1. Introduction

Neutrophils constitute a crucial component of the initial defense against pathogens through well-established mechanisms such as phagocytosis, oxidative burst, and degranulation [

1]. In addition to these widely recognized tactics, the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) has been more recently described as a significant aspect of this defense strategy [

2,

3].

NETs are intricate extracellular structures of DNA and proteins derived from various intracellular compartments, including the cytoplasm, granules, and nucleus [

4,

5]. These NETs-associated proteins (NAPs) are diverse, depending on the in vitro stimulus used or the pathological condition studied [

6,

7,

8]. NAPs play a crucial role in pathological states, where even minor variations in their levels can significantly impact the effect on target cells [

9].

To elucidate the role of NETs in pathophysiology, selecting methods that accurately evaluate the presence, composition, and levels of the proteins being analyzed is crucial. Various techniques, such as immunofluorescence, ELISA, and mass spectrometry, have been employed for this purpose [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, Western Blot offers several advantages, including affordability, analysis, and flexibility in antigen detection, making it suitable for studying NETs samples. Despite these advantages, there is considerable variability and essential considerations in applying Western Blot to measure NAPs. For example, choosing a reference protein with stable expression (loading control) is crucial for accurate interpretation. Although proteins like β-actin and GAPDH are widely used as reference markers in other types of samples, they have also been applied to NET samples without clear evidence of their suitability in this specific context. [

11,

14,

15,

16].

There is also considerable heterogeneity in NET processing methods. This includes minor variations, such as differences in centrifugation times or the use of enzymes to enhance yield [

17,

18,

19], as well as more impactful factors like the specific sample fraction selected for analysis. Some researchers focus exclusively on isolating the NETs, either with or without the supernatant that contains them, while others analyze the entire sample, including both the NETs and the cells that originally released them. [

14,

15,

20].

In this study, we employ a time-course analysis of NETs release to assess the relevance of GAPDH and β-actin as appropriate candidates for loading controls, and the presence of the antimicrobial molecule LL-37/hCAP18 as a widely reported NAP [

21,

22,

23], to evaluate the effectiveness of different sample isolation approaches, such as cell lysate versus NETs fractions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

We used blood samples from healthy donors who signed informed consent. INER's Ethics and Research Committee approved protocol B22-18. The study was conducted according to the international guidelines regarding ethical and biomedical research in human subjects under the WMA Declaration of Helsinki, and all data related to donors were kept anonymous.

2.2. Isolation of Peripheral Blood Neutrophils

Peripheral blood samples from three healthy donors were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) containing tubes. Neutrophil isolation was performed immediately using Polymorphprep (1114683, Serumwerk) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, blood was carefully layered onto Polymorphprep without mixing. After centrifugation for 30 minutes at 20°C and 500 × g, the supernatant and the upper layer containing mononuclear cells were removed, leaving the lower layer with the neutrophils. The remaining erythrocytes were removed using RBC Lysis Buffer. Neutrophil viability was assessed using trypan blue staining.

2.3. Flow Cytometry for Neutrophil Quality Assessment

For the quality of sample evaluation, 4 × 10

5 cells from each donor were stained and assessed by flow cytometry using the BD FACSAria II analyzer (BD Bioscience, Germany). The specific antibodies used were as follows: CD66b-FITC (Biolegend, 305103), CD11b-PE (Biolegend, 101207), and CD16-APC (Biolegend, 302012) [

24]. After 45 minutes of staining in the dark, the cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 300 μL buffer. A minimum of 20,000 events were analyzed. Neutrophils were identified as CD11b+, CD16+, and CD66b+ cells.

2.4. Neutrophil Cell Culture

Neutrophils from each donor were suspended in serum-free RPMI (Gibco, 11835-030). 7.5 × 106 cells were seeded into 10 cm plates for Western blot experiments, and for immunofluorescence experiments, 4.8 × 105 neutrophils were attached on coverslips. Cell cultures were preincubated for 30 minutes at 37°C to allow for adherence (Time 0), followed by stimulation with 20 nM PMA (Sigma P1585) for 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours.

2.5. Western Blot Assay

At the end of each stimulation time, 40 U/mL of DNase I (Invitrogen, 18047-019) was added to the cells cultured in 10 cm plates and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C, and then the medium was recovered. To precipitate the proteins from conditioned media, four parts of acetone were added, and the samples were incubated overnight at -20°C and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The acetone was decanted, the residual solvent evaporated at room temperature and the pellet resuspended in RIPA (Sigma, R0278) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Calbiochem 539137). Plate-anchored cells were scraped in RIPA lysis buffer plus protease inhibitors to obtain the lysates. Thirty micrograms of NETs supernatants and cellular lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, blocked with 5% nonfat milk diluted in PBS for one hour. Antibodies against LL-37/hCAP18 (Santa Cruz sc-166770, 1:1000 dilution), β-actin (Genetex gtx109639), and GAPDH (Genetex gtx28245, 1:10000 dilution) were used and incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with their respective horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 62-6520 and 65-6120, both diluted 1:15000) for one hour at room temperature. Protein detection was performed with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific, 34095) in a chemiluminescence imaging system (Chemidoc XRS, Bio-Rad).

