1. Introduction

Landing is a fundamental task in sports performance. In particular, the ability to land effectively on one leg from various heights plays a critical role during competition [

1]. However, the ground reaction force and kinetic energy generated upon landing impose substantial mechanical loads on the lower limb joints. Inadequate energy absorption can subject vulnerable tissues—such as ligaments and cartilage—to excessive stress, thereby increasing the risk of injury [

2].

In sports such as basketball, badminton, and handball, athletes frequently perform rapid directional changes or decelerations immediately following landing. These movements are often associated with non-contact injuries, particularly due to concentrated ground reaction forces and rotational torque applied to the hip and knee joints. Such forces increase susceptibility to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries and valgus-related stress, which can compromise athletic performance and lead to long-term functional impairments [

3,

4].

Unlike simple vertical drop landings, landing followed by directional changes involves more complex biomechanical loads. Simultaneously generated vertical and horizontal shear forces, as well as rotational torque, induce compressive and torsional stress on the joints, affecting cartilage, ligaments, and surrounding musculature [

5]. This complexity is especially evident when athletes perform rapid lateral or backward movements from a single-leg support position, where both agility and postural stability are required. Failure to adapt appropriately to such demands may result in coordination loss, balance disruption, or acute injury [

6,

7]. These risks highlight the need for preventive strategies and task-specific training interventions targeting high-risk sports maneuvers.

Although previous studies have examined landing mechanics, most have focused on simplified tasks such as double leg drop landings rather than dynamic, functional movements that better reflect actual sports contexts [

8]. Research has shown that post-landing directional changes are linked to injuries including ankle sprains, patellar tendinopathy, and ACL tears. Increased peak vertical ground reaction forces and knee valgus moments have been identified as key risk factors. Additionally, individuals with ankle instability demonstrate prolonged stabilization times and elevated center of pressure (COP) values during deceleration or cutting maneuvers, indicating impaired postural control [

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Accordingly, there is a clear need for biomechanical research targeting dynamic, sport-specific movements such as post-landing directional changes.

To manage rapid transitions effectively, athletes must integrate lower limb biomechanics with neuromuscular control mechanisms [

15]. For instance, increased hip and knee flexion serve as compensatory responses for ankle instability, aiding in shock absorption and torque reduction [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Conversely, insufficient flexion combined with increased knee valgus angles and moments elevates joint loading and injury risk, underscoring the importance of neuromuscular training to mitigate such stresses [

20].

In recent years, perturbation-based training (PBT) has garnered increasing attention in the fields of sports and rehabilitation. This form of training involves the intentional application of unpredictable changes in direction and velocity, prompting the body to reflexively adapt and recover through repeated exposure. As a result, it has been reported to enhance neuromuscular reactivity, sensorimotor integration, and postural control strategies in an integrated manner [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Notably, perturbation-based training goes beyond simple muscle strengthening by improving dynamic stability, enabling the body to respond more efficiently and promptly to irregular and unpredictable environments similar to actual sports settings [

24,

26,

27,

28].

Among various forms of external perturbation, the inertial load of water is characterized by its high level of instability. Rather than merely increasing the contractile strength of isolated muscles, it stimulates the integrated regulatory function between the nervous and muscular systems, thereby promoting adaptation within the motor control system [

29,

30]. A representative tool that applies this principle in training is the waterbag, which creates instability by containing water that moves dynamically in response to body motion, thereby providing an inertial load. The constantly shifting speed and direction of the water generates effective external perturbation. These characteristics suggest that the waterbag is a suitable device for simulating the instability encountered in real sports scenarios, and it holds practical value as a training intervention for improving dynamic stability and preparing for high-risk sports maneuvers [

31].

Joint moments, as key factors in force transmission and postural control, are major biomechanical indicators of lower-limb injury risk. Therefore, evaluating how perturbation-based training affects lower extremity joint moments during dynamic movements may provide insight into its role in injury prevention and motor control improvement. In addition, it was hypothesized that perturbation-based training using water-inertia load would significantly improve the ability to control lower extremity joint moments during post-landing directional changes.

