Submitted:

24 March 2024

Posted:

25 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

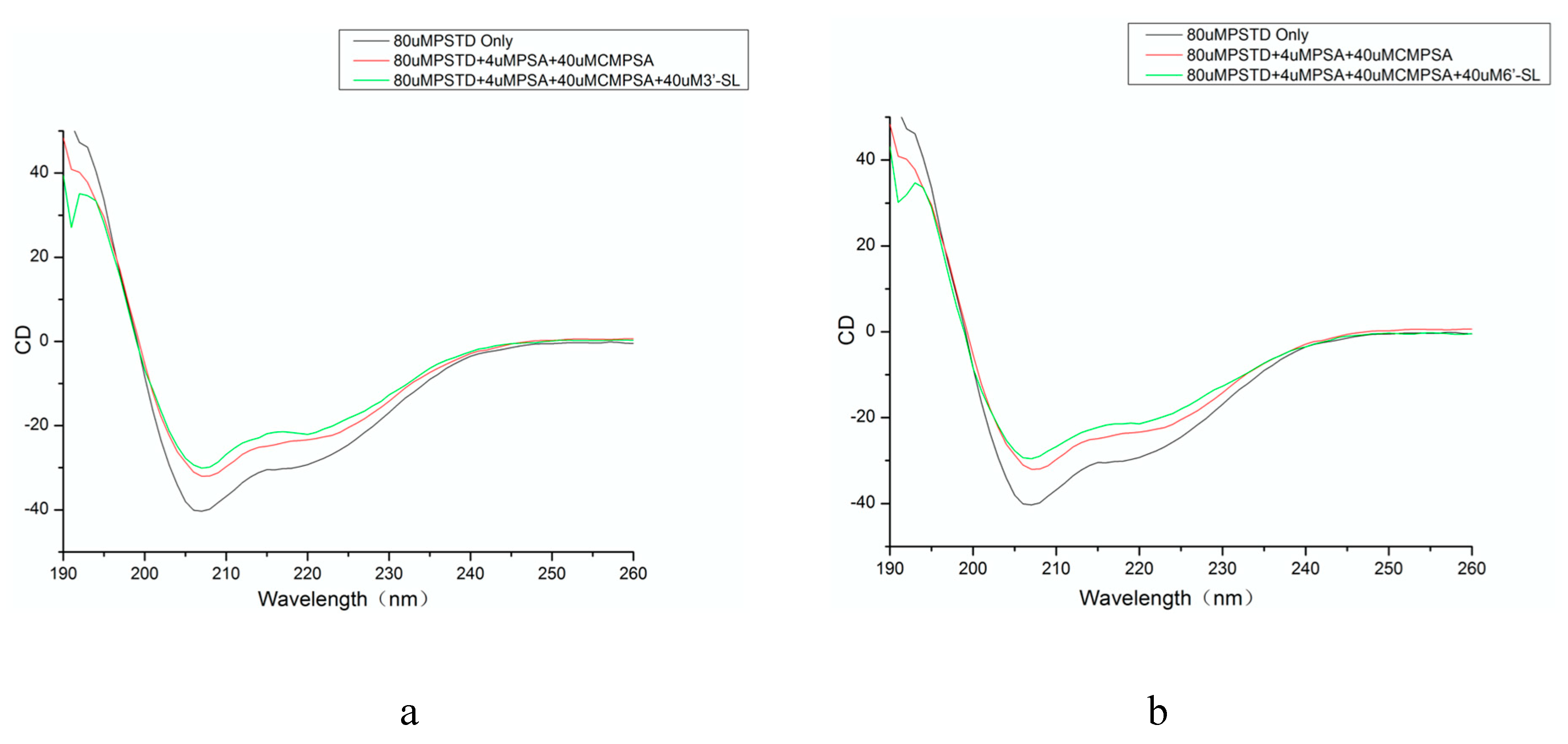

2.1. CD Data

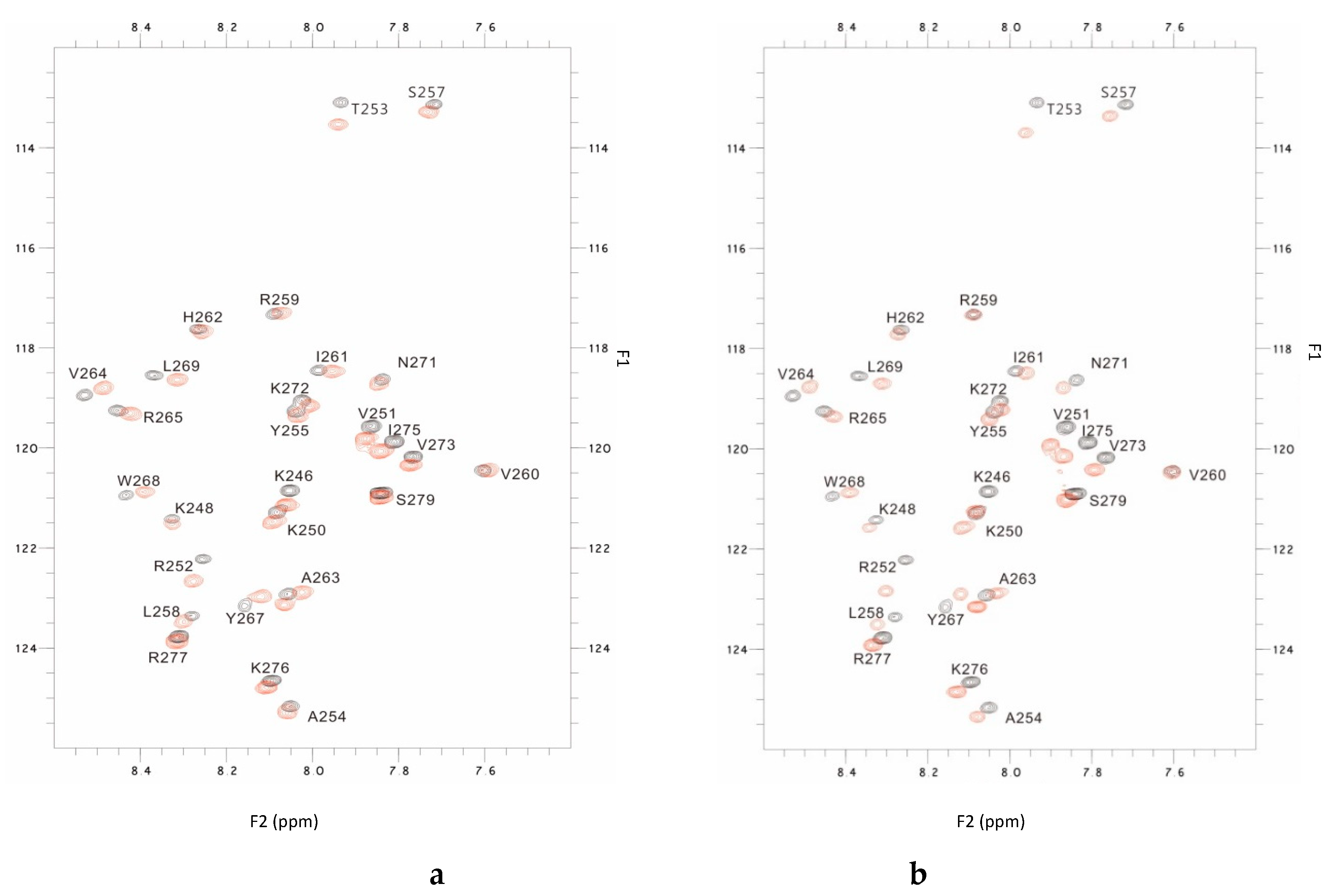

