1. Introduction

Tenacibaculum spp. is the etiological agent of Tenacibaculosis an ulcerative skin disease that affects so many fish species in the world, this pathogen produces clinical symptoms that acutely progress and trigger death (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2020), (Krkosek et al. 2024). Its clinical signs are observable after transfer to seawater, highlighting the presence of macroscopic lesions such as ulcers and necrosis on the surface of the body, eroded mouth, frayed fins, and rotted tail, we can observe necrosis on the gill, in eyes we can find choroidal congestion and sub-choroidal hemorrhage, sometimes with eye rupture (Ostland, Morrison, y Ferguson 1999a) and (Irgang y Avendaño-Herrera 2021), (Avendaño-Herrera, Lopez, et al. 2024). The genera belonging to the Flavobacteriaceae family, these bacteria are as strict aerobic bacilli with negative Gram stain, with motility, and can be grown in marine agars. This pathogen family is able to grow in four different kinds of agar medium, including Marine Shieh's Selective Medium (Kumanan et al. 2022) and Flexibacter maritimus medium (Pazos et al. 1996). Their growth temperature varies depending on the species, with optimal temperatures for T. discolor and T. gallaicum between 14-38°C and for T. finnmarkense from 2°C to 20°C (Fernández-Álvarez y Santos 2018).

In Tenacibaculum genus, at this moment describes species associated with fish include T. bernardetii, recently proposed by Avendaño-Herrera, Saldarriaga-Córdoba, y Irgang 2023, T. dicentrarchi, T. discolor, T. finnmarkense (Småge, Brevik, et al. 2016) , T. maritimum, T. soleae, T. ovolyticum and T. piscium (Michnik et al. 2024), (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2022), which has been isolated from wild, cultured anadromous, and marine fish species, such as salmonid species (A. B. Olsen et al. 2017), (Valdes et al. 2021), Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2004), red conger eel (Genypterus chilensis) (Saldarriaga-Córdoba, Irgang, y Avendaño-Herrera 2021), Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) and shark (Carcharias taurus) (Florio et al. 2016). This bacterium (Tenacibaculum spp) has a wide geographical distribution: Europe (Småge, Frisch, et al. 2016) and (Bernardet, Kerouault, y Michel 1994), Asia (Baxa 1988), Oceania (Wilson, Douglas, y Dunn 2019a), and North and South America (Ostland, Morrison, y Ferguson 1999b). Specifically, in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), tenacibaculosis has been reported under various names and associated with different species in several countries, including the United States (Frelier et al. 1994), Australia (Handlinger, Soltani, y Percival 1997) , Canada (Ostland, Morrison, y Ferguson 1999c), Norway (A. Olsen et al. 2011), and Chile (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2016a). In Chile according to the records of the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service (Sernapesca), the morbi-mortality of tenacibaculosis in salmonids in Chile is mainly caused by T. dicentrarchi and T. maritimum (Wakabayashi, Hikida, y Masumura 1986), it has been secondary annual mortalities during 2019, 2020, and 2021 corresponded to 14, 25, and 31% for the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) species according with the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service of Chile( Sernapesca).

Genomic characterization has been established in various countries. Analysis of the 16S ribosomal RNA shows different genogroups, which may present varying degrees of virulence, leading to high mortality or affecting specific species.

The establishment of an infectious disease is triggered by: i) environmental changes, which increase the likelihood of the establishment of new pathogens (Wade et al. 2019) ii) high levels of overcrowding in farming systems, which produce high levels of stress, making fish more susceptible to pathogen outbreaks and iii) aquaculture massification (Manley et al. 2014) and (Ellis et al. 2002), but what factors of Tenacibaculum allow its success? Some studies evidence endemic colonization of aquaculture systems and parallel evolution of fish pathogenicity (Habib et al. 2014), (Bellec et al. 2024), (Coca et al. 2023); however, there are many uncertainties about the specific virulence factors present in this bacterium. To address this, we have examined four strains of T. dicentrarchi isolated from Atlantic salmon (S. salar) to identify virulence genes. Specifically, we are investigating mechanisms of iron acquisition, regulation of copper levels, resistance to tetracycline and fluoroquinolones, as well as pathogenicity IG (Avendaño-Herrera, Echeverría-Bugueño, et al. 2024), (Saldarriaga-Córdoba, Irgang, y Avendaño-Herrera 2021). Despite the valuable insights gained, significant gaps remain regarding the differences in virulence genes and antibiotic resistance mechanisms among various isolates. To address this, we analyzed the genomes of two Tenacibaculum dicentrarchi isolates from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), focusing on identifying the primary virulence and antibiotic resistance factors. This analysis provides a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying virulence and antimicrobial resistance in T. dicentrarchi.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Gross Pathology

The collected fish presented morbidity and mortalities, evidencing severe body injuries like the clinical signs caused by T. dicentrarchi. In the case of Atlantic salmon, all were confirmed as positive for T. dicentrarchi by isolation and qPCR. A total of 2 tenacibaculosis samples were obtained for the current study. These isolates were collected as part of two ongoing Chilean surveillance programs. The first sample was derived from the General Sanitary Mortality Management Program (PSGM), which involves companies and private laboratories conducting passive surveillance of diseases based on sanitary and productive criteria. Fish displaying at least one of the specified symptoms were chosen for sampling. The provided records thoroughly detailed the observed clinical signs, including fin erosion and ulceration, lesions in the buccal, opercular, and rostral areas, as well as occurrences of branchial necrosis and yellow pigmentation.

2.2. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

To isolate bacteria, we collected samples from both the external tissues and internal organs (such as the kidney, and liver) of each fish. These samples were then streaked onto plates containing Flexibacter maritimus medium (Pazos et al., 1996). The plates were subsequently incubated at 18 ºC for 7 days.

2.3. Histopathology

Tissue specimens intended for histological examination were preserved in 10% buffered formalin. Subsequently, standard procedures were employed for their processing, and sections measuring 3–4 µm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), following the methodology outlined by Prophet et al. (1992), to elucidate microscopic morphological alterations.

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing and Library Construction

The culture of Tenacibaculum strains was isolated from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in a marine agar medium at a temperature of 18 °C. Gram staining was performed, obtaining Gram-negative filamentous bacteria. DNA extraction was performed using the TANBead Nucleic Acid Extraction kit (M61GS46) by mechanical extraction using the Automatic Nucleic Acid Extraction robot MaelstromTMMaelstromTM4800. Two colonies of the cultured strains were placed on the marine agar in sterile PBS. Colonies were vortexed for 30 seconds. They are centrifuged for 5 minutes at 13,000 rpm. Once the pellet is obtained, 200 µl of incubation buffer and 10 µl of proteinase K are added and incubated at 56 °C for 60 minutes. The lysate is transferred to the 1/7 column. We are obtaining 120 µl of extraction. We measured DNA concentration using 2 µl of samples through the Invitrogen Qubit dsDNA BR Assay kit (Invitrogen Qubit 4 Fluorometer). Following the Nextera XT DNA Library Prep® protocol, isolated DNA sequencing was used for whole genome sequencing.

