1. Introduction

Polysialic acid (polySia) expression on neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] is called NCAM polysialylation, which is related to cancer cell migration through the interactions between polysialyltransferases (polySTs) and CMP-Sia, and polyST and polysialic acid (polySia) [

8,

9]. More specifically, these interactions are actually the direct bindings of Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) to CMP-Sia, and PSTD to polySia [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. PSTD is a polybasic motif of 32 amino acids in two polySTs, ST8SiaIV and ST8SiaII [

16].

Inhibition of posttranslational modifications (PTM) is related to a number of diseases such as cancer, nervous and cardiovascular system diseases. One of the latest advances in PTM research is inhibition of polysialylation of neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) [

17,

18], which is strongly related to the migration and invasion of tumor cells and with aggressive, metastatic disease and poor clinical prognosis in the clinic due to the formation of polysialic acid (poly-Sia) on the surface of NCAM [

19,

20,

21,

22].

It has been known that NCAM-polySia expression on cancer cells is catalyzed by two polysialyltransferases (polySTs), ST8SiaIV and ST8SiaII, and specifically two polybasic motifs, Polybasic Region (PBR) and Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) within each polyST, have been found to be critically important for polyST activity based on recent mutation and molecular modeling analyses [

16,

23]. Thus, the intermolecular interactions of PBR-NCAM, PSTD-polySia and PSTD-(CMP-sialic acid) have been suggested during NCAM polysialylation and tested by more recent NMR studies [

14]. Furthermore, a modulation model of NCAM-polysialylation and cell migration has been proposed by incorporating the intramolecular interaction of PBR-PSTD into above intermolecular interaction [

14]. This model has been further supported using Chou’s wenxiang diagram method [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Two inhibitors of NCAM polysialylation, Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and cytidine monophosphate (CMP), have been proposed as drug research and help to development related to the tumor-targeted polysialyltranseferases based on above modulation model of NCAM-polysialylation.

The previous in vitro study showed that heparin LMWH is an efficient inhibitor due to its stronger binding to the PSTD [

16], and was further supported using the recent NMR studies [

23]. However, the use of heparin should be carefully, because the previous reports indicated that intracerebral hemorrhage of patients were related to heparin intake [

29].

Another inhibitor, cytidine monophosphate (CMP) has been also verified that the polysialylation could be partially inhibited when CMP-Sia and polySia co-exist in solution by the recent NMR studies. CMP-Sia may play a role in reducing the gathering extent of polySia chains on the PSTD, and may benefit for the inhibition of polysialylation [

30]. However, CMP could not inhibit the PSTD-polySia interaction [

30].

Lactoferrin (LF) is an iron-binding glycoprotein composed of 49 amino acids, and has antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor, and immunological activity [

31]. In the more recent studies, a 11-residual peptide (RRWQWRMKKLG) from the N-terminus [

32] of LF, was designed as (LFcinB11), which has also similar antimicrobial activities in bovine lactoferricin (BLFC) [

33,

34].

In this study, our interest is to determine whether can LFcinB11 also inhibit NCAM polysialylation? If so, what its minimum concentration to ensure its inhibitory effect on the polysialylation?

In addition, the previous study has proposed that the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) could be inhibited through the interaction between polySia and LF, using a native gel electrophoresis application using in vitro experiments [

31,

32,

33]. In the current study, molecular mechanism of this interaction is determined based on our NMR studies. Thus, LFcinB11 may play a bifunctional role in inhibition of formation of NETs and NCAM polysialylation.

2. Results

2.1. CD Data

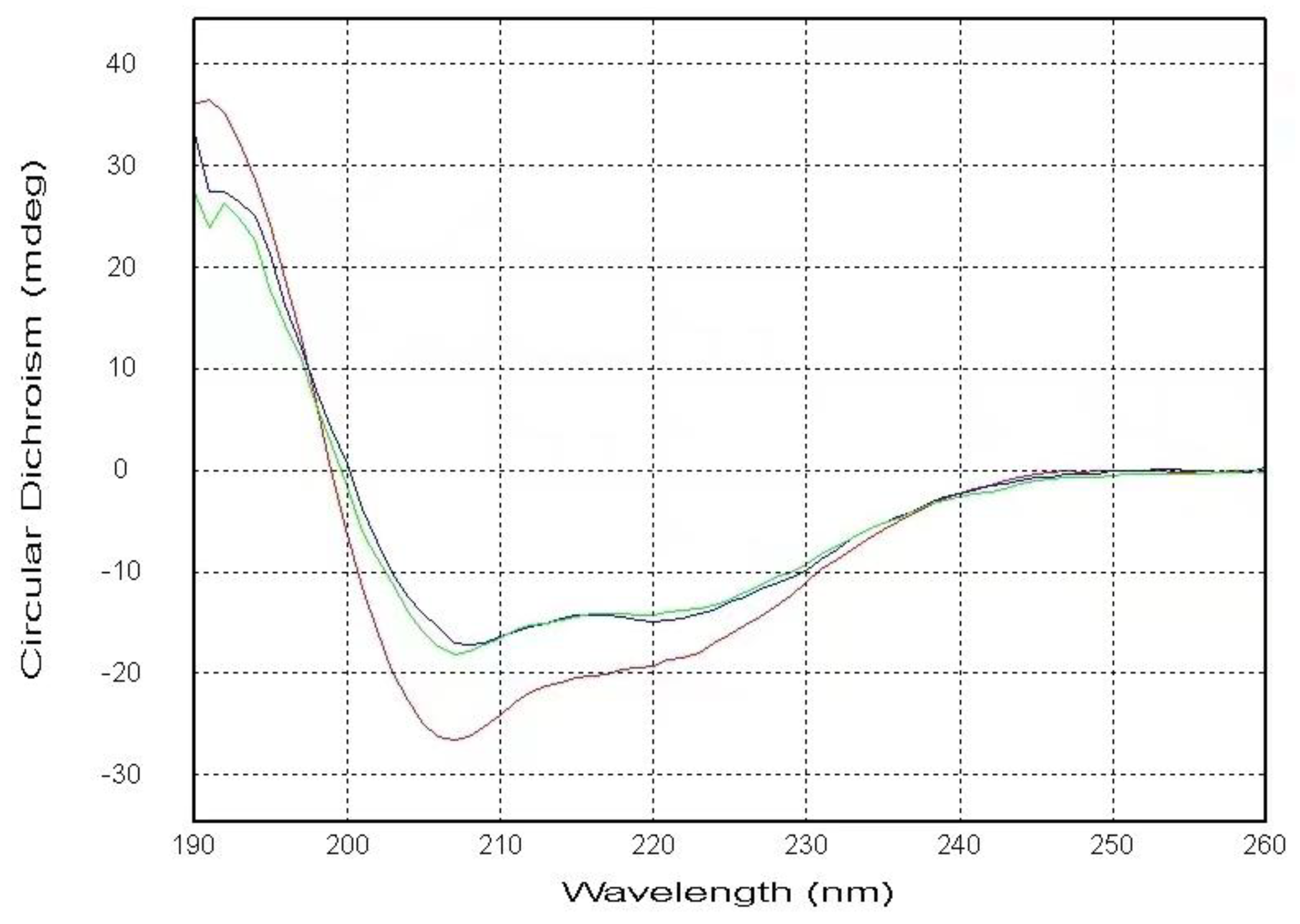

As shown in

Figure 1, our CD spectra display that the α-helical content of the PSTD contains 23.0% in the absence of any ligands. The helical contents were decreased to 16.4% after adding the mixture of 40uM (CMP-Sia) and 4uM polySia, and was further decreased to 14.8% after added LFcinB11. These results suggested the helices in the PSTD were unwound due to the addition of the mixture of CMP-Sia and polySia, and further unwinding after adding LFcinB11. The decreases of helical contents in the PSTD indicate its conformational change and verified the PSTD not only interact with the mixture of CMP-Sia and polySia as the previous study [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], but also suggest an interaction between the PSTD and LFcinB11. However, the difference of 16.4% and 14.8% is only 1.6%. This means that the helical structure of the PSTD is basically stable after LFcinB11 was added to the sample. A possible explanation is that there is an interaction between LFcinB11 and polySia. Because This interaction may decrease the helical unwinding extent in the PSTD.

