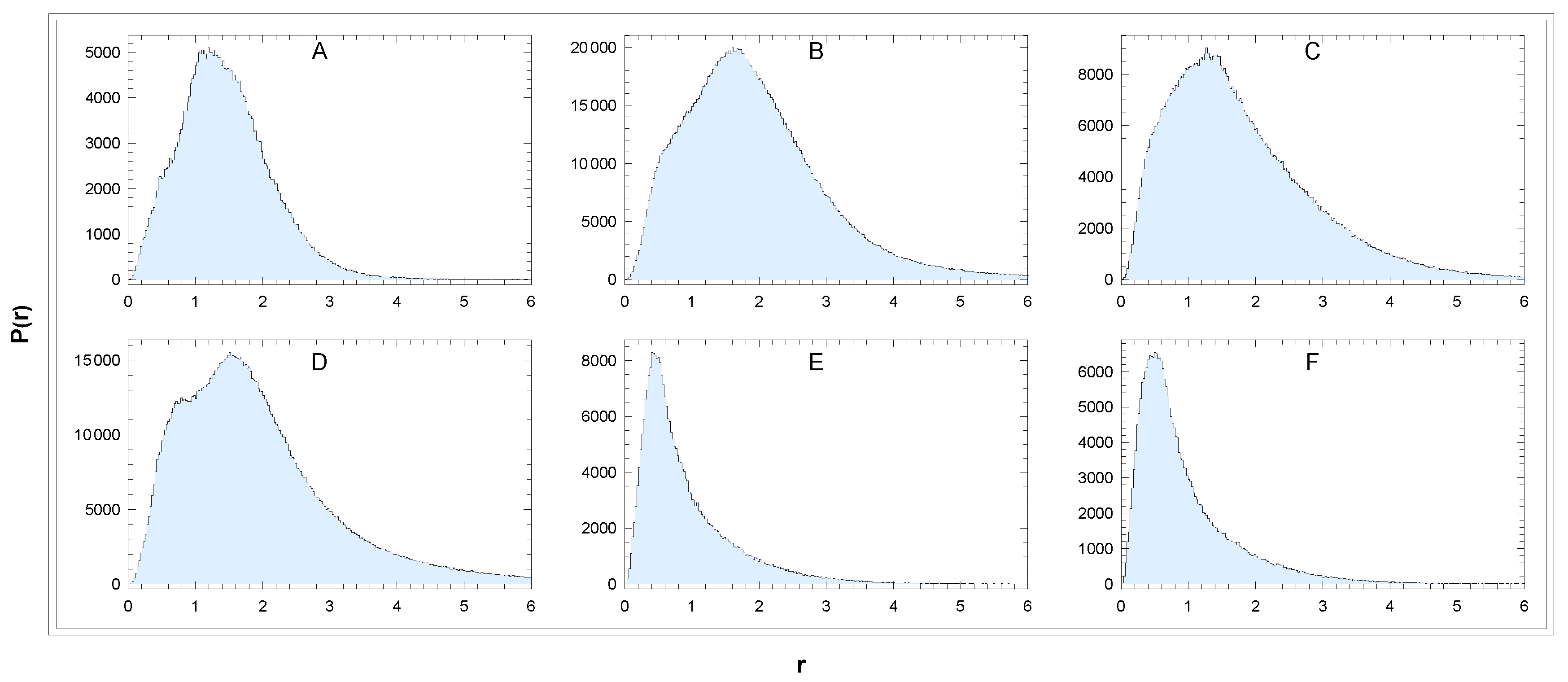

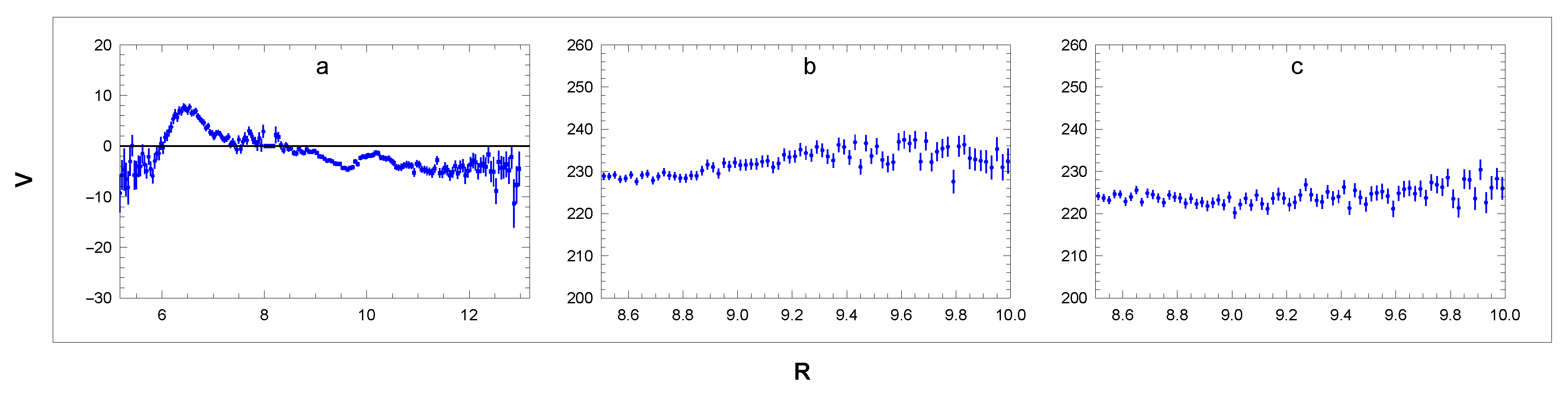

Figure 3.

Distribution of distances in the sectors A-F. Unit: r[kpc]. Binning: 0.024kpc.

