1. Introduction

In golf, the key to swing technique is to produce faster club head speeds [

1,

2]. Faster club head speed is a combination of limb speed and power, and the limbs tend to move from proximal to distal links in a sequence of acceleration and braking, resulting in great speed at the end of the link, and the use of the body's rotational mechanics to transfer this speed to the club to maximize power [

3,

4]. Studies have found the importance of relative or absolute pelvic and trunk rotation, translation, and the generation of such free moments during the swing when the player hits the ball [

5,

6]. The X-factor (shoulder-hip separation angle) is one of the commonly investigated indicators of athletic performance in the game of golf [

7], and rotational biomechanics is a key determinant of distance from the ball [

5,

6,

8].The ability of the more skilled golfer to obtain a large X-factor at the top of the backswing increases club head speed and ball speed[

9,

10]; the baseline curves for the angle of rotation and speed of rotation for the pelvis, upper torso, and X-factor are established throughout the golf swing and have also been demonstrated in professional players[

4]. Research has shown that that pelvic rotation occurs prior to torso rotation, increasing the X-factor early in the downswing, and that torso-pelvic separation contributes to both upper body rotation speed and torso-pelvic separation speed, which ultimately contributes to increased ball speed[

6,

9].Other scholars, also through the body joint rotation characteristics and stability, ground reaction force, center of gravity transfer, physical factors and other aspects also carried out extensive research, found that many aspects play an important role in improving club head speed and hitting distance[

4,

11,

12,

13].

Mastery of long iron technology can allow players to play in the competition to play a more excellent sports performance and strike a longer hitting distance, the current research on the analysis of golfers' swing technology focuses on the driver[

14,

15,

16]. Although there are studies on the technical analysis of irons, most of the tested clubs are medium - long irons, and the research objects are mostly amateur players[

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], and there are very few studies on the analysis of professional players and long irons[

22,

23]. Thus, this study applied the K-vest wireless biofeedback system to analyze the full swing technique of male professional players to provide a theoretical basis for the development of scientific training.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Eight right-handed professional golfers (all members of China Golf Collective Team,age = 19 ± 3 years; height= 177 ± 4 cm; mass = 74 ± 3 kg) gave their informed consent to take part in the study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University Ethical Advisory Committee which was in accordance with ethical standards and principles of the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

