Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experiment

2.2. Weather Conditions

2.3. Soil Analyses

- plantless, fallow buffer zone of the field experiment – sample ‘0’,

- conventional tillage,

- reduced tillage,

- strip tillage,

- no tillage.

2.4. Identification of Soil Microorganisms. DNA Extraction

2.5. PCR Amplification

2.6. Statistical and Bioinformatics Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

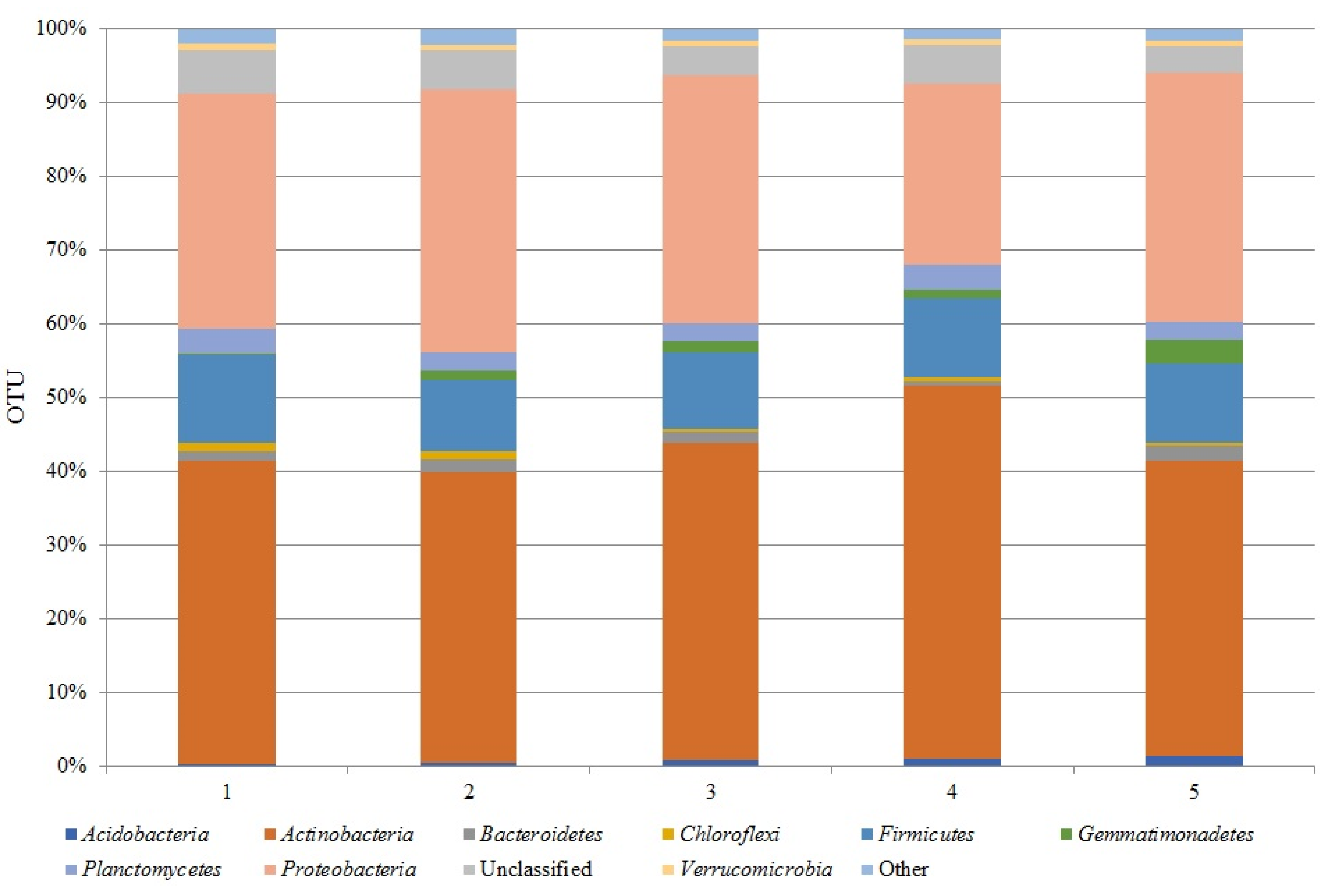

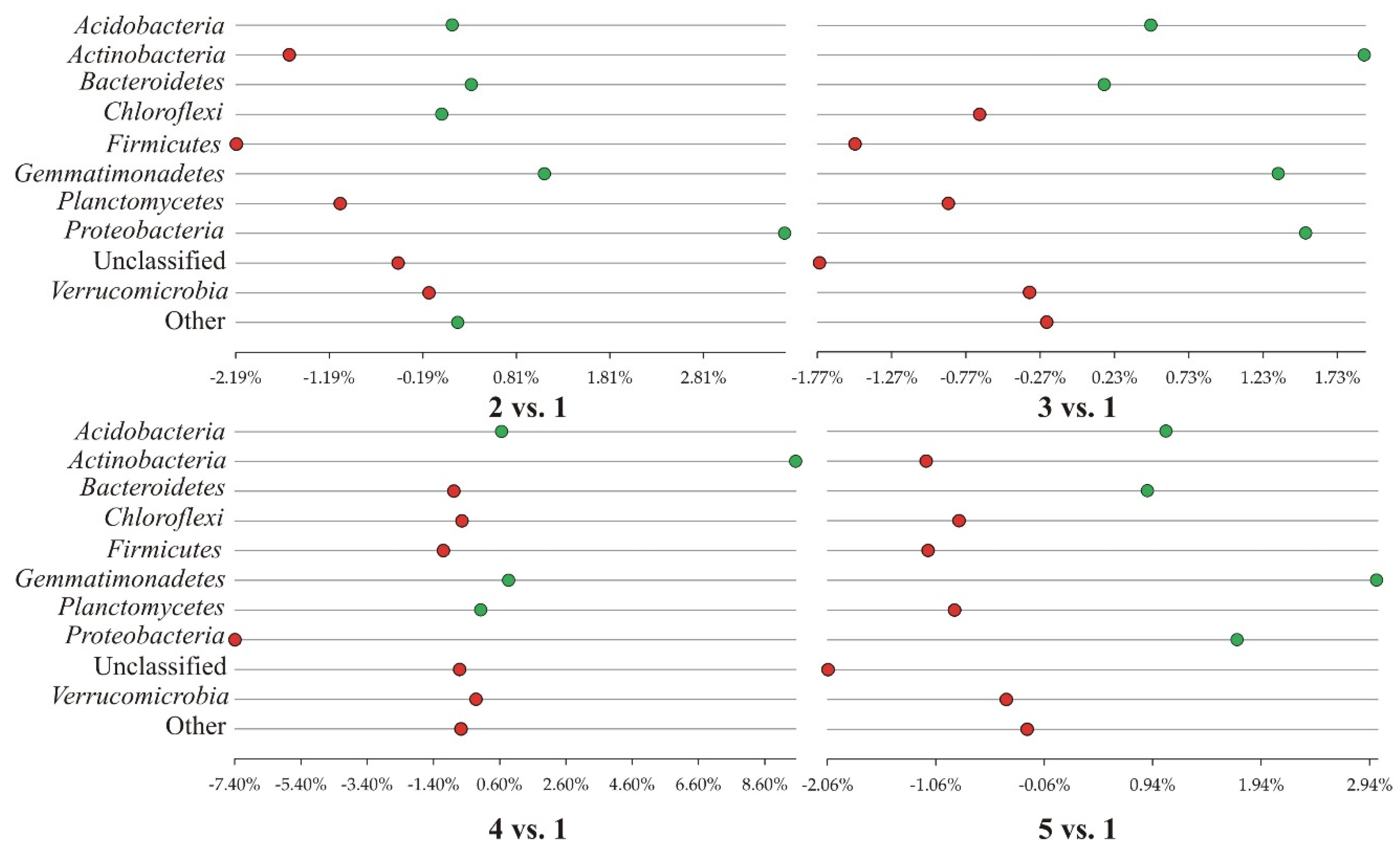

3.1. Bacterial Phyla

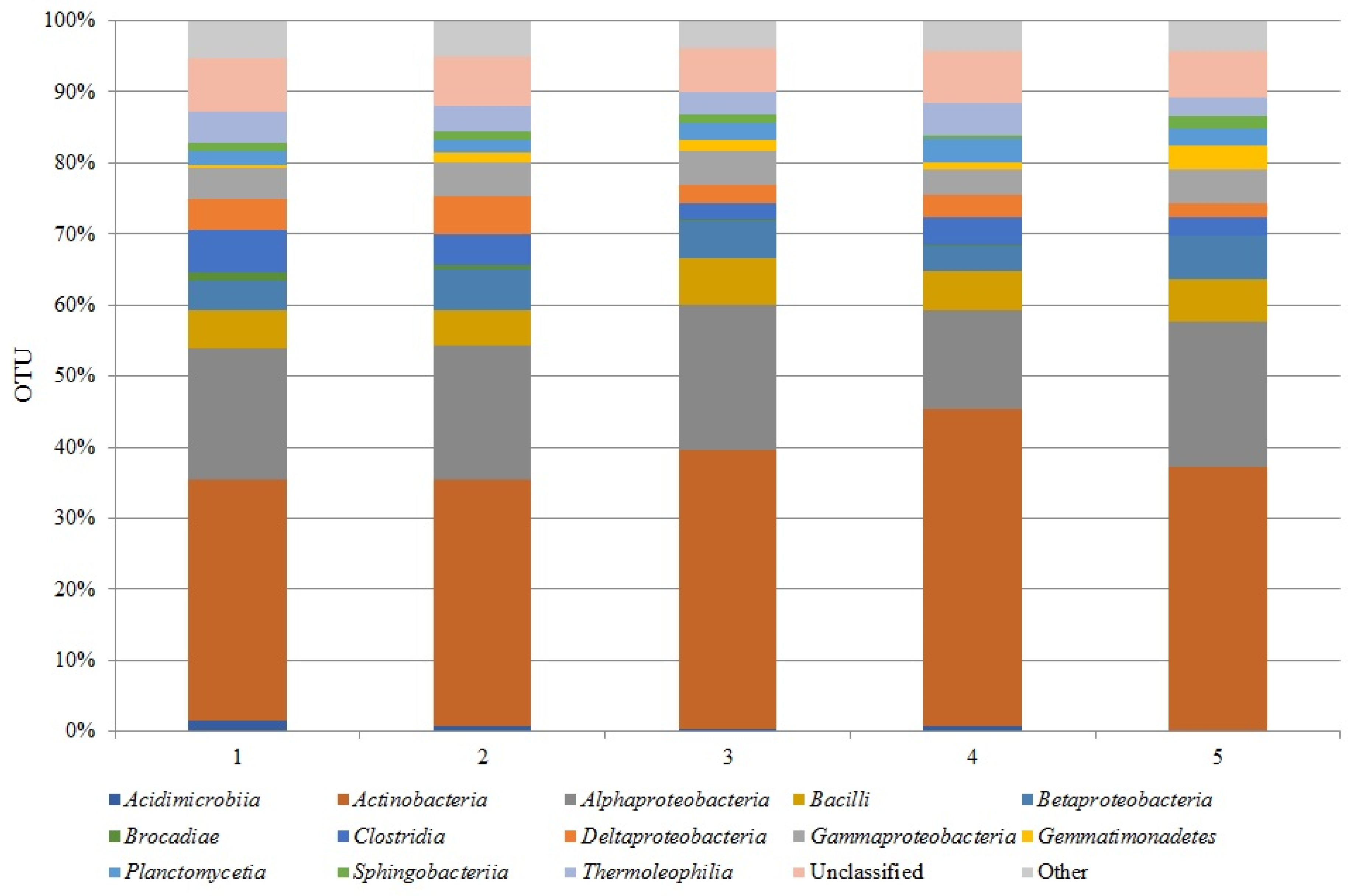

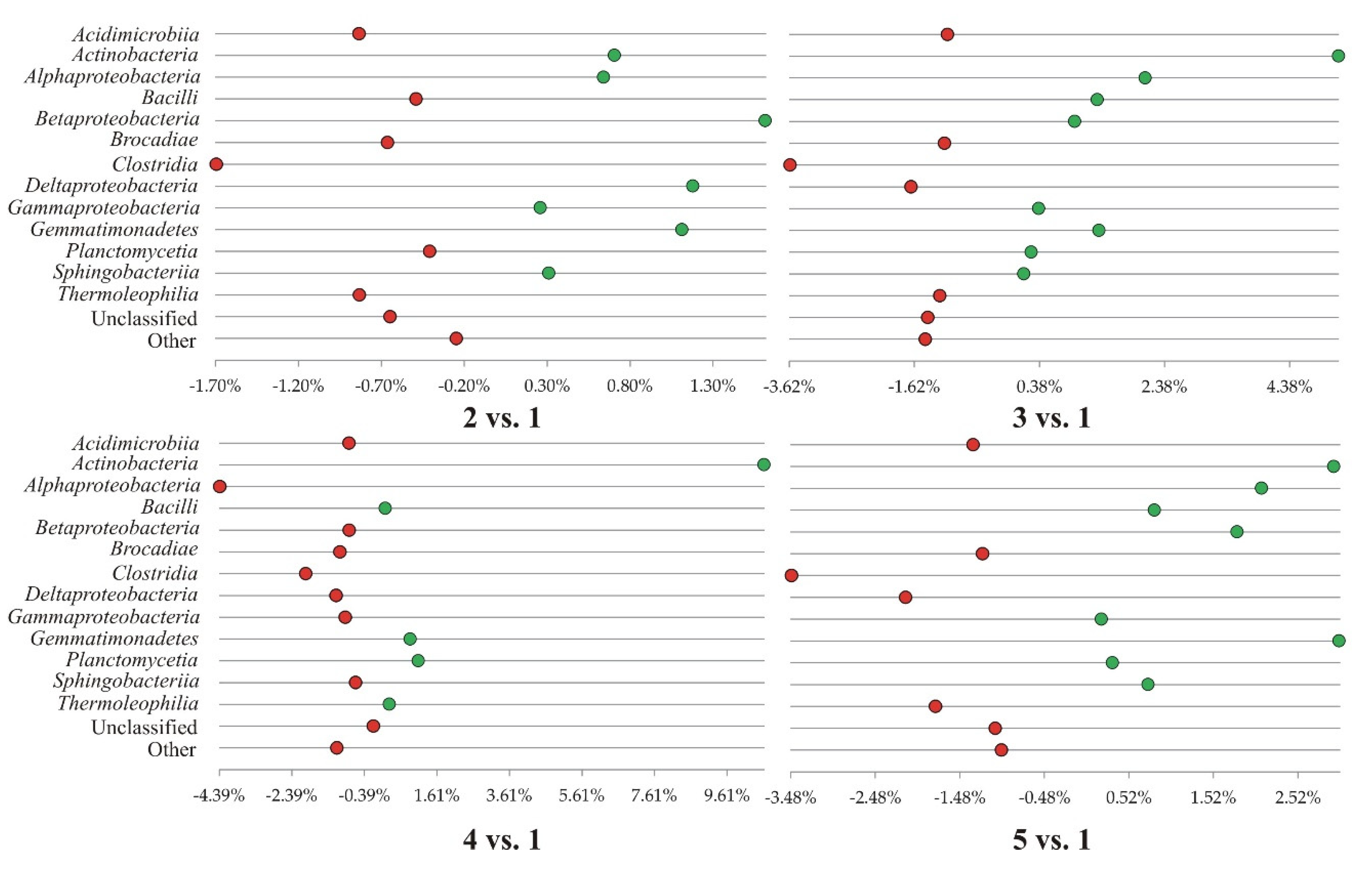

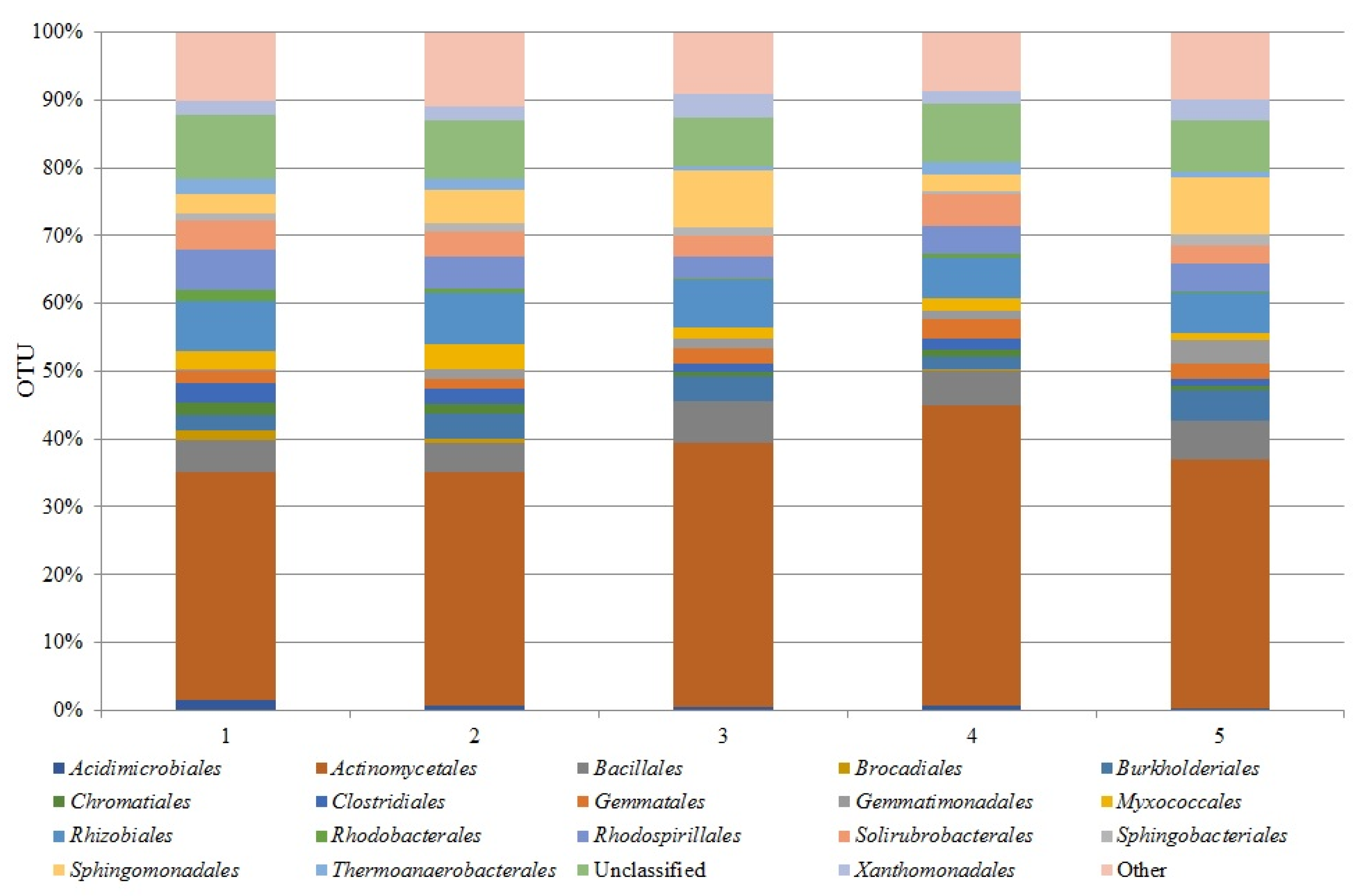

3.2. Dominant Classes and Orders of Soil Bacteria Under Horse Beans Cultivated in Different Systems

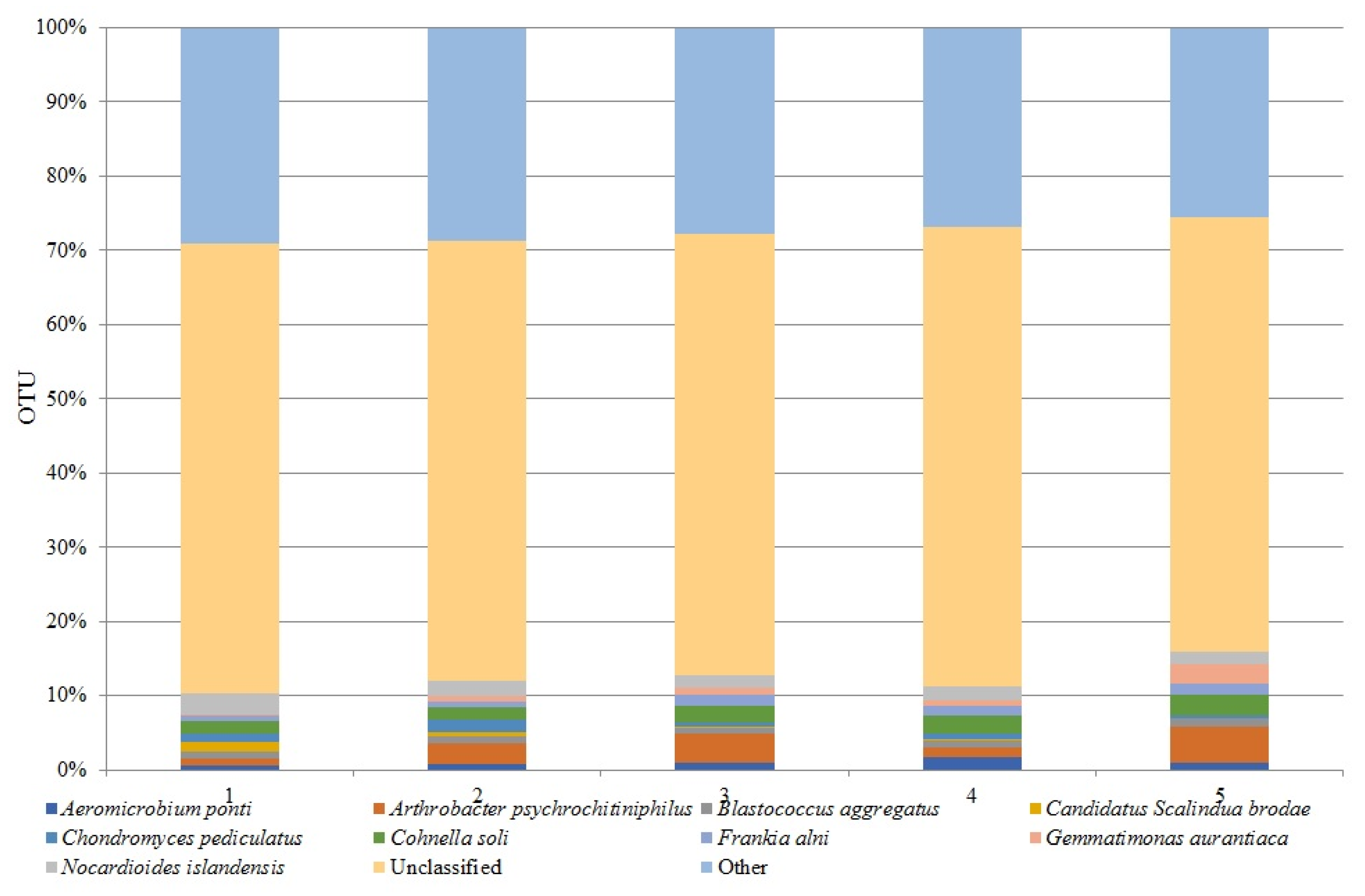

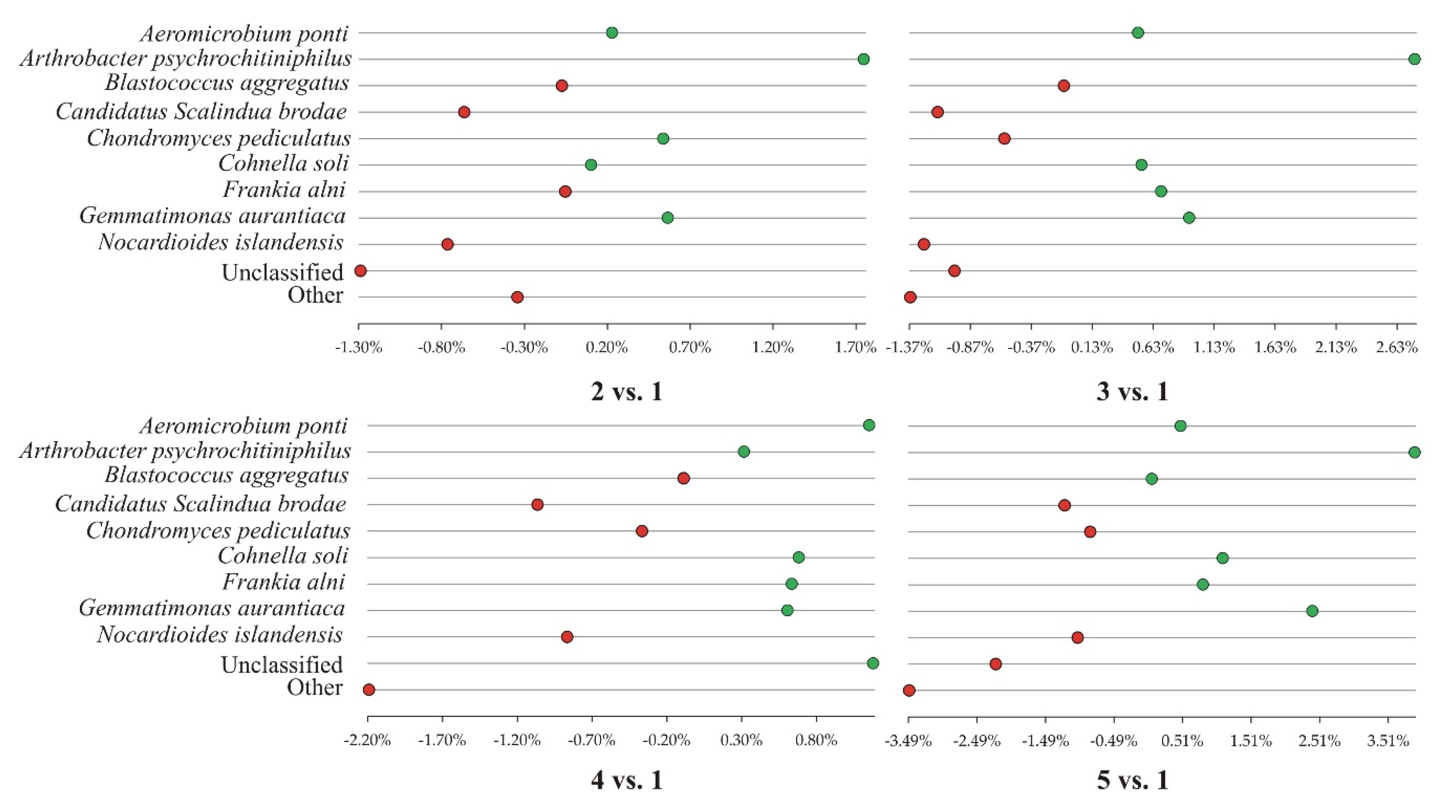

3.3. Dominant Bacterial Species in Different Soil Cultivation Technologies Under Horse Bean Plantation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; Wang, P.; McKenna, B.A.; Lombi, E. Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12 000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9575–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, P.; Hati, K.M.; Dalal, R.C.; Dang, Y.P.; Kopittke, P.M.; McKenna, B.A.; Menzies, N.W. Effect of 50 Years of No-Tillage, Stubble Retention, and Nitrogen Fertilization on Soil Respiration, Easily Extractable Glomalin, and Nitrogen Mineralization. Agronomy 2022, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swędrzyńska, D.; Grześ, S. Microbiological parameters of soil under sugar beet as a response to the long-term application of different tillage systems. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24(1), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, D.C.; Kahl, K.; Carlson, B.; Huggins, D.R.; Paulitz, T. Soil acidification modifies soil depth-microbiome relationships in a no-till wheat cropping system. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, S.; Panettieri, M.; Madejón, E.; Gómez Macpherson, H.; Moreno, F.; Murillo, J.M. Implementation of chiselling and mouldboard ploughing in soil after 8 years of no-till management in SW, Spain: Effect on soil quality. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 112, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Mahamood, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Liang, A.; Liang, W. Tillage and crop succession effects on soil microbial metabolic activity and carbon utilization in a clay loam soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2018, 88, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeau, S.; Baudron, A.; Adeux, G. Is Tillage a Suitable Option for Weed Management in Conservation Agriculture? Agronomy 2020, 10, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Niewiadomska, A.; Pilarska, A.A. The Problem of Weed Infestation of Agricultural Plantations vs. the Assumptions of the European Biodiversity Strategy. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka-Jankowiak, I.; Blecharczyk, A.; Swedrzynska, D.; Sawinska, Z.; Piechota, T. The effect of long-term tillage systems on some soil properties and yield of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Agricultura, 2016; 15(1), 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Swędrzyńska, D.; Małecka-Jankowiak, I. The Impact of Tillaging Spring Barley on Selected Chemical, Microbiological, and Enzymatic Soil Properties. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, D.A.; Ivanova, E.A.; Zhelezova, A.D.; Semenov, M.V.; Gadzhiumarov, R.G.; Tkhakakhova, A.K.; Chernov, T.I.; Ksenofontova, N.A.; Kutovaya, O.V. Assessment of the impact of no-till and conventional tillage technologies on the microbiome of southern agrochernozems. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, R.; Zydlik, Z.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Niewiadomska, A.; Kayzer, D. The Effect of Biofumigation on the Microbiome Composition in Replanted Soil in a Fruit Tree Nursery. Agronomy 2023, 13(10), 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soil and Creating Legends for Soils and creating Legends for Soil Maps. 4th edition. International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS) Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- Selyaninov, G.T. About climate agricultural estimation. Proceedings on Agricultural Meteorology 1928, 20, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Taparauskiene, L.; Miseckaite, O. Comparison of watermark soil moisture content with Selyaninov hydrothermal coefficient. Agrofor, 2017; 2(2), 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chmist-Sikorska, J.; Kępińska-Kasprzak, M.; Struzik, P. Agricultural drought assessment on the base of Hydro-thermal Coefficient of Selyaninov in Poland. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 2022, 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Bocianowski, J.; Sawkojć, S.; Wnuk, A. Call for more graphical elements in statistical teaching and consultancy. Biom. Lett. 2010, 47, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- VSN International Genstat for Windows, 23rd ed.; VSN International: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2023.

- Li, B.B.; Roley, S.S.; Duncan, D.S.; Guo, J.; Quensen, J.F.; Yu, H.-Q.; Tiedje, J.M. Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Increases Sensitivity of Soil Microbial Community to Seasonal Change Revealed by Ecological Network and Metagenome Analyses. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.H.; Gao, K.; Guo, Z.H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, G.L. Different Responses of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities to 3 Years of Biochar Amendment in an Alkaline Soybean Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 630418.

- Bao, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.Z.; Stegen, J.C.; Wu, M.; Chen, R.R.; Liu, W.J.; et al. Straw chemistry links the assembly of bacterial communities to decomposition in paddy soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2020, 148, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.R.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Wang, J.T.; Hu, H.W.; Yang, Z.M.; He, J.Z. New insights into the role of microbial community composition in driving soil respiration rates. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018, 118, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88(6), 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnkopp-Dirks, F.; Radl, V.; Kublik, S.; Gschwendtner, S.; Schloter, M.; Winkelmann, T. Dynamics of bacterial root endophytes of Malus domestica plants grown in field soils affected by apple replant disease. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 841558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, L.; He, N.; Gong, D.; Gao, H.; Ma, Z.; Fu, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, W. . Soil bacterial community as impacted by addition of rice straw and 649 biochar. Sci, Rep. 2021; 11, 22185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünger, W.; Jiang, X.; Müller, J.; Hurek, T.; Reinhold-Hurek, B. Novel cultivated endophytic Verrucomicrobia reveal deep-rooting traits of bacteria to associate with plants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Oliverio, A.M.; Brewer, T.E.; Benavent-González, A.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K.; Fierer, N. A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil. Science 2018, 359, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBruyn, J.M.; Nixon, L.T.; Fawaz, M.N.; Johnson, A.M.; Radosevich, M. Global Biogeography and Quantitative Seasonal Dynamics of Gemmatimonadetes in Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6295–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujakić, I.; Piwosz, K.; Koblížek, M. Phylum