1. Introduction

Golf has experienced a rapid transformation from an elite activity to a widely popular sport with an ever-growing number of participants [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Traditionally considered a game for the privileged, golf is now accessible to a broader demographic, leading to increased global engagement [

5]. This shift is evidenced by the rise in public golf courses [

6], the proliferation of golf programs targeting various age groups [

6], and the inclusion of golf in educational curriculums [

7]. The democratization of golf signifies not only a change in participation but also a broader acceptance of the sport within mainstream culture [

8].

Despite its growing popularity, the technical aspect of golf continues to overshadow athletic preparation. Mastery of swing mechanics, precision, and consistency remain paramount, with the golf instructor being central throughout a golfer’s career [

9,

10]. From youth development programs to professional training, the instructor’s role is crucial, often at the expense of comprehensive athletic conditioning [

11]. This focus on technique over the physical conditioning reflects the traditional view of golf as a skill-dominant sport, where meticulous practice and refinement of technique are perceived as the keys to success [

12,

13]. Only in recent years, with an increased understanding of the physical demands and determinants of the game, strength and conditioning has become an integral component of many elite players’ practice [

10,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

In golf-specific athletic training, alongside general muscular strength and power exercises, there is a strong emphasis on training leg-hip, trunk power and grip strength [

10,

15,

16,

21]. However, this often overlooks the proprioceptive and propulsive functions of the feet, which are fundamental in initiating and controlling movements, providing stability, and generating propulsive force [

24,

25,

26,

27]. In other sports, particularly those with complex, coordinated ground-based movements, training programs place a significant importance on the role of the feet [

24]. In golf, this oversight can lead to suboptimal performance and potential injury, as the foundational support and movement efficiency may be partially compromised [

28].

In contrast, in many other sports, the integration of athletic preparation with technique training is standard practice. From the outset, athletes are trained with a focus on multilateral development and the conditioning of individual physical and coordinative capacities [

29]. This comprehensive approach is often advised to precede the progressive learning of specific technical skills [

30,

31]. In athletics, the role of the feet has been extensively studied and is identified as crucial for performance, fine motor control, and joint stability throughout the lower limb’s kinetic chain [

32]. As a result, specific exercises aimed at enhancing foot function are integral to training across all disciplines within track and field [

33].

The golf swing shares several biomechanical similarities with throwing motions in athletics, such as javelin, shot put, and baseball pitching. These disciplines demonstrate the effectiveness of a progressive bottom-up timing sequence, where movements are initiated from the ground with the action of the feet and progress upwards through the body’s kinetic chain [

34,

35,

36,

37]. This sequential activation ensures efficient transfer of energy from the lower to the upper extremities, maximizing the velocity at the chain’s endpoint at the moment of release and enhancing throw distance, while reducing the risk of injury. In golf, this principle may help maximize clubhead speed, resulting in an efficient and powerful swing [

38]. Understanding and applying this biomechanical principle could significantly improve golf training and performance by emphasizing the importance of foot mechanics.

In this study, we introduce a new paradigm in golf athletic training and swing technique that emphasizes the proprioceptive and propulsive function of the feet. Specifically, we developed and administered a proprioceptive exercise sequence targeting foot mechanics, defined by a rhythmic, sequential pattern of pressure and shear ground actions exerted by the rearfoot and forefoot of both the lead and trail feet. After this conditioning phase, experienced golfers were instructed to perform successive swing sessions on professional golf courses, integrating the learned motor sequence into their swing technique. To evaluate the effectiveness of this intervention, we recorded and analyzed joint, club, and ball kinematics, as well as ground pressures exerted by each foot, during the two post-conditioning swing sessions and during a reference session conducted prior to the conditioning intervention with their standard technique. We hypothesize that this intervention, and its continued application in subsequent swing sessions, will aid golfers in acquiring, consolidating, and automating a refined swing technique, ultimately improving performance. Specifically, we hypothesize that the most relevant performance-related swing parameters—namely, peak pressure in the lead foot, club speed, and ball speed—will progressively increase during the modified swing sessions following the conditioning intervention, compared to the reference session.

The results of this study could offer valuable insights into the development of young golfers and the optimization of athletic preparation and performance for professionals. The integration of foot-focused exercises into golf training could help bridge the gap between technical mastery and athletic prowess, leading to enhanced performance and injury prevention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-five healthy male golf players were recruited from Italian golf clubs. Participant characteristics relevant to the study are summarized in

Table 1. Only currently active golf players aged between 18 and 65 years, with at least 5 consecutive years of competitive experience and 2 hours of practice per week, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included musculoskeletal injuries, a history of limb and trunk pathologies, and the inability to perform the golf swing without pain and with proper form and technique. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and international standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and received approval from the ethics committee of the University of Perugia. All participants provided written informed consent for their inclusion in the study prior to participation.

2.2. Proprioceptive Intervention

All participants underwent a 3-minute specific foot proprioceptive intervention. Each player assumed his usual starting swing position. From this position, the feet perform a rhythmic sequence of actions, structured in four phases. For the right-handed golfer, the action begins with the left forefoot producing ground pressure and a shearing force (horizontal push) directed laterally initiating a bottom-up chain of movement in the left lower limb—eversion of the rear foot joints (subtalar and transverse tarsal joints), knee flexion, and hip external rotation—followed by right pelvic rotation (phase 1). The left foot action also causes a partial shifts of body weight towards the right rear foot, promoting rear foot inversion, partial knee extension, and internal hip rotation in the right lower limb, with further right pelvic rotation (phase 2). The action then proceeds in the opposite direction in the next two phases. The right forefoot produces ground pressure and a horizontal shearing force directed laterally, engendering rear foot eversion and hip external rotation in the right lower limb, changing pelvic rotation from right to left (phase 3). This right foot action simultaneously shifts body weight towards the left rear foot, with rear foot inversion, knee extension, and hip internal rotation in the left lower limb, promoting further left pelvic rotation (phase 4). During these four phases, the system sequentially loads from the bottom up with torsional elastic energy in the transverse plane, which is then released, again from the bottom up, as kinetic energy useful for propulsion. During the entire sequence, the exerciser should avoid lateral trunk tilt, and strive to maintain knee alignment limiting varus/valgus and internal/external rotations, thus protecting both the knee and lower back joints. For the left-handed golfer, the actions are reversed, starting with the right forefoot.

To help participants execute the pattern smoothly, we tell them to imagine an X between the foot support points. The first line of the X (for right-handed golfers) starts from the left forefoot (vertex 1) and ends at the right rear foot (vertex 2). The second line of the X (which intersects the first in the center) starts from the right forefoot (vertex 3) and ends at the left rear foot (vertex 4). Participants were instructed to rhythmically and sequentially exert ground actions with their feet (pressure and shearing force) at points 1, 2, 3, and 4.

In the first minute of conditioning, the four phases are performed at a very slow pace to become familiar with the exercise, gradually acquiring the movement pattern. In the second minute of conditioning, the four phases are performed with a smoother and faster rhythm to consolidate and then automate the pattern, creating a continuous sequence. In the third and final minute, the sequence is performed by each golfer with the timing of their own swing. Throughout the intervention, a 5-second pause was taken between each complete cycle (four phases). This exercises progression was designed to acutely modify suboptimal foot automatisms ingrained over time.

The duration of the 3-minute foot proprioceptive conditioning intervention was considered sufficient for enabling experienced golfers to voluntarily integrate the practiced foot motor sequence into their swing technique during swing sessions conducted immediately after the intervention (refer to the following "Testing Session" section). Extending the intervention duration could potentially induce fatigue, which might negatively impact performance in these sessions.

2.3. Testing Session

The testing sessions were held at the “Golf della Montecchia” course (27 holes, Par 72, 6318 meters; Selvazzano dentro Padova, Italy) and the “Golf Club Perugia” course (18 holes, Par 71, 5763 meters; Perugia, Italy). Participants were asked to perform their usual pre-competition warm-up routine. Afterwards, they performed three separate sessions of five swing shots using a 6-iron golf club: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). During the second and third sessions, participants were instructed to integrate the sequence of foot actions practiced during the proprioceptive intervention into their swing. In the three minutes between the second and third sessions, participants were asked to focus on the sensations experienced in the second session with the new movement technique. In each session, participants were free to choose the rest period (typically less than 30 seconds) between one shot and the next.

2.4. Data Recording Ana Processing

The club and ball kinematics during the three swing sessions were recorded using the markerless Trackman launch monitor (Vedbæk, Denmark), which is equipped with synchronized high-speed (4,600 fps) dual cameras and 24 GHz dual Doppler radar technology. Although the Trackman system captures dozens of parameters, only the speed of the club head at ball impact (club speed) and the initial ball speed after the impact (ball speed) were analyzed in this study. This decision is acknowledged in the discussion section.

