Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

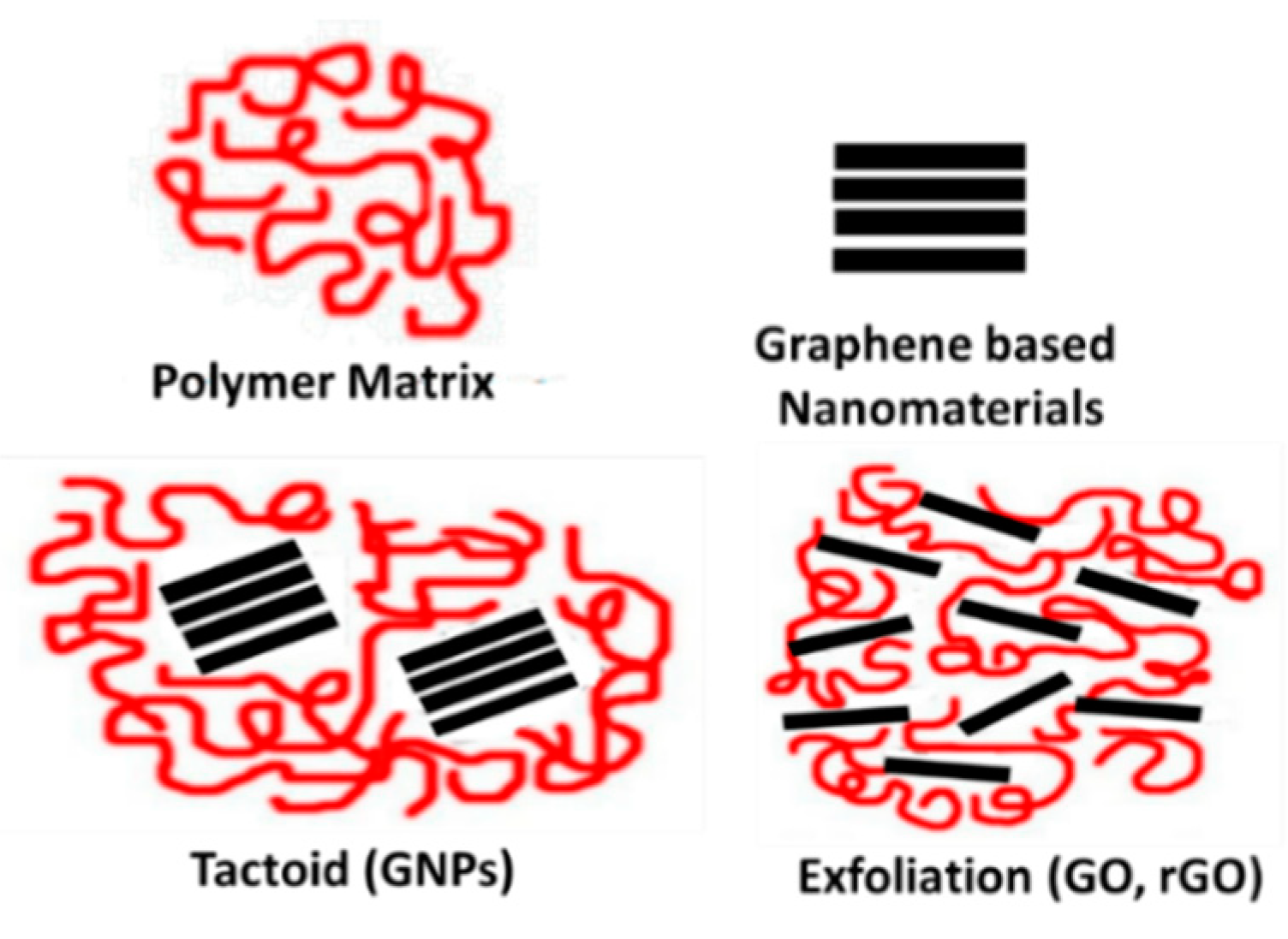

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Materials

3. Experimental Techniques

3.1. Characterization Technique

4. Results and Discussion

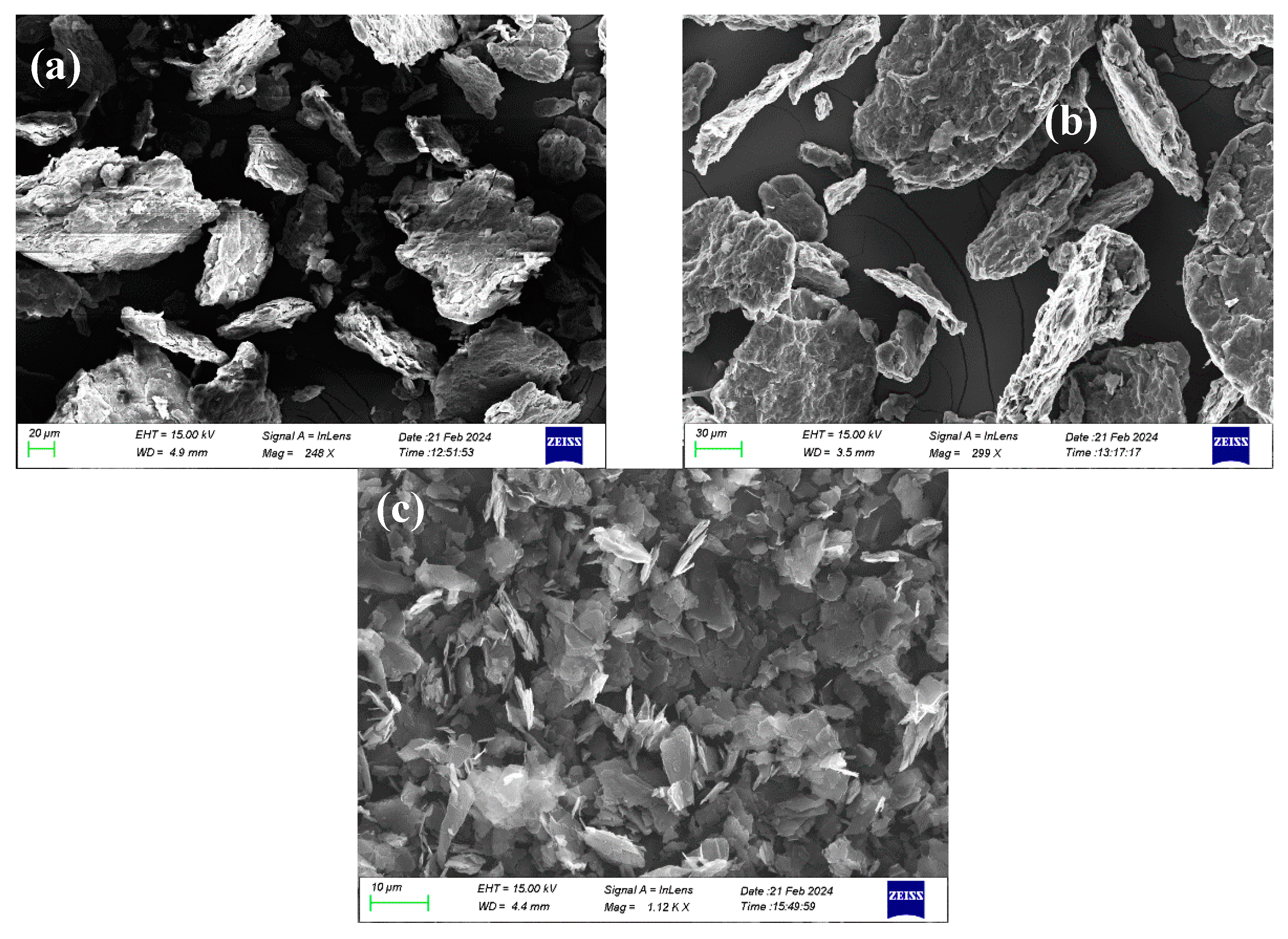

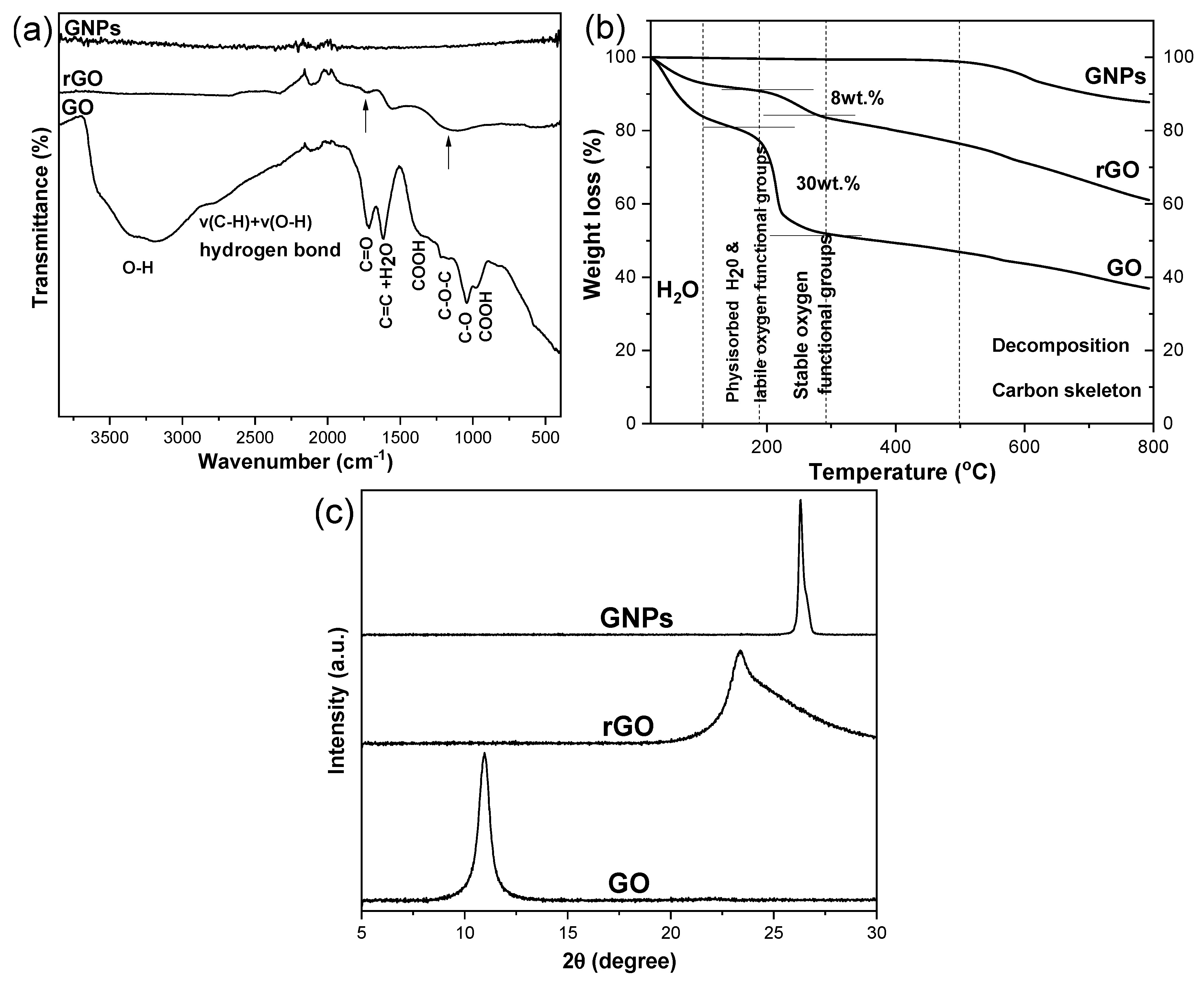

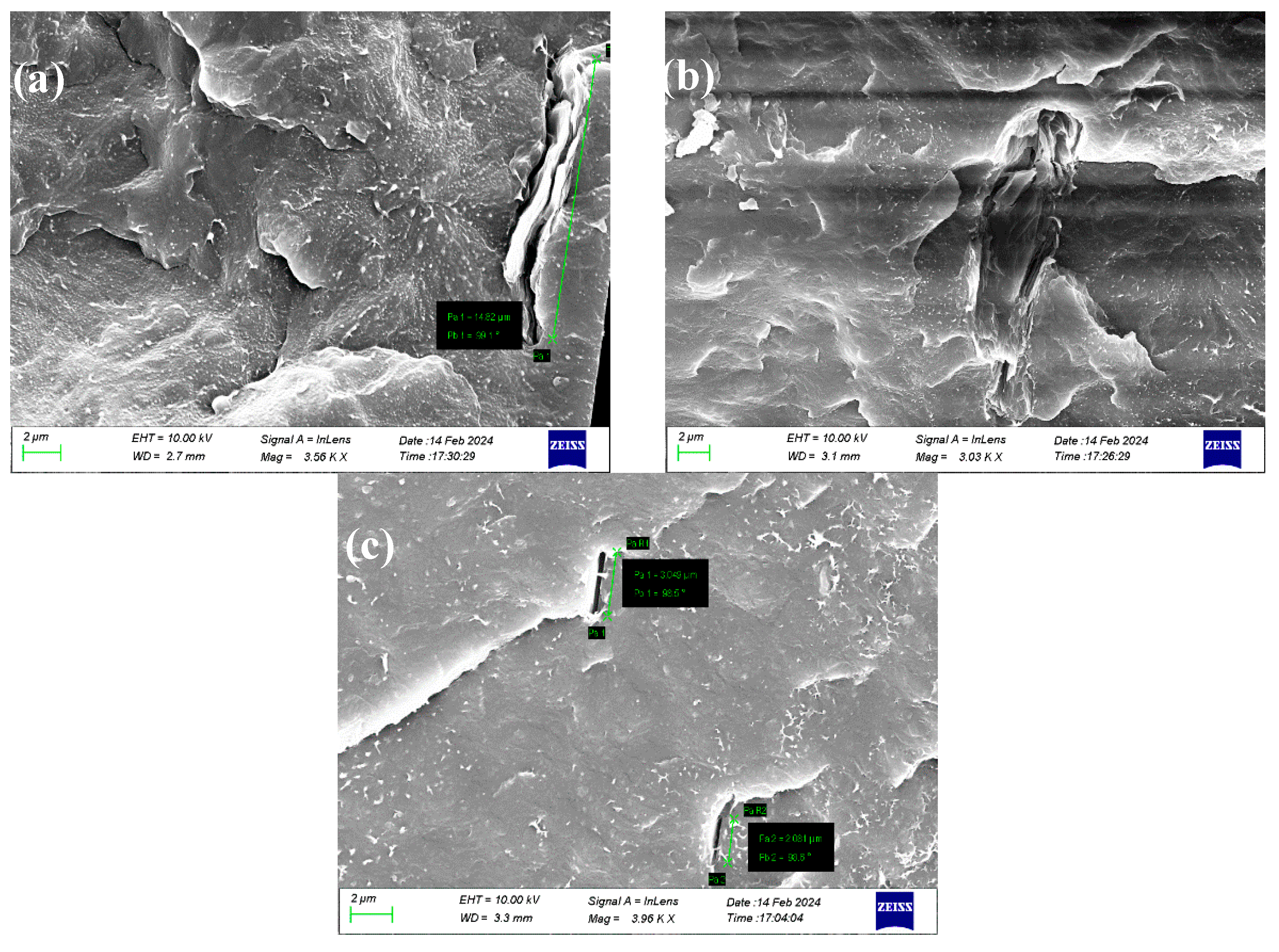

4.1. Characterization of 2D Carbon Based Nanomaterials

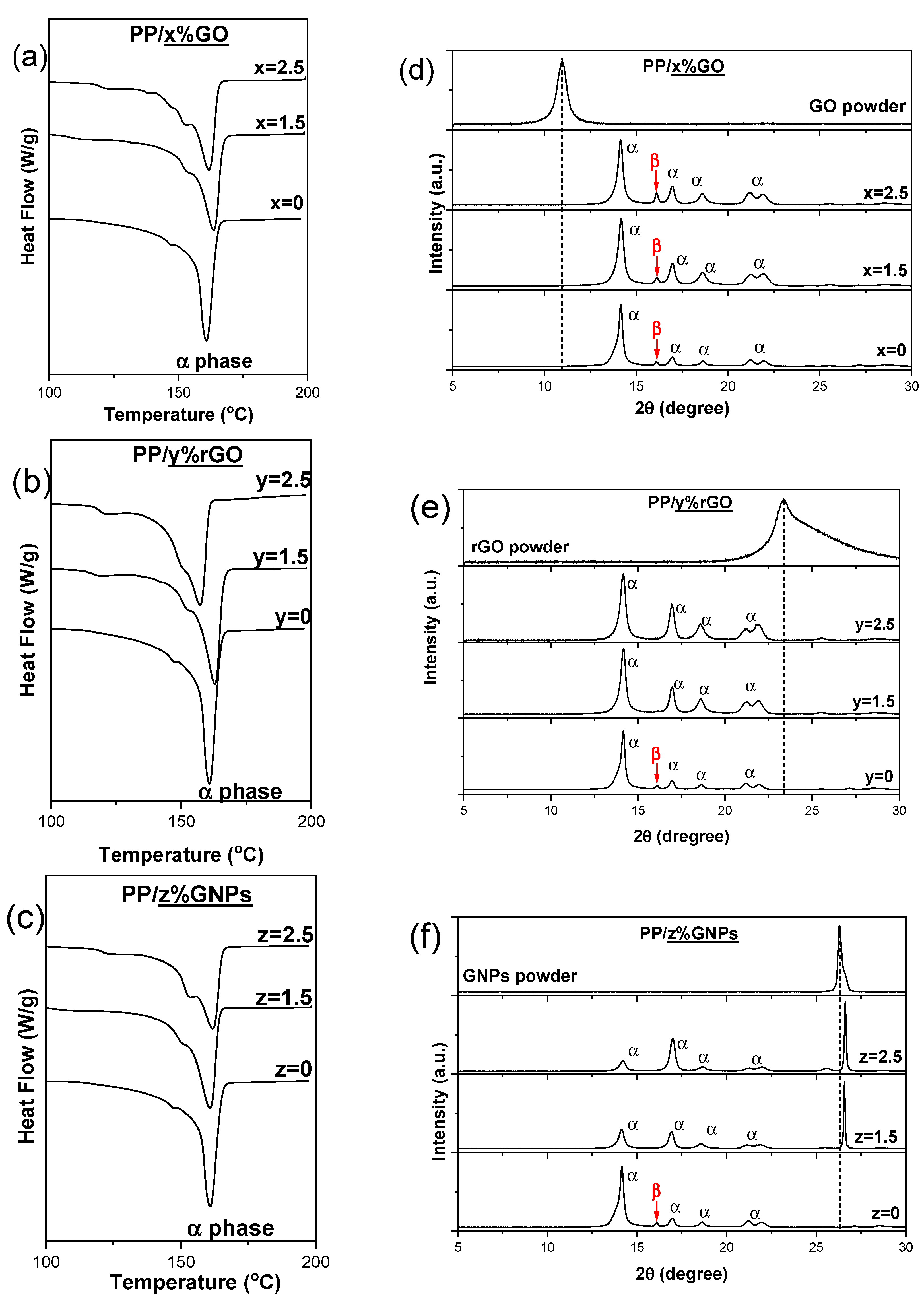

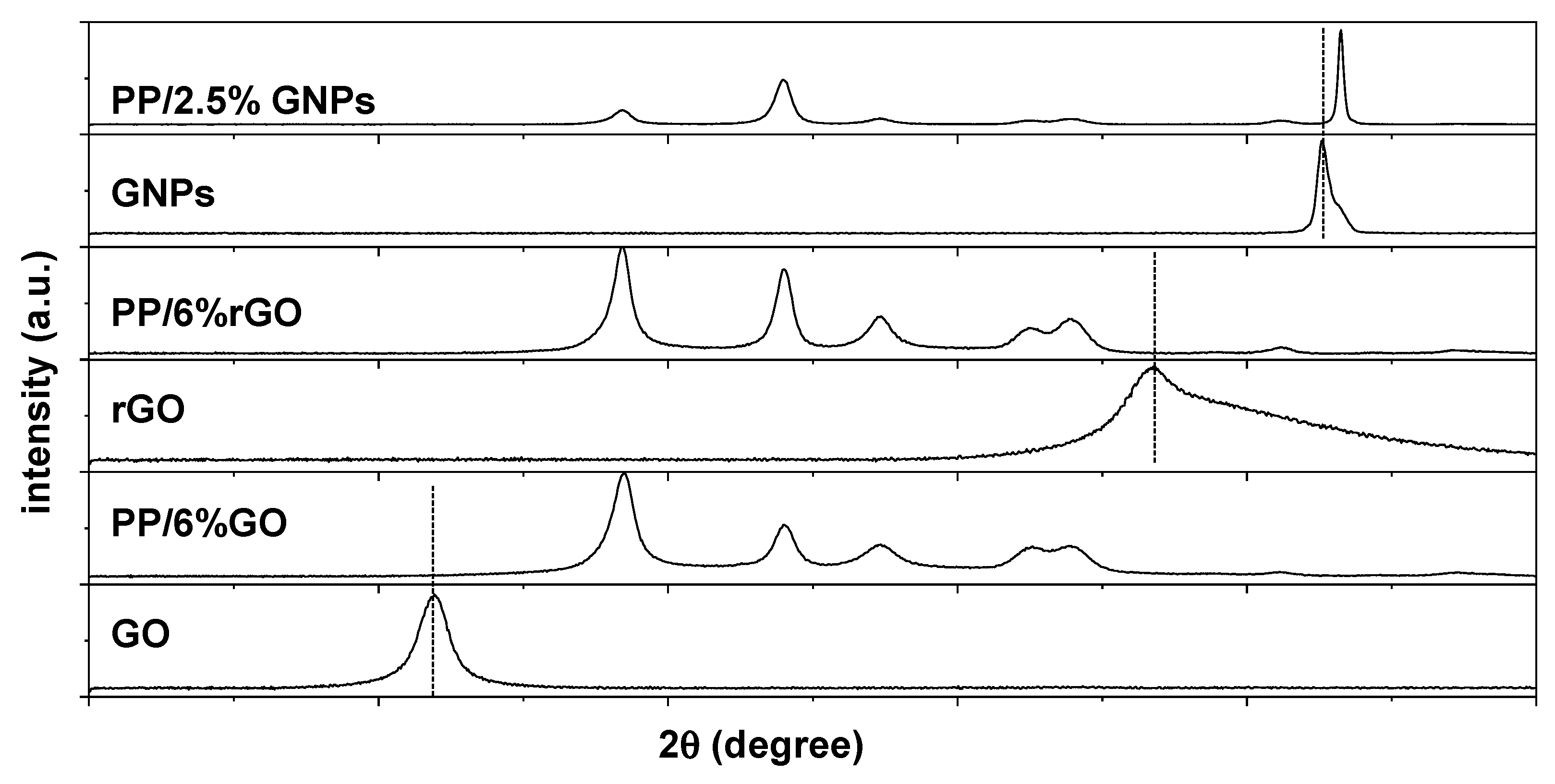

4.2. Characterization of 2D Carbon Based Nanocomposite Films

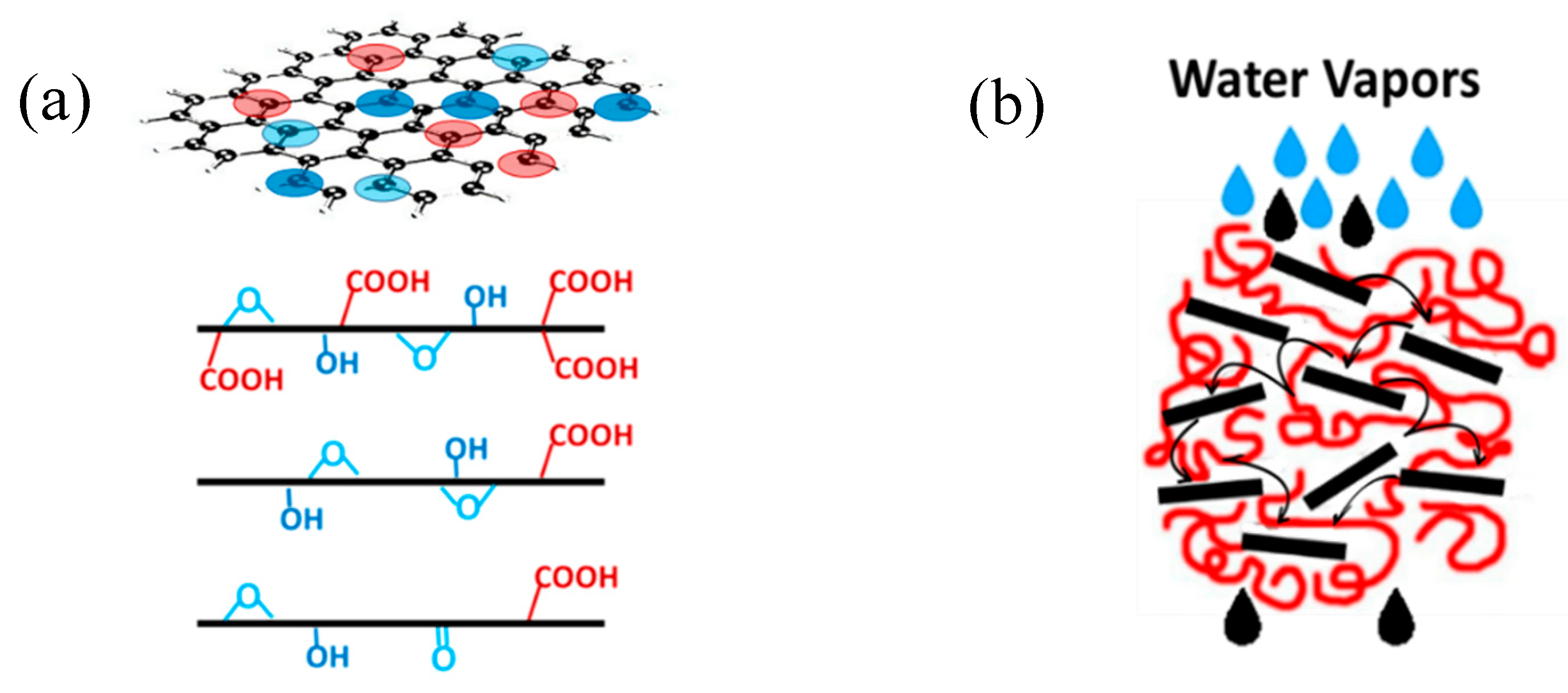

4.3. Underlaying Interactions Inside the Composite

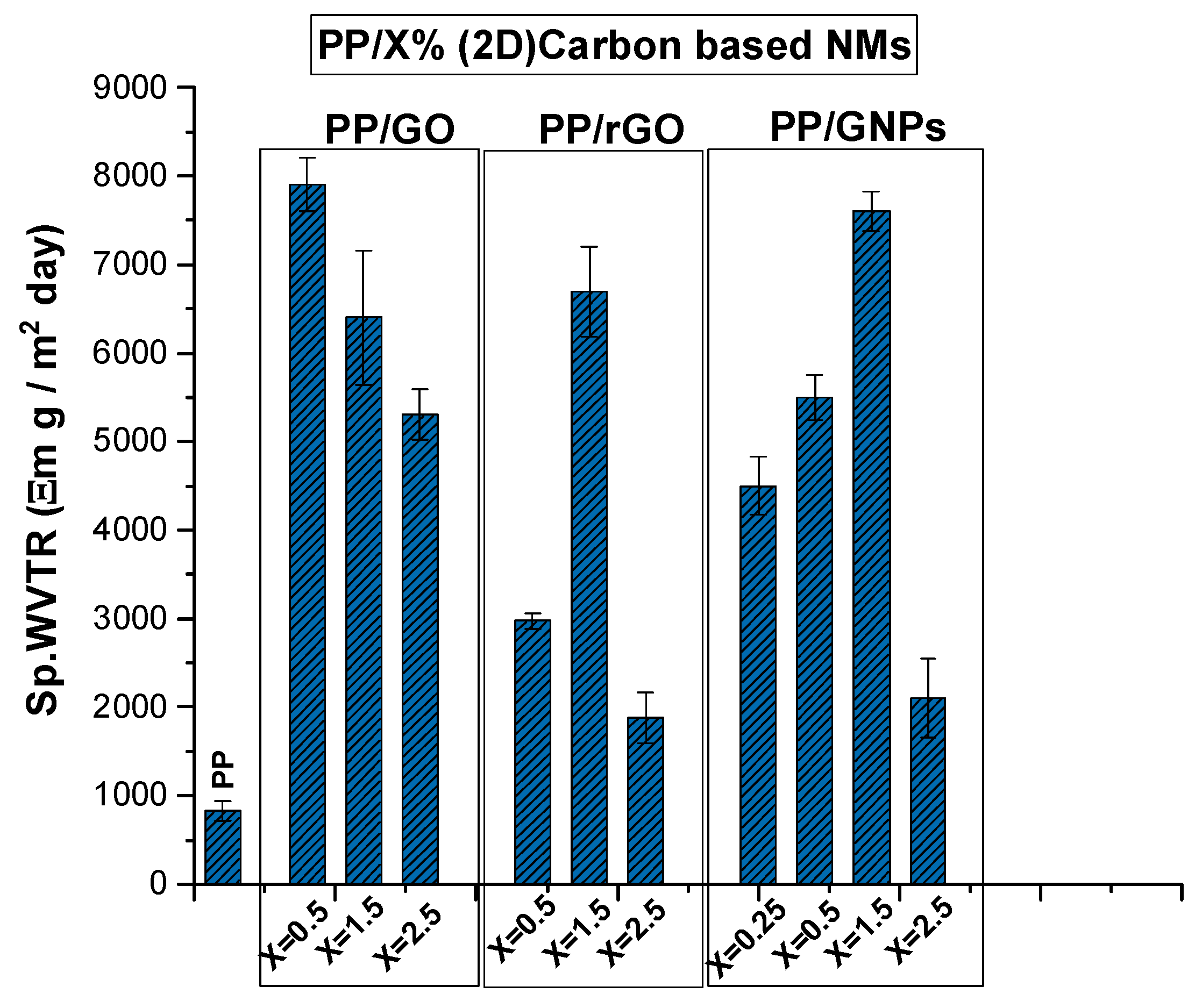

4.4. Water Vapor Transport Through Hybrid Composite PP Films

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Wu, P.C.; Jones, G.; Shelle, C.; Woelfli, B. Novel Microporous Films and Their Composites. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 2007, 2, 155892500700200105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jun, S.C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, F.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Advancements in Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Improved Waterproofing and Breathability. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2023, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvini, G.A.; Mathioudakis, G.N.; Soto Beobide, A.; Piperigkou, Z.; Giannakas, A.E.; Messaritakis, S.; Sotiriou, G.; Voyiatzis, G.A. Improvement of Water Vapor Permeability in Polypropylene Composite Films by the Synergy of Carbon Nanotubes and β-Nucleating Agents. Polymers 2023, 15, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounos, G.; Andrikopoulos, K.; Moschopoulou, H.; Lainioti, G.; Roilo, D.; Checchetto, R.; Ioannides, T.; Kallitsis, J.; Voyiatzis, G. Enhancing Water Vapor Permeability in Mixed Matrix Polypropylene Membranes Through Carbon Nanotubes Dispersion. Journal of Membrane Science 2016, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasiero, F. Water vapor transport in carbon nanotube membranes and application in breathable and protective fabrics. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2017, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jinschek, J.R.; Chen, H.; Sholl, D.S.; Marand, E. Scalable Fabrication of Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Nanocomposite Membranes for High Flux Gas Transport. Nano Letters 2007, 7, 2806–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, Y.; Kim, C.; Seo, D.K.; Kim, T.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, K.H.; Bae, S.S.; Lee, S.C.; Lim, J.; et al. High performance and antifouling vertically aligned carbon nanotube membrane for water purification. Journal of Membrane Science 2014, 460, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, H.D.; Shin, J.E.; Yoo, B.M.; Park, H.B. Water and ion sorption, diffusion, and transport in graphene oxide membranes revisited. Journal of Membrane Science 2017, 544, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Kundalwal, S.; Kumar, S. Gas Barrier Performance of Graphene/Polymer Nanocomposites. Carbon 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Wu, H.A.; Jayaram, P.N.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Geim, A.K. Unimpeded Permeation of Water Through Helium-Leak–Tight Graphene-Based Membranes. Science 2012, 335, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Iqbal, Z.; Sirkar, K.; Peterson, G. Graphene Oxide-Based Membrane as a Protective Barrier against Toxic Vapors and Gases. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygellou, L.; Paterakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Tasis, D. Work Function Τuning of Reduced Graphene Oxide Τhin Films. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M. Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposites for High-Performance Applications II. Polymers 2022, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, I.; Chakraborty, S.; Talukdar, M.; Pal, S.; Chakraborty, S. Thermal reduction of graphene oxide: How temperature influences purity. Journal of Materials Research 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-C.; Chou, H.-Y.; Shen, M.-Y. Effects of adding graphene nanoplatelets and nanocarbon aerogels to epoxy resins and their carbon fiber composites. Materials & Design 2019, 178, 107869. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz, S.; Cullari, L.; Nadiv, R.; Nir, Y.; Laredo, D.; Grunlan, J.; Regev, O. Graphene-induced enhancement of water vapor barrier in polymer nanocomposites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2017, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, S.; Meille, S.; Petraccone, V.; Pirozzi, B. Polymorphism in isotactic polypropylene. Progress in Polymer Science 1991, 16, 361–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, B.; Wittmann, J.C.; Lovinger, A.J. Structure and morphology of poly(propylenes): a molecular analysis. Polymer 1996, 37, 4979–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J. Supermolecular structure of isotactic polypropylene. Journal of Materials Science 1992, 27, 2557–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, F.; Gombár, T.; Varga, J.; Menyhard, A. Crystallization, melting, supermolecular structure and properties of isotactic polypropylene nucleated with dicyclohexyl-terephthalamide. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2016, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, S.; Zong, X.S.; Fang, D.; Hsiao, B.; Chu, B. Structural and Morphological Studies of Isotactic Polypropylene Fibers during Heat/Draw Deformation by in-Situ Synchrotron SAXS/WAXD. Macromolecules 2001, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard test methods for water vapor transmission of materials, ASTM E96/E96M-10. Available online: http://www.astm.org/Standards/E96.htm (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Kumaran, M.K. Interlaboratory Comparison of the ASTM Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials (E 96-95). Journal of Testing and Evaluation 26 26, 83–88. [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, K.; Bounos, G.; Tasis, D.; Sygellou, L.; Drakopoulos, V.; Voyiatzis, G. The Effect of Thermal Reduction on the Water Vapor Permeation in Graphene Oxide Membranes. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, R.; Hosseini, M.; Kazi, S.N.; Bagheri, S.; Ahmed, S.M.; Ahmadi, G.; Zubir, N.; Sayuti, M.; Dahari, M. Study of environmentally friendly and facile functionalization of graphene nanoplatelet and its application in convective heat transfer. Energy Conversion and Management 2017, 150, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.; Pandey, P.; Beanland, R.; Young, R.; Kinloch, I.; Gong, L.; Liu, Z.; Suenaga, K.; Rourke, J.; York, S.; et al. Graphene Oxide: Structural Analysis and Application as a Highly Transparent Support for Electron Microscopy. ACS nano 2009, 3, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Habib, A. Study of band gap reduction of TiO2 thin films with variation in GO contents and use of TiO2/Graphene composite in hybrid solar cell. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 679, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammingkwan, P.; Matsushita, K.; Taniike, T.; Terano, M. Enhancement in Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Polypropylene Using Graphene Oxide Grafted with End-Functionalized Polypropylene. Materials 2016, 9, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Zhu, T.; Li, X.; Shan, M.; Xu, Z.; Jiao, Y. Assembly of graphene oxide on nonconductive nonwovens by the synergistic effect of interception and electrophoresis. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovtyukhova, N.I.; Ollivier, P.J.; Martin, B.R.; Mallouk, T.E.; Chizhik, S.A.; Buzaneva, E.V.; Gorchinskiy, A.D. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Ultrathin Composite Films from Micron-Sized Graphite Oxide Sheets and Polycations. Chemistry of Materials 1999, 11, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Rhyee, J.-S.; Son, J.Y.; Ruoff, R.S.; Rhee, K.-Y. Colors of graphene and graphene-oxide multilayers on various substrates. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 025708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruidíaz-Martínez, M.; Álvarez, M.A.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Cruz-Quesada, G.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M. Hydrothermal Synthesis of rGO-TiO2 Composites as High-Performance UV Photocatalysts for Ethylparaben Degradation. Catalysts 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Haneef, M.; Abbasi, H. Synthesis Route of Reduced Graphene Oxide Via Thermal Reduction of Chemically Exfoliated Graphene Oxide. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2017, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.K.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Mina, M.F.; Islam, M.R.; Gafur, M.A.; Begum, A. Crystalline morphology and properties of multi-walled carbon nanotube filled isotactic polypropylene nanocomposites: Influence of filler size and loading. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2013, 52, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Bourson, P.; Dahoun, A.; Hiver, J. The β-Spherulite Morphology of Isotactic Polypropylene Investigated by Raman Spectroscopy. Applied spectroscopy 2009, 63, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (2D) carbon-based nanomaterials loading | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO (wt.%) | - | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| rGO (wt.%) | - | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| GNPs (wt.%) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Functional groups assignment | |

|---|---|---|

| 3000-3500 (broad) | O-H | |

| 2773 | v(C-H)+v(O-H)hydrogen bond | |

| 1720 | C=O stretching | |

| 1600 | H2O (1616 cm-1) | |

| C=C (1580 cm-1) graphene layers | ||

| 1380 | COOH | |

| 1220 | C-O-C | |

| 1040 | C-O | |

| 970 | COOH |

| Characterization Technique | GO | rGO | GNPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM (lateral size, μm) |

15-50 | 15-50 | 5-10 |

| IR-ATR (oxidizing groups) |

-OH, -COOH, C=O, -C-O, C-O-C |

-C=O | - |

| XRD (d-spacing, ) |

10.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| TGA (oxidizing groups) |

30% | 8% | - |

| XPS (% atomic concentration) |

C: 69.9 ± 0.5 O: 30.1 ± 0.5 |

C: 94.1 ± 0.5 O: 5.9 ± 0.5 |

C: 98.6 ± 0.1 O: 1.4± 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).