Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

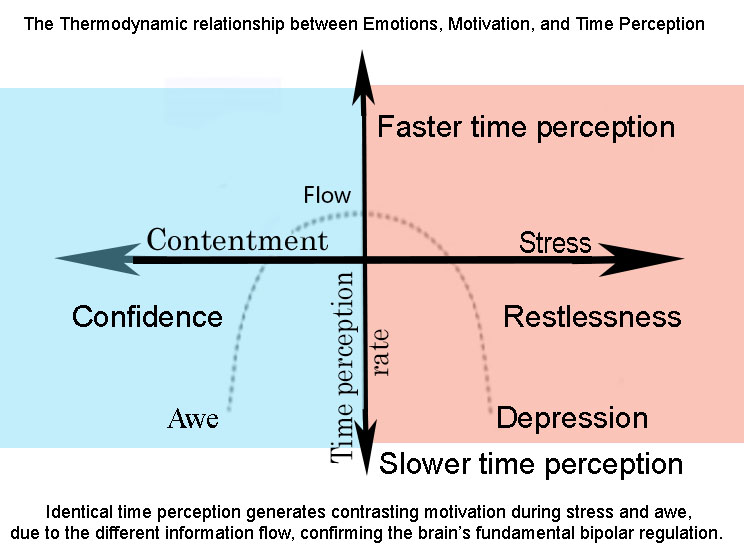

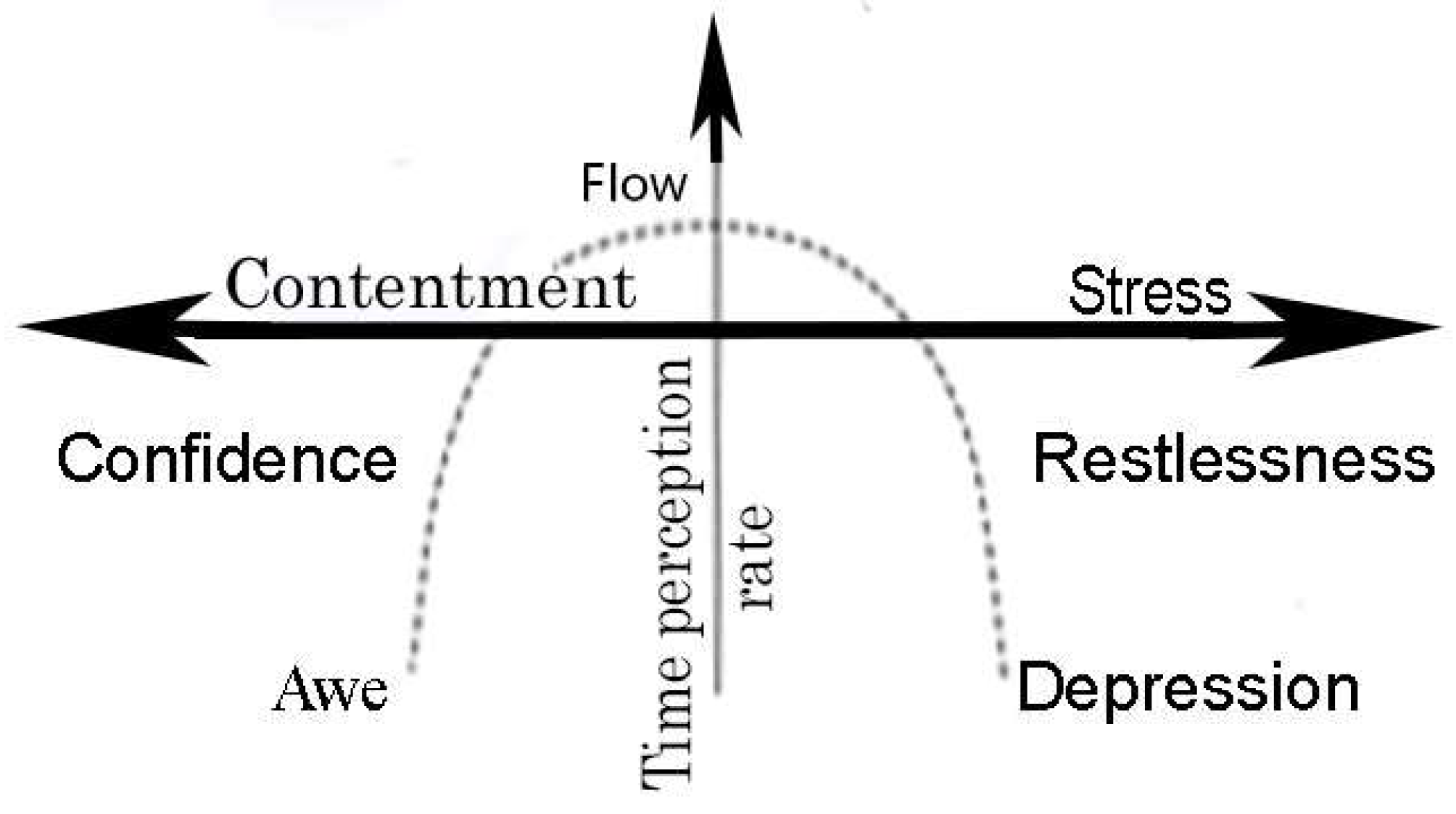

We are introducing a novel thermodynamic emotion model. In this model, emotions are regarded as deviations from equilibrium, akin to fluctuations in body temperature. This bipolar regulation maintains bodily and psychological homeostasis while spurring mental development. Emotional regulation typically occurs through expanding one's perception of time. Positive, low-information content emotions can reduce action drive, but stressful, information-rich conditions can heighten it. However, action accelerates time perception to facilitate fluid action performance, where a unique state of contentment and challenge represents flow. Therefore, time perception can control emotions’ capacity to control motivation. By anchoring psychological processes to the principles of energy and entropy, our model offers a comprehensive bipolar foundation for understanding motivation and behavior. Beyond its theoretical implications, this model also lays the groundwork for addressing mental health conditions resulting from the dysregulation of emotions. It can inspire potential interventions to harness the mind-body connections elucidated in our thermodynamic perspective.

Keywords:

Introduction

Thermo-Emotional Covariations from a Thermodynamic Lens

The Role of Entropy

The Thermodynamics of Time Perception

The Binary Regulation of Higher Cognitive Functions

Discussion and Future Directions

Conclusion

References

- Ache, J.M. , Polsky, J., Alghailani, S., Parekh, R., Breads, P., Peek, M.Y., Bock, D.D., Reyn, CR, & Card, G.M. (2019). Neural Basis for Looming Size and Velocity Encoding in the Drosophila Giant Fiber Escape Pathway. Current Biology, 29, 1073-1081.e4.

