Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

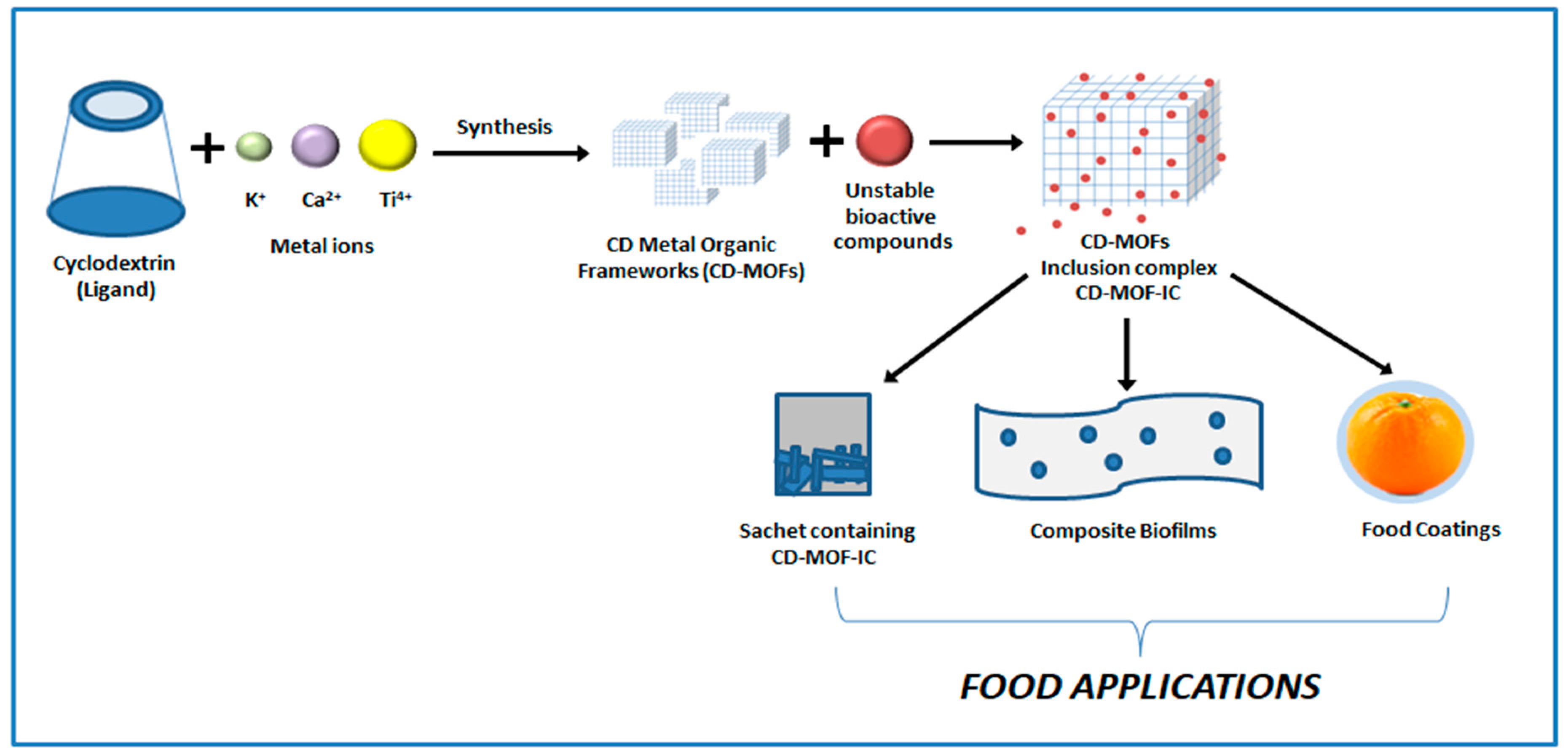

Introduction

Toxicological Profile of Cyclodextrins

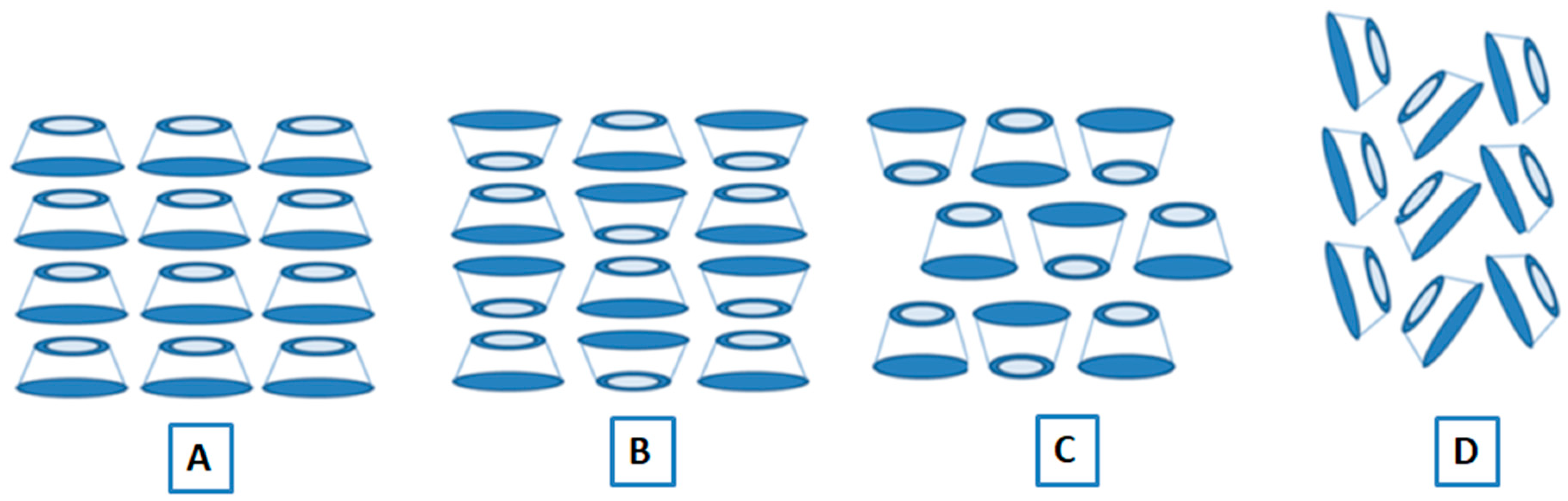

Synthesis of Cycloedxtrin MOFs

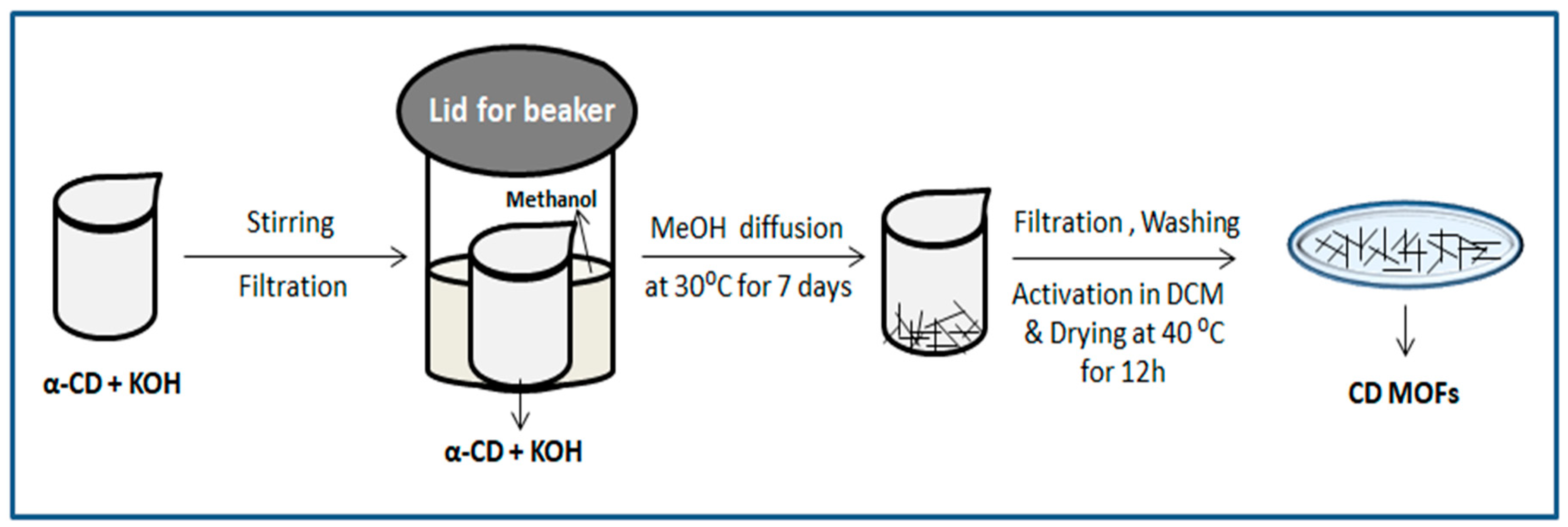

Synthesis of α-CD MOF

Synthesis of β-CD MOF

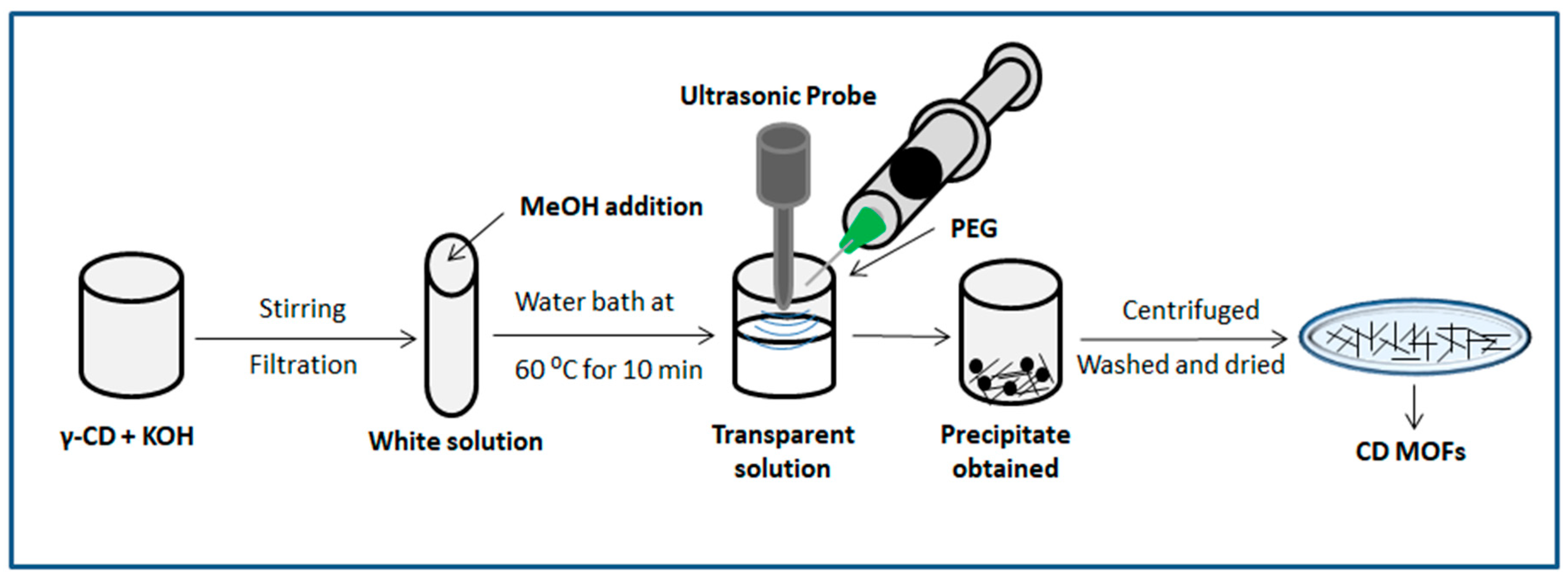

Synthesis of γ-CD-MOF

| Metal Ion (Salt used) | Ligand | Synthesis technique | Conditions | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing / Ultrasonication time |

Temperature for vapour diffusion (°C) | Vapour diffusion time | ||||

| K+ ( C7H5KO2) | α-CD | Vapour diffusion | 6-8h | R.T | 3-7 days | [36] |

| K+ (KOH) | α-CD | Ultrasonication | 30 min | *After ultrasonication, solution was mixed with MeOH, heated at 60°C, cooled to r.t and PEG and MeOH was added to obtain crystals | [37] | |

| K+ (KOH) | β-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | R.T | One week | [38] |

| K+ (KOH) | β-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | 50 | 12h | [39] |

| K+ (KOH) | β-CD | Vapour diffusion | 3h | 25 | - | [40] |

| K+ (KOH) | β-CD | Vapour diffusion | 3.5h | R.T | 3-5 weeks | [41] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasonication | 30 min | - | - | [37] |

| Rb+ (RbOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | R.T | One week | [34] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | 6-12h at 500pm | 23 | One week | [42] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | 60 | 2h | [43] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | 50 | 5h | [44] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasound assisted vapour diffusion | 5 min | 50 | 6h | [45] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasound assisted vapour diffusion | Different time (0, 5, 10, or 15 min) | 50 | 6h | [46] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Seed mediated methanol vapour diffusion | - | 50 | 1h | [47] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasonication | 30min | *After ultrasonication solution was heated at 60°C for 1 h and the PEG 20,000 was added to obtain crystals | [48] | |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | 6h 500rpm | R.T | 3-7 days | [49] |

| K+ ( C7H5KO2) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | 6h 500rpm | R.T | 3-7 days | [49] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasonication | 30 min | *After ultrasonication, solution was mixed with MeOH, heated at 60°C, cooled to r.t and PEG and MeOH was added to obtain crystals | [37] | |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Vapour diffusion | - | 50 | 24h | [50] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Ultrasonication | 30min | *After ultrasonication, solution was mixed with MeOH, heated & cooled to r.t and PEG and MeOH was added to obtain crystals | [51] | |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Seed mediated methanol vapour diffusion | - | 50 | 6 | [52] |

| K+ (KOH) | γ-CD | Seed mediated Ultrasonication | Different time (0, 3, 5, 10, and 15 min) | After ultrasonication, solution was mixed with MeOH to obtain crystals | [53] | |

CD MOFs Applications in Food Industry

- The diffusion and volatility (in the case of volatile substances) of the included guest can decrease strongly.

- The complexed substances, even gaseous substances can be entrapped in a carbohydrate matrix forming a microcrystalline or amorphous powder.

- The complexed substance can be effectively protected against heat decomposition, oxidation, and any other type of reaction, except against those with the hydroxyl groups of cyclodextrin, or reactions catalyzed by them.

