1. Introduction

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with both acute and chronic end stage liver failure. As outcomes following liver transplantation have improved, the indications for liver transplantation have widened and a shortage of suitable organ donors has developed. This has resulted in the increased use of grafts from marginal donors such as the elderly, those with a steatotic liver and those from donors following cardiac death (DCD). The use of liver DCD grafts in the UK has increased from 6.9% in 2005 [

1] to 28.7% in 2023 [

2]. DCD grafts suffer a more prolonged ischaemic injury during the retrieval stage. The use of grafts from DCD donors is associated with reduced patient and graft survival [

1,

3].

Ischaemia Reperfusion (IR) injury is the damage that occurs to an organ when its blood supply is interrupted and reconstituted. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality following liver transplantation and is believed to account for up to 10% of early graft loss [

4].

Many molecular pathways have been identified that drive IR injury but the immune system has been shown to play a major role [

5]. Athymic mice, which lack T cells, are protected from the reperfusion phase of IR injury despite suffering the same ischaemic damage [

6]. Reconstitution of CD4+ T cells makes these mice susceptible to IR injury and this has been replicated in several studies [

7,

8]. The same phenomenon is not seen when CD8+ T cells are reconstituted. This has also been shown in renal [

9], intestinal [

10] and pulmonary [

11] IR injury. The rapid speed of this CD4+T cell response is atypical and studies have shown that it is not antigen dependent activation of T cells that drives it, as blocking antigen activation of T cells with MHC Class II antibodies has no effect on IR injury [

12,

13]. There may be a role for inflammatory monocytes with activation by Damage Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) [

14]. Monocytes are rapidly recruited (within hours) [

15] to damaged or ischaemic tissue by CCL2 [

16]. Furthermore there is evidence of an interplay between the innate immune cells and CD4+ T cells [

13]. TLR4 has been highlighted as a key pathway in immune activation, both in CD4+ T cells and in the closely associated dendritic cells [

13] and this would be in keeping with the timescale of IR injury. When linked with further studies that have identified HMGB1, which interacts with TLR4, as an essential mediator of IR injury [

17,

18] it is more likely that the TLR pathway of immune activation, rather than TCR stimulation, is responsible for propagating IR injury.

Although there is extensive evidence of immune cell infiltration and activation in murine models of IR injury, there is very little evidence in humans.

An analysis of cytokines before and after human liver transplant demonstrated that higher levels of CCL2, IL8, CCL5, CXCL9, IP10 and IL-2 were associated with the development of Early Allograft Dysfunction (EAD), which is associated with graft preservation and IR injury [

19]. However, this study was limited to circulating cytokine analysis in 73 patients and samples were only collected pre-operatively and on day 1, 7, 14 and 30 post-op. No liver biopsies were available for analysis.

A study in human living donor liver transplantation measured cytokine levels pre-operatively and on the 7th day post-operatively in 226 patients. It found that higher post-operative serum levels of IL-6 and IL-17 were associated with EAD but these were only measured on post-operative day 7 [

20]. We know that graft injury occurs early following liver transplant and identifying early immune changes at this stage will lead to therapies to ameliorate IR injury.

Thus, the aim of this study was to map peripheral and liver graft immune cell changes and their associated cytokines in the early peri-operative period and correlate these findings with graft and patient outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Samples, Plasma and Immune Cell Isolation

Blood, liver and perfusate samples were collected from adult patients undergoing first elective deceased donor liver transplantation at the Royal Free Hospital, London who were recruited to the Remote Ischaemic Preconditioning in Orthotopic Liver Transplantation (RIPCOLT) study, clinical trial number 8191 ethical approval number 11/H0720/4 [

21,

22].

50mls of peripheral arterial blood were collected from the routinely placed arterial line at the following time intervals:

baseline (following induction of anaesthesia but before abdominal incision),

immediately before removal of the recipient’s liver,

2 hours post reperfusion in the recipient of the donor graft,

24 hours post-operatively.

The University of Wisconsin solution that the grafts were transported in and the human albumin solution that was used to flush the grafts prior to reperfusion were collected. A post reperfusion biopsy was performed routinely. Following an ethical amendment, a pre-reperfusion biopsy was also collected in 5 patients.

Ten mls of the arterial blood sample was immediately centrifuged at 1000g for ten minutes to obtain plasma which was stored at -800C until analysis.

2.2. Isolation of Immune Cells

To accurately reflect the in vivo environment, immune cells were isolated and analysed fresh from liver biopsies, blood and transport fluid (without further stimulation) through manual homogenization and density centrifugation (see online supplementary experimental methods) as previously described [

23]. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Intra Hepatic Lymphocytes were similarly stained to allow analysis by flow cytometry.

