1. Introduction

Spodoptera frugiperda, commonly known as the fall armyworm, is a highly migratory agricultural pest of major significance, globally recognized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a severe threat. It is characterized by a broad host range, strong migratory ability, rapid spread, high reproductive rate, and significant resistance to pesticides, posing substantial risks to agricultural production in many countries [

1]. Currently, chemical pesticides are the primary method for controlling

S. frugiperda. However, excessive use of chemical pesticides has led to increased pest resistance and resurgence, disrupted the natural balance of ecosystems, and caused severe environmental pollution [

2]. Biological control, especially the use of microbial biopesticides, has emerged as a promising sustainable strategy for managing

S. frugiperda [

3,

4]. Among the insecticides recommended by China's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs for emergency control of

S. frugiperda, six are biopesticides. These include five pathogenic microorganism-based products and one viral product:

Mamestra brassicae nucleopolyhedrovirus,

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt),

Metarhizium anisopliae,

Beauveria bassiana (Bb), and

Empedobacter brevis. Among these,

B. thuringiensis is the most widely used and successful microbial insecticide, known for its high specificity, safety, and lack of residues [

5].

Microorganisms can cause the death of

S. frugiperda, but the pest simultaneously activates immune responses to resist and eliminate the invading pathogens [

6,

7]. Through long-term co-evolution, insects have developed a highly efficient and comprehensive innate immune system to defend against microbial and parasitic infections. Bai Yaoyu and colleagues discovered that injecting

Escherichia coli (Ec) affects the cellular immune functions of

S. frugiperda [

8], while the invasion of

Steinernema carpocapsae, a nematode species, leads to a "decrease-increase-decrease" trend in the hemolymph phenoloxidase activity of

S. frugiperda larvae [

9]. Pathogenic microbial invasion triggers a series of humoral and cellular immune responses in the host, stimulating the production of melanin and various antimicrobial peptides. The robust immune system of the host is one of the most critical factors limiting the "high virulence" of pathogens. Currently, research on the immune functions of

S. frugiperda remains in its early stages. Therefore, an in-depth investigation into the composition and molecular regulatory mechanisms of the immune system of

S. frugiperda is crucial for improving the efficacy of pathogenic microorganisms and developing novel, specific-target, and highly efficient biopesticides.

This study focuses on transcriptome sequencing of S. frugiperda infected by different pathogenic microorganisms, identifying immune-related genes through differential expression analysis, and conducting bioinformatic analyses and expression validation of these genes. The aim is to uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between pathogenic microorganisms and S. frugiperda, thereby providing new methods and theoretical foundations for utilizing pathogens in the biological control of S. frugiperda.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Insects

The S. frugiperda used in this experiment was collected from Fengyang County, Chuzhou City, Anhui Province (117.56°E, 32.86°N) and propagated for multiple generations indoors to establish an experimental population. The larvae of S. frugiperda were reared with artificial feed in an insectary at 27 ± 1°C, relative humidity of 80% ± 10%, and a photoperiod of 14L:10D.

The bacteria used in this experiment were Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and B. thuringiensis (Bt), Gram-negative bacteria E. coli (Ec), and fungus B. bassiana (Bb). The bacterial strains were purchased from the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The bacteria were activated and cultured at 37°C and 200 rpm until the OD600 reached approximately 1. The cultures were centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The bacteria were washed three times with sterile PBS (7.7 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 2.65 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 6.4), adjusted to a concentration of 1×10^6 cells/mL, sterilized at 121°C under high pressure for 20 minutes, and stored for future use. B. bassiana was provided by Professor Hu Fei from the Institute of Plant Protection and Agro-Product Safety, Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences. It was cultured on PDA medium at 27°C, collected in enzyme-free EP tubes, shaken thoroughly with sterile water (containing 0.05% Tween-80), filtered with sterile cotton, counted using a hemocytometer, and diluted to 1×10^6 cells/mL for future use.

2.2. Injection Experiment

Healthy fourth-instar

S. frugiperda larvae of consistent size were selected and divided into a control group, PBS injection group,

S. aureus injection group,

E. coli injection group,

B. thuringiensis injection group, and

B. bassiana injection group, with 15 larvae per group and three replicates for each treatment. The injection experiment was performed according to the method of Sun & Bai (2020) [

10]. The larvae were anesthetized on ice for 5 minutes, and 5 µL of inactivated bacterial suspension (approximately 3.0×10^6 cells/mL) was injected into the proleg using a microsyringe, with an equal amount of PBS as the control. The injection site was surface sterilized with 70% alcohol, and the larvae were reared in an artificial climate chamber with artificial feed at 27 ± 1°C, relative humidity of 80% ± 10%, and a photoperiod of 14L:10D for 24 hours, then stored in liquid nitrogen for future use.

2.3. Total RNA Extraction and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the whole S. frugiperda using the Trizol method. The quality of the RNA was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and its concentration and purity were evaluated with a Nanodrop 2000 (OD260/280 and OD260/230 ratios). The integrity of RNA was accurately assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer to ensure sample quality. Qualified RNA samples were used for transcriptome sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 2000 platform.

2.4. Gene Expression Quantification and Differential Analysis

The raw sequencing data were processed by removing adapter sequences, low-quality reads, and reads with uncertain base information, resulting in high-quality clean reads. The reads were assembled using Trinity (Trinity-v2.5.1) software. The assembly quality of Trinity.fasta, unigene.fasta, and cluster.fasta was assessed using BUSCO software, and the accuracy and completeness of the assembly were evaluated based on the GC content and unigene sequence integrity. Gene expression levels were quantified by FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 from edgeR 3.8.6, with differentially expressed genes selected based on an FDR < 0.01 and fold change (FC) greater than 2. GO functional enrichment analysis was performed using TopGO, and KEGG pathway analysis was conducted using ClusterProfiler.

2.5. Identification and Analysis of Immune-Related Genes

The

S. frugiperda unigenes served as the original database, and immune sequences from other known insect model species were used as a reference database. Immune pathway-related gene sequences were screened from the

S. frugiperda transcriptome. CD-search (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) and SMART (

http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) were used to examine conserved domains in candidate genes of non-redundant protein families. Signal peptides and transmembrane domains of different protein families were verified using SignalP 4.1 (

http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP) and TMHMM (

http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). Heatmaps of the FPKM values of differentially expressed genes across treatments were generated using TBtools, and MEGA 11.0 was used to align homologous immune proteins of

S. frugiperda with those of other insects. A phylogenetic tree of

S. frugiperda immune family proteins and homologous proteins from other insects was constructed using the maximum likelihood method, and FigTree1.4.4 was used for visualization to clarify the evolutionary relationship of immune proteins between

S. frugiperda and other insects.

2.6. qPCR Verification of S. frugiperda Immune Receptor Genes

The gene sequences were obtained from NCBI, and primers were designed online (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). RPL3 and RPL18 [

11,

12] were used as reference genes. The primer sequences for candidate genes are shown in

Table 1. High-quality RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA using the TransScript One-step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit. The qPCR reaction (20 µL) consisted of 1 µL cDNA template, 1 µL of each forward and reverse primer, 1 µL ROX Reference Dye II, 10 µL TB Green Premix Ex Taq, and 6 µL ddH2O. The program was set according to RR420 A as follows: 95°C for 30 s, 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s, 40 cycles, followed by 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 s. Gene expression was calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method [

13], and data were analyzed using Prismchs (

Table 1).

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome Sequencing Data Statistics and Analysis

S. frugiperda larvae through transcriptome sequencing and analysis. Each sample had more than 6.72 Gb of Clean Data. The Q30 was above 95.72%, Q20 above 98.462%, the GC content ranged from 45.15% to 46.7%, and the error rate was 0.1% (

Table 2)

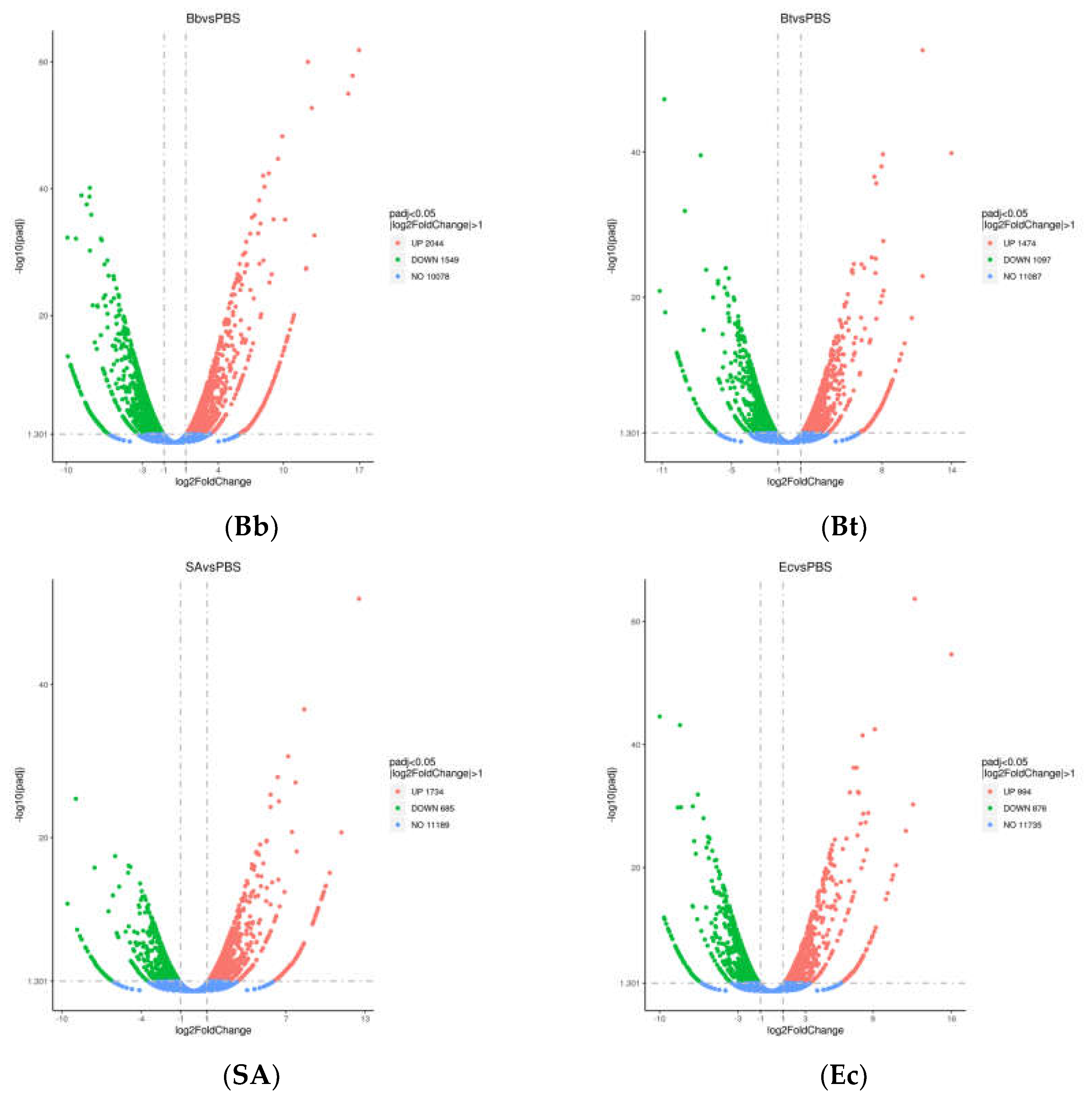

3.2. Differentially Expressed Gene Analysis

A total of 10,453 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified after treating S. frugiperda with pathogenic microorganisms. Comparative analysis of DEGs with the control group revealed that the Bb-treated group exhibited significantly more DEGs than other treatment groups, with a total of 3,593 DEGs. Among these, 2,044 genes were upregulated, and 1,549 genes were downregulated.

In the SA-treated group, 2,419 DEGs were identified, including 1,734 upregulated genes and 685 downregulated genes. The Bt-treated group showed 2,571 DEGs, with 1,474 genes upregulated and 1,097 genes downregulated. Lastly, the Ec-treated group had 1,870 DEGs, with 994 genes upregulated and 876 genes downregulated (

Figure 1).