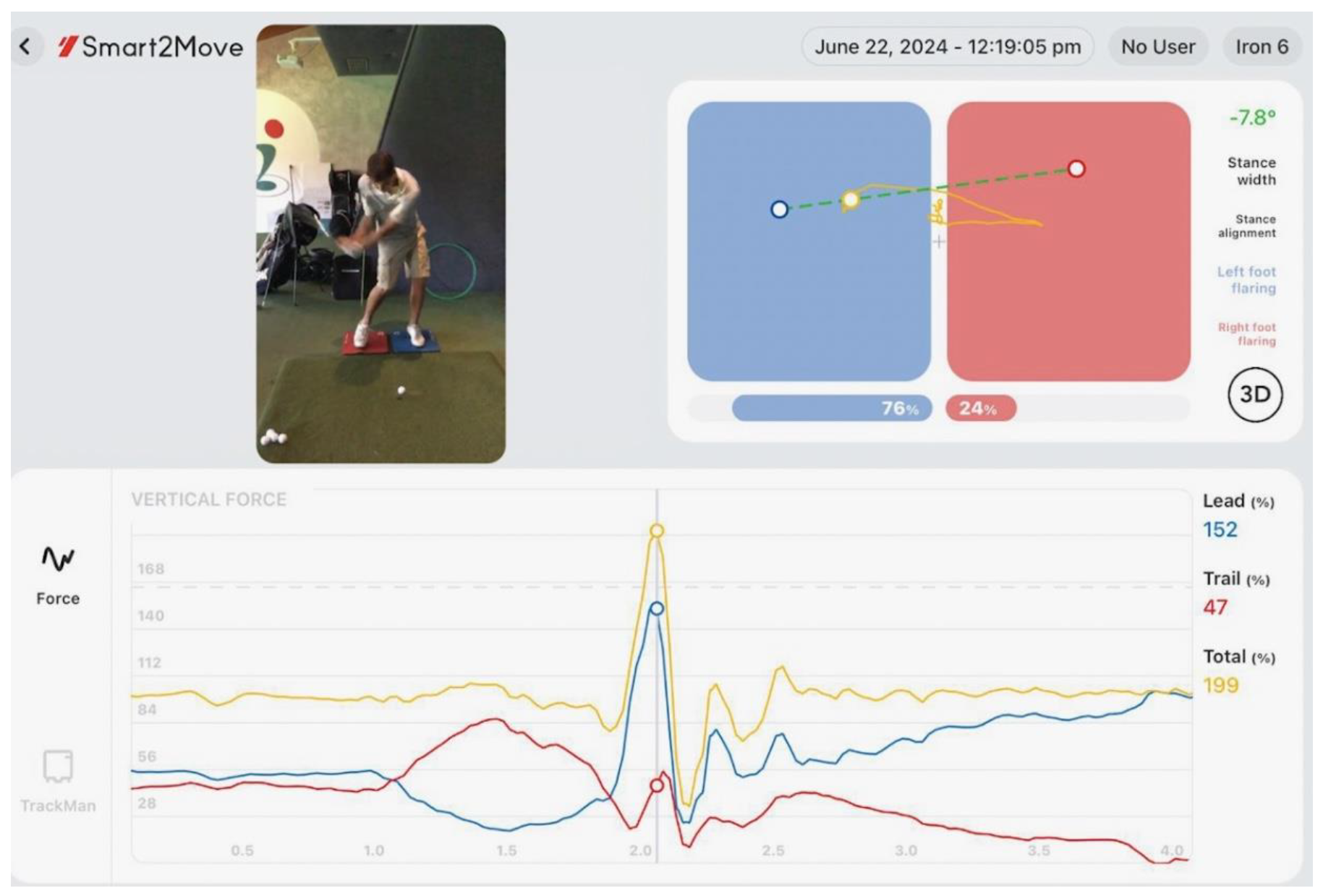

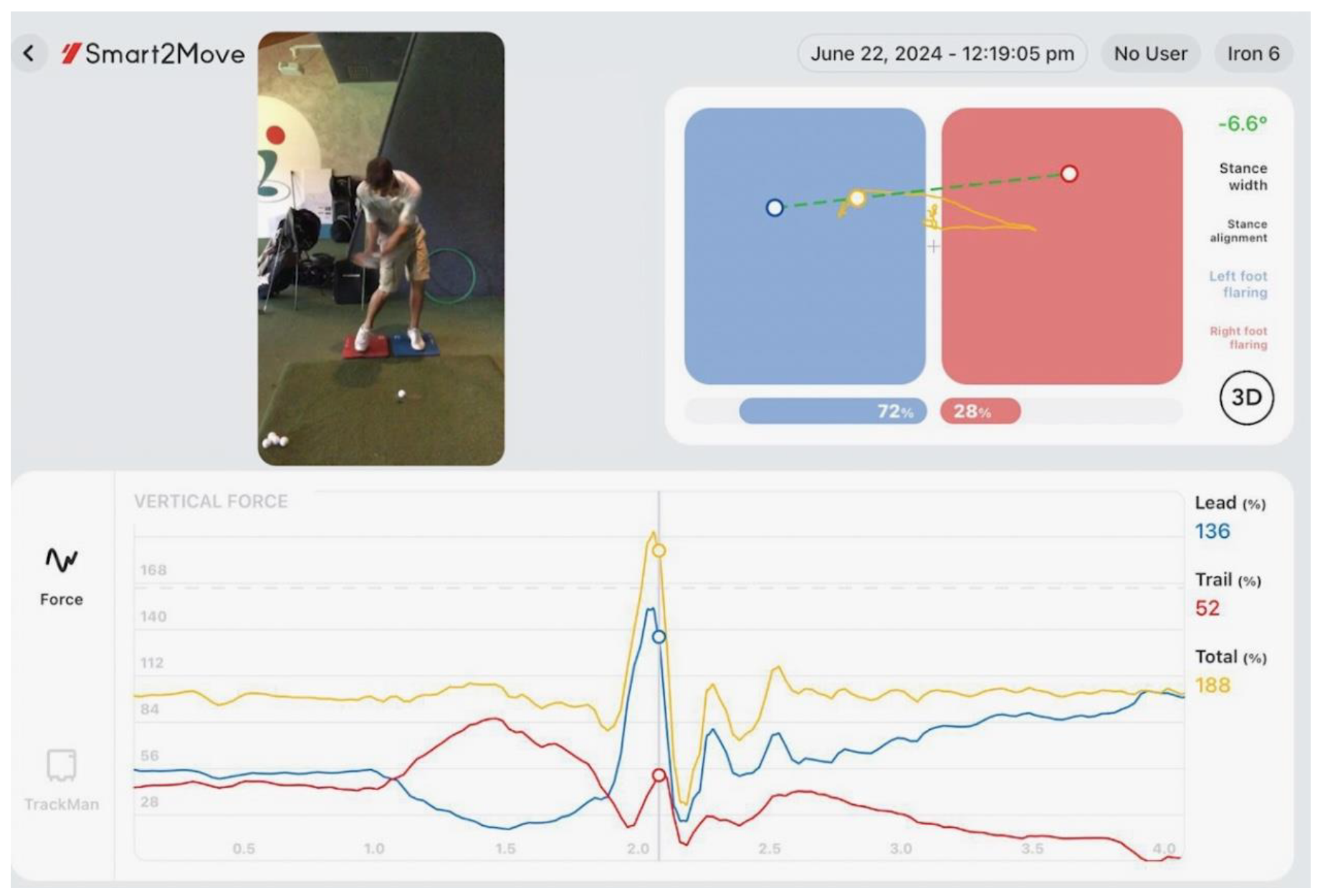

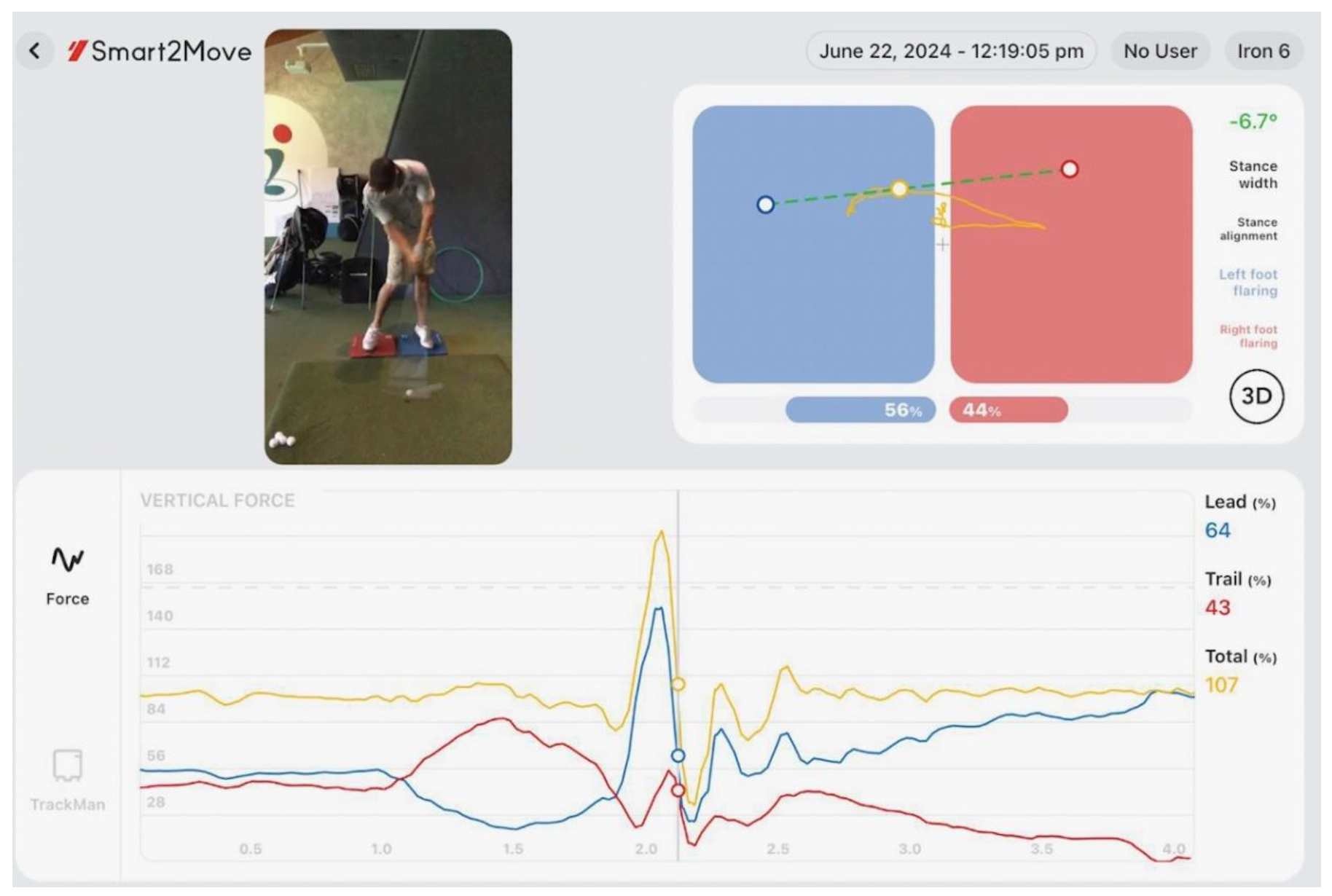

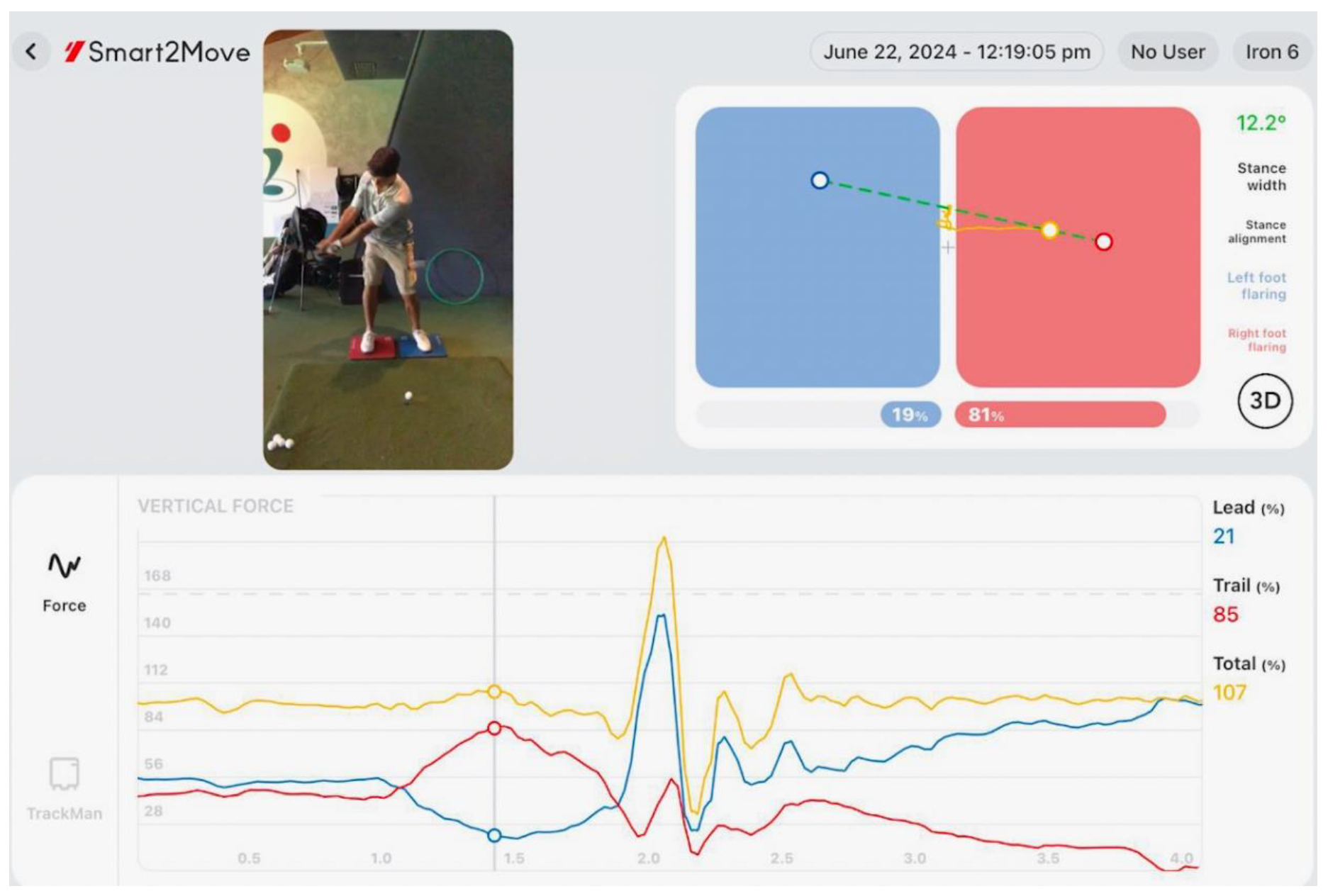

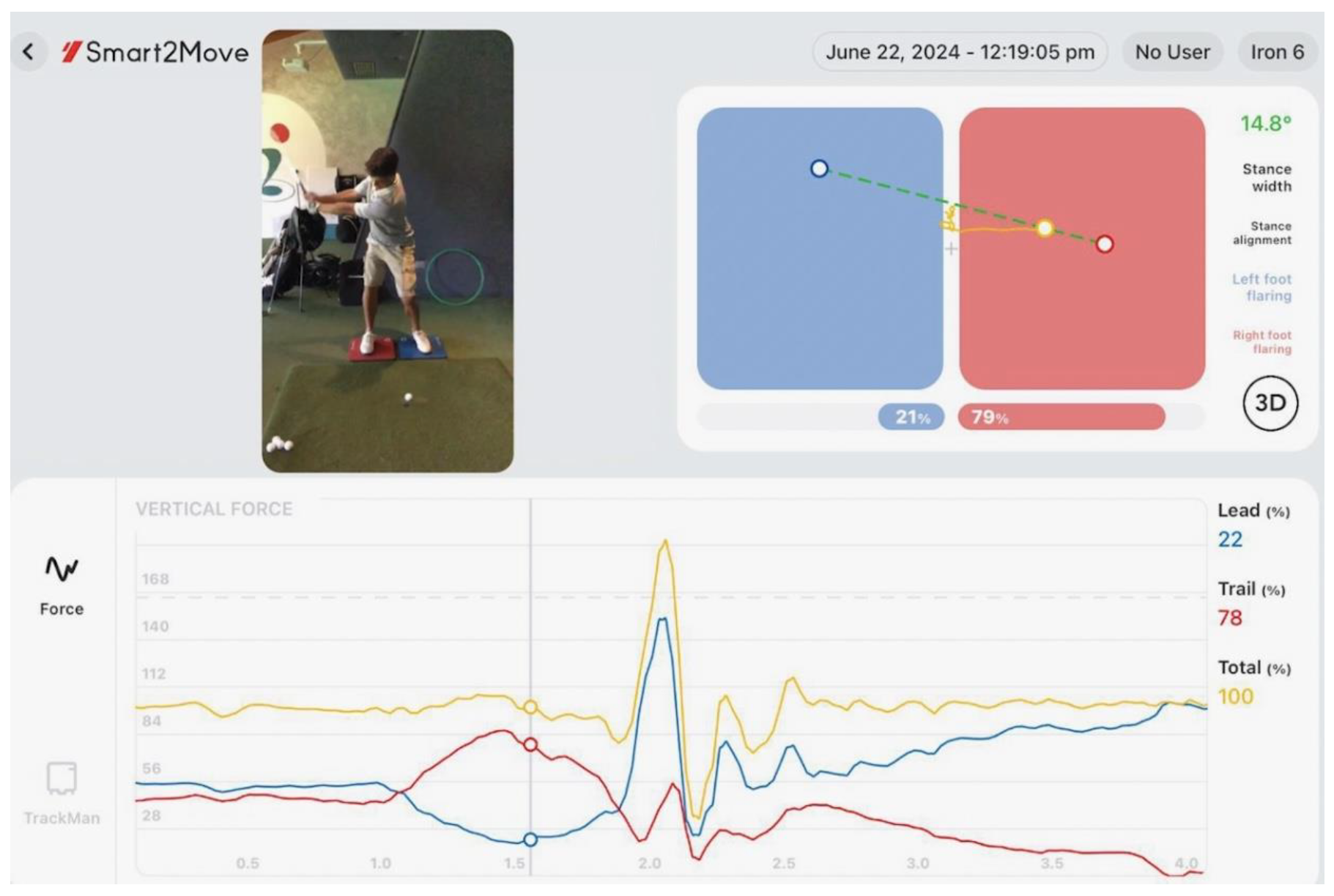

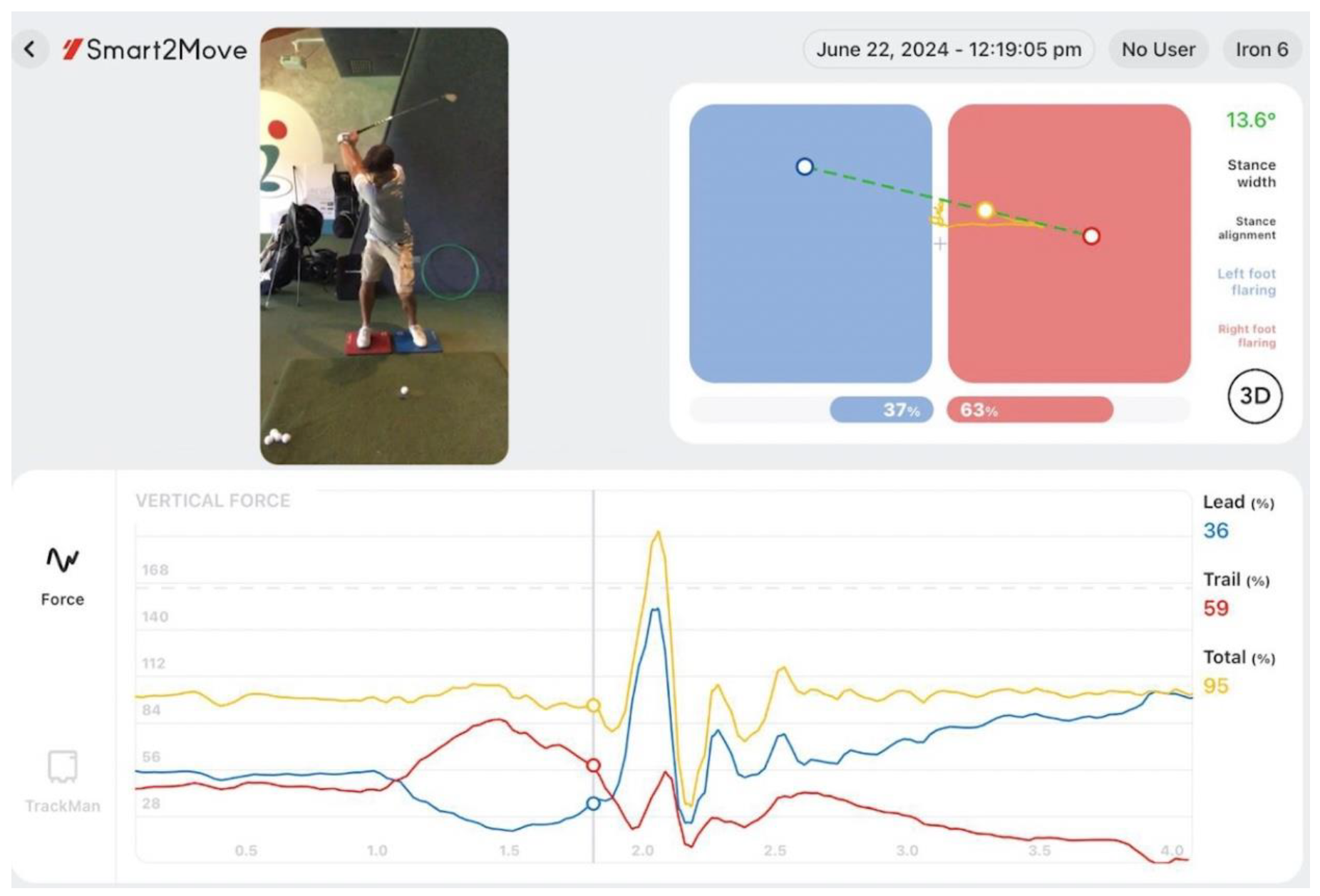

A Smart2Move Dual Force Plate system (Allschwil, Switzerland) equipped with a time-synchronized camera capturing high-resolution images at a 240 fps sampling rate was used to record independent left and right foot vertical ground reaction (vGR) forces and centers of pressure, global vGR force and center of pressure, lateral weight distribution, foot flare, and stance width. The native software of data analysis considers 7 reference positions during the swing action (see Appendix): P1: starting position, P2: club parallel to the ground in the backswing (loading); P3: left arm parallel to the ground in the backswing; P4: apex of backswing; P5: left arm parallel to the ground in the downswing (descent, shot), P6: club parallel to the ground in the downswing, P7: impact of the club with the ball.

The integration of the Smart2Move and TrackMan data enables correlating the causes, ground reaction forces measured by the force plates, and the consequences on club data and ball flight kinematics measured with the launch monitor.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

An ANOVA design was employed to analyze the data samples. The ANOVA assumptions of sphericity, normality, and homogeneity of variance were verified with the tests of Mauchly, Shapiro–Wilk, and Levene, respectively. When necessary to meet these assumptions, probabilities were estimated using the Greenhouse–Geisser and Huynh–Feldt corrections, and/or data were transformed with the natural logarithm (ln) function. Descriptive statistics, presented as mean ± SD, consistently refer to the untransformed data, even if the analysis was performed on transformed data. Trackman and force plate data samples were analyzed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, with time (before (t0), soon after (t1), and three minute after (t3) the proprioceptive training intervention) as a 3-level within-subject factor. Post hoc analysis was run via the Scheffé test.

In addition to calculating the average performance at different stages of the treatment (t0, t1, and t2) for the entire group, it is also of interest to calculate the individual differences between the performances at two different stages of the treatment for each athlete, average these differences over the participants, and perform one-sample t-tests on these sets of data (null hypothesis mean=0, alternative hypothesis mean≠0). These tests could provide additional information to the ANOVA analysis.

In all statistical tests, the significance level was set at p < 0.05. The Origin software package was used for statistical calculations.

