Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

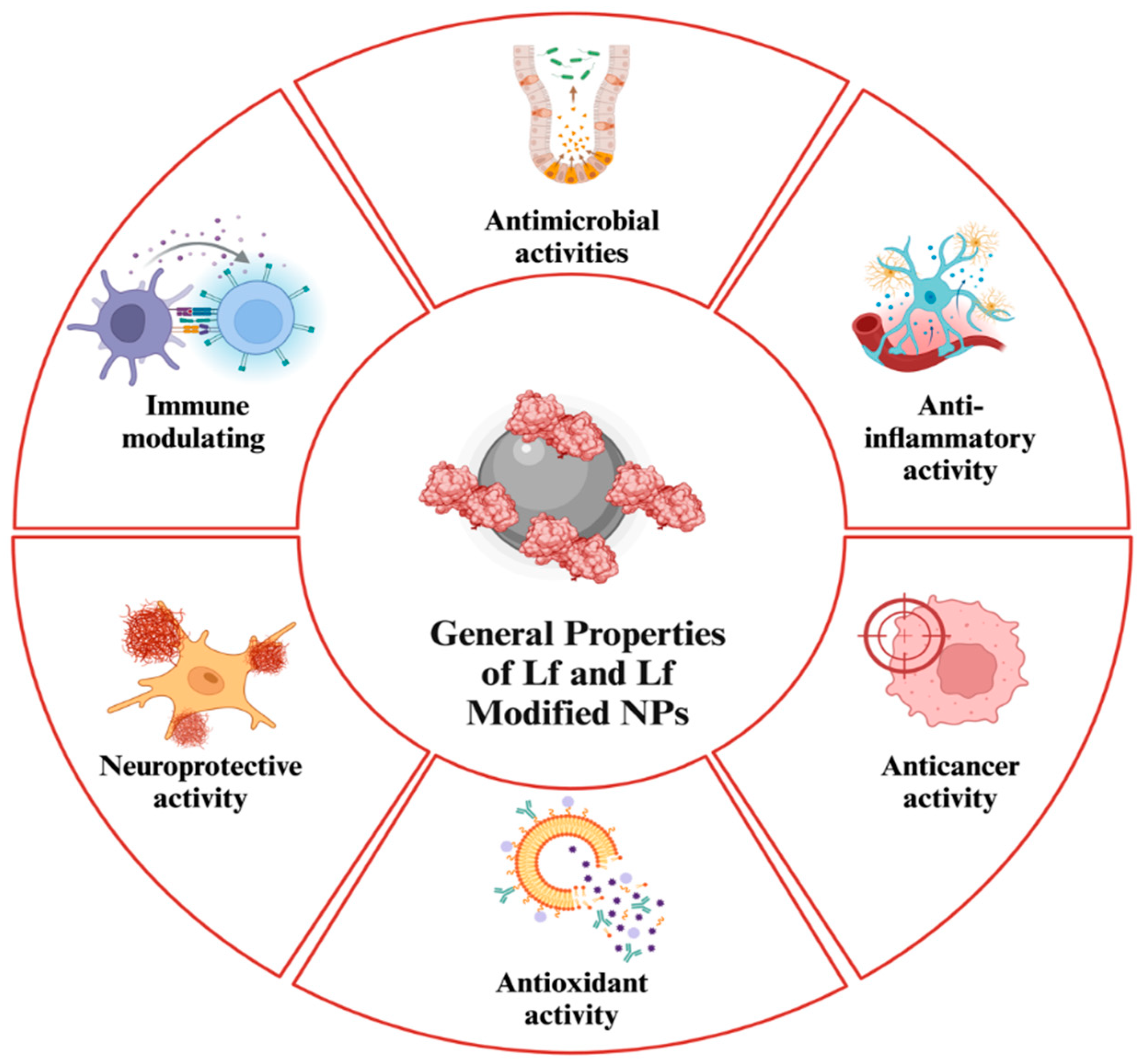

1. Introduction

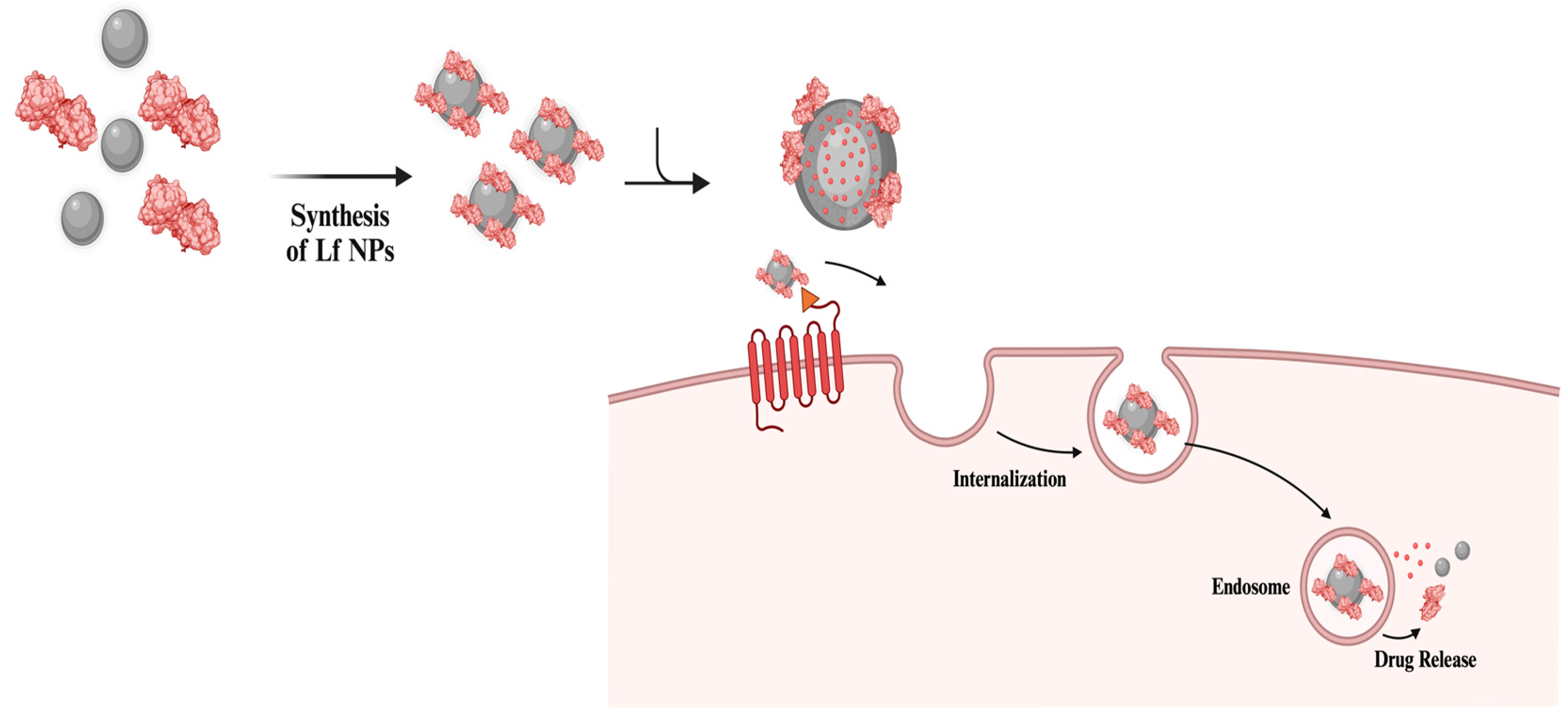

2. Lf-Coating and Lf NPs in Delivery Applications

| Application | Study Type | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deliveries With Lf NPs | |||

| Targeted lung delivery of antibiotic with Lf-included nanocomplex | In vivo In vitro |

-Sustained drug release profile. -Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 0.5 μg/mL against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. -100% bacterial reduction and zone of inhibition (ZOI) by 29 ± 1.45 mm at the highest concentration (5 μg/mL). -Bacterial reduction in kidneys of infected mice treated with dual drug-loaded PEX, with counts dropping to 3.24 ± 0.067 log₁₀ CFU/mL, compared to 18.22 ± 0.194 log₁₀ CFU/mL in untreated mice. -Insignificant activity at the lowest concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 μg/mL). -Significant inhibition of bacterial accumulation (6-fold reduction) in kidney and lung tissue of mice. -Reduced oxidative stress in mice, with PEX increasing glutathione (GSH) and catalase (CAT) levels while decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. -Improved antioxidant parameters and maintained the body weight of mice during the infection. -Improved hemocompatibility with minimal toxicity to hepatic and renal functions |

[40] |

| Delivery of antibiotics and natural compounds with Lf NPs | In vitro | -Increased uptake of drug-loaded Lf NPs, up to 90%, by THP-1 cells, surpassing that of free Lf. -Complete inhibition of Staphylococcus Aureus (S. aureus) strain Newman, at concentrations of 25 and 50 μg/mL. -Retained stability of Lf NPs following storage for over 30 days at 4 °C. |

[41] |

| Curcumin-loaded Lf NPs for ulcerative colitis treatment | In vivo In vitro |

-Improvement of the loading efficiency of curcumin, up to 95.08%, following incorporation of Lf in the nanosystem. -Increased tight junction protein expression (ZO-1, Occludin, Claudin-1) levels in colon tissues by Lf-included nanosystem, compared to the free curcumin and curcumin-NP groups. -Suppression of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB protein levels in colon tissues of UC mice treated with the Lf-included nanosystem. -Restoration of microbial flora diversity, with increased Bacteroidetes and decreased Firmicutes, following treatment with the Lf-included nanosystem in UC mice. |