| MOF | ACTIVE COMPOUND | APPLICATION | IMPORTANT OBSERVATIONS | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-CD MOF | Ethylene gas | Accelerated fruit ripening | MOF- ethylene complexes had controlled ethylene-release for accelerated fruit ripening | [32] |

| α-CD MOF | Catechin | Potential application in Food packaging | CD-MOFs protected catechin against light, oxygen and temperature, thus improving its storage stability. Catechin encapsulated within CD-MOFs exhibited superior bioavailability | [37] |

| β -CD MOF | - | Herbicide adsorption and potassium replenishment | The maximum adsorption capacities of four herbicides were in the range of 261.21-343.42 mg.g-1. The herbicide removal percentage was in the order: MET>PRE>ALA>ACE. | [55] |

| β-CD MOF | Hexanal | Preservation of Mangoes | Treated fruit remains fresh until 2 weeks after storage. They possessed higher firmness and had lower weight loss. | [56] |

| β-CD MOF | Catechin | Zein based packaging film | Zein films with Catechin loaded β-CD MOFs possessed better physical properties, antibacterial characteristics and more steady release profile for catechin as compared to normal Zein film containing catechin. | [57] |

| β-CD MOF | Clove essential oil (CEO) | Preservation of Chinese Bacon | Decrease in the lipid oxidation of bacon due to the increasing inhibitory effect of CEO after encapsulation in β-CD-MOF. Apart from that, the free radical scavenging activities and thermal and pH stabilities were also better in case of CEO/ β-CD-MOF’s than just CEO | [58] |

| β-CD MOF | Lavender essential oil (LEO) | Potential application in Food packaging | LEO/K-βCD-MOFs were proved to be more thermally and acid-base stable than LEO, and its intracellular antioxidant effect was also significantly improved by encapsulation. | [33] |