2.2. NMR Results (a)

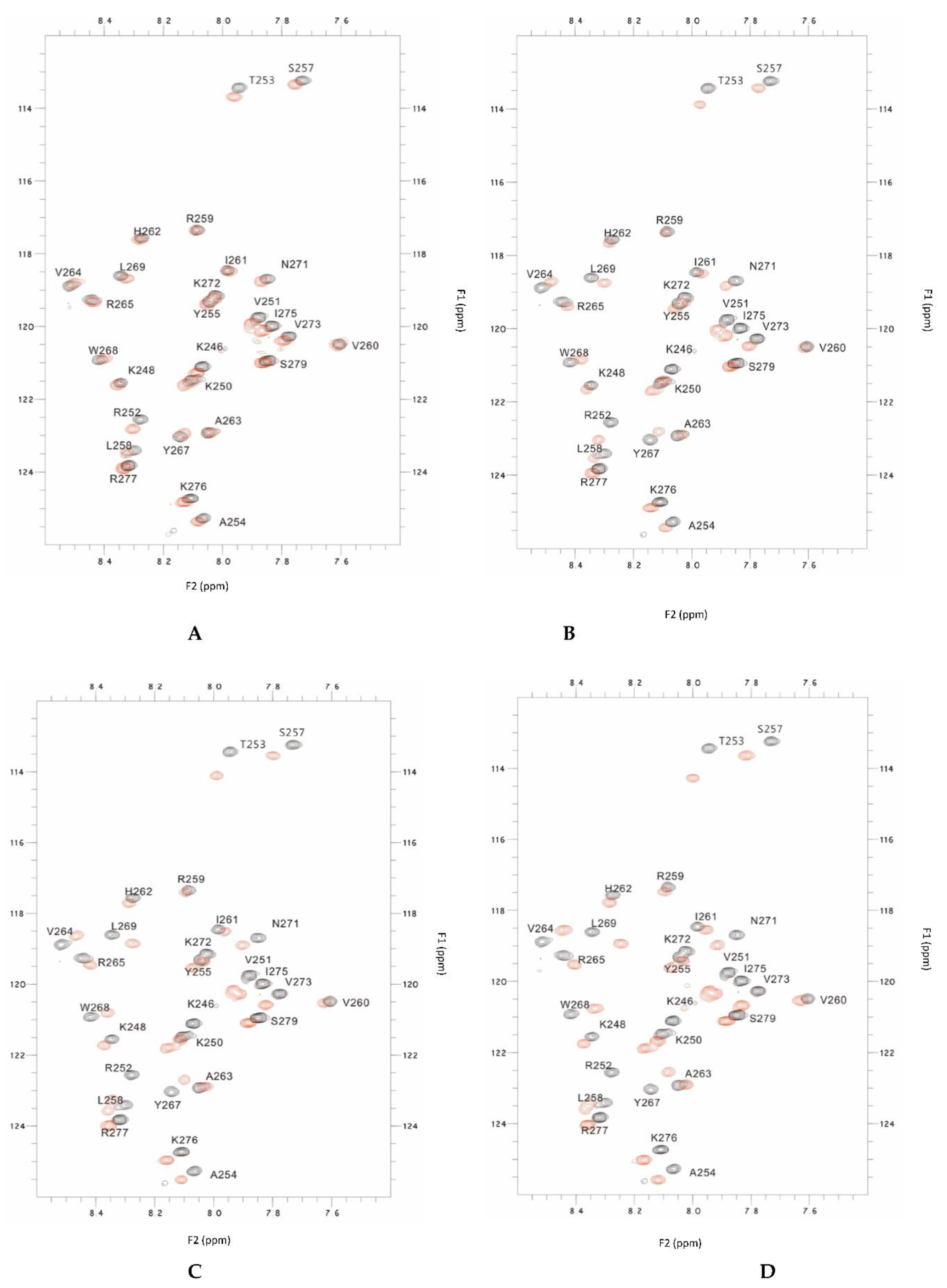

In order to verify the interaction between the PSTD and LFcinB11, 2D-HSQC experiments of the mixtures of the LFcinB11 with different concentration and the PSTD were carried out. In addition, the PSTD-LFcinB11 interaction was also tested.

2.2.1. The Interaction between the PSTD and 20 uM LFcinB11

In this study, the overlaid HSQC spectra of the PSTD for the PSTD-(20 uM LFcinB11) interaction, showed that the significant changes in chemical shift are found in 8 residues, K246, K250, V251, R252, T253, S257, V273 and I275 (

Table 1 &

Figure 2A), in which most residues are located on the binding region of CMP-Sia (K246-L258) (

Table 2) except from two residues V273 and I275 (

Figure 2A). In addition, the CSP values in this range (K246-L258) for the PSTD-20uM LFcinB11 interaction are less than that for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction (

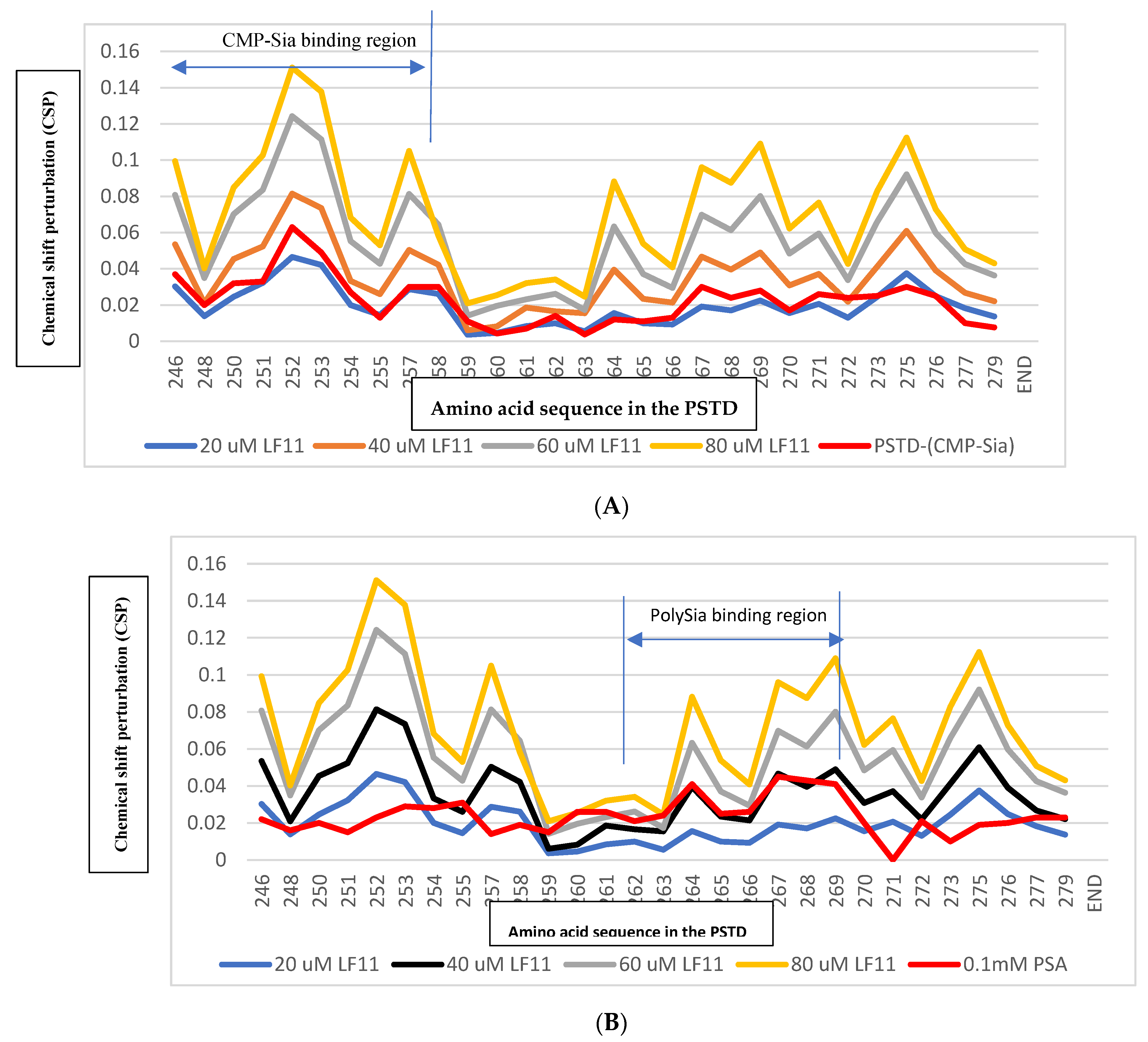

Figure 2). These results indicate that 20uM LFcin11 could not inhibit the interaction between the PSTD-(CMP-Sia). Similarly, the CSPs values in the polySia binding region of the PSTD (A263-N271) are also smaller that for the PSTD-polySia interaction (

Figure 3).

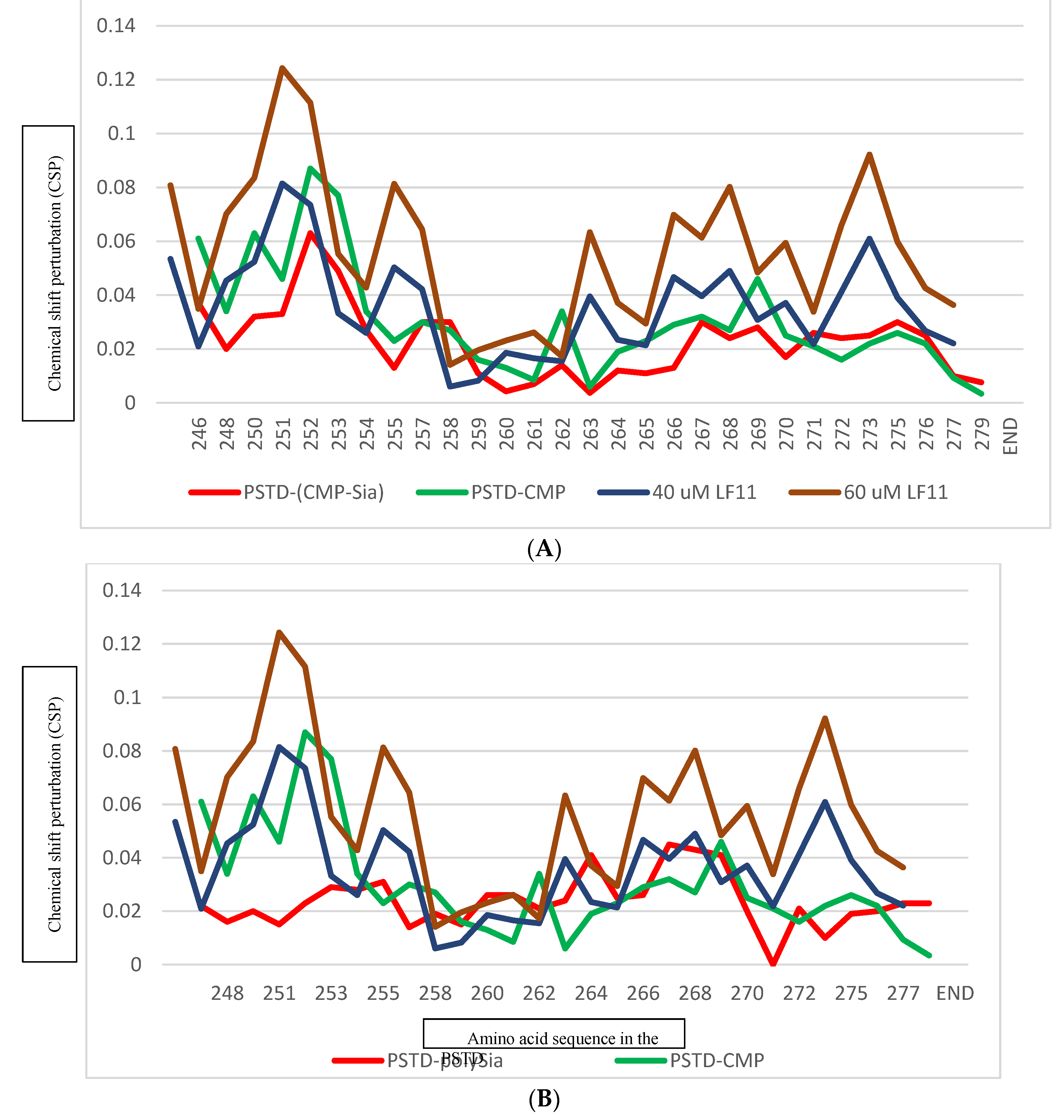

2.2.2. The Interaction between the PSTD and 40 uM LFcinB11

When LFcinB11 concentration was increased to 40 uM, the significant changes in chemical shift are found in 19 residues, K246, K248, K250, V251, R252, T253, A254, Y255, S257, L258, V264, R265, Y267, W268, L269, V273, I275, R277 and S279, and there are only 6 residues (R259, V260, I261, H262, A263 and K272) no change in chemical shift (

Table 1 &

Figure 2b). The CSPs for PSTD-40uM LFcinB11interaction are larger than that for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) and for the PSTD-20uM LFcinB11 interactions (

Figure 3a) in the CMP-Sia binding region, indicating the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction could be inhibited by 40uM LFcin. In addition, most CSPs for PSTD-40uM LFcin interaction and the PSTD-polySia interaction are very closed in the polySia binding region (

Figure 3b). However, the CSPs for the former are larger than that for the later at residue L269 and N271 (

Figure 3b). Thus suggest that the PSTD-polySia interaction could be inhibited when LFcinB11 concentration is more than 40uM.

