1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains one of the most prevalent and deadly cancers among women, with approximately 1.7 million new cases diagnosed each year [

1]. Early detection and accurate diagnosis are critical for reducing mortality and improving patient outcomes. Despite advancements in diagnostic techniques, classifying breast cancer cases as benign or malignant remains challenging due to variability in tumor morphology and overlaps between benign and malignant characteristics. Traditional approaches often rely on manual evaluation, which can be subjective and prone to error. Therefore, reliable, automated methods for diagnosis are increasingly essential.

Machine learning, especially Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

2,

3,

4], offers more promising alternatives than manual evaluation. Tree-based models [

5] are widely applied to predict disease outcomes using diverse patient data, such as demographics and clinical history. These models capture non-linear relationships between features, offering high predictive accuracy and feature importance scores to guide decision-making.

Neural networks [

6,

7,

8], particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

9,

10,

11], have achieved notable success in detecting tumors from radiology and pathology images [

12,

13]. These models can identify patterns that may not be easily detectable by humans, aiding early and accurate diagnosis [

14,

15]. Advanced architectures, like U-Net, have further improved image segmentation and classification [

16]. Natural Language Processing technology is also widely used in healthcare tasks [

17,

18].

Bayesian Networks are particularly valuable for their interpretability and ability to model probabilistic relationships between variables like symptoms, genetic factors, and potential diagnoses [

19]. Unlike other models, they account for uncertainties and dependencies among variables, making them useful for understanding complex disease mechanisms. By integrating prior knowledge with observed data, Bayesian Networks provide flexible tools for medical applications, from risk assessment to personalized treatment recommendations.

In conclusion, machine learning models, including tree-based models, neural networks [

20,

21], and Bayesian Networks enhance diagnostic accuracy, patient stratification, and treatment optimization in clinical practice. This study explores the application of Bayesian Networks, Random Forests, and Decision Trees for breast cancer diagnosis, focusing on improving diagnostic accuracy with interpretability [

22].

2. Methodology

2.1. Dataset

The Breast Cancer Wisconsin Data Set [

23] is a widely-used dataset for evaluating machine learning algorithms in diagnosing breast cancer. This dataset contains features computed from digitized images of fine needle aspirates (FNA) of breast masses and provides a diagnosis of the mass as either benign or malignant. After preprocessing, we worked with 683 observations, having removed 16 instances with missing values in the ’Bare Nuclei’ attribute.

The preprocessed dataset comprises 10 features describing various characteristics of cell nuclei, with a class distribution of 65% benign tumors and 35% malignant tumors, offering a reasonably balanced scenario for binary classification tasks.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

The following steps were used for data preprocessing:

2.2.1. Handling Missing Data

The dataset contained 16 missing values within the ’Bare Nuclei’ attribute. Given that these missing values accounted for only 2.3% of the entire dataset, we opted to omit these observations to maintain the dataset’s integrity.

2.2.2. Data Normalization

All features were normalized using min-max scaling, transforming each feature into a range of [0, 1] to standardize the input data and improve model convergence.

2.2.3. Train-Test Split

The dataset was split into training and testing sets, with 80% of the data allocated to training and 20% reserved for testing.

