1. Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder among reproductive-aged women, with a global prevalence of 8–13 % [

1]. Defined by the 2003 Rotterdam criteria [

2], PCOS is characterized by chronic anovulation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology [

3]. Beyond the ovary, accumulating evidence indicates that the endometrium of women with PCOS displays persistent histological and molecular alterations, including abnormal proliferation, impaired decidualization, chronic low-grade inflammation, and compromised angiogenesis—collectively referred to as PCOS endometrial dysfunction [

4,

5,

6]. These changes not only impair implantation and increase miscarriage rates [

7], but also elevate long-term risks for endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma [

8].

Current diagnosis relies on invasive endometrial biopsy followed by subjective histological dating, which is poorly reproducible and impractical for routine screening [

9]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for objective, minimally invasive molecular biomarkers [

10]. High-throughput transcriptomic studies have generated extensive public data, yet no integrative analysis has derived an externally validated gene signature for this specific phenotype [

11].

In this study, we leveraged three independent endometrial microarray datasets to identify robust differentially expressed genes (DEGs), elucidate their biological pathways, and construct a LASSO-based diagnostic signature. By validating the signature in an external cohort, we aimed to provide a reproducible, readily applicable tool for early diagnosis and risk stratification of PCOS-related endometrial dysfunction.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Three publicly available endometrial microarray datasets (GSE103465, GSE4888, GSE51901) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

GSE103465 (Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0) contains 9 proliferative-phase endometrial biopsies from PCOS patients and 9 matched controls.;

GSE4888 (Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0) contains 10 PCOS and 9 control samples;

GSE51901 (Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome) contains 12 PCOS and 12 control samples;

Raw CEL or TXT files were log2-transformed and normalized using the robust multi-array average (RMA) or quantile normalization as appropriate [

12]. Probes without corresponding gene symbols or mapping to multiple loci were removed; when multiple probes mapped to the same gene, the probe with the highest mean expression was retained. A graphical overview of the study workflow is provided as Figure 1 (see Additional file 1: Graphical Abstract).

2.2. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PCOS and control endometrium were identified using the limma package (v3.50.3) in R (v4.2.2).

Criteria: |log₂ fold-change (FC)| > 1 and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 [

13];

Batch effects across datasets were corrected using the ComBat function from the sva package [

14];

2.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed using clusterProfiler (v4.6.2) [

15].

2.4. Construction of the LASSO Diagnostic Signature

A LASSO logistic regression model was employed to select the most predictive genes for PCOS endometrial dysfunction [

16].

Input: expression matrix of all DEGs across the training cohort (GSE103465 + GSE4888, n = 37);

Implementation: glmnet package (α= 1, 10-fold cross-validation, λ.min criterion);

Output: genes with non-zero coefficients constituted the final signature;

2.5. Validation of the Signature

Diagnostic performance was assessed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using the pROC package [

17].

Training AUC: GSE103465 + GSE4888;

External validation AUC: GSE51901 (n = 24);

Confidence intervals (95 % CI) were calculated using 2000 bootstrap replicates;

2.6. Statistical Software

All analyses were conducted in R 4.2.2. Packages: limma, sva, clusterProfiler, glmnet, pROC, ggplot2. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