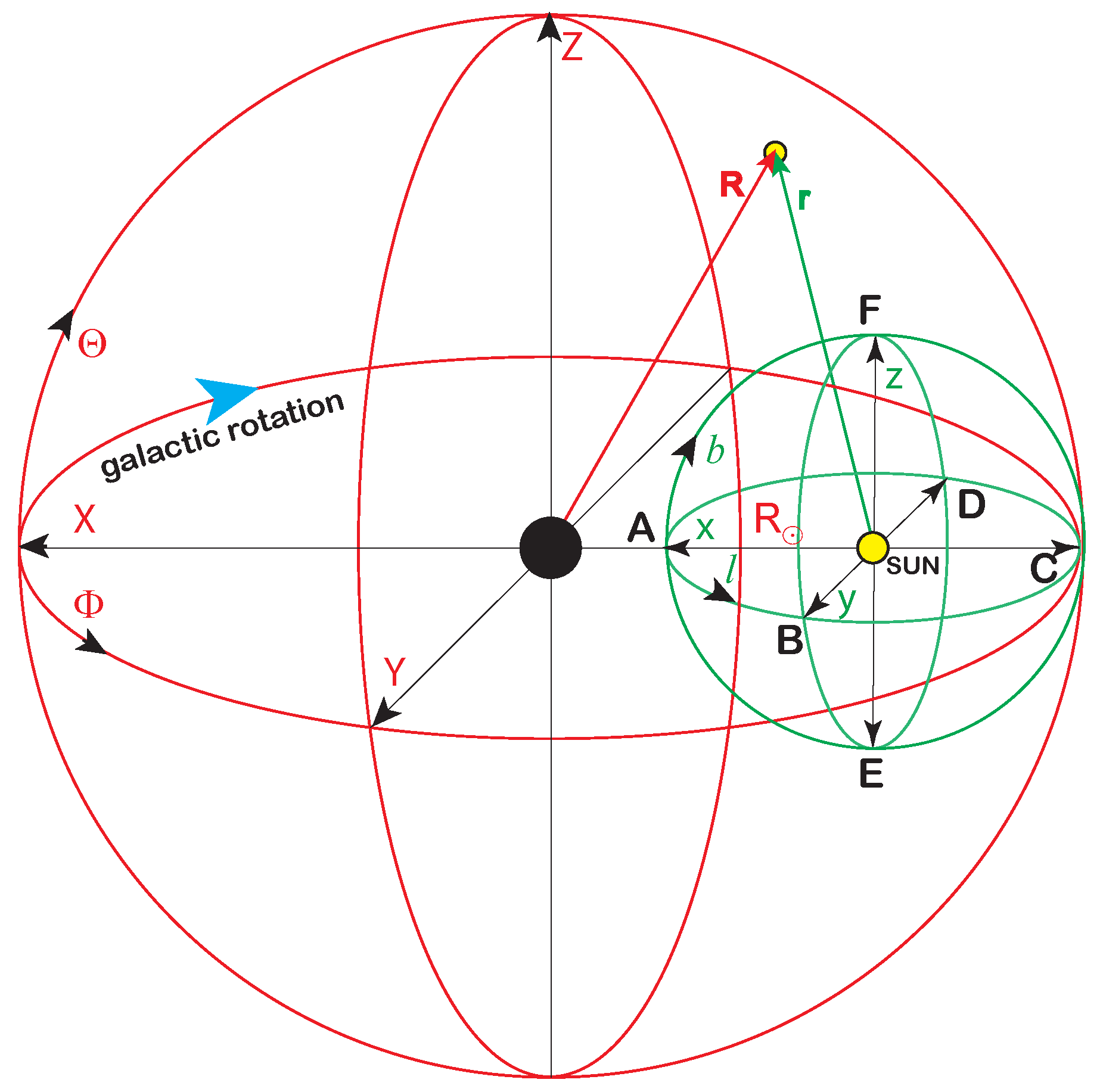

3.1. Velocity of the Sun

According to (

8) and (

15) the Sun’s velocity can be decomposed as

where

is the LSR velocity and

is the Sun’s velocity in the LSR frame. How can these velocities be determined? In the galactic reference frame the star velocity

is given as

which implies

The region of averaging

should be reasonably wide to suppress the influence of local fluctuations on the obtained average, then the first two terms cancel and for the local Sun’s velocity we obtain

For its calculation, we use the projections of galactic velocities (

12) in sectors A-D shown in

Figure 4 together with the relations

where the vectors of local orthonormal basis

are defined in (7). In the sectors considered, we get:

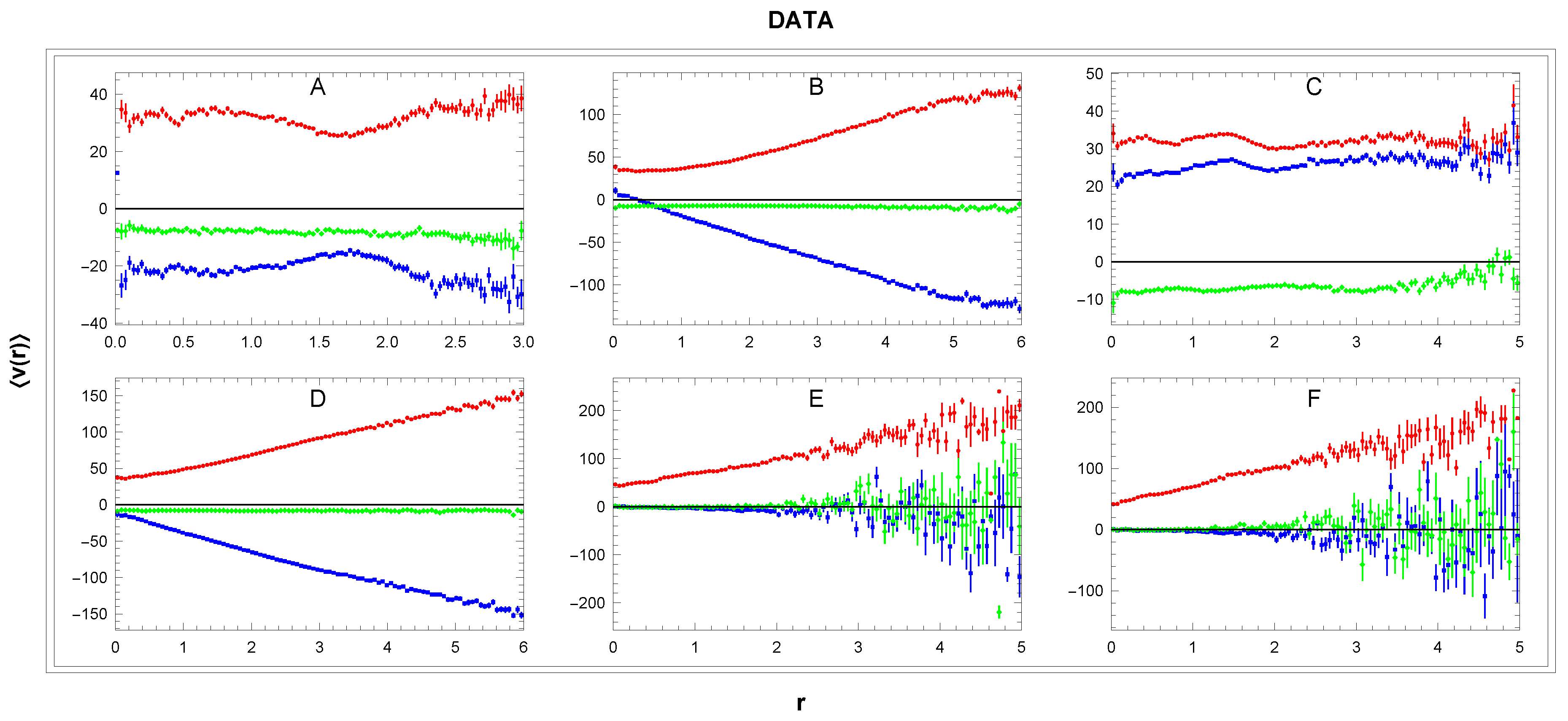

Figure 4.

Dependence of mean velocity ( - blue, - green, - red) on distance r in the galactic reference frame in sectors A-F. Cut . Units: r[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 4.

Dependence of mean velocity ( - blue, - green, - red) on distance r in the galactic reference frame in sectors A-F. Cut . Units: r[kpc], v[km/s].

