Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

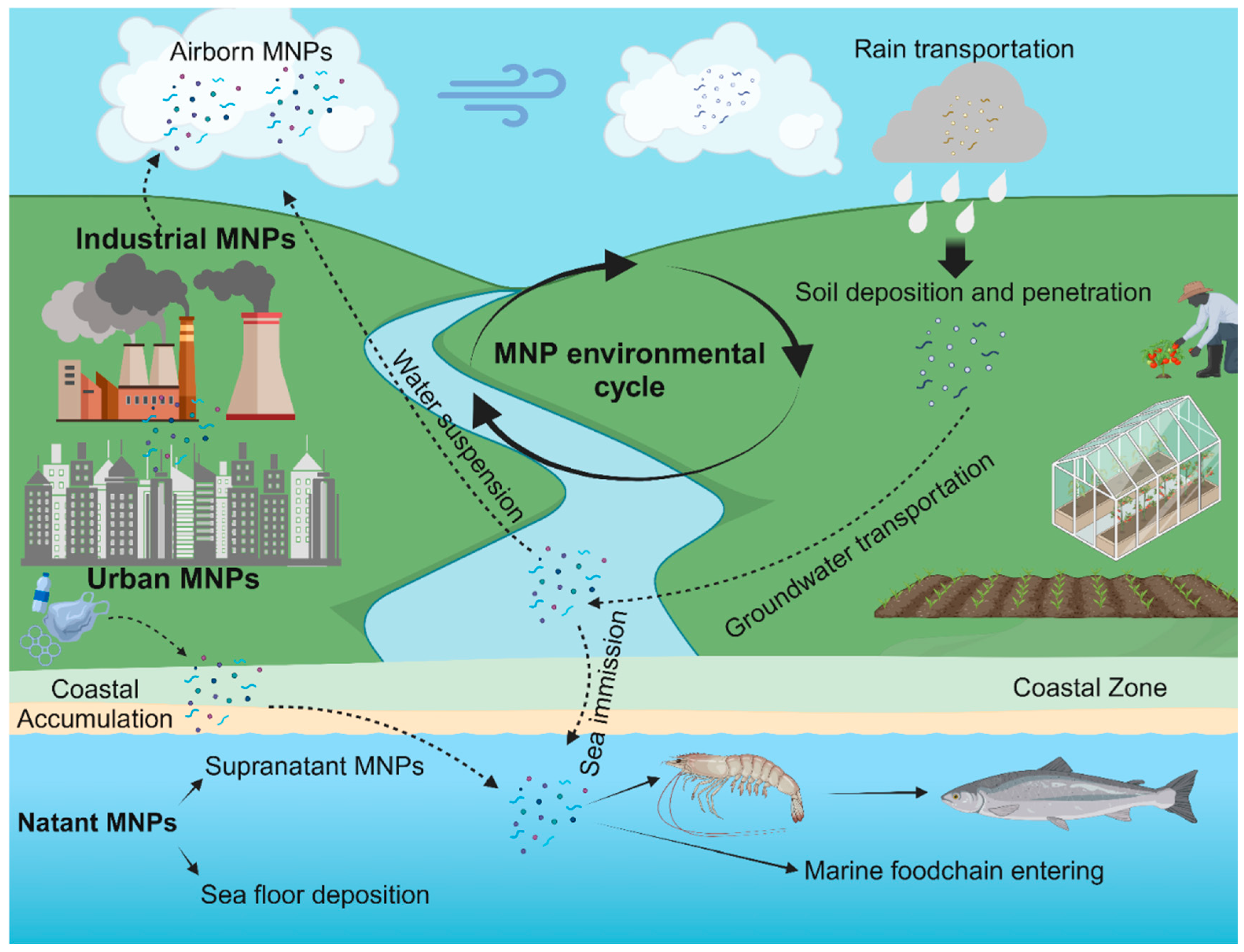

2. Micro-Nanoplastics: Definition and Eco-Toxicology

2.1. Definitions and General Considerations

2.2. Routes of Human Exposure

2.2.1. Ingestion

2.2.2. Inhalation

2.2.3. Dermal Absorption

3. MNPs: Analytical Methods in Biological Studies

3.1. Surrogate Model Studies

3.2. In Vivo Imaging Techniques

3.3. EX Vivo Studies

4. Human Health-Risk of MNP Exposure

4.1. Digestive Health

4.2. Respiratory Health

