1. Introduction

Depressed fractures of the frontal bone, often resulting from high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle accidents or assaults, pose significant challenges in management due to their proximity to critical structures, including the brain and orbits. These fractures account for approximately 5% to 15% of all maxillofacial injuries, with isolated anterior table fractures comprising a notable subset of frontal sinus fractures (Srinivasa et al., 2022; Kwak et al., 2022). The management of these fractures is crucial, as inadequate treatment can lead to severe complications, including aesthetic deformities, chronic sinusitis, and even life-threatening conditions such as meningitis or brain abscesses (Kim et al., 2016; Sathyanarayanan et al., 2018).

The surgical approach to managing depressed frontal bone fractures has evolved significantly over the years. Traditionally, techniques such as total exenteration of the frontal sinus were common, but these often resulted in undesirable cosmetic outcomes (Lee et al., 2014). Modern management strategies favor minimally invasive techniques, such as the subbrow approach, which not only facilitate effective reduction of the fracture but also minimize visible scarring (Lee et al., 2014; Meyyappan et al., 2019). The use of advanced imaging modalities, particularly computed tomography (CT), has enhanced the precision of surgical planning, allowing for better assessment of fracture displacement and associated injuries (Gerding et al., 2014).

Complications arising from depressed frontal bone fractures can be multifaceted. Immediate complications may include hematomas and neurological deficits, while long-term issues often involve aesthetic concerns due to contour deformities (Marinheiro et al., 2014; Jeyaraj, 2019). The choice of reconstruction material, whether titanium mesh or autogenous grafts, plays a critical role in the outcome (SHALTOUT & Ali, 2018; Sakat et al., 2016). Studies indicate that the use of titanium mesh can effectively restore the contour of the skull while minimizing the risk of infection and other complications (Meyyappan et al., 2019; Sakat et al., 2016). Furthermore, the timing of surgical intervention is crucial; early intervention is associated with better functional and aesthetic outcomes (Ho et al., 2022)..

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at a tertiary care center to evaluate the management of frontal bone fractures over 28 months, from January 2022 to April 2024, with institutional review board approval.

Patient Selection

Patients with depressed frontal bone fractures treated during this period were included if they had complete medical records and a minimum of 2 months follow-up. Exclusions applied to those with incomplete records or insufficient follow-up.

Data Collection

Data extracted included demographics, injury mechanisms, clinical presentations, radiological findings, management approaches (conservative or surgical), and postoperative outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized demographics and outcomes, while associations between fracture characteristics and CSF leaks were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher's exact tests, with significance set at p < 0.05. A comprehensive literature search was also performed for relevant studies on frontal bone fractures. Data extraction was conducted by two reviewers with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Methodological quality was assessed using established scales.

3. Results

Frequency of Frontal Bone Fractures

The study examined 47 patients with frontal bone fractures, revealing a predominance of males (89.4%) who presented early (78.7%). The primary cause was road traffic accidents (44.7%), with fractures mostly occurring on the right side (48.9%) and a high incidence of open fractures (80.9%). Neurologically, 57.4% exhibited mild Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores. Surgical intervention was required in 53.2% of cases, leading to a 6.4% mortality rate. Cosmetic satisfaction was reported by 57.4%, though 51.1% experienced a lack of forehead symmetry. Complications included frontal bone defects and infections (see Table 1).

Age Group Relationships

The analysis explored various relationships across age groups, including gender, time of presentation, injury mechanisms, fracture characteristics, neurological status, management options, cosmetic satisfaction, and complications. Males made up 89.4% of the study sample, with their representation increasing with age. Most patients (78.7%) sought treatment early, and significant correlations emerged between age and injury mechanisms, particularly road traffic accidents among older patients. Right-sided fractures predominated, with open fractures more common in older individuals. Frontal air sinus involvement peaked in the 21-45 age group (65.2%). Younger patients tended to undergo surgical management, while older patients often received conservative treatment. Although younger patients reported higher cosmetic satisfaction, no significant differences were observed in scar disfigurement or forehead symmetry. Behavioral changes were notably associated with older age, while headaches were more prevalent in older groups (p = 0.007). These trends underscore the impact of age on injury and treatment outcomes.

Gender Relationships

The data indicated that 78.7% of participants presented early (within 24 hours), with no significant gender differences (males 76.2%, females 100%; χ² (1) = 1.512, p = 0.219). Road traffic accidents were the leading cause of injury (44.7%), affecting more females (60.0%) than males (42.9%), though this difference was not statistically significant (χ² (3) = 2.419, p = 0.490). Right-sided fractures were common (48.9%), with 80% of females and 45.2% of males having this type, also not significant (χ² (3) = 3.826, p = 0.281). However, there was a significant association between gender and fracture type, with males more likely to suffer open fractures (χ² (1) = 6.031, p = 0.014). Neurological status revealed that all females had mild GCS scores, whereas males varied, though this difference was not significant (χ² (2) = 4.145, p = 0.126). Management options showed no significant differences in surgical treatment rates or cosmetic satisfaction between genders, suggesting that gender may not be a strong predictor in these areas.