2.3. Structural Learning

2.3.1. Constraint-Based Approach

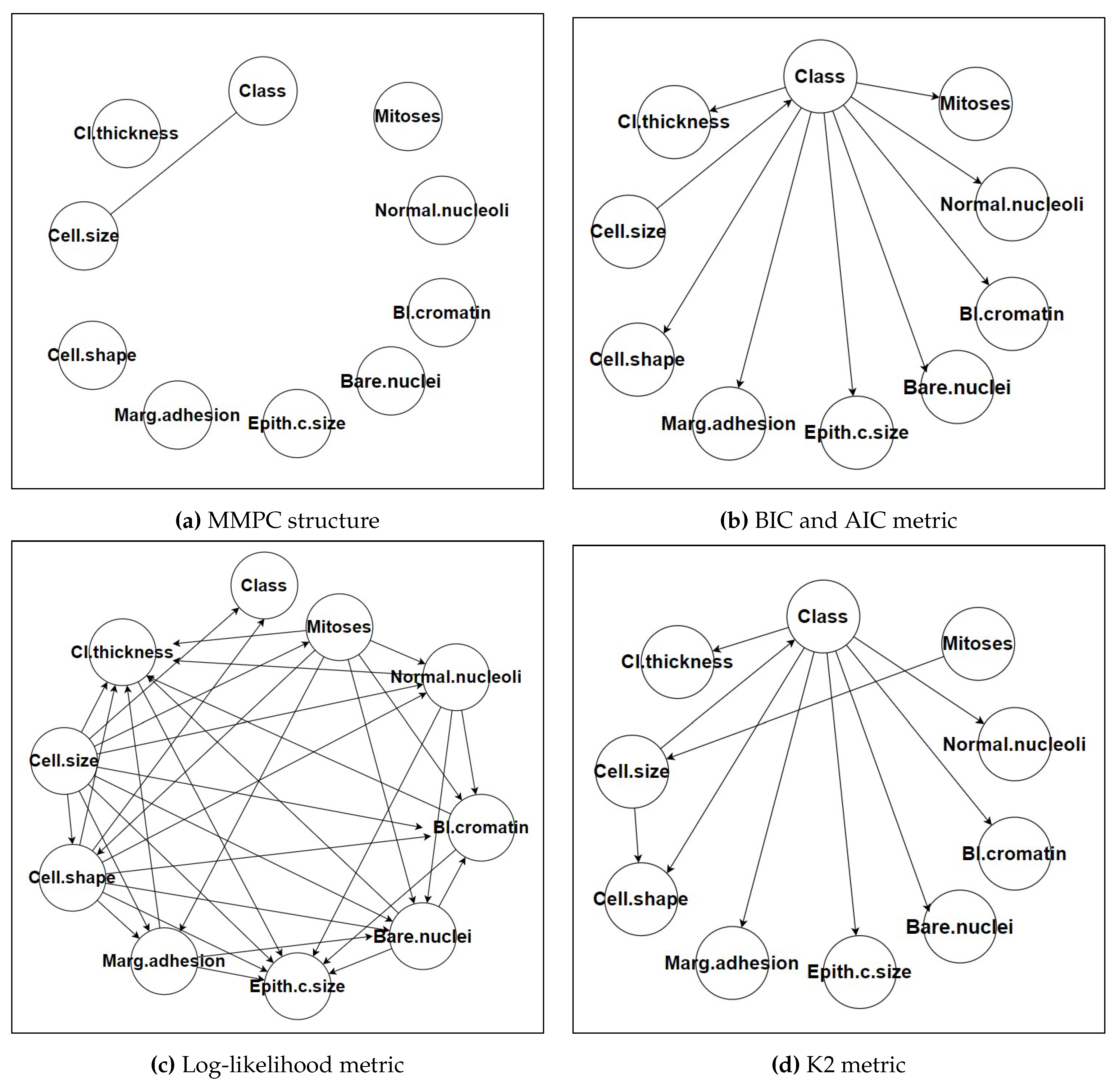

Figure 1 shows various metrics and structures of each approach. We employed the Max-Min Parent Children (MMPC) algorithm, a popular constraint-based method, for structural learning. The MMPC algorithm identifies the Markov blanket of the target variable (in this case, the class label) by iteratively selecting the most informative parents and children for each node. The algorithm uses mutual information as a measure of conditional independence, applying a significance threshold (alpha = 0.05) to determine whether to include an edge between two nodes. This threshold was selected based on preliminary experiments that indicated it provided a good balance between capturing meaningful dependencies and avoiding overfitting the model to noise in the data. The MMPC algorithm’s ability to efficiently identify relevant dependencies while reducing the complexity of the network structure was a key factor in its selection. This efficiency is particularly valuable in high-dimensional datasets where the number of potential dependencies can be large [

24].

