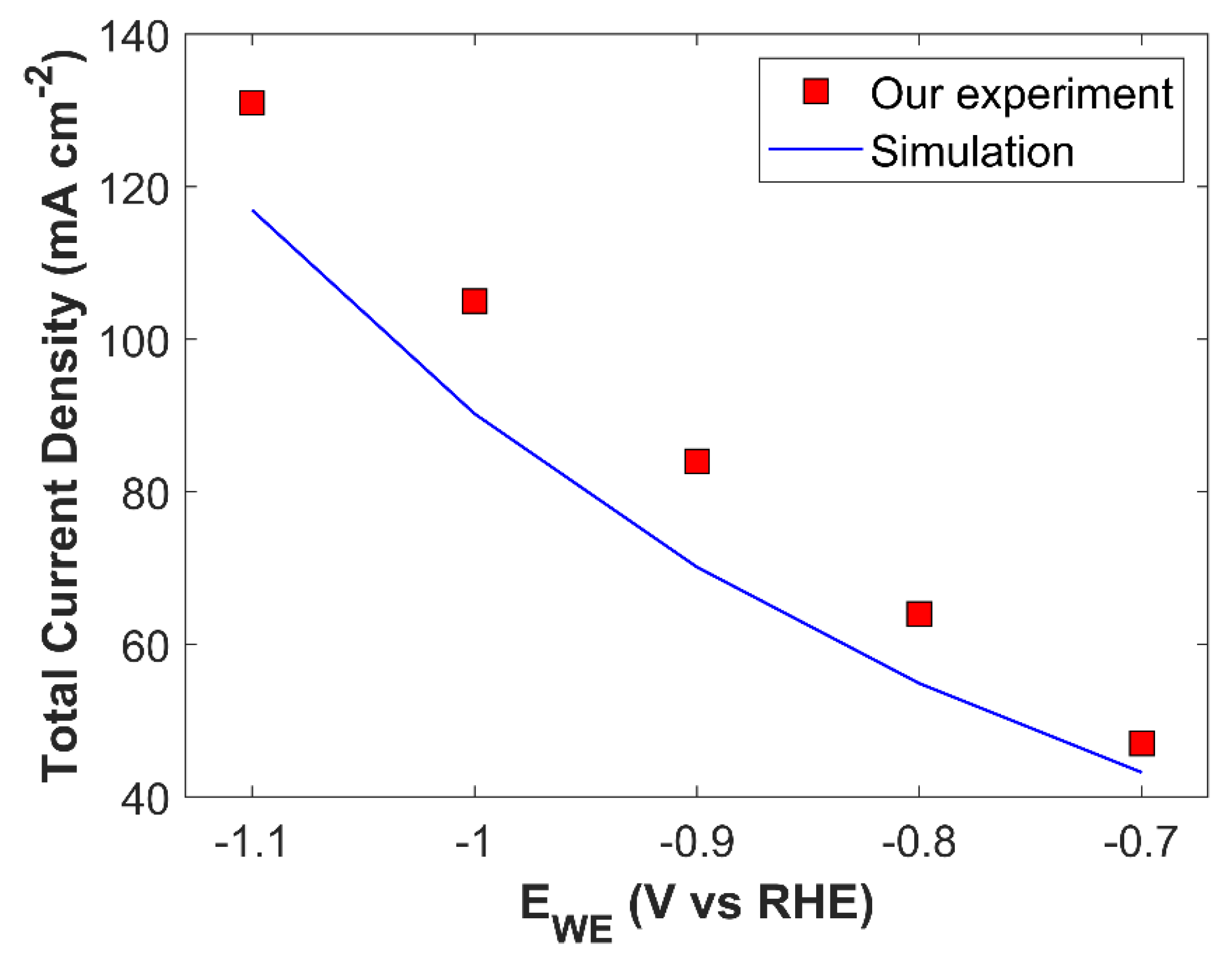

Numerical model is validated by comparing simulation TCD result with experimental data, see

Figure 5. Numerical model shows a good agreement with experiment, however there is a slight difference in simulated TCD slope and experimental TCD slope. Numerical model predicts TCD with positive slope, however, the slope of experimental data shows a decreasing trend with the increase in applied cathodic voltage. In experiments, electrolyte saturated with CO

2 is used, and batch-cell is sealed for the duration of an experiment. Concentration of dissolved CO

2 in an electrolyte becomes a function of time, and the concentration of CO

2, which is 24.57 mM in 1 M KOH at STP, keeps on decreasing. This physical phenomenon is not catered in the simulation, and it is simply replaced with a Dirichlet concentration boundary condition. This assumption maintains a relatively higher, and constant concentration gradient for CO

2 at a certain applied cathodic voltage, than the experiments where mass transfer resistance increases with decreasing CO

2 concentration in the bulk of an electrolyte. Therefore, decreasing slope trend for experimental current density is due to scarce supply of CO

2, which becomes significant at higher applied voltages. Furthermore, use of raw technique for kinetic parameter estimation, and incapability of 1-D model to fully describe underlying physics could also affect the numerical simulation results. Despite the simplification of the numerical model, it is able to predict TCD with quite a good accuracy.

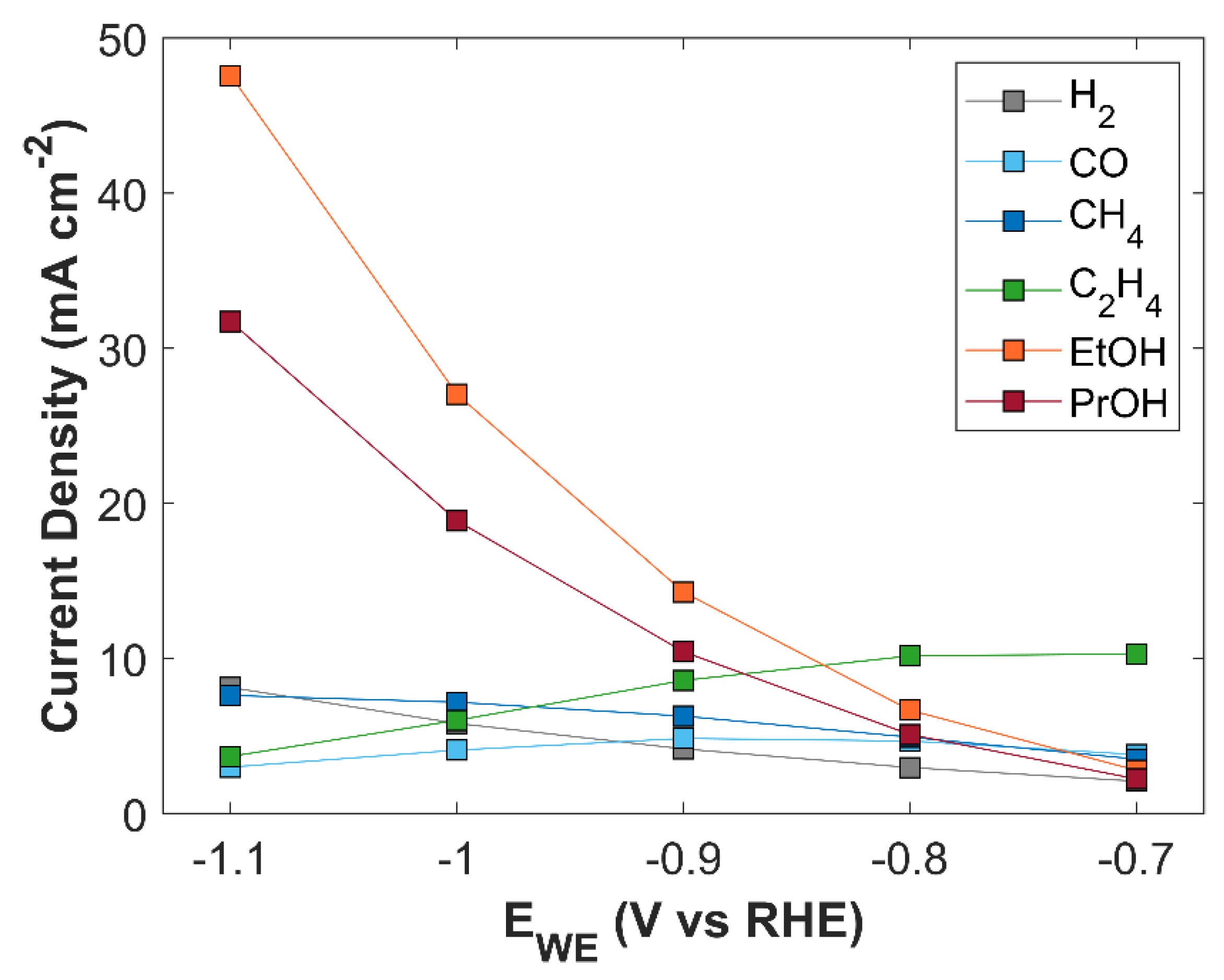

A comparison of simulated PCD of eCO

2RR products with experimental findings is shown in

Figure S4. Except for ethylene, all the individual current density shows a good match with experiment. Experimental data for ethylene shows irregular behavior, especially the data point at -0.7 V vs RHE and -1.0 V vs RHE, which are significantly away from the normal trend.