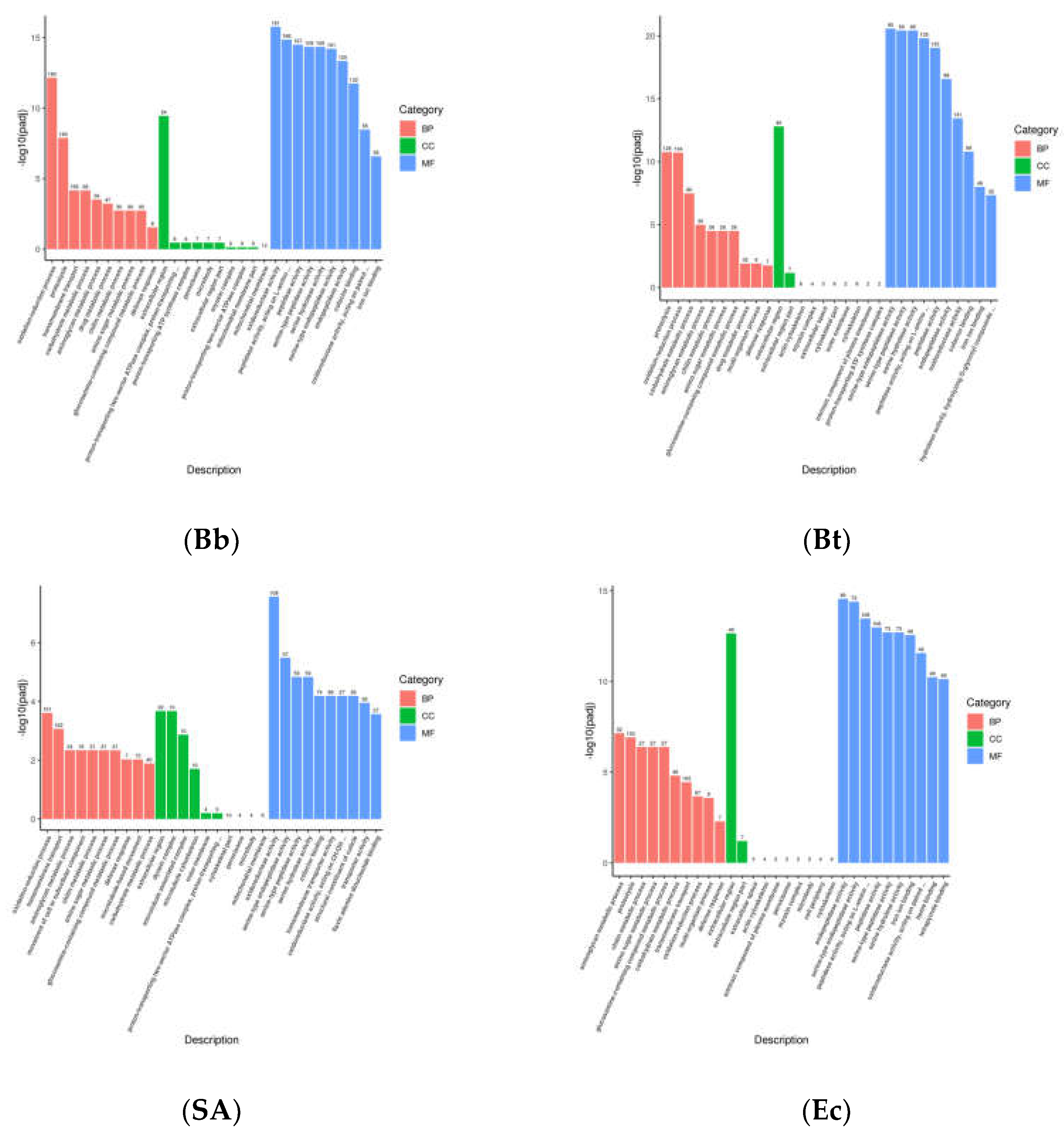

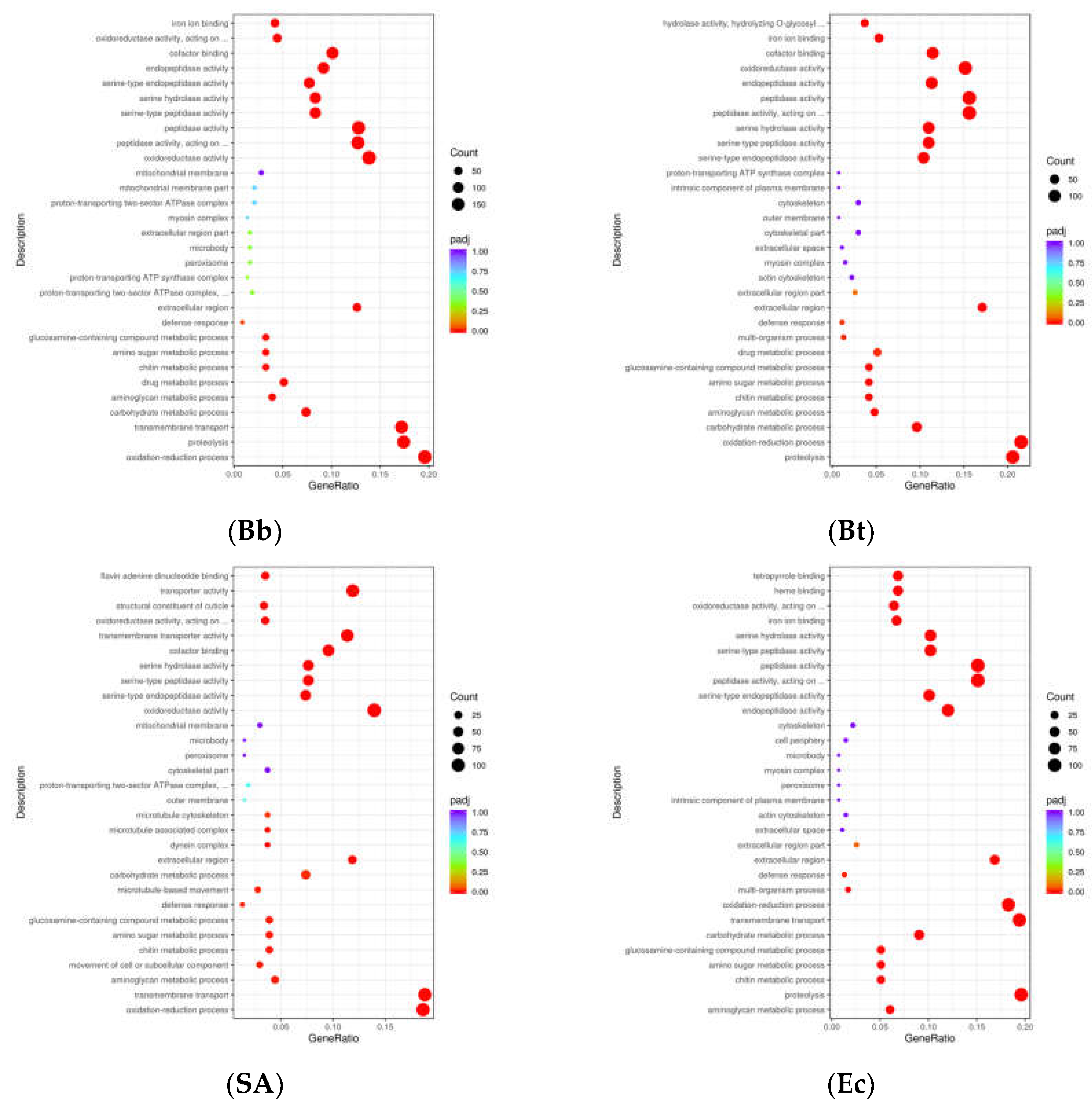

3.3. GO Functional Enrichment Analysis

GO functional enrichment analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes induced by pathogenic microorganisms in fourth-instar larvae of

S. frugiperda. The results showed that the differential genes were mainly distributed in Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF) (

Figure 3). In the Bb treatment, 707 unigenes were annotated to Biological Process, 125 to Cellular Component, and 1198 to Molecular Function. In the Bt treatment, 477 unigenes were annotated to Biological Process, 88 to Cellular Component, and 686 to Molecular Function. In the Ec treatment, 481 unigenes were annotated to Biological Process, 78 to Cellular Component, and 712 to Molecular Function. In the SA treatment, 368 unigenes were annotated to Biological Process, 97 to Cellular Component, and 617 to Molecular Function. These results indicate that the level of changes in differentially expressed genes varies after infection of

S. frugiperda fourth-instar larvae by different pathogenic microorganisms. However, most changes are concentrated in Molecular Function, followed by Biological Process, with relatively fewer differentially expressed genes in Cellular Component.

3.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (P < 0.05) induced by microbial treatments in S. frugiperda were analyzed using KEGG pathway enrichment. The results showed that in the Bb-treated group, among 3,593 DEGs, KEGG analysis identified Carbon metabolism as the most significantly enriched pathway, containing the highest number of differentially expressed genes. In the Bt-treated group, out of 2,571 DEGs, significantly enriched KEGG pathways included Biosynthesis of cofactors, Lysosome, Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, and Carbon metabolism. In the Ec-treated group, among 1,870 DEGs, significantly enriched pathways included Peroxisome, Lysosome, and Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction. In the SA-treated group, among 2,419 DEGs, significantly enriched pathways were Biosynthesis of amino acids, Carbon metabolism, and Motor proteins.

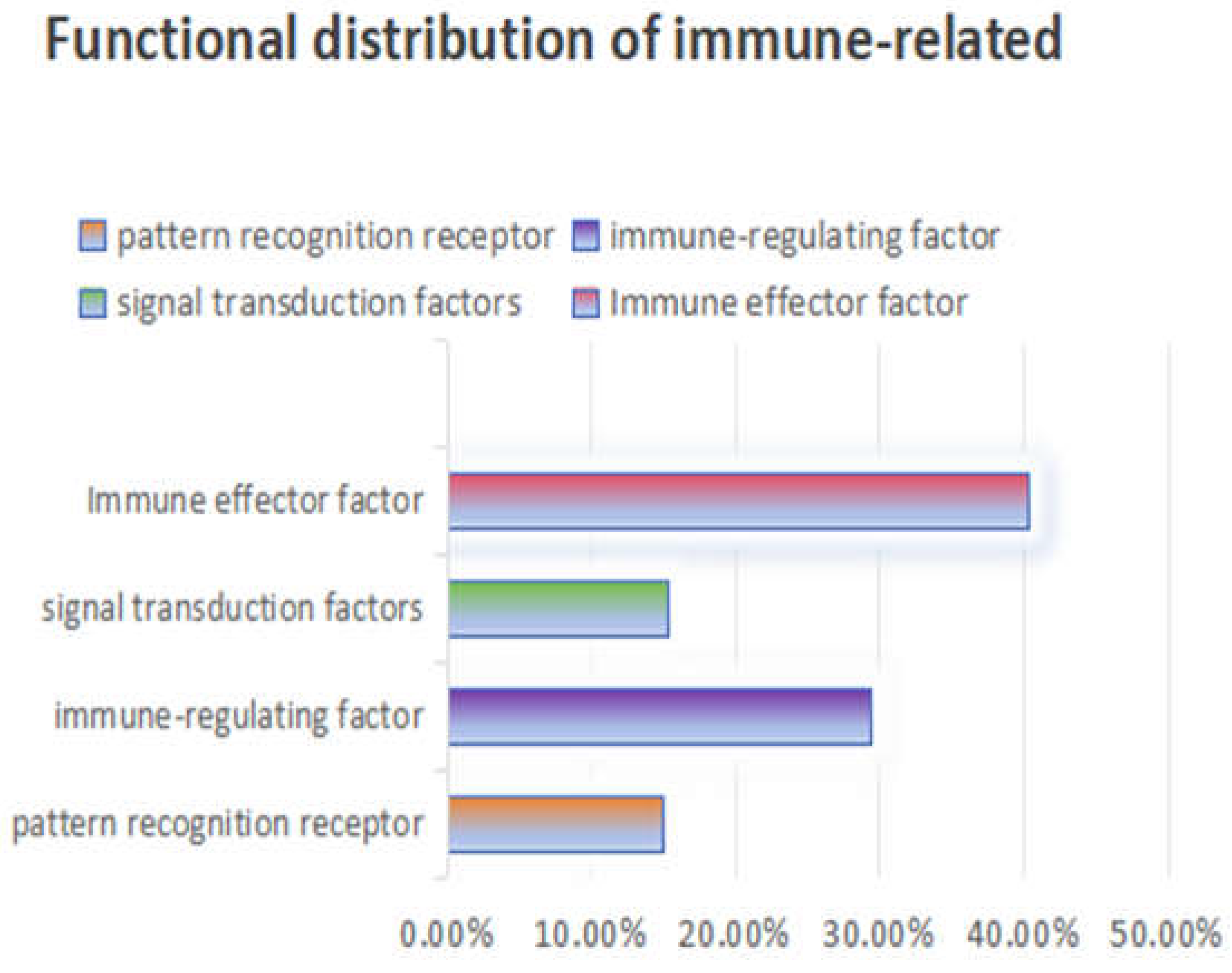

3.5. Screening of Immune-Related Genes

By comparing the immune-related gene sequences of known model insects, 655 immune-related genes of various categories were identified from the transcriptome sequences of S. frugiperda (see Appendix 1). Based on their functions, these genes were categorized into four major groups: pattern recognition receptors, immune effectors, signal transduction factors, and immune regulatory factors. Signal transduction factors include components of the IMD, Toll, JAK/STAT, JNK, RNA interference, and autophagy immune pathways.

