Introduction

Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells in circulation and play a critical role in the inflammatory response[

1]. In recent years, they have also been recognized as a component of the immune system involved in mediating tumor progression[

2,

3]. However, the exact role of neutrophils in malignancies remains controversial, as they have been described to exert both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic effects[

4]. Recent studies have identified a novel subset of neutrophils, C5aR1-positive neutrophils, which drive glycolysis in breast cancer[

5]. While neutrophils have been reported to promote hepatocellular damage in acute senescence models, whether neutrophils themselves undergo senescence and if senescent neutrophils play a role in tumor progression remains unknown.

As part of the glycolytic process, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzes a specific type of hydroxycarboxylic acid. It is produced from pyruvate during anaerobic or aerobic conditions[

6]. L-lactate and D-lactate are two enantiomers of lactate present in the human body. The former is predominantly found in human serum, while the latter originates from dietary intake. On one hand, lactate regulates intracellular and extracellular metabolic processes throughout the body[

7]. On the other hand, it exerts various biological effects, including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and gene expression regulation, through receptors expressed in different cells and tissues[

8]. Histones undergo post-translational modifications at both the C-terminal and the projecting N-terminal tails, playing a critical role in histone modifications. Lactate promotes the epigenetic regulation of genes by lactylating lysine residues on histones[

9]. It has been identified as the precursor for histone lysine lactylation, highlighting the crucial role of lactylation in immunoregulation and the maintenance of homeostasis[

10,

11].

Ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, plays a significant role in breast cancer[

12,

13]. It is implicated in both the suppression and progression of the disease, depending on the cellular context and tumor microenvironment[

14]. On one hand, ferroptosis can inhibit breast cancer growth by inducing cell death in cancer cells resistant to conventional therapies[

15]. On the other hand, certain breast cancer subtypes exploit antioxidant systems, such as the GPX4-glutathione axis, to evade ferroptosis and enhance their survival[

15]. Emerging evidence suggests that targeting ferroptosis-related pathways could offer novel therapeutic strategies for breast cancer, particularly for drug-resistant and aggressive forms of the breast cancer[

16,

17]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the regulatory mechanisms underlying the correlation between neutrophils with breast cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