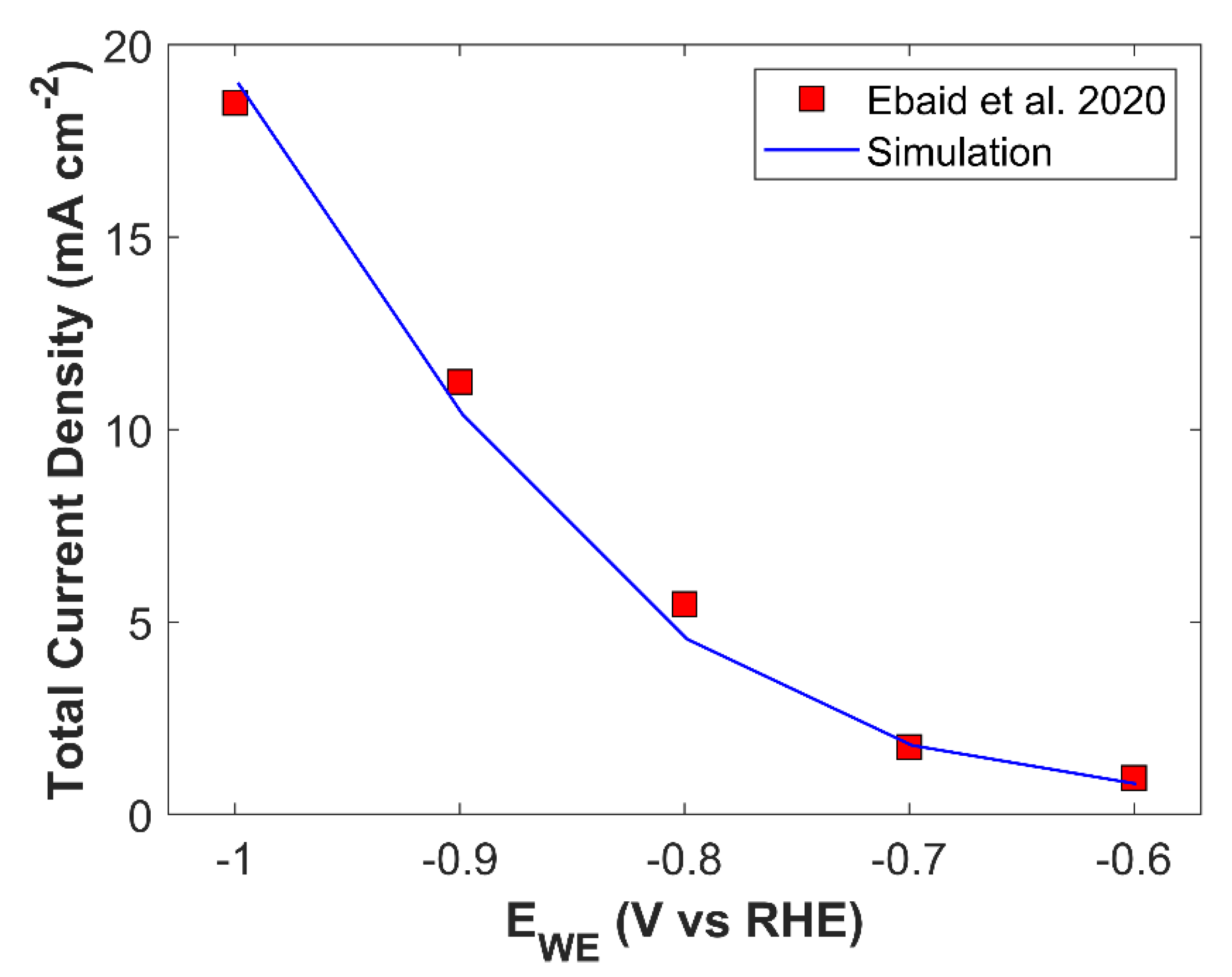

Numerical model developed in this study is also validated with the experimental findings of Ebaid et al [

41]. CU foil and graphite rod was used as a working electrode and counter electrode, respectively. Electrolyte was 0.1 M CsHCO

3 saturated with CO

2. Validation results for TCD and PCD are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure S5, respectively.

Table 6.

Batch-cell model parameters.

Table 6.

Batch-cell model parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

Unit |

Reference |

| Design Parameters |

| LCL

|

15 |

|

Experimental input |

| LBL

|

100 |

|

Fitted |

| LGDL

|

325 |

|

Experimental input |

| T |

298 |

K |

This study |

| EWE

|

-0.7 – -1.1 |

V vs RHE |

| |

|

|

|

| Electrochemical Kinetic Rate Parameters for CuAg0.5Ce0.2 Catalyst |

|

|

97.3 |

mA cm-2

|

This Study |

|

8.89 x 108

|

mA cm-2

|

|

9.50 x 105

|

mA cm-2

|

|

2.8 |

mA cm-2

|

|

4.10 x 10-2

|

mA cm-2

|

|

9.50 x 10-3

|

mA cm-2

|

|

0.0274 |

|

|

0.1001 |

|

|

0.1391 |

|

|

0.1222 |

|

|

0.1490 |

|

|

0.1676 |

|

|

0 |

V vs RHE |

[36] |

|

-0.11 |

V vs RHE |

|

0.17 |

V vs RHE |

|

0.07 |

V vs RHE |

|

0.08 |

V vs RHE |

|

0.09 |

V vs RHE |

| |

|

|

|

| Chemical Reaction Rate Parameters |

|

5.93 x 10-3

|

m3 mol-1s-1

|

[27] |

|

1.0 x 10-8

|

m3 mol-1s-1

|

[27] |

|

0.04 |

s-1

|

[24] |

|

56.281 |

s-1

|

[24] |

|

0.001 |

mol L-1s-1

|

[26] |

|

1.34 x 10-4

|

s-1

|

[27] |

|

2.15 x 10-4

|

s-1

|

[27] |

|

9.37 x 104

|

L mol-1s-1

|

[24] |

|

1.23 x 1012

|

L mol-1s-1

|

[24] |

|

1.0 x 1011

|

L mol-1s-1

|

[26] |

| |

|

|

|

| Porous Media Properties |

|

0.72 |

|

This Study |

|

0.3 |

|

This Study |

|

220 |

S m-1

|

[24] |

|

100 |

S m-1

|

[24] |

|

1.0 x 107

|

m-1

|

This Study |

| |

|

|

|

| Liquid Species Diffusion Coefficients |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[49] |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[49] |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[50] |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[50] |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[51] |

|

|

m2 s-1

|

[51] |

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, numerical model is used to study the effect of critical parameters of batch-cell. Numerical model is simulated using the kinetic parameters of CuAg

0.5Ce

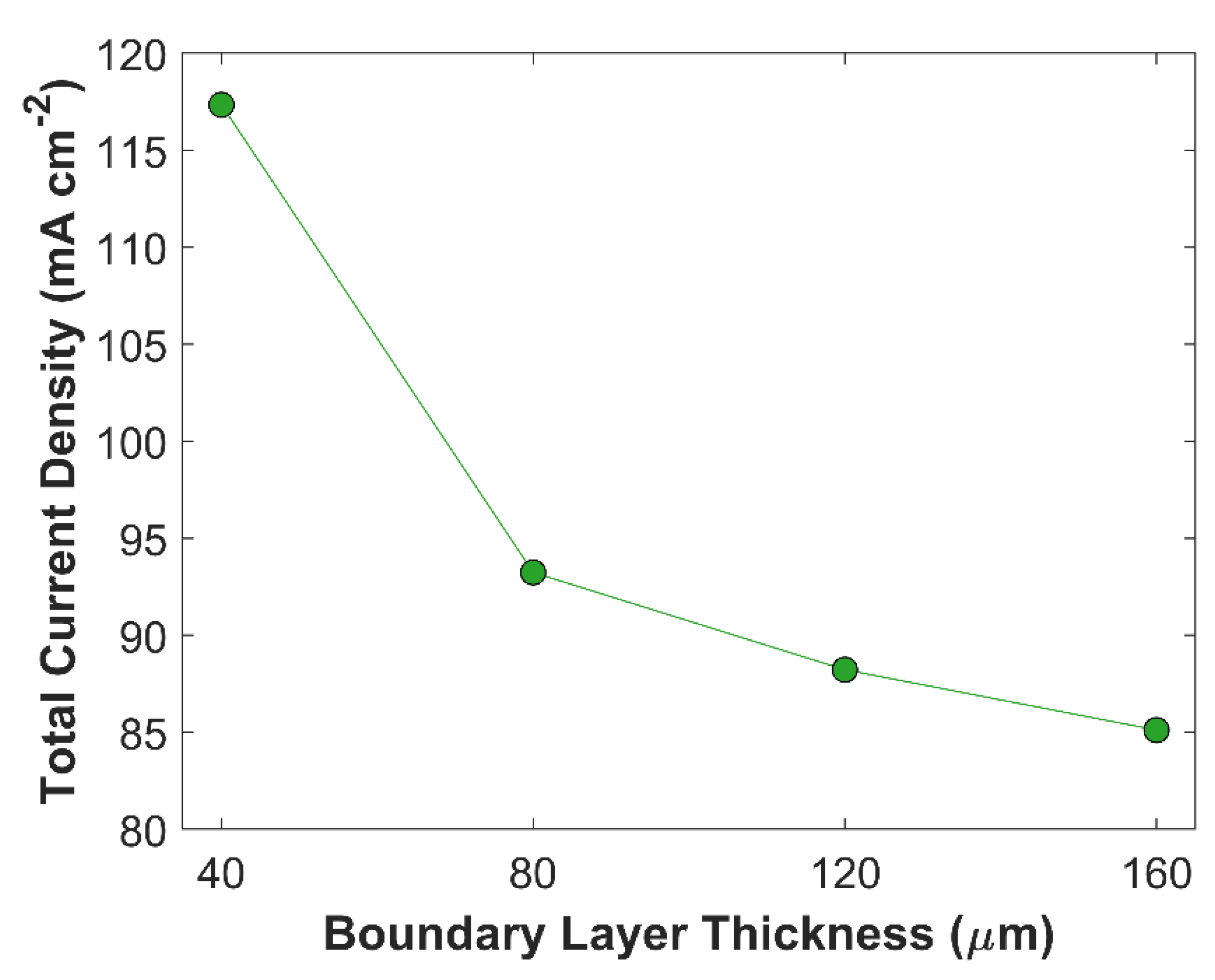

0.2 catalyst for all the case studies. Boundary layer thickness is the key parameter that controls the diffusion of CO

2, and limits TCD. At lower applied cathodic voltages, sufficient amount of CO

2 is available for eCO

2RR at CL. However, the rate of eCO

2RR increases exponentially, according to the Tafel kinetics, with the increase in applied cathodic voltages, and TCD plummets due to an imbalance between the rate of eCO

2RR and the CO

2 mass transfer. Thicker boundary layer in batch-cell offers significant resistance to CO

2 diffusion. It does not only increase diffusion time of CO

2 to reach catalyst surface; the probability of CO

2 consumption by side reactions also increases, even further reducing effective concentration of CO

