1. Introduction

Liver diseases have placed a huge burden on global public health, leading to 2 million deaths worldwide each year. This includes 1 million deaths dues to complications of cirrhosis, with the remainder dying from liver cancer or viral hepatitis[

1]. Liver diseases that progress to advanced stages are often fatal or need lifelong management. Therefore, there is an urgent need for understanding of pathogenesis and development of drugs aimed at reversing[

2] or limiting the progression of liver disease. Over the years, efforts have been made to gain insight into liver diseases with a variety of diseased research models, from hepatocytes cultured in vitro, to small (e.g., rodents) and large animal (e.g., dogs, primates, pigs) models, with the purpose of using them for various clinical applications, biochemical and pharmacological studies[

3]. More advanced models, including use of bio-artificial liver and three

-dimensional (3D) cell culture, as well as liver organoid have also been employed[

4,

5,

6]. However, none of them has capability to faithfully represent complete and accurate physiological and pathological features of human liver, making it difficult to translate relevant studies of clinical manifestations.

Ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) is an innovative technology in preservation of organ that approximates to normal liver physiology and metabolism without energy depletion and accumulation of waste products outside of the human body[

7]. NMP is gaining in popularity globally as a technology to preserve and evaluate grafts during liver transplantation (LT), which has been proved to inhibit inflammation and minimize liver injury to maintain the stability of internal environment[

8,

9]. Clavien et al. created breakthrough work to extended the period of ex situ preservation of livers through NMP for up to 1 week[

10], making it possible for livers to survive normally in vitro for a long time. All these lay a foundation for the establishment of human whole diseased liver by NMP. To date, many research groups are investing NMP as a dynamic platform for liver repair and regeneration. Thence, we turn to the human whole diseased livers recovered from LT recipients which may realistically imitate liver diseases better. However, there is no established machine perfusion device specifically for diseased liver.

We aim to cultivate diseased liver by engineering a machine perfusion system that could reproduce the main features of the human whole diseased livers recovered from LT recipients. Herein, we firstly demonstrate the machine perfusion device suitable for the human whole diseased livers and report our experience on NMP of human whole diseased livers, which may be used for disease and treatment research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

This study took the human diseased livers recovered from LT recipients for research. These diseased livers were removed during total liver resection of the recipients and then transferred to the machine perfusion system for treatment. Exclusion criteria for diseased liver were severe organ parenchymal, severe vascular retrieval damage, vascular anomalies that could not all be cannulated, the evidence of possible intrahepatic thrombosis, very poor perfusion at retrieval after cold flush. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, and informed consent was obtained from the participants.

2.2. Normothermic machine perfusion system

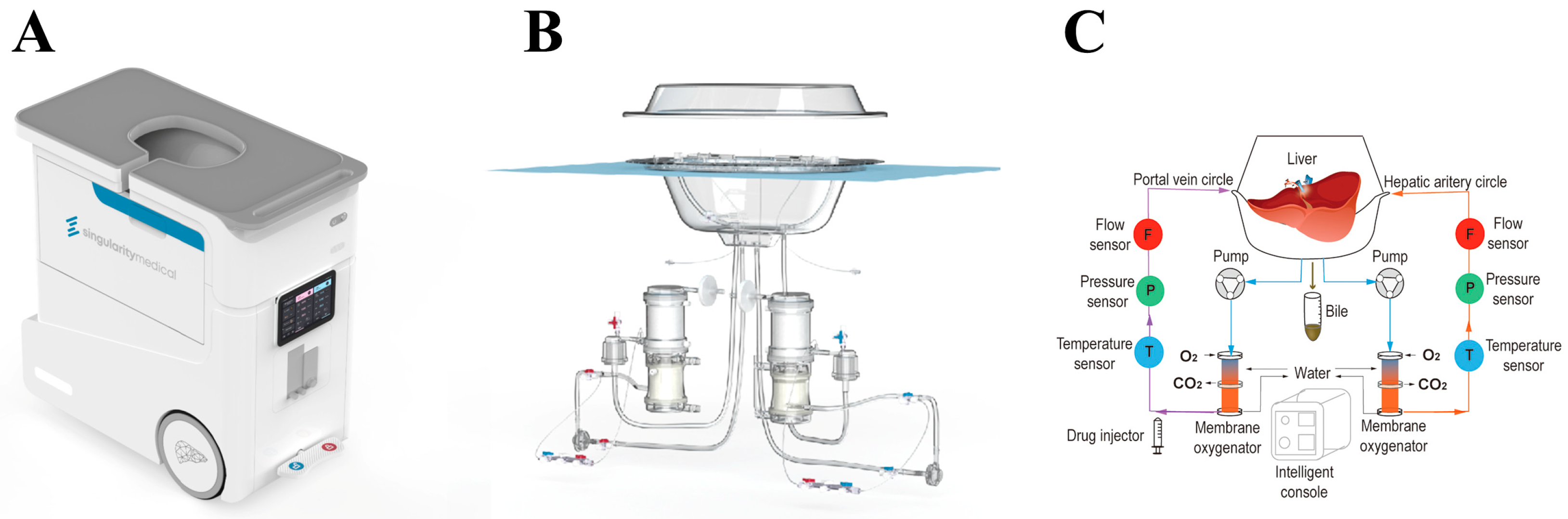

The machine perfusion system in this study called Life-XDL was developed on the basis of the Life-X100 (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) which used for human whole diseased livers perfusion specially (

Figure 1). The Life-XDL consisted of an integrated system included perfusion system, liver protective equipment and console.