2.2. Data Collection

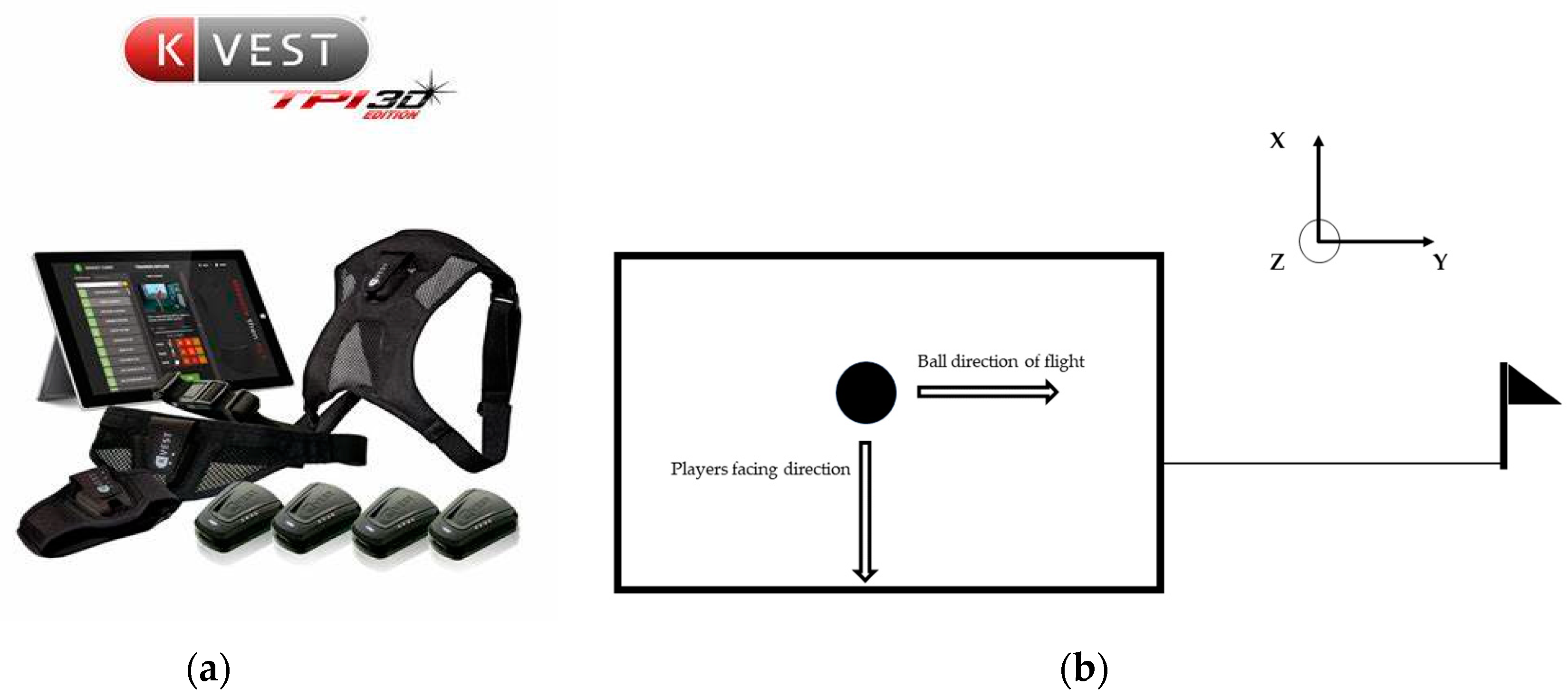

The K-vest wireless biofeedback system (

Figure 1) was applied to 8 players at the National Golf Training Center in Nanshan, Shandong Province, China. The test clubs were 5-irons with steel shafts, and the players were allowed to warm up and practice hitting the ball for 20 minutes prior to the start of the test. At the beginning of the test, the sensors were placed on the top of the player's sacrum, back and wrists, and ensure that the safety wristbands were in a locked state. After the equipment was turned on and calibrated, the player was required to stand in a neutral aiming position, parallel to the predetermined target line. At the same time to ensure that the surrounding signal stability, to exclude undesirable radio interference, after successful debugging each player to complete 10 full swing batting action, and collect relevant data.

2.3. Defined

Axis of Motion: The athlete's anterior-posterior direction is set as the X-axis, the direction of a vertical line perpendicular to the X-axis toward the flagpole is set as the Y-axis, and the direction perpendicular to the plane formed by the X and Y is set as the Z-axis (

Figure 1).

Pelvic rotation angle: the angle formed by the transverse axis of the pelvis and the Y-axis. If the transverse axis of the pelvis is parallel to the Y-axis, it is considered that the pelvis is in a neutral position (0°), and the pelvis rotates away from the direction of the flagpole (closed position) in a negative direction, and in the opposite direction (open position) in a positive direction.

Angle of rotation of the trunk: the angle formed by the transverse shoulder axis and the Y-axis. If the transverse shoulder axis is parallel to the Y-axis, the trunk is considered to be in a neutral position (0°), the angle of rotation of the transverse shoulder axis away from the flagpole (closed position) is negative, and the angle of rotation in the opposite direction (open position) is positive.

2.4. Characteristic temporal phases and phasing

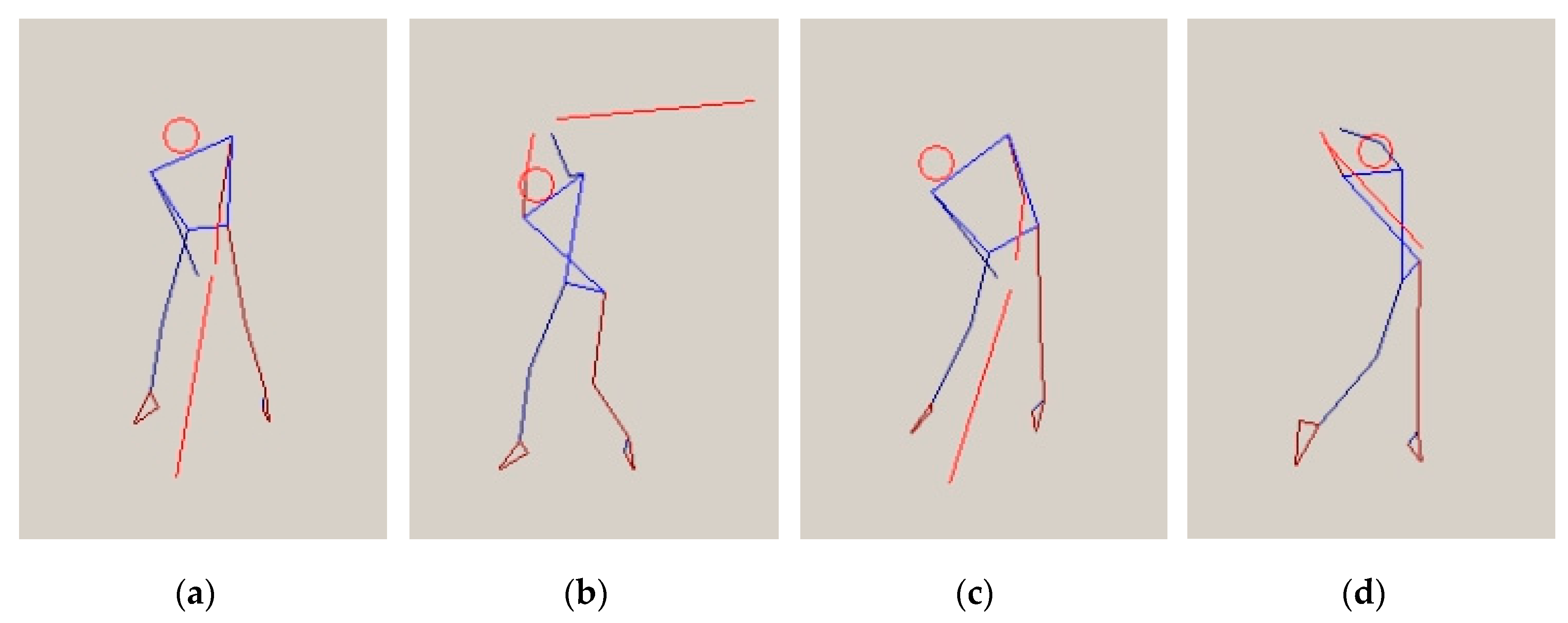

The full swing technique was divided into 4 characteristic temporal phases and 3 stages according to the research needs. Aiming preparation (