The library amplification was performed using the Nextera XT DNA Library Prep kit under the following conditions: 72 °C for 3 minutes, 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 12 cycles of 95 °C for 10 seconds; 55 °C for 30 seconds and 72 °C for 5 minutes. After that, a final elongation step was performed at 72 °C for 5 minutes. Next, all samples were indexed using IDT for Illumina Nextera UD Indexes Set B and cleaned up. Samples were sequenced using the Illumina Miniseq platform, following the manufacturer's protocols (Illumina DNA prep kit and Nextera Library XT DNA preparation kit).

2.5. Quality Control and Genome Assembly

Quality control of raw reads was assessed with FastQC (De Sena Brandine y Smith 2021) and summarized with MultiQC (Ewels et al. 2016). Trimming of reads was performed with Trimmomatic (Bolger, Lohse, y Usadel 2014), de novo genome assembly was accomplished with SPAdes (Bankevich et al. 2012) and assessed with QUAST (Gurevich et al. 2013).

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

Tenacibaculum dicentrarchi and Tenacibaculum finnmarkense genomes were retrieved from NCBI. SNPs were extracted from genomes sequenced in this study and from genomes obtained from NCBI, and a SNP multiple sequence alignment was constructed with PhaME (Shakya et al. 2020). A phylogenetic tree was built under maximum likelihood from 146,782 SNP positions in the core genome with RAxML (Stamatakis 2014). Whole-genome Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) was computed between all pairs of genomes with FastANI (Hernández-Salmerón y Moreno-Hagelsieb 2022).

2.7. Virulence and Resistance Factors Analysis

Genomes assembled in this study and genomes retrieved from NCBI were annotated with Prokka (Seemann 2014). Virulence factors (VF) were identified by performing local alignments with Protein BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) , were query sequences corresponded to translated CDS sequences obtained from Prokka, and the VFDB protein sequences of full dataset (Liu et al. 2019) were used as database. Similarly, antibiotic resistance (AR) genes were found as above but using the CARD (McArthur et al. 2013) database. In both cases, blastp hits with at least 0.0001 e-value, 50% of similarity, and 60% query coverage were considered for downstream analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Sign and Bacterial Isolation

Examination of smears obtained from skin lesions disclosed a plentiful presence of rod-shaped, elongated Gram-negative bacteria. At the tissue level, filamentous structures with a multifocal distribution were identified on the muscle surface, and these were determined to be consistent with bacteria belonging to the genus Tenacibaculum sp. (Figure 1).

All fish mainly presented external macroscopic lesions (e.g. skin lesions, tail rot, and hemorrhagic mouth) in different body parts, but mainly erosion and loss of upper and lower mandibular tissue, with high yellow pigmentation, were observed. (Figure 2). being the typical lesions of tenacibaculosis.

3.2. Pan-Genome Characterization

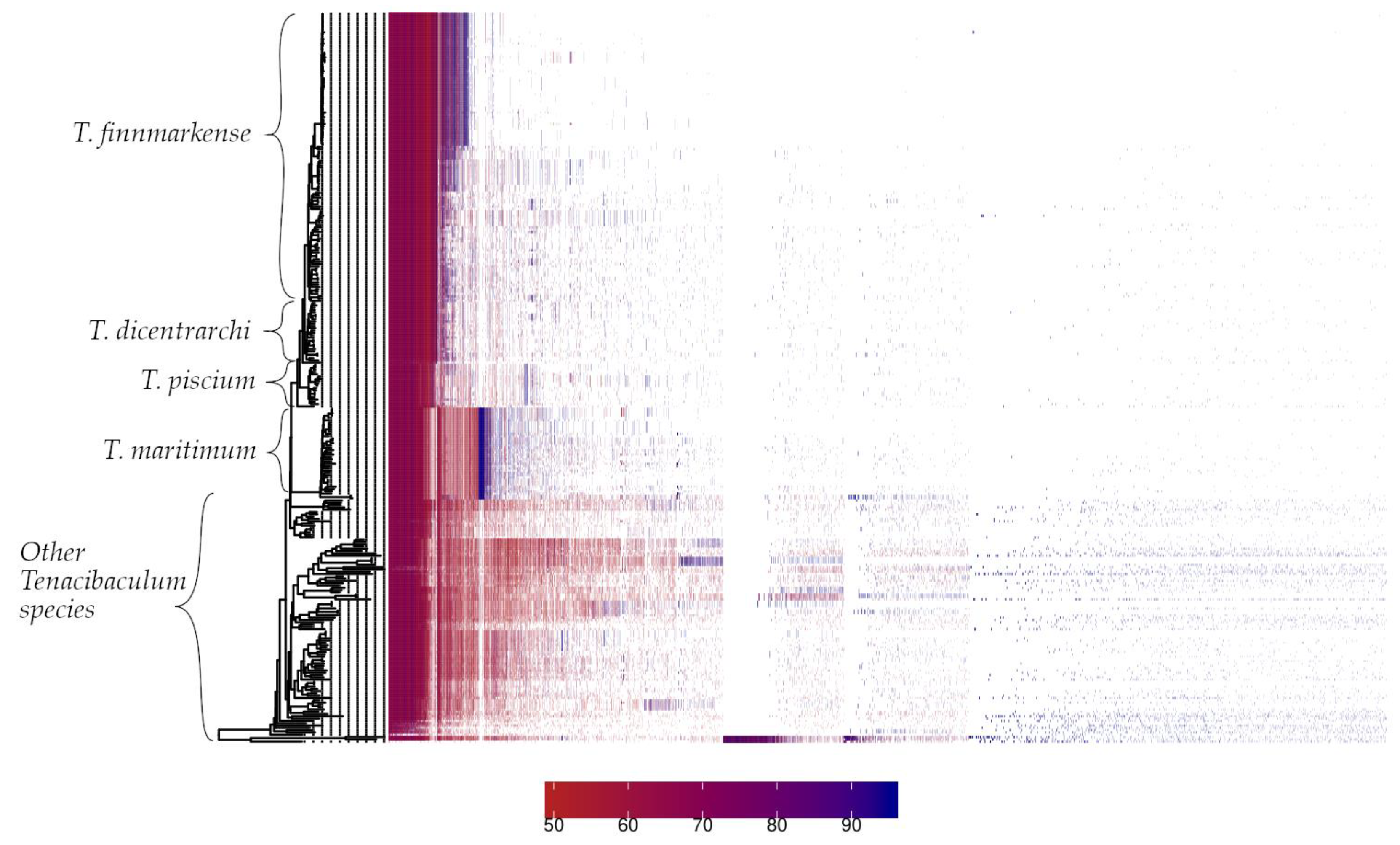

The PIRATE toolbox was applied to 318

Tenacibaculum genomes, from which 4 strains are reported in this study and 314 were retrieved from NCBI [Sayers et al., 2022]. The pangenome of the

Tenacibaculum genus comprised 41079 gene families, of which 1243 (3.03%) were classified as core (>95% genomes) and 39836 (96.97%) as accessory. The analysis of the present/absent gene families showed remarkably distinct patterns through the

Tenacibaculum genus, especially between salmonid and non-salmonid affecting

Tenacibaculum species (

Figure 3).

