Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

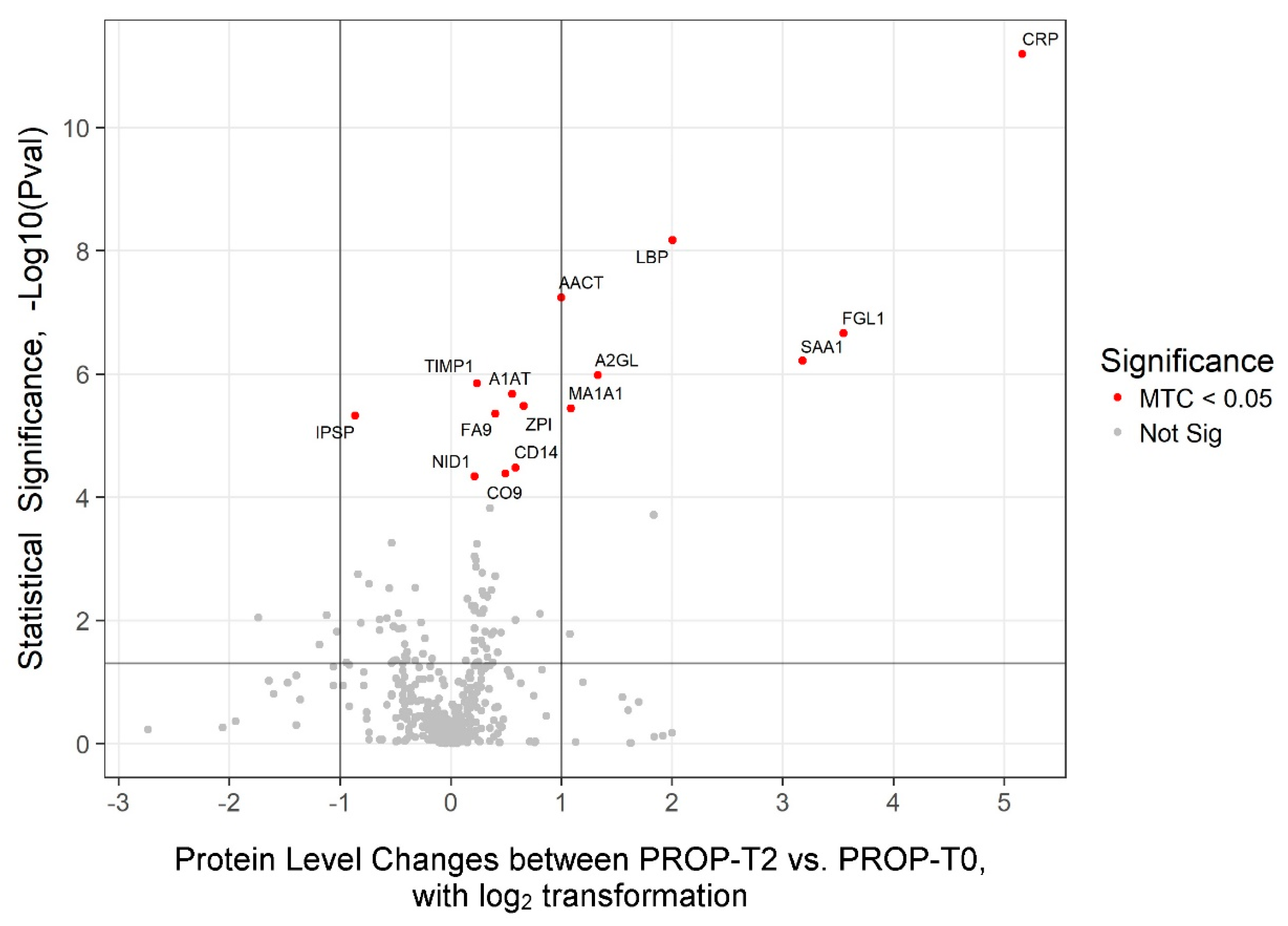

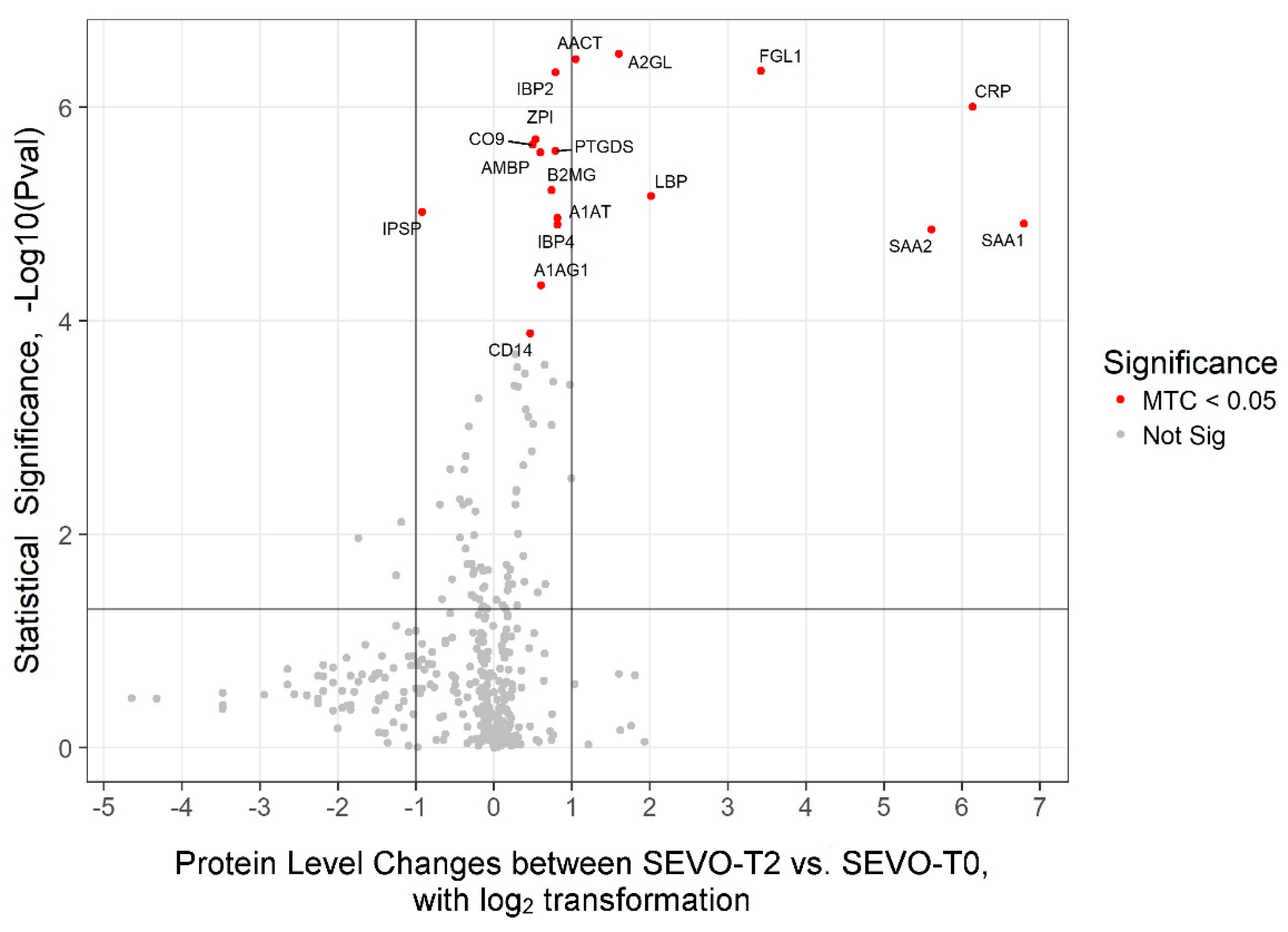

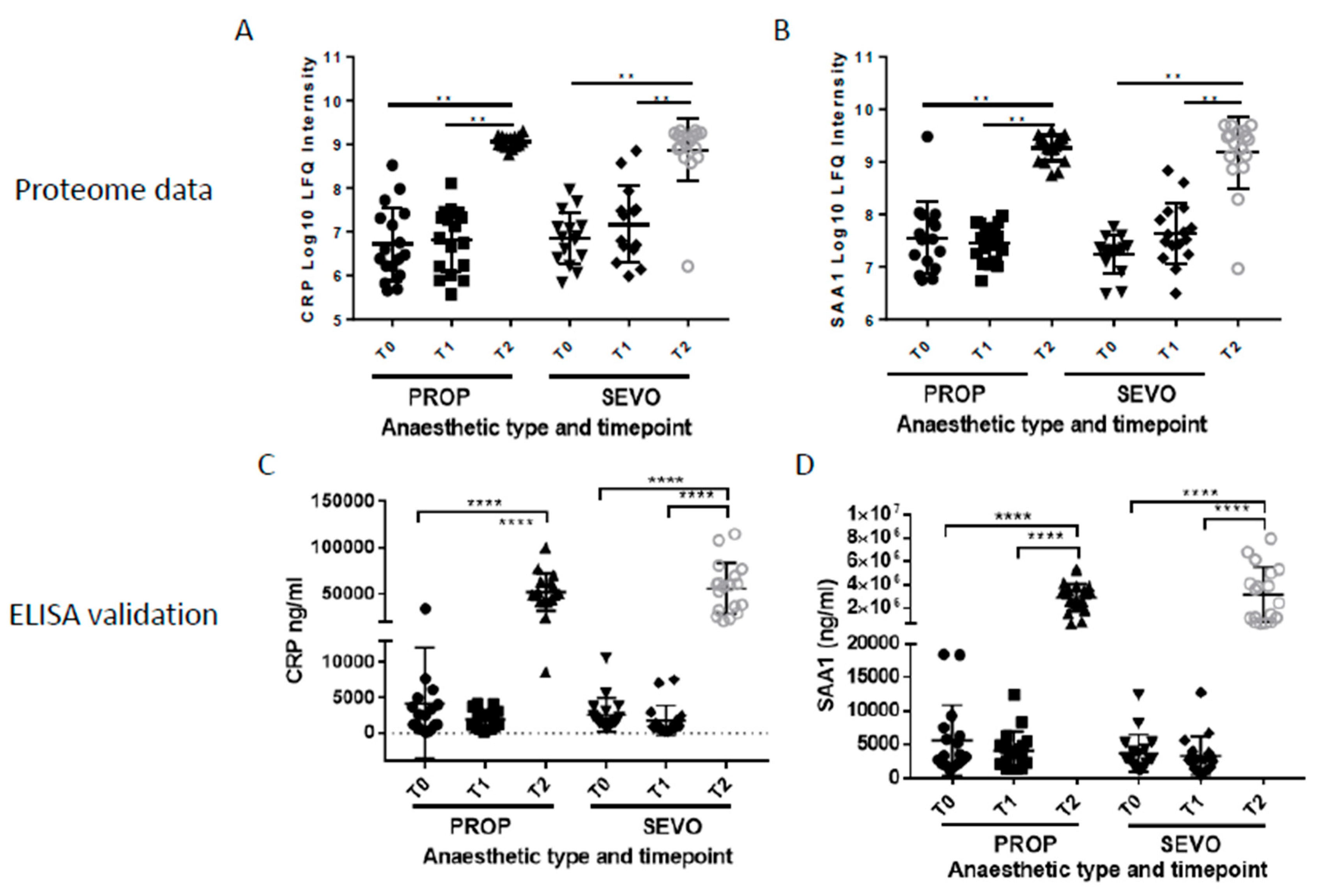

2.2. Proteomics Profiles Dependent of Anaesthetic Regimen

2.3. Proteomics Profiles Independent of Anaesthetic Regimen

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Surgery and Anaesthesia

4.3. Samples Acquisition

4.4. Sample Preparation

4.5. Mass Spectrometry

4.6. Data Analysis and Statistics

4.7. ELISA

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nepogodiev D, Martin J, Biccard B, et al (2019) Global burden of postoperative death. Lancet 393:401. [CrossRef]

- Kim M, Wall MM, Li G (2018) Risk Stratification for Major Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Intra-abdominal General Surgery Using Latent Class Analysis. Anesth Analg 126.

- Lawrence VA, Hazuda HP, Cornell JE, et al (2004) Functional independence after major abdominal surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg 199:762–772. [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer MJ, Owen HC, Torrance HDT (2015) The perioperative immune response. Curr Opin Crit Care 21.

- Giannoudis P V, Dinopoulos H, Chalidis B, Hall GM (2006) Surgical stress response. Injury 37:S3–S9. [CrossRef]

- Dobson GP (2015) Addressing the Global Burden of Trauma in Major Surgery. Front Surg 2.

- Bochicchio G V, Napolitano LM, Joshi M, et al (2002) Persistent Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Is Predictive of Nosocomial Infection in Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 53.

