1. Introduction

The acceleration of global ageing and urbanisation is leading to an increase in demand for medical care, which in turn is giving rise to significant challenges in the planning and management of medical facilities. A medical facility is not merely a location for the provision of fundamental healthcare services; it also serves a multitude of roles, including the optimisation of medical resource allocation, the enhancement of service quality, and the reduction of operational costs. For example, efficient medical resource allocation can reduce patient waiting times, while a well-designed spatial layout can improve patient comfort and streamline medical processes. Consequently, the optimisation of the structural and functional aspects of medical facilities, particularly during the design phase, has emerged as a prominent area of investigation within the domains of architectural design and urban planning on a global scale [

1]. With land and financial resources often limited, the question of how to maximise the efficiency of medical services while ensuring accessibility and sustainability has become a pressing issue. In this context, striking a balance between functionality, cost, and environmental impact is a complex and multi-faceted challenge for urban planners and healthcare administrators.

The question of how to optimise the efficiency of medical services in the context of limited land resources and capital investment has become a significant area of focus within the field of medical building planning. For instance, in highly urbanised regions, the availability of land for new healthcare infrastructure is constrained, compelling planners to make efficient use of existing facilities by reconfiguring their layouts or integrating advanced technologies for better service delivery.

Conventional methodologies for optimising healthcare facilities tend to rely on expert judgement and rule-driven design processes. While these approaches benefit from domain expertise, they are limited in scalability and often fail to address the nonlinear relationships between intricate design variables and requirements. For instance, the spatial layout of facilities directly affects patient flow, while also interacting with energy consumption and resource allocation. In the design of multi-level and multi-objective medical buildings, the challenge of balancing factors such as patient flow, the distribution of medical resources, spatial layout, and building energy efficiency has become a complex decision-making problem [

2]. Furthermore, as healthcare facilities become increasingly complex and diverse, traditional optimization methods are often constrained by an inability to capture intricate relationships, a lack of flexibility, and the difficulty of processing vast amounts of data.

Nevertheless, it is challenging to elucidate the coupled influence of multiple design variables on the research objectives when employing the most prevalent design variable analysis techniques, such as univariate analysis and sensitivity analysis. In the design of medical buildings, the multifaceted functional requirements and rigorous safety and hygiene standards render the analysis of a single factor frequently inadequate for capturing the intricate interplay between diverse design factors. Furthermore, the inherent uncertainty in healthcare building design samples frequently gives rise to multiple scenarios that collectively satisfy the comprehensive evaluation criteria. The analysis of a large number of design solutions requires the urgent integration of efficient artificial intelligence technology to comprehensively evaluate multiple performance indicators in the early design stage, thereby facilitating a more efficient and accurate decision-making process [

3]. In light of the multiplicity of objectives and constraints, researchers are tasked with evaluating each design option in order to identify the optimal solution that aligns with the needs of diverse stakeholders, while simultaneously considering the performance evaluation objectives and constraints.

The rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, particularly within the medical sector, has prompted an increasing number of studies to investigate its potential applications in energy conservation and emission reduction, functional layout optimisation, and resource allocation. Artificial intelligence technology, in particular the multi-objective optimisation method, has emerged as an effective tool for addressing the diverse performance optimisation needs of medical buildings [

4]. This approach allows for a rapid and precise exploration of appropriate design options, given that healthcare building design is inherently a multi-objective optimisation problem involving multiple conflicting performance goals, such as minimum building energy consumption, lowest carbon emissions, maximum space utilisation, and good patient comfort. Consequently, in the design of medical buildings, multi-objective optimisation combined with artificial intelligence technology has become a key means to improve building performance, reduce operating costs and improve user experience [

5].

In recent years, with the rapid development of deep learning technology, especially graph convolutional networks (GCN), researchers have begun to explore the potential of this advanced technology in optimising medical buildings. GCN is capable of effectively modelling complex spatial and functional relationships, learning dependencies and influence patterns between different facilities, and providing more accurate optimisation solutions for building design [

4]. The various parts of a medical facility, including examination rooms, waiting areas, and operating rooms, are not only spatially connected but also functionally interdependent. For instance, the efficient design of examination rooms must consider proximity to diagnostics areas to reduce delays while aligning with infection control protocols. These multi-dimensional relationships can be modelled through the graph convolutional network, thereby improving the intelligence and accuracy of architectural design. Such an approach can revolutionise the way facilities are planned and adapted to future needs, ensuring resilience and operational excellence.