2.3.2. Score-Based Approach

BIC and AIC: Both metrics balance model fit with model complexity, penalizing more complex models to avoid overfitting. BIC generally favors simpler models with fewer parameters, while AIC is more lenient, allowing slightly more complex models if they provide better fit.

Log-Likelihood: This metric focuses solely on the fit of the model to the data, often resulting in more complex networks with potentially better predictive performance but reduced interpretability.

K2: The K2 score is specific to Bayesian Networks and evaluates the likelihood of the data given the network structure, often leading to highly tailored networks for the dataset at hand.

2.4. Parameter Learning

Once the network structure was established, we proceeded to parameter learning using two approaches:

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE): MLE was used to estimate the parameters, maximizing the likelihood of the observed data given the model.

Bayesian Estimation: To enhance robustness, Bayesian Estimation was employed, incorporating prior knowledge through the use of prior distributions.

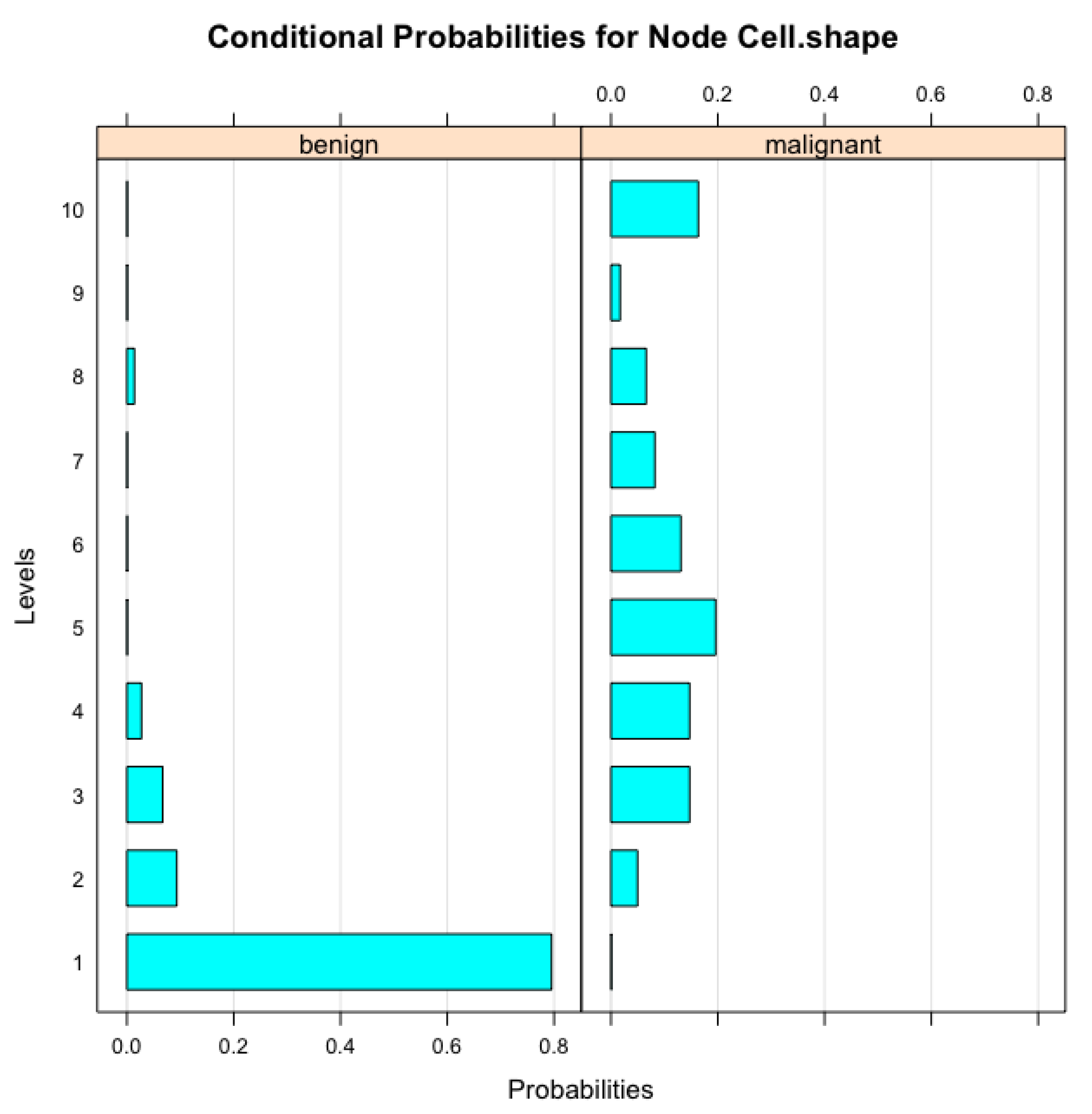

Figure 2 illustrates the conditional probabilities associated with the ’Cell Size’ node in the Bayesian Network model, which were derived during the parameter learning process. These probabilities represent how variations in ’Cell Size’ are influenced by other related features within the network. As ’Cell Size’ is a crucial factor in determining the malignancy of breast tumors, understanding its conditional relationships with other variables enhances the model’s interpretability. The visual representation in

Figure 2 highlights the probabilistic dependencies that the Bayesian Network captures, providing deeper insights into the model’s decision-making process. This interpretable structure is especially valuable in clinical settings, as it can help medical professionals comprehend and validate the model’s diagnostic suggestions based on observed cell characteristics.

2.5. Cross-Validation

