Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

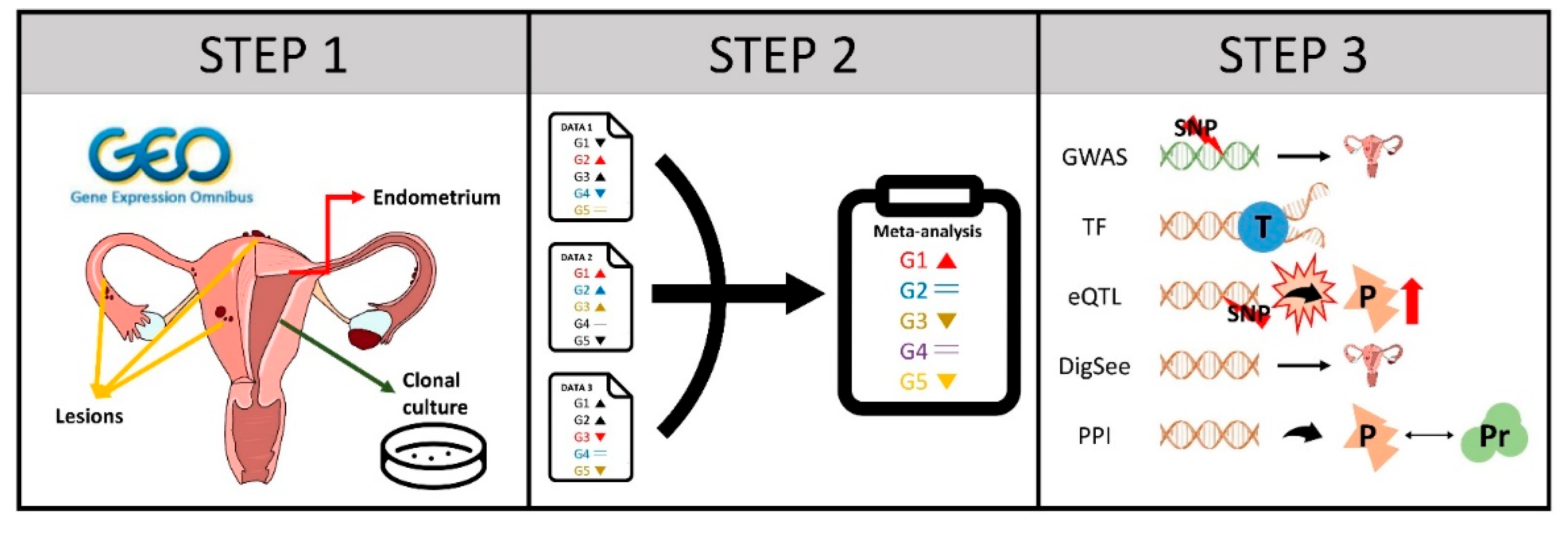

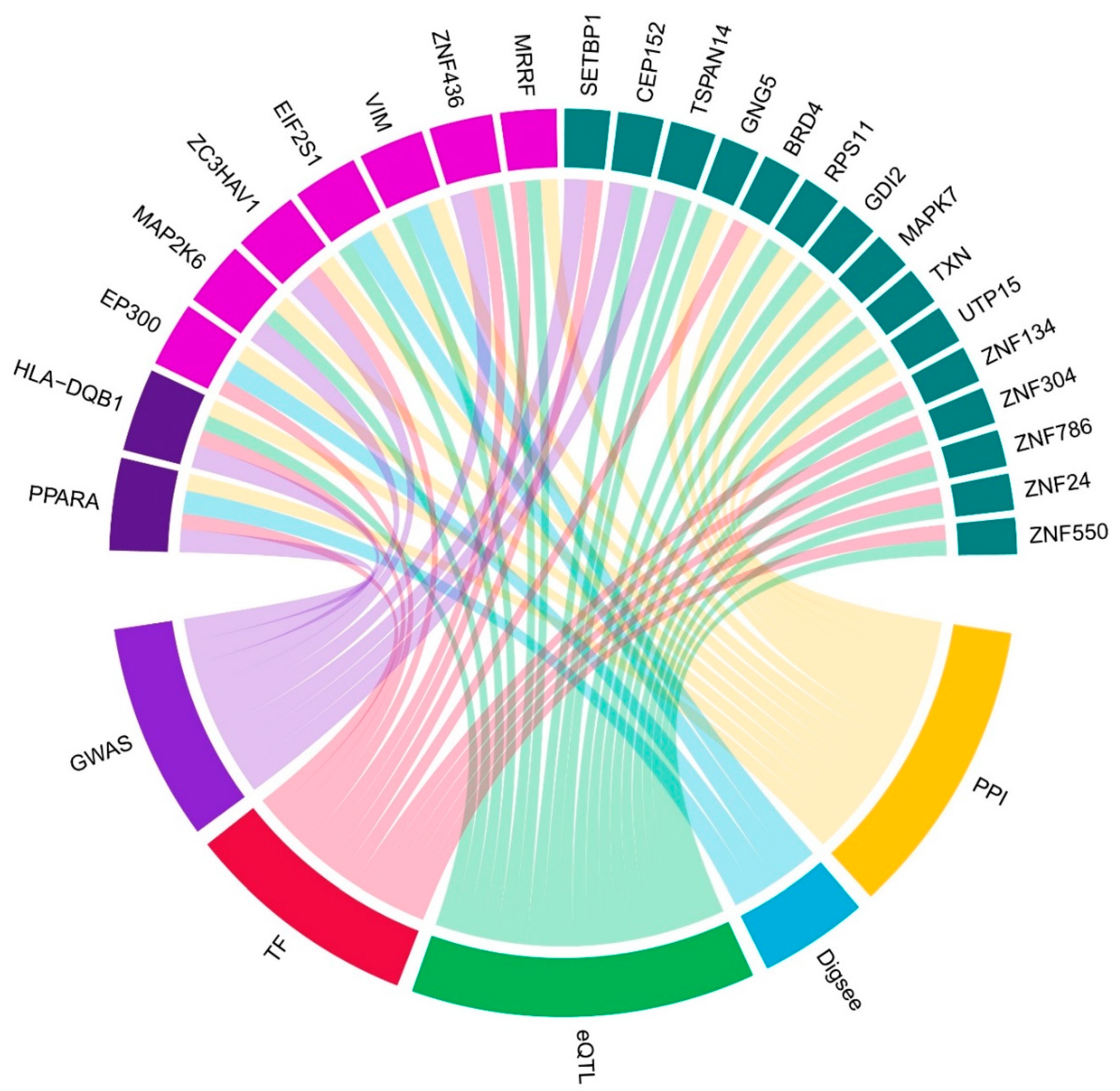

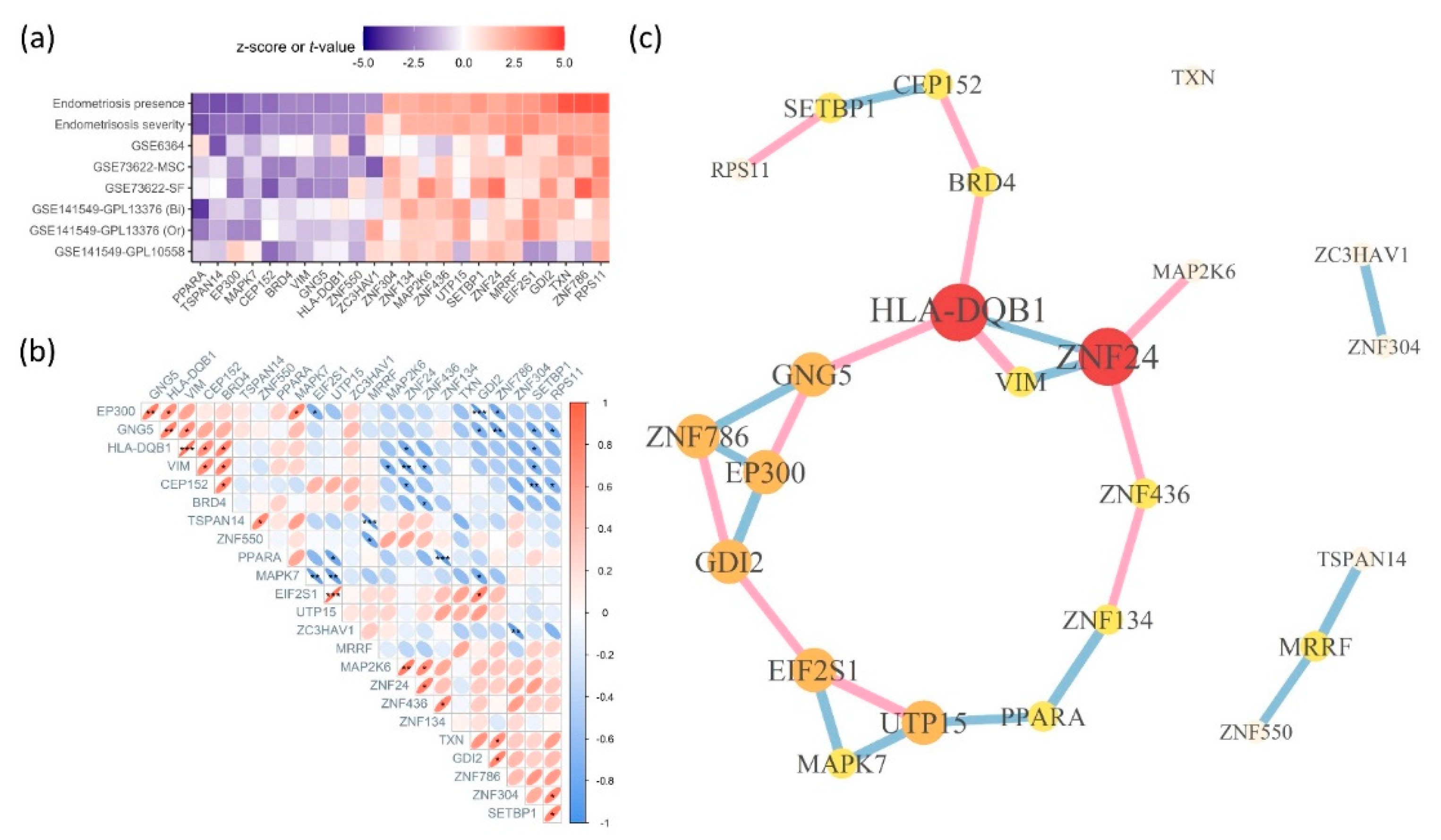

Endometriosis is a complex disease with diverse etiologies, including hormonal, immunological, and environmental factors; however, its exact pathogenesis remains unknown. While surgical approaches are the diagnostic and therapeutic gold standard, identifying endometriosis-associated genes is a crucial first step. Endometriosis-related five gene expression studies were selected from the available datasets. Approximately, 14,167 genes common to these five datasets were analyzed for differential expression. Meta-analyses utilized fold-change values and standard errors obtained from each analysis, with the binomial and continuous datasets contributing to the endometriosis presence and endometriosis severity meta-analysis, respectively. Approximately, 160 genes showed significant results in both meta-analyses. For Bayesian analysis, endometriosis-related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the human transcription factor catalog, uterine SNP-related gene expression, disease-gene databases, and interactome databases were utilized. Twenty-four genes, present in at least three or more databases, were identified. Network analysis based on Pearson's correlation coefficients revealed HLA-DQB1 gene with both a high score in the Bayesian analysis and a central position in the network. Although ZNF24 had a lower score, it occupied a central position in the network, followed by other ZNF family members. Bayesian analysis identified genes with high confidence that could support discovering key diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for endometriosis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