[42] |

| Microencapsulated Lf NPs for docetaxel and atorvastatin delivery in the oral treatment of colorectal cancer | In vivo In vitro |

-Effective internalization of drug-loaded Lf NPs by Caco-2 cells along with lower half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values compared to free drug samples. -Sustained release of NPs in rat cecal content without degradations observed in the upper gastrointestinal tract. -Suppression of p-AKT, p-ERK1/2, and NF-κB levels and activation of caspase enzymes |

[43] |

| Production of Lf NP encapsulated gold complexes, (Lf-C2), to cross blood-brain barrier (BBB) in glioma treatment | In vivo In vitro |

-Successful crossing of the BBB by Lf-C2 NPs compared to C2 alone. -Increased inhibition rates on glioma growth with Lf-C2 NPs (68.6%), compared to the free C2 (21.6%). -Achievement of higher, 88.2%, apoptosis rate in LF-C2 NP-treated tumor tissues compared to 21.2% and 6.9% for C2 and NaCl, respectively. |

[44] |

| Production of zein-glycosylated Lf NPs for improved stability and bioaccessibility of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF) | In vitro | -High encapsulation efficiency (above 98.50%) with zein-glycosylated Lf NPs. -Improved bioaccessibility with the existence of Lf, reaching up to a maximum of 84.05%, while free 7,8-DHF achieved only 18.06%. -Increased retention percentage with the addition of Lf, rising from 12.35% to 43.21% under dark conditions at 50°C. -Enhanced stability over 30 days of storage compared to zein NPs alone. |

[45] |

| Fabrication of zein-Lf NPs for encapsulation of 7,8-DHF | In vitro | -Approximately 30 times higher water solubility with zein-Lf NPs (231.60 μg/mL) than that of 7,8-DHF alone (7.12 μg/mL). -Improved bioaccessibility with zein-Lf NPs (63.51%) in comparison to free 7,8-DHF, (18.06%) and zein-DHF (31.85%). -Enhanced chemical stability with zein/LF NPs, retaining 27.4% of 7,8-DHF, while free 7,8-DHF was nearly degraded after 15 days at 25 °C under light. |

[46] |

| Development of disulfiram-loaded Lf NPs (DSF-LF-NPs) for the treatment of inflammatory diseases | In vitro In vivo |

-Protection against LPS-induced sepsis in mice. -Protection against DSS-induced colitis supported by improved disease activity index (DAI), reduced body weight loss, preserved colon length, and minimized epithelial damage and inflammatory cell infiltration. -Reliable safety profile that enables further use. |

[47] |

| NP Modification With Lf | |||

| Anticancer Reserach | |||

| Production of Lf-coated mesoporous maghemite NPs for the delivery of anticancer drug Doxorubicin. | In vivo In vitro |

-Improved inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and targeted delivery into desired areas. -Enhanced toxicity towards breast cancer cells with Lf-Doxo-MMNPs, supported by IC50 value of 20 μg/mL. -Increased tumor growth inhibition (TGI) in mice treated with Lf-Doxo-MMNPs compared to formulations without Lf and Doxo alone. -Increased TNF-α, Fas, Bax, and caspase-3 expression levels with Lf-Doxo-MMNPs at a concentration of 20 μg/mL. |

[48] |

| Synthesis of mesoporous silica NPs, coated with Lf shell, for breast cancer therapy | In vitro | -Highest cytotoxicity towards MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines, supported by the lowest combination index (CI) of 0.885 in comparison to free drugs. -Improved cellular uptake of NPs to MCF-7 cells with formulations containing Lf as a targeting ligand. |

[49] |

| Development of Lf-containing nanosystem to mitigate Doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity | In vitro In vivo |

-Prevention of gastric degradation following Lf included double coating. -Alleviation of doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxic effects along with maintenance of body weight in mice models. |

[50] |

| Brain Targeted Deliveries | |||

| Lf-functionalized resveratrol-loaded cerium dioxide NPs (LMC-RES) with neuroprotective activity against Alzheimer’s Disease | In vivo In vitro |

-Successful penetration into BBB, leading to neuronal protection. -Sustained release of resveratrol with high biocompatibility. -Improved drug release rate with LMC-RES, reaching up to 80.9 ± 2.25% after 24 hours. -Inhibition of oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells through the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. |

[51] |

| Development of Lf-modified berberine nanoliposomes (BR-Lf) against Alzheimer’s Disease | In vivo In vitro |

-High entrapment efficiency following Lf modification -Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and apoptosis in the hippocampus. -Significant improvement in spontaneous alternation behavior in the BR-Lf group of mice. -Inhibition of tau-over phosphorylation in the cerebral cortex. |

[52] |

| Synthesis of Lf included polymeric nanocarriers (F-PMBN-Lf) for the delivery of frankincense against Alzheimer’s Disease | In vivo In vitro |

-Inhibition of scopolamine-induced increases in AChE and GSH. -Sustained release of frankincense by the incorporation of Lf, with a release rate of 18.2% after 48 hours. -Alleviation of depression and stress by F-PMBN-Lf. -Improvements in short-term memory. |

[53] |

| Other Deliveries | |||

| Lf-decorated nanoconjugates for targeted curcumin delivery | In vitro | -Controlled release of 78.12% of curcumin under acidic conditions (pH 5.8). -Increased anticancer effects through functionalization with Lf, supported by cell viability results ranging from 98.02 ± 1.19% to 94.23 ± 1.45%. -Improvement in bioavailability following Lf coating. |

[54] |

| Development of Lf-modified ternary NPs for the delivery of curcumin | In vitro | -Increased cellular uptake of curcumin up to 89.5% after 12 hours of treatment, compared to sole curcumin treatment at 61.9%. -Improvement in bioaccessibility of curcumin through encapsulation, from 22.1% to 53.6%. -Increased anticancer effects on HT-29 and CT-26 cells in a dose-dependent manner. |

[55] |

| Development of Lf-bearing gold nanocages as gene delivery systems against prostate cancer | In vitro | -Increased gene expression levels with the incorporation of Lf into nanoconjugate, evidenced by a 1.71-fold increase compared to conditions without Lf. -Increased DNA cellular uptake (reaching up to 8.65-fold) compared to naked DNA. |

[56] |

| Lf-decorated nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) for leukemia treatment | In vivo In vitro Ex vivo |

-Increased stability of NLCs over 120-day period with negligible changes in particle size -Antileukemic cytotoxicity and induction of apoptosis in K562 cells. -Increased cellular uptake by K562 cells following Lf coating. -Enhanced cytotoxic effects with Lf coating, with an IC50 value of 19.81 ± 1.01 μg/mL, compared to uncoated particles, at 35.01 ± 2.23 μg/mL. |

[57] |

| Development of curcumin-loaded Lf nanohydrogels against food stimulants | In vitro | -Improvement in stability; up to 35 days for storage at 4°C and 14 days for storage at 25°C. -Increased release rates of curcumin from Lf nanohydrogels in lipophilic compounds compared to hydrophilic ones. -Successful incorporation into a gelatin matrix without degradation over 7 days of storage. |

[58] |

| Lf Delivery With NPs | |||

| Liposomal-Lf Based Eye Drops | In vivo (Clinical Trial) | -Reduction in the proportion of potentially pathogenic bacteria, from 36% pre-treatment to 9% post-treatment. -Reliable safety profile with no adverse effects reported. -Higher chance of maintaining the saprophytic flora with eyes treated with Lf. |

[59] |

| Liposomal Lf Delivery For Dry Eye Disease | In vitro In vivo |

-Maintained stability over 60 days at both 4 °C and 25 °C. -Sustained release of Lf from liposomes, reaching 71.44% over 72 hours. -No signs of toxicity against HCE-2 cells, with cell viability remaining above 80%. -Increased aqueous tear secretion in the Lf-treated group, showing a 6.25-fold increase after 5 days compared to baseline and a 4.5-fold increase over the saline-treated group. |

[60] |

| Synthesis of Lf-loaded Chitosan NPs to alleviate oxidative damage in rats | -Suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation after treatment with Lf-containing nanocomplex. -Achieved approximately 58% loading capacity and 88% encapsulation efficiency. -Significant reduction in hepatic MDA and nitric oxide (NO) levels, along with increased GSH and antioxidant enzyme activities (GPx, CAT, GST). -Reduced caspase-3 immunoreactivity in the Lf-treated group, compared to the control group. |

[61] | |

| Development of Lf-incorporated mesoporous glass scaffolds to enhance osteoblastic cell cultures | In vitro | -High biocompatibility, achieved through the integration of Lf, supporting cell proliferation. -Enhanced biomineralization and osteoblast proliferation following incorporation of Lf. -Increased levels of ALP and Runx2, contributing to osteoblastic differentiation. |