While many previous studies utilizing inertial loads of water have emphasized unstable surface training, few have directly applied external perturbations in dynamic, multidirectional tasks. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to compare and analyze the effects of dynamic stability training using the inertial load of water on lower limb biomechanical factors—specifically, joint moments in the hip, knee, and ankle—during post-landing directional changes. This study aims to explore the potential of water-inertia-based training as an effective intervention for enhancing stability and preventing injury during rapid directional transitions following landing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

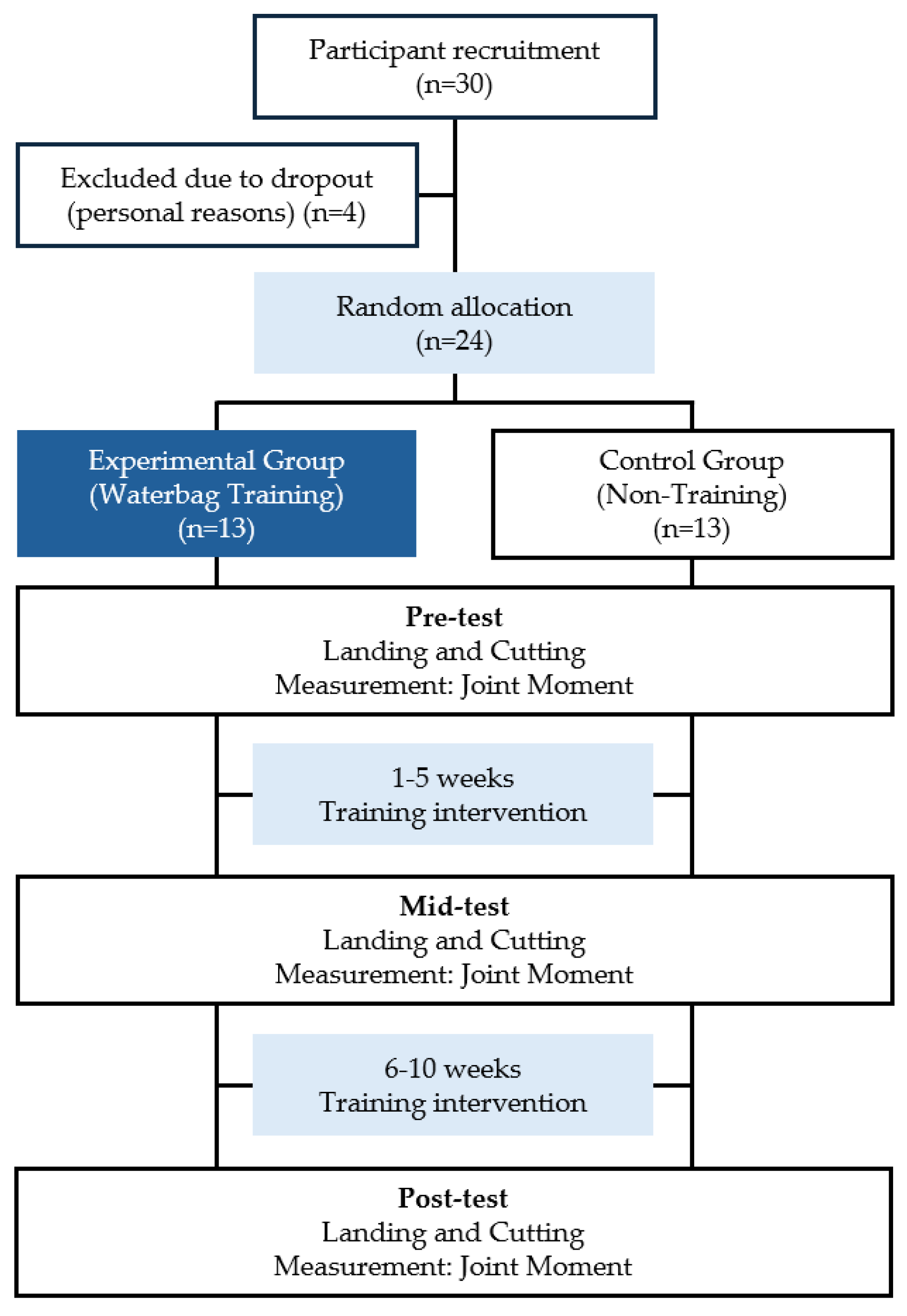

A total of 30 male university students in their 20s participated in this study. Recruitment was conducted by posting a recruitment notice at B University, located in region B. All participants received a thorough explanation of the study's purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent.

The appropriate sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 for Windows, with an effect size of 0.25, statistical power of 0.8, and a significance level of 0.05. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 24 participants would be required. However, considering potential dropouts, a total of 30 participants were initially recruited.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 15) or the control group (n = 15). During the study, four participants withdrew due to military enlistment, resulting in a final sample size of 26 participants (experimental group: 13, control group: 13) included in the data analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202504-01-008) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT07117617).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants were as follows:

Inclusion criteria:

- (1)

Healthy adult males aged between 20 and 29 years.

Exclusion criteria:

- (1)

History of surgery affecting lower limb function within the past year.

- (2)

Current injuries or medical conditions.

- (3)

Inability to perform movements due to acute inflammation or severe pain.

The results of the homogeneity test showed no significant differences between the groups in terms of age (t = –0.855), height (t = –0.020), and weight (t = 0.871), indicating that all physical characteristics were statistically similar across groups. Additionally, all participants reported that they had not engaged in any structured physical activity during the six months prior to the study.