The design of a healthcare building is fundamentally different from that of a commercial or residential building in general. First and foremost, healthcare buildings need to consider patient flow design, i.e., the efficiency of the flow between patients, healthcare workers, and medical equipment. Second, healthcare buildings need to deal with the need for rapid response to emergency aisles and complex equipment configurations. In this complex building environment, the GCN model can optimize the spatial layout and reduce energy consumption by analyzing the structural characteristics and functional requirements of the building. In addition, the energy demand of medical buildings is often greatly affected by the operation of equipment, air conditioning systems, and lighting systems, and the optimization of the GCN model not only takes into account the layout of these functional areas, but also reduces the energy consumption of the overall building by optimizing the configuration of equipment rooms.

2. Related Work

In a study conducted by Abdullah et al. [

6] the Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) algorithm was employed to enhance the architectural lighting system. This resulted in the simultaneous achievement of two key objectives: a 27% reduction in energy consumption and an improvement in visual comfort by 7%. The optimisation of the lighting system design resulted in the effective reduction of energy consumption and the improvement of user comfort, while meeting the requisite functional requirements. The findings of this study demonstrate that the utilisation of the MOPSO algorithm in the enhancement of building energy efficiency and the optimisation of comfort has considerable potential, particularly in the context of energy-saving building design.

Yong et al. [

7] employed an enhanced BBMOPSO-A algorithm to optimise the passive and active design of a range of building types in China. The BBMOPSO-A algorithm effectively balances global and local search capabilities, thereby achieving the diversity and comprehensiveness of an optimal design scheme. This results in a 11.82% reduction in thermal discomfort time and an increase in energy consumption of only 1.74%. This study illustrates the benefits of the BBMOPSO-A algorithm in multi-objective optimisation, particularly in the design of buildings that take into account multiple factors, such as comfort and energy efficiency. This approach can effectively enhance the performance and living comfort of buildings while controlling the growth of energy consumption.

In their study, Gerardo et al. [

8] employed a combination of Matlab and EnergyPlus to optimise a number of design variables, including the air conditioning setpoint temperature, the radiative properties of plastering, the thermophysical properties of the envelope, the window type, and the building orientation. They used the NSGA-II optimisation algorithm to achieve this. The optimisation method was successful in achieving the triple minimisation of primary energy consumption, economic cost and thermal discomfort time of the building, thereby demonstrating the great potential of the optimisation framework in improving the energy efficiency and comfort of the building. The study demonstrates that the integration of advanced building energy efficiency simulation tools and optimisation algorithms can facilitate the identification of an optimal balance between multiple objectives, thereby achieving optimal performance in building design.

In a similar vein, Rosso et al. [

9] put forth a two-stage, multi-objective optimization approach for new and renovated buildings, which considers both active and passive building design strategies. Initially, the aNSGA-II optimisation algorithm was employed to ascertain the optimal building geometry design parameters. Subsequently, the building envelope and photovoltaic system design were further optimised, resulting in a notable reduction in energy costs and energy demand. The implementation of this optimisation approach has resulted in a 60% reduction in the building's energy requirements and a 23% reduction in annual energy costs. This study presents a systematic multi-objective optimisation approach to architectural design, which can effectively address the needs of energy conservation and sustainable development in modern buildings.