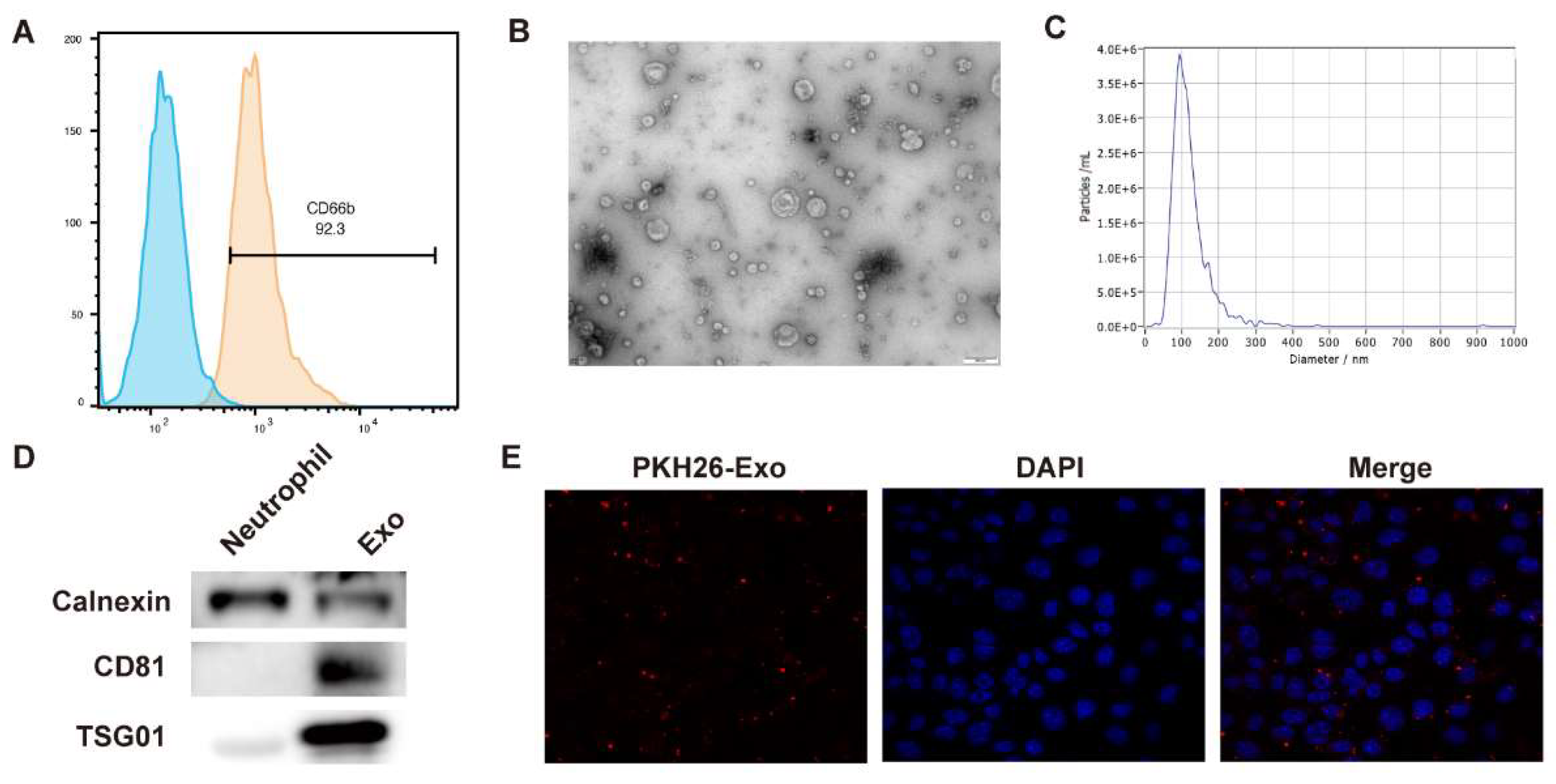

Isolation and Identification of Neutrophils

Neutrophils were isolated from human peripheral blood using a specific kit (P9402, Solarbio, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After isolation, the neutrophils were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. The expression of surface biomarkers was assessed using a CD66b antibody. For cell transfection, siRNAs were synthesized by Qingke (Beijing, China). The siRNAs and vectors were mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 and incubated with cancer cells for 48 hours. The cells were then harvested for further analysis.

Exosome Isolation and Labeling

The culture medium of neutrophils was collected, and exosomes were isolated from the supernatant using ultracentrifugation. Briefly, the cell culture supernatant underwent sequential centrifugation at 300×g for 10 minutes, 2,000×g for 10 minutes, and 10,000×g for 30 minutes, followed by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter to remove cells, dead cells, and debris. For exosome purification, the supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 70 minutes, washed with PBS, and then centrifuged again at 100,000×g for 70 minutes using an Ultracentrifuge (Beckman, Germany). The size of the exosomes was determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Protein expression of TSG101 and CD81 was evaluated by Western blot analysis. To study exosome uptake, the exosomes were labeled with PKH26 (Sigma, USA) and incubated with breast cancer cells for 24 hours. Imaging was performed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

qPCR Assay

Total RNA was extracted from fresh atrial tissue using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was then reverse transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using a First-strand Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan). Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using SYBR Green Premix (Takara, Japan) for semi-quantification. The relative expression of target genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with β-actin serving as the internal control.

Western Blot Assay

Neutrophils were lysed using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (Solarbio, China) and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo, USA). Protein concentration was measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, followed by blocking with 5% non-fat milk. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4°C with specific primary antibodies targeting TSG101 and CD81. After washing, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies and ECL reagent, and the signals were captured using a Tanon imaging system.