- Mutoh M, Takeyama K, Nishiyama N, et al (2004) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome in open versus laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Urology 64:422–425. [CrossRef]

- Hirai S (2004) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 9:365–370.

- Wigmore TJ, Mohammed K, Jhanji S (2016) Long-term Survival for Patients Undergoing Volatile versus IV Anesthesia for Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Analysis. Anesthesiology 124.

- Rollins KE, Tewari N, Ackner A, et al (2016) The impact of sarcopenia and myosteatosis on outcomes of unresectable pancreatic cancer or distal cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Nutr 35:1103–1109. [CrossRef]

- Khuri SF, Healey NA, Hossain M, et al (2005) Intraoperative regional myocardial acidosis and reduction in long-term survival after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 129:372–381. [CrossRef]

- Moola S, Lockwood C (2010) The effectiveness of strategies for the management and/or prevention of hypothermia within the adult perioperative environment: systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev 8:752–792. [CrossRef]

- Rampersad C, Patel P, Koulack J, McGregor T (2016) Back-to-back comparison of mini-open vs. laparoscopic technique for living kidney donation. Can Urol Assoc J = J l’Association des Urol du Canada 10:253–257. [CrossRef]

- Agabiti N, Stafoggia M, Davoli M, et al (2013) Thirty-day complications after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open 3:e001943. [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou I, Xanthos T, Koudouna E, et al (2009) Propofol: A review of its non-anaesthetic effects. Eur J Pharmacol 605:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Motayagheni N, Phan S, Eshraghi C, et al (2017) A Review of Anesthetic Effects on Renal Function: Potential Organ Protection. Am J Nephrol 46:380–389. [CrossRef]

- Sugasawa Y, Yamaguchi K, Kumakura S, et al (2012) Effects of sevoflurane and propofol on pulmonary inflammatory responses during lung resection. J Anesth 26:62–69. [CrossRef]

- Luo C, Yuan D, Li X, et al (2015) Propofol Attenuated Acute Kidney Injury after Orthotopic Liver Transplantation via Inhibiting Gap Junction Composed of Connexin 32. Anesthesiology 122.

- Yang S, Chou W-P, Pei L (2013) Effects of propofol on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Exp Ther Med 6:1177–1183. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Zhong D, Lei L, et al (2015) Propofol Prevents Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via Inhibiting the Oxidative Stress Pathways. Cell Physiol Biochem 37:14–26. [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi A, Marseu K, Slinger P, et al (2017) Sevoflurane Attenuates Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in a Rat Lung Transplantation Model. Ann Thorac Surg 103:1578–1586. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke GJ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Seelen MAJ, et al (2017) Propofol-based anaesthesia versus sevoflurane-based anaesthesia for living donor kidney transplantation: results of the VAPOR-1 randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 118:720–732. [CrossRef]

- Davis S, Charles PD, He L, et al (2017) Expanding Proteome Coverage with CHarge Ordered Parallel Ion aNalysis (CHOPIN) Combined with Broad Specificity Proteolysis. J Proteome Res 16:1288–1299. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Ideh RC, Gitau E, et al (2014) Discovery and Validation of Biomarkers to Guide Clinical Management of Pneumonia in African Children. Clin Infect Dis 58:1707–1715. [CrossRef]

- Kotani Y, Pruna A, Turi S, et al (2023) Propofol and survival: an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit Care 27:139. [CrossRef]

- Kampman JM, Hermanides J, Hollmann MW, et al (2024) Mortality and morbidity after total intravenous anaesthesia versus inhalational anaesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 72:. [CrossRef]

- Bang J-Y, Lee J, Oh J, et al (2016) The Influence of Propofol and Sevoflurane on Acute Kidney Injury After Colorectal Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Anesth \& Analg 123:363–370.

- Salvioli S, Monti D, Lanzarini C, et al (2013) Immune system, cell senescence, aging and longevity--inflamm-aging reappraised. Curr Pharm Des 19:1675–1679.