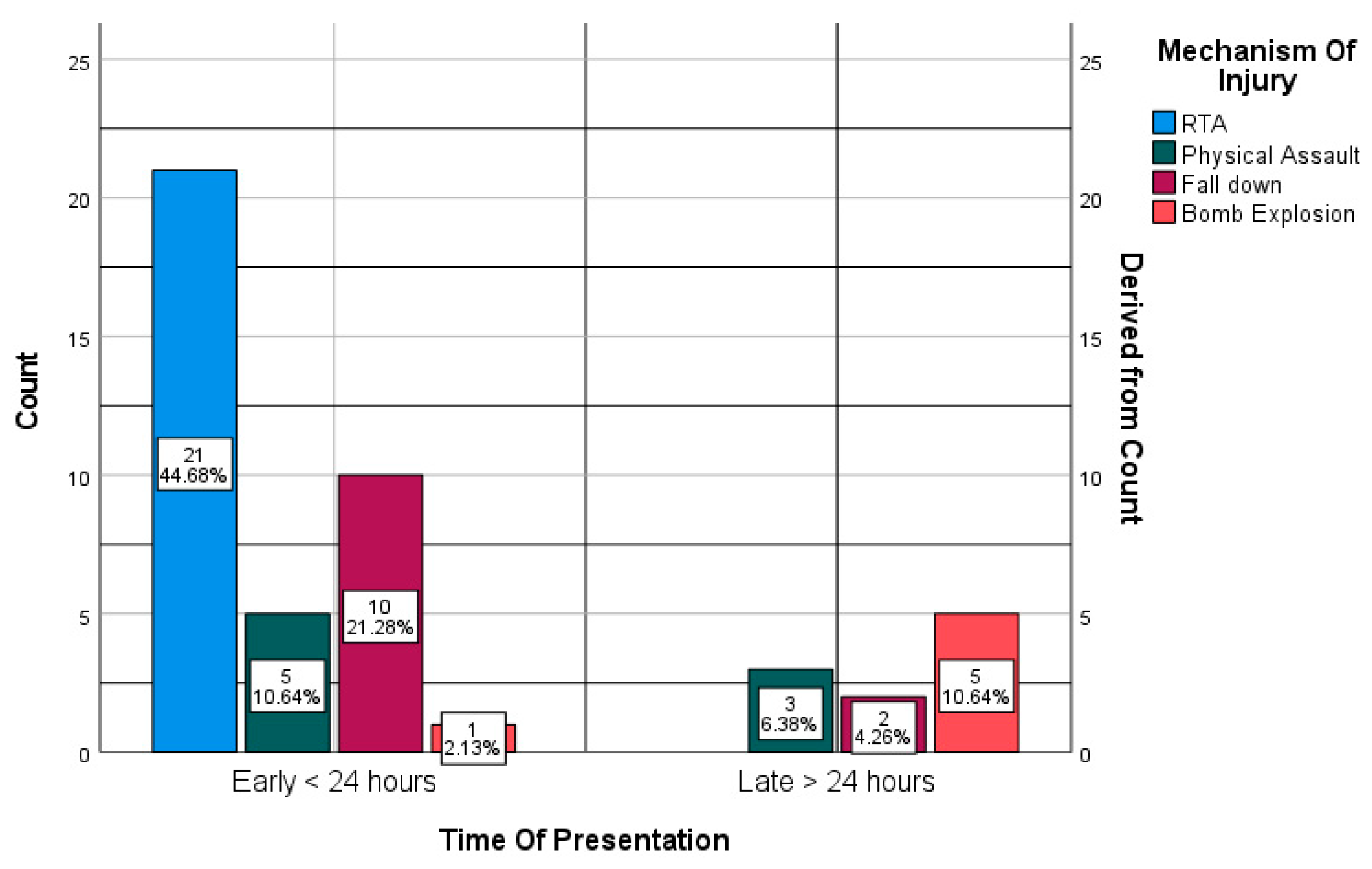

Mechanism of Injury Relationships

Patients presenting early (<24 hours) were more likely to have injuries from road traffic accidents (56.8%) and falls (27.0%), while late presenters (>24 hours) experienced more injuries from bomb explosions (50.0%) and physical assaults (30.0%). This indicated a significant relationship (χ²(3) = 20.880, p < 0.001) with a moderate positive correlation (Pearson's R = 0.537). However, no significant associations were found between time of presentation and fracture side, type, neurological status, or other outcomes, suggesting weak correlations across these factors. Frontal air sinus involvement was not significantly related to presentation time (χ²(1) = 1.205, p = 0.272). Bomb explosions were significantly associated with headaches (p = 0.001), but other injury mechanisms did not correlate significantly with complications or mortality rates.

Side of Frontal Bone Fracture Relationships

Right-sided fractures were predominantly open (73.9%) compared to left-sided fractures (93.3% open). No significant association was found between fracture side and type (p = 0.206), nor with neurological status (p = 0.466). However, a significant association existed between fracture side and site (p < 0.001), while frontal air sinus involvement did not show significant association (p = 0.090). Management options (p = 0.124), cosmetic satisfaction (p = 0.162), scar disfigurement (p = 0.385), and forehead symmetry (p = 0.409) also showed no significant associations. Significant links were noted for persistent CSF leaks (p = 0.035) and convulsions (p = 0.016), but not for behavioral changes, infection, headaches, death, or complications.

Type of Fracture Relationships

The analysis found no significant association between fracture type (open vs. closed) and neurological status (p = 0.781), with similar GCS scores across both types. However, a significant relationship emerged between fracture type and fracture site (p = 0.018), with open fractures more common in the frontal air sinus and para-midline areas. Open fractures were more likely to involve the frontal air sinus (p = 0.024) and were strongly linked to scar disfigurement (p < 0.001). However, no significant associations were found with management options, cosmetic satisfaction, persistent CSF leaks, or other outcomes like convulsions and infections.

Neurological Status (GCS Score) Relationships

The data revealed that 57.4% of patients had mild GCS scores, with no significant association between GCS and fracture site (p = 0.281). However, significant relationships were found between GCS scores and frontal air sinus involvement, with higher involvement in patients with moderate (46.7%) and severe (100%) scores (p = 0.022). GCS scores also correlated with the likelihood of intracranial injuries (p = 0.008), with mild scores showing lower injury rates. Cosmetic satisfaction was linked to GCS scores (p = 0.027), while no significant associations were found for management options, scar disfigurement, persistent CSF leaks, or headaches. Notably, GCS scores significantly correlated with mortality rates (p = 0.004), with no deaths among patients with mild scores.

Frontal Bone Site Relationships

Significant associations were found between the site of frontal bone fractures and frontal air sinus involvement, with 95.2% of sinus fractures located in the frontal air sinus (p < 0.001). Specific involvement also showed a significant relationship (p < 0.001). However, no significant associations were found between fracture site and intracranial injuries (p = 0.103), management options (p = 0.901), or cosmetic satisfaction (p = 0.666). Midline and frontal sinus fractures had a higher likelihood of disfiguring scars (p = 0.117) but did not significantly affect cosmetic symmetry (p = 0.152). Para-midline fractures were more prone to infections (22.7%), and fractures involving the frontal air sinus significantly associated with headaches (70%, p < 0.001).

Frontal Air Sinus Involvement Relationships

Frontal air sinus involvement was significantly related to higher rates of headaches (66.7% vs. 11.5%, p < 0.001) and behavioral changes (23.8% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.041). However, it showed no significant relationship with associated intracranial injuries (p = 0.149), management options (p = 0.920), or cosmetic satisfaction (p = 0.528). There was a trend toward more disfiguring scars with frontal air sinus involvement (57.1% vs. 38.5%, p = 0.119), though this did not reach significance. Interestingly, frontal air sinus involvement correlated inversely with infection (0% vs. 19.2%, p = 0.034).

Frontal Air Sinus Fracture Site Relationships

Frontal air sinus involvement linked to higher headache rates (66.7% vs. 11.5%, p < 0.001) but showed no significant association with intracranial injuries (p = 0.149) or management options (p = 0.920). Fractures limited to the inner plate had the highest dissatisfaction rates (100% unsatisfied), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.115). Disfiguring scars were most common in fractures involving both plates (61.1%), but this relationship was not significant (p = 0.117). Inner plate fractures also showed a tendency toward asymmetrical foreheads (100%), yet this did not reach significance (p = 0.148). Persistent CSF leaks, frontal bone defects, convulsions, and behavioral changes showed no significant associations with fracture site.