2.2.1. The perfusion system of the Life-XDL

2.2.1.1. Hemodynamic control

Two magnetic driving centrifugal pump and two circuits constituted the hemodynamic perfusion system. Flow sensors and pressure sensors measured flow and pressure in the respective circuit tube lines. The hemodynamic perfusion system supplied blood, oxygen and nutrients to liver through the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The hepatic artery circuit delivered oxygen-rich blood to the hepatic artery at high pressure (systolic and diastolic pressure of 80mmHg and 50mmHg respectively with 60 beats per minute) in a pulsatile manner, while the portal vein circuit supplied blood to the portal vein at low pressure (8-13 mmHg) at a non-pulsatile manner. The hepatic and portal flow rate were regulated by their pump respectively and the pulsatile flow in the hepatic artery was realized by varying rotational speed operation of the blood pump. There was also a blood filter in each circuit to filter air bubbles and impurities. The blood in the diseased liver was returned to the organ reservoir by the vena cava and then directly to the blood reservoir. What’s more, the temperature control set maintained the perfusate temperature at the physiological temperature of 37℃ and continuously monitored it, even could be adjusted according to the clinical needs ranging from 10-45℃.

2.2.1.2. Gas supply control

Two membrane oxygenators and two individual gas-flow controllers for oxygen and air were used to maintain the stability of oxygen partial pressure (pO2), oxygen partial pressure (pO2), and even potential of hydrogen (pH) during NMP. Both of two circuits had an oxygenator which provided oxygen to the blood and removed carbon dioxide. By adjusting flow and oxygen concentration, pO2 was adapted between 100-200 mmHg and pCO2 was adapted between 25-45 mmHg. In addition, the system continuously monitored the oxygen saturation in the vena cava using a saturation sensor. The system used this saturation sensor to continuously monitor the oxygen saturation, and adjusted the oxygenation exchange rate and hepatic blood flow through real-time feedback.

2.2.2. The liver protective equipment of the Life-XDL

The organ reservoir, silicone mat and protective cover constituted the Life-XDL liver protective equipment. The solid organ reservoir kept the liver in a safe place, even if there are bumps in transit. The silicone mat could effectively reduce the pressure on the liver surface after improvement based on the mechanics, and even filtered out impurities or thrombosis that occurred during machine perfusion. In addition, it could prevent bubbles from entering the circulation circuits. The protective cover was matched with the organ reservoir to effectively protect the organ, and can effectively prevent bacterial invasion.

2.2.3. The intelligent console of the Life-XDL

The console was composed of water bath heating temperature control module, artery control module, portal vein control module, automatic drug delivery module and monitoring module. The console could clearly display the condition of the diseased liver during NMP, including arterial and portal temperature, flow and pressure, and record the situation for a long time. Its operation was simple, and it even could be adjusted to achieve different temperature machine perfusion.

2.2.4. Perfusate components and additives

The perfusate was prepared by mixing 8 units of human-packed washed red blood cells, 800ml succinylated gelatin, 10ml multi-trace elements (Addamel, Fresenius-Kabi SSPC, China), 30ml calcium gluconate (10%) and 3ml magnesium sulfate (25%). Perfusion was maintained at normothermia (36℃) without perfusate exchange and anticoagulated using heparin (17500U, daily). The imipenem/cilastatin (1g daily) was used for antibiotic prophylaxis. Nutrition was maintained with compound amino acid (18AA-Ⅱ) (10ml per hour) and methylprednisolone (500mg daily). Glucose was maintained between 5–15mmol/L by glucose (10%), and insulin infusions, and the acid–base balance was maintained to a pH of 7.35-7.45 by carbon dioxide concentration of gas or sodium bicarbonate (5%) according artery blood analysis results.

2.3. Diseased liver harvest and perfusion

The diseased livers were all recovered from recipients who had undergone LT. We developed a surgical procedure for isolating the diseased liver and its vascular supply during total liver resection. The cystic duct was ligated first, then the lower common bile duct was transected and intubated, followed by intermediate resection of the hepatic artery proper and portal vein. For the purpose of intubation and subsequent operation, the main portal vein should be preserved 2.5cm long from the left and right bifurcation and the artery should be isolated to the proper hepatic artery. Finally, the liver was retrieved by resection of the suprahepatic and infrahepatic vena cava.

An immediate cold flush through both hepatic artery and the portal vein was carried out with 1500 mL normal saline and 37500U heparin at 4 ℃ to wash out the residue blood of the retrieved livers. The hepatic artery and portal vein were intubated and connected to the Life-XDL and the ex vivo NMP was initiating. During the first period of perfusion, the perfusion starting pressure of hepatic artery and portal vein were low and temperature increased slowly, and then gradually adjusted to the setting pressure and temperature levels. In addition, in order to promote microcirculation of livers during the first period of perfusion, vasoactive drugs like papaverine and diltiazem were usually added and maintained as necessary.

2.4. Liver viability assessment and histological analysis

The arterial blood gas analysis and laboratory test of perfusate in all the cases as well as bile production were performed in different time point. In addition, the perfusate was also undergone bacterial culture before and after NMP to determine if there was any bacterial invasion. The tissues of all human diseased livers were collected to Paraffin-embedded slides at the beginning and end of NMP and those slides were deparaffinized with xylene and dehydrated with graded alcohols, then hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining for histological analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Liver recipient characteristics

