1. Introduction

Single use, non-degradable plastic waste is a global problem, and the agricultural sector is a major contributor (Brodhagen et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2014). The conventional practice of spreading polyethylene (PE) mulch over the soil surface in ridge-furrow cropping systems is beneficial from a crop productivity and water conservation perspective, but detrimental from a sustainability and environmental pollution perspective (López-López et al., 2015; Memon et al., 2017; Schonbeck, 1999; Schonbeck and Evanylo, 1998; Steinmetz et al., 2016; Summers and Stapleton, 2002; Waggoner et al., 1960). In 2011 in China alone over 1.2 million tons of single use PE mulch was used to cover (mulch) nearly 20 million ha of cropland (Liu et al., 2014). This practice employed worldwide creates a large environmental burden, largely from the deleterious effects of microplastic contamination in agricultural fields (Bläsing and Amelung, 2018; Meng et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), but also from incineration and poor waste disposal practices. Huerta Lwanga et al. (2016, 2017) and others (Tang, 2023; Hoang et al., 2024) have shown the eco-toxic effects of microplastics on soil and terrestrial fauna, with an associated decrease in crop productivity.

With United Nations models predicting an increase in food and water insecurity (Ejaz Qureshi et al., 2013; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016; Roser and Ortiz-Ospina, 2015), it is vital that this practice is not abandoned, but rather modified to use sustainable and environmentally benign technologies. Biodegradable polymers as an alternative to PE are one solution that has been investigated thoroughly (Arcos-Hernandez et al., 2012; González Petit et al., 2015; Harmaen et al., 2015; Jain and Tiwari, 2015; Tabasi and Ajji, 2015; Weng et al., 2011; Wu, 2012, 2014) and an emerging branch to this field is that of sprayable, biodegradable polymers given their simple application and easy customisability (Adhikari et al., 2015; Al-Kalbani et al., 2003; Cline et al., 2011; Fernández et al., 2001; Immirzi et al., 2009; Santagata et al., 2014; Sartore et al., 2018; Schettini et al., 2012, 2005). By harnessing this technology, the benefits of plastic mulching can be realised without the consequences associated with plastic waste.

A new sprayable, biodegradable polyester-urethane-urea (PEUU) mulch developed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) for this purpose, has been shown, at loadings greater than 1 kg/m2, to be effective at conserving soil moisture in several different soils and over a range of environmental conditions, and suppressing weeds, although to date without particular focus on plant (crop) growth and soil nutrient availability.

In order to evaluate the PEUU’s water conservation efficacy when a crop is grown, as well as its effects on plant growth and soil properties, a tomato growth study investigating the impacts of the PEUU mulch on water conservation, plant growth, and soil chemistry was undertaken and results compared with two commercially available plastic mulches, black polyethylene and a transparent oxo-degradable polyethylene. In particular, the objective of the study was to investigate the effect of the sprayable PEUU on plant growth, i.e., to understand whether the applied PEUU impeded plant growth and reproduction (fruiting). To ensure the study provided applicable insights, the trial was carried out in pots in a greenhouse using soil, tomato seeds, and a fertiliser program sourced from an active, commercial tomato farm in Echuca, Victoria, Australia to mimic field soil conditions.

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials

Soil (a red Vertosol) was collected from a well-tilled, commercial tomato farm in Echuca, Australia (36°09'18.9"S 144°38'50.6"E) prior to the growing season at a depth of approximately 20 cm. The soil was air dried and sieved at 2 mm. A representative subsample of the soil was analysed for a range of key soil physicochemical properties as per the ‘Albrecht’ and ‘Reams’ methods by the Environmental Analysis Laboratory at Southern Cross University (see

Table 1).

Noted about this soil by the farmer are its inherently low organic matter (1 to 2%), that it is subject multiple heavy tillage passes before and after tomato crops, and that metham sodium is used in a strip down the centre of the planting bed to stem nematode activity in the crop. Metham (or metam) sodium is a dithiocarbamate soil fumigant with fungicide, nematocide, herbicide and insecticide activity. Li et al. 2017 and others have shown metham sodium can significantly impact soil bacterial community diversity.

Tomato seeds were obtained from Kagome® Australia and grown to seedlings for three weeks in a commercial seed raising mix. The seeds were of the same variety used on the farm from which the soil was obtained.

Mulches used include a commercial black polyethylene (PE); a commercial, transparent, slotted (perforated by repeating slits in the centre of the film) oxo-degradable polyethylene (OPE); and the sprayable, water dispersible, biodegradable PEUU (Adhikari et al., 2019, 2015).

Fertiliser used included urea (analytical grade, Sigma), CaCl2•2H2O (Sigma), anhydrous ZnCl2 (Sigma), commercial Super Phosphate (RICHGRO), Sulphate of Potash (RICHGRO), and Boron (Manutec).

Chemicals used in soil characterisation experiments include KCl (Sigma), N-(1-Napthyl)ethylene diamine dihydrochloride (NED, >98%, Sigma), sulphanilamide (≥99%, Sigma), vanadium(III) chloride (97%, Sigma), potassium nitrate (≥99%, Sigma), hydrochloric acid (Sigma), sodium salicylate (≥99.5%, Sigma), sodium citrate dihydrate (Sigma), sodium tartrate dibasic dihydrate (≥99%, Sigma), sodium nitroprusside (Sigma), ammonium sulphate (≥99%, Sigma), and anhydrous sodium hydroxide (≥98%, Sigma).