Figure 2, a): the moment of changing from the preparation position to the backward lead; top of the backswing (

Figure 2, b): the moment when the direction of the club head changes from moving backward to moving forward from the backswing to the highest point; the point of impact (

Figure 2, c): the moment when the club head makes contact with the ball; and the ending point (

Figure 2, d): the moment when the speed of the club head at the end of the stroke becomes 0 behind the body. Backswing phase: from the aiming preparation to the top of the backswing (

Figure 2, a-b); Downswing phase: from the top of the backswing to the point of impact (

Figure 2, b-c); Follow-through phase: from the point of impact to the finish point (

Figure 2, c-d).

3. Results

3.1. Full Swing Sequence of Motion Characterization

3.1.1. Starting sequence

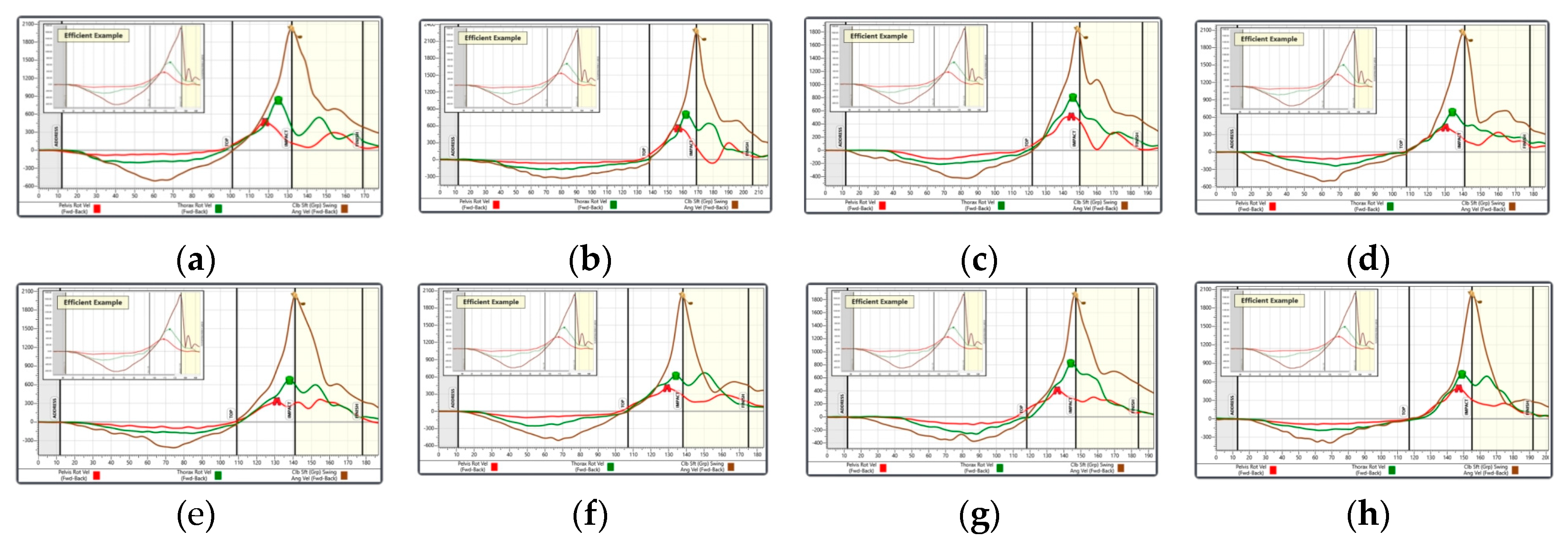

Full-swing technical movements in the form of human movement manifested in the torso twist and upper limb whip, the backswing phase rely on the torso of the transverse axis of the shoulders and the transverse axis of the hips around the spine of the spinal column of the rotation of the force, the upper limbs to control the club to strike the target of the club first in the opposite direction of the swing club, accompanied by the amplitude of the backswing increased, the torso to complete the reversal of the torso. In the swing sequence chart measured by the K-vest Wireless Biofeedback System (

Figure 3). The ideal sequence of movement in the backswing phase is club-arms-torso-pelvis, and the correct start sequence is conducive to the formation of the correct downswing sequence, resulting in a more efficient swing. The wrong way to start the club will easily lead to delayed extension of the hips and trunk at the beginning of the backswing, the study found that two of the players had their hips start more behind the trunk and the club and the upper limbs and trunk were more involved in the backswing, which affects the club head speed; three players had their hips start earlier than the club or the trunk, which will lead to the failure of the backswing to form the force, and the formation of the club's "stuck in the inner end" of the swing.

