1. Introduction

Prosthetic repair using flat meshes has been the standard approach for treating abdominal wall hernias. However, despite the dynamic nature of the abdominal wall —one of the most mobile areas of the human body— traditional prosthetic devices are static and require fixation, which can lead to complications. The static nature of these meshes often results in a suboptimal biological response, characterized by the formation of a rigid fibrotic scar. This scar tissue can cause shrinkage of the implant, potentially leading to de-coverage of the hernia defect. [

1,

2] The incorporation of the mesh into the body via a hard scar plate, as commonly seen with conventional flat meshes, is believed to be a major contributor to the discomfort and chronic pain reported by many patients following prosthetic repair. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] Recent research into the etiology of hernia disease, particularly focused on inguinal hernia, has highlighted tissue degeneration as a primary cause of visceral protrusions. [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] This understanding suggests that the regressive biological response typically elicited by conventional implants does not adequately address the underlying source of the disease. Instead, a therapeutic approach that promotes the regeneration of the compromised muscular tissue should be the focus of effective treatment strategies. Building on this premise, a novel approach for the surgical treatment of abdominal wall protrusions has been developed—the Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System. This proprietary 3D scaffold is designed with dynamic, responsive characteristics for the treatment of abdominal wall hernias, particularly but not exclusively inguinal hernias. Upon laparoscopic delivery into the abdominal cavity, the S&S Hernia System is inserted into the hernia opening where, thanks to a proprietary mechanism, expands to obliterate the defect while remaining firmly positioned within it without the need for fixation. The 3D scaffold is designed to move in harmony with the abdominal wall, compressing and releasing in sync with the musculature. In experimental studies using a porcine model, this innovative 3D scaffold has demonstrated regenerative potential. The biological response to the S&S device includes the formation of new blood vessels, elastic fibers, and well-perfused connective tissue, along with neomyogenesis, closely resembling the typical tissue composition of the abdominal region. Importantly, the device has also been shown to support the growth of newly formed nervous structures within its 3D architecture. This study aims to demonstrate the development and maturation of these newly ingrown nervous elements within the S&S device over short, medium, long, and extra-long-term periods in a cohort of pigs enrolled in an experimental trial.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental trial was conducted in accordance with the Animal Care Protocol for Experimental Surgery, as stipulated by the Italian Ministry of Health. The protocol received official approval under Decree No. 379/2021-PR, dated June 1st, 2021.

From February 2022 to July 2024, ten female pigs, each with a bilaterally purchased muscular defect in the lower abdomen, underwent laparoscopic implantation of two Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia Devices per animal. The S&S device is designed to achieve a dissection-free, atraumatic repair of various abdominal wall hernias, especially inguinal but also others such as incisional, femoral, Spigelian and obturator hernias.

The pigs, aged between 4 and 6 months, weighed between 40 and 60 kg. All laparoscopic procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The anesthesia regimen included premedication with zolazepam and tiletamine (6.3 mg/kg) and xylazine (2.3 mg/kg), induction with propofol (0.5 mg/kg), and maintenance with isoflurane in combination with pancuronium (0.07 mg/kg). Postoperatively, all animals received antibiotic prophylaxis with oxytetracycline (20 mg/kg/day) for three days.

Stenting & Shielding Hernia System: the structure

The S&S Hernia System used for the experimentation is made of medical grade propylene based Thermo-Polymer Elastomer (TPE) whose physical properties are showed in

Table 1.

The S&S device consists of two primary components: an eight-rayed structure assembled around a central mast, and a 3D oval shield measuring 10x8 cm with a central ring. The mast features a button-like arrangement at its distal end and two conic enlargements (stops) situated near the button. The device is initially configured as a cylindrical compound, with the oval shield attached by threading its central ring onto the mast (

Figure 1A & B). This design enables the device to be delivered through a 12 mm trocar channel into the abdominal cavity of the swine. Once the S&S device is positioned at the hernia defect, a metallic tube is used to push the oval shield, advancing the device into the previously procured muscular defect. As the shield is pushed beyond one or both conic enlargements on the mast, which act as stops, the cylindrical structure expands within the defect, forming a 3D scaffold that permanently obliterates the hernia opening. This final configuration secures the shield, preventing it from slipping backward, and anchors the 3D scaffold firmly inside the defect, with the shield covering and overlapping the muscular opening in direct contact with the abdominal viscera (

Figure 1C). The final dimension of the 3D scaffold used for the experiment is approximately 4.5 cm in diameter.

