Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Abiotic and Biotic Stresses

3. Cross-Tolerance

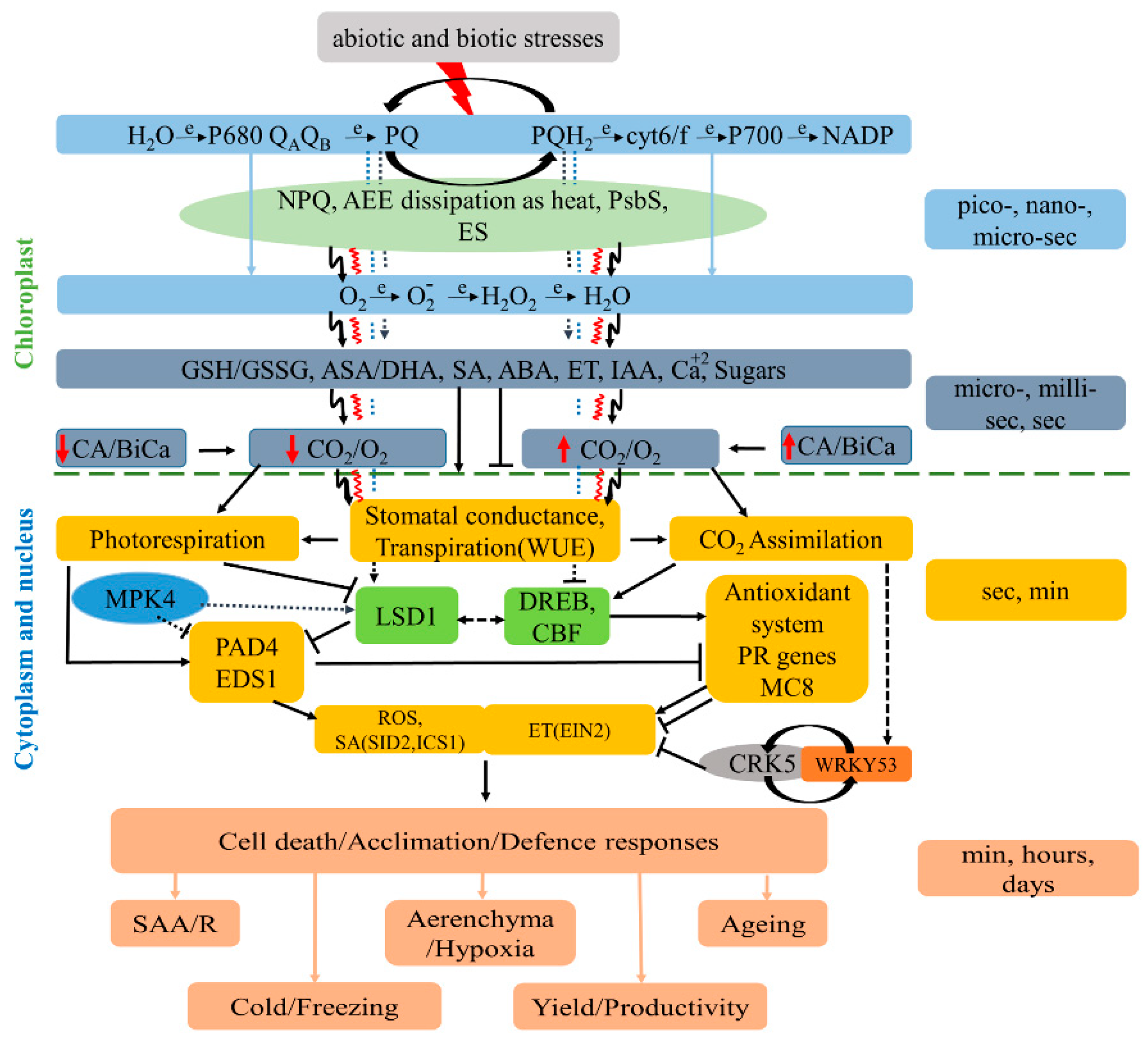

4. Signaling Networks During Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

4.1. Transcription Factors Role During Abiotic and Biotic Stress

4.2. Reactive Oxygen Species Role During Abiotic and Biotic Stress Condition

4.3. Hormonal Response During Abiotic and Biotic Stress

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, P.; Li, R.; Chen, Z.-H.; Wang, Y. Stomata at the Crossroad of Molecular Interaction between Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1031891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Prueger, J.H. Temperature Extremes: Effect on Plant Growth and Development. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2015, 10, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; Food & Agriculture Org., 2022; Vol. 2022; ISBN 92-5-136499-0. [CrossRef]

- Fedoroff, N.V.; Battisti, D.S.; Beachy, R.N.; Cooper, P.J.; Fischhoff, D.A.; Hodges, C.; Knauf, V.C.; Lobell, D.; Mazur, B.J.; Molden, D. Radically Rethinking Agriculture for the 21st Century. science 2010, 327, 833–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilby, R.; Whitehead, P.; Wade, A.; Butterfield, D.; Davis, R.; Watts, G. Integrated Modelling of Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources and Quality in a Lowland Catchment: River Kennet, UK. J. Hydrol. 2006, 330, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, J.S. Plant Productivity and Environment. Science 1982, 218, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry, P.R. Biochemistry & Molecular Biology of Plants. BB Buchanan, W. Gruissem and RL Jones (Eds), 2000. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Vij, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Emerging Trends in the Functional Genomics of the Abiotic Stress Response in Crop Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurbriggen, M.D.; Hajirezaei, M.-R.; Carrillo, N. Engineering the Future. Development of Transgenic Plants with Enhanced Tolerance to Adverse Environments. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2010, 27, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, S.; SZECHYŃSKA-HEBDA, M.; Wituszyńska, W.; Burdiak, P. Light Acclimation, Retrograde Signalling, Cell Death and Immune Defences in Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Bajwa, A.A.; Nazir, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Farooq, A.; Zohaib, A.; Sadia, S.; Nasim, W.; Adkins, S.; Saud, S. Crop Production under Drought and Heat Stress: Plant Responses and Management Options. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, P.S.; Rane, J.; Pasala, R.K. Abiotic Stresses in Agriculture: An Overview. Abiotic Stress Manag. Resilient Agric. 2017, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.J.; Czarnocka, W.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Mittler, R.; Karpiński, S. Biotechnological Potential of LSD1, EDS1, and PAD4 in the Improvement of Crops and Industrial Plants. Plants 2019, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawroński, P.; Burdiak, P.; Scharff, L.B.; Mielecki, J.; Górecka, M.; Zaborowska, M.; Leister, D.; Waszczak, C.; Karpiński, S. CIA2 and CIA2-LIKE Are Required for Optimal Photosynthesis and Stress Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2021, 105, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wituszyńska, W.; Ślesak, I.; Vanderauwera, S.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Kornaś, A.; Van Der Kelen, K.; Mühlenbock, P.; Karpińska, B.; Maćkowski, S.; Van Breusegem, F.; Karpiński, S. Lesion Simulating Disease1, Enhanced Disease Susceptibility1, and Phytoalexin Deficient4 Conditionally Regulate Cellular Signaling Homeostasis, Photosynthesis, Water Use Efficiency, and Seed Yield in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-Mediated Abiotic Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Friend or Foe? Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Scavenging and Signaling in Plant Response to Environmental Stresses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Species Signalling in Plant Stress Responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhlenbock, P.; Szechynska-Hebda, M.; Płaszczyca, M.; Baudo, M.; Mateo, A.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Parker, J.E.; Karpinska, B.; Karpiński, S. Chloroplast Signaling and LESION SIMULATING DISEASE1 Regulate Crosstalk between Light Acclimation and Immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2339–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Kruk, J.; Górecka, M.; Karpińska, B.; Karpiński, S. Evidence for Light Wavelength-Specific Photoelectrophysiological Signaling and Memory of Excess Light Episodes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

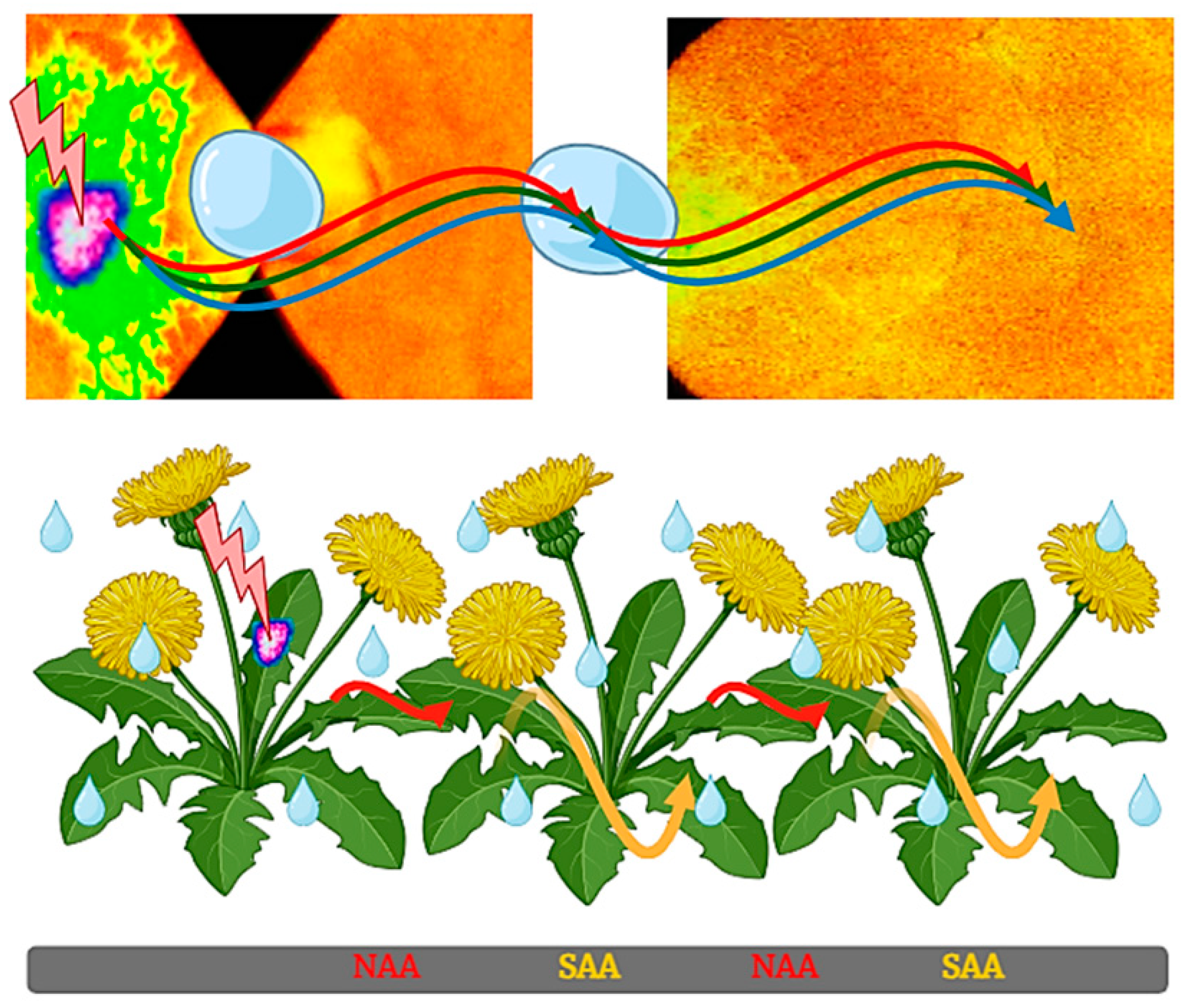

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Witoń, D.; Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R.; Karpiński, S.M. Aboveground Plant-to-Plant Electrical Signaling Mediates Network Acquired Acclimation. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3047–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Białasek, M.; Barczak-Brzyżek, A.; Kulasek, M.; Mielecki, J.; Kozłowska-Makulska, A.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. Photosystem II 22kDa Protein Level-a Prerequisite for Excess Light-inducible Memory, Cross-tolerance to UV-C and Regulation of Electrical Signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation in Response to Osmotic Stress in Plants. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R. Abiotic Stress, the Field Environment and Stress Combination. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Bashir, T.; Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Systems Biology Approach in Plant Abiotic Stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 121, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorchev, L.; Seal, C.E.; Kranner, I.; Odjakova, M. A Central Role for Thiols in Plant Tolerance to Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7405–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulasek, M.; Bernacki, M.J.; Ciszak, K.; Witoń, D.; Karpiński, S. Contribution of PsbS Function and Stomatal Conductance to Foliar Temperature in Higher Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kul, R.