Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Ubiquitin Proteasomal System and UBR5 Structure

2. Functional Roles of UBR5

1. Role of UBR5 in DNA Damage Response (DDR)

UBR5 and ATMIN Interaction

UBR5 and TopBP1 Interaction

UBR5 and TRIP12 Interaction

UBR5 and Replication Fork Components Interaction

2. UBR5 in Metastasis and Therapeutic Resistance

UBR5 in Therapeutic Resistance and Anti-Apoptosis

UBR5 in Metastasis

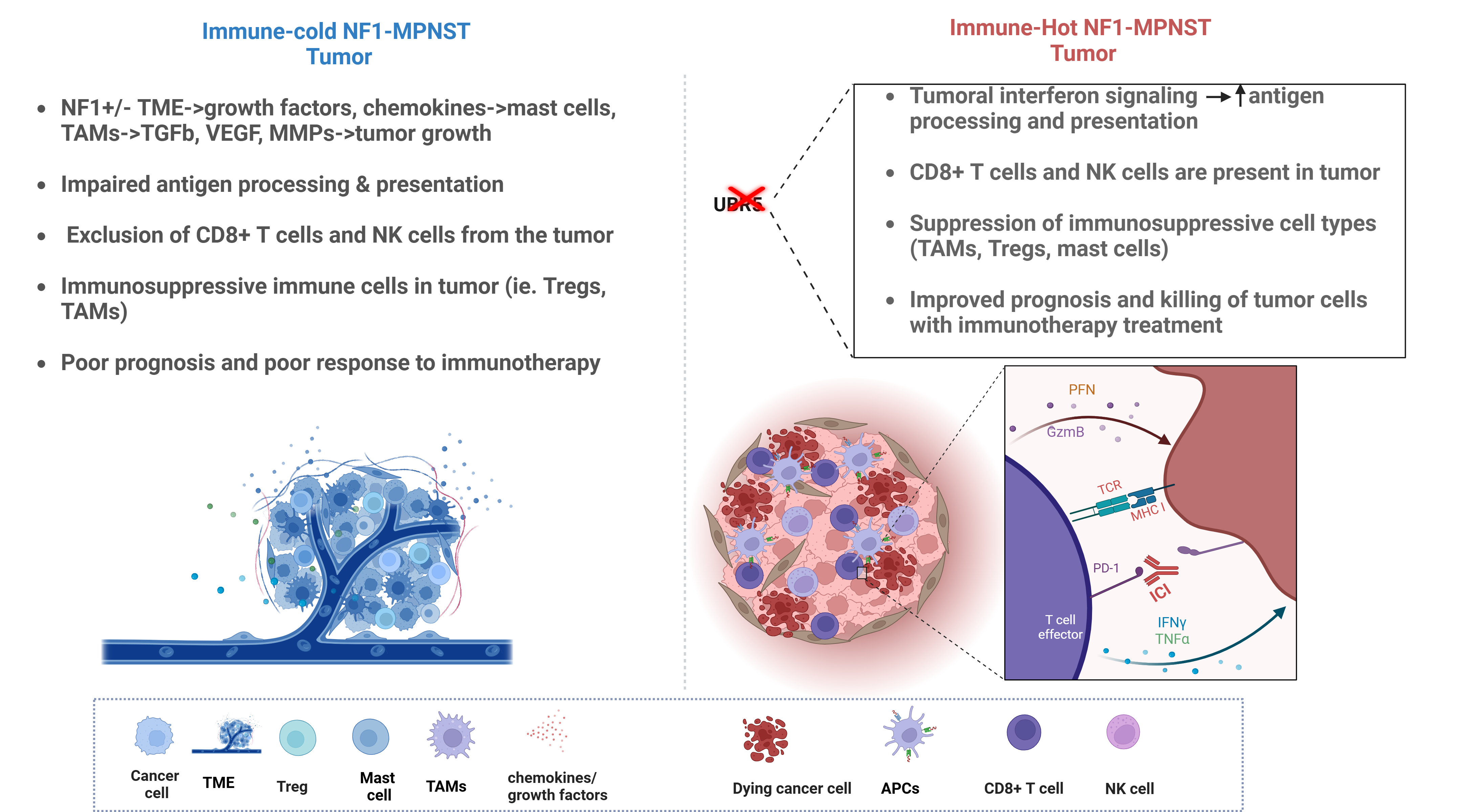

3. Role of UBR5 in Immune Modulation

4. UBR5 in MPNST: Therapeutic Potential

5. MPNST Immune Architecture: Mechanisms of Immune Evasion

6. Attempts to Enhance MPNST Immunogenicity: Prospects for ICB

Conclusion/Future Directions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao C, Zhou H, Dong Y, Alhaskawi A, Hasan Abdullah Ezzi S, Wang Z, Lai J, Goutham Kota V, Hasan Abdulla Hasan Abdulla M and Lu H 2023 Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Latest Concepts in Disease Pathogenesis and Clinical Management Cancers (Basel) 15 1077. [CrossRef]

- González-Muñoz T, Kim A, Ratner N and Peinado H 2022 The Need for New Treatments Targeting MPNST: The Potential of Strategies Combining MEK Inhibitors with Antiangiogenic Agents Clinical Cancer Research 28 3185–95. [CrossRef]

- Stucky C-C H, Johnson K N, Gray R J, Pockaj B A, Ocal I T, Rose P S and Wasif N 2012 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST): the Mayo Clinic experience Ann Surg Oncol 19 878–85. [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Ciriano I, Steele C D, Piculell K, Al-Ibraheemi A, Eulo V, Bui M M, Chatzipli A, Dickson B C, Borcherding D C, Feber A, Galor A, Hart J, Jones K B, Jordan J T, Kim R H, Lindsay D, Miller C, Nishida Y, Proszek P Z, Serrano J, Sundby R T, Szymanski J J, Ullrich N J, Viskochil D, Wang X, Snuderl M, Park P J, Flanagan A M, Hirbe A C, Pillay N and Miller D T 2023 Genomic Patterns of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST) Evolution Correlate with Clinical Outcome and Are Detectable in Cell-Free DNA Cancer Discov 13 654–71. [CrossRef]