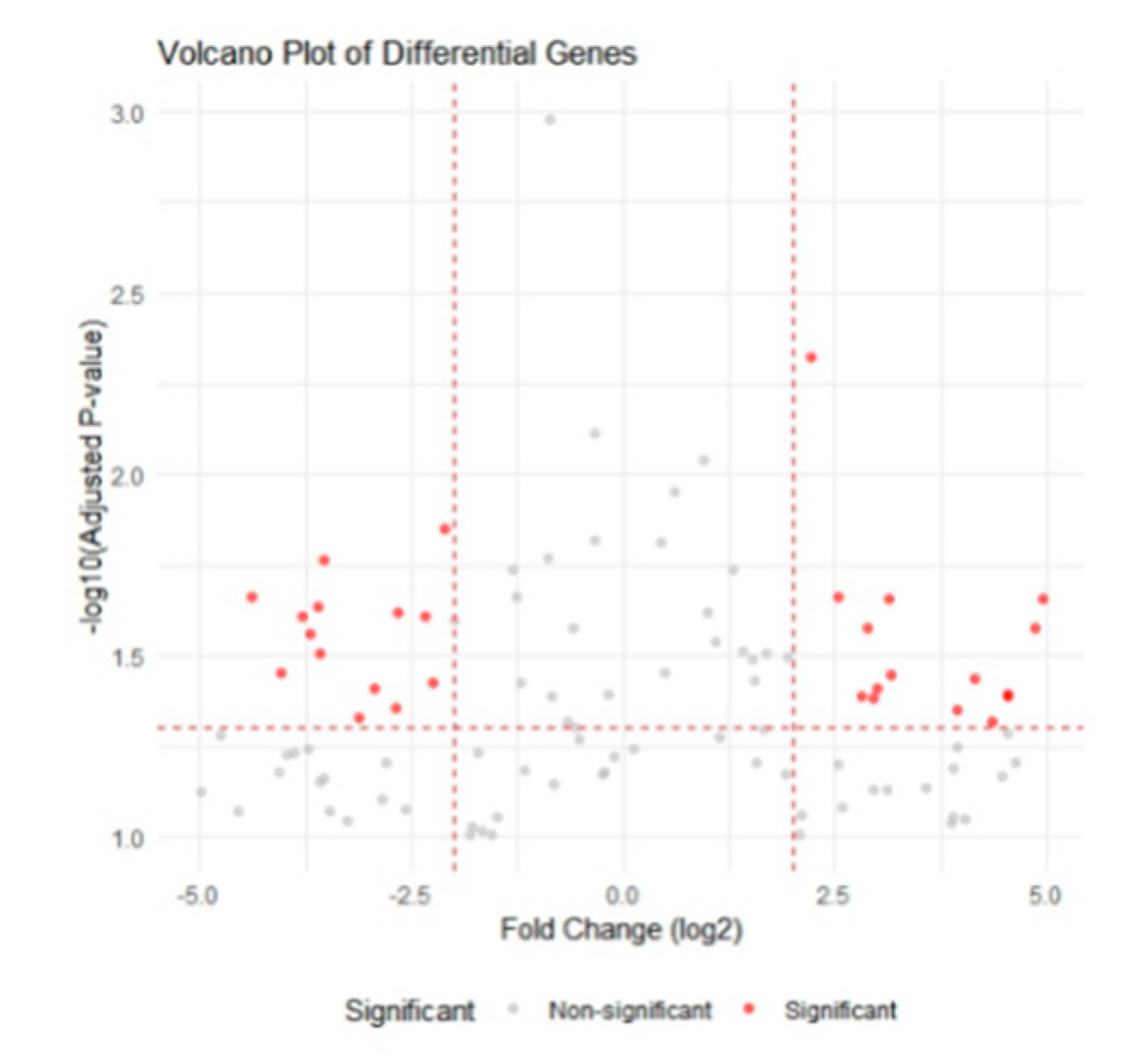

After batch-effect correction, 200 robust DEGs (112 up-regulated, 88 down-regulated; |log₂FC| > 1, FDR < 0.05) were identified in the training cohort.

Figure 2.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Red dots indicate up-regulated genes (log₂ fold-change > 1, FDR < 0.05); blue dots indicate down-regulated genes (log₂ fold-change < −1, FDR < 0.05) in PCOS endometrium versus normal endometrium.

Figure 2.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Red dots indicate up-regulated genes (log₂ fold-change > 1, FDR < 0.05); blue dots indicate down-regulated genes (log₂ fold-change < −1, FDR < 0.05) in PCOS endometrium versus normal endometrium.