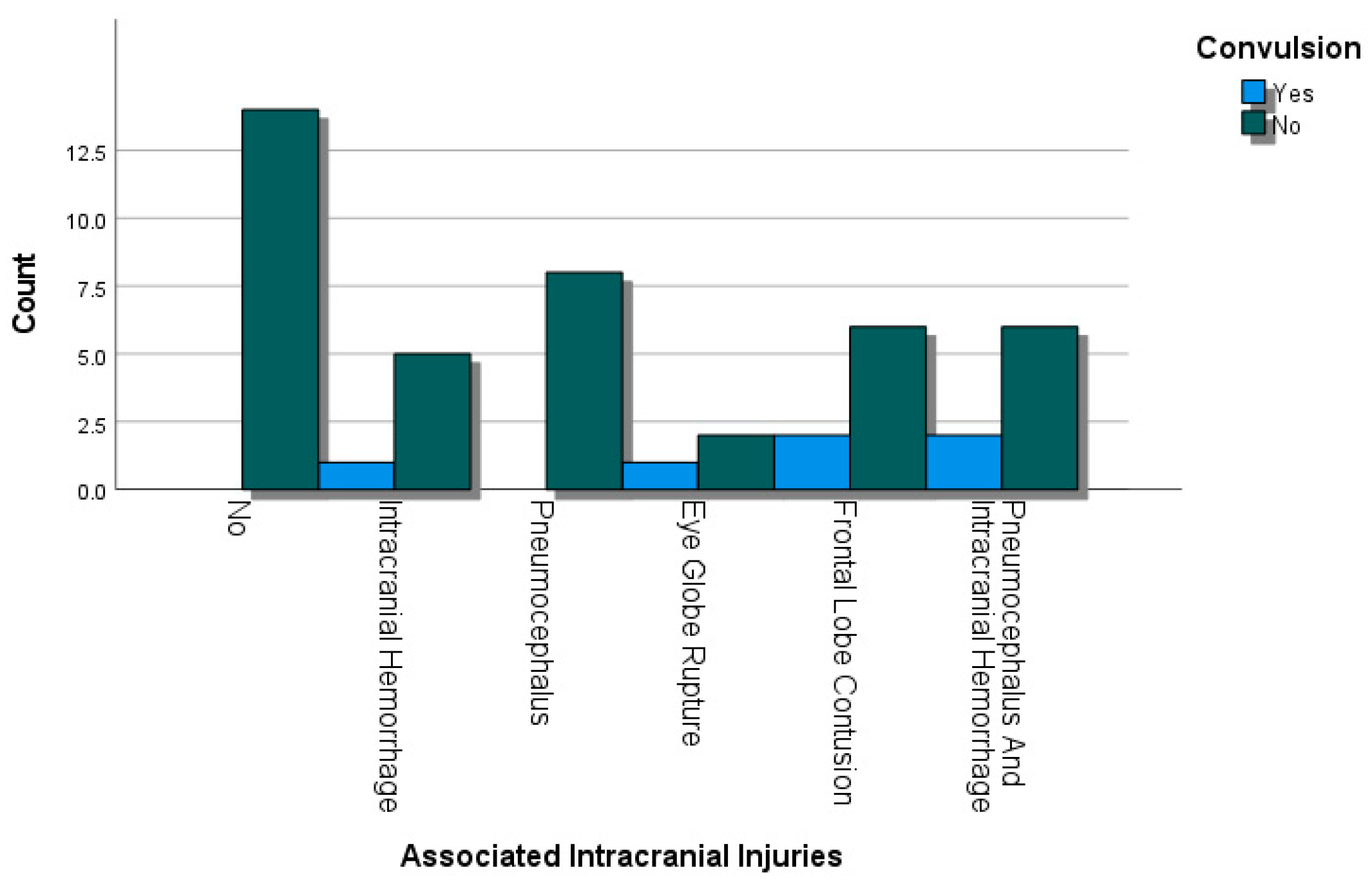

Associated Intracranial Injuries Relationships

The findings indicated that associated intracranial injuries did not significantly influence management options for frontal sinus fractures (p = 0.901) or cosmetic satisfaction (p = 0.532). No significant correlations were found with scar disfigurement (p = 0.480) or persistent CSF leaks (p = 0.418). A moderate negative correlation existed between intracranial injuries and frontal bone defects (p = 0.234) and convulsions, although the latter was not statistically significant (p = 0.253). Notably, significant associations were observed for behavioral changes (p = 0.008), particularly in cases with pneumocephalus or hemorrhage.

Management Options Relationships

The data showed no significant impact of management options on cosmetic satisfaction (68.2% conservative vs. 48% surgical, p = 0.163) or scar disfigurement (31.8% vs. 60%, p = 0.152). Forehead symmetry rates were similar (p = 0.191). Conservative management had a 4.5% rate of persistent CSF leaks, while surgical cases reported none (p = 0.281). However, surgical management was significantly linked to frontal bone defects (36% vs. 0%, p = 0.002). No significant associations were found regarding convulsions, behavioral changes, infection rates, headaches, or mortality, indicating that management approaches primarily affect frontal bone defects.

Cosmetic Satisfaction Relationships

The study found a significant relationship between scar disfigurement and cosmetic satisfaction, with 70% of patients with disfiguring scars reporting dissatisfaction compared to 15% without (p = 0.015). A strong positive link existed between cosmetic satisfaction and forehead symmetry, with 77.8% of symmetrical patients satisfied (p < 0.001). No significant associations were found between cosmetic satisfaction and persistent CSF leaks (p = 0.384) or infections (p = 0.404). Patients with frontal bone defects were more likely to be dissatisfied (35% vs. 7.4%, p = 0.017). Convulsions and behavioral changes also correlated with dissatisfaction (25% vs. 3.7%, p = 0.031), highlighting the impact of scar disfigurement and forehead symmetry on overall satisfaction.

Persistent CSF Leak Relationships

The data indicated no significant association between persistent CSF leaks and frontal bone defects (p = 0.623), convulsions, or behavioral changes (p = 0.699). None of the patients with a persistent CSF leak had infections, while 10.9% without leaks did, showing a weak relationship. Although all patients with a persistent CSF leak reported headaches, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.104). Furthermore, all individuals with leaks survived, and complications occurred similarly in both groups without significant differences.

Frontal Bone Defect Relationships

Analysis revealed no significant association between frontal bone defects and behavioral or personality changes, infections, headaches, death, or complications. Chi-square tests and correlation measures consistently indicated that frontal bone defects did not increase the risk of these outcomes.

Convulsion Relationships

The data indicated no significant associations between convulsions and behavioral changes, infections, headaches, death, or complications. Specifically, 0% of those with convulsions reported behavioral changes, and while 16.7% had infections, this was not significantly different from the 9.8% in those without convulsions. Although 66.7% of patients with convulsions reported headaches, this also lacked significance.

Behavioral and Personality Changes Relationships

The data showed no significant link between behavioral or personality changes and infections, with 0% of those with changes having infections. However, all participants with changes reported headaches, indicating a significant positive relationship (p < 0.001). There was no association with death, as none of those with changes died, and complications were similar between groups.