2 available for eCO

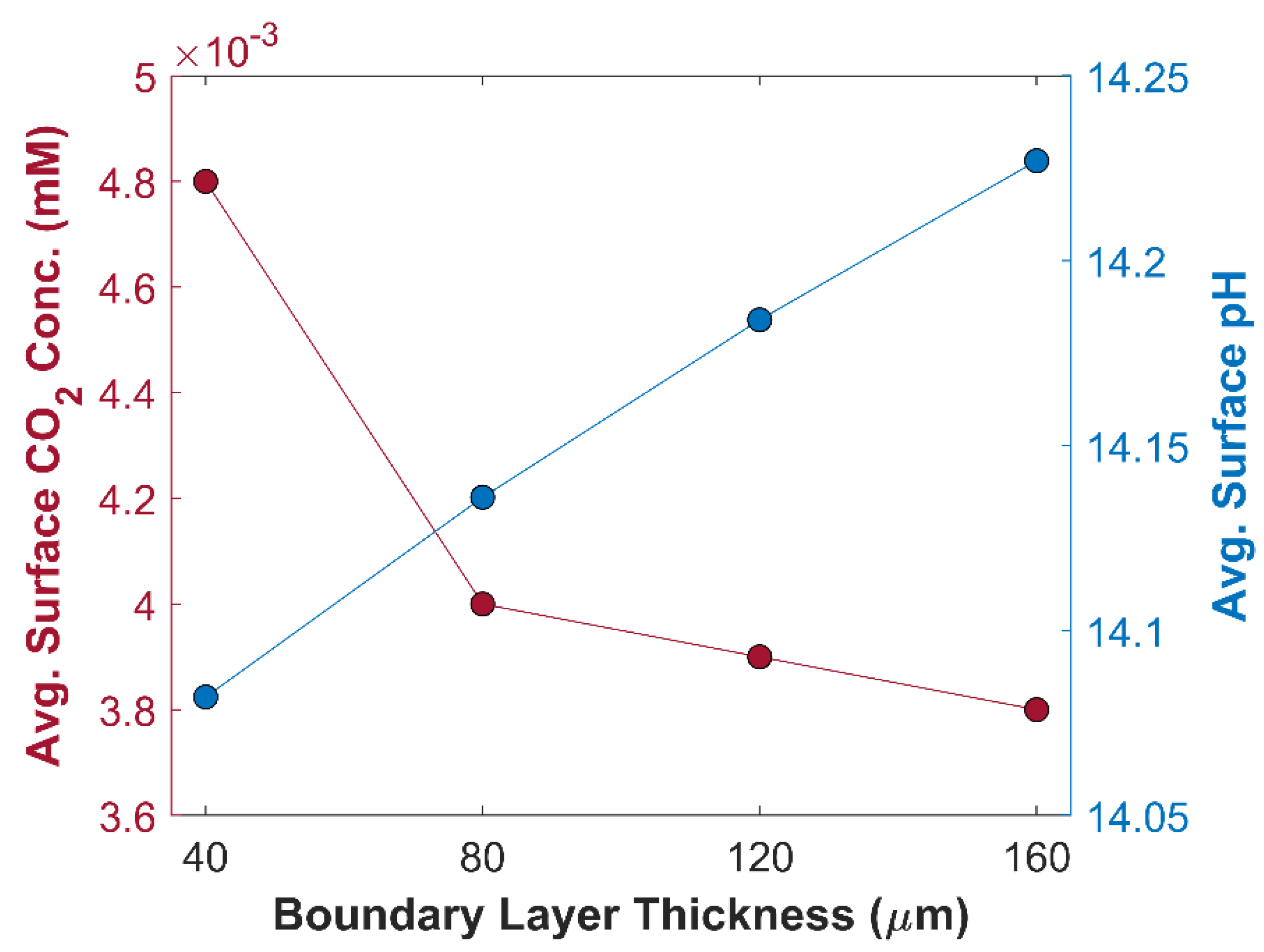

2RR. The effect of boundary layer thickness on TCD at a certain applied cathodic voltage (-1.0 V vs RHE) is shown in the

Figure 7. TCD is obtained for 4 different boundary layer thicknesses of equal interval: 40

m, 80

m, 120

m, 160

m.

Figure 7 shows an inverse relationship between TCD, and boundary layer thickness, and the trend is not linear. TCD at BL thickness of 160

m is 85.15 mA cm

-2, while it becomes 117.34 mA cm

-2 by reducing BL thickness from 160

m to 40

m. A significant increase in TCD of 24.10 mA cm

-2 is observed, when BL thickness is reduced from 80

m to 40

m, however, the overall jump in the TCD is merely 8.12 mA cm

-2 when BL thickness is decreased from 160

m to 80

m. The total increase in TCD is 3.11 mA cm

-2, and 5.01 mA cm

-2 in an interval of 160

m to 120

m, and 120

m to 80

m, respectively. A substantial improvement in the TCD at BL thickness of 40

m is due to the lower resistance to CO

2 mass transfer, and decline in chemical conversion of CO

2 into bi-carbonates and carbonates. Average surface concentration of CO

2 in CL is shown in the

Figure 8. CO

2 concertation available for eCO

2RR is much higher at 40

m thick boundary layer, compared with CO

2 concertation at other BL thickness, which is consistent with TCD results for thinner BLs. It is also consistent with gas flow electrolyzer using GDL, where BL thickness on the CL pore walls is only a few micrometers thick, eliminating the resistance to CO

2 mass transfer in aqueous phase [

24]. BL thickness has a substantial impact on the movement of other species, such as negatively charged hydroxyl ions (OH

-1), which are the by-products of eCO

2RR. In highly alkaline media, OH

-1 ions govern pH in the vicinity of WE, and hence the selectively of eCO

2RR products [

52]. In this study, 1 M KOH is used as an electrolyte that has a pH value of 14, but this pH value prone to change, as eCO

2RR progresses. Besides diffusion mechanism, electromigration also comes into play for the transfer of OH

-1 ions. Thinner BL expedite the transfer of OH

-1ions from the surface of CL to the bulk of an electrolyte. It is evident from

Figure 8, where pH of 14.23 at BL thickness of 160

m drops to 14.08 at BL thickness of 40

m.