2.3. Plasma Cytokine Measurements

Plasma concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α were measured using a LEGENDplex multiparametric bead-based immunoassay (Human Th cytokine 5 plex mix and match subpanel Biolegend, UK). The LEGENDplex was performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Plasma concentrations of CCL2 (Biolegend, UK), CCL5 (Biolegend, UK), IL-8 (Biolegend, UK), IL-17A (Biolegend, UK) were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

2.4. Flowcytometry

For cell surface markers, cells were incubated with fluorescently-conjugated antibodies at 40C for 30 minutes. For intra-cellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilised with Human FoxP3 Buffer Set (BD Bioscience, UK). Dead cells were identified with a fixable viability dye (ThermoFisher, UK) and excluded. Samples were analysed on a LSRII flow cytometer running FACSDiva software (BD Bioscience, UK). The list of antibodies used and the gating strategy are contained in online supplementary experimental methods.

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

All flow cytometry data was analysed using FlowJo V.9-10 (FlowJo LLC). Statistical analysis was carried out on Prism V.10 (GraphPad). Median average values and non-parametric testing was used throughout.

3. Results

Samples were collected from 28 patients undergoing elective first liver transplant surgery. Background clinical information and peri transplant outcomes are shown in

Table 1.

3.1. Cytokines Associated with Inflammatory Monocyte Recruitment and Activation Were Elevated in the Peri Transplant Period and Correlated with Graft Outcomes

Circulating levels of CCL2, CCL5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-17A were raised significantly from baseline following mobilization of the recipient liver and at 2 hours post reperfusion of the donor graft. Circulating levels of these cytokines returned to pre-operative levels within 24 hours following the transplant surgery (

Table 2). Circulating levels of IL-2, IFNγ and TNFα were not significantly raised at any time point during the transplant procedure or in the first 24 post operative hours.

Fifteen patients suffered from Early Allograft Dysfunction (EAD) [

24]. These patients had significantly higher plasma levels of IL-10 at 2 hours post reperfusion than those who did not suffer from EAD [747.69(462.15-1336.7)pg/ml vs 420.43(338.05-561.39)pg/ml, p=0.008]. Patients who suffered from EAD had significantly higher levels of CCL2, the inflammatory chemokine which attracts monocytes, at 24 hours post reperfusion [105.96(70.61-238.45)pg/ml vs 53.49(35.77-77.73)pg/ml, p=0.013]

There were no correlations between circulating cytokine levels post reperfusion and ischaemic liver injury as measured by liver aspartate transferase levels on day 3 [

25]. However elevated CCL2 levels, measured at 24 hours post-reperfusion significantly correlated with increased AST levels on day 3 [p=0.009], a surrogate marker for graft and patient outcome [

25].

Six patients developed a graft-specific complication within 3 months of liver transplant (portal vein thrombosis, hepatic artery thrombosis, bile leak, biliary stricture). These patients had significantly higher circulating levels of IL-10 at 2 hours post reperfusion [1507.22(951.87-343.72pg/ml vs 462.15(343.72-718.3)pg/ml, p=0.006] but significantly lower IL-10 levels at 24 hours post operation [4.39(3.34-5.1)pg/ml vs 10.10(4.92-38.23)pg/ml, p=0.027].

