Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

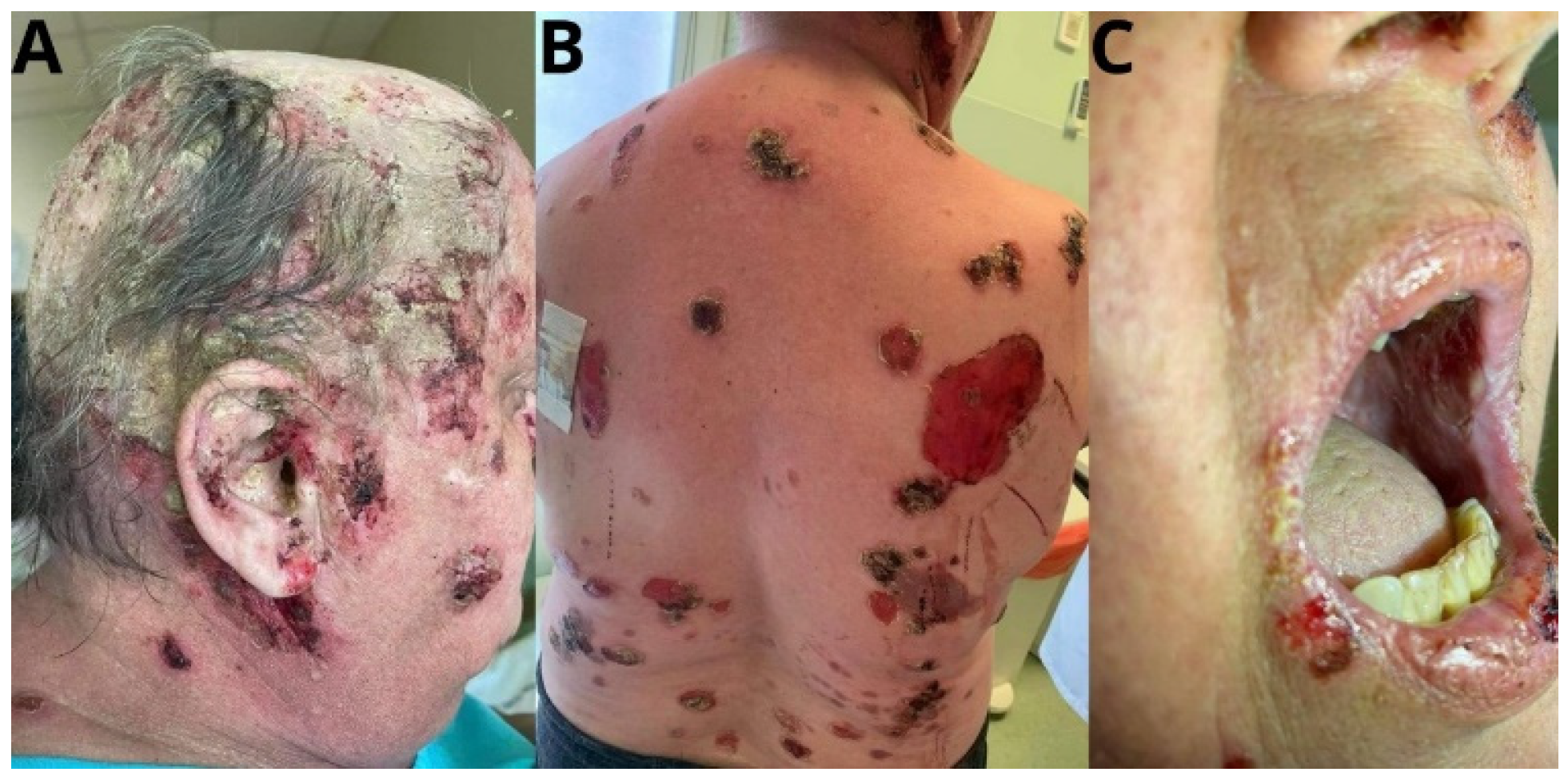

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

3. Etiopathogenesis

4. Clinical Picture

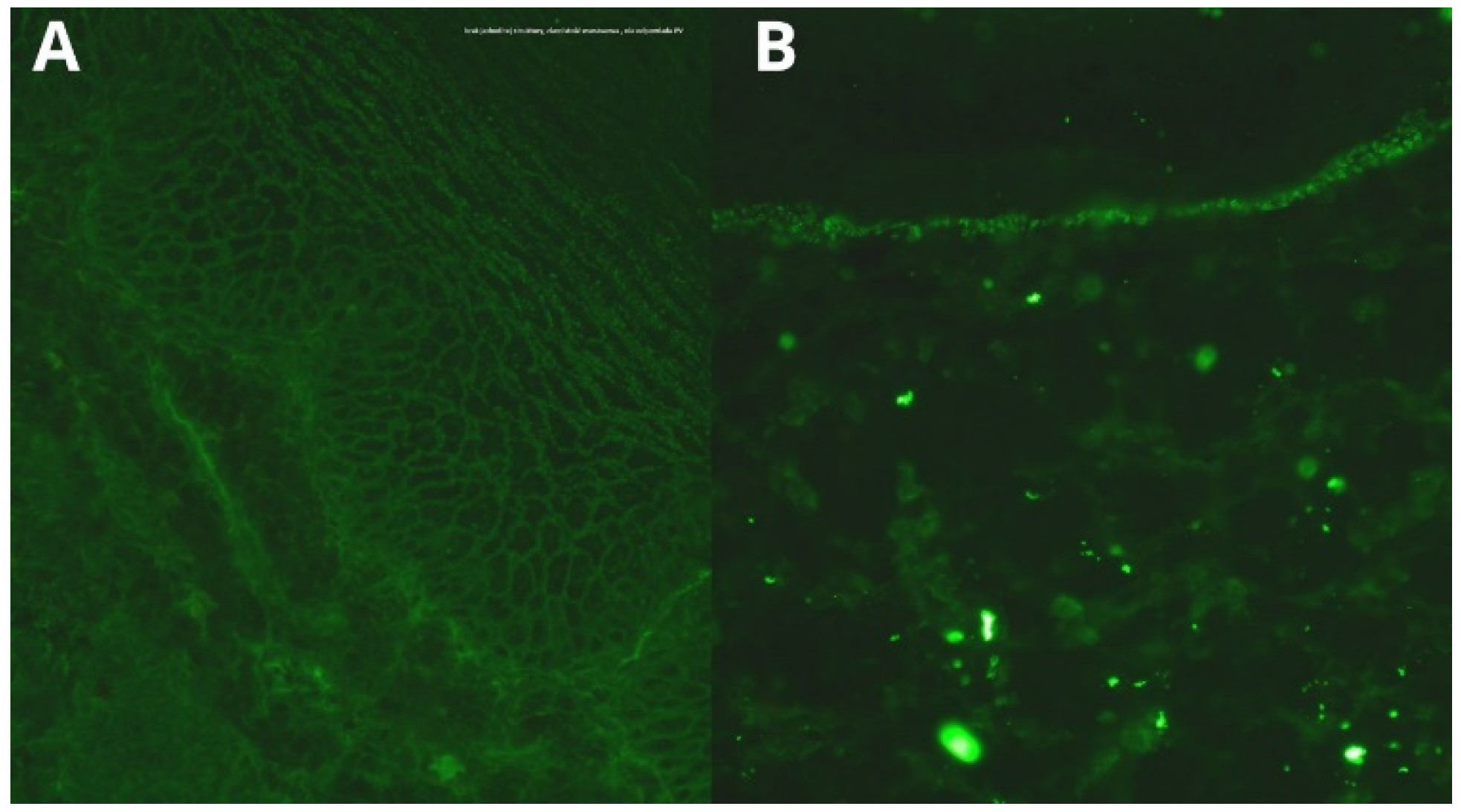

5. Diagnosis

6. Treatment

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SAIKIA NK, MACCONNELL LES. Senear-Usher syndrome and internal malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1972, 87, 1–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4557734/. [CrossRef]

- Steffen C, Thomas D. The men behind the eponym: Francis E. Senear, Barney Usher, and the Senear-Usher syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003 Oct, 25(5):432–436. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14501294/.