Follow Up Protocol

Out of the 10 pigs, 2 were sacrificed between 4 and 6 weeks postoperatively (short-term period), 2 between 3 and 4 months (midterm), 5 between 6 and 8 months (long-term), and 1 at 18 months (extra-long term). Each animal underwent scheduled ultrasound (

Figure 1D) and laparoscopic assessments at defined postoperative intervals to ensure the 3D scaffold remained properly positioned and to visually inspect for any adhesion formation between the shield and abdominal viscera.

At animal sacrifice all S&S devices were removed en bloc through a lower midline incision. The devices were then carefully scarified to remove the host’s native tissue, and subsequently bisected to allow for macroscopic evaluation of the tissue developed within the 3D scaffold. (

Figure 2) Following this, the explanted S&S devices were sent to the pathologist for detailed histological examination.

Histology and Histochemical Methods

The tissue specimens excised from core of the 3D scaffold of the S&S device were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for at least 12 hours and afterwards embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm thick) were cut and stored at room temperature until use. Routine histology (Hematoxilin–eosin staining, H&E) was carried out to assess the basic histomorphological aspect of the tissues. Other sections were also studied by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for neuron specific enolase (NSE), using an indirect immunoperoxidase method. Briefly, sections were rehydrated and blocked for endogenous peroxidase using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and nonspecific antibody binding using 2% normal goat serum. Monoclonal primary antibody NSE (NSE, LS-B14144, LSBio Lynnwood, Washington, USA) was applied at 1:100 dilution for 1 hr. Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector; Burlingame, CA - USA) was applied at 1:200 dilution for 30 min. Amplification with streptavidin peroxidase (Zymed; San Francisco, CA - USA) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were developed in 0.12% diaminobenzidine in Tris buffer for 20 min and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Histopathological Assessment

Histologic sections were evaluated by two pathologists in a blinded manner respect to timing of implant placement. Tissue specimens were studied by light microscopy at high power and the S&S device tissue interface was examined to conduct semi-quantitative histological analysis, assessing the width of the nerve area with IHC for NSE. The morphological aspects of the nervous structures were recognized using digital images of stained section. Nerve area of four non-overlapping fields at 50x magnification were measured. Images were acquired using a bright-light microscope, digital camera and image capture software (Leica DMLB microscope, a Nikon DS-Fi-1 digital camera, NIS Basic Research Nikon software).

Statistics

Nerve area was evaluated in 20 biopsies of the 3D scaffolds of the S&S devices excised at different periods post placement: 4 samples in the short term, 4 samples in the midterm, 10 samples in the long term and 2 samples in the extra-long term. A one-way ANOVA between 20 biopsies was conducted to compare ingrowth of nervous structures in 3D scaffolds respect to time in the short, mid, long and extra-long term. In addition, the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test was used to evidence significant differences between stages. SAS software (version 9.3. SAS) was used for the analyses.

3. Results

At the time of sacrifice, in all animals no adhesion to abdominal visceral were present. The tissue specimens excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device in the short term post-surgery (4–6 weeks postop.) evidenced multiple spots of nervous elements in progressive maturation which could be detected close to prosthetic tissue among the still developing connective tissue. (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6)

At the mid-term stage, 3–4 months after implantation, the development of nerve elements in the biopsy samples showed significant progress in both quantity and quality compared to the earlier postoperative period. A substantial number of nerve clusters were observed dispersed within well-organized connective tissue near the implant fibers. (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) The nerve structures at this stage demonstrated progressive evolution, with numerous axons in different stages of maturation, enveloped by a still in development myelin sheath.