1)

in the sectors A-D Since in these sectors we have

so we can identify

. The mean values

depending on distance

r are for individual sectors shown in

Figure 4. The velocity

is the average

where

means the region of averaging, which are the stars in the sectors A-D and radius

. The resulting curve is shown in

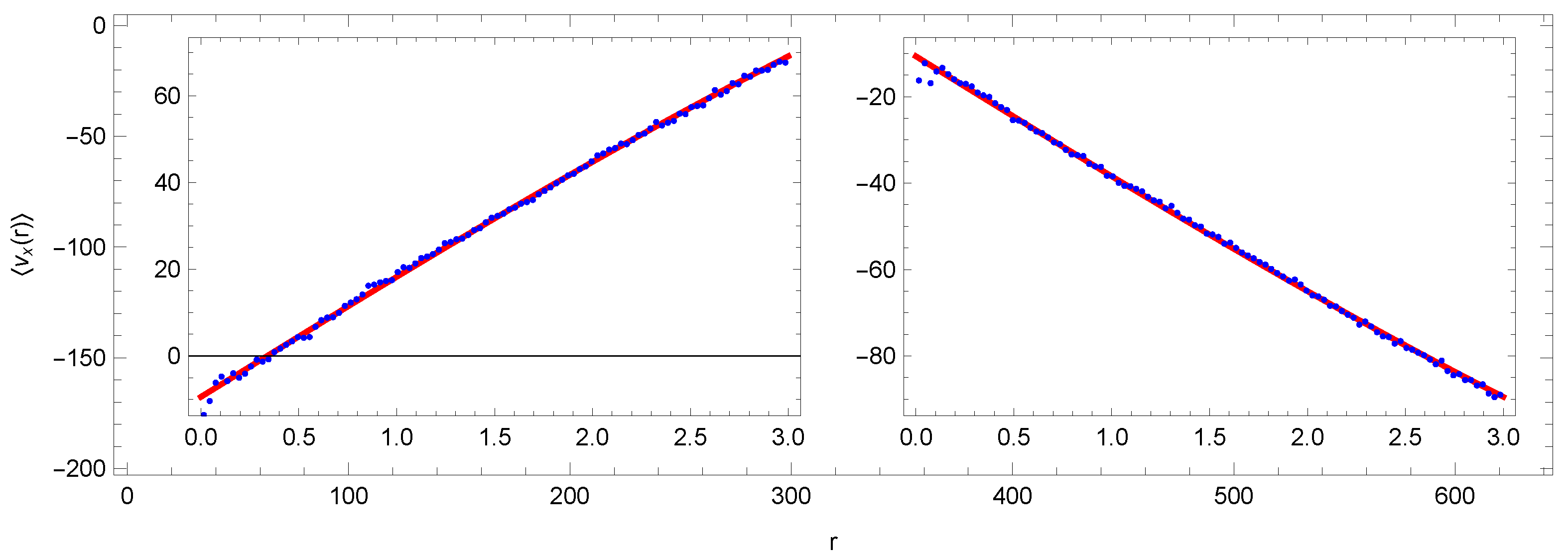

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Velocities (blue) and (green) as the functions of (left) with corresponding statistical errors (right). Cut . Units: [kpc], [km/s].

Figure 5.

Velocities (blue) and (green) as the functions of (left) with corresponding statistical errors (right). Cut . Units: [kpc], [km/s].

2)

in the sectors A and C In these sectors we have

, so we identify

in the A and

in the C sector. The corresponding curves

are in panels A,C (

Figure 4) and curve

is in

Figure 5. The region of averaging are sectors A and C up to the distance

3)

and

in the sectors B and D Here we have

so we can identify

in the sector B and

in the D sector. In panels B,D in

Figure 4 we show corresponding

curves. For small

r we have

, which implies for B,D sectors

but what is the reason for the steep slope of

as

r increases? In the considered sectors, the mean value

includes a significant contribution from the collective rotation velocity

proportional to

r, as explained below (

Figure 9 and Eq.(

43)). Thus, in B,D sectors we have

and correspondingly

The two curves

are shown in

Figure 6 together with the curve produced by fitting the free parameters

and

in the range

kpc. Assuming that rotation velocity is constant in these sectors,

, we obtain very good agreement of the fit to the data. In the next we abbreviate

by

. The obtained velocities are:

Admittedly, there is a weak dependency [

18,

39]

however the range

kpc means that

, which is too small a range for reliable fit involving

.

Figure 6.

Curves (

29): data (

blue) and fit (

red). Cut

. Units: r[kpc],

[km/s].

Figure 6.

Curves (

29): data (

blue) and fit (

red). Cut

. Units: r[kpc],

[km/s].

In the left panel of

Figure 5 we observe nearly constant curves, while the right panel shows dependence of corresponding statistical errors. The range of distances

involves the dominant part of analyzed stars in sectors A-D. To estimate the Sun’s local velocity

, we take the values in the middle of the range

. The velocities

and

are obtained as averages of the values in (

30).

However, for consistent comparison with other analyses, the velocities

and

can require further correction based on the calculation of asymmetric drift (see [

14], Sec.11):

where

is the MW circular velocity at

and

is a mean orbital velocity of the stars in neigborhood of the Sun. The Sun orbital velocity

in the Galactocentric frame can be decomposed alternatively as

so

The study [

49] estimates the asymmetric drift

around the Sun’s position to be about 6 km/s. A very similar value can be extracted from

Figure 3 in the paper [

40], where the parameter

is replaced by our parameter

km

2s

−2, which is calculated in

Section 3.3, (

Table 4). In the standard notation, we can identify

where

and

are the averages of the corresponding values in (

30). We have:

The associated velocities

and

are shown in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Local velocity of the Sun, mean rotation velocity and circular velocity along with the results of other analyses. Units: [km/s].

Table 3.

Local velocity of the Sun, mean rotation velocity and circular velocity along with the results of other analyses. Units: [km/s].

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ref. |

|

|

|

228 |

234 |

|

|

this work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[40] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[11] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[43] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[17] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[39] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[12] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[32] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[28] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[18] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[13] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[41] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[37] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[20] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[33] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[48] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[26] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[27] |

Their systematic uncertainties are estimated as follows. For velocities are defined by the range of variability of the curves in the left panel in interval kpc. For velocities and systematic uncertainty is estimated from a set of fits in different intervals of distances . The relatively small systematic uncertainty in reflects the relatively small local variations.

3.2. Rotation Curves

From now, we will substitute galactic velocity

in (

21) by

, which is the velocity related to the LSR:

In this frame, the input data (

12) are modified with the use of our

as

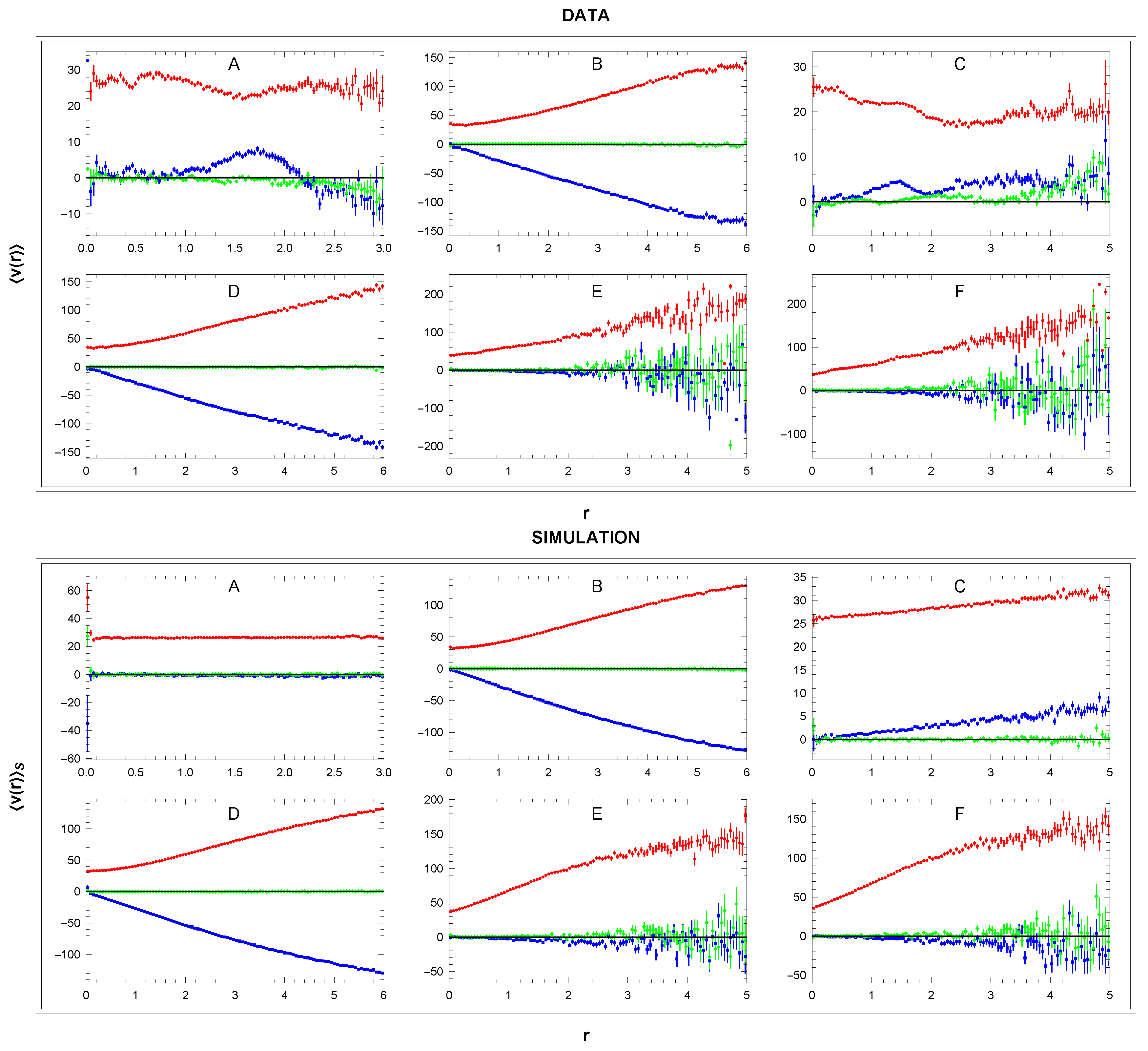

After this substitution,

Figure 4 is replaced by the top panel in

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Dependence of mean velocity (

- blue,

- green,

- red) on distance

r in the local rest frame at

in sectors A-F. For panel DATA we used cut

. For panel SIMULATION see

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4. Units: r[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 7.

Dependence of mean velocity (

- blue,

- green,

- red) on distance

r in the local rest frame at

in sectors A-F. For panel DATA we used cut

. For panel SIMULATION see

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4. Units: r[kpc], v[km/s].

The new

refer to the LSR whose velocity is

The combination of the new panels A and C, which represents the RC is shown in

Figure 8a.

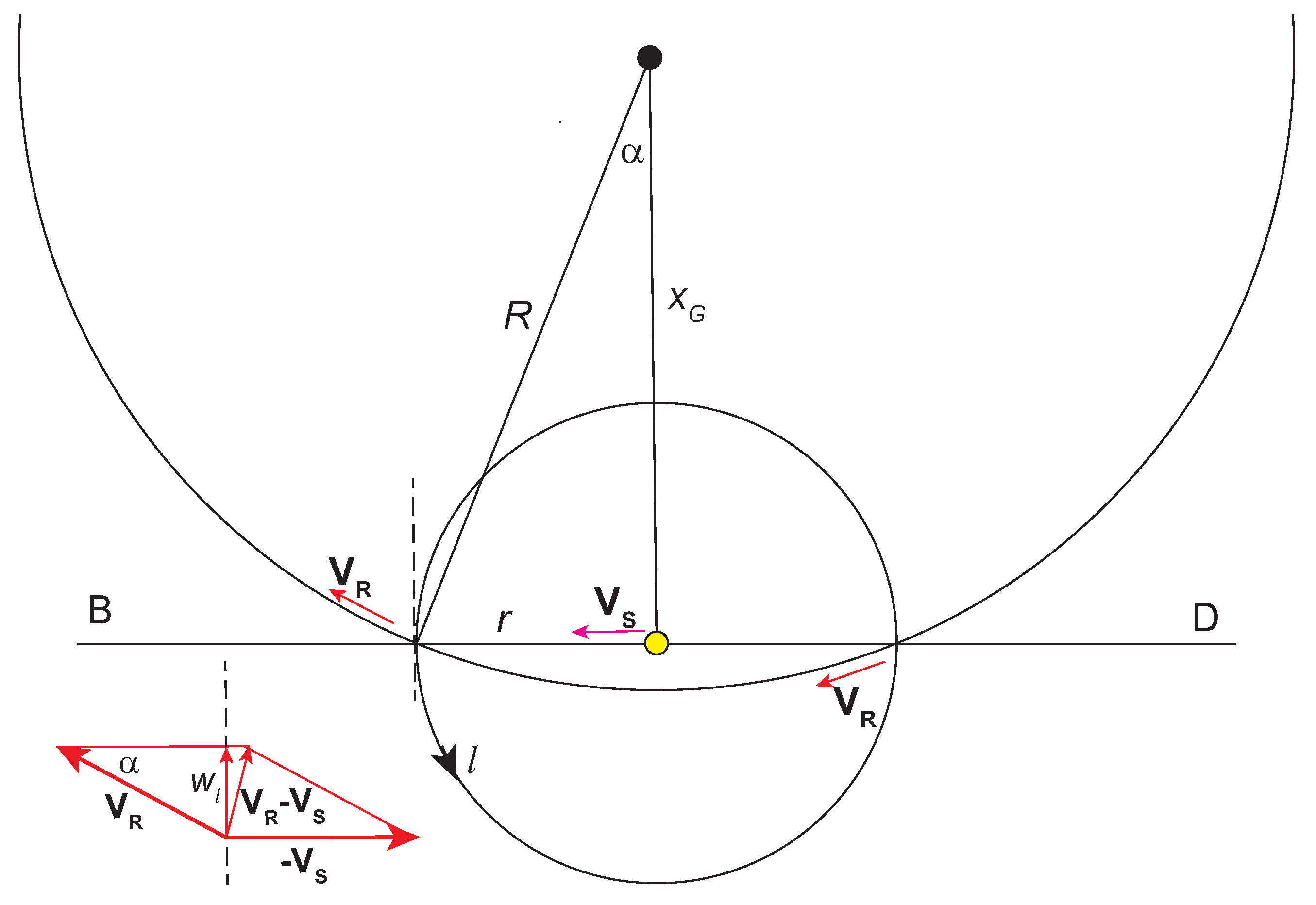

Figure 8.

Velocity curves in sectors A+C (panel (a)) and in sectors B and D (panels (b) and (c)). For panel (a) we used cut . Units: R[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 8.

Velocity curves in sectors A+C (panel (a)) and in sectors B and D (panels (b) and (c)). For panel (a) we used cut . Units: R[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 9.

