Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Material

2.2. Immunofluorescence Studies

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

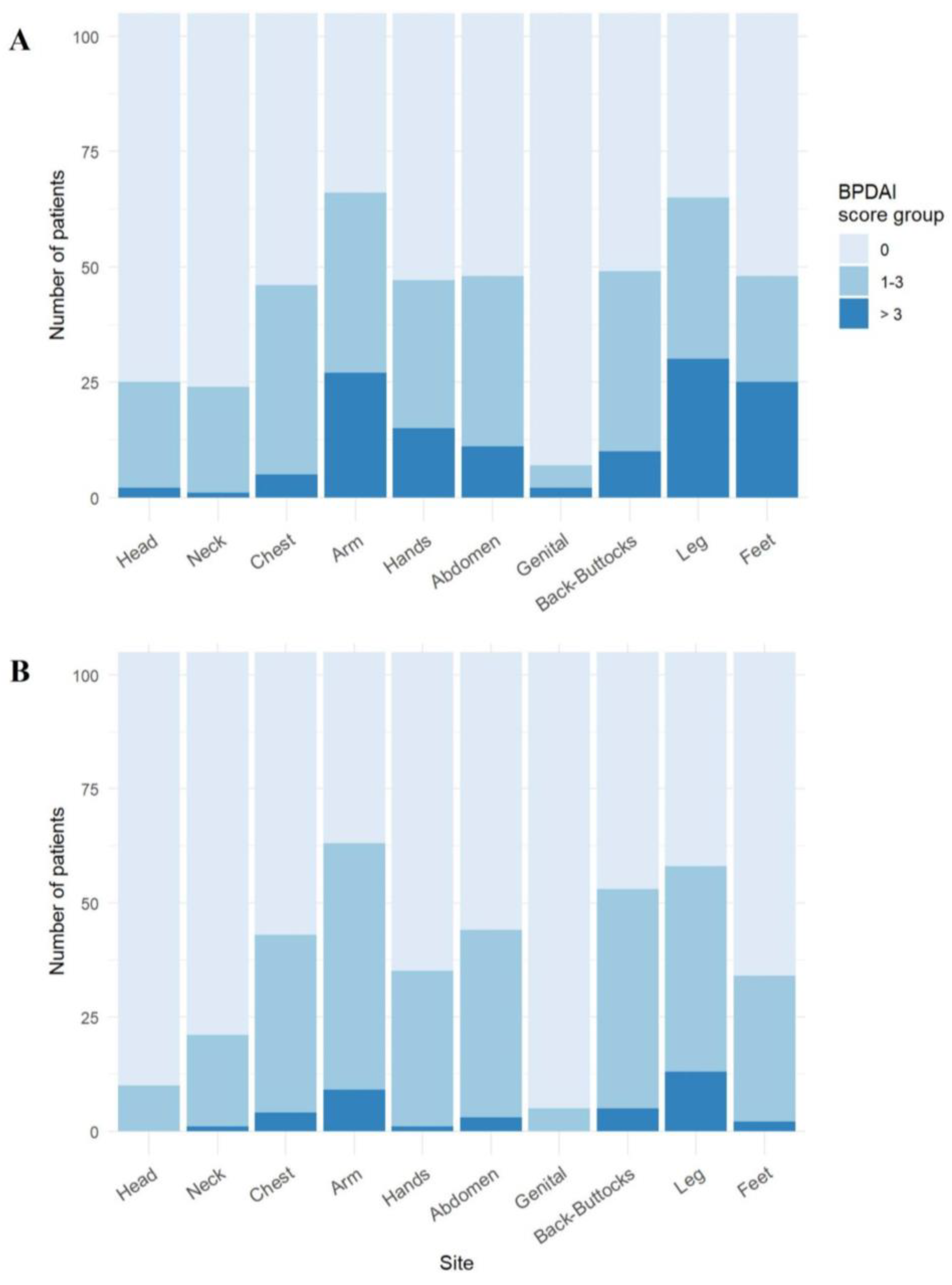

3.1. Arms and Legs Are the Most Common Sites