At 6–8 months postoperatively (long-term), the quantity of nervous elements within the 3D implant fabric had significantly increased, with marked improvements in the quality of the neural components. At this stage, the nervous structures exhibited characteristics typical of mature nervous elements, fully developed in all components (

Figure 11).

High-magnification microphotographs revealed the distinct architecture of these nerves, displaying bundles of nerve fibers grouped into fascicles and encased by the perineurium that effectively isolated the entire nerve from the surrounding environment (

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). In the extra-long term, the nerves observed within the 3D scaffolds demonstrated a fully developed structural composition, with mature nerve axons securely enveloped in a well-formed, healthy, myelin sheath (

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18).

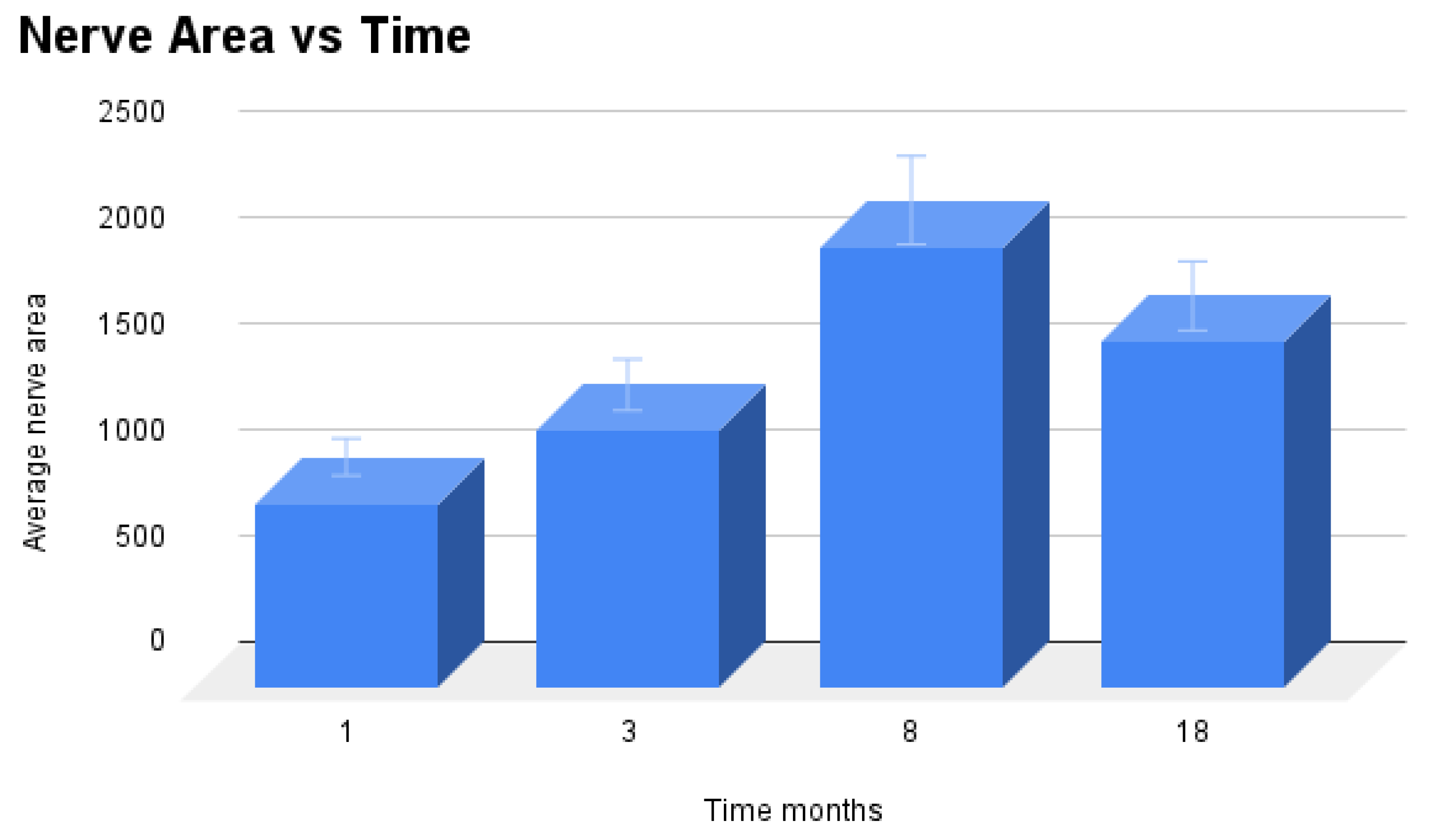

Statistical Analysis

Average area of nerve tissue of 20 specimens excised from the 3D scaffolds of the S&S device at different stages post implantation were compared with one-way Anova and post hoc Tukey test. Results showed statistically significant differences between stages (

Table 2) and, particularly, suggest that nerve ingrowth in a 3D scaffold for abdominal hernioplasty rises respect to time. (

Table 3)

Specifically, our results suggest that long-term and extra-long term nerve area media, are significantly greater than short term.

4. Discussion

Currently, prosthetic repair is widely regarded as the most effective method for treating abdominal wall hernias. [

14] The introduction of flat meshes made from biologically compatible materials has significantly advanced the outcomes of surgical therapy for this common disease. [

15] Today, a variety of implants composed of different alloplastic materials are available on the market, and numerous surgical techniques—both open and laparoscopic—are documented in the literature for inguinal hernia repair. This variety has led to a certain degree of confusion within the surgical community, likely due to the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the surgical approach and choice of device. Despite the undeniable advancements, the scientific community remains concerned about the persistent high incidence of complications associated with conventional prostheses. [

4,

16]

In the past decade, numerous scientific articles have explored the controversial aspects of the biological response to conventional hernia meshes that within few months after implantation develop a hard fibrotic plate. [

15,

16] This rigid and dynamically inert complex consisting of mesh and fibrotic scar struggles to accommodate the natural movements of the inguinal region. As a result, its irregular surface can rub against the mobile components of the abdominal musculature, leading to impaired mobility, discomfort, and, in some cases, pain. [

4,

5,