| β-CD MOF | Thymol (THY) | Preservation of Cherry Tomatoes | The decay index of whole cherry tomatoes treated with γ-CD-MOF-THY decreased from 67.5% (control group) to less than 20% during storage at room temperature for 15 days. | [40] |

| β-CD MOF | Polyphenols | Potential application in Food packaging | The stabilities and solubility’s of ALP were significantly improved compared when encapsulated in β - CD-MOFs as compared to β -CD, suggesting the potential of β-CD-MOFs as better carriers than β -CD for polyphenols in food industry applications. | [38] |

| β-CD MOF | Origanum Compactum essential oil (OCEO) | Potential application in Food packaging | Compared to βCD, K-βCD-MOFs displayed higher encapsulation efficiency. Antioxidant capacity of OCEO was significantly enhanced in the presence of K-βCD-MOFs | [59] |

| β-CD MOF | - | Extraction of Organochlorine pesticides from Honey samples | CD-MOF/TiO2 has good selective enrichment ability for OCP and is suitable for the D-SPE pre-treat of honey sample analysis. | [60] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Anthocyanins | Grape preservation | Grapes coated with Sodium alginate + CD-MOFs containing anthocyanin showed gradual decrease in weight loss after 10 days. The firmness and epidermal puncture value of the grapes was also high with this coating. Brix value was found to be less as compared to others. | [50] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Ethylene gas | Accelerated ripening as well as preservation of bananas | Polycaprolactone nanofibers containing γ-CD-MOF and TiO2 were used. The γ-CD-MOF were encapsulated with ethylene and helped in the accelerated ripening of bananas while TiO2 under the action of UV helped to degrade ethylene prolonging the shelf life of bananas | [61] |

| γ-CD MOF |

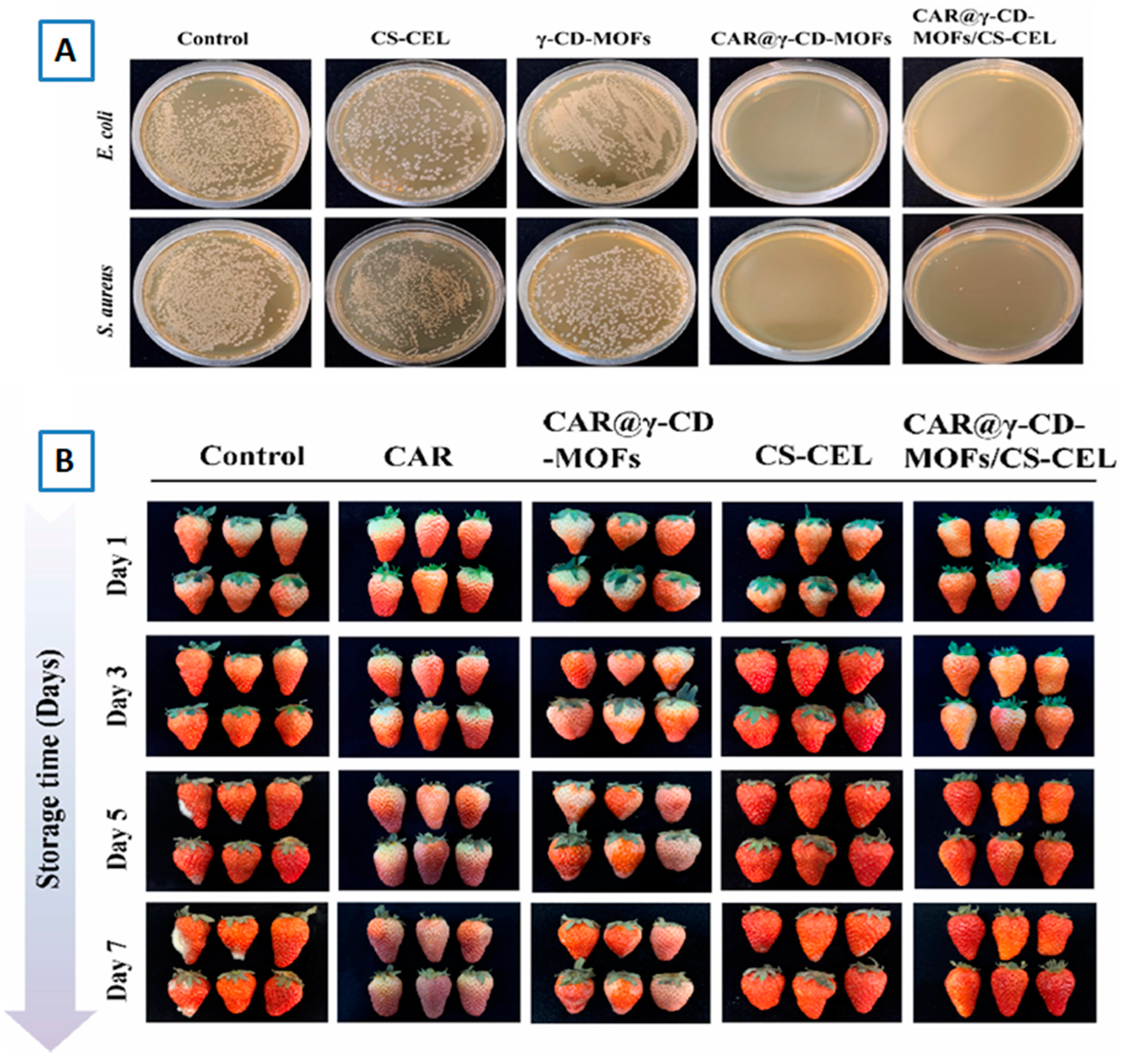

Carvacol | Chitosan-Cellulose(CS-CEL) Active packaging film | CS-CEL films containing Carvacol- γ-CD MOF showed the lowest weight loss in strawberries as compared to other conditions. Also, Carvacol-γ-CD-MOFs/CS-CEL composite film showed the lowest firmness loss, highest TSS value and lowest pH change. |