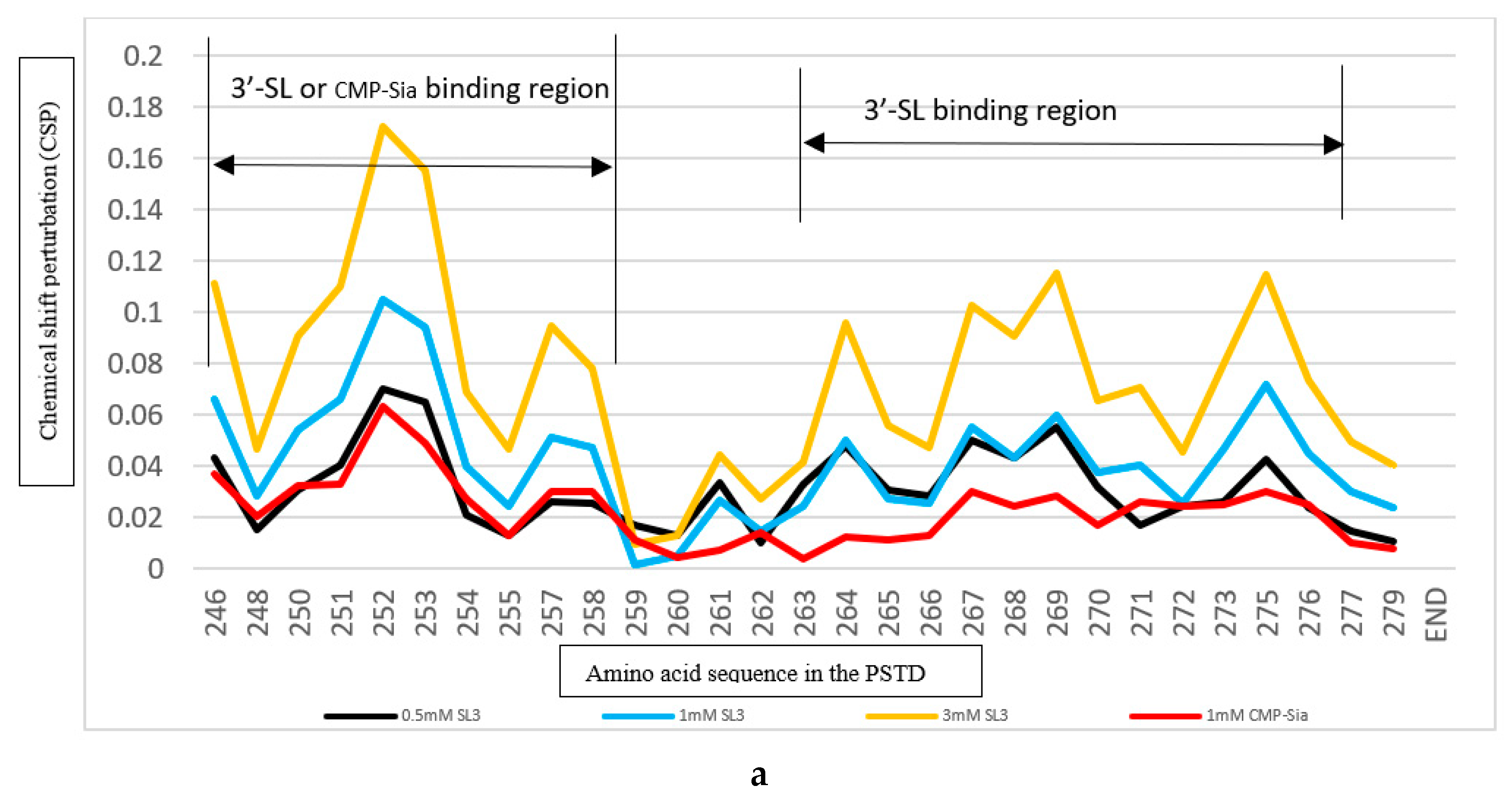

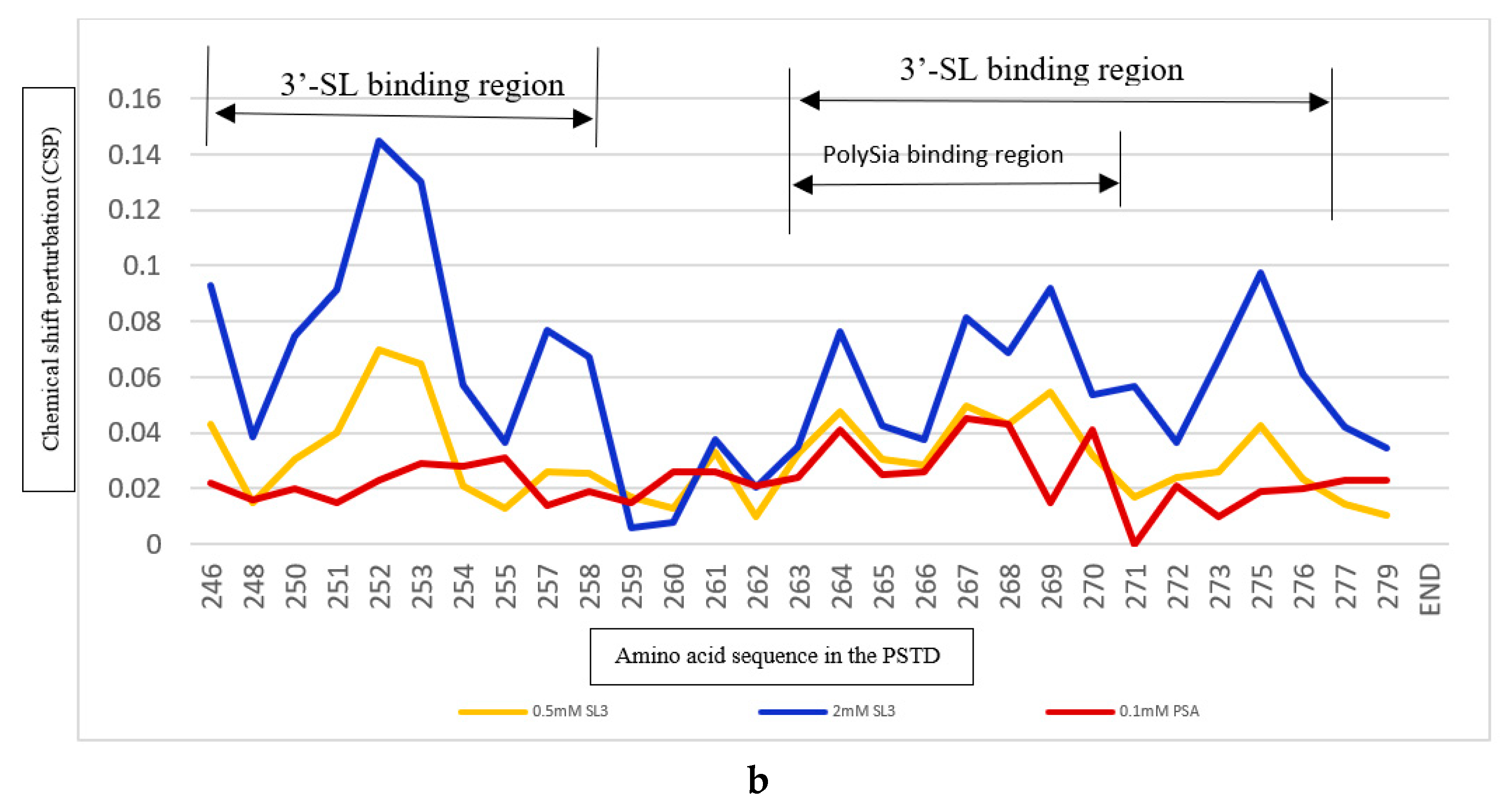

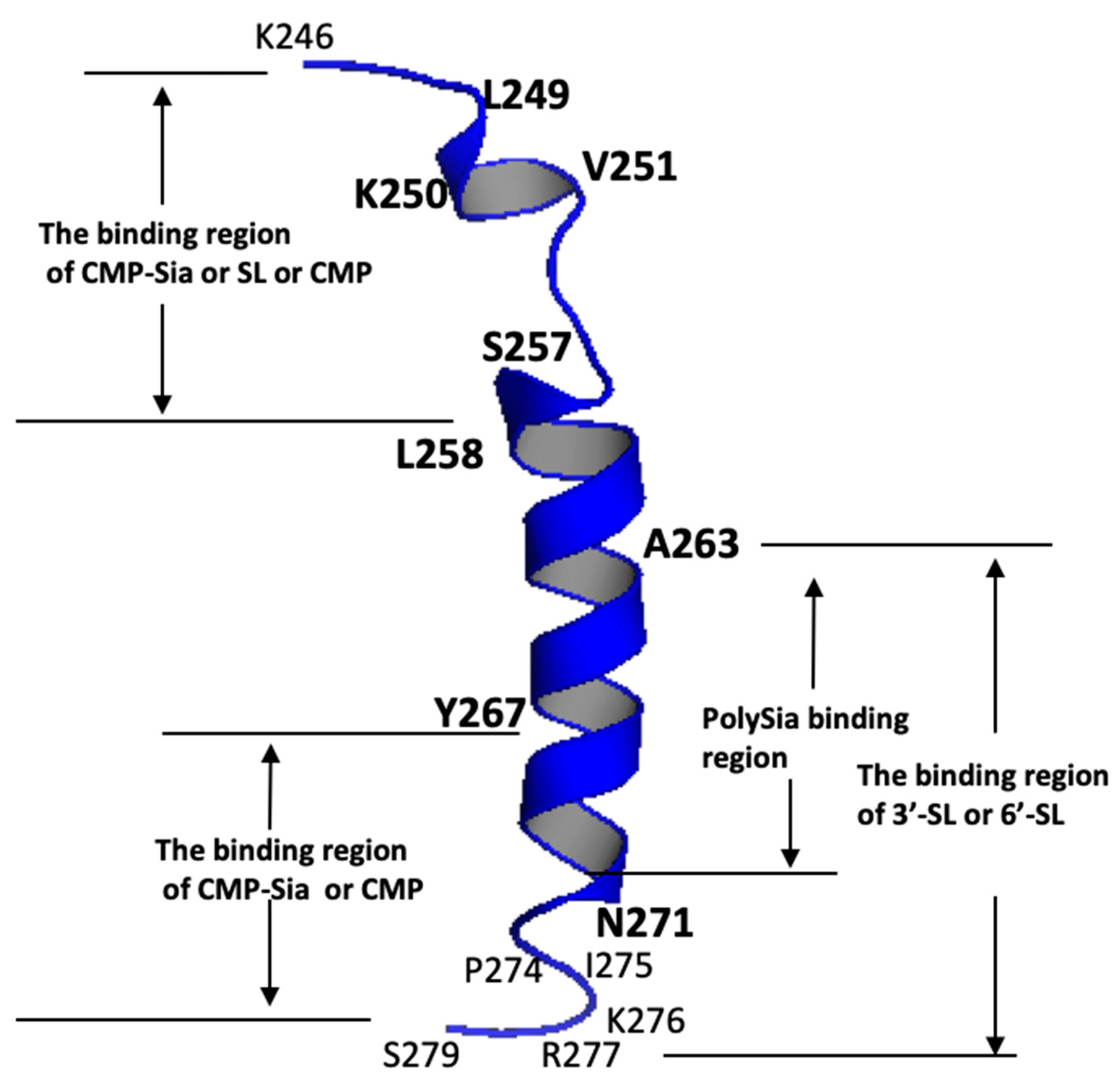

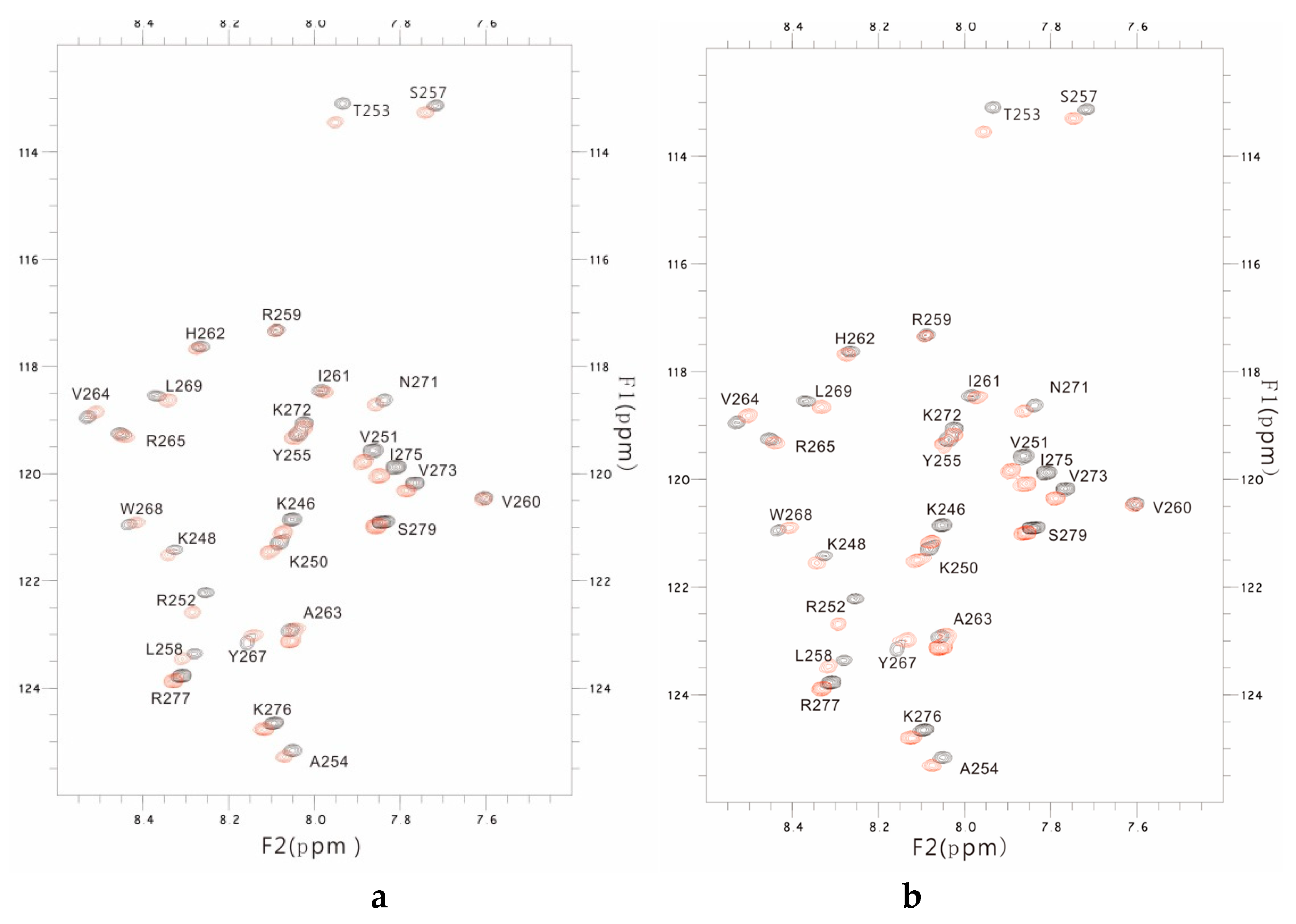