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Ors, S.; Yildirim, E. How Abiotic Stress Conditions Affects Plant Roots. In Plant roots; IntechOpen, 2020 ISBN 1-83968-276-0. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.; Shin, J.; Davis, S.J. Abiotic Stress and the Plant Circadian Clock. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, A.; Rafudeen, M.; Golldack, D. Physiological Aspects of Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in Plants: Protection against Abiotic Stress. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziogas, V.; Tanou, G.; Filippou, P.; Diamantidis, G.; Vasilakakis, M.; Fotopoulos, V.; Molassiotis, A. Nitrosative Responses in Citrus Plants Exposed to Six Abiotic Stress Conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 68, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrose, M.; Kane, N.C.; Mayrose, I.; Dlugosch, K.M.; Rieseberg, L.H. Increased Growth in Sunflower Correlates with Reduced Defences and Altered Gene Expression in Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stress. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 4683–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.J.; Makarevitch, I.; Noshay, J.; Burghardt, L.T.; Hirsch, C.N.; Hirsch, C.D.; Springer, N.M. Natural Variation for Gene Expression Responses to Abiotic Stress in Maize. Plant J. 2017, 89, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P. Plant Abiotic Stress Responses and microRNAs. Adv. Agric. 2020, 119–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Adams, K.L. Differential Contributions to the Transcriptome of Duplicated Genes in Response to Abiotic Stresses in Natural and Synthetic Polyploids. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khanna, K. Photosynthetic Response of Plants under Different Abiotic Stresses: A Review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusaczonek, A.; Czarnocka, W.; Kacprzak, S.; Witoń, D.; Ślesak, I.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. Role of Phytochromes A and B in the Regulation of Cell Death and Acclimatory Responses to UV Stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 6679–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdais, G.; Burdiak, P.; Gauthier, A.; Nitsch, L.; Salojärvi, J.; Rayapuram, C.; Idänheimo, N.; Hunter, K.; Kimura, S.; Merilo, E. Large-Scale Phenomics Identifies Primary and Fine-Tuning Roles for CRKs in Responses Related to Oxidative Stress. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdiak, P.; Mielecki, J.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. The CRK5 and WRKY53 Are Conditional Regulators of Senescence and Stomatal Conductance in Arabidopsis. Cells 2022, 11, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wituszyńska, W.; SZECHYŃSKA-HEBDA, M.; Sobczak, M.; Rusaczonek, A.; KOZŁOWSKA-MAKULSKA, A.; Witoń, D.; Karpiński, S. LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 and ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 Differentially Regulate UV-C-induced Photooxidative Stress Signalling and Programmed Cell Death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gechev, T.; Petrov, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Abiotic Stress in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.S.; Sidhu, G.P.S. Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Stress in Wheat. Wheat Prod. Chang. Environ. Responses Adapt. Toler. 2019, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Modi, P.; Dave, A.; Vijapura, A.; Patel, D.; Patel, M. Effect of Abiotic Stress on Crops. Sustain. Crop Prod. 2020, 3, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.-W.; Li, C.; Bai, T.-H.; Wang, P. Nutrient Use Efficiency of Plants under Abiotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1179842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, G. Molecular Approaches to Nutrient Uptake and Cellular Homeostasis in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Plant Nutr. Abiotic Stress Toler. 2018, 525–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfagón, D.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Rambla, J.L.; Granell, A.; de Ollas, C.; Bassham, D.C.; Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I. γ-Aminobutyric Acid Plays a Key Role in Plant Acclimation to a Combination of High Light and Heat Stress. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 2026–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. Plant Abiotic Stress Challenges from the Changing Environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, S.; Senizza, B.; Araniti, F.; Lewin, S.; Wende, S.; Lucini, L. A Multi-Omics Approach to Unravel the Interaction between Heat and Drought Stress in the Arabidopsis thaliana Holobiont. Authorea Prepr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Khobra, R.; Masthigowda, M.H.; Dohrey, P.; Wadhwa, Z.; Deswal, K.; Singh, G.; Singh, G.P. Understanding Heat and Drought Stress Adaptation Mechanisms in Wheat: A Combined Approach. J. Cereal Res. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.R.; Belo, J.; Beeckman, T.; Barros, P.M.; Oliveira, M.M. The Combined Effect of Heat and Osmotic Stress on Suberization of Arabidopsis Roots. Cells 2022, 11, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Guzman, M.; Cellini, F.; Fotopoulos, V.; Balestrini, R.; Arbona, V. New Approaches to Improve Crop Tolerance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresselhaus, T.; Hückelhoven, R. Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Crop Plants. Agronomy 2018, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebe, M.C.; Babalola, O.O. The Impact of Microbes in the Orchestration of Plants’ Resistance to Biotic Stress: A Disease Management Approach. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Yu, D.; Reiter, R.J. Phytomelatonin: An Emerging Regulator of Plant Biotic Stress Resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Talbot, N.J. Investigating the Cell Biology of Plant Infection by the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 34, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreo-Jimenez, B.; Ruyter-Spira, C.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Lopez-Raez, J.A. Ecological Relevance of Strigolactones in Nutrient Uptake and Other Abiotic Stresses, and in Plant-Microbe Interactions below-Ground. Plant Soil 2015, 394, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, G.W.; Castiblanco, L.F.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, Q.; Yang, C. Bacterial Disease Management: Challenges, Experience, Innovation and Future Prospects: Challenges in Bacterial Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Lou, Y.-R.; Tzin, V.; Jander, G. Alteration of Plant Primary Metabolism in Response to Insect Herbivory. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, F.E.; Peiffer, M.; Tan, C.-W.; Stanley, B.A.; Stanley, A.; Wang, J.; Jones, A.G.; Hoover, K.; Rosa, C.; Luthe, D. Fall Armyworm-Associated Gut Bacteria Modulate Plant Defense Responses. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglom, P.; Ito, S.; Sunpapao, A. Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma asperellum T1 Mediate Antifungal Activity, Defense Response and Promote Plant Growth in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Fungal Ecol. 2020, 43, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Immune System. nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustérucci, C.; Aviv, D.H.; Holt III, B.F.; Dangl, J.L.; Parker, J.E. The Disease Resistance Signaling Components EDS1 and PAD4 Are Essential Regulators of the Cell Death Pathway Controlled by LSD1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Bhatia, D.; Mavi, G. Eighty Years of Gene-for-Gene Relationship and Its Applications in Identification and Utilization of R Genes. J. Genet. 2021, 100, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, H.; Curtis, C.; Fu, Z.Q. Go in for the Kill: How Plants Deploy Effector-Triggered Immunity to Combat Pathogens. Virulence 2014, 5, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Si, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, D. Action Mechanisms of Effectors in Plant-Pathogen Interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting Mechanisms of Defense against Biotrophic and Necrotrophic Pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2005, 43, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, K.K. Defensive Strategies of ROS in Plant–Pathogen Interactions. In Plant Pathogen Interaction; Springer, 2024; pp. 163–183. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.-N.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-Z.; Li, T.; Geng, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, W.; Tan, X.-L. Plant Disease Resistance-Related Signaling Pathways: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, W.; Liu, Y. Biotrophic Fungal Pathogens: A Critical Overview. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Glazebrook, J.; Katagiri, F. The Interplay between MAMP and SA Signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.P.; Eggermont, K.; Penninckx, I.A.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Vogelsang, R.; Cammue, B.P.; Broekaert, W.F. Separate Jasmonate-Dependent and Salicylate-Dependent Defense-Response Pathways in Arabidopsis Are Essential for Resistance to Distinct Microbial Pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 15107–15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, J.M.; Dangl, J.L. Signal Transduction in the Plant Immune Response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghozlan, M.H.; Eman, E.-A.; Tokgöz, S.; Lakshman, D.K.; Mitra, A. Plant Defense against Necrotrophic Pathogens. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 2122–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. Intracellular Redox Compartmentation and ROS-Related Communication in Regulation and Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, A.; Mühlenbock, P.; Rustérucci, C.; Chang, C.C.-C.; Miszalski, Z.; Karpinska, B.; Parker, J.E.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Karpinski, S. LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 Is Required for Acclimation to Conditions That Promote Excess Excitation Energy. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2818–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawroński, P.; Witoń, D.; Vashutina, K.; Bederska, M.; Betliński, B.; Rusaczonek, A.; Karpiński, S. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 4 Is a Salicylic Acid-Independent Regulator of Growth but Not of Photosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Puthur, J.T. Seed Priming as a Cost Effective Technique for Developing Plants with Cross Tolerance to Salinity Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Arora, R. Dynamics of the Antioxidant System during Seed Osmopriming, Post-Priming Germination, and Seedling Establishment in Spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramegowda, V.; Da Costa, M.V.J.; Harihar, S.; Karaba, N.N.; Sreeman, S.M. Abiotic and Biotic Stress Interactions in Plants: A Cross-Tolerance Perspective. In Priming-mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in crop plants; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 267–302. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Missaoui, A.; Mahmud, K.; Presley, H.; Lonnee, M. Interaction between Grasses and Epichloë Endophytes and Its Significance to Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance and the Rhizosphere. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capiati, D.A.; País, S.M.; Téllez-Iñón, M.T. Wounding Increases Salt Tolerance in Tomato Plants: Evidence on the Participation of Calmodulin-like Activities in Cross-Tolerance Signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, J.D.; Dedido, D.B.; Volpato, L.A.; da Silva, A.P.; Lima, G.O.; Pinheiro, C.R.; da Silva, G.J. Cross Tolerance by Heat and Water Stress at Germination of Common Beans. Sci. Agrar. Parana. 