- Aringer M, Petri M. New classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2020, 32, 590–596. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32925250/. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed AR, Graham J, Jordon RE, Provost TT. Pemphigus: current concepts. Ann Intern Med. 1980, 92, 396–405. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6986830/. [CrossRef]

- RATTNER H, CORNBLEET T, KAGEN MS. Pemphigus Erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 1985, 24, 16–25. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1985.tb05349.x. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg FR, Sanders S, Nelson CT. Pemphigus: a 20-year review of 107 patients treated with corticosteroids. Arch Dermatol. 1976, 112, 962–970. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/820270/. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs LK, Noland MMB, Raghavan SS, Gru AA. Pemphigus erythematosus: A case series from a tertiary academic center and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2021, 48, 1038–1050. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33609053/. [CrossRef]

- Maize JC, Green D, Provost TT. Pemphigus foliaceus: a case with serologic features of Senear-Usher syndrome and other autoimmune abnormalities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982, 7, 736–741. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6757284/. [CrossRef]

- Abréu-Vélez AM, Yepes MM, Patiño PJ, Bollag WB, Montoya F. A sensitive and restricted enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting a heterogeneous antibody population in serum from people suffering from a new variant of endemic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2004, 295, 434–441. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14730452/. [CrossRef]

- CHORZELSKI T, JABLOŃSKA S, BLASZCZYK M. Immunopathological investigations in the Senear-Usher syndrome (coexistence of pemphigus and lupus erythematosus). Br J Dermatol. 1968, 80, 211–217. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4869676/. [CrossRef]

- Reich A, Marcinow K, Bialynicki-Birula R. The lupus band test in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011, 7, 27–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21339940/. [CrossRef]

- Jablońska S, Chorzelski T, Blaszczyk M, Maciejewski W. Pathogenesis of pemphigus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977, 258, 135–140. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/326203/. [CrossRef]

- Amerian ML, Ahmed AR. Pemphigus erythematosus: Presentation of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984, 10, 215–222. Available from: http://www.jaad.org/article/S0190962284700259/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez ME, Avalos-Díaz E, Herrera-Esparza R. Autoantibodies in Senear-Usher Syndrome: Cross-Reactivity or Multiple Autoimmunity? Autoimmune Dis. 2012, PMID: 23320149, Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3539423/.

- Chandan N, Lake EP, Chan LS. Unusually extensive scalp ulcerations manifested in pemphigus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2018,24, PMID: 29469763. [CrossRef]

- Henington VM, Kennedy B, Loria PR. The Senear-Usher syndrome (pemphigus erythematodes); a report of eight cases. South Med J. 1958, 51, 577–585. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13556160/. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Souto F, Sosa-Moreno F. Visual Dermatology: Pemphigus Erythematosus (Senear-Usher Syndrome). J Cutan Med Surg. 2020, 24, 190. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32208026/. [CrossRef]

- Schiavo A Lo, Puca RV, Romano F, Cozzi R. Pemphigus erythematosus relapse associated with atorvastatin intake. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014, 8, 1463. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4173814/. [CrossRef]

- Baroni A, Puca R V., Aiello FS, Palla M, Faccenda F, Vozza G, et al. Cefuroxime-induced pemphigus erythematosus in a young boy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003, 34, 708–710. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19077088/. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chen S, Wu X, Jiang X, Wang Y, Cheng H. The complicated use of dupilumab in the treatment of atypical generalized pemphigus Erythematous: A report of two cases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36798973/. [CrossRef]

- Bilgic Temel A, Ergün E, Poot AM, Bassorgun CI, Akman-Karakaş A, Uzun S, et al. A rare case with prominent features of both discoid lupus erythematosus and pemphigus foliaceus. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2019, 33, 5–7. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jdv.15099. [CrossRef]

- Sawamura S, Kajihara I, Makino K, Makino T, Fukushima S, Jinnin M, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus associated with myasthenia gravis, pemphigus foliaceus and chronic thyroiditis after thymectomy. Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2017 ,58, 120–122. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ajd.12510. [CrossRef]

- Gupta MT, Jerajani HR. Control of childhood pemphigus erythematosus with steroids and azathioprine. Br J Dermatol. 2004, 150, 163–164. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14746642/. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett EN, Hejazi E, Cusack CA. Pruritic, Pink Scaling Plaques on the Face and Trunk. Pemphigus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1123–1124. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26267852/. [CrossRef]

- Diab M, Bechtel M, Coloe J, Kurtz E, Ranalli M. Treatment of refractory pemphigus erythematosus with rituximab. Int J Dermatol. 2008, 47, 1317–1318. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19126029/. [CrossRef]

