Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Natural rubber, a renewable material with unique properties, is crucial for various products on the modern market. Crepe rubber, a versatile form of natural rubber, is widely used in numerous applications, including footwear soles, medical devices, automotive parts, adhesives, sports equipment, industrial components, musical instruments, and recreational products. Sri Lanka holds a prominent position as a leading producer of premium-quality crepe rubber but faces environmental challenges in its production process. Since previous life cycle assessments (LCA) in the rubber industry are inadequate to capture overall environmental impact, the present study attempted to address the gaps by conducting a detailed LCA of a Sri Lankan crepe rubber factory, incorporating a novel index termed Trade-off valuation index (TOVI). The research revealed that fertilizer, water, and electricity use contribute most significantly to crepe rubber production's environmental impact. To mitigate these impacts, four key improvement options were identified and evaluated through scenario analysis: 1) enhancing fertilizer efficiency, 2) repairing leaky joints and valves, 3) implementing a water reuse system, and 4) installing solar panels. The integration of TOVI allowed for the prioritization of these options, providing actionable insights for industry stakeholders. This study paves the way for targeted interventions to enhance the sustainability of the natural rubber industry by balancing economic viability with environmental stewardship.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

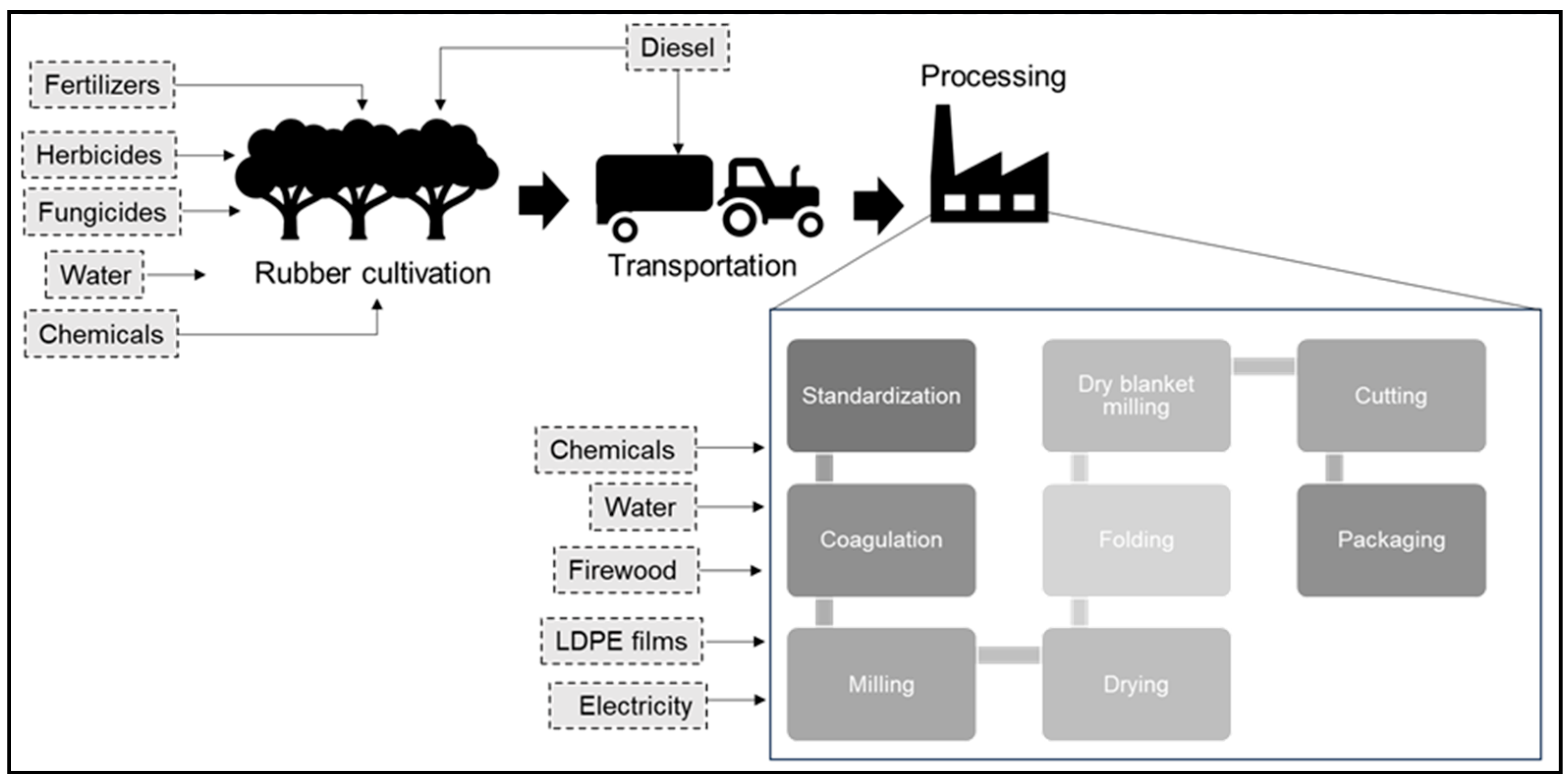

2.1. Details of Rubber Cultivation

2.2. Crepe Rubber Production Process

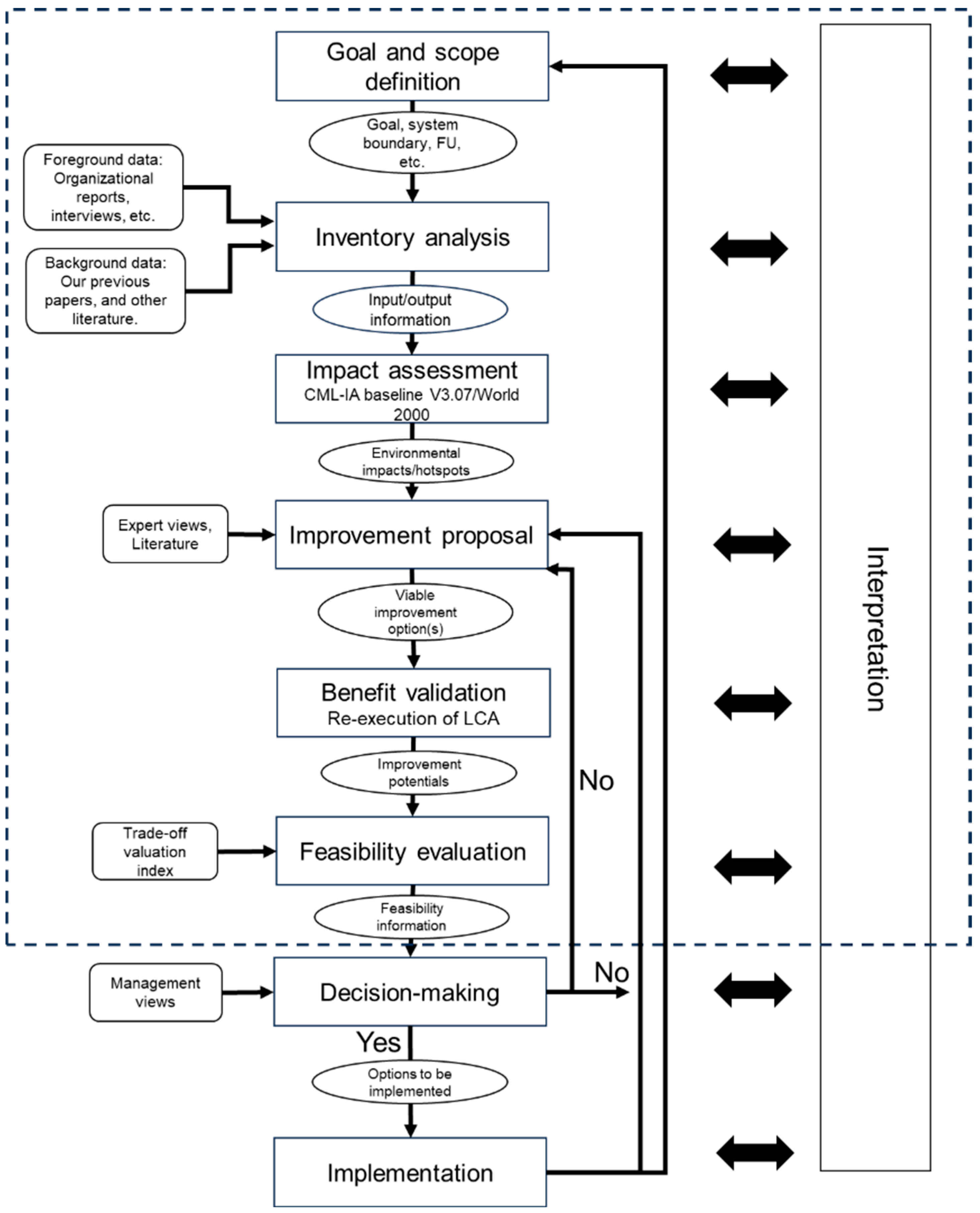

2.3. The Framework of the Study

2.3.1. Impact Evaluation

- 1.