Specifically, the study identified 98 pattern recognition receptors belonging to 12 gene families, accounting for 14.96% of the total immune-related genes. The serine protease inhibitor family with clip domains and the serine protease family were found to have 20 and 61 members, respectively, which regulate the amplification and attenuation of extracellular immune signals. These immune regulatory factors account for 12.37% of the total immune-related genes.

In the IMD, Toll, JAK/STAT, JNK, RNA interference, and autophagy immune signal transduction pathways of S. frugiperda, 212 components responsible for signal transduction were identified, representing 32.37% of the total. Immune effectors in insects, such as antimicrobial peptides, lysozymes, melanin, and antioxidative molecules, were also identified. A total of 264 immune effectors, accounting for 40.30% of the total immune-related genes, were identified in this study.

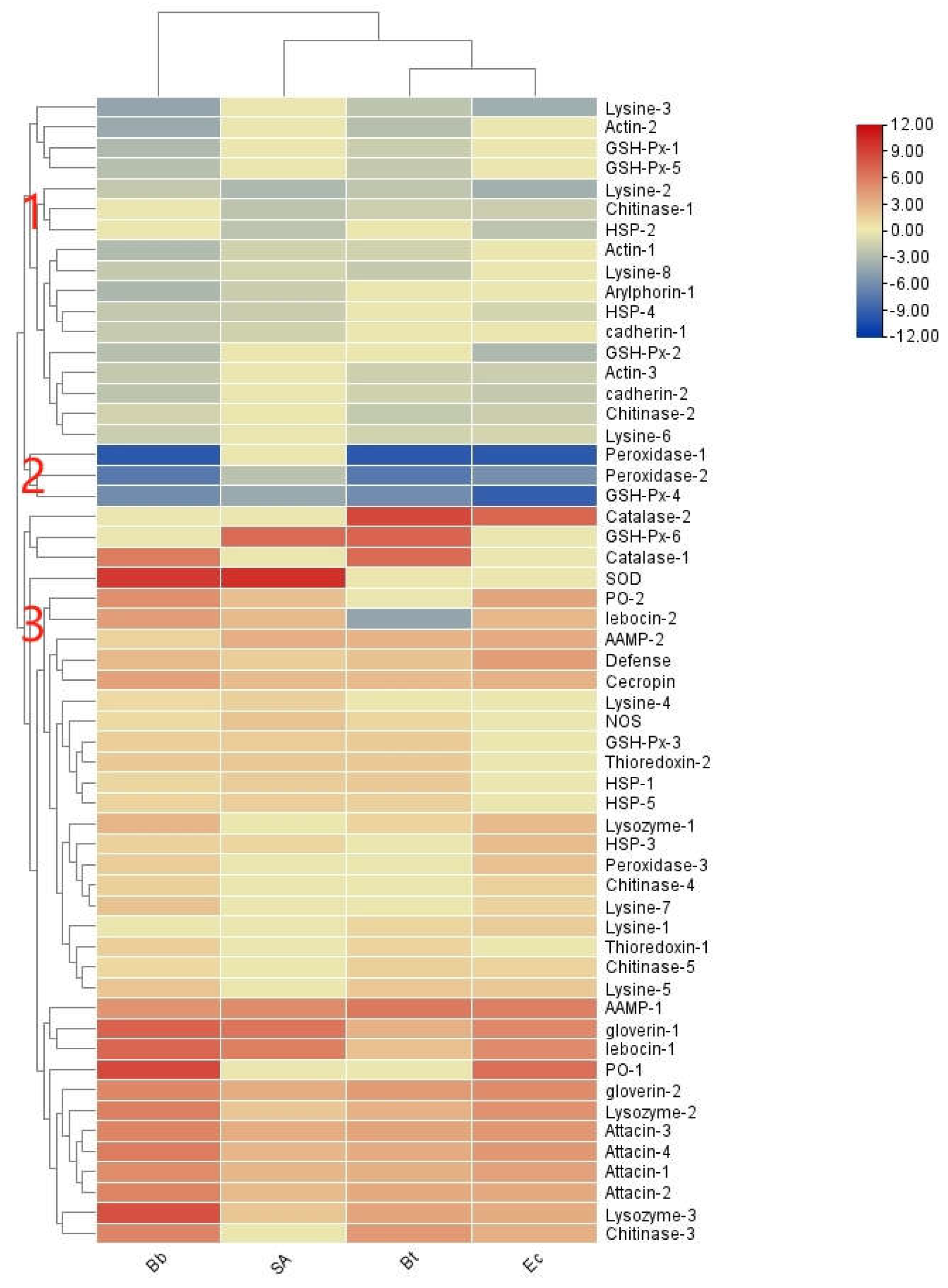

As shown in

Figure 4, when

S. frugiperda is infected by pathogenic microorganisms, its pattern recognition receptors, immune effectors, signal transduction factors, and immune regulatory factors are all activated. Among these, genes related to immune effectors constitute the largest proportion, indicating that through long-term biological evolution,

S. frugiperda has developed a relatively complete innate immune system.

3.6. Analysis of Immune-Related Genes

The immune gene families of S. frugiperda are complex, with functional differences observed among genes within the same family. This study conducted phylogenetic and expression variation analyses of immune genes in comparison with known model species to better understand the functions and expression trends of immune-related genes in S. frugiperda.

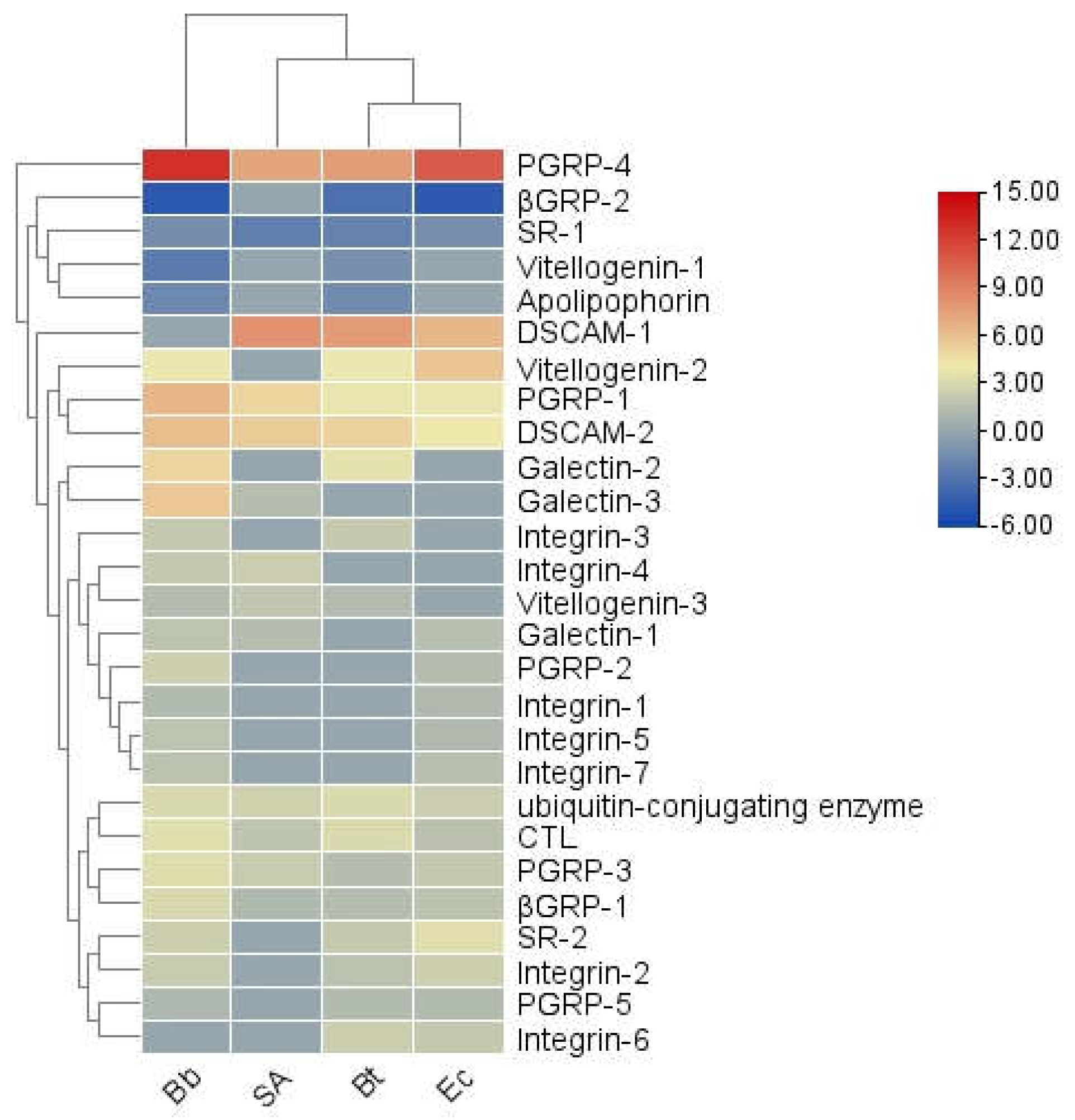

3.6.1. Pattern Recognition Receptors

Insects rely on unique

pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect

pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on the surfaces of microorganisms. In the transcriptome of

S. frugiperda, 12 types of PRRs were identified (see Appendix 1). Among them,

Integrin was the most abundant, with 27 unigenes, followed by

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (20),

DSCAM (11),

PGRP (9),

SR (9),

Galectin (8),

Vitellogenin (5),

βGRP (3),

C-type lectin (2),

ApoLp (2), TEP (1), and

Croquemort (1). The transcription levels of PRR genes varied significantly under different pathogenic microbial infections (

Figure 5). Specifically, SR-1 was consistently and significantly downregulated following all pathogen treatments. In contrast,

PGRP-1, -3, -4,

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme,

DSCAM-2,

βGRP-1, and

CTL were significantly upregulated under all pathogenic conditions. Meanwhile,

βGRP-2,

Vitellogenin-1, and

ApoLp exhibited an overall downregulation trend. These findings suggest that different

PRR genes may play distinct roles in immune pathways during the recognition and response to pathogenic microorganisms.

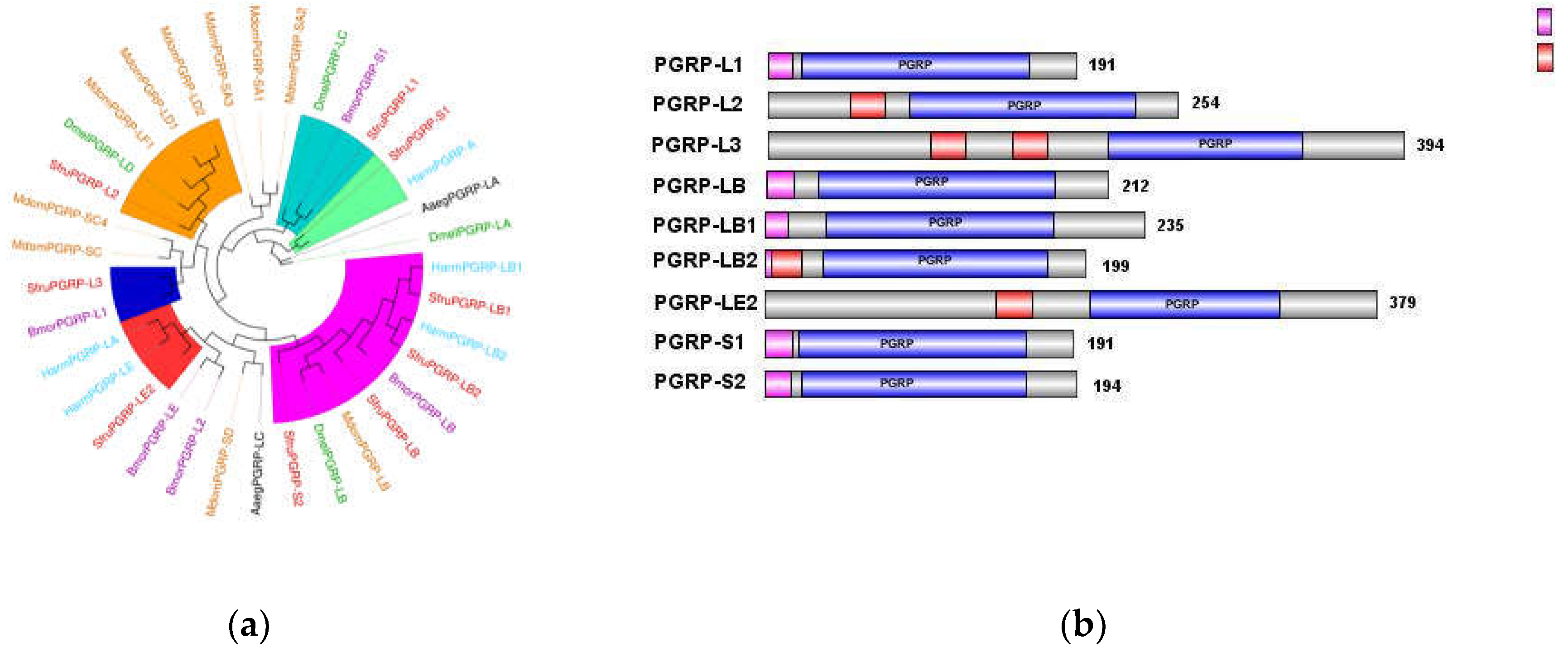

The most notable feature of the

PGRP (

Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein) family is the presence of a T4 bacteriophage lysozyme domain [

14]. In insects,

PGRPs are classified into three types based on molecular weight: short (S), intermediate (I), and long (L) [

15].