2018, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.E.; Silveira, J.A. H2O2-Retrograde Signaling as a Pivotal Mechanism to Understand Priming and Cross Stress Tolerance in Plants. In Priming-mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in crop plants; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 57–78. [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Liu, Z.; Rochaix, J.-D.; Sun, X. Retrograde and Anterograde Signaling in the Crosstalk between Chloroplast and Nucleus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 980237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corti, F.; Festa, M.; Szabo, I. Mitochondria–Chloroplast Cross Talk: A Possible Role for Calcium and Reactive Oxygen Species? Bioelectricity 2023, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszak, K.; Kulasek, M.; Barczak, A.; Grzelak, J.; Maćkowski, S.; Karpiński, S. PsbS Is Required for Systemic Acquired Acclimation and Post-Excess-Light-Stress Optimization of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Decay Times in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e982018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witoń, D.; Sujkowska-Rybkowska, M.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Czarnocka, W.; Bernacki, M.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Karpiński, S. MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 4 Impacts Leaf Development, Temperature, and Stomatal Movement in Hybrid Aspen. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 2190–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, L.; Accotto, G.-P.; Bechtold, U.; Creissen, G.; Funck, D.; Jimenez, A.; Kular, B.; Leyland, N.; Mejia-Carranza, J.; Reynolds, H. Evidence for a Direct Link between Glutathione Biosynthesis and Stress Defense Gene Expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2448–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peak, D.; West, J.D.; Messinger, S.M.; Mott, K.A. Evidence for Complex, Collective Dynamics and Emergent, Distributed Computation in Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilroy, S.; Białasek, M.; Suzuki, N.; Górecka, M.; Devireddy, A.R.; Karpiński, S.; Mittler, R. ROS, Calcium, and Electric Signals: Key Mediators of Rapid Systemic Signaling in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulheim, C.; Ågren, J.; Jansson, S. Rapid Regulation of Light Harvesting and Plant Fitness in the Field. Science 2002, 297, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromdijk, J.; Głowacka, K.; Leonelli, L.; Gabilly, S.T.; Iwai, M.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Improving Photosynthesis and Crop Productivity by Accelerating Recovery from Photoprotection. Science 2016, 354, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.P.; Burgess, S.J.; Doran, L.; Hansen, J.; Manukyan, L.; Maryn, N.; Gotarkar, D.; Leonelli, L.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Soybean Photosynthesis and Crop Yield Are Improved by Accelerating Recovery from Photoprotection. Science 2022, 377, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinski, S.; Reynolds, H.; Karpinska, B.; Wingsle, G.; Creissen, G.; Mullineaux, P. Systemic Signaling and Acclimation in Response to Excess Excitation Energy in Arabidopsis. science 1999, 284, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Irulappan, V.; Bagavathiannan, M.V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Impact of Combined Abiotic and Biotic Stresses on Plant Growth and Avenues for Crop Improvement by Exploiting Physio-Morphological Traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, P.; Pisipati, S.; Momčilović, I.; Ristic, Z. Independent and Combined Effects of High Temperature and Drought Stress during Grain Filling on Plant Yield and Chloroplast EF-Tu Expression in Spring Wheat. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2011, 197, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, S.M.; Scherm, H.; Chakraborty, S. Climate Change and Plant Disease Management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1999, 37, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seherm, H.; Coakley, S.M. Plant Pathogens in a Changing World. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2003, 32, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.; Riha, S.; DiTommaso, A.; DeGaetano, A. Climate Change and the Geography of Weed Damage: Analysis of US Maize Systems Suggests the Potential for Significant Range Transformations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 130, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziska, L.H.; Tomecek, M.B.; Gealy, D.R. Competitive Interactions between Cultivated and Red Rice as a Function of Recent and Projected Increases in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Breitsameter, L.; Gerowitt, B. Impact of Climate Change on Weeds in Agriculture: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveiller, E.; Singh, R.P.; Nicol, J.M. The Challenges of Maintaining Wheat Productivity: Pests, Diseases, and Potential Epidemics. Euphytica 2007, 157, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, M.; Lovelli, S.; Perniola, M.; Di Tommaso, T.; Ziska, L. The Role of Water Availability on Weed–Crop Interactions in Processing Tomato for Southern Italy. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B–Soil Plant Sci. 2013, 63, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, N.J.; Urwin, P.E. The Interaction of Plant Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: From Genes to the Field. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3523–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasch, C.M.; Sonnewald, U. Simultaneous Application of Heat, Drought, and Virus to Arabidopsis Plants Reveals Significant Shifts in Signaling Networks. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1849–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Shared and Unique Responses of Plants to Multiple Individual Stresses and Stress Combinations: Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Pandey, P.