- Miettinen M M, Antonescu C R, Fletcher C D M, Kim A, Lazar A J, Quezado M M, Reilly K M, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Stewart D R, Viskochil D, Widemann B and Perry A 2017 Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1—a consensus overview Human Pathology 67 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Prudner B C, Ball T, Rathore R and Hirbe A C 2020 Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Current practice and future perspectives Neurooncol Adv 2 i40–9. [CrossRef]

- Miller D T, Cortés-Ciriano I, Pillay N, Hirbe A C, Snuderl M, Bui M M, Piculell K, Al-Ibraheemi A, Dickson B C, Hart J, Jones K, Jordan J T, Kim R H, Lindsay D, Nishida Y, Ullrich N J, Wang X, Park P J and Flanagan A M 2020 Genomics of MPNST (GeM) Consortium: Rationale and Study Design for Multi-Omic Characterization of NF1-Associated and Sporadic MPNSTs Genes (Basel) 11 387. [CrossRef]

- Natalie Wu L M and Lu Q R 2019 Therapeutic targets for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors Future Neurology 14 FNL7. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Pollard K, Allen A N, Tomar T, Pijnenburg D, Yao Z, Rodriguez F J and Pratilas C A 2020 Combined Inhibition of SHP2 and MEK Is Effective in Models of NF1-Deficient Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors Cancer Research 80 5367–79. [CrossRef]

- Yan J, Chen Y, Patel A J, Warda S, Lee C J, Nixon B G, Wong E W P, Miranda-Román M A, Yang N, Wang Y, Pachai M R, Sher J, Giff E, Tang F, Khurana E, Singer S, Liu Y, Galbo P M, Maag J L V, Koche R P, Zheng D, Antonescu C R, Deng L, Li M O, Chen Y and Chi P 2022 Tumor-intrinsic PRC2 inactivation drives a context-dependent immune-desert microenvironment and is sensitized by immunogenic viruses J Clin Invest 132. [CrossRef]

- Hirbe A C, Dahiya S, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Verma I M, Clapp D W and Gutmann D H 2016 Spatially- and temporally-controlled postnatal p53 knockdown cooperates with embryonic Schwann cell precursor Nf1 gene loss to promote malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor formation Oncotarget 7 7403–14. [CrossRef]

- Magallon-Lorenz M, Terribas E, Fernández M, Requena G, Rosas I, Mazuelas H, Uriarte I, Negro A, Castellanos E, Blanco I, DeVries G, Kawashima H, Legius E, Brems H, Mautner V, Kluwe L, Ratner N, Wallace M, Rodriguez J F, Lázaro C, Fletcher J A, Reuss D, Carrió M, Gel B and Serra E 2022 A detailed landscape of genomic alterations in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor cell lines challenges the current MPNST diagnosis 2022.05.07.491026. [CrossRef]

- White E E and Rhodes S D 2024 The NF1+/- Immune Microenvironment: Dueling Roles in Neurofibroma Development and Malignant Transformation Cancers 16 994. [CrossRef]

- Staser K, Yang F-C and Clapp D W 2010 Mast cells and the neurofibroma microenvironment Blood 116 157–64. [CrossRef]

- Yang F-C, Ingram D A, Chen S, Zhu Y, Yuan J, Li X, Yang X, Knowles S, Horn W, Li Y, Zhang S, Yang Y, Vakili S T, Yu M, Burns D, Robertson K, Hutchins G, Parada L F and Clapp D W 2008 Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/-- and c-kit-dependent bone marrow Cell 135 437–48. [CrossRef]

- Wei S C, Duffy C R and Allison J P 2018 Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy Cancer Discovery 8 1069–86. [CrossRef]

- Somatilaka B N, Madana L, Sadek A, Chen Z, Chandrasekaran S, McKay R M and Le L Q 2024 STING activation reprograms the microenvironment to sensitize NF1-related malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors for immunotherapy J Clin Invest 134. [CrossRef]

- Johnson D B, Frampton G M, Rioth M J, Yusko E, Xu Y, Guo X, Ennis R C, Fabrizio D, Chalmers Z R, Greenbowe J, Ali S M, Balasubramanian S, Sun J X, He Y, Frederick D T, Puzanov I, Balko J M, Cates J M, Ross J S, Sanders C, Robins H, Shyr Y, Miller V A, Stephens P J, Sullivan R J, Sosman J A and Lovly C M 2016 Targeted Next Generation Sequencing Identifies Markers of Response to PD-1 Blockade Cancer Immunol Res 4 959–67. [CrossRef]

- Lee P R, Cohen J E and Fields R D 2006 Immune system evasion by peripheral nerve sheath tumor Neurosci Lett 397 126–9. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir B C, Bohanes P, Bisig B, Missiaglia E, Tsantoulis P, Coukos G, Montemurro M, Homicsko K and Michielin O 2019 Deep Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy of Metastatic Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor With CD274/PD-L1 Amplification JCO Precis Oncol 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Davis L E, Nicholls L A, Babiker H M, Liau J and Mahadevan D 2019 PD-1 Inhibition Achieves a Complete Metabolic Response in a Patient with Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Cancer Immunology Research 7 1396–400. [CrossRef]

- Payandeh M, Sadeghi M and Sadeghi E 2017 Complete Response to Pembrolizumab in a Patient with Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor: The First Case Reported J App Pharm Sci 7, 182–4. [CrossRef]

- Clancy J L, Henderson M J, Russell A J, Anderson D W, Bova R J, Campbell I G, Choong D Y, Macdonald G A, Mann G J, Nolan T, Brady G, Olopade O I, Woollatt E, Davies M J, Segara D, Hacker N F, Henshall S M, Sutherland R L and Watts C K 2003 EDD, the human orthologue of the hyperplastic discs tumour suppressor gene, is amplified and overexpressed in cancer Oncogene 22 5070–81. [CrossRef]