2.2. Tomato Growth Trial Conditions and Maintenance

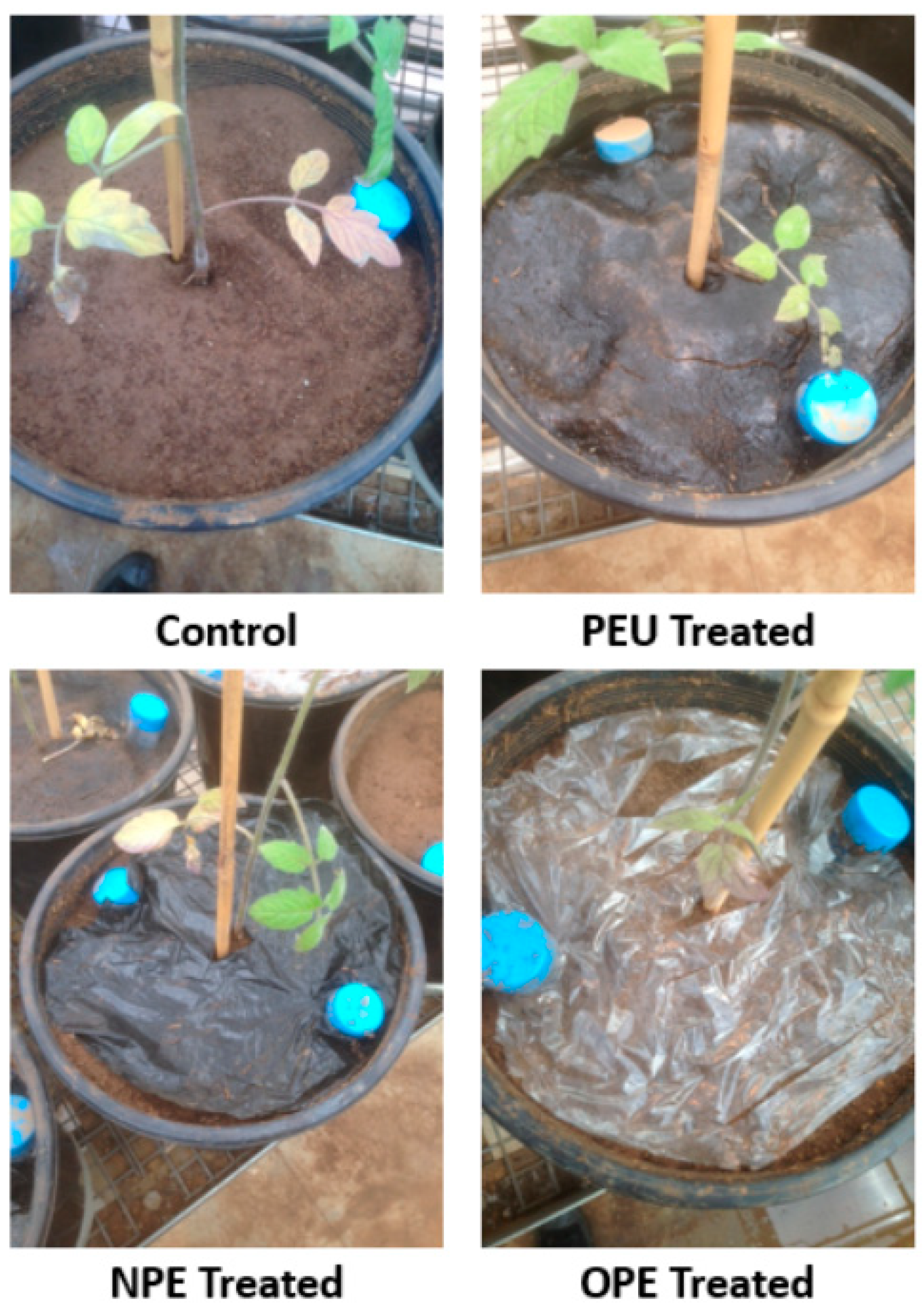

The tomato growth trial consisted of four treatment groups in total, of which three were plastic mulches (PE, OPE, and PEUU) and one was an unmulched control group (C). Treatments were replicated 6 times in 24 cm internal diameter, free-draining polypropylene (PP) pots (one plant per pot) set-up in a temperature-controlled greenhouse with a mean day-night temperature of 26°C and 16°C, respectively (temperature ranged from 25-31°C during the day and 14-18°C at night). Pots were set up underneath full spectrum high intensity discharge (HID) lights set to a 16-8-hour day-night cycle, and the illumination level was ramped from 0-30 klux during the cycle.

Pots were filled with 8 kg of soil and brought to 50% of the soil’s experimentally determined field capacity by adding 2.1 L of tap water. To mimic the typical farm practice, subsurface drip irrigation, two Falcon® 50 mL centrifuge tubes, with their bases removed, were inserted into the soil on either side of the pot. These were capped at all times except when watering the tomato plants.

Tomato seedlings were then transplanted from seed-raising mix into the centre of each pot, one per pot. Finally, mulching treatments were applied to the soil surface by being cut to the appropriate dimensions in the case of the plastic film mulches (PE and OPE), and by being applied as a liquid suspension at a loading of 1 kg m

-2 via syringe (20% solids by weight) in the case of the sprayable, biodegradable polyester-urethane-urea (PEUU). The sprayable PEUU cured into a film over the course of 24 hours.

Figure 1 shows the pots immediately after set-up was completed.

During the growing period, the plants were watered 3-4 times per week, and after each watering event the pots were repositioned randomly. Watering was done by removing the caps from the buried centrifuge tubes, and pouring water directly into the tubes, where it would then run into the soil at a depth of approximately 10 cm. The laid depth of subterranean irrigation tape is dependent on soil type and crop, typically varying from 10 cm to more than 30 cm. At 10 cm, depending on the soil and upward capillary action, the surface soil can become moist. The amount of water added was determined gravimetrically in the following way: the initial total mass of pot, plant, soil and water was known for each pot, and any mass loss was assumed to be due to evaporation. The mass of water lost from each pot between watering events was recorded, in order to assess the water-savings efficacy of the PEUU in comparison to commercial products. Fertiliser was applied once weekly for the first 12 weeks post-transplant according to the fertiliser program used at the commercial farm from which the soil and tomato seeds were obtained (fertiliser program is confidential, a typical tomato farm fertiliser program can be found in the Australian Processing Tomato Grower Report (The Australian Processing Tomato Research Council Inc., 2017)). Fertiliser was applied as an aqueous solution to mimic the sub-surface fertigation. The plants were grown to maturity and harvested 136 days post-transplanting.

At maturity, fruit was picked and characterised, and the remaining plant mass (roots plus shoots) was weighed first as fresh and then as dry weights after 24 hours of oven drying at 105°C. Residual PEUU was characterised by gel permeation chromatography (GPC), and soil from each pot was analysed for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), nitrate, and ammonium.