- Ahissar E, Assa E. Perception as a closed-loop convergence process. Elife. 2016 ;5:e12830. 9 May. [CrossRef]

- Allingham E, Hammerschmidt D, Wöllner C. Time perception in human movement: Effects of speed and agency on duration estimation. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 2021 Mar;74(3):559-572.

- An, S. J. and Kim, D. (2011). Alterations in serotonin receptors and transporter immunoreactivities in the hippocampus in the rat unilateral hypoxic-induced epilepsy model. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 31(8), 1245-1255. [CrossRef]

- Baez JC (2011) Entropy and Free Energy. arXiv:1102. 2098.

- Bannister, S. , & Eerola, T. (2021). Vigilance and social chills with music: Evidence for two types of musical chills. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.

- Bargh JA, Shalev I. The substitutability of physical and social warmth in daily life. Emotion. 2012 Feb;12(1):154-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Haim, Y. , Kerem, A., Lamy, D., and Zakay, D. (2010). When times slows down: the influence of threat on time perception in anxiety. Cognit. Emot. 24, 255–263.

- Barker, G. R. I.; et al. (2016) Separate elements of episodic memory subserved by distinct hippocampal–prefrontal connections. Nat. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F. 20 January; 12.

- Behm, D. G. , and Carter, T. B. (2020). Effect of exercise-related factors on the perception of time. Front. Physiol. 770. [CrossRef]

- Biderman, N. , Bakkour, A., & Shohamy, D. (2020). What Are Memories For? The Hippocampus Bridges Past Experience with Future Decisions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24, 542-556.