[62] |

2.1. Drug Delivery with Lf NPs

2.2. Surface Modification of NPs with Lf for Targeted Drug Delivery in Anticancer and Neurological Applications

- Anticancer Applications

- Targeted Brain Delivery Applications

2.3. Lf and NPs in Delivery Systems for Hepaprotective, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Applications

2.4. Lf Delivery with NPs

- Ocular Delivery of Lf with NPs

- Lf Delivery for Bone Engineering

3. Antimicrobial Applications of Lf-NPs

- Antibacterial

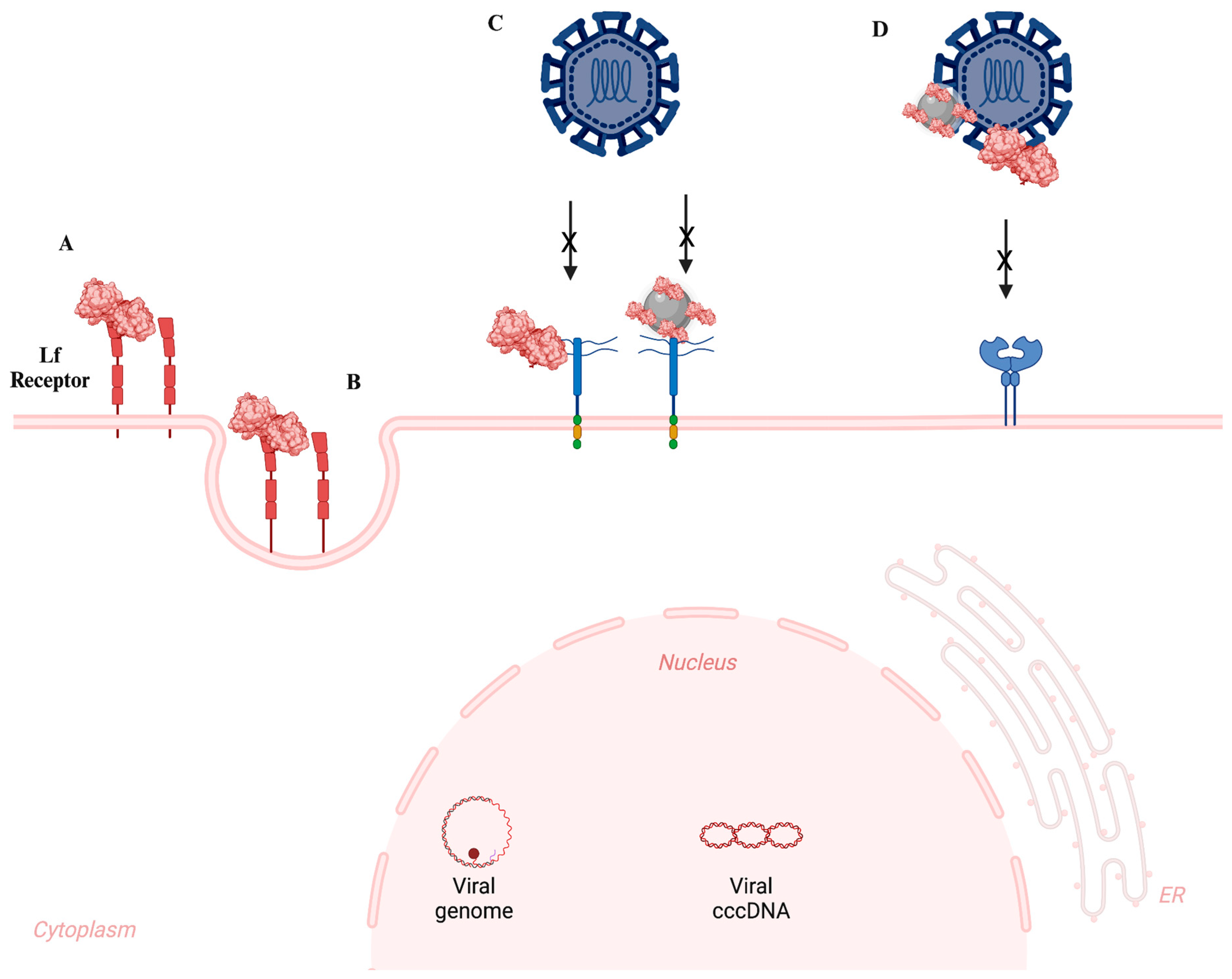

- Antiviral

- Antifungal

| Antimicrobial activity of Lf with NP | Study Type | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial | |||

| Development of Silver-Lf NP incorporated hydrogels | In vitro | -Silver-Lf NPs demonstrated antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli and P. aeruginosa) bacteria. -Largest zones of inhibition were 11.3 ± 7.5 mm, 10.3 ± 1.5 mm and 7.3 ± 0.6 mm for E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, respectively, at a NP concentration of 125 µg/mL. |

[120] |

| Development of antibiotic loaded Lf NPs | In vitro In vivo |

-NPs demonstrated bactericidal activity against E. coli, Mycobacterium marinum (MM) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). -Superior antibacterial effects, in comparison to free antibiotic and antibiotic loaded bovine serum albumin NPs, were observed. -MIC values were determined as 12.5 µg/mL for E. coli, 0.3125 µg/mL for MM, and 8.0 µg/mL for MRSA. -In vivo assays on mice model highlighted that antibiotic loaded Lf NPs can promote wound healing by improving intracellular bacteria elimination. |

[66] |

| Synthesis of Lf functionalized gold NPs | In vitro In vivo |

-Antibacterial activity against both non-pathogenic bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) and E. coli, and pathogenic strains including S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis), and S. typhi. -Enhanced antibacterial effects, through functionalization with Lf, compared to NPs alone. -Lowest MIC values were determined as 10 µg/mL and 15 µg/mL for B. subtilis and E. faecalis, respectively. -Largest zones of inhibitions were observed as 8.35 mm for E. faecalis and 8.45 mm for B. subtilis. -Increased biocompatibility and hemocompatibility in Wistar rats, following incorporation of Lf functionalized gold NPs. |

[121] |

| Development of Lf-functionalized silver NP incorporated gelatin hydrogels | In vitro | -Dose-dependent antibacterial activity of Lf-Silver NPs against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. -Increased inhibition zones, from 10.7 ± 3.6 to 12.7 ± 2.3 for S. aureus and 10.8 ± 1.4 to 11.9 ± 3.2 for P. aeruginosa, when Lf-silver NP concentration in hydrogels was increased from 62.5 μg/mL to 125 μg/mL. |

[122] |

| Preservation of strawberry samples through antibacterial Lf NPs | In vitro | -Significant antibacterial activity against S. aureus 0.3 mg/mL MIC value -Lf-NP coating on strawberries with carboxymethylcellulose reduced weight loss from 85% to 60% at day 6. -Significant reduction in counted aerobic mesophilic bacteria. -Reduced physiological changes of strawberries during storage. |

[123] |

| Lf-included Nanocomposite for Packaging | in vitro | -High antioxidant activity by 67.6 ± 1.4 % DPPH radical scavenging -Significant antibacterial activity against E.coli and S. aureus with 18.5 mm ZOI. -Increased decomposition. |

[124] |

| Antiviral | |||

| Development of Zn-NPs coated with bLf using green synthesis | In vitro | -LF-Zn-NPs contained larger particles that measured up to 98 ± 6.40 nm, whereas the biosynthesized Zn-NPs were white, oval to spherical in form, and had an average size of 77 ± 5.50 nm. -The negatively charged surfaces of the biosynthesized Zn-NPs and LF-Zn-NPs were found to have zeta-potentials of -20.25 ± 0.35 and -44.3 ± 3.25 mV, respectively. -By attaching to the ACE2-receptor and spike protein receptor binding domain with IC50 values of 59.66 and μg/mL, respectively, LF-Zn-NPs showed a notable in vitro delay of SARS-CoV-2 entrance to host cells. |

[117] |

| Development zidovudine + efavirenz + lamivudine loaded Lf-NPs (FLART -NP) against HIV therapy | In vivo In vitro |

-Encapsulation efficiency, cellular localization, release kinetics, safety analysis, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics have all been investigated in vitro and in vivo. -For each medication, FLART-NP was produced with an encapsulation effectiveness of >58% and a mean diameter of 67 nm (FE-SEM). -With little burst release, low erythrocyte damage, and enhanced anti-HIV effectiveness in in vitro experiments, FLART-NP delivers the maximal payload at pH5. |

[116] |

| Development Coencapsulated Lf-NPs with tenofovir and curcumin enhance vaginal protection against HIV-1 infection. | In vitro In vivo |

TCNPs | [115] |

| Antifungal | |||

| Development nanofiber membranes loaded with bLf to display antifungal activity against Aspergillus nidulans | In vitro | -The membranes had an overall porosity of around 80% and smooth, nondefective fibers with mean diameters ranging from 717 ± 197 to 495 ± 127 nm. -The presence of bLf decreases the hydrophobicity of the PLLA membranes. -Human fibroblasts were not cytotoxically affected by the bLf–PLLA membranes that were created; interestingly, after 24 hours of indirect contact, the 20-weight percent bLf–PLLA membrane was even capable of inducing cell growth. |

[100] |

| In vitro | -PMLs have been produced with gold NPs and manganese ferrite, functionalized with either octadecanethiol or 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid, and then loaded with bLf. -PMLs were formed when both plasmonic and magnetic NPs were enclosed in DPPC and Egg-PC liposomes. -PMLs loaded with bLf are around 200 nm in size, exhibit a positive zeta potential, and remain stable for at least five days. -Because PMLs are non-cytotoxic and retain their antifungal function, they exhibit encouraging potential for delivering bLf into yeast cells. |