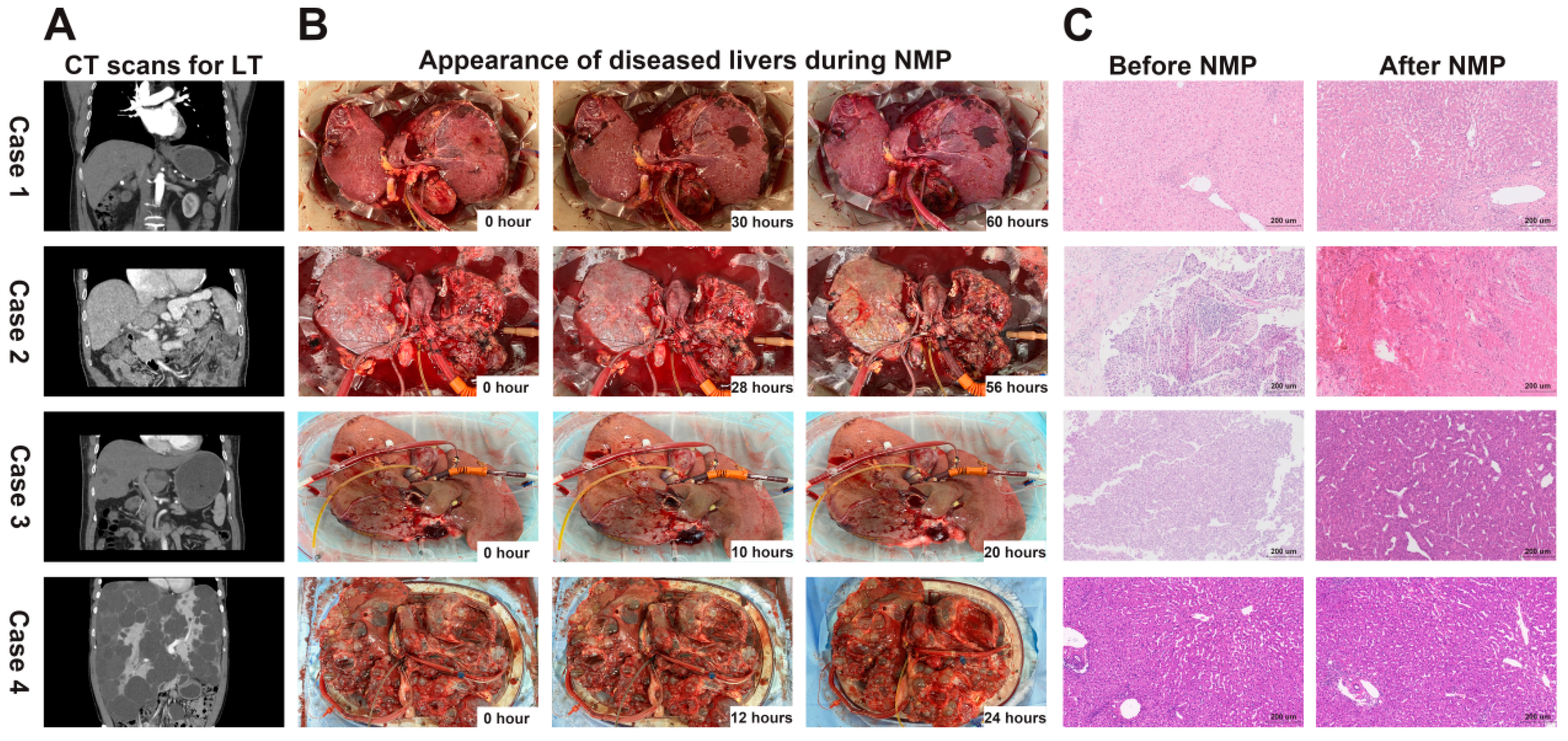

In this study, we used the Life-XDL machine perfusion system to establish four case of diseased liver models, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) related cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with HBV related cirrhosis, HCC with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis, and polycystic liver. The four cases diagnosed with or without hepatitis B virus infection and underwent LT in the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University in 2021 or 2022. The liver’s computed tomography (CT) scans of the four cases before LT are shown in

Figure 2A. The basic characteristics of the four cases is shown in the

Table 1.

