Introduction

Facial trauma is generally quite common in large urban centers due to heavy traffic and high rates of violence. Fractures of the frontal sinus account for 5 to 15%1-4 of facial fractures. The frontal bone is one of the strongest bones in the facial skeleton, requiring between 800 and 2200 pounds of force for a fracture to occur. 3

For frontal sinus fractures to occur, a high-intensity trauma directly to the region is necessary. Due to the intensity of the trauma in the area, frontal sinus fractures are often accompanied by traumatic brain injury, intracranial lesions, orbital injuries, or multiple facial fractures or injuries in other regions of the body, almost always requiring a multidisciplinary assessment and treatment 5-6. Frontal sinus fractures can involve the anterior wall of the sinus, the posterior wall, and the frontal sinus duct, and are described as non-displaced, displaced, or comminuted.4

During the physical examination of the patient, signs such as depression of the frontal region, lacerations in the tissue, edema, and bruising may indicate the presence of fractures in the frontal sinus area.7 Fractures of the orbital roof may also be associated with superior orbital fissure or apex orbital syndrome, thus compromising the patient's eye movement7. Another important sign is the nasal drainage of cerebrospinal fluid ; this fluid indicates a fracture of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus and can guide us regarding future treatment.4-7

There are three key points in the treatment of frontal sinus fractures: the degree of fracture displacement or comminution, involvement of the anterior and posterior walls of the frontal sinus, and the patency of the frontonasal duct.8,10 Treatment can be conservative, involving observation of signs and symptoms over a long period, or surgical, which includes repair of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus, obliteration of the frontonasal duct, and cranialization for repair of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus. 1,8,9,10 The experience of the surgical team and the use of an algorithm assist in choosing the best treatment for the patient.1,9

In conservative cases with minor detachments of up to 2mm, treatment may involve rest and nasal irrigation with saline solution. Even in the simpler cases, long-term follow-up should always be conducted, as many complications from these fractures can be delayed. 3,7

For surgical treatments, the coronal approach is almost always used. This approach allows for wide exposure of the upper third of the face, low morbidity, and the necessary aesthetics for treating frontal sinus fractures.10 With this access, the reduction and fixation of fractures become easier, in addition to the possibility of concurrent cranial procedures, obtaining grafts, obliterating the frontonasal duct, myofascial flaps, as well as accessing adjacent fractures of the upper orbit and middle third of the face. Other options such as access through the laceration itself, superciliary access, or the gull-wing approach are used for fractures with minimal displacement that require limited fixation.11,12

The obliteration of the frontal sinus is necessary when there are fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus without the need for neurosurgical intervention, when there is compromise of the drainage system of the frontal sinus, in communications of the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, chronic infections, and non-malignant conditions.13 With the obliteration of the frontal sinus, there is an isolation of the intracranial contents, correcting fluid leaks, preventing infections and local sequelae, and restoring functional integrity and the frontal aesthetic contour.3

To avoid the risk of severe infection (meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, frontal sinus abscess, and osteomyelitis), intervention for frontal sinus fractures is recommended within 48 hours after trauma. The physical conditions of patients may cause delays in the management of these cases, potentially resulting in an increase in infections.14

The complications of frontal sinus fractures are concerning due to the anatomical region and the close proximity to highly sensitive structures such as the brain and the orbits.15 These complications can occur in up to 10% of cases and can be classified as early (up to 6 months) or late (after 6 months).4 Early complications include: brain injury, aesthetic deformities related to the contour of the skull, paresthesia of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, meningitis, sinusitis, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. In late complications, we can mention: mucocele, mucopyocele, cerebral abscess, meningitis, hypoesthesia, chronic pain, edema, visual disturbances, and contour deformity.4,7,14,15

Complications may be related to the surgical access used in the surgical procedure. These include: scarring, alopecia, deficit of the frontal branch of the facial nerve, and infection.10 The management of these complications can be conservative, utilizing medications or local clinical procedures, until further surgical or neurosurgical intervention is required. Due to these factors, there is a significant need for early diagnosis of these complications.

Objective

This study aims to retrospectively present our experience in the management of frontal sinus fractures, thus understanding the entire epidemiology of fractures and guiding us in the best form of treatment.

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and had an Ethical approval committed in São Leopoldo Mandic University.