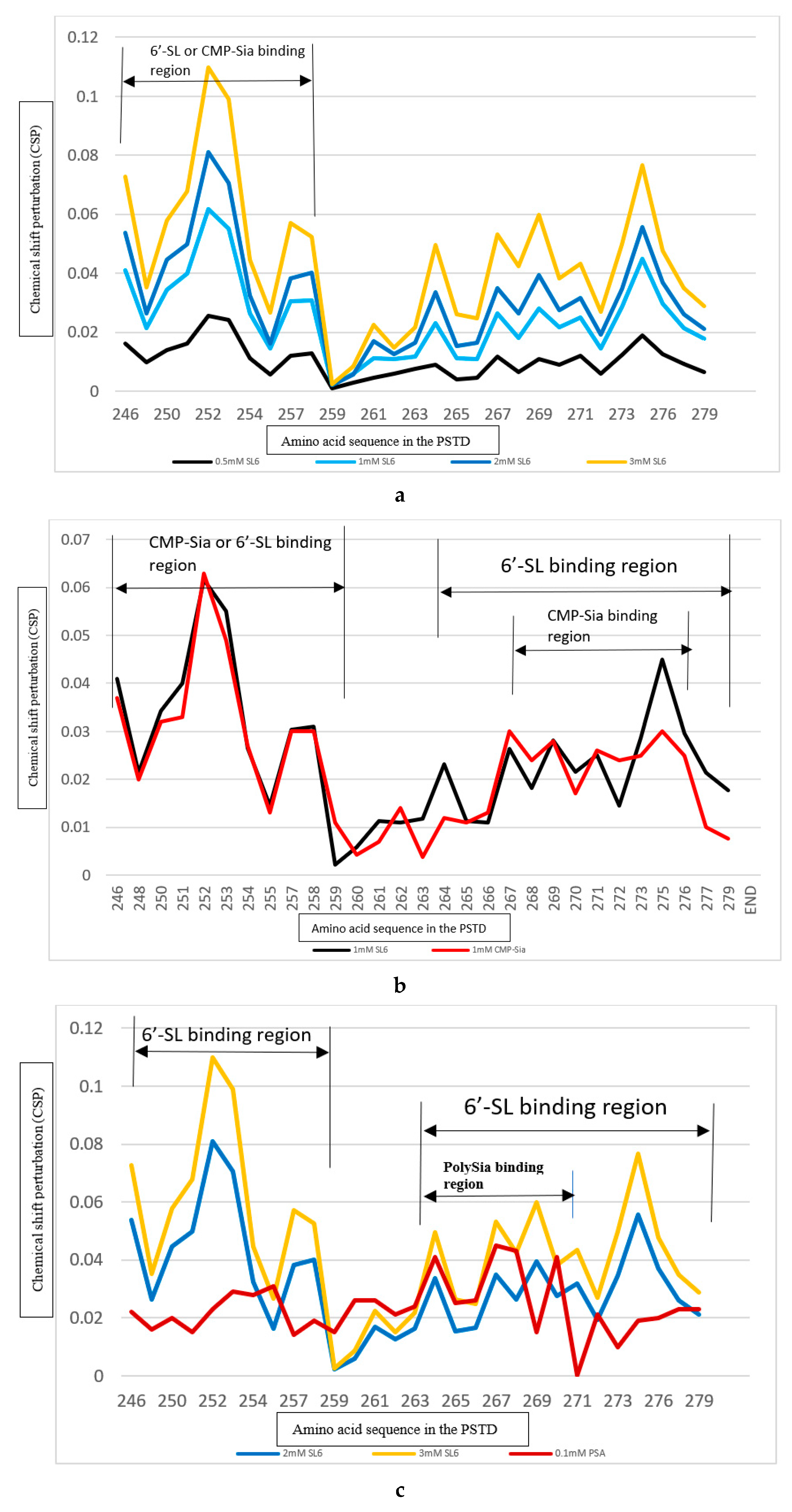

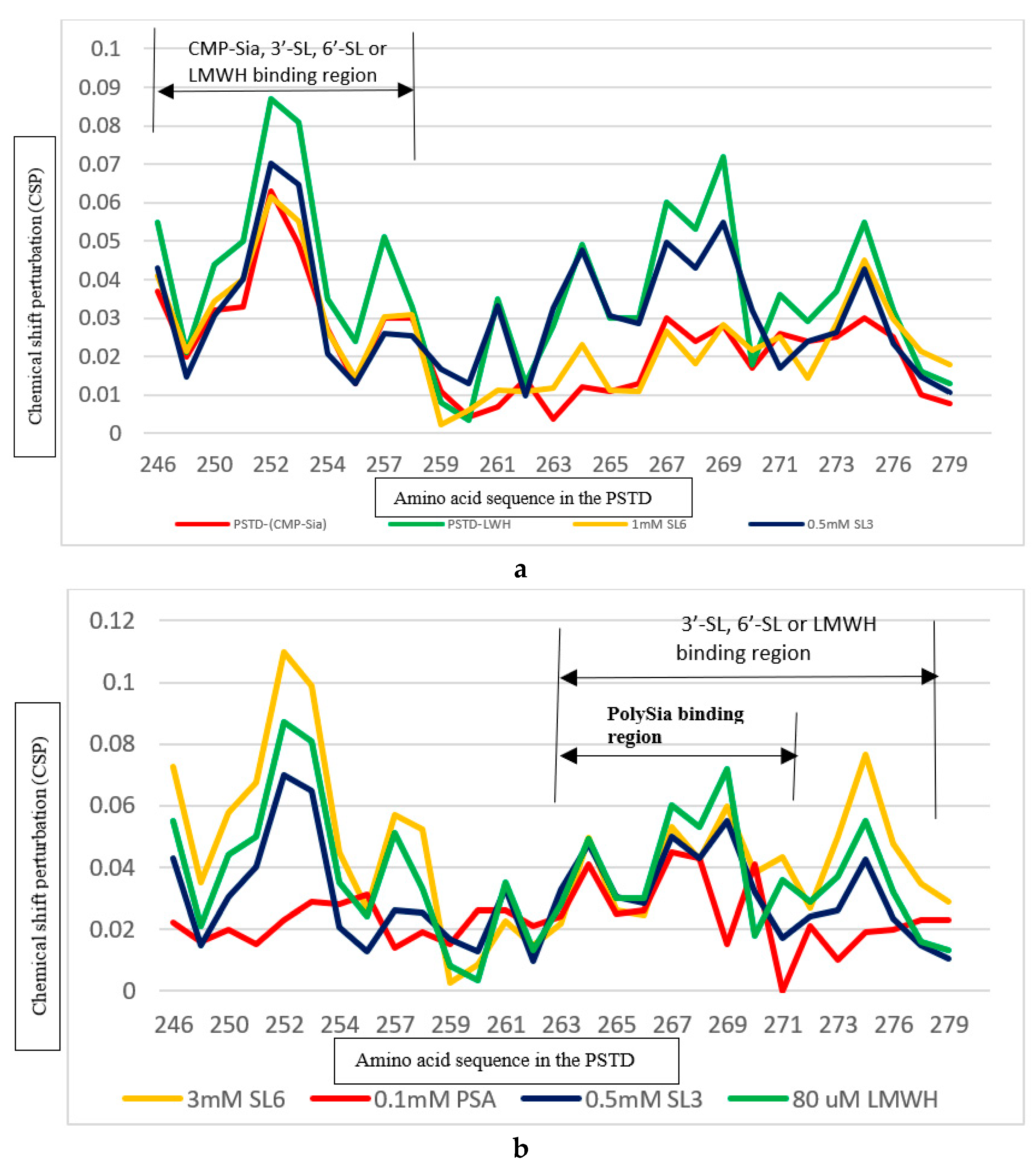

2.2. NMR Results

2.3. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the SLs and Heparin (LMWH) on the Polysialylation

2.3.1. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the SLs and Heparin (LMWH) on the PSTD-CMP-Sia Interaction

2.3.2. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the SLs and Heparin (LMWH) on the PSTD-polySia Interaction

2.4. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the SLs and CMP on the Polysialylation