3.3. Phylogenomics

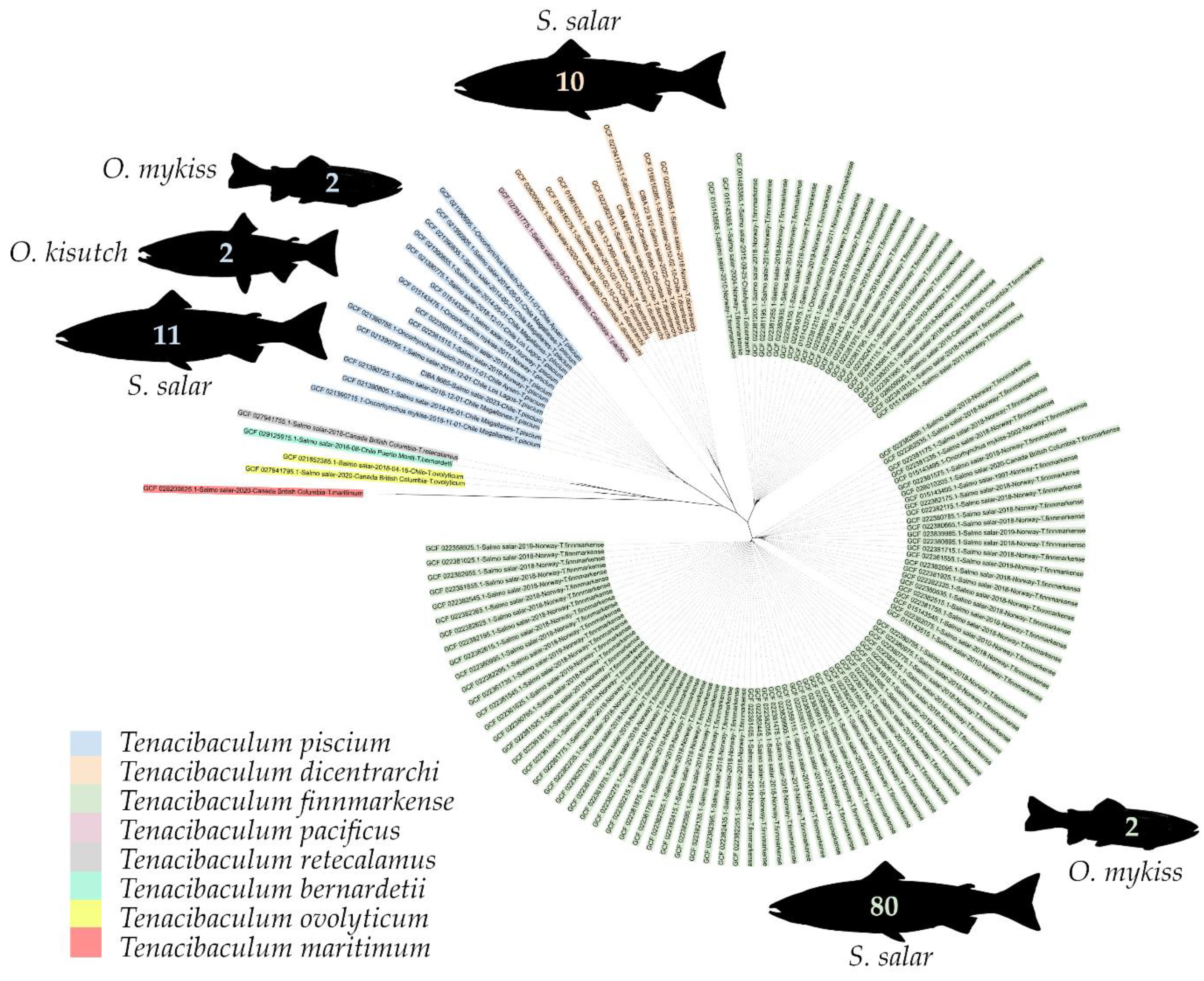

The analysis focused on 138 genomes of salmonid-affected species. A maximum likelihood dendrogram was generated to show the grouping of these species (refer to

Figure 4). In the case of

T. finnmarkense, strains affecting salmonids grouped into two clusters, one of which further divided into two subclusters (highlighted in green). Out of 82