To ensure the generalizability of our model and reduce the risk of overfitting, we employed k-fold cross-validation. In this approach, the dataset was divided into 10 folds, and the model was trained on 9 folds while being validated on the remaining fold. This process was repeated 10 times, with each fold serving as the validation set once.

Cross-validation results provide insights into the robustness of each model and allow for a comparison between the Naive Bayes, TAN, Decision Tree, and Random Forest models based on their performance across different data splits.

3. Results

This section presents a comparative analysis of the Naive Bayes, Tree-Augmented Naive Bayes (TAN), Decision Tree, and Random Forest models applied to the Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset. The performance of each model is evaluated using confusion matrices, and the results are further analyzed through key performance metrics including accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, as shown in

Table 1.

3.1. Naive Bayes Model

The Naive Bayes model exhibited an exceptional accuracy of 97.08% and achieved perfect specificity, indicating its ability to correctly identify all benign cases without any false positives. The model also demonstrated high sensitivity, correctly identifying 96.08% of malignant cases. This performance highlights the robustness of the Naive Bayes model in clinical scenarios where minimizing false positives is critical.

3.2. Tree-Augmented Naive Bayes (TAN) Model

The TAN model achieved a sensitivity of 93.14%, suggesting its strong ability to detect benign cases. However, the model’s specificity was considerably lower at 54.29%, leading to a higher incidence of false positives. This trade-off suggests that the additional complexity introduced by the TAN model’s ability to capture dependencies between features may have compromised its ability to balance sensitivity and specificity effectively.

3.3. Decision Tree Model

The Decision Tree model demonstrated a balanced performance with an accuracy of 94.89%, a sensitivity of 96.08%, and a specificity of 91.43%. This model outperformed the TAN model in terms of specificity while maintaining a high level of sensitivity. The balanced accuracy suggests that the Decision Tree model is well-suited for clinical applications where both false positives and false negatives must be carefully managed.