- Briese, E. , 1995. Emotional hyperthermia and performance in humans. Physiology and Behavior 58, 615–618.

- Briese, E. , Cabanac, M., 1991. Stress hyperthermia: physiological arguments that it is a fever. Physlogical Behaviour 49, 1153–1157.

- Brown, R. , Thorsteinsson, E. (2020). Arousal States, Symptoms, Behaviour, Sleep and Body Temperature. In: Brown, R., Thorsteinsson, E. (eds) Comorbidity. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bschor T, Ising M, Bauer M, et al. Time experience and time judgment in major depression, mania, and healthy subjects: a controlled study of 93 subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(3):222–229.

- Cabanac, M. (1999). Emotion and phylogeny. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6(6-7), 176–190.

- Carmona-Halty, M. , Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W. (2019). How Psychological Capital Mediates Between Study–Related Positive Emotions and Academic Performance. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 605-617.

- Colombo, D. , Pavani, J., Fernández-Álvarez, J., García-Palacios, A., & Botella, C. (2021). Savoring the present: The reciprocal influence between positive emotions and positive emotion regulation in everyday life. PLoS ONE, 16.

- Composto, J. , Leichman, E. S., Luedtke, K., & Mindell, J. A. (2021). Thermal comfort intervention for hot-flash related insomnia symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal-aged women: an exploratory study. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 19(1), 38-47.

- Comtesse, H. , Powell S., Soldo A., Hagl M. and Rosner R. Long-term psychological distress of Bosnian War survivors: an 11-year follow-up of former displaced persons, returnees, and stayers. BMC Psychiatry. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly BD, Bruger EL, McKinley PK, Waters CM. Resource abundance and the critical transition to cooperation. J Evol Biol. 2017;30: 750–761. [PubMed]

- Corcoran, J. , Zahnow, R. (2022). Weather and crime: a systematic review of the empirical literature. 11. [CrossRef]

- Craig A., D. (2009). Emotional moments across time: a possible neural basis for time perception in the anterior insula. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1525), 1933–1942. [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, A. , Schwartze, M., & Kotz, S.A. (2022). Cognition through the lens of a body–brain dynamic system. Trends in neurosciences.

- D'Agostino O, Castellotti S, Del Viva MM. (2023) Time estimation during motor activity. Front Hum Neurosci. Apr 21;17:1134027.

- Davydenko, M. , & Peetz, J. (2017). Time grows on trees: The effect of nature settings on time perception. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 54, 20-26.

- Day MV, and Bobocel DR The Weight of a Guilty Conscience: Subjective Body Weight as an Embodiment of Guilt. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8 (7): e69546.

- de Lara, A.C. (2020). Interpreting the High Energy Consumption of the Brain at Rest. Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Debatin, T. (2019). A Revised Mental Energy Hypothesis of the g Factor in Light of Recent Neuroscience. Review of General Psychology, 23, 201—210.

- Deli, E. and Kisvarday, Z. (2020) The Thermodynamic Brain and the Evolution of Intellect: The Role of Mental Energy. [CrossRef]

- Deli, E. K. (2023). "What Is Psychological Spin? A Thermodynamic Framework for Emotions and Social Behavior" Psych 5, no. 4: 1224-1240.

- Deli, E. , Peters, J. and Tozzi, A. (2017) "Relationships between short and fast brain timescales," Cognitive Neurodynamics, vol. 11, no. 539.

- Deli, E. , Peters, J., and Kisvarday, Z. (2021) The thermodynamics of cognition: A Mathematical Treatment, Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. (19) 784-793.

- Deli, E. , Peters, J., and Tozzi, A. (2018) The Thermodynamic Analysis of Neural Computation. J Neurosci Clin Res. 3:1.

- Déli, É. , Peters, J.F., & Kisvárday, Z.F. (2022). How the Brain Becomes the Mind: Can Thermodynamics Explain the Emergence and Nature of Emotions? Entropy, 24.

- Dempsey, W. P. Du, Z., Nadtochiy, A. et al. (2022) Regional synapse gain and loss accompany memory formation in larval zebrafish. PNAS 119 (3) e2107661119.