3. Results

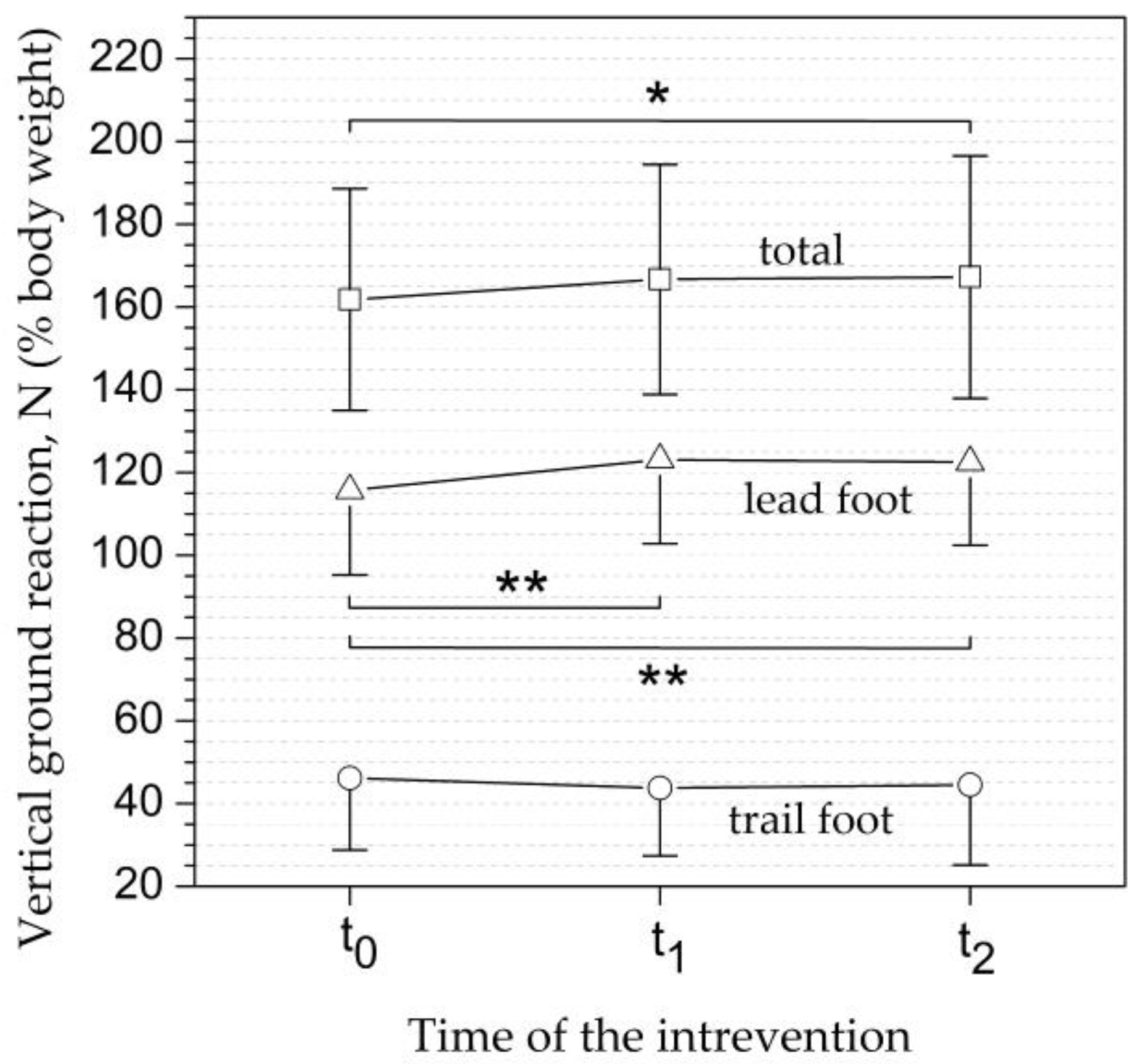

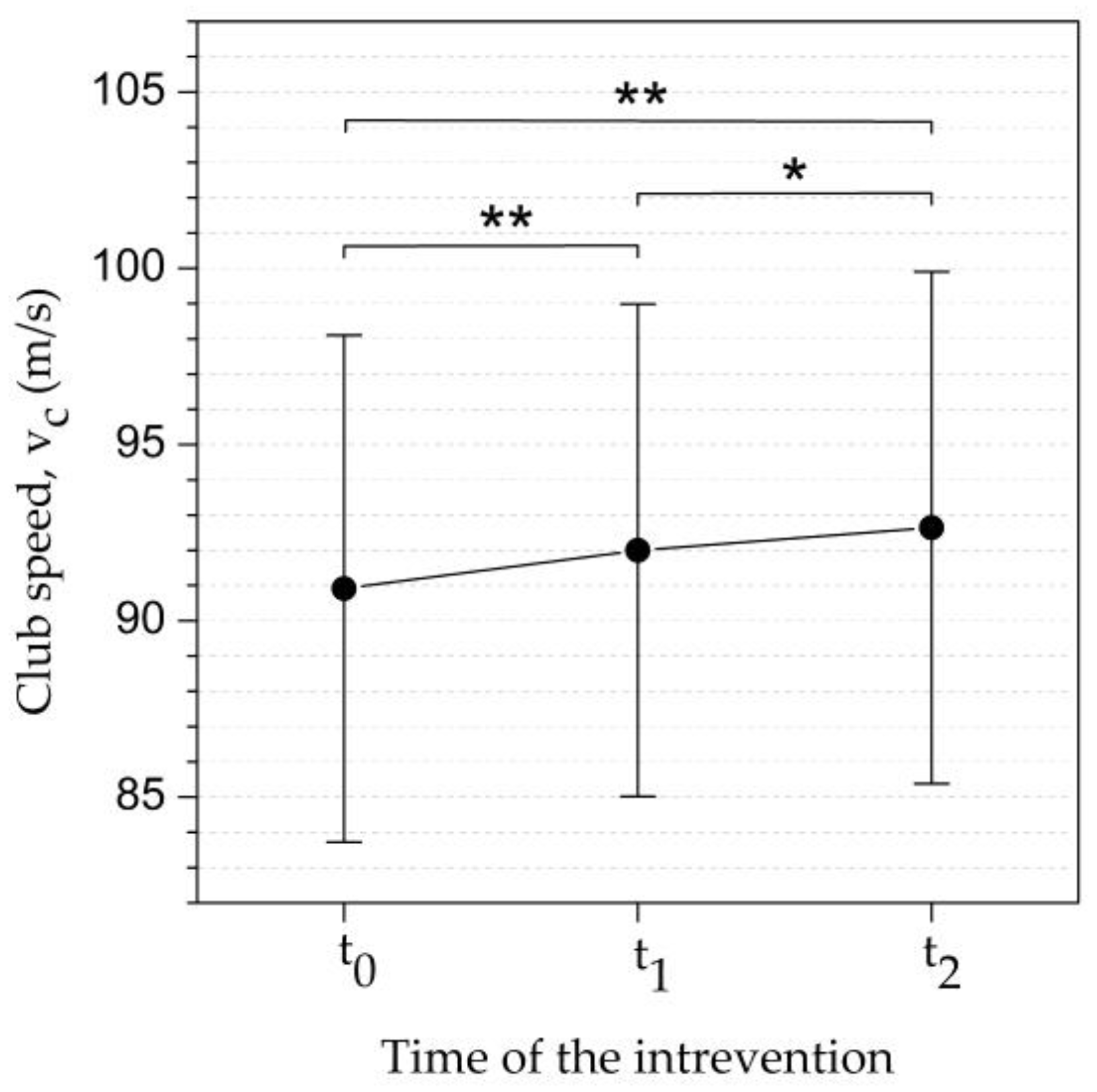

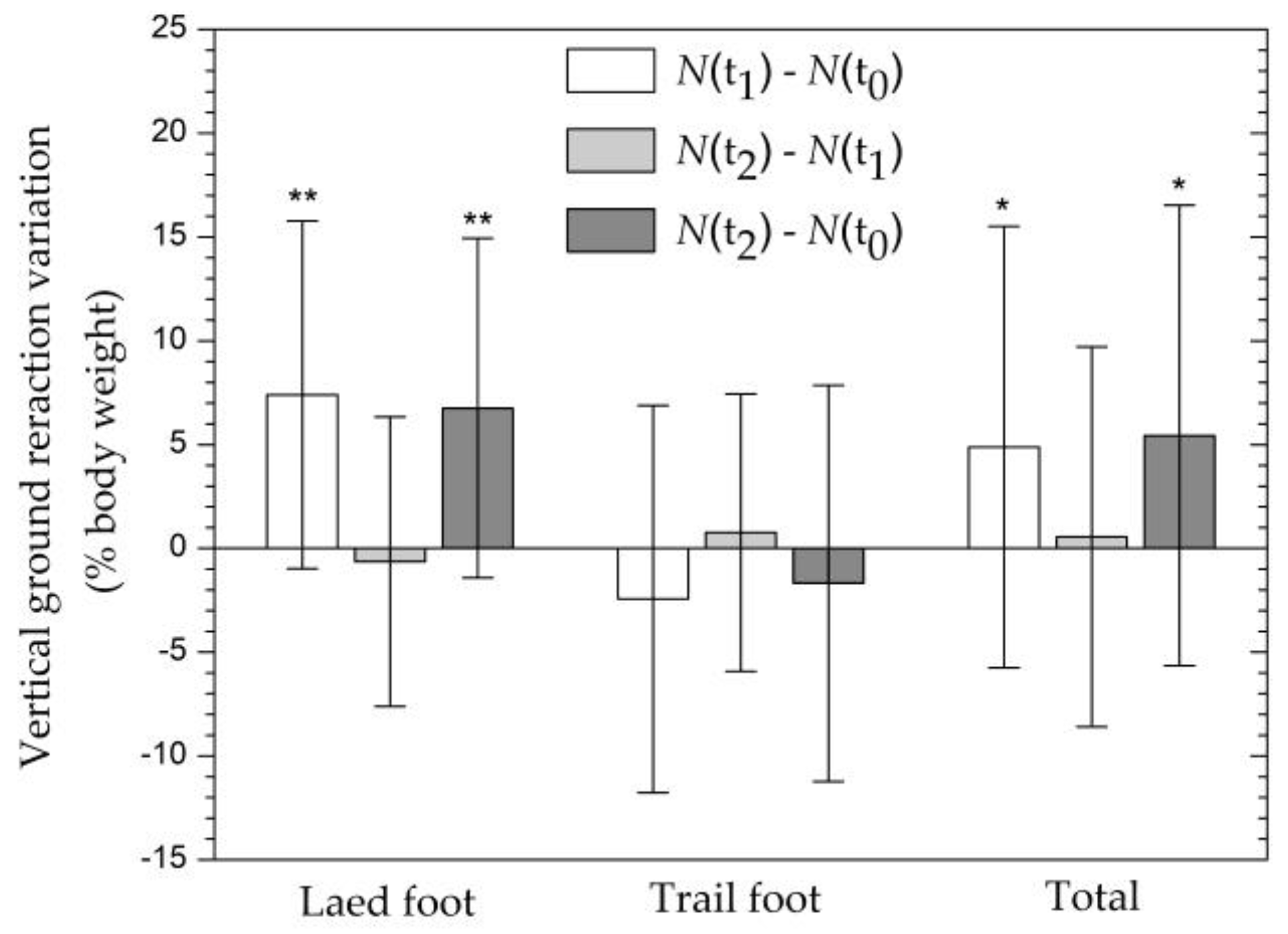

ANOVA outcomes revealed that the proprioceptive intervention had a significant effect on the peak vGR of the lead foot (p < 0.001), total peak vGR (p = 0.02), club speed (p < 0.001), and ball speed (p = 0.004). Post-hoc analysis highlighted that these dependent variables display different changes across the three successive swing sessions. The peak vGR of lead foot increases from t

0 to t

1 (p < 0.001), but does not show further increments from t

1 to t

2 (

Figure 1); total peak vGR only reaches a significant increment over the entire treatment, from t

0 to t

2 (

Figure 1); club speed increases from t

0 to t

1 (p < 0.001) and continues to increase, though to a lesser extent, from t

1 to t

2 (p = 0.02) (

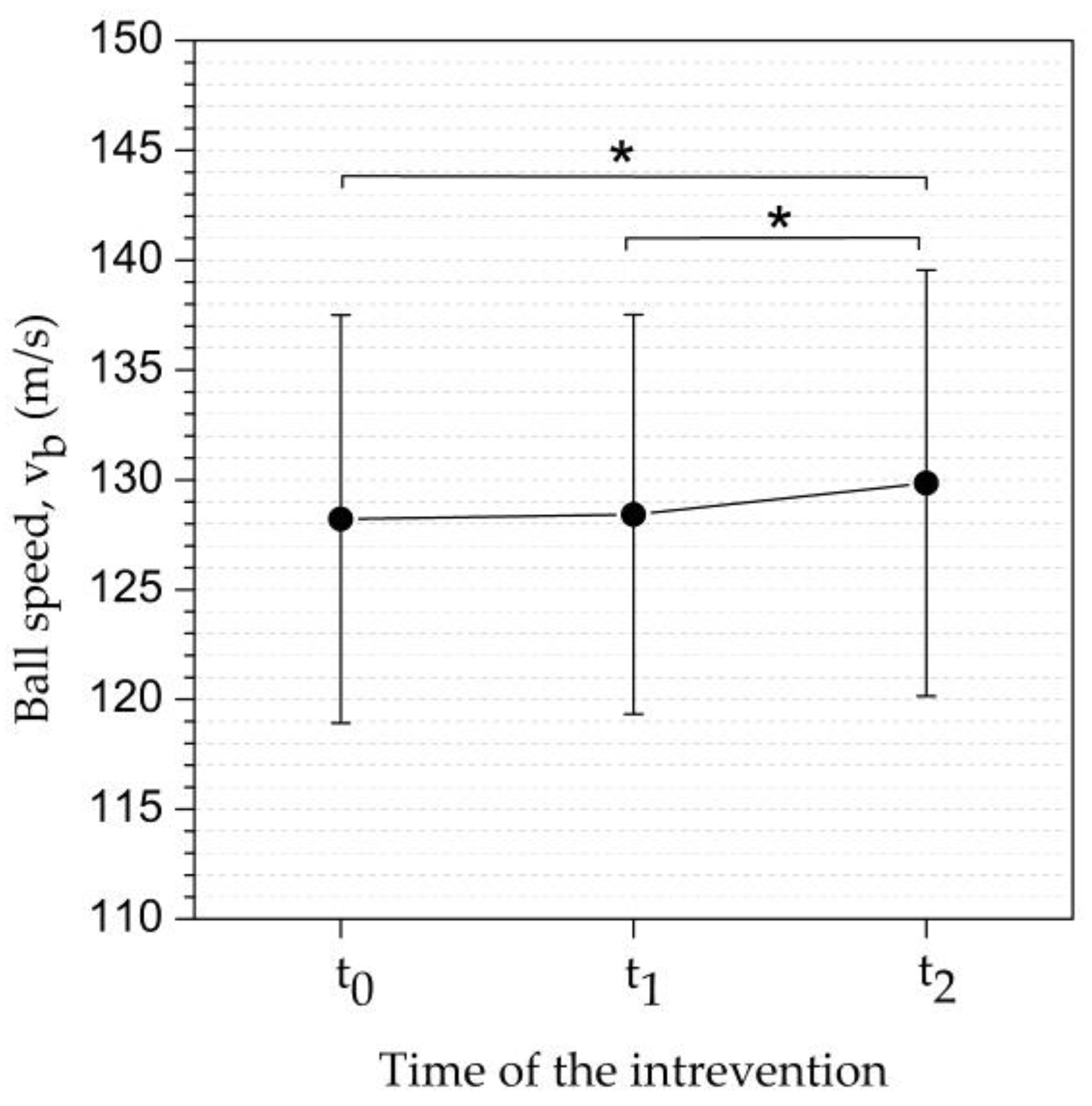

Figure 2); ball speed does not change significantly from t

0 to t

1, but increases from t

1 to t

2 (p = 0.02) (

Figure 3).

Contrary to the lead foot, the proprioceptive intervention had no significant effect on the peak vGR of the trail foot. The phase of the swing movement where the peak vGR of the lead foot occurs was also not affected by the treatment. This peak occurs shortly before phase 6 of the swing action (see subsection 2.4 Data recording and processing).

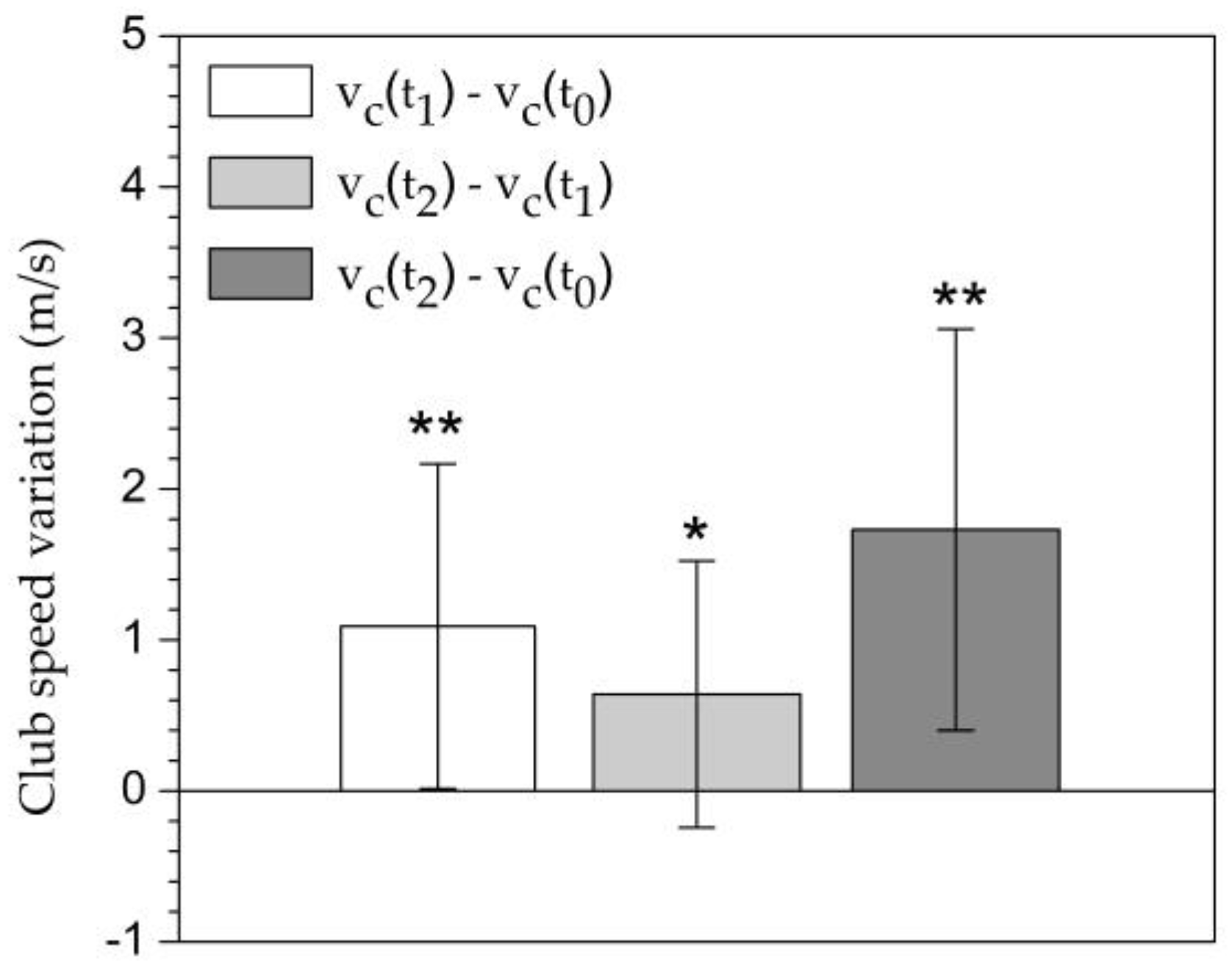

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6, along with

Table 2, display the outcomes of the one-sample t-test performed on the three sets of data obtained by calculating the individual differences between the performances at two different stages of the treatment for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. These tests provided additional information to the ANOVA analysis. Specifically, although ANOVA post-hoc tests indicate that the peak value of the total vGR is not significantly different between time t

0 and time t

1, the individual differences in this peak value from time t

1 to time t

0, when averaged across participants, are significantly greater than zero.

