Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Uncertainty and Sensor Fusion

3.2. Leader-Based Bat Algorithm (LBBA)

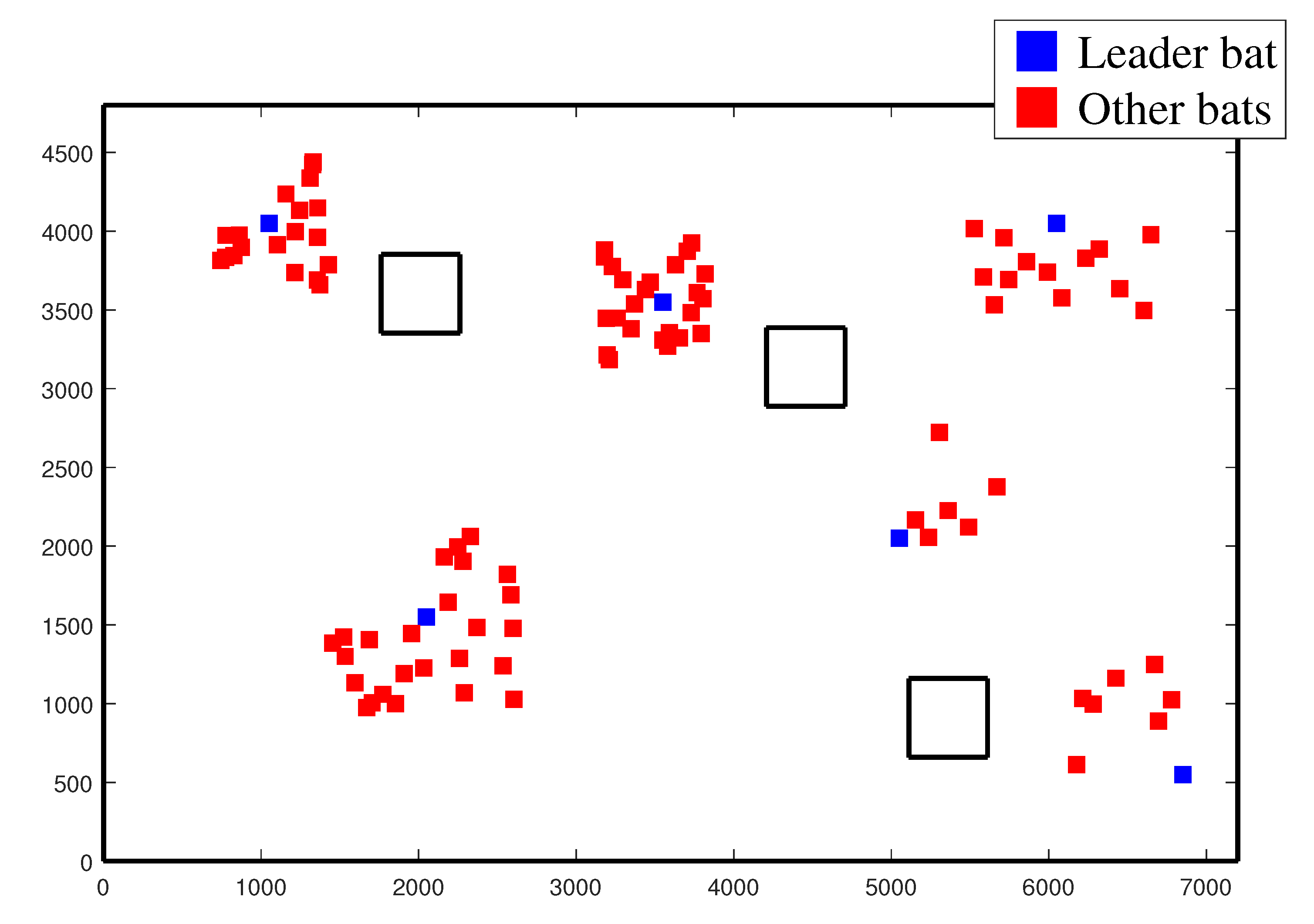

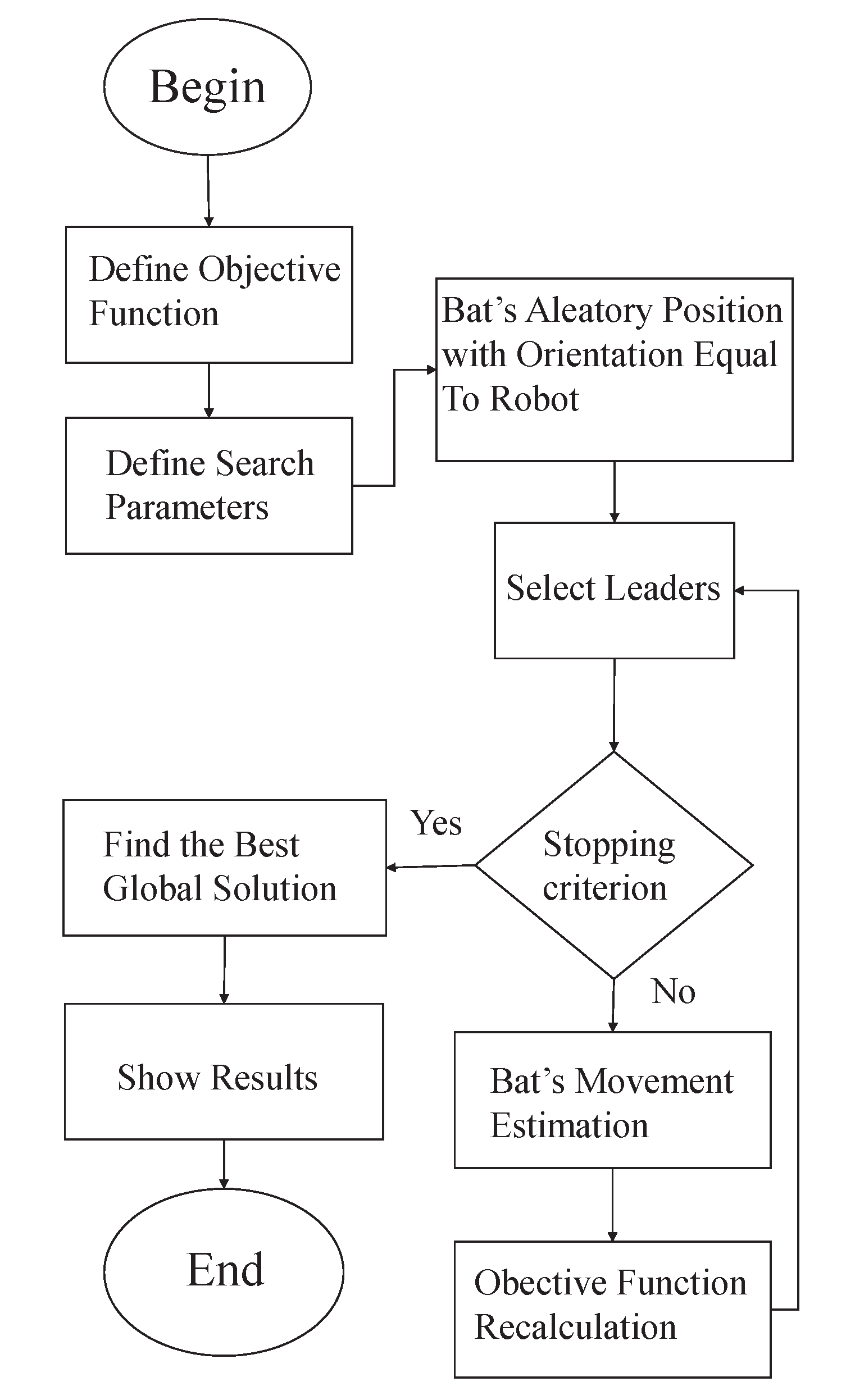

- Initialization: The algorithm starts with a population of bats, each one with a random initial position and velocity.

- Leader Selection: A subset of bats is designated leaders based on their fitness values. Leaders influence the movements of other bats, guiding the swarm towards promising areas of the search space.

-

Movement Update: Bats update their positions and velocities based on the current best solutions and the influence of the leaders. The updating equations areandwhere and are the velocity and position of bat i at time t, is the current best solution, is the frequency factor, and is a random vector drawn from a uniform distribution in.

- Evaluation: Each bat’s position is evaluated using a fitness function that measures the discrepancy between the estimated pose and the actual sensor measurements.

- Termination: The algorithm iterates until a stopping criterion is met, such as a maximum number of iterations or a convergence threshold.

3.3. The proposed LBBA Algorithm

- Reduction of Search Space: It limits the possible orientations of the robot, allowing for a more efficient and faster search.

- Improved Accuracy: The precise orientation from the compass helps better align the localization estimates with reality, increasing the algorithm’s accuracy.

- Reduction in Computational Complexity: Fewer particles are needed, reducing the computational load and allowing real-time use of the algorithm.