Table 1 presents the general physical characteristics of the participants, and

Figure 1 illustrates the study flow diagram.

2.2. Assessment and Data Acquisition

Biomechanical data, including joint moments of the hip, knee, and ankle, were measured using a three-dimensional motion analysis system consisting of six infrared cameras (Vicon MX-T20, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) and sixteen reflective markers (14 mm diameter). Reflective markers were bilaterally attached to anatomical landmarks, including the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), mid-lateral thigh, lateral femoral epicondyle, mid-shank, lateral malleolus, second metatarsal head, and calcaneus. Anthropometric measurements, including height, body weight, lower limb length, knee joint width, and ankle joint width, were collected using a tape measure and caliper and input into the Plug-in Gait system prior to analysis. All motion capture data were sampled at 1000 Hz. Joint moments were calculated using the Plug-in Gait dynamic model. Moment values (N·mm) were converted to N·m. All values were post-processed prior to statistical analysis (

Figure 2).

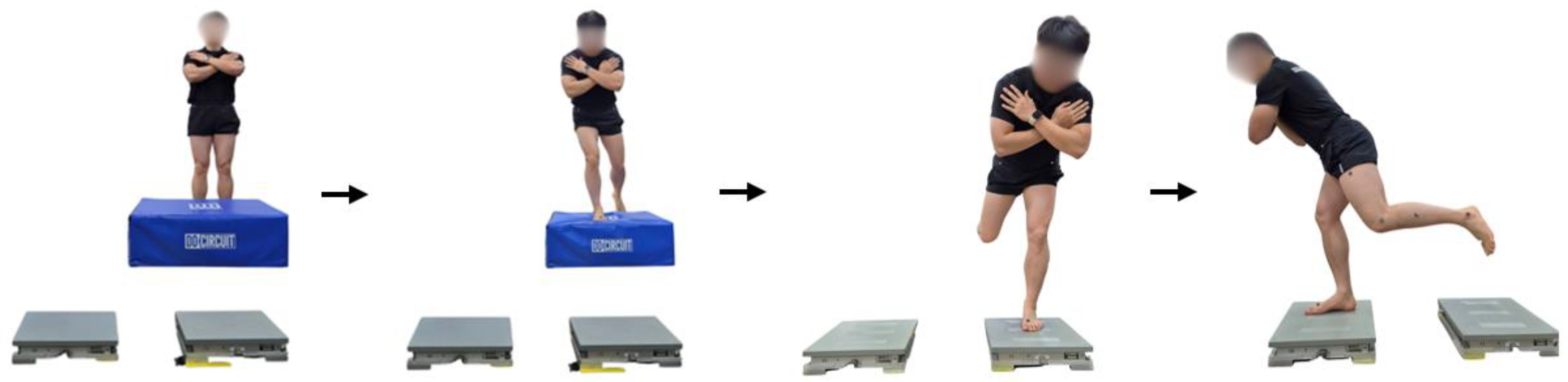

The movement task involved a landing followed by a cutting. Participants began from a standing position on the floor and, following the examiner's cue, stepped onto a 30 cm-high box using one leg, then landed on the opposite leg and immediately cutting using that leg [

32]. The task was designed so that participants landed with their non-dominant leg and then performed a 90-degree cutting using their dominant leg. This protocol was based on prior research indicating that dominant limbs are typically used to initiate propulsion in both sports and daily movements [

18]. The dominant leg is known to play a key role in generating propulsive force and executing direction changes [

33]. Accordingly, this study applied a dominant leg-centered cutting strategy. Dominant leg determination was made by asking participants which leg they would naturally use to kick a ball, a method commonly used in previous studies as a standardized approach for identifying limb dominance [

34]. To ensure familiarity with the task, participants practiced the movement approximately three times prior to testing. Three successful trials were then recorded, and the mean of those trials was used for analysis. Sufficient rest was provided between attempts.

The analysis was divided into two phases: (1) the landing phase (from initial ground contact to toe-off) and (2) the change-of-direction phase (from initial ground contact to 3-second stabilization). The directional change was performed at the participant's maximum voluntary speed, and a 90-degree turning angle was marked on the floor to guide the movement. Since most sports involve multidirectional movements, directional changes at wider angles are common [

35]. Previous studies have reported that executing a 90-degree turn increases hip flexion, which helps reduce the load on the knee joint and contributes to postural support [

36]. Therefore, a 90-degree turn was selected in this study to emphasize stability and body support during the change-of-direction task.