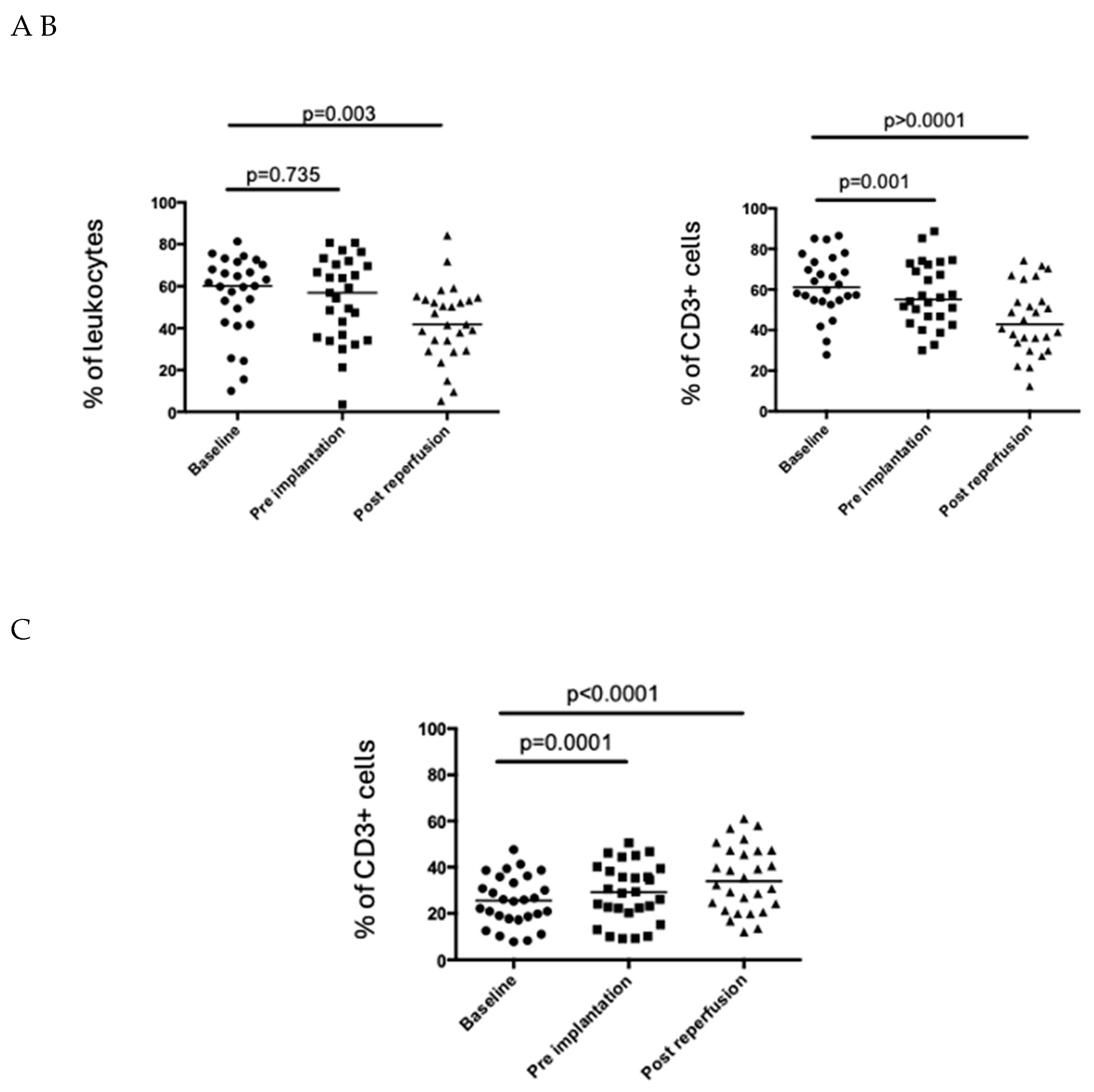

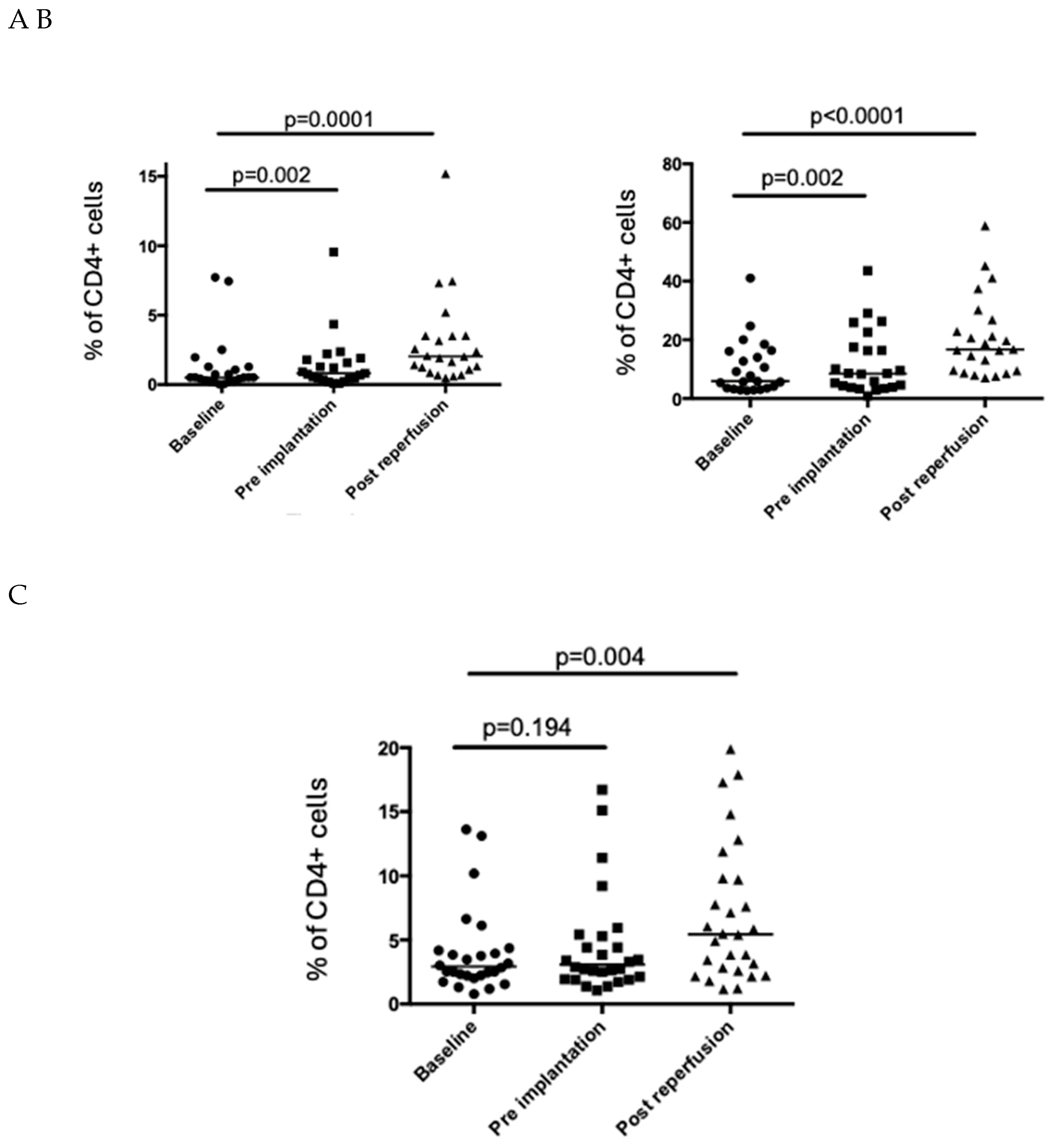

3.2. The Percentage of CD4+ T Cells in the Peripheral Circulation Falls Post Reperfusion of the Liver Graft

CD3+ T cells (as a percentage of live cells) fell significantly in the peripheral circulation following graft reperfusion (

Figure 1a). Further analysis showed that this was driven by a decrease in the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral circulation with the percentage of CD8+ T cells remaining relatively stable (

Figure 1). Intracellular (CTLA4) and cell surface markers (CD69 and HLA-DR;

Figure 2a,c) associated with T cell activation were significantly upregulated in peripheral CD4+ T cells post reperfusion.