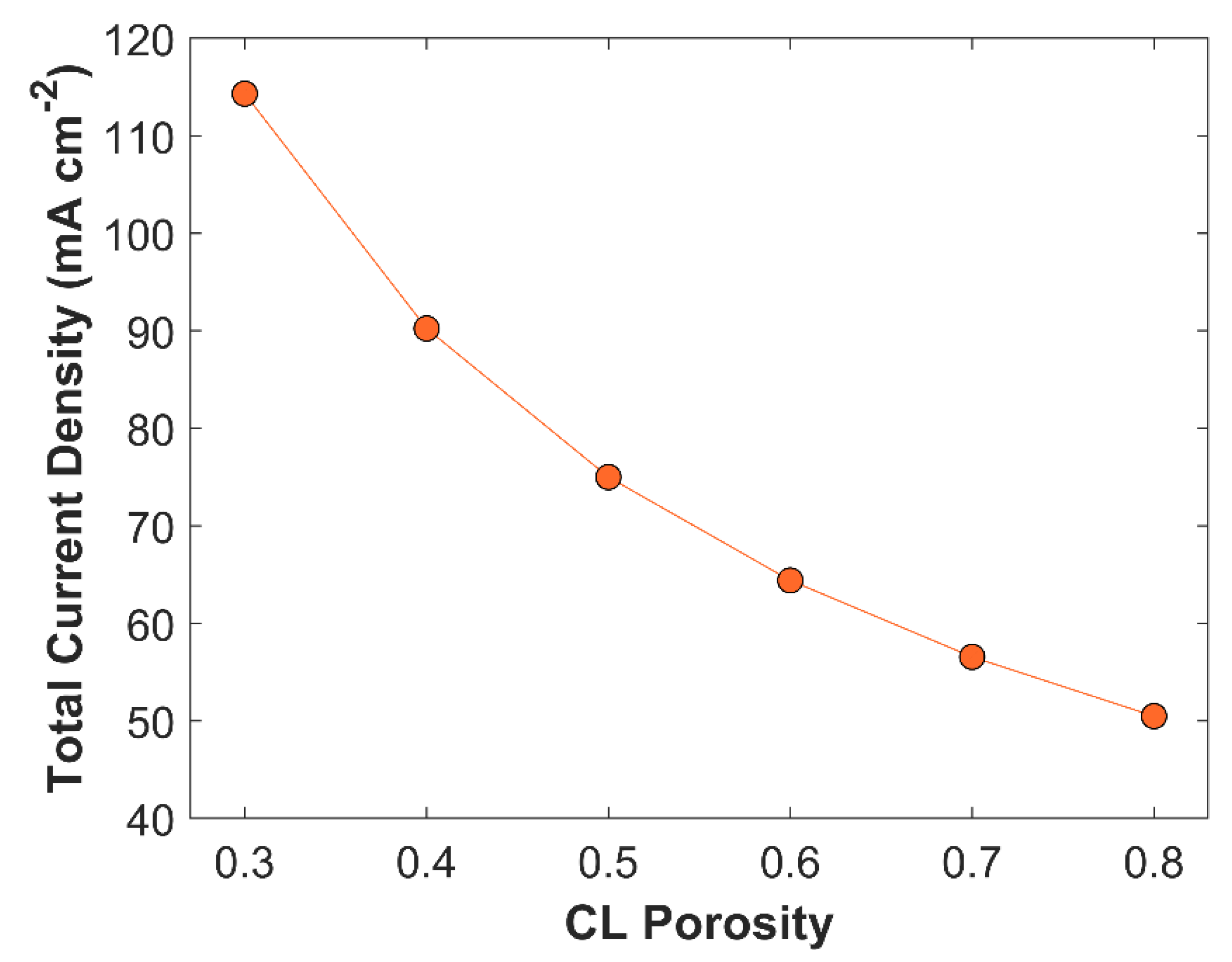

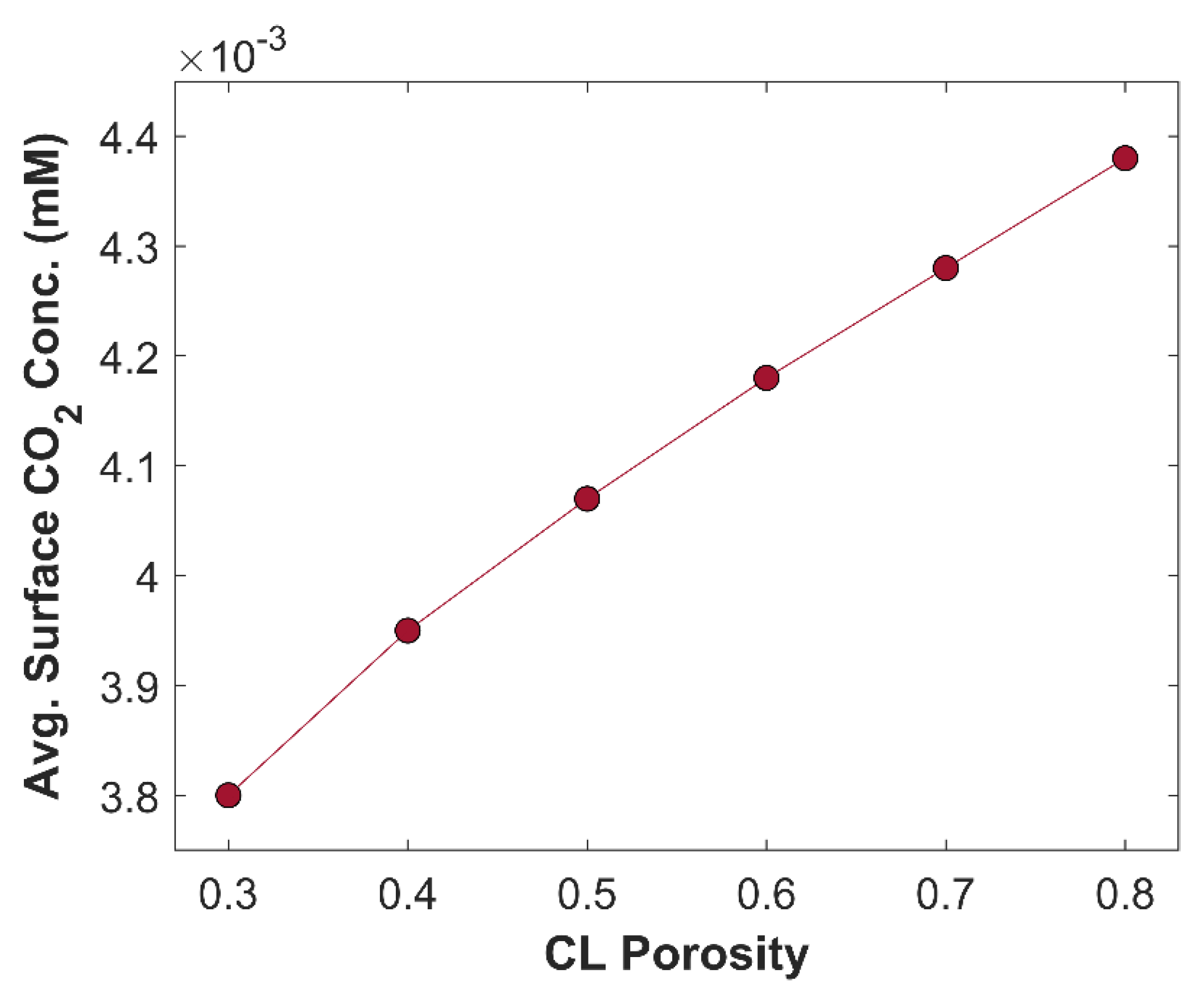

CL has a porous structure. Its porosity is defined as [

24];

is the catalyst mass per unit area,

is the catalyst mass density, and

is the thickness of catalyst layer. Porous CL offers more active surface for eCO

2RR, than a traditional single metal solid electrode [

24]. Although, porous CL has more active surface area, but it also minimizes catalyst loading (if the CL length is kept constant, see equation 24), which affects the TCD. CL porosity also effects the diffusion of CO

2, and eCO

2RR products. Porous CL accelerates species diffusion rate; allows more CO

2 to penetrate inside CL, and the removal of product species from CL to the bulk of an electrolyte. Moreover, eCO

2RR includes gaseous products, which forms bubbles inside the CL, and decreases the active surface area for eCO

2RR [

53]. In this study, bubble dynamics is not included in the model. CL has pore sizes in the range 10 – 100 nm [

27]. The effect of CL porosity on TCD is plotted in

Figure 9. CL porosity is varied from 0.3 to 0.8. TCD rises gradually from 50.48 mA cm

-2 to 114.32 mA cm

-2, when CL porosity is reduced from 0.8 to 0.3. The increase in TCD with reduced CL porosity is due to increase in catalyst mass loading that substantially increases active sites for CO

2 reduction. However, lower CL porosity affects CO

2 diffusion rate, and the average concentration of CO

2 in CL decreases slightly, see

Figure 10.

Figure 10 clearly shows that CO

2 concentration is much higher in porous CL (CL porosity 0.8), but TCD is lower due to reduce active sites.

