1. Introduction

Organ shortage is a global challenge for transplantation progress. To address this problem, organs from suboptimal donors, such as circulatory death (DCD), are increasingly used, driven by the integration of innovative technologies such as normothermic abdominal regional perfusion (NRP) and ex-situ mechanical perfusion (MP), leading to improved transplant outcomes and reduced post-transplant complications [

1,

2]. There is a fervent discussion about what is the optimal ex-situ perfusion system [

2]. Regardless of the adopted MP technique, one goal of MP is to assess liver viability before transplantation, which can simultaneously reduce the non-use of potentially transplantable livers and avoid transplanting poorly functioning grafts. The prerequisite for an accurate viability assessment is the availability of reliable biomarkers of liver damage and function, ideally employed interchangeably during any MP technique, including NRP [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

In DCD grafts, organ damage arising from warm and cold ischemia contributes to ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), which is characterized by oxidative stress, depletion of adenosine triphosphate and mitochondrial dysfunction [

8]. Early allograft dysfunction (EAD) is a frequent complication during the first postoperative week after orthotopic LT and is considered a consequence of IRI. The perfusate level of mitochondrial flavin mononucleotide (FMN) has been recently identified as a potential biomarker of graft damage and function during HOPE [

9,

10,

11], whereas other parameters of graft function, including lactate clearance, glucose metabolism, and pH maintenance, represent the backbone of liver viability assessment during NMP [

12].

IRI-induced hepatocyte damage leads to the release of various cytosolic enzymes. ARG-1 is an enzyme primarily expressed in the liver, where it plays a crucial role in ammonia detoxification by catalyzing the final step of the urea cycle, converting arginine into ornithine and urea [

13]. In liver transplantation, reduced ARG-1 levels increase L-arginine availability for NOS, raising NO production. Excess NO can form peroxynitrite with superoxide, leading to oxidative stress and tissue damage, which exacerbates IRI and contributes to EAD [

14,

15].

Moreover, beyond its role in tissue damage from depletion due to IRI, ARG-1 ‒ with its notably short half-life [

16] ‒ may serve as a timely and reliable biomarker of graft function during NRP, MP, and post-transplantation. In addition, a more rapid decline of this marker may better indicate the liver’s recovery from injury, providing added value compared to the usually employed transaminases [

17].

While many studies have focused on indicators of mitochondrial dysfunction, limited knowledge exists regarding the use of additional liver parenchymal enzymes with more early circulation elevation compared to transaminases for assessing liver viability [

16,

18]. To achieve a more precise assessment of liver damage and recovery, we simultaneously analyzed a range of biomarkers associated with oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, and tissue regeneration.

In this study, we highlighted the better performance and association of ARG-1 with patient EAD outcomes in DCD grafts undergoing NRP followed by either NMP or D-HOPE compared to other different biomarkers. We also underlined the limitations of FMN fluorescence as a mitochondrial damage biomarker, especially its dependency on perfusate or serum composition, underscoring its convenience but limited universal applicability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was part of the DCDNet Study (Clinicaltrial.gov #NCT04744389), a pilot, randomized, prospective trial with the primary objective of comparing the impact of D-HOPE versus NMP on the outcome of LT patients receiving DCD liver grafts after normothermic regional perfusion NRP. The main focus of this study was to identify, through an exploratory biomarker analysis, the potential differences in DCD grafts preserved using NRP followed by NMP versus NRP followed by D-HOPE.

All research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul and was approved by the local ethical committee (Comitato Etico Area Vasta Nord-Ovest, CEAVNO approval#17848).

Livers from both controlled (cDCD) and uncontrolled (uDCD) were included in the study. Briefly, cDCDs are patients with an extremely poor medical prognosis, most frequently due to severe brain injury, in which cardiac death after the withdrawal of intensive care treatment, is anticipated. uDCDs are patients who experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, undergo onsite cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and are transferred to the hospital with mechanical chest compression (LUCAS-Jolife AB/Physio-Control, Lund, Sweden) [

19]. These patients are considered potential donors once resuscitation proves unsuccessful or irreversible brain damage is diagnosed. Donor selection details are reported in the

Supplementary Materials.

2.2. Normothermic Regional Perfusion, Ex-Situ Machine Perfusion, and Outcome

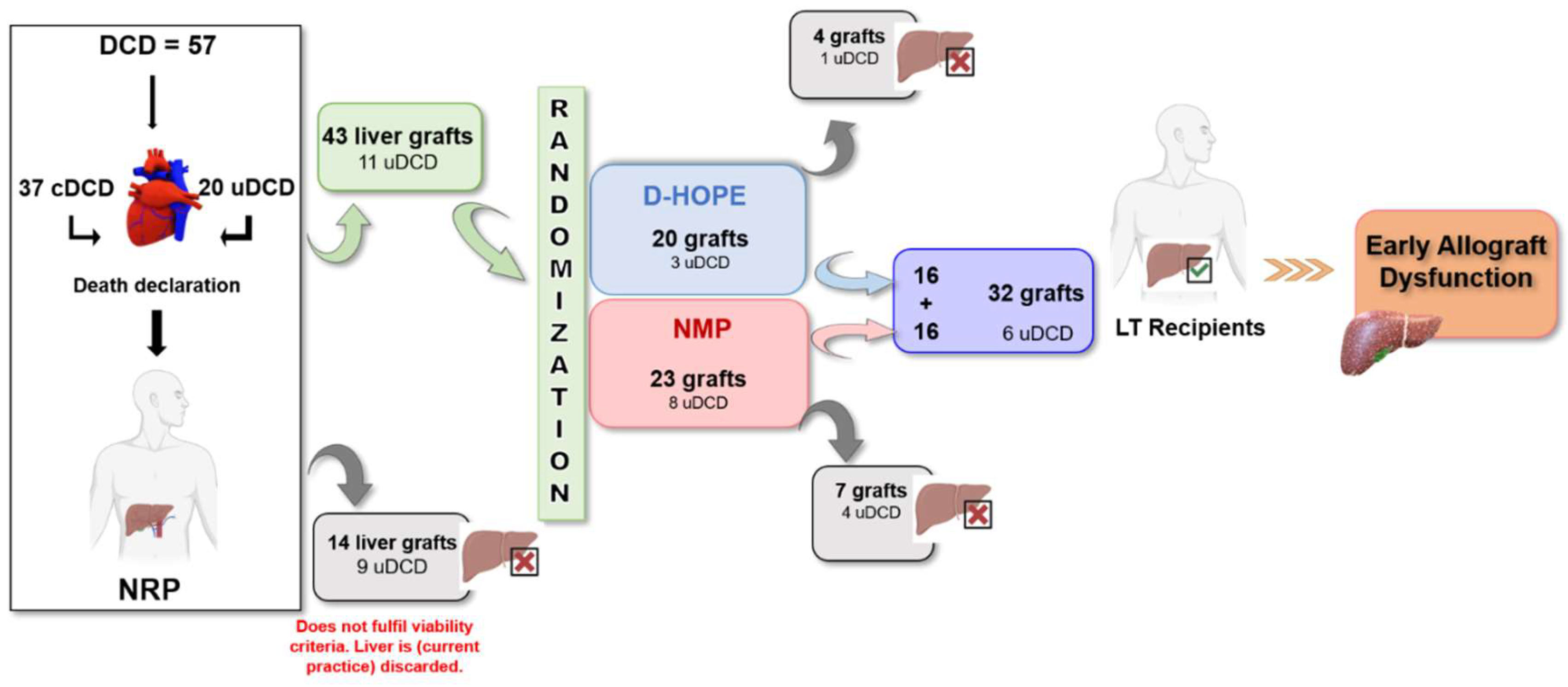

The flowchart of the study is shown in

Figure 1. Details of NRP, MP, and transplantation are specified in the

Supplementary Materials, as well as key definitions and outcome measures.