3.1.2. Transition sequence

Transition refers to the transition from the top of the backswing to the downswing, the backswing completes the force storage, the torso and upper limbs control the club in the downswing to twist the club towards the target direction, completing the whipping action from the proximal to the distal limb sequential force generation process. The key to effective energy transfer in the downswing lies in the transition sequence, each body link should have a proper sequence of acceleration and deceleration, the ideal transition sequence is pelvis - thorax - club, in the early stage of the downswing the pelvis rotates faster than the thoracic vertebrae, the proximal link of the body moves more than the distal link, and the angle of rotation of the spine is constantly increased to stretch the muscles into a centrifugal contraction state that can provide more power for the ball. The second transition sequence is a downswing in which the pelvis and thoracic spine rotate at the same rate, the muscles are in isometric contraction, and then the club rotates again. This provides power for the downswing but makes it difficult to generate maximum power. The third transition sequence is that the club rotates first in the downswing, the thoracic spine rotates faster than the pelvis, then the pelvis rotates, the distal link of the body exceeds the proximal link, and the muscles rapidly enter centripetal contraction, which fails to produce a whip, resulting in a lack of power in the stroke. The swing is characterized by an early opening of the wrist flexion angle, a larger clubface angle at the moment of impact, and a reduction in the distance of the stroke which in turn leads to inefficiency. As seen in

Figure 3, the transition sequence of most players was the ideal transition sequence, and only 1 player had the wrong sequence which was characterized by club rotation first, then pelvic rotation, and finally thoracic spine rotation.

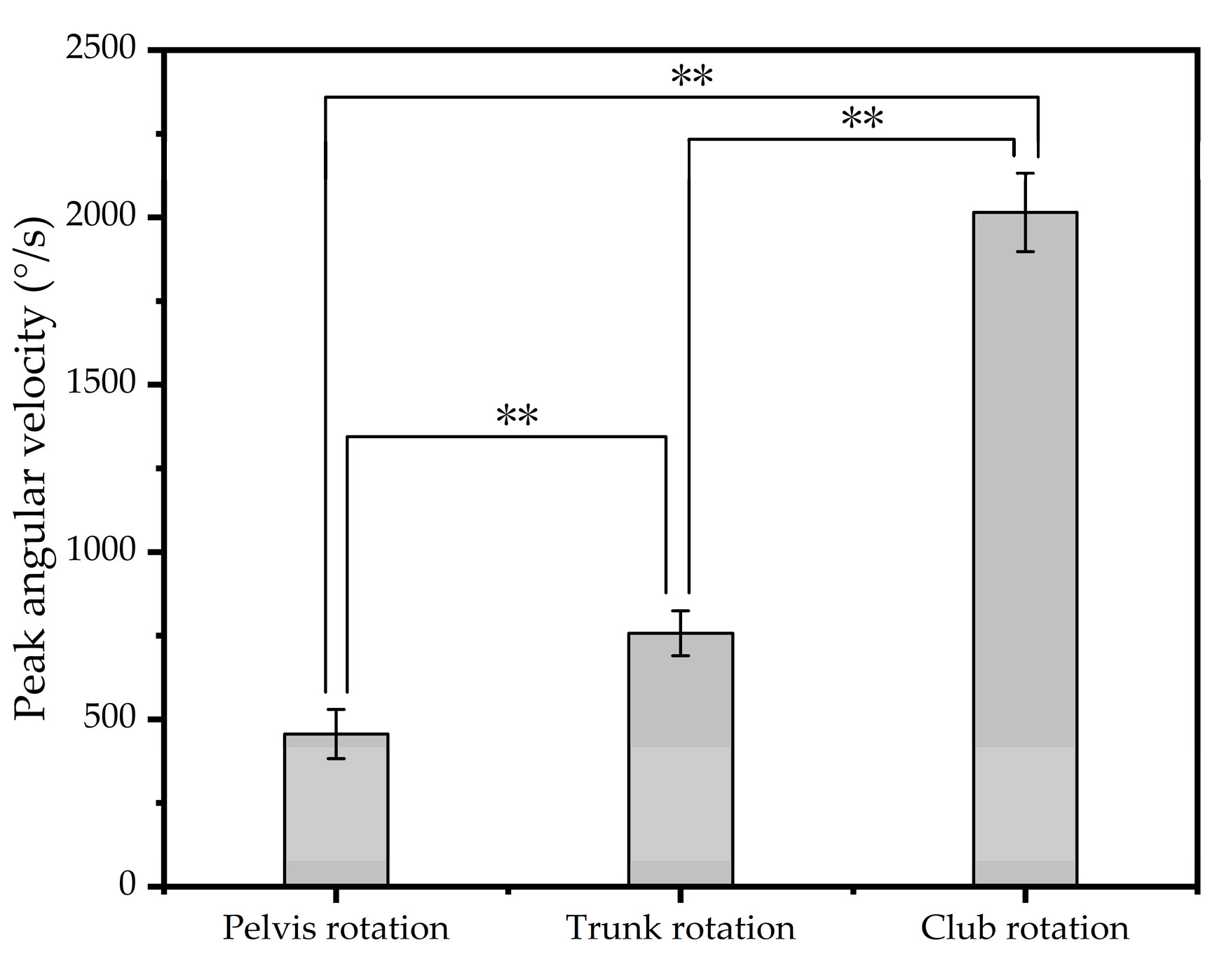

3.1.3. Peak rotational angular velocity and time characteristics

The peak pelvic, trunk, and club angular velocities of the participants were 456.07 ± 73.56º/s; 757.20 ± 66.93º/s; and 2014.94 ± 116.99º/s, with coefficients of variation of 16.1%, 8.8%, and 5.8%, respectively, and the mean ranges of the PGA's top players were 425 ~ 510º/s; 650 ~ 720º/s; 1600 ~1850º/s (