2.6. Immunofluorescence

At the end of each stimulation time, 1 x 104 cells were seeded on coverslips and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature with agitation. Subsequently, the cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with Universal Blocking Reagent (Biogenex, HK085-5K) for 30 minutes. After blocking, cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with an MPO-antibody (Santa Cruz sc-52707, 1:100 dilution) to detect this protein component of NETs. Following this, they were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit, DyLight 549 Biocare FDR549C, 1:500 dilution). Finally, neutrophils were stained with Hoechst 33342 for 5 minutes (Invitrogen, R37605), and ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, P36970) was applied to each coverslip. The samples were observed and photographed with an inverted Olympus IX-81 fluorescence microscope.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data presented represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 9.3.1 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), with results displayed as arithmetic means ± SD. Differences between groups for multiple comparisons were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett post-tests. Statistical significance was set at p ≤0.05.

3. Results

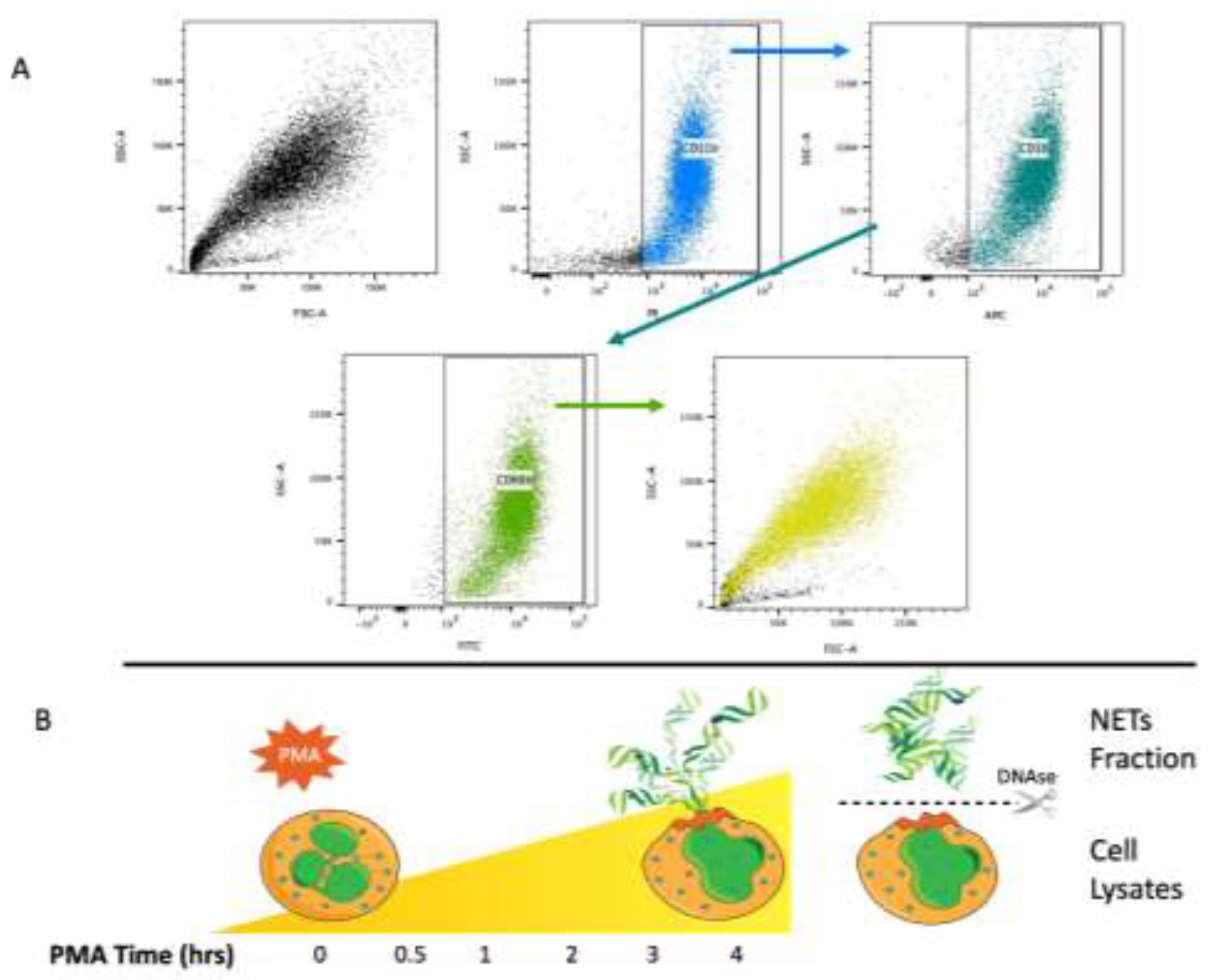

3.1. Sample Processing

We obtained neutrophils from three healthy donors, with viability assessed by trypan blue exclusion at over 95% after isolation. The neutrophil phenotype (CD11b+, CD16+, and CD66b+) was verified by FACS according to the gating strategy shown in

Figure 1a.

