Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Simulation Modelling for Ex-Ante Assessment

-

Discrete Event Simulation (DES): A Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) model is a model of a system in which events occur at specific points in time, causing changes in the system state [9]. A DES model consists of:

- –

- Discrete-event: the discrete event is the cause of the system state change. The state of the system in the DES model only changes due to the occurrence of events [10]. For example, in a hospital DES model, the patient’s walking distance in the hospital only changes if the patient moves to the next room.

- –

- Clock: The clock records the duration of the simulation. The DES model is dynamic as time is a critical variable, i.e., the state variables of the system change over simulation time [10]. For example, in a hospital DES model, the walking distance of the patient increases as the simulation time increases.

- –

- Random number generators: A random number generator can generate random variables for the DES [10], e.g., medical service time or patient inter-arrival rate.

- –

- Statistics: It summarises the results of the simulation such as average patient waiting time or average patient walking distance [10].

- –

- Ending Condition: The DES ends when the ending condition is met [10]. E.g., a hospital DES model is set to end when a certain number of patients are discharged.

The proposed HDSS can use DES to simulate patients’ medical procedures in hospitals and predict hospital performance by calculating performance indicators such as people density, patient waiting time, patient walking distance, etc. -

Agent-Based Modelling (ABM): An Agent-Based Model consists of agents and interactions between agents and between agents and the environment [11]. Agents are small computer programs that represent various types of entities [11]. For example, in a hospital ABM model, agents can be patients, nurses, doctors, etc. The environment in the ABM model can be a network graph where agents can interact [11]. The agents have several characters which are summarised as follows:

- –

- Autonomy: agents are autonomous entities that behave without guidance from central controllers, they are capable of making independent decisions [12].

- –

- Heterogeneity: agents can have various features such as ages, jobs, genders, etc [12]. For example, in a hospital ABM model, agents can have different roles such as patients, medical staff, technical staff, etc.

- –

- Active: agents are active in an ABM model because they are goal-directed, they are assigned to different goals and they need to achieve them [12]. To achieve their goals, agents are equipped with the capacity to perceive their environment and interact with other agents. Additionally, they are enabled to make logical decisions that facilitate goal attainment [12].

- –

- Interactive: agents can interact with other agents and also with the environment [12].

- –

- mobility: agents can move in the ABM environment [12]. For instance, the patient or the staff agent of a hospital ABM model can move in the environment (i.e., a graph) to achieve their goals.

- –

- Adaptation/Learning: agents can be designed to be adaptive, they can alter their states based on previous states [12]. For instance, in a hospital agent-based model, a doctor agent becomes available for new patients once they have completed treatment of the current patient.

ABM can also be applied in the proposed HDSS for studying individual behaviours, interactions between patients and staff, or patient flows in the hospital. -

Continuous Simulation: Continuous simulations are designed to model systems in which the system states change continuously over time. For example, in a hospital continuous simulation model, the patient’s length of stay increases continuously over simulation time. Continuous simulation models use differential equations or other mathematical models for defining the changing rate of the system states over time [13].Continuous simulations can be compared with DES, where state variables in continuous simulation models change continuously over time, while in DES models it changes at distinct points in time. Continuous simulations can be used for studying the spread of a contagious airborne disease (e.g., influenza or COVID-19) throughout a hospital to understand infection risk in different areas.

-

System Dynamics: System Dynamics is a type of continuous simulation that is developed for supporting policy making in complex and dynamic systems [13]. In system dynamics models, the behaviour of the system is created by the interactions between different components over time. The key components of a system dynamics model are introduced in the following:

- –

- Stocks: Stocks are accumulations of resources in a system, they represent the state of the system. [13], e.g., the number of patients in a hospital.

- –

- Flows: Flows represent the changing rates of stocks over time [13]. In a hospital, for example, the flow could be the rate at which new patients are admitted or discharged.

- –

- Information links: in a system dynamics model, information links connect stocks with flows and transfer information from a stock to the flow, it defines how a stock influences the values of the flow [13]. For example, in a hospital system dynamics model, by linking stock (i.e., number of patients in the hospital) to the flow (i.e., patient inter-arrival rate), the patient inter-arrival rate can be influenced by the current number of patients in the hospital.

System Dynamics can be applied in hospital management in terms of understanding patient flow, resource allocation, the spread of disease, etc.

2.2. Operational vs. Spatial Information

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Use Cases of HDSS

- Use case 1: The architect can use the HDSS to semi-automatically create a hospital layout at the layout design stage of a new project, or optimize the hospital layout of an existing project. For this use case, the operational information of patients’ medical procedures in the hospital is needed for obtaining an Activity Relations Charts (ARC) Model (for further explanations please see Section 3.2). Thus, the HCM should contain the operational information on patients’ medical procedures in the hospital.

- Use case 2: The Architect can use this HDSS to assess the safety of the hospital environment during the layout design stage. The environment’s safety can be measured by the visibility and accessibility of spatial units within the hospital. As the visibility increases, the nurse can supervise bigger areas and hence the safety of the environment is also improved. A network graph consisting of nodes and edges is needed for this function, where each node represents a spatial unit of the hospital and each edge connecting two nodes represents the adjacent relationship between the two nodes. Hence, the HCM of the HDSS should contain the topological information of a network graph.

- Use case 3: The hospital director can use HDSS to check if the hospital will be overcrowded during the layout design stage. For this use case, we need the topological information of the network graph, we also need to incorporate semantic information into the graph by assigning the area of each spatial unit to its corresponding node, so that the average people density in the room/spatial unit can be computed to indicate the crowdedness.

- Use case 4: The hospital director can use this system to check if the patient waiting time will be too long in a new hospital project during the layout design stage. In this use case, the graph is again needed, we also need to integrate semantic information into the graph by assigning the name of each spatial unit (e.g., `central waiting’ or `registration’, etc.) to its corresponding node. The patient’s waiting time will be from the time the patient enters the waiting room till the time the patient enters the diagnosis room.

- Use case 5: The head nurse can use this system to check if patients’ walking distances will be too long in a new hospital project during the layout design stage. For this use case, we need the operational information of patients’ medical procedures for obtaining the optimal patient paths with the shortest distance. We also need the topological information of the network graph of the hospital. Furthermore, it is necessary to incorporate semantic information into the graph by assigning the name of each spatial unit to its corresponding node. This will enable the identification of specific patient paths within the graph. Finally, it is essential to integrate geometric information into the graph by assigning 3D coordinates to each node. This will allow for the calculation of the distances along the patient’s path.

- Use case 6: The architect can use this system to check how difficult it will be for first-time visitors to find their way in a hospital project during the layout design stage. For this function of measuring the difficulty in wayfinding, the extra walking distance will be the criteria of measurement. Hospital space is large and complicated, when first-time visitors enter the hospital to look for their destinations, they might get lost and go to several wrong places before arriving at their destinations. Hence their actual travel journey will be different from the optimal journey (i.e., the shortest path), the difference between the shortest path’s distance and the patient’s actual travel journey’s distance will indicate how difficult it is for patients to find their way. This use case requires the same information as the use case 5.