The short type (S), with a molecular weight of approximately 20–25 kD, typically contains signal peptides, lacks transmembrane domains, and functions as small, secreted extracellular proteins. The intermediate type (I) has a molecular weight of approximately 40–45 kD. The long type (L), generally exceeding 90 kD in molecular weight, can be further subdivided into two subtypes: intracellular proteins lacking both signal peptides and transmembrane domains, and transmembrane proteins containing signal peptides and transmembrane domains, which exist as transmembrane proteins [

16].

In the transcriptome Unigene data of

S. frugiperda, nine

PGRP family genes were identified and named

PGRP-L1, L2, L3, LB, LB1, LB2, LE2, S1, S2 based on sequence characteristics and multiple sequence alignments. As shown in

Figure 6 (b), the amino acid sequences of

PGRP-S1 and

PGRP-S2 contain signal peptides, suggesting that they are likely secreted extracellular proteins of the short type and may participate in melanization upon receiving signals.

PGRP-L1 and

PGRP-

LB1 lack signal peptides and transmembrane domains, indicating they function as intracellular proteins.

PGRP-L2, L3, LB2, and

LE2 contain transmembrane domains, suggesting that they may act as transmembrane proteins to activate immune signaling pathways. Notably,

PGRP-L3 contains two transmembrane domains, indicating a potentially broader role in immune recognition compared to other proteins.

Phylogenetic tree analysis revealed that the PGRP gene family of S. frugiperda is closely related to those of lepidopteran insects such as Bombyx mori and Helicoverpa armigera. The results of the phylogenetic analysis align well with previous nomenclature based on sequence characteristics, with L-type PGRPs clustering together and S-type PGRPs forming their own distinct clade.

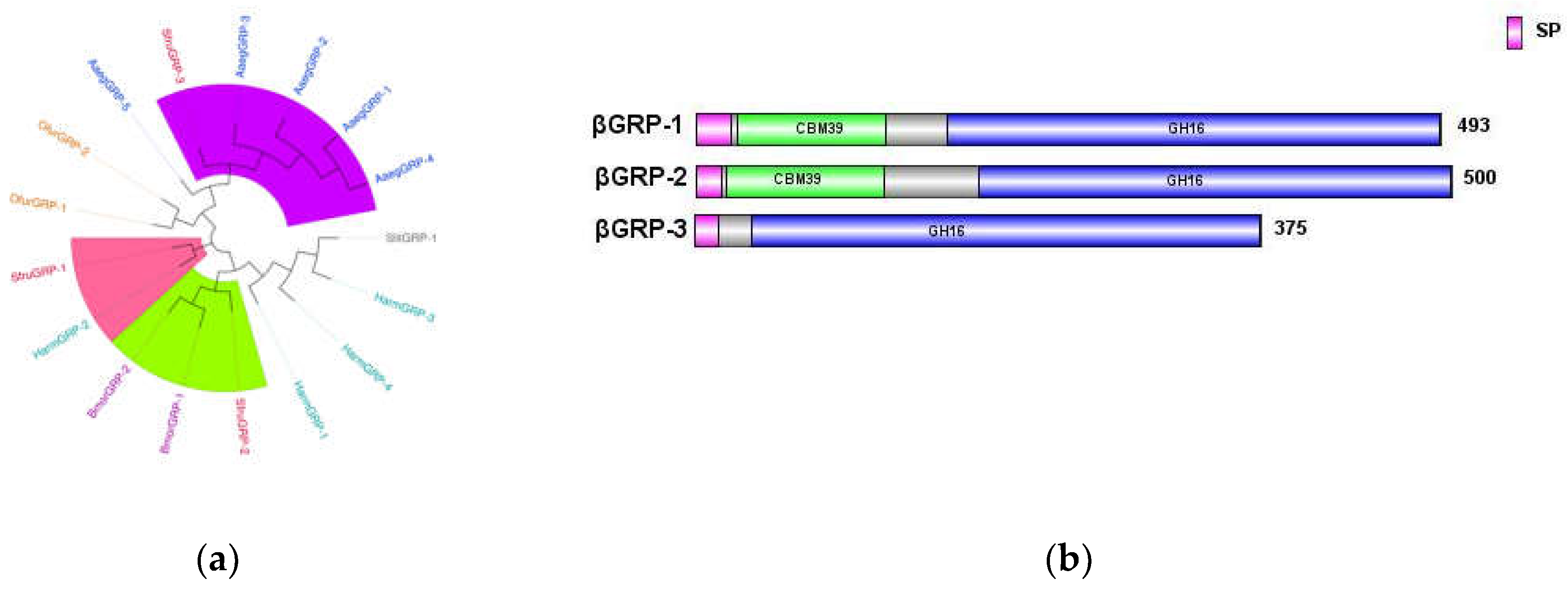

βGRP, also known as

GNBP (

Gram-negative binding protein), contains two main conserved domains: an N-terminal

β-1,3-glucan recognition domain and a C-terminal

β-1,3-glucan recognition domain lacking catalytic residues. These domains are responsible for recognizing the cell wall polysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria or β-1,3-glucans in fungi [

17,

18].

In the transcriptome data of

S. frugiperda, three homologous

βGRP genes were identified, all of which contained signal peptide sequences at their N-terminal ends. This indicates their ability to be secreted into the hemolymph to perform pathogen recognition functions. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that

βGRP1 of

S. frugiperda clustered with

HamGRP-2 from

H. armigera, while

βGRP2 clustered with

BmorGRP-1 and

BmorGRP-2 from

B. mori. Previous studies have demonstrated that

BmorGRP-1 can bind to fungi and bacteria, activating phenoloxidase-mediated melanization [

19]. Thus,

βGRP2 is likely a key recognition receptor in the immune signaling pathways for pathogenic microorganisms. Meanwhile,

βGRP3 clustered with the

βGRP family of Aedes aegypti, suggesting evolutionary similarity.

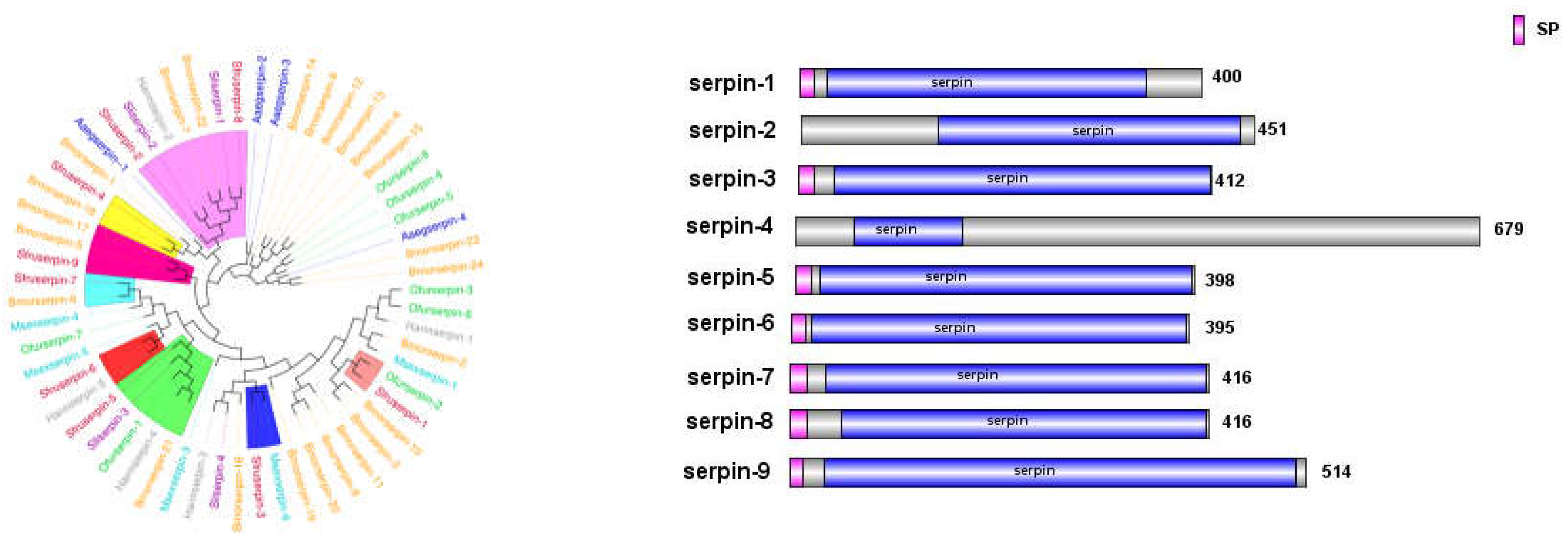

3.6.2. Immune Regulatory Factors

Regulatory factors in insect plasma include

serine proteases, their non-catalytic homologs

(serine protease homologs, SPH), and

serine protease inhibitors (

serpins).

Serine proteases (SPs), one of the largest protein families in insects, amplify invading immune signals through proteolytic cascade reactions, especially those containing clip domains [

20].

Serpins, as inhibitors of

SPs, attenuate immune signals and provide feedback regulation. Members of a protein superfamily,

serpins often form covalent complexes with

SPs, blocking

SP cascades to precisely regulate the

prophenoloxidase cascade and the Toll pathway [

21].

