1. Introduction

In recent years, the acceleration of urbanization has led to a marked increase in urban spatial systems' sensitivity to external pressures, significantly enhancing their vulnerability [

1]. In this context, the development of robust and resilient urban systems has emerged as a critical focus in the research and practice of urban planning [

2]. Among these systems, the network of medical facilities plays a vital role in maintaining urban safety and health, highlighting its increasing importance. Directly tied to the fundamental health needs of the population, the healthcare facility system is essential for the continuity and stability of urban activities. In the face of sudden public health emergencies [

3], a well-developed medical facility system can respond quickly and effectively reduce the threat of disasters to residents' lives and health, thereby ensuring the seamless operation of various urban functions. However, conventional planning and layout approaches for medical facilities tend to be inflexible, rendering them ill-equipped to cope with complex [

4], dynamic, and unpredictable pressure scenarios. This rigidity significantly constrains the overall enhancement of urban resilience.

In the phase of high-quality development, primary healthcare facilities should move beyond their inherent functional constraints, and integrate more closely with efforts to enhance urban resilience [

5]. By fostering collaborative interactions between primary healthcare and other urban systems, cities can more effectively respond to various shocks, maintain normal operations, and facilitate continual renewal and evolution [

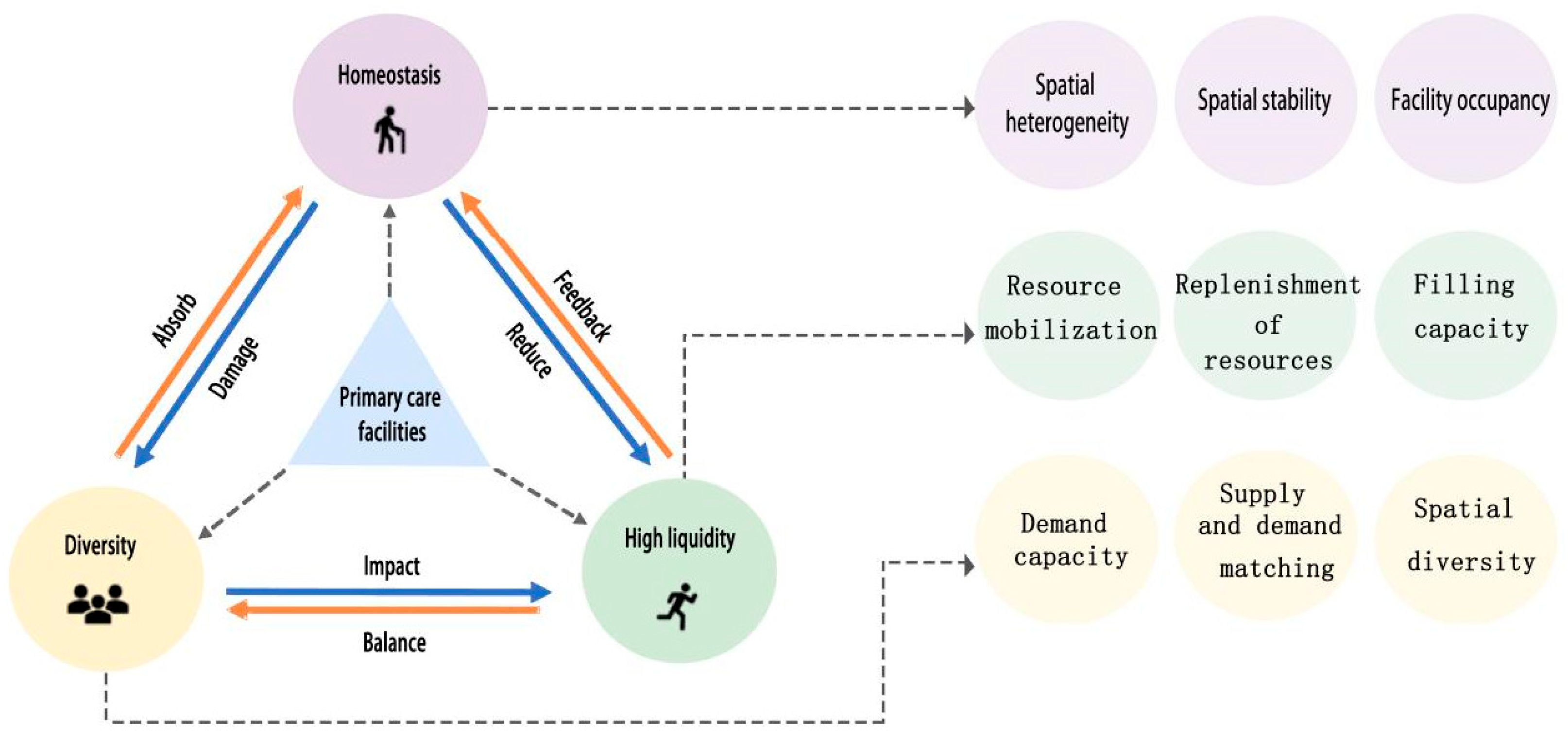

6]. Specifically, we should employ medical buildings to improve social living conditions while protecting lives and health, thereby creating a comprehensive system that incorporates healthcare, environmental, and social dimensions. See

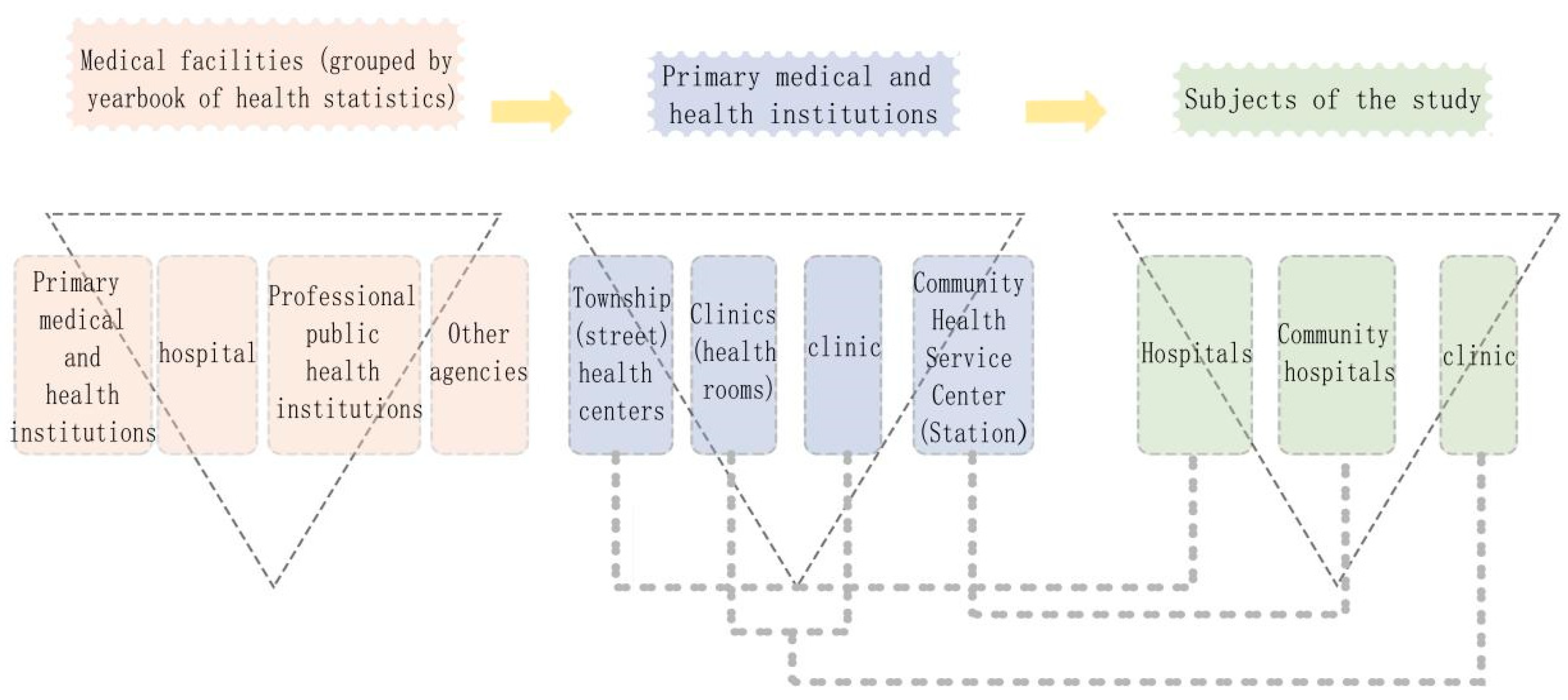

Figure 1.

In this study, the medical resources in the main urban area of Harbin are grouped according to the Health Statistics Yearbook. National healthcare institutions are divided into four categories: hospitals, primary medical institutions [

7], specialized public health institutions, and other facilities. This research focuses specifically on primary healthcare institutions, within the central area of Harbin's urban district. For this analysis, outpatient departments and clinics (medical offices) [

8] within primary healthcare are merged into a single category referred to as "clinics." Consequently, the subjects of this study encompass three types: community health centers[

9], community hospitals, and clinics. These categories are further delineated into hierarchical levels based on the classification of healthcare resources and service scope: community health centers, community hospitals, and clinics[

10].

In prior studies,a number of papers published in 2023 utilized statistical analysis to investigate the impact of accessibility on walking trip probability and duration[

11]. M. Das and B. Dutta assessed slum populations, existing healthcare facilities (HCF), and slum communities characterized by low geographical accessibility. They developed an analytical model for regions located outside the coverage of existing healthcare institutions (HCF)[

12]. The paper uses cities as case studies, such as Beijing, as an example for research, proposed a novel framework constructed from multisource data to analyze regional accessibility within urban healthcare systems, placing particular emphasis on prevalent diseases among the elderly. They gathered online registration data to evaluate the capacity of healthcare service supply, while considering the impact of the service scope offered by these facilities[

13]. In 2024, related papers used a two-step floating catchment area method to measure pedestrian accessibility to urban parks, revealing significant geographic disparities[

14].