Figure 1b illustrates the sample fraction strategy to analyze NAPs after cellular stimulation with PMA which consisted of supernatant protein recovery after DNAse treatment at different time intervals, as shown in the scheme (

Figure 1b).

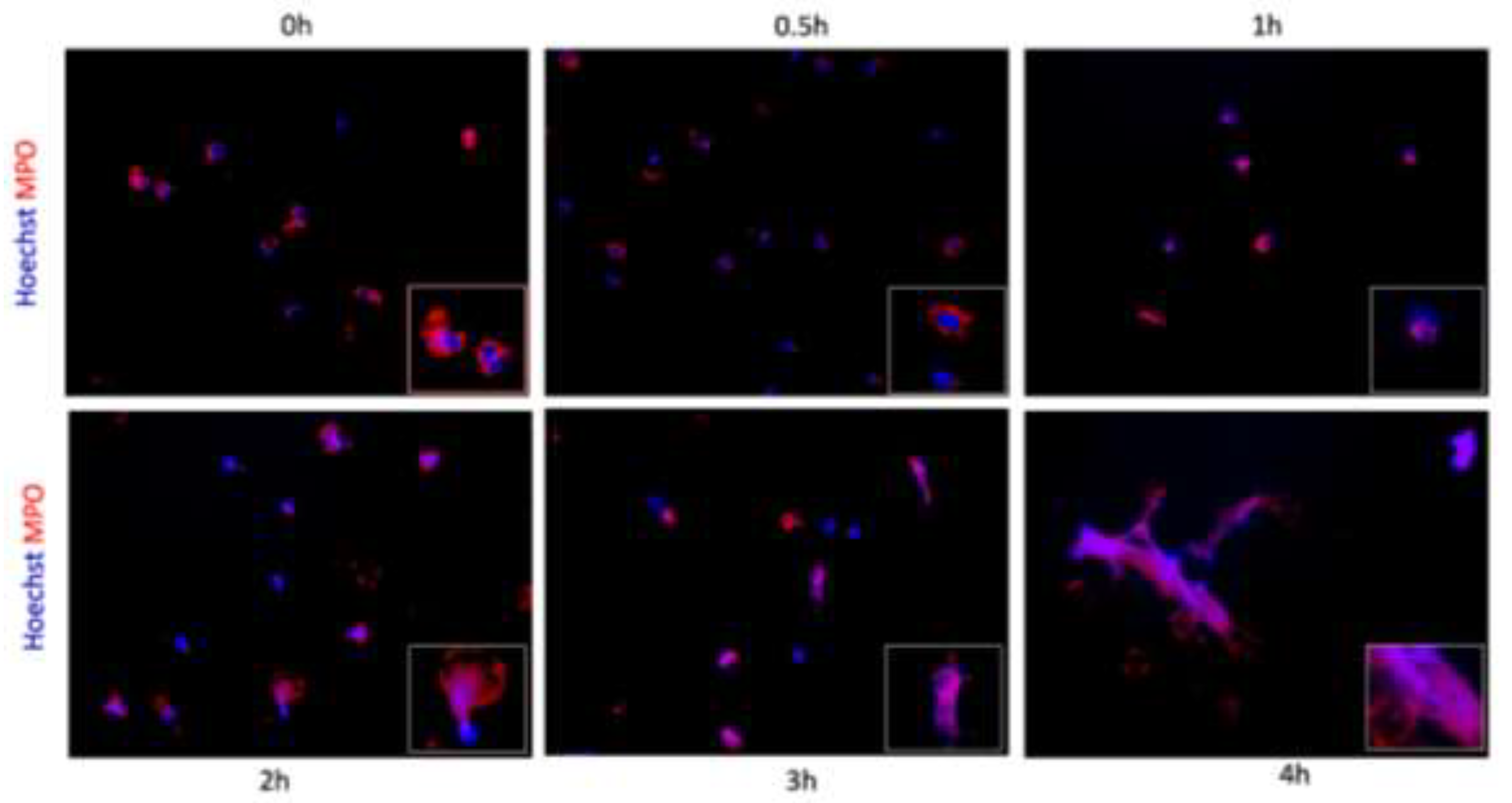

3.2. NETs Release Verification

To validate the presence of NETs, MPO protein was detected with specific antibodies by immunofluorescence on cells grown on coverslips. Hoechst was employed to visualize the DNA framework. At the initial time

, MPO was predominantly located in the cytoplasm, while the DNA-intercalating dye revealed the characteristic lobed nucleus (

Figure 2a). Over time, as illustrated in

Figure 2b-c, there was a notable loss of the classical segmentation, with the double staining becoming moderately visible within the cells and exhibiting a gradual increase over time, as depicted in

Figure 2d-e. Cell extrusion was observed, and at the final time point, fibers were seen, still anchored to cells or their remnants, and both MPO (protein) and Hoechst (DNA) staining were shown (

Figure 2f).