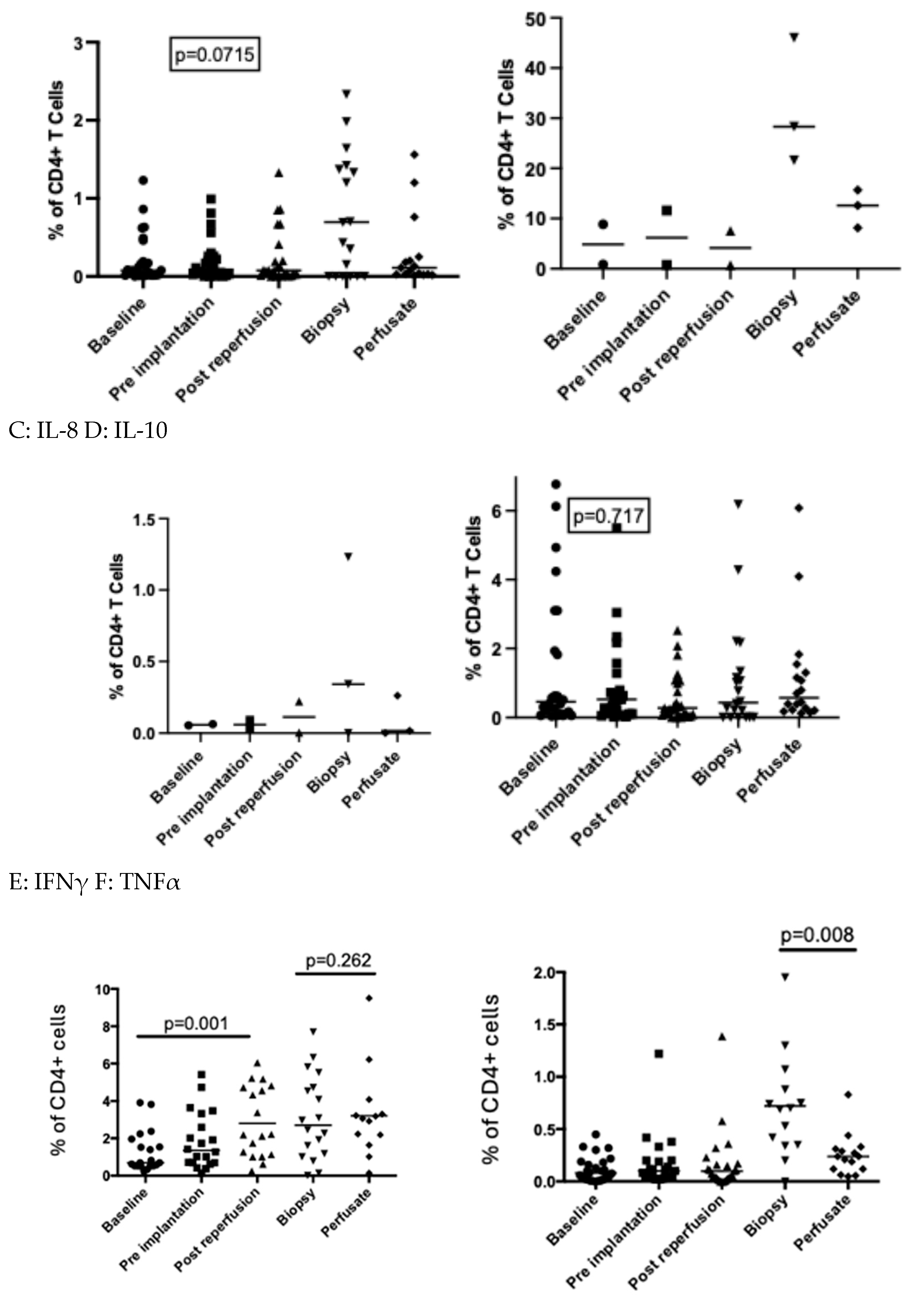

3.3. Intracellular Production of IFNγ by Circulating CD4+ T Cells Was Significantly Upregulated Following Reperfusion

There was a significantly higher proportion of circulating CD4+ T cells expressing intracellular IFNγ following reperfusion (

Figure 3f). This was not reflected in circulating plasma IFNγ levels which remained unchanged throughout the transplant period (

Table 1). The percentage of CD4+ T cells staining positive for TNFα was significantly higher in the tissue compared to the peripheral circulation. CD4+ T cell production of TNFα was significantly upregulated in the liver biopsy compared to intrahepatic CD4+ T cells isolated from the perfusate prior to graft implantation (

Figure 3g).

3.4. CD69 Was Upregulated on CD8+ T Cells But Their Cytokine Profile Did Not Change Following Reperfusion

There was a significantly higher proportion of circulating CD8+ T cells expressing CD69 following reperfusion (p<0.001, data not shown). The percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing any measure cytokine (both in the periphery and in the liver) was unchanged across the peri-transplant (data not shown).