From a holistic perspective, existing research rarely examines healthcare access from the multiple dimensions of residents' needs. There has been little extension from the intrinsic characteristics of resilience to detailed analyses, and the optimization of healthcare layouts frequently lacks practical implementation. Firstly, concerning the choice of research methods and perspectives, most studies tend to focus on the diverse and multidimensional demands of residents seeking medical treatment[

15]. However, there is a notable scarcity of studies that incorporate resilience theory into the analysis of residents' healthcare systems. Consequently, it is necessary to conduct more in-depth research on the actual operation of medical institutions at different regions and levels. By leveraging modern technological approaches such as big data analysis, it is crucial to propose actionable and targeted optimization strategies. Furthermore, there should be an emphasis on specific studies addressing the practical implementation of layout optimization, with the objective of constructing a more efficient, equitable, and resilient healthcare environment for residents[

16].

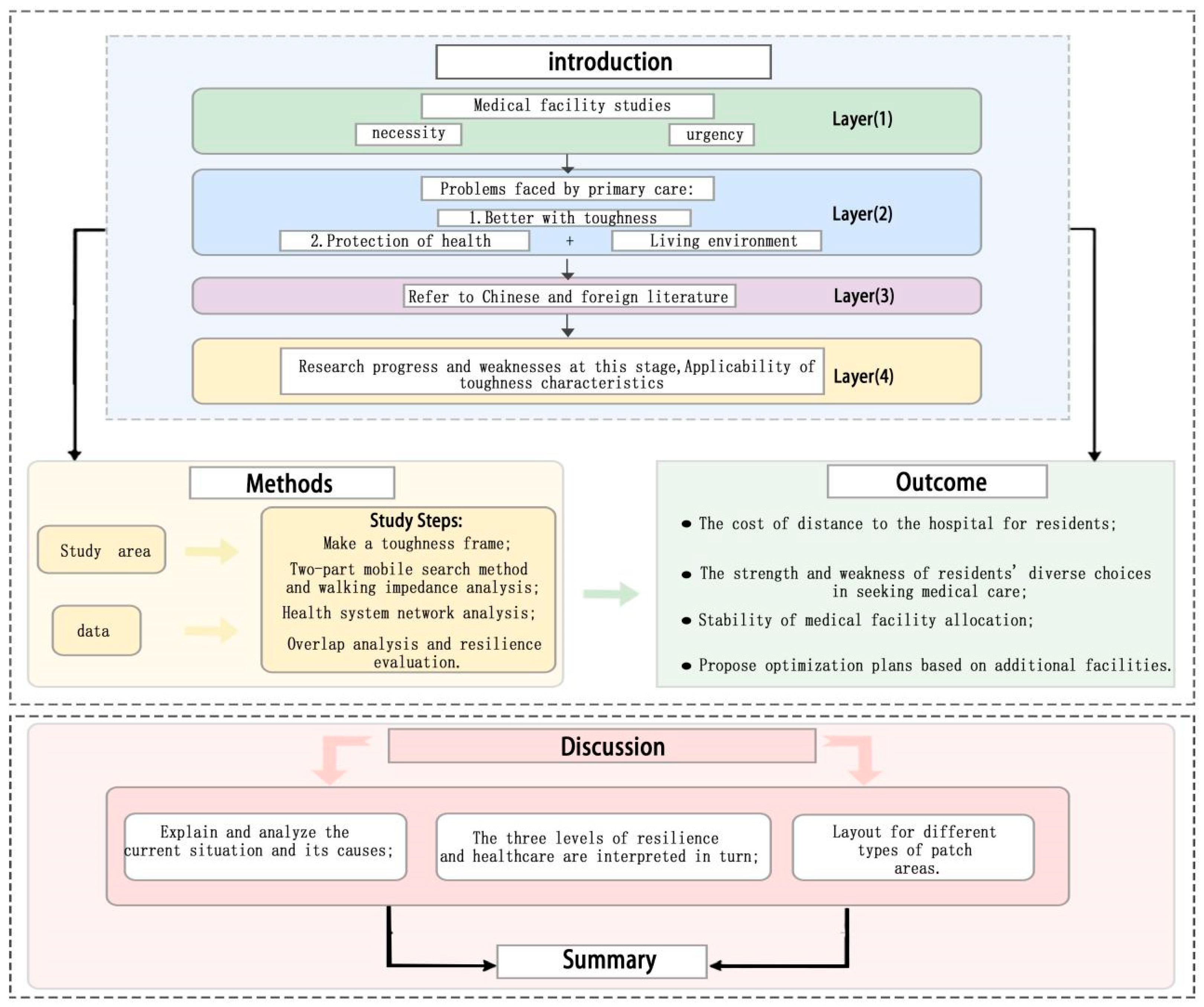

Using the Gaussian two-step attenuation method to deeply analyze residents' walking impedance, the average value and standard deviation of medical transmission in various areas of the main urban district of Harbin were calculated[

17]. This data effectively quantifies the distance costs that residents in different areas must incur to access medical services[

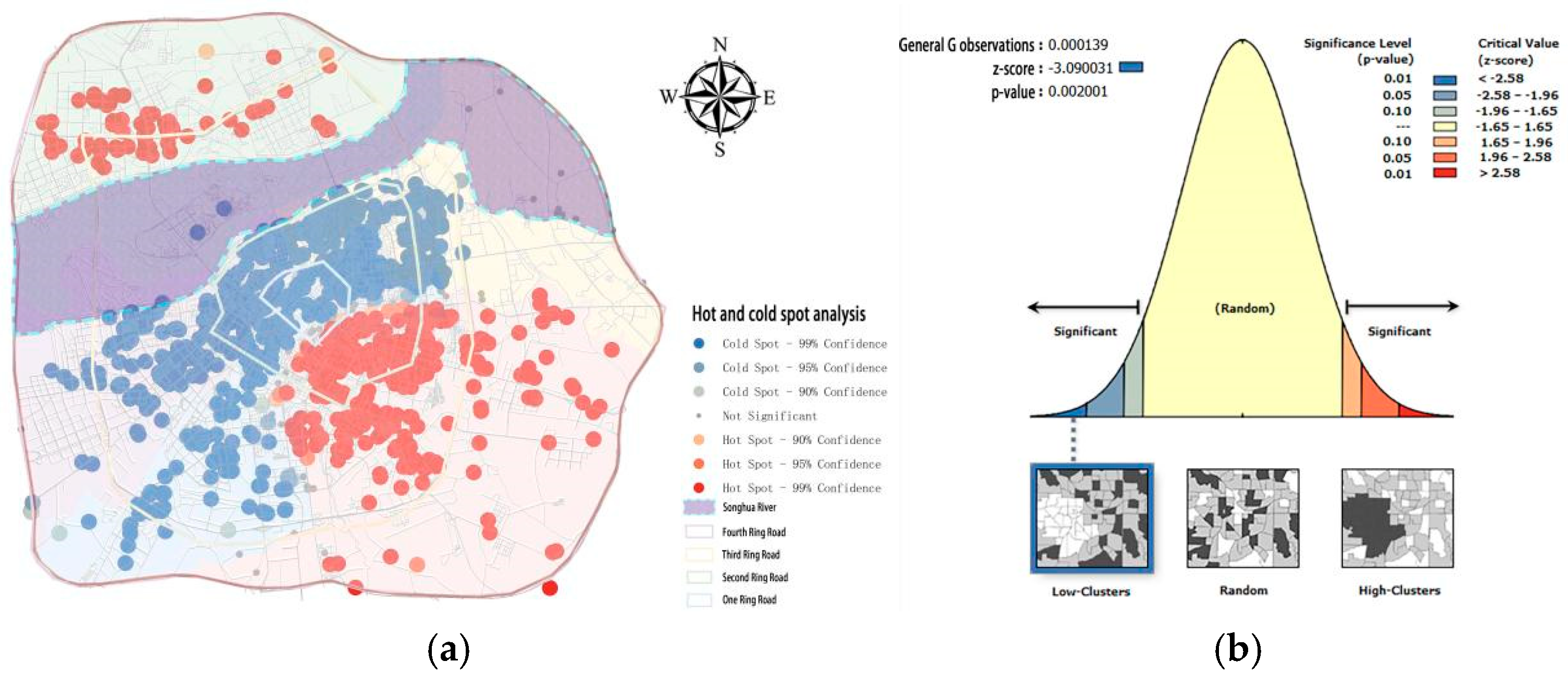

18]. Through the analysis of cold and hot spot clustering, the disparities in the richness of medical resources and their distribution capabilities among various regions were visually assessed, providing essential evidence for understanding how healthcare resources are allocated across different areas. While assessing citizens' healthcare options, the full service radius study also examines healthcare service coverage. To more accurately identify unstable areas within the healthcare distribution, an overlapping analysis of service radii was conducted[

19], supplemented by LISA, which identified regions that necessitate additional medical facilities. Finally, building on the aforementioned analyses, optimization strategies for the layout of medical facilities were proposed[

20], alongside a thorough discussion of specific implementation approaches for these strategies. The entire research process and framework are illustrated in

Figure 2, which has been refined based on the resilience characteristics framework. This framework adopts an analytical perspective on the distribution of healthcare resources from the standpoint of residents seeking medical care, allowing for a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the medical resource distribution in Harbin's main urban area. Furthermore, this analytical approach also considers social life and has attempted spatial resilience-based layout optimization, thus providing valuable references and insights for future urban planning and healthcare resource allocation[

21].