[119] | |

4. Agriculture Applications of Lf-NPs

4.1. Food Packaging

4.2. Food Preservation

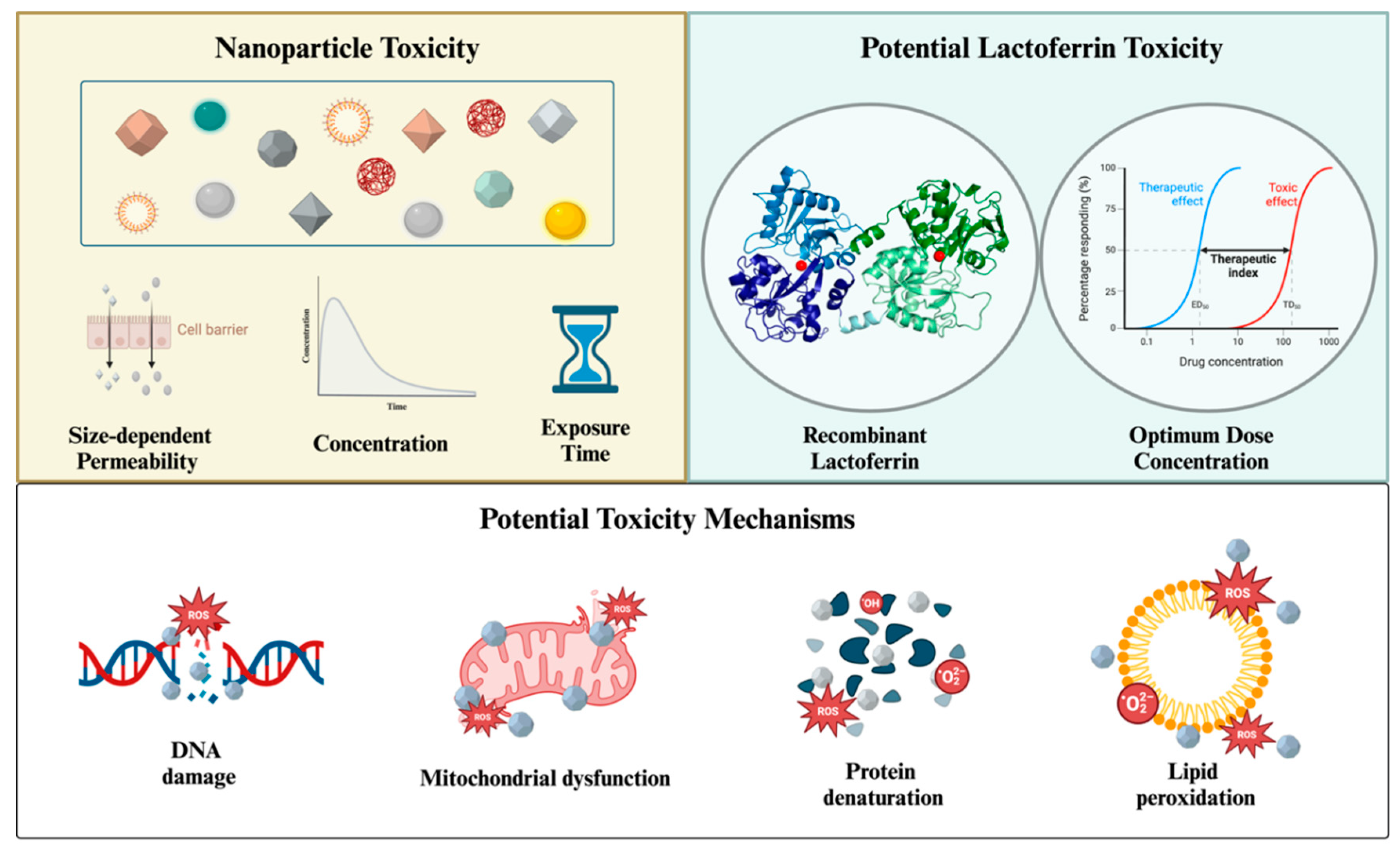

5. Toxicity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Montoya, I.A.; Cendón, T.S.; Arévalo-Gallegos, S.; Rascón-Cruz, Q. Lactoferrin a Multiple Bioactive Protein: An Overview. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2012, 1820, 226–236. [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.N.; Baker, H.M. Molecular Structure, Binding Properties and Dynamics of Lactoferrin. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2005, 62, 2531–2539. [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.M.; Baker, E.N. Lactoferrin and Iron: Structural and Dynamic Aspects of Binding and Release. BioMetals 2004, 17, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Bolat, E.; Pekdemir, B.; Duman, H.; Karav, S. Lactoferrin: Neuroprotection against Parkinson’s Disease and Secondary Molecule for Potential Treatment. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15, 1204149. [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, C.; Berselli, E.; Blanco-Llamero, C.; Fathi, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Krambeck, K.; Souto, E.B. Biomedical and Nutritional Applications of Lactoferrin. Int J Pept Res Ther 2023, 29, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.J.; Veerakumarasivam, A.; Lim, W.L.; Chew, J. Neuroprotective Effects of Lactoferrin in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases: A Narrative Review. ACS Chem Neurosci 2022. [CrossRef]

- Karav, S.; German, J.B.; Rouquié, C.; Le Parc, A.; Barile, D. Studying Lactoferrin N-Glycosylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, Vol. 18, Page 870 2017, 18, 870. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ren, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.S.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z. Lactoferrin: A Glycoprotein That Plays an Active Role in Human Health. Front Nutr 2023, 9, 1018336. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B.; Heyden, E.L.; Pretorius, E. The Biology of Lactoferrin, an Iron-Binding Protein That Can Help Defend Against Viruses and Bacteria. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 550441. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Ertürk, M.; Karav, S. The Potential of Lactoferrin as Antiviral and Immune-Modulating Agent in Viral Infectious Diseases. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1402135. [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Eker, F.; Kaplan, M.; Duman, H.; Arslan, A.; Saritaş, S.; Şahutoğlu, A.S.; Karav, S. Lactoferrin for COVID-19 Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 992733. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Baktıroğlu, M.; Kalkan, A.E.; Canbolat, A.A.; Lombardo, M.; Raposo, A.; de Brito Alves, J.L.; Witkowska, A.M.; Karav, S. Lactoferrin: A Promising Therapeutic Molecule against Human Papillomavirus. Nutrients 2024, Vol. 16, Page 3073 2024, 16, 3073. [CrossRef]

- Jose-Abrego, A.; Rivera-Iñiguez, I.; Torres-Reyes, L.A.; Roman, S. Anti-Hepatitis B Virus Activity of Food Nutrients and Potential Mechanisms of Action. Ann Hepatol 2023, 28, 100766. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, R.; Rosa, L.; Cutone, A.; Lepanto, M.S.; Franchitto, A.; Onori, P.; Gaudio, E.; Valenti, P. Viral Hepatitis and Iron Dysregulation: Molecular Pathways and the Role of Lactoferrin. Molecules 2020, Vol. 25, Page 1997 2020, 25, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Fan, Y.C.; Lin, J.W.; Chen, Y.Y.; Hsu, W.L.; Chiou, S.S. Bovine Lactoferrin Inhibits Dengue Virus Infectivity by Interacting with Heparan Sulfate, Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor, and DC-SIGN. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, Vol. 18, Page 1957 2017, 18, 1957. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.E.; Carter, D.A. The Antifungal Activity of Lactoferrin and Its Derived Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Synergy with Drugs against Fungal Pathogens. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 238609. [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.M.; Soetedjo, R.; Tandarto, K.; Arieselia, Z.; Regina, R. Bovine Lactoferrin and Current Antifungal Therapy Against Candida Albicans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J Dermatol 2024, 68, 725. [CrossRef]

- Gruden, Š.; Poklar Ulrih, N. Diverse Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Activities of Lactoferrins, Lactoferricins, and Other Lactoferrin-Derived Peptides. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11264. [CrossRef]

- Biasibetti, E.; Rapacioli, S.; Bruni, N.; Martello, E. Lactoferrin-Derived Peptides Antimicrobial Activity: An in Vitro Experiment. Nat Prod Res 2021, 35, 6073–6077. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, C.P.J.M.; Theelen, B.; van der Linden, Y.; Sarink, N.; Rahman, M.; Alwasel, S.; Cafarchia, C.; Welling, M.M.; Boekhout, T. Combinatory Use of HLF(1-11), a Synthetic Peptide Derived from Human Lactoferrin, and Fluconazole/Amphotericin B against Malassezia Furfur Reveals a Synergistic/Additive Antifungal Effect. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ostrówka, M.; Duda-Madej, A.; Pietluch, F.; Mackiewicz, P.; Gagat, P. Testing Antimicrobial Properties of Human Lactoferrin-Derived Fragments. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Ohradanova-Repic, A.; Praženicová, R.; Gebetsberger, L.; Moskalets, T.; Skrabana, R.; Cehlar, O.; Tajti, G.; Stockinger, H.; Leksa, V. Time to Kill and Time to Heal: The Multifaceted Role of Lactoferrin and Lactoferricin in Host Defense. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1056 2023, 15, 1056. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.F.; Zubair, D.; Bashir, M.N.; Alagawany, M.; Ahmed, S.; Shah, Q.A.; Buzdar, J.A.; Arain, M.A. Nutraceutical and Health-Promoting Potential of Lactoferrin, an Iron-Binding Protein in Human and Animal: Current Knowledge. Biological Trace Element Research 2023 202:1 2023, 202, 56–72. [CrossRef]