2.3. Plant Sampling and Characterisation

The growth of the tomato plant was characterised by measuring the plant height periodically over the first 50 days of the study and counting the number of flowers that formed and then the number of fruits that developed. The mature fruit number, and type of visible defects (blossom end-rot, and discolorations) on each fruit were recorded, and as previously stated, at maturity the mass (fresh and dry) of the whole plant excluding the fruit was determined.

The juice of the fruit from each plant was characterised by homogenising whole fruit from each plant in a mortar and pestle, and then measuring the pH and sugar content (Brix). Fruit pH was measured using a pH metre (TPS, WP-80), and fruit Brix was measured by dropping a small amount of the filtered juice onto a refractometer (Livingston, BRIXREF113).

2.4. Soil Sampling and Characterisation

After harvest of the mature plants, the soil was sampled at two depths, 0-2 cm and 2-12 cm. After sampling, the soil was air-dried before being characterised.Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were determined using a 1:5 (m/m) soil: water suspension ratio (Rayment and Lyons, 2011). In brief, 20 g of soil and 100 g of DI water were agitated for 1 hour then allowed to settle for a further 30 minutes. The EC of the supernatant water was first measured using an EC meter (Hach, sensION+ EC5), after which the pH of the supernatant water was measured using a pH metre (TPS, WP-80).

Soil nitrate and ammonium were determined using previously described methods (Baethgen and Alley, 1989; Miranda et al., 2001). In brief, 5 g of soil was agitated in 12.5 mL of 2M KCl for 20 minutes, then centrifuged at 4200 rpm for 10 minutes before being analysed colorimetrically. For soil nitrate determination, an aliquot of the KCl supernatant was mixed with a reagent containing VCl3 and Griess reagent (NED and sulphanilamide in water) and colour was allowed to develop overnight at room temperature, measurement was carried out on a multiplate reader at 540 nm (Multiskan™ GO Microplate Spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific). For soil ammonium determination, an aliquot of the KCl supernatant was added to an aliquot of sodium nitroprusside reagent (including sodium salicylate, sodium citrate, and sodium tartrate) after which an aliquot of alkaline sodium hypochlorite was added. The colour developed for 2 hours before being measured on a multiplate reader at 650 nm (Multiskan™ GO Microplate Spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific). Soil nitrate and soil ammonium quantities were determined using sodium nitrate and ammonium sulphate standards, respectively.

2.5. Polymer Characterisation

Residual PEUU film from was collected at tomato harvest, and then allowed to degrade for a further six months. Collected PEUU specimens were characterised by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) on a Shimadzu system equipped with a CMB-20A controller system, an SIL-20A HT autosampler, an LC-20AT tandem pump system, a DGU-20A degasser unit, a CTO-20AC column oven, an RDI-10A refractive index detector, and 4X Waters Styragel columns (HT2, HT3, HT4, and HT5, each 300 mm × 7.8 mm2, providing an effective molar mass range of 100-4 × 106). Samples were dissolved in dimethylacetamide (DMAc) containing 4.34 g L-1 LiBr, at a concentration of 1-2 mg mL-1. The columns were calibrated with low dispersity poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) standards ranging from 1,500 – 1,500,000 g mol-1. DMAc containing 4.34 g L-1 LiBr was used as an eluent at a 1 mL min-1 flow rate and 80 °C. Mn and Mw were evaluated using Shimadzu LC Solution software

2.6. Data Analysis

All data was analysed using Microsoft Excel 2016, IBM SPSS Statistics 25, or a combination of both. Data clean up (means calculations, outlier testing, and formatting) was carried out in Excel. To determine statistical significance, one-way ANOVA tests were carried out with Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference post-hoc testing in SPSS. Significance level was set at α < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Water Conservation Efficacy