4. Discussion

In this study, we administered a specific proprioceptive exercise for the feet to experienced golf players and then had them modify their swing to incorporate the motor sequence learned during the conditioning phase. This approach led to improvements in key performance-related swing parameters, suggesting that the integration of foot-focused exercises into golf training could bridge the gap between technical mastery and athletic prowess, ultimately leading to enhanced performance.

The data regarding lead foot vGR, club speed, and ball speed demonstrate distinct temporal trends across the three successive swing sessions: before (t0), soon after (t1), and three minutes after (t2) the proprioceptive training intervention. The peak vGR of the lead foot increased from t0 to t1 but did not show further increments from t1 to t2; club speed increased from t0 to t1 and continued to rise, though to a lesser extent, from t1 to t2; ball speed did not change significantly from t0 to t1 but increased from t1 to t2. These changes can be interpreted in the light of the progressive acquisition and transfer to the swing of the motor sequences proposed during the proprioceptive conditioning intervention.

At time t

1, immediately after the intervention, participants are able to use their feet differently during the swing compared to time t

0, consistent with what was learned during the proprioceptive intervention, exerting a higher peak force on the ground with the lead foot. This increase translates to higher club speed, but not to ball speed. Ball speed is mainly (about 75%) determined by clubhead speed; however, centeredness of impact also has a considerable effect (about 7%) on ball speed [

39]. Thus, acutely, the new foot technique integrated in the swing, while resulting in higher club speed, likely induced less control and precision at the impact with the ball. This is understandable given the change in the motor pattern adopted, compared to the one consolidated over years of practice.

At time t2, three minutes after the intervention, participants continue to use their feet as they did at time t1 (at least regarding the peak vGR of the lead foot), but they transfer even more speed to the club (greater than it was at time t1) and finally manage to increase the ball speed after impact. In the second swing session after the conditioning intervention, and after three minutes of focusing on the sensations provided by the new technique, participants seem to be able to automate the new foot motor pattern and harmonize it within the swing gesture, effectively transferring the effect to the ball and regaining better shot precision. Ultimately, the benefits of the intervention and the new swing technique, with practice, progressively propagate from the feet to the club and finally to the ball.

The main limitation of the study relates to the selection of participants (

Table 1) and the limited duration of the proprioceptive conditioning intervention. The participants all demonstrated an excellent perception of the quality of movements performed in the various phases of the swing, and fully perceived the variations implemented in the swing and their effects. Most reported experiencing greater freedom and fluidity of movement, with fewer constraints and less resistance. However, novice and less experienced players may not yet have developed the same level of kinesthetic awareness or movement quality as more seasoned golfers, which could impact the effectiveness of the conditioning intervention. Therefore, the study should be extended to include golfers with varying levels of experience, age, and skill, along with other factors that could influence the outcomes of proprioceptive conditioning. Furthermore, interventions of different durations could be tested to assess their effectiveness across diverse groups of golfers. Such an approach would enhance the generalizability of the findings, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the proprioceptive intervention and helping to tailor interventions more effectively for diverse player profiles.

Another limitation arises from the limited number of parameters analyzed (peak vGR of the lead foot and the trail foot, club head speed, and ball speed) despite the large number of parameters recorded by the Trackman and the Smart2Move Dual Force Plate systems during the three swing sessions. The selection of ball and club head speed among the Trackman parameters was justified by the following considerations: (1) ball speed is a key indicator of both swing speed and the quality of impact, making it fundamental to overall performance, and (2) club head speed is largely the primary determinant of ball speed [

39,

40]. Additionally, these parameters are less susceptible to variations from external environmental factors. For instance, ball flight data can be heavily influenced by changes in wind speed and direction, which can differ significantly between sessions. Kwon and colleagues [

41] highlighted that among the parameters measured by force plate systems, the peak vGR of the lead and trail foot are key factors for optimal swing mechanics. In particular, the peak vGR of the lead foot has been shown to correlate strongly with maximum clubhead speed, with the vertical component providing the dominant contribution [

41].

During the measurement sessions, a 6-iron, which is an intermediate and frequently used club, was intentionally utilized. This should reasonably ensure good generalizability of the obtained results to other types of clubs. However, this aspect should also be confirmed with further investigations.

A final limitation concerns the force-plate data. The force plates used can only detect the vertical component of the ground reaction force and have indeed revealed an increase in the peak vGR of the lead foot with the modified swing technique. This technique involves intentional pressure and shearing forces exerted rhythmically by the right and left forefeet. Therefore, the use of triaxial platforms would likely have also detected an increase in the horizontal components of the ground reaction force and its axial moment on the plane of the platform. However, the monoaxial platforms used, due to their small size and portability, are particularly suitable for studying the typical golf actions, avoiding potential interference with the club during the swing or even visual distractions that could influence the player’s movement.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights that a training intervention featuring a targeted sequence of foot actions and the integration of this sequence into the swing movement can lead to increased peak vGR of lead foot, club speed, and ball speed, thereby improving swing mechanics and enhancing swing performance. Previous research has highlighted the importance of the rotation of the thoracic spine relative to the pelvis (X-factor) at the top of the backswing and during the start of the downswing [

42]. Wider X-factor has been correlated to higher clubhead speed and driving distance, likely due to greater utilization of the SSC, more efficient proximal to distal sequencing, and longer hand path [

10,

43,

44,

45]. The present study proposes another X scheme, that defined by the devised rhythmic and sequential ground actions exerted by the rearfoot and forefoot of the lead and trail foot. The new “ground-X-factor” has been designed to facilitate the bottom-up timing sequence of the swing action and enhance the traditional X-factor. Hopefully, this hypothesis should be verified by future studies.

Further studies are also necessary to assess the impact of the new swing technique on the mechanical loading acting across the kinetic chain involved in the swing movement. However, this requires advanced biomechanical modelling designed to calculate the shear and axial joint reaction forces acing on multi-joint kinetic chain [

46] during high velocity movements [

47]. This information is fundamental given the reported incidence of overuse injuries among golf players [

48,

49].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Bi., A.Be., A.C., N.B. and P.P.; methodology, A.Bi., A.Be., A.C., N.B. and P.P; software, A.Bi., A.C. and N.B.; validation, A.Be., A.C. and N.B.; formal analysis, A.Bi.; investigation, A.Be., A.C., N.B.; resources, A.Bi., A.C., N.B. and P.P.; data curation, A.Bi., A.Be., A.C. and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Bi.; writing—review and editing, A.Bi. and A.Be.; visualization, A.Bi.; supervision, A.Bi. and P.P.; project administration, A.Bi. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Perugia (protocol code: 226211; date of approval 13.09.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to “Golf della Montecchia” and “Golf Club Perugia” for providing their facilities for the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