Rotation of MW as seen in sectors B and D. Here the symbols and stand for and

Figure 9.

Rotation of MW as seen in sectors B and D. Here the symbols and stand for and

Another representation of the RC is obtained from panels B and D. For

and

the term

in Eq.(38) and its transverse projection

are calculated as suggested in

Figure 9 from two similar orthogonal triangles with angle

We obtain

Since

, we get

The corresponding RCs are shown in panels b,c of

Figure 8. These curves are a different representation of the

curves in panels B and D of

Figure 7.

Relation (

43) holds only for sectors B and D, where

and

(or

). In the general case, the geometry is more complicated. With the use of (

24) and (38) we have

This relation can be modified as

With the use of relations (

6),(

3) and (

1, vector

can be expressed in galactic coordinates

and after a few further modifications, we get

and if

, then

One can check that in sectors B and D, where

,

and where we have assumed

, relation (

47) reduces to (

43). Relation (

48) allows us to analyze

not only in narrow sectors B and D but also in the wider regions, which can provide higher statistics with smaller errors. This relation is not suitable for the reconstruction of

in the vicinity of singularity

. In

Figure 10

(blue points) we show RCs obtained with the use of (

48) in the sectors Q

2 and Q

4. In the analyzed area we observe irregular fluctuations in the rotation velocity:

. The relation allows us to calculate rotation velocity not only in the galactic plane, but also outside the plane. In

Figure 11

we show the velocity curves calculated in sectors and .