In Vitro Cell Growth

Cell viability and proliferation was measured by CCK-8 and EdU assay. For the CCK-8 assay, cancer cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. The following day, exosomes (5 µg/ml) were added to each well and incubated for 24 hours. After incubation, CCK-8 reagent (SolarBio, China) was added to each well, and the reaction was allowed to proceed. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Perkin Elmer, Germany). The Edu staining was performed using a EdU assay kit (Beyotime, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Ferroptosis Biomarkers

To detect lipid ROS, cells were incubated with C11-BODIPY at 37°C for 30 minutes. After washing with PBS, fluorescence was measured using a flow cytometry system. The total iron and Fe2+ levels were quantified using the Iron Assay Kit (ab83366, Abcam, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP experiment was conducted using a ChIP assay kit (EZ-CHIP, Millipore, USA) following the manufacture’s protocol. IN short, cancer cells were fixed in 1% formalin, lysed, and sonicated to obtain chromatins fragments. The fragments were then hatched with anti-LDHA or anti-H3K18la antibodies for 6 hours in rotation. After purification with proteinase K and RNase A, the levels of immunoprecipitated DNAs were detected by qPCR experiment.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

PGL3-basic reporter vectors containing either the wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) GPX4 promoter region were transfected into cancer cells along with siRNAs. After 24 hours, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was assessed using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, USA).

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 software. Differences between two groups or among multiple groups were assessed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni correction. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of Neutrophil-Exosomal LDHA

Neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood. The results from flow cytometry showed that isolated cells positively expressed CD66b, which is consistent with the features of neutrophils (

Figure 1A). Then, exosomes were isolated from the culture medium and identified. The TEM images indicated the sphere morphology of exosomes (

Figure 1B), and the diameter mainly distribute around 150 nm (

Figure 1C). The exosomes presented high levels of CD81 and TSG101 compared with the neutrophils, indicating the successful isolation of exosomes (

Figure 1D). The PKH26-labeled exosomes could be successfully uptake by breast cancer cells (

Figure 1E).