4. Results

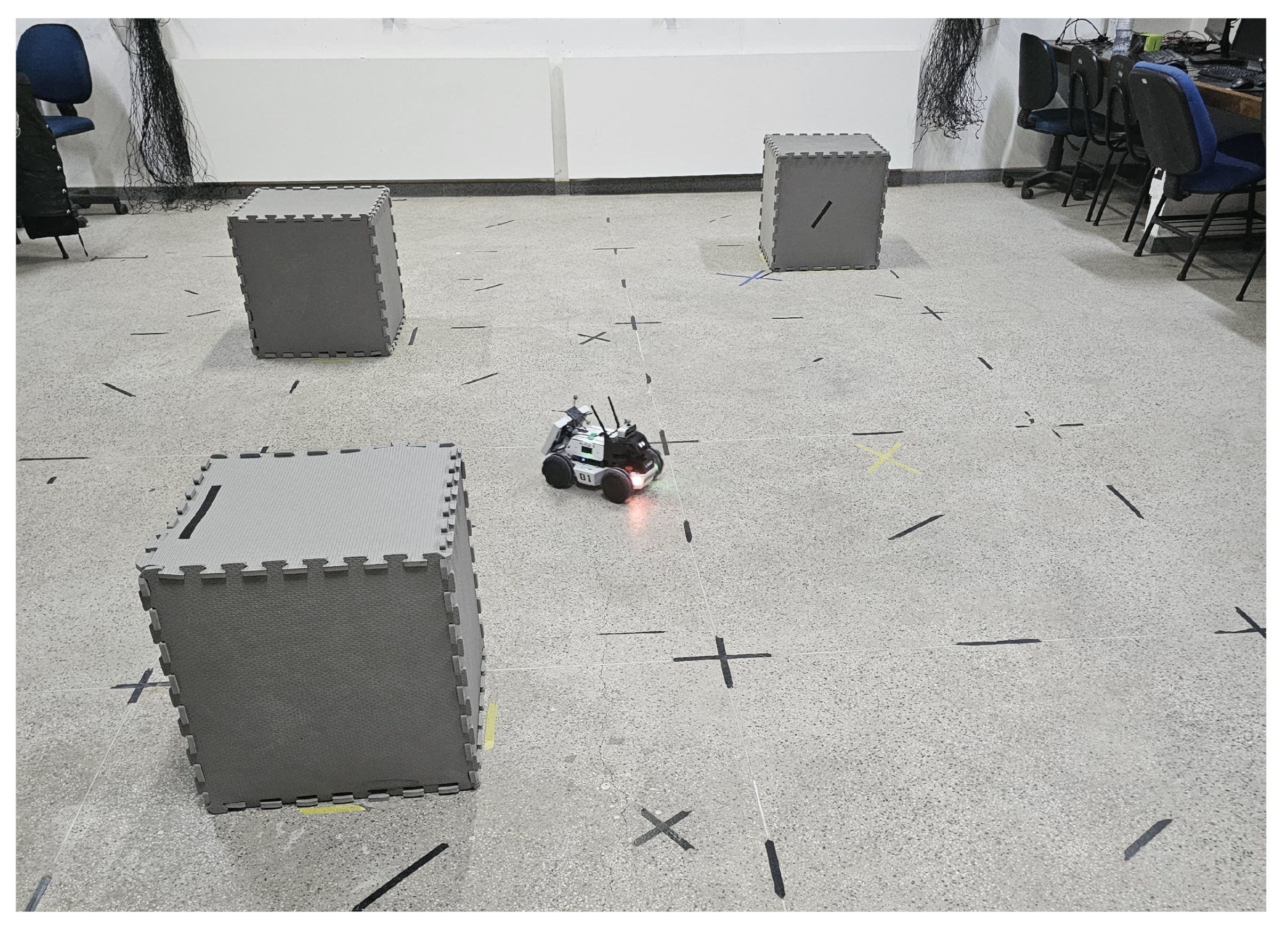

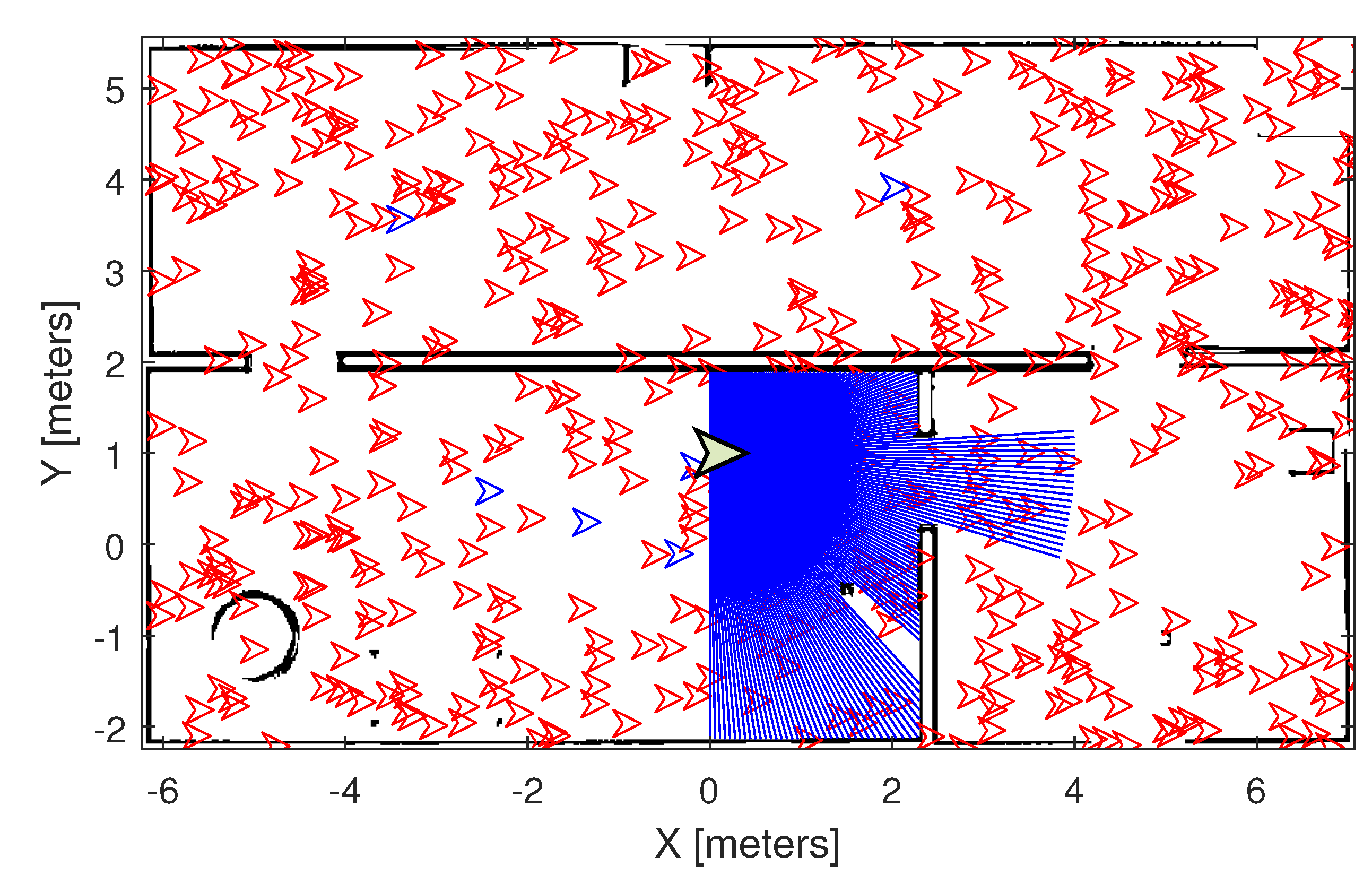

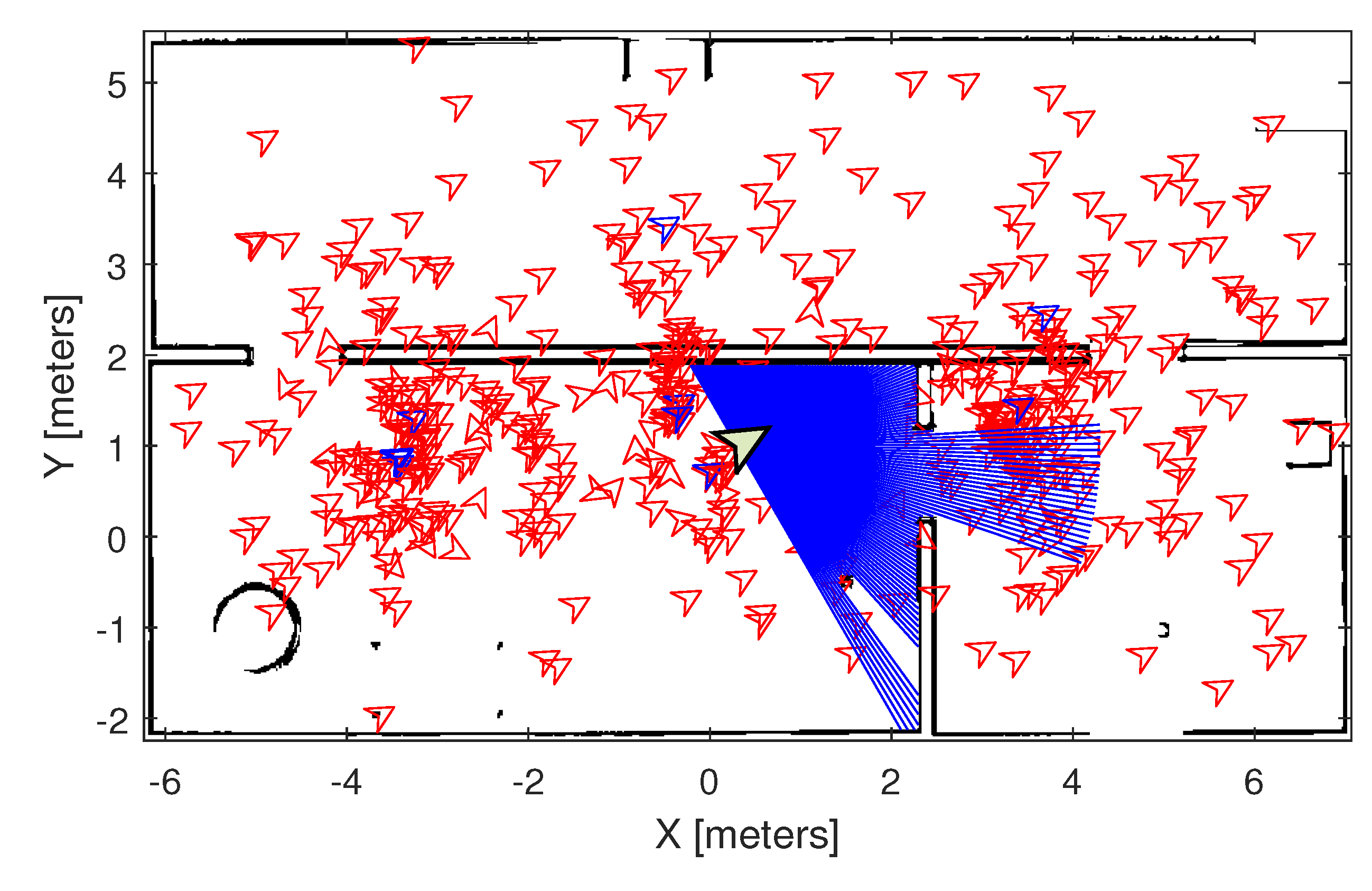

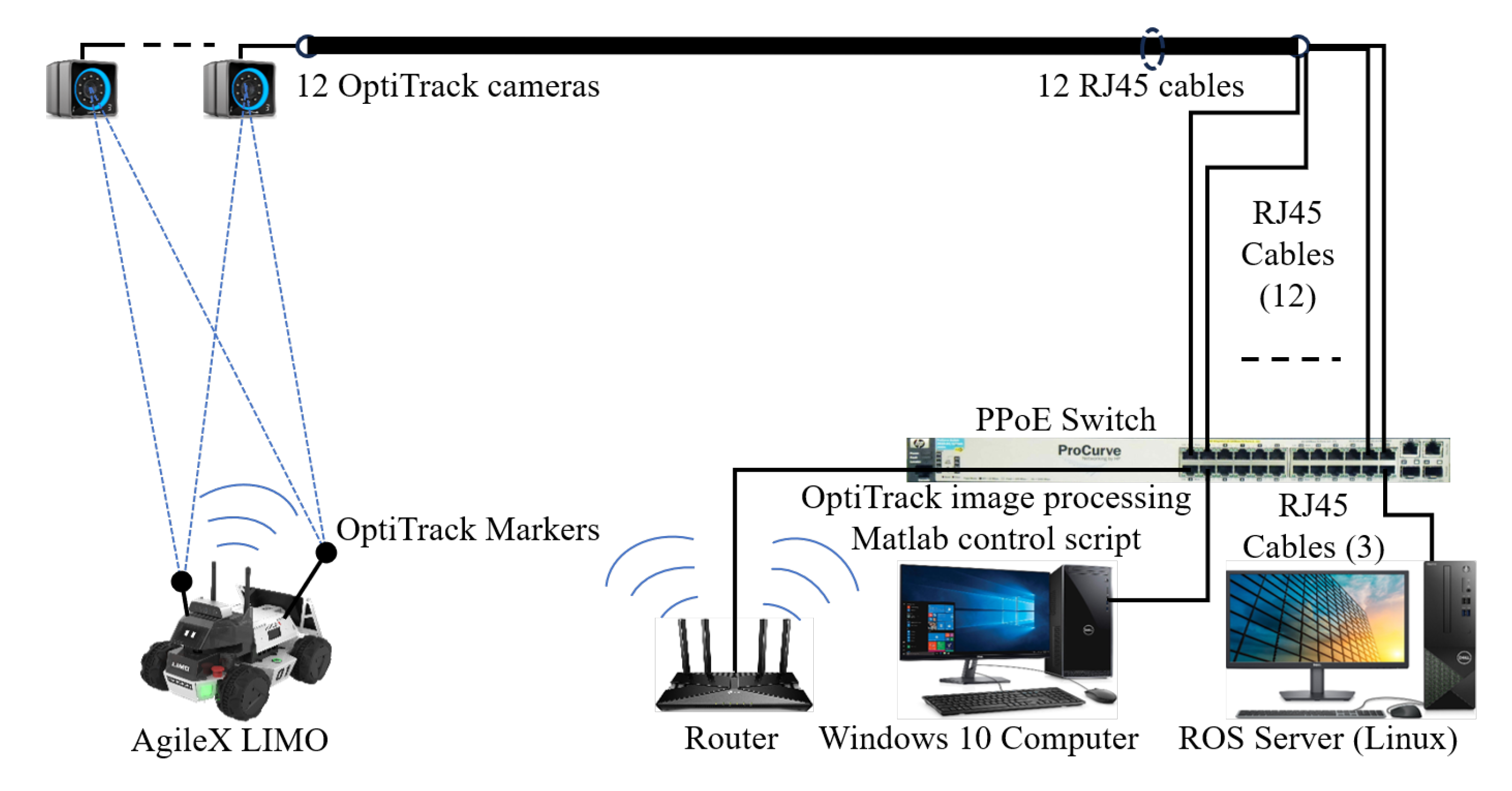

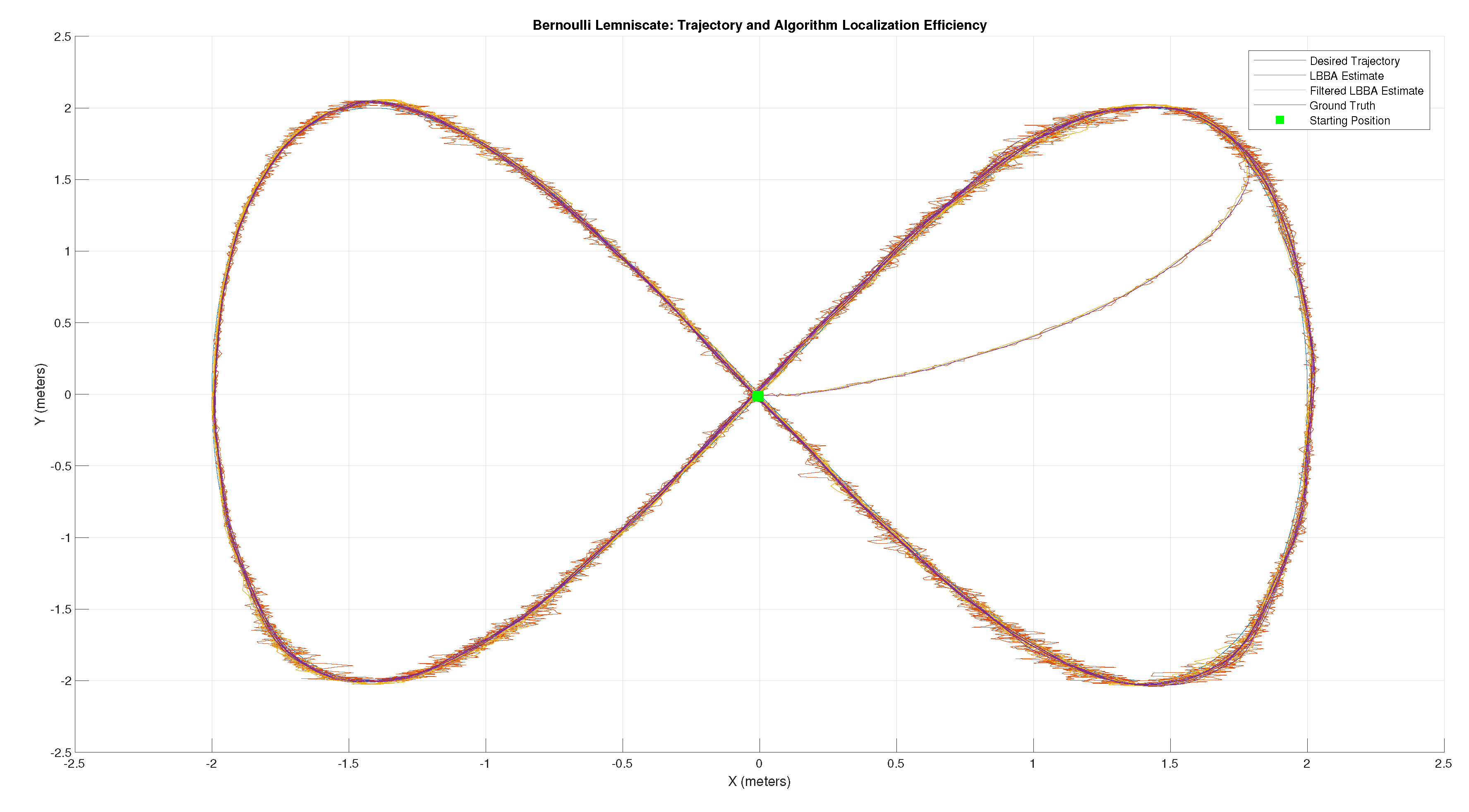

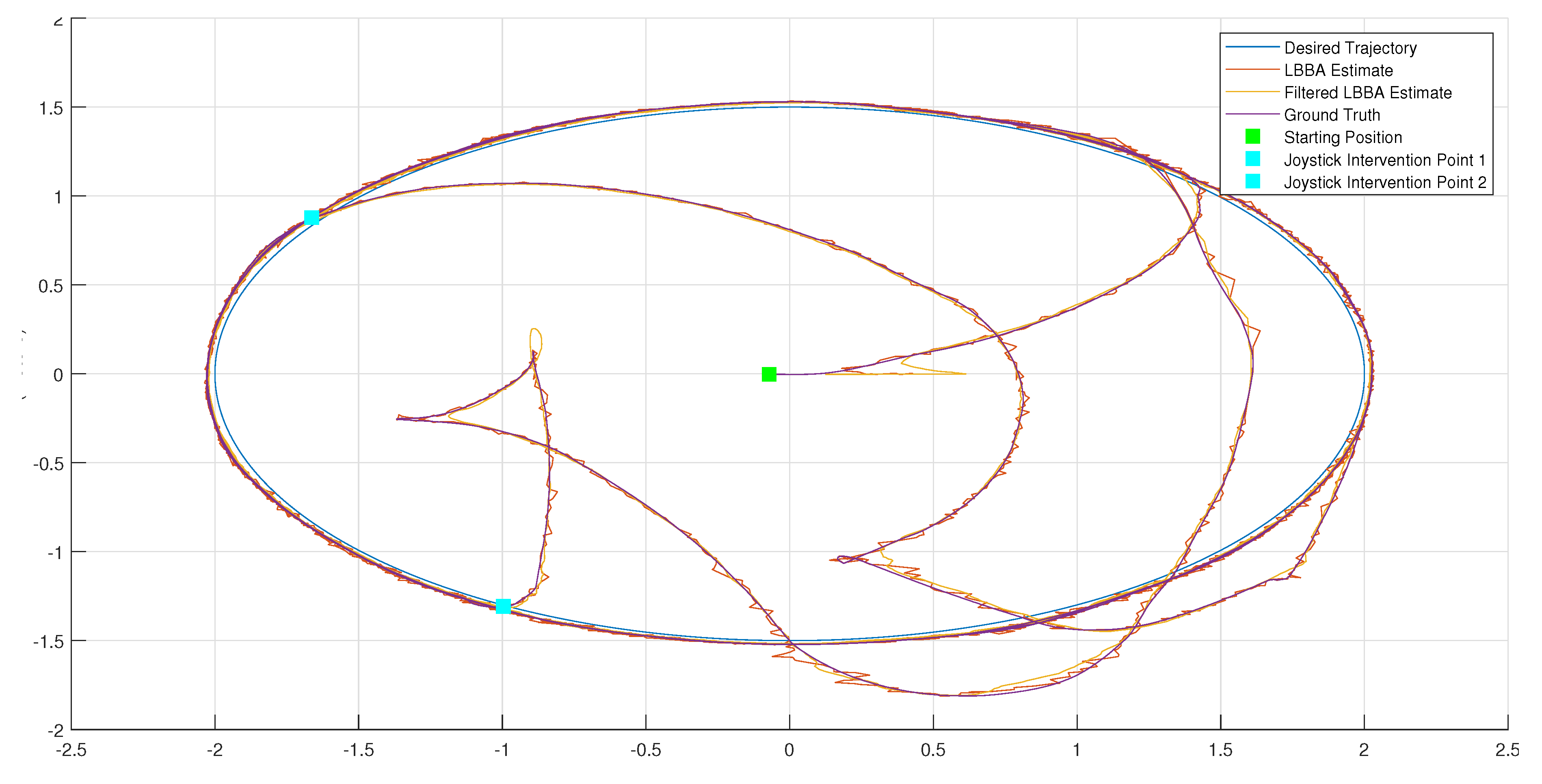

