Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. RNA as an Organic Code

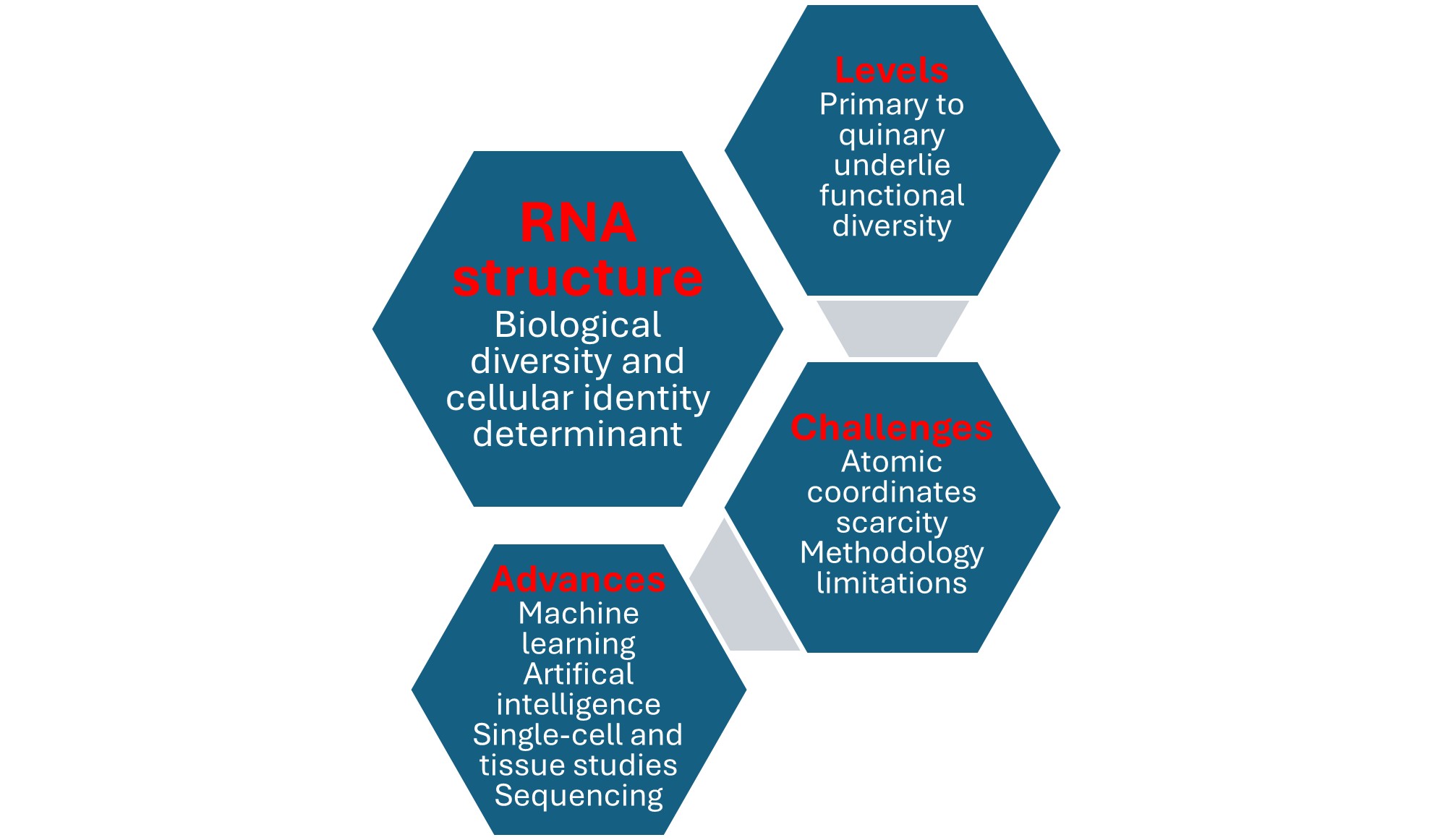

2. RNA Has Many Functions Through Its Intricate, Ubiquitous, Diverse, And Dynamic Structure

3. RNA's Structure Is Defined at Primary, Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary, And Quinary Levels

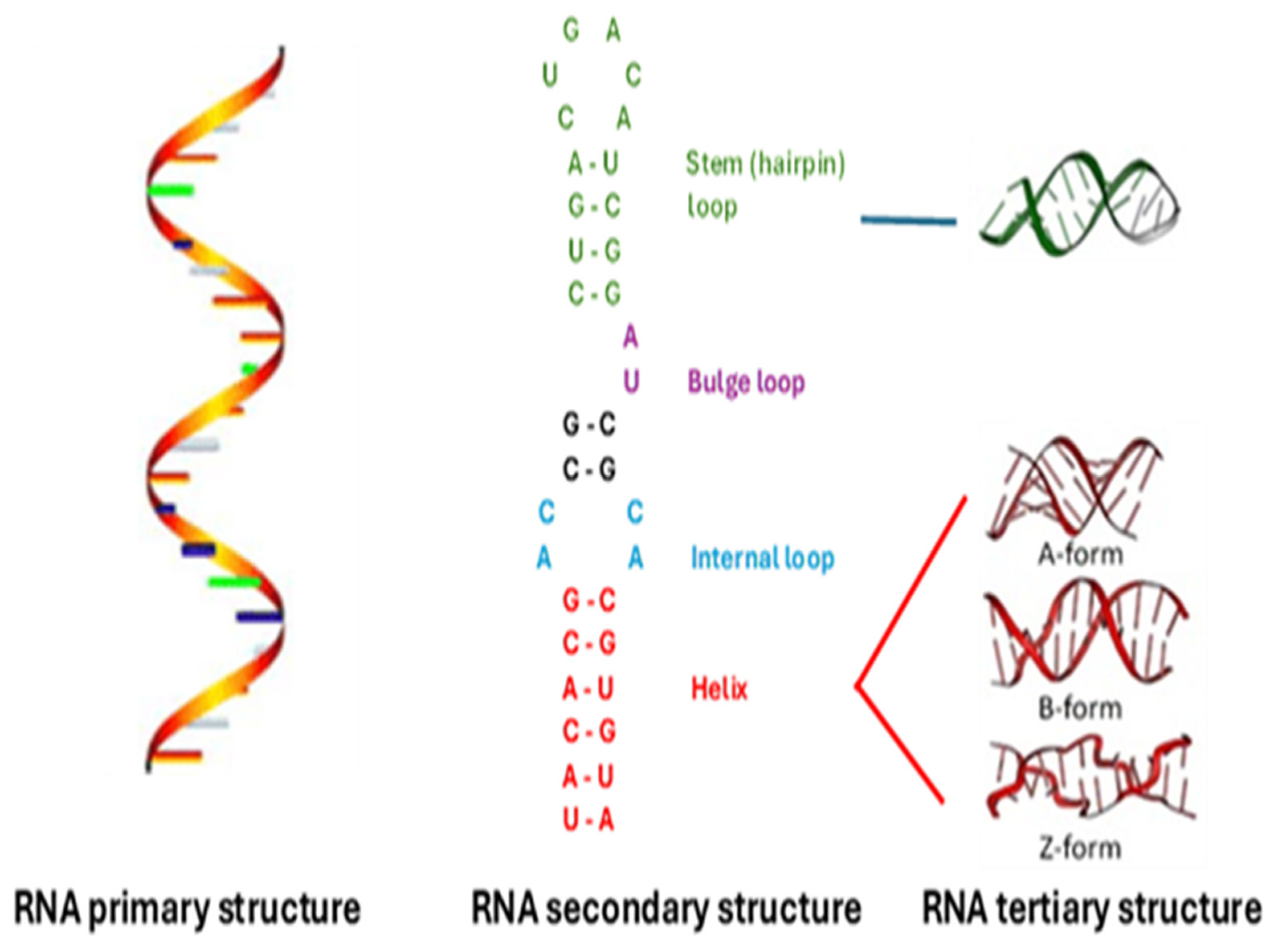

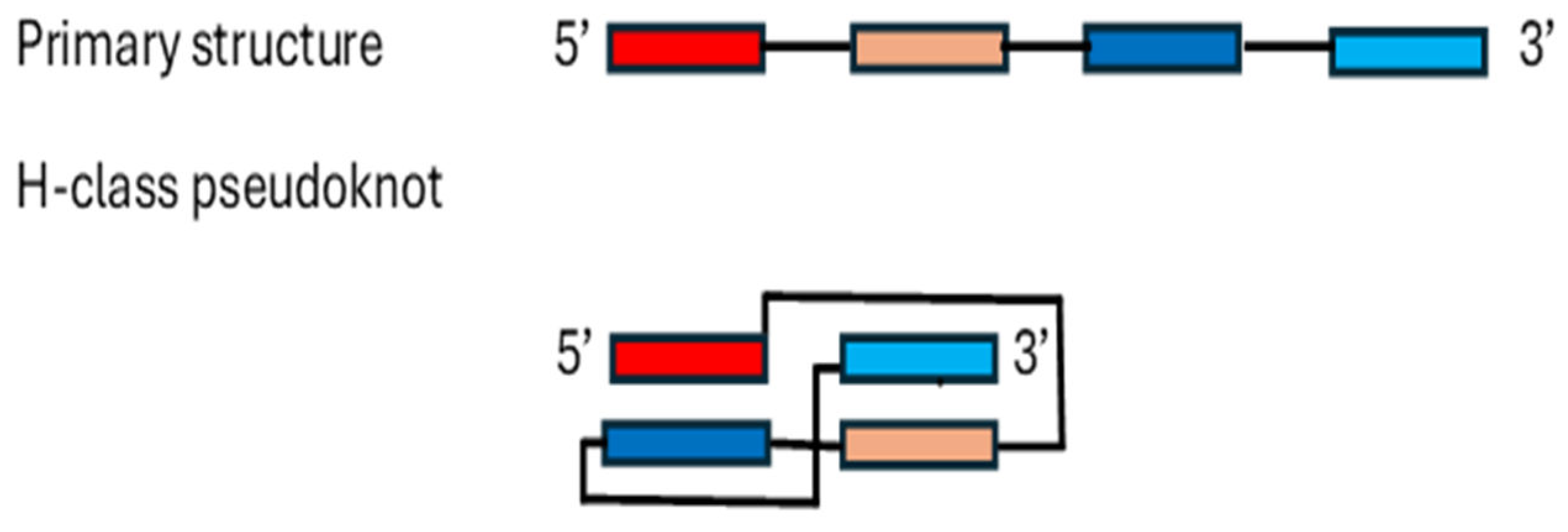

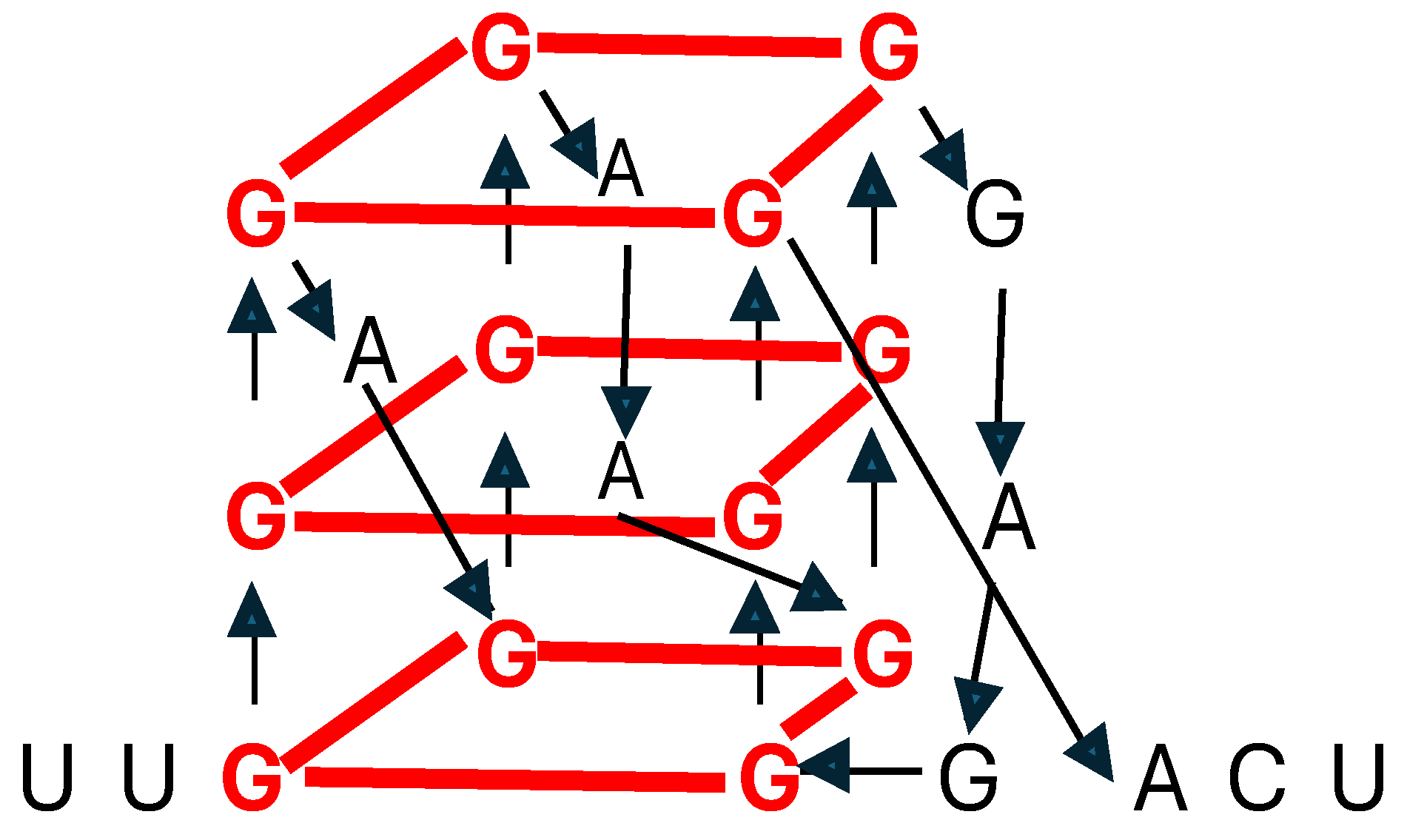

3.1. Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary RNA STRUCTURES

3.2. Quaternary and Quinary RNA Structures

4. Determining RNA Tertiary and Beyond Structures Remains Challenging

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maraldi, N.M. In search of a primitive signaling code. Biosystems 2019, 183, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, A. , Jiménez-Rojo, N. Cracking the membrane lipid code. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2023, 83, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabius, H.J. , Cudic, M., Diercks, T., Kaltner, H., Kopitz, J., Mayo, K.H., Murphy, P.V., Oscarson, S., Roy, R., Schedlbauer, A., Toegel, S., Romero, A. What is the Sugar Code? Chembiochem 2022, 23, e202100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. , Yadav, S. The Origin of Prebiotic Information System in the Peptide/RNA World: A Simulation Model of the Evolution of Translation and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2019, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. , Yadav, S. The Coevolution of Biomolecules and Prebiotic Information Systems in the Origin of Life: A Visualization Model for Assembling the First Gene. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riego, E. , Silva, A., De la Fuente, J. The sound of the DNA language. Biol Res 1995, 28, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Sousa, A. , Baquero, F., Nombela, C. The making of "The Genoma Music". Rev Iberoam Micol 2005, 22, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, M.D. An auditory display tool for DNA sequence analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T. , Prosdocimi, F., Caponi, G. Organic Codes: A Unifying Concept for Life. Acta Biotheor 2021, 69, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratyeva, L.G. , Dyachkova, M.S., Galchenko, A.V. The Origin of Genetic Code and Translation in the Framework of Current Concepts on the Origin of Life. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2022, 87, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlinova, P. , Lambert, C.N., Malaterre, C., Nghe, P. Abiogenesis through gradual evolution of autocatalysis into template-based replication. FEBS Lett 2023, 597, 344–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseltine, W.A. , Patarca, R. The RNA revolution in the central molecular biology dogma evolution. Preprints 2024, 2024110983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H. , Barnett, L., Brenner, S., Watts-Tobin, R.J. General nature of the genetic code for proteins. Nature 1961, 192, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portin, P. The birth and development of the DNA theory of inheritance: sixty years since the discovery of the structure of DNA. J Genet 2014, 93, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm, R. Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA. Dev Biol 2005, 278, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, R. Ueber nucleinsäuren. Arch. f. Anat. u. Physiol. Physiol. Abt. 1889, 524–536.Smýkal, P., K Varshney, R., K Singh, V., Coyne, C.J., Domoney, C., Kejnovský, E., Warkentin, T. From Mendel's discovery on pea to today's plant genetics and breeding : Commemorating the 150th anniversary of the reading of Mendel's discovery. Theor Appl Genet 2016, 129, 2267–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A. On the biochemistry of nucleic acids. J Am Chem Soc 1910, 32, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frixione, E. , Ruiz-Zamarripa, L. The "scientific catastrophe" in nucleic acids research that boosted molecular biology. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 2249–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A., and Bass, L.W. (1931) Nucleic Acids, Chemical Catalog Company, New York: Available online at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b4165245;view=1up;seq=5 (Accessed August 8, 2024).