- Use case 7: The hospital director can use this system to develop a digital twin for simulating the operational management of the existing hospital during the operation and maintenance stage. A digital twin can help hospital directors assess the impact of changes on system performance and predict the result of specific medical procedures [16]. For this use case, the needed information is the topological information of the hospital graph and the operational information such as the patient journey.

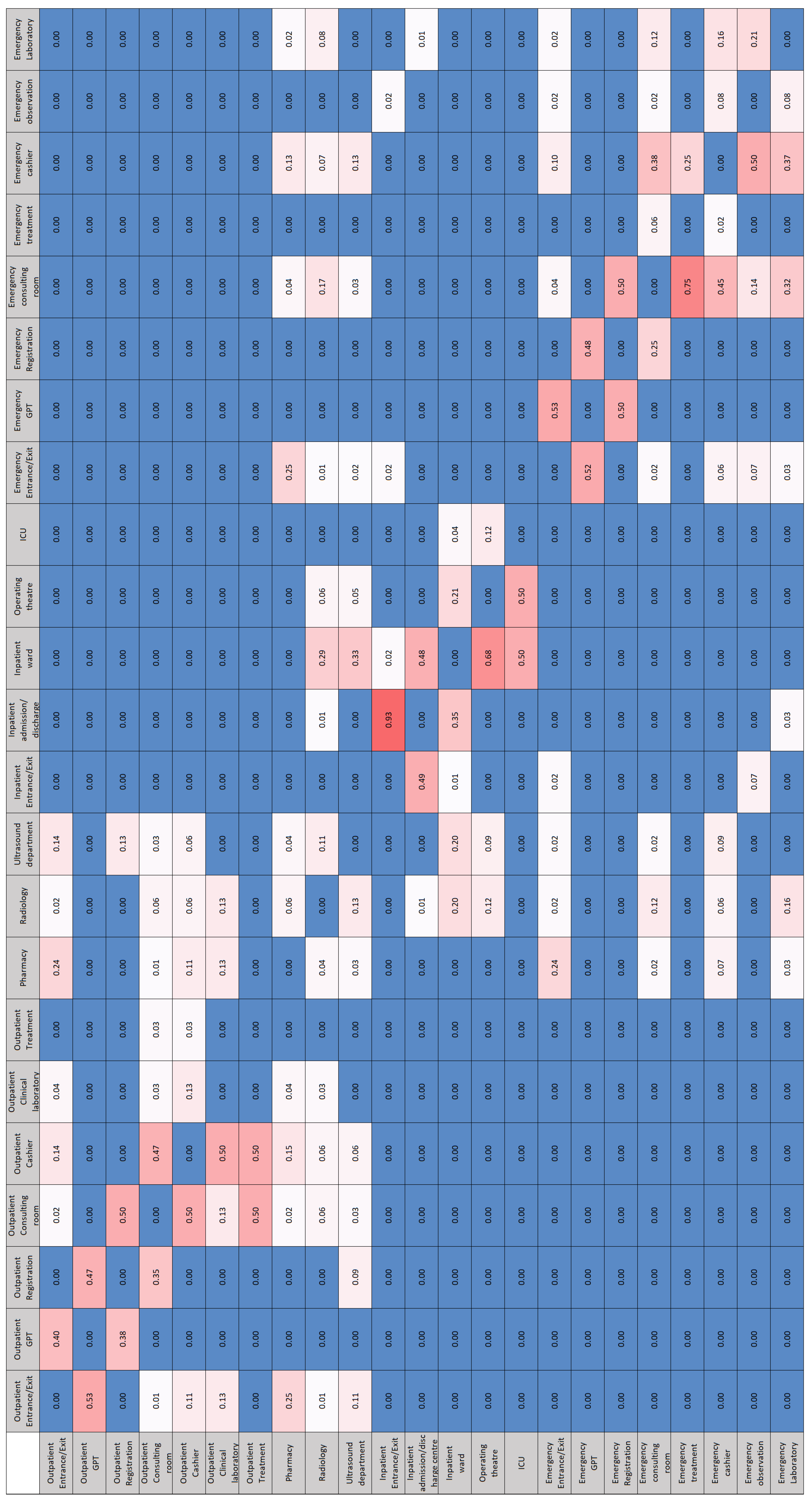

3.2. ARC Model

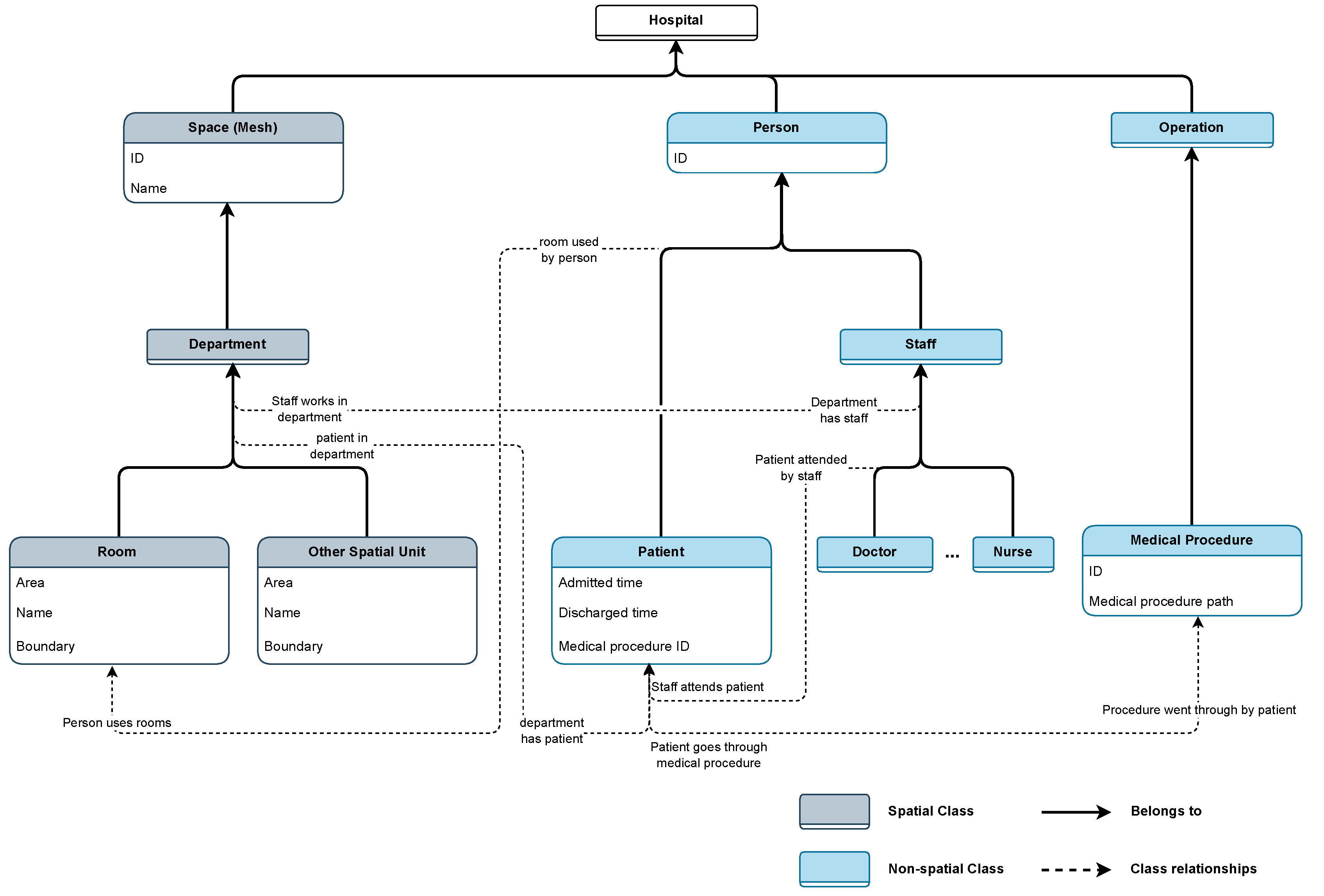

3.3. Hospital Configuration Model

4. Proposal

4.1. Hospital BIM and IFC Models

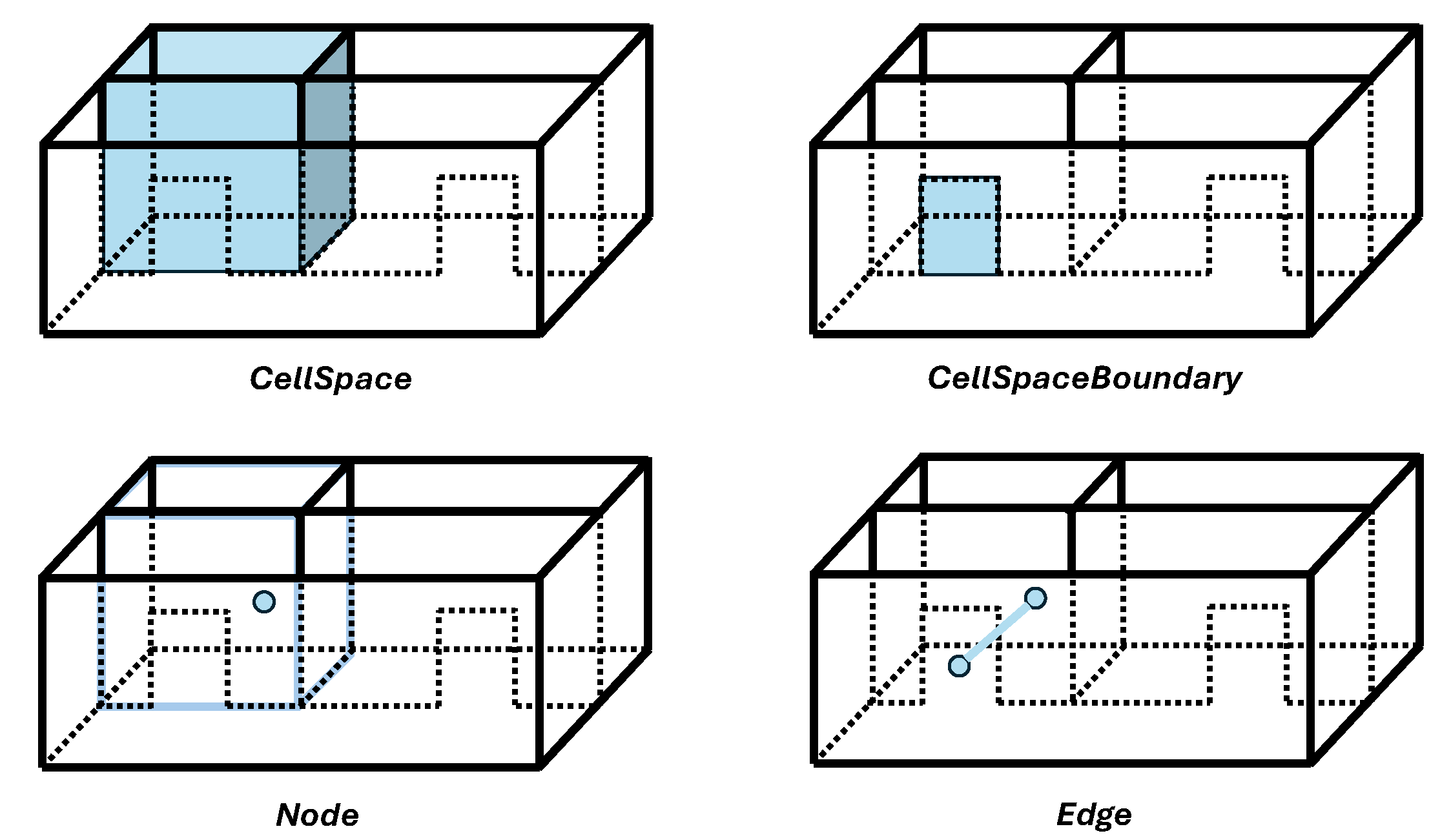

4.2. IndoorGML

- There is a lack of available IndoorGML files in the industry because according to the literature study conducted in Section 4.4.1, there are no appropriate tools for generating correct IndooGML files. Furthermore, IndoorGMLs are encoded in XML (eXtensible Markup Language) format [?], which is complex, highly hierarchical, cumbersome to manage, and unpopular for web applications [21].

- While IndoorGML is designed to support applications in indoor navigation and facility management, effective execution of these tasks typically requires integration with additional data, such as operational information and enriched semantic information. However, IndoorGML files currently face the challenge of lacking this critical supplementary information.