- Oktarina DAM, Poot AM, Kramer D, Diercks GFH, Jonkman MF, Pas HH. The IgG “lupus-band” deposition pattern of pemphigus erythematosus: association with the desmoglein 1 ectodomain as revealed by 3 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2012, 148, 1173–1178. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22801864/. [CrossRef]

- Makino T, Seki Y, Hara H, Mizawa M, Matsui K, Shimizu K, et al. Induction of skin lesions by ultraviolet B irradiation in a case of pemphigus erythematosus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014, 94, 487–248. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24356850/. [CrossRef]

- de Vries JM, Moody P, Ojha A, Grise A, Sami N. A Recalcitrant Case of Senear-Usher Syndrome Treated With Rituximab. Cureus. 2023, 15, 10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37954755/. [CrossRef]

- Shankar S, Burrows NP. Case 1. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004, 29, 437–438. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01588.x. [CrossRef]

- Chavan SA, Sharma YK, Deo K, Buch AC. A Case of Senear-Usher Syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2013, 58, 329. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3726916/.

- Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Sabio-Sánchez JM, Tercedor-Sánchez J, León-Ruíz L, Pérez-Alvarez F, Jiménez-Alonso J. Pemphigus vulgaris and systemic lupus erythematosus in a 46-y-old man. Lupus. 2001, 10, 824–826. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11789495/. [CrossRef]

- Thongprasom K, Prasongtanskul S, Fongkhum A, Iamaroon A. Pemphigus, discoid lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis during an 8-year follow-up period: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2013, 55, 255–258. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24042593/. [CrossRef]

- Nanda A, Kapoor MM, Dvorak R, Al-Sabah H, Alsaleh QA. Coexistence of pemphigus vulgaris with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol [Internet]. 2004, 43, 393–394. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02105.x. [CrossRef]

- Calebotta A, Cirocco A, Giansante E, Reyes O. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pemphigus vulgaris: association or coincidence. Lupus. 2004, 13, 951–953. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15645751/. [CrossRef]

- Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications, 2e | AccessAnesthesiology | McGraw Hill Medical. Available from: https://accessanesthesiology.mhmedical.com/book.aspx?bookID=2674.

- Jordon RE. “An unusual type of pemphigus combining features of lupus erythematosus” by Senear and Usher, June 1926. Commentary: Pemphigus erythematosus, a unique member of the pemphigus group. Arch Dermatol. 1982 Oct [cited 2024, 118, 723–742. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6753755/. [CrossRef]

- Maize JC, Green D, Provost TT. Pemphigus foliaceus: a case with serologic features of Senear-Usher syndrome and other autoimmune abnormalities. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet]. 1982, 7, 736–741. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6757284/. [CrossRef]

- Rutnin S, Chanprapaph K. Vesiculobullous diseases in relation to lupus erythematosus. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019, 12, 653–667. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31564947/. [CrossRef]

- Amann PM, Megahed M. Pemphigus erythematosus. Hautarzt. 2012, 63, 365–367. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22527297/.

- Hacker-Foegen MK, Janson M, Amagai M, Fairley JA, Lin MS. Pathogenicity and epitope characteristics of anti-desmoglein-1 from pemphigus foliaceus patients expressing only IgG1 autoantibodies. J Invest Dermatol. 2002, 121, 1373–1378. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14675185/. [CrossRef]

- Cornaby C, Gibbons L, Mayhew V, Sloan CS, Welling A, Poole BD. B cell epitope spreading: mechanisms and contribution to autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett. 2015, 163, 56–68. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25445494/. [CrossRef]

- Martin LK, Werth VP, Villaneuva E V., Murrell DF. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011, 64, 903–908. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21353333/. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Blistering Skin Diseases. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011, 108, 399. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3123771/. [CrossRef]

- Joly P, Horvath B, Patsatsi, Uzun S, Bech R, Beissert S, et al. Updated S2K guidelines on the management of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus initiated by the european academy of dermatology and venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, 1900–13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32830877/. [CrossRef]

- Caplan A, Fett N, Rosenbach M, Werth VP, Micheletti RG. Prevention and management of glucocorticoid-induced side effects: A comprehensive review: A review of glucocorticoid pharmacology and bone health. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017, 76, 1–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27986132/. [CrossRef]

- PASRICHA JS, SOOD VD, MINOCHA Y. Treatment of pemphigus with cyclophosphamide. Br J Dermatol. 1975, 93, 573–576. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1106754/. [CrossRef]