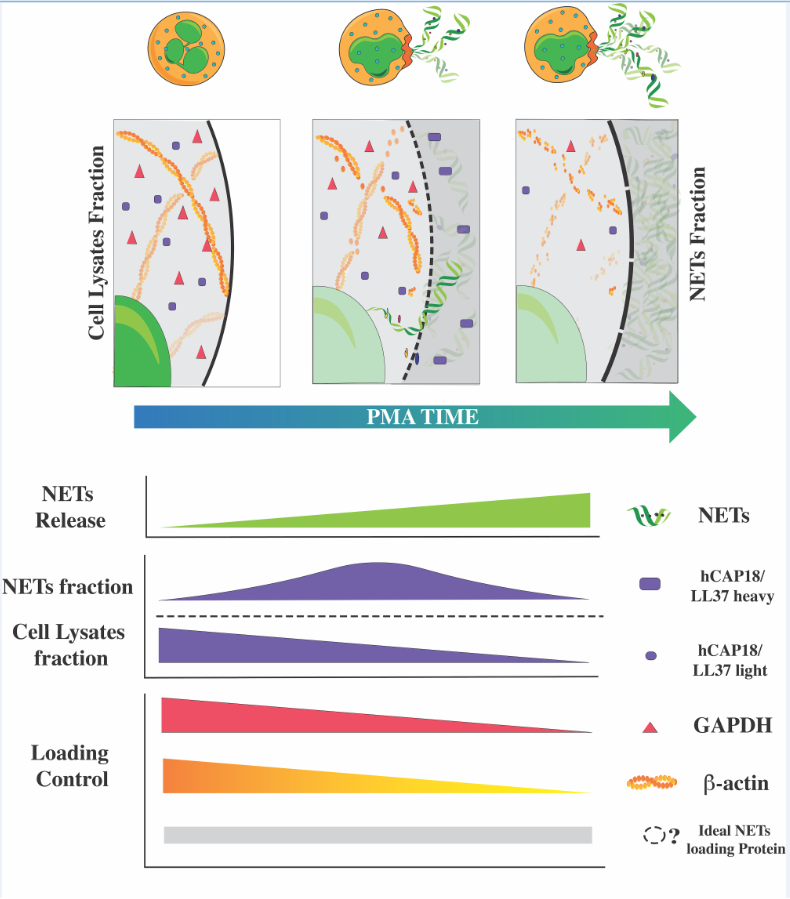

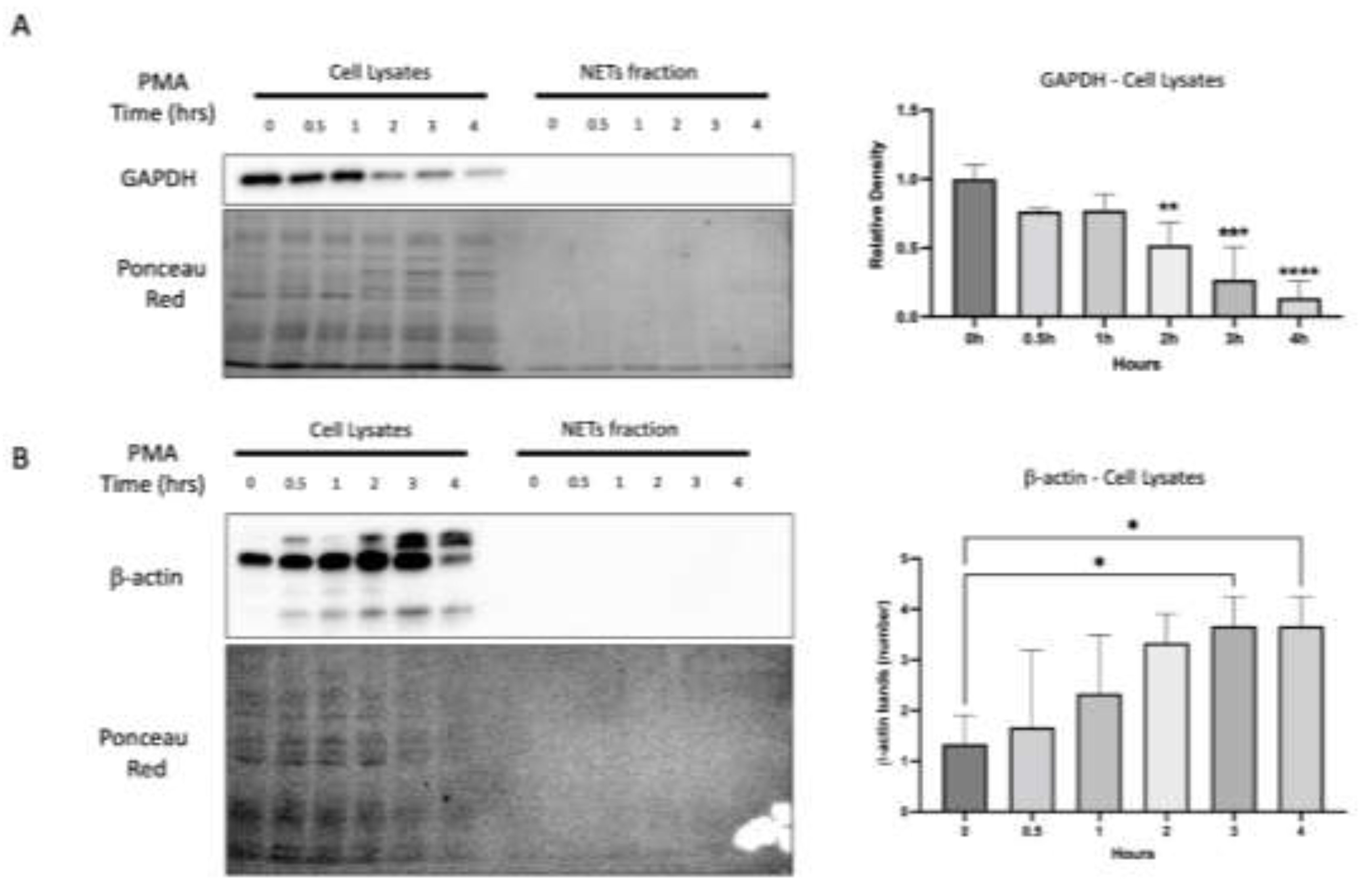

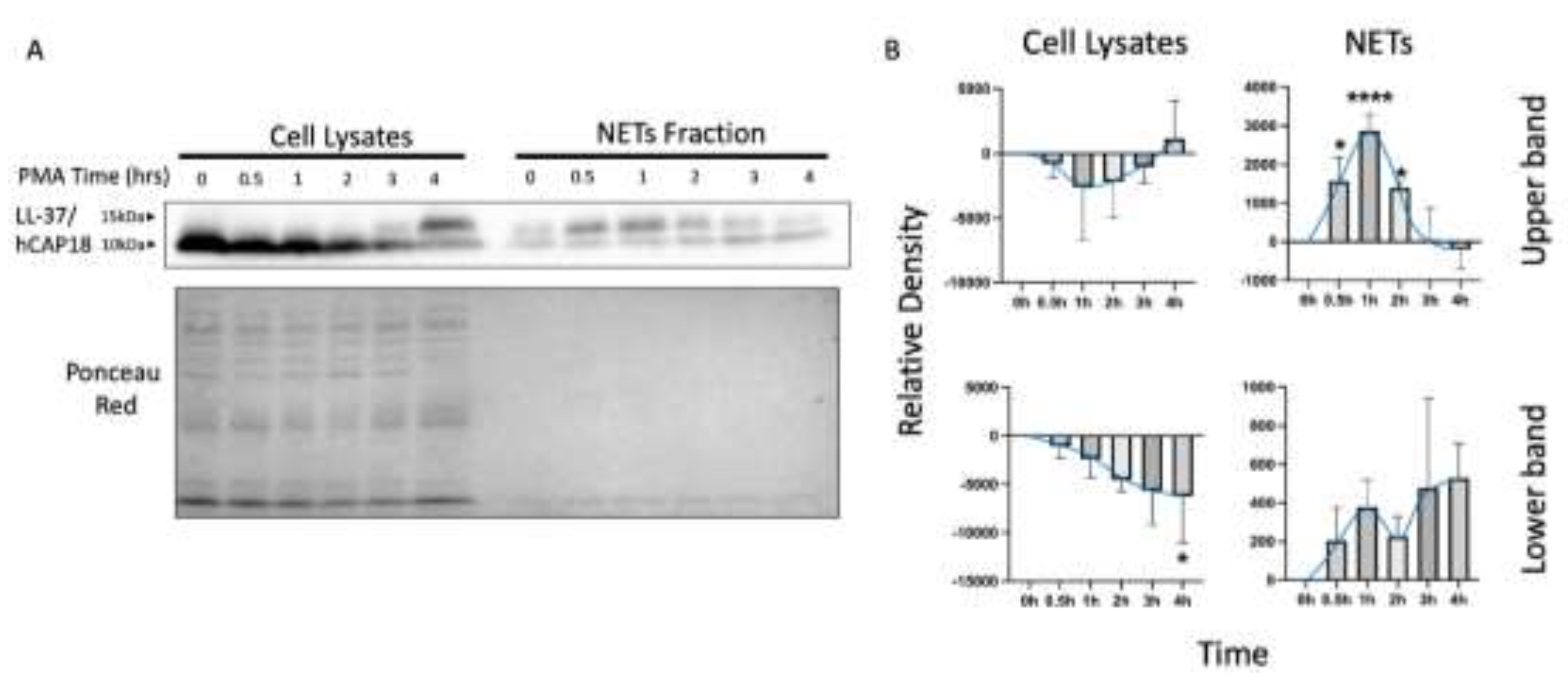

3.3. Loading Control and NETs-Associated Protein (NAPs) Assessment

WB represents an affordable alternative for determining protein levels. Nevertheless, load controls that exhibit no variations are essential for accurately interpreting the results. Considering those above, we conducted a Western blot to analyze NAPs from neutrophils stimulated with PMA (

Figure 1b), testing glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin as loading controls.