This retrospective study analyzed medical records of patients with frontal sinus fractures, which occurred from 2017 to 2024 (8 years), in the city os Piracicaba (423.000 inhabitants), State of São Paulo (Brazil), involving three trauma reference hospitals in the region. These patients were diagnosed and treated by the same Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery team. Using as a basis the algorithm present in bell's article1

The necessary inclusion criterion was the complete completion of the medical record from the initial diagnosis to the outcome of treatment and minimum 6 months of post-surgical control.

The data were tabulated in th Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), thus generating the tabulation of these data and the tables and graphs necessary to our study.

Patients were divides according to gender, age, trauma etiology, type of treatment and associated injuries.

Results

Demographics and the Mechanism of Injury

The study reviewed 40 patients (39 male, 1 female) who were treated and followed up for frontal sinus fractures with an average age of 42.9 years (range 1-89 years). The average follow-up period was 8 years (2017 to 2016). The mechanisms of injury were as follows: Traffic accident in 15 patients, falls in 7 patients, physical aggression in 5 patients, sports accidents in 7 patients and labor accidents in 6 patients (

Table 1).

Associated Injuries

Injuries associated with the frontal sinus fractures are summarized in

Table 2. The most associated fractures were soft tissue lacerations in 12 patients and zygomatic-maxillary complex fractures in 8 patients. Other associated injuries observed: nasal bone fracture in 4 cases, orbital roof fracture in 7 cases, orbital floor fracture in 5 cases, maxillary fractures (Le Fort I, II, III) in 8 cases, mandibular fracture in 0 cases, posterior wall fracture of the frontal sinus in 5 cases, ethmoid fracture in 1 case, ocular laceration in 2 cases, and soft tissue laceration in 12 cases.

Frontal Sinus Fracture Characteristics and Management Strategy

When categorized, 22 patients received conservative treatment (55%), while 18 patients were treated surgically. 34 of 40 patients (85 %) had isolated anterior table fractures, 1 patient (2.5%) had isolated posterior table fractures, and 5 patients (12.5%) had fractures involving both anterior and posterior tables (

Table 3). A total of 23 (57.5%) frontal sinus fractures were comminuted, and 17 (42.5%) were simple. Both fracture patterns were significantly associated with surgical intervention (odds ratio [OR] = 15, p < .001). Anterior or posterior table involvement was not found to be associated with surgical repair vs observation (p = 0.650).

Management Strategy of Frontal Sinus Fractures by Table Involvement

Involvement of the anterior table, posterior table, or both tables was not associated with management strategy, operative approach, or operation type (p= 0.456 and p=0.105, respectively) (

Table 4). Only the anterior aspect of the sinus was treated in 13 cases, while craniotomy and repair of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus were performed in 2 cases, and obliteration of the duct with reconstruction of the anterior wall was necessary in 3 cases. For internal fixation, plates and screws were used in 10 cases. When there was communication or loss of fragments, titanium mesh was required in 8 cases to ensure anatomical and aesthetic reconstruction.

Table 4.

Management Strategy of Frontal Sinus Fractures by Table Involvement.

Table 4.

Management Strategy of Frontal Sinus Fractures by Table Involvement.

| |

Anterior Table |

Posterior Table |

Anterior + Posterior Table |

p-Value |

| Operative Approach |

16 |

0 |

2 |

0.456 |

| Coronal |

14 |

0 |

2 |

|

| Laceration |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Operation |

|

|

|

0.105 |

| Cranialization |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Obliteration |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

| ORIF |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Mash Titanium required |