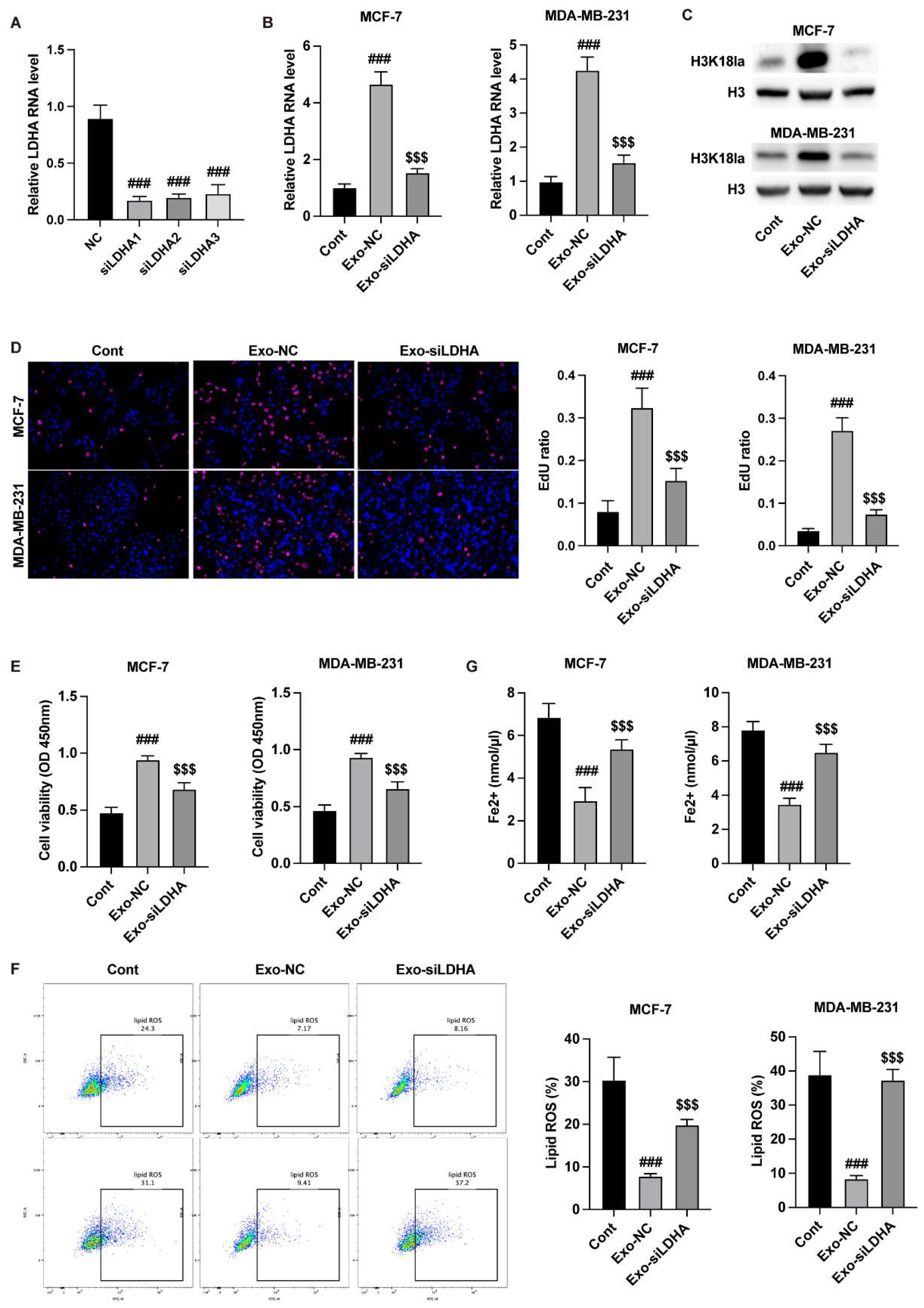

Neutrophil-Exosomes Deliver LDHA to Suppress Breast Cancer Ferroptosis

After identification of the neutrophil-exosome, we detected the delivery of LDHA by exosomes. Transfection with siLDHA in neutrophils notably reduced the level of LDHA in cells and exosomes (

Figure 2A) and the cancer cells (

Figure 2B) that incubated with exosomes. The knockdown of LDHA in exosomes reduced the H3K18la modification in breast cancer cells (

Figure 2C). Besides, the exosomes from LDHA-depleted neutrophils notably suppressed the viability and proliferation (

Figure 2D and E). The results from lipid ROS and Fe2+ detection further indicated that knockdown of LDHA in exosomes induced breast cancer cell ferroptosis (

Figure 2F and G).