- Shearer R F, Iconomou M, Watts C K W and Saunders D N 2015 Functional Roles of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase UBR5 in Cancer Mol Cancer Res 13 1523–32. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Dai W, Ke Z and Li Y 2020 Functional roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases in gastric cancer (Review) Oncology Letters 20 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, He Q, Zhan W, Yu Z, Finkin-Groner E, Ma X, Lin G and Li H 2023 Structure of the human UBR5 E3 ubiquitin ligase Structure 31 541-552.e4. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Song M, Dong Q, Xiang G, Li J, Ma X and Wei F 2022 UBR5 promotes tumor immune evasion through enhancing IFN-γ-induced PDL1 transcription in triple negative breast cancer Theranostics 12 5086–102. [CrossRef]

- Taherbhoy A M and Daniels D L 2023 Harnessing UBR5 for targeted protein degradation of key transcriptional regulators Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 44 758–61. [CrossRef]

- Tsai J M, Aguirre J D, Li Y-D, Brown J, Focht V, Kater L, Kempf G, Sandoval B, Schmitt S, Rutter J C, Galli P, Sandate C R, Cutler J A, Zou C, Donovan K A, Lumpkin R J, Cavadini S, Park P M C, Sievers Q, Hatton C, Ener E, Regalado B D, Sperling M T, Słabicki M, Kim J, Zon R, Zhang Z, Miller P G, Belizaire R, Sperling A S, Fischer E S, Irizarry R, Armstrong S A, Thomä N H and Ebert B L 2023 UBR5 forms ligand-dependent complexes on chromatin to regulate nuclear hormone receptor stability Molecular Cell 83 2753-2767.e10. [CrossRef]

- Mark K G, Kolla S, Aguirre J D, Garshott D M, Schmitt S, Haakonsen D L, Xu C, Kater L, Kempf G, Martínez-González B, Akopian D, See S K, Thomä N H and Rapé M 2023 Orphan quality control shapes network dynamics and gene expression Cell 186 3460-3475.e23. [CrossRef]

- Hu B and Chen S 2024 The role of UBR5 in tumor proliferation and oncotherapy Gene 906 148258. [CrossRef]

- Xiang G, Wang S, Chen L, Song M, Song X, Wang H, Zhou P, Ma X and Yu J 2022 UBR5 targets tumor suppressor CDC73 proteolytically to promote aggressive breast cancer Cell Death Dis 13 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Song M, Dong Q, Xiang G, Li J, Ma X and Wei F 2022 UBR5 promotes tumor immune evasion through enhancing IFN-γ-induced PDL1 transcription in triple negative breast cancer Theranostics 12 5086–102. [CrossRef]

- Liao L, Song M, Li X, Tang L, Zhang T, Zhang L, Pan Y, Chouchane L and Ma X 2017 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase UBR5 Drives the Growth and Metastasis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cancer Research 77 2090–101. [CrossRef]

- Song M, Yeku O O, Rafiq S, Purdon T, Dong X, Zhu L, Zhang T, Wang H, Yu Z, Mai J, Shen H, Nixon B, Li M, Brentjens R J and Ma X 2020 Tumor derived UBR5 promotes ovarian cancer growth and metastasis through inducing immunosuppressive macrophages Nat Commun 11 6298. [CrossRef]

- Dehner C, Moon C I, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Miller C, Xu H, Wan X, Yang K, Mashl J, Gosline S J C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Godec A, Jones P A, Dahiya S, Bhatia H, Primeau T, Li S, Pollard K, Rodriguez F J, Ding L, Pratilas C A, Shern J F and Hirbe A C 2021 Chromosome 8 gain is associated with high-grade transformation in MPNST JCI Insight 6. [CrossRef]

- Høland M, Berg K C G, Eilertsen I A, Bjerkehagen B, Kolberg M, Boye K, Lingjærde O C, Guren T K, Mandahl N, Van Den Berg E, Palmerini E, Smeland S, Picci P, Mertens F, Sveen A and Lothe R A 2023 Transcriptomic subtyping of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours highlights immune signatures, genomic profiles, patient survival and therapeutic targets eBioMedicine 97 104829. [CrossRef]

- Akizuki Y, Kaypee S, Ohtake F and Ikeda F 2024 The emerging roles of non-canonical ubiquitination in proteostasis and beyond Journal of Cell Biology 223 e202311171. [CrossRef]

- Schnell J D and Hicke L 2003 Non-traditional functions of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins J Biol Chem 278 35857–60. [CrossRef]

- Sun A, Tian X, Chen Y, Yang W and Lin Q 2023 Emerging roles of the HECT E3 ubiquitin ligases in gastric cancer Pathol. Oncol. Res. 29 1610931. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Argiles-Castillo D, Kane E I, Zhou A and Spratt D E 2020 HECT E3 ubiquitin ligases - emerging insights into their biological roles and disease relevance J Cell Sci 133 jcs228072. [CrossRef]

- Hodáková Z, Grishkovskaya I, Brunner H L, Bolhuis D L, Belačić K, Schleiffer A, Kotisch H, Brown N G and Haselbach D 2023 Cryo-EM structure of the chain-elongating E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR5 The EMBO Journal 42 e113348. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Ng J and Sivaraman J 2021 Exploring the “Other” subfamily of HECT E3-ligases for therapeutic intervention Pharmacology & Therapeutics 224 107809. [CrossRef]

- Boughton A J, Krueger S and Fushman D 2020 Branching via K11 and K48 Bestows Ubiquitin Chains with a Unique Interdomain Interface and Enhanced Affinity for Proteasomal Subunit Rpn1 Structure 28 29-43.e6. [CrossRef]

- French M E, Koehler C F and Hunter T 2021 Emerging functions of branched ubiquitin chains Cell Discov 7 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mansfield E, Hersperger E, Biggs J and Shearn A 1994 Genetic and Molecular Analysis of hyperplastic discs, a Gene Whose Product Is Required for Regulation of Cell Proliferation in Drosophila melanogaster Imaginal Discs and Germ Cells Developmental Biology 165 507–26. [CrossRef]

