Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Datasets

KE Enrichment and Network Analysis

Results

Differential Expression

Network Analysis

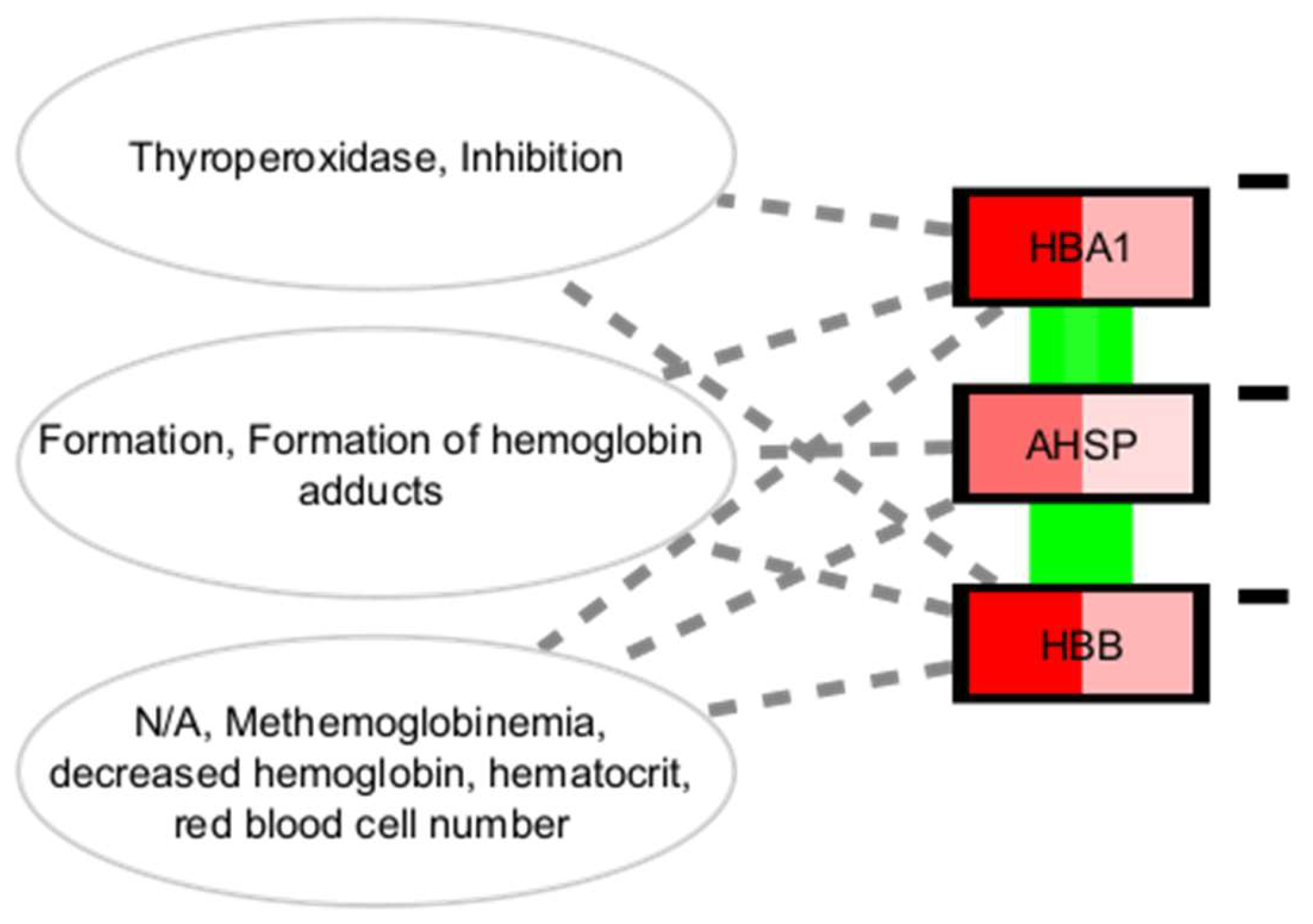

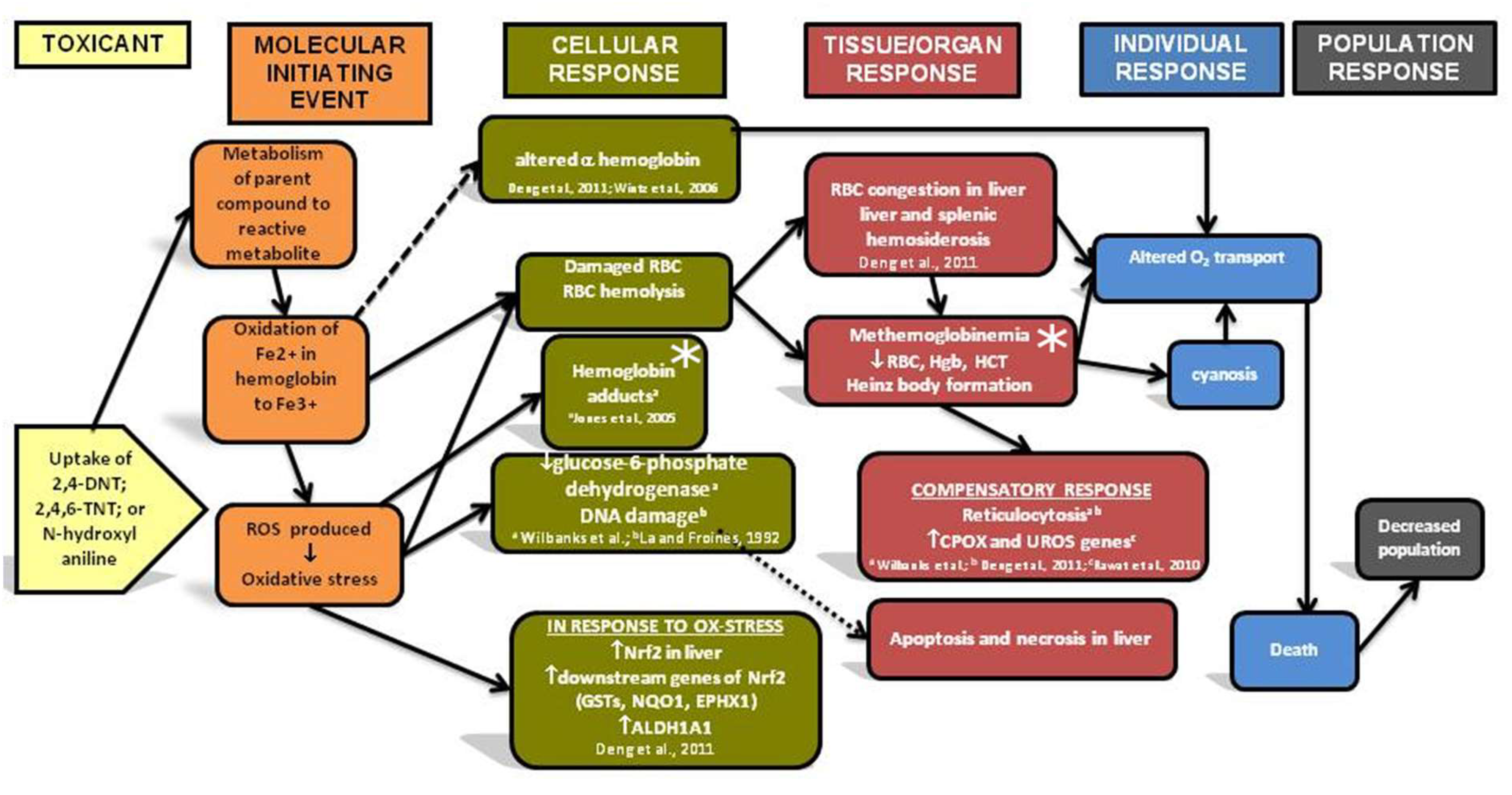

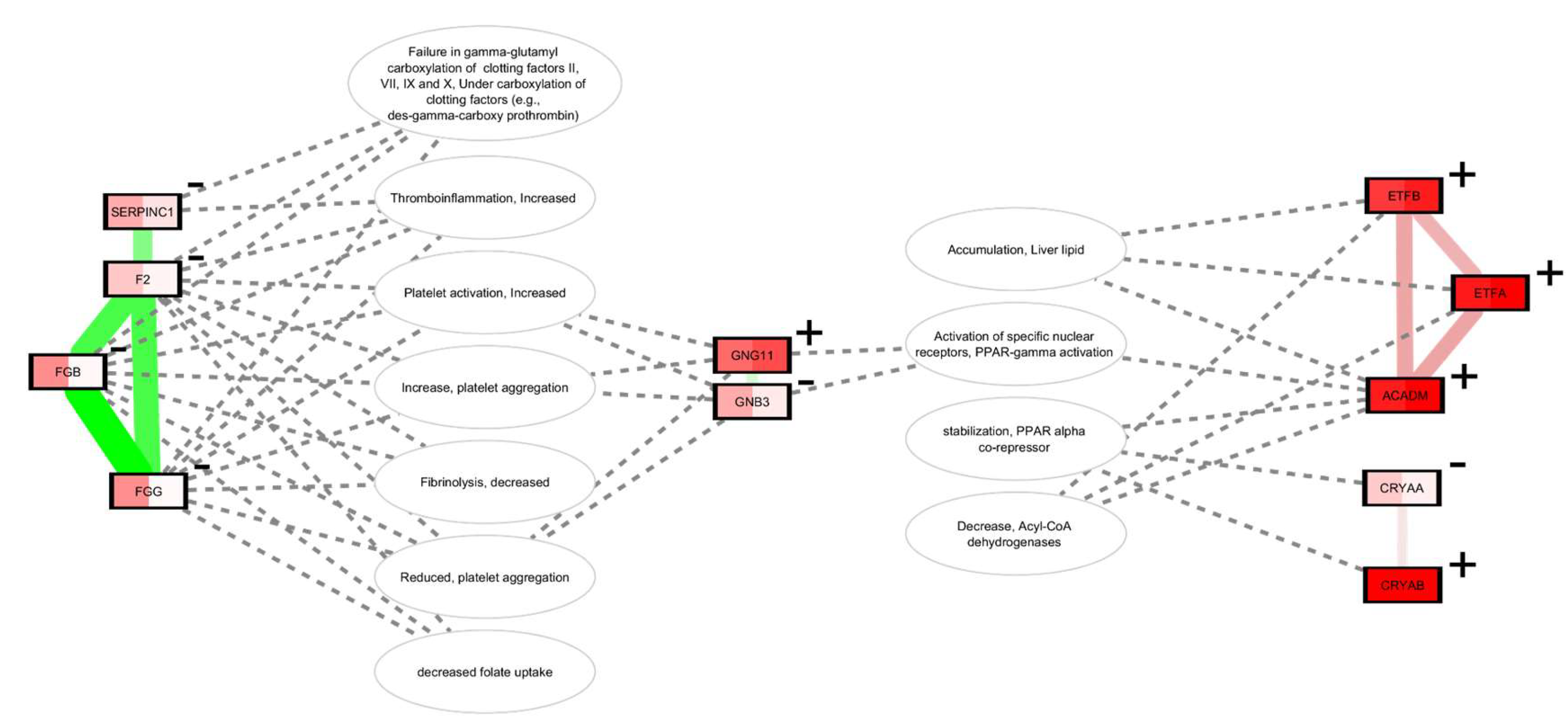

Metformin

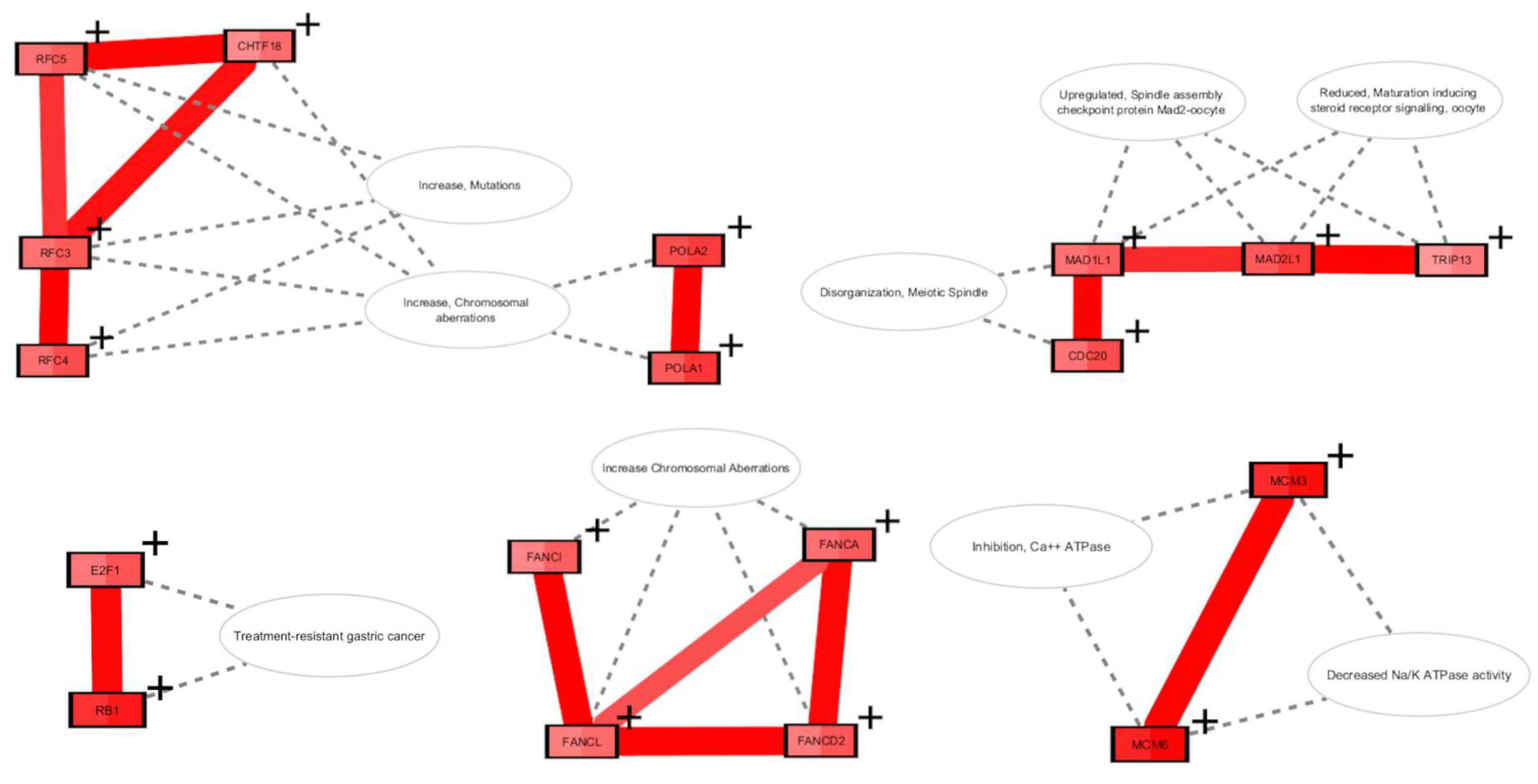

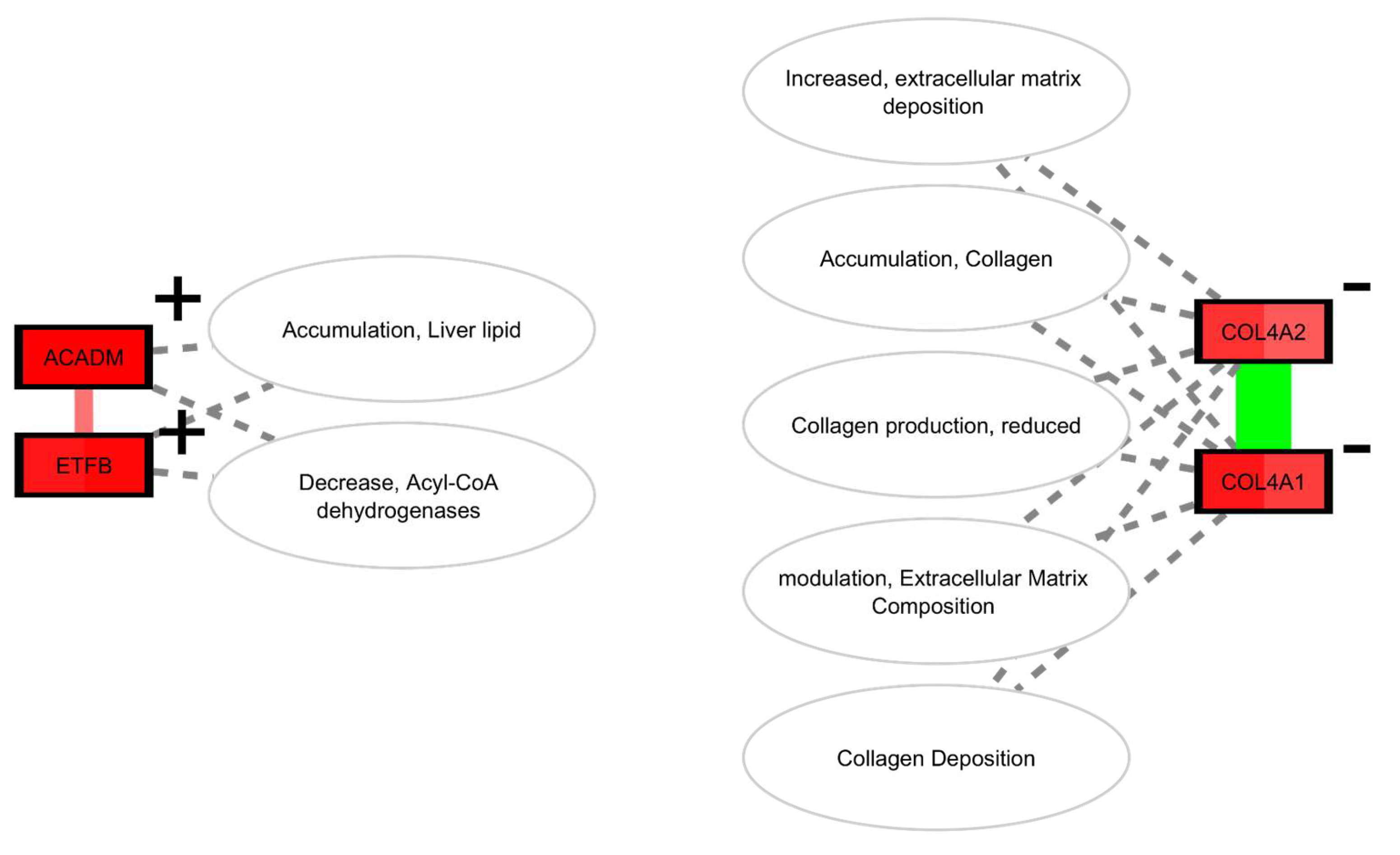

Partial Reprogramming

Discussion

Metformin

Partial Reprogramming

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ustinova, M.; Silamikelis, I.; Kalnina, I.; Ansone, L.; Rovite, V.; Elbere, I.; Radovica-Spalvina, I.; Fridmanis, D.; Aladyeva, J.; Konrade, I.; et al. Metformin strongly affects transcriptome of peripheral blood cells in healthy individuals. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0224835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browder, K.C.; Reddy, P.; Yamamoto, M.; Haghani, A.; Guillen, I.G.; Sahu, S.; Wang, C.; Luque, Y.; Prieto, J.; Shi, L.; et