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Tailored Responses to Simultaneous Drought Stress and Pathogen Infection in Plants. Drought Stress Toler. Plants Vol 1 Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, V.S.; Paramanantham, A.; Ramegowda, V.; Mohan-Raju, B.; Udayakumar, M.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Transcriptome Analysis of Sunflower Genotypes with Contrasting Oxidative Stress Tolerance Reveals Individual-and Combined-Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance Mechanisms. PloS One 2016, 11, e0157522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissoudis, C.; van de Wiel, C.; Visser, R.G.; van der Linden, G. Enhancing Crop Resilience to Combined Abiotic and Biotic Stress through the Dissection of Physiological and Molecular Crosstalk. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, D.D.; Zavala, J.A.; Zhu, J.; Clough, S.J.; Ort, D.R.; DeLUCIA, E.H. Biotic Stress Globally Downregulates Photosynthesis Genes. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.K.; John Foulkes, M.; Paveley, N.D. Foliar Pathogenesis and Plant Water Relations: A Review. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4321–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.P.; Colmer, T.D.; Barbetti, M.J. Salinity Drives Host Reaction in Phaseolus vulgaris (Common Bean) to Macrophomina phaseolina. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Hauser, F.; Ha, T.; Xue, S.; Böhmer, M.; Nishimura, N.; Munemasa, S.; Hubbard, K.; Peine, N.; Lee, B. Chemical Genetics Reveals Negative Regulation of Abscisic Acid Signaling by a Plant Immune Response Pathway. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelenska, J.; Van Hal, J.A.; Greenberg, J.T. Pseudomonas Syringae Hijacks Plant Stress Chaperone Machinery for Virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 13177–13182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clément, M.; Leonhardt, N.; Droillard, M.-J.; Reiter, I.; Montillet, J.-L.; Genty, B.; Lauriere, C.; Nussaume, L.; Noël, L.D. The Cytosolic/Nuclear HSC70 and HSP90 Molecular Chaperones Are Important for Stomatal Closure and Modulate Abscisic Acid-Dependent Physiological Responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.K.; Lundberg, D.; Torres, M.A.; Matthews, R.; Akimoto-Tomiyama, C.; Farmer, L.; Dangl, J.L.; Grant, S.R. The Pseudomonas Syringae Type III Effector HopAM1 Enhances Virulence on Water-Stressed Plants. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Chen, F.; Mannas, J.P.; Feldman, T.; Sumner, L.W.; Roossinck, M.J. Virus Infection Improves Drought Tolerance. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusche, M.; Thole, K.; Janz, D.; Truskina, J.; Rindfleisch, S.; Drübert, C.; Polle, A.; Lipka, V.; Teichmann, T. Verticillium Infection Triggers VASCULAR-RELATED NAC DOMAIN7–Dependent de Novo Xylem Formation and Enhances Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3823–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, I.C.; Pérez-Alfocea, F. Microbial Amelioration of Crop Salinity Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3415–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, L.M.; Redman, R.S.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Roossinck, M.J. A Virus in a Fungus in a Plant: Three-Way Symbiosis Required for Thermal Tolerance. science 2007, 315, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.; Bakker, P.A. The Rhizosphere Microbiome and Plant Health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goellner, K.; Conrath, U. Priming: It’s All the World to Induced Disease Resistance. Sustain. Dis. Manag. Eur. Context 2008, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissoudis, C. Genetics and Regulation of Combined Abiotic and Biotic Stress Tolerance in Tomato. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Khara, J.; Habibi, G. Combined Hydrogen Peroxide and Nitric Oxide Priming Modulate Salt Stress Tolerance in Acclimated and Non-Acclimated Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) Plants. J. Plant Physiol. Breed. 2020, 10, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Nafees, M.; Chen, J.; Darras, A.; Ferrante, A.; Hancock, J.T.; Ashraf, M.; Zaid, A.; Latif, N.; Corpas, F.J. Chemical Priming Enhances Plant Tolerance to Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 946922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellouzi, H.; Oueslati, S.; Hessini, K.; Rabhi, M.; Abdelly, C. Seed-Priming with H2O2 Alleviates Subsequent Salt Stress by Preventing ROS Production and Amplifying Antioxidant Defense in Cauliflower Seeds and Seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, M.M.; Kalantar, M.; Dehghani-Zahedani, M. H2O2 Seed Priming Improves Tolerance to Salinity Stress in Durum Wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 2023, 51, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, L.C.; Nekati, L.; Makhwitine, P.J.; Ndlovu, S.I. Epigenetic Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Endophytic Fungi Using Small Molecular Modifiers. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 815008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillo, E.H.; Kimotho, R.N.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, P. Transcription Factors Associated with Abiotic and Biotic Stress Tolerance and Their Potential for Crops Improvement. Genes 2019, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlenbock, P.; Plaszczyca, M.; Plaszczyca, M.; Mellerowicz, E.; Karpinski, S. Lysigenous Aerenchyma Formation in Arabidopsis Is Controlled by LESION SIMULATING DISEASE1. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3819–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, J.; Yang, S. The Arabidopsis LSD1 Gene Plays an Important Role in the Regulation of Low Temperature-dependent Cell Death. New Phytol. 2010, 187, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnocka, W.; Van Der Kelen, K.; Willems, P.