In the transcriptome of

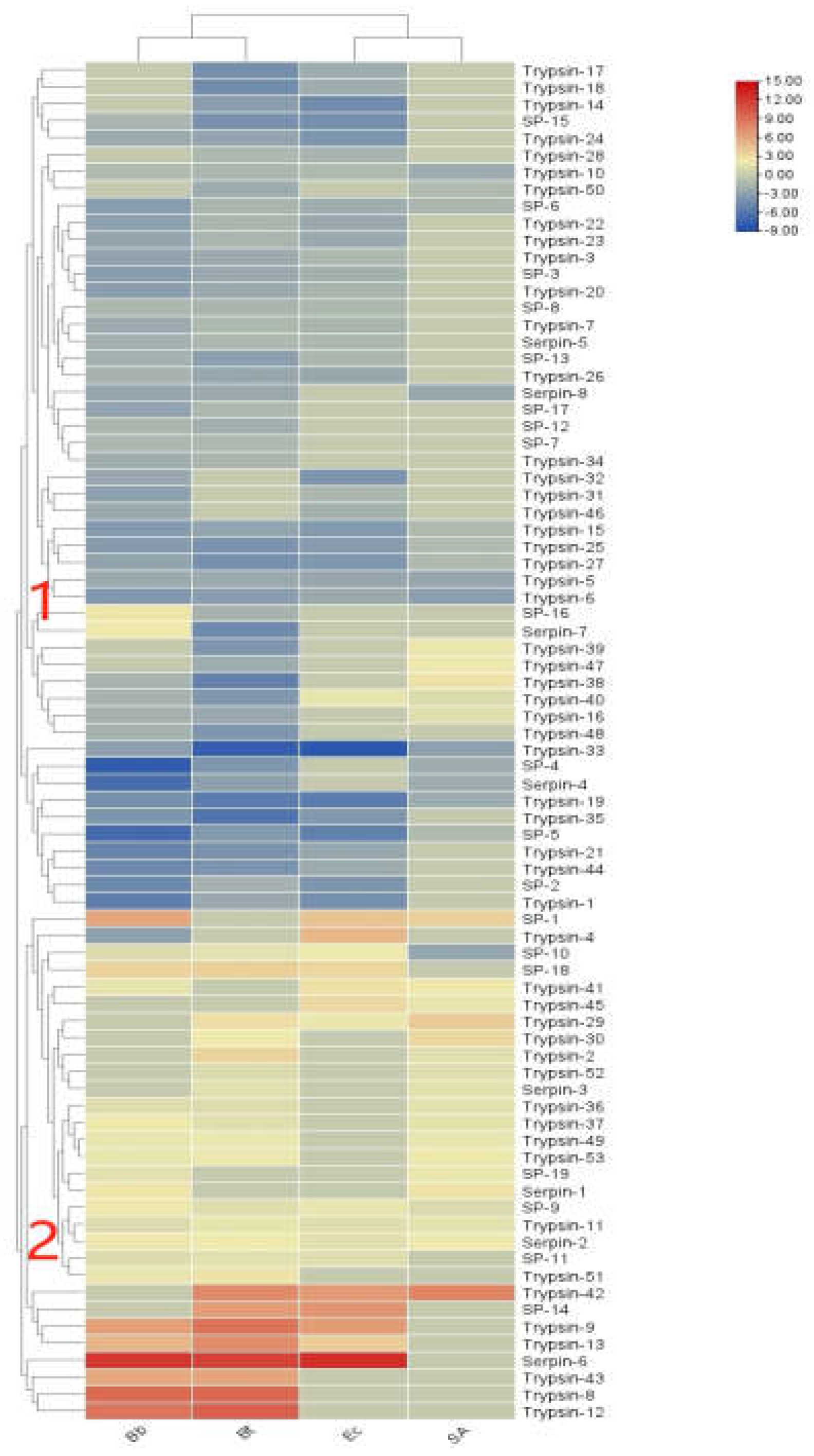

S. frugiperda, 61 serine protease (SP) genes and 20 serine protease inhibitor serpin genes were identified (see Appendix 1). As shown in

Figure 9, the expression levels of immune regulators in

S. frugiperda exhibited varied transcriptional responses following infection by different pathogenic microorganisms. Overall, they can be divided into two clusters. Cluster 1 showed a general downregulation trend after infection with various pathogens, likely due to the involvement of serpin genes. In contrast, Cluster 2 exhibited a general upregulation trend, indicating that amplification of immune signaling in response to different pathogens requires the coordinated participation of multiple

serine proteases,

serine protease inhibitors, and

trypsins, which collectively regulate immune signal transmission.

Figure 8.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of immunomodulatory factors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 8.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of immunomodulatory factors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

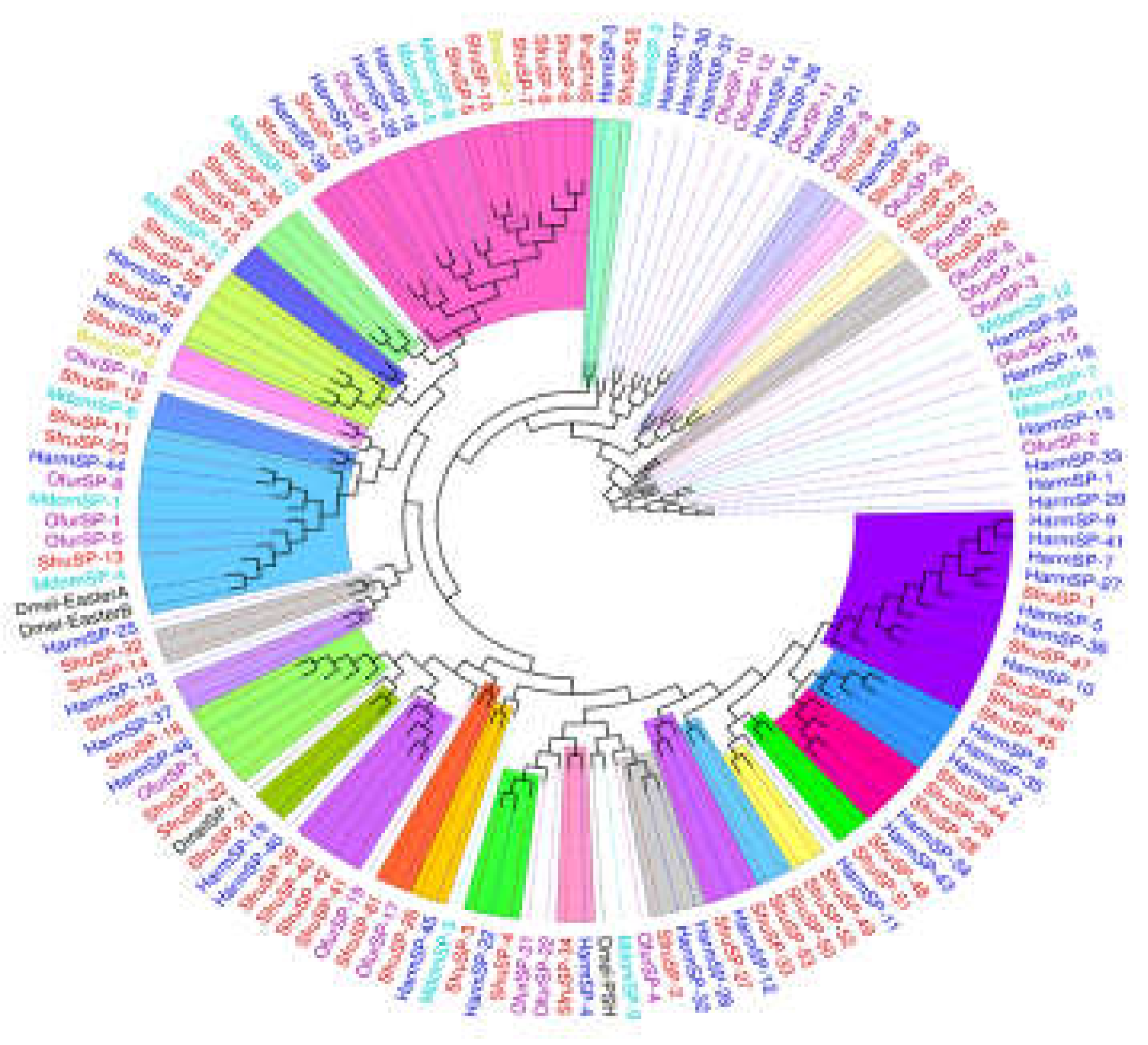

Phylogenetic tree analysis revealed that the

serine proteases of

S. frugiperda are closely related to those of other lepidopteran insects, including

B. mori,

Ostrinia furnacalis, and

H. armigera. Among these,

SfurSP-59 clustered with

HarmSP-6. Previous research by Xiong et al. demonstrated that

cSP6 in

H. armigera is a key activator of

prophenoloxidase, suggesting that

SfurSP-59 may have a similar function and play a role in the activation of melanization [

21].

The serpins of

S. frugiperda also showed close phylogenetic relationships with those of lepidopteran and hymenopteran insects. Among the identified

serpin genes, seven (SPN genes) possess complete domains and signal peptide sequences, indicating their extracellular functionality. Studies have shown that

MsSerpin-6 in

Manduca sexta can block upstream signals in the

prophenoloxidase cascade [

22].

In the phylogenetic tree, Sfruserpin-3 clustered with MsSerpin-6, suggesting that Sfruserpin-3 may have a similar function. This indicates that Sfruserpin-3 could participate in the precise regulation of melanization and the Toll signaling pathway in S. frugiperda.

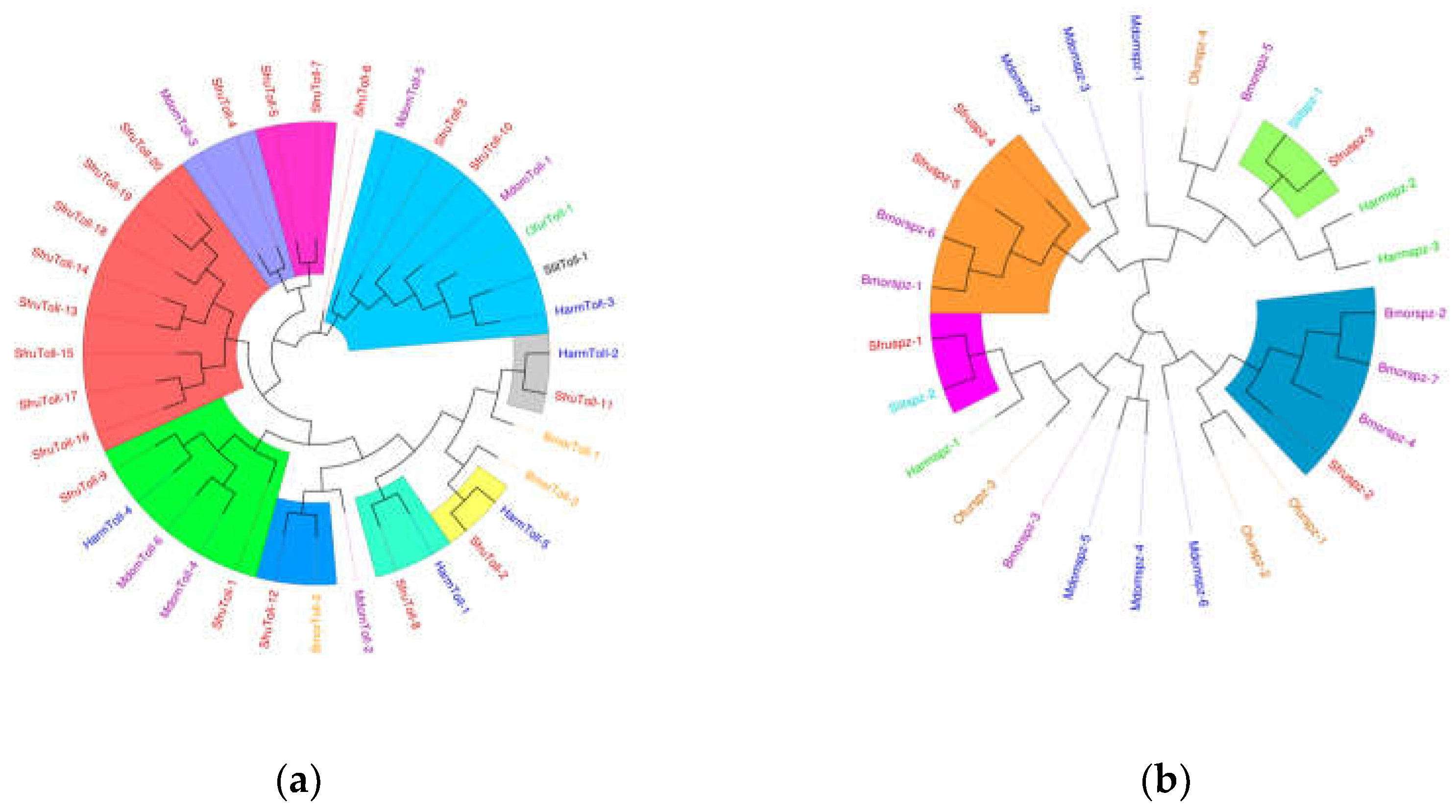

3.6.3. Signal Transduction Factors

The innate immune signaling pathways in the model insect

Drosophila melanogaster include four primary pathways: Toll, Imd, JAK/STAT, and JNK4. Among these, the Toll and Imd pathways have been gradually confirmed in many lepidopteran insects [

23,

24]. The Toll signaling pathway in insects is evolutionarily highly conserved and primarily defends against fungi and Gram-positive bacteria. In

S. frugiperda, the Toll signaling pathway is relatively complete, encompassing genes encoding the extracellular cytokine

Spätzle, transmembrane receptors such as

Toll proteins,

tolloid-like proteins, and

toll-like receptors, as well as intracellular signaling components

Tube,

myeloid differentiation factor 88,

Pelle kinase, the

inhibitor molecule Cactus,

Cactin,

Pellino, and the

NF-κB transcription factor dorSAl.