al. In vivo partial reprogramming alters age-associated molecular changes during physiological aging in mice. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarimäki, L.A.; Fratello, M.; Pavel, A.; Korpilähde, S.; Leppänen, J.; Serra, A.; Greco, D. A curated gene and biological system annotation of adverse outcome pathways related to human health. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warsow, G.; Greber, B.; Falk, S.S.; Harder, C.; Siatkowski, M.; Schordan, S.; Som, A.; Endlich, N.; Schöler, H.; Repsilber, D.; et al. ExprEssence - Revealing the essence of differential experimental data in the context of an interaction/regulation net-work. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 164–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Quan, H.; Li, J. Vitamin B12 Status in Metformin Treated Patients: Systematic Review. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, L.A.; Dennis, J.M.; Coleman, R.L.; Sattar, N.; Hattersley, A.T.; Holman, R.R.; Pearson, E.R. Risk of Anemia With Metformin Use in Type 2 Diabetes: A MASTERMIND Study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, V.; Condorelli, R.A.; Cannarella, R.; Aversa, A.; Calogero, A.E.; La Vignera, S. Relationship between Iron Deficiency and Thyroid Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, S.Y.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Hurrell, R.F.; Arnold, M.; Langhans, W. Iron Deficiency Anemia Reduces Thyroid Peroxidase Activity in Rats. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1951–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leaman, S.; Marichal, N.; Berninger, B. Reprogramming cellular identity in vivo. Development 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chondronasiou, D.; Gill, D.; Mosteiro, L.; Urdinguio, R.G.