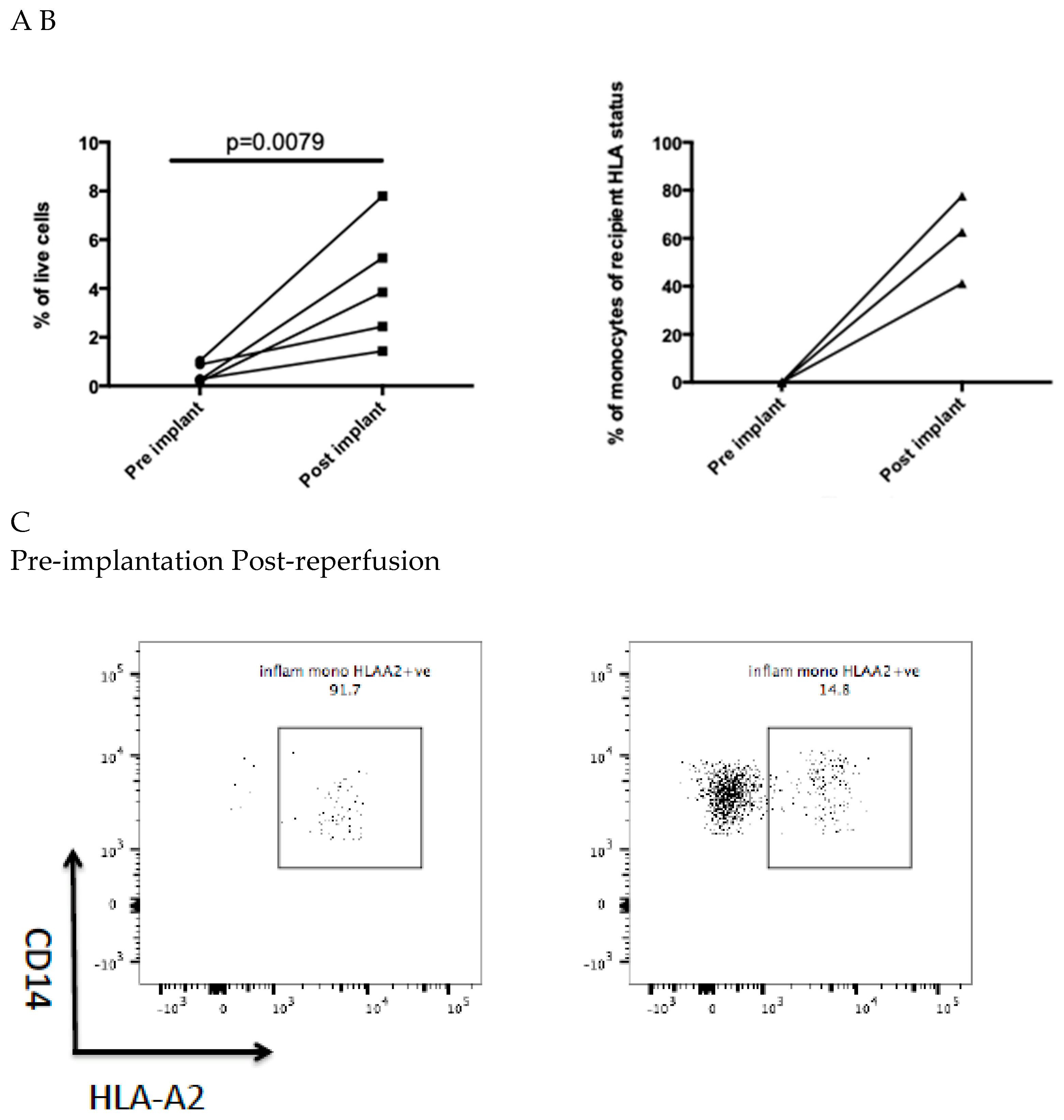

3.5. Recipient-Derived Onflammatory Monocytes are Rapidly Recruited to the Post Ischaemic Liver

In 5 patients liver biopsies were obtained pre-implantation and post reperfusion. This demonstrated a significant increase in inflammatory monocytes as a proportion of the total isolated intrahepatic leukocytes following graft reperfusion (

Figure 4a). In 3 donor-recipient pairings, there was a mismatch at the HLA-A2 or HLA-A3 allele. The majority of inflammatory monocytes in the post reperfusion liver expressed the recipient HLA allele, indicating they were of recipient origin repopulating the graft rapidly (

Figure 4b, c).

4. Discussion

Liver transplantation is increasingly utilizing marginal livers from elderly donors or organs retrieved from cardia death donors which are prone to liver ischaemia reperfusion injury. Machine perfusion may have facilitated the use of these more marginal organs [

26]. However the ability to modulate IR injury would make liver transplantation safer and enable the use of more marginal grafts. Understanding the early immune changes following liver transplant would open the door to new opportunities for immune modulation. We present the first study to track immune cell changes in the peri-operative period in patients undergoing liver transplantation and one of few studies to monitor early peri-operative cytokine changes. We have shown rapid infiltration of the post-ischaemic liver by recipient-derived inflammatory monocytes and peri-operative cytokine profiles suggesting innate immune cell activation.

In keeping with our knowledge from murine models, we found TNFα production by intrahepatic CD4+ T cells predominates in the post ischaemic liver. The role of CD4+ T cells in murine liver IR has been well documented and mice lacking CD4+ T cells are protected from liver IR injury [

6,

7,

8]. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells rapidly infiltrate the liver following the ischaemic injury [

6]. In the present study there was a reduction in CD4+ T cell numbers in the peripheral circulation shortly after graft implantation whilst CD8 + T cells were maintained. This drop in circulating CD4+ T cells suggests that they are being recruited to areas of inflammation such as the implanted graft. Unfortunately graft uptake of the circulating CD4+ T cells could be inferred but not proven as the pre-implant liver graft biopsy only yielded sufficient material for one panel and we chose to prioritise monocyte recruitment.

Early markers of peripheral CD4+ T cell activation were also upregulated during hepatic mobilisation and following reperfusion of the liver. Taken together these findings align with findings from small animal models, that CD4+ T cells are rapidly recruited to the post ischaemic liver [

6].

The most striking upregulation of cytokine production following transplant by circulating CD4+ T cells was of IFNγ. IFNγ produced by CD4+ T cells plays a key role in driving M1 macrophage response [

27] and is a potent activator of monocytes [

28]. In a study investigating renal IR injury in a mouse model, adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from IFNγ deficient mice into athymic mice did not result in IR injury suggesting that renal IR is related to IFNγ rather than other functions of CD4+ T cells [

9]. However the evidence is conflicting as IFNγ blockade in a murine model of hepatic IR injury did not protect against IR injury whilst CD40L blockade did [

13]. Small animal models have demonstrated a key role for the CD40-CD40L interactions. CD40L blockade or depletion has been shown to ameliorate IR injury in the mouse [

29] and rat [

30] liver. This confirms an interplay between CD4+ T cells and the innate immune response as a key mechanism of hepatic IR injury and is in keeping with our findings showing upregulation of IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells.

The key finding of this study was the rapid infiltration of inflammatory monocytes into the post ischaemic liver. Three donor recipient pairs had a mismatch of an HLA- A2 or HLA-A3 allele. This allowed clear demonstration that inflammatory monocytes present in the liver shortly after reperfusion were derived from the recipient and not the donor. This would suggest that strategies to modulate the inflammatory monocyte response should therefore be directed at the recipient and not the donor. There is emerging evidence from murine studies that inflammatory monocytes play a key role in hepatic IR injury [

14] and are recruited to the liver via CCR2. This is in keeping with our results which have shown increased circulating levels of CCL2 and that CCL2 levels measured at 24 hours correlated with levels of the marker of acute liver injury, AST levels at day 3. AST on day 3 has been shown to be a surrogate marker of patient and graft outcomes following liver transplant [

25] and may reflect ongoing damage to the graft. Interestingly patients who experienced a graft-related complication including those with early allograft dysfunction [

24] had higher circulating levels of IL-10 post graft reperfusion. Monocytes that are activated via TLR4 have been shown to secrete high levels of IL-10 [

31] and this therefore may reflect innate immune cell activation and damage.