- Swenson S A, Gilbreath T J, Vahle H, Hynes-Smith R W, Graham J H, Law H C-H, Amador C, Woods N T, Green M R and Buckley S M 2020 UBR5 HECT domain mutations identified in mantle cell lymphoma control maturation of B cells Blood 136 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Li C G, Mahon C, Sweeney N M, Verschueren E, Kantamani V, Li D, Hennigs J K, Marciano D P, Diebold I, Abu-Halawa O, Elliott M, Sa S, Guo F, Wang L, Cao A, Guignabert C, Sollier J, Nickel N P, Kaschwich M, Cimprich K A and Rabinovitch M 2019 PPARγ Interaction with UBR5/ATMIN Promotes DNA Repair to Maintain Endothelial Homeostasis Cell Reports 26 1333-1343.e7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Cronshaw J, Kanu N, Snijders A P and Behrens A 2014 UBR5-mediated ubiquitination of ATMIN is required for ionizing radiation-induced ATM signaling and function Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 12091–6. [CrossRef]

- Henderson M J, Munoz M A, Saunders D N, Clancy J L, Russell A J, Williams B, Pappin D, Khanna K K, Jackson S P, Sutherland R L and Watts C K W 2006 EDD Mediates DNA Damage-induced Activation of CHK2* Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 39990–40000. [CrossRef]

- Honda Y, Tojo M, Matsuzaki K, Anan T, Matsumoto M, Ando M, Saya H and Nakao M 2002 Cooperation of HECT-domain Ubiquitin Ligase hHYD and DNA Topoisomerase II-binding Protein for DNA Damage Response* Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 3599–605. [CrossRef]

- Munoz M A, Saunders D N, Henderson M J, Clancy J L, Russell A J, Lehrbach G, Musgrove E A, Watts C K W and Sutherland R L 2007 The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase EDD Regulates S-Phase and G2/M DNA Damage Checkpoints Cell Cycle 6 3070–7. [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson T, Altmeyer M, Savic V, Toledo L, Dinant C, Grøfte M, Bartkova J, Poulsen M, Oka Y, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Neumann B, Heriche J-K, Shearer R, Saunders D, Bartek J, Lukas J and Lukas C 2012 TRIP12 and UBR5 Suppress Spreading of Chromatin Ubiquitylation at Damaged Chromosomes Cell 150 697–709. [CrossRef]

- Cipolla L, Bertoletti F, Maffia A, Liang C-C, Lehmann A R, Cohn M A and Sabbioneda S 2019 UBR5 interacts with the replication fork and protects DNA replication from DNA polymerase η toxicity Nucleic Acids Research 47 11268–83. [CrossRef]

- Mardis E R 2019 Neoantigens and genome instability: impact on immunogenomic phenotypes and immunotherapy response Genome Med 11 71. [CrossRef]

- Chan T A, Yarchoan M, Jaffee E, Swanton C, Quezada S A, Stenzinger A and Peters S 2019 Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic Annals of Oncology 30 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Nowsheen S and Deng M 2023 DNA Repair Deficiency Regulates Immunity Response in Cancers: Molecular Mechanism and Approaches for Combining Immunotherapy Cancers (Basel) 15 1619. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura K, Huang N-J, Cocce K, Zhang L and Kornbluth S 2017 Downregulation of the proapoptotic protein MOAP-1 by the UBR5 ubiquitin ligase and its role in ovarian cancer resistance to cisplatin Oncogene 36 1698–706. [CrossRef]

- Ohtake F, Tsuchiya H, Saeki Y and Tanaka K 2018 K63 ubiquitylation triggers proteasomal degradation by seeding branched ubiquitin chains Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 E1401–8. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Zhao J, Mao Y, Lin G, Li F and Jiang Z 2020 UBR5 over-expression contributes to poor prognosis and tamoxifen resistance of ERa+ breast cancer by stabilizing β-catenin Breast Cancer Res Treat 184 699–710. [CrossRef]

- Qiao X, Liu Y, Prada M L, Mohan A K, Gupta A, Jaiswal A, Sharma M, Merisaari J, Haikala H M, Talvinen K, Yetukuri L, Pylvänäinen J W, Klefström J, Kronqvist P, Meinander A, Aittokallio T, Hietakangas V, Eilers M and Westermarck J 2020 UBR5 Is Coamplified with MYC in Breast Tumors and Encodes an Ubiquitin Ligase That Limits MYC-Dependent Apoptosis Cancer Research 80 1414–27. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Dong X, Song M, Xu A, He Q, Li H, Ouyang W, Chouchane L and Ma X 2024 Targeting UBR5 inhibits postsurgical breast cancer lung metastases by inducing CDC73 and p53 mediated apoptosis International Journal of Cancer 154 723–37. [CrossRef]

- Bradley A, Zheng H, Ziebarth A, Sakati W, Branham-O’Connor M, Blumer J B, Liu Y, Kistner-Griffin E, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood A K, Landen C N and Eblen S T 2014 EDD enhances cell survival and cisplatin resistance and is a therapeutic target for epithelial ovarian cancer Carcinogenesis 35 1100–9. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhang W, Gao J, Du M, Li H, Li M, Cong H, Fang Y, Liang Y, Zhao D, Xiang G, Ma X, Yao M, Tu H and Gan Y 2021 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase UBR5 Promotes the Metastasis of Pancreatic Cancer via Destabilizing F-Actin Capping Protein CAPZA1 Front Oncol 11 634167. [CrossRef]

- Subbaiah V K, Zhang Y, Rajagopalan D, Abdullah L N, Yeo-Teh N S L, Tomaić V, Banks L, Myers M P, Chow E K and Jha S 2016 E3 ligase EDD1/UBR5 is utilized by the HPV E6 oncogene to destabilize tumor suppressor TIP60 Oncogene 35 2062–74. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Jiang N, Cao Q, Ma M and Sun Q 2016 The E3 ligase UBR5 regulates gastric cancer cell growth by destabilizing the tumor suppressor GKN1 Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 478 1624–9. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Zhao X, Jin L, Wu G and Yang Y 2017 UBR5 Contributes to Colorectal Cancer Progression by Destabilizing the Tumor Suppressor ECRG4 Dig Dis Sci 62 2781–9. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Liu L, Feng Y, Wang L, Liu X and Li Y 2022 UBR5 promotes migration and invasion of glioma cells by regulating the ECRG4/NF-κB pathway J Biosci 47 45. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Wang J, Chu M, Liu Y, Wang Z and Zhu X 2021 Emerging Role of Ubiquitination in the Regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancer Immunotherapy Mol Ther 29 908–19. [CrossRef]