Yuan et al. [

10] concentrated their efforts on optimising the transparent envelope, with a particular focus on the design of window sill heights and window-to-wall ratios in conjunction with different wall orientations. As a result of these modifications, the amount of sunlight reaching the interior of the building was increased by 17%, while the energy load was reduced by the same amount. Furthermore, the percentage of occupants experiencing discomfort was decreased by 9%. These findings highlight the significant impact of the envelope on both building energy efficiency and occupant comfort, and demonstrate the potential for enhancing building performance through envelope design optimisation.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Graph Representation and Modeling

The representation of a medical facility is defined as

, where

represents a set of nodes, denoting each medical facility unit, and

represents a set of edges, indicating the spatial or functional connection between facilities. Each node

is associated with an eigenvector

, which provides information regarding the attributes of the facility in question, including its area, function, and demand. A weighted adjacency matrix

is constructed in order to represent the relationship between facilities. In particular, the weighting of an edge,

can be defined in accordance with the following Equation (1).

where

and

represent the eigenvectors of nodes

and

, which correspond to the properties of the facility. The Euclidean distance

between

and

reflects the spatial distance between the nodes. Functions

and

pertain to the characteristics of facilities

and

, such as the presence or absence of shared medical resources.

indicates functional similarity.

The adjustment factor

controls the weight of spatial distance to functional differences, while

represents the adjustment factor of functional similarity. The formula enables the capture of spatial relationships between facilities, as well as the integration of functional dependencies, thus providing a more accurate reflection of the complex interactions between facilities. In a graph convolutional network (GCN), the characteristics of each node are obtained through the aggregation of the features of neighbouring nodes. The standard graph convolution operation, which is used in the context of a GCN, is as Equation (2):

where

represents the node feature matrix of layer

. The normalized adjacency matrix,

, is calculated as

, where

is the degree matrix and

is the identity matrix. This is done to prevent the degree difference of the nodes from biasing the result. The weight matrix of layer

,

, and the activation function,

, are also defined. The activation function is typically either ReLU or LeakyReLU.

3.2. Deep Multilayer Graph Convolution

In order to enhance the adaptability of the model, we introduce an adaptive graph convolution mechanism, which allows the model to dynamically adjust the adjacency matrix

in accordance with the adaptive weight

of the various adjacency matrices. The medical scenario of the student is generated by a trainable graph structure generator

. In particular, the instrument is calculated in accordance with the Equation (3):

where the node feature matrix of the

layer,

, contains both spatial and functional information between facilities.

represents the original input feature matrix, which encapsulates the intrinsic characteristics of the facility. is a small neural network that generates the adjacency matrix of each layer dynamically, through the learning of node features and graph structure information, with the objective of adjusting the relationship between facilities.

The model is equipped with an adaptive mechanism that enables the flexible adjustment of the relationship between facilities in accordance with the specific environmental and operational requirements of the scenario in question, thereby facilitating a more tailored response to diverse medical contexts. In order to further enhance the expressive ability of the model, we employed a stacked approach, utilising multiple graph convolutional layers for deep learning. In a multi-layer graph convolutional network (GCN), each layer aggregates node features using adjacency matrices and weight matrices, subsequently mapping them through nonlinear activation functions. The graph convolution operation of layer

is as Equation (4):

where

represents the normalised adjacency matrix of layer

, which enables the network to progressively assimilate a progressively extensive range of information pertaining to neighbouring entities. The model is capable of learning increasingly complex spatial and functional relationships between facilities by stacking multi-layer GCNs. This enables the model to gradually capture more extensive neighbour information, from local to global, in a step-by-step manner. The propagation and aggregation of information in a layer-by-layer manner enables the representation of each node to integrate the features of a greater number of neighbours, thereby improving the optimisation effect.

In the final stage, we integrate multiple objective functions to optimise the allocation of medical resources through end-to-end training. In order to achieve this, a composite loss function

is defined. The energy efficiency loss

is a measure of the efficiency of a healthcare facility in terms of energy consumption. The objective is to minimise total energy consumption, as illustrated by Equation (5).

The symbol

represents the energy consumption characteristics of facility V. The energy efficiency of the entire medical facility system is calculated by summing the energy efficiency of all facilities. The

dependence and coordination between facilities must be measured and optimised, with the objective of achieving the greatest possible matching degree for each functional area. This is expressed as Equation (6):

where

represents the set of neighbouring nodes of node

.

and

are the functional eigenvectors of facilities

and

, and

is the edge weight between facilities.