4. Conclusions and Optimization Plan

4.1. Conclusions

This article analyzes the distribution of grassroots medical facilities in the main urban area of Harbin from three dimensions: the transmissibility of residents' distances to medical treatment, the diversity of treatment options, and the stability of the healthcare system[

35]. The main conclusions are as follows:

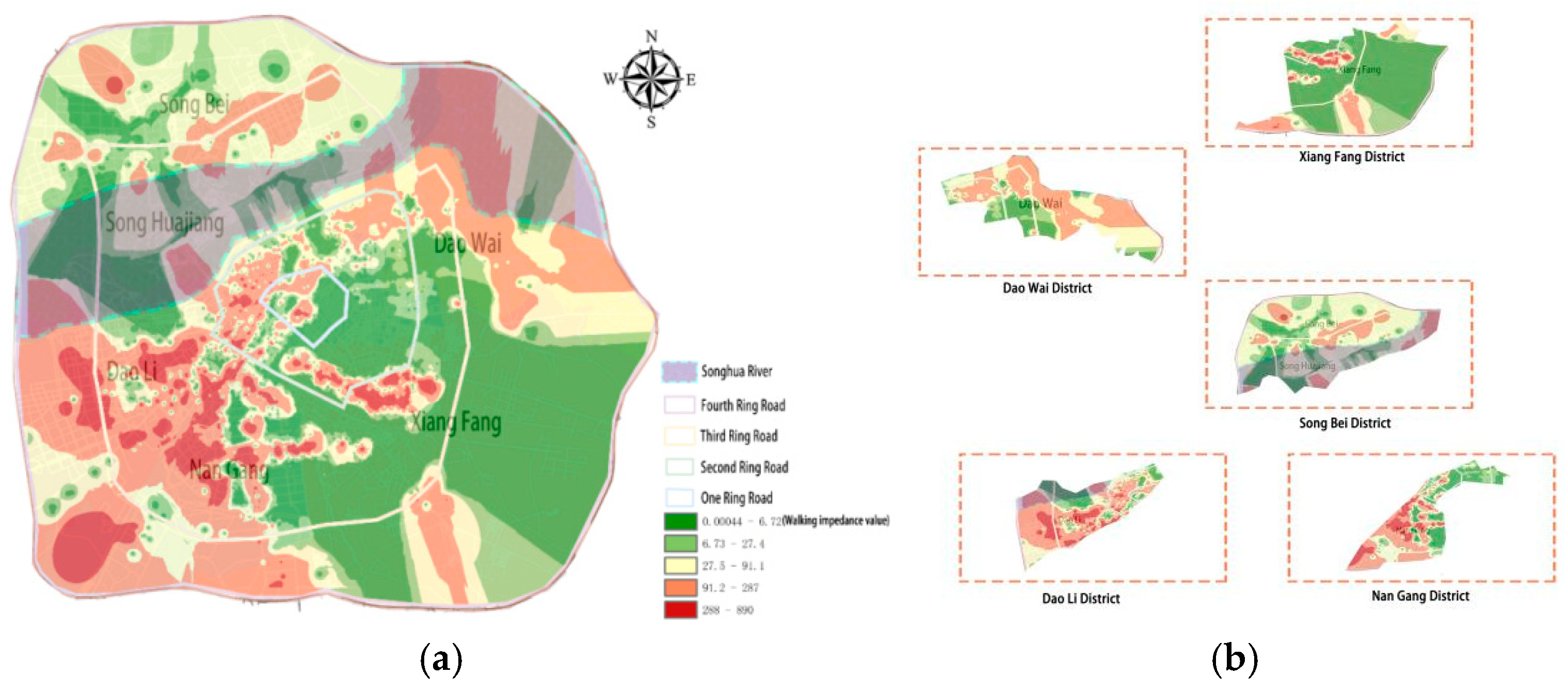

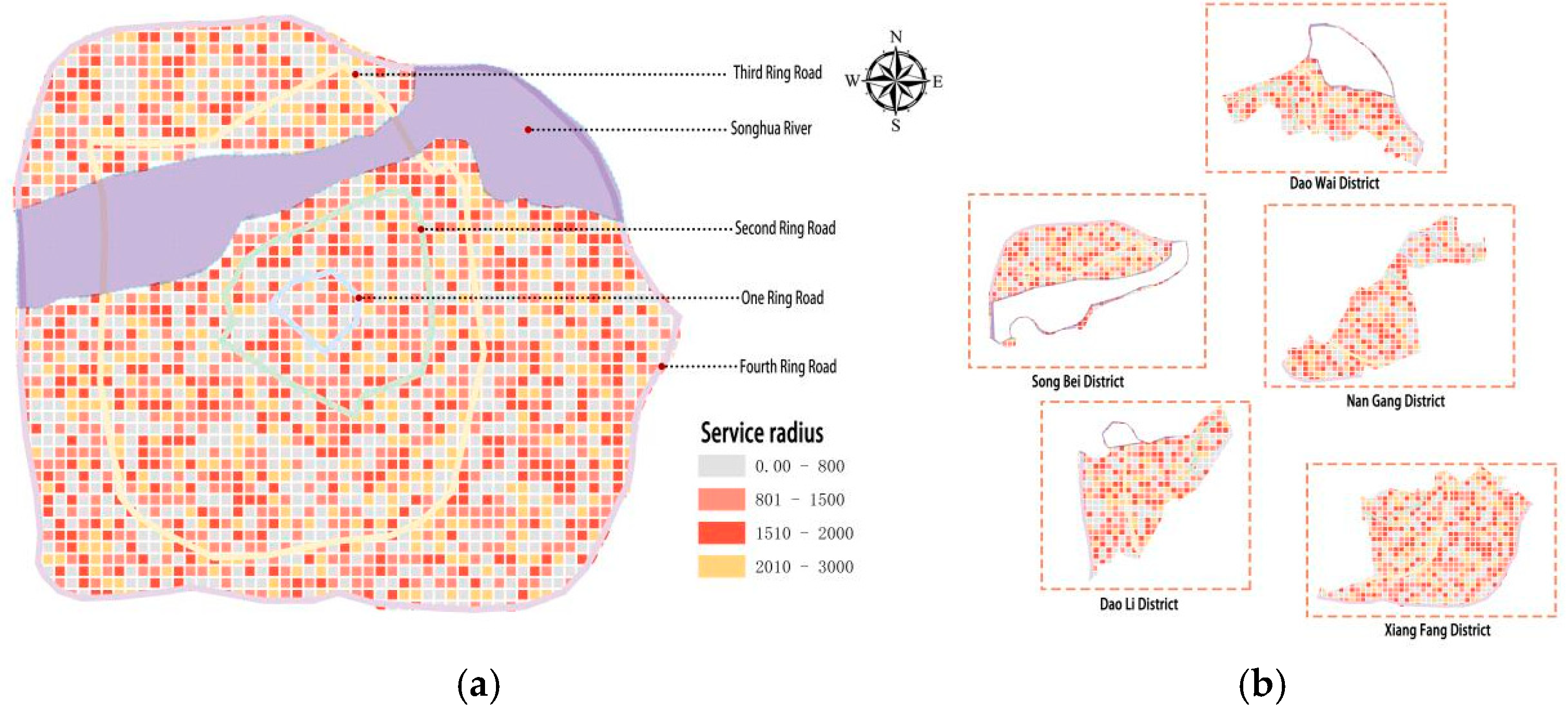

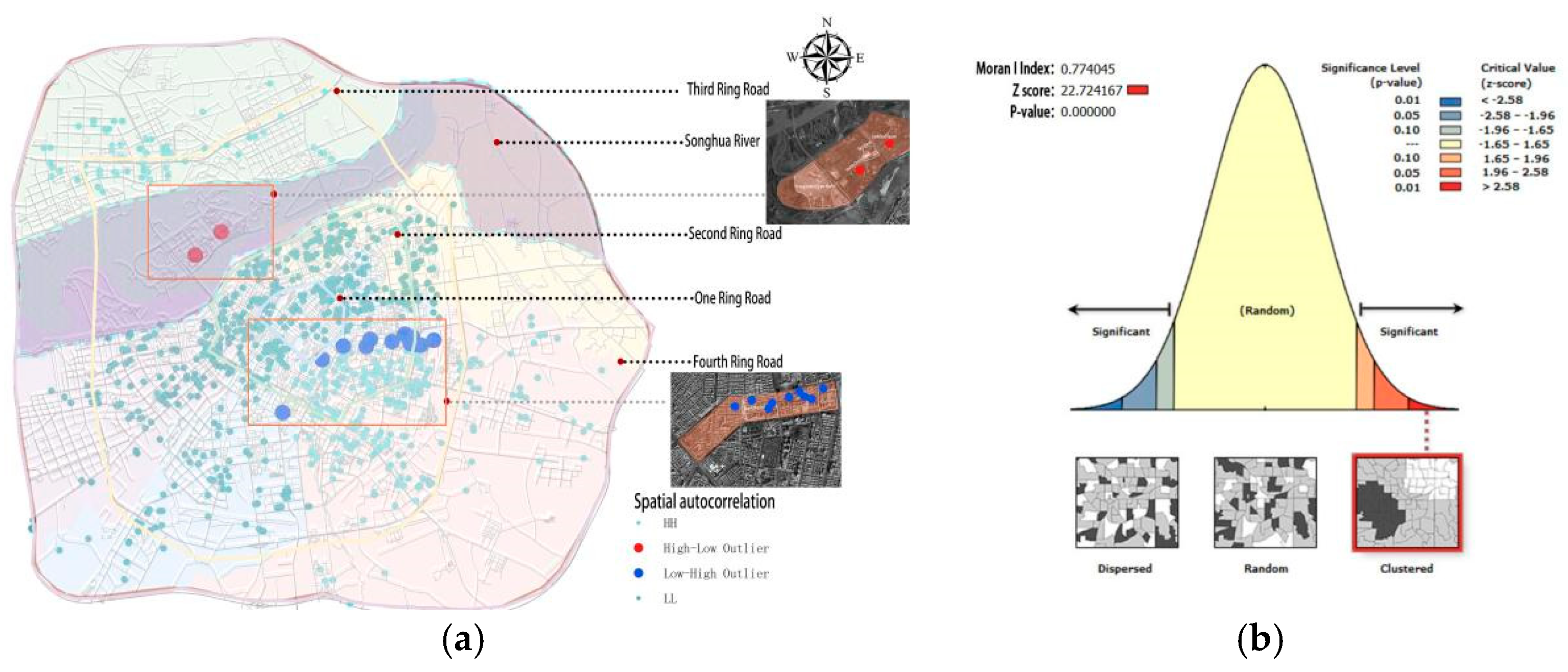

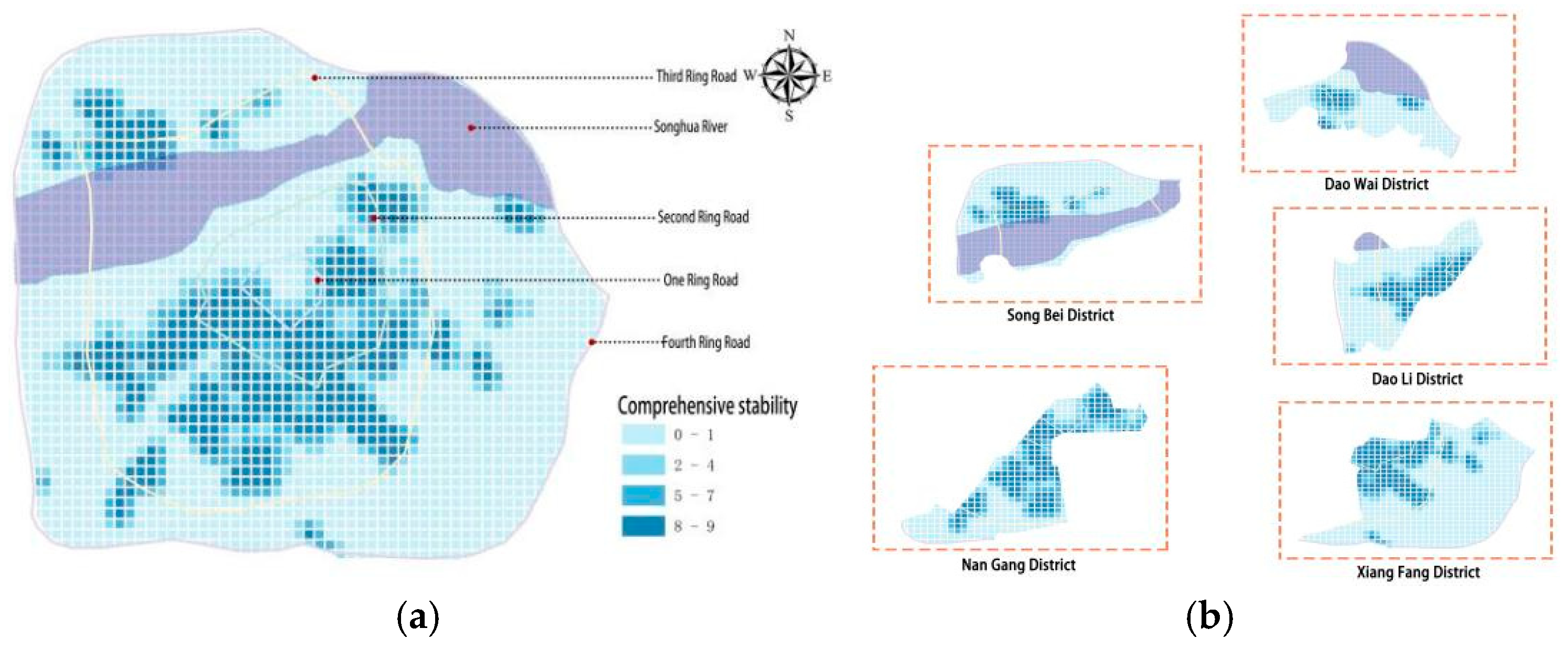

(1)Regarding the accessibility of residents' distances to medical treatment, there are significant differences among various administrative districts. The most convenient area is Nangang District, as it is located in the main urban region, resulting in a significantly higher level of convenience compared to other areas. In contrast, both Songbei District and Daowai District are not very convenient due to the current state and functionality of the land, this causes an uneven distribution of basic healthcare resources, making medical care inconvenient for residents.

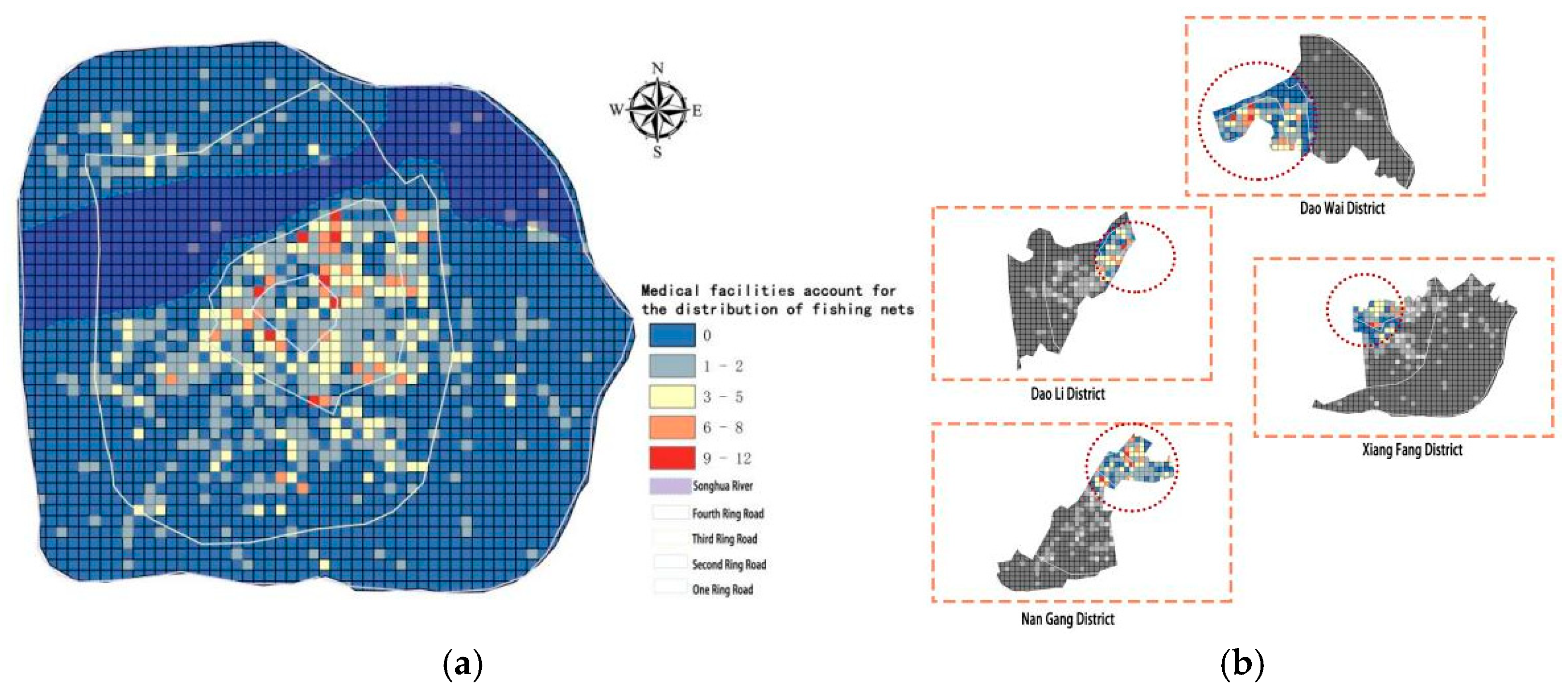

(2)An analysis of the diversity of treatment options reveals an overall balanced pattern; however, due to the limited number of medical facilities in Songbei District and Daowai District, these areas show a trend of fewer diverse choices. In the southwestern region of Daoli District and the center of Songbei District, residents have limited diversity in their paths to clinics. Additionally, community hospitals established in Daowai District offer few diverse path choices for residents to reach them.

(3)An analysis of the stability of the healthcare system reveals that the H-L area is primarily distributed in the southern part of Songbei District, with over ten data points indicating areas of inefficiency. Overall, these points mainly occupy two concentrated regions. The consistency of the medical facility system in the northern part of Xiangfang District, the southern part of Songbei District, and the eastern part of Daowai District is relatively poor.