4.3. Cardiovascular Health

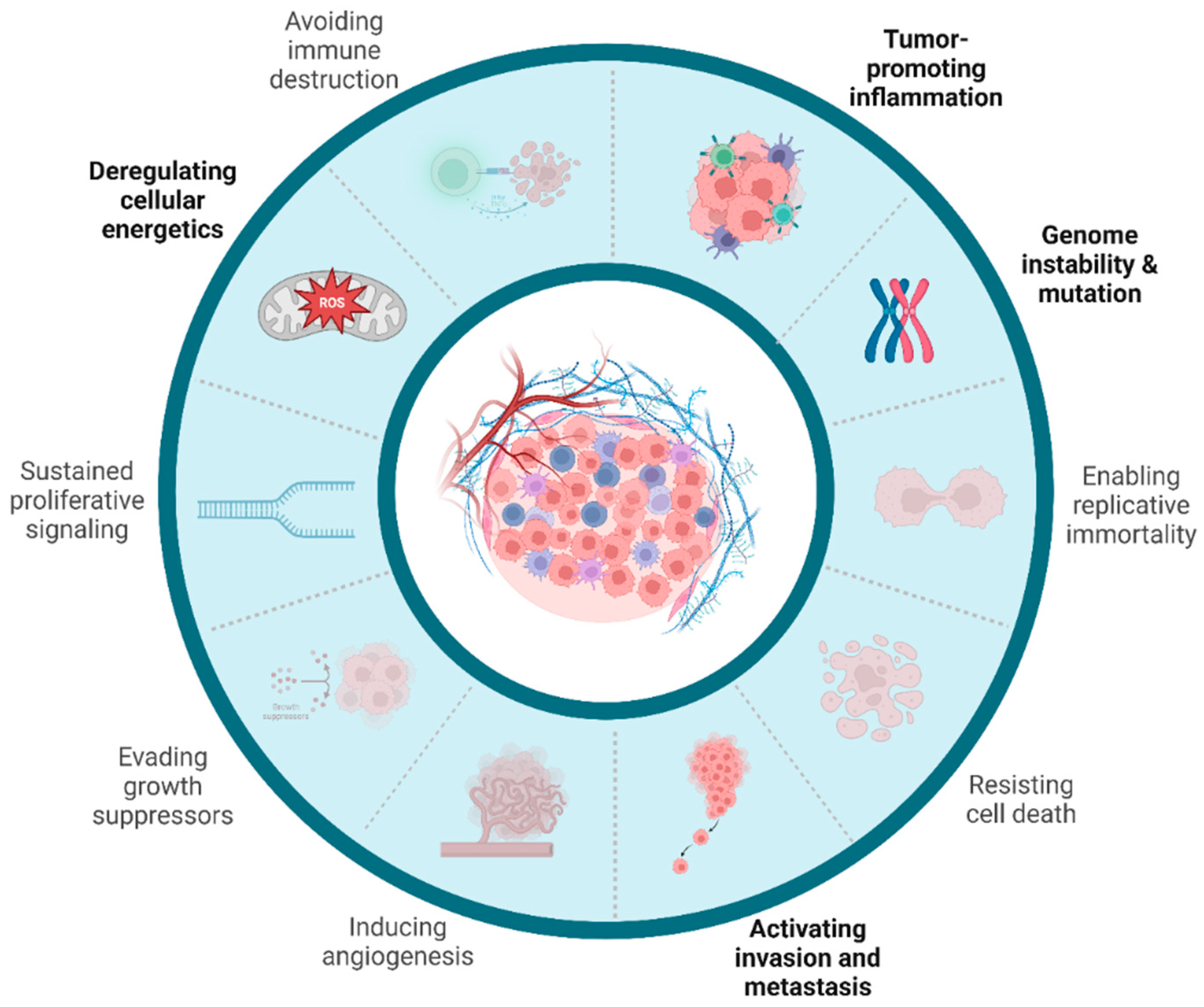

5. MNPs’ Role in Cancer Development and Progression

5.1. Tumor-Promoting Inflammation

5.2. Cancerogenesis Initiation

5.3. Cancerogenesis Promotion

5.4. MNPs’ Presence in Cancer Tissue

6. Discussion

- First, standardization in analytical methods for MNP detection in biological specimens will be essential to achieve reproducible and reliable results, and to provide the basis for building consistent evidence from different scientific groups.