- Goal and scope definition

- 2.

- Inventory Analysis

- 3.

- Data collection for rubber cultivation

- 4.

- Data Collection for Crepe Rubber Processing

- 5.

- Impact assessment

- 6.

- Interpretation

- 7.

- Sensitivity analysis

2.3.2. Improvement Proposal

2.3.3. Benefit Validation

2.3.4. Feasibility Analysis

2.3.5. Trade-Off Valuation Index

3. Results and Discussion

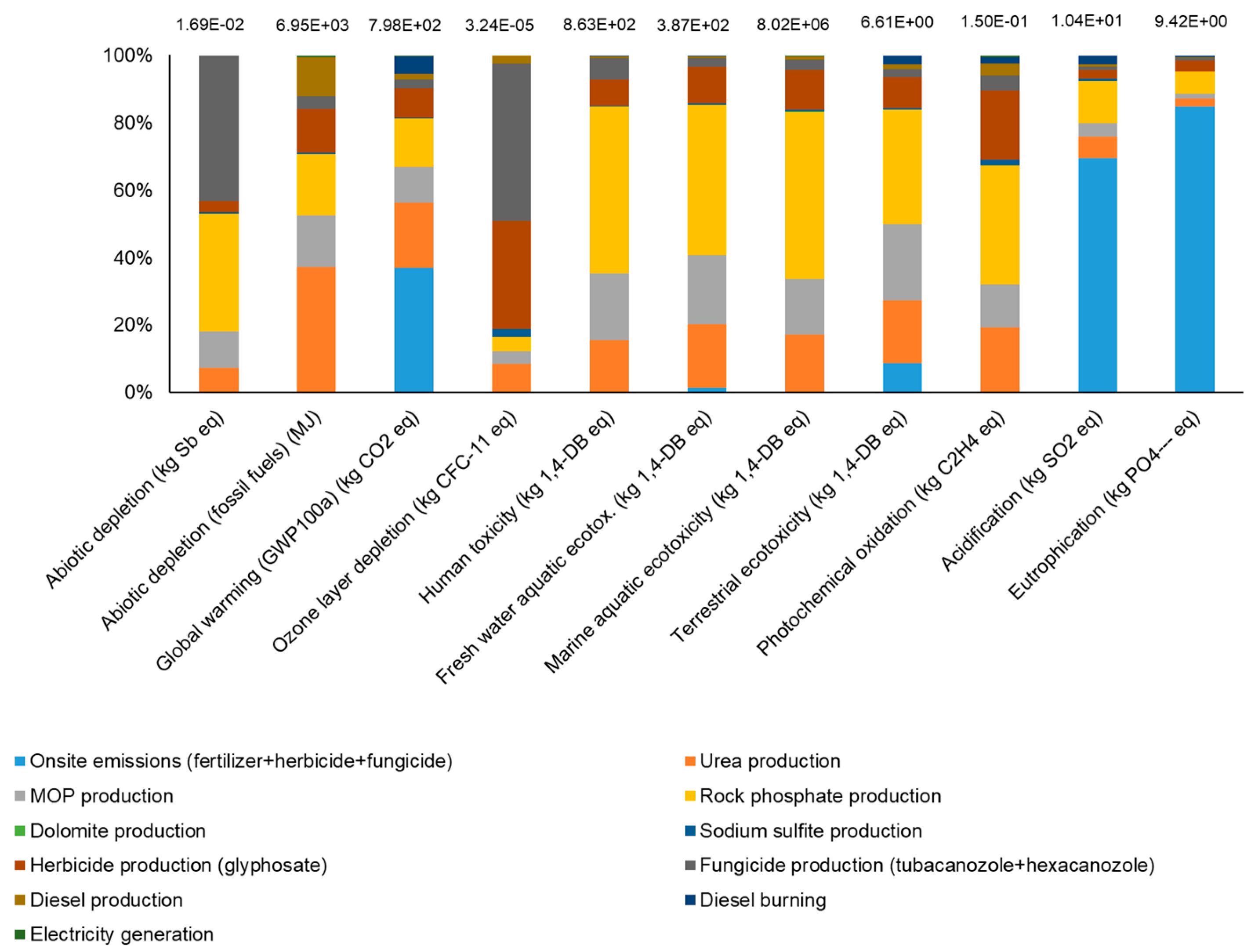

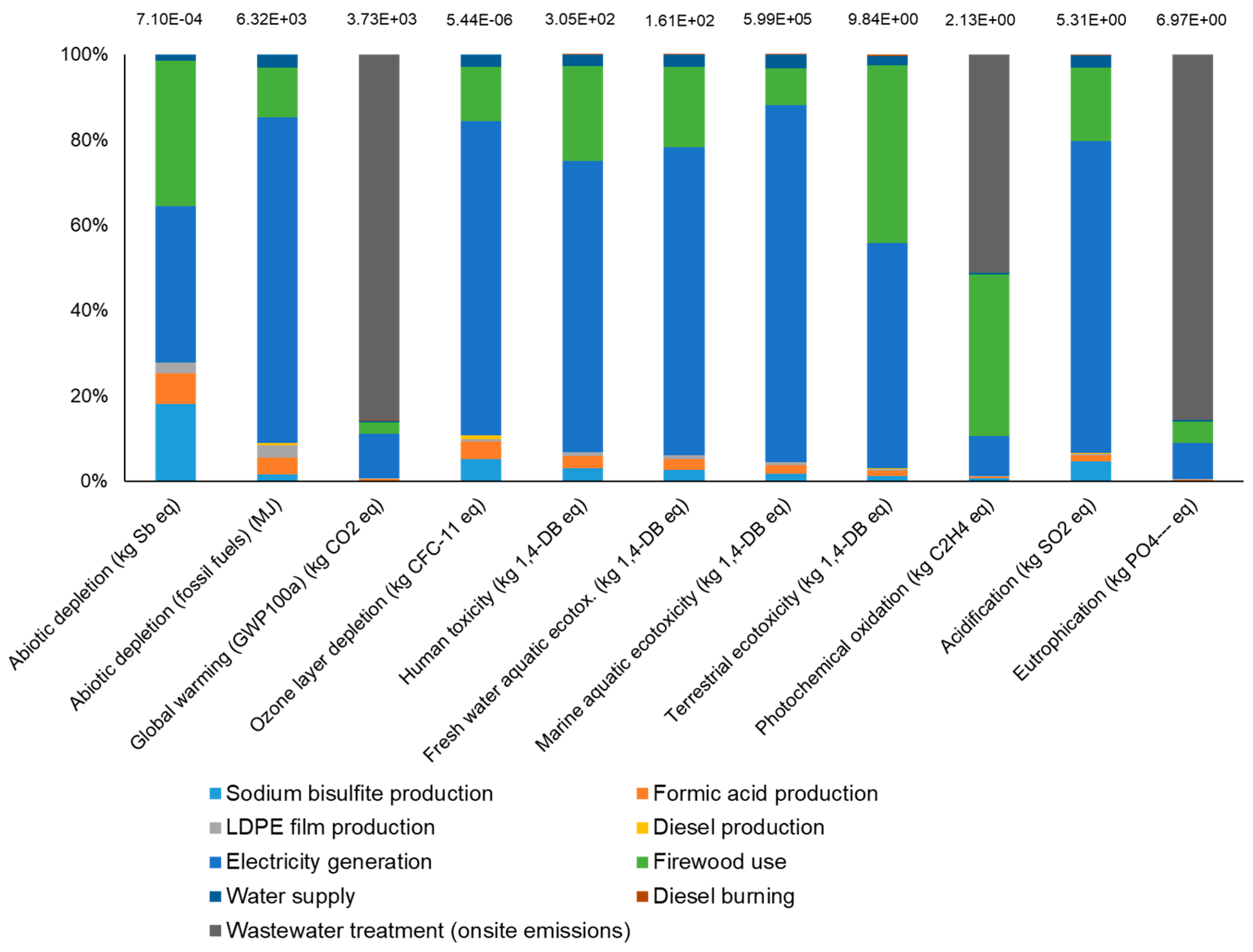

3.1. Impact Evaluation Results