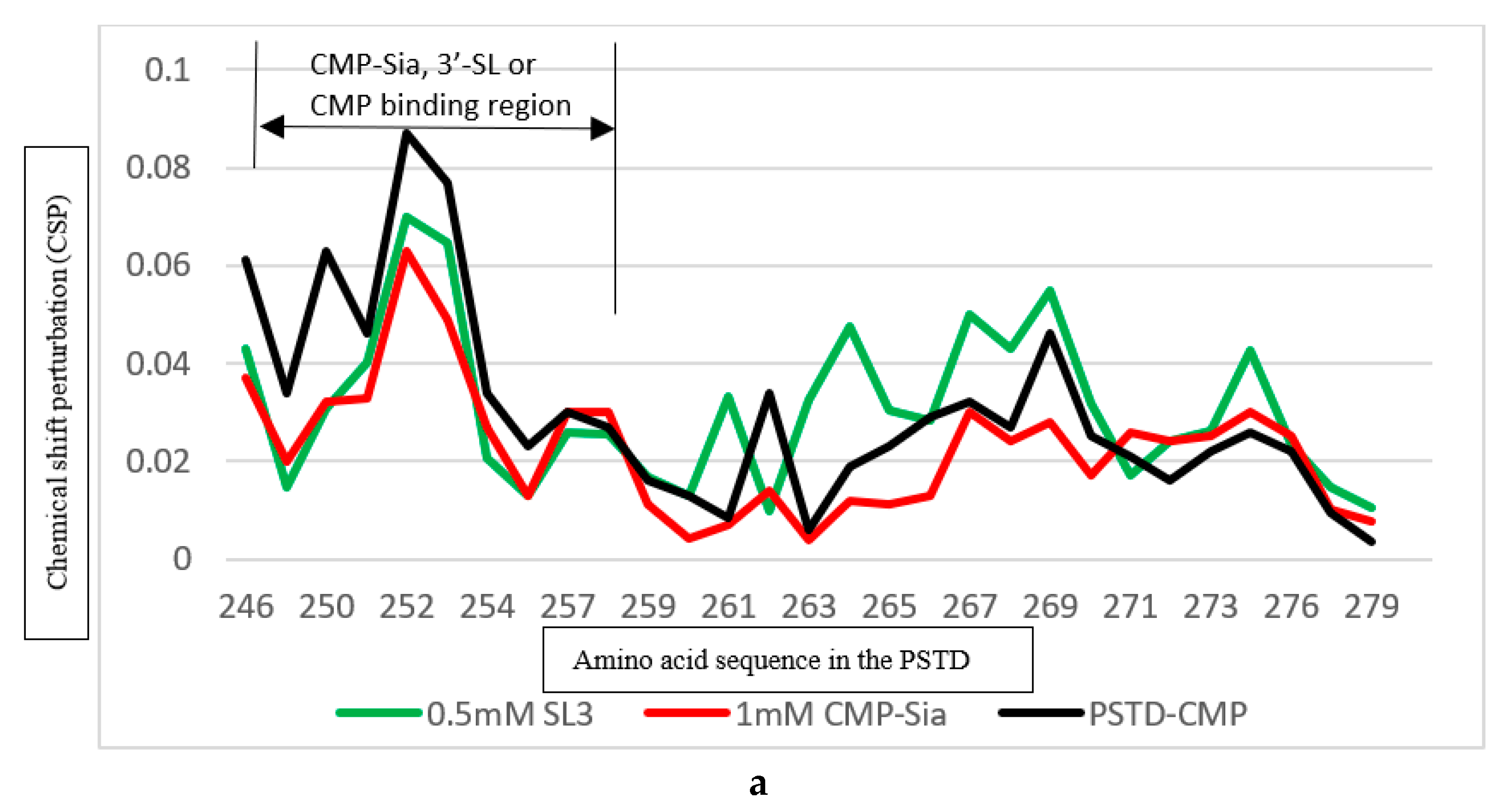

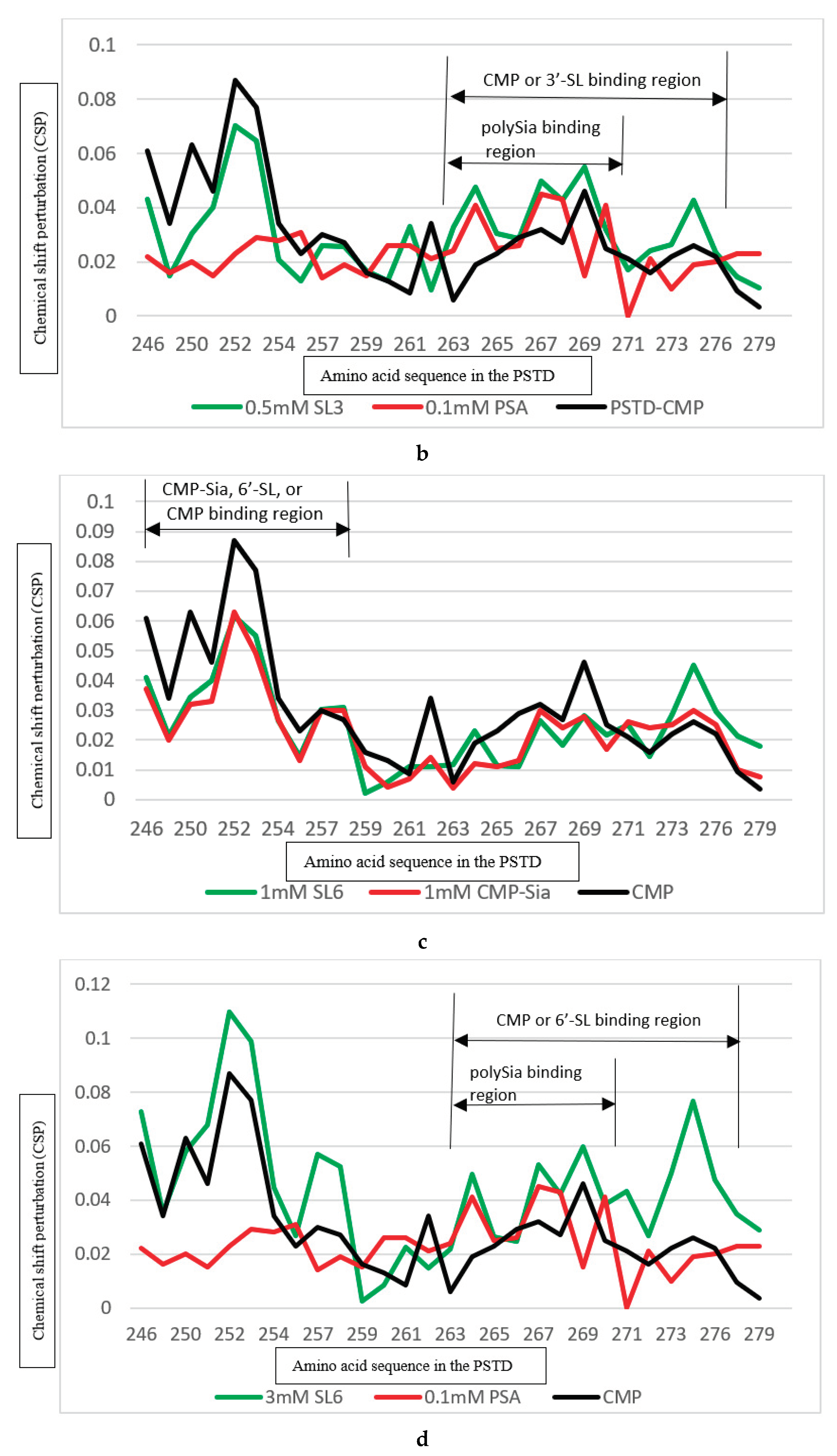

2.4.1. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the 3’-SL and CMP on the PSTD-(CMP-Sia) Interaction

2.4.2. The Comparison of the Inhibition of the 6’-SL and CMP on the Polysialylation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material Sources