- Studies employing mammalian model should evaluate MNP bioaccumulation in tissues over time, thanks to innovative in vivo techniques, as well as unravel the real genotoxic potential of MNPs. In this regard, human organ-specific models could further elucidate tissue-specific effects, and provide information on risks specific to different routes of exposure.

- Translational research should effortlessly characterize the presence, distribution and abundance of MNPs in normal and cancer tissues, aiming at investigating potential prognostic and molecular implications. In the near future, the integration of advanced analytical techniques, computational tools, and multi-omics approaches could unravel MNPs role as a carcinogen.

- At a more complex level, MNPs could have a range of interactions with fundamental body-wide entities, such as microbiota, systemic immunity, and nervous signals, which have to be further elucidated.

- To date, there is an urgent need of robust epidemiological data evaluating the correlation of MNPs exposure and disease development at a population level. Longitudinal epidemiologic studies should determine the cancer risk for populations at higher probability of MNP exposure, as in industrial and metropolitan areas or in coastal locations. Moreover, epidemiological data would be extremely valuable in order to generate hypotheses in basic science and further elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N. (Nil); Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health. The Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Bristow, K.; Filipović, V.; Lv, J.; He, H. Microplastics in Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Scientometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, R.; Prasad, G.S.; Amin, A.; Malik, M.M.; Ahmad, I.; Abubakr, A.; Borah, S.; Rather, M.A.; Impellitteri, F.; Tabassum, I.; et al. Understanding and Addressing Microplastic Pollution: Impacts, Mitigation, and Future Perspectives. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2024, 266, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Omar, S.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farghali, M.; Yap, P.-S.; Wu, Y.-S.; Nagandran, S.; Batumalaie, K.; et al. Microplastic Sources, Formation, Toxicity and Remediation: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 21, 2129–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S.; Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A.A. Twenty Years of Microplastics Pollution Research—What Have We Learned? Science 2024, 0, eadl2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Allen, S.; Abbasi, S.; Baker, A.; Bergmann, M.; Brahney, J.; Butler, T.; Duce, R.A.; Eckhardt, S.; Evangeliou, N.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in the Marine-Atmosphere Environment. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2022, 3, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; de Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk Assessment of Microplastic Particles. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation Environmental and Health Risks of Microplastic Pollution 2019.

- Krause, S.; Ouellet, V.; Allen, D.; Allen, S.; Moss, K.; Nel, H.A.; Manaseki-Holland, S.; Lynch, I. The Potential of Micro- and Nanoplastics to Exacerbate the Health Impacts and Global Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases. Cell Reports Medicine 2024, 5, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC, List of Classifications. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- SAPEA A Scientific Perspective on Microplastics in Nature and Society: Evidence Review Report (1.1).; SAPEA, 2019; ISBN 978-3-9820301-0-4.

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostle, C.; Thompson, R.C.; Broughton, D.; Gregory, L.; Wootton, M.; Johns, D.G. The Rise in Ocean Plastics Evidenced from a 60-Year Time Series. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; McGivern, A.; Murphy, E.; Jambeck, J.; Leonard, G.H.; Hilleary, M.A.; et al. Predicted Growth in Plastic Waste Exceeds Efforts to Mitigate Plastic Pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageel, H.K.; Harrad, S.; Abdallah, M.A.-E. Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Risk of Microplastics in the Indoor Environment. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2022, 24, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, Courtney; Baker, Joel E; Bamford, Holly A Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris.; 2009.