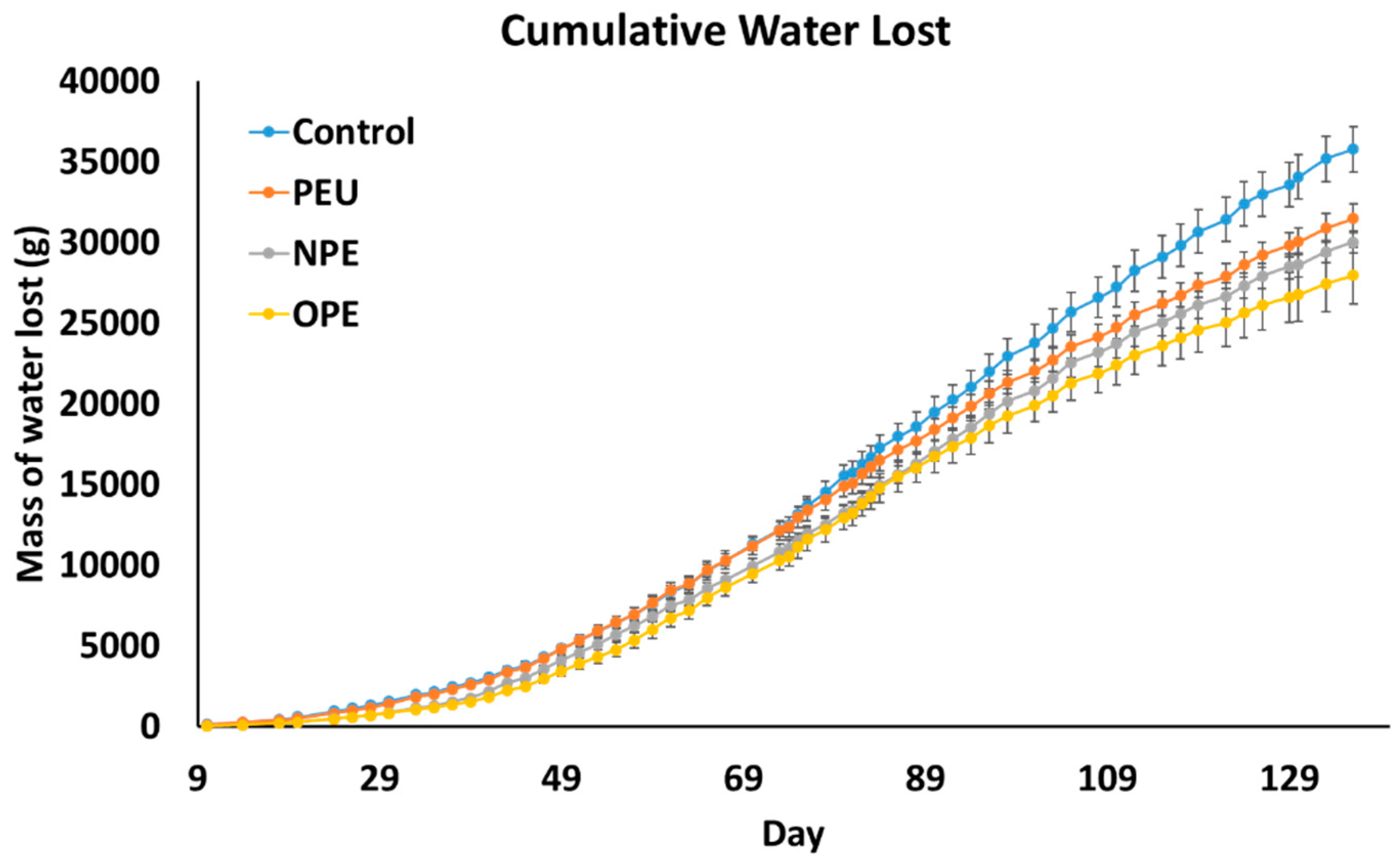

Water loss was determined gravimetrically at each watering event.

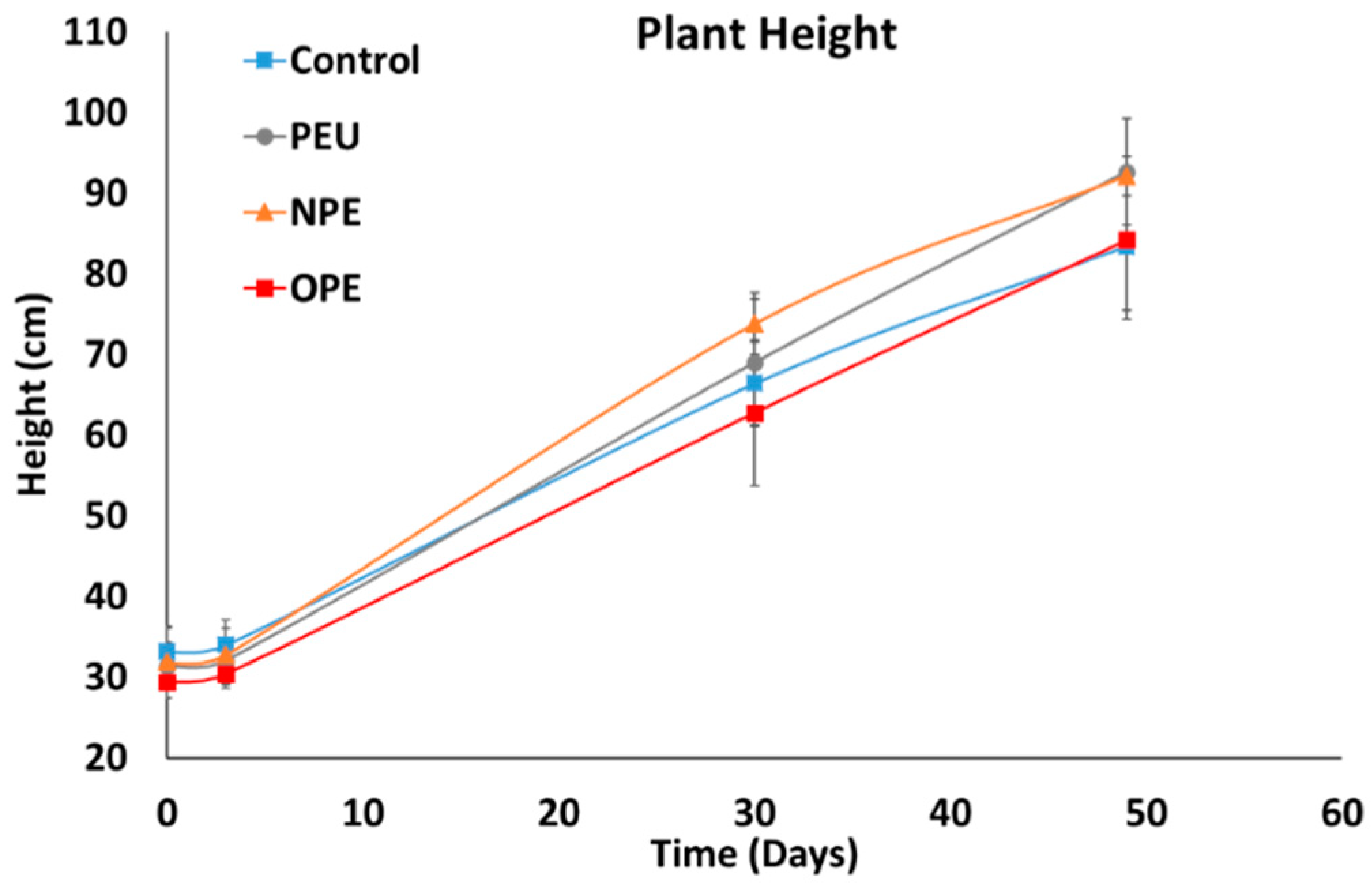

Figure 2 shows the mass of water lost on average from each mulching treatment over the duration of the 136-day study. As expected, unmulched control pots lost the most water, a total of 35.8 ± 3.4 kg, over the study duration compared to 31.5 ± 2.1 kg, 30.0 ± 1.7 kg, and 28.0 ± 4.3 kg for the PEUU, NPE and OPE treatments, respectively. There was no significant difference in water loss between the PEUU mulched and NPE mulched pots, and OPE mulched pots lost the least water. The OPE mulch was slotted, so this finding was unexpected. The OPE plants also initially grew slower (see Figure 4), which possibly was caused by cooler soil temperature associated with non-pigmented mulch, which may have reflected heat causing the soil to remain cooler, thus slowing tomato seed germination and seedling growth rate.