for Blisters/Erosions and Erythematous/Urticarial Lesions in BP

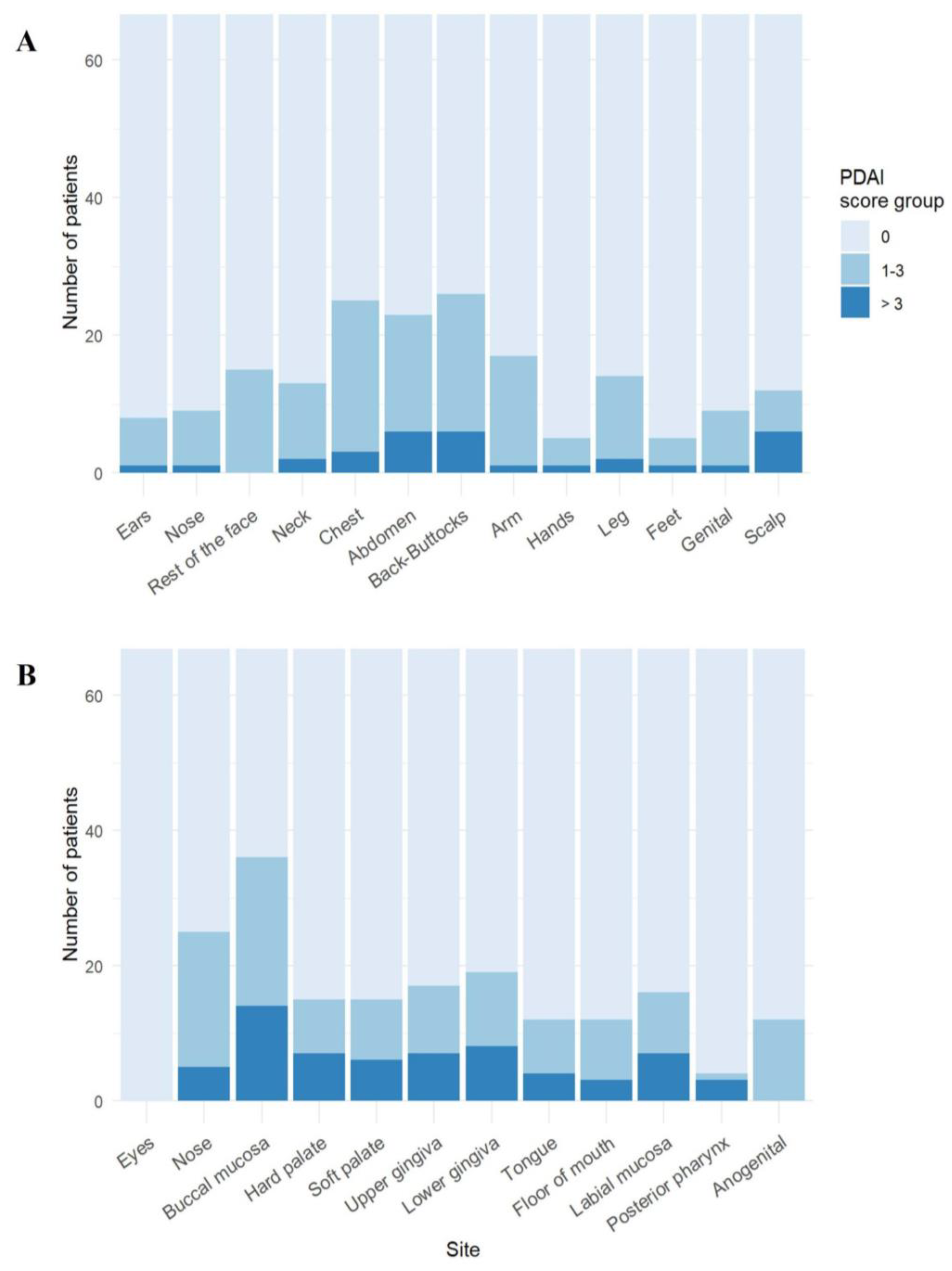

3.2. Trunk and Buccal Mucosa Are Predilection Sites in PV

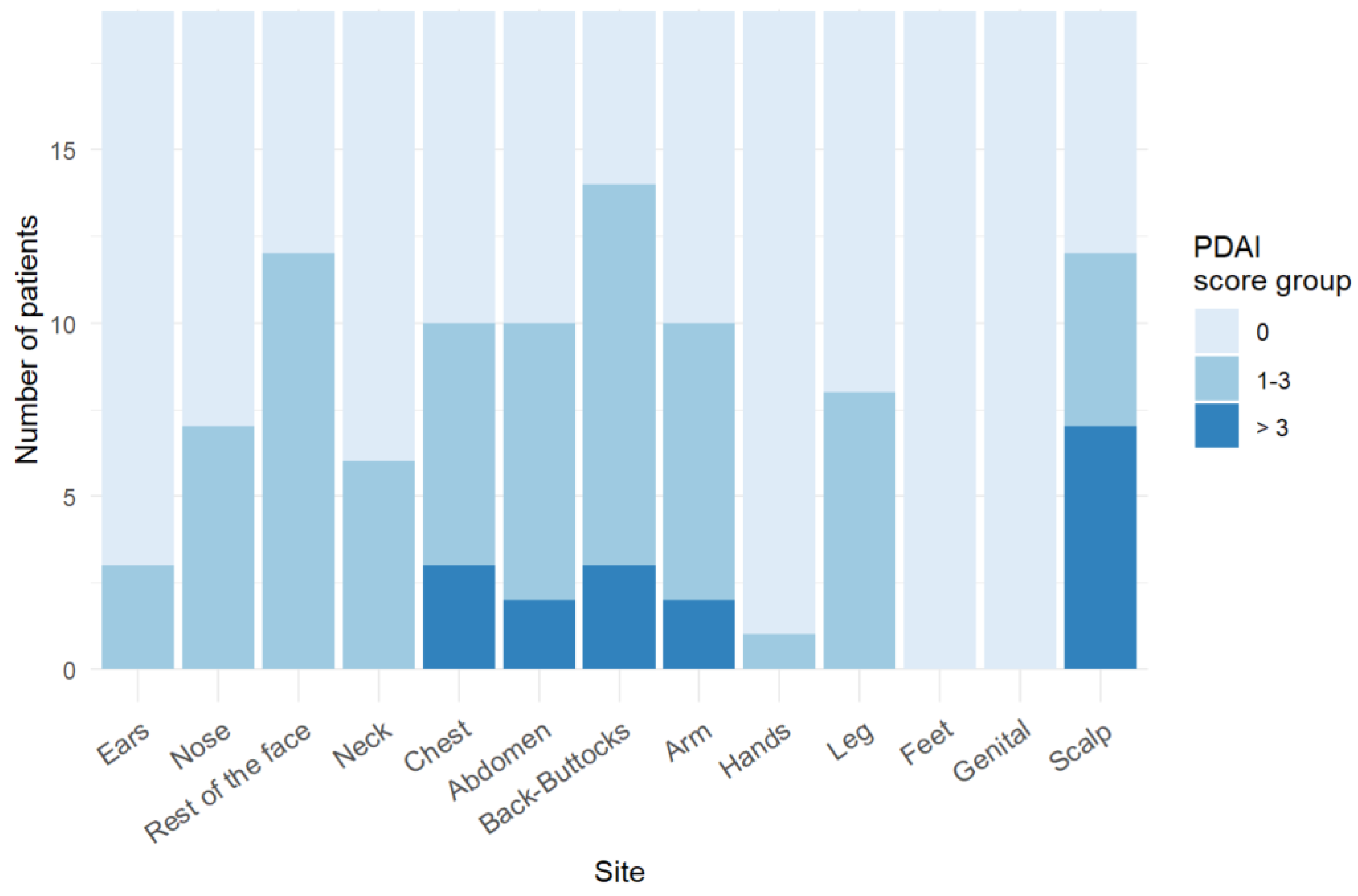