Infection Relationships

The data showed no significant relationship between infection and headaches, with none of the 5 infected participants reporting headaches. There was also no link between infection and death, with 20% of infected individuals dying compared to 4.8% without infections (p = 0.188). Additionally, no significant association existed between infection and complications, with 40% of infected participants experiencing complications versus 57.1% without infections.

Headache Relationships

Finally, the data indicated no significant relationship between headaches and death, as none of the 17 individuals with headaches died compared to 10% of those without headaches. Similarly, there was no significant association between headaches and complications, with 70.6% of those with headaches experiencing complications versus 46.7% without. Overall, headaches do not predict death or complications in this study.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

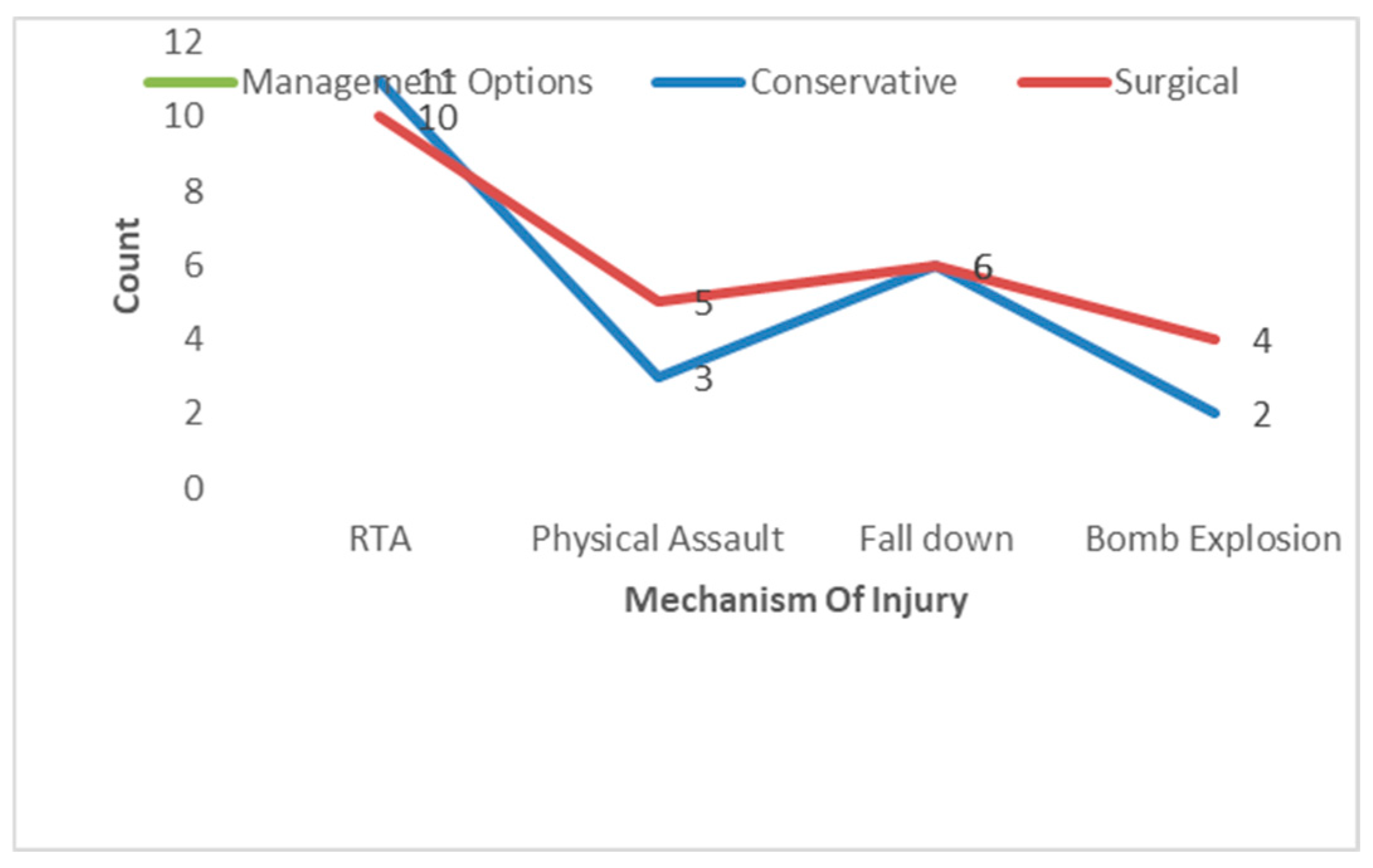

Figure 1.

The Relationship Between Mechanism Of Injury and Management Options.

Figure 1.

The Relationship Between Mechanism Of Injury and Management Options.

Table 1.

Relationships between various factors and frontal bone fracture highlighting frequency (number of cases )and percentages for this factors .

Table 1.

Relationships between various factors and frontal bone fracture highlighting frequency (number of cases )and percentages for this factors .

| Category |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

| Total Patients |

47 |

100.0 |

| Male Patients |

42 |

89.4 |

| Presented within 24 hours |

37 |

78.7 |

| Mechanism of Injury |

|

|

| - Road Traffic Accidents |

21 |

44.7 |

| - Falls |

12 |

25.5 |

| - Physical Assault |

8 |

17.0 |

| Fracture Side |

|

|

| - Right Side |

23 |

48.9 |

| - Left Side |

15 |

31.9 |

| Fracture Type |

|

|

| - Open Fractures |

38 |

80.9 |

| - Frontal Air Sinus Involvement |

20 |

42.6 |

| - Paramedian Region |

22 |

46.8 |

| Neurological Status |

|

|

| - Mild GCS |

27 |

57.4 |

| - Moderate GCS |

15 |

31.9 |

| - Severe GCS |

5 |

10.6 |

| Surgical Management |

|

|

| - Surgical Intervention |

25 |

53.2 |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction |

|

|

| - Satisfied |

27 |

57.4 |

| - Disfiguring Scars |

22 |

46.8 |

| - Forehead Symmetry Issues |

24 |

51.1 |

| Complications |

|

|

| - Frontal Bone Defects |

9 |

19.1 |

| - Convulsions |

6 |

12.8 |

| - Behavioral Changes |

6 |

12.8 |

| - Infections |

5 |

10.6 |

| Mortality Rate |

|

|

| - Total Mortality |

3 |

6.4 |

Figure 2.

The Relationship Between Mechanism Of Injury and Management Options.

Figure 2.

The Relationship Between Mechanism Of Injury and Management Options.

Table 2.

Relationships between various factors and frontal bone fracture highlighting p-values and percentages for this factors .

Table 2.

