Submitted:

28 March 2023

Posted:

28 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Breast cancer prediction model | ML model | |

|---|---|---|

| Rationales | Use of mathematic formula to predict the cancer | Prediction of cancer via the ML algorithm |

| Methods | Use of data to build formula, connecting factors (e.g., age, height, BMI) and cancer; | Prediction via the “black box” without considering the connections |

| Accuracy of prediction | Assumptions and connections | Quality and quantity of data |

| Advantages | Matured methods with clear process | Convenient and fact prediction |

| Limitations | Incorrect assumption and researchers’ bias | “Black swan” effect |

| Reference | [6,7] | [8,9,10,11,12,13] |

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data collection and clear

2.2. ML models

3. Results

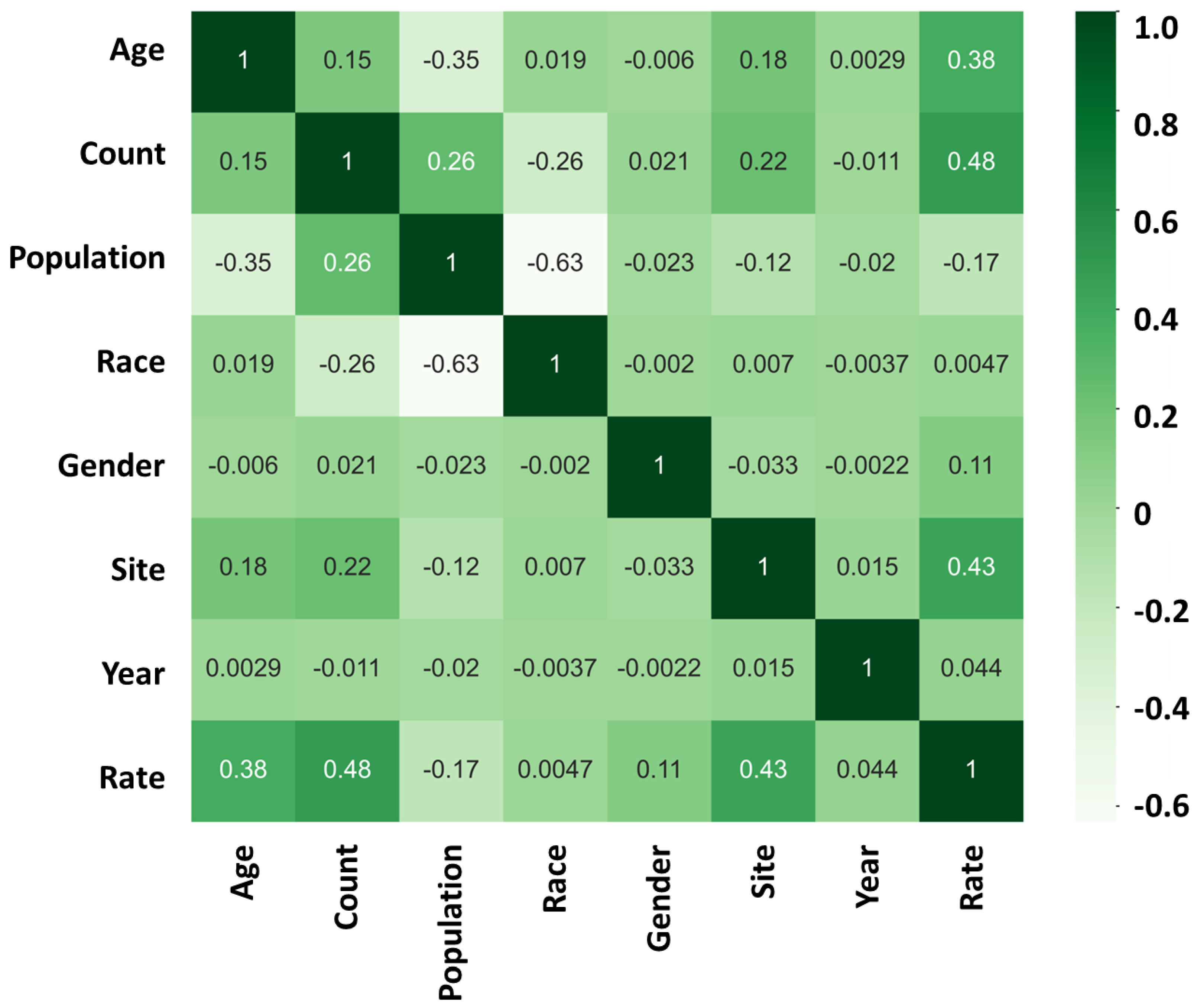

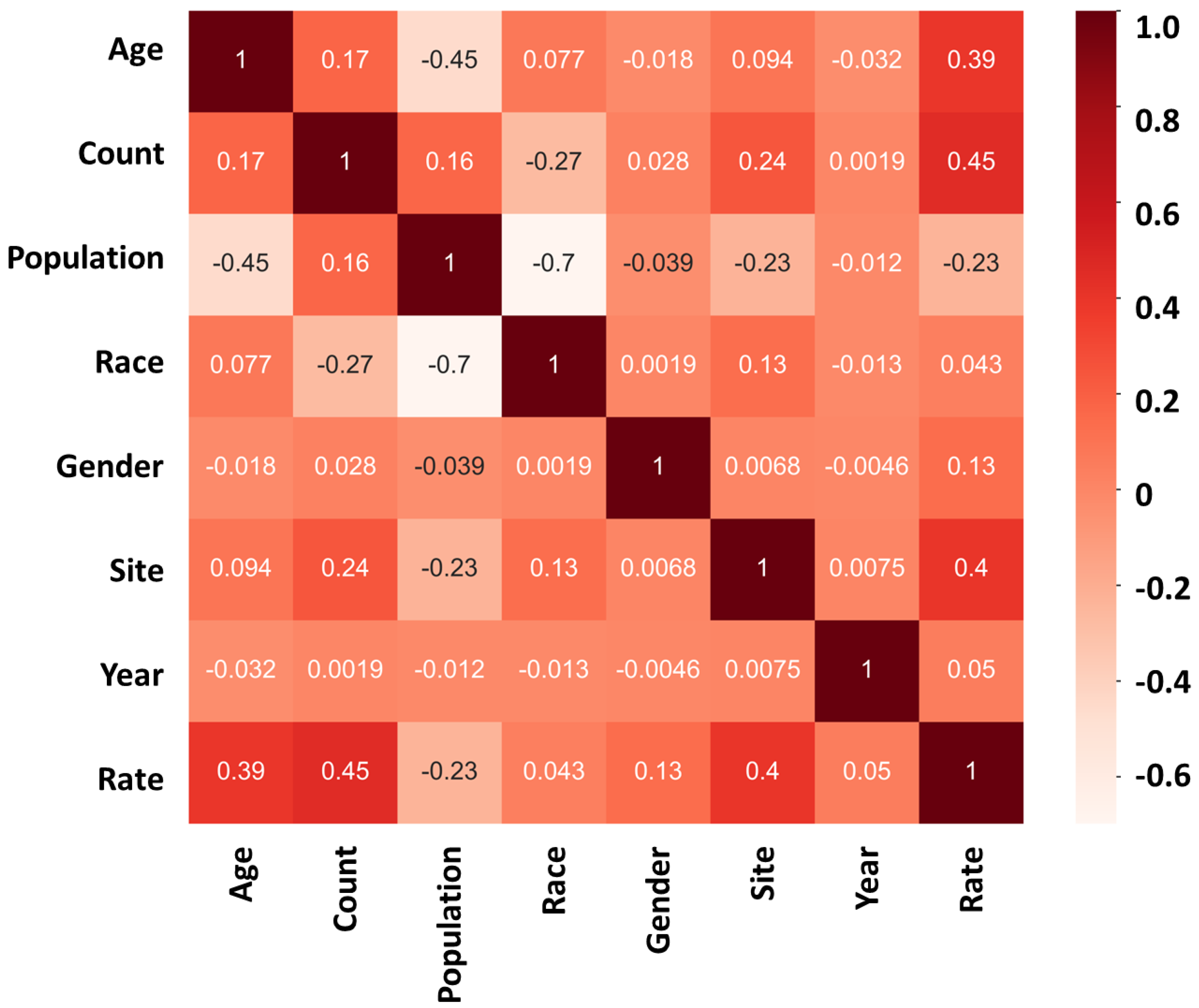

3.1. Factors affecting the cancer

3.2. Different ML models and prediction accuracy

4. Discussion

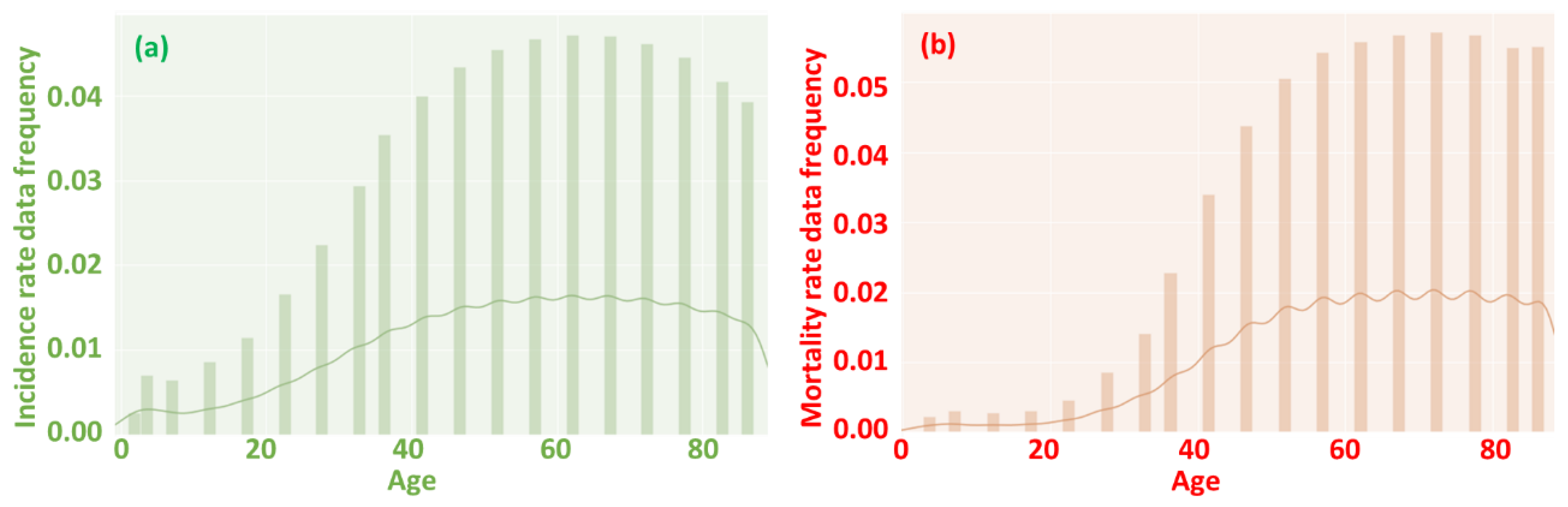

4.1. Age affecting incidence and mortality rate

4.2. Cancer of the lung, bronchus, and prostate and prevention

4.3. Future improvement on ML models

Supplementary Materials

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qawoogha, S.S.; Shahiwala, A. Identification of potential anticancer phytochemicals against colorectal cancer by structure-based docking studies. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 2020, 40, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Meng, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Jin, T. Mortalin promotes breast cancer malignancy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2021, 118, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolonel, L.N.; Altshuler, D.; Henderson, B.E. The multiethnic cohort study: exploring genes, lifestyle and cancer risk. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, J.; Duffy, S.W.; Cuzick, J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat. Med. 2004, 23, 1111–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, A.C.; Easton, D.F. Risk prediction models for familial breast cancer. 2006.