- Woodall, L.C.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M.; Paterson, G.L.J.; Coppock, R.; Sleight, V.; Calafat, A.; Rogers, A.D.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Thompson, R.C. The Deep Sea Is a Major Sink for Microplastic Debris. R. Soc. open sci. 2014, 1, 140317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Hardesty, B.D.; Van Franeker, J.A.; Eriksen, M.; Siegel, D.; Galgani, F.; Law, K.L. A Global Inventory of Small Floating Plastic Debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lots, F.A.E.; Behrens, P.; Vijver, M.G.; Horton, A.A.; Bosker, T. A Large-Scale Investigation of Microplastic Contamination: Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in European Beach Sediment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2017, 123, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Aldridge, D.C. Microplastics in Freshwater Systems: A Review of the Emerging Threats, Identification of Knowledge Gaps and Prioritisation of Research Needs. Water Research 2015, 75, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Paul Chen, J. Microplastics in Freshwater Systems: A Review on Occurrence, Environmental Effects, and Methods for Microplastics Detection. Water Research 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Park, J.; Md Din, M.F.; Mat Taib, S.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Kumar Yadav, K.; Kamyab, H. Microplastics Pollution in Different Aquatic Environments and Biota: A Review of Recent Studies. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 133, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubris, K.A.V.; Richards, B.K. Synthetic Fibers as an Indicator of Land Application of Sludge. Environmental Pollution 2005, 138, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, M.; Bigalke, M. Microplastics in Swiss Floodplain Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3591–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Gertsen, H.; Peters, P.; Salánki, T.; Geissen, V. A Simple Method for the Extraction and Identification of Light Density Microplastics from Soil. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 616–617, 1056–1065. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.; Gautam, A. A Procedure for Measuring Microplastics Using Pressurized Fluid Extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5774–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Jinjin, C.; Ji, R.; Ma, Y.; Yu, X. Microplastics in Agricultural Soils: Sources, Effects, and Their Fate. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2022, 25, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic Contamination in an Urban Area: A Case Study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Mirande, C.; Mandin, C.; Guerrouache, M.; Langlois, V.; Tassin, B. A First Overview of Textile Fibers, Including Microplastics, in Indoor and Outdoor Environments. Environmental Pollution 2017, 221, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, J.; Wright, S.L.; Dris, R.; Collard, F.; Mandin, C.; Guerrouache, M.; Langlois, V.; Kelly, F.J.; Tassin, B. Microplastics in Air: Are We Breathing It In? Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Wang, R.; He, D. Air Conditioner Filters Become Sinks and Sources of Indoor Microplastics Fibers. Environmental Pollution 2022, 292, 118465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahney, J.; Mahowald, N.; Prank, M.; Cornwell, G.; Klimont, Z.; Matsui, H.; Prather, K.A. Constraining the Atmospheric Limb of the Plastic Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2020719118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, P.; Mondellini, S.; Mauro, S.; Zanellato, M.; Parolini, M.; Sturchio, E. Potential Effects of Environmental and Occupational Exposure to Microplastics: An Overview of Air Contamination. Toxics 2024, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in Freshwaters and Drinking Water: Critical Review and Assessment of Data Quality. Water Research 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) as a Source of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, J.C. Microplastics in Wastewater: State of the Knowledge on Sources, Fate and Solutions. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 129, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wezel, A.P.; Van Den Hurk, F.; Sjerps, R.M.A.; Meijers, E.M.; Roex, E.W.M.; Ter Laak, T.L. Impact of Industrial Waste Water Treatment Plants on Dutch Surface Waters and Drinking Water Sources. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 640–641, 1489–1499. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Dietary and Inhalation Exposure to Nano- and Microplastic Particles and Potential Implications for Human Health. 2022.