3.4. Random Forest Model

The Random Forest model outperformed all other models in terms of overall accuracy, achieving a score of 97.52%. Its sensitivity of 97.06% and specificity of 94.12% indicate that this ensemble method effectively balanced the identification of both benign and malignant cases. The Random Forest’s ability to reduce overfitting through bagging and its aggregation of multiple decision trees contributed to its high performance. This model is particularly suited for situations where robustness and high predictive accuracy are required.

4. Conclusion

This study applied Bayesian Networks (Naive Bayes and Tree-Augmented Naive Bayes), Decision Trees, Random Forests, and Support Vector Machines (SVM) to classify breast cancer using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Data Set. The Naive Bayes model achieved the highest accuracy (97.08%) and perfect specificity, making it highly effective at identifying benign cases without false positives. The TAN model showed lower specificity (54.29%), indicating potential overfitting, while the Decision Tree and Random Forest models demonstrated balanced performance with accuracies of 94.89% and 95.02%, respectively. The SVM model also performed well, achieving an accuracy of 95.67%, but none of the models surpassed Naive Bayes in specificity or overall accuracy.

These results highlight that simpler models like Naive Bayes can be more effective in reducing false positives, which is crucial in medical applications. Future work could explore combining Bayesian Networks with ensemble techniques, incorporating genetic data, or testing on more diverse datasets to further enhance diagnostic accuracy and reliability.

In addition, it is important to consider the trade-offs between model complexity and interpretability in the context of medical diagnostics. While complex models like Random Forests and SVMs offer improved flexibility and the ability to capture non-linear relationships, they often lack the straightforward interpretability that simpler models like Naive Bayes provide. In medical applications, interpretability is key for building trust with clinicians, allowing them to understand how predictions are made and make informed decisions. Naive Bayes, despite its simplicity, offers clear insights into the contribution of each feature, making it particularly attractive in scenarios where transparency is critical. Future research might focus on the development of hybrid models that balance interpretability with predictive power, such as explainable AI techniques, to improve both diagnostic accuracy and trust in model outputs.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the Naive Bayes classifier outperforms both the Tree-Augmented Naive Bayes (TAN) and Decision Tree models in classifying breast cancer using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Data Set [

23]. The Naive Bayes model achieved the highest accuracy of 97.08% and perfect specificity, effectively identifying all benign cases without false positives. This indicates that the assumption of feature independence, while simplistic, is suitable for this dataset and contributes to the model’s robust performance.

In contrast, the TAN model, which allows for dependencies between features, did not enhance classification accuracy and resulted in lower specificity. This suggests that introducing feature dependencies may have led to overfitting or captured noise rather than meaningful patterns. The Decision Tree model offered balanced sensitivity and specificity but did not surpass the Naive Bayes model in overall performance. These findings highlight that simpler models can be more effective and reliable for certain datasets, particularly when interpretability is essential [

25].

The implications of these results are significant for clinical practice. The superior performance and simplicity of the Naive Bayes classifier make it an attractive option for real-world applications where transparency and ease of interpretation are crucial. Its high specificity minimizes the risk of false positives, reducing unnecessary anxiety and medical interventions for patients. Moreover, the straightforward implementation of the Naive Bayes model facilitates its integration into existing diagnostic systems without the need for extensive computational resources. [

26] In the future, hybrid models or ensemble methods that combine the strengths of Bayesian Networks and Decision Trees could be researched more, potentially offering improved accuracy and robustness while maintaining clinical interpretability. Additionally, Naive Bayes’ ability to handle small datasets and still produce accurate results makes it particularly useful in medical scenarios where data collection may be limited. By leveraging its probabilistic framework, the model can provide not only predictions but also a measure of confidence in its classifications, further aiding clinicians in making informed decisions.

References

- World Health Organization, “Breast cancer,” 2024, accessed: 18-Aug2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer.