2.3. Sample Collection and Analysis

Blood samples were collected at 0, 2, and 4 h of NRP, whereas tissue specimens were collected at the end of NRP.

During NRP and end-ischemic MP, a routine biochemical panel including aspartate-aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), glucose, lactate, creatinine, pH, HCO3-, pO2, pCO2, and electrolytes (Na, Cl, K, and Ca) was assessed every hour.

Blood samples were collected for study-specific analytes in EDTA at designated times: i) at the initiation of NRP (T0), 2 h after initiation (T2h), and 4 h after initiation (T4h); ii) at the beginning, midpoint, and conclusion of the end-ischemic MP procedure; iii) in recipients: before reperfusion, immediately post-reperfusion, one day after LT, and one week after LT.

Liver biopsy was performed using a 14G True-Cut needle at the NRP end and stored in Allprotect® Tissue Reagent (Qiagen, S.p.A, Milano, Italy) at -80°C until use. All samples analyzed were performed in a blinded manner

2.4. Tissue Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) of Autophagic Biomarker Expression

2.5. Soluble Biomarker Assays

A panel of soluble biomarkers relevant to inflammation, injury, and regeneration hepatic profiles was evaluated using custom-designed immunoassays based on Luminex xMAP Technology (MILLIPLEX, EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) as previously described [

19]. Data acquisition was performed using MAGPIX Luminex xMAP technology for Median Fluorescence Intensity and analyzed using Belysa Immunoassay Curve Fitting software (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), with a 5-parameter model.

The list of the measured analytes, their ranges, and sensitivities are provided in

Table S1.

2.6. Quantification of Lipid Peroxidation Products, FMN, NADH, Fumarate and Succinate

The levels of lipid peroxidation products were determined by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). TBARS levels were measured in plasma and perfusate samples using a colorimetric method by measuring the OD values at 530-540 nm, according to the manufacturer’s specifications (E-BC-K298-M, Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). The plasma TBARS values in a population of 20 healthy subjects were 2.5 ± 0.15 µM.

The levels of both FMN and NADH (NADPH) in the plasma and perfusate samples were determined by fluorescence spectroscopy using a microplate fluorescence reader (Tecan Infinite

® 200 PRO, Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland). The FMN fluorescence was read at 450 nm excitation and 550 nm emission, while the fluorescence of NADH was read at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission wavelengths. The FMN spectra were calibrated using the FMN standard [

19]. The FMN levels of the NMP and D-HOPE perfusion fluids before the start of perfusion were 1410 ± 104 ng/mL and 12 ± 5 ng/mL, respectively.

Fumarate and succinate were analyzed by colorimetric assays (Sigma-Aldrich, MAK060 and MAK184 respectively), according to the manufacturer’s specifications [

19].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were presented as counts (frequencies). A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to determine the level of normality and the cut-off level for significance was set as P < 0.05 for all the analyses. A Chi-square or Fisher exact test was performed for categorical variables, whereas an independent samples t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were employed for normal and non-normal distribution, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to explore correlations between the variables. A mixed design (3 × 2) 2-way ANOVA was conducted to identify the main effects of NRP, end ischemic MP, and LT on dependent variables across the three-time points, between the groups, and the interaction between group and time. A Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction was performed within each group across various time points.

Due to the small sample size a post-hoc power analysis was conducted to determine whether we had a large enough sample size to be able to detect differences between EAD (n = 9) and non-EAD group (n = 23). The observed effect size for the difference in ARG-1 levels between these groups at the end of MP resulted in a calculated power > 0.80, indicating that the sample size was sufficient to detect a statistically significant difference at the 0.05 significance level.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of ARG-1 at the end of MPs. The data were analyzed using SPSS 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

Among the 57 DCD donors undergoing NRP, 37 were controlled DCD (cDCD), and 20 were uncontrolled DCD (uDCD) (

Figure 1). Fourteen liver grafts were discarded during NRP (five cDCD and nine uDCD), whereas forty-three (32 cDCD and 11 uDCD) were considered eligible for transplant and were randomized to NMP (n = 23) or D-HOPE (n = 20). Four livers (cDCD, n = 3; uDCD, n = 1) were discarded during D-HOPE, whereas seven (cDCD, n = 3; uDCD, n = 4) were discarded during NMP. After selection, thirty-two liver grafts were successfully transplanted, of which twenty-six (81.2%) were from cDCD and six (18.7%) from uDCD (

Figure 1).

Baseline donor and recipient characteristics, and clinical outcomes are summarized in

Table 1. The dynamic changes in traditional biomarkers including AST, ALT and lactate levels during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and until a week post-transplant are shown in

Figure S1.

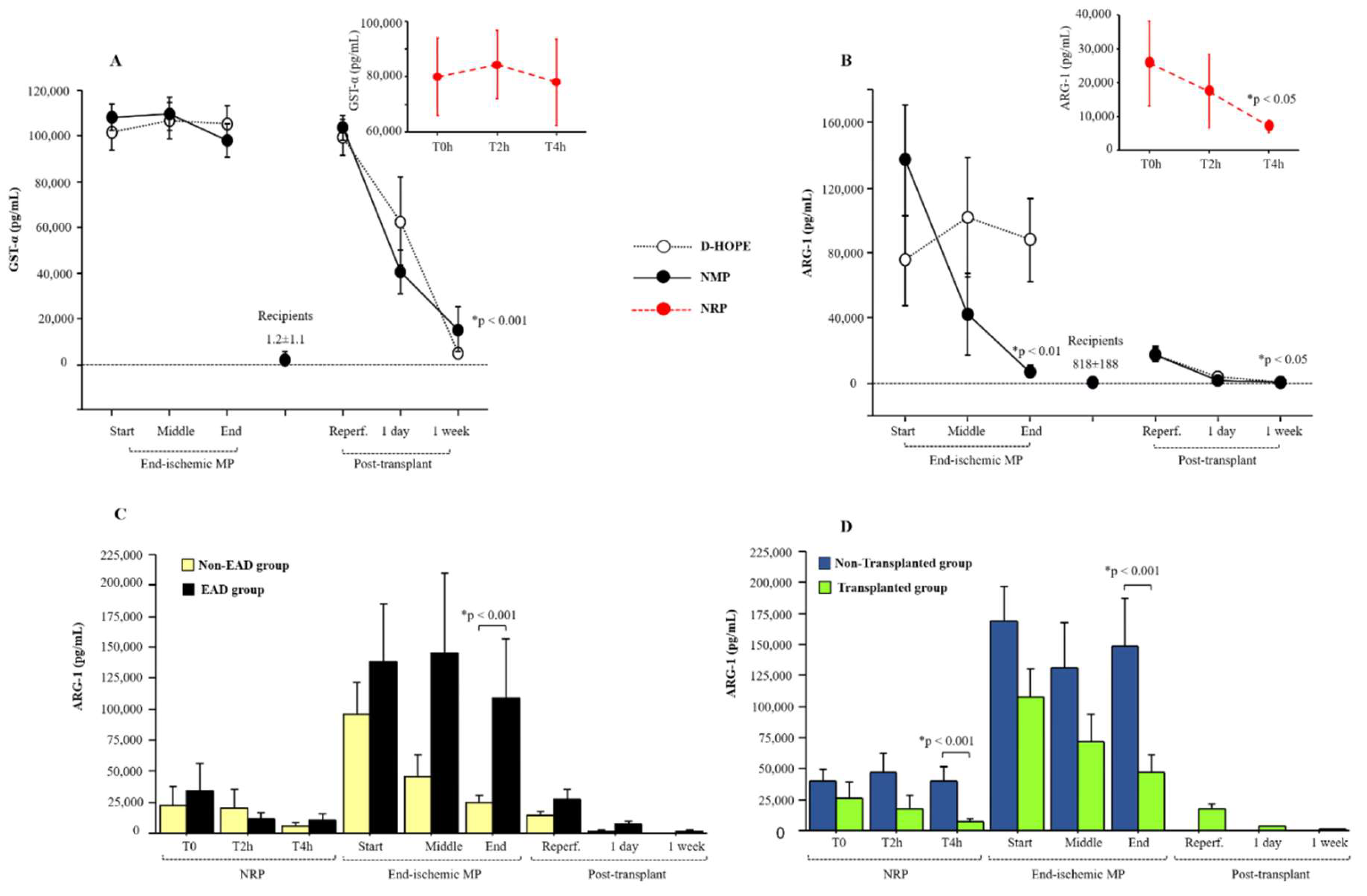

3.1. Performance of Early-Releasing Enzymes (ARG-1 and GST-α) as Biomarkers During Machine Perfusion and Post-Transplantation