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Shahnejat-Bushehri, S.; Balazadeh, S.; Rusaczonek, A.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Van Breusegem, F.; Karpiński, S. The Dual Role of LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 as a Condition-dependent Scaffold Protein and Transcription Regulator. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2644–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.E.; Holub, E.B.; Frost, L.N.; Falk, A.; Gunn, N.D.; Daniels, M.J. Characterization of Eds1, a Mutation in Arabidopsis Suppressing Resistance to Peronospora parasitica Specified by Several Different RPP Genes. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 2033–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazebrook, J.; Zook, M.; Mert, F.; Kagan, I.; Rogers, E.E.; Crute, I.R.; Holub, E.B.; Hammerschmidt, R.; Ausubel, F.M. Phytoalexin-Deficient Mutants of Arabidopsis Reveal That PAD4 Encodes a Regulatory Factor and That Four PAD Genes Contribute to Downy Mildew Resistance. Genetics 1997, 146, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.J.; Rusaczonek, A.; Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Salicylic Acid Accumulation Controlled by LSD1 Is Essential in Triggering Cell Death in Response to Abiotic Stress. Cells 2021, 10, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.J.; Mielecki, J.; Antczak, A.; Drożdżek, M.; Witoń, D.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Gawroński, P.; Burdiak, P.; Marchwicka, M.; Rusaczonek, A. Biotechnological Potential of the Stress Response and Plant Cell Death Regulators Proteins in the Biofuel Industry. Cells 2023, 12, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.J.; Rusaczonek, A.; Gołębiewska, K.; Majewska-Fala, A.B.; Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S.M. METACASPASE8 (MC8) Is a Crucial Protein in the LSD1-Dependent Cell Death Pathway in Response to Ultraviolet Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ślesak, I.; SZECHYŃSKA-HEBDA, M.; Fedak, H.; Sidoruk, N.; DĄBROWSKA-BRONK, J.; Witoń, D.; Rusaczonek, A.; Antczak, A.; Drożdżek, M.; Karpińska, B. PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT 4 Affects Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism, Cell Wall and Wood Properties in Hybrid Aspen (Populus tremula L.× tremuloides). Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.J.; Czarnocka, W.; Witoń, D.; Rusaczonek, A.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Ślesak, I.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Karpiński, S. ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 (EDS1) Affects Development, Photosynthesis, and Hormonal Homeostasis in Hybrid Aspen (Populus tremula L.× P. tremuloides). J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 226, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Shao, H.; Tang, X. Recent Advances in Utilizing Transcription Factors to Improve Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance by Transgenic Technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglawe, S.; Fakrudin, B.; Patole, C.; Bhairappanavar, S.; Koti, R.; Krishnaraj, P. Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis of 20 Transcription Factor Genes of MADS, ARF, HAP2, MBF and HB Families in Moisture Stressed Shoot and Root Tissues of Sorghum. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2012, 18, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Vanitha, J.; Ramachandran, S.; Jiang, S. Genome-wide Expansion and Expression Divergence of the Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factors in Higher Plants with an Emphasis on Sorghum F. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan Thi Hoang, X.; Ngoc Hai Nhi, D.; Binh Anh Thu, N.; Phuong Thao, N.; Phan Tran, L.-S. Transcription Factors and Their Roles in Signal Transduction in Plants under Abiotic Stresses. Curr. Genomics 2017, 18, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S. Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by Two Pathogen-Responsive MAPKs Drives Phytoalexin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Yang, K.-Y.; Mordorski, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. Phosphorylation of an ERF Transcription Factor by Arabidopsis MPK3/MPK6 Regulates Plant Defense Gene Induction and Fungal Resistance. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Nomura, K.; Hui, S.; Gui, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Q. An MKP-MAPK Protein Phosphorylation Cascade Controls Vascular Immunity in Plants. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabg8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, M.; Wang, P.; Cox Jr, K.L.; Duan, L.; Dever, J.K.; Shan, L.; Li, Z.; He, P. Regulation of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) Drought Responses by Mitogen-activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Cascade-mediated Phosphorylation of Gh WRKY 59. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wan, J.X.; Liu, Y.S.; Yang, X.Z.; Shen, R.F.; Zhu, X.F. The NAC Transcription Factor ANAC017 Regulates Aluminum Tolerance by Regulating the Cell Wall-Modifying Genes. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 2517–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Elvitigala, T.; Ghosh, B.; Quatrano, R.S. Arabidopsis Transcriptome Reveals Control Circuits Regulating Redox Homeostasis and the Role of an AP2 Transcription Factor. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 2050–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M.; Johnson, J.M.; Hieno, A.; Tokizawa, M.; Nomoto, M.; Tada, Y.; Godfrey, R.; Obokata, J.; Sherameti, I.; Yamamoto, Y.Y. High REDOX RESPONSIVE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR1 Levels Result in Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in Arabidopsis thaliana Shoots and Roots. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1253–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.-T.; Xu, P.; Zhao, P.-X.; Liu, R.; Yu, L.-H.; Xiang, C.