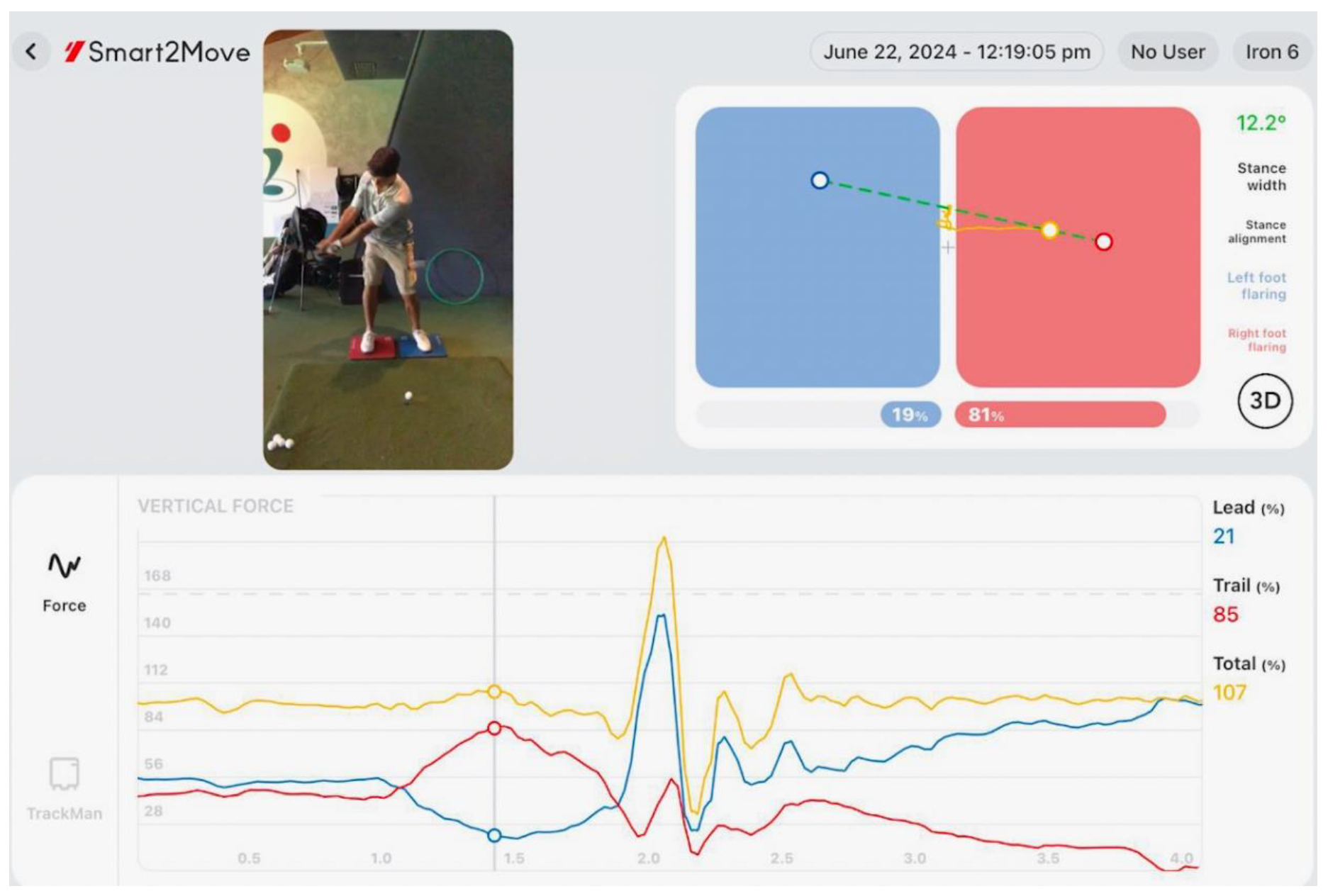

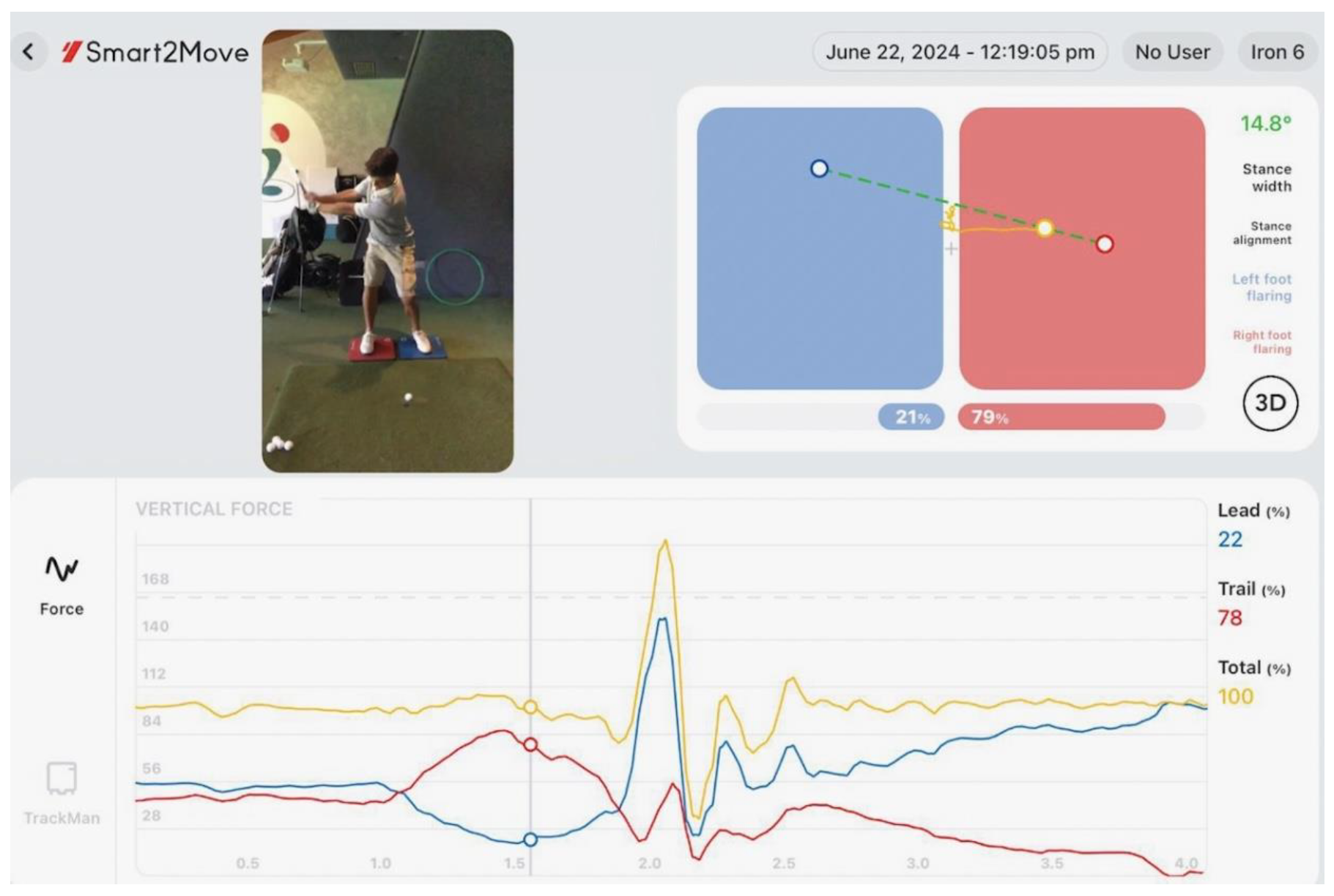

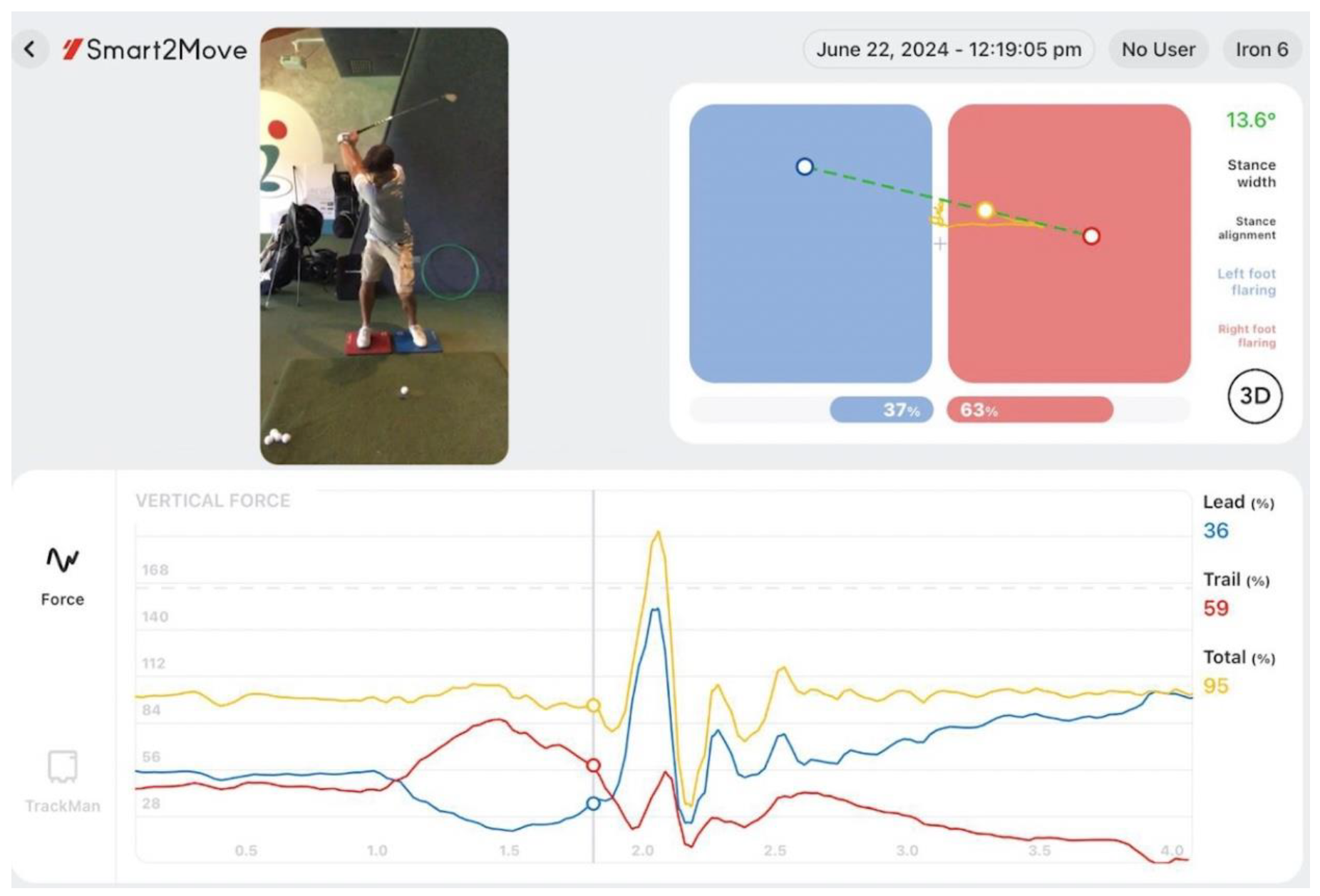

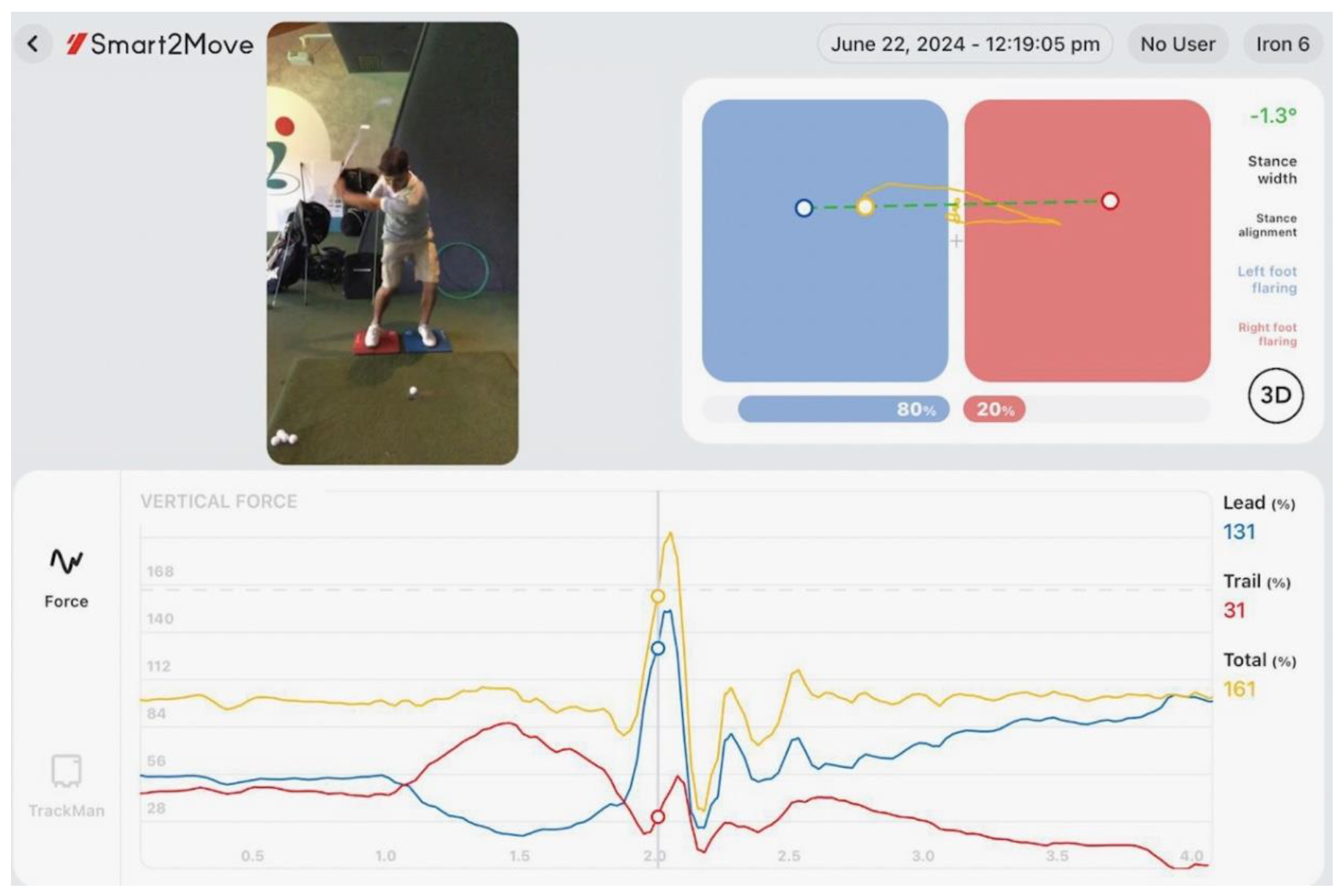

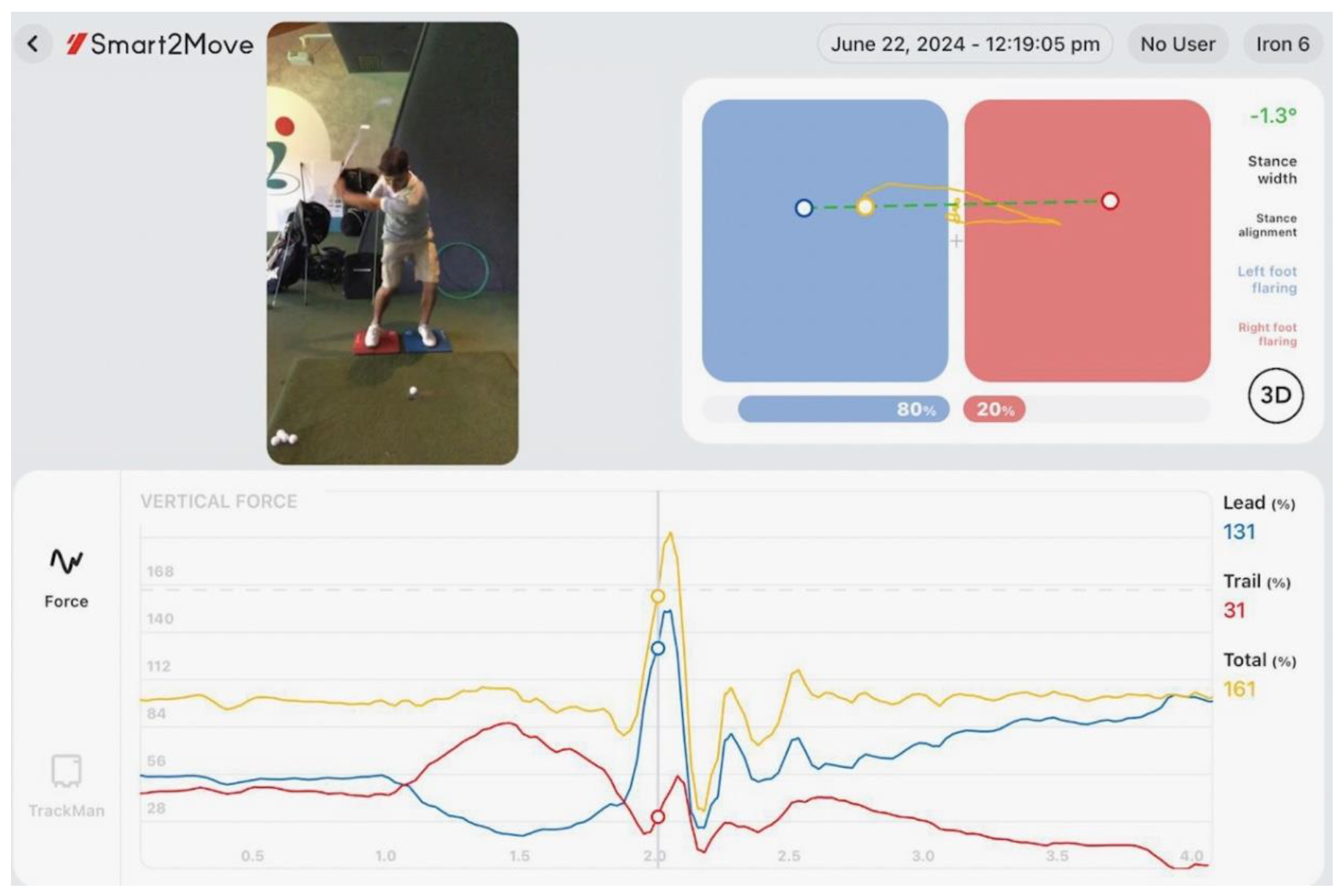

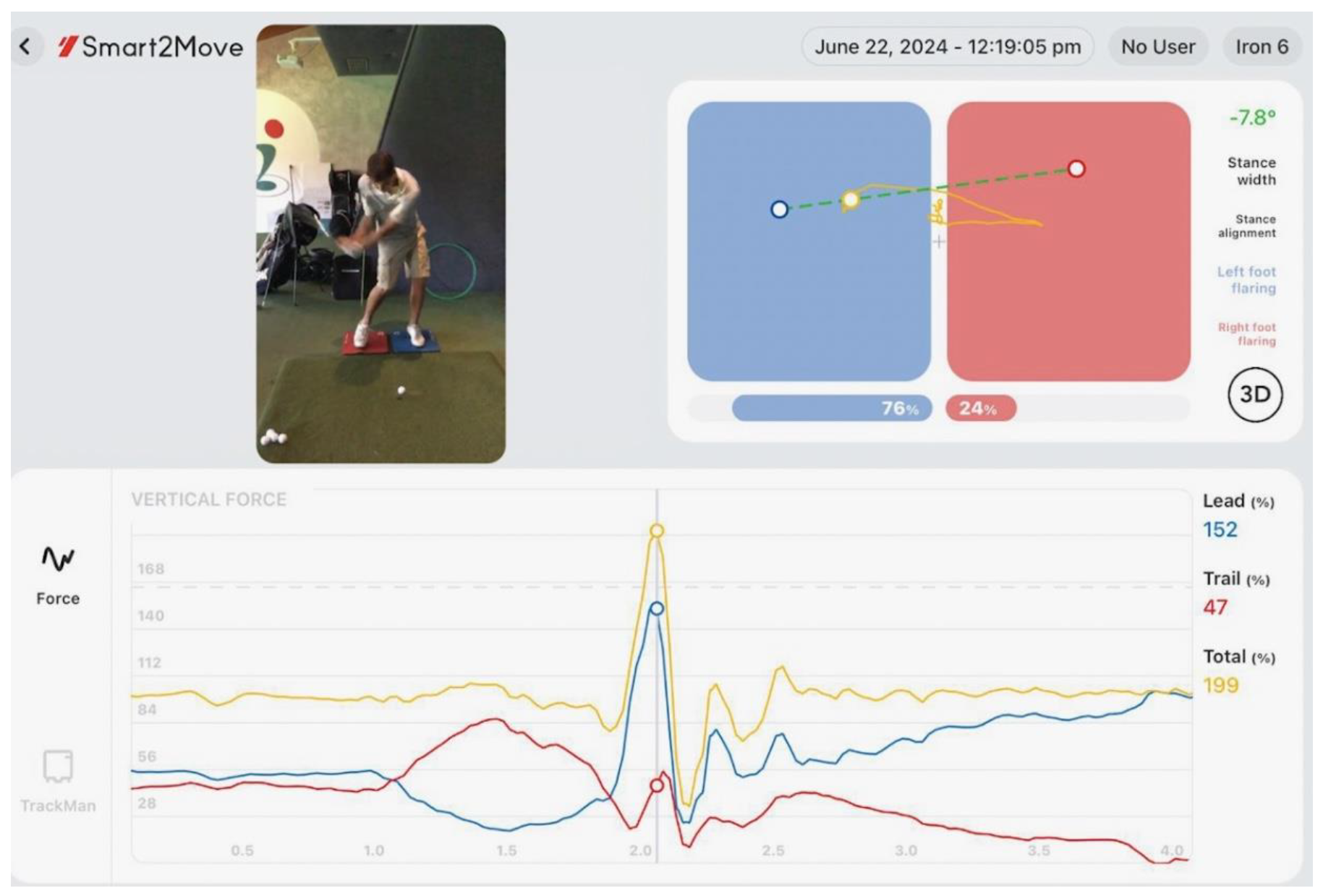

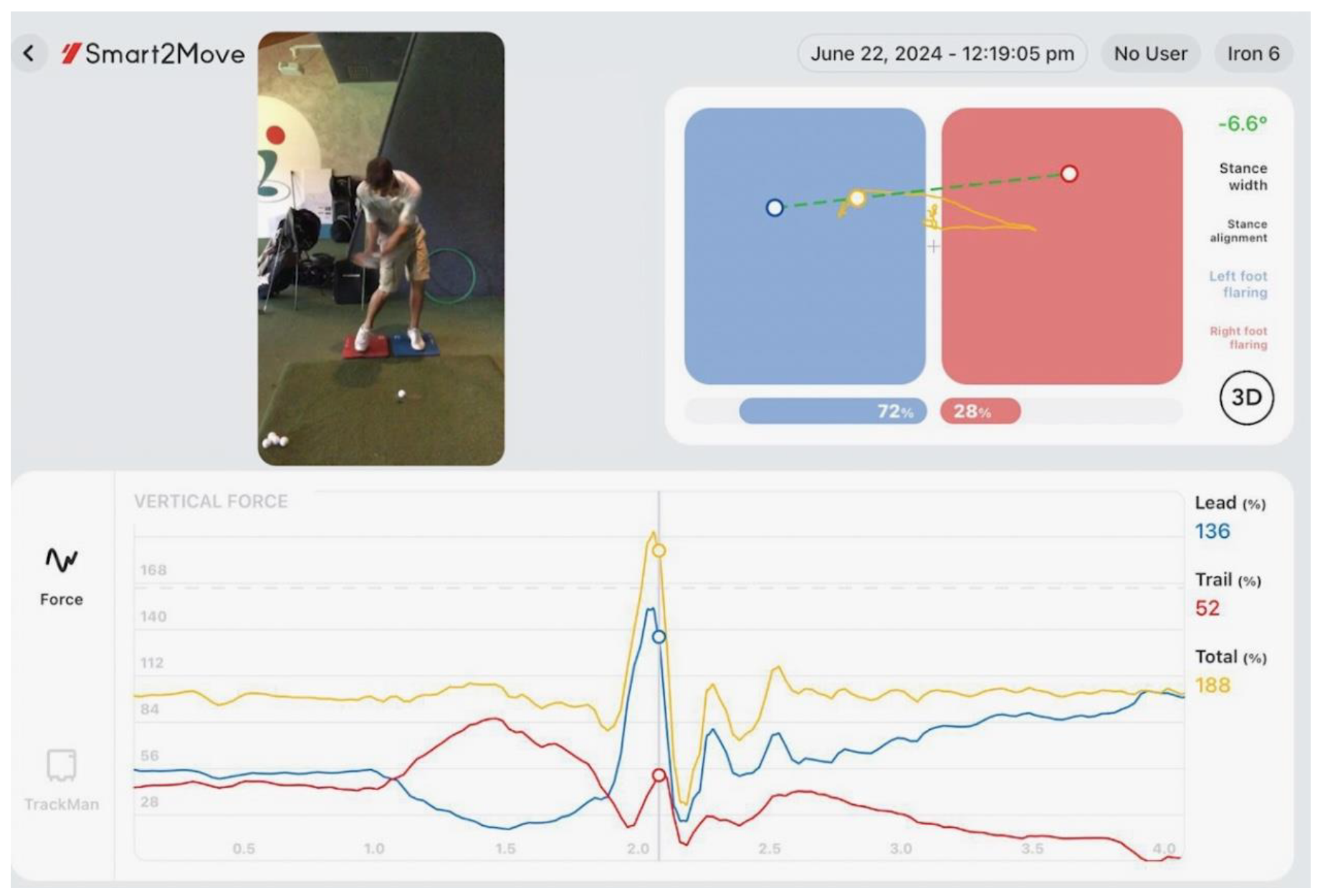

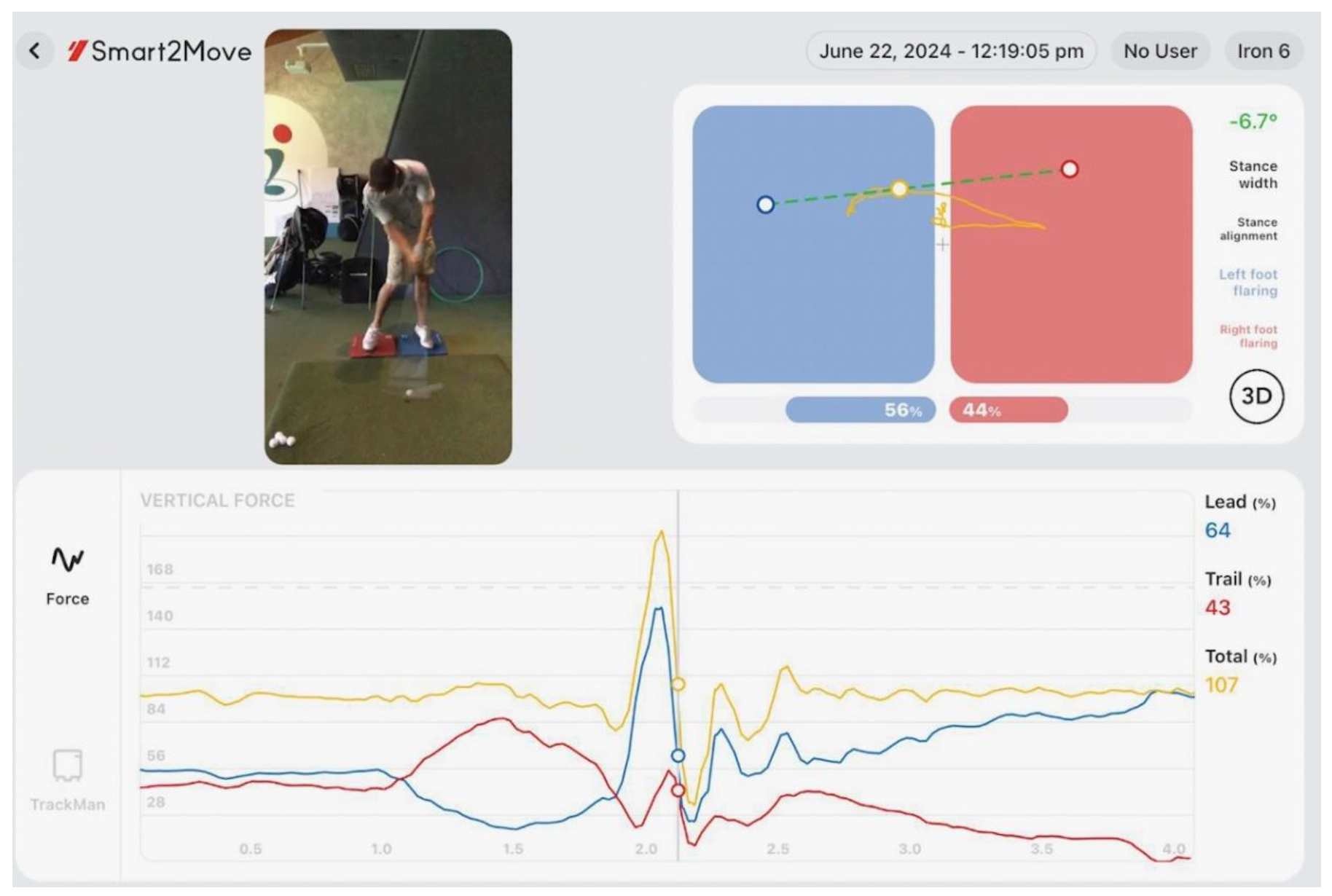

Appendix A

The seven reference positions of the Smart2Move Dual Force Plate system. P1: starting position, P2: club parallel to the ground in the backswing ; P3: left arm parallel to the ground in the backswing; P4: apex of backswing; P5: left arm parallel to the ground in the downswing, P6: club parallel to the ground in the downswing, P7: impact of the club with the ball), and position (between P5 and P6) where the peak value of the vertical ground reaction occurs. A sample of the Smart2Move output parameters is displayed in each position.

P1: starting position

P2: club parallel to the ground in the backswing

P3: left arm parallel to the ground in the backswing;

P4: apex of backswing

P5: left arm parallel to the ground in the downswing (descent, shot)

Phase of the swing where the vertical component of the ground reaction reaches its peak value

P6: club parallel to the ground in the downswing

P7: impact of the club with the ball.

References

- Farrally, M.R.; Cochran, A.J.; Crews, D.J.; Hurdzan, M.J.; Price, R.J.; Snow, J.T.; Thomas, P.R. Golf science research at the beginning of the twenty-first century. J Sports Sci. 2003, 9, 753–65. [CrossRef]

- The R&A Global Golf Participation Report 2023. Available online: https://www.randa.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Golf Participation in the U.S. – 2024. Available online: https://www.ngf.org/product/golf-participation-in-the-u-s-2024/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- European Golf Participation Report. 2023. European Golf Association. Available online: https://www.ega-golf.ch/content/raega-european-golf-participation-report (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Golf Industry Facts – Golfers. Available online: https://www.ngf.org/golf-industry-research/#golfers (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Golf Industry Facts - Golf Course Supply [online]. https://www.ngf.org/golf-industry-research/#golf-course-supply (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Evidence on physical education and sport in schools. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-on-physical-education-and-sport-in-schools (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- A Strategic Framework For Equality, Diversity & Inclusion. Available online: https://www.englandgolf.org/respect-in-golf. (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Smith, M.F. The role of physiology in the development of golf performance. Sports Med. 2010, 40(8), 635–655. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Ehlert, A.; Wells, J.; Brearley, S.; Brennan, A.; Coughlan, D. Strength and conditioning for golf athletes: biomechanics, common injuries and physical requirements. Prof. Strength Cond. 2022, 63, 7–18.

- Bliss, A.; Langdown, B. Integration of golf practise and strength and conditioning in golf: Insights from professional golf coaches. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18(5), 1605–1614. [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.E.; Langdown; B.L. Sports science for golf: a survey of high-skilled golfers’ “perceptions” and “practices”. J Sports Sci 2020, 38, 918–927.

- Shaw, J.; Gould, Z.I.; Oliver, J. L.; Lloyd; R. S. (2023). Perceptions and approaches of golf coaches towards strength and conditioning activities for youth golfers. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18(5), 1629-1638. [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.D.; Elmi, M.; Thomas, S. Physiological correlates of golf performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23(3), 741-750. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.; Sedano, S.; Cuadrado, G.; Redondo, J.C. Effects of an 18-Week Strength Training Program on Low-Handicap Golfers’ Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26(4), 1110–1121. [CrossRef]

- Meira E.P.; Brumitt, J. Minimizing injuries and enhancing performance in golf through training programs. Sports Health 2010; 2(4), 337-344. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Sánchez-Medina, L.; González-Badillo, J.J. Muscle strength and golf performance: a critical review. J Sports Sci Med. 2011, 10(1), 9-18.