- Akhmedov A, Sawamura T, Chen C-H, et al (2021) Lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1): a crucial driver of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 42:1797–1807. [CrossRef]

- Colley CM, Fleck A, Goode AW, et al (1983) Early time course of the acute phase protein response in man. J Clin Pathol 36:203 LP – 207. [CrossRef]

- Rosa Neto NS, de Carvalho JF, Shoenfeld Y (2009) Screening tests for inflammatory activity: applications in rheumatology. Mod Rheumatol 19:469–477. [CrossRef]

- Labib M, Palfrey S, Paniagua E, Callender R (1997) The Postoperative Inflammatory Response to Injury following Laparoscopic Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy. Ann Clin Biochem 34:543–545. [CrossRef]

- Neumaier M, Scherer MA (2008) C-reactive protein levels for early detection of postoperative infection after fracture surgery in 787 patients. Acta Orthop 79:428–432. [CrossRef]

- Sack GH (2020) Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Proteins BT - Vertebrate and Invertebrate Respiratory Proteins, Lipoproteins and other Body Fluid Proteins. In: Hoeger U, Harris JR (eds). Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 421–436.

- Baranova IN, Souza ACP, Bocharov A V, et al (2017) Human SR-BII mediates SAA uptake and contributes to SAA pro-inflammatory signaling in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 12:e0175824.

- Yamada T, Okuda Y, Takasugi K, et al (2001) Relative serum amyloid A (SAA) values: the influence of SAA1 genotypes and corticosteroid treatment in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 60:124 LP – 127. [CrossRef]

- Eklund KK, Niemi K, Kovanen PT (2012) Immune functions of serum amyloid A. Crit Rev Immunol 32:335–348. [CrossRef]

- Linke RP, Meinel A, Chalcroft JP, Urieli-Shoval S (2017) Serum amyloid A (SAA) treatment enhances the recovery of aggravated polymicrobial sepsis in mice, whereas blocking SAA’s invariant peptide results in early death. Amyloid 24:149–150. [CrossRef]

- Wierdak M, Pisarska M, Kuśnierz-Cabala B, et al (2018) Serum Amyloid A as an Early Marker of Infectious Complications after Laparoscopic Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 19:622–628. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Ma C, Xing J, et al (2019) Serum amyloid a protein as a potential biomarker in predicting acute onset and association with in-hospital death in acute aortic dissection. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19:282. [CrossRef]

- Schumann RR (1992) Function of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) and CD14, the receptor for LPS/LBP complexes: a short review. Res Immunol 143:11–15. [CrossRef]

- Ding P-H, Jin LJ (2014) The role of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in innate immunity: a revisit and its relevance to oral/periodontal health. J Periodontal Res 49:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Prucha M, Herold I, Zazula R, et al (2003) Significance of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (an acute phase protein) in monitoring critically ill patients. Crit Care 7:R154. [CrossRef]

- Brănescu C, Şerban D, Şavlovschi C, et al (2012) Lipopolysaccharide binding protein (L.B.P.)--an inflammatory marker of prognosis in the acute appendicitis. J Med Life 5:342–347.

- Kudlova M, Kunes P, Kolackova M, et al (2007) Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein and sCD14 are Not Produced as Acute Phase Proteins in Cardiac Surgery. Mediators Inflamm 2007:72356. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Ukomadu C (2008) Fibrinogen-like protein 1, a hepatocyte derived protein is an acute phase reactant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 365:729–734. [CrossRef]

- Rijken DC, Dirkx SPG, Luider TM, Leebeek FWG (2006) Hepatocyte-derived fibrinogen-related protein-1 is associated with the fibrin matrix of a plasma clot. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 350:191–194. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Yang J, Zhang S, et al (2019) Serological cytokine profiles of cardiac rejection and lung infection after heart transplantation in rats. J Cardiothorac Surg 14:26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Huang R, Tang Q, et al (2018) Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein-1 is up-regulated in colorectal cancer and is a tumor promoter. Onco Targets Ther 11:2745–2752. [CrossRef]

- Shirai R, Hirano F, Ohkura N, et al (2009) Up-regulation of the expression of leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein in hepatocytes by the mediators of acute-phase response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382:776–779. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Zhou J, Xie Z, et al (2019) Mechanical strain promotes skin fibrosis through LRG-1 induction mediated by ELK1 and ERK signalling. Commun Biol 2:359. [CrossRef]

- Banfi C, Parolari A, Brioschi M, et al (2010) Proteomic Analysis of Plasma from Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Reveals a Protease/Antiprotease Imbalance in Favor of the Serpin α1-Antichymotrypsin. J Proteome Res 9:2347–2357. [CrossRef]

- Hack CE, Abbink JJ, Nuijens JH (1990) [Serine protease inhibitors (serpins); regulators of coagulation and inflammation reactions with therapeutic potential]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 134:1035–1039.