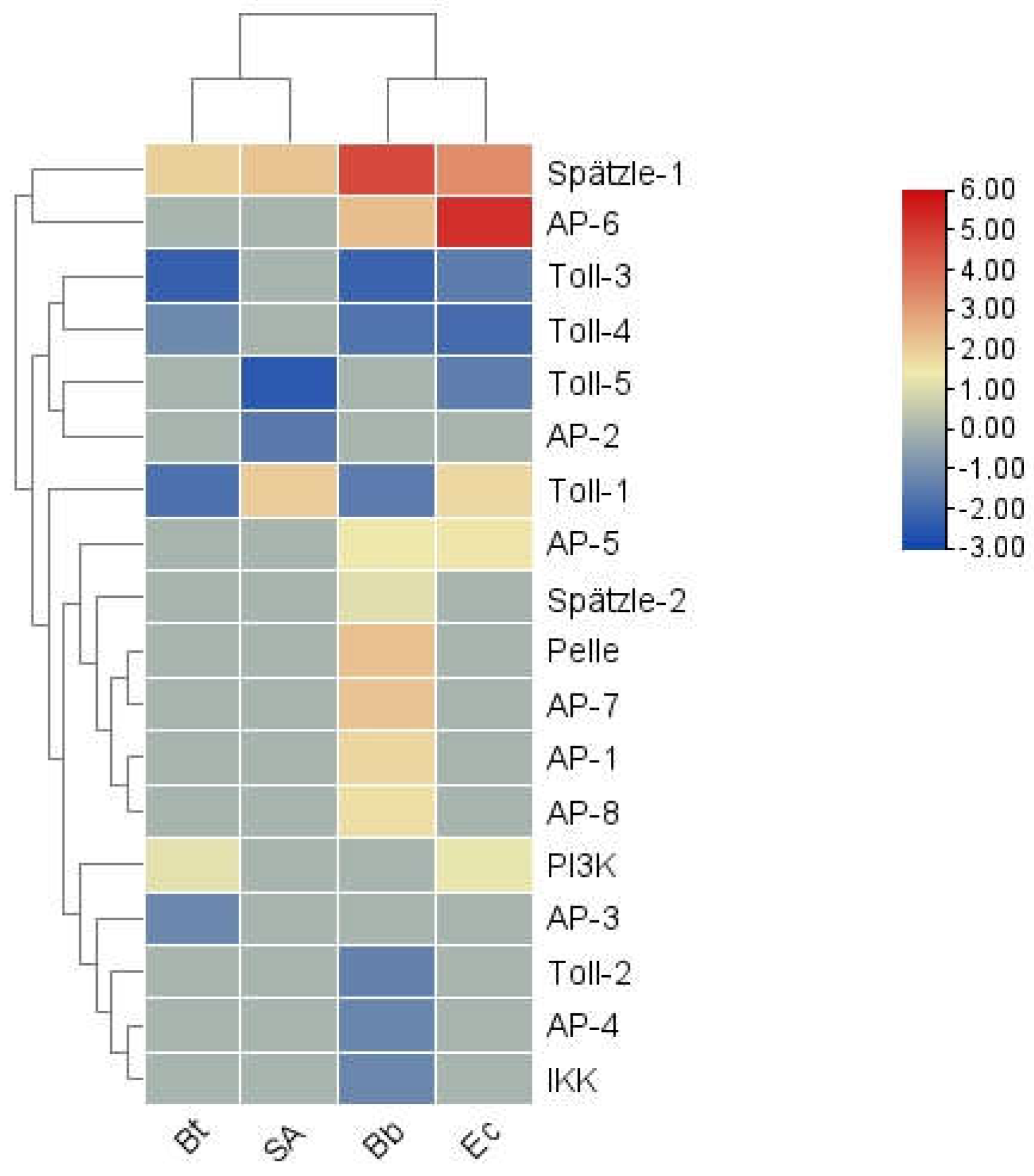

A total of 20 Toll genes were identified in

S. frugiperda. As shown in

Figure 12(a), these Toll genes cluster closely with those of other lepidopteran insects, such as

B. mori and

H. armigera. The red-highlighted region of the phylogenetic tree shows that all Toll sequences of

S. frugiperda form a unique homolog cluster, suggesting that these genes underwent a certain degree of variation after species differentiation.

Figure 11.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of signal transduction factors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 11.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of signal transduction factors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Toll receptors in insects do not directly detect foreign substances; instead, they function as receptors for the cytokine

Spätzle. In

S. frugiperda, five

Spz genes were identified. Studies have shown that activating

Bmorspz1 in

B. mori increases the mRNA levels of

antimicrobial peptides [

25], and

BmorSpz4 can activate intracellular Toll signaling to enhance the host's immunity against external infections [

26]. Given the homology between

SfruSpz2 in

S. frugiperda and

BmorSpz4 in

B. mori, it is hypothesized that

SfruSpz2 may act as a cytokine binding to

Toll receptors in

S. frugiperda, regulating

Toll pathway activity and influencing the host's immune response.

The IMD pathway is a critical pathway for defending against Gram-negative bacteria. In S. frugiperda, key regulatory genes identified in this pathway include 1 TAK1, 2 IKKs, 1 Sickie, 1 Akirin, and 6 Cullins (see Appendix 1).

The JNK and JAK-STAT signaling pathways are also essential immune defense mechanisms in insects. In the transcriptome data of S. frugiperda, the core genes of the JAK-STAT pathway were identified, including those encoding JAK kinase (Hopscotch) and STAT factors, as well as negative regulatory genes SOCS and PIAS.

In terms of expression levels, the signal transduction factor genes were generally downregulated, with the exception of Spätzle-1 and AP6, which exhibited upregulated trends under certain pathogenic infections. Overall, the four innate immune signaling pathways are interconnected, working in concert to transduce danger signals and ultimately stimulate the production of immune effector molecules.

3.6.4. Immune Effector Factors

Microbial induction can lead to the production of numerous effectors, which are small molecular weight proteins. In the transcriptome of

S. frugiperda, a total of 264 effector factor genes were identified (see Appendix 1). Common effectors include

antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), melanin mediated by

prophenoloxidase (PPO),

lysozymes (Lys), and

reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

27,

28].

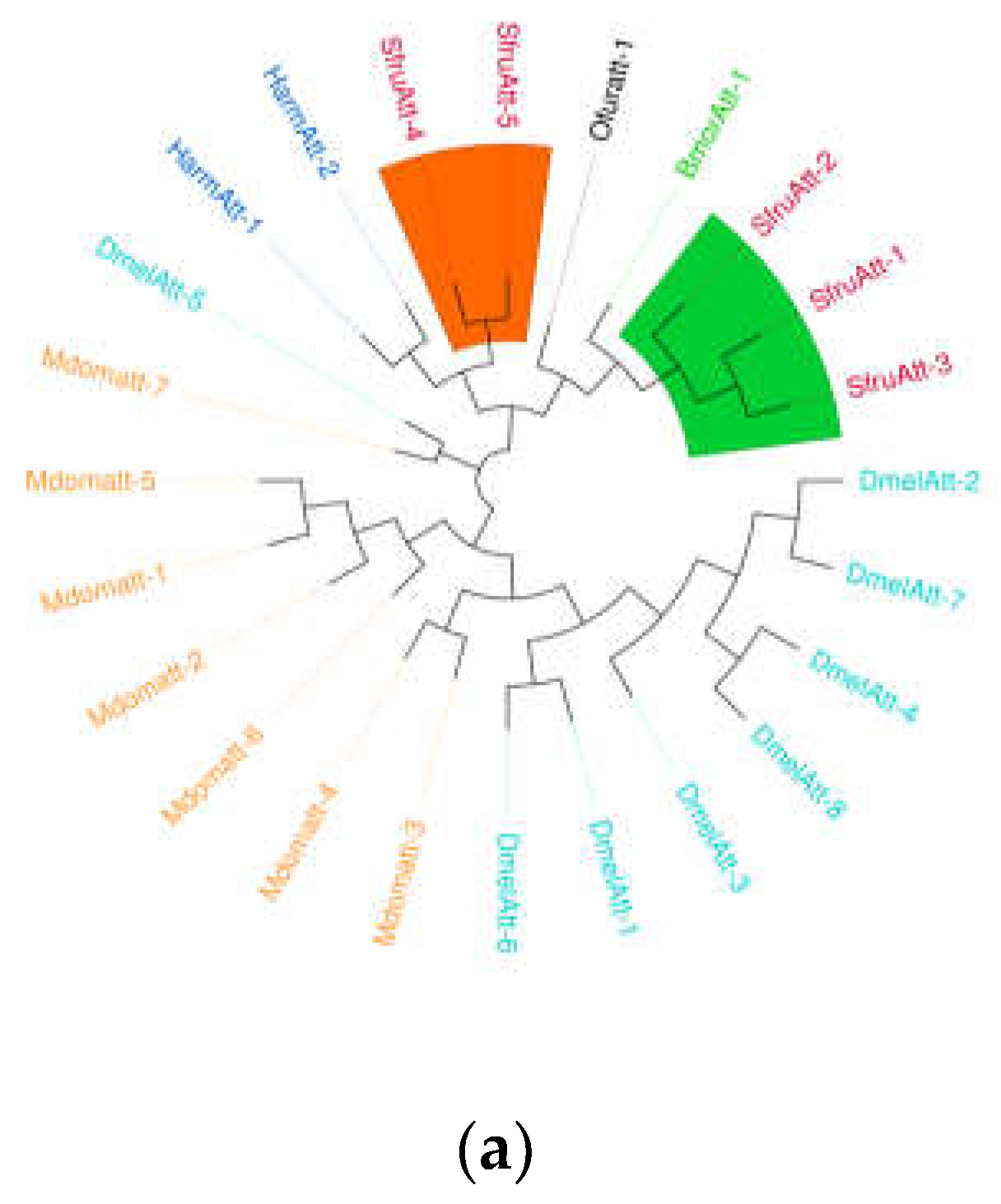

In S. frugiperda, five types of AMP genes were identified: 2 unigenes of drosomycin, 5 of attacin, 2 of defensin, 1 of holotricin, 1 of cecropin, and 2 of anionic antimicrobial peptides. Additionally, the transcriptome revealed 7 unigenes of lysozyme, 11 of chitinase, 18 of heat shock proteins (HSP), and 39 of actin.

Based on expression patterns, immune effector factors were categorized into three clusters:Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 showed an overall downregulation trend following infection by various pathogenic microorganisms, with Cluster 2 displaying high expression levels, suggesting a role as negative regulatory components.Cluster 3 exhibited overall high expression levels, functioning as positive regulatory components.

As shown in

Figure 14,

S. frugiperda contains four

gloverin genes, which are antimicrobial peptides specific to lepidopteran species. In the phylogenetic tree, these genes cluster with those of

H. armigera. Most

lysozyme genes also cluster with those of

H. armigera, indicating a close evolutionary relationship with other lepidopteran species. In contrast,

attacin forms a distinct clade in the phylogenetic tree, suggesting considerable evolutionary divergence of antimicrobial peptides among different insect species.

3.7. Effects of Pathogenic Microbial Infection on the Expression of PGRP and βGRP Immune Genes in S. frugiperda

The studies above demonstrate that during pathogenic microbial infections, various immune genes in S. frugiperda are activated to combat different types of pathogens. To further validate these findings, the immune gene familie peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) and β-glucan recognition proteins (βGRPs), which play critical roles in initiating innate immunity, were selected for validation analysis.