As shown in

Figure 3a, the expression of GAPDH remained unaltered in the samples of cell lysates throughout the initial phase of the PMA time course (0, 0.5, and 1 hour). However, at 2 hours, a notable decline in GAPDH was observed, becoming increasingly pronounced after 3 and 4 hours of PMA stimulation. As expected, GAPDH was not detected in the NETs fraction (

Figure 3a).

Regarding β-actin, we observed that the protein bands increased over time, starting at 3 hours of the PMA stimulus and persisting for the subsequent hour. In the NETs fraction, β-actin was not observed (

Figure 3b). These results conclude that we cannot use GAPDH or B-actin as loading controls. Therefore, we decided to use Ponceau red staining to verify the presence and homogeneity of protein load. The Ponceau red staining revealed a homogeneous protein load in most of the samples, and although in some cases, such as samples of 3 hours in

Figure 3b where a lower amount of protein is observed, this does not affect the result since it is the sample with a higher level of B-actin.

Finally, we analyzed LL-37/hCAP18 as a NAP due to the distinct reported localization: intracellularly within granules or extracellularly associated with NETs. Two bands were observed on the blot of LL-37/hCAP18, one of approximately 14 kDa and a smaller one of 10 kDa (

Figure 4a). The intensity of the upper bands shows a different temporal dynamic than the lower bands, both in cell lysate samples and in the supernatants containing NETs (

Figure 4a). The LL-37/hCAP18 lower band in the cell lysates exhibits a discernible tendency towards a decrease; however, this only reaches statistical significance at 4 hours of PMA stimulation. Concurrently, the upper band (~14 kDa) increases without reaching significance (

Figure 4b). In the case of NETs samples, the upper band of LL-37/hCAP18 increases at 0.5 h, reaching a peak at the 1-hour interval and exhibiting a gradual decline. The ~10 kDa protein band of LL-37/hCAP18 tended to increase at the end of the time course, although this was not statistically significant (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

During NETs release, atypical changes occur: the cytoskeleton disassembles, mitochondria become permeable, the nuclear envelope breaks down, and chromatin decondenses. Furthermore, part of the intracellular content externalizes, with some proteins being carried out with the NETs, while others remain inside the cell. This reflects the unique nature of the studied samples, complicating the correct protein analysis.

It is common practice to use reference proteins involved in key metabolic pathways or cytoskeleton's structural elements, such as GAPDH and β-actin. However, neither of these proteins remains static, so it is prudent to evaluate reference markers. Our system found a significant difference, showing a lower amount of GAPDH after two hours of treatment with PMA. GAPDH was initially identified as a protein with a limited function and localization, and due to its characteristics, its use as a loading control is often accepted. However, recent discoveries show it is a complex protein found in unexpected locations, such as the plasma membrane, mitochondria, and the nucleus [

25]. Additionally, beyond its variability in location, GAPDH has been found to undergo modifications and play different roles in disease. For example, in COVID-19, GAPDH was observed to inhibit NETs, which aligns with the inverse correlation we observed [

26]. Our results suggest that GAPDH might not be an adequate normalization protein for studying the NETs release process. On the other hand, when using β-actin as a loading control, we observed multiple smaller bands that increased over time, possibly due to the disassembly and subsequent degradation described in the literature [

27,

28]. The search for a protein to serve as a loading control for NET samples can be challenging due to the variability in the composition of extracellular traps. Other methods to verify Western blot loading could be considered, such as Ponceau Red staining, which we used in this work or stain-free methods.

Assessment of LL-37/hCAP18 revealed that its distribution is not homogeneous between the NETs and the intracellular fraction. First, the upper band, approximately 14 kDa in size and consistent with the reported weight of the precursor protein [

29], appeared only in the NETs fraction. Second, the lower band, around 10 kDa, which may correspond to the active form of LL-37/hCAP18, was exclusively present in the intracellular fraction, showing apparent differences compared to the NETs fraction. Although we expected the active form at 5 kDa, we observed a 10 kDa band, which has been reported in other studies [

30]. There are still uncertainties regarding the regulation, synthesis, transport, and activation of hCAP18/LL-37 during NETs release. However, what is clear is that the protein, in both identified forms, behaves differently, emphasizing the discontinuity between the intracellular space and the NETs fraction. While the exact mechanism by which cellular contents are externalized during NETs release remains unclear, the involvement of Gasdermin D in this process has been strongly suggested [

31,

32]. Its selective pore-forming capabilities, as described in other contexts, along with its ability to be regulated [

33,

34], further underscore the critical distinction between the intracellular compartment and the NETs fraction.