Table 1). The range of peak pelvic angular velocity is consistent with that of the top players, while peak upper trunk angular velocity and peak club angular velocity are higher than them. The peak angular velocities of the pelvis, torso and club were significantly different (p<0.05), with the peak angular velocities of the pelvis < peak angular velocities of the torso < peak angular velocities of the club. With the assistance of K-vest wireless biofeedback system, the starting sequence of the sensor curves at different positions can be observed to know the players' starting sequence, and the analysis of the peak data of the curves corresponding to each position can be well derived from the changes of the peak angular velocity of the pelvis, torso, and club in the process of swinging the golf club (

Figure 4).It has been found that the shoulders and wrists are more involved in the moment of hitting the ball, and do not reflect well the whipping effect of the limbs as a means of accelerating and braking. Once this angular momentum occurs during the swing, it causes resistance due to the inertia of the player's body, preventing the body from moving forward and sideways. Players in the early stage of the downswing hips take the lead in the rapid movement of the shoulders and hands of the small muscle groups contraction force is insufficient, affecting the transfer of power, forcing the right shoulder toward the ball position forward to move the club away from the player's body, increasing the angular velocity of the club peaks, cannot be the body rotation of energy generated by a good transfer of energy to the club head, the club head speed is reduced to produce a right curved ball, through the strengthening of abdominal obliquity, wrist extensors related to the training can be effectively Improve power transmission.

3.2. Preparatory posture characteristics

Reasonable preparation posture is the foundation of the full golf swing, as can be seen through

Table 2, do a good job of hitting the ball ready posture in hitting the ball ready posture in the anterior pelvic tilt angle of 2 players angle average value is greater than the PGA players range of 12º ~ 27º. In the comparison of anterior trunk tilt angle, there are 4 players with anterior trunk tilt angle greater than the range of PGA players. Three players in the trunk lateral bending angle comparison had angles less than the PGA player range of 0.1º ~ 1.7º. Pelvic rotation angle comparisons had 2 players in the open position and 1 player in the closed position during the stroke preparation position. The torso rotation angle had 1 player with an angle mean greater than the PGA player range and 2 players below the PGA player range. Analysis of the data indicates that the body posture during the batting preparation phase has yet to be standardized. The anterior pelvic tilt angle and anterior trunk tilt angle in the preparation stance are an important part of providing good support for body rotation in the full swing, which in turn produces maximum club head speed. There are 4 players whose anterior trunk tilt angle exceeds the range of values for PGA players. Excessive anterior tilt angle is not conducive to trunk rotation and tends to reduce club head speed affecting the distance of the stroke, indicating that the hip flexion and extension is not enough and there are compensatory actions of the body during the stance, and the training clock should be strengthened to address the related problems. Pelvic lateral bending angle is smaller than the trunk lateral bending angle, this is due to the usual golfers in the grip, the left hand on the top, the right hand in the bottom. The left shoulder is slightly higher than the right shoulder after the shot has been prepared. The corresponding left hip is higher than the right hip. Another important reason is that as the body rotates during the downswing, the amplitude of the torso side bend angle increases further, which allows the club face to be at a reasonable hitting angle at impact and maintains the ideal takeoff angle.

3.3. Backswing Top Characteristics

From the biomechanical level analysis of the golf full swing in the human body in the form of the basic movement of the torso twist, including the thoracic spine joints, lumbar spine joints and ankle joints, high-level athletes in order to increase the distance of the ball as much as possible to increase the separation of the hip-shoulder [

24], so as to make most of the joints of the body to achieve the maximum amplitude of rotation under the premise of maintaining a relatively stable for the downswing phase of the accumulation of more energy to produce greater torque. The anterior pelvic tilt angle at the top of the backswing was outside the PGA player range for 1 player, the lateral pelvic curvature angle was too large and outside the average PGA range for 5 players, 2 players had less than average anterior trunk tilt and lost their body position at the top of the swing, becoming straighter. the lateral trunk curvature angle tended to be shifted in the opposite direction of the shot for 1 player, and the pelvic rotation angle was turned by a greater angle in a closed direction for 3 players, averaging outside the PGA player range, and the torso rotation angle had 4 players who averaged beyond the PGA player range in the closed direction. As can be seen from the results, excessive lateral pelvic bending angles, over-rotation, and hyperextension of the torso were prevalent at the apex of the backswing. The vertex position is the transition between the backswing and the downswing, and to achieve a continuous and efficient swing, the correct vertex position is critical, which will ensure that the swing plane is in the ideal position. Core stability training should be added to daily physical training to avoid excessive pelvic curvature, over-rotation, and hyperextension of the torso at the top of the backswing.