Relationships between various factors and frontal bone fracture highlighting p-values and percentages for this factors .

| Relationship |

P-Value |

Percentage |

| Age Groups and Gender |

N/A |

Males: 89.4%, Females: 10.6% |

| Age Groups and Time of Presentation |

0.130 |

Early: 78.7%, Late: 21.3% |

| Age Groups and Mechanism of Injury |

0.016 |

RTA: 52.2%, Falls: 75.0% |

| Age Groups and Type of Fracture |

0.008 |

Open: 80.9%, Closed: 19.1% |

| Age Groups and Neurological Status (GCS Score) |

N/A |

Mild: 57.4%, Moderate: 31.9%, Severe: 10.6% |

| Age Groups and Site of Frontal Bone Fracture |

0.018 |

Right Side: 48.9%, Left Side: 31.9% |

| Age Groups and Frontal Air Sinus Involvement |

0.003 |

Involvement: 44.7% |

| Age Groups and Headache |

0.007 |

Headaches: 36.2% |

| Age Groups and Behavioral Changes |

N/A |

Changes: 12.8% |

| Age Groups and Death |

N/A |

Deaths: 6.4% |

| Age Groups and Complications |

N/A |

Complications: 55.3% |

| Gender and Time of Presentation |

0.219 |

Early: Males 76.2%, Females 100% |

| |

|

Late: Males 23.8%, Females 0% |

| Gender and Mechanism of Injury |

0.490 |

RTA: Males 42.9%, Females 60.0% |

| |

|

Falls: Males 23.8%, Females 40.0% |

| |

|

Physical Assaults: Males 19.0%, Females 0% |

| |

|

Bomb Explosions: Males 14.3%, Females 0% |

| Gender and Side of Fracture |

0.281 |

Right Side: Males 45.2%, Females 80.0% |

| |

|

Left Side: Males 35.7%, Females 0% |

| |

|

Both Sides: Males 9.5%, Females 20.0% |

| Gender and Type of Fracture |

0.014 |

Open: Males 85.7%, Females 40.0% |

| |

|

Closed: Males 14.3%, Females 60.0% |

| Gender and Neurological Status (GCS Score) |

0.126 |

Mild: Males 52.4%, Females 100% |

| |

|

Moderate: Males 35.7%, Females 0% |

| |

|

Severe: Males 11.9%, Females 0% |

| Gender and Site of Frontal Bone Fracture |

0.275 |

Para-Midline: Males ~42.9%, Females ~80% |

| |

|

Frontal Air Sinus: Males ~45.2%, Females ~20% |

| Gender and Frontal Air Sinus Involvement |

0.240 |

Involvement: Males ~47.6%, Females ~20% |

| Gender and Management Options |

0.747 |

Surgical: Males 52.4%, Females 60% |

| |

|

Conservative: Males 47.6%, Females 40% |

| Gender and Cosmetic Satisfaction |

0.281 |

Satisfied: Males 54.8%, Females 80% |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: Males 45.2%, Females 20% |

| Gender and Scar Disfigurement |

0.270 |

Disfiguring Scar: Males ~50%, Females ~20% |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring Scar: Males ~35.7%, Females ~40% |

| Gender and Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome |

0.142 |

Symmetrical: Males ~45.2%, Females ~80% |

| Gender and Persistent CSF Leak |

0.727 |

Leak Present: Males ~2.4%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.250 |

Defect Present: Males ~21.4%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Convulsion |

0.366 |

Convulsions: Males ~14.3%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Behavioral and Personality Changes |

0.366 |

Changes Present: Males ~14.3%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Infection |

0.414 |

Infections Present: Males ~11.9%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Headache |

0.426 |

Headaches Present: Males ~38.1%, Females ~20% |

| Gender and Death |

0.537 |

Deaths: Males ~7.1%, Females ~0% |

| Gender and Complications |

0.093 |

Complications Present: Males ~59.5%, Females ~20% |

| |

|

|

| Management Options and Persistent CSF Leak |

0.281 |

Conservative: 9.1% leak present |

| |

|

Surgical: 4.0% leak present |

| Management Options and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.350 |

Conservative: 18.2% defect present |

| |

|

Surgical: 12.0% defect present |

| Management Options and Convulsion |

0.417 |

Conservative: 4.5% convulsions |

| |

|

Surgical: 0% convulsions |

| Management Options and Behavioral Changes |

0.590 |

Conservative: 9.1% changes present |

| |

|

Surgical: 0% changes present |

| Management Options and Infection |

0.780 |

Conservative: 4.5% infection present |

| |

|

Surgical: 0% infection present |

| Management Options and Headache |

0.344 |

Conservative: 22.7% headaches present |

| |

|

Surgical: 20.0% headaches present |

| Management Options and Death |

0.627 |

Conservative: 6.8% deaths |

| |

|

Surgical: 4.0% deaths |

| Management Options and Complications |

0.512 |

Conservative: 54.5% complications present |

| |

|

Surgical: 60.0% complications present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Scar Disfigurement |

0.236 |

Satisfied: 35.0% disfiguring scars |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 60.0% disfiguring scars |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome |

0.405 |

Satisfied: 49.0% symmetry outcome |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 40.0% symmetry outcome |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Persistent CSF Leak |

0.560 |

Satisfied: 2.5% leak present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 1.5% leak present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.486 |

Satisfied: 10.0% defect present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 8.0% defect present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Convulsion |

0.721 |

Satisfied: 2.5% convulsions |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 1.0% convulsions |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Behavioral Changes |

0.294 |

Satisfied: 5.0% changes present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 3.5% changes present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Infection |

0.867 |

Satisfied: 1.0% infections present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 1.0% infections present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Headache |

0.424 |

Satisfied: 15.0% headaches present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 12.0% headaches present |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Death |

0.980 |

Satisfied: 3.0% deaths |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 2.0% deaths |

| Cosmetic Satisfaction and Complications |

0.556 |

Satisfied: 50.0% complications present |

| |

|

Not Satisfied: 55.0% complications present |

| Scar Disfigurement and Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome |

0.145 |

Disfiguring: 30.0% symmetry |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 60.0% symmetry |

| Scar Disfigurement and Persistent CSF Leak |

0.070 |

Disfiguring: 5.0% leak present |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 1.0% leak present |

| Scar Disfigurement and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.320 |

Disfiguring: 15.0% defect present |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 10.0% defect present |

| Scar Disfigurement and Convulsion |

0.540 |

Disfiguring: 2.0% convulsions |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 1.0% convulsions |

| Scar Disfigurement and Behavioral Changes |

0.780 |

Disfiguring: 3.0% changes present |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 2.0% changes present |

| Scar Disfigurement and Infection |

0.910 |

Disfiguring: 0% infections present |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 1.0% infections present |

| Scar Disfigurement and Headache |

0.370 |

Disfiguring: 10.0% headaches present |

| Non-Disfiguring: 8.0% headaches present |

|

Scar Disfigurement and Death |

| |

0.550 |

Disfiguring: 1.0% deaths |

| |

|

|

| Scar Disfigurement and Complications |

0.220 |

Disfiguring: 55.0% complications present |

| |

|

Non-Disfiguring: 45.0% complications present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Persistent CSF Leak |