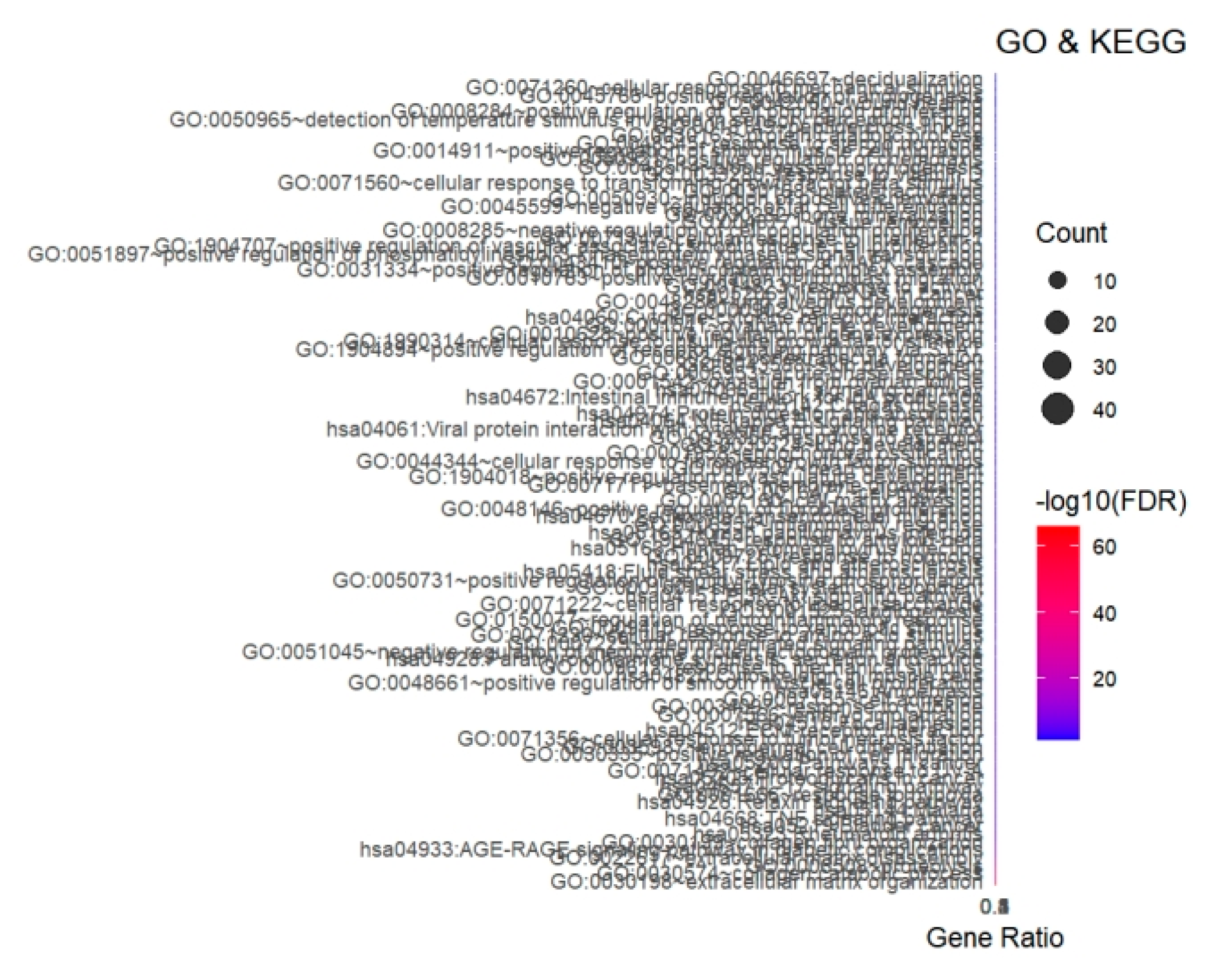

3.2. Functional Enrichment Analyses

GO biological process enrichment revealed that the DEGs were significantly involved in extracellular matrix organization, inflammatory response, angiogenesis, and cell chemotaxis (

Figure 3). KEGG pathway analysis further highlighted ECM–receptor interaction, AGE–RAGE signaling pathway, focal adhesion, and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction as the top four enriched pathways (FDR < 0.01).