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

3.3. Improvement Options Proposal

3.3.1. Option 1: Reduction of Fertilization

3.3.2. Option 2: Repair Leaky Joints and Valves and Fit Water Flow Meters

3.3.3. Option: 3: Installation of Industrial Water Recirculation Cooling System

3.3.4. Option-4: Installation of Solar Panels

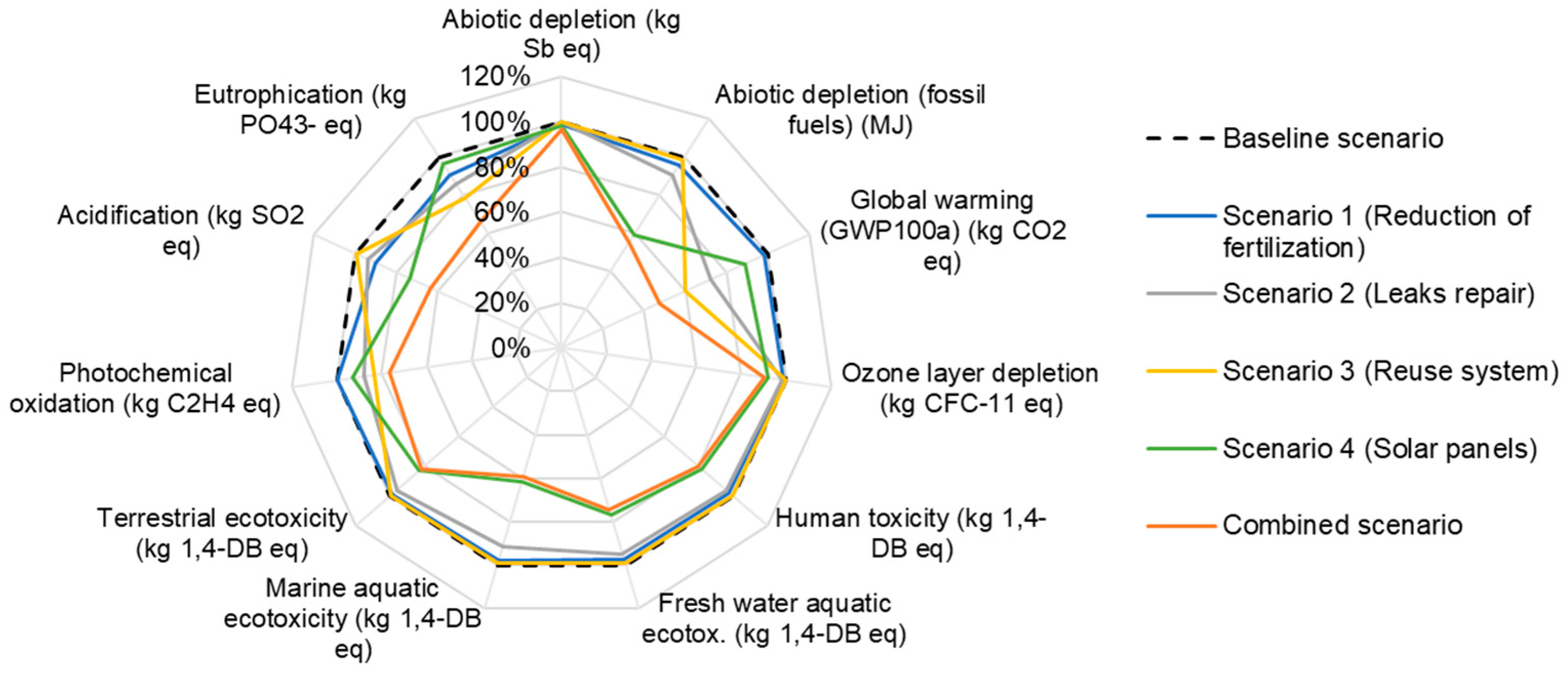

3.4. Evaluation of Potential Improvements

3.4.1. Option 1: Reduce fertilization

3.4.2. Option-2: Repair Leaky Joints and Valves and Fit Water Flow Meters

3.4.3. Option: 3: Installation of Industrial Water Recirculation Cooling System

3.4.4. Option-4: Installation of Solar Panels

3.4.5. Combined Scenario

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IHS Markit Rubber, Natural - Chemical Economics Handbook Available online: https://www.ihs.com/products/natural-rubber-chemical-economics-handbook.html (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Tillekeratne, L.M.K.; Nugawela, A.; Seneviratne, W.M.G. Handbook of Rubber; Vishva Lekha Printers: Ratmalana, 2003.