- Levene, P.A. , Tipson, R.S. The ring structure of adenosine. Science 1931, 74, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A. , Tipson, R.S. The ring structure of thymidine. Science 1935, 81, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, O.T. , Macleod, C.M., McCarty, M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of Pneumococcal types: Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus type III. J Exp Med 1944, 79, 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chargaff, E. Chemical specificity of nucleic acids and mechanism of their enzymatic degradation. Experientia 1950, 6, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, M.H. , Stokes, A.R., Wilson, H.R. Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids. Nature 1953, 171, 738–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, M.H. , Stokes, A.R., Wilson, H.R. Molecular structure of nucleic acids. Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995, 758, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.E. , Gosling, R.G. Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate. Nature 1953, 171, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.E. , Gosling, R.G. Evidence for 2-chain helix in crystalline structure of sodium deoxyribonucleate. Nature 1953, 172, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D. , Crick, F.H. Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D. , Crick, F.H. The structure of DNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1953, 18, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D. , 1928-. The Double Helix: a Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1981.

- Watson, J.D. , Crick, F.H. Genetical implications of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature 1953, 171, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, P. Base crystallization and base stacking in water. Eur J Biochem 1979, 96, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.H. , Quigley, G.J., Kolpak, F.J., Crawford, J.L., van Boom, J.H., van der Marel, G., Rich, A. Molecular structure of a left-handed double helical DNA fragment at atomic resolution. Nature 1979, 282, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wing, R. , Drew, H., Takano, T., Broka, C., Tanaka, S., Itakura, K., Dickerson, R.E. Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA. Nature 1980, 287, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, A. A Genetic Instruction Code Based on DNA Conformation. Trends Genet 2019, 35, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, A. The ancient Z-DNA and Z-RNA specific Zα fold has evolved modern roles in immunity and transcription through the natural selection of flipons. R Soc Open Sci 2024, 11, 240080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, D.R. , Hiscox, T.J., Rood, J.I., Bambery, K.R., McNaughton, D., Wood, B.R. Detection of an en masse and reversible B- to A-DNA conformational transition in prokaryotes in response to desiccation. J R Soc Interface 2014, 11, 20140454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaio, F. , Yu, X., Rensen, E., Krupovic, M., Prangishvili, D., Egelman, E.H. Virology. A virus that infects a hyperthermophile encapsidates A-form DNA. Science 2015, 348, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. , Majima, T. Conformational changes of non-B DNA. Chem Soc Rev 2011, 40, 5893–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, A. , Muskhelishvili, G. DNA structure and function. FEBS J 2015, 282, 2279–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Martinez, C.D., Zeraati, M., Rouet, R., Mazigi, O., Henry, J.Y., Gloss, B., Kretzmann, J.A., Evans, C.W., Ruggiero, E., Zanin, I., Marušič, M., Plavec, J., Richter, S.N., Bryan, T.M., Smith, N.M., Dinger, M.E., Kummerfeld, S., Christ, D. Human genomic DNA is widely interspersed with i-motif structures. The EMBO J 2024. [CrossRef]