4.3. Hospital BPMN Models

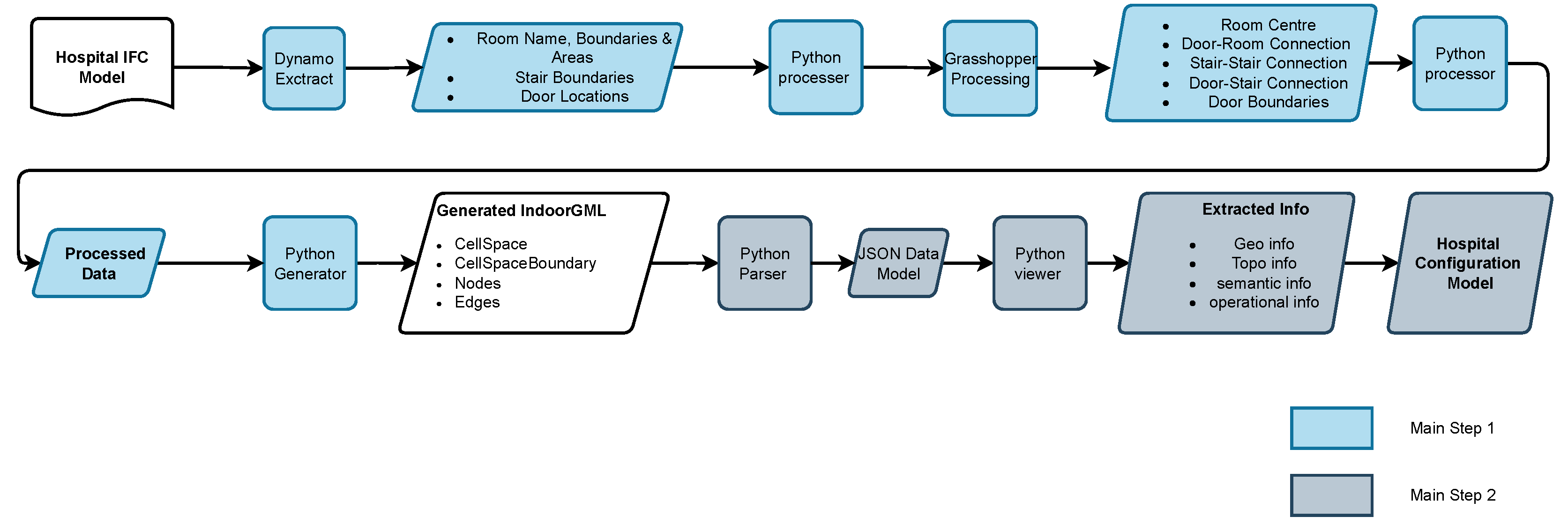

4.4. From Hospital IFC Model to HCM

4.4.1. From IFC to IndoorGML

4.4.2. From IndoorGML to HCM

-

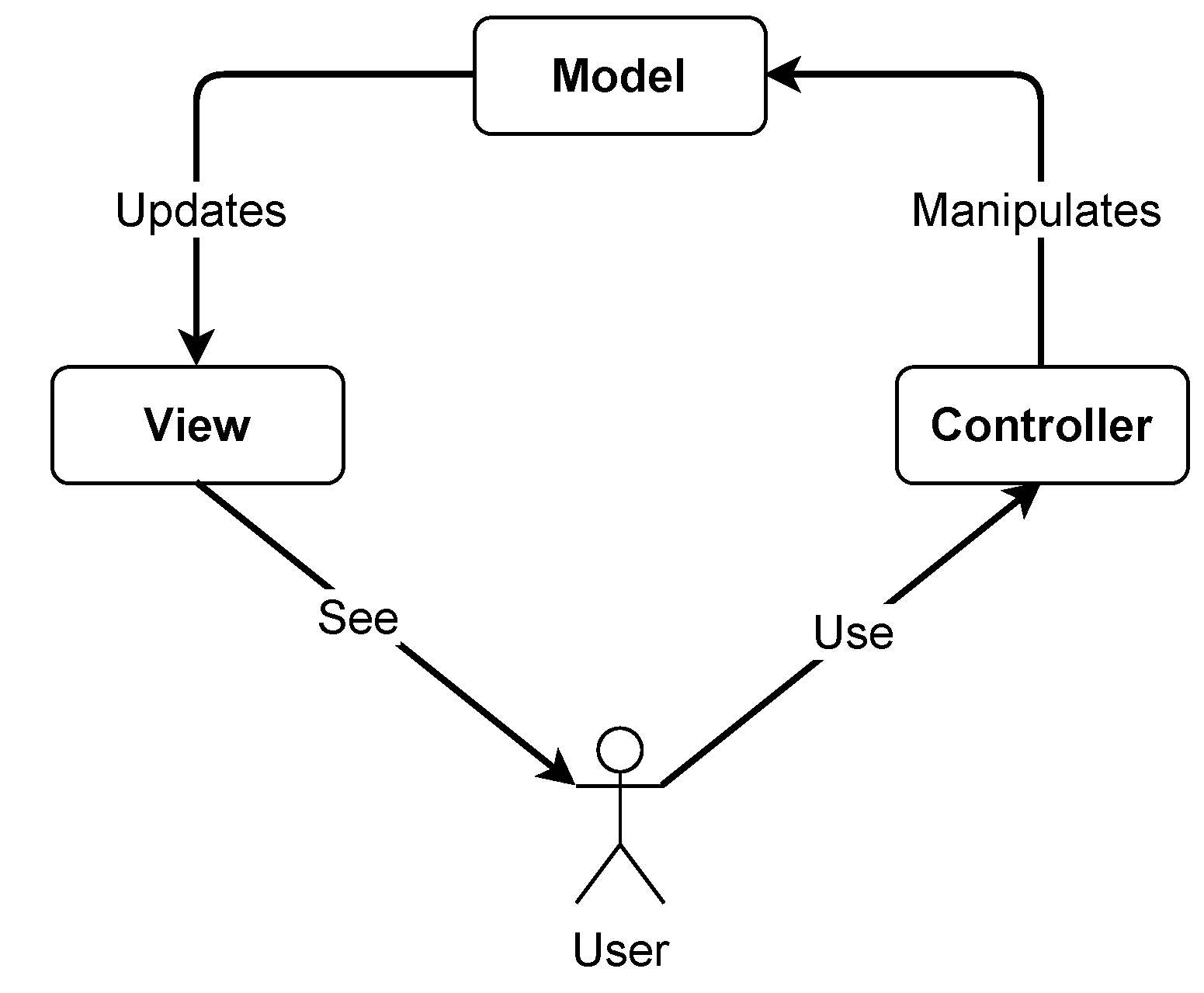

Obtaining the Model part of the HCMFigure 9 shows that the development of the data model for the HCM includes parsing the IndoorGML file into a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file [?]. The parser for IndoorGML used in this study is developed by Ledoux [28]. With this parser, all the information in the IndoorGML (e.g., cell spaces, cell space boundaries, nodes and edges) is parsed into a JSON file as the data model.