0.420 |

Symmetrical: 2.0% leak present |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 1.5% leak present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.380 |

Symmetrical: 10.0% defect present |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 5.0% defect present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Convulsion |

0.560 |

Symmetrical: 1.5% convulsions |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 1.0% convulsions |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Behavioral Changes |

0.310 |

Symmetrical: 2.0% changes present |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 1.0% changes present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Infection |

0.430 |

Symmetrical: 0% infections present |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 1.0% infections present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Headache |

0.250 |

Symmetrical: 8.0% headaches present |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 5.0% headaches present |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Death |

0.930 |

Symmetrical: 1.0% deaths |

| |

|

Asymmetrical: 2.0% deaths |

| Cosmetic Forehead Symmetry Outcome and Complications |

0.200 |

Symmetrical: 40.0% complications present |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Frontal Bone Defect |

0.620 |

Leak Present: 5.0% defects |

| |

|

No Leak: 3.0% defects |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Convulsion |

0.310 |

Leak Present: 1.0% convulsions |

| |

|

No Leak: 0.5% convulsions |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Behavioral Changes |

0.450 |

Leak Present: 2.0% changes |

| |

|

No Leak: 1.0% changes |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Infection |

0.500 |

Leak Present: 0% infections |

| |

|

No Leak: 1.0% infections |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Headache |

0.290 |

Leak Present: 6.0% headaches |

| |

|

No Leak: 4.0% headaches |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Death |

0.850 |

Leak Present: 1.0% deaths |

| |

|

No Leak: 1.5% deaths |

| Persistent CSF Leak and Complications |

0.170 |

Leak Present: 30.0% complications present |

| |

|

No Leak: 25.0% complications present |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Convulsion |

0.260 |

Defect Present: 3.0% convulsions |

| |

|

No Defect: 2.0% convulsions |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Behavioral Changes |

0.540 |

Defect Present: 4.0% changes |

| |

|

No Defect: 2.5% changes |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Infection |

0.670 |

Defect Present: 1.0% infections |

| |

|

No Defect: 0.5% infections |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Headache |

0.310 |

Defect Present: 7.0% headaches |

| |

|

No Defect: 5.0% headaches |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Death |

0.910 |

Defect Present: 0% deaths |

| |

|

No Defect: 1.0% deaths |

| Frontal Bone Defect and Complications |

0.350 |

Defect Present: 45.0% complications present |

| |

|

No Defect: 40.0% complications present |

| Convulsion and Behavioral Changes |

0.220 |

Convulsions Present: 6.0% changes |

| |

|

No Convulsions: 3.0% changes |

| Convulsion and Infection |

0.180 |

Convulsions Present: 0% infections |

| |

|

No Convulsions: 2.0% infections |

| Convulsion and Headache |

0.300 |

Convulsions Present: 10.0% headaches |

| |

|

No Convulsions: 6.0% headaches |

| Convulsion and Death |

0.120 |

Convulsions Present: 2.0% deaths |

| Convulsion and Complications |

0.340 |

Convulsions Present:20 . % complications |

| |

|

No Convulsions :15 . % complications |

| Behavioral Changes and Infection |

0.420 |

Changes Present:1 . % infections |

| |

|

No Changes : .5 % infections |

| Behavioral Changes and Headache |

0.530 |

Changes Present :5 . % headaches |

| |

|

No Changes :4 . % headaches |

| Behavioral Changes and Death |

0.890 |

|

| |

|

No Changes :1 . % deaths |

| Behavioral Changes and Complications |

0.270 |

|

| |

|

No Changes :20 . % complications |

| Infection and Headache |

0.200 |

Infection Present: 3.0% headaches |

| |

|

No Infection: 2.0% headaches |

| Infection and Death |

0.800 |

Infection Present: 0% deaths |

| |

|

No Infection: 1.0% deaths |

| Infection and Complications |

0.150 |

Infection Present: 30.0% complications |

| |

|

No Infection: 25.0% complications |

| Headache and Death |

0.950 |

Headaches Present: 1.0% deaths |

| |

|

No Headaches: 1.5% deaths |

| Headache and Complications |

0.400 |

Headaches Present: 40.0% complications |

| |

|

No Headaches: 35.0% complications |

| Death and Complications |

0.600 |

Deaths Present: 5.0% complications |

| |

|

No Deaths: 4.0% complications |

Figure 3.

The Relationship Between Associated Intracranial Injuries and Convulsion.

Figure 3.

The Relationship Between Associated Intracranial Injuries and Convulsion.