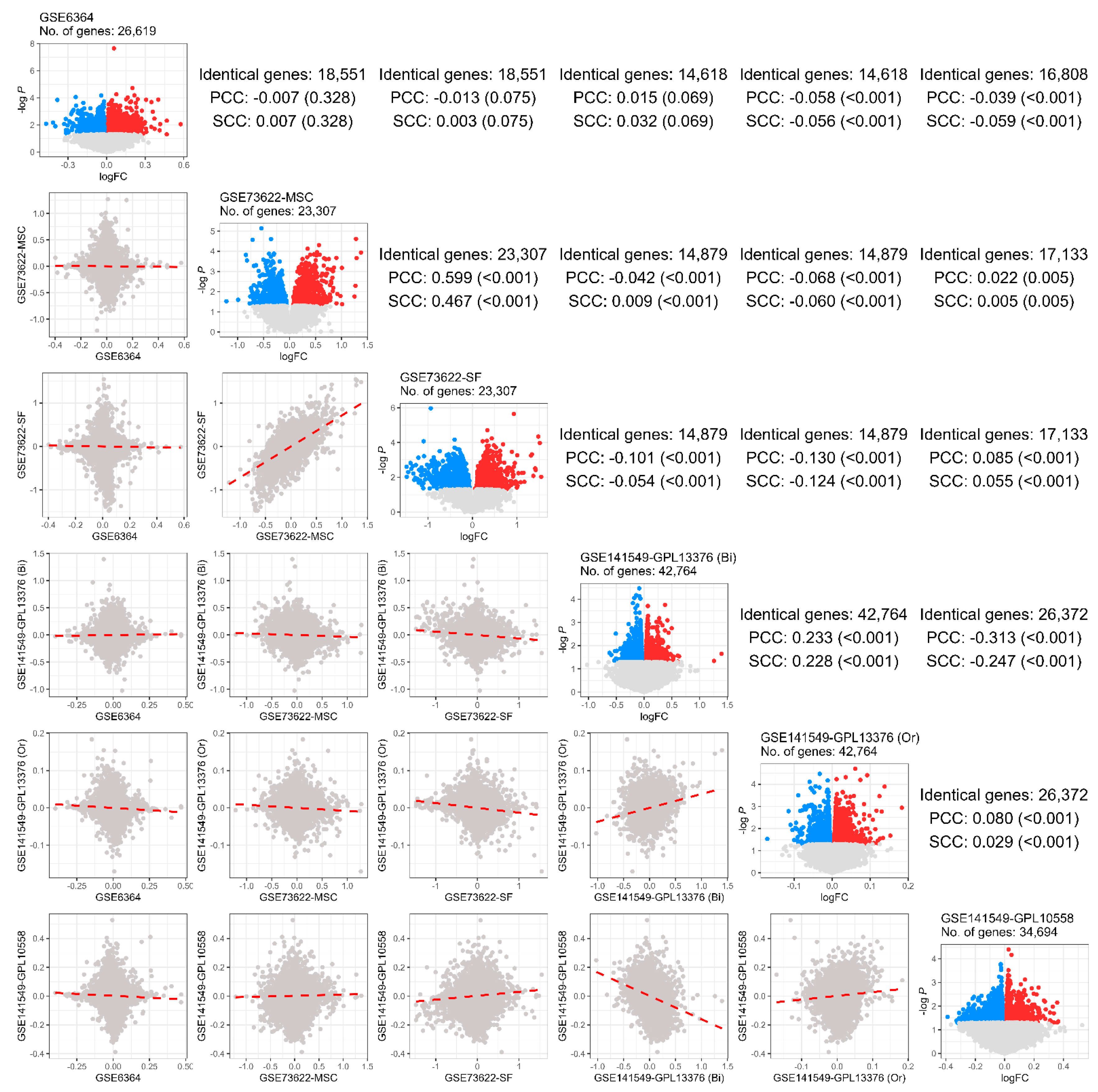

2.1. Data Exploration and Selection

2.2. Differential Expression Analysis

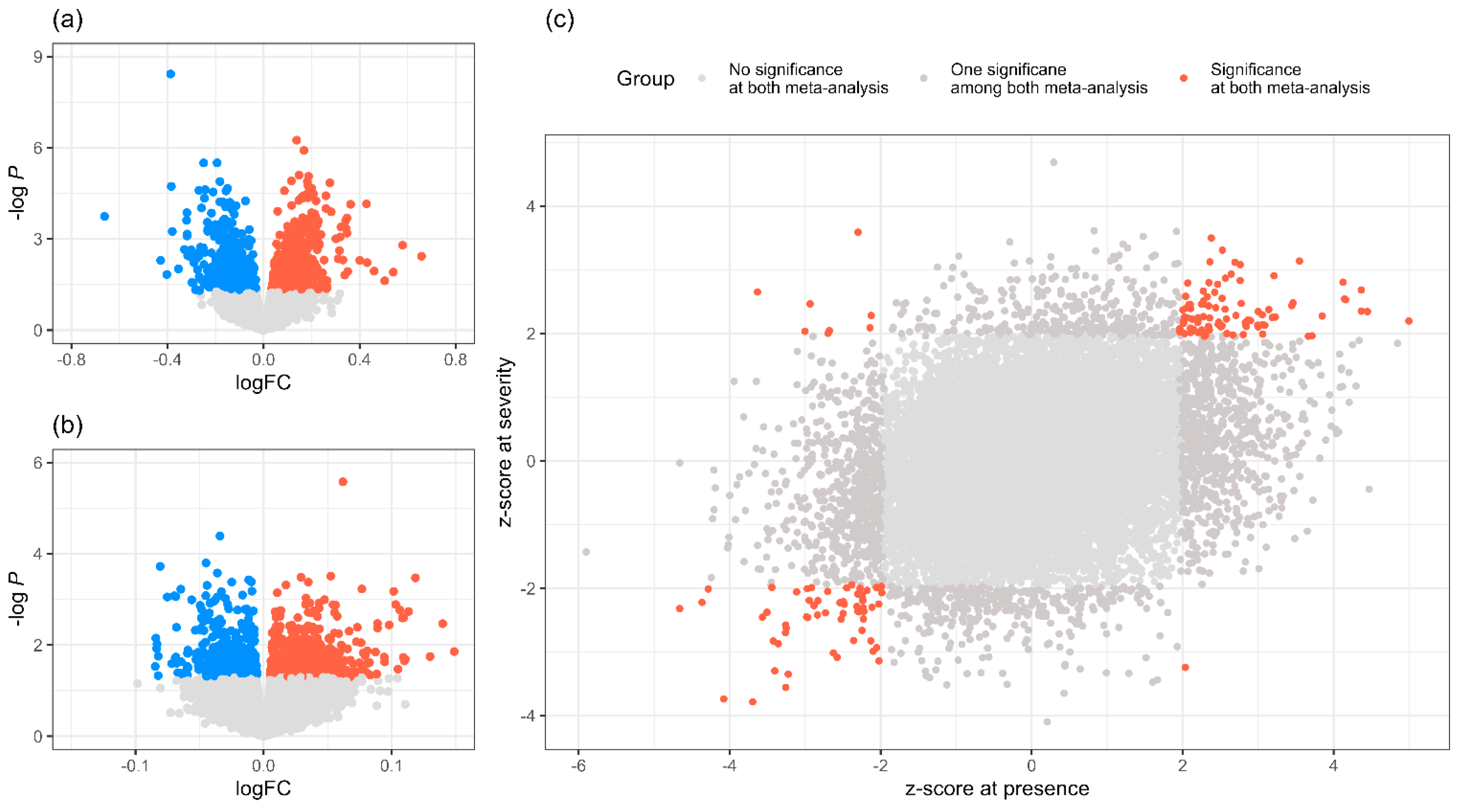

2.3. Meta-Analysis

2.4. Bayesian Analysis of Endometriosis Severity Related Genes

2.5. Correlation and Network Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Pre-Processing

4.2. Differenctial Expression Analysis

4.3. Meta-Analysis

4.4. Bayesian Analysis

4.5. Correlation and Network Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giudice, L.C.; Kao, L.C. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, M.H.R; Farooqui, N.; Zuberi, N.; Ashraf, M.; Azhar, A.; Baig, R.; Badar, B.; Rehman, R. Endometriosis, infertility and MicroRNA's: a review. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J.A. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1927, 14, 422–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burney, R.O.; Giudice, L.C. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, A.W.; Missmer, S.A. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. BMJ 2022, 379, e070750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, J.D.; Li, A.H.; Marcketta, A.; Sun, D.; Mbatchou, J.; Kessler, M.D.; Benner, C.; Liu, D.; Locke, A.E.; Balasubramanian, S.; et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature 2021, 599, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.A.; Jolma, A.; Campitelli, L.F.; Das, P.K.; Yin, Y.; Albu, M.; Chen, X.; Taipale, J.; Hughes, T.R.; Weirauch, M.T. The human transcription factors. Cell 2018, 172, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, J.; Thomas, J.; Salvatore, M.; Phillips, R.; Lo, E.; Shad, S.; Hasz, R.; Walters, G.; Garcia, F.; Young, N.; et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.-J.; Lee, H. An analysis of diease-gene relationship from Medline abstracts by DigSee. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaflik, T.; Romanowicz, H.; Szyłło, K; Kołaciński, R.; Michalska, M.M.; Samulak, D.; Smolarz, B. Analysis of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) UCA1, MALAT1, TC0101441, and H19 expression in endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11583. [CrossRef]