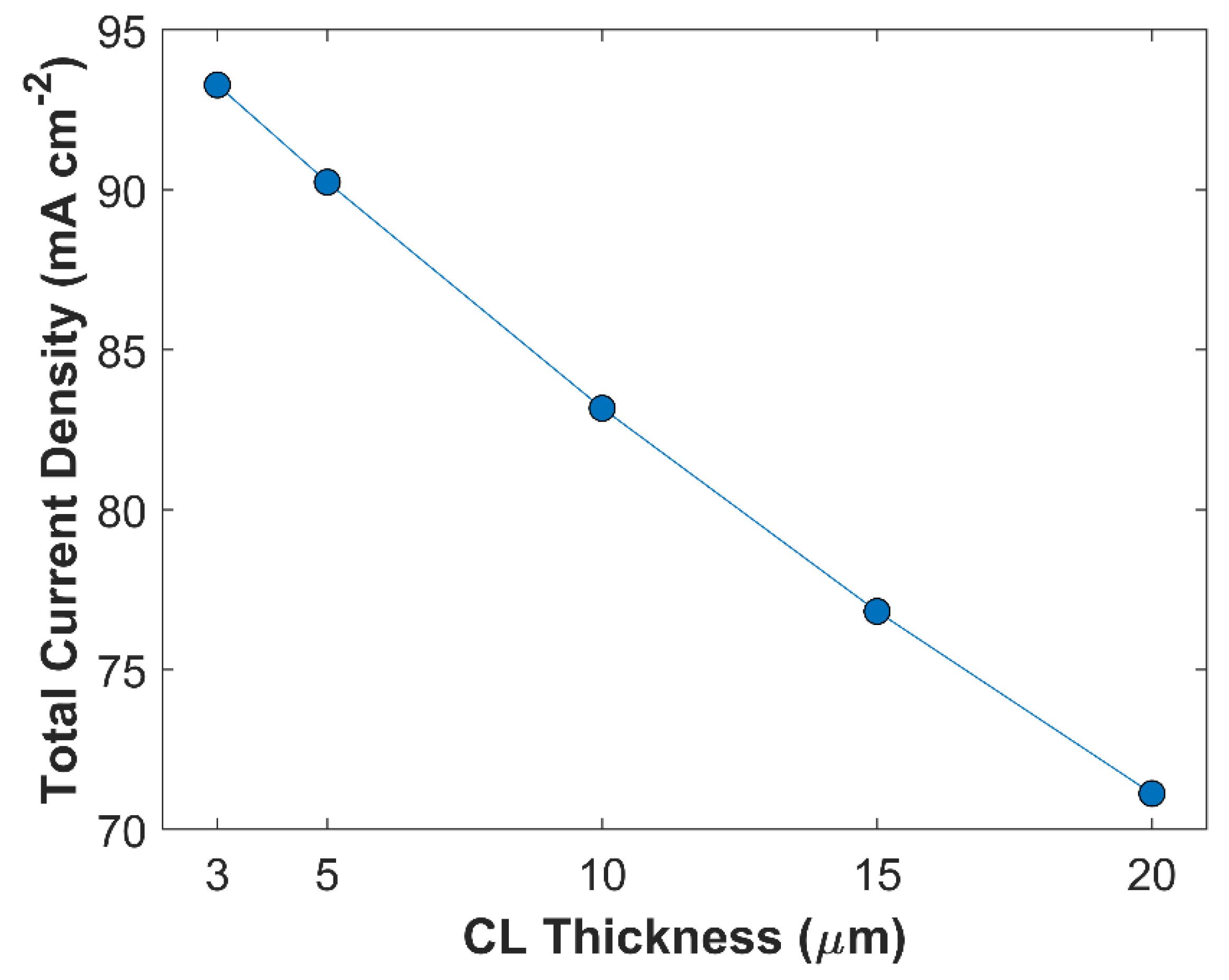

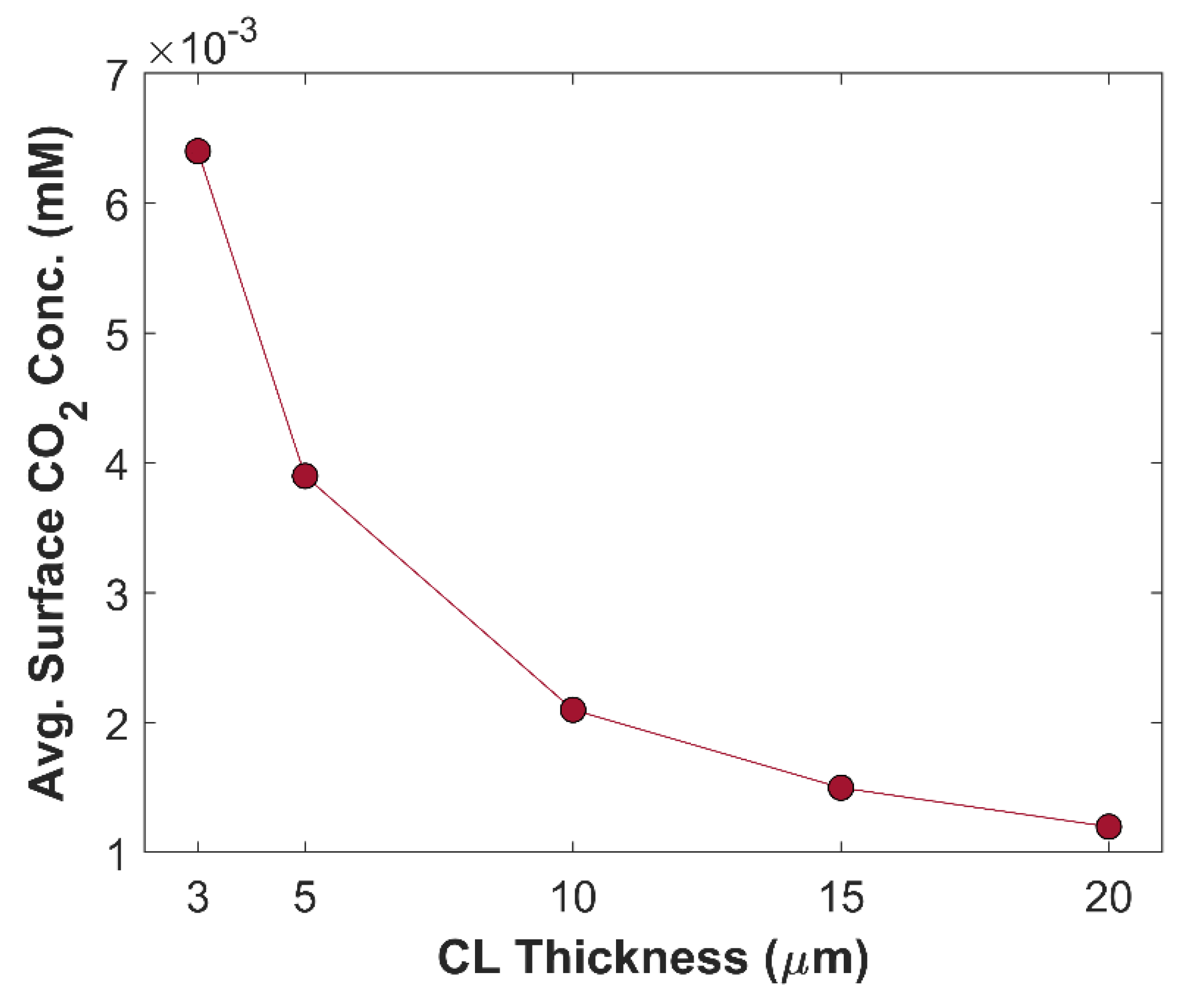

CL thickness, and CL porosity have a direct link with each other, see equation 24. Desired CL thickness with required CL porosity may be obtained by adjusting the catalyst loading. CL thickness plays a vital role in electrochemical kinetics. Although thicker CL seems to have increased catalyst loading, which could have a substantial impact on TCD; ironically, most part of the CL is rendered inoperable due to limited supply of CO

2, and fast CO

2 reduction kinetics. Moreover, thicker CL has longer tortuous diffusion path, reducing species diffusion rate inside CL. In this study, 5 different CL thickness have been simulated at a fixed cathodic voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 11 shows the effect of CL thickness on TCD. Overall, TCD increases by reducing CL thickness. TCD with 20

m thick CL is 71.13 mA cm

-2, and TCD with 3

m thick CL is 93.28 mA cm

-2, approximately. A total increase of 24 mA cm

-2 is observed just by varying the CL thickness, keeping all other parameters constant. This increase in TCD is attributed to improvement in species diffusion rate. Average surface CO

2 concentration at different CL thickness is shown in

Figure 12. Average surface CO

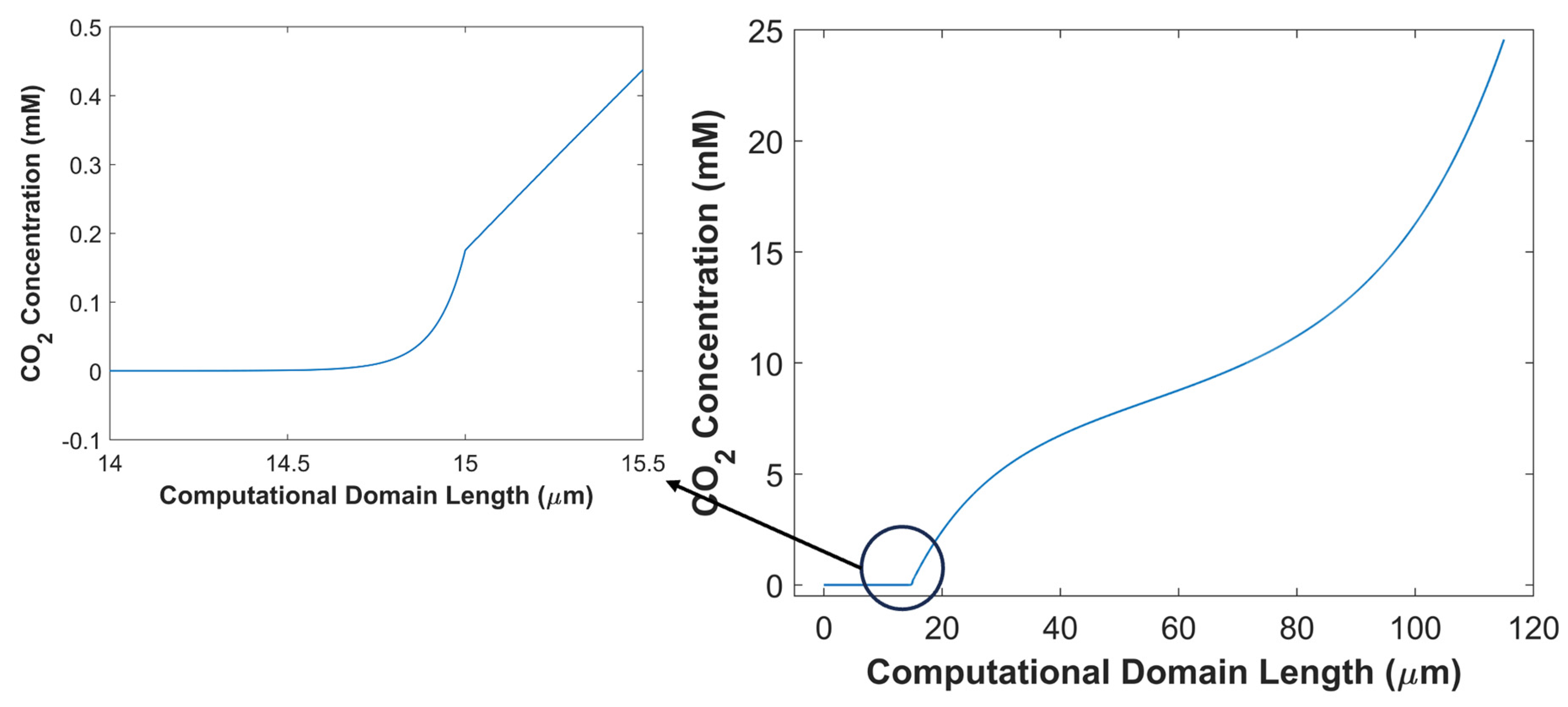

2 concentration increases with decreasing CL thickness, due to shorter diffusion path inside CL. Local distribution of CO

2 in CD (boundary layer + catalyst layer) shows that CO

2 concertation decreases gradually from the outer periphery of BL to the interface of BL and CL, but a sharp decline in CO

2 concertation profile is seen when CO

2 enters into the CL domain. In BL, CO

2 undergoes reversible chemical reaction, but in CL, besides chemical conversion, CO

2 is also consumed electrochemically. Furthermore, lower porosity, and tortuous path inside CL impede CO

2 diffusion rate. Also, local CO

2 concentration profile in CL shows that most of CO

2 gets consumed/converted before even reaching the middle of the CL, and does not reach the other end of CL, see

Figure 13.

Nature of an electrolyte has a significant impact on CO

2 reduction kinetics. KOH, by far, is one of the famous electrolytes for CO

2 reduction, due to its good ionic conductivity and alkaline nature (suppresses HER), and it has been used in numerous studies for performing CO

2 reduction in an alkaline environment [

12,

14,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Potassium bicarbonate (KHCO

3), a buffer solution, is known for providing near neutral pH conditions for CO

2 reduction [

24,

25]. In order to study the effect of nature of an electrolyte on CO

2 reduction kinetics, 1 M KHCO

3 electrolyte is simulated, and compared with 1 M KOH simulation results. Two additional reversible chemical reactions have been included in the model for 1 M KHCO

3 electrolyte, see

Table 7. Kinetic rate parameters for these reactions are reported in

Table 6.