3.2. Stable and homogeneous vascular perfusion and perfusate homeostasis during NMP

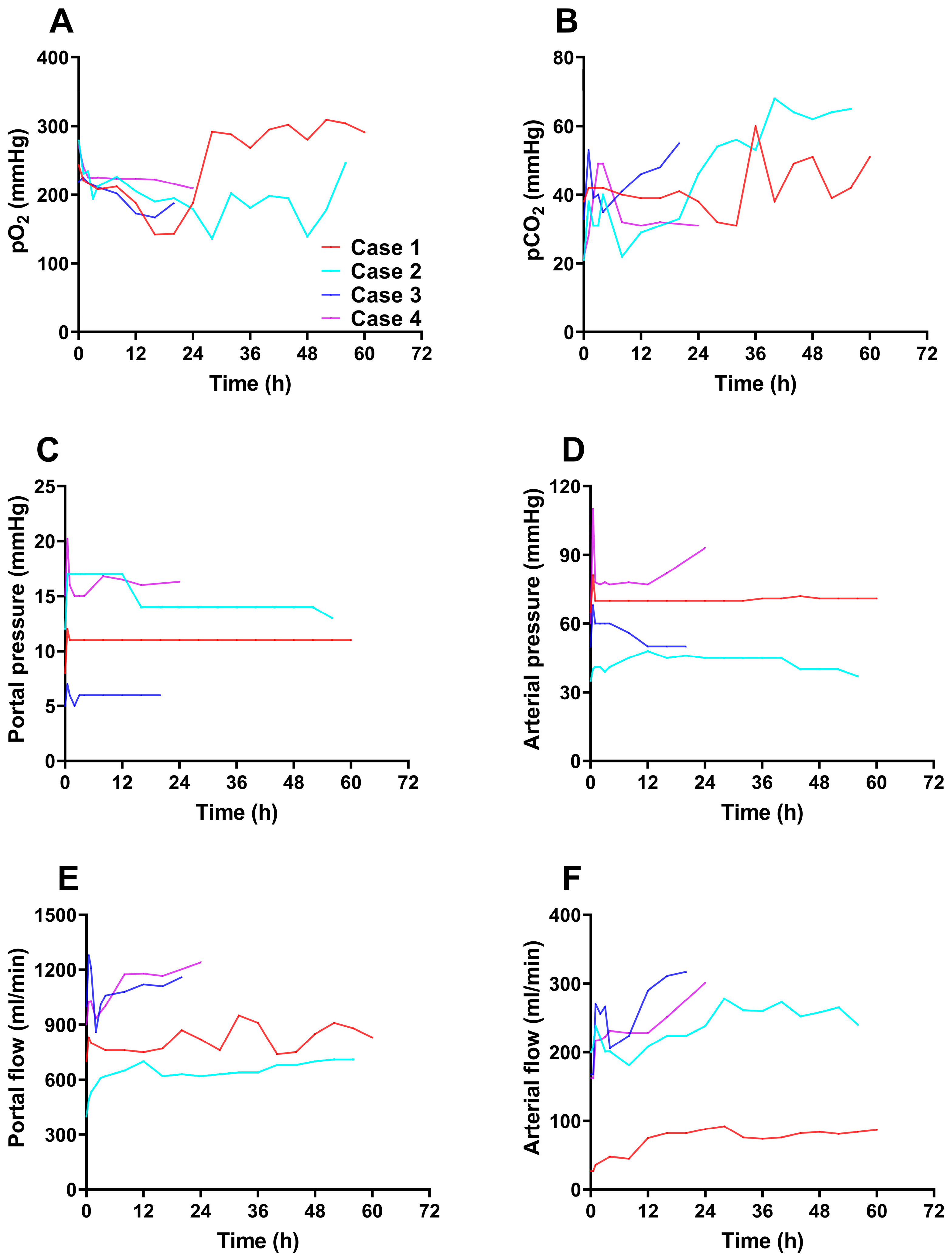

During the entire perfusion, the Life-XDL machine perfusion system was stable, and no technical problems were observed. The pO

2 was fluctuated between 90-310 mmHg indicating a normal oxygenated condition (

Figure 3A), while the pCO

2 of all four livers was kept stable range from 20 to 65 mmHg conducted by Life-XDL (

Figure 3B). The four cases portal vein flow was maintained stable at 0.5-1.3 L/min at 1 hour after perfusion with the pressure stabilizing at 5-17 mmHg (

Figure 3C and 3D). In case 1, although the arterial flow rate did not reach 150ml/min, it remained stable and gradually increased during the entire perfusion with mean perfusion pressure at 70 to 90 mmHg. In case 2 and 3, the mean hepatic artery flow was kept stable at 1 hour after perfusion ranged from 150-310 ml/min with mean perfusion pressure at 40 to 60 mmHg. In case 4, although mean arterial pressure remained high at around 75mmHg, arterial flow ranged from 150-300 ml/min stably (

Figure 3E and 3F). These findings suggested that the microvasculature was patent and the pO

2, pCO

2, artery and portal vein pressure and flow were kept at the approximate physiological state under Life-XDL.