- Ehlert, A. The effects of strength and conditioning interventions on golf performance: A systematic review. J Sports Sci. 2020, 38(23), 2720-2731. [CrossRef]

- Uthoff, A.; Sommerfield, L.M.; Pichardo, A.W. Effects of Resistance Training Methods on Golf Clubhead Speed and Hitting Distance: A Systematic Review. J Strength Cond Res. 2021, 35(9), 2651-2660. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, W.B.; Bower, R.G.; Watsford, M.L. Physical Determinants of Golf Swing Performance: A Review. J Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36(1), 289-297. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Gould, Z.I.; Oliver, J. L.; Lloyd, R.S. Physical determinants of golf swing performance in competitive youth golfers. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41(19), 1744–1752. [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, D.; Tilley, N.; Mackey, L.; Scoot., F; Brearley, S.; Bishop, C. Physical preparation for golf. Aspetar Sports Med. J. 2023, 116–122.

- Brennan, A.; Murray, A.; Mountjoy, M.; Hellstrom, J.; Coughlan, D.; Wells, J.; Brearley, S.; Ehlert, A.; Jarvis, P.; Turner, A.; Bishop, C. Associations Between Physical Characteristics and Golf Clubhead Speed: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1553–1577. [CrossRef]

- Tourillon, R.; Michel. A.; Fourchet, F.; Edouard, P.; Morin, J.B. Human foot muscle strength and its association with sprint acceleration, cutting and jumping performance, and kinetics in high-level athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42(9), 814-824. [CrossRef]

- McKeon PO, Hertel J, Bramble D, Davis I. The foot core system: a new paradigm for understanding intrinsic foot muscle function. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(5):290. [CrossRef]

- Jaffri, A.H.; Koldenhoven, R.; Saliba, S.; Hertel, J. Evidence for Intrinsic Foot Muscle Training in Improving Foot Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Athl. Train. 2023, 58(11-12), 941-951. [CrossRef]

- Słomka, K.J.; Michalska, J. Relationship between the strength of the ankle and toe muscles and functional stability in young, healthy adults. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1), 9125. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, C.; Shultz, S.P.; Colborne, G.R.; Fink, P.W. Foot Muscle Strengthening and Lower Limb Injury Prevention. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2021, 92(3), 380-387. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, P. Comprehensive Strength and Conditioning: Physical Preparation for Sports Performance; Informed in Sport: Vancouver, Canada, 2019.

- Malina RM. Early sport specialization: roots, effectiveness, risks. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2010, 9(6), 364-371.

- Gamble, P. Strength and Conditioning for Team Sports: Sport-Specific Physical Preparation for High Performance, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2013; p. 227.

- Tourillon, R.; Gojanovic, B.; Fourchet, F. How to Evaluate and Improve Foot Strength in Athletes: An Update. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2019, 1, 46. [CrossRef]

- Strüder, H.; Jonath, U.; Scholz, K. Track & Field: Training & Movement Science - Theory and Practice for All Disciplines. 2023. Meyer & Meyer Sport. Aachen, Germany.

- Fleisig, G.S.; Barrentine, S.W.; Escamilla, R.F; Andrews, J.R.. Biomechanics of Overhand Throwing with Implications for Injuries. Sports Med. 1996, 21, 421–437. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.K.; Jayabalan, P.; Kibler, W.B. The kinetic chain revisited: New concepts on throwing mechanics and injury. PM R. 2016, 8(3 Suppl, S69-S77. [CrossRef]

- Nagamoto, H.; Muraki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Kimura, R.; Ishikawa, H.; Shinagawa, K.; Matsuoka, S.; Yamada, Y.; Yaguchi, H.; Kurokawa, D.; Takahashi, H.; Kumai, T. Relationship between a history of disabled throwing shoulder/elbow and the ability fo perform the deep squat test among youth baseball players. J. Orthop. Rep. 2023, 2(4), 100197.

- Nagamoto, H.; Kimura, R.; Hata, E.; Kumai, T. Disabled throwing shoulder/elbow players have high rates of impaired foot function. Res. Sports Med. 2023, 31(5), 679–686. [CrossRef]

- Bourgain, M.; Rouch, P.; Rouillon, O.; Thoreux, P.; Sauret, C. Golf Swing Biomechanics: A Systematic Review and Methodological Recommendations for Kinematics. Sports (Basel). 2022, 10(6), 91. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.; Mills, P.; Alderson, J.; Elliott, B. The influence of club-head kinematics on early ball flight characteristics in the golf drive. Sports Biomech. 2013, 12(3), 247–258. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Wells, J.; Ehlert, A.; Turner, A.; Coughlan, D.; Sachs, N.; Murray, A. Trackman 4: Within and between-session reliability and inter-relationships of launch monitor metrics during indoor testing in high-level golfers. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41(23), 2138–2143. [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Como, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, D.K.; Kwon, Y H. Effects of the golfer-ground interaction on clubhead speed in skilled male golfers. Sports biomech. 2019, 18(2), 115–134. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; Selbie, W.S.; Wallace, E.S. The X-Factor: An evaluation of common methods used to analyse major inter-segment kinematics during the golf swing. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31(11), 1156–1163. [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Wulf, G.; Kim, S. Increased Carry Distance and X-Factor Stretch in Golf Through an External Focus of Attention. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2013, 1(1), 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, C. The most important “factor” in producing clubhead speed in golf. Human Movement Science 2017, 55, 138–144.

- Meister, D.W.; Ladd, A.L.; Butler, E.E.; Zhao, B.; Rogers, A.P.; Ray, C.J.; Rose, J. Rotational Biomechanics of the Elite Golf Swing: Benchmarks for Amateurs. J. Appl. Biomech. 2011, 27(3), 242–251. [CrossRef]

- Biscarini, A. Dynamics of Two-Link Musculoskeletal Chains during Fast Movements: Endpoint Force, Axial, and Shear Joint Reaction Forces. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 240. [CrossRef]

- Biscarini, A. Non-Slender n-Link Chain Driven by Single-Joint and Multi-Joint Muscle Actuators: Closed-Form Dynamic Equations and Joint Reaction Forces. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6860. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.L.; Epari, D.R.; Lorenzetti, S.; Sayers, M.; Boutellier, U.; Taylor, W.R. Risk Factors for Knee Injury in Golf: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47(12), 2621-2639. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.R.; Kay, R.S.; Robinson, P.G.; Murray, A.D.; Clement, N.D. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injury in professional and amateur golfers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58(11), 606-614. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Peak value of the vertical component of the ground reaction (N) for the lead foot, trail foot, and both feet, recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2).* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Peak value of the vertical component of the ground reaction (N) for the lead foot, trail foot, and both feet, recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2).* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Club speed () recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Club speed () recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

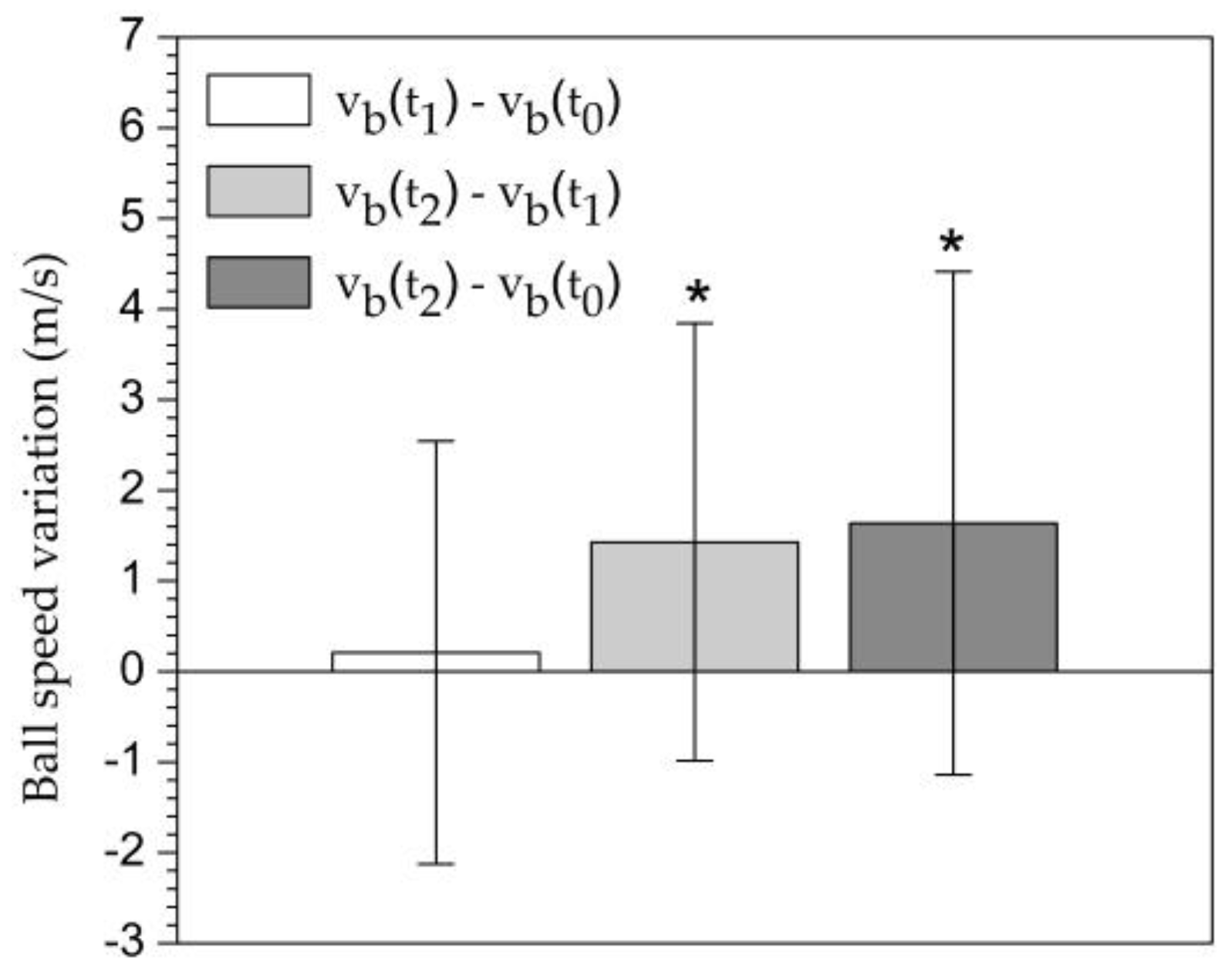

Figure 3.

Ball speed () recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Ball speed () recorded during three separate swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Differences in the peak value of the vertical component of the ground reaction (N) for the lead foot, trail foot, and both feet between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Differences in the peak value of the vertical component of the ground reaction (N) for the lead foot, trail foot, and both feet between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Differences in club speed between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Differences in club speed between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Differences in ball speed between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Differences in ball speed between each pair of three swing sessions: the first session before the foot proprioceptive intervention (time t0), the second soon after the intervention (time t1), and the third three minutes after the end of the second session (time t2). The differences are calculated by taking the individual differences between the performances in two sessions for each athlete and then averaging these differences across participants. Mean ≠ 0: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics relevant to the study.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics relevant to the study.

| Participants characteristics |

|---|

| Number of participants |

25 |

| Age (mean ± SD) |

29 ± 10 years |

| Height (mean ± SD) |

181 ± 8 cm |

| Weight (mean ± SD) |

78 ± 9 kg |

| Years of golf experience (mean ± SD) |

20 ± 10 years |

| Weekly hours of golf practice (mean ± SD) |

16 ± 12 hours |

| Handicap index (mean ± SD) |

0.4 ± 2.7 |

| Percentage of participants with right-side dominance |

100% |

| Percentage of participants using glasses |

40% |

Table 2.

One sample t-test outcomes (null hypothesis mean=0, alternative hypothesis mean≠0) for the individual differences between the performances at two different stages of the treatment for each athlete averaged over the participants (BW=body weight).

Table 2.

One sample t-test outcomes (null hypothesis mean=0, alternative hypothesis mean≠0) for the individual differences between the performances at two different stages of the treatment for each athlete averaged over the participants (BW=body weight).

| |

|

p |

power |

confidence interval |

| |

|

lower limit |

upper limit |

| Individual performance difference from t0 to t1 |

|

|

|

|

| Lead foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

< 0.001 |

0.99 |

3.94 |

10.27 |

| Total foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

0.03 |

0.60 |

0.49 |

9.27 |

| Club speed (m/s) |

< 0.001 |

> 0.99 |

0.65 |

1.53 |

| Ball speed (m/s) |

0.66 |

0.07 |

-0.76 |

1.17 |

| Individual performance difference from t1 to t2 |

|

|

|

|

| Lead foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

0.65 |

0.07 |

-3.52 |

2.24 |

| Total foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

0.76 |

0.06 |

-3.22 |

4.34 |

| Club speed (m/s) |

0.001 |

0.93 |

0.28 |

1.01 |

| Ball speed (m/s) |

0.007 |

0.81 |

0.43 |

2.42 |

| Individual performance difference from t0 to t2 |

|

|

|

|

| Lead foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

< 0.001 |

0.98 |

3.38 |

10.14 |

| Total foot vertical ground reaction (% BW) |

0.02 |

0.65 |

0.86 |

10.02 |

| Club speed (m/s) |

< 0.001 |

> 0.99 |

1.18 |

2.28 |

| Ball speed (m/s) |

0.007 |

0.81 |

0.49 |

2.78 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).