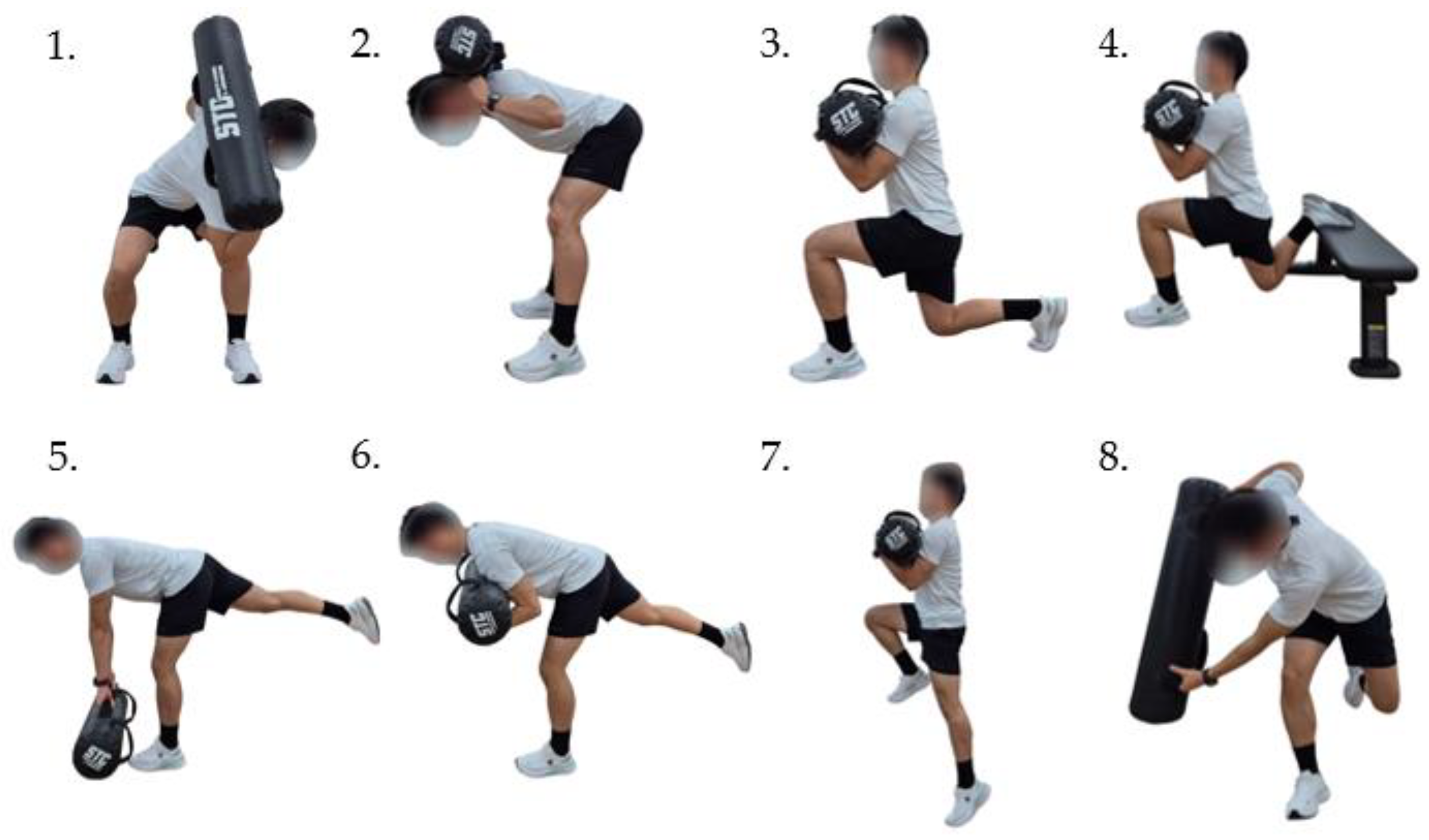

2.3. Exercise Intervention

The Dynamic Stability Training (DST) program implemented in this study was based on Bernstein’s Dynamic Systems Theory, as described by Davids et al. [

37], and the Dynamic Stability Training protocol proposed by Kang and Park [

29]. The program was structured into progressive stages and conducted twice per week for 10 weeks, totaling 20 sessions. Each session lasted 50 minutes, comprising a 10-minute warm-up, 30 minutes of main exercises, and a 10-minute cool-down. Details on the exercise methods and number of sets are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3.

The training program was organized in a stepwise manner from week 0 to week 10, focusing on exercises involving bilateral stance, locomotor movements, single-leg stance, jumping or acceleration/deceleration, and directional changes.

The experimental group performed the exercises using a water-filled waterbag, as shown in

Figure 4. The water load was adjusted based on the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), following the method described by Da Silva, Silva, Ahmadi, and Teixeira [

38]. Prior to the intervention, each participant’s RPE was assessed based on handling different waterbag loads (3–8 kg), and the target intensity was set at a moderate level (RPE 6–7).