2.2.3. The Interaction between the PSTD and 60 uM LFcinB11

LFcin11 concentration was increased to 60 uM, the significant changes in chemical shift are found in most residues according to the overlaid HSQC spectra (

Figure 2C), and there are only 3 residues (R259, V260, and A263) no change in chemical shift (

Table 1 &

Figure 2C). The CSPs for PSTD-60uM LFcinB11 interaction are larger than that for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction (

Figure 3a) in the CMP-Sia binding region, indicating the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction could be inhibited by 60uM LFcinB11. In addition, the CSPs for PSTD-60uM LFcinB11 interaction are also larger than that for the PSTD-polySia interaction in the polySia binding region (

Figure 3b), and thus further suggest that the PSTD-polySia interaction could be inhibited by 60uM LFcinB11.

2.2.4. The Interaction between the PSTD and 80 uM LFcinB11

When LFcinB11 concentration was increased to 80 uM, almost all residues of the PSTD have changed in chemical shift (

Figure 2D), and the CSP of each residue is larger than that for the interaction between the PSTD and 60 uM LFcin. In the CMP-Sia binding region for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction, the maximum CSP is 0.151, which is larger than that for the PSTD-60uM LF, and in the polySia binding region, the maximum CSP is 0.109, which is also much larger than that for the PSTD-60uM LFcinB11 (

Table 2). These results indicate that the CSPs in both CMP-Sia and polySia binding regions of the PSTD are increased with LF’s concentration.

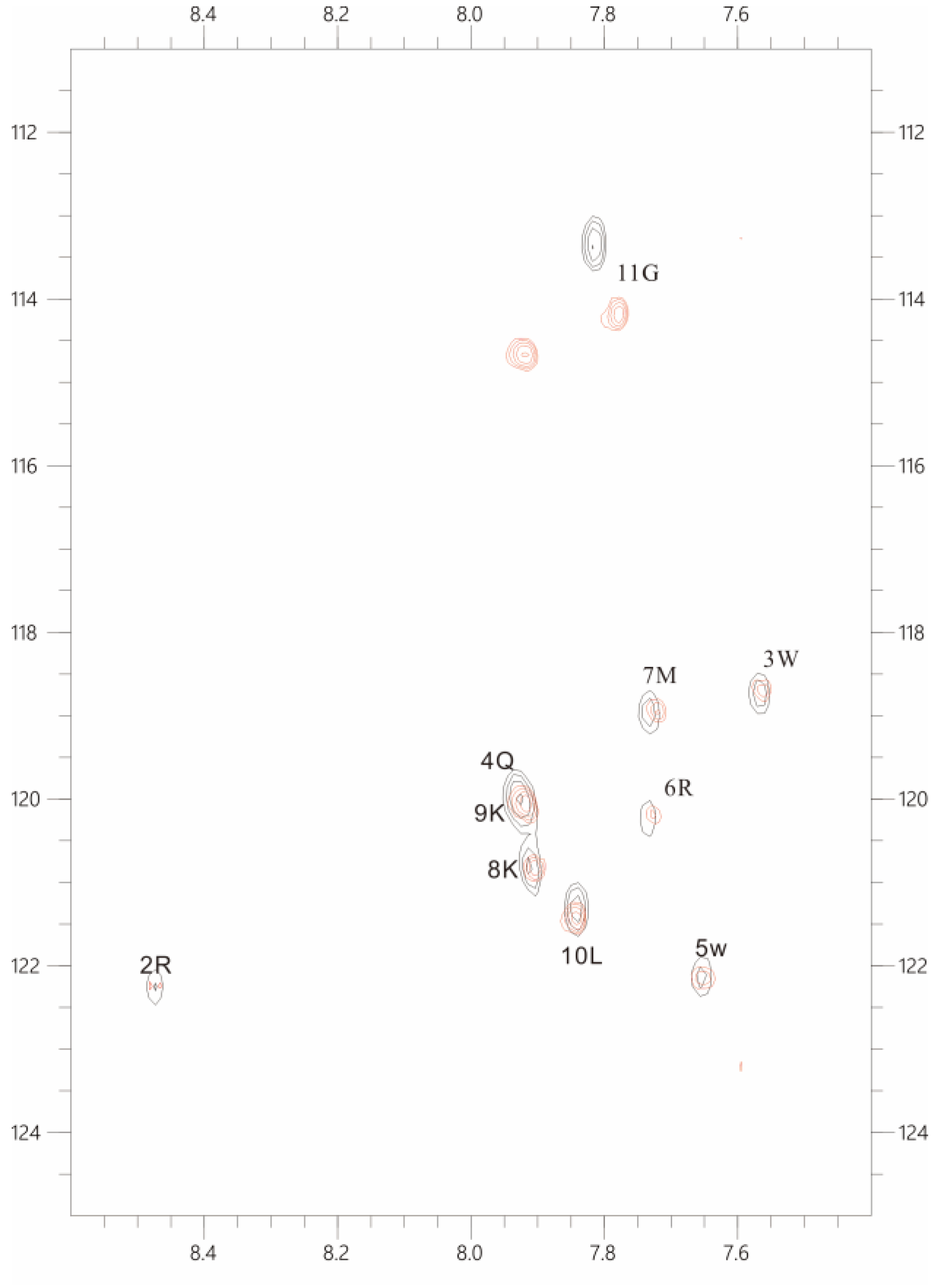

2.2.5. The Interaction between LFcinB11 and polySia

In order to determine the interaction between polySia and LFcinB11, the overlaid 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were carried out at our NMR spectrometer. As shown in

Figure 4, there is no any chemical shift is detected except residue 11G after polySia and LFcinB11 were mixed. However, the peak intensities of almost all residues were significantly decreased, thus suggesting the interaction between polySia and LFcinB11 through the formation of LFcinB11-polySia aggregates.

3. Discussion

So far both 3D X-ray and NMR structures of the polySTs have not yet been reported, due to the existence of many hydrophobic residues in the polySTs, which are in the membrane environment [

13,

14]. However, the 3-D solution structure of the PSTD peptide, an active site in the ST8Sia IV, has been obtained based on our NMR studies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Thus, a hypothesis has been proposed: the interaction between the PSTD and the ligands such as CMP-Sia, polySia or any possible inhibitors may correspond to the interactions between the polyST and these ligands. This is an efficient research strategy and methodology for studying biological problems using biophysical and NMR structural biology. The above hypothesis has been successfully tested by the recent NMR studies [

23,

24,

25].

Above CD spectra qualitatively demonstrate the possible interaction between the PSTD and LfcinB11. The more details of the interactions between the PSTD and Lfcin11 were provided by our NMR experimental results

The polysialylation of trimer of α-2,8-linked sialic acid (triSia) was inhibited by cytidine monophosphate (CMP) in the presence of ST8SiaII and CMP-Neu5Ac (CMP-Sia) based on in vitro experiments [

30,

35]. The more recent studies verified that the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) could be inhibited by CMP, but the PSTD-polySia binding could not be inhibited by CMP even in mixture status of CMP-Sia, polySia and the PSTD based on our NMR data [

30].

There are two binding regions for CMP-Sia in the PSTD, one is in the residue range K246-L258, and other one in the range Y267-R277 [

30]. The former is also the binding region of CMP, and the latter is covered in CMP-PSTD binding region (V264-K276) [

30]. In this study, the CSP values for the PSTD-LFcinB11interactions are larger than that for the PSTD-CMP and the PSTD-polySia interactions when LFcinB11 concentration at least 40 uM (

Figure 5). These results indicate that LFcinB11 is more powerful in inhibiting both the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) and the PSTD-polySia interactions than CMP.