- Layman A A K and Oliver P M 2016 Ubiquitin Ligases and Deubiquitinating Enzymes in CD4+ T Cell Effector Fate Choice and Function The Journal of Immunology 196 3975–82. [CrossRef]

- Li X-M, Zhao Z-Y, Yu X, Xia Q-D, Zhou P, Wang S-G, Wu H-L and Hu J 2023 Exploiting E3 ubiquitin ligases to reeducate the tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy Experimental Hematology & Oncology 12 34. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Bian C, Zhao X and Yi T 2022 Efficacy evaluation of multi-immunotherapy in ovarian cancer: From bench to bed Front Immunol 13 1034903. [CrossRef]

- Siminiak N, Czepczyński R, Zaborowski M P and Iżycki D 2022 Immunotherapy in Ovarian Cancer Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 70 19. [CrossRef]

- Rouzbahani E, Majidpoor J, Najafi S and Mortezaee K 2022 Cancer stem cells in immunoregulation and bypassing anti-checkpoint therapy Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 156 113906. [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Liu D and Li L 2020 PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer Am J Cancer Res 10 727–42.

- Yi M, Niu M, Xu L, Luo S and Wu K 2021 Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment J Hematol Oncol 14 10. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Aminu B, Roscow O and Zhang W 2021 Targeting the Ubiquitin Signaling Cascade in Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22 791. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi Y, Tanegashima T, Sato E, Irie T, Sai A, Itahashi K, Kumagai S, Tada Y, Togashi Y, Koyama S, Akbay E A, Karasaki T, Kataoka K, Funaki S, Shintani Y, Nagatomo I, Kida H, Ishii G, Miyoshi T, Aokage K, Kakimi K, Ogawa S, Okumura M, Eto M, Kumanogoh A, Tsuboi M and Nishikawa H 2021 Highly immunogenic cancer cells require activation of the WNT pathway for immunological escape Science Immunology 6. [CrossRef]

- Knight S W E, Knight T E, Santiago T, Murphy A J and Abdelhafeez A H 2022 Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors—A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Multidisciplinary Management Children (Basel) 9 38. [CrossRef]

- Bethard J R, Zheng H, Roberts L and Eblen S T 2011 Identification of phosphorylation sites on the E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR5/EDD Journal of Proteomics 75 603–9. [CrossRef]

- Eblen S T, Kumar N V, Shah K, Henderson M J, Watts C K W, Shokat K M and Weber M J 2003 Identification of Novel ERK2 Substrates through Use of an Engineered Kinase and ATP Analogs* Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 14926–35. [CrossRef]

- Abeshouse A, Adebamowo C, Adebamowo S N, Akbani R, Akeredolu T, Ally A, Anderson M L, Anur P, Appelbaum E L, Armenia J, Auman J T, Bailey M H, Baker L, Balasundaram M, Balu S, Barthel F P, Bartlett J, Baylin S B, Behera M, Belyaev D, Bennett J, Benz C, Beroukhim R, Birrer M, Bocklage T, Bodenheimer T, Boice L, Bootwalla M S, Bowen J, Bowlby R, Boyd J, Brohl A S, Brooks D, Byers L, Carlsen R, Castro P, Chen H-W, Cherniack A D, Chibon F, Chin L, Cho J, Chuah E, Chudamani S, Cibulskis C, Cooper L A D, Cope L, Cordes M G, Crain D, Curley E, Danilova L, Dao F, Davis I J, Davis L E, Defreitas T, Delman K, Demchok J A, Demetri G D, Demicco E G, Dhalla N, Diao L, Ding L, DiSaia P, Dottino P, Doyle L A, Drill E, Dubina M, Eschbacher J, Fedosenko K, Felau I, Ferguson M L, Frazer S, Fronick C C, Fulidou V, Fulton L A, Fulton R S, Gabriel S B, Gao J, Gao Q, Gardner J, Gastier-Foster J M, Gay C M, Gehlenborg N, Gerken M, Getz G, Godwin A K, Godwin E M, Gordienko E, Grilley-Olson J E, Gutman D A, Gutmann D H, Hayes D N, Hegde A M, Heiman D I, Heins Z, Helsel C, Hepperla A J, Higgins K, Hoadley K A, et al 2017 Comprehensive and Integrated Genomic Characterization of Adult Soft Tissue Sarcomas Cell 171 950-965.e28. [CrossRef]

- Alvegard T A, Berg N O, Baldetorp B, Fernö M, Killander D, Ranstam J, Rydholm A and Akerman M 1990 Cellular DNA content and prognosis of high-grade soft tissue sarcoma: the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group experience J Clin Oncol 8 538–47. [CrossRef]

- Brekke H R, Ribeiro F R, Kolberg M, Agesen T H, Lind G E, Eknaes M, Hall K S, Bjerkehagen B, van den Berg E, Teixeira M R, Mandahl N, Smeland S, Mertens F, Skotheim R I and Lothe R A 2010 Genomic changes in chromosomes 10, 16, and X in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors identify a high-risk patient group J Clin Oncol 28 1573–82. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Ylipää A, Sun Y, Zheng H, Chen K, Nykter M, Trent J, Ratner N, Lev D C and Zhang W 2011 Genomic and Molecular Characterization of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Identifies the IGF1R Pathway as a Primary Target for Treatment Clinical Cancer Research 17 7563–73. [CrossRef]

- Hallqvist A, Rohlin A and Raghavan S 2020 Immune checkpoint blockade and biomarkers of clinical response in non–small cell lung cancer Scand J Immunol 92 e12980. [CrossRef]

- Huang A C and Zappasodi R 2022 A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance Nat Immunol 23 660–70. [CrossRef]

- Paudel S N, Hutzen B and Cripe T P 2023 The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope? Mol Ther Oncolytics 30 227–37. [CrossRef]