Among the parenchymal biomarkers, we focused on the performance of early-releasing enzymes, such as ARG-1 and GST-α, compared to that of transaminases. The levels of GST-α remained very high during both NRP and ex-situ machine perfusion (

Figure 2A). Due to its high half-life, GST-α levels dropped to normal levels only one week after LT (

Figure 2A).

Compared to the baseline levels of recipients (818±188 pg/mL), ARG1 plasma levels were elevated at the start of NRP and dropped at the end of perfusion (

Figure 2B). We observed that the levels of ARG-1 decreased in NMP but tended to remain relatively high during D-HOPE, as depicted in

Figure 2B. At the end of ex-situ MP, ARG-1 perfusate levels correlated with lactate (r = 0.574, p < 0.001), ALT (r = 0.427, p < 0.05), fumarate (r = 0.704, p < 0.001), and succinate (r = 0.781, p < 0.001) levels. In the recipients, ARG-1 plasma levels normalized one day after transplantation (

Figure 2B).

3.2. Clinical Outcome

The LT operations were uneventful. No cases of primary nonfunction, vascular complications or ischemic cholangiopathy were reported. There were four cases of biliary leakage from the T-tube insertion which were treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and pancreatography. Twelve patients presented with postreperfusion syndrome and 4 with acute kidney injury. There were 9 cases of EAD (28.1%). No major differences were found in terms of post-operative hospitalization or complications based on MP perfusion type. The detailed post-operative outcome data are reported in Table 1.

Importantly, ARG-1 levels in the perfusate during and after ex-situ graft perfusion were higher in recipients who developed EAD than in those who did not (

Figure 2C). In the EAD group, ARG-1 plasma levels were higher also at one-day post-transplant compared to the non-EAD group (

Figure 2C). As expected, ARG-1 levels were higher in non-transplanted grafts than in transplanted grafts at the end of both NRP and MP (

Figure 2D). Furthermore, discarded grafts at the end of D-HOPE showed higher ARG-1 levels compared to those at the end of NMP (

Figure S2).

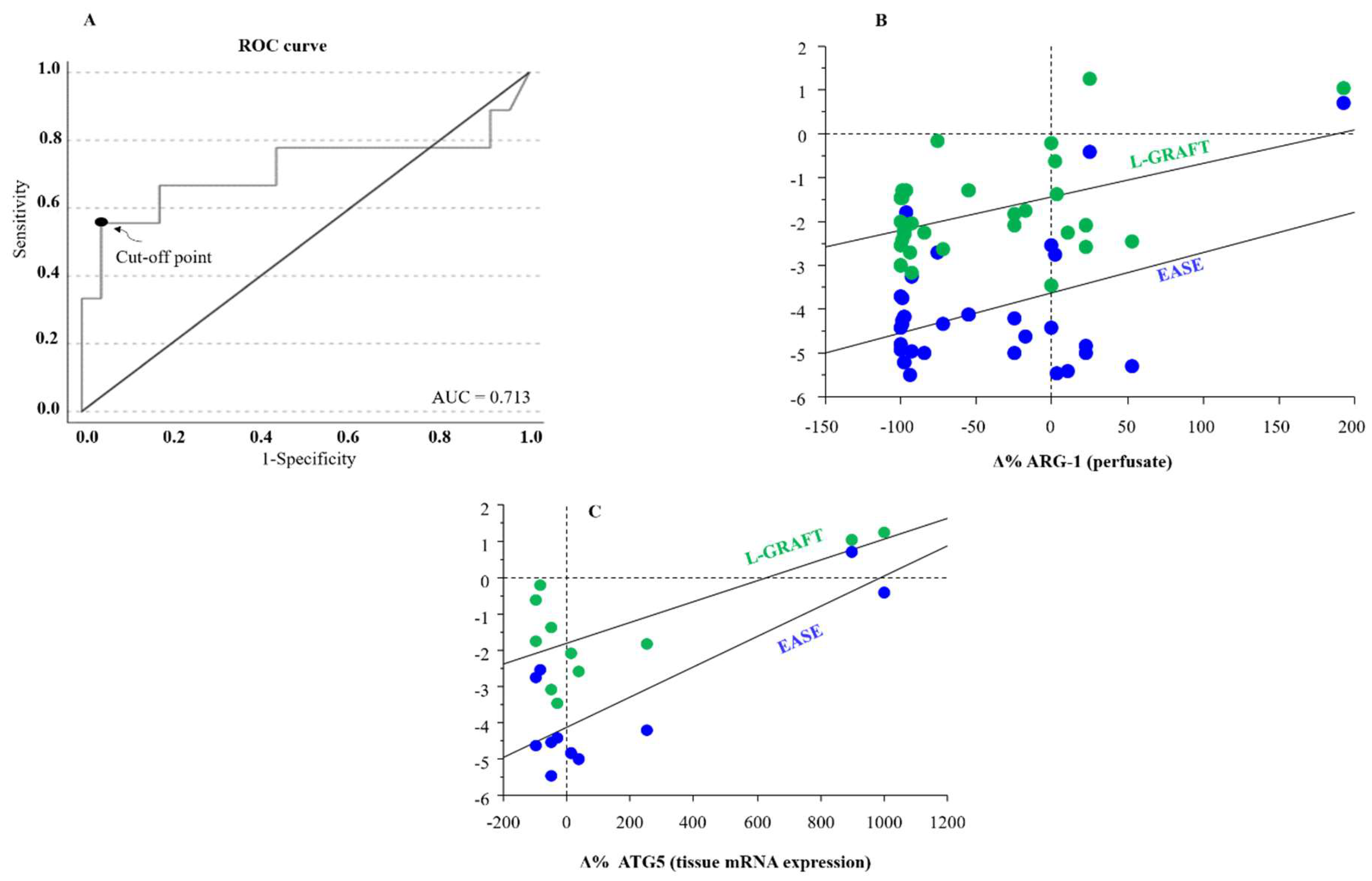

The diagnostic accuracy of ARG-1 levels at the end of ex-situ MP in relation to the diagnosis of EAD was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) method. The ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.713 (95% CI: 0.538-1; p = 0.02) (

Figure 3A). The threshold for differentiation between the EAD-group and non-EAD group, assessed using the Youden method, was 77471 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 55.6% and specificity of 99.9%.

Furthermore, an association between both EASE and L-GRAFT risk scores and the percentage change of ARG-1 at the end of ex-situ MP was observed (

Figure 3B).

Correlation analysis highlighted an interesting association between the percentage delta of tissue autophagy related 5 (ATG5), a protein that plays a critical role in the process of autophagy, with both early allograft failure simplified estimation (EASE) and liver graft assessment following transplantation (L-GRAFT) risk scores, only in D-HOPE

Figure 3C.