Gemmatimonadota and Its Role in the Environment. Microorganisms 2022, 10(1), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Zhu, R.; Chen, N.; Ding, L.; Chen, C. Vegetation richness, species identity and soil nutrients drive the shifts in soil bacterial communities during restoration process. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 1758–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Bai, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yin, Y. Variations of soil microbial communities accompanied by different vegetation restoration in an open-cut iron mining area. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Liu, X.; Lin, S.; Tan, J.; Pan, J.; Li, D.; Yang, H. The vertical distribution of bacterial and archaeal communities in the water and sediment of Lake Taihu. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 70, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Tang, X.; Hou, Q.; Li, T.; Xie, H.; Lu, Z.; & Wen, X. Response of soil organic carbon fractions to legume incorporation into cropping system and the factors affecting it: A global meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Joa, J.H.; Kang, S.S.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, M; Song, J.; Weon, H.Y. Different types of agricultural land use drive distinct soil bacterial communities. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 17418. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; He, P.; Guo, X.L.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.J. Fifteen-year no tillage of a Mollisol with residue retention indirectly affects topsoil bacterial community by altering soil properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelevtsova, L.E.; Sazykin, I.S.; Azhogina, T.N.; Sazykina, M.A. Influence of agricultural practices on bacterial community of cultivated soils. Agriculture 2022, 12(3), 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Mondal, R.; Khoshru, B.; Senapati, A.; Radha, T.K.; Mahakur, B.;... & Mohapatra, P.K.D. Actinobacteria-enhanced plant growth, nutrient acquisition, and crop protection: Advances in soil, plant, and microbial multifactorial interactions. Pedosphere, 2022; 32(1), 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A.; Overlöper, A.; Schlüter, J.P.; Reinkensmeier, J.; Robledo, M.; Giegerich, R.; Narberhaus, F.; Evguenieva-Hackenberg, E. Riboregulation in plant-associated α-proteobacteria. RNA Biology 2014, 11(5), 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klūga, A.; Dubova, L.; Alsiņa, I.; Rostoks, N. Alpha-, gamma-and beta-proteobacteria detected in legume nodules in Latvia, using full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B 2023, 73(1), 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batut, J.; Andersson, S.G.; O’Callaghan, D. The evolution of chronic infection strategies in the α-proteobacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2(12), 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, R.; Dharumadurai, D.; Manogaran, G.P. An introduction to actinobacteria. In: Actinobacteria-basics and biotechnological applications. IntechOpen, 2016.