3.3. Network Pruning for Model Simplification

To enhance the efficiency and scalability of the proposed Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) model, a network pruning methodology is introduced. This process systematically removes redundant parameters and connections within the GCN, thereby reducing computational complexity without compromising performance.

Initially, the importance of each node and edge in the network is quantified based on metrics such as contribution to resource allocation optimization and influence on energy efficiency. Edges with lower importance scores are pruned iteratively, guided by a sparsity constraint to ensure the network remains functional.

The pruning process is further refined using a regularization technique to maintain balance between sparsity and model accuracy. Specifically, an L1 regularization term is incorporated into the loss function to penalize unnecessary connections. The resulting sparse GCN architecture demonstrates a significant reduction in model size, leading to faster training times and lower computational resource requirements, making it more applicable for real-world healthcare scenarios.

Finally, the pruned network is fine-tuned through retraining on the original dataset, ensuring that the remaining parameters are optimally adjusted. Experimental results reveal that this approach not only preserves the predictive accuracy of the model but also facilitates its deployment in resource-constrained environments, such as rural or underdeveloped healthcare facilities.

Table 1 demonstrates the impact of network pruning on key performance indicators. While there is a slight reduction in validation accuracy and energy efficiency improvement, the overall computational efficiency gains make the pruned model a viable solution for deployment in real-world scenarios.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setups

The ASHRAE Great Energy Predictor III Challenge dataset will be used for the structural and functional optimisation of healthcare buildings. The dataset's architectural features enable the construction of a graph representation where each functional area or space is represented as a node, and the spatial and functional relationships between these areas are modelled as edges. Spatial relationships are determined by proximity and connectivity, while functional relationships capture interdependencies such as shared resources or workflows. A graph convolutional network (GCN) will be employed to learn and model these relationships, optimising resource allocation and enhancing the efficiency of medical services. This approach enables the dynamic adjustment of the layout and functions of healthcare facilities, ensuring better resource utilisation and improved service coverage.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

In this experiment, four multi-objective optimisation algorithms were selected for analysis: MOPSO, BBMOPSO-A, NSGA-II, and aNSGA-II. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of these algorithms in optimising the structure and function of a healthcare building, with the goal of improving energy efficiency and comfort while reducing energy consumption. The proposed GCN-based model ("Ours") was also included in the analysis to benchmark its performance against these traditional approaches.