4 |

0 |

2 |

|

| Observation |

18 |

1 |

2 |

|

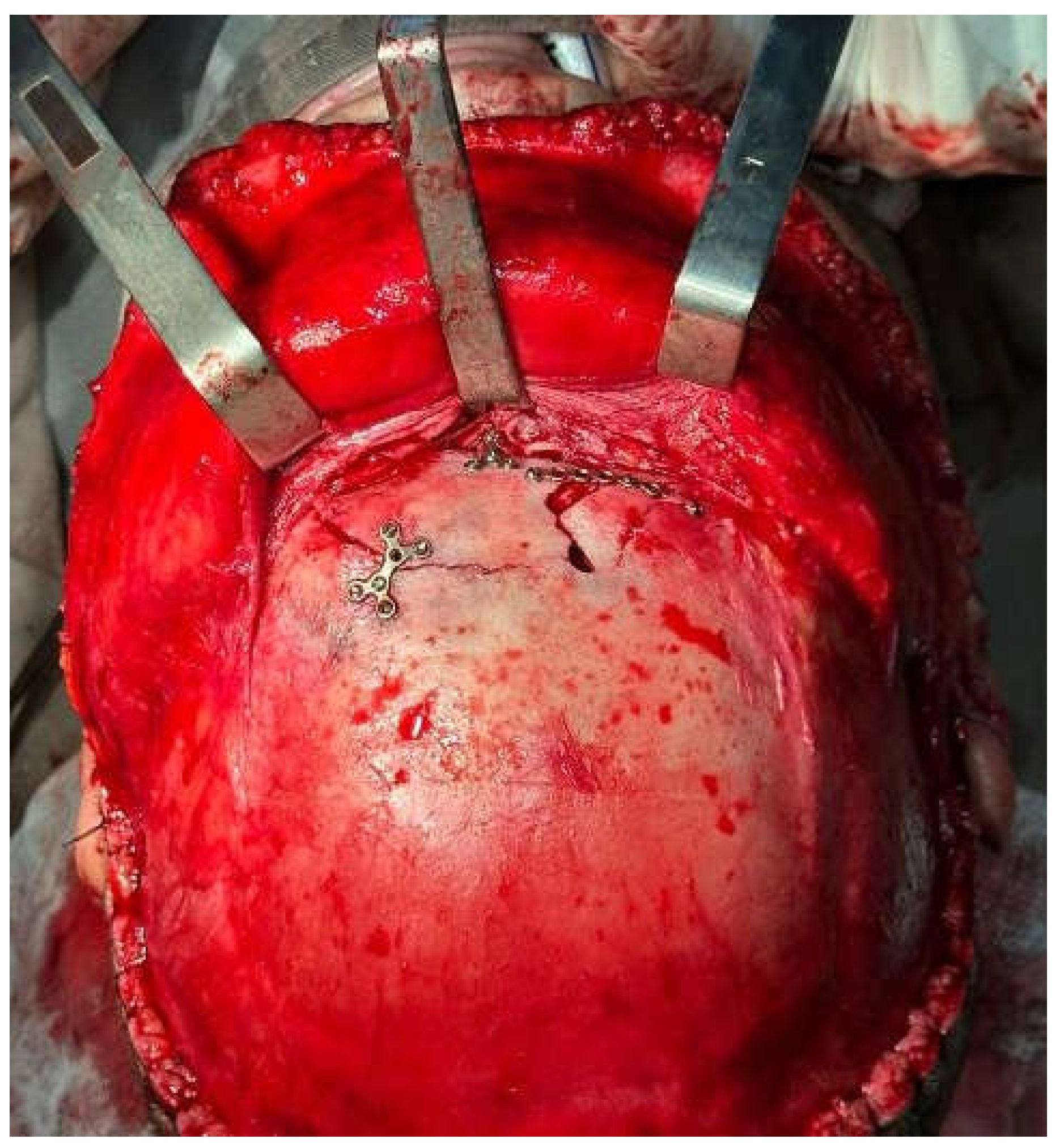

Figure 1.

– Osteosynthesis of fracture of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. The image illustrates the surgical technique used to stabilize the defect and recover bone integrity.

Figure 1.

– Osteosynthesis of fracture of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. The image illustrates the surgical technique used to stabilize the defect and recover bone integrity.