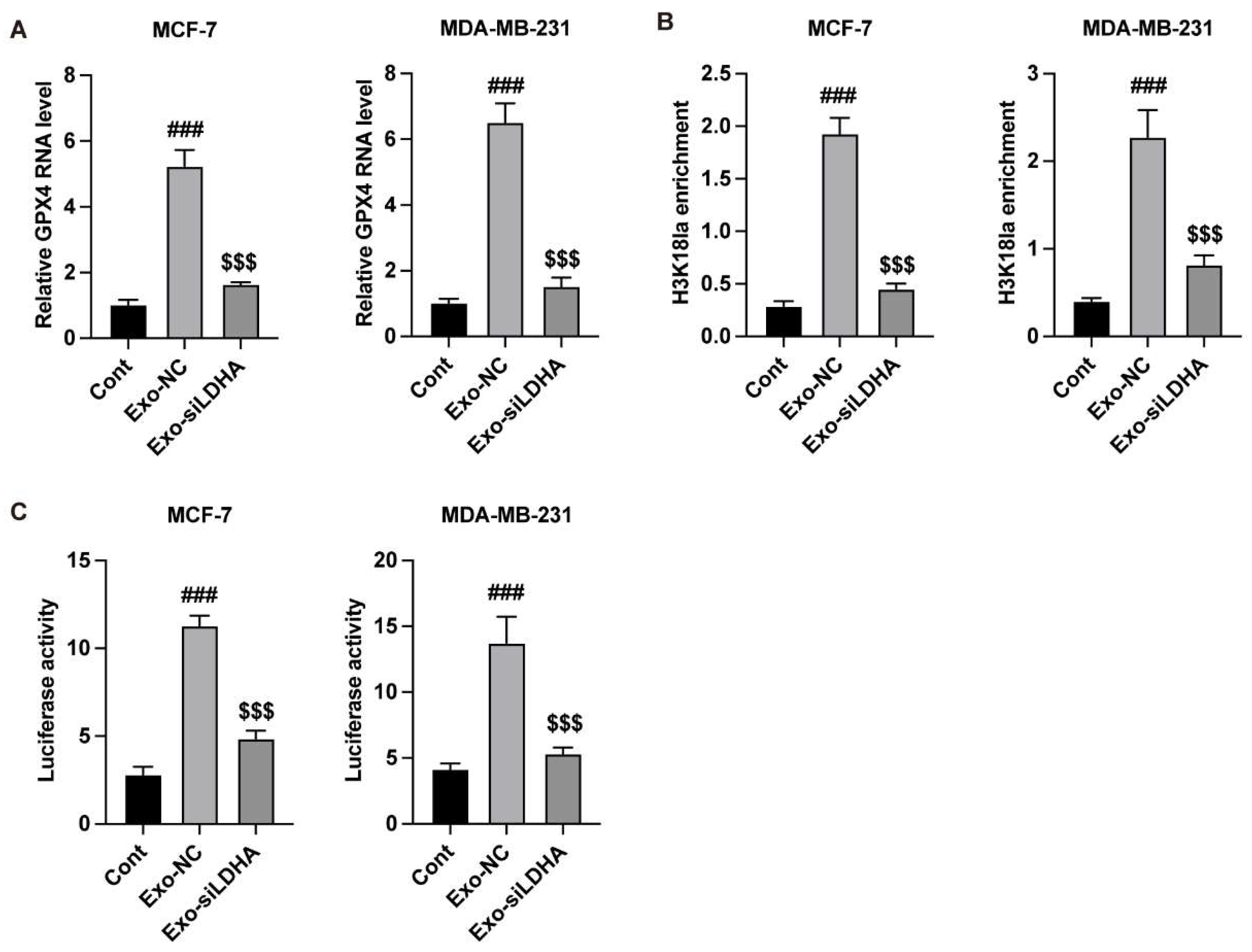

LDHA Epigenetically Regulates the Expression of GPX4 in Breast Cancer Cells

Subsequently, we analyzed the regulatory mechanism of LDHA/GPX4 axis. Transfection with siRNAs that target LDHA significantly downregulated the RNA level of LDHA in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 3A). Results from ChIP experiment indicated that LDHA directly binds with the GPX4 gene (

Figure 2B). Knockdown of LDHA deceased the enrichment of H3K18la (

Figure 3C) on GPX4 gene.