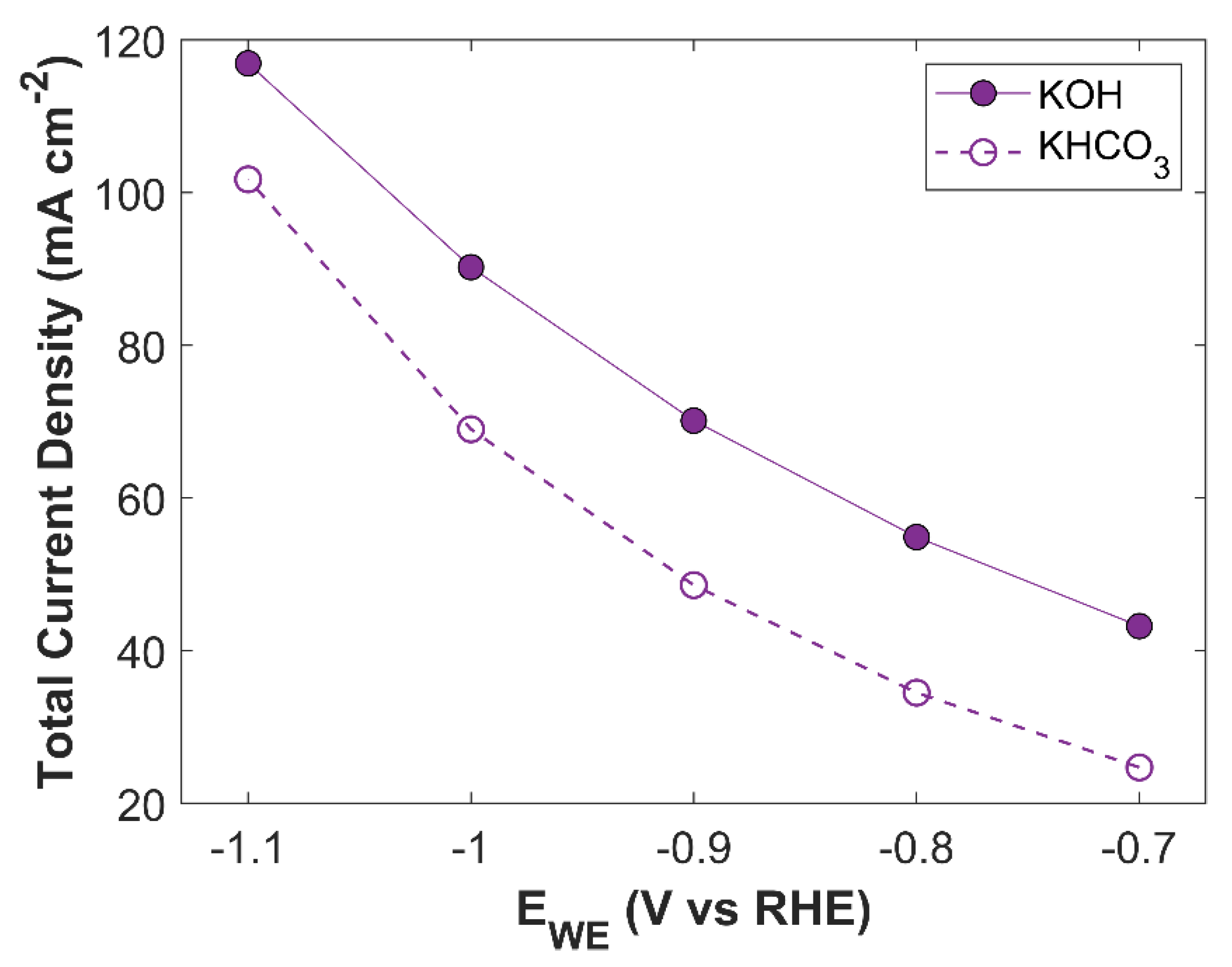

Simulation results with both 1 M KHCO

3, and 1 M KOH are shown in

Figure 14. There is a significant difference between the TCD obtained using KHCO

3 electrolyte and KOH electrolyte. The maximum TCD with KHCO

3 is 101.75 mA cm

-2 at an applied cathodic potential of -1.1 V vs RHE, while TCD with KOH at -1.1 V vs RHE is 116.94 mA cm

-2. This difference is due to the intrinsic nature of the electrolytic solutions. KHCO

3 is a buffer solution, therefore, to maintain the buffer it consumes more CO

2. Batch-cell that is already limited with CO

2 supply, suffers from CO

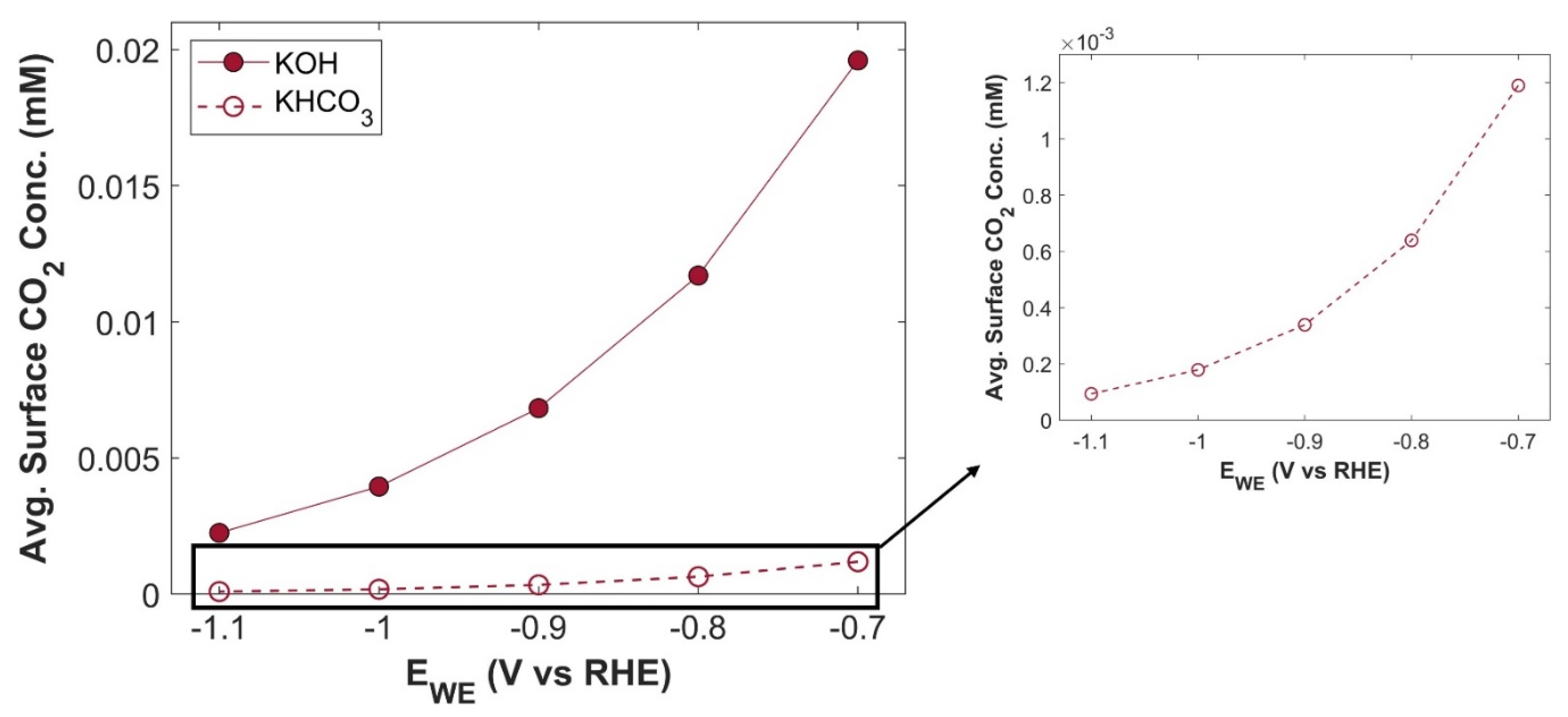

2 drought at CL domain, resulting in much lower TCD. A comparison of average surface CO

2 concentration for both electrolytes is shown in the

Figure 15. Although, CO

2 concentration in both cases follows the same trend with increasing applied voltage, but there is an order of magnitude difference in CO

2 concentration. PCD of CO

2 reduction products using 1 M KHCO

3 electrolyte are shown in

Figure 16. It shows that electrolyte could alter the selectivity of eCO

2RR products.

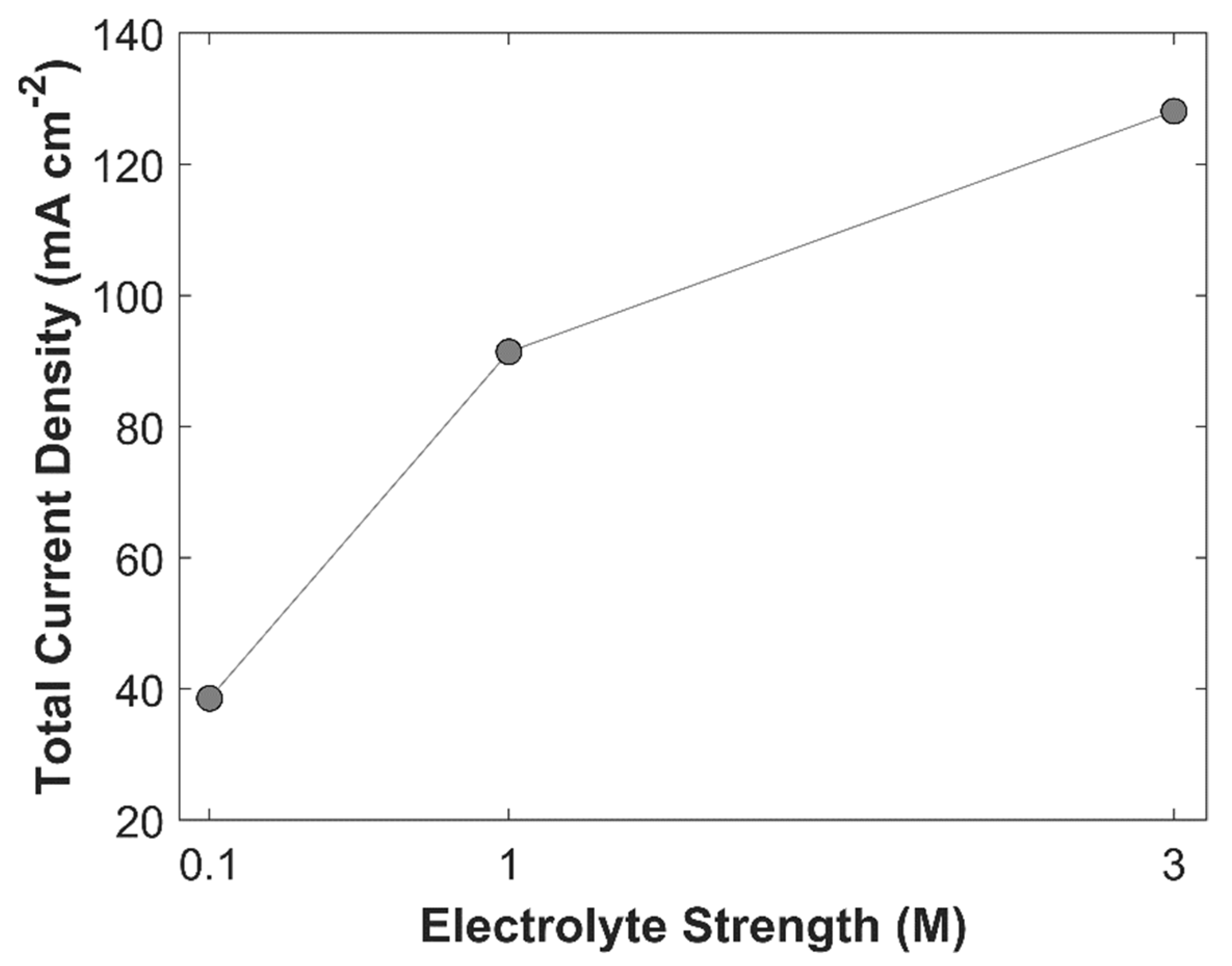

The primary purpose of an electrolyte is to enhance conductivity of an aqueous phase. An electrolyte with higher molarity provides a more conductive medium by minimizing charge transfer resistance between the electrodes [