-

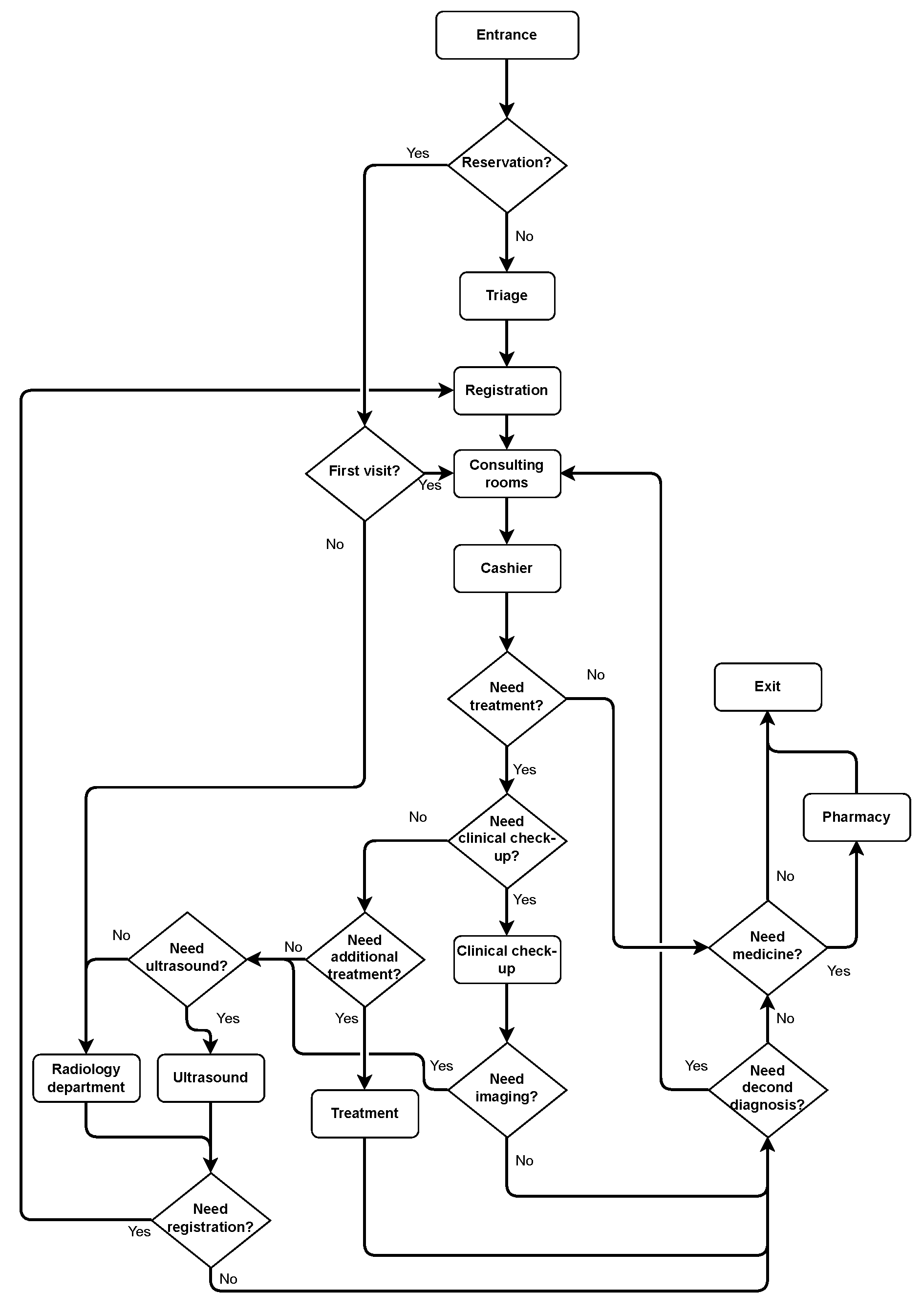

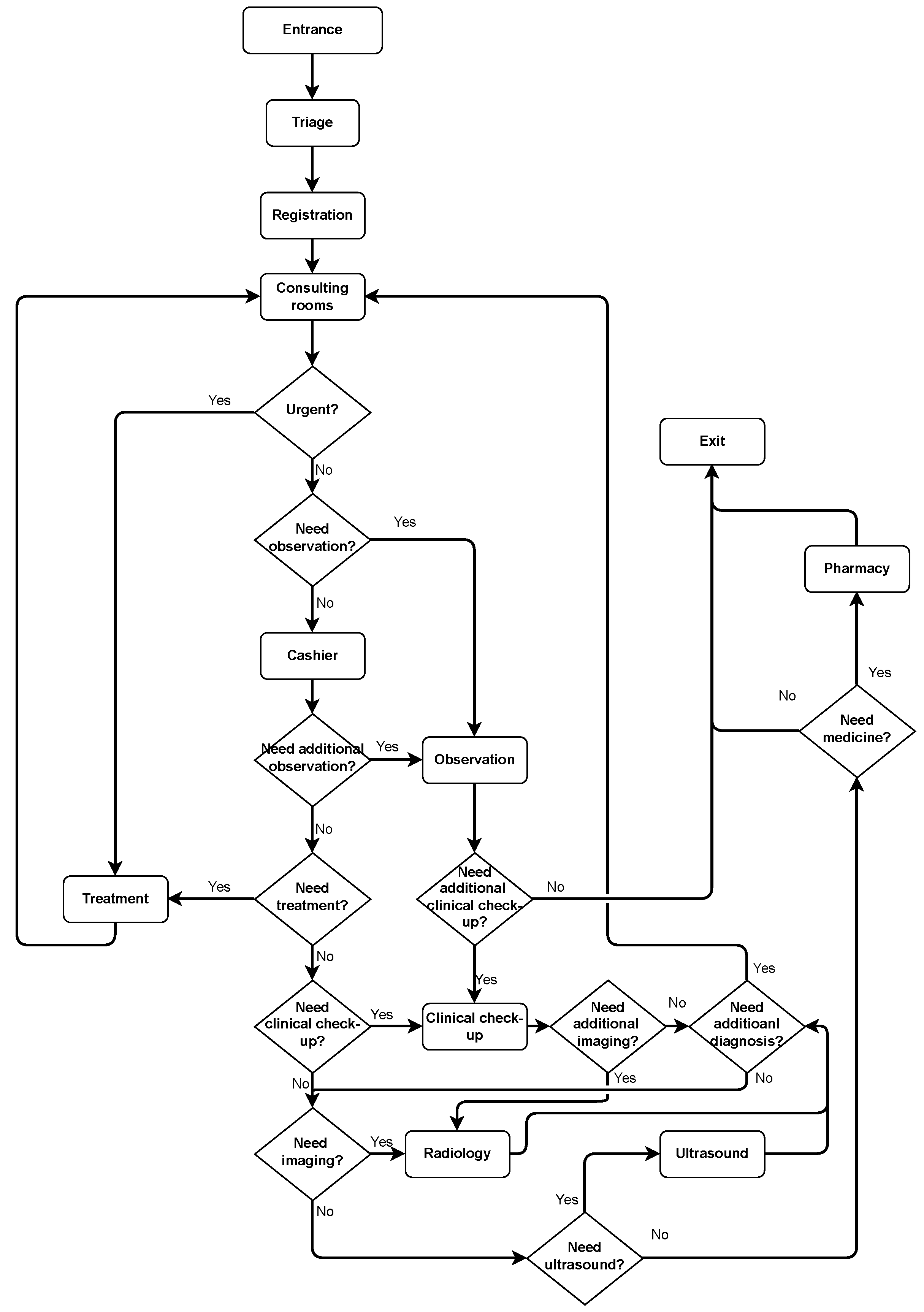

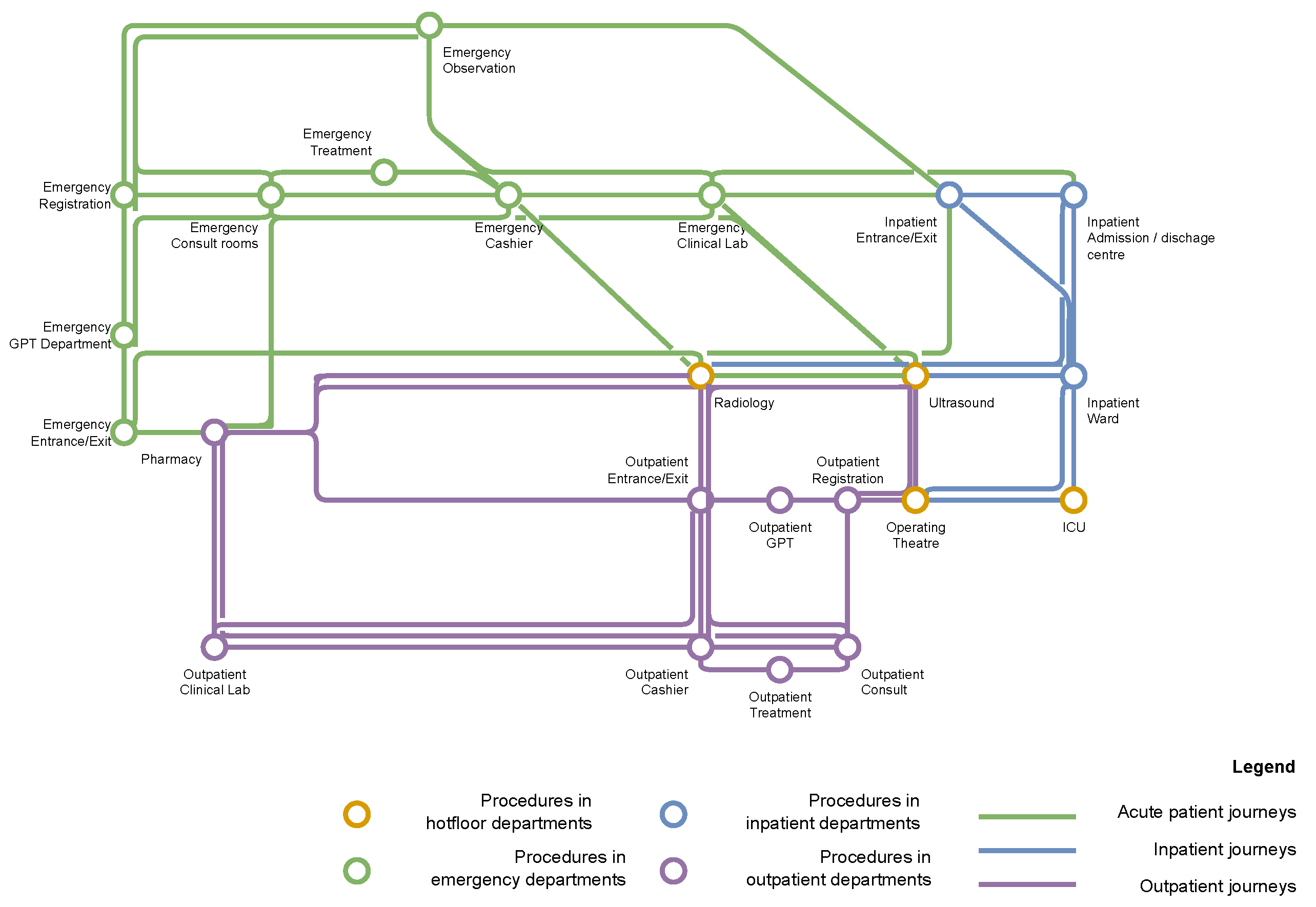

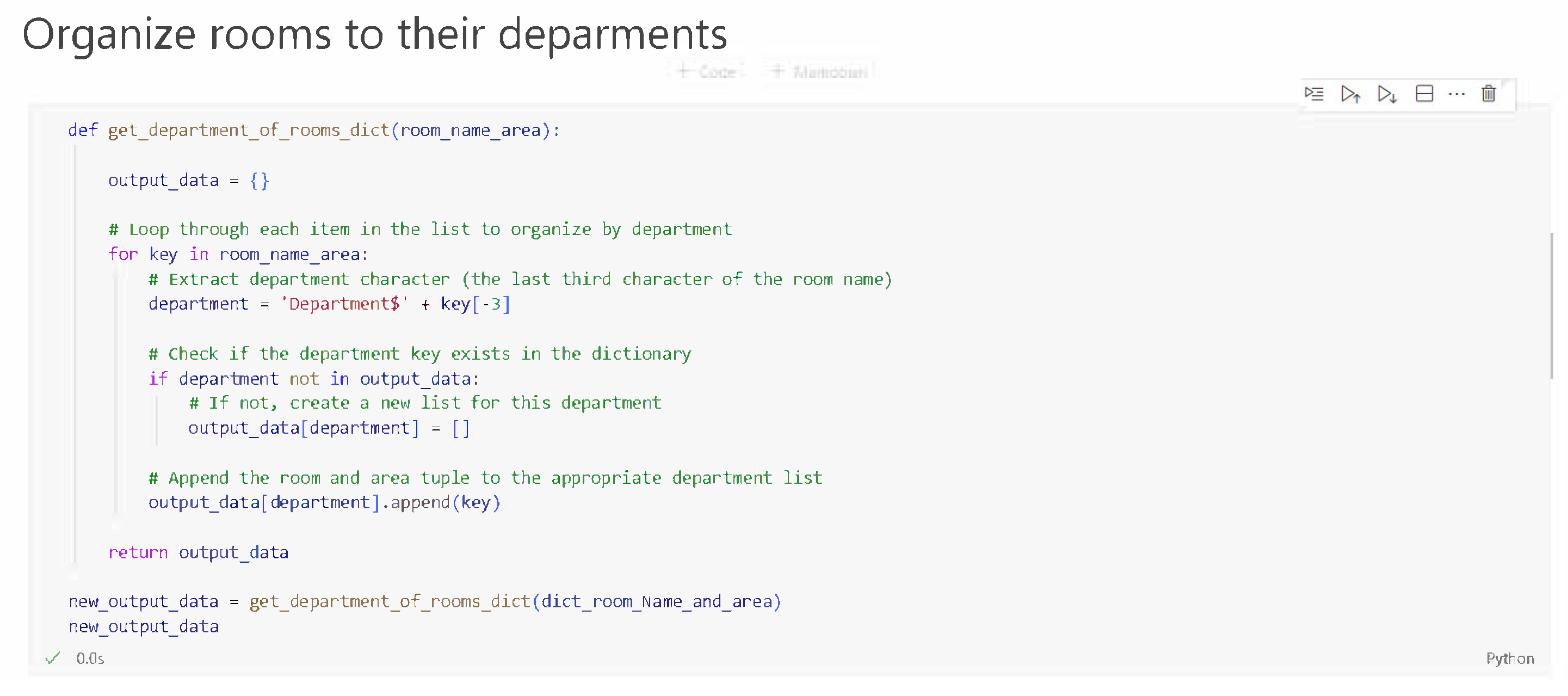

Developing the View part of the HCMThe information presented by the view codes should be a mathematical construct about sets and relations, these relations are graphs, so most of our view functions should output sets and graphs or hyper-graphs (Mesh is a hyper-graph and the edge in a face is considered to be a hyper-edge). According to the use cases demonstrated in Section 3.1, we developed view codes to extract the following information: a mesh (hyper-graph) describing the geometrical information (i.e., the PrimalSpaceFeatures) in the IndoorGML model, a graph showing the topological information (i.e., the Node-Relation Graph) in the IndoorGML model, a set of room names and room areas showing the semantic information of the hospital in the IndoorGML model, and another set of hospital departments and all the rooms within their respective departments, which shows the semantic information of the hospital’s organizational structure. Last but not least, a set of lists demonstrating the operational information of patient journeys in the hospital.The mesh output is obtained using the COMPAS library in Python, COMPAS is an open-source framework designed for computational research in the field of architecture, engineering, digital fabrication and construction [29]. Users can use the view code to generate and visualize the mesh geometry to get a view of how the IndoorGML model of the building looks like. The graph output is obtained by developing Python scripts using the NetworkX library, a Python package made for creating, manipulating, and analysing complex networks[30]. Users can use the view code to obtain the network graph which will be the base for running the simulation modeling. The simulaiton modeling is one of the core functionalities of HDSS as mentioned in use cases 4, 5, and 6. Figure 8 is a visualization of the mesh output and graph output generated from the open-source hospital IFC model [?], where the red graph is embedded in the transparent mesh. The set output of room names and room areas is a Python dictionary [?], where the room name is the key and the room area is the value. Users can use the view code to obtain all the room areas, which can aid in addressing use case 3. Specifically, in the later simulation modelling step, once the room area and the number of people in the room are known, it will be straightforward to assess the room’s crowdedness by calculating the people’s density in the room. The set output of departments and rooms is also a Python dictionary, where the key is each department in the hospital, and the value is the group of all rooms included in the department. Figure 11 shows the Python code to implement this function of organizing all rooms in the hospital into their respective departments and Table 2 shows the resulting Python dictionary of hospital departments and rooms. The extracted operational information related to patient journeys in the hospital are Python lists. For extracting this information, we first turned the BPMN models (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) into multiple lists (e.g., see Input data list in Table 3), where each element in the list