- Dick SE, Werth VP. Pemphigus: a treatment update. Autoimmunity. 2006, 39, 591–599. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17101503/. [CrossRef]

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, Yamagami J, Zillikens D, Payne AS, et al. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017, 11, 3, 17026. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28492232/. [CrossRef]

- Meurer M. Immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune bullous diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2012, 30, 78–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22137230/. [CrossRef]

- Beissert S, Werfel T, Frieling U, Böhm M, Sticherling M, Stadler R, et al. A comparison of oral methylprednisolone plus azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 2006, 142, 1447–1454. [CrossRef]

- SR H, RE J. Pemphigus foliaceus. Use of antimalarial agents as adjuvant therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1992, 128, 1462–1464. [CrossRef]

- PIAMPHONGSANT T. Pemphigus controlled by dapsone. Br J Dermatol. 1976, 94, 681–686. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/779820/. [CrossRef]

- Basset N, Guillot B, Michel B, Meynadier J, Guilhou JJ. Dapsone as Initial Treatment in Superficial Pemphigus: Report of Nine Cases. Arch Dermatol. 1987, 123, 783–785. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/548362. [CrossRef]

- Grcan HM, Ahmed AR. Efficacy of dapsone in the treatment of pemphigus and pemphigoid: analysis of current data. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009, 10, 383–396. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19824739/. [CrossRef]

- Campolmi P, Bonan P, Lotti T, Palleschi GM, Fabbri P, Panconesi E. The Role of Cyclosporine A in the Treatment of Pemphigus Erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 1991, 30, 890–892. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04361.x. [CrossRef]

- Tan-Lim R, Bystryn JC. Effect of plasmapheresis therapy on circulating levels of pemphigus antibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990, 22, 35–40. Available from: http://www.jaad.org/article/0190962290700042/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Chaffins ML, Collison D, Fivenson DP. Treatment of pemphigus and linear IgA dermatosis with nicotinamide and tetracycline: a review of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998, 28, 998–1000. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8496464/. [CrossRef]

- P J, M D, P M. Rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2007, 356, 521–522. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17267915/. [CrossRef]

- Jangid SD, Madke B, Singh A, Bhatt DM, Khan A, Jangid SD, et al. A Case Report on Senear-Usher Syndrome. Cureus. 2023, 15, 11. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/203747-a-case-report-on-senear-usher-syndrome. [CrossRef]

- Kunadia A, Moschella S, McLemore J, Sami N. Localized Pemphigus Foliaceus: Diverse Presentations, Treatment, and Review of the Literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2023, 68, 123. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37151255/. [CrossRef]

- Dumas V, Roujeau JC, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J, Cosnes A. The treatment of mild pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus with a topical corticosteroid. Br J Dermatol. 1999, 140, 1127–1129. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10354082/. [CrossRef]

- Stacey SK, McEleney M. Topical Corticosteroids: Choice and Application. Am Fam Physician. 2021 Mar 15 [cited 2024, 103, 337–343. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2021/0315/p337.html.

- Tyros G, Kalapothakou K, Christofidou E, Kanelleas A, Stavropoulos PG. Successful Treatment of Localized Pemphigus Foliaceus with Topical Pimecrolimus. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013, PMCID: PMC3789317, 1–3. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3789317/. [CrossRef]

| Date | 2016 | July 2021 | December 2021 | October 2022 | April 2023 |

October 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANA antibodies titer and type of fluorescence | 1:640 speckled-granular and mitochondrial | 1:320 nuclear 1:320 granular | 1:320 nuclear 1:160 granular, 1:80 cytoplasmic | |||

| ANA specificity antibodies | negative | Scl 70 (+) | ||||

| anti-DSG1 antibodies titer | 1:40 | 1:80 | negative | 1:40 | 1:80 | |

| anti-DSG3 antibodies titer | 1:20 | 1:20 | negative | 1:20 | 1:40 | |

| Antibodies on monkey esophagus substrate | 1:20 | 1:10 | 1:40 |

1:40 | Negative | |

| DIF | deposits of IgG (++) and IgA (++) in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis | granular deposits of IgG (+) in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis, granular C3 (+) deposits along the dermoepidermal junction | ||||