T. finnmarkense isolates, 80 were from

S. salar, and 2 were from

O. mykiss. Meanwhile, strains of

T. piscium affecting salmonids grouped into a single cluster. Out of the 15

T. piscium isolates, 11 were from

S. salar, 2 from

O. kisutch, and two from

O. mykiss. Notably, all other

Tenacibaculum genomes affecting salmonids, including

T. dicentrarchi, were isolated from

S. salar exclusively.

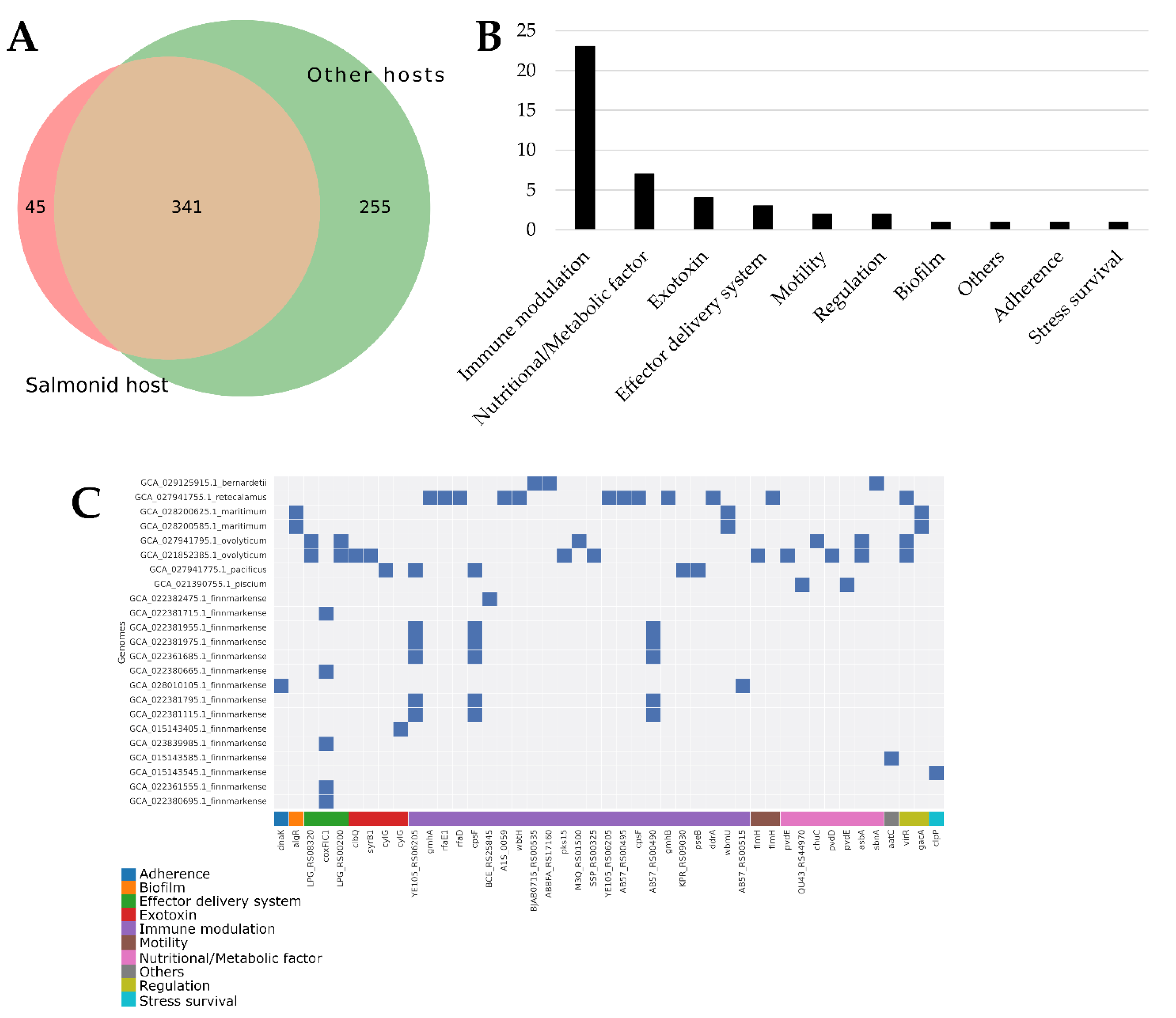

3.4. Virulence Factors

Virulence factors (VFs) were identified through pangenome analysis of gene families. A total of 641 VFs were found in

Tenacibaculum genomes associated with hosts. Out of these, 45 were exclusively present in isolates affecting salmonid fish (see

Figure 5A). Interestingly, most of these VFs specifically affecting salmonid fish are linked to immune modulation (see

Figure 5B). Moreover, each

Tenacibaculum species affecting salmonid fish exhibits a unique set of immune modulation VFs, with

T. retecalamus containing the highest number of such VFs (see

Figure 5C). The list of these 45 VFs only found in salmonid-affecting isolates, along with their similarity percentages, is available in

Supplementary Table S1.

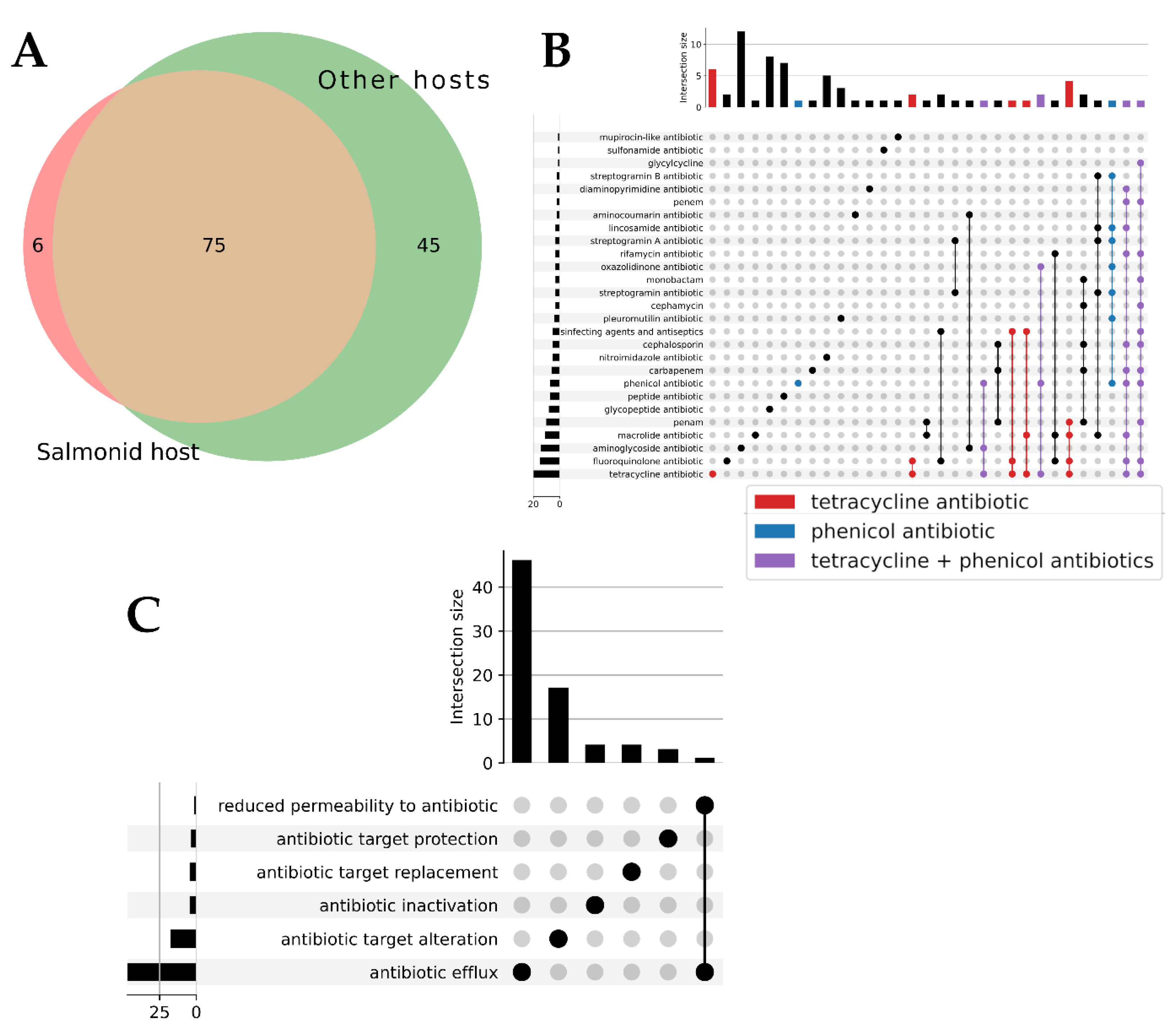

3.5. Antibiotic Resistance Factors

The pangenome analysis identified gene families containing Antibiotic Resistance factors (ARs). 126 ARs were found in the

Tenacibaculum genomes associated with hosts. Among these, 81 ARs were present in isolates affecting salmonids, and 6 of these were unique to salmonid-affecting isolates (see

Figure 6A). The 81 ARs found in salmonid-affecting isolates included factors related to tetracycline, phenicol, and other drug families (see

Figure 6B). Antibiotic efflux is the most identified mechanism among these factors (see

Figure 6C). More details about the 6 and 75 ARs present in salmonid-affecting isolates and their similarity percentages can be found in

Supplementary Tables S2a and S2b.