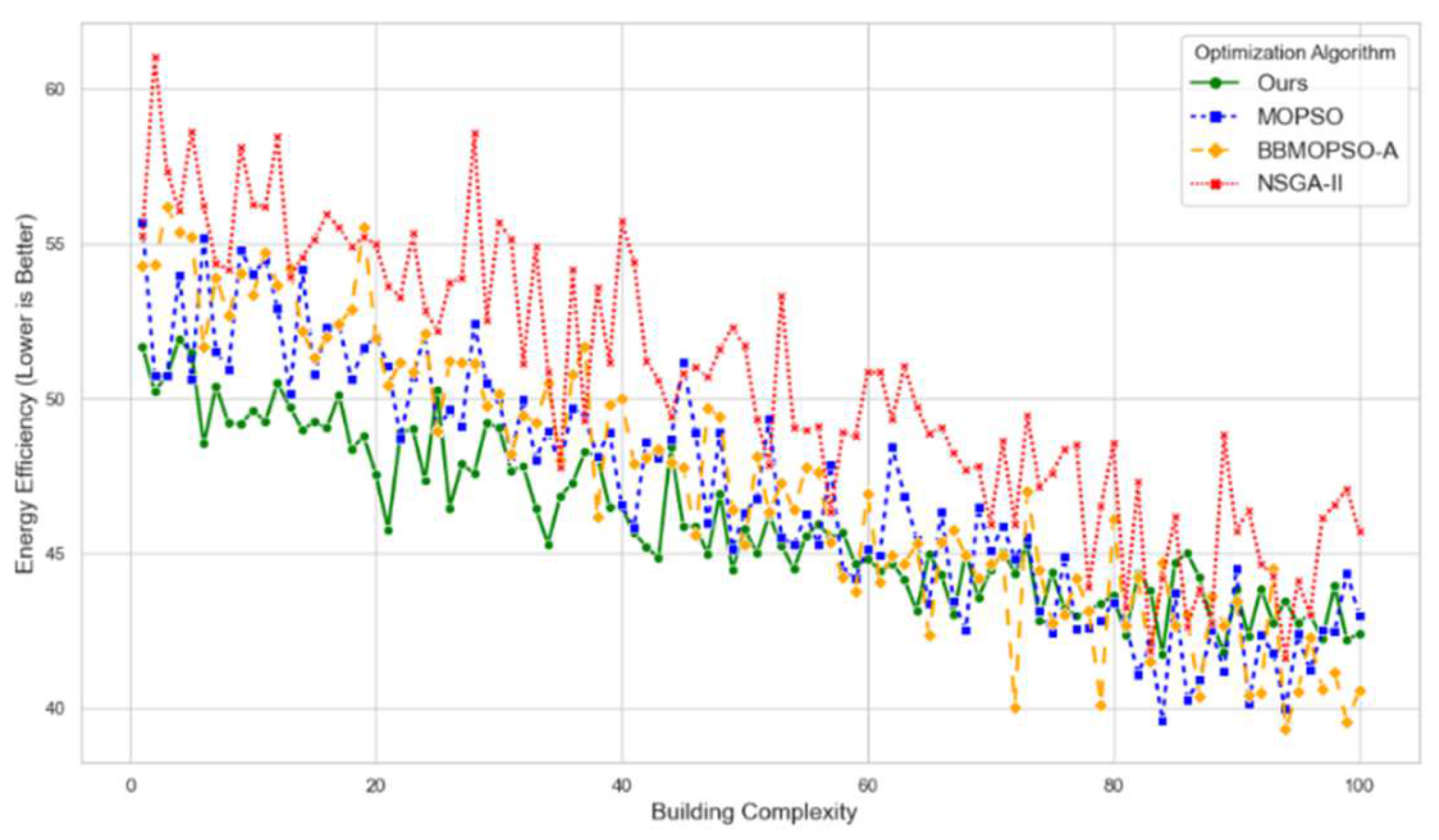

The evaluation metric employed was energy efficiency, with

Figure 1 illustrating the impact of disparate optimisation algorithms on energy consumption throughout the building design process. In this context, lower energy efficiency levels are indicative of greater efficiency. A comparison of the energy efficiency changes of different optimisation methods reveals that the "Ours" method consistently outperforms the other methods across the entire parameter range, exhibiting the lowest energy efficiency value.

This result highlights the superior capability of the GCN-based model in capturing spatial and functional relationships within the building, which is achieved through the introduction of an adaptive graph convolution mechanism. This mechanism dynamically adjusts the relationships between facilities, enabling more precise resource allocation optimisation. Additionally, the ability of the GCN model to aggregate multi-level features across different functional nodes allows for a deeper understanding of spatial and functional dependencies, contributing to enhanced energy efficiency.