- Chen, S.; Ding, Y. Machine Learning and Its Applications in Studying the Geographical Distribution of Ants. Diversity 2022, 14, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, Y. A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Academic Performance in Pennsylvania’s Schools. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X. Development of the growth mindset scale: Evidence of structural validity, measurement model, direct and indirect effects in Chinese samples. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabartha, M.; Durand, A.; Francois-Lavet, V.; Pineau, J. Handling black swan events in deep learning with diversely extrapolated neural networks. 2021; pp. 2140–2147.

- Cruz, J.A.; Wishart, D.S. Applications of machine learning in cancer prediction and prognosis. Cancer Inform. 2006, 2, 117693510600200030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lam, K.-M.; Deng, Z.; Choi, K.-S. Prediction of mortality after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer by machine learning techniques. Comput. Biol. Med. 2015, 63, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Center, M.M.; Ferlay, J.; Ward, E.; Forman, D. Global cancer statistics. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, S.E. Rating the risk factors for breast cancer. Ann. Surg. 2003, 237, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz Jr, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston-Martin, S.; Pike, M.C.; Ross, R.K.; Jones, P.A.; Henderson, B.E. Increased cell division as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 7415–7421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubin, J.B.; Lagas, J.S.; Broestl, L.; Sponagel, J.; Rockwell, N.; Rhee, G.; Rosen, S.F.; Chen, S.; Klein, R.S.; Imoukhuede, P. Sex differences in cancer mechanisms. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasco, V.; Carniti, C.; Guidetti, A.; Farina, L.; Magni, M.; Miceli, R.; Calabretta, L.; Verderio, P.; Ljevar, S.; Serpenti, F. T-cell immune response after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is frequently detected also in the absence of seroconversion in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 196, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, I.; Coukos, G.; Dranoff, G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011, 480, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, A.; Matta, J.; Encarnación-Medina, J.; Ortiz-Sanchéz, C.; Dutil, J.; Linares, R.; Marcial, J.; Abreu-Takemura, C.; Moreno, N.; Putney, R. Dysregulation of DNA Methylation and Epigenetic Clocks in Prostate Cancer among Puerto Rican Men. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieker, A.J.; Gordetsky, J.B.; Maris, A.S.; Dehan, L.M.; Denney, J.E.; Arnold Egloff, S.A.; Scarpato, K.; Barocas, D.A.; Giannico, G.A. PTEN expression and morphological patterns in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Histopathology 2021, 79, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Konstantinov, S.R.; Smits, R.; Peppelenbosch, M.P. Bacterial biofilms in colorectal cancer initiation and progression. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Sabokroo, N.; Ahmadyousefi, Y.; Motamedi, H.; Karampoor, S. Immunometabolism in biofilm infection: lessons from cancer. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsonnet, J. Bacterial infection as a cause of cancer. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995, 103, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uemura, N.; Okamoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Matsumura, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamakido, M.; Taniyama, K.; Sasaki, N.; Schlemper, R.J. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Santi, R.; Tamanini, I.; Galli, I.C.; Perletti, G.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E.; Nesi, G. Current knowledge of the potential links between inflammation and prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Tessarolo, F.; Caola, I.; Piccoli, F.; Nollo, G.; Caciagli, P.; Mazzoli, S.; Palmieri, A.; Verze, P.; Malossini, G. Prostate calcifications: A case series supporting the microbial biofilm theory. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2018, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik-Rząd, B.; Zalewski, D.; Kasela, M.; Sawicki, R.; Szymańska, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Malm, A. The Landscape of Gene Expression during Hyperfilamentous Biofilm Development in Oral Candida albicans Isolated from a Lung Cancer Patient. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Vaseeharan, B.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Gopi, N.; Ekambaram, P.; Pachaiappan, R.; Velusamy, P.; Murugan, K.; Benelli, G.; Kumar, R.S. Therapeutic effects of gold nanoparticles synthesized using Musa paradisiaca peel extract against multiple antibiotic resistant Enterococcus faecalis biofilms and human lung cancer cells (A549). Microb. Pathog. 2017, 102, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnsholt, T.; Buhlin, K.; Dufrêne, Y.F.; Gomelsky, M.; Moroni, A.; Ramstedt, M.; Rumbaugh, K.P.; Schulte, T.; Sun, L.; Åkerlund, B. Biofilm formation–what we can learn from recent developments. 2018, 284, 332–345.

- Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Cohen, Y.; Cao, B. Elevated level of the second messenger c-di-GMP in Comamonas testosteroni enhances biofilm formation and biofilm-based biodegradation of 3-chloroaniline. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Peng, N.; Du, Y.; Ji, L.; Cao, B. Disruption of putrescine biosynthesis in Shewanella oneidensis enhances biofilm cohesiveness and performance in Cr (VI) immobilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.; Szymanski, C.; Fredrickson, J.; Shi, L.; Cao, B.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, X.-Y. In situ molecular imaging of the biofilm and its matrix. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 11244–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, X.-Y. Molecular evidence of a toxic effect on a biofilm and its matrix. Analyst 2019, 144, 2498–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cao, B.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Song, H. Enhancing bidirectional electron transfer of Shewanella oneidensis by a synthetic flavin pathway. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015, 4, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.-e.; Chen, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, V.B.; Bao, B.; Kjelleberg, S.; Cao, B.; Loo, S.C.J.; Wang, L.; Huang, W. Chemically functionalized conjugated oligoelectrolyte nanoparticles for enhancement of current generation in microbial fuel cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 14501–14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.e.; Wu, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, V.B.; Zhang, Y.; Kjelleberg, S.; Loo, J.S.C.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Q. Hybrid conducting biofilm with built-in bacteria for high-performance microbial fuel cells. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S. Mechanical performance of strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC) with bacterial addition. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2022, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Weng, Y.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Use of Genetically Modified Bacteria to Repair Cracks in Concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Influence of bacterial incorporation on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites (ECC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 196, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdany, A.H.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Visible light antibacterial potential of graphene-TiO2 cementitious composites for self-sterilization surface. J. Sustain. Cem. -Based Mater. 2022, 1-11.

- Hamdany, A.H.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Cementitious Composite Materials for Self-Sterilization Surfaces. ACI Mater. J. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdany, A.H.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Mechanical and antibacterial behavior of photocatalytic lightweight engineered cementitious composites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taninaga, J.; Nishiyama, Y.; Fujibayashi, K.; Gunji, T.; Sasabe, N.; Iijima, K.; Naito, T. Prediction of future gastric cancer risk using a machine learning algorithm and comprehensive medical check-up data: A case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jarrah, O.Y.; Yoo, P.D.; Muhaidat, S.; Karagiannidis, G.K.; Taha, K. Efficient machine learning for big data: A review. Big Data Res. 2015, 2, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Krzywinski, M.; Altman, N. Machine learning: a primer. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Tang, Y.; Kim, H.; Hasegawa, K. Machine learning with k-means dimensional reduction for predicting survival outcomes in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Inform. 2018, 17, 1176935118810215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moitra, D.; Mandal, R.K. Automated grading of non-small cell lung cancer by fuzzy rough nearest neighbour method. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2019, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessica, E.O.; Hamada, M.; Yusuf, S.I.; Hassan, M. The Role of Linear Discriminant Analysis for Accurate Prediction of Breast Cancer. 2021; pp. 340–344.

- Nguyen, T.; Khosravi, A.; Creighton, D.; Nahavandi, S. Hidden Markov models for cancer classification using gene expression profiles. Inf. Sci. 2015, 316, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Approximate number | Site | Assigned number | Year | Assigned number |