[62] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Cinnamaldehyde | Preservation of fresh cut cantaloupes | CD/MOF containing cinnamaldehyde (CA) and carbon dots improved the shelf life of the fresh cut cantaloupes was and maintained the quality of the fruit. It was observed that CD/MOF-0.5(amount of carbon dots)/CA exhibited a strong and long-lasting antibacterial activity when tested against E. coli in vitro and on fresh-cut cantaloupes. | [45] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Curcumin | Preservation of Centennial Seedless grapes (CSg) through Pullulan and trehalose (Pul/Tre) composite film containing Curcumin- γ-CD-MOF | The naturally placed CSg began to rot on the 4th day, while the CSg coated with Pul/Tre film rot on the 8th day with a shrunken surface and severe dehydration. However, the appearance of CSg coated with Cur-CD-MOFs-Pul/Tre film was still largely unaltered on day 10. | [44] |

| γ-CD MOF |

- | Ethylene absorber for improving postharvest quality of kiwi fruit | The fruit in the γ-CDMOF-K group did not decay over the whole storage period, maintained a good appearance, and remained edible. | [46] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Octadecenylsuccinic anhydride (ODSA) | Pickering emulsions coating and package paper for fruit preservation | The uncoated bananas experienced a 27.5% weight loss after 9 days, whereas the sample coated with a 10% ODSA emulsion had just 15.6% weight loss. Similarly, the weight loss also reduced in ODSA emulsions containing ODSA modified γ-CD-MOFs. | [63] |

| γ-CD MOF |

β-carotene | Development of High internal phase emulsion(HIPEs) | CD-MOF offers a safeguarding matrix for β-carotene , reducing the degradation and enabling a modulated release profile. | [64] |

| γ-CD MOF |

Vitamin A palmitate | Encapsulation of Vitamin A palmitate (VAP) for delivery as a food supplement | The half-life (t1/2) vitamin A in γ-CD-MOFs/VAP was recorded to be 20.5 days which is a 1.6 time increase compared to BASF vitamin A powder (t1/2 = 13.0 days) and a 2.6 time increase compared to physical mixture (t1/2 = 7.9 days), respectively | [65] |