The incidence of EAD in this population (54%) is higher than in the published literature which ranges from 20-40% [

32]. Although EAD has been associated with increased graft loss and poorer long term graft function this is not reflected in our results showing excellent graft and patient outcomes. This may be due to 10 patients being classified as EAD due to high transaminases in the immediate post-operative period that reduced quickly by day 1 post-op. This is reflected in our own analysis of the role of transaminases in the immediate post-operative period and correlations with graft and patient outcomes [

25] which found that high transaminases on day 3 were a better predictor of graft survival as it likely demonstrated ongoing rather than immediate graft injury.

This study has several limitations. As it examined immune cell and cytokine profiles in human patients undergoing liver transplantation, it is observational in nature and sample time points were limited. However this is also a strength of this study. There are significant differences between the immune response in mice and humans [

33] and to our knowledge, this is the first study to track immune cells in humans in the peri-transplant period. It has confirmed some similarities to rodent models of IR injury including the infiltration of inflammatory monocytes, upregulation of CCL2 and evidence of major shifts in the CD4+ T cell population. The initial aim of this study was to track CD4+ T cells and therefore although there were interesting findings regarding recruitment of inflammatory monocytes, we were not able to analyse this specific cell population for cytokine production and markers of activation. Further studies will be required to interrogate this in more detail.

In conclusion, the results from this study have shown extravasation of CD4+ T cells and their activation in liver transplantation. We have shown recruitment of recipient inflammatory monocytes to the human liver following transplantation and this presents an interesting option for early modulation of the immune response.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Callaghan, C. J.; Charman, S. C.; Muiesan, P.; Powell, J. J.; Gimson, A. E.; van der Meulen, J. H. P. Outcomes of transplantation of livers from donation after circulatory death donors in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANNUAL REPORT ON LIVER TRANSPLANTATION REPORT FOR 2022/2023 (1 APRIL 2013-31 MARCH 2023) PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2023 PRODUCED IN COLLABORATION WITH NHS ENGLAND Contents.