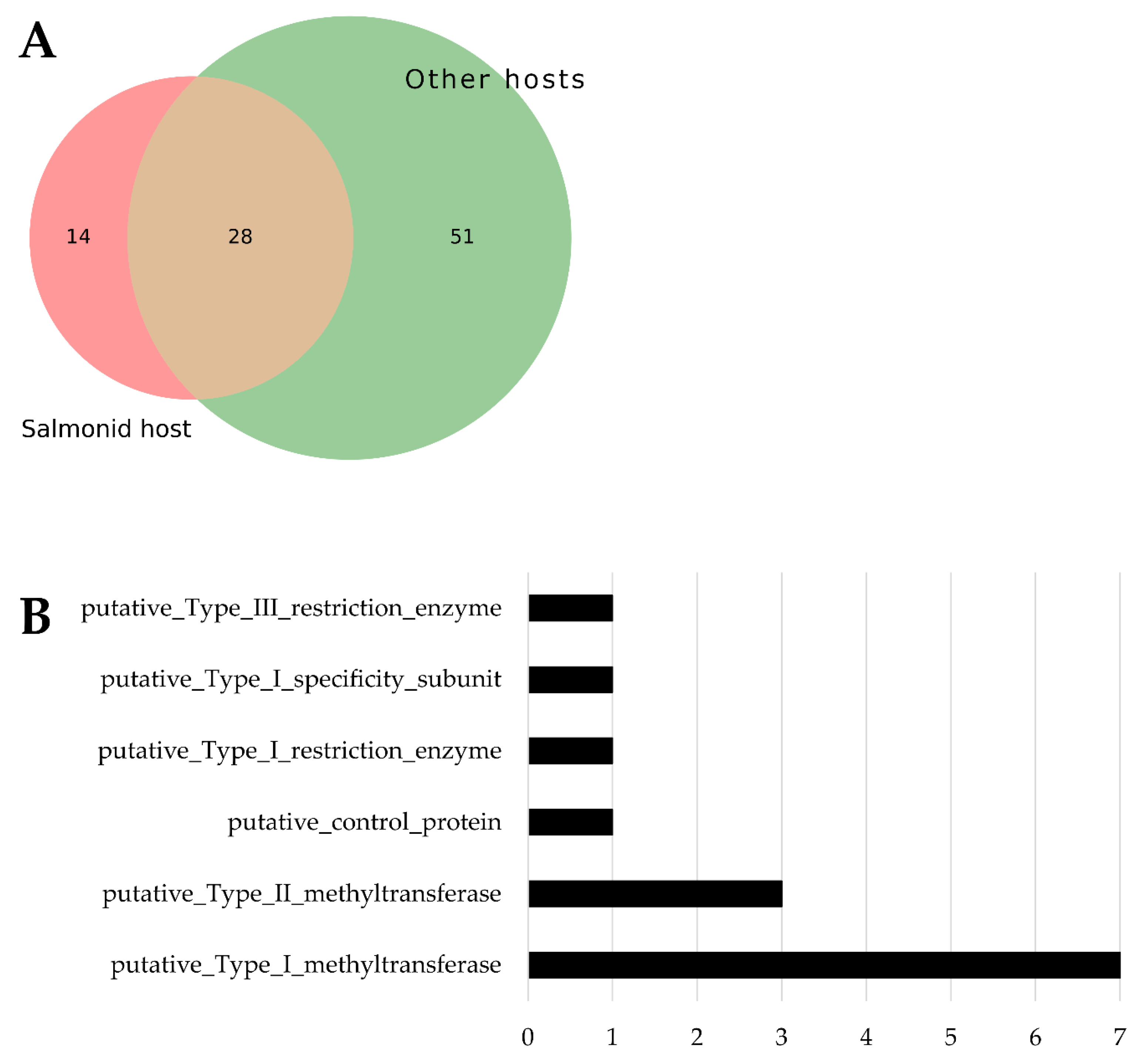

3.6. Restriction-Modification System Abundance

Predicted Restriction-Modification System coding sequences (RMs) were identified through pangenome analysis of gene families. A total of 93 RMs were found in

Tenacibaculum genomes associated with hosts. Among these, 14 were exclusive to isolates affecting salmonids (see

Figure 7A). Notably, type I methyltransferase is the most prevalent RM found only in salmonid-associated isolates (see

Figure 7B). The list of these 14 RMs exclusive to salmonid-affecting isolates is available in

Supplementary Table S3.

4. Discussion

Within the Tenacibaculum genus, several important fish-pathogenic species exist, including T. maritimum, T. dicetrarchi, and T. finnmarkense. In Chile, T. dicetrarchi shows a sustained increase in overall mortality due to cases of infectious tenacibaculosis, particularly in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (SERNAPESCA, 2018; SERNAPESCA, 2021 (January-November) (Nowlan, Lumsden, y Russell 2021).

This bacterium was initially identified in Spanish sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) with damaged skin (Piñeiro-Vidal et al. 2012). Subsequently, Tenacibaculum dicetrarchi has been identified as the causative agent of disease outbreaks in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and red conger (Genypterus chilensis) in Chile (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2016b) and (Irgang y Avendaño-Herrera 2022a). Additionally, cases have been reported in Atlantic salmon (S. salar) in Norway (Klakegg et al. 2019) and (Olsen et al. 2017) and Tasmania (Wilson, Douglas, y Dunn 2019b). Norway and Scotland have also documented occurrences of this bacterium in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and largemouth bass (Cyclopterus lumpus) (Olsen et al., 2017), as well as ballan fish (Papadopoulou et al. 2021). Despite the significant impact of T. dicetrarchi induced tenacibaculosis on Chilean aquaculture, there is limited knowledge about the bacterium's pathogenesis, infection pathways, and antibiotic resistance mechanisms.

Adherence of bacterial cells to fish tissue surfaces is crucial during the initial stages of Tenacibaculosis infection. Microscopic examinations of smears from ulcerative skin lesions commonly reveal abundant long rods and Gram-negative bacteria consistent with descriptions of Tenacibaculum cells (Figure 1). This bacterium induces severe external macroscopic skin lesions and necrosis, affecting various body surface areas, occasionally accompanied by bone exposure (Mabrok et al. 2023), (Echeverría-Bugueño et al. 2023), primarily in the maxillofacial and cranial regions, as depicted in Figure 2. Other external manifestations of the disease include reddening and erosion of the skin beneath the jaw, hemorrhagic mouth and operculum, and yellowish discoloration in the oral and dental areas (Ostland, Morrison, y Ferguson 1999) and (Irgang y Avendaño-Herrera 2021), (Avendaño-Herrera et al. 2023).

The phylogenetic and pangenomic analysis, derived from SNP sequences, reveals three distinct clusters in the phylogenetic tree. Notably, each of our three analyzed genomes is positioned within a separate cluster (

Figure 3).

In our analysis, we have identified both core genes and accessory genes, allowing us to determine the number of homologous gene families in the sequences we studied. When we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of

T. dicetrarchi sequences, we observed three distinct clusters (see

Figure 3). Each of the isolates we sequenced belongs to a unique cluster. Upon examining virulence factor-expressing genes, we primarily found the presence of type III, IV, and V secretion systems. Among the isolates we scrutinized, only one exhibited a type II secretion system.

Notably, the Type III Secretion System (T3SS) emerges as significant, which potentially could be used as a mechanism for bacteria to release effector proteins into host cells, thereby enhancing virulence and colonization. This system has been reported as a pathogenicity mechanism (Notti y Stebbins 2016) for certain bacteria groups such as Yersinia and Shigella.

Among the identified genes is the pore-forming toxin (PFT) system, prevalent in the majority of analyzed sequences, except for one (Td_CIBA_08_2022). The absence of PFT in this sequence suggests a potential variance in cell invasion mechanisms. Genes responsible for encoding virulence factors were identified and categorized into subgroups, particularly associated with type II, III, IV, and V secretion systems, ionophore pore-forming toxins, genotoxins, cell invasion genes, antiphagocytic genes, and biofilm formation, as well as stress survival.