- Mokni-Tlili, S.; Mehri, I.; Ghorbel, M.; Hassen, W.; Hassen, A.; Jedidi, N.; Hamdi, H. Community-level genetic profiles of actinomycetales in long-term biowaste-amended soils. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 2607–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic-Mulec, I.; Stefanic, P.; van Elsas, J.D. Ecology of Bacillaceae. The bacterial spore: From molecules to systems 2016, 59–85. [CrossRef]

- Masson-Boivin, C.; Giraud, E.; Perret, X.; Batut, J. Establishing nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with legumes: how many rhizobium recipes? Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17(10), 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, F.; Yao, H. Response of symbiotic and asymbiotic nitrogen-fixing microorganisms to nitrogen fertilizer application. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anavadiya, B.; Chouhan, S.; Saraf, M.; Goswami, D. Exploring Endophytic Actinomycetes: A Rich Reservoir of Diverse Antimicrobial Compounds for Combatting Global Antimicrobial Resistance. The Microbe 2024, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platamone, G.; Procacci, S.; Maccioni, O.; Borromeo, I.; Rossi, M.; Bacchetta, L.; Forni, C. Arthrobacter sp. inoculation improves cactus pear growth, quality of fruits, and nutraceutical properties of cladodes. Curr. Microbiol. 2023; 80(8), 266. [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri, G.; Kim, I.; Kang, M.; So, Y.; Kim, J.; Seo, T. An isolated Arthrobacter sp. enhances rice (Oryza sativa L.) plant growth. Microorganisms, 2022; 10(6), 1187. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, P.; Ramaswamy, V.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Betts, R.; Fahey, D.W.; Haywood, J.; Lean, J.; Lowe, D.C.; Myhre, G.; Nganga, J.; Prinn, R.; Raga, G.; Schulz, M.; Van Dorland, R. Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Park, D.; Kim, H.; Yoon, S. Nitrous oxide reduction by an obligate aerobic bacterium, Gemmatimonas aurantiaca strain T-27. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83(12), e00502-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Month | |||||||||||||

| Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sep | |||||||||

| 1st ten days | 0.00 | 1.73 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.65 | 1.75 | ||||||||

| 2nd ten days | 0.96 | 4.71 | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.50 | 0.62 | ||||||||

| 3rd ten days | 0.52 | 1.67 | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.22 | 1.94 | ||||||||

| month | 0.45 | 2.56 | 0.13 | 1.05 | 0.44 | 1.47 | ||||||||

| >3.0 | 2.6-3.0 | 2.1-2.6 | 1.7-2.1 | 1.4-1.7 | 1.1-1.4 | 0.8-1.1 | 0.4-0.8 | <0.4 | ||||||

| Extremely humid | Very humid | Humid | Quite humid | Optimum | Quite dry | Dry | Very dry | Extremely dry | ||||||

| Classification | Experiment variants | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| sample ‘0’ plantless, fallow buffer zone of the field experiment | conventional tillage | reduced tillage | strip tillage, | no tillage, | |

| Total reads [%] | |||||

| Bacteria | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Unclassified at Kingdom level | 99.96% | 99.97% | 99.98% | 99.96% | 99.98% |

| Archaea | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).