- Di Domenico, S. I. , and Ryan, R. M. The emerging neuroscience of intrinsic motivation: a new frontier in self-determination research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11:145.16.

- Di Lernia, D. , Serino, S. ( 2018). Feel the Time. Time Perception as a Function of Interoceptive Processing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12.

- Ellard, K.K. , Barlow, D.H., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.L., Gabrieli, J.D., & Deckersbach, T. (2017). Neural correlates of emotion acceptance vs worry or suppression in generalized anxiety disorder. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12, 1009 - 1021.

- Failing, M. , & Theeuwes, J. ( 148, 19–26.

- Farmer, C.G. (2020). Parental Care, Destabilizing Selection, and the Evolution of Tetrapod Endothermy. Physiology, 35 3, 160-176.

- Fazekas, C.L. , Bellardie, M., Török, B. et al. (2021). Pharmacogenetic excitation of the median raphe region affects social and depressive-like behavior and core body temperature in male mice. Life sciences.

- Fossat, P. , Bacqué-Cazenave, J., Deurwaerdère, P. D., Cattaert, D., & Delbecque, J. (2015). Serotonin, but not dopamine, controls stress response and anxiety-like behavior in crayfish, procambarus clarkii.. Journal of Experimental Biology. [CrossRef]

- Frosini, M. , Sesti, C., Palmi, M., Valoti, M., Fusi, F., Mantovani, P., Bianchi, L., Della, C.L., Sgaragli, G., 2000. The possible role of taurine and GABA as endogenous cryogens in the rabbit: changes in CSF levels in heat-stress. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 483, 335–344.

- Gable, P.A. , & Poole, B.D. (2012). Perception Time Flies When You're Having Approach-Motivated Fun: Effects of Motivational Intensity on Time. [CrossRef]

- Gable, P.A. , Wilhelm, A.L., & Poole, B.D. (2022). How Does Emotion Influence Time Perception? A Review of Evidence Linking Emotional Motivation and Time Processing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

- Gladhill, K.A. , Mioni, G., & Wiener, M. (2022). Dissociable effects of emotional stimuli on electrophysiological indices of time and decision-making. PLOS ONE, 17.

- Goffin, K. , & Viera, G. (2023). Emotions in time: The temporal unity of emotion phenomenology. Mind & Language. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.M. , Chauvin, R.J., Van, A.N. et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature 617, 351–359 (2023).

- Grigg, G. , Nowack, J., Bicudo, J., Bal, N.C., Woodward, H.N., & Seymour, R.S. (2021). Whole-body endothermy: ancient, homologous and widespread among the ancestors of mammals, birds and crocodylians. Biological Reviews, 97.

- Groenink, L. , Compaan, J., van der Gugten, J., Zethof, T., van der, H.J., Olivier, B., 1995. Stress-induced hyperthermia in mice Pharmacological and endocrinological aspects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 771, 252–256.

- Haar, A.J.H. , Jain, A., Schoeller, F. et al. Augmenting aesthetic chills using a wearable prosthesis improves their downstream effects on reward and social cognition. Sci Rep 10, 21603 (2020).

- Hall M, Vasko R, Buysse D, Ombao H, Chen Q et al. 2004. Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep. Psychosom. Med. 66:56–62.

- Hallez, Q. , Paucsik, M., Tachon, G., Shankland, R., Marteau-Chasserieau, F., & Plard, M. (2023). How physical activity and passion color the passage of time: A response with ultra-trail runners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

- Herlambang, M. B. , Cnossen, F., Taatgen, N. A. (2021) The effects of intrinsic motivation on mental fatigue. PLOS.

- Hesp, C. , Smith, R., Parr, T., Allen, M., Friston, K., & Ramstead, M.J. (2021). Deeply Felt Affect: The Emergence of Valence in Deep Active Inference. Neural Computation, 33, 1-49.

- Hollis, F. , van der Kooij, M.A., Zanoletti, O., Lozano, L., Cantó, C., & Sandi, C. (2015). Mitochondrial function in the brain links anxiety with social subordination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 15486 - 15491.