- Dodd R D, Lee C-L, Overton T, Huang W, Eward W C, Luo L, Ma Y, Ingram D R, Torres K E, Cardona D M, Lazar A J and Kirsch D G 2017 NF1+/− hematopoietic cells accelerate malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor development without altering chemotherapy response Cancer Res 77 4486–97. [CrossRef]

- Manji G A, Van Tine B A, Lee S M, Raufi A G, Pellicciotta I, Hirbe A C, Pradhan J, Chen A, Rabadan R and Schwartz G K 2021 A Phase I Study of the Combination of Pexidartinib and Sirolimus to Target Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Unresectable Sarcoma and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors Clinical Cancer Research 27 5519–27. [CrossRef]

- Martin E, Lamba N, Flucke U E, Verhoef C, Coert J H, Versleijen-Jonkers Y M H and Desar I M E 2019 Non-cytotoxic systemic treatment in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST): A systematic review from bench to bedside Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 138 223–32. [CrossRef]

- Larsson A T, Bhatia H, Calizo A, Pollard K, Zhang X, Conniff E, Tibbitts J F, Rono E, Cummins K, Osum S H, Williams K B, Crampton A L, Jubenville T, Schefer D, Yang K, Lyu Y, Pino J C, Bade J, Gross J M, Lisok A, Dehner C A, Chrisinger J S A, He K, Gosline S J C, Pratilas C A, Largaespada D A, Wood D K and Hirbe A C 2023 Ex vivo to in vivo model of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors for precision oncology Neuro Oncol 25 2044–57. [CrossRef]

- Haworth K B, Arnold M A, Pierson C R, Choi K, Yeager N D, Ratner N, Roberts R D, Finlay J L and Cripe T P 2017 Immune profiling of NF1-associated tumors reveals histologic subtype distinctions and heterogeneity: implications for immunotherapy Oncotarget 8 82037–48. [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar A R, Bhandarkar S, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Parney I F and Spinner R J 2023 Characterizing T-cell dysfunction and exclusion signatures in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors reveals susceptibilities to immunotherapy J Neurooncol 164 693–9. [CrossRef]

- Negrao M V, Lam V K, Reuben A, Rubin M L, Landry L L, Roarty E B, Rinsurongkawong W, Lewis J, Roth J A, Swisher S G, Gibbons D L, Wistuba I I, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Glisson B S, Blumenschein G R, Lee J J, Heymach J V and Zhang J 2019 PD-L1 Expression, Tumor Mutational Burden, and Cancer Gene Mutations Are Stronger Predictors of Benefit from Immune Checkpoint Blockade than HLA Class I Genotype in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Journal of Thoracic Oncology 14 1021–31. [CrossRef]

- Lei Y, Li X, Huang Q, Zheng X and Liu M 2021 Progress and Challenges of Predictive Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Blockade Front Oncol 11 617335. [CrossRef]

- Budczies J, Mechtersheimer G, Denkert C, Klauschen F, Mughal S S, Chudasama P, Bockmayr M, Jöhrens K, Endris V, Lier A, Lasitschka F, Penzel R, Dietel M, Brors B, Gröschel S, Glimm H, Schirmacher P, Renner M, Fröhling S and Stenzinger A 2017 PD-L1 (CD274) copy number gain, expression, and immune cell infiltration as candidate predictors for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in soft-tissue sarcoma Oncoimmunology 6 e1279777. [CrossRef]

- Shurell E, Singh A S, Crompton J G, Jensen S, Li Y, Dry S, Nelson S, Chmielowski B, Bernthal N, Federman N, Tumeh P and Eilber F C 2016 Characterizing the immune microenvironment of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor by PD-L1 expression and presence of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes Oncotarget 7 64300–8. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell D K, Burgess B, White E E, Smith A E, Sierra Potchanant E A, Mang H, Hickey B E, Lu Q, Qian S, Bessler W, Li X, Jiang L, Brewster K, Temm C, Horvai A, Albright E A, Fishel M L, Pratilas C A, Angus S P, Clapp D W and Rhodes S D 2024 Spatial Gene-Expression Profiling Unveils Immuno-oncogenic Programs of NF1-Associated Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Progression Clinical Cancer Research OF1–16. [CrossRef]

- Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, Chung H C, Kindler H L, Lopez-Martin J A, Miller W H, Italiano A, Kao S, Piha-Paul S A, Delord J-P, McWilliams R R, Fabrizio D A, Aurora-Garg D, Xu L, Jin F, Norwood K and Bang Y-J 2020 Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study The Lancet Oncology 21 1353–65. [CrossRef]

- Roulleaux Dugage M, Nassif E F, Italiano A and Bahleda R 2021 Improving Immunotherapy Efficacy in Soft-Tissue Sarcomas: A Biomarker Driven and Histotype Tailored Review Front Immunol 12 775761. [CrossRef]

- Chalmers Z R, Connelly C F, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali S M, Ennis R, Schrock A, Campbell B, Shlien A, Chmielecki J, Huang F, He Y, Sun J, Tabori U, Kennedy M, Lieber D S, Roels S, White J, Otto G A, Ross J S, Garraway L, Miller V A, Stephens P J and Frampton G M 2017 Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden Genome Medicine 9 34. [CrossRef]

- Brohl A S, Kahen E, Yoder S J, Teer J K and Reed D R 2017 The genomic landscape of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diverse drivers of Ras pathway activation Sci Rep 7 14992. [CrossRef]

- Ghonime M G, Saini U, Kelly M C, Roth J C, Wang P-Y, Chen C-Y, Miller K, Hernandez-Aguirre I, Kim Y, Mo X, Stanek J R, Cripe T, Mardis E and Cassady K A 2021 Eliciting an immune-mediated antitumor response through oncolytic herpes simplex virus-based shared antigen expression in tumors resistant to viroimmunotherapy J Immunother Cancer 9 e002939. [CrossRef]