- Conesa, C.; Bellés, A.; Grasa, L.; Sánchez, L. The Role of Lactoferrin in Intestinal Health. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1569 2023, 15, 1569. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, H.; Nangare, S.; Khan, Z.; Patil, A.; Bari, S.; Patil, P. Design of Lactoferrin Functionalized Carboxymethyl Dextran Coated Egg Albumin Nanoconjugate for Targeted Delivery of Capsaicin: Spectroscopic and Cytotoxicity Studies. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 256. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.M.; Taha, N.M.; Lebda, M.A.; Elfeky, M.S.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.R. Effects of Bovine Lactoferrin and Chitosan Nanoparticles on Serum Biochemical Indices, Antioxidative Enzymes, Transcriptomic Responses, and Resistance of Nile Tilapia against Aeromonas Hydrophila. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2021, 111, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- Aslam Saifi, M.; Hirawat, R.; Godugu, C. Lactoferrin-Decorated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Prevent Renal Injury and Fibrosis. Biol Trace Elem Res 2023, 201, 1837–1845. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticles: From Classification to Application and Toxicity. Molecules 2024, Vol. 29, Page 3482 2024, 29, 3482. [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkesh, I.; Sheremet, M.; Yang, L.; Heris, S.Z.; Sharifpur, M.; Meyer, J.P.; Ghalambaz, M.; Wongwises, S.; Jing, D.; Mahian, O. Effect of Nanoparticle Shape on the Performance of Thermal Systems Utilizing Nanofluids: A Critical Review. J Mol Liq 2021, 321, 114430. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gaus, K.; Tilley, R.D.; Gooding, J.J. The Impact of Nanoparticle Shape on Cellular Internalisation and Transport: What Do the Different Analysis Methods Tell Us? Mater Horiz 2019, 6, 1538–1547. [CrossRef]

- Punia, P.; Bharti, M.K.; Chalia, S.; Dhar, R.; Ravelo, B.; Thakur, P.; Thakur, A. Recent Advances in Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Nanoparticles for Contaminated Water Treatment- A Review. Ceram Int 2021, 47, 1526–1550. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, C.; Roy, A.; Ghotekar, S.; Khusro, A.; Islam, M.N.; Emran, T. Bin; Lam, S.E.; Khandaker, M.U.; Bradley, D.A. Biological Agents for Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Applications. J King Saud Univ Sci 2022, 34, 101869. [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, I.; Gilani, E.; Nazir, A.; Bukhari, A. Detail Review on Chemical, Physical and Green Synthesis, Classification, Characterizations and Applications of Nanoparticles. Green Chem Lett Rev 2020, 13, 59–81. [CrossRef]

- Aghebati-Maleki, A.; Dolati, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Baghbanzhadeh, A.; Asadi, M.; Fotouhi, A.; Yousefi, M.; Aghebati-Maleki, L. Nanoparticles and Cancer Therapy: Perspectives for Application of Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Cancers. J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, 1962–1972. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shah, T.; Ullah, R.; Zhou, P.; Guo, M.; Ovais, M.; Tan, Z.; Rui, Y.K. Review on Recent Progress in Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Diverse Applications. Front Chem 2021, 9, 629054. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Duman, H.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Gold Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine: Unique Properties and Therapeutic Potential. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1854. [CrossRef]

- Mofidian, R.; Barati, A.; Jahanshahi, M.; Shahavi, M.H. Optimization on Thermal Treatment Synthesis of Lactoferrin Nanoparticles via Taguchi Design Method. SN Appl Sci 2019, 1, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Liu, H.; Lv, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Z. Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro/Vivo Studies of Oleanolic Acid-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 1417–1427. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Lakshmi, Y.S.; Kondapi, A.K. An Oral Formulation of Efavirenz-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles with Improved Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetic Profile. HIV Med 2017, 18, 452–462. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Mahmoud, H.E.; Embaby, A.M.; Haroun, M.; Sabra, S.A. Lactoferrin/Pectin Nanocomplex Encapsulating Ciprofloxacin and Naringin as a Lung Targeting Antibacterial Nanoplatform with Oxidative Stress Alleviating Effect. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 261, 129842. [CrossRef]

- Andima, M.; Boese, A.; Paul, P.; Koch, M.; Loretz, B.; Lehr, C.M. Targeting Intracellular Bacteria with Dual Drug-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles. ACS Infect Dis 2024, 10, 1696–1710. [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Zhao, P.; Ayue, S.; Qi, S.; Ye, Y.; He, H.; Dai, L.; Luo, R.; Chang, D.; Gao, F. Folic Acid-Modified Lactoferrin Nanoparticles Coated with a Laminarin Layer Loaded Curcumin with Dual-Targeting for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 232, 123229. [CrossRef]

- Elmorshedy, Y.M.; Teleb, M.; Sallam, M.A.; Elkhodairy, K.A.; Bahey-El-Din, M.; Ghareeb, D.A.; Abdulmalek, S.A.; Abdel Monaim, S.A.H.; Bekhit, A.A.; Elzoghby, A.O.; et al. Engineered Microencapsulated Lactoferrin Nanoconjugates for Oral Targeted Treatment of Colon Cancer. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2149–2163. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fang, R.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, J. Encapsulation of Au(III) Complex Using Lactoferrin Nanoparticles to Combat Glioma. Mol Pharm 2023, 20, 3632–3644. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, S.; Cai, Q.; Wu, L.; Sun, Y.; Xia, G.; Wang, Y. Establishment and Characterization of Stable Zein/Glycosylated Lactoferrin Nanoparticles to Enhance the Storage Stability and in Vitro Bioaccessibility of 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone. Front Nutr 2022, 8, 806623. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, G.; Xue, F.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y. Fabrication and Characterization of Zein/Lactoferrin Composite Nanoparticles for Encapsulating 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone: Enhancement of Stability, Water Solubility and Bioaccessibility. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 146, 179–192. [CrossRef]

- Ou, A. te; Zhang, J. xin; Fang, Y. fei; Wang, R.; Tang, X. ping; Zhao, P. fei; Zhao, Y. ge; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y. zhuo Disulfiram-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles for Treating Inflammatory Diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 1913–1920. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Sharifi, M.; Jafari, S.; Hasan, A.; Hasan, A.; Paray, B.A.; Gong, G.; Zheng, Y.; Falahati, M. Antimetastatic Activity of Lactoferrin-Coated Mesoporous Maghemite Nanoparticles in Breast Cancer Enabled by Combination Therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2020, 6, 3574–3584. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.M.; Bekhit, A.A.; Khattab, S.N.; Helmy, M.W.; Abdel-Ghany, Y.S.; Teleb, M.; Elzoghby, A.O. Synthesis of Lactoferrin Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Pemetrexed/Ellagic Acid Synergistic Breast Cancer Therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110824. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Helmy, M.W.; Mahmoud, H.E.; Embaby, A.M.; Haroun, M.; Sabra, S.A. Cinnamaldehyde /Naringin Co-Loaded into Lactoferrin/ Casienate-Coated Zein Nanoparticles as a Gastric Resistance Oral Carrier for Mitigating Doxorubicin-Induced Hepatotoxicity. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 96, 105688. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Guo, H.; Cheng, S.; Sun, J.; Du, J.; Liu, X.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Wu, C.; et al. Functionalized Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles with Antioxidative Neuroprotection for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 6797–6812. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, B.Q.; Li, Y.H.; Jiang, Q.Q.; Cong, W.H.; Chen, K.J.; Wen, X.M.; Wu, Z.Z. Lactoferrin Modification of Berberine Nanoliposomes Enhances the Neuroprotective Effects in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen Res 2023, 18, 226–232. [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, F.; Hatamian-Zarmi, A.; Ebrahimi Hosseinzadeh, B.; Khodagholi, F.; Rooki, M.; Rashidi, F. Preparation and Characterization of Brain-Targeted Polymeric Nanocarriers (Frankincense-PMBN-Lactoferrin) and in-Vivo Evaluation on an Alzheimer’s Disease-like Rat Model Induced by Scopolamine. Brain Res 2024, 1822, 148622. [CrossRef]

- Nangare, S.; Ramraje, G.; Patil, P. Formulation of Lactoferrin Decorated Dextran Based Chitosan-Coated Europium Metal-Organic Framework for Targeted Delivery of Curcumin. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 259, 129325. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gu, Q.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. Lactoferrin-Based Ternary Composite Nanoparticles with Enhanced Dispersibility and Stability for Curcumin Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2023, 15, 18166–18181. [CrossRef]

- Almowalad, J.; Somani, S.; Laskar, P.; Meewan, J.; Tate, R.J.; Mullin, M.; Dufès, C. Lactoferrin-Bearing Gold Nanocages for Gene Delivery in Prostate Cancer Cells in Vitro. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 4391–4407. [CrossRef]

- Abou-Elnour, F.S.; El-Habashy, S.E.; Essawy, M.M.; Abdallah, O.Y. Alendronate/Lactoferrin-Dual Decorated Lipid Nanocarriers for Bone-Homing and Active Targeting of Ivermectin and Methyl Dihydrojasmonate for Leukemia. Biomaterials Advances 2024, 162, 213924. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.F.; Bourbon, A.I.; Simões, L.S.; Vicente, A.A.; Coutinho, P.J.G.; Ramos, O.L. Physicochemical Characterisation and Release Behaviour of Curcumin-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanohydrogels into Food Simulants. Food Funct 2020, 11, 305–317. [CrossRef]