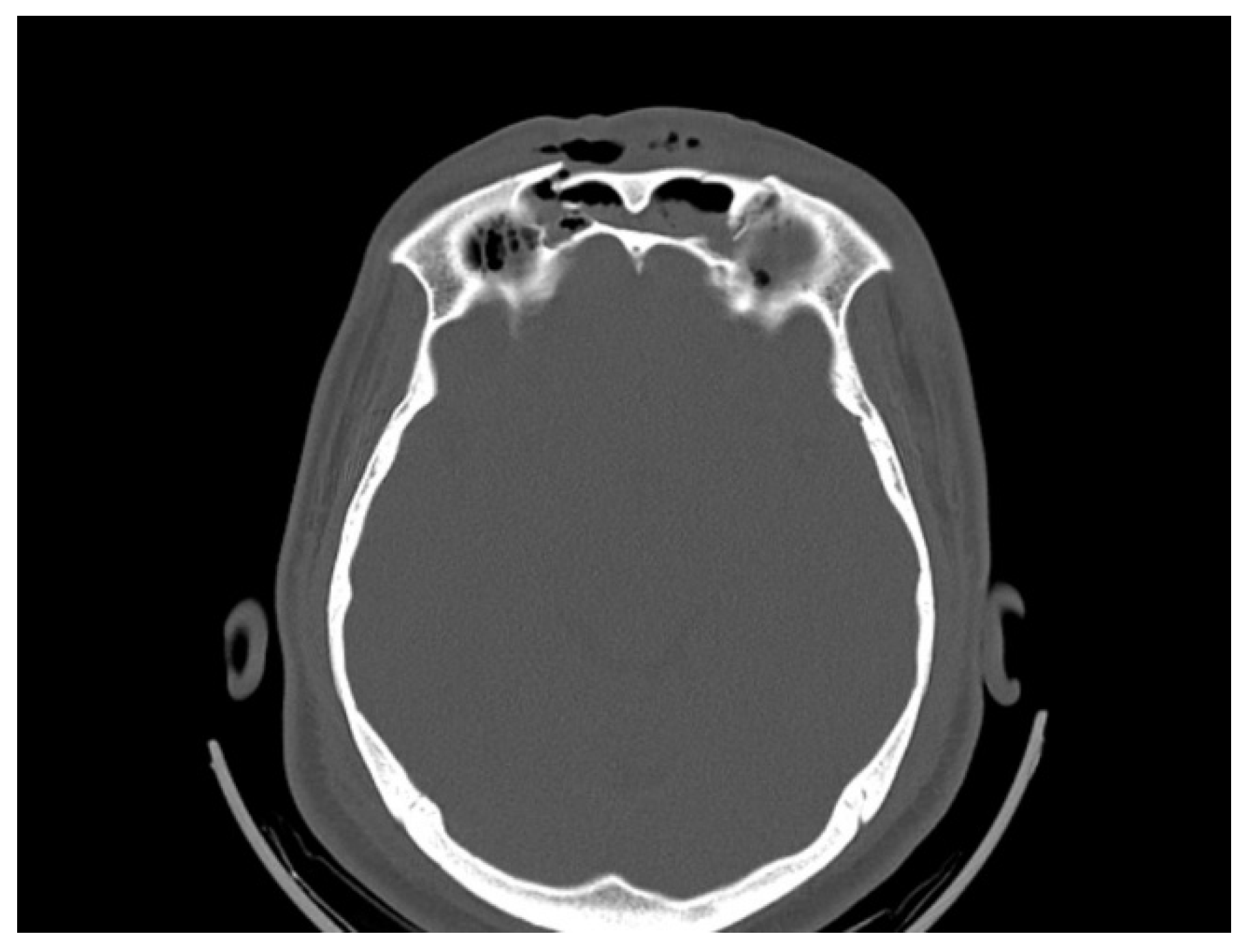

Figure 2.

– Axial tomography showing the fracture of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. The image highlights the bone injury and the extent of the fracture.

Figure 2.

– Axial tomography showing the fracture of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. The image highlights the bone injury and the extent of the fracture.

Discussion

Fractures of the frontal bone require multidisciplinary treatment due to their complexity. In emergency settings, neurosurgery and trauma surgery are typically the first specialties to be called upon in cases of cranial fractures. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can lead to significant neurological damage, including functional deficits, hematomas, and intracranial hemorrhages, which necessitate immediate evaluation and management.

Frontal bone fractures, often resulting from high-impact trauma, can lead to significant neurological complications due to their proximity to critical brain structures. These injuries frequently cause concussions, cognitive impairments, brain contusions, and intracranial hematomas, which can result in elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and subsequent neurological deficits. Given the complexity and potential for severe outcomes, a multidisciplinary approach is essential for effective management. Collaboration among neurosurgeons, traumatologists, neurologists, intensivists, and rehabilitation specialists is crucial for providing comprehensive care, including surgical intervention, monitoring, and long-term rehabilitation. Early intervention and continuous, specialized care are key to optimizing patient outcomes and minimizing the risk of permanent neurological damage.

When it comes to fractures of the frontal sinus, there is unanimity among authors regarding the preference for the male sex.2,6,16,17 Now, regarding the etiologies of fractures, our data indicate that traffic accidents are the most prevalent cause (37.5%). When compared to neighboring cities with similar populations (400,000 inhabitants), they also exhibited significant incidence rates 2,16, which aligned with studies conducted in the capital (11 million inhabitants).17 Only the study by Oslin et al. (2024) conducted in a large city with a population of 500,000 reported falls as the most prevalent incident. The age range also varied, with the group aged 20 to 40 being the most affected. 2,6,16,17. In large urban centers, there is an increase in traffic accident cases, primarily due to the large population sample. 17. In order to reduce this number, the automotive industry is in constant evolution regarding the levels of safety offered to passengers, including more protected cockpits, seat belts, airbags, and new technologies that assist in braking to prevent collisions. In posterior wall of frontal bone, the neurosurgery team also is requires for cranialization or drainage of intracranial hematoma.