- Taylor, R.; Allen, E.; Richards, J. A.; Goh, M. A.; Neuberger, J.; Collett, D.; Pettigrew, G. J. Survival advantage for patients accepting the offer of a circulatory death liver transplant. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P. A.; Harvey, P. R.; Strasberg, S. M. Preservation and reperfusion injuries in liver allografts. An overview and synthesis of current studies. Transplantation 1992, 53, 957–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F.; Fuller, B.; Davidson, B. An Evaluation of Ischaemic Preconditioning as a Method of Reducing Ischaemia Reperfusion Injury in Liver Surgery and Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwacka, R. M.; Zhang, Y.; Halldorson, J.; Schlossberg, H.; Dudus, L.; Engelhardt, J. F. CD4(+) T-lymphocytes mediate ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammatory responses in mouse liver. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 100, 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moine, O.; Louis, H.; Demols, A.; Desalle, F.; Demoor, F. O.; Quertinmont, E.; Goldman, M.; Devire, J. Cold Liver Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Critically Depends on Liver T Cells and Is Improved by Donor Pretreatment With Interleukin 10 in Mice. [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, S.; Sakai, N.; Tschöp, J.; Edwards, M. J.; Lentsch, A. B.; Caldwell, C. C. Distinct contributions of CD4+ T cell subsets in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 296, G1054–G1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burne, M. J.; Daniels, F.; El Ghandour, A.; Mauiyyedi, S.; Colvin, R. B.; O’Donnell, M. P.; Rabb, H. Identification of the CD4(+) T cell as a major pathogenic factor in ischemic acute renal failure. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 1283–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Lu, L.; Zhai, Y. T cells in organ ischemia reperfusion injury. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2014, 19, 115–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Sharma, A. K.; Linden, J.; Kron, I. L.; Laubach, V. E. CD4+ T lymphocytes mediate acute pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 137, 695–702, discussion 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandoga, A.; Hanschen, M.; Kessler, J. S.; Krombach, F. CD4+ T cells contribute to postischemic liver injury in mice by interacting with sinusoidal endothelium and platelets. Hepatology 2006, 43, 306–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; Ren, F.; Busuttil, R. W.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J. W.; Zhai, Y. CD4 T cells promote tissue inflammation via CD40 signaling without de novo activation in a murine model of liver ischemia/reperfusion injury. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1537–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamboat, Z. Z. M.; Ocuin, L. M.; Balachandran, V. P.; Obaid, H.; Plitas, G.; DeMatteo, R. R. P.; Lotze, M.; Clavien, P.; Harvey, P.; Strasberg, S.; et al. Conventional DCs reduce liver ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice via IL-10 secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 559–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodero, M. P.; Licata, F.; Poupel, L.; Hamon, P.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Combadiere, C.; Boissonnas, A. In Vivo Imaging Reveals a Pioneer Wave of Monocyte Recruitment into Mouse Skin Wounds. PLoS One 2014, 9, 108212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Secco, D.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Kolaczkowska, E.; Wong, C. H. Y.; Petri, B.; Ransohoff, R. M.; Charo, I. F.; Jenne, C. N.; Kubes, P. A dynamic spectrum of monocytes arising from the in situ reprogramming of CCR2+ monocytes at a site of sterile injury. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsung, A.; Sahai, R.; Tanaka, H.; Nakao, A.; Fink, M. P.; Lotze, M. T.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Tracey, K. J.; Geller, D. A.; et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 1135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsung, A.; Klune, J. R.; Zhang, X.; Jeyabalan, G.; Cao, Z.; Peng, X.; Stolz, D. B.; Geller, D. A.; Rosengart, M. R.; Billiar, T. R. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4–dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B. H.; Wolf, J. H.; Wang, L.; Putt, M. E.; Shaked, A.; Christie, J. D.; Hancock, W. W.; Olthoff, K. M. Serum cytokine profiles associated with early allograft dysfunction in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012, 18, 166–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, M. S.; Kim, J. W.; Chung, H. S.; Park, C. S.; Lee, J.; Choi, J. H.; Hong, S. H. The impact of serum cytokines in the development of early allograft dysfunction in living donor liver transplantation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F. P.; Goswami, R.; Wright, G. P.; Fuller, B.; Davidson, B. R. Protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial of recipient remote ischaemic preconditioning in orthotopic liver transplantation (RIPCOLT trial). Transplant. Res. 2016, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F. P.; Goswami, R.; Wright, G. P.; Imber, C.; Sharma, D.; Malago, M.; Fuller, B. J.; Davidson, B. R. Remote ischaemic preconditioning in orthotopic liver transplantation (RIPCOLT trial): a pilot randomized controlled feasibility study. HPB 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossarizza, A.; Chang, H. D.; Radbruch, A.; Abrignani, S.; Addo, R.; Akdis, M.; Andrä, I.; Andreata, F.; Annunziato, F.; Arranz, E.; et al. Guidelines for the use of flow cytometry and cell sorting in immunological studies (third edition). Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 2708–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olthoff, K. M.; Kulik, L.; Samstein, B.; Kaminski, M.; Abecassis, M.; Emond, J.; Shaked, A.; Christie, J. D. Validation of a current definition of early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients and analysis of risk factors. Liver Transpl. 2010, 16, 943–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, F. P.; Bessell, P. R.; Diaz-Nieto, R.; Thomas, N.; Rolando, N.; Fuller, B.; Davidson, B. R. High serum Aspartate Transaminase (AST) levels on day 3 post liver transplantation correlates with graft and patient survival and would be a valid surrogate for outcome in liver transplantation clinical trials. Transpl. Int. 2015, 29, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, O. B.; Bodewes, S. B.; Lantinga, V. A.; Haring, M. P. D.; Thorne, A. M.; Brüggenwirth, I. M. A.; van den Berg, A. P.; de Boer, M. T.; de Jong, I. E. M.; de Kleine, R. H. J.; et al. Sequential hypothermic and normothermic machine perfusion enables safe transplantation of high-risk donor livers. Am. J. Transplant 2022, 22, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liblau, R. S.; Singer, S. M.; Mcdevitt, H. 0 Thl and Th2 CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol. Today 1995, 16, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennen, J.; Ernst, M.; Flad, H.-D. Activation of human monocytes by interleukin 2: Role of T lymphocytes. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 1991, 6, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X. Da; Ke, B.; Zhai, Y.; Amersi, F.; Gao, F.; Anselmo, D. M.; Busuttil, R. W.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J. W. CD154-CD40 T-cell costimulation pathway is required in the mechanism of hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury, and its blockade facilitates and depends on heme oxygenase-1 mediated cytoprotection. Transplantation 2002, 74, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, B.; Shen, X. Da; Gao, F.; Busuttil, R. W.; Löwenstein, P. R.; Castro, M. G.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J. W. Gene Therapy for Liver Transplantation Using Adenoviral Vectors: CD40–CD154 Blockade by Gene Transfer of CD40Ig Protects Rat Livers from Cold Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury. Mol. Ther. 2004, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Malefyt, R. W.; Abrams, J.; Bennett, B.; Figdor, C. G.; De Vries, J. E. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 174, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wei, Q.; Zheng, S.; Xu, X. Early allograft dysfunction after liver transplantation with donation after cardiac death donors. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2019, 8, 56668–56568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestas, J.; Hughes, C. C. W. Of Mice and Not Men: Differences between Mouse and Human Immunology. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).