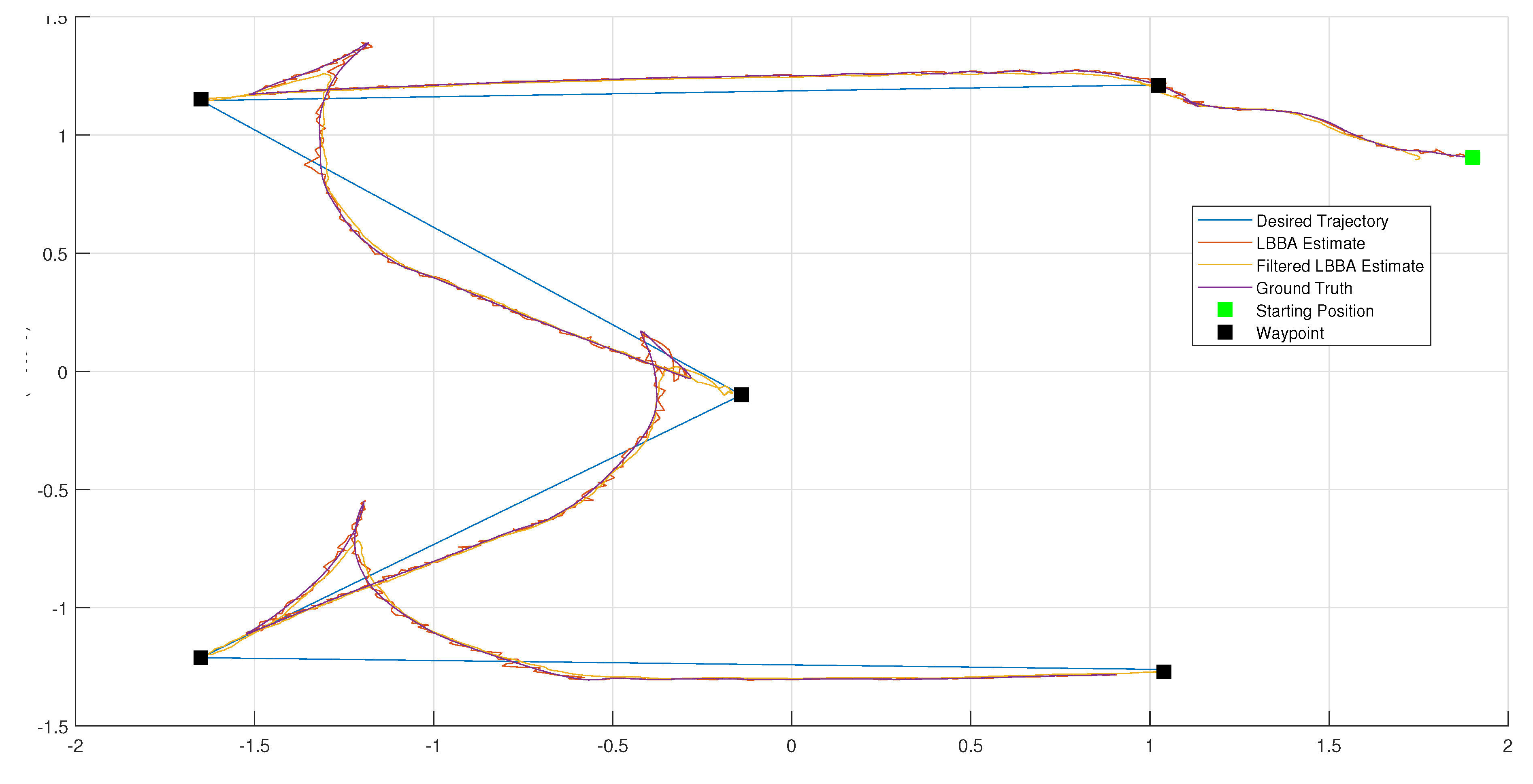

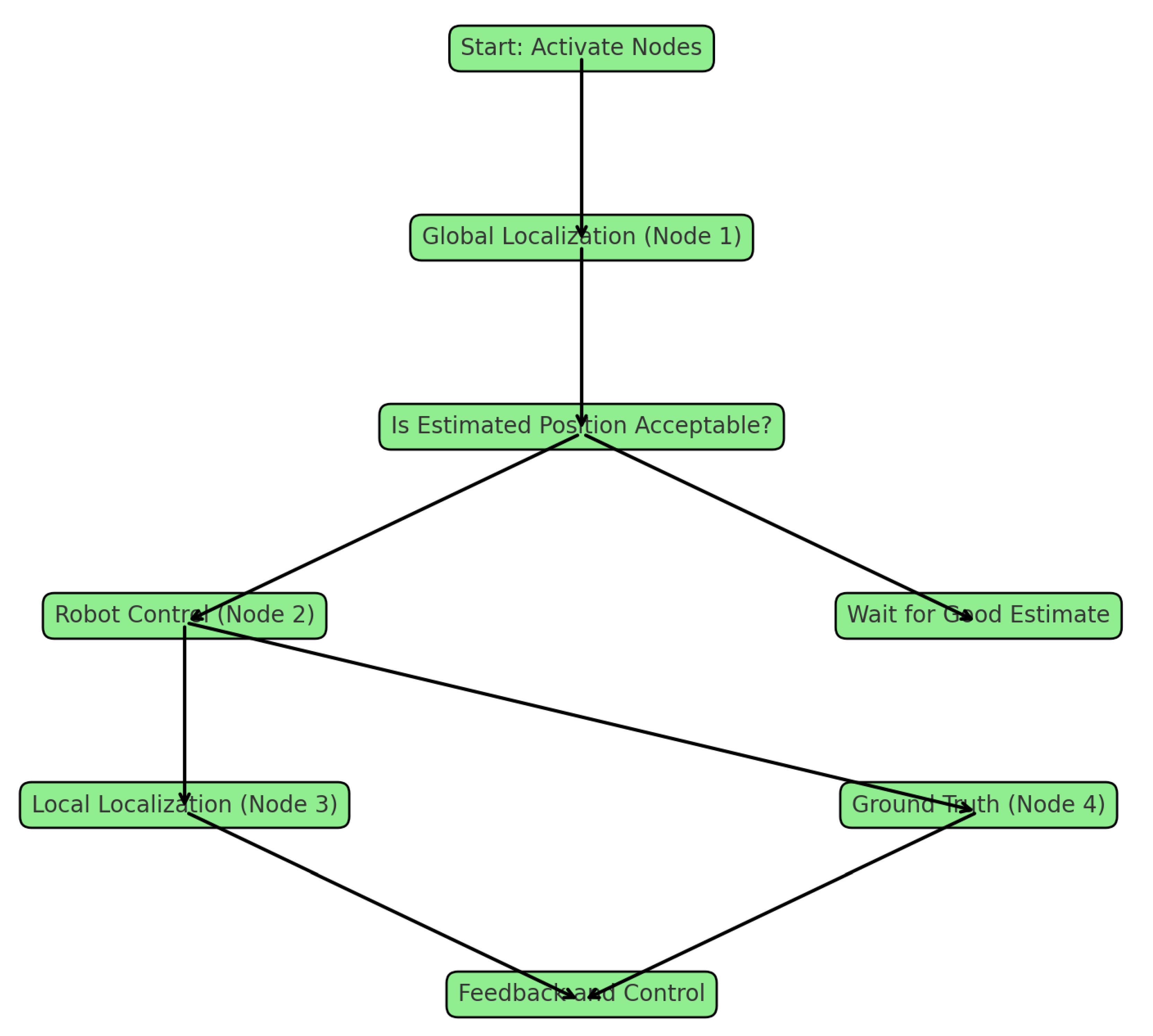

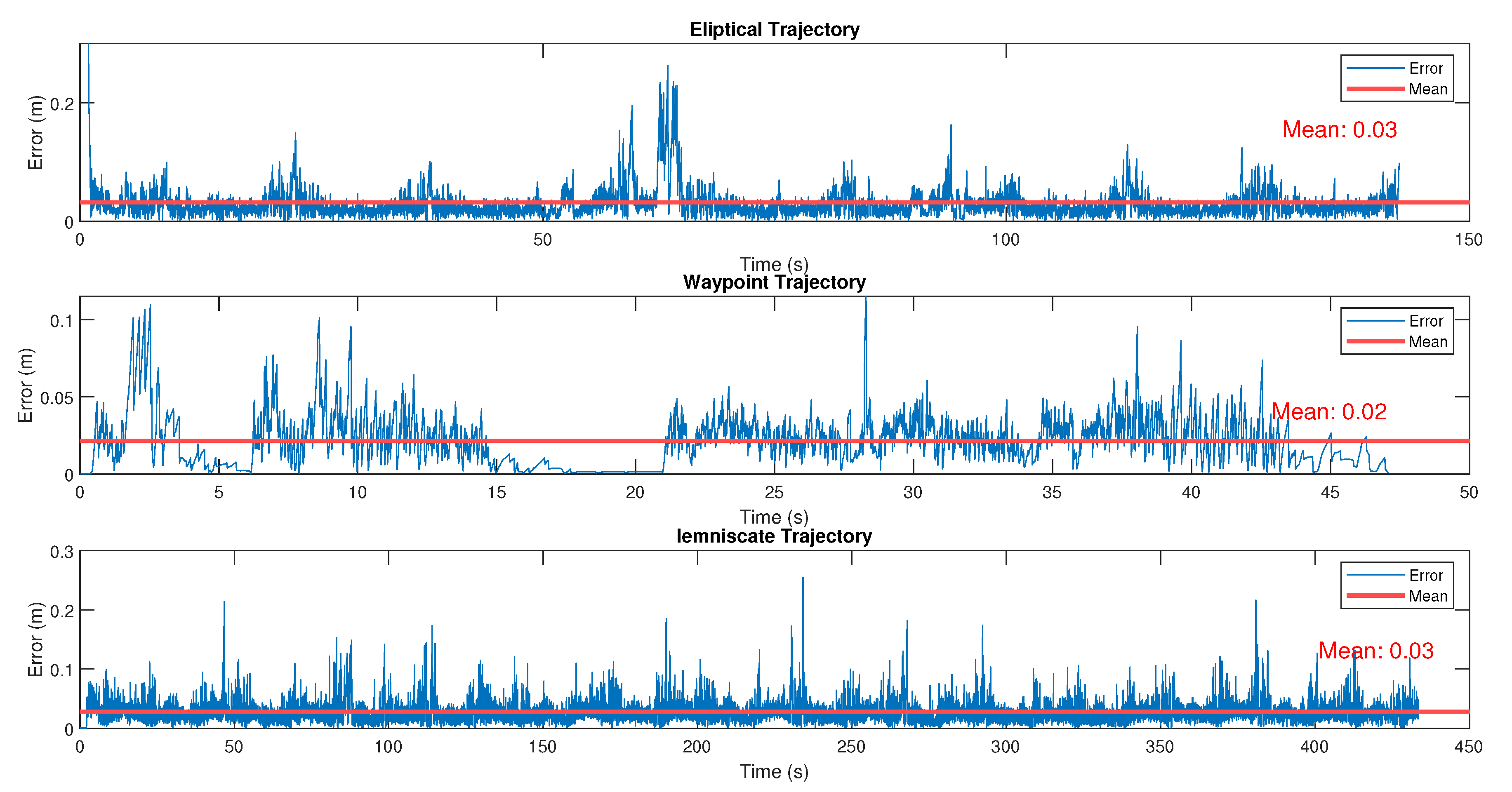

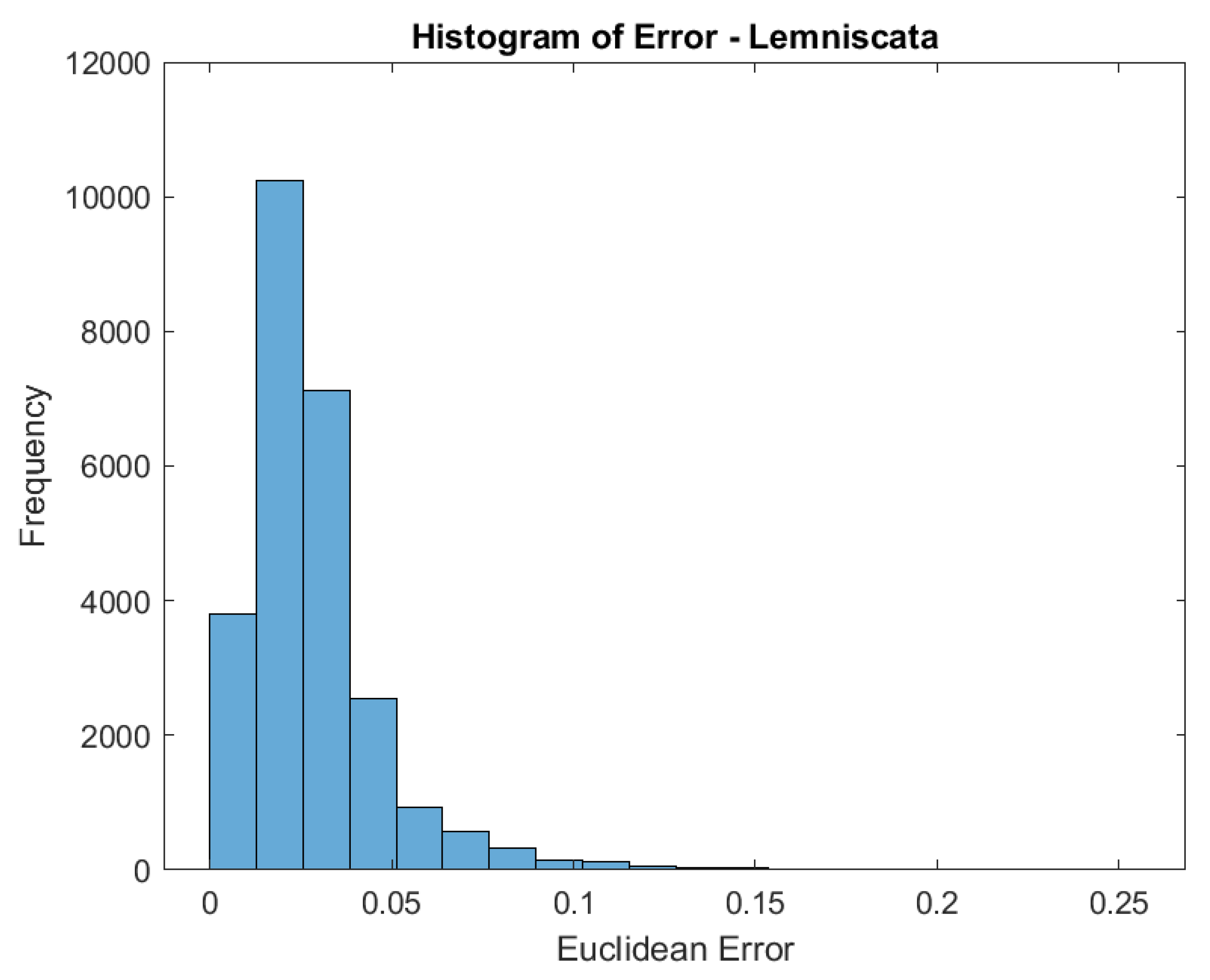

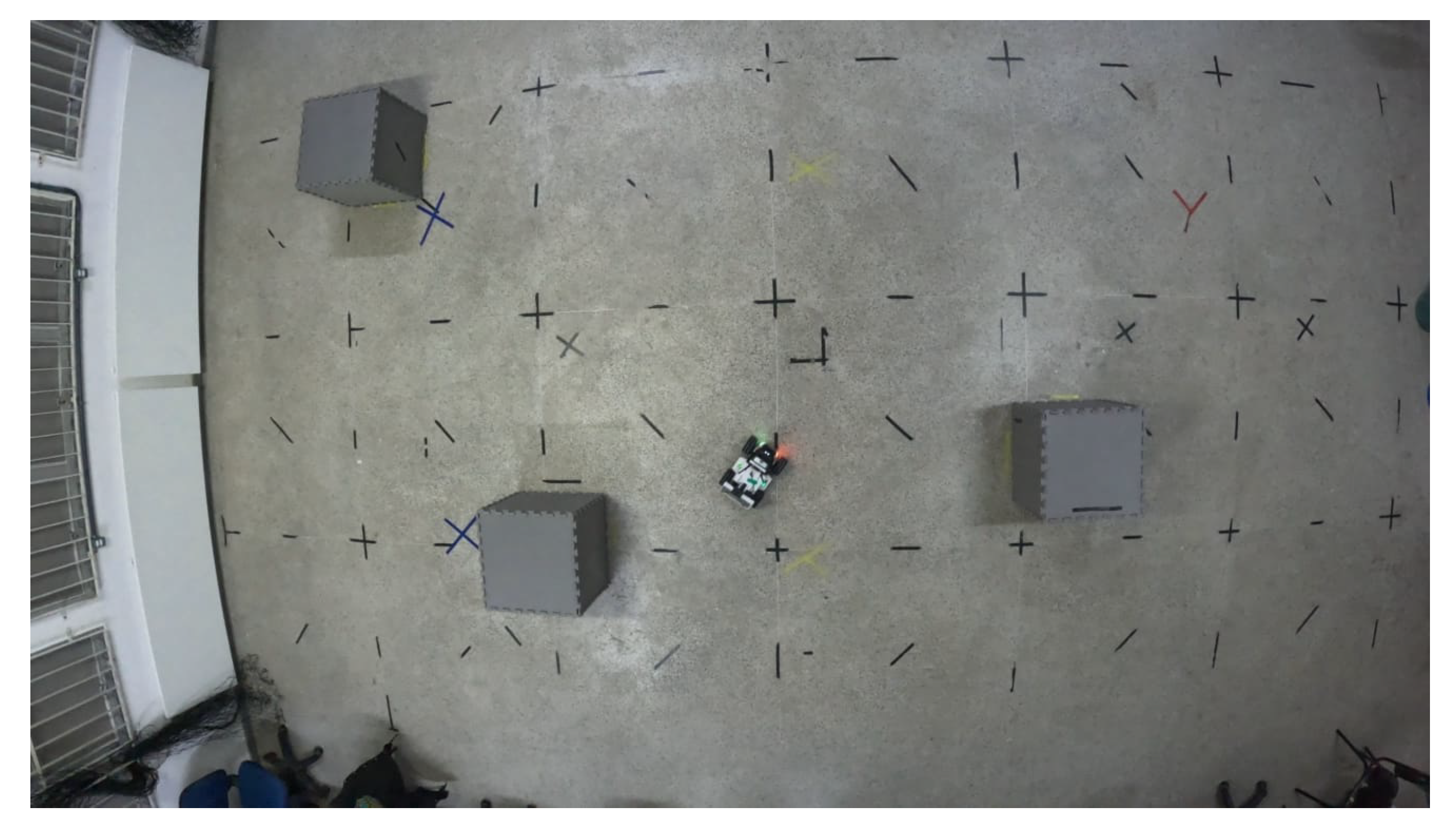

4.1. Performance Associated to the Real Tests