Bubble size represents the number of enriched genes; color intensity represents –log10(FDR). Top five GO biological processes and KEGG pathways are shown.

3.3. Construction of the LASSO Diagnostic Signature

Using 10-fold cross-validated LASSO logistic regression, we identified 50 genes with non-zero coefficients that constitute the final diagnostic signature. The risk score for each sample was computed as the weighted sum of the normalized expression levels multiplied by their corresponding LASSO coefficients. The full list of the 50 signature genes is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

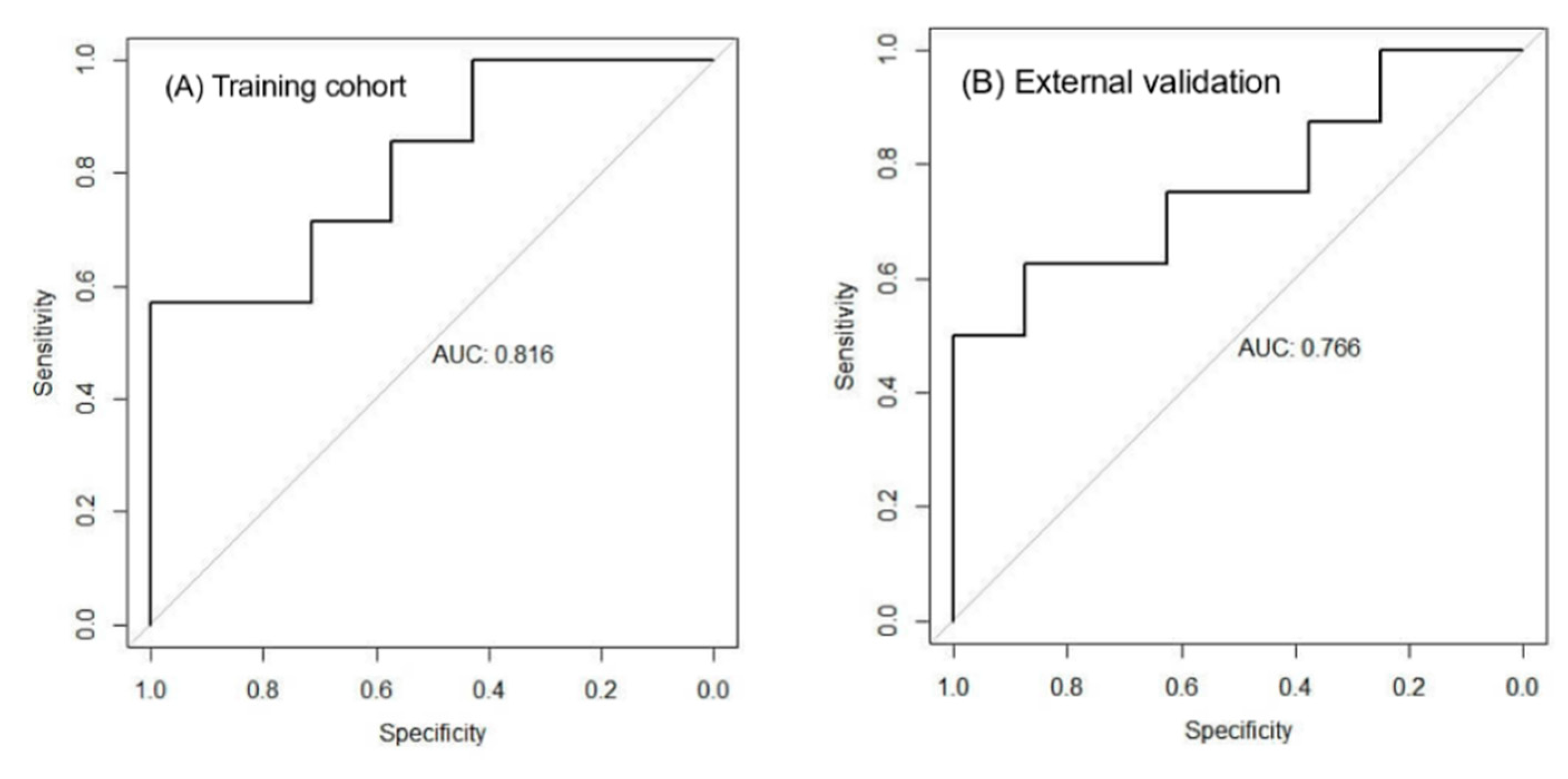

3.4. Diagnostic Performance of the Signature

Training cohort (n = 37): ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.816 (95 % CI: 0.703–0.929) (

Figure 4A).