- Hosseini Houripasand, M. , Sabaghypour, S., Farkhondeh Tale Navi, F., & Nazari, M.A. (2023). Time distortions induced by high-arousing emotional compared to low-arousing neutral faces: an event-related potential study. Psychological Research, 1-12.

- Huang, J. Greater brain activity during the resting state and the control of activation during the performance of tasks. Sci Rep 9, 5027 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. , Zhang, J. G. ( 2020). Temporal circuit of macroscale dynamic brain activity supports human consciousness. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz0087.

- Inagaki, T.K. , Hazlett, L.I., & Andreescu, C. (2019). Naltrexone alters responses to social and physical warmth: implications for social bonding. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14, 471 - 479.

- Jizba P, Arimitsu T. 2001. The world according to Renyi: thermodynamics of fractal systems. AIP Conference Proceedings, 597, 341-348.

- Kao, F-C., Wang, SR. and Chang, Yj.(2015) Brainwaves Analysis of Positive and Negative Emotions. ISAA, (12): 1263–1266.

- Kataoka, N. , Shima, Y. ( 2020). A central master driver of psychosocial stress responses in the rat. Science 367, 1105–1112.

- Keller, A.S. , Leikauf, J. ( 2019). Paying attention to attention in depression. Translational Psychiatry, 9.

- Kluger, M. J. , O'Reilly, B. J., Shope, T. R., & Vander, A. J. (1987). Further evidence that stress hyperthermia is a fever. Physiology &Amp; Behavior, 39(6), 763-766. [CrossRef]

- Lehockey, K.A. , Winters, A.R., Nicoletta, A.J. et al. The effects of emotional states and traits on time perception. Brain Inf. 5, 9 (2018).

- Llinás, R. Paré, D. and M. (Ed.), "The brain as a closed system modulated by the senses.," in The churchlands and their critics, Cambridge, Mass., Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

- Lowry, C. A. , Lightman, S. L., and Nutt, D. J. (2009). That warm fuzzy feeling: brain serotonergic neurons and the regulation of emotion. J. Psychopharmacol. 23, 392–400.

- Ma, A.C. , Cameron, A.D. & Wiener, M. Memorability shapes perceived time (and vice versa). Nat Hum Behav (2024). [CrossRef]

- Madden, C. J. , & Morrison, S. F. ( 696, 225–232.

- Mason, A.E. , Kasl, P., Soltani, S. et al. Elevated body temperature is associated with depressive symptoms: results from the TemPredict Study. Sci Rep 14, 1884 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, R. , Van Cutsem, J., Roelands, B. (2020) Endurance exercise-induced and mental fatigue and the brain, Experimental Psychology.

- Mitchell, J.M. , Weinstein, D., Vega, T.A., & Kayser, A.S. (2015). Dopamine, time perception, and future time perspective. Psychopharmacology, 235, 2783 - 2793.

- Moe, R.O. , Bakken, M., 1997. Effects of handling and physical restraint on rectal temperature, cortisol, glucose and leucocyte counts in the silver fox (Vulpes vulpes). Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 38, 29–39.

- Morimoto, A. , Watanabe, T., Morimoto, K., Nakamori, T., & Murakami, N. (1991). Possible involvement of prostaglandins in psychological stress-induced responses in rats.. The Journal of Physiology, 443(1), 421-429. [CrossRef]

- Nashiro, K. , Min, J., Yoo, H.J., et al. (2022). Increasing coordination and responsivity of emotion-related brain regions with a heart rate variability biofeedback randomized trial. Cognitive, affective & behavioral neuroscience.

- Nestler, E.J. , & Russo, S. J. ( 112, 1911–1929.

- Northoff, G. "Is Our Brain an Open or Closed System? Prediction Model of Brain and World–Brain Relation," in The Spontaneous Brain, MIT press, 2018.

- Northoff, G. , & Tumati, S. (2019). "Average is good, extremes are bad" – Non-linear inverted U-shaped relationship between neural mechanisms and functionality of mental features. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 11-25.

- Nowack, J. , Giroud, S., Arnold, W., & Ruf, T. (2017). Muscle Non-shivering Thermogenesis and Its Role in the Evolution of Endothermy. Frontiers in Physiology, 8.