3.3. Excellent organ viability and minimal liver function injury during NMP

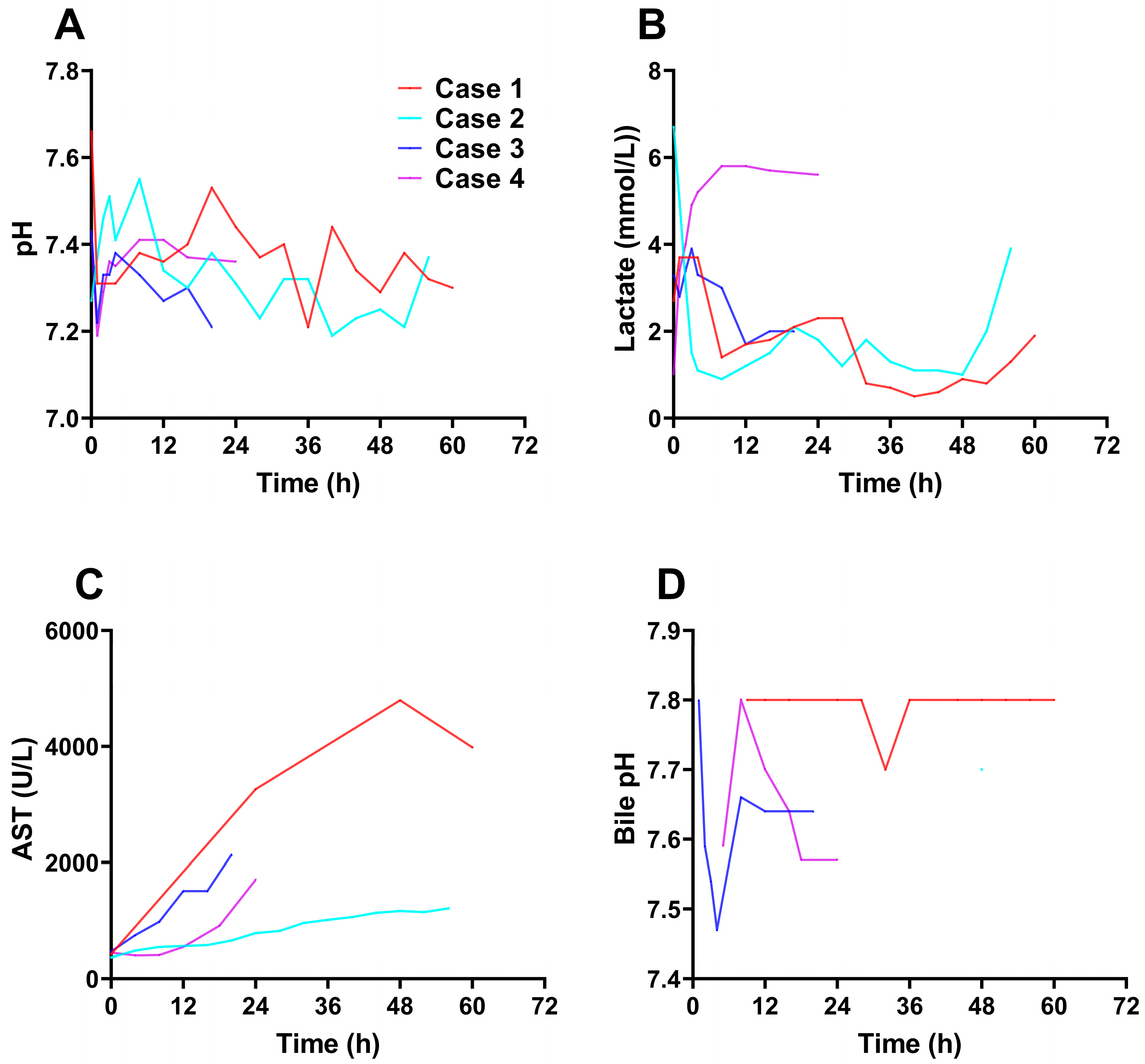

The pH value of perfusate was maintained above 7.3 in most of time. Although the pH of the perfusate in case 1 showed a downward trend during 30-36h and in case 2 showed a downward trend during 24-28h and 40-52h, it could reach more than 7.3 after adjustment, which might be caused by the gradual rise of the pCO

2 and not timely adjustment (

Figure 4A). The lactate levels of perfusate was slightly increased or unchanged at the initiation of the perfusion in case 1, 2 and 3, but rapidly decreased and remained at a low level as time went on, although it showed a slightly increasing trend at the later stage of perfusion. In case 4, lactate levels increased at the initiation of the perfusion and remained at about 5 mmol/L at 3 hours after perfusion (

Figure 4B). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels increased in 4 cases at the initiation perfusion (

Figure 4C), which may be related to ischemia-reperfusion injury. The increase of the AST levels was the least in case 2. In case 1, the AST levels was gradually stable at 48 hours after perfusion, which may indicate that the liver was not further damaged. Additionally, no bacterial invasion was observed before and after NMP.

All these proved that Life-XDL machine perfusion system could provide a stable environment homeostasis for the diseased livers and the diseased livers had good viability and less damage during NMP.

3.4. Continuous bile production with good quality during NMP

Bile was produced in all the four diseased livers during perfusion. The case 1 began to produce bile, producing about 1-2ml per hour, with little volume and light color at 9 hours after perfusion, the case 2 began to produce small amounts of bile at 48 hours after perfusion, which lasted about an hour and stopped producing it, the case 3 produced bile throughout the machine perfusion period, the output was about 2ml per hour and the case 4 began to produce bile at 5 hours after perfusion with 1-2ml per hour with light color. The pH value of bile produced by the diseased liver of the 4 cases was almost maintained above 7.5 (

Figure 4D).

Overall, these data demonstrated maintenance and restoration of metabolism and bile production of the diseased livers by Life-XDL machine perfusion system.

3.5. Preserved architectural integrity during ex situ NMP of human diseased livers in macroscopic and microscopic evidence

The four diseased livers had homogeneous perfusion with soft consistency during entire perfusion (

Figure 2B). No obvious bleeding was observed in the appearance of the 4 diseased livers during NMP. The diseased livers did not appear mottled with parenchymal petechiae and the edge of the livers were ruddy and there was no obvious poor perfusion. HE staining analysis before and after NMP showed the liver tissue integrity was preserved and no further damage was observed in 4 diseased livers (

Figure 2C). There was no obvious intrahepatic thrombosis and no obvious congestion in hepatic sinusoid in all diseased livers. What’s more, in the tumor biopsies of cases 2 and 3, the tumor cells and histological structure were well preserved after NMP without significant damage (

Figure 2C). This indicated that Life-XDL machine perfusion system could effectively protect the diseased livers from damage during NMP.

4. Discussion

Due to the lack of models that can fully represent the physiopathological states of diseases and can be used to test potential treatments more accurately, the therapeutic field of liver diseases has developed extremely slowly. Here, we successfully modified the machine perfusion device to make it suitable for the human whole diseased liver and established human liver models of liver diseases model by perfusing human whole diseased livers recovered from recipients undergoing LT, demonstrating that human diseased livers could remain fully functional and viable outside of body in a stable and reproducible manner. We consider these achievements as a breakthrough that provides a novel tool to understand underlying mechanisms and treatment strategies for those “futile diseased liver” obtained from LT as well as opening up unexplored horizons for organ-based medicine.

Studies show that two-dimensional (2D) cell lines and animal models have been successfully applied in biomedical fields over the past 100 years for purposes such as clarifying the underlying pathological mechanisms of diseases and identify potential drug targets[

11]. However, 2D cell lines often disregard the interactions of cell-to-cell or cell-to-matrix interaction, and their natural system components[

12]. On the other hand, although animal models are better able to approximate the complex phenotypes in the body, the species differences between animals and humans make it difficult to translate relevant studies on animal models into bedside[

11]. Promising models like 3D culture systems termed “organoids” derived from primary tissues could self-renew, self-organize, differentiate and even faithfully mimic their genetic complexity[

13]. Nevertheless, owing to lacking stromal components and immune system, organoids could hardly reproduce heterogeneity, immune microenvironment and vascular network in vitro[

14]. So, what is the best model for medicine research? Long-term NMP preservation of organs seems to give us hope[

15].