Table 3.

List of Technical Parameters of Players at the Top of the Swing (º/s).

Table 3.

List of Technical Parameters of Players at the Top of the Swing (º/s).

| |

Anterior pelvic tilt |

Lateral pelvic curvature |

Anterior trunk tilt |

Lateral trunk curvature |

Hip axis angle |

Shoulder axis angle |

| NA

|

16.75±2.27 |

-17.08±0.87 |

-0.50±1.23 |

-40.83±0.61 |

-45.67±1.89 |

-87.67±2.03 |

| NB

|

12.00±0.73 |

-16.08±0.71 |

6.50±2.14 |

-43.33±0.43 |

-53.83±0.86 |

-95.67±1.49 |

| NC

|

17.33±0.93 |

-17.20±0.32 |

6.47±1.38 |

-39.60±0.63 |

-52.27±1.71 |

-92.53±1.72 |

| ND

|

26.25±1.81 |

-16.00±0.65 |

3.00±2.62 |

-43.50±0.16 |

-52.50±3.95 |

-103.25±5.47 |

| NE

|

11.08±0.64 |

-16.67±0.54 |

-3.41±1.54 |

-41.50±0.81 |

-53.17±0.87 |

-94.42±1.67 |

| NF

|

20.18±0.78 |

-12.09±0.71 |

7.09±1.12 |

-45.09±0.94 |

-36.27±0.81 |

-79.18±0.86 |

| NG

|

15.55±2.45 |

-12.64±0.65 |

5.00±0.36 |

-38.27±0.86 |

-42.18±3.87 |

-88.91±1.98 |

| NH

|

12.40±0.46 |

-11.90±0.91 |

5.40±0.62 |

-46.30±0.21 |

-42.10±0.23 |

-87.20±0.37 |

| Total |

16.44±4.71 |

-14.96±2.15 |

3.69±8.39 |

-42.30±4.17 |

-47.17±8.14 |

-91.10±7.48 |

| PGA ranges |

11~23 |

-13~-4 |

2~15 |

-45~-39 |

-46~-30 |

-86~-74 |

3.4. Hitting Moment Characteristics

At the moment of hitting, 2 players had excessive anterior pelvic tilt beyond the PGA players' range of 0º~ 9.0º. 4 players were less than the PGA players' range of 10º ~ 17º in the comparison of lateral pelvic curvature angle. The problem was more prominent in the comparison of anterior trunk inclination angle, 4 players were in the normal range of values, and the rest of the players exceeded the range of the PGA players, indicating that most of the players lost their body postures at the moment of hitting the ball, and tilted their torsos forward more, which tended to lead to unsound hitting.4 players were less than the range of the PGA players in the comparison of the lateral angle of trunk curvature, and 1 player was above the range of the PGA players.4 players were less than the range of the PGA players in the comparison of the pelvis rotation angle, and 1 player was below the range of the PGA players. PGA player range and 1 player was above the PGA player range. 5 players had insufficient torso rotation and were below the PGA player range overall. The analysis concluded that there were two major issues with a greater anterior trunk tilt angle and insufficient trunk rotation at the point of impact in the full swing. Pelvic rotation angle and trunk rotation angle have a direct effect on the club head speed when hitting the ball, the club head speed is an important condition of the hitting distance, in the golf full swing hitting effect of the ball, the longer hitting distance can reduce the distance between the ball and the target hole, for the player's next shot when the club selection, tactical development to provide more possibilities. Pelvic flexion and extension exercises should be added to the training program to ensure that the torso is able to reduce the forward tilt angle and increase the rotation angle during the downswing.

Table 4.

List of Technical Parameters of Players at the Moment of Hitting the Ball(º/s).

Table 4.

List of Technical Parameters of Players at the Moment of Hitting the Ball(º/s).