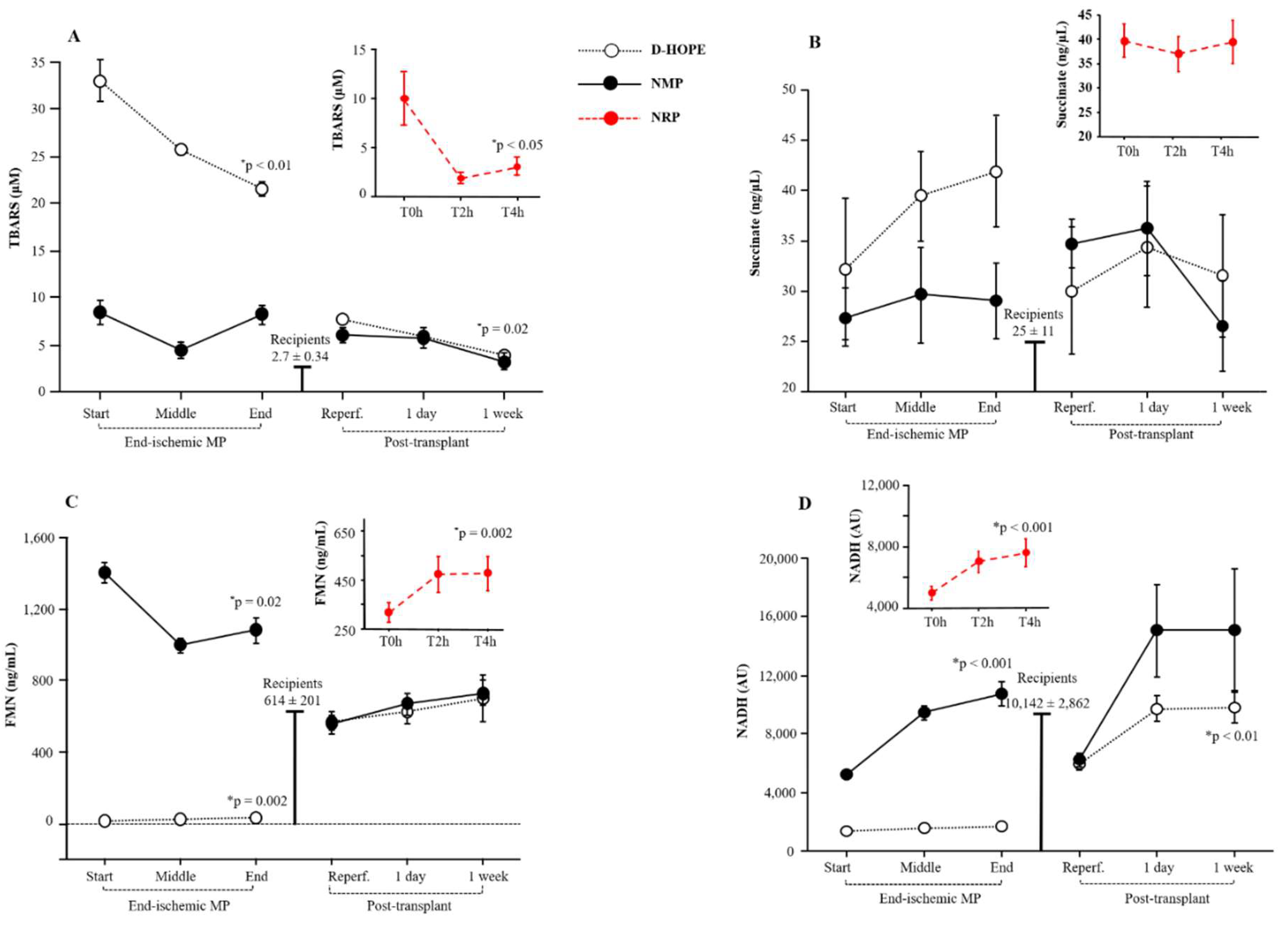

3.3. Oxidative Stress Burst

We quantified the plasma and perfusate lipid peroxidation products, which are indicators of cellular oxidative stress, by measuring TBARS. In comparison to the baseline levels of recipients (levels corresponding to those of healthy subjects), TBARS levels were elevated at the initiation of NRP but declined thereafter (

Figure 4A). In contrast, TBARS levels in the perfusate were significantly higher in the D-HOPE group than in the NMP group from the start of perfusion. Although they decreased throughout perfusion, TBARS levels in D-HOPE remained significantly higher than in NMP (

Figure 4A). In the recipient, TBARS levels were elevated following post-transplant reperfusion, compared to the recipient baseline values, and normalized only after one week (

Figure 4A).

3.4. Response of Cellular Energy Metabolism: Succinate, Fumarate, FMN and NADH

Levels of mitochondrial succinate, whose accumulation represents a key event of hepatic IRI, were elevated in the plasma of donors at the initiation of NRP and remained substantially stable thereafter. During NMP, succinate perfusate levels remained stable (

Figure 4B), but progressively increased during D-HOPE. The gap between the two perfusion approaches was marked at the end of perfusion, as shown in

Figure 4B. After LT, succinate levels showed an immediate elevation following reperfusion and normalized only after one week (

Figure 4B). Compared with the baseline levels of recipients, fumarate plasma levels were elevated at the start of NRP and the start of NMP (

Figure S2A). However, at the end of MP perfusion, these values were equal to the D-HOPE values (

Figure S2A). They remained unchanged one week after transplantation (

Figure S2A).

FMN levels increased during NRP but were significantly lower than the basal levels in recipients

(Figure 4C). During ex-situ MP, the initial FMN levels were surprisingly over 200 times higher in the NMP perfusate (median 1364 ng/mL) than in D-HOPE (median 6.5 ng/mL)

(Figure 4C).

Spectrophotometric analysis of the pre-perfusion solutions of D-HOPE and NMP revealed that the two fluids differed significantly in their FMN content. This marked difference between the two fluids was due to the supplementation of the NMP perfusate with riboflavin B2, a precursor of FMN and FAD. Riboflavin and FMN exhibited identical absorption spectra, which is why riboflavin is used as the standard for the FMN curve. Similarly, donor and recipient plasma FMN values were hundreds of times higher than those in D-HOPE perfusate due to the presence of riboflavin B2 in the plasma

(Figure 4C). Based on these considerations, we analyzed the two curves separately and observed a decrease in FMN levels during NMP (p = 0.0002) and an increase during D-HOPE (p = 0.02) (

Figure S2B). Since riboflavin is not initially contained in the D-HOPE perfusion fluid, the absorbance values in D-HOPE reflect the release of FMN, whereas the decrease in absorbance during NMP can be attributed to riboflavin consumption throughout perfusion. However, the high riboflavin B2 concentration in NMP fluids could mask FMN changes. Therefore, despite the decrease in absorbance during NMP, we could not discriminate whether FMN was decreasing or increasing because the impact of riboflavin on the read absorbance was much larger and made the detection of low changes in FMN inaccurate. Post-transplant FMN plasma levels were consistent with the basal levels of both donors and recipients (

Figure 4C).

NADH, such as FMN or riboflavin, is also found in the circulation. Accordingly, owing to the different compositions of the fluids, the baseline NADH values were found to be elevated in the NMP group compared to the D-HOPE group and were comparable to the baseline values of donors/recipients (

Figure 4D). Owing to the increased metabolism during NMP, the discrepancy between NMP and D-HOPE widened during perfusion (

Figure 4D). Post-transplant NADH plasma levels were comparable to baseline levels observed in recipients and showed a tendency to increase one week after LT (

Figure 4D).