- Liu, S.; Junaid, M.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Eco-Corona Formation and Associated Ecotoxicological Impacts of Nanoplastics in the Environment. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 836, 155703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, K.; He, C.; Huang, Y.; Xin, G.; Huang, X. Insights into Eco-Corona Formation and Its Role in the Biological Effects of Nanomaterials from a Molecular Mechanisms Perspective. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 159867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, E.; Benedé, S. Is There Evidence of Health Risks From Exposure to Micro- and Nanoplastics in Foods? Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Katsouli, J.; Marczylo, E.L.; Gant, T.W.; Wright, S.; Serna, J.B. de la The Potential Impacts of Micro-and-Nano Plastics on Various Organ Systems in Humans. eBioMedicine 2024, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensign, L.M.; Cone, R.; Hanes, J. Oral Drug Delivery with Polymeric Nanoparticles: The Gastrointestinal Mucus Barriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2012, 64, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, X.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Z. From Natural Environment to Animal Tissues: A Review of Microplastics(Nanoplastics) Translocation and Hazards Studies. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 855, 158686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.; Tan, J.; Wang, B.; Li, M. The Role of Gut Microbiota in MP/NP-Induced Toxicity. Environmental Pollution 2024, 359, 124742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato-Lourenço, L.F.; Dantas, K.C.; Júnior, G.R.; Paes, V.R.; Ando, R.A.; de Oliveira Freitas, R.; da Costa, O.M.M.M.; Rabelo, R.S.; Soares Bispo, K.C.; Carvalho-Oliveira, R.; et al. Microplastics in the Olfactory Bulb of the Human Brain. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2440018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, P.M.; Twayana, K.S.; Ravanan, P. ; John Thomas; Mukherjee, A. ; Jenkins, D.F.; Chandrasekaran, N. Prospects on the Nano-Plastic Particles Internalization and Induction of Cellular Response in Human Keratinocytes. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 2021, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacorta, A.; Cazorla-Ares, C.; Fuentes-Cebrian, V.; Valido, I.H.; Vela, L.; Carrillo-Navarrete, F.; Morataya-Reyes, M.; Mejia-Carmona, K.; Pastor, S.; Velázquez, A.; et al. Fluorescent Labeling of Micro/Nanoplastics for Biological Applications with a Focus on “true-to-Life" Tracking. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 476, 135134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Wang, D. Cellular Uptake, Transport, and Organelle Response After Exposure to Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Current Knowledge and Perspectives for Environmental and Health Risks. Reviews Env.Contamination (formerly:Residue Reviews) 2022, 260, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinänen, O.; Dayts, E.J.; Rodriguez, C.; Sarrett, S.M.; Brennan, J.M.; Sarparanta, M.; Zeglis, B.M. Harnessing PET to Track Micro- and Nanoplastics in Vivo. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Kang, K.-K.; Sung, S.-E.; Choi, J.-H.; Sung, M.; Shin, C.-H.; Jeon, E.; Kim, D.; Kim, D.; et al. Toxicity and Biodistribution of Fragmented Polypropylene Microplastics in ICR Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas Arranz, J.; Villacorta, A.; Rubio, L.; García-Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez, G.; Llorca, M.; Farre, M.; Ferrer, J.F.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Kinetics and Toxicity of Nanoplastics in Ex Vivo Exposed Human Whole Blood as a Model to Understand Their Impact on Human Health. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 948, 174725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Ehrlich, L.; Henrich, W.; Koeppel, S.; Lomako, I.; Schwabl, P.; Liebmann, B. Detection of Microplastic in Human Placenta and Meconium in a Clinical Setting. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; D’Onofrio, N.; Scisciola, L.; Grotta, R.L.; Frigé, C.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, N.; Gao, X.; Lang, X.; Deng, H.; Bratu, T.M.; Chen, Q.; Stapleton, P.; Yan, B.; Min, W. Rapid Single-Particle Chemical Imaging of Nanoplastics by SRS Microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2300582121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, J.; Xu, G.; Wu, H.; Xie, L.; Liu, J.; Gong, K.; Ruan, X.; Han, J.; Li, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Fast Detection and 3D Imaging of Nanoplastics and Microplastics by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. CR-PHYS-SC 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gowen, A.; Xu, W.; Xu, J. Analysing Micro- and Nanoplastics with Cutting-Edge Infrared Spectroscopy Techniques: A Critical Review. Analytical Methods 2024, 16, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadac-Czapska, K.; Ośko, J.; Knez, E.; Grembecka, M. Microplastics and Oxidative Stress—Current Problems and Prospects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining Roles of Specific Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Cell Biology and Physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. The Emerging Role of Microplastics in Systemic Toxicity: Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Science of The Total Environment 2023, 895, 165076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, M.; Dai, L.; Cao, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y. Polystyrene Nanoplastic Exposure Induces Developmental Toxicity by Activating the Oxidative Stress Response and Base Excision Repair Pathway in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). ACS Omega 2022, 7, 32153–32163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.A.; Rafiee, M.; Khodagholi, F.; Ahmadpour, E.; Amereh, F. Nanoplastics-Induced Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Defense, and Physiological Response in Exposed Wistar Albino Rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 11332–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Liu, M.; Xiong, F.; Xu, K.