3.2. Soil Analysis

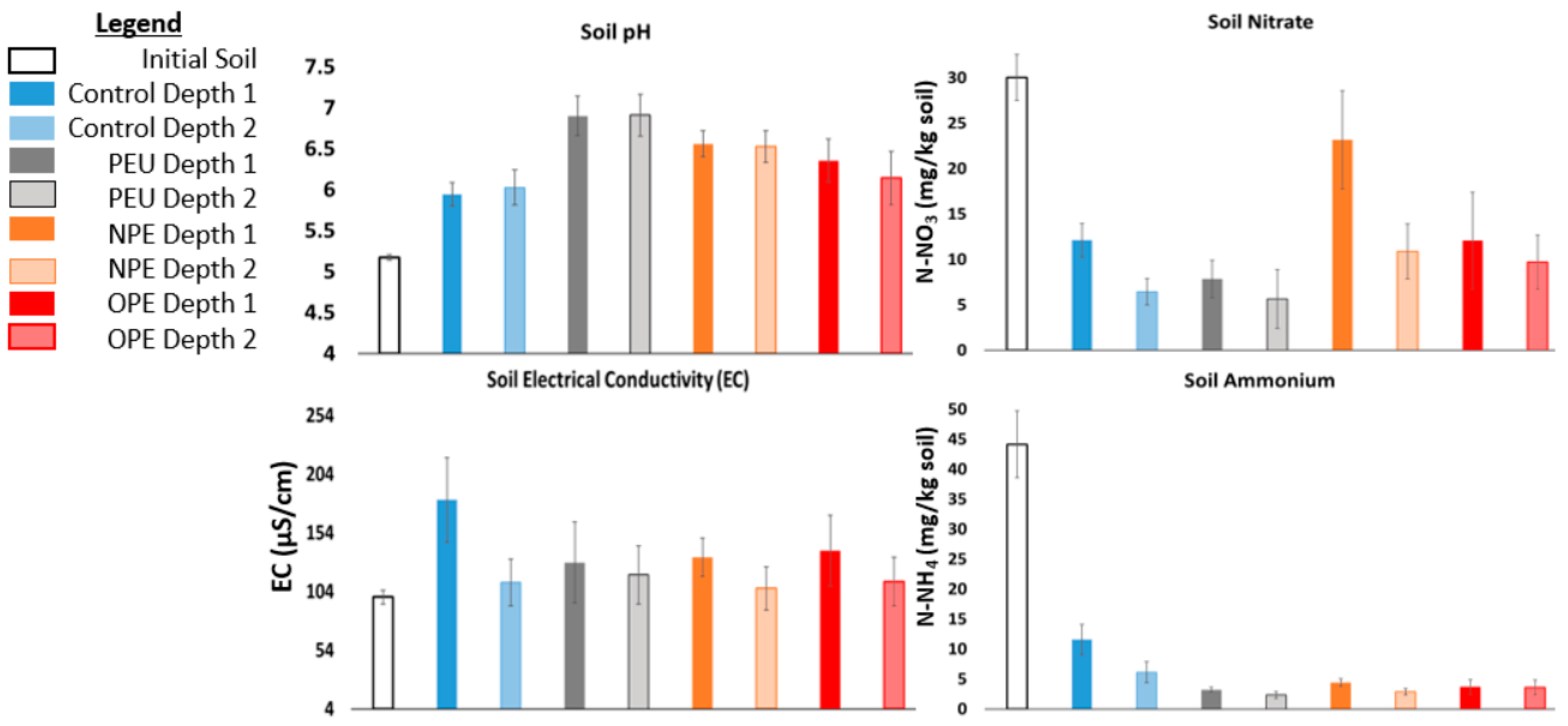

Soil from each pot was analysed at two depths (0-2 cm and 2-10 cm) for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), nitrate, and ammonium (

Figure 3). These are typically measured characteristics to understand soil health. Quantifying soil nitrate and ammonium was of particular interest because the PEUU material contained N (in both the repeating carbamate and urea functional groups) and it would have been interesting if that N ended up in the soil in an inorganic form, easily accessible to plants.

There was no change in soil salinity (as measured by EC) in any of the mulching treatments compared to the salinity of the initial soil. Soil pH rose significantly for all treatment groups, including the control, the likely cause of this was the fertiliser program, which was slightly alkaline (pH > 8) due to one highly alkaline component (pH > 11 when in solution). No differences based on sampling depth were observed. Both soil nitrate and soil ammonium decreased significantly from the initial conditions in all treatments, which was expected as the tomato plants take up and use both chemical forms of nitrogen. If the PEUU did act as a source for inorganic N, the analysis here did not reveal any differences. Further study with under a simpler system would be needed to determine whether no inorganic N is released from the PEUU, or if some inorganic N is released and rapidly assimilated by any plants present. Across the mulching treatments, higher levels of ammonium and nitrate were observed in the soil sampled nearest the surface. This finding is intuitive as the root density is low at the soil surface (less opportunity for inorganic N to be taken up by the plants), and due to the watering method used (sub surface), there would be little opportunity for these chemicals to leach down the soil profile as they would do with above ground irrigation methods. This trend was common in all treatment types although none of the differences between treatments were statistically significant. From a soil physicochemical perspective, the PEUU mulch performed similarly to conventional, commercially available plastic mulches.