| ≤ 1 | 1 | Testis | 1 | 2019 | 1 |

| 1-4 | 3 | Hodgkin Lymphoma | 2 | 2018 | 2 |

| 5-9 | 7 | Thyroid | 3 | 2017 | 3 |

| 10-14 | 12 | Mesothelioma | 4 | 2016 | 4 |

| 15-19 | 17 | Cervix | 5 | 2015 | 5 |

| 20-24 | 22 | Brain and Other Nervous System | 6 | 2014 | 6 |

| 25-29 | 27 | Larynx | 7 | 2013 | 7 |

| 30-34 | 32 | Melanomas of the Skin | 8 | 2012 | 8 |

| 35-39 | 37 | Oral Cavity and Pharynx | 9 | 2011 | 9 |

| 40-44 | 42 | Kidney and Renal Pelvis | 10 | 2010 | 10 |

| 45-49 | 47 | Leukemias | 11 | 2009 | 11 |

| 50-54 | 52 | Esophagus | 12 | 2008 | 12 |

| 55-59 | 57 | Corpus and Uterus, NOS | 13 | 2007 | 13 |

| 60-64 | 62 | Myeloma | 14 | 2006 | 14 |

| 65-69 | 67 | Ovary | 15 | 2005 | 15 |

| 70-74 | 72 | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 16 | 2004 | 16 |

| 75-79 | 77 | Stomach | 17 | 2003 | 17 |

| 80-84 | 82 | Urinary Bladder | 18 | 2002 | 18 |

| 85+ | 87 | Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct | 19 | 2001 | 19 |

| Pancreas | 20 | 2000 | 20 | ||

| Female Breast | 21 | 1999 | 21 | ||

| Colon and Rectum | 22 | ||||

| Lung and Bronchus | 23 | ||||

| Prostate | 24 | ||||

| Gender | Assigned number | Race | Approximate number | Event type | Assigned number |

| Female | 1 | Non-Hispanic White | 1 | Incidence | 1 |

| Male | 2 | Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | Mortality | 2 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4 | ||||

| Hispanic of any race | 5 | ||||

| CIlower/CIupper | Approximate number | Incidence/Mortality Rate | Assigned number | ||

| [0-0.5) | 0 | [0-5) | 0 | ||

| [0.5-1.5) | 1 | [5-15) | 10 | ||

| [1.5-2.5) | 2 | [15-25) | 20 | ||

| [2.5-3.5) | 3 | [25-35) | 30 | ||

| … | … | … | … |

| Incidence rate prediction | Method | Classifier | Testing Accuracy |

| Decision tree | DecisionTreeClassifier | 57.22% | |

| Random forest | RandomForestClassifier | 57.80% | |

| Logistic regression | LogisticRegression | 50.11% | |

| SVC | SupportVectorClassifier | 49.99% | |

| Neural network | MLPClassifier | 60.82% | |

| Mortality rate prediction | Method | Classifier | Testing Accuracy |

| Decision tree | DecisionTreeClassifier | 62.11% | |

| Random forest | RandomForestClassifier | 61.68% | |

| Logistic regression | LogisticRegression | 54.53% | |

| SVC | SupportVectorClassifier | 55.72% | |

| Neural network | MLPClassifier | 63.10% |

| Scheme 100. | Reported incidence rate per 100’000 | Reported death rate per 100’000 |

|---|---|---|

| Testis | 6.109 | 0.416 |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 3.357 | 1.052 |

| Thyroid | 15.838 | 2.675 |

| Mesothelioma | 5.771 | 5.176 |

| Cervix | 14.571 | 6.23 |

| Brain and Other Nervous System | 7.758 | 7.599 |

| Larynx | 14.946 | 7.642 |

| Melanomas of the Skin | 26.591 | 8.439 |

| Oral Cavity and Pharynx | 21.866 | 9.773 |

| Kidney and Renal Pelvis | 34.078 | 15.238 |

| Leukemias | 20.492 | 15.742 |

| Esophagus | 16.881 | 16.278 |

| Corpus and Uterus, NOS | 46.417 | 16.556 |

| Myeloma | 25.058 | 18.811 |

| Ovary | 20.202 | 19.706 |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 33.855 | 19.849 |

| Stomach | 31.179 | 21.067 |

| Urinary Bladder 18 | 58.880 | 23.543 |

| Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct | 31.211 | 28.477 |

| Pancreas | 40.685 | 40.167 |

| Female Breast | 137.875 | 51.988 |

| Colon and Rectum | 113.632 | 55.407 |

| Lung and Bronchus | 169.056 | 139.842 |

| Prostate | 429.041 | 169.678 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).