From weeks 0 to 5, training intensity was based on the pre-intervention RPE assessment. From weeks 6 to 10, the RPE was reassessed prior to the start of week 6, and training intensity was adjusted accordingly for the second half of the program.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated as means and standard deviations. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality. To evaluate the effects of the intervention, a two-way mixed-design ANOVA (3 time points: pre, mid, post × 2 groups: experimental, control) was conducted. When significant interaction or time main effects were identified, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise t-tests were used for within-group comparisons across time (Bonferroni-adjusted α = 0.0167; 0.05/3). Additionally, for variables showing a significant group main effect, an independent samples t-test was performed at the post-intervention time point to examine between-group differences. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for between-group comparisons.

For clarity, joint moments originally labeled as Moment X, Y, and Z are presented using anatomical terms: flexion/extension (X-axis), abduction/adduction (Y-axis), and internal/external rotation (Z-axis). The sign convention was defined such that positive values represent flexion, abduction, and external rotation moments, while negative values represent extension, adduction, and internal rotation moments.

3. Results

The results related to lower-limb joint moment variables during the landing and cutting phases are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Normality

Based on the Shapiro–Wilk test, approximately 67% of all variables satisfied the assumption of normality (p > .05). Most violations were observed in pre-intervention values. Despite this, the mixed-design two-way ANOVA was considered appropriate, given its robustness to minor deviations from normality. For variables with significant group or time effects, follow-up t-tests were conducted with appropriate group-wise normality and homogeneity checks.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD) of each variable by group and time point are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

3.2. Landing Phase

In the landing phase, significant main effects of group were observed for hip flexion/extension moment (p = 0.009), hip abduction/adduction moment (p = 0.003), knee abduction/adduction moment (p = 0.003), knee internal/external rotation moment (p = 0.005), and ankle internal/external rotation moment (p = 0.012). In each case, the experimental group demonstrated generally lower hip flexion/extension moments and higher knee and ankle internal/external rotation moments compared to the control group. Although post-intervention pairwise comparisons suggested differences in several variables, these did not meet the Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold and should be interpreted with caution.

3.3. Cutting Phase

In the cutting phase, no significant group main effects or interactions were observed for any joint moment variables after Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.0167). A significant main effect of time was found for knee abduction/adduction moment (p = 0.007), but post-hoc pairwise comparisons did not meet the adjusted significance threshold. These results suggest that dynamic stability training using an inertial load of water did not produce statistically significant changes in joint moments during cutting, although some variables showed trends consistent with the hypothesized intervention effects.

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of dynamic stability training using inertial water load on lower limb biomechanics and balance control during landing and change-of-direction tasks. While directional changes after landing impose complex loads on the lower limb joints [

4,

11], most prior studies have focused on static double-leg landings, which do not reflect real sports scenarios [

8].

Training with inertial water load generates unpredictable perturbations due to fluid oscillation, stimulating neuromuscular responses and enhancing balance control [

31,

39]. This method more closely simulates dynamic sports environments and helps athletes adapt to fluctuating loads during direction changes.

To replicate real-world demands, this study used a task involving landing on the non-dominant leg followed by a cutting movement with the dominant leg. The discussion focuses on the landing and cutting phases, interpreting significant joint moment findings in relation to physiological mechanisms activated by perturbation-based training.

In the landing phase, the experimental group exhibited significant group main effects for hip flexion/extension moment (Hip Moment X), hip abduction/adduction moment (Hip Moment Y), knee abduction/adduction moment (Knee Moment Y), knee internal/external rotation moment (Knee Moment Z), and ankle internal/external rotation moment (Ankle Moment Z) compared to the control group. These patterns suggest improved impact absorption, reduced reliance on proximal joint loading, and enhanced neuromuscular control with load redistribution toward distal joints such as the knee and ankle [

40,

41,

42].

Although post-intervention pairwise comparisons indicated favorable changes, these differences did not remain statistically significant after Bonferroni adjustment. Nevertheless, the large effect sizes imply meaningful adaptations that may contribute to lateral stability [

43,

44,

45] and improved coordination between trunk, hip, and knee during rotational loading [

7,

31,

46].

Additionally, greater ankle external rotation moments in the experimental group may indicate enhanced rotational control at the distal joint level, which could help reduce injury risk during dynamic tasks [

7,

8].

In the cutting phase (i.e., the 3-second stabilization period following direction change), no variables showed significant interaction or time main effects after Bonferroni adjustment. However, the experimental group demonstrated a tendency toward greater frontal plane knee abduction/adduction moment (Knee Moment Y) compared to the control group. This pattern may indicate enhanced engagement in frontal plane knee control after perturbation-based training.