3.3. Plant Growth Analysis

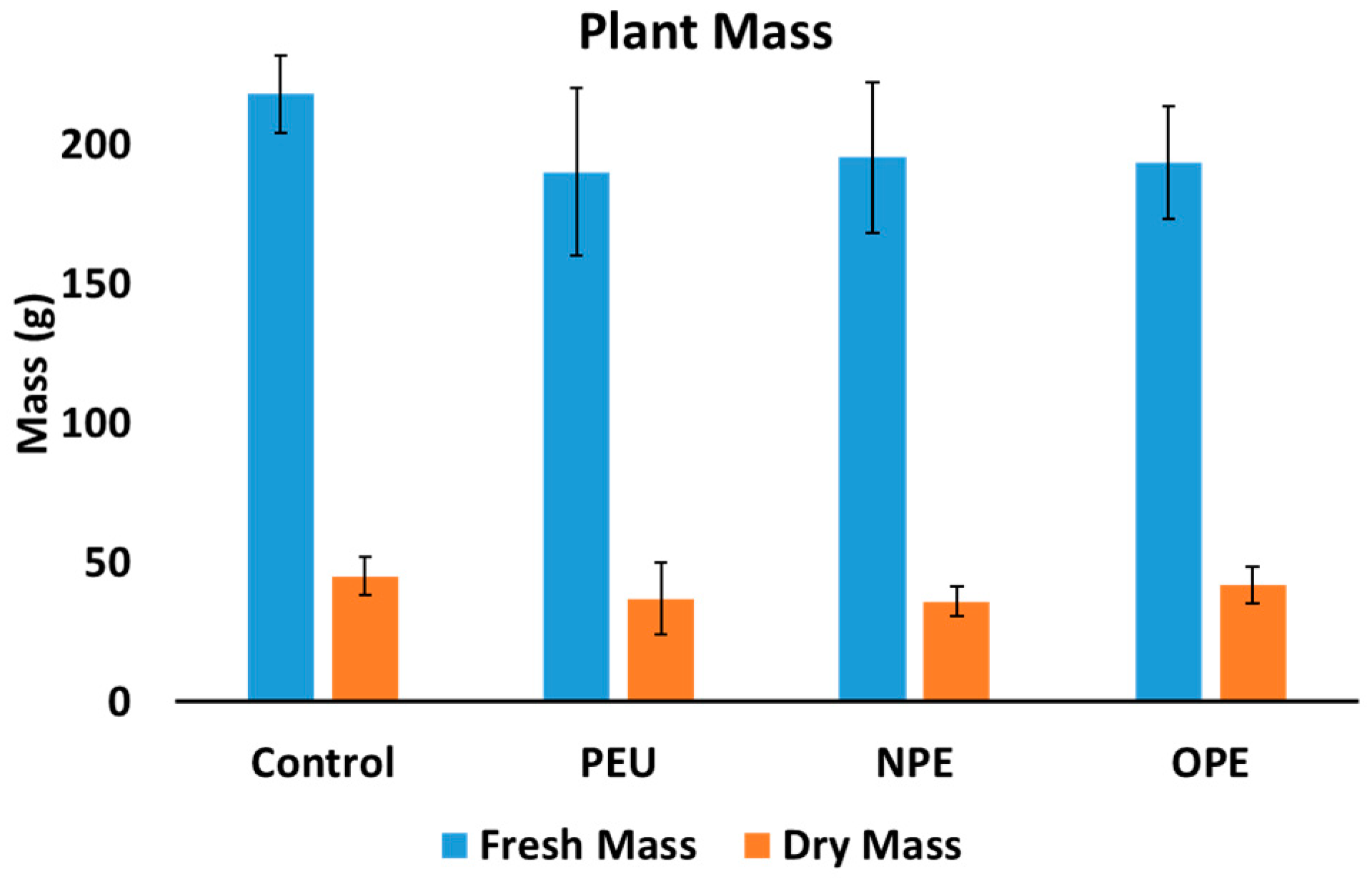

Growth of the tomato plants was monitored by measuring their height periodically over the first 50 days of the trial (

Figure 4), and by measuring their wet and dry mass at harvest. Over the first 50 days the plants mulched with the sprayable PEUU or NPE showed increased growth than those not mulched, or mulched with OPE, however these differences were not statistically significant.

In terms of total plant mass, there was very little variation in wet or dry mass between treatment groups. Interestingly the plants grown in unmulched conditions had the largest average wet mass, but this was not statistically significant, and after oven drying the difference in masses between treatment groups was negligible. This data gives some preliminary evidence that the sprayable PEUU does not create any adverse impacts on plant growth.