- Guneri, D. , Alexandrou, E., El Omari, K., Dvořáková, Z., Chikhale, R.V., Pike, D.T.S., Waudby, C.A., Morris, C.J., Haider, S., Parkinson, G.N., Waller, Z.A.E. Structural insights into i-motif DNA structures in sequences from the insulin-linked polymorphic region. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, Y. , Langridge, R., Shortle, B.E., Cantor, C.R., Grant, R.C., Kodama, M., Wells, R.D. "Physical and enzymatic studies on poly d(I–C)·poly d(I–C), an unusual double-helical DNA". Nature 1970, 228, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, J.B. , Nichols, P.J., Henen, M.A., Vicens, Q., Vögeli, B. Structure and Formation of Z-DNA and Z-RNA. Molecules 2023, 28, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, R.E. , Gosling, R.G. The structure of sodium thermonucleate fibres. I. The influence of water content. Acta Cryst 1953, 6, 673–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K. , Cruz, P., Tinoco, I. Jr., Jovin, T.M., van de Sande, J.H. 'Z-RNA'--a left-handed RNA double helix. Nature 1984, 311, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.W. , Adamiak, R.W., Tinoco, I. Jr. Z-RNA: the solution NMR structure of r(CGCGCG). Biopolymers 1990, 29, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenda, M. , Milecki, J., Adamiak, R.W. High salt solution structure of a left-handed RNA double helix. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 4044–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A. , Alfken, J., Kim, Y.G., Mian, I.S., Nishikura, K., Rich, A. A Z-DNA binding domain present in the human editing enzyme, double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 8421–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G. , Lowenhaupt, K., Oh, D.B., Kim, K.K., Rich, A. Evidence that vaccinia virulence factor E3L binds to Z-DNA in vivo: Implications for development of a therapy for poxvirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 1514–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, T. , Rould, M.A., Lowenhaupt, K., Herbert, A., Rich, A. Crystal structure of the Zalpha domain of the human editing enzyme ADAR1 bound to left-handed Z-DNA. Science 1999, 284, 1841–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.A. 2nd, Lowenhaupt, K., Wilbert, C.M., Hanlon, E.B., Rich, A. The zalpha domain of the editing enzyme dsRNA adenosine deaminase binds left-handed Z-RNA as well as Z-DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 13532–13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placido, D. , Brown, B.A. 2nd, Lowenhaupt, K., Rich, A., Athanasiadis, A. A left-handed RNA double helix bound by the Z alpha domain of the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1. Structure 2007, 15, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pereira, J.M. , Aguilera, A. R loops: new modulators of genome dynamics and function. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhola, M. , Abe, K., Orozco, P., Rahnamoun, H., Avila-Lopez, P., Taylor, E., Muhammad, N., Liu, B., Patel, P., Marko, J.F., Starner, A.C., He, C., Van Nostrand, E.L., Mondragón, A., Lauberth, S.M. RNA interacts with topoisomerase I to adjust DNA topology. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 3192–3208.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J. , Gooding, A.R., Hemphill, W.O., Love, B.D., Robertson, A., Yao, L., Zon, L.I., North, T.E., Kasinath, V., Cech, T.R. Structural basis for inactivation of PRC2 by G-quadruplex RNA. Science 2023, 381, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y. , Lu, Y., Ferrari, M.M., Channagiri, T., Xu, P., Meers, C., Zhang, Y., Balachander, S., Park, V.S., Marsili, S., Pursell, Z.F., Jonoska, N., Storici, F. RNA-mediated double-strand break repair by end-joining mechanisms. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.H. , Androsavich, J.R., So, N., Jenkins, M.P., MacCormack, D., Prigodich, A., Welch, V., True, J.M., Dolsten, M. Breaking the mold with RNA-a "RNAissance" of life science. NPJ Genom Med 2024, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M. The human transcriptome: an unfinished story. Genes (Basel) 2012, 3, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L. , Huber, W., Granovskaia, M., Toedling, J., Palm, C.J., Bofkin, L., Jones, T., Davis, R.W., Steinmetz, L.M. A high-resolution map of transcription in the yeast genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 5320–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczyk, M. , Kasprowicz, M.K., Kasprzyk, M.E., Wrzesinski, J. Human Long Noncoding RNA Interactome: Detection, Characterization and Function. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.C. , Ephrussi, A. mRNA localization: gene expression in the spatial dimension. Cell 2009, 136, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y. , Kertesz, M., Spitale, R.C., Segal, E., Chang, H.Y. Understanding the transcriptome through RNA structure. Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y. , Liu, H., Liu, Y., Tao, S. Deciphering the rules by which dynamics of mRNA secondary structure affect translation efficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 4813–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, S., Brown, W. Translation: DNA to mRNA to protein. Nat Educ 2008, 1, 101.