43] and by reducing the negative overpotential of CO

2 reduction products [

10]. Effect of an electrolyte strength on TCD at an applied cathodic potential of -1.0 V vs RHE is shown in

Figure 17. KOH electrolyte with three different molarities of 0.1 M, 1 M, and 3 M have been simulated. TCD increases with increasing molarity of an electrolyte. TCD with 0.1 M, 1 M, and 3 M KOH is 38.56 mA cm

-2, 91.41 mA cm

-2, and 128.11 mA cm

-2, respectively. It shows that improved conductivity of medium increases the movement of charged species, which as a result boost electrochemical kinetics. However, it can be seen from the

Figure 17 that the slope of line between 0.1 M, and 1 M KOH solution is greater, than the slope of line between 1 M, and 3 M KOH solution. The decline in the slope is due to limited amount of CO

2 available for eCO

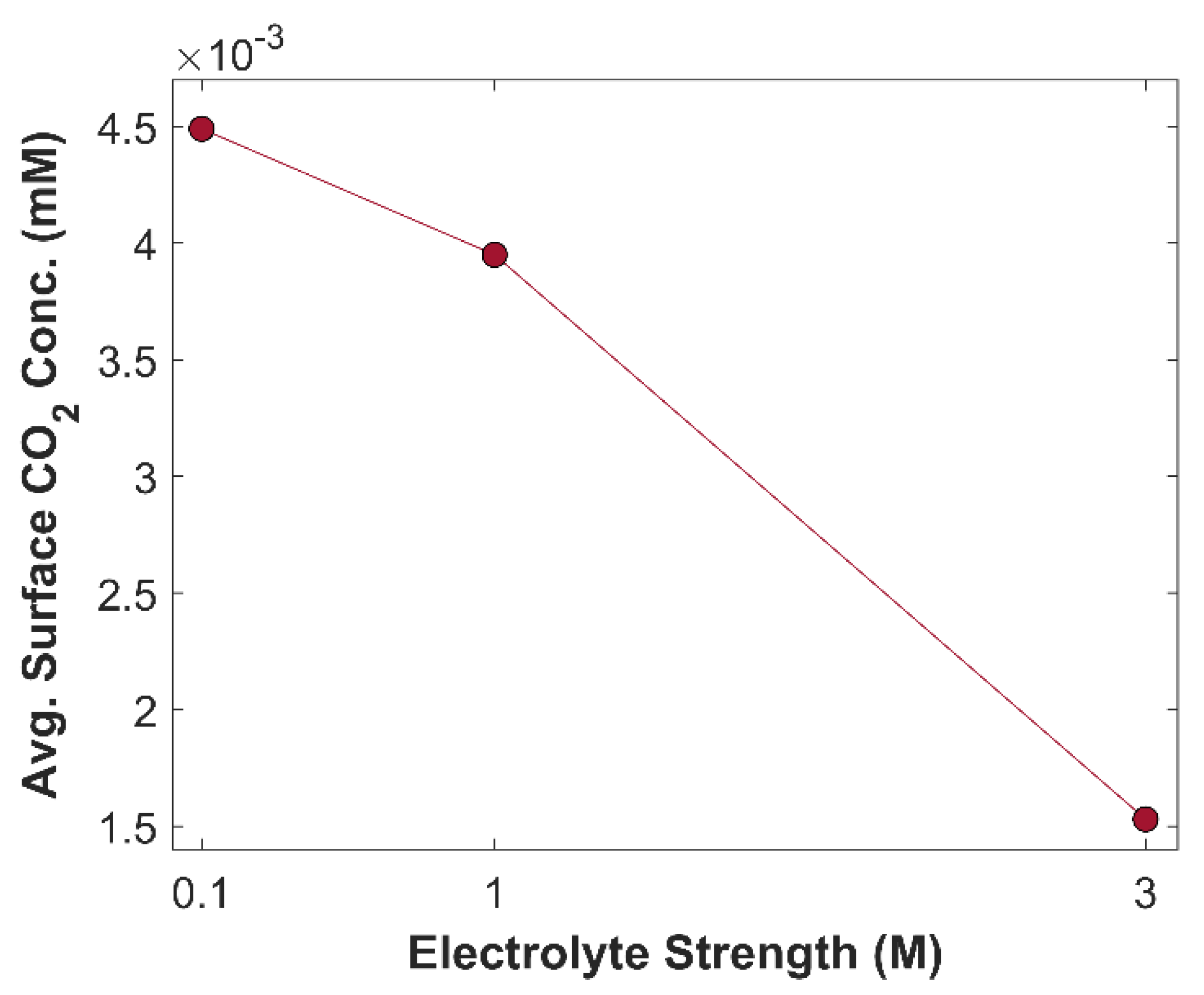

2RR. On one side, KOH with higher molarity achieves higher TCD, but, on the other hand, higher OH

-1 ions concentration consumes more CO

2 and hence the carbon efficiency decreases. Average surface concentration of CO

2 with different molarities of KOH is shown in

Figure 18. Furthermore, average bulk pH of 0.1 M, 1 M, and 3 M KOH are 13, 14, and 14.5, respectively. KOH with different molarity alters the selectivity of eCO

2RR products, due to difference in pH value.