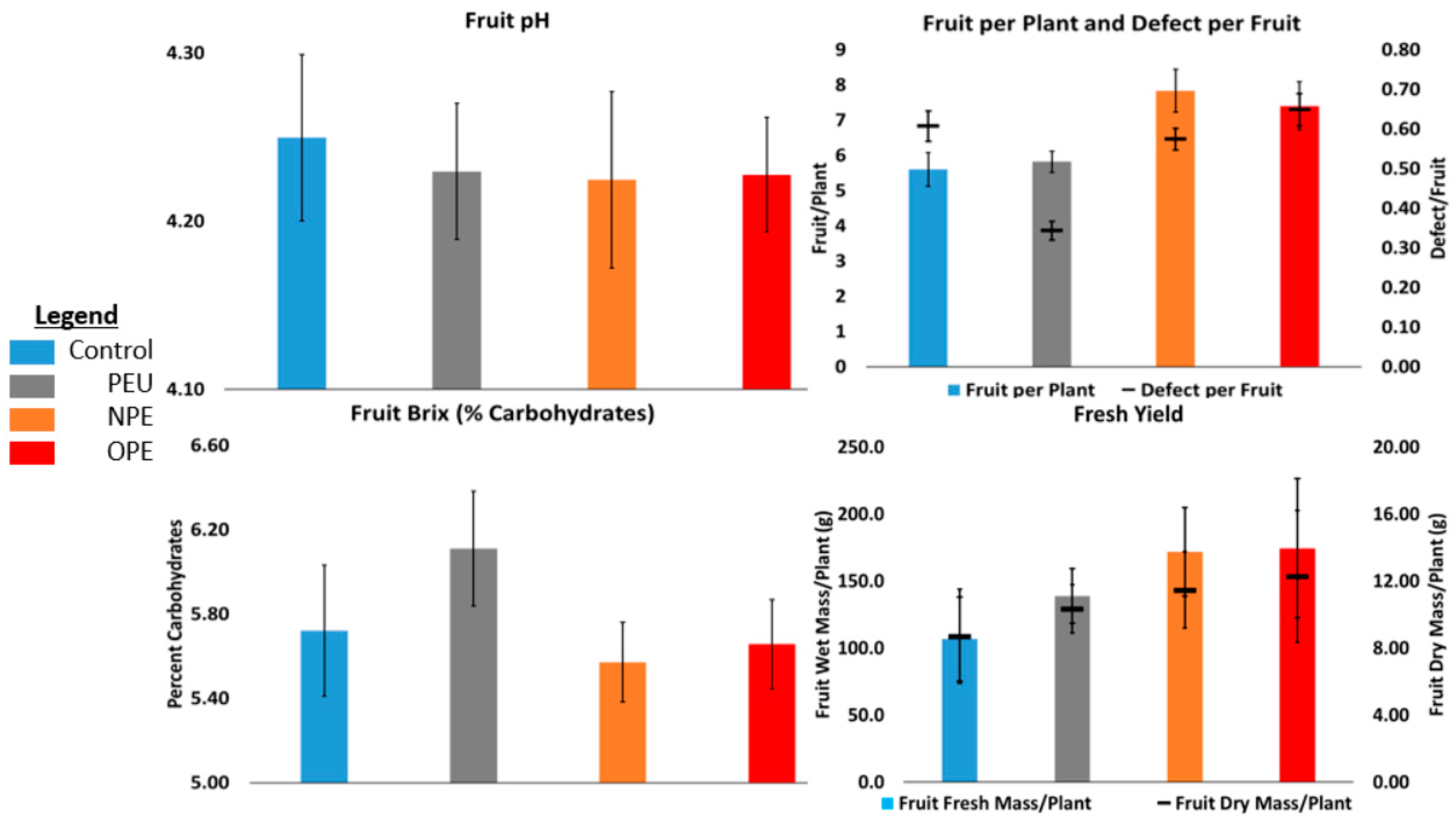

Fruit Brix, fruit pH, and fruit defects were measured because these are important parameters for both tomato growers and tomato processors (

Figure 6). There were no statistically significant differences in any measured fruit characteristic between treatment groups, which contradicts much of the literature that shows that plastic mulching increases crop yield (López-López

et al., 2015; Memon

et al., 2017). These findings are likely evidence of a limitation of this study, or greenhouse pot trials in general; perhaps using larger pots or increasing the replication number would have revealed statistically significant trends, and allowed for increased fruit growth. In any case, this can be taken as further preliminary evidence that the application of the sprayable PEUU does not cause large, detrimental effects to plant growth, but further study is necessary to determine if there truly are no adverse effects.

The large number of defects per fruit (ranging from 0.4 - 0.65 defects per fruit) is noteworthy. The preponderance of fruit defects were blossom-end rot (BER), which is caused in part by a calcium deficiency (Adams and Ho, 1993), although the influence of favourable or unfavourable growing conditions on the development of BER is still poorly understood (Saure, 2001). Given that the growth conditions used in this study (soil, tomato cultivar, fertiliser program) were identical to those used in an active tomato farm, this large incidence of BER indicates that a large-scale field trial is necessary to provide optimal growing conditions for the tomatoes.

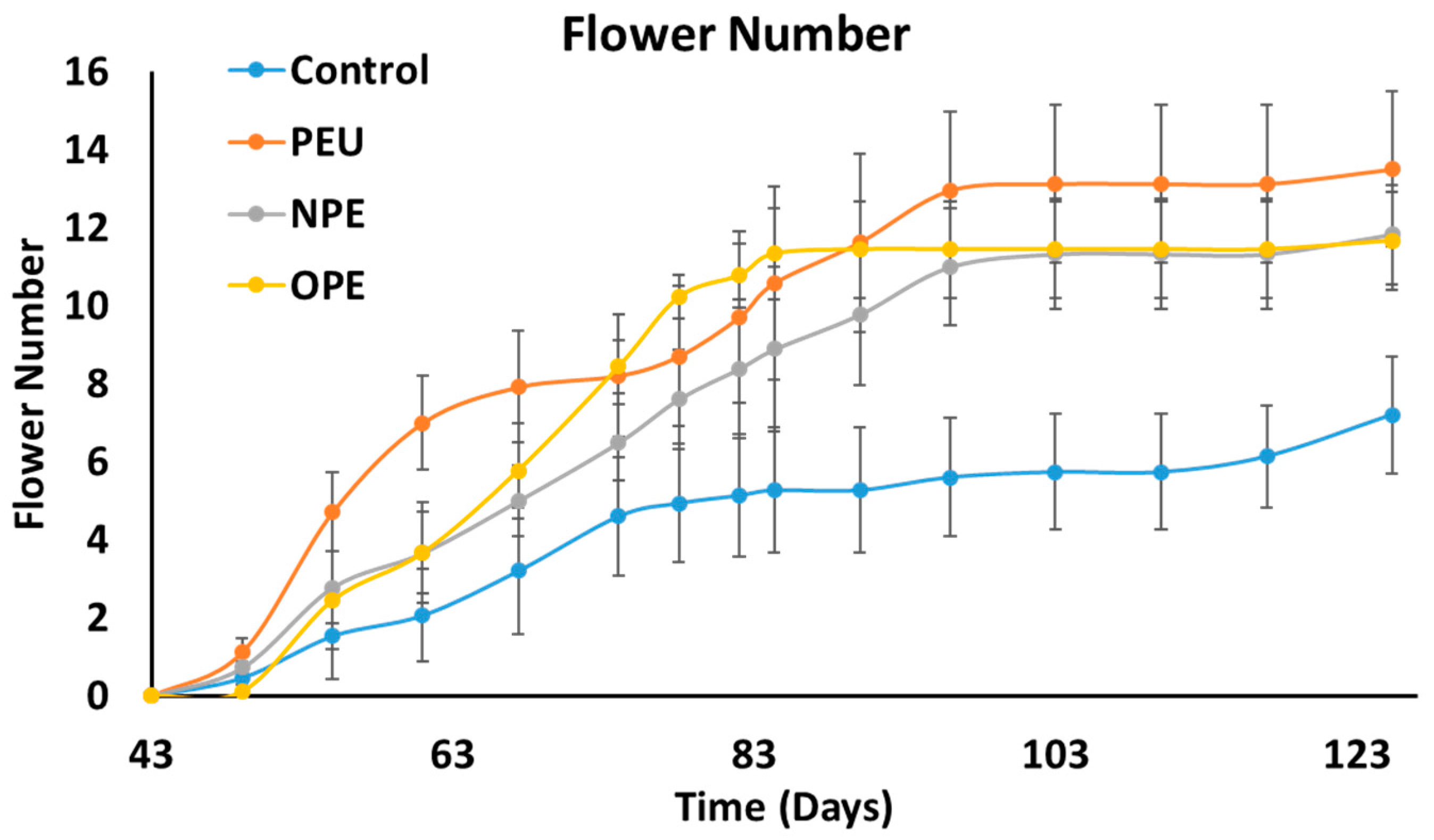

Tracking the number of flowers per tomato plant over time is another way to gain an understanding of how different treatments affect plant health.