- Garneau, N.L. , Wilusz, J., Wilusz, C.J. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Tan, W.T., Lambert, F., Darmawan, J., Huber, R., Wan, Y. RNA structure profiling at single-cell resolution reveals new determinants of cell identity. Nat Methods 2024, 21, 411-422. [CrossRef]

- Tomezsko, P.J. , Corbin, V.D.A., Gupta, P., Swaminathan, H., Glasgow, M., Persad, S., Edwards, M.D., McIntosh, L., Papenfuss, A.T., Emery, A, et al.. Determination of RNA structural diversity and its role in HIV-1 RNA splicing. Nature 2020, 582, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicens, Q. , Kieft, J.S. Thoughts on how to think (and talk) about RNA structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2112677119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assmann, S.M. , Chou, H.L., Bevilacqua, P.C. Rock, scissors, paper: How RNA structure informs function. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1671–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shine, M. , Gordon, J., Schärfen, L., Zigackova, D., Herzel, L., Neugebauer, K.M. Co-transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhof, E. , Fritsch, V. RNA folding: beyond Watson-Crick pairs. Structure 2000, 8, R55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.A. , Westhof, E. The dynamic landscapes of RNA architecture. Cell 2009, 136, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, L.R. , Kelly, M.L., Herschlag, D., Al-Hashimi, H.M. The roles of structural dynamics in the cellular functions of RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C. , Fichou, Y., Huber, K., Weiss, M., Spruijt, E., Ebbinghaus, S., De Luca, G., Morando, M.A., Vetri, V., Temussi, P.A., Pastore, A. Molecular Crowding: The History and Development of a Scientific Paradigm. Chem Rev 2024, 124, 3186–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultes, E.A. , Spasic, A., Mohanty, U., Bartel, D.P. Compact and ordered collapse of randomly generated RNA sequences. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005, 12, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dethoff, E.A. , Chugh, J., Mustoe, A.M., Al-Hashimi, H.M. Functional complexity and regulation through RNA dynamics. Nature 2012, 482, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustoe, A.M. , Brooks, C.L., Al-Hashimi, H.M. Hierarchy of RNA functional dynamics. Annu Rev Biochem 2014, 83, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, R. , Saleem, I., Mustoe, A.M. Causes, functions, and therapeutic possibilities of RNA secondary structure ensembles and alternative states. Cell Chem Biol 2024, 31, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. , Zhang, Q.C., Lee, B., Flynn, R.A., Smith, M.A., Robinson, J.T., Davidovich, C., Gooding, A.R., Goodrich, K.J., Mattick, J.S., Mesirovm J.P., Cech, T.R., Chang, H.Y. RNA Duplex Map in Living Cells Reveals Higher-Order Transcriptome Structure. Cell 2016, 165, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlea, L.G. , Sweeney, B.A., Hosseini-Asanjan, M., Zirbel, C.L., Leontis, N.B. The RNA 3D Motif Atlas: Computational methods for extraction, organization and evaluation of RNA motifs. Methods 2016, 103, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin-Gendron, R. , Waldispühl, J., Reinharz, V. Classification and Identification of Non-canonical Base Pairs and Structural Motifs. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2726, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, T. , Westhof, E. Non-Watson-Crick base pairs in RNA-protein recognition. Chem Biol 1999, 6, R335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, T. , Patel, D.J. Adaptive recognition by nucleic acid aptamers. Science 2000, 287, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontis, N.B. , Westhof, E. Analysis of RNA motifs. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2003, 13, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.A. , Westhof, E. Sequence-based identification of 3D structural modules in RNA with RMDetect. Nat Methods 2011, 8, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdani, H.Y. , Appasamy, S.D., Willett, P., Artymiuk, P.J., Firdaus-Raih, M. NASSAM: a server to search for and annotate tertiary interactions and motifs in three-dimensional structures of complex RNA molecules. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, issue):W35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.Y. , Lin, J.C., Chen, K.T., Lu, C.L. R3D-BLAST2: an improved search tool for similar RNA 3D substructures. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emrizal, R. , Hamdani, H.Y., Firdaus-Raih, M. Graph Theoretical Methods and Workflows for Searching and Annotation of RNA Tertiary Base Motifs and Substructures. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, N.S.A. , Emrizal, R., Moffit, S.M., Hamdani, H.Y., Ramlan, E.I., Firdaus-Raih, M. GrAfSS: a webserver for substructure similarity searching and comparisons in the structures of proteins and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, W375–W383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.L., Berman, H.M., Chen, L., Vallat, B., Zirbel, C.L. The Nucleic Acid Knowledgebase: a new portal for 3D structural information about nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D245-D254. [CrossRef]