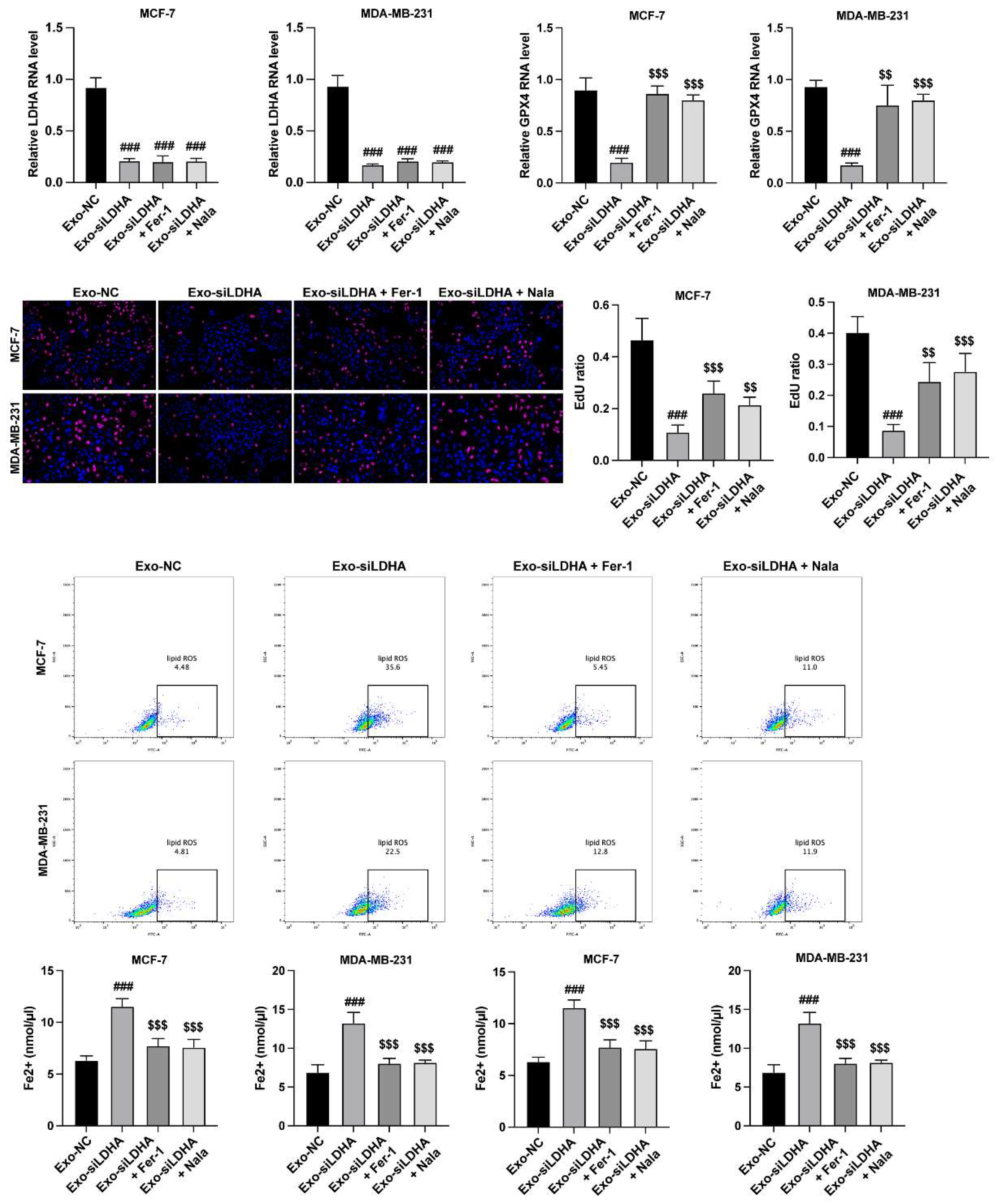

LDHA Regulates Growth and Ferroptosis of Breast Cancer Cells via GPX4

To verify the LDHA/GPX4 axis in breast cancer cells, we treated MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells with exosomes from siLDHA-transfected neutrophils, ferroptosis inhibitor (Fer-1) and lactylation enhancer (Nala). The siLDHA downregulated the RNA level of GPX4, which was recovered by Nala treatment (

Figure 4A and B). Results from CCK-8 manifested that siLDHA suppressed the viability of breast cancer cells (

Figure 4C), as well as induced ferroptosis (

Figure 4D and E). Whereas inhibition of ferroptosis and elevation of lactylation reversed these effects (

Figure 4C-E).

Discussion

Neutrophil-derived exosomes play a significant role in tumor progression by influencing various aspects of the tumor microenvironment[

18,

19]. These exosomes, which carry proteins, lipids, and RNAs, can modulate immune responses, promote angiogenesis, and enhance tumor cell proliferation and metastasis[

20]. Neutrophil exosomes have been shown to interact with tumor cells, promoting their migration, invasion, and survival through the transfer of bioactive molecules such as cytokines, chemokines, and microRNAs[

19,

21]. The release of exosomes from neutrophils, particularly in the context of chronic inflammation, contributes to the establishment of a pro-tumor microenvironment, facilitating tumor growth and metastasis[

22,

23]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms behind neutrophil-derived exosomes offers new potential targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer. In this study, we identified neutrophil-derived exosomes could deliver LDHA to breast cancer cells and facilitate the growth of cancer cells. We observed that knockdown of LDHA in neutrophils enhanced the ferroptosis of breast cancer cells, along with reduced expression of GPX4.

GPX4 is a crucial regulator of ferroptosis, functioning to convert lipid peroxides into non-toxic lipid alcohols through the use of reduced GSH[

24,

25]. The overexpression of GPX4 has been closely linked to carcinogenesis and metastasis[

26,

27], making it a promising target for cancer therapy. For instance, Zhang et al. explored various inhibitors and identified DMOCPTL, which induces GPX4 ubiquitination by directly targeting the GPX4 protein. This treatment effectively inhibited breast cancer growth and extended the survival of mice without causing significant toxicity[

16]. Additionally, it has been shown that STAT3 interacts with the DNA response elements in the GPX4 promoter region to regulate its expression in gastric cancer[

28]. The development of STAT3 inhibitors has demonstrated significant tumor growth suppression in organoid, xenograft, and patient-derived xenograft models by promoting ferroptosis[

28]. In our study, we found that knocking down LDHA in neutrophils-derived exosomes led to a reduction in GPX4 expression, resulting in the accumulation of intracellular ROS and iron. This also inhibited the growth of breast cancer cells. These findings offer new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying breast cancer pathogenesis and highlight LDHA as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer treatment.