The coronal approach is the first choice for the treatment of the frontal bone fractures, however in the study of Elkahwagi, 2020, it says the coronal approach has a considerable risk of complications, including a large visible scar, alopecia, and numbness. The coronal incision should be reserved for cases of comminuted wide fractures and bilateral fractures. So a eyebrown incision is preferred 21 There is still no consensus on the best treatment for frontal sinus fractures. 18, in our patients, we utilize the diagram from a classic study conducted by Bell et al. (2007)1 that categorizes fractures as displaced or non-displaced and assesses whether the frontonasal duct is intact. This diagram also evaluates the displacement and comminution of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, thereby determining the possible treatments: cranialization and repair of the anterior wall, repair of the anterior wall only, obliteration of the frontonasal duct, and repair of the anterior wall. In nondisplaced fractures of frontal sinus with a patent nasofrontal duct, only clinical observation with head elevation and sinus precaution is needed. For frontal sinus fractures with nasofrontal duct outflow obstruction, either sinus obliteration or cranialization is indicated depending on posterior wall involvement. In displaced frontal sinus fractures with no obstruction of the nasofrontal duct, reconstruction of the anterior wall is indicated 7, for cranialization, intracranial hematoma drainage or repair of the posterior wall fractures, a neurosurgery team is required. A new algorithm proposed by Doonquah et al. (2012) is also considered. 12, It adds the possibilities of endoscopic treatment approaches for frontal sinus fractures via transnasal access, reducing scars and potential complications.

There is also the possibility of endoscopic approaches such as brow lift or hairline techniques being used for minor corrections, particularly when there are no fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus or compromise of the frontonasal duct. 19. The indications of this technique are patients who have isolated anterior table 22. There is still a significant limitation of this technique, particularly regarding the reduction and fixation of the fragments. 12,19. Preoperative imaging and informed consent are crucial in planning endoscopic repair for frontal bone fractures. The fracture is exposed and repaired using a Medpor implant, which is stabilized with percutaneous screws. Prefabricated Medpor implants, though offering a better fit, are more expensive and take longer to fabricate. This minimally invasive technique ensures stable repair and good cosmetic results, however has increased costs and takes 6 weeks for fabrication of the material 22 . The endoscopic approach has also been used for evaluation of the outflow tract and removal of the obstruction by endoscopic clearance of the frontal recess when needed, so another large approach or bone removal can be avoid, causing more trauma. 21 In our cases, we mostly opt for the coronal approach when there is detachment and the need for fixation of the bone fragments. The coronal approach provides extensive surgical access to the upper and middle facial thirds, with few long-term complications, excellent aesthetic results, and low morbidity. 10.

Conservative treatment for non-displaced fractures with an intact frontonasal duct is based on observation and nasal irrigation parameters. 1. However, no matter how straightforward this outcome may be for surgical procedures, long-term follow-up is still recommended in order to prevent late complications such as aesthetic defects and infections, especially if there are fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus. 7.

When it comes to complications, our study experienced few complications; however, our follow-up period was 8 years, whereas studies suggest follow-up periods of 15 to 20 years. 9, 20. Complications have a rate of less than 10% 4,2,6,7,16,17, in agreement with our study. Local hypoesthesias or hyperesthesias are related to the coronal process 10 and manipulation of the supraorbital nerve, they are generally well managed and temporary, and are not a plausible patient complaint.

To reduce the risk factors for complications, it is recommended to operate fractures within 48 hours 14,20 , If possible, leave no drains. Extravasation of cerebrospinal fluid for more than 7 days also increases the risk of complications 20. When it comes to complications related to frontonasal obliteration, we can also consider complications related to the graft placed, such as: necrosis, reabsorption, infection and mucosal thickening. 13.

Even though craniotomies are rarely performed in studies due to the low incidence of surgical need on the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, they can produce more severe complications that are difficult to treat clinically or surgically.7. Intravenous antibiotic therapy and new surgical or neurosurgical interventions may be necessary, thus increasing the number of complications and their severity. 7,14,20.

Conclusions

Frontal fractures require a trained multidisciplinary team for success in the final result. There is difficulty in diagnosis, surgical planning, and treatment management.