- Giannaccare, G.; Comis, S.; Jannuzzi, V.; Camposampiero, D.; Ponzin, D.; Cambria, S.; Santocono, M.; Pallozzi Lavorante, N.; Del Noce, C.; Scorcia, V.; et al. Effect of Liposomal-Lactoferrin-Based Eye Drops on the Conjunctival Microflora of Patients Undergoing Cataract Surgery. Ophthalmol Ther 2023, 12, 1315–1326. [CrossRef]

- López-Machado, A.; Díaz-Garrido, N.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Badia, J.; Baldomà, L.; Calpena, A.C.; Souto, E.B.; García, M.L.; Sánchez-López, E. Development of Lactoferrin-Loaded Liposomes for the Management of Dry Eye Disease and Ocular Inflammation. Pharmaceutics 2021, Vol. 13, Page 1698 2021, 13, 1698. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahhab, K.G.; Ashry, M.; Hassan, L.K.; Gadelmawla, M.H.A.; Elqattan, G.M.; El-Fakharany, E.M.; Mannaaa, F.A. Nano-Chitosan/Bovine Lactoperoxidase and Lactoferrin Formulation Modulates the Hepatic Deterioration Induced by 7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]Anthracene. Comp Clin Path 2023, 32, 981–991. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rodríguez, L.I.; Pablos, J.L.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Rodríguez-Mendiola, M.A.; Arias-Castro, C.; Sánchez-Salcedo, S.; Salinas, A.J. Enhancing Osteoblastic Cell Cultures with Gelatin Methacryloyl, Bovine Lactoferrin, and Bioactive Mesoporous Glass Scaffolds Loaded with Distinct Parsley Extracts. Biomolecules 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1764 2023, 13, 1764. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Pangua, C.; Reboredo, C.; Campión, R.; Morales-Gracia, J.; Irache, J.M. Protein-Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Purposes. Int J Pharm 2020, 581, 119289. [CrossRef]

- Elzoghby, A.O.; Abdelmoneem, M.A.; Hassanin, I.A.; Abd Elwakil, M.M.; Elnaggar, M.A.; Mokhtar, S.; Fang, J.Y.; Elkhodairy, K.A. Lactoferrin, a Multi-Functional Glycoprotein: Active Therapeutic, Drug Nanocarrier & Targeting Ligand. Biomaterials 2020, 263, 120355. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Tran, P.T.T.; Truong, D.H. Lactoferrin and Nanotechnology: The Potential for Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1362. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Mo, W.; Xiao, X.; Cai, M.; Feng, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Antibiotic-Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles as a Platform for Enhanced Infection Therapy through Targeted Elimination of Intracellular Bacteria. Asian J Pharm Sci 2024, 19, 100926. [CrossRef]

- Senapathi, J.; Bommakanti, A.; Mallepalli, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kondapi, A.K. Sulfonate Modified Lactoferrin Nanoparticles as Drug Carriers with Dual Activity against HIV-1. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2020, 191, 110979. [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Lin, M.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Shi, J.; Pu, X.; Dong, L.; Xu, H.; et al. Calcium Pectinate and Hyaluronic Acid Modified Lactoferrin Nanoparticles Loaded Rhein with Dual-Targeting for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 263, 117998. [CrossRef]

- Sabra, S.; Agwa, M.M. Lactoferrin, a Unique Molecule with Diverse Therapeutical and Nanotechnological Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 164, 1046–1060. [CrossRef]

- Kondapi, A.K. Targeting Cancer with Lactoferrin Nanoparticles: Recent Advances. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 2071–2083. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X. Recent Development of Lactoferrin-Based Vehicles for the Delivery of Bioactive Compounds: Complexes, Emulsions, and Nanoparticles. Trends Food Sci Technol 2018, 79, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Nice, E.C.; Xie, N.; Huang, C.; Shen, Z. Enhancing the Therapeutic Efficacy of Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment Using Versatile Targeted Strategies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022 15:1 2022, 15, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P.; Chadar, R.; Sheikh, A.; Rizg, W.Y.; Safhi, A.Y. CD44-Targeted Nanocarrier for Cancer Therapy. Front Pharmacol 2022, 12, 800481. [CrossRef]

- Cutone, A.; Rosa, L.; Ianiro, G.; Lepanto, M.S.; Di Patti, M.C.B.; Valenti, P.; Musci, G. Lactoferrin’s Anti-Cancer Properties: Safety, Selectivity, and Wide Range of Action. Biomolecules 2020, Vol. 10, Page 456 2020, 10, 456. [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Jaśkiewicz, A.; Tarasiuk, A.; Fichna, J. Lactoferrin: An Overview of Its Main Functions, Immunomodulatory and Antimicrobial Role, and Clinical Significance. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 6016–6033. [CrossRef]

- Nashaat Alnagar, A.; Motawea, A.; Elamin, K.M.; Abu Hashim, I.I. Hyaluronic Acid/Lactoferrin–Coated Polydatin/PLGA Nanoparticles for Active Targeting of CD44 Receptors in Lung Cancer. Pharm Dev Technol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aly, S.; El-Kamel, A.H.; Sheta, E.; El-Habashy, S.E. Chondroitin/Lactoferrin-Dual Functionalized Pterostilbene-Solid Lipid Nanoparticles as Targeted Breast Cancer Therapy. Int J Pharm 2023, 642, 123163. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.M.; Li, W.; Guo, Q. Lactoferrin/Lactoferrin Receptor: Neurodegenerative or Neuroprotective in Parkinson’s Disease? Ageing Res Rev 2024, 101, 102474. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Hou, S. Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Self-Assembled Curcumin-Lactoferrin Nanoparticles: Characterization, Neuroprotective Effect and in Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11, 1168408. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Wen, S.; Li, Y.; An, J.; Wu, Q.; Tong, L.; Mei, X.; Tian, H.; Wu, C. Novel Lactoferrin-Functionalized Manganese-Doped Silica Hollow Mesoporous Nanoparticles Loaded with Resveratrol for the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Mater Today Adv 2022, 15, 100262. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Jie, X.; Chen, Z.; Deng, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pu, F.; Xie, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, P. Borneol and Lactoferrin Dual-Modified Crocetin-Loaded Nanoliposomes Enhance Neuroprotection in HT22 Cells and Brain Targeting in Mice. Eur J Med Chem 2024, 276, 116674. [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Bahramian, B.; Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Ehsani, A.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Bangar, S.P. Application of Lactoferrin in Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review on Opportunities, Advances, and Horizons. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 273, 132969. [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 5938 2022, 23, 5938. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Liu, F.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Su, L.; Liu, G. Alleviative Effect of Lactoferrin Interventions Against the Hepatotoxicity Induced by Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Biol Trace Elem Res 2024, 202, 624–642. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Y.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Xiaochen, K.; Komura, M.; Kato, H.; Nagayasu, Y.; Inaguma, S.; Tsuda, H.; Tomita, M.; Matsuo, Y.; et al. Lactoferrin Prevents Hepatic Injury and Fibrosis via the Inhibition of NF-ΚB Signaling in a Rat Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Model. Nutrients 2022, 14, 42. [CrossRef]

- Farid, A.S.; El Shemy, M.A.; Nafie, E.; Hegazy, A.M.; Abdelhiee, E.Y. Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Lactoferrin in Rats. Drug Chem Toxicol 2021, 44, 286–293. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahhab, K.G.; Ashry, M.; Hassan, L.K.; El-Azma, M.H.; Elqattan, G.M.; Gadelmawla, M.H.A.; Mannaa, F.A. Hepatic and Immune Modulatory Effectiveness of Lactoferrin Loaded Selenium Nanoparticles on Bleomycin Induced Hepatic Injury. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1 2024, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rageh, A.A.; Ferrington, D.A.; Roehrich, H.; Yuan, C.; Terluk, M.R.; Nelson, E.F.; Montezuma, S.R. Lactoferrin Expression in Human and Murine Ocular Tissue. Curr Eye Res 2016, 41, 883–889. [CrossRef]

- Vagge, A.; Senni, C.; Bernabei, F.; Pellegrini, M.; Scorcia, V.; Traverso, C.E.; Giannaccare, G. Therapeutic Effects of Lactoferrin in Ocular Diseases: From Dry Eye Disease to Infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, Vol. 21, Page 6668 2020, 21, 6668. [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, U.; López-López, M.; Varela-Fernández, R.; Otero-Espinar, F.J.; Lema, I. Biomedical Applications of Lactoferrin on the Ocular Surface. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 865 2023, 15, 865. [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, E.; Scotti, L.; Grandori, R.; Tavazzi, S.; Zambon, A. Lactoferrin Concentration in Human Tears and Ocular Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020, 61, 9–9. [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, E.; Astolfi, G.; Grandori, R.; Tavazzi, S.; Versura, P. Development, Optimization, and Clinical Relevance of Lactoferrin Delivery Systems: A Focus on Ocular Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, Vol. 16, Page 804 2024, 16, 804. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Fernández, R.; García-Otero, X.; Díaz-Tomé, V.; Regueiro, U.; López-López, M.; González-Barcia, M.; Lema, M.I.; Otero-Espinar, F.J. Mucoadhesive PLGA Nanospheres and Nanocapsules for Lactoferrin Controlled Ocular Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, Vol. 14, Page 799 2022, 14, 799. [CrossRef]

- López-Machado, A.; Díaz, N.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Badía, J.; Baldomà, L.; Calpena, A.C.; Biancardi, M.; Souto, E.B.; García, M.L.; et al. Development of Topical Eye-Drops of Lactoferrin-Loaded Biodegradable Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Anterior Segment Inflammatory Processes. Int J Pharm 2021, 609, 121188. [CrossRef]