4.2. Performance Evaluation Through Simulated Tests

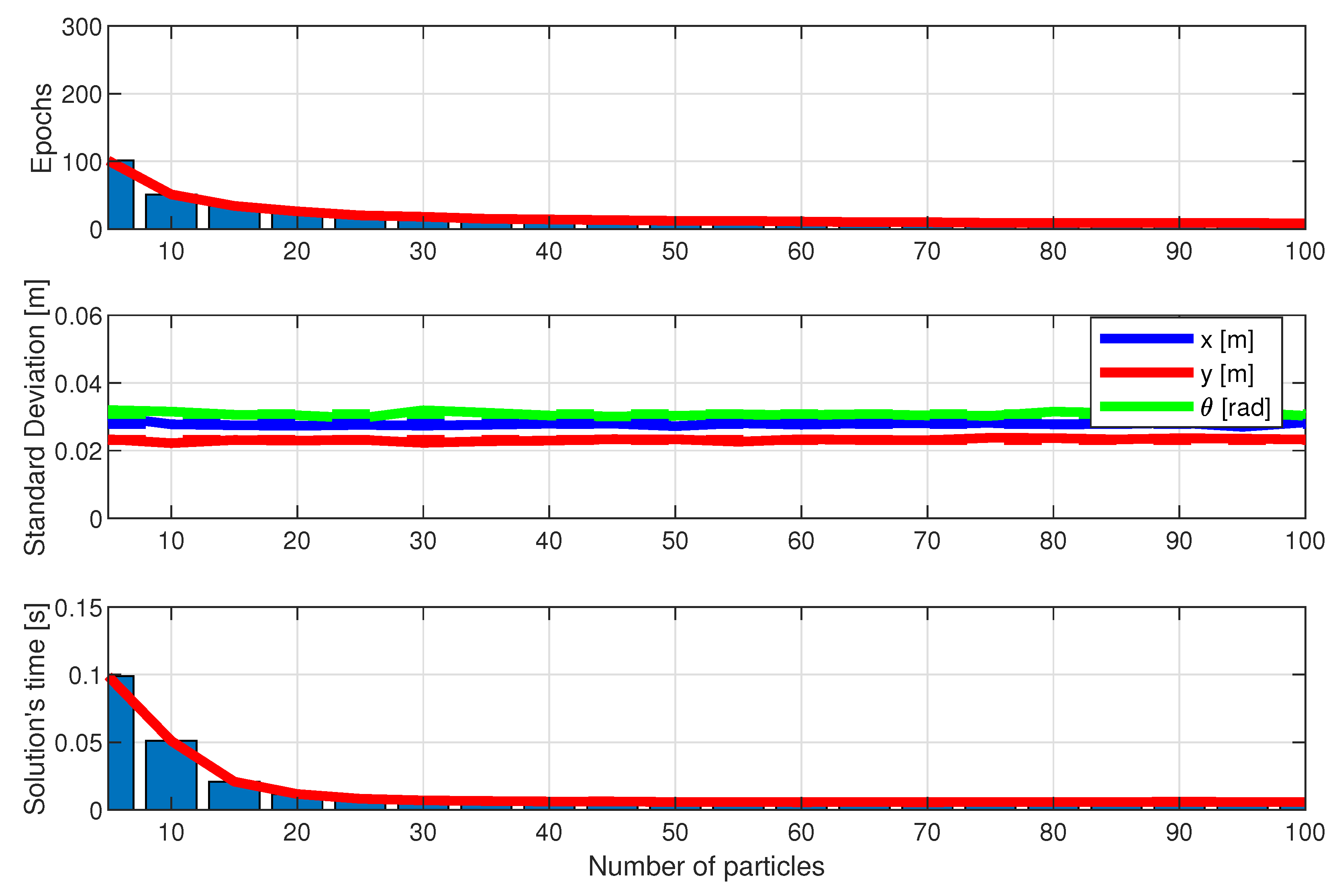

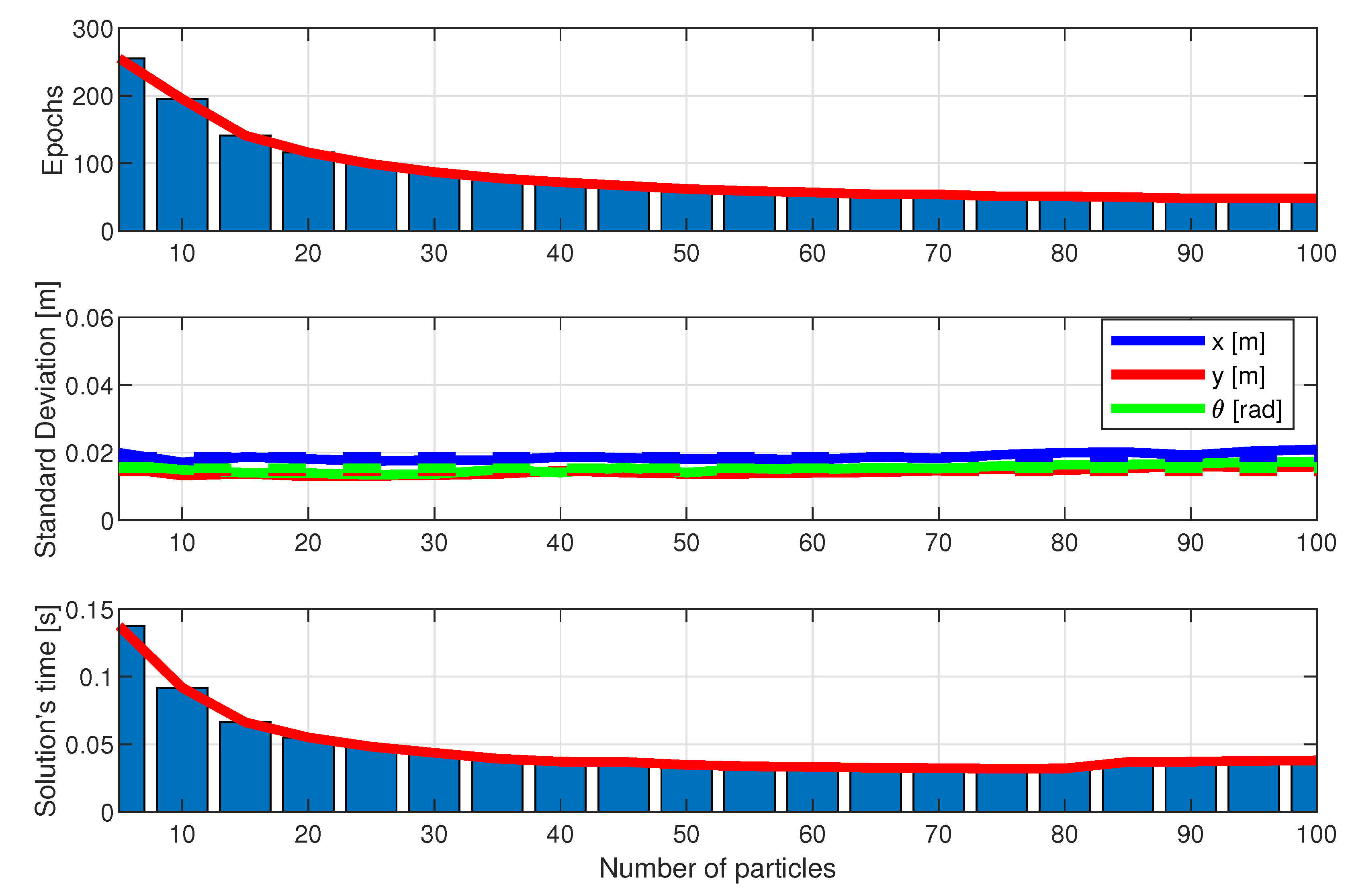

4.3. Algorithm Performance

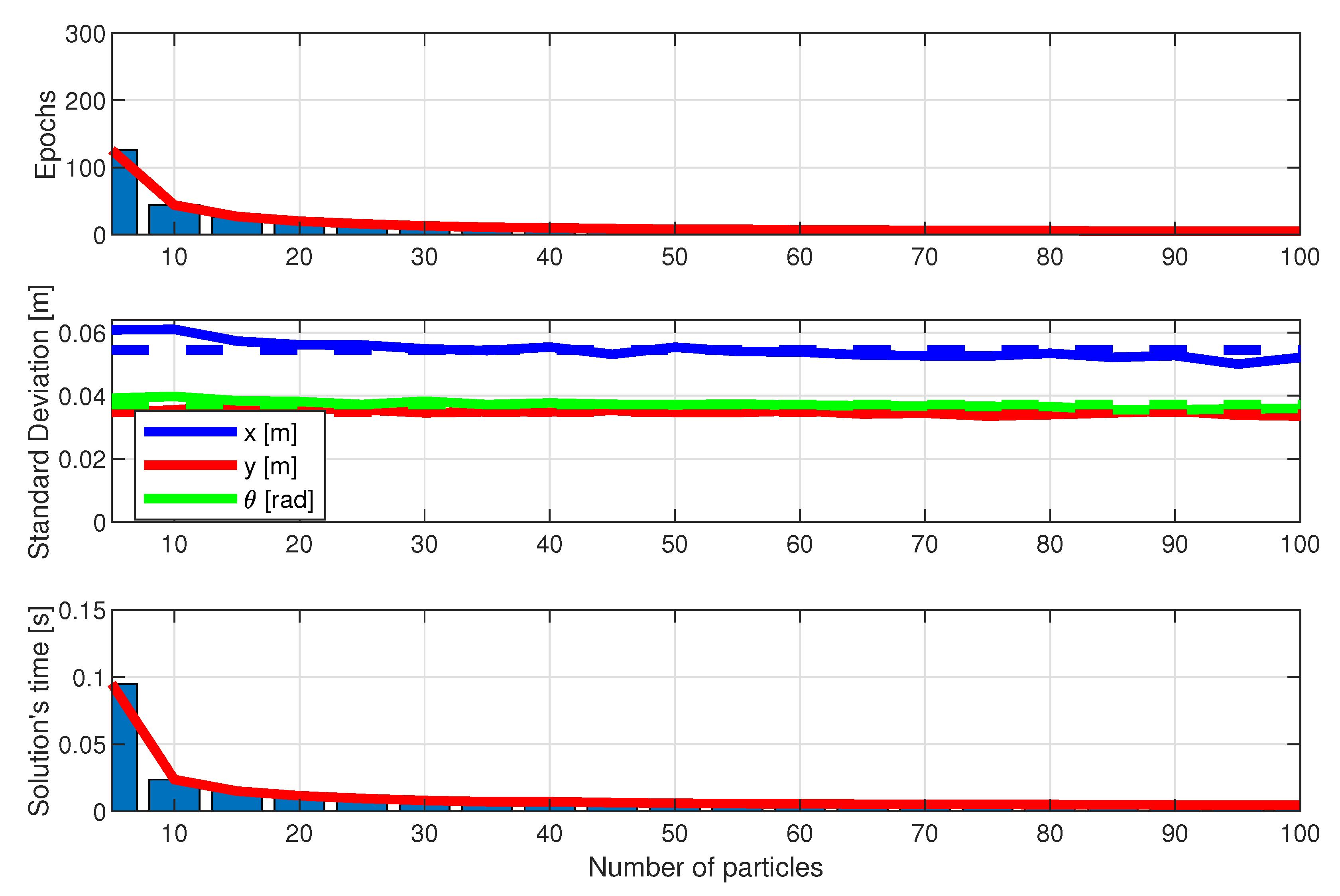

- Convergence Speed in Number of Epochs: The number of epochs required for each algorithm