3.3. Trunk and Face Are Predilection Sites for Skin Blistering in PF

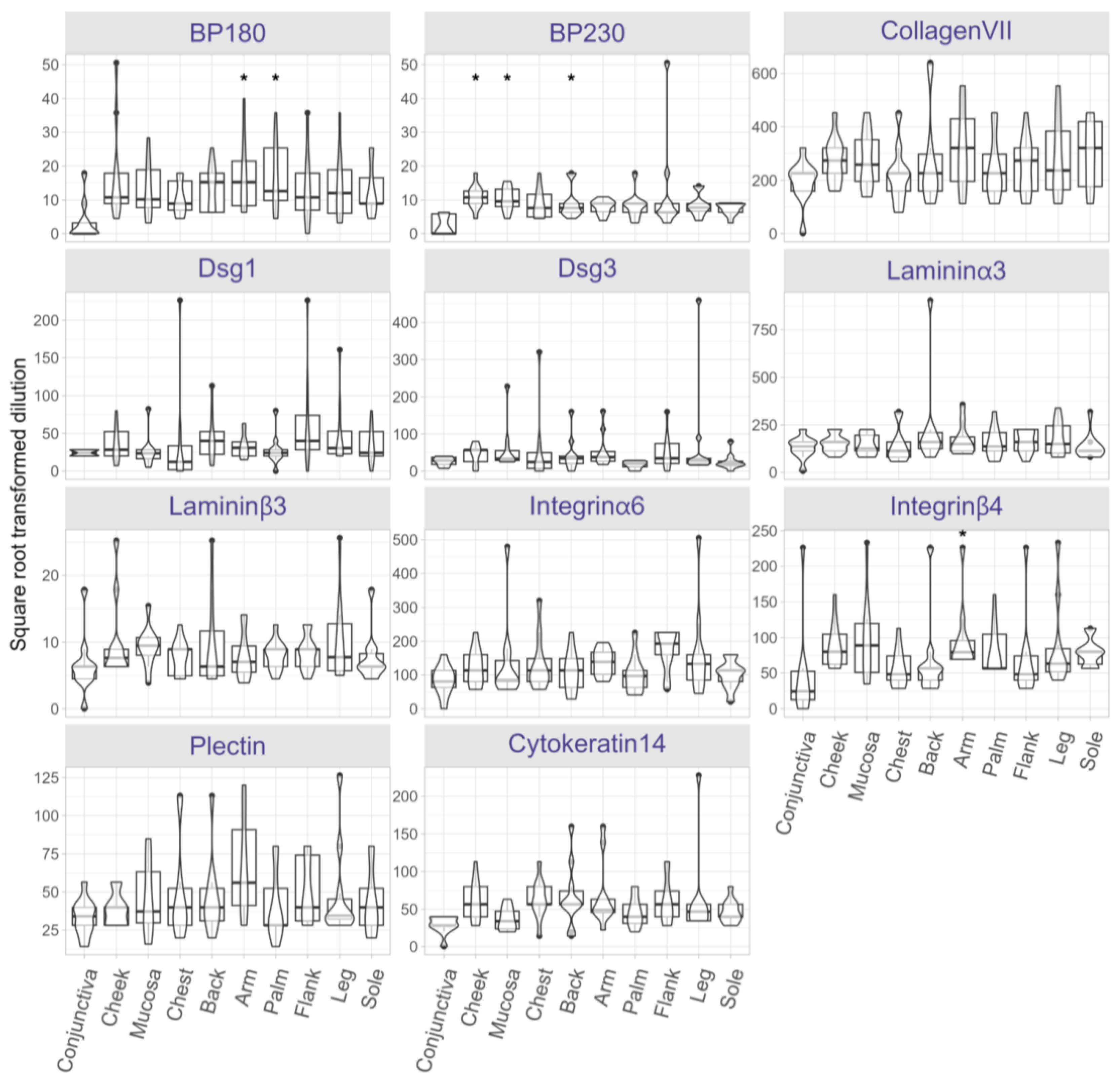

3.4. AIBD Antigen Expression Shows Slight Variations in Different Skin and Mucosal Regions

3.5. Expression Levels of AIBD Antigens Do Not Correlate with Clinical Scores

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Zeng, F.A.P. and D.F. Murrell, State-of-the-art review of human autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBD). Vet Dermatol, 2021. 32(6): p. 524-e145.