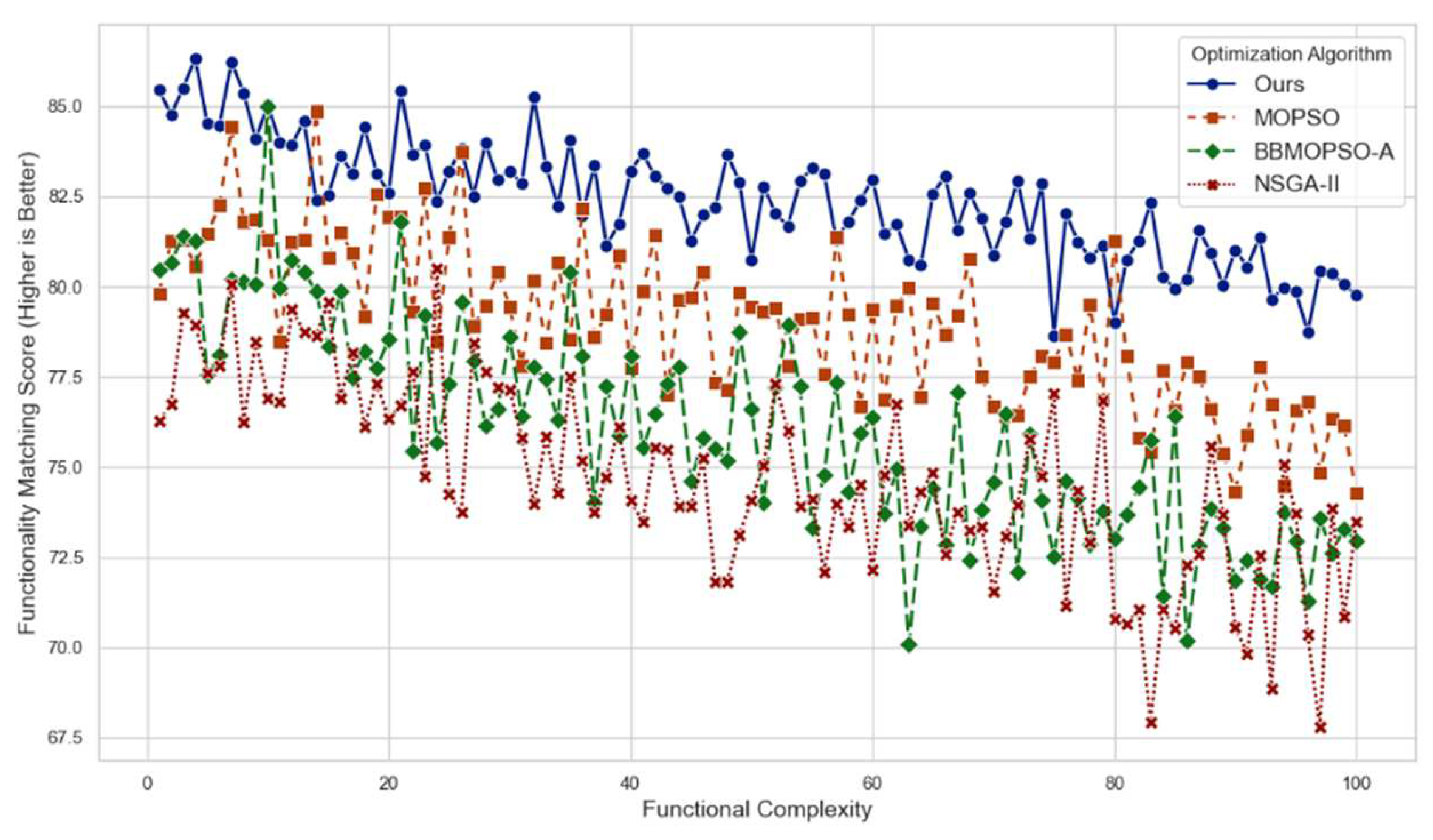

The evaluation index of building function matching degree is employed to assess the efficacy of the optimised design scheme in fulfilling the functional requirements of the building, spatial layout and resource allocation.

Figure 2 illustrates that the method based on a graph convolutional network (Ours) demonstrates superior performance in terms of the matching degree of building functions when compared to other optimisation algorithms.

This is primarily due to the fact that GCN is better equipped to model the spatial and functional relationships between building facilities, thereby enhancing the overall matching degree through the dynamic adjustment of the diagram's structure and weights. This allows for a more comprehensive consideration of the interdependence between different functional areas. Nevertheless, conventional optimisation algorithms, such as MOPSO and NSGA-II, are less effective than GCN methods in addressing intricate functional relationships and non-linear constraints, despite their capacity to optimise building design to a limited extent. The introduction of the graph convolution mechanism enables the Ours method to more effectively capture the complex dependencies and demand changes inherent to architectural design, particularly in the context of large-scale medical facilities, thereby demonstrating enhanced adaptability and optimisation efficacy.

Table 2 presents the experimental results of the four optimisation algorithms and offers a comparison of their corresponding model parameters. The table includes scores for the percentage reduction in energy consumption, the percentage increase in thermal comfort, functional fit, and design flexibility. The "Ours" method demonstrates superior performance in comparison to other algorithms across a range of indicators. In particular, with regard to the reduction of energy consumption and the degree of functional matching, the "Ours" method achieves a 27% reduction in energy consumption and a 92% degree of functional matching, respectively, which is significantly higher than that of the other algorithms.