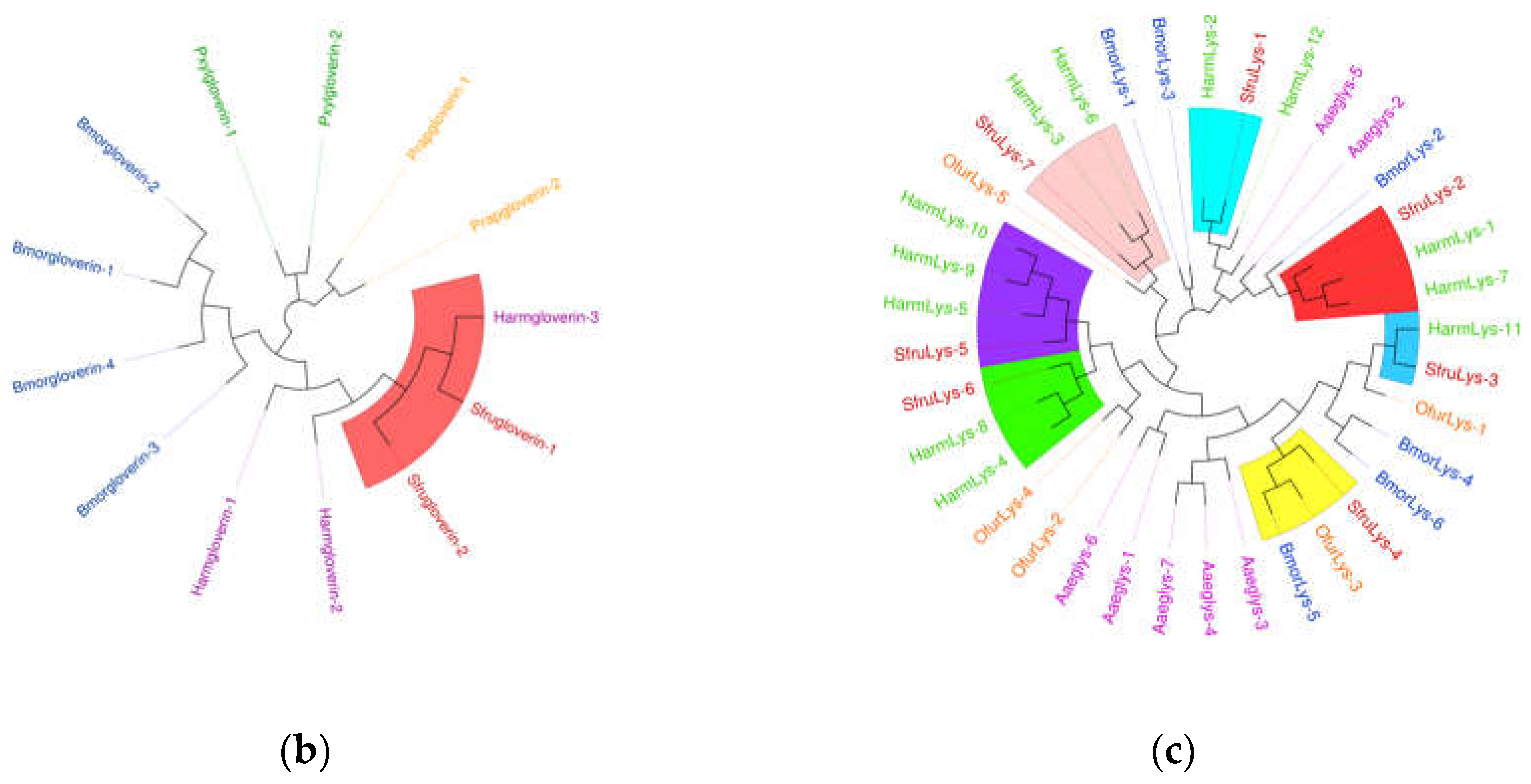

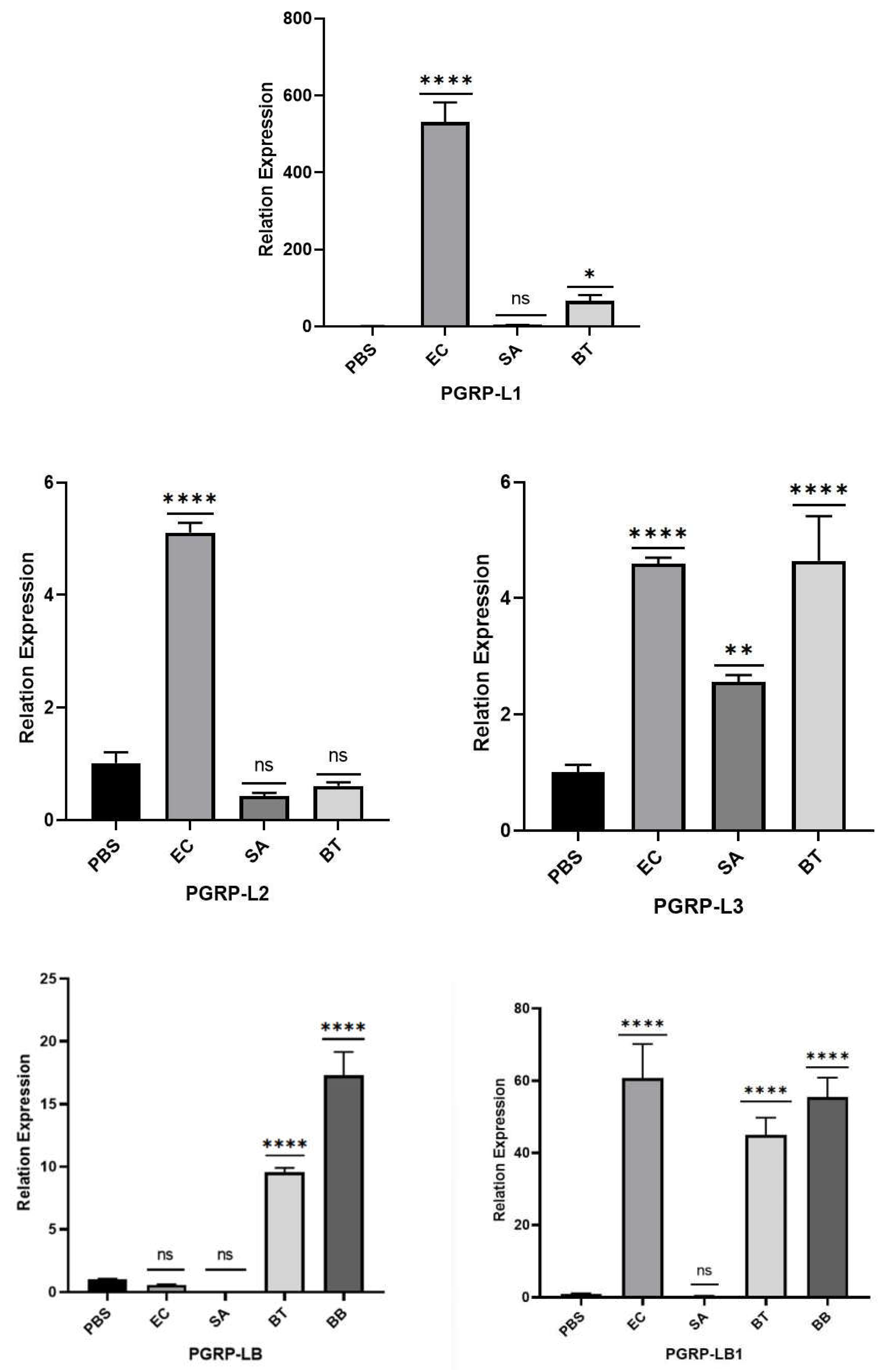

Infections by three types of bacteria induced varying degrees of expression in both long-form (L) and short-form (S) PGRP genes in the fourth instar larvae of S. frugiperda. Among the long-form genes, the expression levels of PGRP-LE2, LB1, L1, L2, and L3 decreased in the order of Ec > Bt > SA, with Ec treatment inducing expression levels 6.88, 60.36, 529.78, 5.04, and 4.57 times higher than the control (CK), respectively. The expression of PGRP-LE2 under SA treatment was significantly lower than the control. PGRP-LB and LB2 exhibited the highest expression levels under Bt treatment, with levels 9.55 and 43.22 times higher than the control, respectively. However, PGRP-LB showed no significant differences in expression between Bt, SA, and the control.

For short-form genes, PGRP-S1 and S2 exhibited the highest expression levels under Bt treatment. Notably, the expression of PGRP-S1 under Bt treatment was significantly higher than the control, reaching 2700.55 times the control level. Conversely, the expression of PGRP-S2 under Ec treatment was significantly lower than the control.

As pattern recognition receptors, some

PGRPs recognize and bind to external pathogens, subsequently activating the Toll and Imd pathways. Lysine-type PGN primarily activates the Toll pathway, while DAP-type PGN activates the Imd pathway [

29].

These findings suggest that PGRP-LE2, LB1, L1, L2, and L3 genes may be involved in the activation of the Imd pathway by Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus and B. thuringiensis. Conversely, PGRP-S1 and S2 genes may activate the Toll pathway in response to Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli.

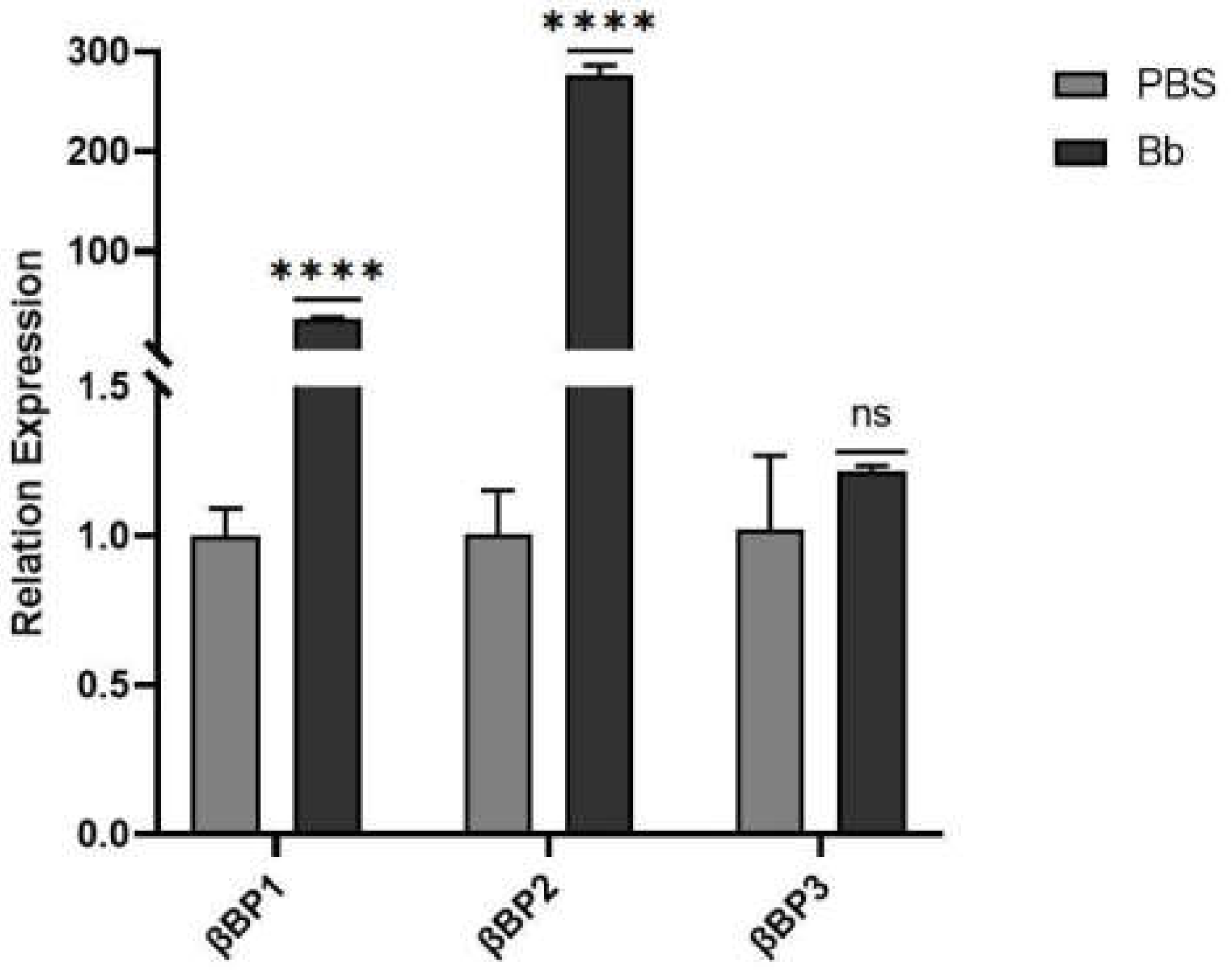

As shown in

Figure 16, induction by the fungus

B. bassiana did not result in a significant difference in the expression of the pattern recognition receptor gene

βGRP-3 compared to the control. However, the expression levels of

βGRP-1 and

βGRP-2 increased significantly, reaching 32.48 and 274.52 times the levels of the control group, respectively. These findings suggest that

βGRP-1 and

βGRP-2 are critical binding proteins in

S. frugiperda in response to induction by

B. bassiana.

4. Discussion

With the continuous advancements in next-generation sequencing, insect immunogenomics research has garnered increasing attention, expanding its focus beyond model insects such as

Drosophila and

Bombyx mori. In recent years, innate immunity in insects has become a research hotspot. The components of the innate immune systems of many insects have been gradually elucidated. For example, in 2013, the immune system of the tobacco hornworm

Manduca sexta was characterized, identifying 232 immune-related genes [

30]. In 2014, Liu et al. identified 190 immune-related genes in the Asian corn borer

Ostrinia furnacalis [

29]. In 2015, the immune systems of the agricultural pests

Helicoverpa armigera and

Plutella xylostella were analyzed, with 233 and 149 immune genes identified, respectively [

21,

31]. In 2018, the immune system of the invasive pest

Dendroctonus valens was revealed by Xu Letian's research group at Hubei University, identifying 185 immune-related genes [

32]. As a globally significant migratory agricultural pest under surveillance, the fall armyworm (

Spodoptera frugiperda) remains poorly understood in terms of its innate immune system. However, the widespread use of

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)-based biopesticides in pest control poses a high risk of resistance development. By targeting the host immune response to pathogens and reducing its innate immunity, novel green and effective pest management strategies could be developed.