- Emtenani, S., et al., Mouse models of pemphigus: valuable tools to investigate pathomechanisms and novel therapeutic interventions. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1169947.

- Schmidt, E., M. Kasperkiewicz, and P. Joly, Pemphigus. Lancet, 2019. 394(10201): p. 882-894.

- Schmidt, E. and D. Zillikens, Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet, 2013. 381(9863): p. 320-32.

- van Beek, N., et al., Incidence of pemphigoid diseases in Northern Germany in 2016 - first data from the Schleswig-Holstein Registry of Autoimmune Bullous Diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2021. 35(5): p. 1197-1202.

- Holtsche, M.M., K. Boch, and E. Schmidt, Autoimmune bullous dermatoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2023. 21(4): p. 405-412.

- Du, G., et al., Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev, 2022. 21(4): p. 103036.

- Ioannides, D., et al., Regional variation in the expression of pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, and pemphigus vulgaris antigens in human skin. J Invest Dermatol, 1991. 96(2): p. 159-61.

- Borradori, L., et al., Updated S2 K guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2022. 36(10): p. 1689-1704.

- Schmidt, E., et al., S2k guideline for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2015. 13(7): p. 713-27.

- Murrell, D.F., et al., Definitions and outcome measures for bullous pemphigoid: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2012. 66(3): p. 479-85.

- Joly, P., et al., Updated S2K guidelines on the management of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus initiated by the european academy of dermatology and venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2020. 34(9): p. 1900-1913.

- Murrell, D.F., et al., Consensus statement on definitions of disease, end points, and therapeutic response for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2008. 58(6): p. 1043-6.

- Hothorn, T., F. Bretz, and P. Westfall, Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J, 2008. 50(3): p. 346-63.

- Goletz, S., et al., Laminin beta4 is a constituent of the cutaneous basement membrane zone and additional autoantigen of anti-p200 pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2024. 90(4): p. 790-797.

- Sprenger, A., et al., Consistency of the proteome in primary human keratinocytes with respect to gender, age, and skin localization. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2013. 12(9): p. 2509-21.

- Lintzeri, D.A., et al., Epidermal thickness in healthy humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2022. 36(8): p. 1191-1200.

- Xu, H., et al., Reference values for skin microanatomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of ex vivo studies. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2017. 77(6): p. 1133-1144 e4.

- Niebuhr, M., et al., Epidermal Damage Induces Th1 Polarization and Defines the Site of Inflammation in Murine Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita. J Invest Dermatol, 2020. 140(9): p. 1713-1722 e9.

- Pinkus, H., Examination of the epidermis by the strip method of removing horny layers. I. Observations on thickness of the horny layer, and on mitotic activity after stripping. J Invest Dermatol, 1951. 16(6): p. 383-6.

- Hundt, J.E., et al., Visualization of autoantibodies and neutrophils in vivo identifies novel checkpoints in autoantibody-induced tissue injury. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 4509.

- Carmona-Cruz, S., L. Orozco-Covarrubias, and M. Saez-de-Ocariz, The Human Skin Microbiome in Selected Cutaneous Diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022. 12: p. 834135.

- Belheouane, M., et al., Characterization of the skin microbiota in bullous pemphigoid patients and controls reveals novel microbial indicators of disease. J Adv Res, 2023. 44: p. 71-79.