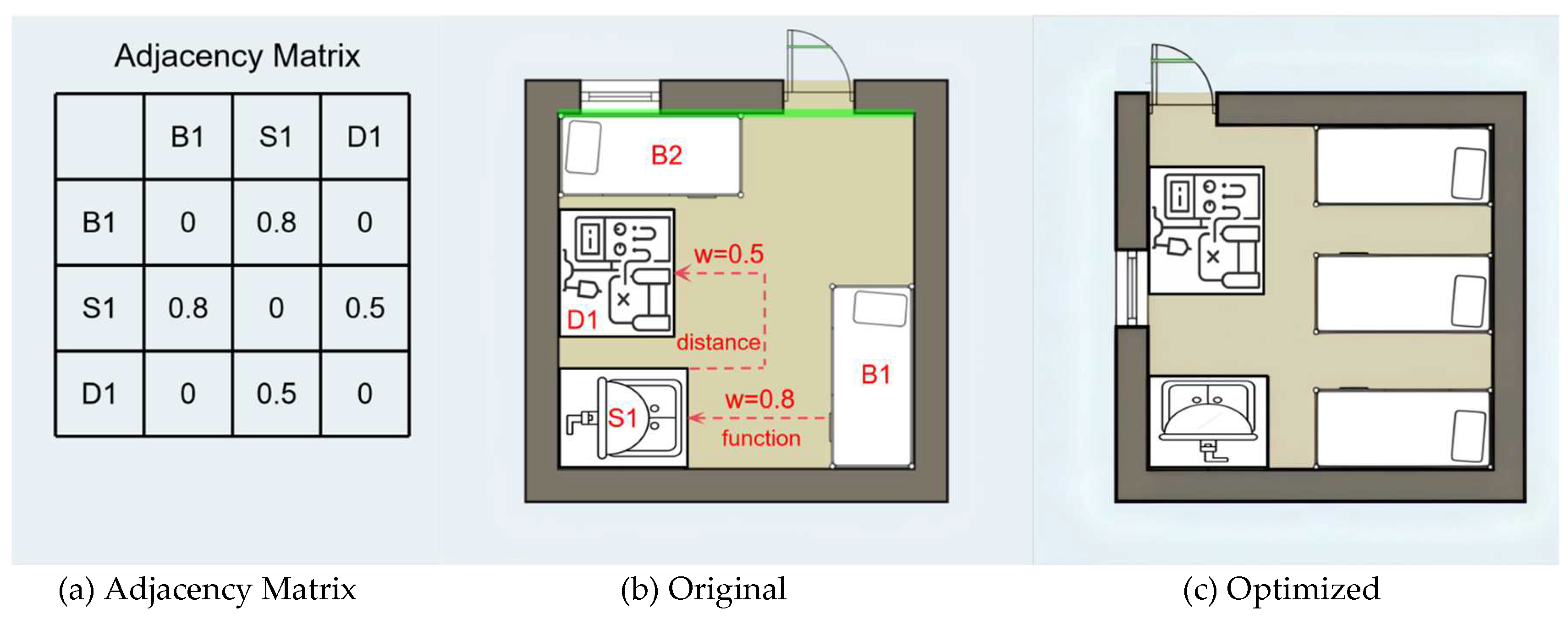

Building layout and circulation optimization extends beyond core layout adjustments. As demonstrated in

Figure 3, the GCN-based model optimizes natural ventilation and daylighting distribution (e.g., adapting window configuration to local geography), thereby reducing dependence on artificial lighting and HVAC systems. The modeled ward layout explicitly encodes functional and spatial relationships through (1) vertices (nodes) representing beds (B1-B2), sinks (S1), and medical devices (D1); (2) edges capturing spatial proximity (e.g., S1-D1, 3m) and functional dependencies (e.g., B1-S1 for handwashing needs); and (3) an adjacency matrix quantifying connection weights. These elements collectively enable the model to reconfigure the ward (e.g., adding beds while ensuring compliance with hygiene protocols via sink adjacency) and maximize space utilization without compromising energy efficiency.