- Bozdag, G. Recurrence of endometriosis: risk factors, mechanisms and biomarkers. Womens Health (Lond) 2015, 11, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.; Hwang, S.; Seo, D.M.; Shin, H.C.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Uh, Y. Identification of cardiovascular disease-related genes based on the co-expression network analysis of genome-wide blood transcriptome. Cells 2022, 11, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium, The gene ontology resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D330–D338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, C.J.; Li, Y.; Abecasis, G.R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2190–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, V.; Falciani, F.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.A. DNA microarrays: a powerful genomic tool for biomedical and clinical research. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghese, B.; Mondon, F.; Noël, J.-C.; Fayt, I.; Mignot, T.-M.; Vaiman, D.; Chapron, C. Gene expression profile for ectopic versus eutopic endometrium provides new insights into endometriosis oncogenic potential. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 2557–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hever, A.; Roth, R.B.; Hevezi, P.; Marin, M.E.; Acosta, J.A.; Acosta, H.; Rojas, J.; Herrera, R.; Grigoriadis, D.; White, E.; et al. Human endometriosis is associated with plasma cells and overexpression of B lymphocyte stimulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 12451–12456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaresis, J.S.; Irwin, J.C.; Goldfien, G.A.; Rabban, J.T.; Burney, R.O.; Nezhat, C.; DePaolo, L.V.; Giudice, L.C. Molecular classification of endometriosis and disease stage using high-dimensional genomic data. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 4986–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gu, C.; Ye, M.; Zhang, Z.; Han, W.; Fan, W.; Meng, Y. Identification of global transcriptome abnormalities and potential biomarkers in eutopic endometria of women with endometriosis: a preliminary study. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 6, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Oksvold, P.; Kampf, C.; Djureinovic, D.; Odeberg, J.; Habuka, M.; Tahmasebpoor, S.; Danielsson, A.; Edlund, K.; et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2014, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyadera, H. , Tokunaga, K. Associations of human leukocyte antigens with autoimmune disease: challenges in identifying the mechanism. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 60, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramgopal, S.; Rathika, C.; Malini, R.P.; Murali, V.; Arun, K.; Balakrishnan, K. Critical amino acid variations in HLA-DQB1* molecules confers susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid disease in south India. Genes. Immun. 2019, 20, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, C.; Wei, S.; Tao, J.; Jia, Z.; Chen, X.; Lv, W.; Lv, H.; Tang, G.; et al. Epigenome-wide methylation haplotype association analysis identified HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRB5 and HLA-DRB1 as risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2023, 50, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.K. , Moreira, B., Neuman, M.G. Pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver a narrative review. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, M.; Li, N.; Yan, C.; Guo, H.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q. Gemfibrozil alleviates cognitive impairment by inhibiting ferroptosis of astrocytes via restoring the iron metabolism and promoting antioxidant capacity in type 2 diabetes. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergialiotis, V.; Frountzas, M.; Fasoulakis, Z.; Daskalakis, G.; Chrisochoidi, M.; Kontzoglou, K.; Perrea, D.N. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) as a regulator of the angiogenic profile of endometriotic lesions. Cureus 2022, 14, e22616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Tu, D.; Li, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Jin, W.; Li, T.; Zhu, H. The diagnostic significance of the ZNF gene family in pancreatic cancer: a bioinformatics and experimental study. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1089023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Li, L.; Wang, P.; Feng, Q.; Pan, X.; Lin, P.; Song, S.; Yang, L.; Yang, J. ZNF24 regulates the progression of KRAS mutant lung adenocarcinoma by promoting SLC7A5 translation. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1043177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, A.; Yan, A.; Yao, J.; Huang, H.; Gao, Z.; Han, T.; Gu, J.; Li, N.; Wu, H.; et al. Circular RNA MTCL1 promotes advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma progression by inhibiting C1QBP ubiquitin degradation and mediating beta-catenin activation. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, J.A.; Potashkin, J.A. Evaluation of RNA blood biomarkers in individuals at risk of Parkinson's disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2017, 7, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strande, N.T.; Riggs, E.R.; Buchanan, A.H.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O; DiStefano, M.; Dwight, S.S.; Goldstein, J.; Ghosh, R.; Seifert, B.A.; Sneddon, T.P.; et al. Evaluating the clinical validity of gene-disease associations: an evidence-based framework developed by the clinical genome resource. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 895–906. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).