-B. Arabidopsis ERF109 Mediates Cross-Talk between Jasmonic Acid and Auxin Biosynthesis during Lateral Root Formation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahieldin, A.; Atef, A.; Edris, S.; Gadalla, N.O.; Ali, H.M.; Hassan, S.M.; Al-Kordy, M.A.; Ramadan, A.M.; Makki, R.M.; Al-Hajar, A.S. Ethylene Responsive Transcription Factor ERF109 Retards PCD and Improves Salt Tolerance in Plant. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantabella, D.; Karpinska, B.; Teixidó, N.; Dolcet-Sanjuan, R.; Foyer, C.H. Non-Volatile Signals and Redox Mechanisms Are Required for the Responses of Arabidopsis Roots to Pseudomonas oryzihabitans. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 6971–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Patil, V.; Kumar, R.; Gautam, J.K.; Singh, V.; Nandi, A.K. RSI1/FLD and Its Epigenetic Target RRTF1 Are Essential for the Retention of Infection Memory in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2023, 115, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białas, A.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. The New Role of Carbonic Anhydrases and Bicarbonate in Acclimatization and Hypoxia Stress Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. The Cbfs Triple Mutants Reveal the Essential Functions of CBF s in Cold Acclimation and Allow the Definition of CBF Regulons in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, K.-J.; Turkan, I.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Redox-and Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Signaling into and out of the Photosynthesizing Chloroplast. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1541–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Van Aken, O.; Schwarzländer, M.; Belt, K.; Millar, A.H. The Roles of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Cellular Signaling and Stress Response in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchev, P.; Waszczak, C.; Lewandowska, A.; Willems, P.; Shapiguzov, A.; Li, Z.; Alseekh, S.; Mühlenbock, P.; Hoeberichts, F.A.; Huang, J. Lack of GLYCOLATE OXIDASE1, but Not GLYCOLATE OXIDASE2, Attenuates the Photorespiratory Phenotype of CATALASE2-Deficient Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1704–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Serrano, M.; Romero-Puertas, M.C.; Sanz-Fernández, M.; Hu, J.; Sandalio, L.M. Peroxisomes Extend Peroxules in a Fast Response to Stress via a Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Induction of the Peroxin PEX11a. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, D.; Takumi, S.; Hashiguchi, M.; Sejima, T.; Miyake, C. Superoxide and Singlet Oxygen Produced within the Thylakoid Membranes Both Cause Photosystem I Photoinhibition. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gollery, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Gene Network of Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.A.; Daudi, A.; Butt, V.S.; Paul Bolwell, G. Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Role in Plant Defence and Cell Wall Metabolism. Planta 2012, 236, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breusegem, F.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Mittler, R. Unraveling the Tapestry of Networks Involving Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpas, F.J.; Gupta, D.K.; Palma, J.M. Production Sites of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Organelles from Plant Cells. React. Oxyg. Species Oxidative Damage Plants Stress 2015, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, Q.M.; Shahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Yun, B.-W. NO and ROS Crosstalk and Acquisition of Abiotic Stress Tolerance. In Nitric Oxide in Plant Biology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 477–491. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Raji, M. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Modulating Cross Tolerance in Plants via Flavonoids. In Priming-mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in crop plants; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 203–214. [CrossRef]

- Locato, V.; Cimini, S.; De Gara, L. ROS and Redox Balance as Multifaceted Players of Cross-Tolerance: Epigenetic and Retrograde Control of Gene Expression. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3373–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, A.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Development. Development 2018, 145, dev164376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, M.; Fahad, S.; Shah, A.N.; Bukhari, M.A.; Maryam; Ahmed, I.; Ahmad, S.; Hussain, S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling in Plants. Plant Abiotic Stress Toler. Agron. Mol. Biotechnol. Approaches 2019, 259–272. [CrossRef]

- Kazan, K.; Manners, J.M. Jasmonate Signaling: Toward an Integrated View. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Charagh, S.; Zahid, Z.; Mubarik, M.S.; Javed, R.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Jasmonic Acid: A Key Frontier in Conferring Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1513–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasternack, C.; Strnad, M. Jasmonate Signaling in Plant Stress Responses and Development–Active and Inactive Compounds. New Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santner, A.; Estelle, M. Recent Advances and Emerging Trends in Plant Hormone Signalling. Nature 2009, 459, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-X.; J Ahammed, G.; Wu, C.; Fan, S.; Zhou, Y.-H. Crosstalk among Jasmonate, Salicylate and Ethylene Signaling Pathways in Plant Disease and Immune Responses. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015, 16, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatz, C. From Pioneers to Team Players: TGA Transcription Factors Provide a Molecular Link between Different Stress Pathways. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Lv, Z.; Khanzada, A.; Huang, M.; Cai, J.; Zhou, Q.; Huo, Z.; Jiang, D. Effects of Cold and Salicylic Acid Priming on Free Proline and Sucrose Accumulation in Winter Wheat under Freezing Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 2171–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, M.S.; Petersen, M.; Mundy, J. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, S.; de Vries, J.; von Dahlen, J.K.; Gould, S.B.; Archibald, J.M.; Rose, L.E.; Slamovits, C.H. On Plant Defense Signaling Networks and Early Land Plant Evolution. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Iqbal, N.; Masood, A.; Per, T.S.; Khan, N.A. Salicylic Acid Alleviates Adverse Effects of Heat Stress on Photosynthesis through Changes in Proline Production and Ethylene Formation. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e26374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Bullock Jr, D.A.; Alonso, J.M.; Stepanova, A.N. To Fight or to Grow: The Balancing Role of Ethylene in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses. Plants 2021, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.V.; Lee, H.; Davis, K.R. Ozone-induced Ethylene Production Is Dependent on Salicylic Acid, and Both Salicylic Acid and Ethylene Act in Concert to Regulate Ozone-induced Cell Death. Plant J. 2002, 32, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, D.; Nakajima, N.; Sano, T.; Tamaoki, M.; Aono, M.; Kubo, A.; Kanna, M.; Ioki, M.; Kamada, H.; Saji, H. Salicylic Acid Accumulation under O3 Exposure Is Regulated by Ethylene in Tobacco Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.M.; Heo, A.Y.; Choi, H.W. Salicylic Acid as a Safe Plant Protector and Growth Regulator. Plant Pathol. J. 2020, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Salicylic Acid Enhances Antifungal Resistance to Magnaporthe grisea in Rice Plants. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2008, 37, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmailzadeh, M.; Soleimani, M.; Rouhani, H. Exogenous Applications of Salicylic Acid for Inducing Systemic Acquired Resistance against Tomato Stem Canker Disease. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Jendoubi, W.; Harbaoui, K.; Hamada, W. Salicylic Acid-Induced Resistance against Fusarium oxysporumf. s. Pradicis lycopercisi in Hydroponic Grown Tomato Plants. J. New Sci. 2015, 21. https://www.jnsciences.org/agri-biotech/29-volume-21.html.

- Kundu, S.; Chakraborty, D.; Pal, A. Proteomic Analysis of Salicylic Acid Induced Resistance to Mungbean Yellow Mosaic India Virus in Vigna Mungo. J. Proteomics 2011, 74, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thanh, T.; Thumanu, K.; Wongkaew, S.; Boonkerd, N.; Teaumroong, N.; Phansak, P.; Buensanteai, N. Salicylic Acid-Induced Accumulation of Biochemical Components Associated with Resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae Pv. oryzae in Rice. J. Plant Interact. 2017, 12, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan Babu, R.; Sajeena, A.; Vijaya Samundeeswari, A.; Sreedhar, A.; Vidhyasekaran, P.; Seetharaman, K.; Reddy, M. Induktion Einer Systemischen Resistenz Gegen Xanthomonas oryzae Pv. oryzae Durch Salicylsäure in Oryza sativa (L.). J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2003, 110, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, D.E.M.; Fayez, K.A.; Mahmoud, S.Y.; Hamad, A.; Lu, G. Physiological and Metabolic Changes of Cucurbita Pepo Leaves in Response to Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus (ZYMV) Infection and Salicylic Acid Treatments. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 45, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, R.; Singh, T.; Kumar, R.; Srivastava, J.; Srivastava, A.K.; Singh, K.; Arora, D.K. Role of Salicylic Acid in Systemic Resistance Induced by Pseudomonas Fluorescens against Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. ciceri in Chickpea. Microbiol. Res. 2003, 158, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.-H. Exogenous Treatment with Salicylic Acid Attenuates Occurrence of Citrus Canker in Susceptible Navel Orange (Citrus Sinensis Osbeck). J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Jun, W.J.; Chen ShaoHong, C.S.; Huang YongFang, H.Y.; Sun Si, S.S. Induced Resistance to Anthracnose of Camellia oleifera by Salicylic Acid. 2006. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20073031288.

- Erb, M.; Meldau, S.; Howe, G.A. Role of Phytohormones in Insect-Specific Plant Reactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.-S.; Han, G.-Z. Insights into the Origin and Evolution of the Plant Hormone Signaling Machinery. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Huang, H.; Gao, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Zhai, Q.; Li, C.; Qi, T. Interaction between MYC2 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 Modulates Antagonism between Jasmonate and Ethylene Signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Lee, B. Friends or Foes: New Insights in Jasmonate and Ethylene Co-Actions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Song, S. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Signaling by Proteins Activating and Repressing Transcription. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; An, F.; Hao, D.; Li, P.; Song, J.; Yi, C.; Guo, H. Jasmonate-Activated MYC2 Represses ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 Activity to Antagonize Ethylene-Promoted Apical Hook Formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-C.; Liao, P.-M.; Kuo, W.-W.; Lin, T.-P. The Arabidopsis ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 Regulates Abiotic Stress-Responsive Gene Expression by Binding to Different Cis-Acting Elements in Response to Different Stress Signals. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1566–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, O.; Piqueras, R.; Sánchez-Serrano, J.J.; Solano, R. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 Integrates Signals from Ethylene and Jasmonate Pathways in Plant Defense. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, M.; Lewsey, M.G.; Clark, N.M.; Yin, L.; Bartlett, A.; Saldierna Guzmán, J.P.; Hann, E.; Langford, A.E.; Jow, B.; Wise, A. Integrated Multi-Omics Framework of the Plant Response to Jasmonic Acid. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).