Finally, the release of NETs appears to be a series of intricate, sequential steps, ultimately leading to the extracellular trap release at a variable time. We employed a temporal course approach to a better understanding of how loading controls and NAPs behave throughout the process. Beyond our specific use of this method, it could also be valuable for studying the events preceding NETs release or characterizing both,early and late-stage NETs. This approach could provide an alternative view of a process whose temporality has yet to be fully clarified.

Western blotting offers specific advantages that can be harnessed in the study of NETs. It remains the backbone of protein sample analysis and characterization in many laboratories, mainly due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of setup. These attributes allowed us to perform a detailed temporal analysis, enabling the visualization of both forms of hCAP18/LL-37. Focusing on critical details such as proper loading controls and carefully separating protein fractions for reliable results is essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Miguel Negreros and Luis Felipe Flores-Suárez; Formal analysis, Miguel Negreros; Funding acquisition, Luis Felipe Flores-Suárez; Investigation, Miguel Negreros, Fernando Hernández and Fernando Morales-Hurtado; Methodology, Miguel Negreros and Fernando Hernández; Project administration, Miguel Negreros; Resources, Criselda Mendoza-Milla and Luis Felipe Flores-Suárez; Supervision, Luis Felipe Flores-Suárez; Validation, Miguel Negreros; Visualization, Miguel Negreros; Writing – original draft, Miguel Negreros; Writing – review & editing, Fernando Hernández, Criselda Mendoza-Milla, José Cisneros and Luis Felipe Flores-Suárez.