Frontal plane knee abduction moments are biomechanically linked to valgus control and mediolateral joint stability. The observed tendency suggests potential improvements in neuromuscular response and lateral stabilization capacity developed through training [

35,

51]. Perturbation-based interventions have been shown to improve neuromuscular coordination and increase responsiveness of muscles responsible for frontal plane control [

30,

50].

These observations imply that participants in the experimental group may have become more capable of producing compensatory frontal plane torque in response to destabilizing forces. Such adaptations could contribute to more effective load distribution and active stabilization of the knee, potentially reducing the risk of non-contact injuries such as ACL ruptures by improving joint alignment and control under multidirectional demands.

This study empirically demonstrated that dynamic stability training utilizing the inertial load of water, which simulates realistic and unpredictable environments, significantly enhances complex movement performance compared to routine activities or no training. The perturbation-based nature of this training likely contributed to improved neuromuscular coordination, rotational control, and mediolateral stability, all of which are essential for injury prevention and efficient movement in high-demand tasks. These findings support its use as a practical and evidence-based strategy in both athletic and rehabilitation settings.

Moreover, the task design—requiring landing on the non-dominant leg followed by a directional change using the dominant leg—reflected real-world sports demands. Since the non-dominant limb generally shows lower neuromuscular capacity [

52], the inertial water load likely promoted enhanced postural control and propulsion regulation during the initial landing, facilitating smoother subsequent movement. The training appears to have strengthened interlimb neuromuscular coordination, a key factor in adapting to variable loading [

53,

54,

55]. Improvements observed in joint moment patterns suggest not only gains in muscular output but also more sophisticated biomechanical regulation. These outcomes align with prior studies [