- Antoshin, A.A.; Shpichka, A.I.; Huang, G.; Chen, K.; Lu, P.; Svistunov, A.A.; Lychagin, A. V.; Lipina, M.M.; Sinelnikov, M.Y.; Reshetov, I. V.; et al. Lactoferrin as a Regenerative Agent: The Old-New Panacea? Pharmacol Res 2021, 167, 105564. [CrossRef]

- Trybek, G.; Jedliński, M.; Jaroń, A.; Preuss, O.; Mazur, M.; Grzywacz, A. Impact of Lactoferrin on Bone Regenerative Processes and Its Possible Implementation in Oral Surgery - A Systematic Review of Novel Studies with Metanalysis and Metaregression. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Reyhani, V.; Zibaee, S.; Mokaberi, P.; Amiri-Tehranizadeh, Z.; Babayan-Mashhadi, F.; Chamani, J. Encapsulation of Purified Lactoferrin from Camel Milk on Calcium Alginate Nanoparticles and Its Effect on Growth of Osteoblasts Cell Line MG-63. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2022, 19, 131–145. [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H.; Jo, H.S.; Choi, S.; Song, H.G.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.N.; Kim, S.E.; Park, K. Lactoferrin-Anchored Tannylated Mesoporous Silica Nanomaterials for Enhanced Osteo-Differentiation Ability. Pharmaceutics 2021, Vol. 13, Page 30 2020, 13, 30. [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H.; Sung, K.; Byeon, H.E.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, K.N. Lactoferrin-Anchored Tannylated Mesoporous Silica Nanomaterials-Induced Bone Fusion in a Rat Model of Lumbar Spinal Fusion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 15782 2023, 24, 15782. [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.; da Costa, A.; Silva, D.M.; Gomes, A.C.; Casal, M.; Sencadas, V. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Poly(Lactic Acid)–Bovine Lactoferrin Nanofiber Membranes. Macromol Biosci 2018, 18, 1700324. [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, H.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antimicrobial Properties of Lactoferrin. Biochimie 2009, 91, 19–29. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, W. Antibacterial Properties of Lactoferrin: A Bibliometric Analysis from 2000 to Early 2022. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 947102. [CrossRef]

- Pomastowski, P.; Sprynskyy, M.; Žuvela, P.; Rafińska, K.; Milanowski, M.; Liu, J.J.; Yi, M.; Buszewski, B. Silver-Lactoferrin Nanocomplexes as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138, 7899–7909. [CrossRef]

- Alhadide, L.T.; Nasif, Z.N.; Sultan, M.S. Green Synthesis of Iron Nanoparticles Loaded on Bovine Lactoferrin Nanoparticles Incorporated into Whey Protein Films in Food Applications. Egypt J Chem 2023, 66, 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Suleman Ismail Abdalla, S.; Katas, H.; Chan, J.Y.; Ganasan, P.; Azmi, F.; Fauzi Mh Busra, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Multifaceted Lactoferrin or Graphene Oxide Functionalized Silver Nanocomposites Biosynthesized Using Mushroom Waste and Chitosan. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 4969–4983. [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, H.; Sandvik, K.; Andersen, J.H.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Gutteberg, T.J. Inhibition of HSV Cell-to-Cell Spread by Lactoferrin and Lactoferricin. Antiviral Res 2008, 79, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, H. Anti Herpes Simplex Virus Activity of Lactoferrin/Lactoferricin - An Example of Antiviral Activity of Antimicrobial Protein/Peptide. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2005, 62, 3002–3013. [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Tharakaraman, K.; Sasisekharan, V.; Sasisekharan, R. Glycan–Protein Interactions in Viral Pathogenesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2016, 40, 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Berlutti, F.; Pantanella, F.; Natalizi, T.; Frioni, A.; Paesano, R.; Polimeni, A.; Valenti, P. Antiviral Properties of Lactoferrin—A Natural Immunity Molecule. Molecules 2011, Vol. 16, Pages 6992-7018 2011, 16, 6992–7018. [CrossRef]

- Groot, F.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Sanders, R.W.; Baldwin, C.E.; Sanchez-Hernandez, M.; Floris, R.; van Kooyk, Y.; de Jong, E.C.; Berkhout, B. Lactoferrin Prevents Dendritic Cell-Mediated Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Transmission by Blocking the DC-SIGN--Gp120 Interaction. J Virol 2005, 79, 3009–3015. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.H.; Jenssen, H.; Sandvik, K.; Gutteberg, T.J. Anti-HSV Activity of Lactoferrin and Lactoferricin Is Dependent on the Presence of Heparan Sulphate at the Cell Surface. J Med Virol 2004, 74, 262–271. [CrossRef]

- Krzyzowska, M.; Janicka, M.; Tomaszewska, E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J.; Szymanski, P. Lactoferrin-Conjugated Nanoparticles as New Antivirals. Pharmaceutics 2022, Vol. 14, Page 1862 2022, 14, 1862. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.S.; Borah, S.M.; Gogoi, H.; Asthana, S.; Bhatnagar, R.; Jha, A.N.; Jha, S. Lactoferrin Adsorption onto Silver Nanoparticle Interface: Implications of Corona on Protein Conformation, Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity and the Formulation Adjuvanticity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 361, 470–484. [CrossRef]

- Krzyzowska, M.; Chodkowski, M.; Janicka, M.; Dmowska, D.; Tomaszewska, E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Bednarczyk, K.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J. Lactoferrin-Functionalized Noble Metal Nanoparticles as New Antivirals for HSV-2 Infection. Microorganisms 2022, Vol. 10, Page 110 2022, 10, 110. [CrossRef]

- Yeruva, S.L.; Kumar, P.; Deepa, S.; Kondapi, A.K. Lactoferrin Nanoparticles Coencapsulated with Curcumin and Tenofovir Improve Vaginal Defense Against HIV-1 Infection. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 569–586. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Lakshmi, Y.S.; Kondapi, A.K. Triple Drug Combination of Zidovudine, Efavirenz and Lamivudine Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles: An Effective Nano First-Line Regimen for HIV Therapy. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- El-Fakharany, E.M.; El-Maradny, Y.A.; Ashry, M.; Abdel-Wahhab, K.G.; Shabana, M.E.; El-Gendi, H. Green Synthesis, Characterization, Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Entry, and Replication of Lactoferrin-Coated Zinc Nanoparticles with Halting Lung Fibrosis Induced in Adult Male Albino Rats. Scientific Reports 2023 13:1 2023, 13, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Su, H.; Liu, Z. Enhanced Antifungal Activity of Bovine Lactoferrin-Producing Probiotic Lactobacillus Casei in the Murine Model of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Rodrigues, A.R.O.; Amaral, L.; Côrte-Real, M.; Santos-Pereira, C.; Castanheira, E.M.S. Bovine Lactoferrin-Loaded Plasmonic Magnetoliposomes for Antifungal Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 2162 2023, 15, 2162. [CrossRef]

- Fathil, M.A.M.; Katas, H. Antibacterial, Anti-Biofilm and Pro-Migratory Effects of Double Layered Hydrogels Packaged with Lactoferrin-DsiRNA-Silver Nanoparticles for Chronic Wound Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 991 2023, 15, 991. [CrossRef]

- Polash, S.A.; Hamza, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Dekiwadia, C.; Saha, T.; Shukla, R.; Bansal, V.; Sarker, S.R. Lactoferrin Functionalized Concave Cube Au Nanoparticles as Biocompatible Antibacterial Agent. OpenNano 2023, 12, 100163. [CrossRef]

- Suleman Ismail Abdalla, S.; Katas, H.; Chan, J.Y.; Ganasan, P.; Azmi, F.; Fauzi, M.B. Gelatin Hydrogels Loaded with Lactoferrin-Functionalized Bio-Nanosilver as a Potential Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Dressing for Infected Wounds: Synthesis, Characterization, and Deciphering of Cytotoxicity. Mol Pharm 2021, 18, 1956–1969. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.G.R.; Alencar, W.M.P.; Iacuzio, R.; Silva, N.C.C.; Picone, C.S.F. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Antibacterial Lactoferrin Nanoparticles. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 642–652. [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Sani, M.A.; Khezerlou, A.; Ehsani, A.; McClements, D.J. Multifunctional Nanocomposite Active Packaging Materials: Immobilization of Quercetin, Lactoferrin, and Chitosan Nanofiber Particles in Gelatin Films. Food Hydrocoll 2021, 118, 106747. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Lidon, F. Food Preservatives - An Overview on Applications and Side Effects. Emir J Food Agric 2016, 28, 366. [CrossRef]