4.2. Optimization Analysis

4.2.1. Optimization Strategy

(1)On the transmissibility of medical treatment : To significantly enhance the accessibility of grassroots hospitals in urban areas, improve the convenience of medical services for residents, and bolster overall spatial resilience, it is necessary to strategically increase medical resources in areas with low accessibility values and poor healthcare accessibility. Most streets within Songbei District and Daowai District face significantly low average accessibility, meaning that local residents encounter substantial difficulties in obtaining basic medical services. As a result, based on this practical consideration, priority should be given to optimizing the allocation of grassroots medical resources in these two critical regions: Songbei District and Daowai District.

(2)On the diversity of medical path choices : Songbei District and Daowai District exhibit a distinct lack of diversity in available paths to healthcare, which restricts residents' flexibility and convenience when addressing different medical needs. Based on detailed analytical results, targeted strategies can be proposed: Clinics are needed in the southern half of Daoli District, the center section of Songbei District to address inhabitants' primary healthcare needs. In contrast, Daowai District should focus on increasing the number of community hospitals to provide more comprehensive and specialized medical services.

(3)On the spatial equity matching pattern : The high-demand, low-supply (H-L) areas are primarily concentrated in the southern part of Songbei District. Due to high population density and significant medical demand, this area suffers from a striking imbalance between supply and request, driven by the relative scarcity of existing medical resources. Simultaneously, both the southern part of Songbei District and the eastern part of Daowai District are faced with insufficient medical facilities, necessitating the supplementation and upgrading of resources in subsequent development phases.