- Dai E, Guan H, Liu L, et al (2003) Serp-1, a Viral Anti-inflammatory Serpin, Regulates Cellular Serine Proteinase and Serpin Responses to Vascular Injury *. J Biol Chem 278:18563–18572. [CrossRef]

- Bergin DA, Hurley K, McElvaney NG, Reeves EP (2012) Alpha-1 Antitrypsin: A Potent Anti-Inflammatory and Potential Novel Therapeutic Agent. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 60:81–97. [CrossRef]

- Radovani B, Gudelj I (2022) N-Glycosylation and Inflammation; the Not-So-Sweet Relation.

| PROP n=19 |

SEVO n=17 |

P |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age y | 49.6 (13.2) | 33.8 (10.6) | 0.297 |

| Male n (%) | 10 (53%) | 9 (53%) | >0.999 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 25.9 (3.6) | 27.4 (3.5) | 0.233 |

| ASA I/II | 15/4 | 11/6 | 0.463 |

| mGFR ml/kg | 125 (98-140) | 107 (97-132) | 0.364 |

| Smoking n (%) | 7 (37%) | 5 (30%) | 0.728 |

| CCI Cardiovascular comorbidity n (%) |

1 (0-2) 1 (5%) |

1 (0-1) 5 (29%) |

0.620 0.080 |

| MAP baseline mmHg | 93 (90-96) | 94 (85-104) | 0.863 |

| Perioperative data | |||

| Duration procedure min | 230 (28.4) | 245 (42.5) | 0.196 |

| Amount of fluid ml/kg BW | 61.5 (10.0) | 60.2 (11.7) | 0.730 |

| BIS | 39 (7) | 45 (6) | 0.012 |

| Blood sample clip renal artery | |||

| pH | 7.41 (0.04) | 7.39 (0.04) | 0.146 |

| PaO2 kPa | 20.3 (4.9) | 20.4 (4.7) | 0.955 |

| Hemoglobin mmol/l | 7.2 (0.9) | 7.3 (1.0) | 0.725 |

| Lactate mmol/l | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.7) | 0.044 |

| Anaesthetics/analgesics | |||

| Propofol Cet (ug/ml) | 3.3 (0.5) | - | - |

| Sevoflurane EtC | - | 1.53 (0.14) | - |

| Remifentanil Cet (ng/ml) | 3.2 (0.86) | 2.6 (0.63) | 0.020 |

| Vasoactive medication | |||

| Ephedrine n (%) | 13 (68%) | 17 (100%) | 0.020 |

| Dose mg | 15 (10-20) | 15 (10-30) | 0.207 |

| Phenylephrine n (%) | 2 (11%) | 1 (6%) | >0.999 |

| Dose ug | 150 (100-200) | 100 | n too small |

| Other medication | |||

| Piritramide intraoperative mg | 8 (7.0-9.0) | 7.5 (7.0-8.5) | 0.901 |

| Piritramide postoperative mg | 12 (10.0-16.0) | 11 (8.5-19.0) | 0.688 |

| Ondansetron intraoperative n(%) | 2 (11%) | 8 (47%) | 0.025 |

| Ondansetron PACU n (%) | 8 (42%) | 3 (18%) | 0.156 |

| Dexamethasone n (%) | 2 (11%) | 3 (18%) | 0.650 |

| Droperidol n (%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (6%) | >0.999 |

| Postoperative complications | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0.487 |

| LOH d | 5 (5-7) | 5 (5-7,5) | 0.912 |

| UniProt ID | Gene | Protein | PROP (T2-vs-T0) | SEVO (T2-vs-T0) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTC level | P-value | Fold change | MTC level | P-value | Fold change | |||

| P02763 | A1AG1 | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 | - | - | - | P<0.05 | 4,60E-05 | 1,52 |

| P01009 | A1AT | Alpha-1-antitrypsin | P<0.01 | 2,10E-06 | 1,47 | P<0.01 | 1,10E-05 | 1,76 |

| P02750 | A2GL | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | P<0.01 | 1,00E-06 | 2,51 | P<0.01 | 3,20E-07 | 3,04 |

| P01011 | AACT | Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin | P<0.01 | 5,70E-08 | 2 | P<0.01 | 3,50E-07 | 2,07 |

| P02760 | AMBP | Protein AMBP | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 2,60E-06 | 1,51 |

| P61769 | B2MG | Beta-2-microglobulin | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 6,00E-06 | 1,67 |