- Bengtsen, P. Behind the Rubber Label; 2013.

- Sri Lanka Rubber Secretariat Sri Lanka Rubber Industry Development Master Plan 2017-2026; Battaramulla, 2017.

- Dunuwila, P.; V.H.L. Rodrigo; Goto, N. SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT IN NATURAL RUBBER INDUSTRY: CASE OF A SRI LANKAN CREPE RUBBER FACTORY. In Proceedings of the International Proceedings of IRC 2017; Jakarta, 2017; pp. 550–571.

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Sustainability of Natural Rubber Processing Can Be Improved: A Case Study with Crepe Rubber Manufacturing in Sri Lanka. Resour Conserv Recycl 2018, 133, 417–427. [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena, S. PROPOSED SOLAR DRYING SYSTEMS FOR CREPE RUBBER DRYING. Bulletin of the Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka 2010, 51, 50–60.

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Sustainability of Natural Rubber Processing Can Be Improved: A Case Study with Crepe Rubber Manufacturing in Sri Lanka. Resour Conserv Recycl 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Financial and Environmental Sustainability in Manufacturing of Crepe Rubber in Terms of Material Flow Analysis, Material Flow Cost Accounting and Life Cycle Assessment. J Clean Prod 2018, 182. [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P. Integration of Process Analysis and Decision-Making Tools for the Sustainability Improvements in Raw Rubber Manufacture, Toyohashi University of Technology: Toyohashi, 2019.

- Peiris, S. Experiences of Cleaner Production Ewlementation in Rubber Industry and Potential For Future in Sri Lanka; 1997.

- UNESCAP Country Study on Sri Lanka Using Global Value Chain Analysis: THE INDUSTRIAL RUBBER AND ELECTRONIC PRODUCTS SECTORS; 2011.

- Edirisinghe, J. Community Pressure and Environmental Compliance: Case of Rubber Processing in Sri Lanka. Journal of Environmental Professionals Sri Lanka 2013, 1. [CrossRef]

- Massoudinejad, M.; Mehdipour-Rabori, M.; Dehghani, M.H. Treatment of Natural Rubber Industry Wastewater through a Combination of Physicochemical and Ozonation Processes Citation: Massoudinejad M, Mehdipour-Rabori M, Dehghani MH. Treatment of Natural Rubber Industry Wastewater through a Combination of Physicoch. J Adv Environ Health Res 2015, 3, 242–249.

- Kumara, P.R.; Munasinghe, E.S.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Karunaratna, A.S. Carbon Footprint of Rubber/Sugarcane Intercropping System in Sri Lanka: A Case Study. Procedia Food Sci 2016, 6, 298–302. [CrossRef]

- Tekasakul, S.; Tantichaowanan, M.; Otani, Y.; Kuruhongsa, P.; Tekasakul, P. Removal of Soot Particles in Rubber Smoking Chamber by Electrostatic Precipitator to Improve Rubber Sheet Color; 2006; Vol. 6.

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Improving Financial and Environmental Sustainability in Concentrated Latex Manufacture. J Clean Prod 2020, 255. [CrossRef]

- Guinee, J.B. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2002, 7, 311–313. [CrossRef]

- The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) International Standard ISO 14040; 2006.

- Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka Fertilizer for Rubber; Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka, 2016.

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Assessing the Financial and Environmental Sustainability in Raw Rubber Processing; a Case Study with Ribbed Smoked Sheet Manufacture in Sri Lanka. Indonesian Journal of Life Cycle Assessment and Sustainability 2018, 2.

- The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 14040:2006(En), Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Principles and Framework; Switzerland, 2006.

- Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka Available online: http://www.rrisl.lk/sub_pags/statistics.html (accessed on 10 May 2016).