is a space-related procedure in the BPMN (i.e., rounded-corner rectangle in the flow charts Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3), and the entire list is a complete medical procedure in the BPMN flow chart (i.e., the procedure starts with patient entering the hospital and ends with patient leaving hospital). Subsequently, we developed view codes to identify the corresponding room names of list elements based on the extracted semantic information of hospital departments and rooms (Table 2). For example, the element `registration’s’ corresponding room name in the semantic information Dictionary is `RECEPTION1B13’. The view codes find the corresponding room names for each element in the list and put all corresponding room names into a new list (e.g., see Output data list in Table 3). The new lists contain extracted operational data on patient journeys, which can serve as input for HDSS simulation modelling, e.g., this data enables determining the shortest path for patients/agents in DES or ABM simulations. Table 3 provides an example of the input data list generated from the BPMN model and an example of the output data list of operational information generated from the input data list. It is to be noticed that one element in the input data list might have multiple corresponding room names in the output data list, this is because in a hospital there can be multiple rooms for the same function. For example, the element `diagnosis’ in the input list has twelve corresponding room names (`INTERACTIONSTATION1D07’, `INTERACTIONSTATION1D08’, etc.) in the output data list because, in the selected hospital BIM model, there are twelve rooms all serving the same function of diagnosis. Hence, the patient can have twelve options when choosing the diagnosis room and there will be twelve different potential paths for the patient to complete the same patient journey. For more implementation details of the view codes’ Python scripts please refer to this paper [23] or this repository.

-

The Controller part of the HCMThe controller codes we envisage are for updating the data model, in other words, adding/changing information to the data model. Once the simulation is complete, we need to update the data model by adding the dis-aggregated simulation results and aggregated evaluation results to the data model, so that users can easily view them. For example, once the simulation is finished and we know each room’s people density, we need to add this attribute to the dictionary that describes the room’s information. Table 4 provides an example for illustrating how one part of the data model has been changed before and after the controller code adds information to it. Besides adding the dis-aggregated information, we also propose controller codes for adding aggregated information such as average people density, average patient walking distance, average patient waiting time and average patient’s extra walking distance.Another example of controller code is for updating the data model’s network graph. The original network graph only contains topological information, the controller codes can integrate semantic and geometric information into the graph. For example, assigning each node its corresponding room name, area, and 3D coordinate. By adding such information to the graph, the graph can aid in the simulation modelling such as finding the shortest path in the graph according to the patient journey data list (output data list in Table 3), calculating the distance along the shortest path, and calculating the people density in a room.