NMP, which can offer nutrients and oxygen to the liver in an approaching physiological state, provides a unique opportunity for viability assessment and organ preservation. With NMP technology, we invented a novel transplant procedure of ischemia-free liver transplantation (IFLT), which yielded a better post-transplant prognosis and allowed the successful application of extended criteria donor[

16]. In addition, previous studies had shown that

NMP could enable human livers with normal function and organ architecture

to be successfully preserved in vitro for up to 12 days[

17]. Metabolic function (lactate clearance, pH maintenance), excretory function (bile production and bile composition), graft appearance, consistency, and hemodynamics (flow, pressure and resistance) can be used as important parameters to assess liver viability during NMP. Many studies have suggested that falling perfusate lactate levels are considered to be a sign of liver viability[

18,

19,

20]. Some studies believe that the lactate levels should remain at <2.5 mmol/L for a period of time before any transplant decision is made[

21]. Similarly, bile production is a unique function of the liver and well reflect the viability of liver, requiring the integrity of multiple cellular and metabolic components. In the present study, the lactate levels of diseased livers declined rapidly or kept a stable level during NMP, and all diseased livers continued producing bile with good quality. Moreover, hemodynamic stability of hepatic artery and portal vein is an important viability assessment of liver as well. Increased vascular resistance during machine perfusion has generally been considered to be a sign of poor liver viability[

22]. Most clinical NMP studies have included certain flow thresholds (>150 mL/minute for hepatic artery and >500 mL/minute for portal vein) as a key parameters of liver function[

17,

21], which are almost consistent with the

flow and pressure of hepatic artery and portal vein

observed in our study. Additionally, all diseased livers had homogeneous perfusion with soft consistency of parenchyma. Histological analysis further demonstrated the no or minimal reperfusion injury was observed in all diseased livers. Altogether, these results suggest that all diseased livers keep sustained function and viability during ex vivo NMP.

Because of the unique pathophysiology of the diseased liver, it is different from the normal liver. Patients with end-stage liver disease have poor coagulation function[

23] and may develop

severe hemolytic anemia[

24]

. The machine perfusion of the diseased liver had a high demand on blood, and hemolysis should try to be avoided during the perfusion. The

driving and operating parts of the magnetic driving centrifugal pump adopted permanent magnets, so that the flow rate was precisely controlled by controlling the rotational speed of the driving part of the motor. There was shown that the use of centrifugal pumps could significantly reduce hemolysis and the microemboli generation and preserve better platelet count[

25,

26]. In addition, thrombus or bubbles that form during machine perfusion could also be removed through two blood filter to reduce the residual impurities in the perfusate and reduce the risk of hemolysis. What’s more, the livers perfused on static systems support were often observed poor or heterogeneous perfusion of the hepatic parenchyma and

consecutive local pressure necrosis[

10,

27,

28]

. In liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer with cirrhosis, their liver parenchyma was replaced by fibrotic tissue and regenerating nodules, leading to portal hypertension[

29], which might result in the diseased livers being more susceptible to become inadequate marginal perfusion during perfusion. The perfusion machine did not mimic the diaphragm movement to make the liver move rhythmically as in other studies[

10], the silicone mat was improved to reduce the hepatic pressure and promote the hepatic marginal perfusion, which could be reflected from the low transaminase during entire machine perfusion. Besides, the microbiome and pro-inflammatory bacterial components contributed to the progression of liver diseases[

30]. The application of protective cover as well as antibiotics during NMP could keep the diseased liver in a aseptic condition.

Based on the NMP of human diseased livers, we can build up the personalized isolated organ research platform. The system provides an approaching physiological state of human liver, enabling to comprehensively study the pathophysiology of liver diseases. Furthermore, the controllable perfusate contents offers possibility to combine other therapies with Life-XDL. Several attempts have been made to add pharmacologic treatments during perfusion. Evidences showed that the addition of drugs like defatting cocktail with NMP was effective in reducing liver steatosis[

31,

32]. Furthermore, Sampaziotis et al. founded that the

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the circulating perfusate and tissue of organs could be downregulated and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection could be reduced ex vivo by systemic administrating the approved drug

ursodeoxycholic acid during machine perfusion[

33]. What’ more, NMP of diseased livers or other organs has the potential for benefits in the field of oncology, both with regard to research and therapeutics. The liver with carcinomas under NMP could even serve as a guide for personalized cancer therapeutics. HBV is a major cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, due to the narrow host range of HBV, which can only infect humans and chimpanzees, there is still a lack of related disease models with a complete immune response map[

32]. The combination of novel drugs with NMP for preclinical efficacy evaluation in cirrhosis and HCC is promising. Through our platform, it will be easier to screen out effective drugs for liver diseases, as well as to identify targeting markers of relevant therapeutic drugs through large-scale screening of diseased livers, so as to achieve individualized treatment for liver disease patients. In addition, the system could even be used for preclinical evaluation of drug hepatotoxicity. The liver is an important organ for drug accumulation, transformation and metabolism, and during the drug administration, the liver damage may occur due to the drug itself or/and its metabolites, which is called drug-induced liver injury (DILI). With our ex vivo liver models, the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of novel research and development drugs can be measured to help define the dose range of drugs, thereby reducing the occurrence of DILI in clinical trials.