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Daigo, I.; Goto, N. Social Sustainability of Raw Rubber Production: A Supply Chain Analysis under Sri Lankan Scenario. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15, 11623. [CrossRef]

- Birnbach, M.; Lehmann, A.; Naranjo, E.; Finkbeiner, M. A Condom’s Footprint - Life Cycle Assessment of a Natural Rubber Condom. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2020, 25, 964–979. [CrossRef]

- Jawjit, W.; Pavasant, P.; Kroeze, C.; Tuffey, J. Evaluation of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Condom Production in Thailand. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 2021, 18, 89–114. [CrossRef]

- Khanali, M.; Mousavi, S.A.; Sharifi, M.; Keyhani Nasab, F.; Chau, K. wing Life Cycle Assessment of Canola Edible Oil Production in Iran: A Case Study in Isfahan Province. J Clean Prod 2018, 196, 714–725. [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Daigo, I.; Goto, N. Social Sustainability of Raw Rubber Production: A Supply Chain Analysis under Sri Lankan Scenario. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 11623 2023, 15, 11623. [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Nagara, T.; Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; 2006.

- Gamaralalage, D.; Sawai, O.; Nunoura, T. Effectiveness of Available Wastewater Treatment Facilities in Rubber Production Industries in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development 2016, 7, 940–945. [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Rebitzer, G. The Ecoinvent Database System: A Comprehensive Web-Based LCA Database. J Clean Prod 2005, 13, 1337–1343. [CrossRef]

- PRé Sustainability About SimaPro - SimaPro Available online: https://simapro.com/about/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Daigo, I.; Goto, N. Unveiling the Environmental Impacts of Concentrated Latex Manufacturing in Sri Lanka through a Life Cycle Assessment. Resources 2024, 13, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mahath, C.S.; Mophin Kani, K.; Dubey, B. Gate-to-Gate Environmental Impacts of Dairy Processing Products in Thiruvananthapuram, India. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar Choubey, V.; Deepak, A.; Gedam, V. V.; Raut, R.D. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Dairy Processing Industry: A Case Study of North India. J Clean Prod 2021, 326, 129331. [CrossRef]

- Humbert, S.; De Schryver, A.; Bengoa, X.; Margni, M.; Jolliet, O. IMPACT 2002+: User Guide; 2012.

- Goedkoop, M. Eco-Indicator 95; 1995.

- EPD® General Programme Instructions for the International EPD® System. Version 2.5, Dated 2015-05-11; 2015.

- Gonçalves, J.; Freitas, J.; Fernandes, I.; Silva, P. Microalgae as Biofertilizers: A Sustainable Way to Improve Soil Fertility and Plant Growth. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 12413 2023, 15, 12413. [CrossRef]

- Jawjit, W.; Kroeze, C.; Rattanapan, S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Rubber Industry in Thailand. J Clean Prod 2010, 18, 403–411. [CrossRef]

- NewEarth B SHDB Available online: http://www.socialhotspot.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Sganzerla, W.G.; Rosa, R.G. da; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Castro, L.E.N.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Techno-Economic Assessment of On-Site Production of Biomethane, Bioenergy, and Fertilizer from Small-Scale Anaerobic Digestion of Jabuticaba By-Product. Methane 2023, Vol. 2, Pages 113-128 2023, 2, 113–128. [CrossRef]

- Nesterenko, N.; Medeiros-Costa, I.C.; Clatworthy, E.B.; Cruchade, H.; Konnov, S. V.; Dath, J.P.; Gilson, J.P.; Mintova, S. Methane-to-Chemicals: A Pathway to Decarbonization. Natl Sci Rev 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

| Emission source | Emission factor | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| N2O direct emissions from fertilizer use (to air) | 0.1 | kg N2O–N/kg N use |

| N2O indirect emission after N leaching and runoff (to soil) | 0.00225 | kg N2O–N/kg N use |

| N2O indirect emission after emission of fertilizer N as NOx and NH3 (to air) | 0.001 | kg N2O–N/kg N use |

| CO2 direct emissions from Urea (to air) | 0.2 | kg CO2–C/kg urea |

| NH3 emissions from fertilizer use (to air) | 0.1 | kg NH3–N/kg N use |

| Direct NOx from fertilizer use (to air) | 0.21 | kg NOx/ kg N2O from fertilizers |