to converge to the final solution, that is, the estimated x, y robot position and its orientation , was measured. This criterion is important for assessing how quickly the algorithm reaches a viable solution, especially relevant for real-time applications and embedded systems.

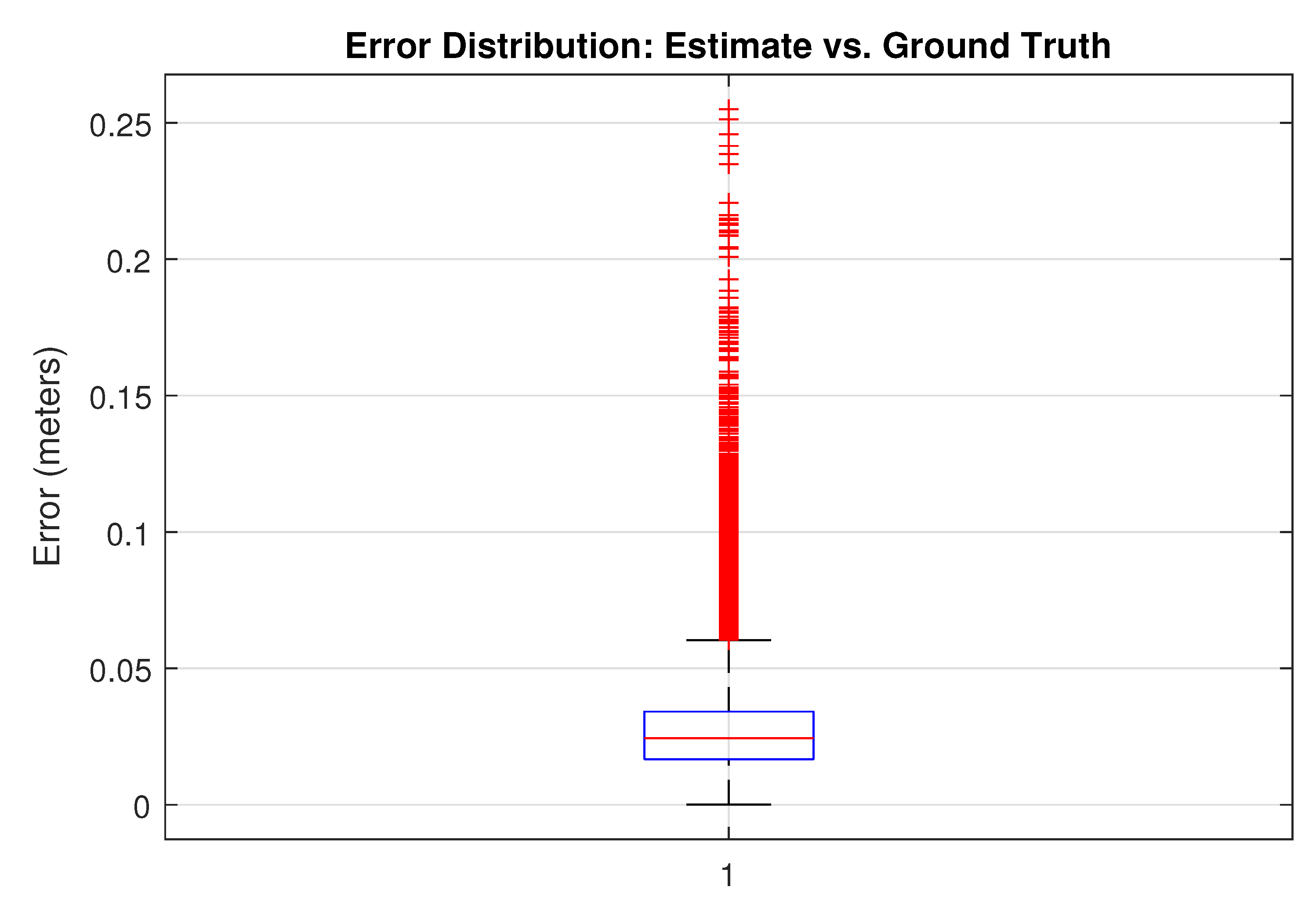

- Final Solution Quality: The solution quality was assessed by measuring the standard deviation of the difference between the algorithm’s estimated position and the robot’s true position. The standard deviation reflects the precision level of the algorithm’s estimate, with lower values indicating a closer approximation to the robot’s true position. This metric is particularly crucial in autonomous navigation systems, where high precision is necessary to avoid undesirable deviations.