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Pu, Y. Polystyrene Micro- and Nanoplastics Induce Gastric Toxicity through ROS Mediated Oxidative Stress and P62/Keap1/Nrf2 Pathway. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingappan, K. NF-κB in Oxidative Stress. Current Opinion in Toxicology 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Guo, X. Polystyrene Microplastics Aggravate Inflammatory Damage in Mice with Intestinal Immune Imbalance. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 833, 155198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, C.-B.; Won, E.-J.; Kang, H.-M.; Lee, M.-C.; Hwang, D.-S.; Hwang, U.-K.; Zhou, B.; Souissi, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, J.-S. Microplastic Size-Dependent Toxicity, Oxidative Stress Induction, and p-JNK and p-P38 Activation in the Monogonont Rotifer (Brachionus Koreanus). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 8849–8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.E.; Yi, Y.; Moon, S.; Yoon, H.; Park, Y.S. Impact of Micro- and Nanoplastics on Mitochondria. Metabolites 2022, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.-Y.; Li, H.; Ren, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, F.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, X. Size-Dependent Effects of Polystyrene Nanoplastics on Autophagy Response in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 421, 126770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, K.-F.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Chen, J.-K.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Lin, C.-H. The Nephrotoxic Potential of Polystyrene Microplastics at Realistic Environmental Concentrations. J Hazard Mater 2022, 427, 127871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Ng, C.T.; Zou, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Bay, B.H.; Shen, H.-M.; Ong, C.N. Targeted Metabolomics Reveals Differential Biological Effects of Nanoplastics and nanoZnO in Human Lung Cells. Nanotoxicology 2019, 13, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.W.; Provencher, J.F.; Allison, J.E.; Muzzatti, M.J.; MacMillan, H.A. The Digestive System of a Cricket Pulverizes Polyethylene Microplastics down to the Nanoplastic Scale. Environmental Pollution 2024, 343, 123168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Moos, N.; Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Köhler, A. Uptake and Effects of Microplastics on Cells and Tissue of the Blue Mussel Mytilus Edulis L. after an Experimental Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11327–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A.J.; Funkhouser, W.; Pugh, C.B.; Winters, S.; Stonehuerner, J.G.; Mahar, A.M.; Roggli, V.L. Pulmonary Fibrosis and Ferruginous Bodies Associated with Exposure to Synthetic Fibers. Toxicol Pathol 2006, 34, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D.G.; Kern, E.; Crausman, R.S.; Clapp, R.W. A Retrospective Cohort Study of Lung Cancer Incidence in Nylon Flock Workers, 1998-2008. Int J Occup Environ Health 2011, 17, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studnicka, M.J.; Menzinger, G.; Drlicek, M.; Maruna, H.; Neumann, M.G. Pneumoconiosis and Systemic Sclerosis Following 10 Years of Exposure to Polyvinyl Chloride Dust. Thorax 1995, 50, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atis, S.; Tutluoglu, B.; Levent, E.; Ozturk, C.; Tunaci, A.; Sahin, K.; Saral, A.; Oktay, I.; Kanik, A.; Nemery, B. The Respiratory Effects of Occupational Polypropylene Flock Exposure. Eur Respir J 2005, 25, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasse, G.F.; Melgert, B.N. Microplastic and Plastic Pollution: Impact on Respiratory Disease and Health. Eur Respir Rev 2024, 33, 230226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Q.; Wei, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Polystyrene Microplastics Cause Cardiac Fibrosis by Activating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway and Promoting Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Rats. Environmental Pollution 2020, 265, 115025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Raftis, J.B.; Langrish, J.P.; McLean, S.G.; Samutrtai, P.; Connell, S.P.; Wilson, S.; Vesey, A.T.; Fokkens, P.H.B.; Boere, A.J.F.; et al. Inhaled Nanoparticles Accumulate at Sites of Vascular Disease. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4542–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discovery 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, M.; Iachetta, G.; Tussellino, M.; Carotenuto, R.; Prisco, M.; De Falco, M.; Laforgia, V.; Valiante, S. Polystyrene Nanoparticles Internalization in Human Gastric Adenocarcinoma Cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2016, 31, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, P.; Ouyang, Z.; Jia, H.; Guo, X. The Characteristics of Dissolved Organic Matter Release from UV-Aged Microplastics and Its Cytotoxicity on Human Colonic Adenocarcinoma Cells. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 826, 154177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Li, N.; Yu, J.; Yao, L. Integrated Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Reveal the Mechanism of Polystyrene Nanoplastics Toxicity to Mice. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 284, 116925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Polystyrene Microplastics Induce Hepatotoxicity and Disrupt Lipid Metabolism in the Liver Organoids. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K, L.; Kp, L.; T, S.; S, J.; Z, L.; X, L.; Tf, C.; Jk, F.; M, L.; L, G.; et al. Detrimental Effects of Microplastic Exposure on Normal and Asthmatic Pulmonary Physiology. Journal of hazardous materials 2021, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.J.; Gong, J.E.; Jin, Y.J.; Seo, S.