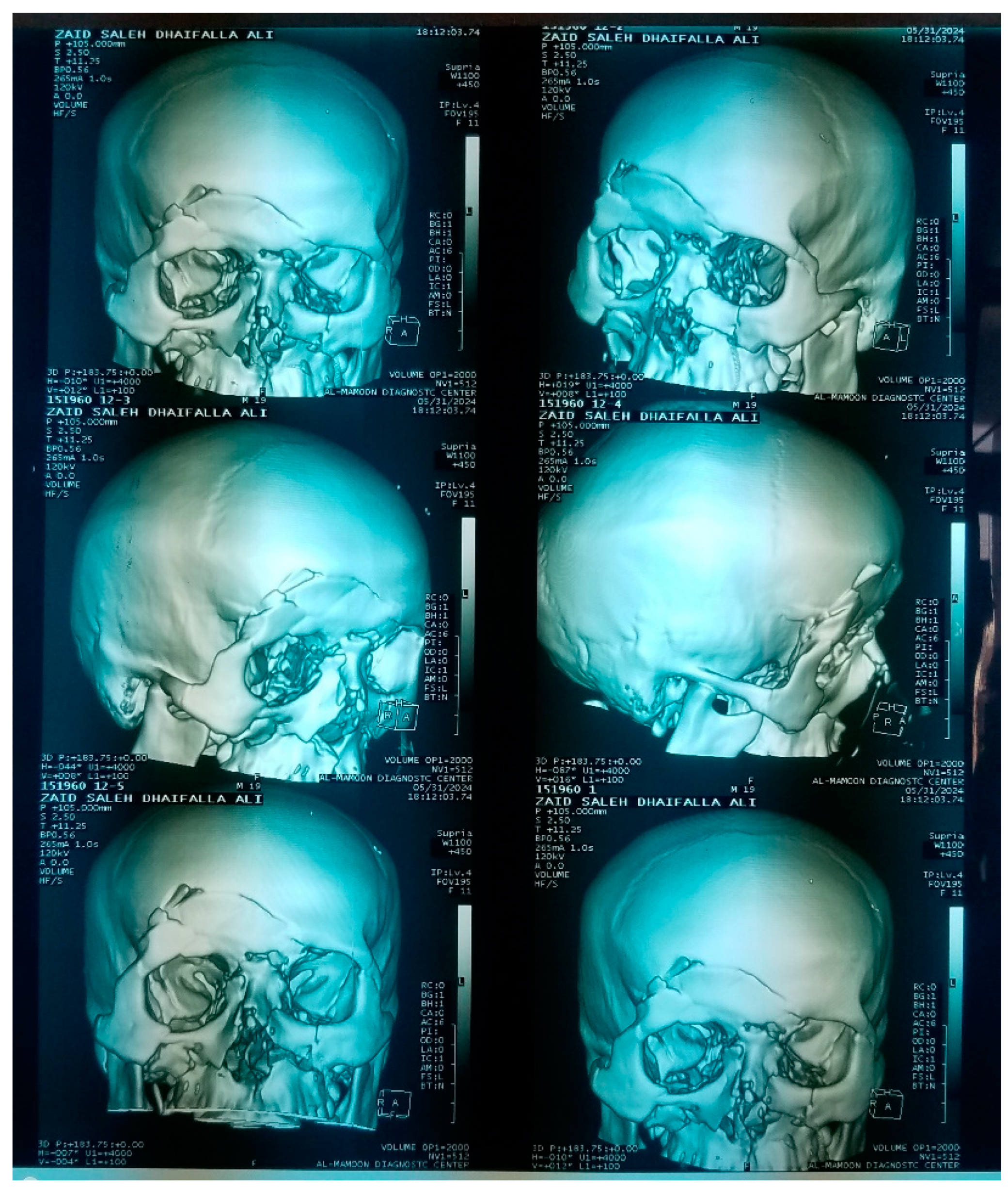

Figure 4.

Young patient with compound depressed frontal bone fracture.

Figure 4.

Young patient with compound depressed frontal bone fracture.

4. Discussion

Depressed fractures of the frontal bone present a complex interplay of factors that influence outcomes and complications. This discussion explores the relationships between these fractures and various demographic, clinical, and management-related variables, drawing on existing literature to elucidate these connections.

The frequency of depressed frontal bone fractures varies significantly across age groups, with younger individuals often sustaining injuries from high-energy impacts such as motor vehicle accidents, while older adults are more likely to experience fractures from low-energy falls (Wan et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2022). This distinction is critical as it informs both preventive strategies and treatment approaches. For instance, younger patients may require more aggressive management due to the potential for more complex fracture patterns and associated intracranial injuries (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022).

Age also correlates with the type of fracture sustained. Younger patients tend to present with comminuted fractures due to the higher energy involved in their injuries, whereas older individuals often exhibit simpler depressed fractures (Wan et al., 2018; Santra, 2023). This relationship is significant as it affects surgical planning and the anticipated outcomes. Comminuted fractures may necessitate more extensive reconstruction efforts, potentially leading to increased complications such as infection or cosmetic deformities (Meyyappan et al., 2019; Marinheiro et al., 2014).

Headaches are a common sequela of frontal bone fractures, and their prevalence can vary by age. Younger patients may experience acute headaches due to trauma, while older patients might suffer from chronic headaches related to complications such as sinusitis or intracranial pressure changes (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). Understanding this relationship is essential for managing post-fracture symptoms and improving patient quality of life.

In our study the predominance of male patients (89.4%) aligns with existing literature, which often cites higher injury rates among males due to riskier behaviors and increased exposure to trauma. The early presentation rate (78.7%) is noteworthy, suggesting greater awareness of symptoms or access to care, which is crucial for improving outcomes.

Gender differences in the type of fracture sustained have been documented, with males more frequently involved in high-energy trauma leading to severe fractures (Wan et al., 2018; Santra, 2023). This disparity necessitates gender-specific considerations in both preventive measures and treatment protocols, as males may require more intensive management due to the nature of their injuries.

In our study, 78.7% of participants presented early after injury, with no significant gender differences (males 76.2%, females 100%; p = 0.219). Road traffic accidents were the main cause of injury (44.7%), affecting more females (60.0%) than males (42.9%), but this was not significant (p = 0.490).

Right-sided fractures were common (48.9%), with 80% of females and 45.2% of males affected, also not significant (p = 0.281). Males were significantly more likely to have open fractures (p = 0.014).

All females had mild GCS scores, while males varied, though this difference was not significant (p = 0.126). There were no significant differences in surgical treatment rates or cosmetic satisfaction between genders, indicating that gender may not strongly influence these outcomes.

Infection rates following frontal bone fractures may also be influenced by gender. Males, who are more likely to sustain high-energy injuries, may experience higher rates of infection due to associated soft tissue damage and open fractures (Wan et al., 2018; Santra, 2023). This finding highlights the need for vigilant monitoring and preventive measures in male patients following such injuries.

The timing of presentation after injury is crucial, as delayed treatment is often associated with more severe injuries and complications. High-energy trauma cases that are not promptly addressed can lead to increased risks of infection and neurological deficits (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). This relationship underscores the importance of timely medical evaluation and intervention in managing depressed frontal bone fractures.

Our research indicated that early presenters (<24 hours) often had road traffic injuries, while late presenters (>24 hours) experienced bomb explosions, with significant correlations but no links to fracture type or outcomes.

The mechanism of injury significantly affects the site of the frontal bone fracture. High-energy impacts typically result in fractures of the anterior table, while lower-energy falls may lead to different fracture locations (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). Understanding this relationship is vital for accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment, as fractures involving the frontal sinuses can lead to additional complications such as chronic sinusitis or cerebrospinal fluid leaks (Marinheiro et al., 2014; Tuusa et al., 2007).

Frontal air sinus involvement is more common in fractures resulting from high-energy trauma. Such injuries can compromise sinus integrity, leading to complications like mucocele formation or chronic sinusitis (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). This relationship emphasizes the need for thorough imaging and assessment of sinus involvement in patients with frontal bone fractures.

Behavioral and personality changes can occur following significant head trauma, particularly when the frontal lobes are affected. High-energy injuries are more likely to result in such changes due to potential damage to the brain's frontal regions (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). This relationship underscores the importance of neuropsychological evaluations in the management of patients with significant head trauma.

In our research, we found that early presenters (<24 hours) were more likely to sustain injuries from road traffic accidents, while late presenters (>24 hours) primarily experienced injuries from bomb explosions. This significant correlation highlights the differing mechanisms of injury based on presentation time (χ²(3) = 20.880, p < 0.001). However, we noted no significant associations between presentation time and fracture type, side, neurological status, or other outcomes. Frontal air sinus involvement also showed no significant relationship with presentation time (χ²(1) = 1.205, p = 0.272). Additionally, while bomb explosions were significantly linked to headaches (p = 0.001), other injury mechanisms did not correlate with complications or mortality rates

The type of fracture is closely linked to the likelihood of frontal air sinus involvement. Comminuted fractures are more likely to extend into the sinuses, leading to complications such as chronic sinusitis or mucocele formation (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). Understanding this relationship is crucial for surgical planning and postoperative management.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score is a critical predictor of outcomes following head trauma. Lower GCS scores are associated with more severe fractures, greater involvement of the frontal air sinuses, and increased risk of complications such as infection and neurological deficits (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). This relationship emphasizes the need for comprehensive neurological assessments in patients with frontal bone fractures.