5. Discussion

5.1. Future Research

5.2. The Utilization Outlook of HCMs

- An HCM can be used for space optimization by providing the basis to study relationships and flows between different space units.

- Together with the operational information, an HCM can be used as a digital twin for simulating and monitoring the daily operations of a hospital, e.g. in operational management and in facility management

- An HCM can help improve the safety of a building by optimizing the placement of guards or cameras to ensure maximum coverage while keeping the lowest number of guards/cameras within the building.

- An HCM can be augmented with 3D information (after the hospital is realized) to help build a model for indoor navigation and way-finding.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDSS | Hospital Design Support System |

| HCM | Hospital Configuration Model |

| DES | Discrete-Event Simulation |

| ABM | Agent-Based Modelling |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| ARC | Activity Relations Charts |

| BPMN | Business Process Model Notation |

| MVC | Model-View-COntroller |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

References

- Jia, Z.; Nourian, P.; Luscuere, P.; Wagenaar, C. Spatial decision support systems for hospital layout design: A review. 67, 106042. [CrossRef]

- Chraibi, A.; Kharraja, S.; Osman, I.; El Beqqali, O. A Mixed Integer Programming formulation for solving Operating Theatre Layout Problem: a Multi-goal Approach. Journal Abbreviation: Proceedings of 2013 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Systems Management, IEEE - IESM 2013 Publication Title: Proceedings of 2013 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Systems Management, IEEE - IESM 2013.

- Ulrich, R.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A.; Choudhary, R.; Zimring, C. The Role of the Physical Environment in the Hospital of the 21 st Century: A Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity.

- Burgio, L.D.; Engel, B.T.; Hawkins, A.; McCormick, K.; Scheve, A. A Descriptive Analysis of Nursing Staff Behaviors in a Teaching Nursing Home: Differences Among NAs, LPNs, and RNs. 30, 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Peponis, J.; Zimring, C.; Choi, Y.K. Finding the Building in Wayfinding. 22, 555–590SAGE Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharaa, A.; Adam, M.; Amer Nordin, A.S.; Mundher, R.; Alhasan, A. Assessment of Wayfinding Performance in Complex Healthcare Facilities: A Conceptual Framework. 14, 16581, Number: 24 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Verderber, S. On the Planning and Design of Hospital Circulation Zones. 10, 124–146. [CrossRef]

- Pouyan, A.E.; Ghanbaran, A.; Shakibamanesh, A. Impact of circulation complexity on hospital wayfinding behavior (Case study: Milad 1000-bed hospital, Tehran, Iran). 44, 102931. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, F.S.; Lieberman, G.J. Introduction to operations research, tenth edition ed.; McGraw-Hill Education. Section: xxx, 1010 pages : illustrations ; 27 cm.