4.2. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

4.3. NMR Sample Preparation

4.4. NMR Spectroscopic Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1. polySia | 2. polysialic acid |

| 3. Sia | 4. mono-sialic acid |

| 5. CMP-Sia | 6. cytidine monophosphate-sialic acid |

| 7. NCAMs | 8. neural cell adhesion molecules |

| 9. polySTs | 10. polysialyltransferases (ST8Sia II (STX) & ST8Sia IV (PST) |

| 11. PSTD | 12. polysialyltransferase domain |

| 13. SL | 14. Sialyllactose |

| 15. SMOs | 16. sialylated milk oligosaccharides |

| 17. HMOs | 18. human milk oligosaccharides |

| 19. CSP | 20. chemical shift perturbation |

References

- Craft, K.M.; Townsend, S.D. The Human Milk Glycome as a Defense Against Infectious Diseases: Rationale, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Infect Dis 2018, 4, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandra; J. M ten Bruggencate; Ingeborg MJ Bovee-Oudenhoven; Anouk L Feitsma; Els van Hoffen; Schoterman, M.H. Functional role and mechanisms of sialyllactose and other sialylated milk oligosaccharides. Nutrition Reviews 2014, 72, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Sosa, S.; Martin, M.J.; Garcia-Pardo, L.A.; Hueso, P. Sialyloligosaccharides in human and bovine milk and in infant formulas: variations with the progression of lactation. J Dairy Sci 2003, 86, 52–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ding, J.; Jin, G.; Yu, D.; Yu, L.; Long, Z.; Guo, Z.; Chai, W.; Liang, X. Profiling of Sialylated Oligosaccharides in Mammalian Milk Using Online Solid Phase Extraction-Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography Coupled with Negative-Ion Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem 2018, 90, 3174–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facinelli, B.; Marini, E.; Magi, G.; Zampini, L.; Santoro, L.; Catassi, C.; Monachesi, C.; Gabrielli, O.; Coppa, G.V. Breast milk oligosaccharides: effects of 2'-fucosyllactose and 6'-sialyllactose on the adhesion of Escherichia coli and Salmonella fyris to Caco-2 cells. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019, 32, 2950–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.T.; Chen, C.; Newburg, D.S. Utilization of major fucosylated and sialylated human milk oligosaccharides by isolated human gut microbes. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 1281–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Yoon, S.J.; Itoh, K.; Nakayama, K. Tyrosine kinase activity of epidermal growth factor receptor is regulated by GM3 binding through carbohydrate to carbohydrate interactions. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 6147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntz, S.; Rudloff, S.; Kunz, C. Oligosaccharides from human milk influence growth-related characteristics of intestinally transformed and non-transformed intestinal cells. Br J Nutr 2008, 99, 462–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, P.; Fang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Qiao, Z.; Troy, F.A., 2nd; Wang, B. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying How Sialyllactose Intervention Promotes Intestinal Maturity by Upregulating GDNF Through a CREB-Dependent Pathway in Neonatal Piglets. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 7994–8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.W.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, H.J.; Jang, S.B.; Kim, K.J.; Ha, S.H.; Abekura, F.; Kwak, C.H.; Kim, C.H.; et al. Sialyllactose suppresses angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFR-2 activation, and tumor progression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 58152–58162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassane-Kpembi, I.; Canlet, C.; Tremblay-Franco, M.; Jourdan, F.; Chalzaviel, M.; Pinton, P.; Cossalter, A.M.; Achard, C.; Castex, M.; Combes, S.; et al. (1)H-NMR metabolomics response to a realistic diet contamination with the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol: Effect of probiotics supplementation. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 138, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angata, K.; Suzuki, M.; McAuliffe, J.; Ding, Y.; Hindsgaul, O.; Fukuda, M. Differential biosynthesis of polysialic acid on neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and oligosaccharide acceptors by three distinct alpha 2,8-sialyltransferases, ST8Sia IV (PST), ST8Sia II (STX), and ST8Sia III. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 18594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troy, F.A. , 2nd, Polysialylation: from bacteria to brains. Glycobiology 1992, 2, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A. The Beginnings of Sialic Acid. Biology of the Sialic Acids. Springer: Berlin, Germany.

- Munro, S. Essentials of Glycobiology. Trends in Cell Biology 2000, 10, 552–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B.; Troy, F.A. , 2nd, 3D structural conformation and functional domains of polysialyltransferase ST8Sia IV required for polysialylation of neural cell adhesion molecules. Protein Pept Lett 2015, 22, 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, D.; Zhang, L.; Troy, F.A. Molecular basis for polysialylation: A novel polybasic polysialyltransferase domain (PSTD) of 32 amino acids unique to the α2,8-polysialyltransferases is essential for polysialylation. Glycoconjugate Journal.

- Foley, D.A.; Swartzentruber, K.G.; Colley, K.J. Identification of sequences in the polysialyltransferases ST8Sia II and ST8Sia IV that are required for the protein-specific polysialylation of the neural cell adhesion molecule, NCAM. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 15505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhide, G.P.; Prehna, G.; Ramirez, B.E.; Colley, K.J. The Polybasic Region of the Polysialyltransferase ST8Sia-IV Binds Directly to the Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule, NCAM. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 1504–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.-P.; Liao, S.-M.; Chen, D.; Huang, R.-B. The Cooperative Effect between Polybasic Region (PBR) and Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) within Tumor-Target Polysialyltranseferase ST8Sia II. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 19, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.B.; Cheng, D.; Liao, S.M.; Lu, B.; Wang, Q.Y.; Xie, N.Z.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Zhou, G.P. The Intrinsic Relationship Between Structure and Function of the Sialyltransferase ST8Sia Family Members. Curr Top Med Chem 2017, 17, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.M.; Lu, B.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, Z.L.; Liang, S.J.; Chen, D.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. Molecular Interactions of the Polysialytransferase Domain (PSTD) in ST8Sia IV with CMP-Sialic Acid and Polysialic Acid Required for Polysialylation of the Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule Proteins: An NMR Study. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.M.; Liu, X.H.; Peng, L.X.; Lu, B.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. Molecular Mechanism of Inhibition of Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD) by Heparin. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Liu, X.H.; Liao, S.M.; Lu, Z.L.; Chen, D.; Troy Ii, F.A.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. A Possible Modulation Mechanism of Intramolecular and Intermolecular Interactions for NCAM Polysialylation and Cell Migration. Curr Top Med Chem 2019, 19, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. The Medicinal Chemistry of Structure-based Inhibitor/Drug Design: Current Progress and Future Prospective. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 1097–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.P.; Chou, K.C. Two Latest Hot Researches in Medicinal Chemistry. Curr Top Med Chem 2020, 20, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. The Latest Researches of Enzyme Inhibition and Multi-Target Drug Predictors in Medicinal Chemistry. Med Chem 2019, 15, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. Current Advances of Drug Target Research in Medicinal Chemistry. Curr Top Med Chem 2019, 19, 2269–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.X.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, B.; Liao, S.M.; Zhou, F.; Huang, J.M.; Chen, D.; Troy, F.A. , II; Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B. The Inhibition of Polysialyltranseferase ST8SiaIV Through Heparin Binding to Polysialyltransferase Domain (PSTD). Med Chem 2019, 15, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Liao, S.M.; Liu, X.H.; Liang, S.J.; Huang, J.; Lin, M.; Meng, L.; Wang, Q.Y.; Huang, R.B.; Zhou, G.P. The NMR studies of CMP inhibition of polysialylation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2023, 38, 2248411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Sutherland, M.; Springett, B.R.; Freiberger, F.; Ribeiro Morais, G.; Loadman, P.M.; Errington, R.J.; Smith, P.J.; Fukuda, M.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of polysialyltransferase ST8SiaII modulates tumour cell migration. PLoS One 2013, 8, e73366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.I.; Reglero, A.; Rodriguez-Aparicio, L.B.; Luengo, J.M. In vitro synthesis of colominic acid by membrane-bound sialyltransferase of Escherichia coli K-235. Kinetic properties of this enzyme and inhibition by CMP and other cytidine nucleotides. Eur J Biochem 1989, 178, 741–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B. The Graphical Studies of the Major Molecular Interactions for Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM) Polysialylation by Incorporating Wenxiang Diagram into NMR Spectroscopy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Chen, D.; Liao, S.; Huang, R.B. Recent Progresses in Studying Helix-Helix Interactions in Proteins by Incorporating the Wenxiang Diagram into the NMR Spectroscopy. Curr Top Med Chem 2016, 16, 581–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P. The disposition of the LZCC protein residues in wenxiang diagram provides new insights into the protein-protein interaction mechanism. J Theor Biol 2011, 284, 142–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C. The Significant and Profound Impacts of Chou’s “wenxiang” Diagram. Voice of the Publisher 2020, 06, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Lin, W.-Z.; Xiao, X. Wenxiang: a web-server for drawing wenxiang diagrams. Natural Science 2011, 03, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Zhang, C.-T.; Maggiora, G.M. Disposition of amphiphilic helices in heteropolar environments. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics 1997, 28, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Zhong, W.Z. Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. Curr Top Med Chem 2016, 16, 381–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Huang, R.B. The pH-triggered conversion of the PrP(c) to PrP(sc.). Curr Top Med Chem 2013, 13, 1152–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, N.; Lee, L.Y.; De Castro, C.A.; Steenhout, P.; Thakkar, S.K. Longitudinal change of selected human milk oligosaccharides and association to infants' growth, an observatory, single center, longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, J.; Pisa, E.; Arias Vasquez, A.; Tomasi, F.; Traversa, A.; Chiodi, V.; Martin, F.P.; Sprenger, N.; Lukjancenko, O.; Zollinger, A.; et al. Sialylated human milk oligosaccharides program cognitive development through a non-genomic transmission mode. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2854–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, E.; Hogwood, J.; Mulloy, B. The anticoagulant and antithrombotic mechanisms of heparin. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Efsa Panel on Nutrition, N.F.; Food, A.; Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Safety of 6'-sialyllactose (6'-SL) sodium salt produced by derivative strains of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J 2022, 20, e07645. [Google Scholar]