| P08571 | CD14 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | P<0.05 | 3,30E-05 | 1,5 | P<0.05 | 1,30E-04 | 1,38 |

| P02748 | CO9 | Complement component C9 | P<0.05 | 4,10E-05 | 1,41 | P<0.01 | 2,20E-06 | 1,41 |

| P02741 | CRP | C-reactive protein | P<0.01 | 6,40E-12 | 35,83 | P<0.01 | 9,90E-07 | 70,09 |

| P00740 | FA9 | Coagulation factor IX | P<0.01 | 4,40E-06 | 1,32 | - | - | - |

| Q08830 | FGL1 | Fibrinogen-like protein 1 | P<0.01 | 2,20E-07 | 11,69 | P<0.01 | 4,50E-07 | 10,69 |

| P18065 | IBP2 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 4,70E-07 | 1,73 |

| P22692 | IBP4 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 4 | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 1,30E-05 | 1,76 |

| P05154 | IPSP | Plasma serine protease inhibitor | P<0.01 | 4,80E-06 | -1,82 | P<0.01 | 9,50E-06 | -1,89 |

| P18428 | LBP | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | P<0.01 | 6,60E-09 | 4,01 | P<0.01 | 6,80E-06 | 4,04 |

| P33908 | MAN1A1 | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,2-alpha-mannosidase IA |

P<0.01 | 3,60E-06 | 2,12 | - | - | - |

| P14543 | NID1 | Nidogen-1 | P<0.05 | 4,60E-05 | 1,16 | - | - | - |

| P41222 | PTGDS | Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 2,60E-06 | 1,73 |

| P0DJI8 | SAA1 | Serum amyloid A-1 protein | P<0.01 | 6,10E-07 | 9,05 | P<0.01 | 1,20E-05 | 110,69 |

| P0DJI9 | SAA2 | Serum amyloid A-2 protein | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 1,40E-05 | 48,67 |

| P01033 | TIMP1 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | P<0.01 | 1,40E-06 | 1,18 | - | - | - |

| Q9UK55 | ZPI | Protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor | P<0.01 | 3,30E-06 | 1,58 | P<0.01 | 2,00E-06 | 1,45 |

| ALL T2-T0 | ALL T2-T1 | ALL T1-T0 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniPro ID |

Gene | Protein | MTC | P-value | Fold change |

Direction | MTC | P-value | Fold change |

Direction | MTC | P-value | Fold change |

Direction |

| P02741 | CRP | C-reactive protein | P<0.01 | 2,7E-16 | 46,42 | UP | P<0.01 | 2,4E-14 | 22,61 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P01011 | AACT | Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin | P<0.01 | 3,4E-14 | 2,03 | UP | P<0.01 | 2,9E-13 | 1,93 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P18428 | LBP | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | P<0.01 | 1,5E-13 | 4,04 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,8E-09 | 3,73 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| Q08830 | FGL1 | Fibrinogen-like protein 1 | P<0.01 | 1,6E-13 | 11,76 | UP | P<0.01 | 6,8E-11 | 8,48 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P02750 | A2GL | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | P<0.01 | 7,2E-13 | 2,74 | UP | P<0.01 | 7,9E-12 | 2,63 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| Q9UK55 | ZPI | Protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor | P<0.01 | 3,1E-11 | 1,52 | UP | P<0.01 | 3,5E-08 | 1,41 | UP | - | 4,3E-02 | 1,08 | UP |

| P0DJI8 | SAA1 | Serum amyloid A-1 protein | P<0.01 | 5,7E-11 | 17,69 | UP | P<0.01 | 2,2E-11 | 32,42 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P05154 | IPSP | Plasma serine protease inhibitor | P<0.01 | 1,0E-10 | 1,85 | DOWN | P<0.01 | 8,1E-09 | 1,69 | DOWN | - | - | - | - |

| P01009 | A1AT | Alpha-1-antitrypsin | P<0.01 | 3,2E-10 | 1,61 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,2E-11 | 2,09 | UP | P<0.05 | 8,8E-05 | 1,3 | DOWN |

| P02748 | CO9 | Complement component C9 | P<0.01 | 4,2E-10 | 1,41 | UP | P<0.01 | 3,1E-07 | 1,25 | UP | - | 9,3E-03 | 1,13 | UP |