4.2.2. Demand and Resilience Conclusions

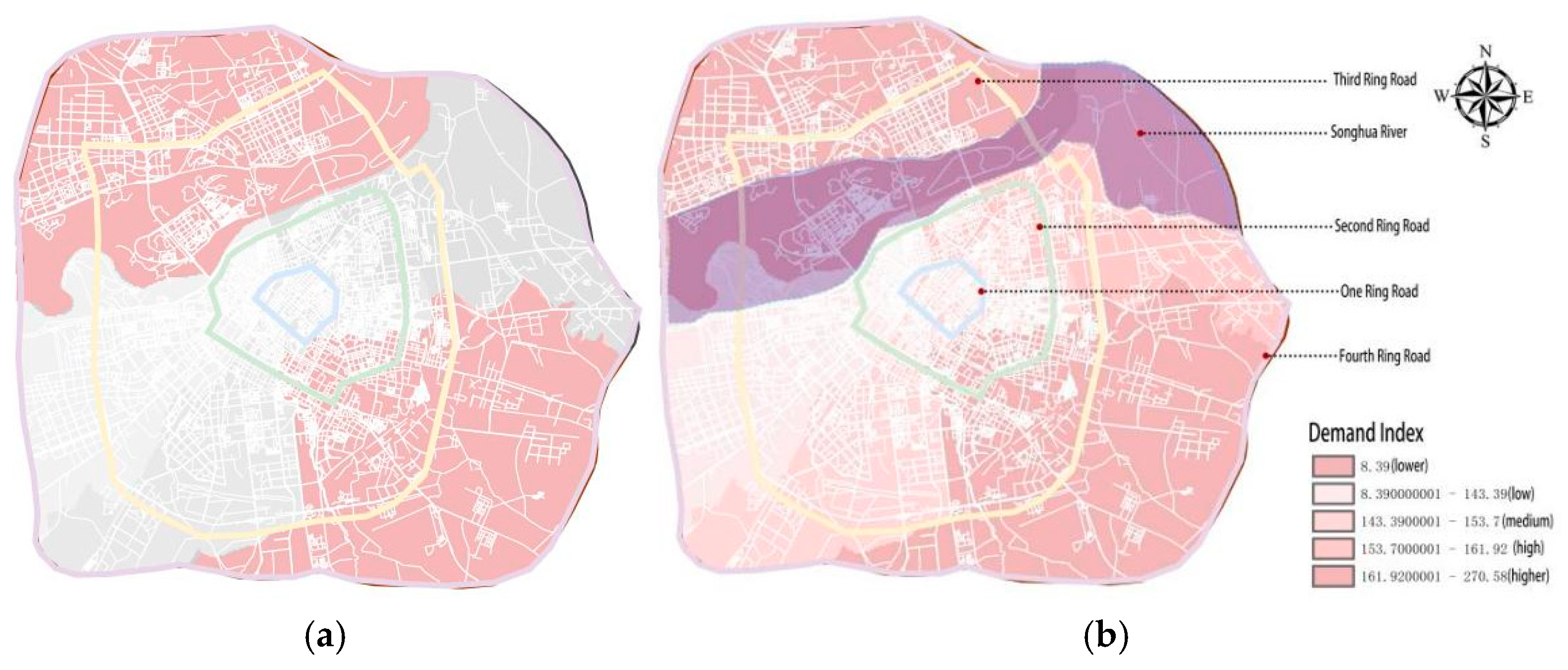

The analysis of medical service demand can primarily be assessed through two indicators: the total quantity of service requirement and the characteristics of service demand[

36]. The medical service demand as a whole is determined based on the population and morbidity rates in different subdivisions of Harbin's main urban area[

37]. Service demand density, on the other hand, refers to the total number of individuals with medical needs per unit area within each community[

38]. The relevant calculation formulas are as follows:

Among them: Q represents the aggregate quantity of patients in the area for two weeks; c represents the total population of the area[

39]; a represents the two-week prevalence rate of 1%(data source 《2008 China Health Service Survey 》 ); d represents the demand density of medical services in each region; Sk denotes the area of the K region[

40].

Using these two calculation formulas, the demand density for various districts in Harbin's main urban area can be derived. As illustrated in the diagram, the demand density rankings among the districts are as follows: Daoli District (low) < Nangang District (relatively low) < Daowai District (medium) < Songbei District (relatively high) < Xiangfang District (high). (See

Figure 19).

In order to better reflect the comprehensive visualization of the transferability, path diversity, and stability of medical facilities across different regions in Harbin's main urban area, as well as the resilience of medical resources, a geometric interval classification system has been employed. The resilience of healthcare facilities is categorized into four levels: “Good” (4), “Relatively Good” (3), “Medium” (2), and “Poor” (1). The quantity presented corresponds to the number of grids occupied by the facilities, as shown in

Table 5.

Table 5 indicates that the number of grids with good accessibility to medical facilities in the main urban area accounts for the majority, totaling 996. Among these grids, there are the most first-level medical facilities, amounting to 69. The number of grids at the relatively good level is 713. Overall, it can be concluded that the resilience level of healthcare facilities in Harbin's main urban area is relatively good.