To this end, this study employed transcriptome sequencing to comprehensively analyze the composition and dynamic changes of immune genes in fall armyworm larvae under different bacterial and fungal infections. A total of 655 immune-related genes were identified, including four major categories: pattern recognition receptors, immune effectors, signal transduction factors, and immune regulators.

This study analyzed these four categories of immune factors in fall armyworm, showing that the immune gene repertoire of this species is relatively conserved, possessing a complete set of components from pathogen recognition to the production of effectors, without significant loss. This suggests that

S. frugiperda has a well-developed innate immune defense system. However, some insects exhibit component loss during evolution, such as the absence of the JAK/STAT pathway ligand hopscotch protein in the genome of

B. mori [

17] and the absence of the Toll pathway ligand

MyD88 in the transcriptome of

P. xylostella [

31]. The systematic identification and analysis of immune gene families in

S. frugiperda not only provide insights into their evolutionary history but also establish a theoretical foundation for further functional analysis of these immune genes.

Among pattern recognition receptors, different genes exhibited varied trends in response to pathogens, suggesting their involvement in distinct pathways for combating microbial infections. Phylogenetic analysis and expression validation revealed that

S. frugiperda PGRP-L2 clustered with

Drosophila PGRP-LD, which is associated with maintaining gut microbial homeostasis [

29]. Previous studies have shown that

BmPGRP-S1 and

HaPGRP-A can activate the

phenoloxidase cascade, while

DmPGRP-LC mediates the regulation of the

Drosophila Imd pathway and initiates phagocytosis and Imd signaling by recognizing Gram-negative bacteria [

33,

34,

35]. It is hypothesized that

S. frugiperda PGRP-L1 and

PGRP-S1 may share similar functions. In the transcriptome database, three

βGRP genes were identified in

S. frugiperda. Studies have shown that

B. mori βGRP1 can bind bacterial cell wall polysaccharides and

β-1,3-glucan, activating

PO-mediated melanization [

36]. It is inferred that

S. frugiperda βGRP2, which shares conserved glucan-binding domains at its N-terminus with

B. mori βGRP1, might serve as a key receptor for bacterial detection and activation of downstream immune signaling pathways.

Immune regulators in

S. frugiperda mainly include serine proteases and serine protease inhibitors, whose expression levels varied in response to pathogenic infections but function cooperatively in immune signaling. Previous studies found high similarity between

H. armigera cSP6 and

M. sexta PAP3 [

19], the latter being critical for

PPO activation. It is hypothesized that

S. frugiperda SP-59 has similar functions in melanization activation. Serine protease inhibitors provide feedback regulation to attenuate immune signaling. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that

S. frugiperda Serpin-3 might share similar functions with

M. sexta Serpin-6, regulating melanization and Toll signaling pathways [

21]. Signal transduction factors were mainly identified in the Toll, Imd, JAK/STAT, and JNK pathways. Toll is the primary signaling pathway in insects for defense against fungi and Gram-positive bacteria. Over evolutionary time, it has formed unique homologs, with

Spätzle cytokines in

S. frugiperda modulating Toll pathway activity to influence host immunity.

Most immune effectors showed increased expression following pathogen infection. Phylogenetic analysis of gloverin, an antimicrobial peptide unique to Lepidoptera, showed that S. frugiperda gloverin clustered with H. armigera, indicating functional similarity. Attacin may have undergone significant variation during evolution, while lysozyme shares close evolutionary relationships within Lepidoptera. These adaptations likely enhance host resilience in complex and dynamic environments.

As two major classes of pattern recognition receptors initiating immune responses, expression analysis showed significant upregulation of

PGRP-S1 and

S2 following infection with

Staphylococcus aureus and

B. thuringiensis, while infections with

Escherichia coli led to increased expression of

PGRP-LE2, LB1, L1, L2, and

L3. These findings suggest that

PGRP genes are involved in pathway regulation and activation. Based on structural analysis, it is inferred that

PGRP-S1 and

S2 are likely involved in Toll pathway activation, while

PGRP-LE2, LB1, L1, L2, and

L3 participate in Imd pathway activation [

37,

38,

39]. Additionally, infection with

Beauveria bassiana significantly upregulated

βGRP-1 and

βGRP-2 expression, indicating their role in activating

PO-mediated melanization [

19].

This study has clarified the immune transcriptome of S. frugiperda against different microbial pathogens. Future work will focus on identifying highly responsive and differentially expressed PGRP and βGRP genes during pathogen infections. These genes could serve as targets for developing novel insecticides, providing a valuable reference for enhancing the efficacy of existing microbial agents and designing new bio-insecticides with specific molecular targets.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) volcano plot of S. frugiperda treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) volcano plot of S. frugiperda treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 2.

Functional Classification of Unigenes in Telenomus remus Nixon.

Figure 2.

Functional Classification of Unigenes in Telenomus remus Nixon.

Figure 3.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in S. frugiperda treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 3.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in S. frugiperda treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 4.

Functional distribution of immune-related genes in S. frugiperda.

Figure 4.

Functional distribution of immune-related genes in S. frugiperda.

Figure 5.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of pattern recognition receptors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 5.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of pattern recognition receptors in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 6.

(a) Sequence structure of PGRP protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of PGRP family, in which the PGRP family of S.frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Aedes aegypti; Drosophila melanogaster; Bombyx mori; Musca domestica; Helicoverpa armigera.

Figure 6.

(a) Sequence structure of PGRP protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of PGRP family, in which the PGRP family of S.frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Aedes aegypti; Drosophila melanogaster; Bombyx mori; Musca domestica; Helicoverpa armigera.

Figure 7.

(a) Sequence structure of βGRP protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of βGRP family, in which the βGRP family of S. frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree (a) Aedes aegypti; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Ostrinia furnacalis.

Figure 7.

(a) Sequence structure of βGRP protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of βGRP family, in which the βGRP family of S. frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree (a) Aedes aegypti; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Ostrinia furnacalis.

Figure 9.

SP family phylogenetic tree, in which the SP family of S. frugiperda is marked with red font. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Musca domestica; Ostrinia furnacalis; Drosophila melanogaster.

Figure 9.

SP family phylogenetic tree, in which the SP family of S. frugiperda is marked with red font. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Musca domestica; Ostrinia furnacalis; Drosophila melanogaster.

Figure 10.

(a) Sequence structure of Serpin protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of Serpin family, in which the Serpin family of S. frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Bombyx mori; Aedes aegypti; Spodoptera litura; Ostrinia furnacalis; Helicoverpa armigera; Manduca sexta.

Figure 10.

(a) Sequence structure of Serpin protein, (b) Phylogenetic tree of Serpin family, in which the Serpin family of S. frugiperda was marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree Bombyx mori; Aedes aegypti; Spodoptera litura; Ostrinia furnacalis; Helicoverpa armigera; Manduca sexta.

Figure 12.

(a) The phylogenetic tree of the Toll family, (b) The phylogenetic tree of the Spz family, in which the S. frugiperda related family is marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree (a) Musca domestica; Ostrinia furnacalis; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori. (b) Musca domestica; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Ostrinia furnacalis.

Figure 12.

(a) The phylogenetic tree of the Toll family, (b) The phylogenetic tree of the Spz family, in which the S. frugiperda related family is marked with red fonts. Note: Insects included in the phylogenetic tree (a) Musca domestica; Ostrinia furnacalis; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori. (b) Musca domestica; Spodoptera litura; Helicoverpa armigera; Bombyx mori; Ostrinia furnacalis.

Figure 13.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of immune effectors in S.frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 13.

Cluster heat map of differential expression of immune effectors in S.frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 14.

Phylogenetic analysis of antimicrobial peptides in S. frugiperda. Note: (a) Drosophila melanogaster; Musca domestica; Helicoverpa armigera; Ostrinia furnacalis. (b).

Figure 14.

Phylogenetic analysis of antimicrobial peptides in S. frugiperda. Note: (a) Drosophila melanogaster; Musca domestica; Helicoverpa armigera; Ostrinia furnacalis. (b).

Figure 15.

Expression level of PGRP gene in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms. Note: There is a significant difference in gene expression between the ' * ' representative and the control in the figure. (*: FDR < 0.05, **: FDR < 0.01, ***: FDR<0.001, ****: FDR<0.0001), There was no significant difference in gene expression between ' ns ' and control.

Figure 15.

Expression level of PGRP gene in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms. Note: There is a significant difference in gene expression between the ' * ' representative and the control in the figure. (*: FDR < 0.05, **: FDR < 0.01, ***: FDR<0.001, ****: FDR<0.0001), There was no significant difference in gene expression between ' ns ' and control.

Figure 16.

Expression level of βGRP gene in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms. Note: There is a significant difference in gene expression between the ' * ' representative and the control in the figure. (****: FDR<0.0001), There was no significant difference in gene expression between ' ns ' and control.

Figure 16.

Expression level of βGRP gene in S. frugiperda infected by pathogenic microorganisms. Note: There is a significant difference in gene expression between the ' * ' representative and the control in the figure. (****: FDR<0.0001), There was no significant difference in gene expression between ' ns ' and control.

Table 1.

qRT-PCR primer information.

Table 1.

qRT-PCR primer information.

| Primer |

Forward primer |

Reverse primer |

| PGRP-LE2 |

ATTTCGCACACTGCTACCGA |

TGGACTGAGAGTAGACGCCA |

| PGRP-LB |

CAAGGAAGACTGCTCAGCGA |

AGGCAGTTCCAGGACATTCG |

| PGRP-LB1 |

GCACGCGCTACATTTCAACA |

TTGAAGAGTGCGTCTCCTGG |

| PGRP-LB2 |

AGACCGCCTAATGGTTCGAC |

AGCCAAGCTTCACTCCAGTC |

| PGRP-L1 |

AGCAGCCAATGGAATCAGGA |

GAGAGCTGACTATGGGCCAC |

| PGRP-L2 |

GTCAGCTTGCTCCTGGTGAT |

ATCGTTCCGTTCCCGTTTGA |

| PGRP-L3 |

GAATTGCGCAGCTGAGATGG |

CAAGCTCGACACCCTTGTCT |

| PGRP-S1 |

AAATGGGGACTGTGGCGTAG |

CGTATACTTTGCCGTTGCCG |

| PGRP-S2 |

TTGTGTCGAGGATCGGTTGG |

CTCATACACTGTCCCCTGGC |

| βGRP1 |

GAAGTGCTCCAACCGAAGGA |

CGAATATGGTTTGGCCTGCG |

| βGRP2 |

CCCTGGAGAACCGGACTTTC |

AGGTGATGATCGGTGGGAGA |

| βGRP3 |

GTTAGCCGGAGTATTGGCGA |

AATCTCCGGCGGGCATTTTA |

| PRL18 |

GCCAAGACCGTTCTGCTGC |

CGCTCGTGTCCCTTAGTGC |

| PRL3 |

CCAAGGGTAAAGGATACAAAGGTG |

TCATTCACCGTTGCCCGT |

Table 2.

Evaluation statistics of transcriptome data of Spodoptera frugiperda larvae treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

Table 2.

Evaluation statistics of transcriptome data of Spodoptera frugiperda larvae treated with pathogenic microorganisms.

| SAmple |

Raw reads |

Raw bases |

Clean bases |

Error rate(%) |

Q20(%) |

Q30(%) |

GC pct(%) |

| PBS |

54529714 |

8180000000 |

7540000000 |

0.01 |

98.49 |

95.76 |

45.95 |

| Ec |

48893730 |

7330000000 |

6940000000 |

0.01 |

98.67 |

96.11 |

46.7 |

| Bt |

48788450 |

7320000000 |

6890000000 |

0.01 |

98.46 |

95.72 |

45.24 |

| SA |

51879208 |

7780000000 |

7460000000 |

0.01 |

98.67 |

96.2 |

45.3 |

| Bb |

46291118 |

6940000000 |

6720000000 |

0.01 |

98.56 |

95.96 |

45.15 |