| P00740 | FA9 | Coagulation factor XI | P<0.01 | 6,7E-09 | 1,32 | UP | - | 1,5E-02 | 1,1 | UP | P<0.05 | 2,8E-05 | 1,2 | UP |

| P0DJI9 | SAA2 | Serum amyloid A-2 protein | P<0.01 | 9,1E-09 | 4,58 | UP | P<0.01 | 2,7E-09 | 16,47 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P33908 | MAN1A1 | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,2-alhpa-mannosidase IA | P<0.01 | 1,0E-08 | 1,93 | UP | P<0.05 | 6,2E-05 | 1,63 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P08571 | CD14 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | P<0.01 | 1,1E-08 | 1,44 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,2E-06 | 1,38 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P18065 | IBP2 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 | P<0.01 | 1,2E-08 | 1,38 | UP | P<0.01 | 2,9E-07 | 1,47 | UP | - | 2,6E-02 | 1,06 | DOWN |

| P15169 | CBPN | Carboxy peptidase N catalytic chain | P<0.01 | 1,9E-06 | 1,25 | UP | - | 8,0E-04 | 1,22 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P02760 | AMBP | Protein AMBP | P<0.01 | 2,9E-06 | 1,4 | UP | P<0.05 | 2,6E-05 | 1,22 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P01033 | TIMP1 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | P<0.01 | 3,2E-06 | 1,23 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,4E-05 | 1,24 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P36955 | PEDF | Pigment epithelium-derived factor | P<0.01 | 3,3E-06 | 1,27 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,1E-06 | 1,21 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P05019 | IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor I | P<0.01 | 8,5E-06 | 1,25 | UP | - | - | - | - | - | 1,3E-02 | 1,14 | UP |

| P04004 | VTNC | Vitronectin | P<0.01 | 1,4E-05 | 1,22 | UP | - | - | - | - | - | 2,0E-02 | 1,13 | UP |

| P49747 | COMP | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | P<0.01 | 1,5E-05 | 1,47 | DOWN | - | 1,6E-02 | 1,2 | DOWN | - | 7,1E-04 | 1,2 | DOWN |

| P00748 | FA12 | Coagulation factor XII | P<0.05 | 2,6E-05 | 1,32 | DOWN | - | 1,5E-03 | 1,27 | DOWN | - | - | - | - |

| P02787 | TRFE | Serotransferrin | P<0.05 | 3,2E-05 | 1,54 | DOWN | - | - | - | - | - | 7,0E-03 | 1,3 | DOWN |

| P02763 | A1AG1 | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 | P<0.05 | 3,4E-05 | 1,38 | UP | P<0.01 | 3,3E-10 | 1,7 | UP | - | 2,6E-02 | 1,23 | DOWN |

| Q86UD1 | OAF | Out at first protein homolog | P<0.05 | 4,1E-05 | 1,87 | UP | P<0.01 | 8,1E-06 | 1,67 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P02649 | APOE | Apolipoprotein E | P<0.05 | 8.0E-05 | 1,25 | UP | - | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 6,5E-06 | 1,31 | UP |

| P22792 | CPN2 | Carboxy peptidase N subunit 2 | P<0.05 | 8,3E-05 | 1,16 | UP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Q92820 | GGH | Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase | - | 1,5E-04 | 1,15 | UP | - | - | - | - | P<0.05 | 9,0E-05 | 1,15 | UP |

| P14543 | NID1 | Nidogen-1 | - | 2,5E-04 | 1,05 | UP | P<0.01 | 3,2E-10 | 1,08 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P05160 | F13B | Coagulation factor XIII B chain | - | 1,9E-03 | 1,39 | DOWN | P<0.05 | 7,9E-06 | 1,59 | DOWN | - | - | - | - |

| P22352 | GPX3 | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | - | 2,8E-03 | 1,2 | UP | - | - | - | - | P<0.01 | 6,5E-06 | 1,3 | UP |

| Q06033 | ITIH3 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | - | 1,2E-02 | 1,17 | UP | P<0.01 | 1,9E-07 | 1,19 | UP | - | - | - | - |

| P22105 | TENX | Tenascin-X | - | 4,0E-02 | 1,14 | UP | - | - | - | - | P<0.05 | 2,7E-05 | 1,35 | UP |

| O75636 | FCN3 | Ficolin-3 | - | - | - | - | - | 4,2E-03 | 1,19 | DOWN | P<0.05 | 5,0E-05 | 1,26 | UP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).