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Aguilera, M.; Durand, S.; Aprahamian, F.; Nirmalathasan, N.; Abad, M.; et al. Multi-omic rejuvenation of naturally aged tissues by a single cycle of transient reprogramming. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, A.P.Y. , et al., Suppression of ACADM-Mediated Fatty Acid Oxidation Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Aberrant CAV1/SREBP1 Signaling. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 3679–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H., Y. Wang, and H. Ding, COL4A1, negatively regulated by XPD and miR-29a-3p, promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in liver cancer cells. Clin Transl Oncol 2021, 23, 2078–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Fatty acids and inflammation: The cutting edge between food and pharma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 668 (Suppl. S1), S50–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doeser, M.C.; Schöler, H.R.; Wu, G. Reduction of Fibrosis and Scar Formation by Partial Reprogramming In Vivo. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, S.R. , et al., A high-throughput study in melanoma identifies epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a major determinant of metastasis. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 3450–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lulli, M.; Nencioni, D.; Papucci, L.; Schiavone, N. Zeta-crystallin: a moonlighting player in cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidieh, B.; Bain, A.L.; Tria, S.M.; Sharma, S.; Stewart, C.A.; Simmons, J.L.; Apaja, P.M.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Finnie, J.; Khanna, K.K. Alpha-B-Crystallin overexpression is sufficient to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis in mice. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L. , et al., The role of CRYAB in tumor prognosis and immune infiltration: A Pan-cancer analysis. Front Surg 2022, 9, 1117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tissue | Treatment | Overexpressed DEGs | Underexpressed DEGs | Enriched KEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | Metformin | 12 | 90 | 3 |

| Spleen | Partial Reprogramming | 892 | 251 | 30 |

| Liver | Partial Reprogramming | 330 | 277 | 37 |

| Skin | Partial Reprogramming | 129 | 122 | 59 |

| Kidney | Partial Reprogramming | 101 | 148 | 7 |

| Lung | Partial Reprogramming | 48 | 57 | - |

| Muscle | Partial Reprogramming | 76 | 16 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).