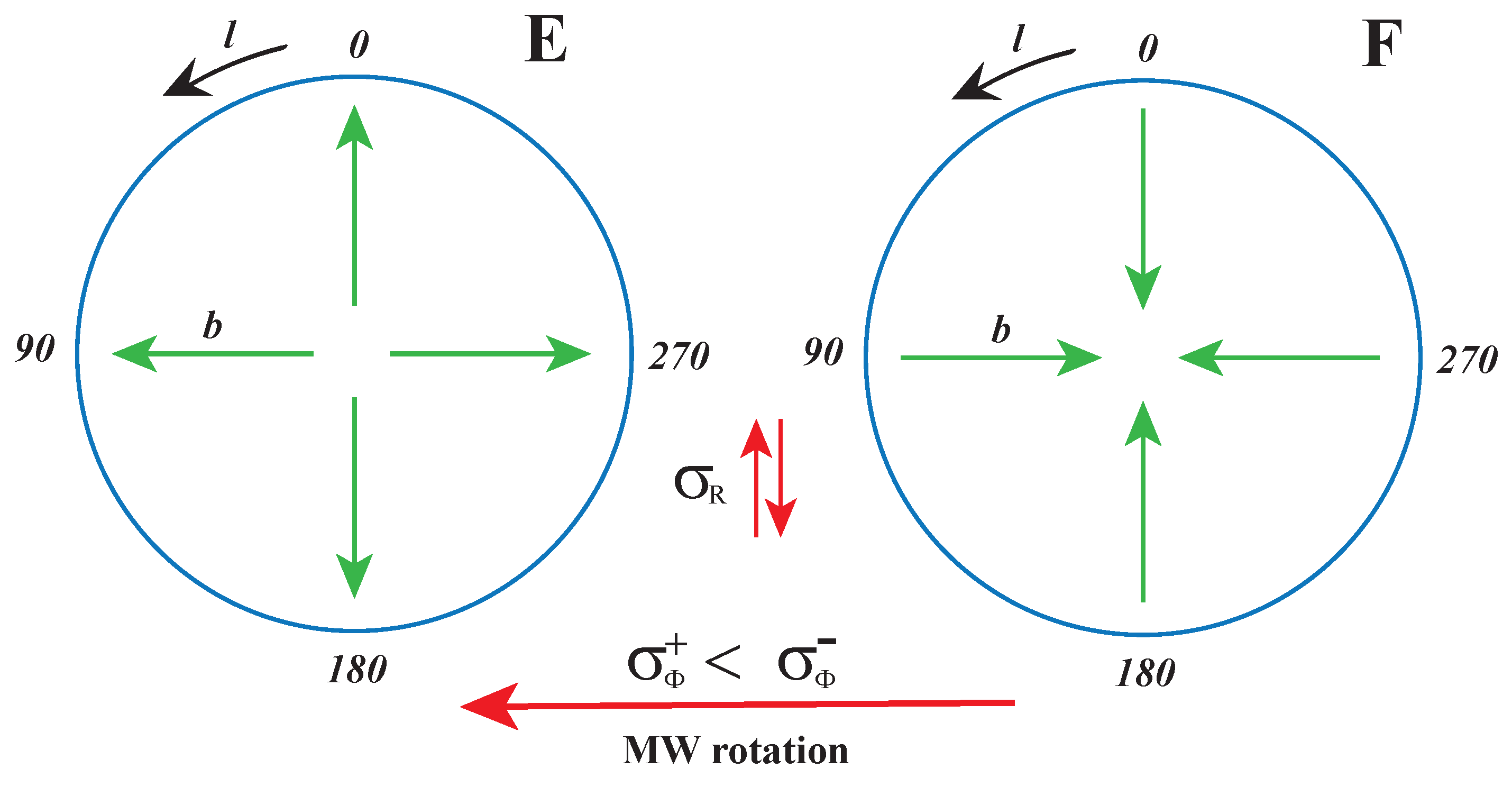

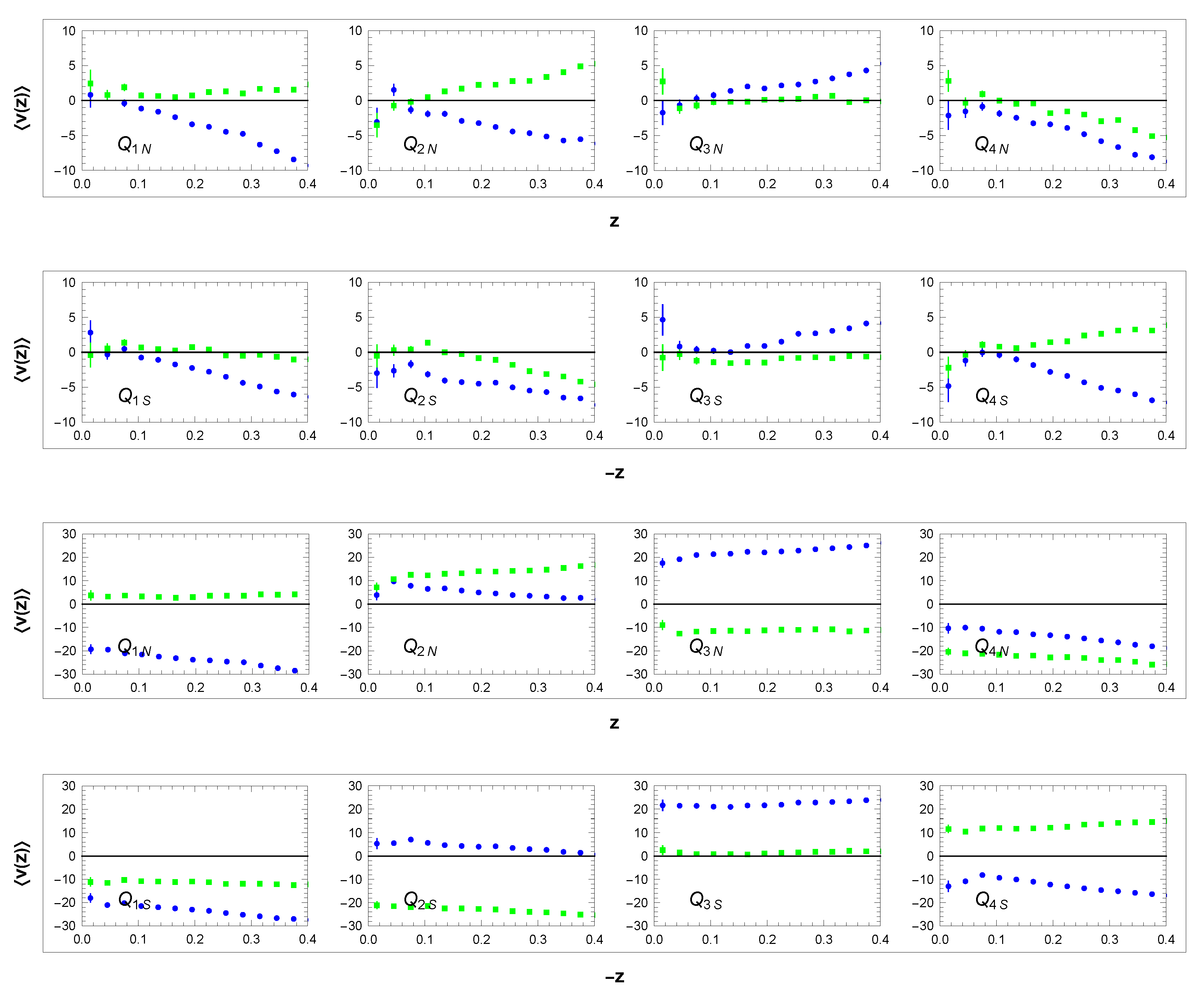

3.3. Six Parameters of the MW Collective Rotation

Panels E and F at the top of

Figure 7 provide further important information. We observe

and

, as expected in both narrow cones pointing perpendicularly from the galactic plane, where positive and negative

are equally abundant. On the other hand, the value

increases with distance from the plane. This increase occurs in the galactic reference frame reflecting the slowing of collective rotation in the Galactocentric frame, which increases with

. The same effect is seen even more clearly in

Figure 11. Important information is obtained from

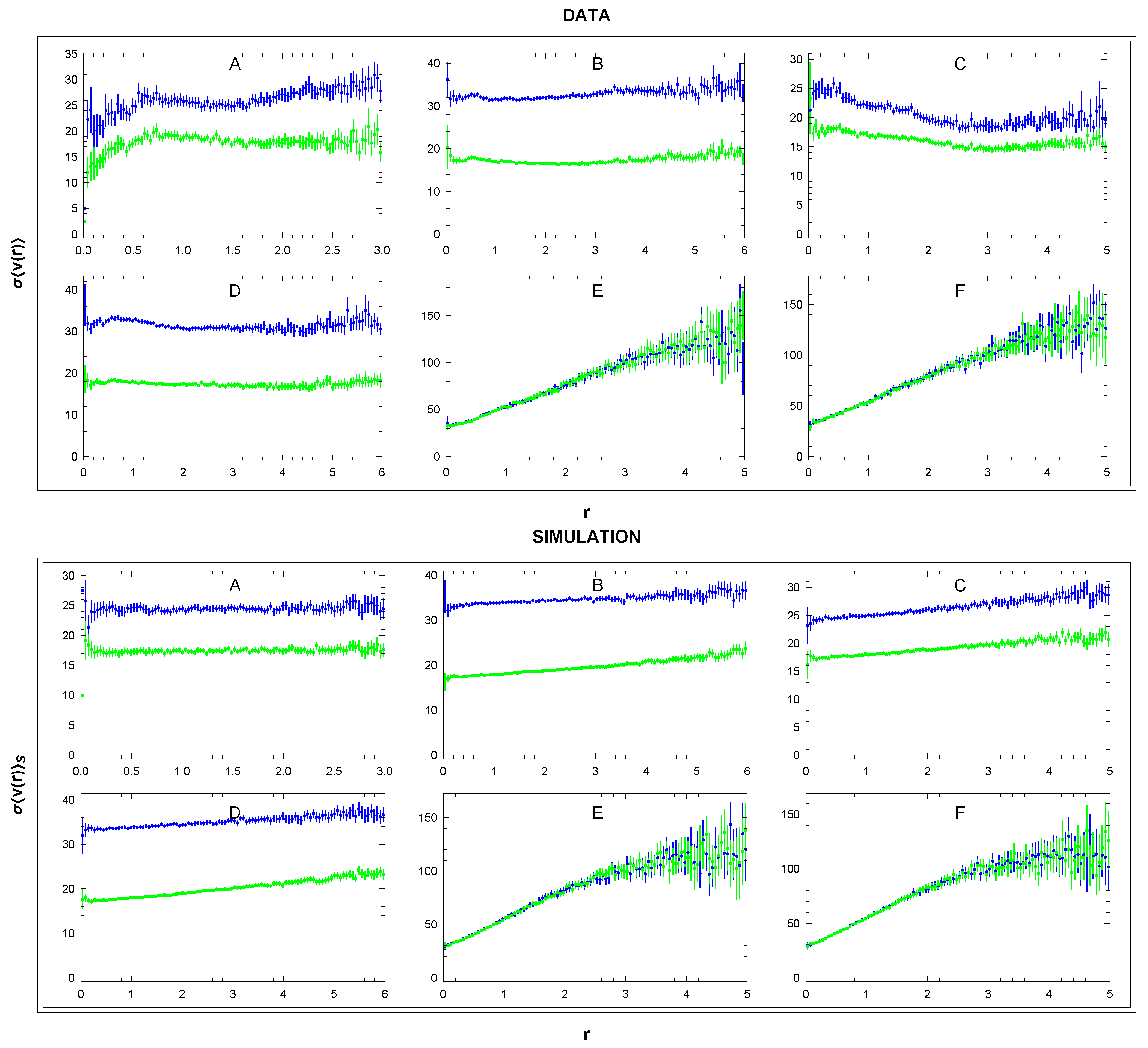

Figure 12,

where dependencies of standard deviations are shown. The increasing standard deviations in panels E and F suggest a less collective, but more disorderly motion of high velocities away from the galactic plane.

In the distribution (

16), we assume in a first approximation:

where

and

are the free parameters. We proceed as follows in their setting:

i) From the data panels A-D in

Figure 12 where

, we estimate

In directions other than A-D, the relations between

’s in the galactic and Galactocentric frames are more complex. The data panels E and F (where

), show in the region of the peaks (

kpc, see

Figure 3, panels E,F) a linear increase of the corresponding mixture of

’s with

.

ii) To obtain the parameters

, we analyzed the respective distributions in all the sectors listed in

Table 1. We found that the optimal shape of the distribution

in (

16) is asymmetric, having different

for the two opposite orientations, where

means

in (against) the rotation direction:

Thus, only

depends on

. This asymmetry also reflects the effective deceleration

of the collective rotation for larger

as mentioned above. We have

After integration we get

The parameter

is obtained by the fit from

Figure 11, which suggests dependence

For the remaining two parameters, the analysis showed that

is a good approximation. We denote

, this last free parameter was set up from the tuning of the slope in simulation panels E and F in

Figure 12. A list of the six resulting parameters controlling simulation (

16) is given in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Monte-Carlo simulation model parameters and corresponding parameters from other analyses. Velocity

is taken from

Table 3.