- Nutt, D.J. (1999). Care of depressed patients with anxiety symptoms. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 60 Suppl 17, 23-7; discussion 46-8.

- Oka T, Oka K, Hori T. Mechanisms and mediators of psychological stress-induced rise in core temperature. Psychosom Med. 2001 May-Jun;63(3):476-86. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, J. , & Schoth, A. (2022). The Mental Maxwell Relations: A Thermodynamic Allegory for Higher Brain Functions. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

- Park, J. , & Hadi, R. (2020). Shivering for Status: When Cold Temperatures Increase Product Evaluation. Journal of Consumer Psychology.

- Parrott, R.F. , Vellucci, S.V., Forsling, M.L., Goode, J.A., 1995. Hyperthermic and endocrine effects of intravenous prostaglandin administration in the pig. Domestic Animal Endocrinology 12, 197–205.

- Raichle, ME. Two views of brain function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010 Apr;14(4):180-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raison, C. L. , Hale, M. W., Williams, L. E., Wager, T. D., and Lowry, C. A. (2015). Somatic influences on subjective well-being and affective disorders: the convergence of thermosensory and central serotonergic systems. Front. Psychol. 5:1589.

- Remmers, C. & Zander, T. Why you don't see the forest for the trees when you are anxious: Anxiety impairs intuitive decision making. Clin Psychol Sci, 2018, 6, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Robbe, D. (2023). Lost in time: Relocating the perception of duration outside the brain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 153: 105312.

- Rudd, M. , Vohs, K.D., & Aaker, J.L. (2012). Awe Expands People's Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-being. Psychological Science, 23, 1130 - 1136.

- Rutrecht, H.M. , Wittmann, M., Khoshnoud, S., & Igarzábal, F.A. (2021). Time Speeds Up During Flow States: A Study in Virtual Reality with the Video Game Thumper. Timing & Time Perception.

- Thönes, S. Oberfeld, D. Time perception in depression: A meta-analysis, Journal of Affective Disorders 175, 359-372, 12 January.

- Sadowski, S. , Fennis, B.M., & van Ittersum, K. (2020). Losses tune differently than gains: how gains and losses shape attentional scope and influence goal pursuit. Cognition and Emotion, 34, 1439 - 1456.

- Safron, A. The Radically Embodied Conscious Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: From Free Energy to Free Will and Back Again. Entropy. 2021; 23(6):783.

- Schoeller, F. , & Perlovsky, L.I. (2016). Aesthetic Chills: Knowledge-Acquisition, Meaning-Making, and Aesthetic Emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 7.

- Seebacher, F. (2020). Is Endothermy an Evolutionary By-Product? Trends in ecology & evolution, 35 6, 503-511.

- Seebacher, F. (2009). Responses to temperature variation: integration of thermoregulation and metabolism in vertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology, 212, 2891. [Google Scholar]

- Şen B, Kurtaran NE, Öztürk L. The effect of 24-hour sleep deprivation on subjective time perception. Int J Psychophysiol. 2023 Oct;192:91-97. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. Source Coding with a Fidelity Criterion. Proc. IRE 1959.

- Simen P, Matell M. Why does time seem to fly when we're having fun? Science. 2016 Dec 9;354(6317):1231-1232.

- Singer, W. (2021). Recurrent dynamics in the cerebral cortex: Integration of sensory evidence with stored knowledge. PNAS, 118.

- Soares, S. , Atallah, B.V., & Paton, J.J. (2016). Midbrain dopamine neurons control judgment of time. Science, 354, 1273 - 1277.

- Spapé, M.M. , Harjunen, V.J., & Ravaja, N. (2021). Time to imagine moving: Simulated motor activity affects time perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 29, 819 - 827.

- Sridhar, V.H. , Li, L., Gorbonos, D., Nagy, M., Schell, B.R., Sorochkin, T., Gov, N.S., & Couzin, I.D. (2021). The geometry of decision-making in individuals and collectives. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118.