- Efsa Panel on Nutrition, N.F.; Food, A.; Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Safety of 3'-sialyllactose (3'-SL) sodium salt produced by derivative strains of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) as a Novel Food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J 2022, 20, e07331. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer, R.; Kamerling, J.P. Exploration of the Sialic Acid World. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 2018, 75, 1–213. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Loers, G.; Schachner, M.; Boelens, R.; Wienk, H.; Siebert, S.; Eckert, T.; Kraan, S.; Rojas-Macias, M.A.; Lutteke, T.; et al. Molecular Basis of the Receptor Interactions of Polysialic Acid (polySia), polySia Mimetics, and Sulfated Polysaccharides. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Piai, A.; Chen, W.; Xia, K.; Chou, J.J. Structure determination protocol for transmembrane domain oligomers. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 2483–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, J.R.; Zhou, G.P.; Zweckstetter, M.; Rigby, A.C.; Chou, J.J. Rapid and accurate structure determination of coiled-coil domains using NMR dipolar couplings: application to cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ialpha. Protein Sci 2005, 14, 2421–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Zhou, G.P.; Kupferman, J.; Surks, H.K.; Christensen, E.N.; Chou, J.J.; Mendelsohn, M.E.; Rigby, A.C. Probing the interaction between the coiled coil leucine zipper of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ialpha and the C terminus of the myosin binding subunit of the myosin light chain phosphatase. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 32860–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, M.J.; Shih, W.M.; Harrison, S.C.; Chou, J.J. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature 2011, 476, 109–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OuYang, B.; Xie, S.; Berardi, M.J.; Zhao, X.; Dev, J.; Yu, W.; Sun, B.; Chou, J.J. Unusual architecture of the p7 channel from hepatitis C virus. Nature 2013, 498, 521–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxenoid, K.; Dong, Y.; Cao, C.; Cui, T.; Sancak, Y.; Markhard, A.L.; Grabarek, Z.; Kong, L.; Liu, Z.; Ouyang, B.; et al. Architecture of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 2016, 533, 269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; OuYang, B.; Chou, J.J. Critical Effect of the Detergent:Protein Ratio on the Formation of the Hepatitis C Virus p7 Channel. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3834–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Fu, T.M.; Cruz, A.C.; Sengupta, P.; Thomas, S.K.; Wang, S.; Siegel, R.M.; Wu, H.; Chou, J.J. Structural Basis and Functional Role of Intramembrane Trimerization of the Fas/CD95 Death Receptor. Mol Cell 2016, 61, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.R.; Poluri, K.M.; Sepuru, K.M.; Rajarathnam, K. Characterizing protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions using solution NMR spectroscopy. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1229, 325–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorndahl, T.C.; Zhou, G.P.; Liu, X.; Perez-Pineiro, R.; Semenchenko, V.; Saleem, F.; Acharya, S.; Bujold, A.; Sobsey, C.A.; Wishart, D.S. Detailed biophysical characterization of the acid-induced PrP(c) to PrP(beta) conversion process. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaynberg, J.; Qin, J. Weak protein-protein interactions as probed by NMR spectroscopy. Trends Biotechnol 2006, 24, 22–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheer, M.; Bork, K.; Simon, F.; Nagasundaram, M.; Horstkorte, R.; Gnanapragassam, V.S. Glycation Leads to Increased Polysialylation and Promotes the Metastatic Potential of Neuroblastoma Cells. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenoweth, M.B.; Ellman, G.L. Tissue metabolism (pharmacological aspects). Annu Rev Physiol 1957, 19, 121–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| The helical content of the PSTD in the absence of any ligands (%) | The helical content of the PSTD in the presence of CMP-Sia and polySia (%) | The helical content of the PSTD in the presence of CMP-Sia, polySia and 3’-SL (%) | The helical content of the PSTD in the presence of CMP-Sia, polySia and 6’-SL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26.5 | 18.4 | 17.7 | 14.5 |

| Sialylactose (SL) interacted with the PSTD | SL’s concentration when CSPs of PSTD-SL binding are close to that of PSTD-(CMP-Sia) binding in same amino acid range of the PSTD (mM) | SL’s concentration when CSPs of PSTD-SL binding are close to that of PSTD-polySia binding in same amino acid range of the PSTD (mM) | The maximum concentration of the SL in human milk during 1st month of lactation (mM)[9] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3’-SL | 0.5 | 0.5 | Ca. 0.5 |

| 6’-SL | 1.0 | Ca. 3.0 | Ca. 1.0 |

| Ligands binding to the PSTD | The main binding region of the ligands in the PSTD | The maximum CSPs of each binding region | Is CMP-Sia binding inhibited by the following ligand? | Is polySia binding inhibited by the following ligand? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMP-Sia | K246-S257 V267-276 |

0.070 0.026 |

N/A N/A |

No No |

| polySia | A263-N271 | 0.049 | No | N/A |

| Heparin LMWH | K246-S257 A263-R277 |

0.087 0.072 |

Yes N/A |

N/A Yes |

| CMP | K246-S257 A263-R277 |

0.087 0.046 |

Yes N/A |

N/A No |

| 3’-SL (0.5 mM) |

K246-S257 A263-R277 |

0.070 0.043 |

Yes, when 3’-SL concentration more than 0.5 mM N/A |

N/A Yes, when 3’-SL concentration more than 0.5 mM |

| 6’-SL (1mM) |

K246-S257 A263-R277 |

0.070 0.026 |

Yes, when 6’-SL concentration more than 1 mM N/A |

N/A Yes, when 6’-SL concentration is about 3 mM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).