The goal of this comparative analysis is to offer insights into the genes and pathways that may be involved in the virulence mechanisms of T. dicetrarchi. The identified genes, either in whole or in part, could play a role in the organism's ability to cause disease in fish. To gain a more thorough understanding, further research is necessary into the physiological aspects and infectivity of these predicted genes.

Between late July 2018 and mid-August 2020, there were outbreaks of tenacibaculosis in marine aquaculture cycles, with a 52.5% prevalence rate (520 out of 990 cycles) (SERNAPESCA, 2020). Currently, there is no vaccine for this pathogen, requiring the use of antimicrobial compounds prescribed by veterinarians to manage and control the disease. In 2019, 6.2 tons of florfenicol (FFC) and 3.1 tons of oxytetracycline (OTC) were administered for tenacibaculosis control, accounting for 2% and 1%, respectively, of the total 311.2 tons of antimicrobials used in marine farms that year (SERNAPESCA, 2019b, 2020).

Our analysis identified several antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), raising concerns, particularly about those associated with Florfenicol and Tetracyclines, the most widely used antibiotics in Chilean aquaculture (REF). Among the sequences analyzed, the tetracycline resistance genes tetA and tetB were found, with two isolates also exhibiting the tet(Q) gene. Additionally, resistance genes corresponding to commonly used antibiotics—such as sul4 for sulfonamides and cat86 for phenicols—were detected, including enrofloxacin, florfenicol, trimethoprim, and sulfadiazine (Nowlan et al., 2020; Rigos et al., 2020; Saldarriaga-Córdoba et al., 2021). In the absence of a commercial vaccine, antibiotic treatment remains the primary method to combat Tenacibaculum sp. in aquaculture, particularly since juvenile fish are occasionally exposed to tenacibaculosis in hatchery environments (Irgang y Avendaño-Herrera 2022b).

Bacteria use restriction and modification (R-M) systems as a defense mechanism to restrict the entry, integration, and replication of foreign genetic elements. These systems act like the innate immune system of bacteria, defending against foreign DNA (Oliveira, Touchon, y Rocha 2014). In addition to their role in defense, R-M systems can also limit sequences generated by genomic damage and process free DNA ends, influencing the fate of DNA acquired by the cell and maintaining the genetic boundaries of bacterial species (Rocha 2001). Although R-M system proteins are widely used in molecular biology, biotechnology, and biomedicine to modify DNA, their ecological aspects, including occurrence, distribution, diversification, and impact on microbial evolution through horizontal gene transfer of mobile genetic elements, are not fully understood.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of Tenacibaculum strains reveals significant genetic specialization in those affecting salmonid fish. These strains exhibit distinct gene profiles, including unique virulence factors primarily linked to immune modulation, with T. retecalamus showing the highest number. Additionally, they possess specialized antibiotic resistance genes, particularly against tetracycline and phenicol, suggesting an adaptation to survive treatments common in salmonid aquaculture.

Furthermore, these strains have abundant restriction-modification systems, especially type I methyltransferases, which may help them evade the host immune response or adapt to specific environmental conditions associated with salmonids. Overall, the genetic distinctions in these strains underscore their specialized evolution for infecting salmonid hosts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.P.,M.G. ; methodology and study design, M.G., J.P.P., D.C, M.M and Y.C.; sampling, D.C. , bioinformatic analysis, M.M.; interpretation, Y.C., B.S., M.G. J.P.P and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. J.P.P and M.M and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, M.G., J.P.P. and Y.C.; supervision, J.P.P. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Aplicadas, grant number: clinical_genomic_Bacteria_200 and Fondecyt de Iniciación Nº 11230401 (J.P.P).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data from this study is available at NCBI. The Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Aplicadas (CIBA) in Puerto Montt, Chile, holds certification for aquaculture diagnostic services. The Chilean National Fish and Aquaculture Service (Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura de Chile,

http://www.sernapesca.cl/, accessed on 10 November 2022) approved all associated experimental protocols. Our procedures were conducted in accordance with Chile’s Ley 20.380 on animal protection, which governs animal welfare in biomedical research, and they closely followed the guidelines set out in the EU Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals in scientific research.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to our colleagues in the Chilean salmon industry for permitting the collection of samples for this study. We deeply appreciate the technician and veterinary teams at the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Aplicadas (CIBA) for their invaluable support. Furthermore, we give our thanks to the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID) for funding J.P.P, Fondecyt de Iniciación Nº 11230401.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Altschul, Stephen F., Warren Gish, Webb Miller, Eugene W. Myers, y David J. Lipman. 1990. «Basic Local Alignment Search Tool». Journal of Molecular Biology 215 (3): 403-10. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, R., R. Irgang, C. Sandoval, P. Moreno-Lira, A. Houel, E. Duchaud, M. Poblete-Morales, P. Nicolas, y P. Ilardi. 2016a. «Isolation, Characterization and Virulence Potential of Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi in Salmonid Cultures in Chile». Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 63 (2): 121-26. [CrossRef]

- 2016b. «Isolation, Characterization and Virulence Potential of Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi in Salmonid Cultures in Chile». Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 63 (2): 121-26. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, R, B Magariños, S López-Romalde, Jl Romalde, y Ae Toranzo. 2004. «Phenotypic Characterization and Description of Two Major O-Serotypes in Tenacibaculum Maritimum Strains from Marine Fishes». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 58:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Constanza Collarte, Mónica Saldarriaga-Córdoba, y Rute Irgang. 2020. «New Salmonid Hosts for Tenacibaculum Species: Expansion of Tenacibaculosis in Chilean Aquaculture». Journal of Fish Diseases 43 (9): 1077-85. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Macarena Echeverría-Bugueño, Mauricio Hernández, Pablo Saldivia, y Rute Irgang. 2024. «Proteomic Characterization of Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi under Iron Limitation Reveals an Upregulation of Proteins Related to Iron Oxidation and Reduction Metabolism, Iron Uptake Systems and Gliding Motility». Journal of Fish Diseases 47 (9): e13984. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Pierre Lopez, Macarena Echeverría-Bugueño, Henry Araya-León, y Rute Irgang. 2024. «Characterization of Tenacibaculum Maritimum Isolated from Diseased Salmonids Farmed in Chile Reveals High Serological and Genetic Heterogeneity». Journal of Fish Diseases 47 (9): e13965. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Anne Berit Olsen, Mónica Saldarriaga-Cordoba, Duncan J. Colquhoun, Víctor Reyes, Javier Rivera-Bohle, Eric Duchaud, y Rute Irgang. 2022. «Isolation, Identification, Virulence Potential and Genomic Features of Tenacibaculum Piscium Isolates Recovered from Chilean Salmonids». Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 69 (5). [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Mónica Saldarriaga-Córdoba, Macarena Echeverría-Bugueño, y Rute Irgang. 2023. «In Vitro Phenotypic Evidence for the Utilization of Iron from Different Sources and Siderophores Production in the Fish Pathogen Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi». Journal of Fish Diseases 46 (9): 1001-12. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Herrera, Ruben, Mónica Saldarriaga-Córdoba, y Rute Irgang. 2023. «Tenacibaculum Bernardetii Sp. Nov., Isolated from Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar L.) Cultured in Chile». International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 73 (10). [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, Anton, Sergey Nurk, Dmitry Antipov, Alexey A. Gurevich, Mikhail Dvorkin, Alexander S. Kulikov, Valery M. Lesin, et al. 2012. «SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing». Journal of Computational Biology 19 (5): 455-77. [CrossRef]

- Baxa, Dolores. 1988. «In vitro and in vivo activities of Flexibacter maritimus toxins». In vitro and in vivo activities of Flexibacter maritimus toxins, enero.