Structural and functional optimization is an important means to improve the energy efficiency of buildings. In medical buildings, reasonable space layout and equipment configuration can directly affect the energy consumption of the building. For example, optimizing the layout of patient rooms and treatment areas can reduce the load on the air conditioning system while increasing the utilization of natural ventilation and daylighting. In terms of functional layout, the reasonable configuration of emergency passages and equipment areas can ensure the operation of equipment while reducing the use of air conditioning and lighting. By combining the GCN model, architects can precisely adjust the energy efficiency requirements of each area according to the functional requirements of different areas, so as to improve the overall energy efficiency of the building.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the experimental results demonstrate that the optimisation model based on a graph convolutional network ("Ours") exhibits superior performance to traditional optimisation algorithms (such as MOPSO, BBMOPSO-A, and NSGA-II) across multiple indicators, including energy efficiency and functional matching. In particular, the "Ours" model demonstrated superior performance in terms of energy consumption reduction (27%) and functional matching (92%), which evinces its capacity to capture the intricate relationship between spatial configuration and functional requirements in healthcare facilities. Furthermore, the model's design flexibility score (9.5) indicates its capacity to adapt to diverse design scenarios. In comparison, alternative algorithms are found to be less effective in terms of energy efficiency and functional matching, which may be attributed to the constraints associated with their local search capability.

Additionally, the introduction of network pruning further enhanced the practicality of the model by significantly reducing its computational complexity without compromising performance. This approach ensures the model's scalability and applicability in resource-constrained environments, such as rural or underdeveloped healthcare facilities. The pruned model achieved a 52% reduction in parameter size and a 46% decrease in training time per epoch, demonstrating the feasibility of deploying advanced optimisation models in real-world scenarios where computational resources are limited.

The findings of this study underscore the potential of combining graph convolutional networks with adaptive and pruning mechanisms to address the multifaceted challenges in healthcare facility design. By capturing the intricate dependencies between spatial and functional elements, the proposed model effectively optimises resource allocation and enhances energy efficiency. These capabilities make it a promising tool for the future development of intelligent healthcare infrastructure.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. While the model excels in addressing spatial and functional optimisation, future work should explore its integration with real-time data inputs, such as patient flow dynamics and emergency response requirements, to further enhance its adaptability. Additionally, extending the framework to accommodate multi-hospital networks could unlock new possibilities for regional healthcare resource optimisation.

References

- Mansour, R.F.; El Amraoui, A.; Nouaouri, I.; Diaz, V.G.; Gupta, D.; Kumar, S. Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Enabled Disease Diagnosis Model for Smart Healthcare Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 45137–45146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.N.; Ren, G.; Young, K.; Pina, S.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Scaffold Fabrication Technologies and Structure/Function Properties in Bone Tissue Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Wang, Q. Structural Optimization in Civil Engineering: A Literature Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Sun, H.; Mehrabi, P.; Ali, Y.A.; Al-Razgan, M. Application of artificial intelligence technique in optimization and prediction of the stability of the walls against wind loads in building design. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 31, 4755–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, C. Multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service value for optimization of land use in the Sichuan-Yunnan ecological barrier, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagiman, K.R.; Abdullah, M.N.; Hassan, M.Y.; Radzi, N.H.M. A new metric for optimal visual comfort and energy efficiency of building lighting system considering daylight using multi-objective particle swarm optimization. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.; Li-Juan, Y.; Qian, Z.; Xiao-Yan, S. Multi-objective optimization of building energy performance using a particle swarm optimizer with less control parameters. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Fabrizio; et al. Building envelope design: Multi-objective optimization to minimize energy consumption, global cost and thermal discomfort. Application to different Italian climatic zones. Energy 2019, 174, 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ciardiello, A.; Rosso, F.; Dell'Olmo, J.; Ciancio, V.; Ferrero, M.; Salata, F. Multi-objective approach to the optimization of shape and envelope in building energy design. Appl. Energy 2020, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Jiang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L. Multi-objective optimization of transparent building envelope of rural residences in cold climate zone, China. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).