6] The low quality tissue that incorporates the fabric of conventional flat meshes is widely considered the primary cause of these issues. The ingrowth of stiff scar tissue within the mesh is commonly recognized as a major contributor to mesh shrinkage, often resulting in the loss of more than 30% of the implant’s original surface area. This significant reduction in size has been identified as a crucial predisposing factor for recurrence of the protrusion. [

1,

2]. Additionally, the use of flat, static implants necessitates fixation, which is inherently non-physiological. Point fixation to the muscular structures of the abdominal wall restricts natural movement and can lead to complications such as tissue tearing, bleeding, and hematoma formation. [

1,

3,

6] These issues have sparked ongoing debate among herniologists dedicated to finding new strategies for the treatment of abdominal wall hernias. It is important to note that the root causes of hernia protrusion disease have largely been neglected, with research into its genesis nearly abandoned. Only recently have a handful of studies revisited the pathogenesis of hernia disease. Among these are a series of scientific articles that explore the changes in the functional anatomy of the abdominal wall and their corresponding histological findings. These studies evidenced that degenerative tissue injuries, characterized by chronic compressive damage following the steady impact of the abdominal viscera against the abdominal wall, are the primary cause of hernia protrusion, particularly in the inguinal area [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

17,

18,

19]

Given these findings, it is evident that the focus of hernia repair should be on the regeneration of the degenerated structures affected by hernia protrusion, aligning with a pathogenetically informed approach. This stands in stark contrast to the traditional method of reinforcing the groin with a conventional flat mesh, which ultimately leads to the formation of a stiff fibrotic scar plaque. Based on this understanding, a novel device has been developed for the surgical treatment of abdominal wall protrusions: the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System. Made from medical grade polypropylene based thermoplastic elastomer (TPE), the S&S device can be laparoscopically delivered into the abdominal cavity and positioned within the muscular defect of the abdominal wall without the need for fixation, thus achieving an effective permanent obliteration. This newly developed device has been shown to achieve an improved biological response promoting the progressive development of new tissue that closely resembles the typical components of the abdominal wall, such as muscle, vessels and nerves. Given these findings, it is reasonable to suggest that the distinct biological response elicited by the device is due to its dynamic compliance with the movements of the abdominal wall, which contrasts with the static, passive nature of conventional flat meshes.