Characterization of CD-MOFs

1. Thermal Analysis

a. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

b. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2. Microscopy

3. X-Ray Diffraction

4. Spectroscopy

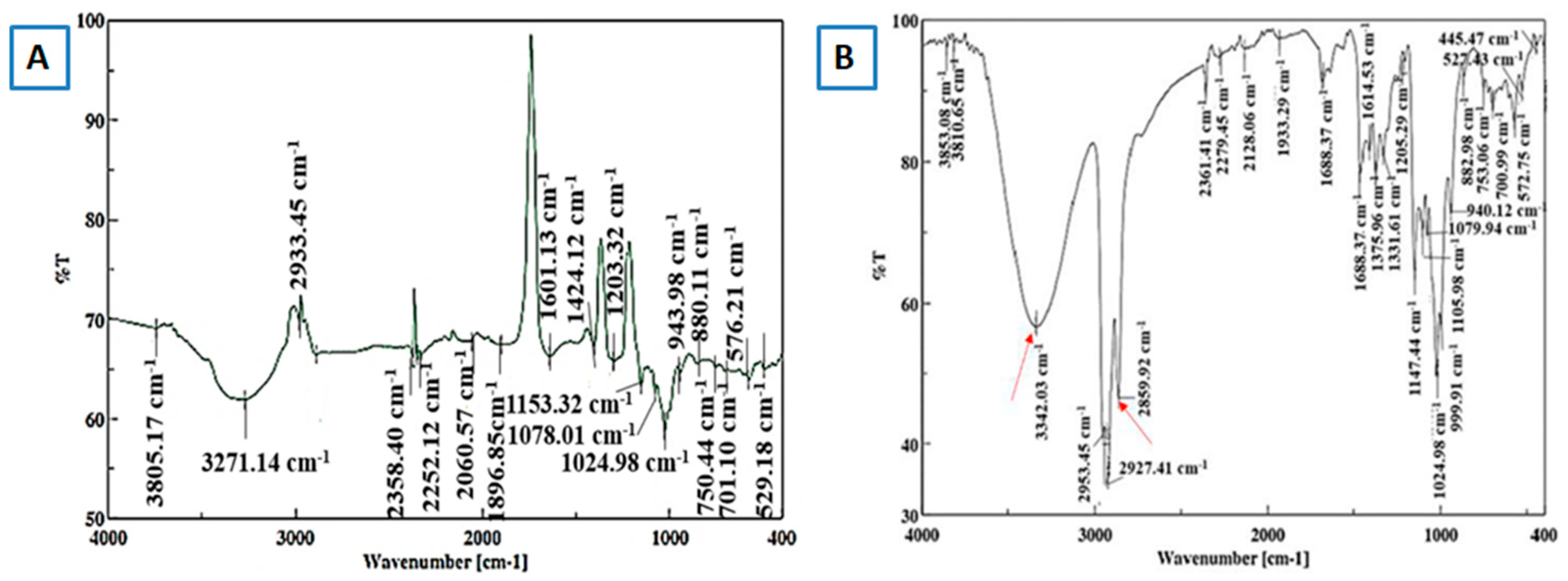

a. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

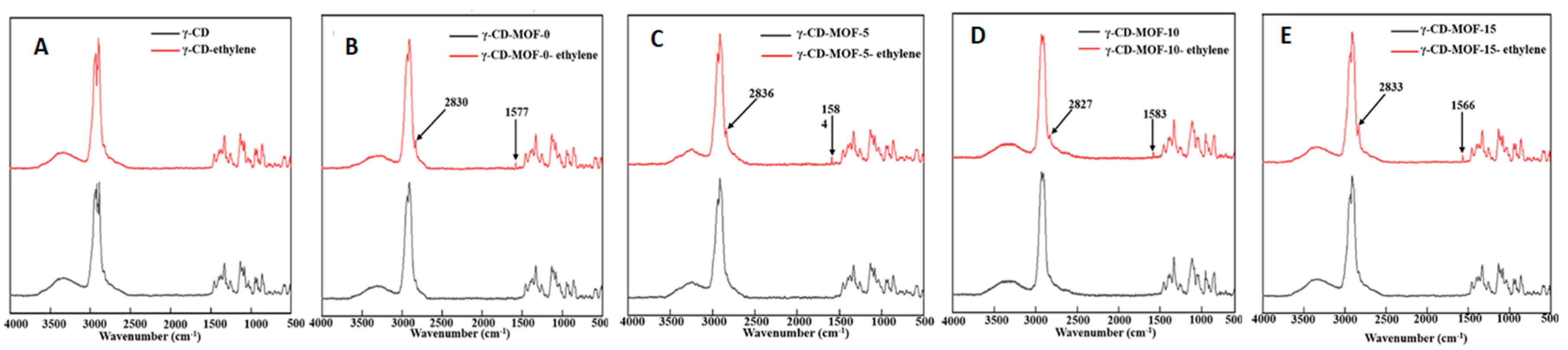

b. Raman Spectroscopy

5. UV-Visible

6. Antibacterial Studies

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Liang, S.; et al. Metal-organic frameworks as novel matrices for efficient enzyme immobilization: An update review. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 406, 213149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; et al. Synthesis and potential applications of cyclodextrin-based metal–organic frameworks: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 21, 447–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, A.; Petriccione, M.; Gutiérrez, T.J. Metal-organic frameworks for food applications: A review. Food Chemistry 2021, 354, 129533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; et al. Preparation of two metal organic frameworks (K-β-CD-MOFs and Cs-β-CD-MOFs) and the adsorption research of myricetin. Polyhedron 2021, 196, 114983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; et al. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; et al. Direct Calorimetric Measurement of Enthalpy of Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide on CD-MOF-2, a Green Metal–Organic Framework. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2013, 135, 6790–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liu, D.; Ding, T. Cyclodextrin-metal-organic frameworks (CD-MOFs): main aspects and perspectives in food applications. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 41, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulson, B.G.; et al. Cyclodextrins: Structural, Chemical, and Physical Properties, and Applications. Polysaccharides 2021, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandilya, A.A.; Natarajan, U.; Priya, M.H. , Molecular View into the Cyclodextrin Cavity: Structure and Hydration. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 25655–25667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejtli, J. , Introduction and General Overview of Cyclodextrin Chemistry. Chemical Reviews 1998, 98, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, K.A. , The Stability of Cyclodextrin Complexes in Solution. Chemical Reviews 1997, 97, 1325–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodziuk, H. Molecules with Holes – Cyclodextrins, in Cyclodextrins and Their Complexes. 2006. p. 1-30.

- Saenger, W.; et al. Structures of the Common Cyclodextrins and Their Larger AnaloguesBeyond the Doughnut. Chemical Reviews 1998, 98, 1787–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansook, P.; Ogawa, N.; Loftsson, T. , Cyclodextrins: structure, physicochemical properties and pharmaceutical applications. Int J Pharm 2018, 535, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez-Contreras, F.; et al. Cyclodextrins in Polymer-Based Active Food Packaging: A Fresh Look at Nontoxic, Biodegradable, and Sustainable Technology Trends. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereva, S.; et al. Water inside beta-cyclodextrin cavity: amount, stability and mechanism of binding. Beilstein J Org Chem 2019, 15, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, Q.-X. , The Driving Forces in the Inclusion Complexation of Cyclodextrins. Journal of inclusion phenomena and macrocyclic chemistry 2002, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Brewster, M.E. , Pharmaceutical applications of cyclodextrins. 1. Drug solubilization and stabilization. (0022-3549 (Print)).