| NO3- emissions from fertilizer use (to soil) | 0.3 | kg NO3-–N/kg N use |

| P emissions to water | 0.05 | kg P emissions/ kg P use |

| Type of conversion | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| kg CO2-C to kg CO2 | 44/12 |

| kg N2O-N to kg N2O | 44/28 |

| kg NH3-N to kg NH3 | 17/14 |

| kg NO3-N to kg NO3 | 62/14 |

| kg P2O5 to kg phosphorus | 62/142 |

| kg CO2-C to kg CO2 | 44/12 |

| Activity | Amount (kg unless mentioned) |

|---|---|

| Inputs | data |

| Urea | 79.36 |

| Rock phosphate | 70.45 |

| Muriate of potash (MOP) | 77.34 |

| Dolomite | 1.33 |

| Kieserite | 0.17 |

| Diesel for tillage | 13.68 L |

| Sodium sulfite | 1.38 |

| Herbicide (glyphosate) | 5.21 |

| Fungicides (tebuconazole) | 0.62 |

| Fungicides (hexaconazole) | 0.62 |

| Water (plantation protection) | 560 |

| Outputs (onsite) | |

| Field latex (dry rubber basis) | 1000 |

| N2O (to air) | 0.76 |

| NH3 (to air) | 3.99 |

| CO2 (to air) | 58.20 |

| NOx (to air) | 0.03 |

| P (to water) | 0.20 |

| Glyphosate (to soil) | 5.21 |

| Tebuconazole (to soil) | 0.62 |

| Hexaconazole (to soil) | 0.62 |

| Activity | Amount (kg unless mentioned) |

|---|---|

| Inputs | |

| Diesel for latex transportation | 167.18 |

| Field latex (dry/wet basis) | 1136.36/3130.23 |

| Sodium bisulfite | 4.90 |

| Formic acid | 4.30 |

| Bleaching agent | 1.22 |

| Electricity | 616.85 kWh |

| Firewood | 447.44 |

| LDPE film | 1.90 |

| Water | 87034.09 |

| Outputs | |

| Crepe rubber (white) | 1000 |

| Yellow crepe | 136.36 |

| Rubber loss | 49.40 |

| Wastewater | 88437.61 |

| Ash | 5.19 |

| Eminent emissions (on-site) | Eminent emissions (on-site) |

| CO2 (biogenic) (to air) | 1490.88 |

| CO2 (fossil) (to air) | 1.56 |

| CH4 (biogenic) (to air) | 108.74 |

| N2O (to air) | 0.44 |

| NOx (to air) | 1.24 |

| CO (biogenic) (to air) | 45.64 |

| CO (fossil) (to air) | 2.94 g |

| SO2 (to air) | 0.51 g |

| NO3- (to water) | 44.10 g |

| NMVOC, non-methane volatile organic compounds (to air) | 6.39 |

| Particulates, < 2.5 um (to air) | 1.37 |

| COD (to water) | 35.40 |

| BOD (to water) | 5.31 |

| NH4+ (to water) | 1.86 |

| Impact category | Unit | Impact value |

|---|---|---|

| Abiotic depletion | kg Sb eq | 1.76E-02 |

| Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels) | MJ | 1.33E+04 |

| Global warming (GWP100a) | kg CO2 eq | 4.53E+03 |

| Ozone layer depletion (ODP) | kg CFC-11 eq | 3.78E-05 |

| Human toxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 1.17E+03 |

| Fresh water aquatic ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 5.48E+02 |

| Marine aquatic ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 1.40E+06 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 1.64E+01 |

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 eq | 2.28E+00 |

| Acidification | kg SO2 eq | 1.58E+01 |

| Eutrophication | kg PO4--- eq | 1.64E+01 |

| Impact category | Unit | CML (Baseline) | IMPACT 2002+ | Eco-indicator 95 | EPD (2013) |

| Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 4.525×103 | 1.806×103 | 2.299×103 | 4.531×103 |

| Ozone layer depletion | kg CFC-11 eq | 3.780×10-5 | 3.780×10-5 | 4.770×10-5 | 3.780×10-5 |

| Acidification | kg SO2 eq | 15.755 | 8.730 | 8.642 | 15.755 |

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 eq | 2.280 | 4.636 | 4.032 | 2.280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).