Notably, the proliferation of myocytes, which are essential for the dynamic function of the abdominal wall, has been observed within the scaffold of the S&S device. Overall, the regenerative features of the S&S Hernia System align with the primary goals of hernia repair: preventing further degeneration and promoting the reconstruction of damaged abdominal wall tissues. However, to fully validate these regenerative benefits, it is essential to demonstrate the ingrowth of specialized tissue elements crucial for effective muscular control—specifically, the nerves. This kind of regenerative feature is not new, since previous reports have mentioned the presence of nervous structures within another dynamic responsive device used for inguinal hernia repair, providing specific details or evidence. [

8,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] Getting forth with the discussion, the ultimate scope of this study is to outline the progressive stages of neural ingrowth within the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System. Histological analysis of tissue samples collected during the research revealed that nervous elements began to populate the 3D scaffold at multiple sites starting from 4 weeks post-implantation. Initially, these neurogenic clusters consisted of amorphous neural elements in the early stages of development. By the mid-term (approximately 3 to 4 months), there was a notable increase in both the quantity and quality of these nervous tissue components. During this phase, in addition to the increase in quantity, the nervous elements demonstrated progressive structural evolution, exhibiting characteristics more typical of mature neural structures. Histological staining revealed that these elements displayed intermediate developmental features: axons in transitional maturation stages, enveloped by myelin sheath still in stage of development. In the long-term post-implantation (6 to 8 months), the nervous elements observed within the 3D scaffold appeared to be fully mature, with well-developed axons encased in a thick, healthy myelin sheath. In the extra-long term stage, neural ingrowth exhibited as fully completed, with all components showing a consolidated stage of development.

The quantitative evaluation of nerve development during all stages of the investigation was statistically confirmed, further supporting the concept of a proactive response promoted by the S&S device. Beyond the quantity of nervous elements integrating with the implant fibers in the long term, the nerve structures exhibited characteristics consistent with normal nervous tissue.

Figure 1.

A: The Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System prepared for delivery into the abdominal cavity of the experimental swine, showing the device in its pre-implantation state. B: The S&S device in its deployed configuration. C: Two S&S Hernia devices positioned to obliterate a previously created defect in the lower abdomen of the experimental pig, with the redundant portion of the central mast already removed. D: Ultrasound scan of the S&S device six months after placement, clearly illustrating the 3D scaffold filled with newly ingrown tissue (red circle).

Figure 1.

A: The Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System prepared for delivery into the abdominal cavity of the experimental swine, showing the device in its pre-implantation state. B: The S&S device in its deployed configuration. C: Two S&S Hernia devices positioned to obliterate a previously created defect in the lower abdomen of the experimental pig, with the redundant portion of the central mast already removed. D: Ultrasound scan of the S&S device six months after placement, clearly illustrating the 3D scaffold filled with newly ingrown tissue (red circle).

Figure 2.

The S&S Hernia System excised from a pig three months after placement and cut in half to reveal clear evidence of viable fleshy tissue ingrowth within the 3D scaffold of the device (red circle). The fabric of the bisected 3D scaffold is clearly noticeable (*) while the shield is indicated with X.

Figure 2.

The S&S Hernia System excised from a pig three months after placement and cut in half to reveal clear evidence of viable fleshy tissue ingrowth within the 3D scaffold of the device (red circle). The fabric of the bisected 3D scaffold is clearly noticeable (*) while the shield is indicated with X.

Figure 3.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-op: Adjacent to a large artery (yellow arrows) near the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System (X), three nervous structures (blue circles) in the early stage of development are visible within a matrix of amorphous connective tissue. The 3D scaffold shows minimal inflammatory reaction. HE 50X.