- Tufano, M.A., et al., Detection of herpesvirus DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and skin lesions of patients with pemphigus by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol, 1999. 141(6): p. 1033-9.

- Fernandes, N.C., et al., Refractory pemphigus foliaceus associated with herpesvirus infection: case report. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 2017. 59: p. e41.

- Jang, H., et al., Bullous pemphigoid associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in a hepatitis B virus endemic area: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018. 97(15): p. e0377.

- Sanchez-Palacios, C. and L.S. Chan, Development of pemphigus herpetiformis in a patient with psoriasis receiving UV-light treatment. J Cutan Pathol, 2004. 31(4): p. 346-9.

- Kano, Y., et al., Pemphigus foliaceus induced by exposure to sunlight. Report of a case and analysis of photochallenge-induced lesions. Dermatology, 2000. 201(2): p. 132-8.

- Safadi, M.G., et al., Pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus localized to the nose: Report of 2 cases. JAAD Case Rep, 2021. 15: p. 129-132.

- George, P.M., Bullous pemphigoid possibly induced by psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, 1995. 11(5-6): p. 185-7.

- Wilczek, A. and M. Sticherling, Concomitant psoriasis and bullous pemphigoid: coincidence or pathogenic relationship? Int J Dermatol, 2006. 45(11): p. 1353-7.

- Massa, M.C., R.J. Freeark, and J.S. Kang, Localized bullous pemphigoid occurring in a surgical wound. Dermatol Nurs, 1996. 8(2): p. 101-3.

- Danescu, S., et al., Role of physical factors in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: Case report series and a comprehensive review of the published work. J Dermatol, 2016. 43(2): p. 134-40.

- Lo Schiavo, A., et al., Bullous pemphigoid initially localized around the surgical wound of an arthroprothesis for coxarthrosis. Int J Dermatol, 2014. 53(4): p. e289-90.

- Neri, I., et al., Bullous pemphigoid appearing both on thermal burn scars and split-thickness skin graft donor sites. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2013. 11(7): p. 675-6.

- Ghura, H.S., G.A. Johnston, and A. Milligan, Development of a bullous pemphigoid after split-skin grafting. Br J Plast Surg, 2001. 54(5): p. 447-9.

- Moro, F., et al., Bullous Pemphigoid: Trigger and Predisposing Factors. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(10).

- Konishi, N., et al., Bullous eruption associated with scabies: evidence for scabetic induction of true bullous pemphigoid. Acta Derm Venereol, 2000. 80(4): p. 281-3.

- Baroni, A., et al., Localized bullous pemphigoid occurring on surgical scars: an instance of immunocompromised district. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol, 2014. 80(3): p. 255.

- Jones, G.W. and S.A. Jones, Ectopic lymphoid follicles: inducible centres for generating antigen-specific immune responses within tissues. Immunology, 2016. 147(2): p. 141-51.

- Honda, T., G. Egawa, and K. Kabashima, Antigen presentation and adaptive immune responses in skin. Int Immunol, 2019. 31(7): p. 423-429.

- Kabashima, K., et al., The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019. 19(1): p. 19-30.

- Han, D., et al., Microenvironmental network of clonal CXCL13+CD4+ T cells and Tregs in pemphigus chronic blisters. J Clin Invest, 2023. 133(23).

- Xu, C., et al., Integrative single-cell analysis reveals distinct adaptive immune signatures in the cutaneous lesions of pemphigus. J Autoimmun, 2023. 142: p. 103128.

- Wang, S., et al., Plasma levels of D-dimer and fibrin degradation products correlate with bullous pemphigoid severity: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 17746.

- Olbrich, M., et al., Genetics and Omics Analysis of Autoimmune Skin Blistering Diseases. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 2327.

- Zhang, Y.Z. and Y.Y. Li, Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol, 2014. 20(1): p. 91-9.

- Ruano, J., et al., Molecular and Cellular Profiling of Scalp Psoriasis Reveals Differences and Similarities Compared to Skin Psoriasis. PLoS One, 2016. 11(2): p. e0148450.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).