- Leemis, L.M.; Park, S.K. Discrete-event Simulation: A First Course; Pearson Prentice Hall. Google-Books-ID: UDwZAQAAIAAJ.

- Elsenbroich, C.; Gilbert, N. Agent-Based Modelling. In Modelling Norms; Elsenbroich, C.; Gilbert, N., Eds.; Springer Netherlands; pp. 65–84. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, A.T.; Heppenstall, A.J. Introduction to Agent-Based Modelling. In Agent-Based Models of Geographical Systems; Heppenstall, A.J.; Crooks, A.T.; See, L.M.; Batty, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands; pp. 85–105. [CrossRef]

- Law, A.M. Simulation Modeling and Analysis; McGraw-Hill. Google-Books-ID: 6cC_QgAACAAJ.

- Documentation, S. Simulation and Model-Based Design.

- Modelica Association. Modelica Language Specification.

- Semeraro, C.; Lezoche, M.; Panetto, H.; Dassisti, M. Digital twin paradigm: A systematic literature review. 130, 103469. [CrossRef]

- Gozali, L.; Widodo, L.; Nasution, S.; Lim, N. Planning the New Factory Layout of PT Hartekprima Listrindo using Systematic Layout Planning (SLP) Method Planning the New Factory Layout of PT Hartekprima Listrindo using Systematic Layout Planning (SLP) Method; Vol. 847. Journal Abbreviation: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering Publication Title: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Cubukcuoglu, C.; Nourian, P.; Tasgetiren, M.F.; Sariyildiz, I.S.; Azadi, S. Hospital layout design renovation as a Quadratic Assignment Problem with geodesic distances. 44, 102952. [CrossRef]

- çubukçuoğlu, C.; Nourian, P.; Sariyildiz, I.; Tasgetiren, M. Optimal Design of new Hospitals: A Computational Workflow for Stacking, Zoning, and Routing. 134, 104102. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.; Garcia, F.; Calahorra, L.; Llorente, C.; Gonçalves, L.; Daniel, C.; Blobel, B. Business process modeling in healthcare. 179, 75–87.

- Ohori, K.A.; Ledoux, H.; Peters, R. 3D modelling of the built environment.

- Diakite, A.A.; Díaz-Vilariño, L.; Biljecki, F.; Isikdag, Ü.; Simmons, S.; Li, K.; Zlatanova, S. IFC2INDOORGML: AN OPEN-SOURCE TOOL FOR GENERATING INDOORGML FROM IFC. XLIII-B4-2022, 295–301. Conference Name: XXIV ISPRS Congress “Imaging today, foreseeing tomorrow”, Commission IV - 2022 edition, 6–11 June 2022, Nice, France Publisher: Copernicus GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Nourian, P.; Luscuere, P.; Wagenaar, C. Ifc2bcm: A Tool for Generating Indoorgml and Building Configuration Model from Ifc. [CrossRef]

- Kassim, S.A.; Gartner, J.B.; Labbé, L.; Landa, P.; Paquet, C.; Bergeron, F.; Lemaire, C.; Côté, A. Benefits and limitations of business process model notation in modelling patient healthcare trajectory: a scoping review protocol. 12, e060357. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Zheng, H. Generation Scheme of IndoorGML Model Based on Building Information Model. In Proceedings of the Phygital Intelligence; Yan, C.; Chai, H.; Sun, T.; Yuan, P.F., Eds. Springer Nature, pp. 225–234. [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, H. ARE YOUR INDOORGML FILES VALID? VI-4-W1-2020, 109–118. Conference Name: ISPRS TC IV3rd BIM/GIS Integration Workshop and 15th 3D GeoInfo Conference 2020 (Volume VI-4/W1-2020) - 7–11 September 2020, London, UK Publisher: Copernicus GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nor, R.; Jalaldeen, M.; Razi, M.; Zakaria, A.; Safiuddin, A.; Fakhri, A.; Zulaiha, P.; Saat, A. Cloudemy: Step into the Cloud.

- Ledoux, H. indoorjson/software/ig2ij at master · tudelft3d/indoorjson · GitHub.

- many others, T.V.M.a. COMPAS: A framework for computational research in architecture and structures. [CrossRef]

- Aric, A. Hagberg, Daniel A. Schult.; Pieter J. Swart. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference (SciPy2008). pp. 11–15.

- March, S.T.; Smith, G.F. Design and natural science research on information technology. 15, 251–266. [CrossRef]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. 24, 45–77. [CrossRef]

| Information Type | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Information |

Room boundary consisting of a series of 3D points |

{’central_waiting’: [’-20,34,4’,’-20,29,4’,’, ’-19,29,4’,’-19,39,4’,’-20,34,4’]} |

| Topological Information |

A Network Graph consisting of nodes and edges |

{’Graph1’: [{"node1": {"id": "R1"}, "node2": {"id": "R3"}, "edge1":{"id": "e1"}}]} |

| Semantic Information |

Room Name | {’Department$Imaging’: [’Central_waiting’]} |

| Operational Information |

A patient journey through the hospital ( a series of rooms that the patient need to attend) |

{’patient_journey_1’: [’Entrance/Exit’,’Registration’, ’consulting’,’Entrance/Exit’]} |

| Departments & Rooms |

|---|

| {Department$A’: [’CENTRALWAITING1AC1’,’CORRIDOR2AC3’,’PHARM.DISP.1A16’, ’CORRIDOR2AC1’,’DENTALWAITING2A11’, ... ’X-RAYALCOVE2A12-A’]} |

| {’Department$B’: [’CORRIDOR1BC2’,’LAB1B04’,’CORRIDOR1BC4’, ... ’RECEPTION1B01’,’RECEPTION1B13’,’TECHOFFICE2B9’]} |

| {’Department$D’: [’WAITING/ACTIVITYAREA1DC1’,’MAINMECHANICALROOM2D05’, ... ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D11’,’INTERACTIONSTATION1D07’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D08’,’INTERACTIONSTATION1D09’, INTERACTIONSTATION1D28’,’INTERACTIONSTATION1D34’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D35’, ... ’COMPUTERROOM2D04A’]} |

| ... |

| Input data list | Output data list |

|---|---|

| origianl_medical_path_1 = [’registration’,’triage’,’waiting’, ’diagnosis’,’medicine’] |

medical_path_1 = [’RECEPTION1B13’, ’WTSandMEAS.ROOM1D15’, ’WTSandMEAS.ROOM1D30’, ’WAITING/ACTIVITYAREA1DC1’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D11’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D07’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D32’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D02’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D13’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D36’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D10’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D08’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D09’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D28’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D34’, ’INTERACTIONSTATION1D35’, ’PHARM.DISP.1A16’] |

| Room Attributes | |

|---|---|

| Before | {’CENTRALWAITING’: {’area’: ’127’}, ’WAITING/ACTIVITYARE’: {’area’: ’178’}, ...} |

| After | {’CENTRALWAITING’: {’area’: ’127’, ’people density’: ’0.9’}, ’WAITING/ACTIVITYARE’: {’area’: ’178’, ’people density’: ’1.0’}, ...} |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).