Table 4.

Monte-Carlo simulation model parameters and corresponding parameters from other analyses. Velocity

is taken from

Table 3.

|

|

|

|

|

|

ref. |

| 17 |

24 |

33 |

20 |

42 |

228 |

this work |

|

|

|

x |

x |

x |

[2] |

| 11 |

20 |

31 |

x |

x |

x |

[45] |

The relation (

56) shows that the MW rotation at

kpc is

km/s lower than at

, which is significantly less than the total error in determining

. Therefore, we have neglected

in our calculation. The Wolfram Mathematica code of the generator is available on the website

https://www.fzu.cz/~piska/Catalogue/genkinFEB24.nb.

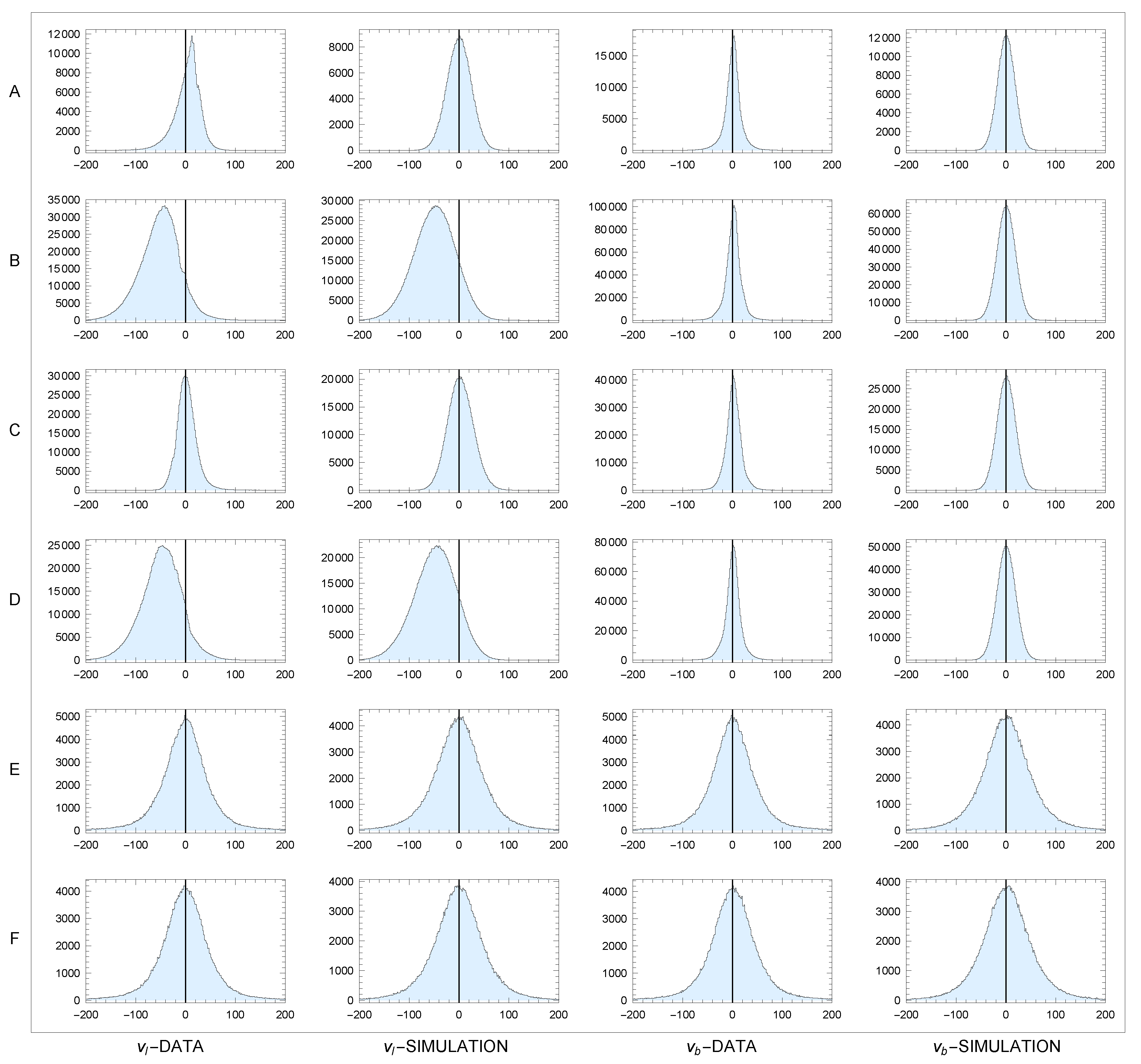

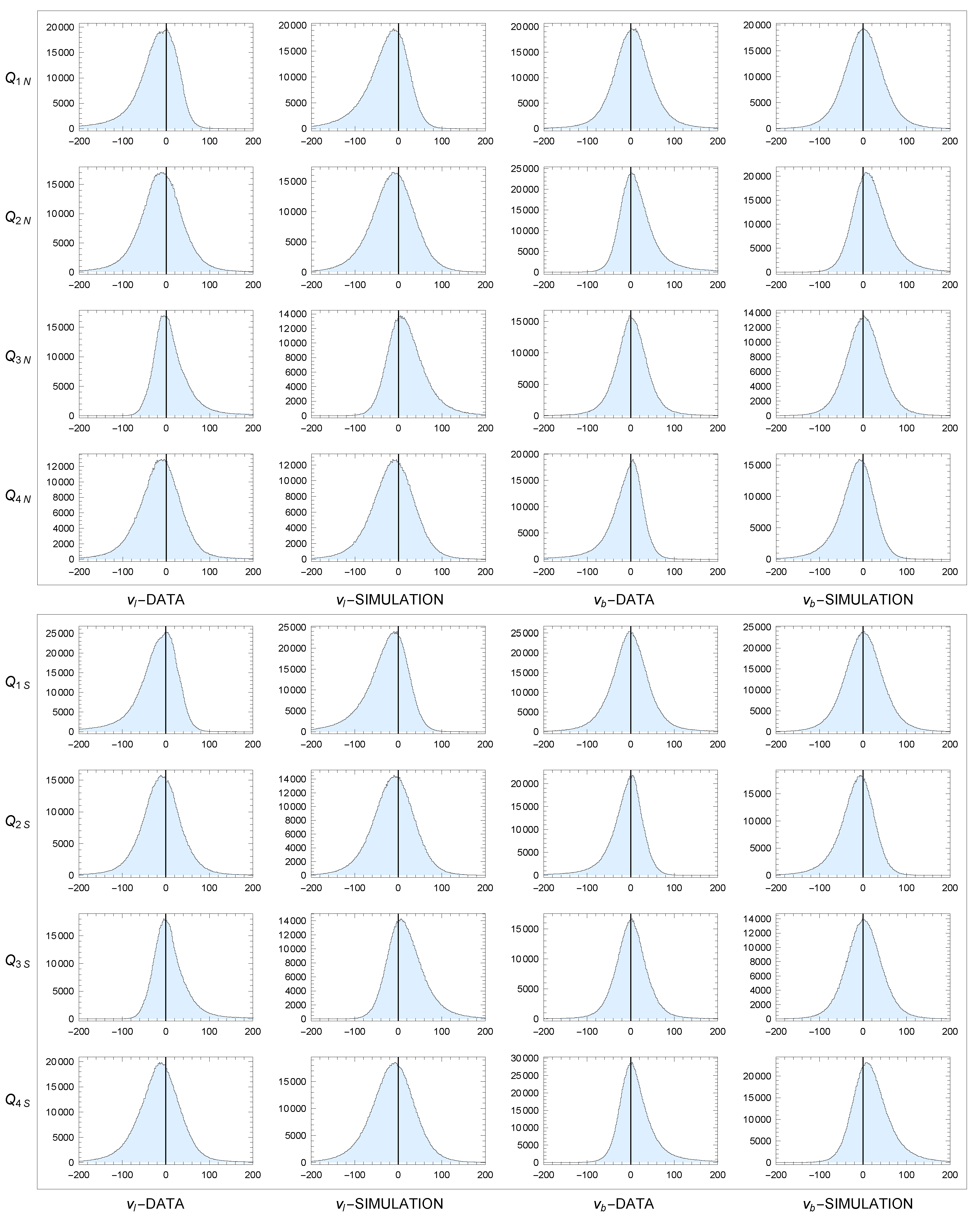

Figure 13

shows the examples of the distribution of simulated velocities and . The simulated distributions and are symmetric for any , distribution is asymmetric for .

3.4. Comparison of Simulation Model with Data

The comparison is done as follows:

1) Position

of the source in the galactic reference frame is with the use of Eqs.

3 transformed to the Galactocentric spherical frame

. For this position, the velocity

defined by (

14) is generated according to distribution (

16) with the parameters from

Table 4.

2) Using (

41) and (7) we get the corresponding LSR transverse velocities:

So for any source defined by input

we generate a vector

and then create the desired distributions from both.

3) These distributions obtained from the input data and simulations will now be compared. The comparison in

Figure 7 shows perfect agreement between data and simulation for panels B,D,E,F. In panels A and C, the simulation model does not reproduce local kinematic substructures generating deviations

km/s. The presence of these substructures shows the precision with which we work. At the same time, the fluctuations are not noticeable in the other panels because their velocity scale is coarser.

The simulation in panel C indicates that the velocity increases with r, despite the constant parameter . This small effect is because we are working inside the angle deg, which means a slight linear increase in average and correspondingly some deceleration with r. So, a corresponding correction would therefore be necessary to evaluate the RC in this sector more accurately. We have checked that for smaller angles this effect disappears. At the same time, we do not observe a similar effect in sector A. The reason is that in a very dense field of this sector our cuts and accept only a narrow sector of the data: deg.

Figure 12 shows the corresponding velocity dispersion dependencies. In the upper panels A-D we again observe fluctuations that are not present in the simulation. In panels E,F with a coarser scale the fluctuations are not noticeable. Averaged data in panels A-D were together with panels E,F used to determine parameters

in

Table 4. After averaging the fluctuations the simulation model fits the data well.

Relatively small velocity fluctuations (

km/s,

) also appear in the RC in

Figure 10. The slightly decreasing simulated RC is due to the shape of the sectors

and

, where a larger

R correlates with a larger average

, implying smaller

.

Figure 11 shows that the simulation of decreasing

controlled by the fitted parameter

in Eq.(

56) agrees well with the data.

The good agreement of the simulations with the data is confirmed by other results.

Figure 14.

Distributions of and in sectors A-F: data and simulation model. Unit: v[km/s]. Binning: 1.6 km/s.

Figure 14.

Distributions of and in sectors A-F: data and simulation model. Unit: v[km/s]. Binning: 1.6 km/s.

Figure 15.

Histograms and in sectors E and F: data and simulation.Units: l[deg], v[km/s]. Binning : deg km/s km/s.

Figure 15.

Histograms and in sectors E and F: data and simulation.Units: l[deg], v[km/s]. Binning : deg km/s km/s.

Figure 16.

Asymmetry