- He, Y.; et al. Cyclodextrin-based aggregates and characterization by microscopy. Micron 2008, 39, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muankaew, C.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrin-Based Formulations: A Non-Invasive Platform for Targeted Drug Delivery. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 122, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadade, D.D.; Pekamwar, S.S. Cyclodextrin Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery and Theranostics. Adv Pharm Bull 2020, 10, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidwani, B.; Vyas, A. A Comprehensive Review on Cyclodextrin-Based Carriers for Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Cytotoxic Anticancer Drugs. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, I.C.; et al. Safety assessment of gamma-cyclodextrin. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2004, 39 (Suppl. 1), S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saokham, P.; Loftsson, T. gamma-Cyclodextrin. Int J Pharm 2017, 516, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cid-Samamed, A.; et al. Cyclodextrins inclusion complex: Preparation methods, analytical techniques and food industry applications. Food Chemistry 2022, 384, 132467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, S.B.; et al. Cyclodextrin(-)Drug Inclusion Complexes: In Vivo and In Vitro Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matencio, A.; et al. Applications of cyclodextrins in food science. A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 104, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ommen, B.; De Bie, A.T.; Bar, A. Disposition of 14C-alpha-cyclodextrin in germ-free and conventional rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2004, 39 (Suppl. 1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, V.J.; He, Q. Cyclodextrins. Toxicologic Pathology 2008, 36, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, A.; et al. Re-evaluation of β-cyclodextrin (E 459) as a food additive. EFSA Journal 2016, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Giancarlo, C.; et al. Cyclodextrins as Food Additives and in Food Processing. Current Nutrition & Food Science 2006, 2, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; et al. Metal-Organic Framework Based on alpha-Cyclodextrin Gives High Ethylene Gas Adsorption Capacity and Storage Stability. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 34095–34104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Enhancement of the Stabilities and Intracellular Antioxidant Activities of Lavender Essential Oil by Metal-Organic Frameworks Based on β-Cyclodextrin and Potassium Cation. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences 2021, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, R.A.; et al. Metal–Organic Frameworks from Edible Natural Products. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2010, 49, 8630–8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; et al. Cyclodextrin metal-organic framework by ultrasound-assisted rapid synthesis for caffeic acid loading and antibacterial application. Ultrason Sonochem 2022, 86, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, A.; et al. Multifunctional Ordered Bio-Based Mesoporous Framework from Edible Compounds. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy 2018, 12, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; et al. Encapsulation of catechin into nano-cyclodextrin-metal-organic frameworks: Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of storage stability and bioavailability. Food Chemistry 2022, 394, 133553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Improvement of the stabilities and antioxidant activities of polyphenols from the leaves of Chinese star anise (Illicium verum Hook. f.) using beta-cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; et al. Covering soy polysaccharides gel on the surface of β-cyclodextrin-based metal–organic frameworks. Journal of Materials Science 2020, 56, 3049–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; et al. Controlled Release of Thymol by Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Frameworks for Preservation of Cherry Tomatoes. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; et al. Encapsulation of menthol into cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks: Preparation, structure characterization and evaluation of complexing capacity. Food Chem 2021, 338, 127839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Z.; et al. Encapsulation of curcumin in cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks: Dissociation of loaded CD-MOFs enhances stability of curcumin. Food Chem 2016, 212, 485–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Ethanol-mediated synthesis of gamma-cyclodextrin-based metal-organic framework as edible microcarrier: performance and mechanism. Food Chem 2023, 418, 136000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; et al. Preparation technology and preservation mechanism of gamma-CD-MOFs biaological packaging film loaded with curcumin. Food Chem 2023, 420, 136142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, J.; et al. Fabrication of gamma-cyclodextrin-Based metal-organic frameworks as a carrier of cinnamaldehyde and its application in fresh-cut cantaloupes. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. Synthesis of γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic framework as ethylene absorber for improving postharvest quality of kiwi fruit. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 136, 108294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; et al. Characterization and Mechanisms of Novel Emulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels Stabilized by Edible Cyclodextrin-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks and Glycyrrhizic Acid. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Cyclodextrin-based metal–organic framework nanoparticles as superior carriers for curcumin: Study of encapsulation mechanism, solubility, release kinetics, and antioxidative stability. Food Chemistry 2022, 383, 132605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, S.; et al. Synthesis of nanoporous carbohydrate metal-organic framework and encapsulation of acetaldehyde. Journal of Crystal Growth 2016, 451, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; et al. Enhanced stability of anthocyanins by cyclodextrin–metal organic frameworks: Encapsulation mechanism and application as protecting agent for grape preservation. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 326, 121645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Novel γ-cyclodextrin-metal–organic frameworks for encapsulation of curcumin with improved loading capacity, physicochemical stability and controlled release properties. Food Chemistry 2021, 347, 128978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; et al. Green Synthesis of Cyclodextrin-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks through the Seed-Mediated Method for the Encapsulation of Hydrophobic Molecules. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2018, 66, 4244–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; et al. Development of nanoscale bioactive delivery systems using sonication: Glycyrrhizic acid-loaded cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 553, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szente, L. and E. Fenyvesi, Cyclodextrin-Enabled Polymer Composites for Packaging (dagger). Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; et al. Multifunctional β-Cyclodextrin MOF-Derived Porous Carbon as Efficient Herbicides Adsorbent and Potassium Fertilizer. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 14479–14489. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, V.; et al. Encapsulation of a Volatile Biomolecule (Hexanal) in Cyclodextrin Metal–Organic Frameworks for Slow Release and Its Effect on Preservation of Mangoes. ACS Food Science & Technology 2021, 1, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; et al. Development and characterization of zein-based active packaging films containing catechin loaded β-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Enhanced preservation effects of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) essential oil on the processing of Chinese bacon (preserved meat products) by beta cyclodextrin metal organic frameworks (beta-CD-MOFs). Meat Sci 2023, 195, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez-zoubi, A.; et al. Encapsulation of Origanum compactum Essential Oil in Beta-Cyclodextrin Metal Organic Frameworks: Characterization, Optimization, and Antioxidant Activity. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2023, 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; et al. Application of beta-Cyclodextrin metal-organic framework/titanium dioxide hybrid nanocomposite as dispersive solid-phase extraction adsorbent to organochlorine pesticide residues in honey samples. J Chromatogr A 2022, 1663, 462750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; et al. Food packaging for ripening and preserving banana based on ethylene-loaded nanofiber films deposited with nanosized cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks and TiO2 nanoparticles. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; et al. Highly efficient anchoring of γ-cyclodextrin-MOFs on chitosan/cellulose film by in situ growth to enhance encapsulation and controlled release of carvacrol. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 150, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. A functional Pickering emulsion coating based on octadecenylsuccinic anhydride modified γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks for food preservation. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 150, 109668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Enhanced stability and biocompatibility of HIPEs stabilized by cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks with inclusion of resveratrol and soy protein isolate for β-carotene delivery. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 274, 133431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; et al. Enhanced stability of vitamin A palmitate microencapsulated by gamma-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. J Microencapsul 2018, 35, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, G.; et al. Essential oil–cyclodextrin complexes: an updated review. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry 2017, 89, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; et al. Green synthesis of β-cyclodextrin metal–organic frameworks and the adsorption of quercetin and emodin. Polyhedron 2019, 159, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, H.R.; et al. Physiochemical characterization of metal organic framework materials: A mini review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; et al. Effect of potassium salts on the structure of gamma-cyclodextrin MOF and the encapsulation properties with thymol. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 6387–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, J.; et al. Raman spectroscopy, an ideal tool for studying the physical properties and applications of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Chemical Society Reviews 2023, 52, 3397–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; et al. Synergistic antioxidant activity and anticancer effect of green tea catechin stabilized on nanoscale cyclodextrin-based metal–organic frameworks. Journal of Materials Science 2019, 54, 10420–10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