- Staple, D.W. , Butcher, S.E. Pseudoknots: RNA structures with diverse functions. PLoS Biol 2005, 3, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, P. , Ivanov, P. RNA G-quadruplexes and stress: emerging mechanisms and functions. Trends Cell Biol 2024, 34, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D. , Draper, D.E. Effects of osmolytes on RNA secondary and tertiary structure stabilities and RNA-Mg2+ interactions. J Mol Biol 2007, 370, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnon, L.A. , Edera, A.A., Prochetto, S., Gerard, M., Raad, J., Fenoy, E., Rubiolo, M., Chorostecki, U., Gabaldón, T., Ariel, F., Di Persia, L.E., Milone, D.H., Stegmayer, G. Secondary structure prediction of long noncoding RNA: review and experimental comparison of existing approaches. Brief Bioinform 2022, 23, bbac205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. , Li, S., Kappel, K., Pintilie, G., Su, Z., Mou, T.C., Schmid, M.F., Das, R., Chiu, W. Cryo-EM structure of a 40 kDa SAM-IV riboswitch RNA at 3.7 Å resolution. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, C. , Postic, G., Ghannay, S., Tahi, F. State-of-the-RNArt: benchmarking current methods for RNA 3D structure prediction. NAR Genom Bioinform 2024, 6, lqae048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. , Ge, P., Zhang, S. CompAnnotate: a comparative approach to annotate base-pairing interactions in RNA 3D structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Z. , Wu, H., Li, S.S., Li, H.Z., Zhang, B.G., Tan, Y.L. ABC2A: A Straightforward and Fast Method for the Accurate Backmapping of RNA Coarse-Grained Models to All-Atom Structures. Molecules 2024, 29, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Z.R. , Pyle, A.M., Zhang, C. Arena: Rapid and Accurate Reconstruction of Full Atomic RNA Structures From Coarse-grained Models. J Mol Biol 2023, 435, 168210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townshend, R.J.L., Eismann, S., Watkins, A.M., Rangan, R., Karelina, M., Das, R., Dror, R.O. Geometric deep learning of RNA structure. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2021, 373, 1047–1051. Erratum in: Science 2023, 379, eadg6616. 2021, 373, 1047–1051. [CrossRef]

- Peattie, D.A. , Gilbert, W. Chemical probes for higher-order structure in RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980, 77, 4679–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehresmann, C. , Baudin, F., Mougel, M., Romby, P., Ebel, J.P., Ehresmann, B. Probing the structure of RNAs in solution. Nucleic Acids Res 1987, 15, 9109–9128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incarnato, D. , Neri, F., Anselmi, F., Oliviero, S. Genome-wide profiling of mouse RNA secondary structures reveals key features of the mammalian transcriptome. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y. , Tang, Y., Kwok, C.K., Zhang, Y., Bevilacqua, P.C., Assmann, SM. In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature 2014, 505, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, L.E. , Su, Z., Tang, Y., Tack, D.C., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C. Structure-seq2: sensitive and accurate genome-wide profiling of RNA structure in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, L.E. , Su, Z., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C. In Vivo Genome-Wide RNA Structure Probing with Structure-seq. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1933, 305–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchey, L.E. , Tack, D.C., Yakhnin, H., Jolley, E.A., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C., Babitzke, P. Structure-seq2 probing of RNA structure upon amino acid starvation reveals both known and novel RNA switches in Bacillus subtilis. RNA 2020, 26, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouskin, S. , Zubradt, M., Washietl, S., Kellis, M., Weissman, J.S. Genome-wide probing of RNA structure reveals active unfolding of mRNA structures in vivo. Nature 2014, 505, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubradt, M. , Gupta, P., Persad, S., Lambowitz, A.M., Weissman, J.S., Rouskin, S. DMS-MaPseq for genome-wide or targeted RNA structure probing in vivo. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagami, R. , Sieg, J.P., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C. Genome-wide analysis of the in vivo tRNA structurome reveals RNA structural and modification dynamics under heat stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2201237119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.K. , Marsico, G., Sahakyan, A.B., Chambers, V.S., Balasubramanian, S. rG4-seq reveals widespread formation of G-quadruplex structures in the human transcriptome. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, N.A. , Busan, S., Rice, G.M., Nelson, J.A., Weeks, K.M. RNA motif discovery by SHAPE and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP). Nat Methods 2014, 11, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitale, R.C., Flynn, R.A., Zhang, Q.C., Crisalli, P., Lee, B., Jung, J.W., Kuchelmeister, H.Y., Batista, P.J., Torre, E.A., Kool, E.T., Chang, H.Y. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature 2015, 519, 486-490. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14263. Erratum in: Nature 2015, 527, 264. [CrossRef]