in the Galactocentric reference frame generates asymmetries in the galactic frame, see text and

Figure 15.

Figure 16.

Asymmetry

in the Galactocentric reference frame generates asymmetries in the galactic frame, see text and

Figure 15.

Figure 17.

Dependence of mean velocity and its dispersion ( - blue, - green, - red) on distance z in sectors - and -: data and simulation model. Units: z[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 17.

Dependence of mean velocity and its dispersion ( - blue, - green, - red) on distance z in sectors - and -: data and simulation model. Units: z[kpc], v[km/s].

Figure 18.

Distributions of and in sectors , : data and simulation model. Unit: v[km/s]. Binning: 1.6 km/s.

Figure 18.

Distributions of and in sectors , : data and simulation model. Unit: v[km/s]. Binning: 1.6 km/s.

Table 5.

Correspondence of dispersions

of velocity distributions of

and

at

in sectors E,F with velocity dispersions in the Galactocentric reference frame

and

The origin of the asymmetries is suggested in

Figure 16.

Table 5.

Correspondence of dispersions

of velocity distributions of

and

at

in sectors E,F with velocity dispersions in the Galactocentric reference frame

and

The origin of the asymmetries is suggested in

Figure 16.

| sector∖l[deg] |

0 |

90 |

180 |

270 |

| E,F |

|

|

|

|

| E |

|

|

|

|

| F |

|

|

|

|

Figure 14 shows distributions of

and

in sectors A-F along with the corresponding distributions obtained from simulations. In sectors A-D we observe a narrower distribution of

, the width of which does not depend on the sector. The distributions have roughly the same dispersion for both data and simulation, but the peak in the data is sharper. The peaks in the data also have slightly longer tails, which increase the dispersion. The simulated shape is therefore only approximate. The distributions of

are slightly different. Note the shift in sectors B and D resulting from the decrease in

in upper panels B and D in

Figure 7. The distribution

DATA in sector A (where

) also has a sharper peak with an apparent asymmetry. This may be a manifestation of the asymmetric drift effect. So the simulated shape is only approximate here as well. In the opposite sector C (where

), the asymmetry is negligible. The distributions of

in both sectors A and C are copies (up to a constant shift) of the distribution of orbital velocities in the Galactocentric frame.

The important result is shown in

Figure 15. The asymmetry of histograms

and

in sectors E and F with the empty spaces reflects different projections of the asymmetry (

53). The shape of histograms can be explained using

Figure 16 and

Table 5. Distributions of

for

are controled by the parameters

in the first row of table. Their connection with

and

can be deduced from figure. At

the directions of

and MW rotation are identical, so

. But at

, the two directions are opposite, so

. At

the situation is a little more complicated. If

or

are small (which is almost our case, see panels E,F in

Figure 3, where

r), then the

direction can be approximated by vector

, so

. Similarly for

distributions controlled by

in the next rows of the table. Histograms involve integrated distributions over sectors E and F. Also here, the agreement between the data and simulation model is perfect.

Correct Monte-Carlo parameter settings can be verified in wide Q-sectors outside the area of the galactic plane.

Figure 17 shows

dependence of mean values and dispersions of velocity distributions in these sectors. The curves together with the corresponding overall distributions of velocities in broad sectors

,

in

Figure 18 again confirm the perfect agreement of the simulation with data. Note in particular the projections

in sectors

,

,

,

and

in sectors

,

,

,

. This is also due to the asymmetry (

53) that occurs for

, as illustrated by simulated

distribution in

Figure 13.