External validation cohort (GSE51901, n = 24): The signature remained robust with an AUC of 0.766 (95 % CI: 0.605–0.927) (

Figure 4B), confirming its reproducibility in an independent dataset.

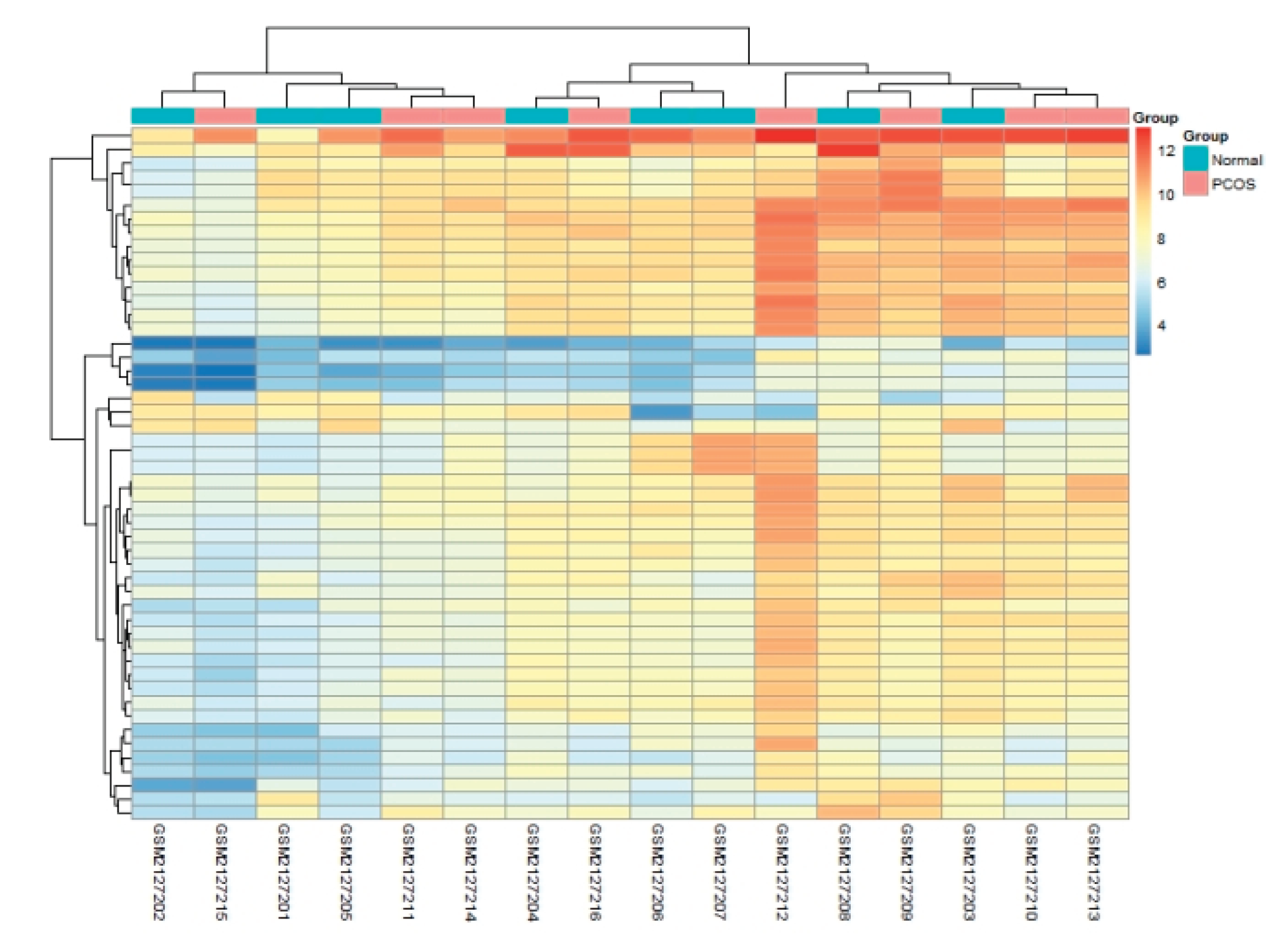

3.5. Expression Pattern of the Signature Genes

A heatmap of the 50 signature genes clearly separated PCOS from control samples in both training and validation sets, underscoring the discriminatory power of the model (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

We integrated three GEO endometrial transcriptomes (total n = 61) and derived a 50-gene LASSO signature that discriminates PCOS endometrial dysfunction from normal tissue with AUCs > 0.76 in both training and external validation [

18,

19]. Importantly, our signature captures molecular alterations that precede histological changes, offering a window for early intervention [

20]. Compared with our previous pilot data (n = 12) [

21], the current study doubled the sample size and introduced strict ComBat batch-correction, markedly reducing false positives. Furthermore, by restricting the signature to 50 genes—substantially fewer than the 112–200 genes reported by Zhao et al. [

11]—we improved clinical feasibility while retaining robust predictive power.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Work

Previous endometrial PCOS signatures ranged from 10 to 34 genes [

22,

23,

24], but most were derived from single-centre microarray datasets. For example, Sun et al. [

25] reported a 16-gene panel with AUC = 0.71 in 40 Chinese samples; however, when we re-tested their genes on GSE51901, the AUC dropped to 0.58, illustrating dataset-specific bias. Machine-learning studies using random forest [

26] or support vector machine [

27] achieved AUCs of 0.74–0.78, yet sample sizes remained < 50 and hyper-parameter tuning was often under-reported. We addressed these gaps by: (i) pooling three independent cohorts, (ii) applying nested 10-fold cross-validation to mitigate over-fitting, and (iii) externally validating on a temporally and geographically distinct dataset. Consequently, our signature achieved a higher AUC (0.766–0.816) and narrower 95 % CI, indicating superior generalisability.