24,

29,

30,

45], reinforcing the value of water-based perturbation training in dynamic post-landing scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that dynamic stability training using an inertial water load improved joint moment regulation during landing and cutting tasks, particularly enhancing rotational control and mediolateral stability under perturbations. Such improvements suggest better neuromuscular coordination and load redistribution across joints, contributing to greater energy efficiency and potential injury prevention. The training protocol showed high ecological validity by replicating real sports scenarios involving non-dominant leg landings and directional changes. Future research should explore its application to diverse populations—including youth, elderly, and injured athletes—and assess its long-term functional benefits. Overall, this strategy offers a practical, evidence-based approach to enhancing dynamic movement control and reducing injury risks in both athletic and rehabilitation settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.P. and C.K.L. and M.J.S and J.Y.L; methodology, I.B.P. and C.K.L.; soft- ware, M.J.S and J.Y.L.; validation, M.J.S and J.Y.L.; formal analysis, M.J.S and J.Y.L.; investigation, J.Y.L.; data curation, J.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.L.; writing—review and editing, I.B.P. and C.K.L. and M.J.S and J.Y.L.; visualization, J.Y.L.; supervision, I.B.P. and C.K.L. and M.J.S and J.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Public Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202504-01-008, approval date: 07 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Professors Il Bong Park and Chae Kwan Lee for their insightful guidance and continuous encouragement throughout the entire course of this study. We also sincerely thank Professor Min ji Son for her expert advice and support in the experimental design and research process. This study was made possible with the efforts and support of many individuals. This manuscript is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Minji Son was employed by JEIOS Inc.; however, this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The remaining authors also declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Waldén, M.; Krosshaug, T.; Bjørneboe, J.; Andersen, T.E.; Faul, O.; Hägglund, M. Three distinct mechanisms predominate in non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male professional football players: a systematic video analysis of 39 cases. Br J Sports Med 2015, 49, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeow, C. H.; Lee, P. V.; Goh, J. C. Effect of landing height on frontal plane kinematics, kinetics and energy dissipation at lower extremity joints. J Biomech 2009, 42, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosshaug, T.; Nakamae, A.; Boden, B. P.; Engebretsen, L.; Smith, G.; Slauterbeck, J. R.; Hewett, T. E.; Bahr, R. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: video analysis of 39 cases. Am J Sports Med 2007, 35, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padua, D. A.; DiStefano, L. J.; Beutler, A. I.; de la Motte, S. J.; DiStefano, M. J.; Marshall, S. W. The Landing Error Scoring System as a Screening Tool for an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury-Prevention Program in Elite-Youth Soccer Athletes. J Athl Train 2015, 50, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besier, T. F.; Lloyd, D. G.; Ackland, T. R.; Cochrane, J. L. Anticipatory effects on knee joint loading during running and cutting maneuvers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T. Biomechanical mechanisms and prevention strategies of knee joint injuries on football: An in-depth analysis based on athletes’ movement patterns. MCB 2024, 21, 524–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokochi, Y.; Shultz, S. J. Mechanisms of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Athl Train 2008, 43, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahunt, E.; Monaghan, K.; Caulfield, B. Changes in lower limb kinematics, kinetics, and muscle activity in subjects with functional instability of the ankle joint during a single leg drop jump. J Orthop Res 2006, 24, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, B. P.; Dean, G. S.; Feagin, J. A.; Garrett, W. E. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics 2000, 23, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, D.; Melnyk, M.; Gollhofer, A. Gender and fatigue have influence on knee joint control strategies during landing. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2009, 24, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, M.; Pasanen, K.; Kujala, U. M.; Vasankari, T.; Kannus, P.; Äyrämö, S.; Krosshaug, T.; Bahr, R.; Avela, J.; Perttunen, J.; et al. Stiff Landings Are Associated With Increased ACL Injury Risk in Young Female Basketball and Floorball Players. Am J Sports Med 2017, 45, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadi, S.; Ebrahimi, I.; Salavati, M.; Dadgoo, M.; Jafarpisheh, A. S.; Rezaeian, Z. S. Attentional Demands of Postural Control in Chronic Ankle Instability, Copers and Healthy Controls: A Controlled Cross-sectional Study. Gait posture 2020, 79, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. D.; Stewart, E. M.; Macias, D. M.; Chander, H.; Knight, A. C. Individuals with chronic ankle instability exhibit dynamic postural stability deficits and altered unilateral landing biomechanics: A systematic review. Phys Ther Sport 2019, 37, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B. L.; De La Motte, S.; Linens, S.; Ross, S. E. Ankle instability is associated with balance impairments: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009, 41, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazulak, B. T.; Hewett, T. E.; Reeves, N. P.; Goldberg, B.; Cholewicki, J. Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: a prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. Am J Sports Med 2007, 35, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Son, S. J.; Seeley, M. K.; Hopkins, J. T. Altered movement strategies during jump landing/cutting in patients with chronic ankle instability. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2019, 29, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, E.; Shiyko, M. P.; Ford, K. R.; Myer, G. D.; Hewett, T. E. Biomechanical Deficit Profiles Associated with ACL Injury Risk in Female Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016, 48, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C. D.; Sigward, S. M.; Powers, C. M. Limited hip and knee flexion during landing is associated with increased frontal plane knee motion and moments. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2010, 25, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.S. Change-of-Direction Biomechanics: Is What's Best for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Also Best for Performance? Sports Med 2018, 48, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, N.; Morrison, S.; Van Lunen, B. L.; Onate, J. A. Landing technique affects knee loading and position during athletic tasks. J Sci Med Sport 2012, 15, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, A.; Danells, C. J.; Inness, E. L.; Musselman, K.; Salbach, N. M. A survey of Canadian healthcare professionals' practices regarding reactive balance training. Physiother Theory Pract 2021, 37, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, Y.; Brodie, M. A.; Sturnieks, D. L.; Hicks, C.; Carter, H.; Toson, B.; Lord, S. R. Exposure to trips and slips with increasing unpredictability while walking can improve balance recovery responses with minimum predictive gait alterations. PloS one 2018, 13, e0202913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, M. H. G.; McCrum, C.; Mansfield, A.; Meijer, K. Perturbation-based balance training for falls reduction among older