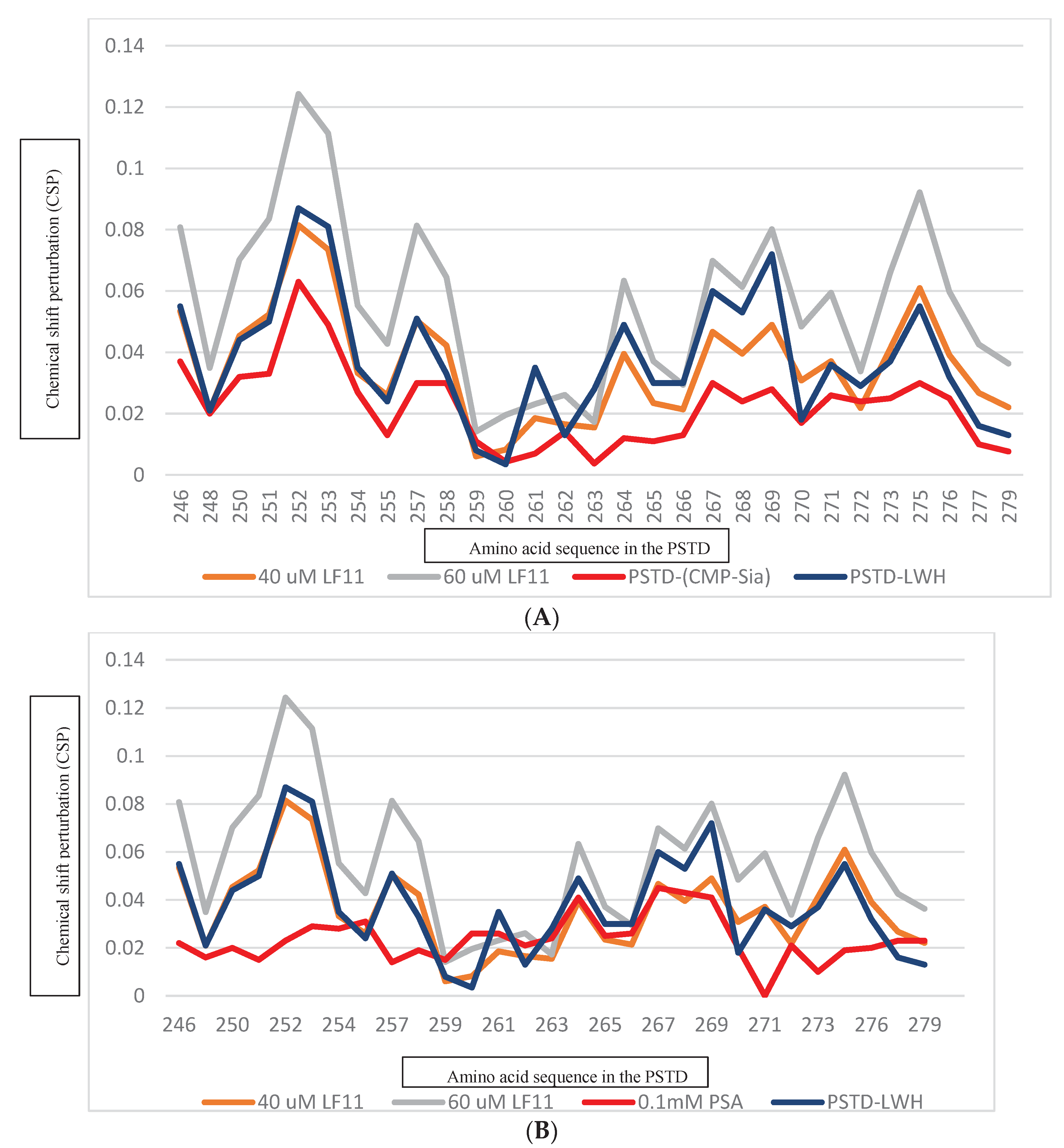

The previous NMR studies indicated that heparin LMWH is an effective inhibitor of NCAM polysialylation. Twelve residues, N247, V251, R252, T253, S257, R265, Y267, W268, L269, V273, I275, and K276 in the PSTD were discovered to be the binding sites of the LMWH, and they were mainly located on the long α-helix of the PSTD, and the short 3-residue loop of the C-terminal PSTD [

23]. The range of LNWH binding to the PSTD is almost same with that of the LF (

Figure 6). As shown in

Figure 6a and

Table 2, the CSPs of the PSTD for the PSTD-LMWH (80uM) interaction are larger than that for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction, indicated the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) binding could be inhibited by 80 uM LMWH. However, only take 40 uM LF, both the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction and the PSTD-polySia interaction could be inhibited (

Figure 6b). In addition, as an inhibitor LFcinB11 may be more safety than LMWH. Because the intracerebral hemorrhage of patients was related to heparin intake [

29].

LFcinB11not only can interact with the PSTD to inhibit the interactions of the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) and the PSTD-polySia, but also can directly interact with polySia (

Figure 4). This NMR result is consistent with the results using in vitro experiments [

32,

33,

34], and proposed that the major contribution of the interaction between LF and polySia is from the N-ternminal residues of LF, particularly in LFcinB11 domain.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material Sources

The PSTD (246K-277R) should be a 32 amino acid sequence peptide from ST8Sia IV molecule. However, in order to obtain more accurate 3D structural information by NMR spectroscopy, one amino acid (245L) and two amino acids (278P and 279S) from ST8Sia IV sequence were added into the N- and C- terminals of PSTD, respectively [

12,

13,

14,

25,

30]. Thus, a 35 amino acid sequence peptide sample containing PSTD was synthesized as follows:

245LKNKLKVRTAYPSLRLIHAVRGYWLTNKVPIKRPS279”. In which, the PSTD sequence is labelled by underline. This intact peptide sample was chemically synthesized by automated solid-phase synthesis using the F-MOC-protection strategy and purified by HPLC (GenScript, NanJing, China). Its molecular weight was determined to be 4117.95 and its purity established to be 99.36%.

LFcinB11 peptide was purchased from BACHEM, amino sequence RRWQWRMKKLG, and relative molecular mass 1544.8. PolySia were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

4.2. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

The concentrations of the 35 amino acid-PSTD peptide and LFcinB11 in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.7) with 25% tetrafluoroethylene (TFE) were 8.0 uM and 400 uM, respectively. The measured and recorded methods of CD spectra are the same as the previous articles [

23,

30].

4.3. NMR Sample Preparation

The 35 amino acid peptide containing the PSTD was prepared as described above in a 20 mM phosphate buffer containing 25% TFE. Chemical shifts were referenced with respect to 2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) used as the internal standard.

For both the 1-D and 2-D NMR experiments, the concentration of the PSTD peptide in the absence or the presence of LFcinB11 was 2.0 mM. The concentrations of LFcinB11 in the presence of the PSTD were all 20, 40, 60, and 80 uM, respectively. For 2-D NMR experiments of the polySia-LBcinB11 interaction, the concentration of polySia and LFcinB11 are all 50 uM.

All NMR samples were dissolved in 25%TFE (v/v), 10% D2O (v/v), and 65% (v/v) 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.7). Following this, 2-Dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) was added to all samples to serve as a reference standard.