The analyzed data of frontal sinus fractures showed a prediletion for males, with an average age of 41 years and traffic accidents were the majority of cases. Conservative treatment was mostrly performed.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Brar P, Potter JK, Potter BE. A protocol for the management of frontal sinus fractures emphasizing sinus preservation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 May;65(5):825-39. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli MF, Gabrielli MA, Hochuli-Vieira E, Pereira-Fillho VA. Immediate reconstruction of frontal sinus fractures: review of 26 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 May;62(5):582-6. [CrossRef]

- Vincent A, Wang W, Shokri T, Gordon E, Inman JC, Ducic Y. Management of Frontal Sinus Fractures. Facial Plast Surg. 2019 Dec;35(6):645-650. [CrossRef]

- Guy WM, Brissett AE. Contemporary management of traumatic fractures of the frontal sinus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2013 Oct;46(5):733-48. [CrossRef]

- Obayemi A, Losenegger T, Long S, Spielman D, Casiano MF, Reeve G, Kacker A, Stewart M, Sclafani A. Frontal Sinus Fractures: 10-Year Contemporary Experience at a Level 1 Urban Trauma Center. J Craniofac Surg. 2021 Jun 1;32(4):1376-1380. [CrossRef]

- Oslin K, Shikara M, Yoon J, Pope P, Bridgham K, Waghmarae S, Hebert A, Liang F, Vakharia K, Justicz N. Management of Frontal Sinus Fractures at a Level 1 Trauma Center: Retrospective Study and Review of the Literature. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024 Mar;17(1):24-33. Epub 2023 Feb 9. [CrossRef]

- Jing XL, Luce E. Frontal Sinus Fractures: Management and Complications. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019 Sep;12(3):241-248. Epub 2019 Feb 19. [CrossRef]

- Bell RB. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009 May;21(2):227-42. [CrossRef]

- Pawar SS, Rhee JS. Frontal sinus and naso-orbital-ethmoid fractures. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014 Jul-Aug;16(4):284-9. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli MA, Monnazzi MS, Gabrielli MF, Hochuli-Vieira E, Pereira-Filho VA, Mendes Dantas MV. Clinical evaluation of the bicoronal flap in the treatment of facial fractures. Retrospective study of 132 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012 Jan;40(1):51-4. Epub 2011 Feb 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajmohan S, Tauro D, Bagulkar B, Vyas A. Coronal/Hemicoronal Approach - A Gateway to Craniomaxillofacial Region. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 Aug;9(8):PC01-5. Epub 2015 Aug 1. [CrossRef]

- Doonquah L, Brown P, Mullings W. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012 May;24(2):265-74, ix. Epub 2012 Mar 2. [CrossRef]

- Monnazzi M, Gabrielli M, Pereira-Filho V, Hochuli-Vieira E, de Oliveira H, Gabrielli M. Frontal sinus obliteration with iliac crest bone grafts. Review of 8 cases. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2014 Dec;7(4):263-70. Epub 2014 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Podolsky DJ, Moe KS. Frontal Sinus Fractures. Semin Plast Surg. 2021 Oct 7;35(4):274-283. [CrossRef]

- Kim IA, Boahene KD, Byrne PJ. Trauma in Facial Plastic Surgery: Frontal Sinus Fractures. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;25(4):503-511. [CrossRef]

- Montovani JC, Nogueira EA, Ferreira FD, Lima Neto AC, Nakajima V. Surgery of frontal sinus fractures: epidemiologic study and evaluation of techniques. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 Mar-Apr;72(2):204-9. [CrossRef]

- Prado BN, Moreira TCA, Buratti CJM, de Melo DS, Gavranich Jr J. Reconstruction of frontal sinus anterior wall. Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac. 2012 15(1): 21-24.

- Al-Moraissi EA, Alyahya A, Ellis E. Treatment of Frontal Sinus Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Dec;79(12):2528-2536. Epub 2021 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Fattahi T, Salman S. An aesthetic approach in the repair of anterior frontal sinus fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Sep;45(9):1104-7. Epub 2016 May 4. [CrossRef]

- Bellamy JL, Molendijk J, Reddy SK, Flores JM, Mundinger GS, Manson PN, Rodriguez ED, Dorafshar AH. Severe infectious complications following frontal sinus fracture: the impact of operative delay and perioperative antibiotic use. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Jul;132(1):154-162. [CrossRef]

- Elkahwagi, M., & Eldegwi, A. (2020). What is the role of the endoscope in the sinus preservation management of frontal sinus fractures? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Strong, E. B., & Kellman, R. M. (2006). Endoscopic Repair of Anterior Table—Frontal Sinus Fractures. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America, 14(1), 25–29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).