| LBT | Negative | |||||

|

Histopathology |

skin section covered with acantholytic epidermis with preserved basal and spinous layers (bottom of the blister) with lymphocyte infiltration in the stroma—the image may correspond to the diagnosis of pemphigus |

| Paper | Demographic | Location of lesions | Appearance of skin lesions | Histopathology examination | DIF—ICS | DIF-DEJ | ANA | DSG-1 | DSG-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hobbs, 2021 [8] | 37,f | scalp and face |

thick, scaly, crusty erythematous plaques | epidermis: acantholysis dermis: perivascular and interstitial infiltrate | IgG | granular IgG and C3, fibrin (focal) deposition | negative | NA | NA |

| Hobbs, 2021 [8] | 44,f | face and oral mucosa |

heavy scale, underlying erythema without blisters or erosions | epidermis: acantholysis dermis: inflammatory infiltrate |

- | IgG, C3, fibrin around dermal vessels |

negative | positive | NA |

| Hobbs, 2021 [8] | 68,m | trunk and scalp |

classic raw erosive changes with some crusting |

epidermis: acantholysis, dermis: perivascular infiltrate | IgG, C3, fibrin |

C3 | NA |

NA |

NA |

| Hobbs, 2021 [8] | 53,f | face |

scaly, dusky plaques with erythematous raised borders | epidermis: keratinocyte necrosis and vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer along with apoptotic bodies, dermis: perivascular infiltrate |

IgG, C3 |

granular C3, focal IgM, granular IgA |

positive | positive | NA |

| Hobbs, 2021 [8] | 17, m | face, extremities, trunk, and oral mucosa | crusted, vegetative plaques, intact tense small bullae and vesicles |

epidermis: acantholysis |

IgG, C3 |

granular C3 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Garcia-Souto, 2020 [18] | 53, f | face |

crusted erosions over the face |

intraepidermal blister with acantholysis of the granular layer |

IgG, C3 |

- |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Lo Schiavo, 2014 [19] | 70, m | face and trunk |

erythematous scaly plaques which involved the cheeks in a butterfly distribution symmetrically and crusted lesions localized on the upper part of the chest | intraepithelial superficial blister |

IgG, C3 |

IgG, C3 |

positive | positive | NA |

| Neha Chandan, 2018 [16] | 24, f | trunk, extremities, and face |

erythematous, eroded, boggy scalp, crusting, and scale adherent to the residual hair, with yellow to brown debris |

suprabasal and intraepidermal acantholysis with no interface or basal vacuolar changes |

IgG |

IgG, C3 |

negative | positive | positive |

| Baroni, 2009 [20] | 14, m | scalp |

flaccid vesiculobullae, erosions, and crusted lesions over the upper part of the chest and face, and diffuse scaly plaques on the scalp |

intraepidermal superficial blistering containing a few acantholytic cells |

IgG, C3 |

- | NA | positive | negative |

| Chen, 2023 [21] | 39, m | face, trunk, and extremities |

extensive blistering and ulceration on the face, trunk, abdomen, and extremities |

intraepithelial cleavage with detached keratinocytes primarily localized just under the stratum corneum |

IgG, C3 |

- | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen, 2023 [21] | 59, f | face, trunk, and extremities |

widespread erosions affecting the face, trunk, abdomen, and limbs |

subcorneal split directly below the stratum corneum |

IgG, C3 |

- | NA | NA | NA |

| Bilgic, 2018 [22] | 54, m | face, scalp |

well-demarcated, erythematous -squamous plaques, some with atrophic center or with cicatricial alopecia, on the scalp, nose, malar area and lips, bullae, and erosions with scale crusts on the trunk |

compatible with DLE and PF | IgG |

- | negative | positive | negative |

| Sawamura, 2016 [23] | 65, f | face, trunk, and extremities |

scattered erosive erythema with scaling and crusting throughout the body including the face |

intraepidermal blisters containing neutrophils and acantholytic keratinocytes |

IgG |

IgG |

NA |

positive | negative |

| Gupta, 2004 [24] | 7,m | extremities, face, scalp |

generalized scaling and redness associated with edema of the upper and lower extremities, flaccid blisters on the scalp, face, and both lower extremities |

compatible with pemphigus erythematosus |

IgG, C3 |

IgG, C3 |

negative | positive | negative |

| Pritchett, 2015 [25] | 40, f | face and trunk |

pruritic, pink scaling plaques on her face and neck, lesions subsequently involved chest, abdomen, and back, and flared with sun exposure |

epidermal acanthosis, spongiosis, and acantholytic keratinocytes lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate was seen in the dermis, with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils, foci of eosinophilic spongiosis in the epidermis | IgG, C3 |