- Barbiroli, A.; Bonomi, F.; Capretti, G.; Iametti, S.; Manzoni, M.; Piergiovanni, L.; Rollini, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Lysozyme and Lactoferrin Incorporated in Cellulose-Based Food Packaging. Food Control 2012, 26, 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Rollini, M.; Nielsen, T.; Musatti, A.; Limbo, S.; Piergiovanni, L.; Munoz, P.H.; Gavara, R. Antimicrobial Performance of Two Different Packaging Materials on the Microbiological Quality of Fresh Salmon. Coatings 2016, Vol. 6, Page 6 2016, 6, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, X.G.; Wang, H.Y.; Xia, X.M.; Wang, K.Y. Effects of Esterified Lactoferrin and Lactoferrin on Control of Postharvest Blue Mold of Apple Fruit and Their Possible Mechanisms of Action. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 6432–6438. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.G.R.; Ferreira, N.C.A.; Fiocco, A.C.T.R.; Picone, C.S.F. Lactoferrin-Chitosan-TPP Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Action and Extension of Strawberry Shelf-Life. Food Bioproc Tech 2023, 16, 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Quintieri, L.; Pistillo, B.R.; Caputo, L.; Favia, P.; Baruzzi, F. Bovine Lactoferrin and Lactoferricin on Plasma-Deposited Coating against Spoilage Pseudomonas Spp. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2013, 20, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Dash, K.K.; Deka, P.; Bangar, S.P.; Chaudhary, V.; Trif, M.; Rusu, A. Applications of Inorganic Nanoparticles in Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2022, Vol. 14, Page 521 2022, 14, 521. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, L.; Jia, M.; Xiong, Y. Nanofillers in Novel Food Packaging Systems and Their Toxicity Issues. Foods 2024, Vol. 13, Page 2014 2024, 13, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Oymaci, P.; Altinkaya, S.A. Improvement of Barrier and Mechanical Properties of Whey Protein Isolate Based Food Packaging Films by Incorporation of Zein Nanoparticles as a Novel Bionanocomposite. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 54, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Calva-Estrada, S.J.; Jiménez-Fernández, M.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Protein-Based Films: Advances in the Development of Biomaterials Applicable to Food Packaging. Food Engineering Reviews 2019 11:2 2019, 11, 78–92. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A.; Wang, B.; Oh, J.H. Antimicrobial Activity of Lactoferrin against Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria Incorporated into Edible Chitosan Film. J Food Prot 2008, 71, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- Khezerlou, A.; Tavassoli, M.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Hashemi, M.; Ehsani, A.; Bangar, S.P. Multifunctional Food Packaging Materials: Lactoferrin Loaded Cr-MOF in Films-Based Gelatin/κ-Carrageenan for Food Packaging Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 251, 126334. [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Khezerlou, A.; Sani, M.A.; Hashemi, M.; Firoozy, S.; Ehsani, A.; Khodaiyan, F.; Adibi, S.; Noori, S.M.A.; McClements, D.J. Methylcellulose/Chitosan Nanofiber-Based Composites Doped with Lactoferrin-Loaded Ag-MOF Nanoparticles for the Preservation of Fresh Apple. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 259, 129182. [CrossRef]

- Badawy, M.E.I.; Lotfy, T.M.R.; Shawir, S.M.S. Preparation and Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan-Silver Nanoparticles for Application in Preservation of Minced Meat. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2019 43:1 2019, 43, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liao, Q.; Tao, H.; Wang, H. Photodynamic Inactivation of Staphylococcus Aureus in the System of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Sensitized by Hypocrellin B and Its Application in Food Preservation. Food Research International 2022, 156, 111141. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Silver Nanoparticles in Therapeutics and Beyond: A Review of Mechanism Insights and Applications. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1618. [CrossRef]

- Hoseinnejad, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Katouzian, I. Inorganic and Metal Nanoparticles and Their Antimicrobial Activity in Food Packaging Applications. Crit Rev Microbiol 2018, 44, 161–181. [CrossRef]

- Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Eker, F.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Gold Nanoparticles: Multifunctional Properties, Synthesis, and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1805. [CrossRef]

- Soyer, F.; Keman, D.; Eroğlu, E.; Türe, H. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effects of Activated Lactoferrin and Rosemary Extract in Vitro and Potential Application in Meat Storage. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 4395–4403. [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.M.; Taki, T.M.; Badawi, S.K. Effect of Lactoferrin in Reducing the Growth of Microorganisms and Prolonging the Preservation Time of Cream. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2024, 1371, 062041. [CrossRef]

- Quintieri, L.; Caputo, L.; Monaci, L.; Deserio, D.; Morea, M.; Baruzzi, F. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Pepsin-Digested Bovine Lactoferrin on Spoilage Bacteria Contaminating Traditional Mozzarella Cheese. Food Microbiol 2012, 31, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.G.R.; Picone, C.S.F. Antimicrobial Activity of Lactoferrin-Chitosan-Gellan Nanoparticles and Their Influence on Strawberry Preservation. Food Research International 2022, 159, 111586. [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Duman, H.; Yalçıntaş, Y.M.; Canbolat, A.A.; Kalkan, A.E.; Karav, S.; Šamec, D. Antimicrobial Properties of Colostrum and Milk. Antibiotics 2024, Vol. 13, Page 251 2024, 13, 251. [CrossRef]

- El-Fakharany, E.M.; Sánchez, L.; Al-Mehdar, H.A.; Redwan, E.M. Effectiveness of Human, Camel, Bovine and Sheep Lactoferrin on the Hepatitis C Virus Cellular Infectivity: Comparison Study. Virol J 2013, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Avery, T.M.; Boone, R.L.; Lu, J.; Spicer, S.K.; Guevara, M.A.; Moore, R.E.; Chambers, S.A.; Manning, S.D.; Dent, L.; Marshall, D.; et al. Analysis of Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Human Milk Lactoferrin Compared to Bovine Lactoferrin against Multidrug Resistant and Susceptible Acinetobacter Baumannii Clinical Isolates. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 2116–2126. [CrossRef]

- Krolitzki, E.; Schwaminger, S.P.; Pagel, M.; Ostertag, F.; Hinrichs, J.; Berensmeier, S. Current Practices with Commercial Scale Bovine Lactoferrin Production and Alternative Approaches. Int Dairy J 2022, 126, 105263. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.A.; Berenz, A.; Itell, H.L.; Conaway, M.; Blackman, A.; Nataro, J.P.; Permar, S.R. Dose Escalation Study of Bovine Lactoferrin in Preterm Infants: Getting the Dose Right. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2020, 99, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, T.J.; Zegarra, J.; Bellomo, S.; Carcamo, C.P.; Cam, L.; Castañeda, A.; Villavicencio, A.; Gonzales, J.; Rueda, M.S.; Turin, C.G.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Bovine Lactoferrin for Prevention of Sepsis and Neurodevelopment Impairment in Infants Weighing Less Than 2000 Grams. J Pediatr 2020, 219, 118-125.e5. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Tripepi, G.; Naldi, E.; Aimati, M.; Santangeli, S.; Venditto, F.; Caldarelli, M.; Valenti, P. Ambulatory Covid-19 Patients Treated with Lactoferrin as a Supplementary Antiviral Agent: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 4276. [CrossRef]

- Parc, A. Le; Karav, S.; Rouquié, C.; Maga, E.A.; Bunyatratchata, A.; Barile, D. Characterization of Recombinant Human Lactoferrin N-Glycans Expressed in the Milk of Transgenic Cows. PLoS One 2017, 12. [CrossRef]

- Karav, S. Selective Deglycosylation of Lactoferrin to Understand Glycans’ Contribution to Antimicrobial Activity of Lactoferrin. Cell Mol Biol 2018, 64, 52–57. [CrossRef]

- Malinczak, C.A.; Burns Naas, L.A.; Clark, A.; Conze, D.; DiNovi, M.; Kaminski, N.; Kruger, C.; Lönnerdal, B.; Lukacs, N.W.; Merker, R.; et al. Workshop Report: A Study Roadmap to Evaluate the Safety of Recombinant Human Lactoferrin Expressed in Komagataella Phaffii Intended as an Ingredient in Conventional Foods – Recommendations of a Scientific Expert Panel. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2024, 190, 114817. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Crawford, R.B.; Blevins, L.K.; Kaminski, N.E.; Sass, J.S.; Ferraro, B.; Vishwanath-Deutsch, R.; Clark, A.J.; Malinczak, C.A. Dose Range-Finding Toxicity Study in Rats With Recombinant Human Lactoferrin Produced in Komagataella Phaffii. Int J Toxicol 2024, 43, 407–420. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.D.; Guarneiri, L.L.; Adams, C.G.; Wilcox, M.L.; Clark, A.J.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Maki, K.C.; Malinczak, C.-A. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial to Assess the Effects of Lactoferrin at Two Doses vs. Active Control on Immunological and Safety Parameters in Healthy Adults. Int J Toxicol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Mettenbrink, E.M.; Deangelis, P.L.; Wilhelm, S. Nanoparticle Toxicology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2021, 61, 269–289. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P. Reactive Oxygen Species-Related Nanoparticle Toxicity in the Biomedical Field. Nanoscale Research Letters 2020 15:1 2020, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Silver Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis Methods and Chemical and Physical Properties. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1527. [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath-Deutsch, R.; Dallas, D.C.; Besada-Lombana, P.; Katz, L.; Conze, D.; Kruger, C.; Clark, A.J.; Peterson, R.; Malinczak, C.-A. A Review of the Safety Evidence on Recombinant Human Lactoferrin for Use as a Food Ingredient. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2024, 189, 114727. [CrossRef]

- Meena, J.; Gupta, A.; Ahuja, R.; Singh, M.; Bhaskar, S.; Panda, A.K. Inorganic Nanoparticles for Natural Product Delivery: A Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020 18:6 2020, 18, 2107–2118. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J. Inorganic Nanoparticles in Clinical Trials and Translations. Nano Today 2020, 35, 100972. [CrossRef]

- Horie, M.; Tabei, Y. Role of Oxidative Stress in Nanoparticles Toxicity. Free Radic Res 2021, 55, 331–342. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).