Figure 3.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-op: Adjacent to a large artery (yellow arrows) near the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System (X), three nervous structures (blue circles) in the early stage of development are visible within a matrix of amorphous connective tissue. The 3D scaffold shows minimal inflammatory reaction. HE 50X.

Figure 4.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-op: Three nervous elements (blue circles) with developing axons stained brown, encased in an immature myelin sheath, are observed near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 4.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-op: Three nervous elements (blue circles) with developing axons stained brown, encased in an immature myelin sheath, are observed near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 5.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-op: Several nervous structures (blue arrows) in the initial ingrowth stage, with developing axons stained brown, are found close to the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 50X.

Figure 5.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-op: Several nervous structures (blue arrows) in the initial ingrowth stage, with developing axons stained brown, are found close to the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 50X.

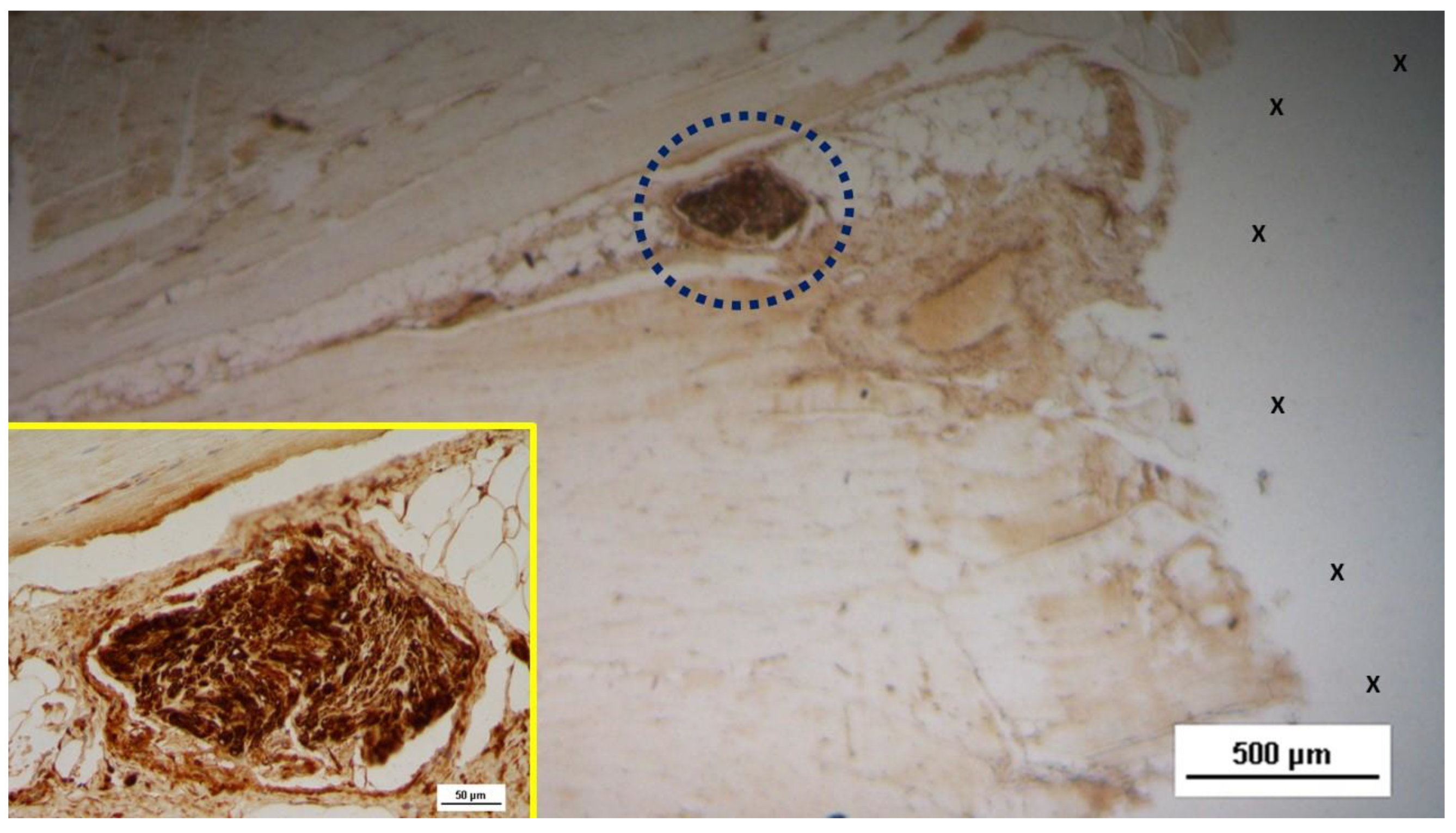

Figure 6.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-op: Two nervous structures (blue circles) in the early stage of development, stained brown, are located near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). In the upper right corner, a highly magnified image of the two neural structures (stained brown) from the main figure is displayed. NSE 50X (main image) and 200X (inset).

Figure 6.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-op: Two nervous structures (blue circles) in the early stage of development, stained brown, are located near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). In the upper right corner, a highly magnified image of the two neural structures (stained brown) from the main figure is displayed. NSE 50X (main image) and 200X (inset).

Figure 7.

Biopsy sample excised 3 months post-op: Within the fabric of the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System (X), amidst loose, well-hydrated connective tissue and numerous vascular elements, a large elongated nerve structure (blue circle) in an advanced stage of development is evident. The nerve axons are enveloped by a thick myelin sheath. The 3D scaffold exhibits no inflammatory reaction. HE 100X.

Figure 7.

Biopsy sample excised 3 months post-op: Within the fabric of the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System (X), amidst loose, well-hydrated connective tissue and numerous vascular elements, a large elongated nerve structure (blue circle) in an advanced stage of development is evident. The nerve axons are enveloped by a thick myelin sheath. The 3D scaffold exhibits no inflammatory reaction. HE 100X.