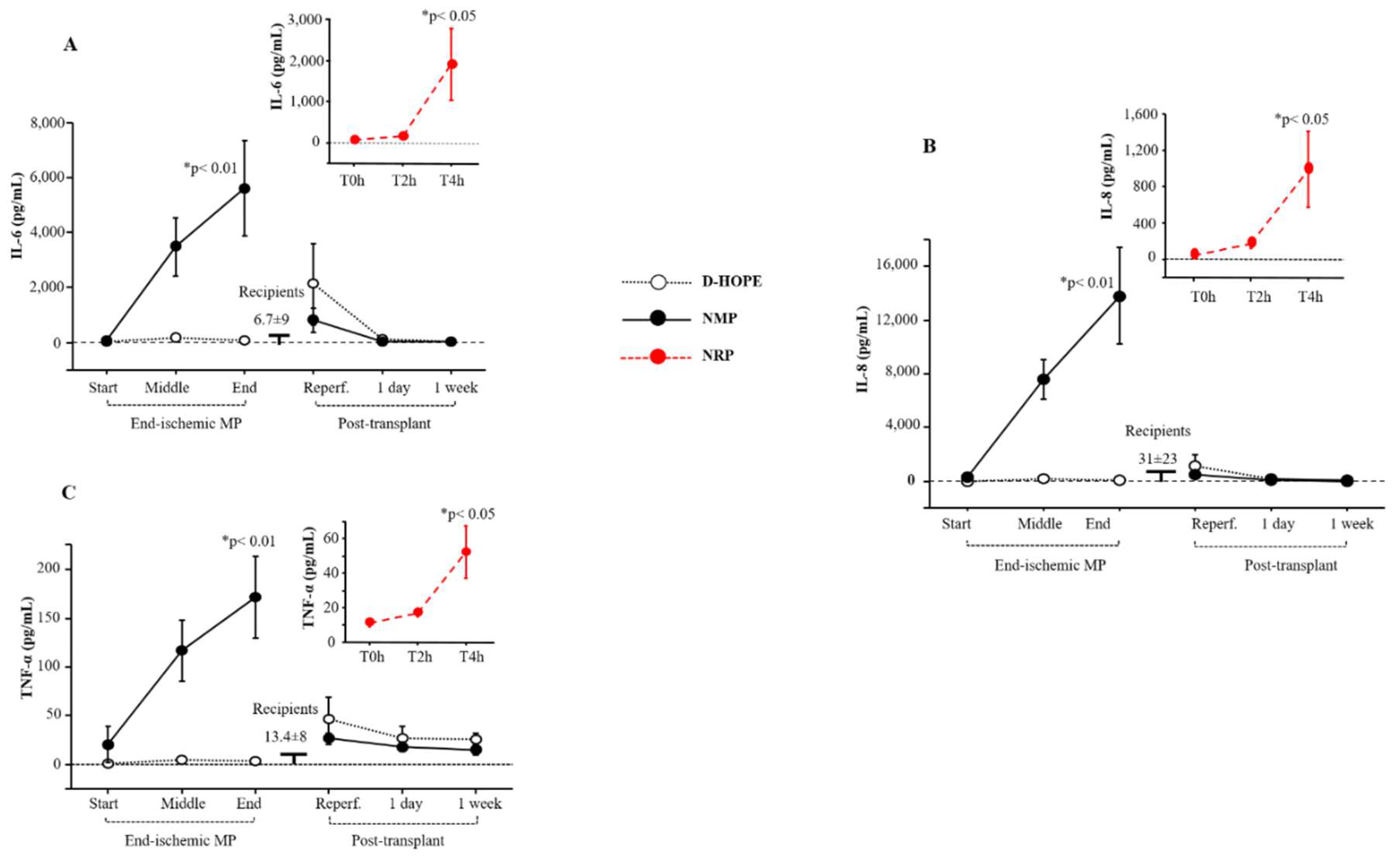

3.5. The trend of Inflammation and Regeneration Measurements

The levels of the inflammatory interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) biomarkers increased during NRP and NMP (

Figure 5A-C), while they remained unchanged during D-HOPE. They returned to normal levels one day after transplantation (

Figure 5A-C).

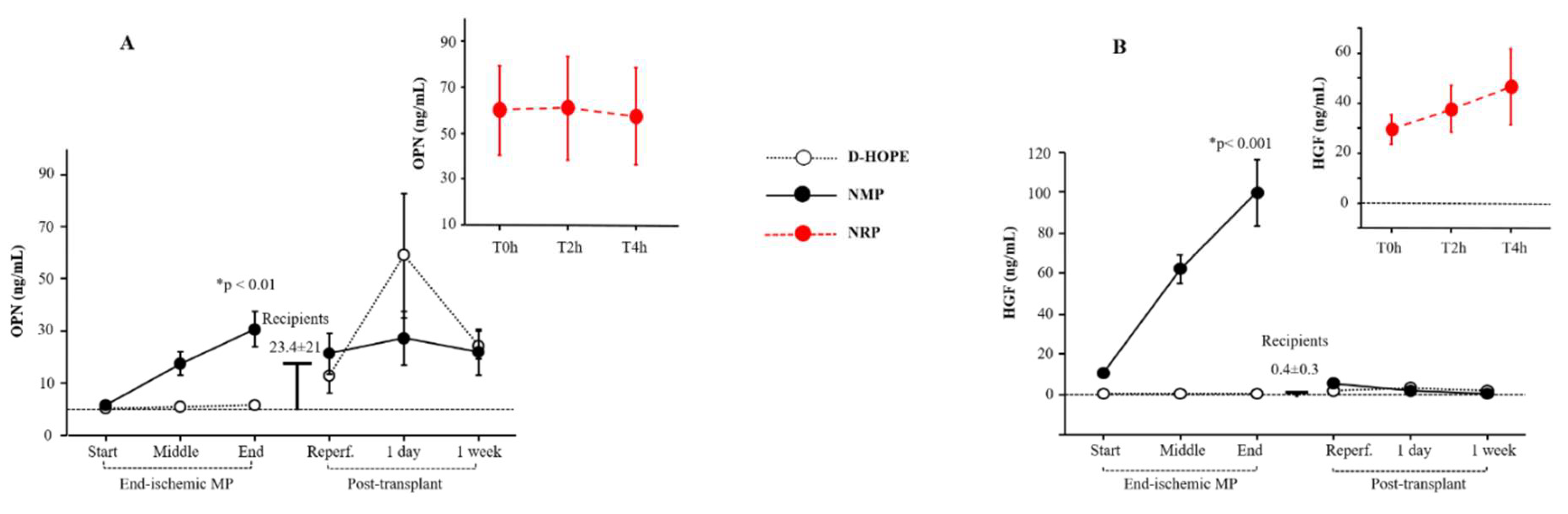

Regeneration biomarkers such as osteopontin (OPN) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were elevated at the start of NRP compared to the recipient baseline values (

Figure 6A-B). The increased coefficient of variation in both OPN and HGF during NRP is due to higher baseline levels in cDCD than in uDCD, as previously demonstrated [

19].

OPN and HGF levels were enhanced only during NMP (

Figure 6A-B), while remained unaltered during D-HOPE (

Figure 6A-B). Post-transplant OPN levels fluctuated and returned to normal values within a week, while HGF levels remained consistently low (

Figure 6A-B).

4. Discussion

The increase in DCD liver transplantation is driven by NRP and ex-situ MP, which improve outcomes and reduce complications[

1,

2]. Despite limited clinical trials, MP shows promise in assessing liver viability, reducing discard rates, and avoiding failing grafts, provided that reliable biomarkers of liver injury and function are available.