| |

Anterior pelvic tilt |

Lateral pelvic curvature |

Anterior trunk tilt |

Lateral trunk curvature |

Hip axis angle |

Shoulder axis angle |

| NA

|

7.00±0.12 |

16.17±0.76 |

35.92±0.29 |

28.17±0.89 |

43.00±0.24 |

23.33±1.56 |

| NB

|

6.83±2.57 |

8.83±0.56 |

48.08±3.13 |

21.58±6.42 |

25.00±3.28 |

15.42±9.21 |

| NC

|

1.33±1.09 |

11.73±0.56 |

49.53±1.29 |

24.87±2.36 |

14.53±0.98 |

14.07±1.86 |

| ND

|

12.75±0.97 |

12.00±2.73 |

48.75±4.22 |

13.25±6.62 |

25.50±4.46 |

4.75±2.15 |

| NE

|

6.75±0.37 |

6.17±0.51 |

52.50±2.28 |

15.58±3.15 |

24.67±2.49 |

16.92±3.61 |

| NF

|

11.09±0.79 |

11.45±0.79 |

41.00±0.84 |

35.91±1.65 |

46.00±1.75 |

36.00±1.26 |

| NG

|

6.00±2.65 |

8.00±0.48 |

39.55±1.75 |

31.82±2.78 |

64.27±2.49 |

33.46±3.45 |

| NH

|

4.60±1.56 |

16.60±2.14 |

40.20±0.67 |

23.80±3.18 |

46.00±2.18 |

29.00±1.20 |

| Total |

7.04±5.20 |

11.37±3.65 |

44.44±6.25 |

24.37±2.38 |

36.12±4.73 |

21.62±5.67 |

| PGA ranges |

0~9 |

10~17 |

29~42 |

24~33 |

35~50 |

26~34 |

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to understand the technical characteristics of the general professional players at the moment of swing and to compare them with the parameter ranges of the top professional players. Analyzing the common technical characteristics of professional players at critical moments and exploring the causes of movements that deviate significantly from the parameter range are the objectives of this study. By observing the start-up sequence of the sensor curves at different positions of the calibration, the player's launch sequence can be known, and the peak data analysis of the curves corresponding to each position can be derived from the peak changes of the angular velocity of the pelvis, torso, and club during the swing process (

Figure 3). For the right-handed player, at the beginning of the downswing, the large muscle groups at the proximal end of the body contract, the center of gravity of the body is shifted to the front side (left side), and the front knee (left knee) is placed directly above the front foot (left foot), which encourages the lower extremities to be the easiest to launch [

25,

26]. When placing the knee directly above the foot, the quadriceps are able to work to straighten the knee, and the gluteus maximus and tendon muscles are able to create tension in the hips and pelvis through contraction. With this tension movement working together, the front foot applies a force to the ground, which then applies a reaction force to the player. This reaction force is easily transmitted through the legs to the pelvis and torso, which in turn creates a better transfer of power and contributes to stroke efficiency.

Scholars believe that the hip and shoulder axes should be aligned with the target line in the ready stance [

27]. The shoulder axis pointing in the ready stance of the participants in this study was moderately shifted from the target line, which was mainly related to the clubface pointing, shoulder axis pointing, and hip pointing during the aiming of the ball. The participants' pelvic flexion and extension ability and lumbar spine flexibility during the downswing were insufficient, resulting in the presence of a compensatory movement of the trunk to increase the angle of forward tilt [

28,

29]. This affected their rotational amplitude, with trunk rotation angles below the range of PGA players. Pelvic rotation angle and trunk rotation angle had a direct effect on club head speed during the stroke [

30], with restricted pelvic and trunk rotation angles resulting in reduced club head speed and loss of distance to the ball.

Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations were made to characterize the full-swing technical movements of Chinese national team golfers: (a)Enhance the standardization of swing movements, compared with PGA players, our men's golf national team players in the shot preparation and top of the backswing phase of the body angle parameter deviation is larger, resulting in different technical movements between players. Through the establishment of a new scientific training concept and the development of a perfect scientific training program to standardize the players' technical movements at critical moments. (b)Strengthening physical training is recommended to stabilize the performance of body parts, form stable technical movements and improve sports performance through scientific physical training. (c)Prevention of sports injuries, in the golf swing process, the torso and pelvis large-scale twisting will cause damage to the muscles of the waist, if there is an irregular technical movement in the swing process will increase the occurrence of low back injury. It is recommended to establish correct, complete and standardized technical movements, and imitate according to the structure and sequence of technical movements, so that athletes can recognize the correct technical movements and deepen their understanding of the concepts of technical movements, thus establishing a correct representation of the movements and avoiding the occurrence of sports injuries.

5. Conclusions

In terms of start-up sequence and peak angular velocity, most players experienced an ill-timed sequence of pelvis, torso and club rotation, which was not conducive to improving club head speed and distance.

Most players have excessive pelvic rotation toward closure at the top of the backswing, which is not conducive to maximizing the hip-shoulder separation angle.

At the point of impact, most players have two major problems: too large anterior tilt angle of the torso and insufficient rotation of the torso, which will put a greater load on the lower back and even trigger the risk of sports injuries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W., G.Z. and Z.B.; methodology and validation, G.Z. and Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z., Y.Z. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.X., G.Z. and Y.Z.; supervision, Z.W. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Institute of Sport Sciences , General Administration of Sport of China fund(Basic 21-27); the Composite Team and Young Teachers' Research Ability Enhancement Project of Hebei Sport University(2023TS03) and the Sports Science and Technology Research Program of Hebei Provincial Sports Bureau(2024QS04)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hebei Sport University (2023TS03; 25 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request by the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schinkel-Ivy, A.; Drake, J.D.M. Sequencing of superficial trunk muscle activation during range-of-motion tasks. Human Movement Science 2015, 43, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glofcheskie, G.O.; Brown, S.H.M. Athletic background is related to superior trunk proprioceptive ability, postural control, and neuromuscular responses to sudden perturbations. Human Movement Science 2017, 52, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L. Biomechanical Analysis on Principles of Upper Limb Whiplash Movement. SPORT SCIENCE 2004, 24, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Richards, A.; Schadl, K.; Ladd, A.; Rose, J. The swing performance Index: Developing a single-score index of golf swing rotational biomechanics quantified with 3D kinematics. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, K.M.; Roh, E.Y.; Mahtani, G.; Meister, D.W.; Ladd, A.L.; Rose, J. Golf Swing Rotational Velocity: The Essential Follow-Through. arm 2018, 42, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, D.W.; Ladd, A.L.; Butler, E.E.; Zhao, B.; Rogers, A.P.; Ray, C.J.; Rose, J.J.J.o.a.b. Rotational biomechanics of the elite golf swing: Benchmarks for amateurs. 2011, 27, 242-251.