IgG, C3 |

positive | NA | NA |

| Diab, 2008 [26] | 18, f | face, trunk, extremities |

keratotic hyperpigmented papules and plaques on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities |

acantholysis within the granular cell layer with concomitant interface dermatitis |

IgG, C3 |

IgM |

NA | positive | NA |

| Dyah, 2012 [27] | 80, f | face, trunk, extremities |

generalized progressive erythematous skin lesions with pustules and flaccid blisters | subcorneal blisters |

IgG, C3 |

- |

negative | positive | negative |

| Dyah, 2012 [27] | 76, f | face, scalp, trunk, extremities | itching plaques all over body and scalp except her legs |

ulcerative and erosive inflammation and secondary impetigo with beginning reepithelialization |

IgG, C3 |

IgG, C3, IgM |

Negative | positive | negative |

| Dyah, 2012 [27] | 68, m | scalp, extremities, trunk | red scaly skin lesions starting on the face, chest, and back, blisters on the whole body, including the scalp and extremities | remainder of a blister in the corneal layer and subepidermal neutrophilic infiltrates surrounding the blood vessels | IgG, IgA, C3 |

IgG, IgA, and C3 |

negative | positive | negative |

| Makino, 2014 [28] | 62,f | face, trunk, extremities | pruritic and slightly erythematous lesions with erosions on the nose, chest, and extremities |

detachment of the stratum corneum, infiltration of lymphocytes |

IgG |

IgM, C3 |

positive | positive | negative |

| de Vries, 2023 [29] | 51,m | face, scalp, and trunk |

pruritic scaly plaques on the face, scalp, and trunk |

acantholysis and granular layer separation |

NA |

NA |

positive | positive | negative |

| Shankar, 2004 [30] | 59, f | face, trunk, scalp, extremities |

pruritic rash on the upper chest and upper back, face, scalp and thighs |

acantholysis of the superficial epidermis with the formation of a subcorneal bulla and a very mild patchy interface dermatitis |

IgG, C3 |

IgM, C3 |

positive | NA | NA |

| Chavan, 2013 [31] | 32, f | face, scalp, trunk, extremities, oral mucosa |

erythematous papules over cheeks, ears, scalp, upper back, “V” of the chest and extensors of forearms and dorsal of hands, crusted scaly, plaques with surrounding erythema, erosions over upper gingiva | hyperkeratosis, subcorneal acantholysis, basal cell vacuolation, dermo-epidermal separation and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate |

IgG |

IgM, IgG |

positive | NA | NA |

| Paper | Demographic | Location of lesions | Appearance of skin lesions | Histopathology examination | DIF—ICS | DIF-DEJ | ANA | DSG-1 | DSG-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidalgo, 2001 [32] | 46, m | chest, extremities | pruritic eruption of symmetric lesions of 0.5–1 cm in diameter, consisting of vesicles on the chest, back, shoulders and legs |

intraepidermal detachment forming blisters and fissures in a suprabasal portion of the epidermis, with acantholysis, next to spongiform vesicles filled with polymorphs and several eosinophils |

IgG, C3 |

- | positive | NA | NA |

| Thongprasom, 2013 [33] | 36, f | oral mucosa, face |

desquamative gingivitis, erythematous facial rash with acne-like papules |

acantholysis of the epithelial cells, which exhibited intraepithelial separation, particularly in the lower spinous cell layer and perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes in the lamina propria |

IgG |

- | positive | NA | NA |

| Nanda, 2004 [34] | 45, f | oral mucosa |

ulcers on the buccal mucosa and soft palate with inflammation of the gums and soft pharynx |

intraepithelial blister with acantholytic cells |

IgG, C3 |

- | positive | negative | positive |

| Calebotta, 2004 [35] | 35, f | extremities, face, and oral mucosa |

generalized multiple erosions with zero-hematic crusts on the trunk and both legs, flaccid bullae with serous content located on the thigh, multiple erosions on oral mucosa |

separation in a plane above the basal layer of the epidermis |

IgG |

IgM, C3 |

positive | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).