- Yan J, Chen Y, Patel A J, Warda S, Nixon B G, Wong E W P, Miranda-Román M A, Lee C J, Yang N, Wang Y, Sher J, Giff E, Tang F, Khurana E, Singer S, Liu Y, Galbo P M, Maag J L, Koche R P, Zheng D, Deng L, Antonescu C R, Li M, Chen Y and Chi P 2022 Tumor-intrinsic PRC2 inactivation drives a context-dependent immune-desert tumor microenvironment and confers resistance to immunotherapy. [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer J L, Lingo J J, Kaemmer C A, Scherer A, Warrier A, Voigt E, Raygoza Garay J A, McGivney G R, Brockman Q R, Tang A, Calizo A, Pollard K, Zhang X, Hirbe A C, Pratilas C A, Leidinger M, Breheny P, Chimenti M S, Sieren J C, Monga V, Tanas M R, Meyerholz D K, Darbro B W, Dodd R D and Quelle D E 2023 CDK4/6-MEK Inhibition in MPNSTs Causes Plasma Cell Infiltration, Sensitization to PD-L1 Blockade, and Tumor Regression Clinical Cancer Research 29 3484–97. [CrossRef]

- Laumont C M, Banville A C, Gilardi M, Hollern D P and Nelson B H 2022 Tumour-infiltrating B cells: immunological mechanisms, clinical impact and therapeutic opportunities Nat Rev Cancer 22 414–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu J, Liang C, Hua J, Meng Q, Yu X and Shi S 2024 Intratumoral CD38+CD19+B cells associate with poor clinical outcomes and immunosuppression in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma eBioMedicine 103. [CrossRef]

- Playoust E, Remark R, Vivier E and Milpied P 2023 Germinal center-dependent and -independent immune responses of tumor-infiltrating B cells in human cancers Cell Mol Immunol 20 1040–50. [CrossRef]

- Sanz I, Wei C, Jenks S A, Cashman K S, Tipton C, Woodruff M C, Hom J and Lee F E-H 2019 Challenges and Opportunities for Consistent Classification of Human B Cell and Plasma Cell Populations Front. Immunol. 10. [CrossRef]

- Xu-Monette Z Y, Li Y, Snyder T, Yu T, Lu T, Tzankov A, Visco C, Bhagat G, Qian W, Dybkaer K, Chiu A, Tam W, Zu Y, Hsi E D, Hagemeister F B, Wang Y, Go H, Ponzoni M, Ferreri A J M, Møller M B, Parsons B M, Fan X, van Krieken J H, Piris M A, Winter J N, Au Q, Kirsch I, Zhang M, Shaughnessy J, Xu B and Young K H 2023 Tumor-Infiltrating Normal B Cells Revealed by Immunoglobulin Repertoire Clonotype Analysis Are Highly Prognostic and Crucial for Antitumor Immune Responses in DLBCL Clinical Cancer Research 29 4808–21. [CrossRef]

| No. | Study Name | Phase | Agent | Clinical Trial No. | Modality | Status/Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PLX3397 Plus Sirolimus in Unresectable Sarcoma and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (PLX3397) | I & II | PLX3397, Sirolimus | NCT02584647 | Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Active, not recruiting; patient enrollment: 43; interventional model: parallel assignment Clinical benefit was observed in 12 of 18 (67%) evaluable subjects with 3 partial responses (all in TGCT) and 9 stable disease. Tissue staining indicated a decreased proportion of activated M2 macrophages within tumor samples with treatment. Manji GA, Van Tine BA, Lee SM, et al. A Phase I Study of the Combination of Pexidartinib and Sirolimus to Target Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Unresectable Sarcoma and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(20):5519-5527. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1779 |

Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 2. | Vaccine Therapy in Treating Patients With Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor That Is Recurrent or Cannot Be Removed by Surgery | I | Edmonston strain measles virus genetically engineered to express neurofibromatosis type 1 (oncolytic measles virus encoding thyroidal sodium-iodide symporter [MV-NIS]) | NCT02700230 | Oncolytic virus | Completed; patient enrollment: 9; interventional model: single group assignment | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 3. | Neoadjuvant Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Newly Diagnosed Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor | I | nivolumab and ipilimumab | NCT04465643 | Immune modulators (PD-1 and CTLA-4) | Recruiting; patient enrollment: 18; interventional model: single group assignment | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 4. | A Study of APG-115 in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Patients With Metastatic Melanomas or Advanced Solid Tumors | Ib/II | APG-115 and pembrolizumab | NCT03611868 | Immune modulator (PD-1) and small molecule inhibitor | Recruiting Interim results show stability in 53% of MPNST cohort when treated for > 4 cycles Somaiah N, Van Tine BA, Chmielowski B, et al. A phase 2 study of alrizomadlin, a novel MDM2/p53 inhibitor, in combination with pembrolizumab for treatment of patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023;41(16_suppl):e14627. doi:10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e14627 |

Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 5. | B7H3 CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy for Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors in Children and Young Adults | I | Biological: second generation 4-1BBζ B7H3-EGFRt-DHFR (B7H3-specific CAR-T cells and CD19 specific CAR-T cells) biological: second generation 4-1BBζ B7H3-EGFRt-DHFR (selected) and a second generation 4-1BBζ CD19-Her2tG | NCT04483778 | CAR-T cells | Active, not recruiting | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 6. | EGFR806 CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy for Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors in Children and Young Adults | I | Biological: second generation 4-1BBζ EGFR806-EGFRt biological: second generation 4-1BBζ EGFR806-EGFRt and a second generation 4 1BBζ CD19-Her2tG | NCT03618381 | CAR-T cells | Recruiting | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 7. | Donor Stem Cell Transplant After Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Recurrent or Refractory High-Risk Solid Tumors in Pediatric and Adolescent-Young Adults | II | Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | NCT04530487 | Stem cell transfer | Terminated | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 8. | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Treating Patients With Rare Tumors | II | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab | NCT02834013 | Immune modulators (PD-1 and CTLA-4) | Active, not recruiting | Paudel SN, Hutzen B, Cripe TP. The quest for effective immunotherapies against malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Is there hope?. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;30:227-237. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.07.008 |

| 9. | A Study of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST), Not Eligible for Curative Surgery | II | Pembrolizumab | NCT02691026 | Immune modulators | Terminated | |