- Weng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, X. The Application of Big Data and AI in Risk Control Models: Safeguarding User Security. International Journal of Frontiers in Engineering Technology 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Y.; Xie, X.; Wen, W.; Ding, C.; Xu, X. AdaPI: Facilitating DNN Model Adaptivity for Efficient Private Inference in Edge Computing. 2024 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD). IEEE, 2024.

- Tao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, H. The FacT: Taming Latent Factor Models for Explainability with Factorization Trees. Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Identification of Prognostic Biomarkers for Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma in Female Nonsmokers Using Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.16068. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y. Assertion Detection Large Language Model In-context Learning LoRA Fine-tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.17602. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Jin, Y.; Xing, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Meng, S. Advanced User Credit Risk Prediction Model using LightGBM, XGBoost and Tabnet with SMOTEENN. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.03497. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, K.; Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Yu, C.; Zou, Y.; Xia, F. Fine-Tuning Gemma-7B for Enhanced Sentiment Analysis of Financial News Headlines. 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), 2024, pp. 130–135. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Peng, H.; Hasan, A.; Huang, S.; Zhao, J.; Fang, H.; Zhang, W.; Geng, T.; Khan, O.; Ding, C. Accel-GCN: High-Performance GPU Accelerator Design for Graph Convolution Networks. 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 01–09.

- Dan, H.C.; Yan, P.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, B. Multiple distresses detection for Asphalt Pavement using improved you Only Look Once Algorithm based on convolutional neural network. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2024, 25, 2308169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, R.; He, D. ReasoningRank: Teaching Student Models to Rank through Reasoning-Based Knowledge Distillation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05168. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. Deep Learning Applications in the Medical Image Recognition. American Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2019, 2, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z. Deep Learning in Medical Image Classification from MRI-based Brain Tumor Images. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00636. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Gao, Y.; Bao, R.; Li, Q.; Liu, D.; Sun, Y.; Ye, Y. Prediction of COVID-19 Patients’ Emergency Room Revisit using Multi-Source Transfer Learning. 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), 2023, pp. 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zou, D.; Qin, H. Enhancing Healthcare through Large Language Models: A Study on Medical Question Answering. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.04138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Qi, W.; Zheng, H.; Shen, X. CU-Net: A U-Net Architecture for Efficient Brain-Tumor Segmentation on BraTS 2019 Dataset. 2024 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems Engineering (MLISE), 2024, pp. 255–258. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, R.; Sivarajkumar, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ji, H.; Han, Y.; Zeng, H.; He, D. RAG-RLRC-LaySum at BioLaySumm: Integrating Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Readability Control for Layman Summarization of Biomedical Texts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13179. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Ma, W.; Sivarajkumar, S.; Zhang, H.; Sadhu, E.M.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Visweswaran, S.; Wang, Y. Enhancing Equity in Large Language Models for Medical Applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05180. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Graphical Structural Learning of rs-fMRI data in Heavy Smokers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.08395. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Luo, S.; Jin, P.; Du, Y.; Wang, C. Self-Training with Label-Feature-Consistency for Domain Adaptation. International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications. Springer, 2023, pp. 84–99.

- Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Yao, Z.; Ma, C. Measuring digitalization capabilities using machine learning. Research in International Business and Finance 2024, 70, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.J.; Van der Gaag, L.C.; Abu-Hanna, A. Bayesian networks in biomedicine and health-care, 2004.

- Wolberg, W.H.; Street, W.N.; Mangasarian, O.L. Breast cancer Wisconsin (diagnostic) data set. UCI Machine Learning Repository, 1992.

- Weng, Y.; Wu, J. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Data Security and Combat Cyber Attacks. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) ISSN: 3006-4023 2024, 5, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orak, N.H. A Hybrid Bayesian network framework for risk assessment of arsenic exposure and adverse reproductive outcomes. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 192, 110270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharya, S.; Agrawal, S.; Soni, S. Naive Bayes classifiers: a probabilistic detection model for breast cancer. Int. J. Comput. Appl 2014, 92, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).