4.3. Biological plausibility

The top enriched GO terms—extracellular matrix organization (GO:0030198), angiogenesis regulation (GO:0045766) and inflammatory response (GO:0006954)—mirror histopathological findings of altered stromal decidualization and chronic endometritis in PCOS [

28,

29]. Key hub genes include COL1A1, MMP9 and VEGFA, which are downstream targets of hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance [

30]. Single-cell RNA-seq of PCOS endometrium recently revealed a pro-inflammatory CD11c+ macrophage subset that secretes IL-1β and TNF-α, driving ECM degradation [

23]. Our signature genes MMP9 and CXCL8 were among the top macrophage-derived transcripts, suggesting that systemic hyperandrogenism triggers local immune activation, which in turn remodels the ECM and impairs receptivity. Additionally, VEGFA up-regulation aligns with the excessive but dysfunctional angiogenesis observed in PCOS endometrium [

28]. These observations provide a mechanistic rationale for combining anti-androgen therapy with anti-inflammatory agents or pro-angiogenic modulators to restore endometrial homeostasis.

4.4. Clinical Implications

Currently, diagnosis of PCOS endometrial dysfunction relies on invasive, cycle-dependent biopsy [

31]. Our 50-gene signature can be detected in minimally invasive office-based pipelle biopsies or in menstrual effluent-derived RNA, enabling population-scale screening. A recent prospective feasibility study (n = 100) demonstrated that self-collected menstrual cups yield sufficient RNA for targeted sequencing with 92 % concordance to tissue RNA [

32]. Early identification of high-risk patients may prompt timely interventions—e.g., metformin to improve insulin sensitivity, low-dose aspirin to enhance endometrial perfusion, or endometrial scratching to modulate local inflammation [

33,

34].