To improve the accuracy of liver damage assessment, we focused on two innovative liver cytosolic markers, ARG-1 and GST-α [

17,

18,

19,

20]. These enzymes are particularly appropriate for this context due to their rapid release into circulation and shorter half-life compared to traditional transaminases, allowing for a more timely and precise evaluation of liver injury trends. ARG-1 was found to be more reliable than GST-α, because, in addition to being released early, it also declined more quickly. The relationship between higher ARG-1 levels at the end of ex-situ MP and EAD incidence suggests that the monitoring of ARG-1 during the LT procedure could provide significant and clinically useful information together with or independently of the ALT and lactate levels.

The rapid release of ARG-1 allows early detection of cellular damage, and the rapid clearance of ARG-1 enables timely recognition when active cellular damage has ceased. The trend of GST-α is different, as it has a shorter half-life than transaminases but longer than ARG-1 [

18]. Thus, GST-α levels rise early but remain elevated during ex-situ perfusion and normalize only one week after transplantation. Hence, owing to its early release and remarkably brief half-life, ARG-1 has emerged as a hepatic enzyme with a stronger potential for predictive characteristics in transplant outcomes [

13,

14]. Furthermore, its release can be detrimental because, once in circulation, ARG-1 actively metabolizes circulating L-arginine, inducing its exhaustion. By reducing L-arginine availability, ARG-1 limits the production of nitric oxide and may negatively impact hepatic blood flow [

13,

21,

22]. We demonstrated that ARG-1 levels measured at the end of MPs with a cut-off > 77471 pg/mL, could predict EAD in LT patients. Another intriguing finding is that ARG-1 levels were higher in non-transplanted grafts discarded after MP than in transplanted, offering valuable insights into the role of ARG-1 as a potential biomarker for graft viability. The elevated ARG-1 in discarded grafts could reflect more advanced or irreversible hepatic injury, suggesting that ARG-1 may serve as an indicator of compromised cellular integrity or significant metabolic dysfunction that renders the graft unsuitable for transplantation.

Additionally, this differential ARG-1 expression implies that ARG-1 could be used prospectively to identify marginal or high-risk grafts before transplantation, supporting clinical decision-making during MP by allowing clinicians to assess the real-time status of liver injury and recovery potential.

The results about TBARS levels indicate that NMP may be more effective than D-HOPE in managing oxidative stress, as shown by significantly lower TBARS levels. Elevated TBARS levels in D-HOPE suggest sustained lipid peroxidation, which could compromise cellular integrity and mitochondrial function. This emphasizes the potential advantage of NMP in reducing oxidative damage, potentially enhancing graft viability and recipient outcomes.

Schlegel et al. [

6] demonstrated that rat livers experiencing irreversible graft injury, primary nonfunction, or cholangiopathy initially exhibited elevated levels of FMN and NADH in the perfusate during HOPE. A recent international study [

11] confirmed the predictive value of FMN released during HOPE, supporting better risk stratification of injured livers before implantation. Moreover, in an experimental study, the superiority of D-HOPE over NMP was underlined, mainly relying on monitoring FMN values in the perfusate [

23]. However, as clarified in this study, FMN is already present in the blood in the form of its precursor riboflavin B2, which is also included among the additives in the NMP perfusion liquid. Consequently, when assessing the predictive value of FMN during D-HOPE or NMP, it is crucial to acknowledge that the perfusate compositions in D-HOPE and NMP are different. In D-HOPE alone, the evaluation of mitochondrial damage through perfusate FMN monitoring is free of confounding factors and may predict clinical outcomes after transplantation.

Concerning the elevation of NADH levels in NMP, as opposed to D-HOPE perfusates, it is plausible to attribute this difference to the reactivation of metabolic and inflammatory processes, immunological responses, and alterations in cellular permeability, which may collectively contribute to the extracellular release of NADH [

24,

25]. In brief, while assessing the release of FMN and NADH provides a fast and cost-effective method for evaluating mitochondrial metabolism and cumulative graft damage during donor liver D-HOPE, prudent and cautious application of these markers during NMP is recommended.

Careful analysis of studies reporting liver-damaging effects of autophagy reveals that excessive autophagy, like an inflammatory response, may harm cells by mistakenly targeting normal organelles or proteins [

26,

27,

28]. Our findings show a notable connection between early allograft function risk scores and the percentage change in liver tissue ATG5 following D-HOPE, but not following NMP, confirming that excessive autophagy has a damaging effect on the liver [

27,

28]. This is because excessive autophagy, similar to an exacerbated inflammatory response, can damage cells by mistakenly targeting normal organelles or proteins [

27].

As expected, there was a significant build-up of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, in the perfusate during NMP, whereas no increase was observed during D-HOPE. NMP induces inflammation through metabolism reactivation, oxygen reintroduction and immune cell presence [

29,

30,

31]. Recently, Ohman et al. [

32] demonstrated that human livers with sufficient hepatocellular function during NMP show early activation of the innate immune response, immunogenic modification of donor livers before transplantation, and modulation of immune responses. This implies a potential influence of NMP on modifying the immunogenicity of donor livers before LT. Nevertheless, the occurrence of EAD was not correlated with inflammatory cytokine levels in the perfusate or percentage increases after perfusion.

Another expected result is the activation of regenerative mechanisms during NMP compared with D-HOPE. Liver regeneration is a sophisticated process wherein the interplay between growth factors and cytokines influences the network of interactions [

33,

34]. Following an injury, hemodynamic shifts and matrix remodelling occur, resulting in the release of growth factors and upregulation of specific signalling pathways [

35]. HGF, released from the extracellular matrix immediately increased after liver damage induced by damage-activated serine proteases. Similarly, an increase in OPN levels was observed exclusively during NMP. OPN promotes liver regeneration by boosting cell proliferation and inflammation, reducing apoptosis, and contributing to hepatic regeneration support [

36].

5. Conclusion

In summary, in comparing the distinct preservation and perfusion techniques of NMP and D-HOPE after NRP, our focus was on identifying the predictors of damage. This study emphasized the importance of carefully interpreting biomarkers and considering important differences in perfusion fluid composition to avoid prediction errors and associations with perfusion techniques. Our data support the use of FMN, an easy-to-measure and inexpensive biomarker, during D-HOPE, whereas ARG-1, although more expensive, could be used more universally during any type of MP, including NRP. This study has limitations, notably the restricted sample size of DCD numbers compared with the two perfusion systems. The limited number of patients precluded the execution of multivariate analyses for predictive assessment, allowing only univariate analyses to be conducted. To assess graft viability and predict outcomes more accurately, further research is essential to identify reliable biomarkers that could supplement or replace those currently in use.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.B., D.G., S. DT.; Methodology: S.B., L.R., D. Pe., E.B., G.C., P.C., S.P., C.L., A.P., G.B., L.P., A.T., S.P., C.M., J.B., S.P.; Formal Analysis: C.L., G.B., S.B., G.T.; Data Curation, C.L., D.P., G.B., D.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.B., D.G., S. DT.; Writing—Review and Editing D. Pe., R.R, D. Pa., G.B., D.G.; Funding Acquisition: G.B., D.G., S. DT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been supported by the Tuscany Region, Bando Salute 2018, DCDNet Project.

Ethics Approval Statement

Comitato Etico Area Vasta Nord-Ovest, CEAVNO approval#17848, July 23, 2020.

Data Availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Davide Ghinolfi) upon reasonable request.

Clinical Trial Registration

Clinicaltrial.gov #NCT04744389.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ECMO Team Careggi Firenze, ECMO Team Pisa, and ECMO Team Siena for their contributions. They thank all surgeons, nurses, and transplant staff for their valuable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine-aminotransferase; ARG-1, arginase 1; AST, aspartate-aminotransferase; ATG-5, autophagy-related gene-5; DCD, donation after cardiocirculatory death; cDCD, controlled DCD; uDCD, uncontrolled DCD; EAD, early allograft dysfunction; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; D-HOPE, dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IL-6/-8, interleukin-6/-8; IRI, ischemia-reperfusion injury; LT, Liver Transplantation; NADH, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NMP, normothermic machine perfusion; NRP, normothermic regional perfusion; OPN, osteopontin; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α; -GST-α, glutathione-S-transferase- α; WIT, warm ischemia time.