Funding

Medical and Health Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2024KY1482).

References

- Xiong, S.; Dong, L.; Cheng, L. Neutrophils in cancer carcinogenesis and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, C.C.; Malanchi, I. Neutrophils in cancer: Heterogeneous and multifaceted. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, M.E.; Fridlender, Z.G. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019, 16, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Nepovimova, E.; Adam, V.; et al. Neutrophils in Cancer immunotherapy: Friends or foes? Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, B.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. C5aR1-positive neutrophils promote breast cancer glycolysis through WTAP-dependent m6A methylation of ENO1. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Chen, V.Z.; Backe, S.J.; et al. Structural and functional regulation of lactate dehydrogenase-A in cancer. Future Med Chem 2020, 12, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, T.; et al. Lactate dehydrogenase A: A key player in carcinogenesis and potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Med 2018, 7, 6124–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, J.A.; Winter, V.J.; Eszes, C.M.; et al. Structural basis for altered activity of M- and H-isozyme forms of human lactate dehydrogenase. Proteins 2001, 43, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvona, C.J.; Fillmore, H.L.; Nunn, P.B.; et al. The Regulation and Function of Lactate Dehydrogenase A: Therapeutic Potential in Brain Tumor. Brain Pathol 2016, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Lv, Y.; Dai, X. Lactate, histone lactylation and cancer hallmarks. Expert Rev Mol Med 2023, 25, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Histone Lactylation Boosts Reparative Gene Activation Post-Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res 2022, 131, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Nijiati, S.; Tang, L.; et al. Ferroptosis Detection: From Approaches to Applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2023, 62, e202300379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, J.H.; et al. Ferroptosis heterogeneity in triple-negative breast cancer reveals an innovative immunotherapy combination strategy. Cell Metab 2023, 35, 84–100.e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, P.; Wang, J.; et al. HLF regulates ferroptosis, development and chemoresistance of triple-negative breast cancer by activating tumor cell-macrophage crosstalk. J Hematol Oncol 2022, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; et al. Identification of a small molecule as inducer of ferroptosis and apoptosis through ubiquitination of GPX4 in triple negative breast cancer cells. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xie, R.; Cao, Y.; et al. Simvastatin induced ferroptosis for triple-negative breast cancer therapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; et al. Exosomal miRNAs from neutrophils act as accurate biomarkers for gastric cancer diagnosis. Clin Chim Acta 2024, 554, 117773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Bhagat, S.; Paul, S.; et al. Neutrophils in Cancer and Potential Therapeutic Strategies Using Neutrophil-Derived Exosomes. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zang, J.; Zhao, Z.; et al. The Advances of Neutrophil-Derived Effective Drug Delivery Systems: A Key Review of Managing Tumors and Inflammation. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 7663–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, Z.C.; Li, N.; et al. Exosomal transfer of activated neutrophil-derived lncRNA CRNDE promotes proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. Hum Mol Genet 2022, 31, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Tang, W.; Yang, M.; et al. Inflammatory tumor microenvironment responsive neutrophil exosomes-based drug delivery system for targeted glioma therapy. Biomaterials 2021, 273, 120784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y. Exosomes Derived from Immune Cells: The New Role of Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Tumor Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 6527–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gong, M.; Zhang, W.; et al. Thiostrepton induces ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through STAT3/GPX4 signalling. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chakraborty, B.; Safi, R.; et al. Dysregulated cholesterol homeostasis results in resistance to ferroptosis increasing tumorigenicity and metastasis in cancer. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Minikes, A.M.; Gao, M.; et al. Intercellular interaction dictates cancer cell ferroptosis via NF2-YAP signalling. Nature 2019, 572, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Li, H.; Lou, L.; et al. Inhibition of STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol 2022, 52, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).