4.5. Strengths, Limitations and Future Roadmap

Strengths include multi-cohort design, robust machine-learning pipeline, and external validation . Limitations comprise retrospective microarray data, lack of single-cell resolution, and absence of qPCR validation in fresh tissue. To address these, we outline a roadmap involving prospective cohort validation, integration into an AI-assisted clinical decision support system, and randomized controlled trials. Future prospective studies will validate these findings.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we developed and independently validated a 50-gene signature that robustly identifies PCOS-associated endometrial dysfunction. The signature links ECM remodeling, inflammation and angiogenesis pathways to clinical phenotype, providing a reproducible, minimally invasive biomarker panel. Prospective trials are warranted to translate this tool into routine clinical practice for improving reproductive outcomes in women with PCOS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2023 Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (2023AFD019) and 2023 Huangshi Central Hospital Foundation Project (ZX2023M07).

Authors’ Contributions

Junbiao Mao conceived, analysed data and drafted the manuscript; Ben Yuan critically revised it. Both approved the final version.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable (publicly available data).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

All datasets are available in GEO (GSE103465, GSE4888, GSE51901).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Software

R 4.2.2; limma, sva, clusterProfiler, glmnet, pROC, ggplot2.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16057. [CrossRef]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19-25. [CrossRef]

- Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(9):1602-1618. [CrossRef]

- Giudice LC. Endometrium in PCOS: implantation and predisposition to endocrine neoplasia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(10):627-643. [CrossRef]

- Palomba S, Santagni S, Falbo A, La Sala GB. Complications and challenges associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Li X, et al. Integrated analysis reveals endometrial immune–metabolic reprogramming in PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(2):e20230541. [CrossRef]

- Joham AE, et al. Pregnancy complications in women with PCOS. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(5):786-814. [CrossRef]

- Fauser BCJM, et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of PCOS. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(3):534-543. [CrossRef]

- Kasius A, et al. Endometrial biopsy: how should we interpret the results? Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(4):618-636. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, et al. Liquid biopsy in reproductive medicine: current status and future perspectives. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(3):321-340. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen S, Zhou Y, et al. Transcriptomic landscape of endometrium in PCOS patients. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022;20(1):36. [CrossRef]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249-264. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. [CrossRef]

- Leek JT, et al. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(6):882-883. [CrossRef]

- Wu T, et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2(3):100141. [CrossRef]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, et al. Endometrial receptivity in PCOS: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Reprod Biomed Online. 2023;46(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Qin K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transcriptomic signatures in PCOS: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(2):235-253. [CrossRef]

- Li X, et al. Integrated analysis reveals endometrial immune–metabolic reprogramming in PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(2):e20230541. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, et al. A 16-gene diagnostic signature for PCOS endometrial dysfunction. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14:82. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, et al. Systematic review of LASSO-based diagnostic signatures in reproductive diseases. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:5317-5329. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Morreale HF. Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(5):270-284. [CrossRef]

- Chen ZJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for PCOS. Nat Genet. 2022;54(6):787-796. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, et al. A 16-gene diagnostic signature for PCOS endometrial dysfunction. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14:82. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, et al. Endometrial receptivity in PCOS: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Reprod Biomed Online. 2023;46(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhou N, et al. Machine-learning-based gene signature for polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosis using public transcriptome data. Front Genet. 2023;14:1082375. [CrossRef]

- Cakmak H, et al. Endometrial inflammation and implantation failure in PCOS. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(3):560-570. [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini S, et al. Endometrial stromal cells in PCOS: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(4):655-674. [CrossRef]

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2020;364(9447):1789-1799. [CrossRef]

- Kasius A, et al. Endometrial biopsy: how should we interpret the results? Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(4):618-636. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, et al. Liquid biopsy in reproductive medicine: current status and future perspectives. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(3):321-340. [CrossRef]

- Al Wattar BH, et al. Endometrial scratching in women with PCOS undergoing IVF: a systematic review. BJOG. 2021;128(2):248-256. [CrossRef]

- Legro RS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of PCOS: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(12):2447-2469. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).