- Joyce, C. The most important “factor” in producing clubhead speed in golf. Human Movement Science 2017, 55, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuyagbaatar, B.; Purevsuren, T.; Kim, Y.H.J.P.o.t.I.o.M.E. , Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine. Kinematic determinants of performance parameters during golf swing. 2019, 233, 554–561. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.; Lephart, S.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Sell, T.; Smoliga, J.; Jolly, J. The role of upper torso and pelvis rotation in driving performance during the golf swing. Journal of Sports Sciences 2008, 26, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Sell, T.C.; Lephart, S.M. The relationship between biomechanical variables and driving performance during the golf swing. Journal of Sports Sciences 2010, 28, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, W.B.; Bower, R.G.; Watsford, M.L. Physical Determinants of Golf Swing Performance: A Review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2022, 36, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, J.W.L.; Hume, P.A. Evidence for biomechanics and motor learning research improving golf performance. Sports Biomechanics 2012, 11, 288–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, R.B.; Brumitt, J. Spine biomechanics associated with the shortened, modern one-plane golf swing. Sports Biomechanics 2016, 15, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BI Zhiyuan, W.Z. , Zhan Genghao,et al. Three-Dimensional Comparative Analysis on the Driver Swing Technique between Chinese and Foreign Elite Male Professional Golfers. CHINA SPORT SCIENCEAND TECHNOLOGY 2022, 58, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI Shuyuan, L.D. , ZHOU Xinglong. Kinematic Analysis of Golfer’s Full Swing Motion with Driver. Journal of Beijing Sport University 2013, 36, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHAO Zilong, W.Z. , ZHAN Genghao,WU Shuyuan,XU Huayu. Comparative Analysis of 3D Kinematics of Driver Technology between Chinese and World Elite Female Golfers. CHINA SPORT SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 2023, 59, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severin, A.C.; Tackett, S.A.; Barnes, C.L.; biomechanics, E.M.M.J.S. Three-dimensional kinematics in healthy older adult males during golf swings. 2022, 21, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Villarrasa-Sapiña, I.; Ortega-Benavent, N.; Monfort-Torres, G.; Ramon-Llin, J.; Sensors, X.G.-M.J. Test-Retest Reliability of Task Performance for Golf Swings of Medium- to High-Handicap Players. 2022, 22, 9069. [CrossRef]

- Langdown, B.L.; Bridge, M.W.; Strength, F.-X.L.J.J.o.; Research, C. The Influence of an 8-Week Strength and Corrective Exercise Intervention on the Overhead Deep Squat and Golf Swing Kinematics. 2023, 37, 291-297. [CrossRef]

- Sorbie, G.G.; Glen, J.; Strength, A.K.R.J.J.o.; Research, C. Positive Relationships Between Golf Performance Variables and Upper Body Power Capabilities. 2021, 35. [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.-R.; Tools, S.B.P.J.M. ; Applications. Cnn And Bi-Lstm Based 3d Golf Swing Analysis By Frontal Swing Sequence Images. 2021, 80, 8957–8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbie, G.G.; Grace, F.M.; Gu, Y.; Baker, J.S.; sciences, U.C.U.J.J.o.s. Electromyographic analyses of the erector spinae muscles during golf swings using four different clubs. 2018, 36, 717-723. [CrossRef]

- Faux, L.; Carlisle, A.; Vickers, J.; sciences, C.D.J.J.o.s. The effect of alterations in foot centre of pressure on lower body kinematics during the five-iron golf swing. 2019, 37, 2014-2020. [CrossRef]

- Gluck, G.S.; Bendo, J.A.; Spivak, J.M.J.T.S.J. The lumbar spine and low back pain in golf: a literature review of swing biomechanics and injury prevention. 2008, 8, 778-788.

- McHardy, A.; Pollard, H. Muscle activity during the golf swing. Br J Sports Med 2005, 39, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgain, M.; Rouch, P.; Rouillon, O.; Thoreux, P.; Sauret, C. Golf Swing Biomechanics: A Systematic Review and Methodological Recommendations for Kinematics. Sports (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; McGrath, D.; Wallace, E.S. The relationship between the golf swing plane and ball impact characteristics using trajectory ellipse fitting. Journal of Sports Sciences 2017, 36, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, C.; Burnett, A.; Cochrane, J.; Ball, K. Three-dimensional trunk kinematics in golf: between-club differences and relationships to clubhead speed. Sports Biomech 2013, 12, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgain, M.; Hybois, S.; Thoreux, P.; Rouillon, O.; Rouch, P.; Sauret, C. Effect of shoulder model complexity in upper-body kinematics analysis of the golf swing. J Biomech 2018, 75, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgain, M.; Sauret, C.; Marsan, T.; Perez, M.J.; Rouillon, O.; Thoreux, P.; Rouch, P. Influence of the projection plane and the markers choice on the X-factor computation of the golf swing X-factor: a case study. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 2020, 23, S45–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).