4.4. NMR Spectroscopic Methods

NMR spectroscopy is a

powerful tool for studying biomolecule-protein (DNA) or protein-ligand interactions [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. All NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K using an Agilent DD2 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cold-probe in the NMR laboratory at the Guangxi Academy of Sciences. Water resonance was suppressed using pre-saturation. NOESY mixing times were set at 300 msec while the TOCSY experiments were recorded with mixing times of 80 msec [

30,

46]. All chemical shifts were referenced to the internal DSS signal set at 0.00 ppm for proton, and indirectly for carbon and nitrogen [

23,

30]. Data were typically apodized with a shifted sine bell window function and zero-filled to double the data points in F1, prior to being Fourier transformed. NMRPipe [

23,

30]. CcpNmr (

www.ccpn.ac.uk/v2-software/analysis) was used for processing the data and spectral analysis. Spin system identification and sequential assignment of individual resonances were carried out using a combination of TOCSY and NOESY spectra, as previously described [

23,

30], and coupled with an analysis of 1H-15N and 1H-13C HSQC for overlapping resonances. In order to identify and characterize the specificity of the PSTD-ligand binding, the chemical shift perturbation (CSP) of each amino acid in the PSTD was calculated using the formula:

Where, DN and DNH represent the changes in 15N and 1H chemical shifts, respectively, upon ligand binding [

46].

5. Conclusion

Our results indicate that LFcin11 is a more powerful inhibitor than LMWF and CMP, and can be safely used. Furthermore, the bifunctional effects of LFcinB11are proposed, i.e. LFcinB11 not only can inhibit the NCAM polysialylation through the PSTD-LFcinB11 interaction, but also inhibit the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), a network of extracellular strings of DNA that bind pathogenic microbes [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Because the NETs role in promoting tumor metastasis formation could be blocked by addition of LFcin B11 [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62], a binfunctional effect of LFcinB11 has been proposed in this study. In the future studies, we will further study the molecular mechanism of the interaction between polySia and LFcinB11 to understand how does LFcin block tumor metastasis formation related to the formation of the NETs.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, GP. Z and RB. H.; Methodology, B.L.; JX.L. & XH. L; Validation, SM. L. & L.X.P.; Formal Analysis, GP. Z.; Investigation, B.L.; SJ. L and GP.Z.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, GP.Z.; Writing – Review & Editing, GP.Z.; Supervision, GP. Z & RB. H.; Project Administration, SM. L; Funding Acquisition, SM. L.; B. L & GP.Z.

Funding Sources: This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China(32060216), Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Project(GuiKe AA20297007, Nanning Scientific Research and Technology Development Project(20223038), Guangxi Major science and technology Innovation base construction project(2022-36-Z06-01), Central Guidance Fund for Local Scientific and Technological Development Project (Guike ZY23055011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the 800 MHz NMR facility of Guangxi Academy of Sciences for the support in using NMR spectra acquirement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| polySia |