- Computational Time: The execution time was measured in seconds for each method, allowing the assessment of computational efficiency. The same hardware was adopted in each case to allow a fair comparison. This criterion is essential as it indicates the computational cost of each algorithm, a metric especially relevant in systems with limited processing resources.

4.4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusion

Short Biography of Authors

Wolmar Araujo-Neto holds a Bachelor’s degree in Control and Automation Engineering from the Federal University of Ouro Preto (2012), a Master’s degree in Electrical Engineering from the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (2014), and a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from the same university (2019). He is currently a postdoctoral intern at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. He has experience in the field of Electrical Engineering, with an emphasis on Electronic Process Control and Feedback, and works mainly on topics such as robotics, control, artificial intelligence, optimization, PLC (Programmable Logic Controller), Petri nets, automata, energy efficiency, sustainability, and environmental comfort.

Wolmar Araujo-Neto holds a Bachelor’s degree in Control and Automation Engineering from the Federal University of Ouro Preto (2012), a Master’s degree in Electrical Engineering from the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (2014), and a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from the same university (2019). He is currently a postdoctoral intern at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. He has experience in the field of Electrical Engineering, with an emphasis on Electronic Process Control and Feedback, and works mainly on topics such as robotics, control, artificial intelligence, optimization, PLC (Programmable Logic Controller), Petri nets, automata, energy efficiency, sustainability, and environmental comfort. Leonardo Olivi is currently a professor in the Electrical Engineering - Robotics and Automation program at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF, 2014) and in the Graduate Program in Built Environment (PROAC, UFJF, 2024). He holds a degree in Control and Automation Engineering from the Federal University of Ouro Preto (UFOP, 2006), a master’s degree in Electrical Engineering with a focus on Automation and Control of Dynamic Systems from the University of São Paulo (USP, 2009), and a PhD in Electrical Engineering specializing in Automation and Mobile Robotics from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP, 2014). He coordinated the Electrical Engineering - Robotics and Automation program at UFJF from 2015 to 2018 and 2020 to 2023, and he coordinated the Laboratory of Robotics and Automation (LABRA) from 2018 to 2020. His main areas of expertise include mobile robotics and robotic manipulators, control of dynamic processes, stochastic process filtering, and artificial intelligence.

Leonardo Olivi is currently a professor in the Electrical Engineering - Robotics and Automation program at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF, 2014) and in the Graduate Program in Built Environment (PROAC, UFJF, 2024). He holds a degree in Control and Automation Engineering from the Federal University of Ouro Preto (UFOP, 2006), a master’s degree in Electrical Engineering with a focus on Automation and Control of Dynamic Systems from the University of São Paulo (USP, 2009), and a PhD in Electrical Engineering specializing in Automation and Mobile Robotics from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP, 2014). He coordinated the Electrical Engineering - Robotics and Automation program at UFJF from 2015 to 2018 and 2020 to 2023, and he coordinated the Laboratory of Robotics and Automation (LABRA) from 2018 to 2020. His main areas of expertise include mobile robotics and robotic manipulators, control of dynamic processes, stochastic process filtering, and artificial intelligence. Daniel Villa is a professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES). He holds a degree in Electrical Engineering from the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV), where he conducted research in control and automation. In 2017, he completed a master’s degree in Agricultural Engineering at UFV, focusing on synthesizing and implementing controllers for precision agriculture. In 2022, he earned his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from UFES, specializing in adaptive and sliding mode control applied to aerial robots, particularly for cargo transportation. He is an expert in robotics, control, and automation, with research interests that include control of multi-robot systems, nonlinear control, optimal control, and state estimation.

Daniel Villa is a professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES). He holds a degree in Electrical Engineering from the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV), where he conducted research in control and automation. In 2017, he completed a master’s degree in Agricultural Engineering at UFV, focusing on synthesizing and implementing controllers for precision agriculture. In 2022, he earned his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from UFES, specializing in adaptive and sliding mode control applied to aerial robots, particularly for cargo transportation. He is an expert in robotics, control, and automation, with research interests that include control of multi-robot systems, nonlinear control, optimal control, and state estimation. Mário Sarcinelli-Filho received the B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering from Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil, in 1979, and the M. Sc. and Ph. D. degrees, also in Electrical Engineering, from Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1983 and 1990, respectively. He is currently a Professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering, Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil, a researcher of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Senior Editor of the Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems, and a senior member of the Brazilian Society of Automatics, an IFAC national member organization. He has authored two books, co-authored more than 70 journal papers, over 370 conference papers, and 17 book chapters. He has also advised 22 Ph.D. and 28 M.Sc. students. His research interests are nonlinear control, mobile robot navigation, coordinated control of mobile robots, unmanned aerial vehicles, multi-articulated robotic vehicles, and coordinated control of ground and aerial robots.

Mário Sarcinelli-Filho received the B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering from Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil, in 1979, and the M. Sc. and Ph. D. degrees, also in Electrical Engineering, from Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1983 and 1990, respectively. He is currently a Professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering, Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil, a researcher of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Senior Editor of the Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems, and a senior member of the Brazilian Society of Automatics, an IFAC national member organization. He has authored two books, co-authored more than 70 journal papers, over 370 conference papers, and 17 book chapters. He has also advised 22 Ph.D. and 28 M.Sc. students. His research interests are nonlinear control, mobile robot navigation, coordinated control of mobile robots, unmanned aerial vehicles, multi-articulated robotic vehicles, and coordinated control of ground and aerial robots.Acknowledgments

| 1 |

References

- Liu, B. Recent advancements in autonomous robots and their technical analysis. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmokadem, T.; Savkin, A.V. Towards fully autonomous UAVs: A survey. Sensors 2021, 21, 6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; De Soto, B.G. On-site autonomous construction robots: A review of research areas, technologies, and suggestions for advancement. ISARC. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction. IAARC Publications, 2020, Vol. 37, pp. 385–392.

- Ohradzansky, M.T.; Rush, E.R.; Riley, D.G.; Mills, A.B.; Ahmad, S.; McGuire, S.; Biggie, H.; Harlow, K.; Miles, M.J.; Frew, E.W. Multi-agent autonomy: Advancements and challenges in subterranean exploration. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2110.04390. [Google Scholar]

- Sarcinelli-Filho, M.; Carelli, R. Control of Ground and Aerial Robots; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sarcinelli-Filho, M. Controle de sistemas multirrobos; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Melenbrink, N.; Werfel, J.; Menges, A. On-site autonomous construction robots: Towards unsupervised building. Automation in construction 2020, 119, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Neto, W.; Pinto, M.F.; Marcato, A.L.M.; da Silva, I.C.; Fernandes, D.A. Mobile Robot Localization Based on the Novel Leader-Based Bat Algorithm. Journal of Control, Automation and Electrical Systems 2019, 30, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nampoothiri, M.H.; Vinayakumar, B.; Sunny, Y.; Antony, R. Recent developments in terrain identification, classification, parameter estimation for the navigation of autonomous robots. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udupa, S.; Kamat, V.R.; Menassa, C.C. Shared autonomy in assistive mobile robots: a review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2023, 18, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. Probabilistic robotics, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S. A new metaheuristic bat-inspired algorithm. In Nature inspired cooperative strategies for optimization (NICSO 2010); Springer, 2010; pp. 65–74.

- Yang, X.S. Chapter 10 - Bat Algorithms. In Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms; Yang, X.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2014; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant-Whyte, H.; Bailey, T. Simultaneous localization and mapping: part I. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2006, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.H.; Shivanna, V.M.; Chen, J.S.; Guo, J.I. 360° Map Establishment and Real-Time Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Based on Equirectangular Projection for Autonomous Driving Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doucet, A.; de Freitas, N.; Gordon, N. An Introduction to Sequential Monte Carlo Methods. In Sequential Monte Carlo Methods in Practice; Doucet, A., de Freitas, N., Gordon, N., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2001; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms; Academic Press, 2020.

- Rodziewicz-Bielewicza, J.; Korzena, M. Sparse Convolutional Neural Network for Localization and Orientation Prediction and Application to Drone Control 2024.

- Sarcinelli-Filho, M.; Carelli, R. Motion Control. In Control of Ground and Aerial Robots; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L. Manta ray foraging optimization: An effective bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 87, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyolalam, V.; Kazem, A.A.P. Black widow optimization algorithm: a novel meta-heuristic approach for solving engineering optimization problems. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 87, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Error Metric | RMSE X (m) | RMSE Y (m) |

|---|---|---|

| LBBA | 0.0494 | 0.0238 |

| LBBA Filtered | 0.0789 | 0.0619 |

| Error Metric | RMSE X (m) | RMSE Y (m) |

|---|---|---|

| LBBA | 0.0330 | 0.0181 |

| LBBA Filtered | 0.0585 | 0.0659 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).