adults: Current evidence and implications for clinical practice. Geriatr Gerontol In, 2017, 17, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, C.; Bhatt, T. S.; Gerards, M. H. G.; Karamanidis, K.; Rogers, M. W.; Lord, S. R.; Okubo, Y. Perturbation-based balance training: Principles, mechanisms and implementation in clinical practice. Front Sports Act Living, 2022, 4, 1015394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, D.; Kang, J.; Aprigliano, F.; Staudinger, U. M.; Agrawal, S. K. Acute Effects of a Perturbation-Based Balance Training on Cognitive Performance in Healthy Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Front Sports Act Living, 2021, 3, 688519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, S.; Mandla-Liebsch, M.; Mersmann, F.; Arampatzis, A. Exercise of Dynamic Stability in the Presence of Perturbations Elicit Fast Improvements of Simulated Fall Recovery and Strength in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Sports Act living 2020, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, A.; Bozzato, M.; Rotundo, L.; Zullo, G.; De Vito, G.; Paoli, A.; Marcolin, G. Multimodal training protocols on unstable rather than stable surfaces better improve dynamic balance ability in older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2024, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, J. E.; Hsu, W. L. Effects of Dynamic Perturbation-Based Training on Balance Control of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 17231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Instability Neuromuscular Training Using an Inertial Load of Water on the Balance Ability of Healthy Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I.; Ha, M. S. Effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training using the inertial load of water on functional movement and postural sway in middle-aged women: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Women's Health 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wezenbeek, E.; Verhaeghe, L.; Laveyne, K.; Ravelingien, L.; Witvrouw, E.; Schuermans, J. The Effect of Aquabag Use on Muscle Activation in Functional Strength Training. J Sport Rehabil 2022, 31, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsurin, K.; Vachalathiti, R.; Srisangboriboon, S.; Richards, J. Knee joint coordination during single-leg landing in different directions. Sports biomech 2020, 19, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyama, M.; Nosaka, K. Influence of surface on muscle damage and soreness induced by consecutive drop jumps. J Strengt Cond Res 2004, 18, 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- van Melick, N.; Meddeler, B. M.; Hoogeboom, T. J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W. G.; van Cingel, R. E. H. How to determine leg dominance: The agreement between self-reported and observed performance in healthy adults. PloS one 2017, 12, e0189876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigward, S. M.; Cesar, G. M.; Havens, K. L. Predictors of Frontal Plane Knee Moments During Side-Step Cutting to 45 and 110 Degrees in Men and Women: Implications for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Clin J Sport Med 2015, 25, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, K. L.; Sigward, S. M. Joint and segmental mechanics differ between cutting maneuvers in skilled athletes. Gait posture 2015, 41, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davids, K.; Glazier, P.; Araújo, D.; Bartlett, R. Movement systems as dynamical systems: the functional role of variability and its implications for sports medicine. Sports Med (Auckland, N.Z.) 2003, 33, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D. T. C.; Silva, K. D. S.; Ahmadi, S.; Teixeira, L. F. M. Indoor-cycling classes: Is there a difference between what instructors predict and what practitioners practice? JPES 2019, 19, 772–780. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Martel, V.; Santuz, A.; Bohm, S.; Arampatzis, A. Neuromechanics of Dynamic Balance Tasks in the Presence of Perturbations. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2021, 14, 560630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazulak, B. T.; Hewett, T. E.; Reeves, N. P.; Goldberg, B.; Cholewicki, J. The effects of core proprioception on knee injury: a prospective biomechanical-epidemiological study. The American journal of sports medicine 2007, 35, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R. J.; Cone, J. C.; Tritsch, A. J.; Pye, M. L.; Montgomery, M. M.; Henson, R. A.; Shultz, S. J. Changes in drop-jump landing biomechanics during prolonged intermittent exercise. Sports health 2014, 6, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagenbaum, R.; Darling, W. G. Jump landing strategies in male and female college athletes and the implications of such strategies for anterior cruciate ligament injury. The American journal of sports medicine 2003, 31, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabello, R.; Nodari, C.; Scudiero, F.; Borges, I.; Fitarelli, L.; Bianchesse, J.; Rodrigues, R. Effects of task and hip-abductor fatigue on lower limb alignment and muscle activation. Sport Sciences for Health 2022, 18, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Zheng, X.; An, B.; Zheng, J. The effect of hip abductor fatigue on knee kinematics and kinetics during normal gait. Frontiers in neuroscience 2022, 16, 1003023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. S.; Silva, P. B.; Lund, M. E.; Farina, D.; Kersting, U. G. Balance Training Enhances Motor Coordination During a Perturbed Sidestep Cutting Task. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2017, 47, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neptune, R. R.; Zajac, F. E.; Kautz, S. A. Muscle force redistributes segmental power for body progression during walking. Gait & posture 2004, 19, 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, J.R. The Age-Associated Reduction in Propulsive Power Generation in Walking. Exercise and sport sciences reviews 2016, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, C.M. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2010, 40, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, M. L.; Lloyd, E. M. Age and stepping limb performance differences during a single-step recovery from a forward fall. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2005, 60, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J.; Park, I. B. Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Water Inertia Load on Gait and Biomechanics in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology 2025, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, T. E.; Myer, G. D.; Ford, K. R.; Heidt, R. S., Jr.; Colosimo, A. J.; McLean, S. G.; van den Bogert, A. J.; Paterno, M. V.; Succop, P. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine 2005, 33, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promsri, A.; Haid, T.; Werner, I.; Federolf, P. Leg Dominance Effects on Postural Control When Performing Challenging Balance Exercises. Brain sciences 2020, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd, A. T.; Singh, R. E.; Iqbal, K.; White, G. A perspective on muscle synergies and different theories related to their adaptation. Biomechanics 2021, 1, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, O.; Soylu, Y.; Erkmen, N.; Kaplan, T.; Batalik, L. Effects of proprioceptive training on sports performance: a systematic review. BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation 2024, 16, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E. J.; Guo, Y.; Martinez-Valdes, E.; Negro, F.; Stashuk, D. W.; Atherton, P. J.; Phillips, B. E.; Piasecki, M. Acute adaptation of central and peripheral motor unit features to exercise-induced fatigue differs with concentric and eccentric loading. Experimental physiology 2023, 108, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).