References

- Ghinolfi, D.; Melandro, F.; Torri, F.; Esposito, M.; Bindi, M.; Biancofiore, G.; Basta, G.; Del Turco, S.; Lazzeri, C.; Rotondo, M. I.; Peris, A.; De Simone, P. The role of sequential normothermic regional perfusion and end-ischemic normothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation from very extended uncontrolled donation after cardiocirculatory death. Artif Organs 2023, 47, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Del Val, A.; Guarrera, J.; Porte, R. J.; Selzner, M.; Spiro, M.; Raptis, D. A.; Friend, P. J.; Nasralla, D.; Group, E. R. O. o. W. Does machine perfusion improve immediate and short-term outcomes by enhancing graft function and recipient recovery after liver transplantation? A systematic review of the literature, meta-analysis and expert panel recommendations. Clin Transplant 2022, 36, e14638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croce, A. C.; Ferrigno, A.; Bertone, V.; Piccolini, V. M.; Berardo, C.; Di Pasqua, L. G.; Rizzo, V.; Bottiroli, G.; Vairetti, M. Fatty liver oxidative events monitored by autofluorescence optical diagnosis: Comparison between subnormothermic machine perfusion and conventional cold storage preservation. Hepatol Res 2017, 47, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Thompson, E.; Bates, L.; Pither, T. L.; Hosgood, S. A.; Nicholson, M. L.; Watson, C. J. E.; Wilson, C.; Fisher, A. J.; Ali, S.; Dark, J. H. Flavin Mononucleotide as a Biomarker of Organ Quality-A Pilot Study. Transplantation Direct 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meszaros, A. T.; Hofmann, J.; Buch, M. L.; Cardini, B.; Dunzendorfer-Matt, T.; Nardin, F.; Blumer, M. J.; Fodor, M.; Hermann, M.; Zelger, B.; Otarashvili, G.; Schartner, M.; Weissenbacher, A.; Oberhuber, R.; Resch, T.; Troppmair, J.; Fner, D.; Zoller, H.; Tilg, H.; Gnaiger, E.; Hautz, T.; Schneeberger, S. Mitochondrial respiration during normothermic liver machine perfusion predicts clinical outcome. EBioMedicine 2022, 85, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, A.; Muller, X.; Mueller, M.; Stepanova, A.; Kron, P.; de Rougemont, O.; Muiesan, P.; Clavien, P. A.; Galkin, A.; Meierhofer, D.; Dutkowski, P. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion protects from mitochondrial injury before liver transplantation. Ebiomedicine 2020, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, X.; Schlegel, A.; Kron, P.; Eshmuminov, D.; Wurdinger, M.; Meierhofer, D.; Clavien, P. A.; Dutkowski, P. Novel Real-time Prediction of Liver Graft Function During Hypothermic Oxygenated Machine Perfusion Before Liver Transplantation. Ann Surg 2019, 270, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Mergental, H.; Hann, A.; Perera, M.; Afford, S. C.; Mirza, D. F. How Machine Perfusion Ameliorates Hepatic Ischaemia Reperfusion Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huwyler, F.; Eden, J.; Binz, J.; Cunningham, L.; Sousa Da Silva, R. X.; Clavien, P. A.; Dutkowski, P.; Tibbitt, M. W.; Hefti, M. A Spectrofluorometric Method for Real-Time Graft Assessment and Patient Monitoring. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023, 10, e2301537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrono, D.; Lonati, C.; Romagnoli, R. Viability testing during liver preservation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2022, 27, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, J.; Thorne, A. M.; Bodewes, S. B.; Patrono, D.; Roggio, D.; Breuer, E.; Lonati, C.; Dondossola, D.; Panayotova, G.; Boteon, A.; Walsh, D.; Carvalho, M. F.; Schurink, I. J.; Ansari, F.; Kollmann, D.; Germinario, G.; Rivas Garrido, E. A.; Benitez, J.; Rebolledo, R.; Cescon, M.; Ravaioli, M.; Berlakovich, G. A.; De Jonge, J.; Uluk, D.; Lurje, I.; Lurje, G.; Boteon, Y. L.; Guarrera, J. V.; Romagnoli, R.; Galkin, A.; Meierhofer, D.; Porte, R. J.; Clavien, P. A.; Schlegel, A.; de Meijer, V. E.; Dutkowski, P. Assessment of liver graft quality during hypothermic oxygenated perfusion: the first international validation study. J Hepatol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghinolfi, D.; Rreka, E.; De Tata, V.; Franzini, M.; Pezzati, D.; Fierabracci, V.; Masini, M.; Cacciatoinsilla, A.; Bindi, M. L.; Marselli, L.; Mazzotti, V.; Morganti, R.; Marchetti, P.; Biancofiore, G.; Campani, D.; Paolicchi, A.; De Simone, P. Pilot, Open, Randomized, Prospective Trial for Normothermic Machine Perfusion Evaluation in Liver Transplantation From Older Donors. Liver Transpl 2019, 25, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G, S. C.; van Waarde, A.; I, F. A.; Domling, A.; P, H. E. Arginase as a Potential Biomarker of Disease Progression: A Molecular Imaging Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mandili, G.; Alchera, E.; Merlin, S.; Imarisio, C.; Chandrashekar, B. R.; Riganti, C.; Bianchi, A.; Novelli, F.; Follenzi, A.; Carini, R. Mouse hepatocytes and LSEC proteome reveal novel mechanisms of ischemia/reperfusion damage and protection by A2aR stimulation. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 573–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cziráki, A.; Lenkey, Z.; Sulyok, E.; Szokodi, I.; Koller, A. L-Arginine-Nitric Oxide-Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Pathway and the Coronary Circulation: Translation of Basic Science Results to Clinical Practice. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, S. M.; Lam, W. M.; Lam, T. L.; Chong, H. C.; So, P. K.; Kwok, S. Y.; Arnold, S.; Cheng, P. N.; Wheatley, D. N.; Lo, W. H.; Leung, Y. C. Pegylated derivatives of recombinant human arginase (rhArg1) for sustained in vivo activity in cancer therapy: preparation, characterization and analysis of their pharmacodynamics in vivo and in vitro and action upon hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HCC). Cancer Cell Int 2009, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, R. J.; Kullak-Ublick, G. A.; Aubrecht, J.; Bonkovsky, H. L.; Chalasani, N.; Fontana, R. J.; Goepfert, J. C.; Hackman, F.; King, N. M. P.; Kirby, S.; Kirby, P.; Marcinak, J.; Ormarsdottir, S.; Schomaker, S. J.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; Wolenski, F.; Arber, N.; Merz, M.; Sauer, J. M.; Andrade, R. J.; van Bommel, F.; Poynard, T.; Watkins, P. B. Candidate biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of drug-induced liver injury: An international collaborative effort. Hepatology 2019, 69, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuczejko, J.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Szewczyk-Golec, K. Plasma alpha-Glutathione S-Transferase Evaluation in Patients with Acute and Chronic Liver Injury. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 2019, 5850787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, G.; Melandro, F.; Babboni, S.; Del Turco, S.; Ndreu, R.; Torri, F.; Martinelli, C.; Silvestrini, B.; Peris, A.; Lazzeri, C.; Guarracino, F.; Morganti, R.; Maremmani, P.; Bertini, P.; De Simone, P.; Ghinolfi, D. An extensive evaluation of hepatic markers of damage and regeneration in controlled and uncontrolled donation after circulatory death. Liver Transplantation 2023, 29, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, I.; Rule, J. A.; Wians, F. H.; Poirier, M.; Grant, L.; Lee, W. M. alpha-Glutathione S-Transferase: A New Biomarker for Liver Injury? J Appl Lab Med 2016, 1, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.; Chen, F.; Sun, H.; Lin, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Q. Serum Arginine Level for Predicting Early Allograft Dysfunction in Liver Transplantation Recipients by Targeted Metabolomics Analysis: A Prospective, Single-Center Cohort Study. Adv Biol (Weinh) 2024, e2400128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Zhou, H.; Xu, F.; Yang, H.; Li, P.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, P.; Kong, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Impairs Blood-Brain Barrier Partly Due to Release of Arginase From Injured Liver. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 724471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panconesi, R.; Carvalho, M. F.; Eden, J.; Fazi, M.; Ansari, F.; Mancina, L.; Navari, N.; Sousa Da Silva, R. X.; Dondossola, D.; Borrego, L. B.; Pietzke, M.; Peris, A.; Meierhofer, D.; Muiesan, P.; Galkin, A.; Marra, F.; Dutkowski, P.; Schlegel, A. Mitochondrial injury during normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) and hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) in a rodent model of DCD liver transplantation. EBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, F.; Adriouch, S.; Brass, A.; Jung, C.; Moller, S.; Scheuplein, F.; Bannas, P.; Seman, M.; Koch-Nolte, F. Extracellular NAD and ATP: Partners in immune cell modulation. Purinergic Signal 2007, 3, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, R. S.; Handy, D. E.; Loscalzo, J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 28, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Ye, Q. Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion alleviates liver injury in donation after circulatory death through activating autophagy in mice. Artif Organs 2019, 43, E320–E332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Xu, Q.; Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Liu, J.; Tang, J. Role of autophagy and its signaling pathways in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Transl Res 2017, 9, 4470–4480. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, B.; Yuan, W.; Wu, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B. Autophagy in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeel, J.; Gilbo, N.; Heedfeld, V.; Wylin, T.; Libbrecht, L.; Jochmans, I.; Pirenne, J.; Korf, H.; Monbaliu, D. The Distinct Innate Immune Response of Warm Ischemic Injured Livers during Continuous Normothermic Machine Perfusion. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. C. H.; Edobor, A.; Lysandrou, M.; Mirle, V.; Sadek, A.; Johnston, L.; Piech, R.; Rose, R.; Hart, J.; Amundsen, B.; Jendrisak, M.; Millis, J. M.; Donington, J.; Madariaga, M. L.; Barth, R. N.; di Sabato, D.; Shanmugarajah, K.; Fung, J. The Effect of Normothermic Machine Perfusion on the Immune Profile of Donor Liver. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 788935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fan, Y.; Ding, H.; Han, D.; Yan, Y.; Wu, R.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, X. Normothermic machine perfusion attenuates hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting CIRP-mediated oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 11310–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohman, A.; Raigani, S.; Santiago, J. C.; Heaney, M. G.; Boylan, J. M.; Parry, N.; Carroll, C.; Baptista, S. G.; Uygun, K.; Gruppuso, P. A.; Sanders, J. A.; Yeh, H. Activation of autophagy during normothermic machine perfusion of discarded livers is associated with improved hepatocellular function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2022, 322, G21–G33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinelli, L.; Muttillo, E. M.; Felli, E.; Baiocchini, A.; Giannone, F.; Marescaux, J.; Mutter, D.; De Mathelin, M.; Gioux, S.; Felli, E.; Diana, M. Surgical Models of Liver Regeneration in Pigs: A Practical Review of the Literature for Researchers. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodor, M.; Salcher, S.; Gottschling, H.; Mair, A.; Blumer, M.; Sopper, S.; Ebner, S.; Pircher, A.; Oberhuber, R.; Wolf, D.; Schneeberger, S.; Hautz, T. The liver-resident immune cell repertoire - A boon or a bane during machine perfusion? Front Immunol 2022, 13, 982018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretzsch, E.; Niess, H.; Khaled, N. B.; Bosch, F.; Guba, M.; Werner, J.; Angele, M.; Chaudry, I. H. Molecular Mechanisms of Ischaemia-Reperfusion Injury and Regeneration in the Liver-Shock and Surgery-Associated Changes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patouraux, S.; Rousseau, D.; Rubio, A.; Bonnafous, S.; Lavallard, V. J.; Lauron, J.; Saint-Paul, M. C.; Bailly-Maitre, B.; Tran, A.; Crenesse, D.; Gual, P. Osteopontin deficiency aggravates hepatic injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, e1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the donor and patient selection.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the donor and patient selection.