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, D.Y. Inflammatory Response in the Mid Colon of ICR Mice Treated with Polystyrene Microplastics for Two Weeks. Lab Anim Res 2021, 37, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, X.; Sheng, D.; Xu, Z.; Rong, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. Polyethylene Microplastics Affect the Distribution of Gut Microbiota and Inflammation Development in Mice. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xu, M.; He, C.; Wang, H.; Hu, Q. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Potentiate the Development of Hepatic Fibrosis in High Fat Diet Fed Mice. Environmental Toxicology 2022, 37, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lemos, B.; Ren, H. Tissue Accumulation of Microplastics in Mice and Biomarker Responses Suggest Widespread Health Risks of Exposure. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 46687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barguilla, I.; Domenech, J.; Ballesteros, S.; Rubio, L.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Long-Term Exposure to Nanoplastics Alters Molecular and Functional Traits Related to the Carcinogenic Process. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 438, 129470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barguilla, I.; Domenech, J.; Rubio, L.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Nanoplastics and Arsenic Co-Exposures Exacerbate Oncogenic Biomarkers under an In Vitro Long-Term Exposure Scenario. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X. Polystyrene Microplastics Disturb Maternal-Fetal Immune Balance and Cause Reproductive Toxicity in Pregnant Mice. Reproductive Toxicology 2021, 106, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, D.; Liang, X.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Pang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Z.; Kong, D.; et al. Old Dog New Tricks: PLGA Microparticles as an Adjuvant for Insulin Peptide Fragment-Induced Immune Tolerance against Type 1 Diabetes. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2020, 17, 3513–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, P.M.; Saranya, V.; Vijayakumar, S.; Mythili Meera, M.; Ruprekha, S.; Kunal, R.; Pranay, A.; Thomas, J.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Assessment on Interactive Prospectives of Nanoplastics with Plasma Proteins and the Toxicological Impacts of Virgin, Coronated and Environmentally Released-Nanoplastics. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, S.; Domenech, J.; Barguilla, I.; Cortés, C.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Genotoxic and Immunomodulatory Effects in Human White Blood Cells after Ex Vivo Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoplastics. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2020, 7, 3431–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, A.; Vecchiotti, G.; Colafarina, S.; Zarivi, O.; Aloisi, M.; Arrizza, L.; Chichiriccò, G.; Di Carlo, P. In Vitro Genotoxicity of Polystyrene Nanoparticles on the Human Fibroblast Hs27 Cell Line. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, L.; Barguilla, I.; Domenech, J.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Biological Effects, Including Oxidative Stress and Genotoxic Damage, of Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Different Human Hematopoietic Cell Lines. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 398, 122900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Halimu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Internalization and Toxicity: A Preliminary Study of Effects of Nanoplastic Particles on Human Lung Epithelial Cell. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 694, 133794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Gu, W.; Zhang, B.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Toxic Effects of Nanoplastics with Different Sizes and Surface Charges on Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in A549 Cells and the Potential Toxicological Mechanism. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 430, 128485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Zaheer, J.; Choi, E.-J.; Kim, J.S. Enhanced ASGR2 by Microplastic Exposure Leads to Resistance to Therapy in Gastric Cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 3217–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traversa, A.; Mari, E.; Pontecorvi, P.; Gerini, G.; Romano, E.; Megiorni, F.; Amedei, A.; Marchese, C.; Ranieri, D.; Ceccarelli, S. Polyethylene Micro/Nanoplastics Exposure Induces Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Human Bronchial and Alveolar Epithelial Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Weng, Z.; Liang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Xing, H.; et al. Enterohepatic Circulation of Nanoplastics Induced Hyperplasia, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Gallbladder. Nano Today 2024, 57, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, J.L.; Stegmeier, S.J.; Allaart, H.A.; Cheney, R.T.; Zhang, P.J.; Mayer, A.G.; Streck, R.J. Inhaled Cellulosic and Plastic Fibers Found in Human Lung Tissue. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 1998, 7, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, M.; Demirkaya Miloglu, F.; Kilic Baygutalp, N.; Ceylan, O.; Yildirim, S.; Eser, G.; Gul, H.İ. Higher Number of Microplastics in Tumoral Colon Tissues from Patients with Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 21, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhu, J.; Fang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, H. Identification and Analysis of Microplastics in Para-Tumor and Tumor of Human Prostate. eBioMedicine 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinicrope, F.A. Increasing Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, B.; Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.H.; Fu, C.E.; Lim, W.H.; Zeng, R.W.; Yong, J.N.; Koh, J.H.; Syn, N.; Meng, W.; et al. Patterns in Cancer Incidence Among People Younger Than 50 Years in the US, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2328171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).