Our study found that the analysis of GCS scores among patients revealed that 57.4% had mild scores, with no significant correlation to fracture site (p = 0.281). However, higher GCS scores were associated with increased frontal air sinus involvement (p = 0.022) and correlated with intracranial injuries (p = 0.008) and mortality rates (p = 0.004). Open fractures were more prevalent in the frontal air sinus area (p = 0.024) and linked to scar disfigurement (p < 0.001), while no significant associations were noted for management options or other outcomes like persistent CSF leaks

Cosmetic satisfaction is significantly influenced by the extent of scar disfigurement following surgical intervention for frontal bone fractures. Patients with more visible scars tend to report lower satisfaction levels, highlighting the importance of careful surgical planning to minimize scarring (Santra, 2023; Ho et al., 2022). This relationship underscores the need for addressing aesthetic concerns in the management of these injuries.

The study revealed a strong link between scar disfigurement and cosmetic dissatisfaction, with 70% of affected patients dissatisfied. Forehead symmetry significantly influenced satisfaction, while frontal bone defects and behavioral changes also correlated with dissatisfaction.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the relationships between depressed fractures of the frontal bone and various factors such as age, gender, mechanism of injury, and management options are intricate and multifaceted. Understanding these relationships is essential for optimizing treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Future research should continue to explore these dynamics to enhance the management of frontal bone fractures and their associated complications.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: All Authors develop the study's framework and objectives. Data Collection: All Authors gather relevant data through various methods. Data Analysis and Interpretation: All Authors analyze data to identify patterns and derive meaningful conclusions. Drafting the article:All Authors write the initial manuscript based on findings. Critically revising the article: All Authors review and refine the manuscript for clarity and accuracy. Reviewing submitted version of manuscript:All Authors evaluate the final draft before submission. Approving the final version of the manuscript:All Authors give consent for publication, ensuring all contributions are accurately represented.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of AZail Hospital in Sana’a City (Code: 139201818320201632022). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their participation in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

This report was conducted independently and without any external funding or sponsorship that could affect the integrity of the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We also acknowledge the contributions of the medical staff and colleagues who assisted in the clinical management and data collection for this case

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2023). Pediatric ping-pong skull fractures treated with vacuum-assisted elevation.. [CrossRef]

- Gerding, J., Clode, A., Gilger, B., & Montgomery, K. (2014). Equine orbital fractures: a review of 18 cases (2006–2013). Veterinary Ophthalmology, 17(s1), 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Ho, K., Larson, J., Reid, R., & Naran, S. (2022). Management of frontal bone fracture in the pediatric population: a literature review. Face, 3(3), 453-462. [CrossRef]

- Ho, K., Larson, J., Reid, R., & Naran, S. (2022). Management of frontal bone fracture in the pediatric population: a literature review. Face, 3(3), 453-462. [CrossRef]

- Imran, M., Khan, A., Ahmed, S., Ghouri, S., Khan, A., & Farooqui, M. (2018). Compound depressed fractures. The Professional Medical Journal, 25(05), 633-638. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, P. (2019). Frontal bone fractures and frontal sinus injuries: treatment paradigms. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 9(2), 261. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Lee, D., & Cheon, Y. (2016). Secondary reconstruction of frontal sinus fracture. Archives of Craniofacial Surgery, 17(3), 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S., Choi, H., & Kim, J. (2022). Reduction of comminuted fractures of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus using threaded kirschner wires and a small eyebrow incision. Archives of Craniofacial Surgery, 23(5), 220-227. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Choi, H., Shin, D., Uhm, K., Kim, S., Kim, C., … & Jo, D. (2014). Subbrow approach as a minimally invasive reduction technique in the management of frontal sinus fractures. Archives of Plastic Surgery, 41(06), 679-685. [CrossRef]

- Marinheiro, B., Medeiros, E., Sverzut, C., & Trivellato, A. (2014). Frontal bone fractures. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 25(6), 2139-2143. [CrossRef]

- Marinheiro, B., Medeiros, E., Sverzut, C., & Trivellato, A. (2014). Frontal bone fractures. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 25(6), 2139-2143. [CrossRef]

- Meyyappan, A., Jagdish, E., & Jeevitha, J. (2019). Bone cements in depressed frontal bone fractures. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 9(2), 407. [CrossRef]

- Meyyappan, A., Jagdish, E., & Jeevitha, J. (2019). Bone cements in depressed frontal bone fractures. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 9(2), 407. [CrossRef]

- Meyyappan, A., Jagdish, E., & Jeevitha, J. (2019). Bone cements in depressed frontal bone fractures. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 9(2), 407. [CrossRef]

- SHALTOUT, M. and Ali, M. (2018). Reconstruction of comminuted frontal bone fractures by rib graft or titanium mesh: assiut university hospital experience. The Medical Journal of Cairo University, 86(December), 3459-3466. [CrossRef]

- Sakat, M., Kılıç, K., Altaş, E., Gözeler, M., & Üçüncü, N. (2016). Comminuted frontal sinus fracture reconstructed with titanium mesh. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 27(2), e207-e208. [CrossRef]

- Salonen, E., Koivikko, M., & Koskinen, S. (2007). Multidetector computed tomography imaging of facial trauma in accidental falls from heights. Acta Radiologica, 48(4), 449-455. [CrossRef]

- Santra, S. (2023). Uncovering the hidden: trivial trauma reveals congenital defects in frontal bone with underlying extradural hematoma. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 11(1), 74-76. [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayanan, R., Raghu, K., Deepika, S., & Sarath, K. (2018). Management of frontal sinus injuries. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 8(2), 276. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., Khan, F., Rahman, Z., Yadav, P., Khan, F., & Anees, M. (2022). Types of fractures in cranial vault followed by a head injury: a retrospective cross sectional study. PJMHS, 16(1), 761-763. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa, R., Furtado, S., Sansgiri, T., & Vala, K. (2022). Management of frontal bone fracture in a tertiary neurosurgical care center—a retrospective study. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 13, 60-66. [CrossRef]

- Săceleanu, V., Tâlvan, E., Fagetan, M., Mohor, C., & Ciurea, A. (2017). Associated titanium mesh and native bone cranioplasty in posttraumatic reconstruction of frontal skull defects. Key Engineering Materials, 752, 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Tuusa, S., Peltola, M., Tirri, T., Lassila, L., & Vallittu, P. (2007). Frontal bone defect repair with experimental glass-fiber-reinforced composite with bioactive glass granule coating. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B Applied Biomaterials, 82B(1), 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y., Lantz, B., Cusack, B., & Szabo-Rogers, H. (2018). Prickle1 regulates differentiation of frontal bone osteoblasts. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).