Figure 2.

Dynamic change of GST-α (A) and ARG-1(B) during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported. C) Dynamic change of ARG-1 levels between the EAD group and non-EAD group during NRP, end-ischemic MPs of grafts and in recipients until a week post-transplant. D) Differences in ARG-1 levels between the non-transplanted group and transplanted group during NRP and end-ischemic MPs of grafts.

Figure 2.

Dynamic change of GST-α (A) and ARG-1(B) during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported. C) Dynamic change of ARG-1 levels between the EAD group and non-EAD group during NRP, end-ischemic MPs of grafts and in recipients until a week post-transplant. D) Differences in ARG-1 levels between the non-transplanted group and transplanted group during NRP and end-ischemic MPs of grafts.

Figure 3.

A) ROC curve and sensitivity/specificity graph for ARG-1 concentration differentiating groups at the end of ex-situ MP. The threshold for differentiation between EAD group and non-EAD group was 77471 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 55.6% and a specificity of 99.9%. AUC, area under the ROC curve; ROC, receiver operator characteristic. B) Correlation between Δ% ARG1 during end-ischemic MPs [(Tend-Tstart/Tstart)*100] and L-GRAFT (r = 0.481, p < 0.01 ), and EASE (r = 0.448, p < 0.05). C) Correlation between Δ% ATG5 tissue mRNA expression during end-ischemic MPs [(Tend-Tstart/Tstart)*100] and L-GRAFT (r = 0.734, p < 0.01 ), and EASE (r = 0.830, p < 0.001) in D-HOPE group.

Figure 3.

A) ROC curve and sensitivity/specificity graph for ARG-1 concentration differentiating groups at the end of ex-situ MP. The threshold for differentiation between EAD group and non-EAD group was 77471 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 55.6% and a specificity of 99.9%. AUC, area under the ROC curve; ROC, receiver operator characteristic. B) Correlation between Δ% ARG1 during end-ischemic MPs [(Tend-Tstart/Tstart)*100] and L-GRAFT (r = 0.481, p < 0.01 ), and EASE (r = 0.448, p < 0.05). C) Correlation between Δ% ATG5 tissue mRNA expression during end-ischemic MPs [(Tend-Tstart/Tstart)*100] and L-GRAFT (r = 0.734, p < 0.01 ), and EASE (r = 0.830, p < 0.001) in D-HOPE group.

Figure 4.

Dynamic change of TBARS, succinate, FMN and NADH during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

Figure 4.

Dynamic change of TBARS, succinate, FMN and NADH during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

Figure 5.

Dynamic change of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

Figure 5.

Dynamic change of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. Values are presented as mean ± SE. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

Figure 6.

Dynamic change of OPN, HGF, GST-α during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

Figure 6.

Dynamic change of OPN, HGF, GST-α during NRP, end-ischemic MPs and in recipients until a week post-transplant. *Significant changes over time within each group (Friedman’s test with Bonferroni correction). Only values of p <0.05, considered as significant, are reported.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).