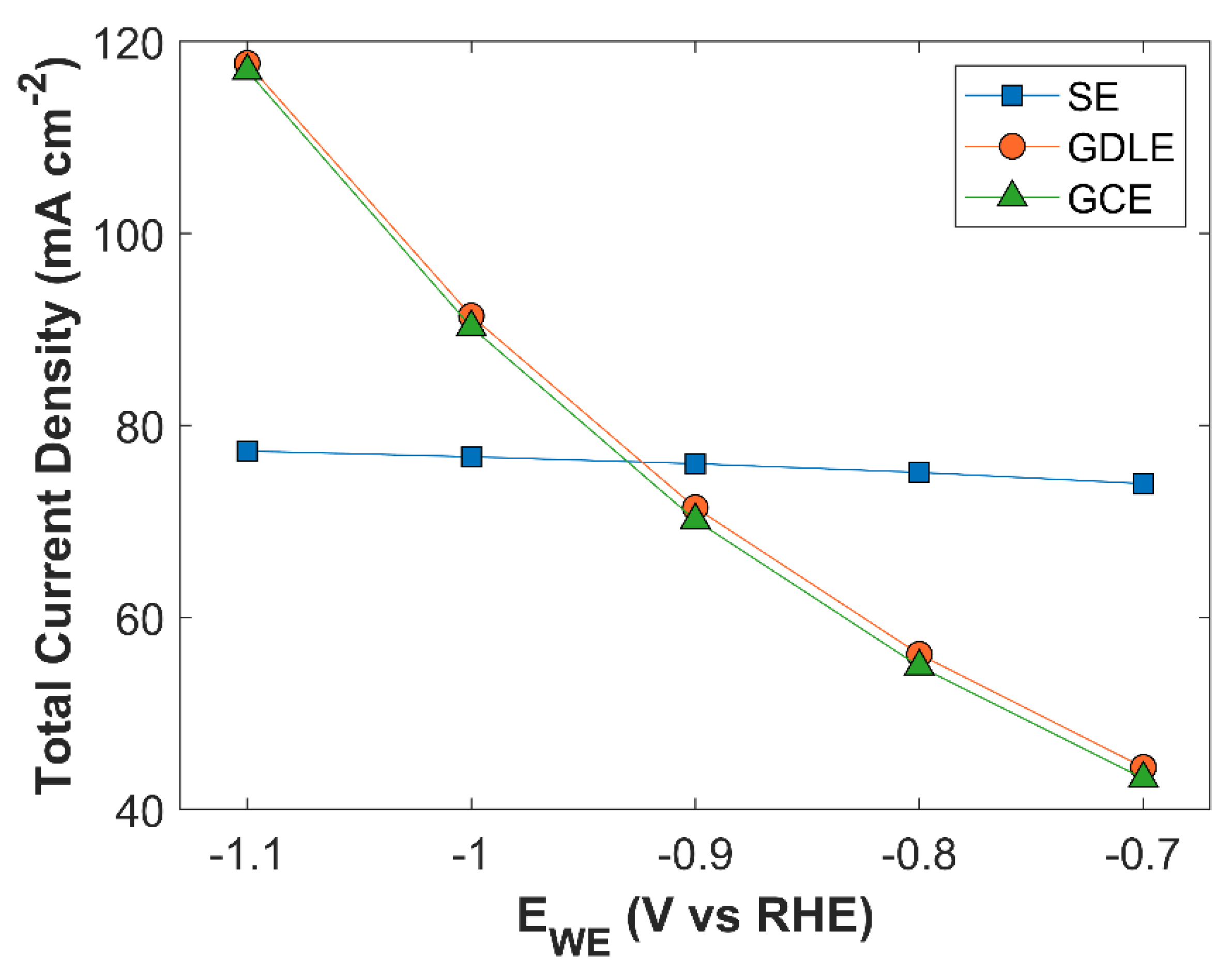

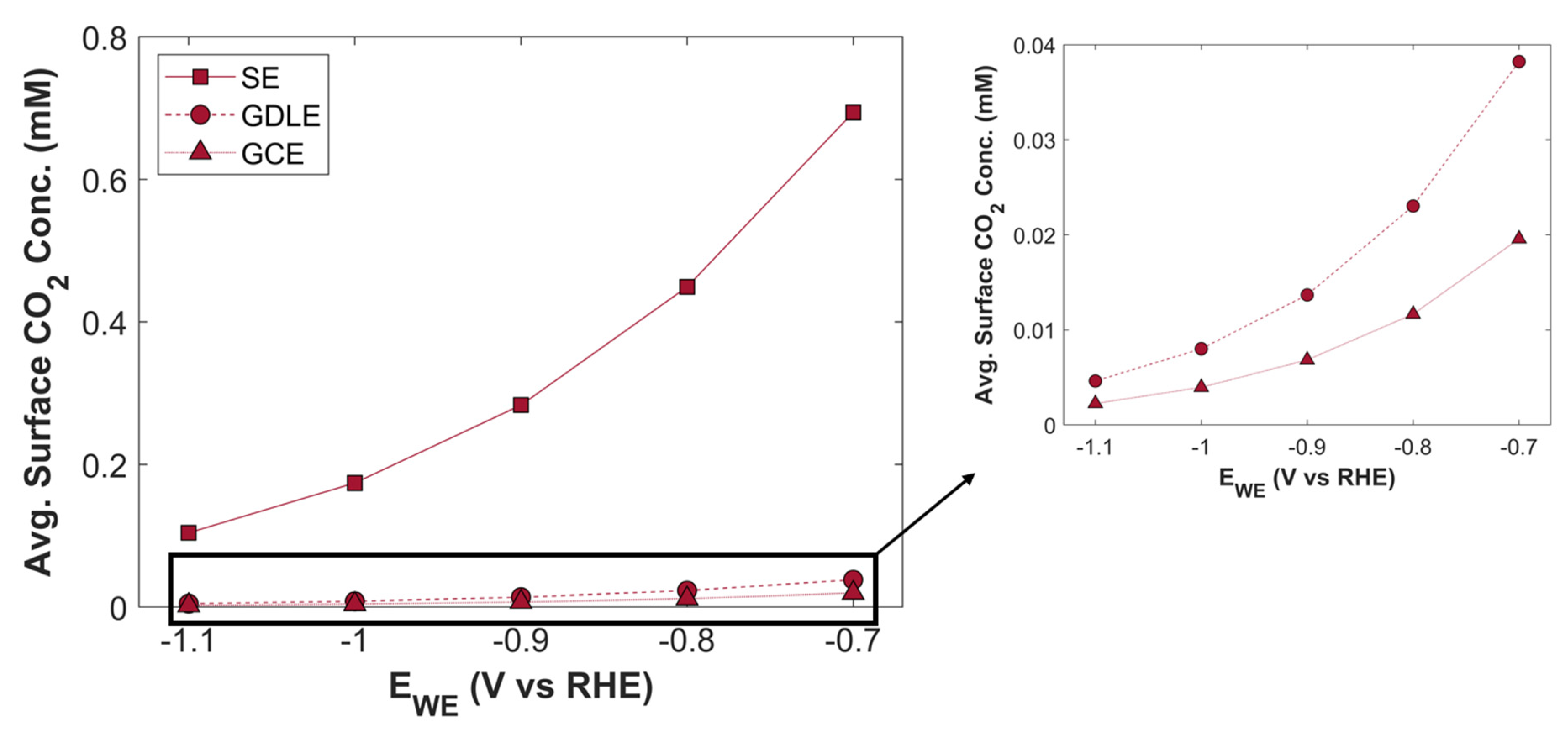

TCD comparison of SE, GDLE, and GCE is shown in

Figure 19. There is a stark difference between TCD of SE, and the electrodes with porous structure (GDLE, GCE). TCD of SE increases with the increase in applied cathodic voltage, however, overall TCD increase is not significant, in comparison with the porous electrodes. At -0.7 V vs RHE, TCD of SE is 73.94 mA cm

-2, and it rises to 77.34 mA cm

-2, at -1.1 V vs RHE. There is barely an increase of 3.39 mA cm

-2 in TCD. Furthermore, the slope of solid electrode TCD curve decreases with the increase in applied voltage. Besides limited amount of CO

2 in the reaction medium for SE, the availability of active surface area for CO

2 to adsorb on the catalyst surface for eCO

2RR are some factors that strongly limits TCD. Average surface CO

2 concentration for SE is relatively much higher compared with GDLE, and GCE, but due to the limited active surface area, the probability of eCO

2RR is reduced, see

Figure 20. TCD of GDLE traces the GCE curve, with a marginal difference. TCD of GDLE, and GCE at an applied cathodic voltage is -0.7 V vs RHE is 44.37 mA cm

-2, and 43.21 mA cm

-2, respectively. TCD for both GDLE, and GCE increases with an increase in applied cathodic voltage, and TCD for both electrodes at -1.1 V vs RHE is 117.72 mA cm

-2, and 116.94 mA cm

-2, respectively. GDLE and GCE have a porous CL, which offers huge number of active sites for eCO

2RR, therefore, TCD increases substantially with increasing applied voltage. GDLE has a higher TCD, as it facilitates more CO

2 to diffuse into CL. Therefore, average surface CO

2 concentration is higher for GDLE, than GCE. Moreover, average surface CO

2 concentration curves for all the 3 electrodes show the same behavior with increasing applied voltage, and all the three curves seem to converge to zero CO

2 concentration point.

Figure 1.

Computational domain of GCE with necessary boundary conditions.

Figure 1.

Computational domain of GCE with necessary boundary conditions.

Figure 2.

Computational domain of solid electrode with necessary boundary conditions.

Figure 2.

Computational domain of solid electrode with necessary boundary conditions.

Figure 3.

GDLE computational domain with boundary conditions.

Figure 3.

GDLE computational domain with boundary conditions.

Figure 4.

Grid independent solution.

Figure 4.

Grid independent solution.

Figure 5.

Batch-cell model validation: simulated TCD vs experimental TCD for CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst as a function of applied cathodic potential.

Figure 5.

Batch-cell model validation: simulated TCD vs experimental TCD for CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst as a function of applied cathodic potential.

Figure 6.

Numerical model validation with metallic Cu catalyst.

Figure 6.

Numerical model validation with metallic Cu catalyst.

Figure 7.

Boundary layer thickness effect on total current density at a fixed applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 7.

Boundary layer thickness effect on total current density at a fixed applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 8.

Average surface CO2 concentration and pH in CL as a function of BL thickness at an applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 8.

Average surface CO2 concentration and pH in CL as a function of BL thickness at an applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 9.

Effect of CL porosity on TCD. Applied cathodic voltage is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 9.

Effect of CL porosity on TCD. Applied cathodic voltage is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 10.

Variation of average surface CO2 concentration in CL with CL porosity. Applied cathodic potential -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 10.

Variation of average surface CO2 concentration in CL with CL porosity. Applied cathodic potential -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 11.

Variation of TCD with CL thickness. Applied cathodic potential is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 11.

Variation of TCD with CL thickness. Applied cathodic potential is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 12.

Average surface CO2 concentration versus CL thickness. Applied cathodic potential is -1 V vs RHE.

Figure 12.

Average surface CO2 concentration versus CL thickness. Applied cathodic potential is -1 V vs RHE.

Figure 13.

Local CO2 concentration profile in computational domain (BL+CL).

Figure 13.

Local CO2 concentration profile in computational domain (BL+CL).

Figure 14.

Effect of 1 M KOH and 1 M KHCO3 electrolyte on TCD.

Figure 14.

Effect of 1 M KOH and 1 M KHCO3 electrolyte on TCD.

Figure 15.

Average surface CO2 concentration when using 1 M KOH and 1 M KHCO3 as an electrolyte.

Figure 15.

Average surface CO2 concentration when using 1 M KOH and 1 M KHCO3 as an electrolyte.

Figure 16.

Partial current density of CO2 reduction products using KHCO3 electrolyte.

Figure 16.

Partial current density of CO2 reduction products using KHCO3 electrolyte.

Figure 17.

Effect of electrolyte strength on TCD. Applied cathodic potential is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 17.

Effect of electrolyte strength on TCD. Applied cathodic potential is -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 18.

Average surface concentration of CO2 as a function of electrolyte strength at a fixed applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 18.

Average surface concentration of CO2 as a function of electrolyte strength at a fixed applied voltage of -1.0 V vs RHE.

Figure 19.

TCD comparison of 3 different electrode configurations: solid electrode (SE), gas diffusion layer electrode (GDLE), and glassy carbon electrode (GCE).

Figure 19.

TCD comparison of 3 different electrode configurations: solid electrode (SE), gas diffusion layer electrode (GDLE), and glassy carbon electrode (GCE).

Figure 20.

Average surface CO2 concentration as a function of applied cathodic voltage for three different electrode configurations.

Figure 20.

Average surface CO2 concentration as a function of applied cathodic voltage for three different electrode configurations.

Table 1.

Electrochemical CO2 reduction reactions for CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst.

Table 1.

Electrochemical CO2 reduction reactions for CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst.

| Species |

Reactions |

| H2: |

|

| CO: |

|

| CH4: |

|

| C2H4: |

|

| EtOH: |

|

| PrOH: |

|

Table 2.

Chemical reaction of CO2 with electrolyte in alkaline media.

Table 2.

Chemical reaction of CO2 with electrolyte in alkaline media.

| R1: |

|

K1 (1/M) |

| R2: |

|

K2 (1/M) |

| Rw: |

|

Kw (M2) |

Table 3.

Sechenov's constants.

Table 3.

Sechenov's constants.

| Constants |

Values |

|

-0.0172 |

|

-0.000338 |

|

0.0922 |

|

0.0839 |

|

0.0967 |

|

0.1423 |

Table 4.

and values.

Table 4.

and values.

| |

|

|

| H2

|

0 |

0.5 |

| CO |

1.5 |

1.56 |

| CH4

|

0.84 |

1.56 |

| C2H4

|

1.36 |

0 |

| EtOH |

0.96 |

0 |

| PrOH |

0.96 |

0 |

Table 5.

Pre-simulation estimates for local CO2 concentration, and pH values using experimental data of CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst.

Table 5.

Pre-simulation estimates for local CO2 concentration, and pH values using experimental data of CuAg0.5Ce0.2 catalyst.

| TCD |

CO2 |

pH |

| (mA cm-2) |

(mM) |

|

| -47 |

15.747 |

11.072 |

| -64 |

12.150 |

11.128 |

| -84 |

8.0113 |

11.219 |

| -105 |

6.1246 |

11.28 |

| -131 |

4.2034 |

11.368 |

Table 7.

Additional reversible chemical reactions.

Table 7.

Additional reversible chemical reactions.

| R3: |

|

K3 (M) |

| R4: |

|

K4 (M) |