Our experiences suggest that the substantial need of several technological improvements to achieve successful ex vivo NMP of diseased livers. Firstly, the resection process of diseased liver during LT induces various periods of warm ischemia, which is demonstrated by the increase in AST in initial stage of NMP. We developed a protocol that initially administers low perfusion pressures of hepatic artery and portal vein and slowly rewarms the diseased livers during the first period of perfusion in order to promote restitution of cellular homeostasis and reduce rewarming injury by upregulating of metabolism, which has been previously shown to have beneficial effects[

34,

35]. Secondly, the composition of perfusate need to be improved. For exemple, i

f the essential components like taurocholic acid of bile production were added to the perfusate, it was possible to improve the quantity and quality of bile production. What’s more, for each different disease liver, it may be necessary to add specific

perfusate contents to form a personalized perfusate for the diseased liver, which will more conducive to the maintenance of diseased liver. Thirdly, in order to further long-time machine perfusion of the diseased liver, some necessary devices like dialysis device may be added.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the first machine perfusion called Life-XDL special for human diseased livers and offers an important finding as establishing a novel model of human diseased liver and could provide opportunities for pharmacological, immunological and genetic research an interventions. This new research may have wider applications than those described herein and could potentially help to bridge the gap between basic medical science and clinical research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yunhua Tang, Jia Dan, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Data curation, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang, Honghui Chen, Huadi Chen, Tielong Wang, Maogen Chen, Weiqiang Ju, Dongping Wang, Zhiyong Guo and Jia Dan; Formal analysis, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang, Honghui Chen, Meiting Qin, Jinbo Huang, Ziqiang Miao, Ruilin Cai, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Funding acquisition, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Investigation, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang, Meiting Qin, Huadi Chen, Jun Kang, Hanqi Sun, Ronghua Zhong, Jingya Li, Weiqiang Ju, Dongping Wang, Zhiyong Guo, Jia Dan, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Methodology, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Honghui Chen, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Project administration, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Resources, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Yongqi Yang, Maogen Chen, Weiqiang Ju, Dongping Wang, Zhiyong Guo, Jia Dan, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Software, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang, Meiting Qin, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Supervision, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Validation, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang, Meiting Qin, Jia Dan, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Visualization, Yunhua Tang, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao; Writing – original draft, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Tao Zhang and Jia Dan; Writing – review & editing, Yunhua Tang, Jiahao Li, Jia Dan, Yefu Li, Xiaoshun He and Qiang Zhao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants as follows: the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170663, 82070670, 81970564, 81570587, 81700557 and 82270686), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory Construction Projection on Organ Donation and Transplant Immunology (2013A061401007 and 2017B030314018), Guangdong Provincial international Cooperation Base of Science and Technology (Organ Transplantation) (2015B050501002), Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Funds for Major Basic Science Culture Project (2015A030308010), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201704020150), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong province (2016A030310141 and 2020A1515010091), Guangdong Provincial Funds for High-end Medical Equipment (2020B1111140003), Young Teachers Training Project of Sun Yat-Sen University (K0401068) and Colin New Star of Sun Yat-Sen University (R08027).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the fndings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.V.; Haber, D.A.; Settleman, J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 2010, 10, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisowski, L.; Dane, A.P.; Chu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cunningham, S.C.; Wilson, E.M.; Nygaard, S.; Grompe, M.; Alexander, I.E.; Kay, M.A. Selection and evaluation of clinically relevant AAV variants in a xenograft liver model. Nature 2014, 506, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauschke, V.M.; Hendriks, D.F.; Bell, C.C.; Andersson, T.B.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Novel 3D Culture Systems for Studies of Human Liver Function and Assessments of the Hepatotoxicity of Drugs and Drug Candidates. Chem Res Toxicol 2016, 29, 1936–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.C.; Dankers, A.; Lauschke, V.M.; Sison-Young, R.; Jenkins, R.; Rowe, C.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, K.; Regan, S.L.; Walker, T.; et al. Comparison of Hepatic 2D Sandwich Cultures and 3D Spheroids for Long-term Toxicity Applications: A Multicenter Study. Toxicol Sci 2018, 162, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Knutsdottir, H.; Hui, K.; Weiss, M.J.; He, J.; Philosophe, B.; Cameron, A.M.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Pawlik, T.M.; Ghiaur, G.; et al. Human primary liver cancer organoids reveal intratumor and interpatient drug response heterogeneity. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascaris, B.; de Meijer, V.E.; Porte, R.J. Normothermic liver machine perfusion as a dynamic platform for regenerative purposes: What does the future have in store for us? J Hepatol 2022, 77, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasralla, D.; Coussios, C.C.; Mergental, H.; Akhtar, M.Z.; Butler, A.J.; Ceresa, C.; Chiocchia, V.; Dutton, S.J.; Garcia-Valdecasas, J.C.; Heaton, N.; et al. A randomized trial of normothermic preservation in liver transplantation. Nature 2018, 557, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecki, H.; Bozorgzadeh, A.; Porte, R.J.; Leuvenink, H.G.; Uygun, K.; Martins, P.N. Liver ex situ machine perfusion preservation: A review of the methodology and results of large animal studies and clinical trials. Liver Transpl 2017, 23, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshmuminov, D.; Becker, D.; Bautista, B.L.; Hefti, M.; Schuler, M.J.; Hagedorn, C.; Muller, X.; Mueller, M.; Onder, C.; Graf, R.; et al. An integrated perfusion machine preserves injured human livers for 1 week. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Chu, C.; Hong, Y.; Tao, M.; Hu, H.; Xu, M.; Guo, X.; et al. Human organoids in basic research and clinical applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahwiler, B.H.; Capogna, M.; Debanne, D.; McKinney, R.A.; Thompson, S.M. Organotypic slice cultures: a technique has come of age. Trends Neurosci 1997, 20, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broutier, L.; Mastrogiovanni, G.; Verstegen, M.M.; Francies, H.E.; Gavarro, L.M.; Bradshaw, C.R.; Allen, G.E.; Arnes-Benito, R.; Sidorova, O.; Gaspersz, M.P.; et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nat Med 2017, 23, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuveson, D.; Clevers, H. , Cancer modeling meets human organoid technology. Science 2019, 364, 952–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefler, J.; Marfil-Garza, B.A.; Dadheech, N.; Shapiro, A. Machine Perfusion of the Liver: Applications Beyond Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Ischaemia-free liver transplantation in humans: a first-in-human trial. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021, 16, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.S.; Ly, M.; Dennis, C.; Liu, K.; Kench, J.; Crawford, M.; Pulitano, C. Long-term normothermic perfusion of human livers for longer than 12 days. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 2504–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.S.; Ly, M.; Dennis, C.; Liu, K.; Kench, J.; Crawford, M.; Pulitano, C. Long-term normothermic perfusion of human livers for longer than 12 days. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 2504–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.C.; Reyner, E.; Molina, V.; Garcia, R.; Ruiz, A.; Roque, R.; Diaz, A.; Fuster, J.; Garcia-Valdecasas, J.C. Evolution Under Normothermic Machine Perfusion of Type 2 Donation After Cardiac Death Livers Discarded as Nontransplantable. J Surg Res 2019, 235, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Y.; Matton, A.; Nijsten, M.; Werner, M.; van den Berg, A.P.; de Boer, M.T.; Buis, C.I.; Fujiyoshi, M.; de Kleine, R.; van Leeuwen, O.B.; et al. Pretransplant sequential hypo- and normothermic machine perfusion of suboptimal livers donated after circulatory death using a hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier perfusion solution. Am J Transplant 2019, 19, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergental, H.; Laing, R.W.; Kirkham, A.J.; Perera, M.; Boteon, Y.L.; Attard, J.; Barton, D.; Curbishley, S.; Wilkhu, M.; Neil, D.; et al. Transplantation of discarded livers following viability testing with normothermic machine perfusion. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monbaliu, D.; Liu, Q.; Libbrecht, L.; De Vos, R.; Vekemans, K.; Debbaut, C.; Detry, O.; Roskams, T.; van Pelt, J.; Pirenne, J. Preserving the morphology and evaluating the quality of liver grafts by hypothermic machine perfusion: a proof-of-concept study using discarded human livers. Liver Transpl 2012, 18, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amitrano, L.; Guardascione, M.A.; Brancaccio, V.; Balzano, A. Coagulation disorders in liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 2002, 22, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgard, P.; Schreiter, T.; Stockert, R.J.; Gerken, G.; Treichel, U. Asialoglycoprotein receptor facilitates hemolysis in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, I.S.; Codispoti, M.; Sanger, K.; Mankad, P.S. Superiority of centrifugal pump over roller pump in paediatric cardiac surgery: prospective randomised trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998, 13, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, O.; Fosse, E.; Dregelid, E.; Brockmeier, V.; Andersson, C.; Hogasen, K.; Venge, P.; Mollnes, T.E.; Kierulf, P. Centrifugal pump and heparin coating improves cardiopulmonary bypass biocompatibility. Ann Thorac Surg 1996, 62, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Nassar, A.; Buccini, L.; Grady, P.; Soliman, B.; Hassan, A.; Pezzati, D.; Iuppa, G.; Diago, U.T.; Miller, C.; et al. Ex situ 86-hour liver perfusion: Pushing the boundary of organ preservation. Liver Transpl 2018, 24, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshmuminov, D.; Leoni, F.; Schneider, M.A.; Becker, D.; Muller, X.; Onder, C.; Hefti, M.; Schuler, M.J.; Dutkowski, P.; Graf, R.; et al. Perfusion settings and additives in liver normothermic machine perfusion with red blood cells as oxygen carrier. A systematic review of human and porcine perfusion protocols. Transpl Int 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gines, P.; Krag, A.; Abraldes, J.G.; Sola, E.; Fabrellas, N.; Kamath, P.S. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2021, 398, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.; Gerard, P. The links between the gut microbiome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrath, D.; Xu, H.; Tanimura, Y.; Zuo, R.; Berthiaume, F.; Avila, M.; Yarmush, R.; Yarmush, M.L. Metabolic preconditioning of donor organs: defatting fatty livers by normothermic perfusion ex vivo. Metab Eng 2009, 11, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, R.W.; Zilvetti, M.; Roy, D.; Hughes, D.; Morovat, A.; Coussios, C.C.; Friend, P.J. Hepatic steatosis and normothermic perfusion-preliminary experiments in a porcine model. Transplantation 2011, 92, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevini, T.; Maes, M.; Webb, G.J.; John, B.V.; Fuchs, C.D.; Buescher, G.; Wang, L.; Griffiths, C.; Brown, M.L.; Scott, W.R.; et al. FXR inhibition may protect from SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing ACE2. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minor, T.; von Horn, C.; Zlatev, H.; Saner, F.; Grawe, M.; Luer, B.; Huessler, E.M.; Kuklik, N.; Paul, A. Controlled oxygenated rewarming as novel end-ischemic therapy for cold stored liver grafts. A randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Sci 2022, 15, 2918–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecki, H.; Bozorgzadeh, A.; Porte, R.J.; Leuvenink, H.G.; Uygun, K.; Martins, P.N. Liver ex situ machine perfusion preservation: A review of the methodology and results of large animal studies and clinical trials. Liver Transpl 2017, 23, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).