| 10. | Lorvotuzumab Mertansine in Treating Younger Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Wilms Tumor, Rhabdomyosarcoma, Neuroblastoma, Pleuropulmonary Blastoma, Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor, or Synovial Sarcoma | II | Lorvotuzumab mertansine | NCT02452554 | Antibody-drug conjugates | Clinical activity limited Geller JI, Pressey JG, Smith MA, et al. ADVL1522: A phase 2 study of lorvotuzumab mertansine (IMGN901) in children with relapsed or refractory wilms tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, pleuropulmonary blastoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, or synovial sarcoma-A Children's Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2020;126(24):5303-5310. doi:10.1002/cncr.33195 |

|

| 11. | BLESSED: Expanded Access for DeltaRex-G for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer, Sarcoma and Carcinoma of Breast | I/II | DeltaRex-G | NCT04091295 | Tumor targeted gene therapy, human cyclin G1 inhibitor | Available Case report: 14-year-old female with MPNST of parotid gland with lung metastases Previous treatment include: chemotherapies (doxorubicin, ifosfamide, temozolomide, sorafenib), and immunotherapy with interleukin-2. Received intravenous Rexin-G for 2 years. Outcome: no evidence of active disease Kim S, Federman N, Gordon EM, Hall FL, Chawla SP. Rexin-G®, a tumor-targeted retrovector for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6(6):861-865. doi:10.3892/mco.2017.1231 |

|

| 12. | HSV1716 in Patients With Non-Central Nervous System (Non-CNS) Solid Tumors | I | HSV1716 | NCT00931931 | Oncolytic virus | Completed | |

| 13. | MASCT-I Combined With Doxorubicin and Ifosfamide for First-line Treatment of Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcoma | II | MASCT-I (dendritic cells and effector T cells injections) with Doxorubicin and Ifosfamide | NCT06277154 | MASCT-I | Not yet recruiting | |

| 14. | Nivolumab and BO-112 Before Surgery for the Treatment of Resectable Soft Tissue Sarcoma | I | BO-112, and BO-112 with nivolumab for patients going through preoperative radiotherapy for definitive surgical resection | NCT04420975 | dsRNA immunotherapy | Active, not recruiting |

| No. | Study Name | Agent | Modality | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Treatment of orthotopic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors with oncolytic herpes simplex virus | Oncolytic herpes simplex viruses (oHSVs) | Oncolytic virus | Antoszczyk S, Spyra M, Mautner VF, et al. Treatment of orthotopic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors with oncolytic herpes simplex virus. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(8):1057-1066. doi:10.1093/neuonc/not317 |

| 2. | Aurora A kinase inhibition enhances oncolytic herpes virotherapy through cytotoxic synergy and innate cellular immune modulation | Alisertib and HSV1716 | Oncolytic virus | Currier MA, Sprague L, Rizvi TA, et al. Aurora A kinase inhibition enhances oncolytic herpes virotherapy through cytotoxic synergy and innate cellular immune modulation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(11):17412-17427. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.14885 |

| 3 | Dominant-Negative Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Expression Enhances Antitumoral Potency of Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus in Neural Tumors | Oncolytic HSV with dominant-negative FGF receptor (dnFGFR) | Oncolytic virus | Liu TC, Zhang T, Fukuhara H, et al. Dominant-negative fibroblast growth factor receptor expression enhances antitumoral potency of oncolytic herpes simplex virus in neural tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(22):6791-6799. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0263 |

| 4. | Oncolytic HSV Armed with Platelet Factor 4, an Antiangiogenic Agent, Shows Enhanced Efficacy | Oncolytic HSV with insertion of transgene platelet factor 4 (PF4) | Oncolytic virus | Liu TC, Zhang T, Fukuhara H, et al. Oncolytic HSV armed with platelet factor 4, an antiangiogenic agent, shows enhanced efficacy. Mol Ther. 2006;14(6):789-797. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.07.011 |

| 5. | Oncolytic HSV and Erlotinib Inhibit Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis in a Novel Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Xenograft Model | oHSV mutants (G207 and hrR3) with erlotinib (EGFR inhibitor) | Oncolytic virus | Mahller YY, Vaikunth SS, Currier MA, et al. Oncolytic HSV and erlotinib inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis in a novel malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor xenograft model. Mol Ther. 2007;15(2):279-286. doi:10.1038/sj.mt.6300038 |

| 6. | Molecular analysis of human cancer cells infected by an oncolytic HSV-1 reveals multiple upregulated cellular genes and a role for SOCS1 in virus replication | G207 oHSV | Oncolytic virus | Mahller YY, Sakthivel B, Baird WH, et al. Molecular analysis of human cancer cells infected by an oncolytic HSV-1 reveals multiple upregulated cellular genes and a role for SOCS1 in virus replication. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15(11):733-741. doi:10.1038/cgt.2008.40 |

| 7. | Molecular engineering and validation of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 transcriptionally targeted to midkine-positive tumors | oHSV fused with human MDK promoter to the HSV type 1 neurovirulence gene, γ134.5 | Oncolytic virus | Maldonado AR, Klanke C, Jegga AG, et al. Molecular engineering and validation of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 transcriptionally targeted to midkine-positive tumors. J Gene Med. 2010;12(7):613-623. doi:10.1002/jgm.1479 |

| 8. | Oncolytic measles virus as a novel therapy for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors | Engineered MV Edmonston vaccine strain with human sodium iodide symporter | Oncolytic measles virus therapy | Deyle DR, Escobar DZ, Peng KW, Babovic-Vuksanovic D. Oncolytic measles virus as a novel therapy for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Gene. 2015;565(1):140-145. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.001 |

| 9. | STING activation reprograms the microenvironment to sensitize NF1-related malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors for immunotherapy | Activating simulator of IFN genes (STING) signaling with ICB | ICB + tumor microenvironment | Somatilaka BN, Madana L, Sadek A, et al. STING activation reprograms the microenvironment to sensitize NF1-related malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors for immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(10):e176748. Published 2024 Mar 19. doi:10.1172/JCI176748 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).