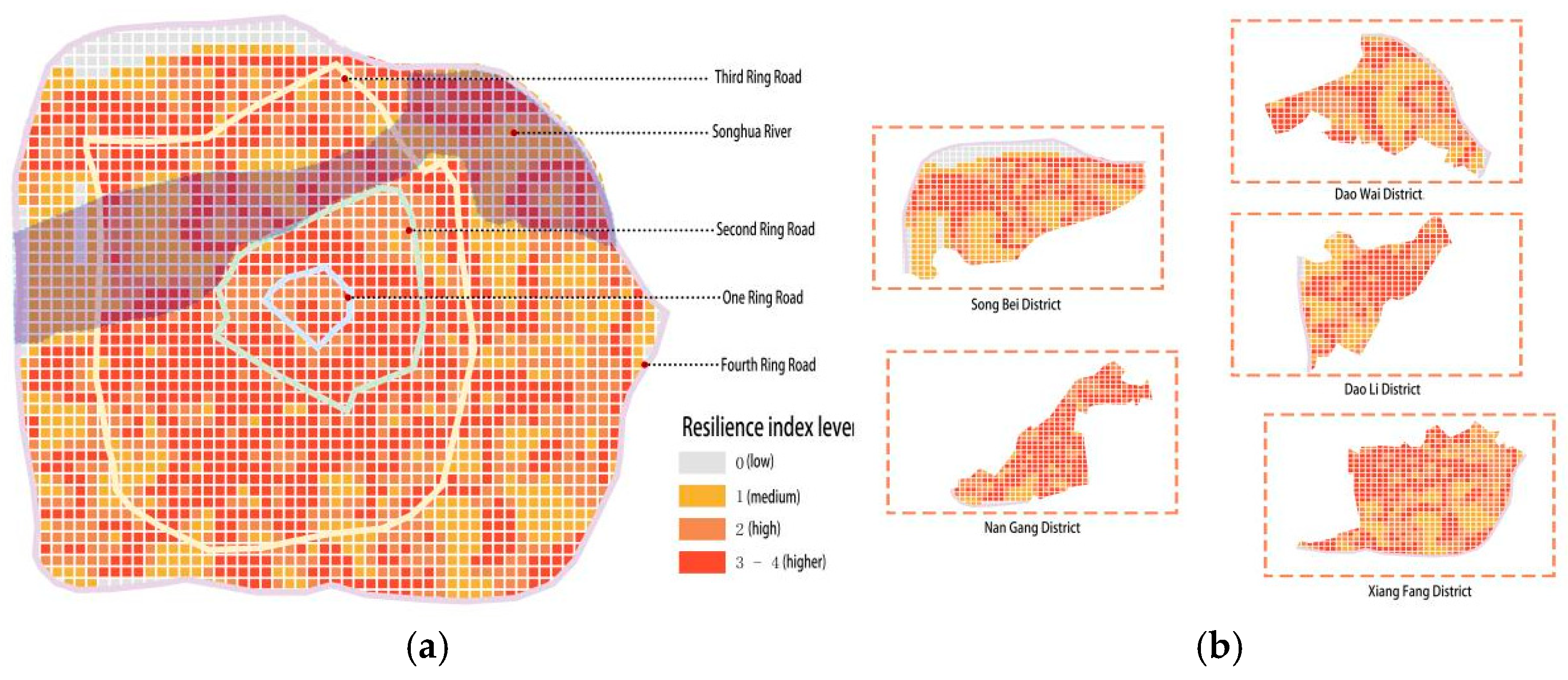

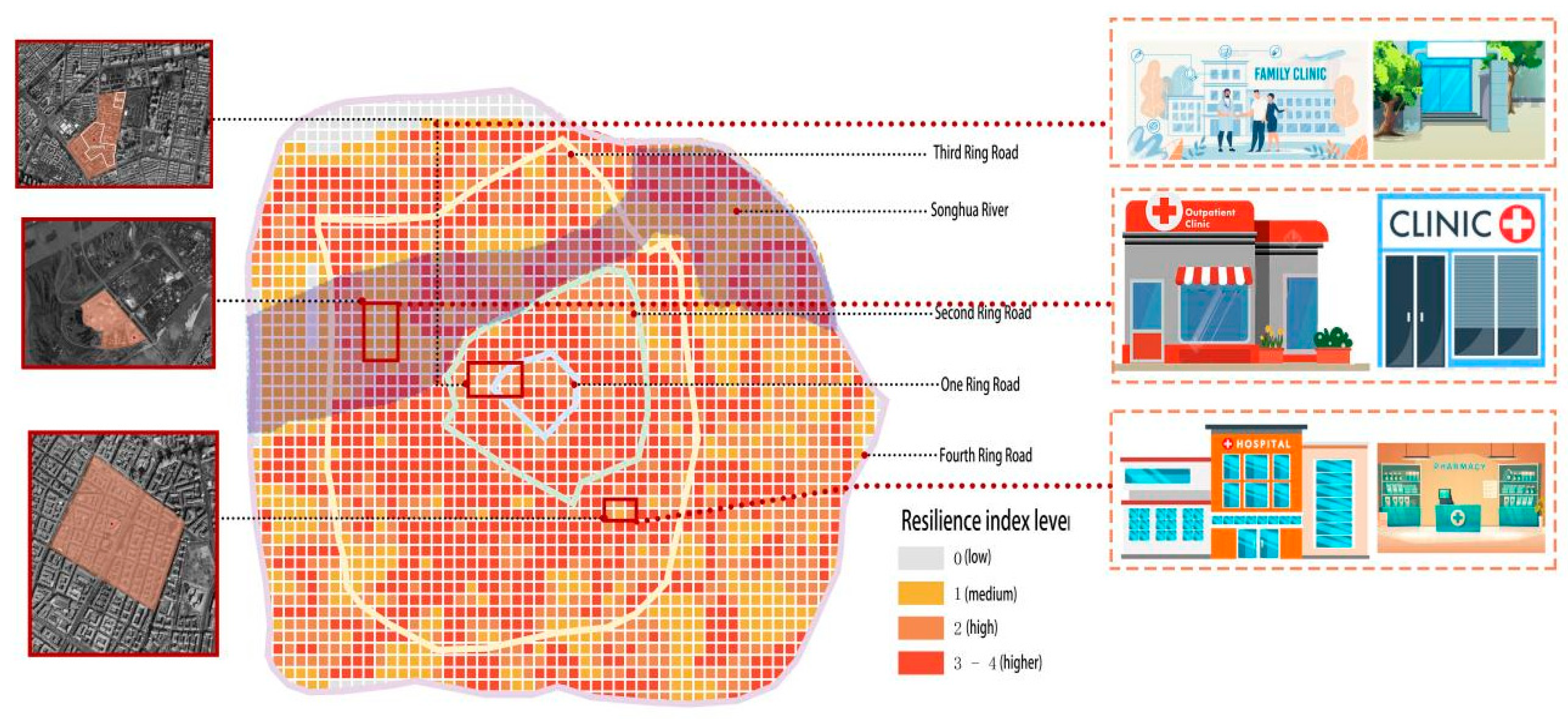

After conducting a spatial join of the data, images were created to visually represent the spatial conditions within various regions of Harbin's main urban area. The resilience is categorized into four levels: 0 (low), 1 (medium), 2 (high), and 3 (higher), as illustrated in

Figure 20.

From the figure, it can be observed that the southern part of Daoli District, the northeastern part of Nangang District, and the northern part of Xiangfang District exhibit the best resilience of medical facilities. These areas represent the economic and cultural center of Harbin's main urban area, characterized by high population density and the greatest number of first-level medical facilities, making them the regions with the optimal resilience of healthcare construction sites within the study area. Thus, it is evident that the overall resilience of medical facilities in Harbin's main urban area is relatively good.

The regions with better resilience are primarily located at the intersections of various districts, where population density is high and there are 29 medical facilities at the health clinic level. Additionally, due to the relatively developed transportation network in Harbin's main urban area, while these regions may not compete with the central area, their medical facility resilience remains good, allowing for convenient access to medical services.

Regions with moderate resilience are essentially areas that extend outward from the regions with the best resilience, mainly located in the northeastern part of Daoli District, the eastern part of Nangang District, and the eastern part of Xiangfang District. However, benefiting from the advantage of geographical distance, the resilience of medical facilities in these areas is at a moderate level.

Regions with poor resilience of medical facilities are found in the western part of Daoli District, the northern part of Songbei District, and the southeastern part of Daowai District. These areas are mostly located at the border between the main urban area and other townships, resulting in a greater distance from the central urban area, which contributes to the relatively poor resilience of medical facilities.

4.3. Optimize the Scheme

(1)Based on the analysis above, the southern part of Songbei District is characterized by its relatively independent entertainment areas, such as Ice and Snow World and Sun Island. Due to the presence of too many university campuses, there is a predominance of transient population over permanent residents. The area benefits from convenient transportation, including Metro Line 2 and efficient bus services. Considering the distribution of functional areas, it is evident that, apart from commercial entertainment zones, most areas are mixed-use and public office districts, primarily situated along major transportation routes. For such grids, in major traffic arteries and densely populated office areas, tertiary medical facilities,clinics should be added to enhance their service capacity, enabling them to meet and address basic medical needs, as well as the healthcare needs of tourists.

(2)In the eastern part of Daowai District, there should be an increase in secondary medical facilities—community hospitals. This area is situated in congested, older residential neighborhoods and has a large permanent resident population but fewer transient residents. Located within the Gongxingdun Street of Chengguan District, there is currently only one tertiary clinic in the region; however, its resilience index is commendable, and transportation is convenient. New large medical facilities cannot be constructed in this type of area, but residents can easily access tertiary medical points. Therefore, it is recommended to establish additional tertiary medical facilities to meet daily medical needs.

(3)The Changjiang Road and Heping Road streets in Xiangfang District serve as major activity areas for transient populations, characterized largely by mixed-use developments that combine commercial entertainment, public offices, and residential living. Medical resources are concentrated here, with close proximity to universities and several neighborhoods. The residential communities are located around Wanda Plaza, primarily featuring dining facilities along the streets, with fewer service-oriented establishments. Given the presence of large medical facilities in the vicinity, it is critical to guide residents in urban core neighborhoods to seek tiered treatment. For minor ailments and light conditions, residents could utilize secondary and tertiary medical facilities located near their residences. Additionally, efforts should be made to strengthen the service capacities of these secondary and tertiary fac ilities by increasing the number of medications, beds, and doctors available, thus alleviating the strain on primary medical facilities. Therefore,to serve the increased floating population, secondary and tertiary medical facilities should be added. (See

Figure 21)

5. Conclusions

This paper initiates with an examination of resilience characteristics and proposes the fundamental features of urban spatial resilience. By reflecting on the needs of urban residents, it introduces a grassroots medical and resilience framework based on "internal stability - diversity - high mobility." Through comprehensive analysis of various levels of facilities data, the paper explores the current status of medical facility distribution, concentration, accessibility, and optimization of layouts in unreasonable areas. Addressing these unreasonable regions while considering factors such as population mobility, road traffic potential, service capacity of resources, and the primary functions of land parcels, the study designs an optimized layout plan for the addition of medical facilities. The proposed optimization plan is more aligned with practical realities; the analysis of the three identified unreasonable areas, in conjunction with actual road conditions and surrounding service facilities, renders the results more convincing.

Although there is a wealth of data on medical facility locations in this study, there are instances within the site recommendation assessments where quantitative data support is lacking. Specifically, data on the number of beds and service capacity of medical facilities are missing, which decreases the persuasive power of the recommendations. Future methodologies will emphasize the integration of multi-source data and other approaches, fully addressing the reasonableness of recommended layouts, the availability of supporting data, and the absence of patient activity trajectory data. This will enhance the optimization capability for the site selection of medical facilities.

Figure 1.

Definition of medical facilities.

Figure 1.

Definition of medical facilities.

Figure 2.

Framework of the research process.

Figure 2.

Framework of the research process.