- Spasic, A. , Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C., Mathews, D.H. Modeling RNA secondary structure folding ensembles using SHAPE mapping data. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. , Woolfenden, H.C., Zhang, Y., Fang, X., Liu, Q., Vigh, M.L., Cheema, J., Yang, X., Norris, M., Yu, S., Carbonell, A., Brodersen, P., Wang, J., Ding, Y. Intact RNA structurome reveals mRNA structure-mediated regulation of miRNA cleavage in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 8767–8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. , Cheema, J., Zhang, Y., Deng, H., Duncan, S., Umar, M.I., Zhao, J., Liu, Q., Cao, X., Kwok, C.K., Ding, Y. RNA G-quadruplex structures exist and function in vivo in plants. Genome Biol 2020, 21, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.J. , Zhang, J., Li, P., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., Roy-Chaudhuri, B., Xu, J., Kay, M.A., Zhang, Q.C. RNA structure probing reveals the structural basis of Dicer binding and cleavage. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D. 3rd., Ritchey, L.E., Park, H., Babitzke, P., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C. Glyoxals as in vivo RNA structural probes of guanine base-pairing. RNA 2018, 24, 114–124. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. 3rd., Renda, A.J., Douds, C.A., Babitzke, P., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C. In vivo RNA structural probing of uracil and guanine base-pairing by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC). RNA 2019, 25, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.Y. , Sexton, A.N., Culligan, W.J., Simon, M.D. Carbodiimide reagents for the chemical probing of RNA structure in cells. RNA 2019, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitale, R.C. , Crisalli, P., Flynn, R.A., Torre, E.A., Kool, E.T., Chang, H.Y. RNA SHAPE analysis in living cells. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushhouse, D.Z. , Choi, E.K., Hertz, L.M., Lucks, J.B. How does RNA fold dynamically? J Mol Biol 2022, 434, 167665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A. , Hatfield, A., Lackey, L. How does precursor RNA structure influence RNA processing and gene expression? Biosci Rep 2023, 43, BSR20220149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, A.W. , Evans, R., Jumper, J., Kirkpatrick, J., Sifre, L., Green, T., Qin, C., Žídek, A., Nelson, A.W.R., Bridgland, A., Penedones, H., Petersen, S., Simonyan, K., Crossan, S., Kohli, P., Jones, D.T., Silver, D., Kavukcuoglu, K., Hassabis, D. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 2020, 577, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J. , Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Bates, R., Žídek, A., Potapenko, A., Bridgland, A., Meyer, C., Kohl, S. A. A., Ballard, A. J., Cowie, A., Romera-Paredes, B., Nikolov, S., Jain, R., Adler, J., Back, T., … Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. , Sweeney, B.A., Bateman, A., Cerny, J., Zok, T., Szachniuk, M. When will RNA get its AlphaFold moment? Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 9522–9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z. , Westhof, E. RNA Structure: Advances and Assessment of 3D Structure Prediction. Annu Rev Biophys 2017, 46, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M. , Sun, L., Zhang, Q.C. RNA Regulations and Functions Decoded by Transcriptome-wide RNA Structure Probing. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2017, 15, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. , Zhu, W., Wang, J., Li, W., Gong, S., Zhang, J., Wang, W. RNA3DCNN: Local and global quality assessments of RNA 3D structures using 3D deep convolutional neural networks. PLoS computational biology 2018, 14, e1006514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. , Zhang, S., Zhang, D., Chen, S.J. Vfold-Pipeline: a web server for RNA 3D structure prediction from sequences. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4042–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieng, F.Y.F. , Abdullah-Zawawi, M.R., Md Shahri, N.A.A., Mohamed-Hussein, Z.A., Lee, L.H., Mutalib, N.A. A Hitchhiker's guide to RNA-RNA structure and interaction prediction tools. Brief Bioinform 2023, 25, bbad421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Yu, S., Lou, E., Tan, Y.L., Tan, Z.J. RNA 3D Structure Prediction: Progress and Perspective. Molecules 2023, 28, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.L. , Rose, G.D. RNABase: an annotated database of RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S. , Rahaman, M.M., Islam, S., Zhang, S. RNA-NRD: a non-redundant RNA structural dataset for benchmarking and functional analysis. NAR Genom Bioinform 2023, 5, lqad040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigden, D.J. , Fernández, X.M. The 2024 Nucleic Acids Research database issue and the online molecular biology database collection. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D1–D9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Tsuboi, T. Efficient Prediction Model of mRNA End-to-End Distance and Conformation: Three-Dimensional RNA Illustration Program (TRIP). Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2784, 191-200. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Feng, C., Han, R., Wang, Z., Ye, L., Du, Z., Wei, H., Zhang, F., Peng, Z., Yang, J. trRosettaRNA: automated prediction of RNA 3D structure with transformer network. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szikszai, M. , Magnus, M., Sanghi, S., Kadyan, S., Bouatta, N., Rivas, E. RNA3DB: A structurally-dissimilar dataset split for training and benchmarking deep learning models for RNA structure prediction. J Mol Biol 2024, 168552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakers, J., Blum, C.F., König, S., Harmeling, S., Kollmann, M. De novo prediction of RNA 3D structures with deep generative models. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0297105. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , McRae, E.K.S., Zhang, M., Geary, C., Andersen, E.S., Ren, G. Non-averaged single-molecule tertiary structures reveal RNA self-folding through individual-particle cryo-electron tomography. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on Life Sciences; Toward Sequencing and Mapping of RNA Modifications Committee. Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2024 Jul 22.

- Kanatani, S. , Kreutzmann, J.C., Li, Y., West, Z., Larsen, L.L., Nikou, D.V., Eidhof, I., Walton, A., Zhang, S., Rodríguez-Kirby, L.R., Skytte, J.L., Salinas, C.G., Takamatsu, K., Li, X., Tanaka, D.H., Kaczynska, D., Fukumoto, K., Karamzadeh, R., Xiang, Y., Uesaka, N., Tanabe, T., Adner, M., Hartman, J., Miyakawa, A., Sundström, E., Castelo-Branco, G., Roostalu, U., Hecksher-Sørensen, J., Uhlén, P. Whole-brain spatial transcriptional analysis at cellular resolution. Science 2024, 386, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).