- Bellec, Laure, Thomas Milinkovitch, Emmanuel Dubillot, Éric Pante, Damien Tran, y Christel Lefrancois. 2024. «Fish Gut and Skin Microbiota Dysbiosis Induced by Exposure to Commercial Sunscreen Formulations». Aquatic Toxicology 266 (enero):106799. [CrossRef]

- Bernardet, J.-F. Kerouault, y C. Michel. 1994. «Comparative Study on Flexibacter maritimus Strains Isolated from Farmed Sea Bass(Dicentrarchus labrax) in France.» Fish Pathology 29 (2): 105-11. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, Anthony M., Marc Lohse, y Bjoern Usadel. 2014. «Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data». Bioinformatics 30 (15): 2114-20. [CrossRef]

- Coca, Yoandy, Marcos Godoy, Juan Pablo Pontigo, Diego Caro, Vinicius Maracaja-Coutinho, Raúl Arias-Carrasco, Leonardo Rodríguez-Córdova, Marco Montes De Oca, César Sáez-Navarrete, y Ian Burbulis. 2023. «Bacterial Networks in Atlantic Salmon with Piscirickettsiosis». Scientific Reports 13 (1): 17321. [CrossRef]

- De Sena Brandine, Guilherme, y Andrew D. Smith. 2021. «Falco: High-Speed FastQC Emulation for Quality Control of Sequencing Data». F1000Research 8 (enero):1874. [CrossRef]

- Echeverría-Bugueño, Macarena, Rute Irgang, Jorge Mancilla-Schulz, y Ruben Avendaño-Herrera. 2023. «Healthy and Infected Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar) Skin-Mucus Response to Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi under in Vitro Conditions». Fish & Shellfish Immunology 136 (mayo):108747. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T., B. North, A. P. Scott, N.R. Bromage, M. Porter, y D. Gadd. 2002. «The Relationships between Stocking Density and Welfare in Farmed Rainbow Trout». Journal of Fish Biology 61 (3): 493-531. [CrossRef]

- Ewels, Philip, Måns Magnusson, Sverker Lundin, y Max Käller. 2016. «MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report». Bioinformatics 32 (19): 3047-48. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Álvarez, Clara, y Ysabel Santos. 2018. «Identification and Typing of Fish Pathogenic Species of the Genus Tenacibaculum». Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 102 (23): 9973-89. [CrossRef]

- Florio, Daniela, Stefano Gridelli, Maria Letizia Fioravanti, y Renato Giulio Zanoni. 2016. «FIRST ISOLATION OF TENACIBACULUM MARITIMUM IN A CAPTIVE SAND TIGER SHARK ( CARCHARIAS TAURUS )». Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 47 (1): 351-53. [CrossRef]

- Frelier, Pr, Ra Elston, Jk Loy, y C Mincher. 1994. «Macroscopic and Microscopic Features of Ulcerative Stomatitis in Farmed Atlantic Salmon Salmo Salar». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 18:227-31. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, Alexey, Vladislav Saveliev, Nikolay Vyahhi, y Glenn Tesler. 2013. «QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies». Bioinformatics 29 (8): 1072-75. [CrossRef]

- Habib, Christophe, Armel Houel, Aurélie Lunazzi, Jean-François Bernardet, Anne Berit Olsen, Hanne Nilsen, Alicia E. Toranzo, Nuria Castro, Pierre Nicolas, y Eric Duchaud. 2014. «Multilocus Sequence Analysis of the Marine Bacterial Genus Tenacibaculum Suggests Parallel Evolution of Fish Pathogenicity and Endemic Colonization of Aquaculture Systems». Editado por C. R. Lovell. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 80 (17): 5503-14. [CrossRef]

- Handlinger, J, M Soltani, y S Percival. 1997. «The Pathology of Flexibacter Maritimus in Aquaculture Species in Tasmania, Australia». Journal of Fish Diseases 20 (3): 159-68. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Salmerón, Julie E., y Gabriel Moreno-Hagelsieb. 2022. «FastANI, Mash and Dashing Equally Differentiate between Klebsiella Species». PeerJ 10 (julio):e13784. [CrossRef]

- Irgang, Rute, y Ruben Avendaño-Herrera. 2021. «Experimental Tenacibaculosis Infection in Adult Conger Eel ( Genypterus Chilensis , Guichenot 1948) by Immersion Challenge with Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi». Journal of Fish Diseases 44 (2): 211-16. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2022a. «Evaluation of the in Vitro Susceptibility of Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi to Tiamulin Using Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Tests». Journal of Fish Diseases 45 (6): 795-99. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2022b. «Evaluation of the in Vitro Susceptibility of Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi to Tiamulin Using Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Tests». Journal of Fish Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Klakegg, Øystein, Takele Abayneh, Aud Kari Fauske, Michael Fülberth, y Henning Sørum. 2019. «An Outbreak of Acute Disease and Mortality in Atlantic Salmon ( Salmo Salar ) Post-smolts in Norway Caused by Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi». Journal of Fish Diseases 42 (6): 789-807. [CrossRef]

- Krkosek, Martin, Andrew W. Bateman, Arthur L. Bass, William S. Bugg, Brendan M. Connors, Christoph M. Deeg, Emiliano Di Cicco, et al. 2024. «Pathogens from Salmon Aquaculture in Relation to Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon in Canada». Science Advances 10 (42): eadn7118. [CrossRef]

- Kumanan, Karthiga, Ulla Von Ammon, Andrew Fidler, Jane E. Symonds, Seumas P. Walker, Jeremy Carson, y Kate S. Hutson. 2022. «Advantages of Selective Medium for Surveillance of Tenacibaculum Species in Marine Fish Aquaculture». Aquaculture 558 (septiembre):738365. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Bo, Dandan Zheng, Qi Jin, Lihong Chen, y Jian Yang. 2019. «VFDB 2019: A Comparative Pathogenomic Platform with an Interactive Web Interface». Nucleic Acids Research 47 (D1): D687-92. [CrossRef]

- Mabrok, Mahmoud, Abdelazeem M. Algammal, Elayaraja Sivaramasamy, Helal F. Hetta, Banan Atwah, Saad Alghamdi, Aml Fawzy, Ruben Avendaño-Herrera, y Channarong Rodkhum. 2023. «Tenacibaculosis caused by Tenacibaculum maritimum: Updated knowledge of this marine bacterial fish pathogen». Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 12 (enero):1068000. [CrossRef]