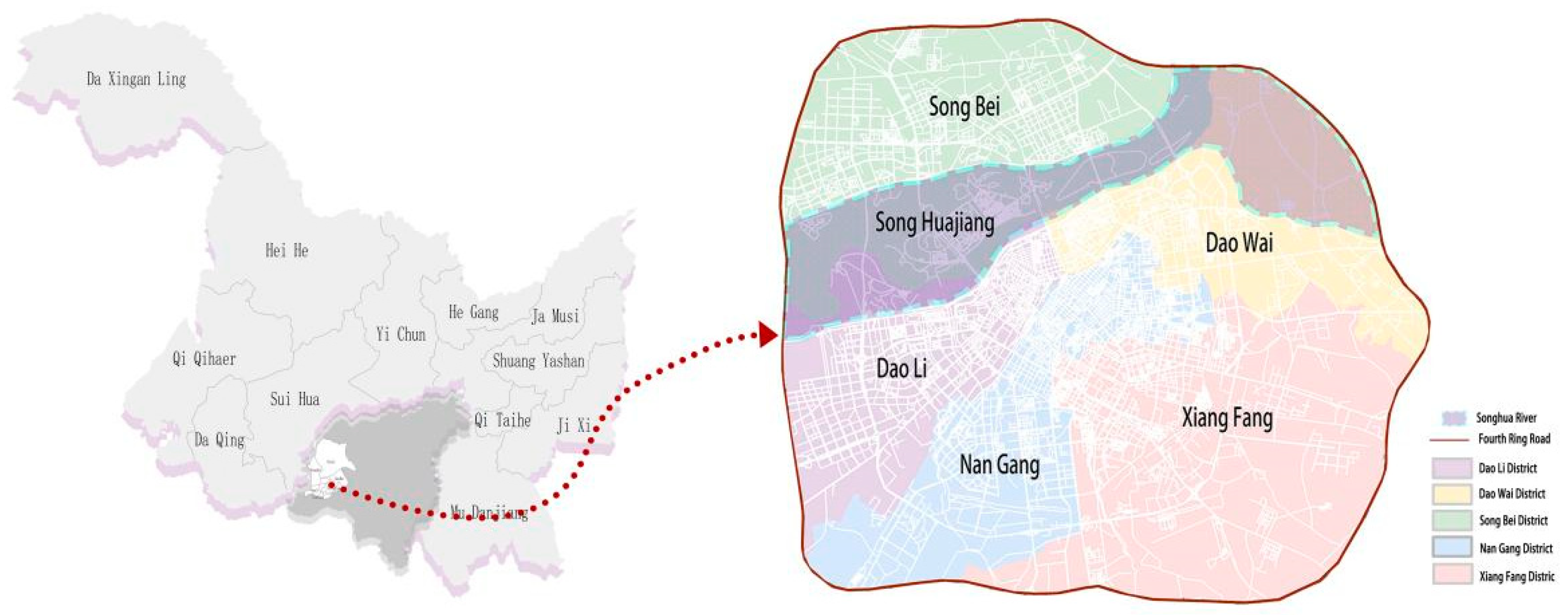

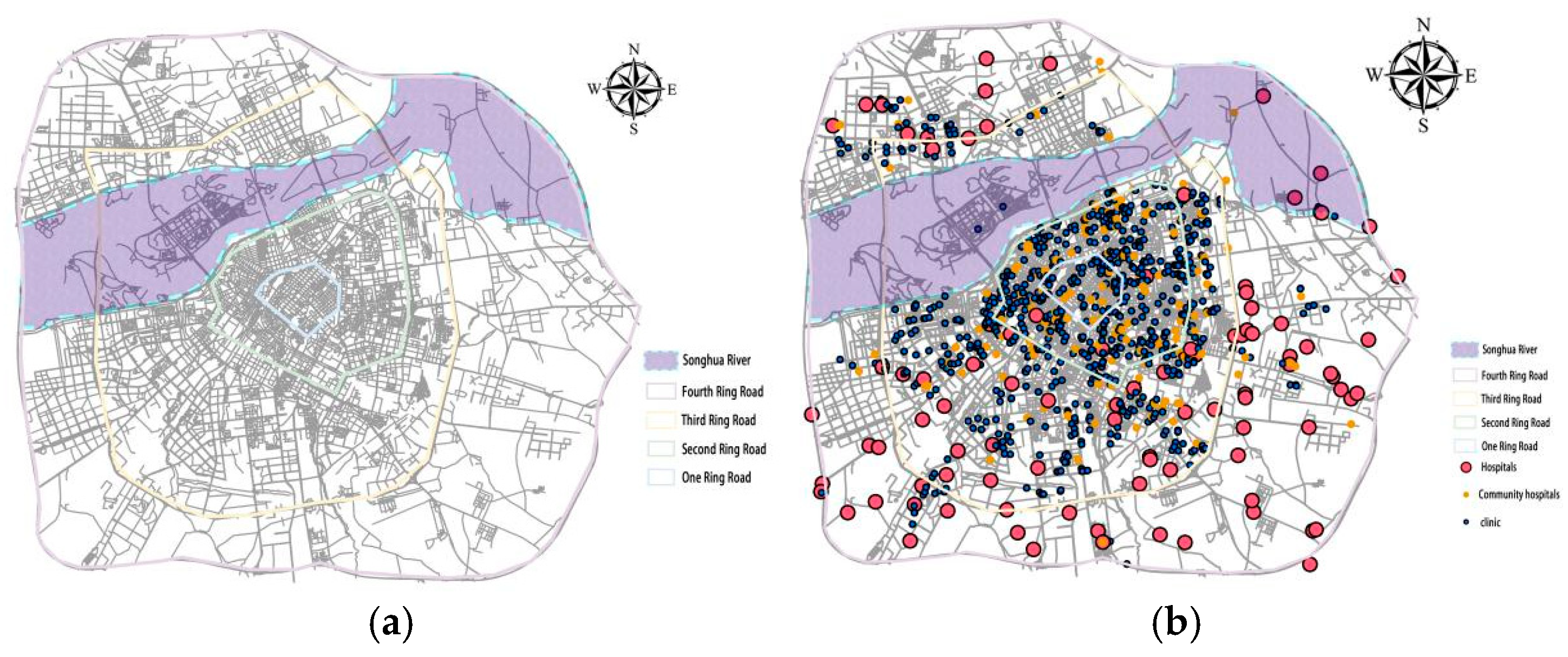

Figure 3.

Scope of the study, the central urban area of Harbin.

Figure 3.

Scope of the study, the central urban area of Harbin.

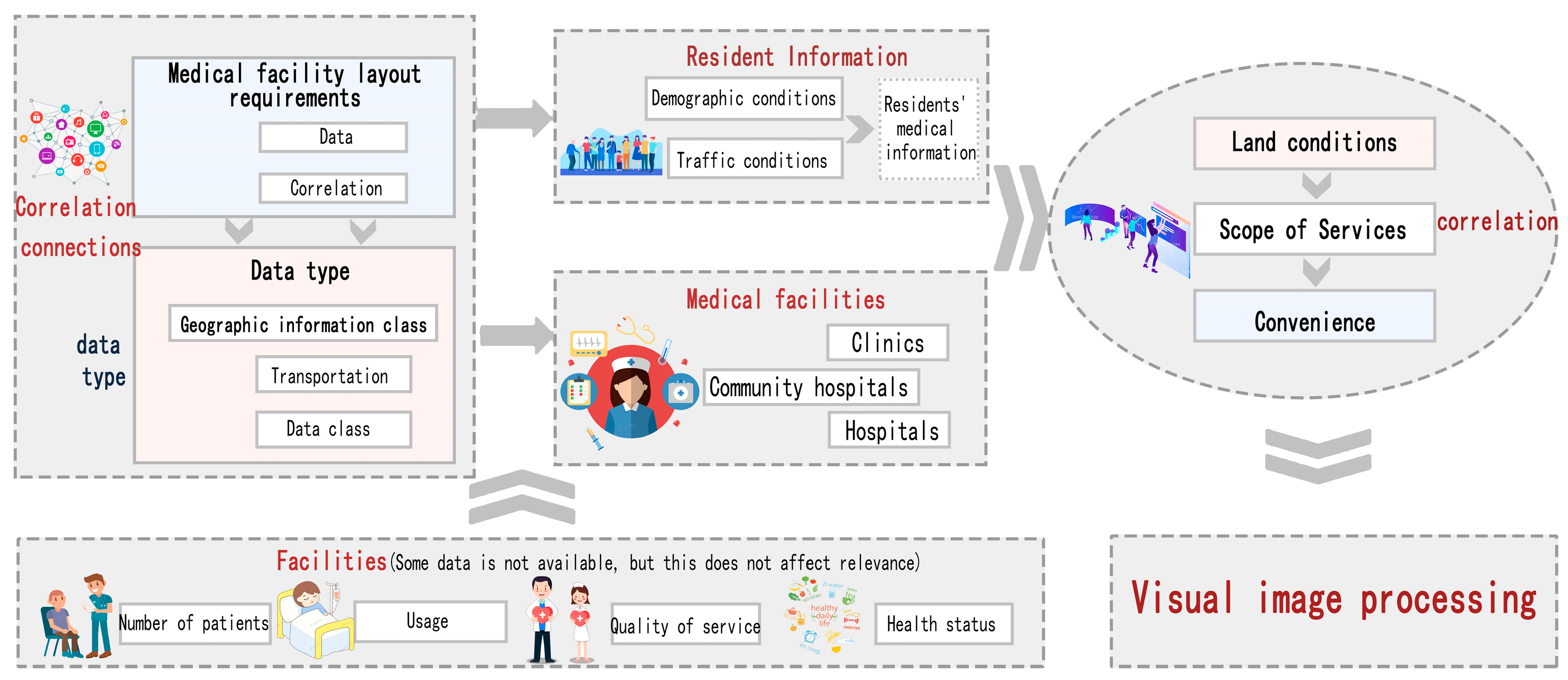

Figure 4.

Correlations between data.

Figure 4.

Correlations between data.

Figure 5.

(a)Database map(b)Distribution of medical resources.

Figure 5.

(a)Database map(b)Distribution of medical resources.

Figure 6.

Outline of the building(Note:The diagram shows the number of buildings with different numbers distributed around landmark buildings, and analyzes the distribution relationship between medical resources and buildings).

Figure 6.

Outline of the building(Note:The diagram shows the number of buildings with different numbers distributed around landmark buildings, and analyzes the distribution relationship between medical resources and buildings).

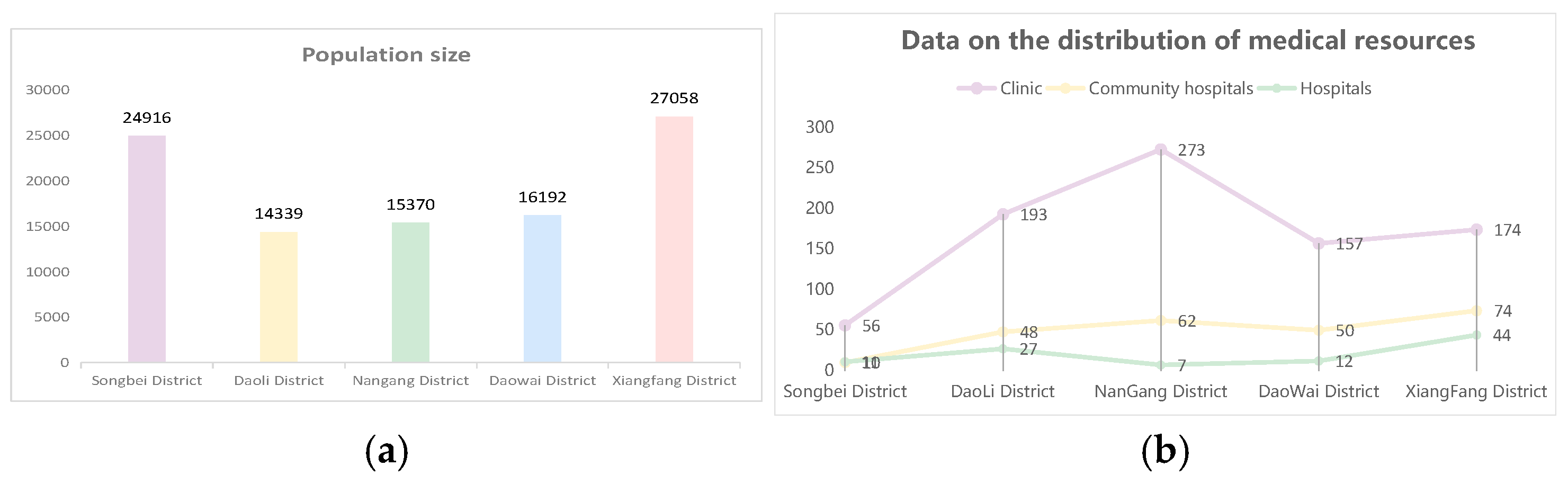

Figure 7.

Medical resource and population analysis charts(Note: This figure compares resources and population for demand and transmission analysis.).

Figure 7.

Medical resource and population analysis charts(Note: This figure compares resources and population for demand and transmission analysis.).