Figure 8.

Low magnification of biopsy specimen excised 3 months post-op: Among several nervous structures, particularly in the upper right corner, an elongated nerve element (blue circle) in an advanced stage of development with brown-stained axons is seen, enveloped by a thick myelin sheath near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 25X.

Figure 8.

Low magnification of biopsy specimen excised 3 months post-op: Among several nervous structures, particularly in the upper right corner, an elongated nerve element (blue circle) in an advanced stage of development with brown-stained axons is seen, enveloped by a thick myelin sheath near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 25X.

Figure 9.

Biopsy excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System 3 months post-op: An elongated nerve element with an axon in an advanced stage of development (stained brown) and encased in a well-formed myelin sheath (blue circle) is observed in close proximity to a large artery (Y). NSE 50X.

Figure 9.

Biopsy excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S Hernia System 3 months post-op: An elongated nerve element with an axon in an advanced stage of development (stained brown) and encased in a well-formed myelin sheath (blue circle) is observed in close proximity to a large artery (Y). NSE 50X.

Figure 10.

Biopsy specimen excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 3 months post-op: Two large nervous structures (blue circles) in an advanced stage of development, with numerous axons stained brown, are found near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 25X.

Figure 10.

Biopsy specimen excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 3 months post-op: Two large nervous structures (blue circles) in an advanced stage of development, with numerous axons stained brown, are found near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 25X.

Figure 11.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-implantation: In this low magnification microphotograph, two nervous elements (blue circles) are visible between the fabric of the S&S Hernia System (X) and near large, mature arterial structures. HE 25X.

Figure 11.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-implantation: In this low magnification microphotograph, two nervous elements (blue circles) are visible between the fabric of the S&S Hernia System (X) and near large, mature arterial structures. HE 25X.

Figure 12.

Biopsy specimen excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-op: A large nervous structure (blue circle) with well-developed axons (stained brown) encased in a thick myelin sheath is shown in close proximity to the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 100X.

Figure 12.

Biopsy specimen excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-op: A large nervous structure (blue circle) with well-developed axons (stained brown) encased in a thick myelin sheath is shown in close proximity to the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 100X.