- Manley, Christopher B., Chet F. Rakocinski, Phillip G. Lee, y Reginald B. Blaylock. 2014. «Stocking Density Effects on Aggressive and Cannibalistic Behaviors in Larval Hatchery-Reared Spotted Seatrout, Cynoscion Nebulosus». Aquaculture 420-421 (enero):89-94. [CrossRef]

- McArthur, Andrew G., Nicholas Waglechner, Fazmin Nizam, Austin Yan, Marisa A. Azad, Alison J. Baylay, Kirandeep Bhullar, et al. 2013. «The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database». Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 57 (7): 3348-57. [CrossRef]

- Michnik, Matthew L, Shawna L Semple, Reema N Joshi, Patrick Whittaker, y Daniel R Barreda. 2024. «The Use of Salmonid Epithelial Cells to Characterize the Toxicity of Tenacibaculum Maritimum Soluble Extracellular Products». Journal of Applied Microbiology 135 (3): lxae049. [CrossRef]

- Notti, Ryan Q., y C. Erec Stebbins. 2016. «The Structure and Function of Type III Secretion Systems». Editado por Indira T. Kudva. Microbiology Spectrum 4 (1): 4.1.09. [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, Joseph P., John S. Lumsden, y Spencer Russell. 2021. «Quantitative PCR for Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi and T. Finnmarkense». Journal of Fish Diseases 44 (5): 655-59. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Pedro H., Marie Touchon, y Eduardo P.C. Rocha. 2014. «The Interplay of Restriction-Modification Systems with Mobile Genetic Elements and Their Prokaryotic Hosts». Nucleic Acids Research 42 (16): 10618-31. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Ab, H Nilsen, N Sandlund, H Mikkelsen, H Sørum, y Dj Colquhoun. 2011. «Tenacibaculum Sp. Associated with Winter Ulcers in Sea-Reared Atlantic Salmon Salmo Salar». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 94 (3): 189-99. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Anne Berit, Snorre Gulla, Terje Steinum, Duncan J. Colquhoun, Hanne K. Nilsen, y Eric Duchaud. 2017. «Multilocus Sequence Analysis Reveals Extensive Genetic Variety within Tenacibaculum Spp. Associated with Ulcers in Sea-Farmed Fish in Norway». Veterinary Microbiology 205 (junio):39-45. [CrossRef]

- Ostland, V. E., D. Morrison, y H. W. Ferguson. 1999a. «Flexibacter Maritimus Associated with a Bacterial Stomatitis in Atlantic Salmon Smolts Reared in Net-Pens in British Columbia». Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 11 (1): 35-44.

- ———. 1999b. «Flexibacter Maritimus Associated with a Bacterial Stomatitis in Atlantic Salmon Smolts Reared in Net-Pens in British Columbia». Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 11 (1): 35-44.

- ———. 1999c. «Flexibacter Maritimus Associated with a Bacterial Stomatitis in Atlantic Salmon Smolts Reared in Net-Pens in British Columbia». Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 11 (1): 35-44.

- Papadopoulou, Athina, Andrew Davie, Sean J. Monaghan, Herve Migaud, y Alexandra Adams. 2021. «Development of Diagnostic Assays for Differentiation of Atypical Aeromonas Salmonicida vapA Type V and Type VI in Ballan Wrasse ( Labrus Bergylta , Ascanius)». Journal of Fish Diseases 44 (6): 711-19.

- Pazos, F, Y Santos, A R Macias, S Nunez, y A E Toranzo. 1996. «Evaluation of Media for the Successful Culture of Flexibacter Maritimus». Journal of Fish Diseases 19 (2): 193-97. [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Vidal, Maximino, Daniel Gijón, Carles Zarza, y Ysabel Santos. 2012. «Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi Sp. Nov., a Marine Bacterium of the Family Flavobacteriaceae Isolated from European Sea Bass». International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 62 (2): 425-29. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E. P.C. 2001. «Evolutionary Role of Restriction/Modification Systems as Revealed by Comparative Genome Analysis». Genome Research 11 (6): 946-58. [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga-Córdoba, Mónica, Rute Irgang, y Ruben Avendaño-Herrera. 2021. «Comparison between Genome Sequences of Chilean Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi Isolated from Red Conger Eel ( Genypterus Chilensis ) and Atlantic Salmon ( Salmo Salar ) Focusing on Bacterial Virulence Determinants». Journal of Fish Diseases 44 (11): 1843-60. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, Torsten. 2014. «Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation». Bioinformatics 30 (14): 2068-69. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, Migun, Sanaa A. Ahmed, Karen W. Davenport, Mark C. Flynn, Chien-Chi Lo, y Patrick S. G. Chain. 2020. «Standardized Phylogenetic and Molecular Evolutionary Analysis Applied to Species across the Microbial Tree of Life». Scientific Reports 10 (1): 1723. [CrossRef]

- Småge, Sverre Bang, Øyvind Jakobsen Brevik, Henrik Duesund, Karl Fredrik Ottem, Kuninori Watanabe, y Are Nylund. 2016. «Tenacibaculum Finnmarkense Sp. Nov., a Fish Pathogenic Bacterium of the Family Flavobacteriaceae Isolated from Atlantic Salmon». Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109 (2): 273-85. [CrossRef]

- Småge, Sverre Bang, Kathleen Frisch, Øyvind Jakobsen Brevik, Kuninori Watanabe, y Are Nylund. 2016. «First Isolation, Identification and Characterisation of Tenacibaculum Maritimum in Norway, Isolated from Diseased Farmed Sea Lice Cleaner Fish Cyclopterus Lumpus L». Aquaculture 464 (noviembre):178-84. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, Alexandros. 2014. «RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies». Bioinformatics 30 (9): 1312-13. [CrossRef]

- Valdes, Sara, Rute Irgang, María C. Barros, Pedro Ilardi, Mónica Saldarriaga-Córdoba, Javier Rivera–Bohle, Enrique Madrid, Johana Gajardo–Córdova, y Ruben Avendaño-Herrera. 2021. «First Report and Characterization of Tenacibaculum Maritimum Isolates Recovered from Rainbow Trout ( Oncorhynchus Mykiss ) Farmed in Chile». Journal of Fish Diseases 44 (10): 1481-90. [CrossRef]

- Wade, Nicholas M., Timothy D. Clark, Ben T. Maynard, Stuart Atherton, Ryan J. Wilkinson, Richard P. Smullen, y Richard S. Taylor. 2019. «Effects of an Unprecedented Summer Heatwave on the Growth Performance, Flesh Colour and Plasma Biochemistry of Marine Cage-Farmed Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar)». Journal of Thermal Biology 80 (febrero):64-74. [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, H., M. Hikida, y K. Masumura. 1986. «Flexibacter Maritimus Sp. Nov., a Pathogen of Marine Fishes». International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 36 (3): 396-98. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Tk, M Douglas, y V Dunn. 2019a. «First Identification in Tasmania of Fish Pathogens Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi and T. Soleae and Multiplex PCR for These Organisms and T. Maritimum». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 136 (3): 219-26. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2019b. «First Identification in Tasmania of Fish Pathogens Tenacibaculum Dicentrarchi and T. Soleae and Multiplex PCR for These Organisms and T. Maritimum». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 136 (3): 219-26. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).