polysialic acid |

| Sia |

mono-sialic acid |

| CMP-Sia |

cytidine monophosphate-sialic acid |

| NCAMs |

neural cell adhesion molecules |

| polySTs |

polysialyltransferases (ST8Sia II (STX) & ST8Sia IV (PST) |

PSTD

LMWH

CMP |

polysialyltransferase domain

Low molecular weight heparin

cytidine monophosphate |

| LF |

Lactoferrin |

| CSP |

chemical shift perturbation |

References

- Lepers, A.H.; Petit, D.; Mollicone, R.; Delannoy, P.; Petit, J.M.; Oriol, R. Evolutionary history of the alpha2,8-sialyltransferase (ST8Sia) gene family: Tandem duplications in early deuterostomes explain most of the diversity found in the vertebrate ST8Sia genes. Evolutionary Biology. 2008, 8, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanneau, C.; Chazalet, V.; Augé, C.; Soumpasis, D.M.; Harduin-Lepers, A.; Delannoy, P.; Imberty, A.; Breton, C. Structure- function analysis of the human sialyltransferase ST3Gal I: role of n-glycosylation and a novel conserved sialylmotif. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 13461–13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Kurata, K.; Kojima, N.; Kurosawa, N.; Ohta, S.; Hanai, N.; Tsuji, S.; Nishi, T. Expression cloning of a GM3-specific al- pha-2,8-sialyltransferase (GD3 synthase). J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 15950–15956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, J.; Fukuda, M.N.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Kanamori, A.; Sasaki, K.; Nishi, T.; Fukuda, M. Expression cloning of a human GT3 synthase. GD3 AND GT3 are synthesized by a single enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 3684–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.P.; Fujimoto, I.; Rutishauser, U.; Leckband, D.E. Direct evidence that neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) polysialyla- tion increases intermembrane repulsion and abrogates adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidenfaden, R.; Krauter, A.; Schertzinger, F.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Hildebrandt, H. Polysialic acid directs tumor cell growth by con- trolling heterophilic neural cell adhesion molecule interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 5908–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggers, K.; Werneburg, S.; Schertzinger, A.; Abeln, M.; Schiff, M.; Scharenberg, M.A.; Burkhardt, H.; Mühlenhoff, M.; Hildebrandt, H. Psialic acid controls NCAM signals at cell-cell contacts to regulate focal adhesion independent from FGF receptor activity. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124 Pt 19, 3279–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troy, F.A. II Polysialylation: from bacteria to brains. Glycobiol- ogy 1992, 2, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, D.; Teppa, E.; Mir, A.M.; Vicogne, D.; Thisse, C.; Thisse, B.; Filloux, C.; Harduin-Lepers, A. Integrative view of α2,3- sialyltransferases (ST3Gal) molecular and functional evolution in deuterostomes: significance of lineage-specific losses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 906–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.-P.; Liao, S.-M.; Chen, D.; Huang, R.-B. The Cooperative Effect between Polybasic Region (PBR) and Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) within Tumor-Target Polysialyltranseferase ST8Sia II. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 19, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.B.; Cheng, D.; Liao, S.M.; Lu, B.; Wang, Q.Y.; Xie, N.Z.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Zhou, G.P. The Intrinsic Relationship Between Structure and Function of the Sialyltransferase ST8Sia Family Members. Curr Top Med Chem 2017, 17, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.M.; Lu, B.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, Z.L.; Liang, S.J.; Chen, D.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. Molecular Interactions of the Polysialytransferase Domain (PSTD) in ST8Sia IV with CMP-Sialic Acid and Polysialic Acid Required for Polysialylation of the Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule Proteins: An NMR Study. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.M.; Liu, X.H.; Peng, L.X.; Lu, B.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. Molecular Mechanism of Inhibition of Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) by Heparin. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Liu, X.H.; Liao, S.M.; Lu, Z.L.; Chen, D.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. A Possible Modulation Mechanism of Intramolecular and Intermolecular Interactions for NCAM Polysialylation and Cell Migration. Curr Top Med Chem 2019, 19, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.P. The Medicinal Chemistry of Structure-based Inhibitor/Drug Design: Current Progress and Future Prospective. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 1097–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, D.; Zhang, L.; Troy, F.A. Molecular basis for polysialylation: A novel polybasic polysialyltransferase domain (PSTD) of 32 amino acids unique to the α2,8-polysialyltransferases is essential for polysialylation. Glycoconjugate Journal 2006, 23, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.P.; Chou, K.C. Two Latest Hot Researches in Medicinal Chemistry. Curr Top Med Chem 2020, 20, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. The Latest Researches of Enzyme Inhibition and Multi-Target Drug Predictors in Medicinal Chemistry. Med Chem 2019, 15, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Wang, X.; He, F. Promotion of Cell Migration by Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM) Is Enhanced by PSA in a Polysialyltransferase-Specific Manner. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkashef, S.M.; Allison, S.J.; Sadiq, M.; Basheer, H.A.; Morais, G.R.; Loadman, P.M.; Pors, K.; Falconer, R.A. Polysialic acid sus- tains cancer cell survival and migratory capacity in a hypoxic environment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Sutherland, M.; Springett, B.R.; Freiberger, F.; Morais, G.R.; Loadman, P.R.; Errington, R.J.; Smith, P.J.; Fu- kuda, M.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of polysialyltransferase ST8SiaII modulates tumour cell migration. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, G.; Cheng, Y.B.; Qi, X.; Geng, M.Y. Polysialylation promotes neural cell adhesion molecule-mediated cell migration in a fibroblast growth factor receptor-dependent manner, but independent of adhesion capability. Glycobiology 2011, 21, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.X.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, B.; Liao, S.M.; Zhou, F.; Huang, J.M.; Chen, D. ; Troy, II F. A.; Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B. The inhibition of polysialyltranseferase st8siaiv through heparin binding to polysialyltransferase domain (PSTD). 2019, 15, 486–495. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B. The Graphical Studies of the Major Molecular Interactions for Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM) Polysialylation by Incorporating Wenxiang Diagram into NMR Spectroscopy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.P.; Chen, D.; Liao, S.; Huang, R.B. Recent Progresses in Studying Helix-Helix Interactions in Proteins by Incorporating the Wenxiang Diagram into the NMR Spectroscopy. Curr Top Med Chem 2016, 16, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. The disposition of the LZCC protein residues in wenxiang diagram provides new insights into the protein-protein interaction mechanism. J Theor Biol 2011, 284, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, K.-C. The Significant and Profound Impacts of Chou’s “wenxiang” Diagram. Voice of the Publisher 2020, 06, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Lin, W.-Z.; Xiao, X. Wenxiang: a web-server for drawing wenxiang diagrams. Natural Science 2011, 03, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babikian, V.L.; Kase, C.S.; Pessin, M.S.; Norrving, B.; Gorelick, P.B. Intracerebral hemorrhage in stroke patients anticoagulated with heparin. Stroke. 1989, 20, 1500–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Liao, S.M.; Liu, X.H.; Liang, S.J.; Huang, J.; Lin, M.; Meng, L.; Wang, Q.Y.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. The NMR studies of CMP inhibition of polysialylation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2023, 38, 2248411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnle, A.; Veelken, R.; Galuska, C.E.; Saftenberger, M.; Verleih, M.; Schuppe, H.C.; Rudlo, S.; Kunz, C.; Galuska, S.P. Polysialic acid interacts with lactoferrin and supports its activity to inhibit the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Carbohydrate Polymer 2019, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, J.L.; Hunter, H.N.; Vogel, H.J. Lactoferricin: a lactoferrin-derived peptide with antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor and immunological properties. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 2588–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KANG, J.H.; LEE, M.K.; KIM, K.L.; HAHM, K.S. Structure-biological activity relationships of 11-residue highly basic peptide segment of bovine lactoferrin. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1996, 48, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, W.; Takase, M.; Yamauchi, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Kawase, K.; Tomita, M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1121, 130–136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.I.; Reglero, A.; Rodriguez-Aparicio, L.B.; Luengo, J.M. In vitro synthesis of colominic acid by membrane-bound sialyltransferase of Escherichia coli K-235. Kinetic properties of this enzyme and inhibition by CMP and other cytidine nucleotides. Eur J Biochem 1989, 178, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Piai, A.; Chen, W.; Xia, K.; Chou, J.J. Structure determination protocol for transmembrane domain oligomers. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 2483–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, J.R.; Zhou, G.P.; Zweckstetter, M.; Rigby, A.C.; Chou, J.J. Rapid and accurate structure determination of coiled-coil domains using NMR dipolar couplings: application to cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ialpha. Protein Sci 2005, 14, 2421–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.K.; Zhou, G.P.; Kupferman, J.; Surks, H.K.; Christensen, E.N.; Chou, J.J.; Mendelsohn, M.E.; Rigby, A.C. Probing the interaction between the coiled coil leucine zipper of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ialpha and the C terminus of the myosin binding subunit of the myosin light chain phosphatase. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 32860–32869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, M.J.; Shih, W.M.; Harrison, S.C.; Chou, J.J. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature 2011, 476, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OuYang, B.; Xie, S.; Berardi, M.J.; Zhao, X.; Dev, J.; Yu, W.; Sun, B.; Chou, J.J. Unusual architecture of the p7 channel from hepatitis C virus. Nature 2013, 498, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenoid, K.; Dong, Y.; Cao, C.; Cui, T.; Sancak, Y.; Markhard, A.L.; Grabarek, Z.; Kong, L.; Liu, Z.; Ouyang, B.; Cong, Y.; Mootha, V.K.; Chou, J.J. Architecture of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 2016, 533, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; OuYang, B.; Chou, J.J. Critical Effect of the Detergent:Protein Ratio on the Formation of the Hepatitis C Virus p7 Channel. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3834–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Fu, T.M.; Cruz, A.C.; Sengupta, P.; Thomas, S.K.; Wang, S.; Siegel, R.M.; Wu, H.; Chou, J.J. Structural Basis and Functional Role of Intramembrane Trimerization of the Fas/CD95 Death Receptor. Mol Cell 2016, 61, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, P.R.; Poluri, K.M.; Sepuru, K.M.; Rajarathnam, K. Characterizing protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions using solution NMR spectroscopy. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1229, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorndahl, T.C.; Zhou, G.P.; Liu, X.; Perez-Pineiro, R.; Semenchenko, V.; Saleem, F.; Acharya, S.; Bujold, A.; Sobsey, C.A.; Wishart, D.S. Detailed biophysical characterization of the acid-induced PrP(c) to PrP(beta) conversion process. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaynberg, J.; Qin, J. Weak protein-protein interactions as probed by NMR spectroscopy. Trends Biotechnol 2006, 24, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Yoo, D.g. , Rada, B. Michelle Kahlenberg, J.; Bridges Jr, S.L.; Oni, O.; Huang, H.; Stecenko, A.; Rada, B. Systemic levels of anti-PAD4 autoantibodies correlate with airway obstruction in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2019, 18, 636–645. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, D.G.; Winn, M.; Pang, L.; Moskowitz, S.M.; Malech, H.L.; Leto, T.L.; et al. Release of cystic brosis airway in"ammatory markers from Pseudomonas aeruginosa-stimulated human neutrophils involves NADPH oxidase-dependent extracellular DNA trap for- mation. J Immunol 2014, 192, 4728–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.G.; Floyd, M.; Winn, M.; Moskowitz, S.M.; Rada, B. NET formation induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic !brosis isolates measured as release of myeloperoxidase-DNA and neutrophil elastase-DNA complexes. Immunol Lett 2014, 160, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzenreiter, R.; Kienberger, F.; Marcos, V.; Schilcher, K.; Krautgartner, W.D.; Obermayer, A.; et al. Ultrastructural characterization of cystic fibrosis sputum using atomic force and scanning electron microscopy. J Cyst Fibros 2012, 11, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papayannopoulos, V.; Staab, D.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil elastase enhances sputum solubilization in cystic !brosis patients receiving DNase therapy. PLoS One 2011, 6, e28526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Li, M.; Lindberg, M.R.; Kennett, M.J.; Xiong, N.; Wang, Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010, 207, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Stadler, S.; Correll, S.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Hayama, R.; Leonelli, L.; Han, H.; Grigoryev, S.A.; Allis, C.D. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009, 184, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, N.; Radic, M. Citrullination of autoantigens implicates NETosis in the induction of autoimmunity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014, 73, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Hayes, C.P.; Buac, K.; Yoo, D.G.; Rada, B. Pseudogout-associated in"ammatory calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate microcrystals induce formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Immunol 2013, 190, 6488–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, H.D.; Liddle, J.; Coote, J.E.; Atkinson, S.J.; Barker, M.D.; Bax, B.D.; et al. InhibitionofPAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol 2015, 11, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Ren, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, K, Wu., Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Yang, Z. and Chen, Z. Lactoferrin: A glycoprotein that plays an active role in human health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1018336. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.; Kanwar, R.; Kanwar, J. Lactoferrin and cancer in dierent cancer models. Front Biosci. 2011, 3, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzoghby, A.; Abdelmoneem, M.; Hassanin, I.; Abd Elwakil, M.; Elnaggar, M.; Mokhtar, S.; et al. Lactoferrin, a multi-functional glycoprotein: active therapeutic, drug nanocarrier & targeting ligand. Biomaterials. 2020, 263, 120355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthau, A.; Pogoutse, A.; Adamiak, P.; Moraes, T.; Schryvers, A. Bacterial receptors for host transferrin and lactoferrin: molecular mechanisms and role in host-microbe interactions. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.; Heyden, E.; Pretorius, E. The biology of lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein that can help defend against viruses and bacteria. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The CD spectra of the PSTD in the absence (red), and the presence of the mixture of CMP-Sia and polySia (green), and the mixture of CMP-Sia, polySia and LFcinB11 (blue). The helical contents of these three CD spectra of the PSTD are 23%, 16.4%, and 14.8%, respectively.