Figure 13.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-implantation: A nervous structure (blue circle) with mature axons (stained brown) enveloped in a healthy myelin sheath is highlighted near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 100X.

Figure 13.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-implantation: A nervous structure (blue circle) with mature axons (stained brown) enveloped in a healthy myelin sheath is highlighted near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. NSE 100X.

Figure 14.

Tissue specimen taken from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-op: A large nervous structure (blue circle) with well-developed axons (stained brown) and surrounded by a myelin sheath is depicted near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). In the upper right corner, a highly magnified image of the same nervous element shows the mature appearance of the nerve axons (stained brown). NSE 25X (main image) and 200X (inset).

Figure 14.

Tissue specimen taken from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 6 months post-op: A large nervous structure (blue circle) with well-developed axons (stained brown) and surrounded by a myelin sheath is depicted near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). In the upper right corner, a highly magnified image of the same nervous element shows the mature appearance of the nerve axons (stained brown). NSE 25X (main image) and 200X (inset).

Figure 15.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months post-implantation: Close to the fabric of the S&S Hernia System (X), among newly ingrown tissue, a nervous element (blue circle) is detectable. HE 50X.

Figure 15.

Biopsy sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months post-implantation: Close to the fabric of the S&S Hernia System (X), among newly ingrown tissue, a nervous element (blue circle) is detectable. HE 50X.

Figure 16.

Biopsy specimen excised 18 months post-implantation: An elongated nervous structure (blue circle) with thick, mature axons (stained brown) is clearly evident near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 25X.

Figure 16.

Biopsy specimen excised 18 months post-implantation: An elongated nervous structure (blue circle) with thick, mature axons (stained brown) is clearly evident near the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 25X.

Figure 17.

Biopsy sample removed from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months post-surgery: An elongated nervous element (blue circle) enveloped by a myelin sheath is highlighted near the structure of the S&S device (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 17.

Biopsy sample removed from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months post-surgery: An elongated nervous element (blue circle) enveloped by a myelin sheath is highlighted near the structure of the S&S device (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 18.

Tissue sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months after implantation: The mature axons (stained brown) of two nervous elements, encased in a myelin sheath (blue arrows), are observed near a convoluted arterial structure (yellow circle) in close proximity to the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 50X.

Figure 18.

Tissue sample excised from the 3D scaffold of the S&S device 18 months after implantation: The mature axons (stained brown) of two nervous elements, encased in a myelin sheath (blue arrows), are observed near a convoluted arterial structure (yellow circle) in close proximity to the fabric of the S&S scaffold (X). NSE 50X.

Table 1.

Physical properties of the TPE material used for the injection molding of the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System.

Table 1.

Physical properties of the TPE material used for the injection molding of the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System.

| TPE mechanical properties |

Value |

Unit |

Test Standard |

| ISO Data |

| Tensile Strength |

16 |

MPa |

ISO 37 |

| Strain at break |

650 |

% |

ISO 37 |

| Compression set at 70 °C, 24h |

54 |

% |

ISO 815 |

| Compression set at 100 °C, 24h |

69 |

% |

ISO 815 |

| Tear strength |

46 |

kN/m |

ISO 34-1 |

| Shore A hardness |

89 |

- |

ISO 7619-1 |

| Density |

890 |

kg/m³ |

ISO 1183 |

Table 2.

Nerve area in biopsy samples (in µm2).

Table 2.

Nerve area in biopsy samples (in µm2).

| Period |

Short Term |

Mid Term |

Long Term |

Extra-Long Term |

| Time (weeks/months) |

3 - 5 weeks |

3 – 4 months |

6 – 8 months |

18 months |

| Media Nerve area |

872 |

1213 |

2084,333 |

1632,5 |

| SD Nerve area |

232,3374 |

191,2869 |

321,0592 |

133,6432 |

Table 3.

Diagram showing the amount of nerve ingrowth within the 3D dynamic implant at different stages post-implantation.

Table 3.

Diagram showing the amount of nerve ingrowth within the 3D dynamic implant at different stages post-implantation.