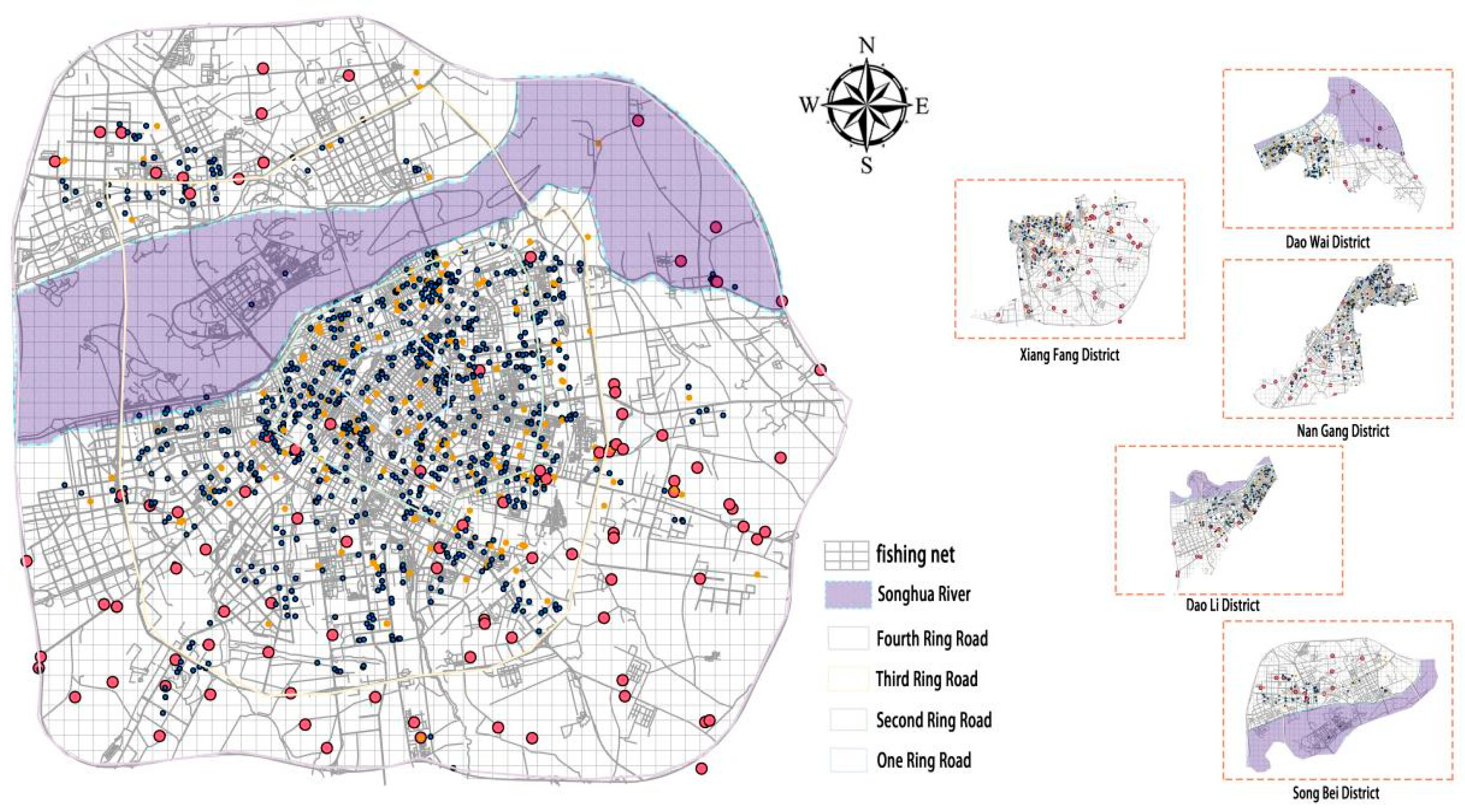

Figure 8.

Fishing net spatial analysis unit.

Figure 8.

Fishing net spatial analysis unit.

Figure 9.

Resilience and the framework of primary care facilities.

Figure 9.

Resilience and the framework of primary care facilities.

Figure 10.

(a)Pedestrian impedance analysis map of urban areas(b)Regional walking impedance analysis map.

Figure 10.

(a)Pedestrian impedance analysis map of urban areas(b)Regional walking impedance analysis map.

Figure 11.

(a)The area with the best road capacity(b)Regional road capacity analysis.

Figure 11.

(a)The area with the best road capacity(b)Regional road capacity analysis.

Figure 12.

(a)Distribution of the number of medical resources in the grid(b)Population distribution in a region(Note:In the diagram, it can be clearly seen that there are four areas with high concentration of medical resources).

Figure 12.

(a)Distribution of the number of medical resources in the grid(b)Population distribution in a region(Note:In the diagram, it can be clearly seen that there are four areas with high concentration of medical resources).

Figure 13.

(a)Analysis of the degree of concentration of medical facilities(b)Analysis of the Concentration Index of Medical Facilities.

Figure 13.

(a)Analysis of the degree of concentration of medical facilities(b)Analysis of the Concentration Index of Medical Facilities.

Figure 14.

(a)Analysis of urban service radius(b)Regional service radius analysis.

Figure 14.

(a)Analysis of urban service radius(b)Regional service radius analysis.

Figure 15.

(a)Analysis of the radius of clinic services(b)Community Hospital Service Radius Analysis(c)Analysis of the service radius of the health center.

Figure 15.

(a)Analysis of the radius of clinic services(b)Community Hospital Service Radius Analysis(c)Analysis of the service radius of the health center.

Figure 16.

(a)Spatial autocorrelation analysis(b)Spatial autocorrelation index analysis.

Figure 16.

(a)Spatial autocorrelation analysis(b)Spatial autocorrelation index analysis.

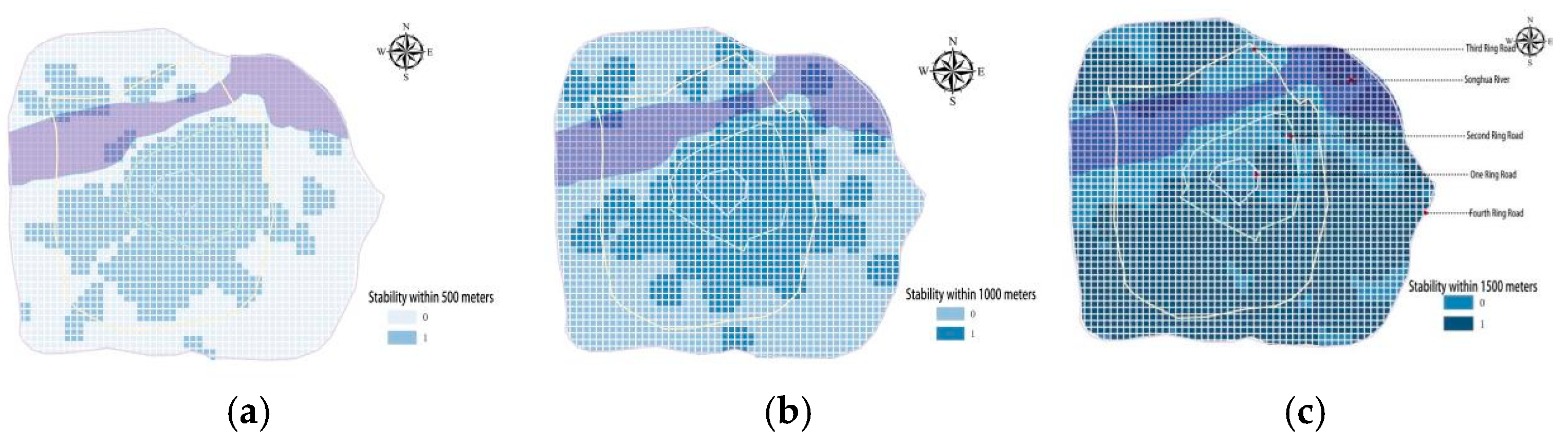

Figure 17.

(a)500 meters of medical resource stability(b)1000 meters of medical resource stability(c)1500 meters of medical resource stability.

Figure 17.

(a)500 meters of medical resource stability(b)1000 meters of medical resource stability(c)1500 meters of medical resource stability.

Figure 18.

(a)Stability map of urban areas(b)Regional stability map.

Figure 18.

(a)Stability map of urban areas(b)Regional stability map.

Figure 19.

(a)Map of disease demand density in the same area(b)Map of disease demand density in urban areas.

Figure 19.

(a)Map of disease demand density in the same area(b)Map of disease demand density in urban areas.

Figure 20.

(a)Resilience map of urban medical resources(b)Resilience map of regional medical resources.

Figure 20.

(a)Resilience map of urban medical resources(b)Resilience map of regional medical resources.

Figure 21.

Optimization diagram.

Figure 21.

Optimization diagram.

Table 2.

Proportion of medical resources.

Table 2.

Proportion of medical resources.

| Medical facilities |

Number of POIs |

Percentage |

| Hospitals |

101 |

8.43% |

| Community hospitals |

244 |

20.37% |

| Clinic |

853 |

71.20% |

Table 3.

Quantitative results of accessibility by administrative region.

Table 3.

Quantitative results of accessibility by administrative region.

| Region |

Transfer value |

Transmission difference |

| Daoli District |

0.005163 |

0.004837 |

| DaoWai District |

0.002285 |

0.007715 |

| NanGang District |

0.009024 |

0.000976 |

| Songbei District |

0.003957 |

0.006043 |

| XiangFang District |

0.004062 |

0.005938 |

Table 4.

The distribution of medical resources in the service area.

Table 4.

The distribution of medical resources in the service area.

| Medical resources |

0—800meters |

801——1500meters |

1501——2000meters |

2001——3000meters |

| clinic |

228 |

170 |

|

|

| Community hospitals |

44 |

51 |

42 |

|

| Hospitals |

23 |

34 |

26 |

18 |

Table 5.

Classification of the resilience level of medical facilities in the main urban area of Harbin.

Table 5.

Classification of the resilience level of medical facilities in the main urban area of Harbin.

| Toughness level |

Number of meshes |

Number of medical facilities |

Number of first-class medical facilities |

| good(4) |

996 |

785 |

63 |

| Relatively good(3) |

713 |

329 |

29 |

| medium(2) |

613 |

64 |

9 |

| poor(1) |

160 |

0 |

0 |