Figure 1.

The CD spectra of the PSTD in the absence (red), and the presence of the mixture of CMP-Sia and polySia (green), and the mixture of CMP-Sia, polySia and LFcinB11 (blue). The helical contents of these three CD spectra of the PSTD are 23%, 16.4%, and 14.8%, respectively.

Figure 2.

The overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the 2mM PSTD in the absence and the presence of 20uM LFcinB11 (A), and 40uM LFcinB11 (B), and 60uM LFcinB11 (C) and 80uM LFcinB11, respectively.

Figure 2.

The overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the 2mM PSTD in the absence and the presence of 20uM LFcinB11 (A), and 40uM LFcinB11 (B), and 60uM LFcinB11 (C) and 80uM LFcinB11, respectively.

Figure 3.

Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when the PSTD interacted with 20uM LFcinB11 (blue), 40uM LFcinB11 (orange), 60uM LFcinB11 (gray), and 1mM CMP-Sia (red), respectively (A); Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when the PSTD interacted with 20uM LFcinB11(blue), 40uM LFcinB11 (black), 60uM LFcinB11 (gray), 80uM LFcinB11 (orange), and 0.1mM polySia (red), respectively (B).

Figure 3.

Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when the PSTD interacted with 20uM LFcinB11 (blue), 40uM LFcinB11 (orange), 60uM LFcinB11 (gray), and 1mM CMP-Sia (red), respectively (A); Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when the PSTD interacted with 20uM LFcinB11(blue), 40uM LFcinB11 (black), 60uM LFcinB11 (gray), 80uM LFcinB11 (orange), and 0.1mM polySia (red), respectively (B).

Figure 4.

The overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 50 uM LFcin11 in the absence (black) and the presence of 50 uM polySia (red), respectively.

Figure 4.

The overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 50 uM LFcin11 in the absence (black) and the presence of 50 uM polySia (red), respectively.

Figure 5.

The Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when it interacted with 1mM CMP-Sia, 80 uM CMP, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (A); and the CSPs of the PSTD when it interacted with 0.1 mM PSA, 1mM CMP, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (B).

Figure 5.

The Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when it interacted with 1mM CMP-Sia, 80 uM CMP, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (A); and the CSPs of the PSTD when it interacted with 0.1 mM PSA, 1mM CMP, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (B).

Figure 6.

The Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when it interacted with 1mM CMP-Sia, 80 uM heparin LMWH, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (A); and the CSPs of the PSTD when it interacted with 0.1 mM PSA, 80 uM hepain LWH, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (B).

Figure 6.

The Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the PSTD when it interacted with 1mM CMP-Sia, 80 uM heparin LMWH, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (A); and the CSPs of the PSTD when it interacted with 0.1 mM PSA, 80 uM hepain LWH, and 40 uM and 60 uM LFcinB11, respectively (B).

Table 1.

The effect of different lactoferrin concentrations (20uM, 40uM, 60uM and 80uM) on chemical shift of the residues for the PSTD-LFcinB11 interaction based on the data from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Table 1.

The effect of different lactoferrin concentrations (20uM, 40uM, 60uM and 80uM) on chemical shift of the residues for the PSTD-LFcinB11 interaction based on the data from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

| LFcinB11 concentration interacted with the PSTD |

Residues in the PSTD that do not change in chemical shift |

Residues in the PSTD that changed in chemical shift |

| 20 uM |

17 residues (K248,A254,Y255,L258,R259,V260,I261,H262,A263,V264,R265,Y267,W268,L269,K272,K276,S279) |

8 residues (K246,K250,V251,R252,T253,S257,V273,I275) |

| 40 uM |

6 residues (R259,V260,I261,H262,A263,K272) |

19 residues (K246,K248,K250,V251,R252,T253,A254,Y255,S257,L258,V264,R265,Y267,W268,L269,V273,I275,R277,S279) |

| 60 uM |

3 residues (R259,V260,A263) |

22 residues |

| 80 uM |

0 residues |

25 residues |

Table 2.

The binding regions of CMP-Sia and polySia for the different ligands on the PSTD. The maximum CSPs in each binding region are compared with the maximum CSPs for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction and for the PSTD-polySia interaction, respectively. The all CSPs were obtained based on current and the previous 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiments [

23,

30].

Table 2.

The binding regions of CMP-Sia and polySia for the different ligands on the PSTD. The maximum CSPs in each binding region are compared with the maximum CSPs for the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) interaction and for the PSTD-polySia interaction, respectively. The all CSPs were obtained based on current and the previous 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiments [

23,

30].

| Ligands binding to the PSTD |

The maximum CSPs in CMP-Sia binding region (K246-L258) |

The maximum CSPs in polySia binding region (A263-R271) |

| CMP-Sia |

0.063 |

0.030 |

| polySia |

0.031 |

0.045 |

| Heparin LMWH (80 uM) |

0.087 |

0.072 |

| CMP (1mM) |

0.087 |

0.046 |

| LFcinB11 (20 uM) |

0.047 |

0.038 |

| LFcinB11 (40 uM) |

0.081 |

0.061 |

| LFcinB11 (60 uM) |

0.124 |

0.092 |

| LFcinB11 (80 uM) |

0.151 |

0.109 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).