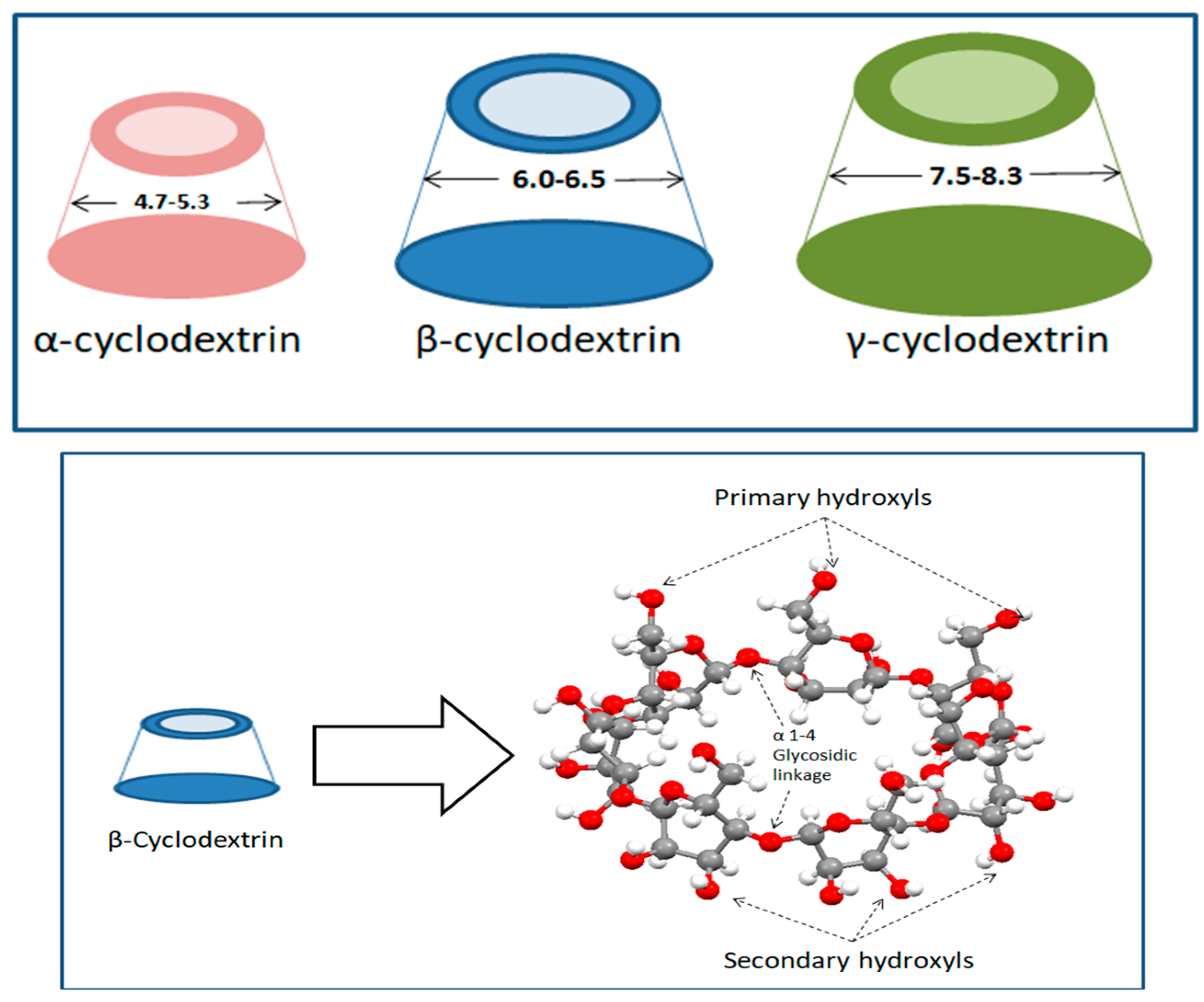

| Properties | α-CD | β-CD | γ-CD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of glucose units | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 972 | 1135 | 1297 |

| Solubility in water at 25 ◦C (%, w/v) | 14.5 | 1.9 | 23.2 |

| Melting point (◦C) | 275 | 280 | 275 |

| Cavity diameter (Å) | 4.7–5.3 | 6.0–6.5 | 7.5–8.3 |

| External diameter (Å) | 14.6 | 15.4 | 17.5 |

| Crystal forms (from water) | Hexagonal plates | Monoclinic parallelograms | Quadratic prisms |

| European trade name as food additives | E-457 | E-459 | E-458 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).