Funding

The work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT), Mexico, grant number 304041 (to L.F.F-S.). CONAHCYT had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, publishing decisions, or manuscript preparation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mayadas, T.N.; Cullere, X.; Lowell, C.A. The Multifaceted Functions of Neutrophils. Annu Rev Pathol 2014, 9, 181–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Kill Bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil Recruitment and Function in Health and Inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scieszka, D.; Lin, Y.-H.; Li, W.; Choudhury, S.; Yu, Y.; Freire, M. NETome: A Model to Decode the Human Genome and Proteome of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Sci Data 2022, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Aziz, M.; Wang, P. The Vitals of NETs. J Leukoc Biol 2021, 110, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, M.; Petretto, A.; Santucci, L.; Vaglio, A.; Pratesi, F.; Migliorini, P.; Bertelli, R.; Lavarello, C.; Bartolucci, M.; Candiano, G.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Protein Composition Is Specific for Patients with Lupus Nephritis and Includes Methyl-Oxidized Aenolase (Methionine Sulfoxide 93). Sci Rep 2019, 9, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petretto, A.; Bruschi, M.; Pratesi, F.; Croia, C.; Candiano, G.; Ghiggeri, G.; Migliorini, P. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NET) Induced by Different Stimuli: A Comparative Proteomic Analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangou, E.; Vassilopoulos, D.; Boletis, J.; Boumpas, D.T. An Emerging Role of Neutrophils and NETosis in Chronic Inflammation and Fibrosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and ANCA-Associated Vasculitides (AAV): Implications for the Pathogenesis and Treatment. Autoimmun Rev 2019, 18, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arampatzioglou, A.; Papazoglou, D.; Konstantinidis, T.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; Mitsios, A.; Angelidou, I.; Maroulakou, I.; Ritis, K.; Skendros, P. Clarithromycin Enhances the Antibacterial Activity and Wound Healing Capacity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Increasing LL-37 Load on Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilsczek, F.H.; Salina, D.; Poon, K.K.H.; Fahey, C.; Yipp, B.G.; Sibley, C.D.; Robbins, S.M.; Green, F.H.Y.; Surette, M.G.; Sugai, M.; et al. A Novel Mechanism of Rapid Nuclear Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation in Response to Staphylococcus Aureus. J Immunol 2010, 185, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, L.-L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Peng, H.-Y.; Chen, M.; Zhao, M.-H. Autophagy Is Induced by Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Abs and Promotes Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Formation. Innate Immun 2016, 22, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sha, L.-L.; Ma, T.-T.; Zhang, L.-X.; Chen, M.; Zhao, M.-H. Circulating Level of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Is Not a Useful Biomarker for Assessing Disease Activity in Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0148197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rycyk-Bojarzynska, A.; Kasztelan-Szczerbinska, B.; Cichoz-Lach, H.; Surdacka, A.; Rolinski, J. Neutrophil PAD4 Expression and Its Pivotal Role in Assessment of Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, M.; Iommelli, F.; De Rosa, V.; Carriero, M.V.; Miceli, R.; Camerlingo, R.; Di Minno, G.; Del Vecchio, S. Integrin-Dependent Cell Adhesion to Neutrophil Extracellular Traps through Engagement of Fibronectin in Neutrophil-like Cells. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Gan, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Hao, N.; Yuan, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M. Lung Cancer Cells Release High Mobility Group Box 1 and Promote the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe-Kusunoki, K.; Abe, N.; Nakazawa, D.; Karino, K.; Hattanda, F.; Fujieda, Y.; Nishio, S.; Yasuda, S.; Ishizu, A.; Atsumi, T. A Case Report Dysregulated Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in a Patient with Propylthiouracil-Induced Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. Medicine 2019, 98, e15328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Gonzalez, R.; Martínez-Colón, G.J.; Smith, A.J.; Smith, C.K.; Ballinger, M.N.; Xia, M.; Murray, S.; Kaplan, M.J.; Yanik, G.A.; Moore, B.B. Inhibition of Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation after Stem Cell Transplant by Prostaglandin E2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 193, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlenberg, J.M.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Smith, C.K.; Kaplan, M.J. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap-Associated Protein Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Enhanced in Lupus Macrophages. J Immunol 2013, 190, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInturff, A.M.; Cody, M.J.; Elliott, E.A.; Glenn, J.W.; Rowley, J.W.; Rondina, M.T.; Yost, C.C. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Regulates Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation via Induction of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 α. Blood 2012, 120, 3118–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, F.D.; Ochsenbauer, C.; Wira, C.R.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Prevent HIV Infection in the Female Genital Tract. Mucosal Immunol 2018, 11, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; Völlger, L.; Berends, E.T.M.; Molhoek, E.M.; Stapels, D.A.C.; Midon, M.; Friães, A.; Pingoud, A.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; Gallo, R.L.; et al. Novel Role of the Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 in the Protection of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps against Degradation by Bacterial Nucleases. J Innate Immun 2014, 6, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, B. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps May Contribute to Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Anti-MDA5 Autoantibody Positive Dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 2018, 37, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lande, R.; Ganguly, D.; Facchinetti, V.; Frasca, L.; Conrad, C.; Gregorio, J.; Meller, S.; Chamilos, G.; Sebasigari, R.; Riccieri, V.; et al. Neutrophils Activate Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells by Releasing Self-DNA-Peptide Complexes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3, 73ra19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakschevitz, F.S.; Hassanpour, S.; Rubin, A.; Fine, N.; Sun, C.; Glogauer, M. Identification of Neutrophil Surface Marker Changes in Health and Inflammation Using High-Throughput Screening Flow Cytometry. Exp Cell Res 2016, 342, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirover, M.A. Subcellular Dynamics of Multifunctional Protein Regulation: Mechanisms of GAPDH Intracellular Translocation. J Cell Biochem 2012, 113, 2193–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hook, J.S.; Ding, Q.; Xiao, X.; Chung, S.S.; Mettlen, M.; Xu, L.; Moreland, J.G.; Agathocleous, M. Neutrophil Metabolomics in Severe COVID-19 Reveal GAPDH as a Suppressor of Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, K.D.; Goosmann, C.; Lubojemska, A.; Zychlinsky, A.; Papayannopoulos, V. A Myeloperoxidase-Containing Complex Regulates Neutrophil Elastase Release and Actin Dynamics during NETosis. Cell Rep 2014, 8, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, H.R.; Wong, S.L.; Qiu, R.; Kittisopikul, M.; Vahabikashi, A.; Goldman, A.E.; Goldman, R.D.; Wagner, D.D.; Waterman, C.M. NETosis Proceeds by Cytoskeleton and Endomembrane Disassembly and PAD4-Mediated Chromatin Decondensation and Nuclear Envelope Rupture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 7326–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Ohtake, T.; Dorschner, R.A.; Gallo, R.L. Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptides Are Expressed in Salivary Glands and Saliva. J Dent Res 2002, 81, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geitani, R.; Moubareck, C.A.; Costes, F.; Marti, L.; Dupuis, G.; Sarkis, D.K.; Touqui, L. Bactericidal Effects and Stability of LL-37 and CAMA in the Presence of Human Lung Epithelial Cells. Microbes Infect 2022, 24, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, G.; Choidas, A.; Burn, G.L.; Habenberger, P.; Di Lucrezia, R.; Kordes, S.; Menninger, S.; Eickhoff, J.; Nussbaumer, P.; Klebl, B.; et al. Gasdermin D Plays a Vital Role in the Generation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Sci Immunol 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Su, Q.; Ye, K.; Chen, C.; Li, G.; Song, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. GSDMD-Dependent Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Macrophage-to-Myofibroblast Transition and Renal Fibrosis in Obstructive Nephropathy. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Cruz Garcia, A.B.; Schnur, K.P.; Malik, A.B.; Mo, G.C.H. Gasdermin D Pores Are Dynamically Regulated by Local Phosphoinositide Circuitry. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, Z.; Magupalli, V.G.; Pablo, J.L.; Dong, Y.; Vora, S.M.; Wang, L.; Fu, T.-M.; Jacobson, M.P.; Greka, A.; et al. Gasdermin D Pore Structure Reveals Preferential Release of Mature Interleukin-1. Nature 2021, 593, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).