- Stanghellini G, Ballerini M, Presenza S, Mancini M, Northoff G, Cutting J, (2016) Abnormal time experiences in major depression. An empirical qualitative study. [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, NS, Mountstephens, J., Teo, J. (2020). "EEG-Based Emotion Recognition: A State-of-the-Art Review of Current Trends and Opportunities," Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. Article ID 8875426, p19, 2020.

- Tan, C.L. , & Knight, Z. A. ( 98, 31–48.

- Terlouw, E.M. , Kent, S., Cremona, S., Dantzer, R., 1996. Effect of intracerebroventricular administration of vasopressin on stress-induced hyperthermia in rats. Physiology and Behavior 60, 417–424.

- Toren, I. , Aberg, K. ( 2020). Prediction errors bidirectionally bias time perception. Nature Neuroscience, 1–5.

- Torres P, E. P. , Torres, E. A., Hernández-Álvarez, M., & Yoo, S. G. (2020). EEG-Based BCI Emotion Recognition: A Survey. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 20(18), 5083.

- Toso, A. , Fassihi, A. E. ( 2020). A sensory integration account for time perception. PLoS Computational Biology, 17.

- Tsao, A. , Sugar, J. I. ( 561(7721), 57–62.

- van der Heyden, J.A. , Zethof, T.J., Olivier, B., 1997. Stress-induced hyperthermia in singly housed mice. Physiology and Behavior 62, 463–470.

- van Hedger K, Necka EA, Barakzai AK, Norman GJ. The influence of social stress on time perception and psychophysiological reactivity. Psychophysiology. 2017 May;54(5):706-712. [CrossRef]

- van Maanen, L. , van der Mijn, R., van Beurden, M.H.P.H. et al. Core body temperature speeds up temporal processing and choice behavior under deadlines. Sci Rep 9, 10053 (2019).

- Varley, Thomas F., Robin Carhart-Harris, Leor Roseman, David K. Menon, and Emmanuel A. Stamatakis. 2020. "Serotonergic Psychedelics LSD & Psilocybin Increase the Fractal Dimension of Cortical Brain Activity in Spatial and Temporal Domains." NeuroImage 220 (October): 117049.

- Wainio-Theberge, S. , & Armony, J. L. ( 2023). Antisocial and impulsive personality traits are linked to individual differences in somatosensory maps of emotion. Scientific Reports, 13.

- Wang D., J. , Jann K., Fan C., et al., (2018) Neurophysiological basis of multiscale entropy of brain complexity and its relationship with functional connectivity. Front. Neurosci. 12:352.

- Wang, J. , & Lapate, R.C. (2023). Emotional state dynamics impacts temporal memory. bioRxiv.

- WILLIAMS, L. E. and Bargh, J. A. (2008) Experiencing Physical Warmth Promotes Interpersonal Warmth. Science, 322(5901):606.

- Wise, T. , Marwood, L., Perkins, A. M. et al. (2017) nstability of default mode network connectivity in major depression: a two-sample confirmation study. Transl. Psychiatry 25;7(4) :e1105.

- Yang, S. , Zhao, Z., Cui, H. (2019). Temporal Variability of Cortical Gyral-Sulcal Resting State Functional Activity Correlates With Fluid Intelligence. Frontiers in neural circuits, 13, 36.

- Zanin, M. , Güntekin, B., Aktürk, T., Hanoğlu, L., & Papo, D. (2019). Time Irreversibility of Resting-State Activity in the Healthy Brain and Pathology. Frontiers in Physiology, 10.

- Zelena, D. , Menant, O., Andersson, F., & Chaillou, E. (2018). Periaqueductal gray and emotions: the complexity of the problem and the light at the end of the tunnel, the magnetic resonance imaging. Endocrine Regulations, 52, 222 - 238.

- Zmigrod, L. , Zmigrod, S., Rentfrow, P.J., & Robbins, T. (2019). The psychological roots of intellectual humility: The role of intelligence and cognitive flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 200-208.

| Experience | ||

|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Positive arousal | Stress |

| Time perception increases (Dilation) Arousal | Parasympathetic | Action motivation |

| Time perception decreases (Compression) Action | Flow | Sympathetic |

| Physiological symptoms (shivering, sweating) | Accomplishment | Shame, fear |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).