Figure 7 displays the average number of flowers per plant per treatment group from Day 43 through to harvest. Each mulching treatment increased the number of flowers per plant compared to no mulch, but the only statistically significant increase compared to control was the sprayable PEUU mulched plants. However, both OPE and NPE mulched plants were statistically higher than control at the α < 0.10 level.

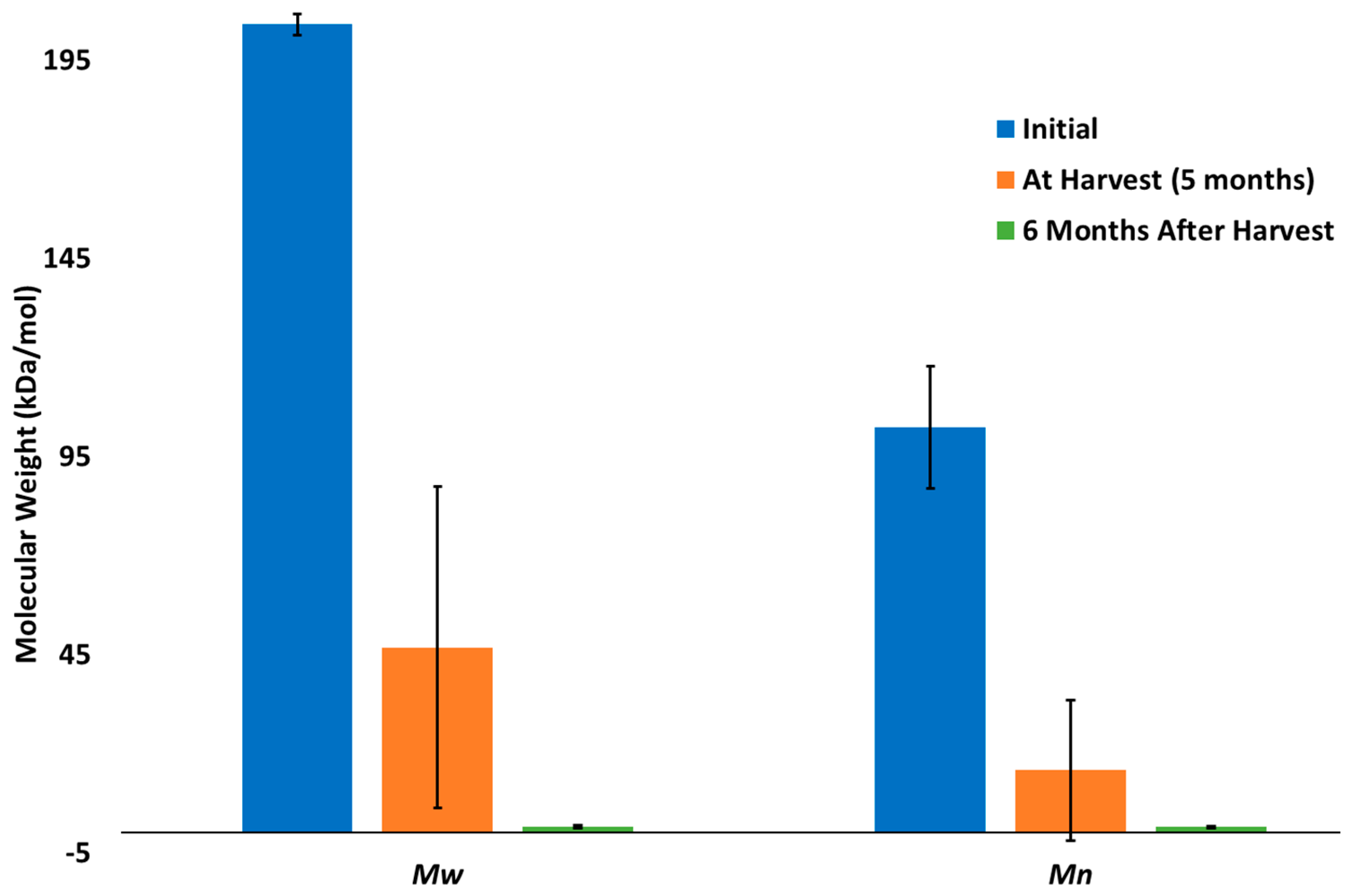

3.4. Polymer Degradation

The PEUU degraded extensively over the course of the growing period and a further six months, as measured by GPC (

Figure 8).

The large error in molecular weight observed at harvest (orange bars,

Figure 8) is due to some film applications degrading nearly completely (i.e.

Mw < 1500 Da) and some films remaining more or less intact although still degraded significantly (

Mw between 30-90kDa). After a further 6 months of on-soil degradation, only three pots had residual PEUU to be collected and characterised by GPC. This data helps demonstrate that PEUU is effective at conserving soil moisture despite degrading extensively while being used.

4. Conclusions

The effects of two commercial plastic mulches and a novel, sprayable biodegradable polyester-urethane-urea (PEUU) mulch on certain soil physicochemical properties, water conservation, and tomato plant growth were investigated. Enhanced water savings were observed in plants treated with mulch of any kind, with no differences in the water savings between mulching treatments. The PEUU caused no negative impacts on plant growth measurements nor on any of the measured fruit characteristic, while degrading significantly over the course of the tomato plant growth period.

The limitations of pot trials are evident in the data presented here. There was no enhanced crop yield for plants grown in mulched soil, which there ought to have been, and there was a high incidence of fruit defects in all treatment groups. However, more flowers formed by plants that were mulched, with an associated higher fruit yield. These data further highlight that a study conducted in larger pots or in the field likely would have produced statistically significant results.

This study did demonstrate that sprayable biodegradable polymers can perform similarly to conventional non-degradable plastic mulches without adverse effects on soil or plant health, and serves as a starting point for further study. This work should be followed up with a field trial conducted under commercial growth conditions to validate inconclusive findings and confirm the technology’s performance under real field conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K.B, R.A; A.F.P; K.S. Methodology, R.A; A.F.P; C.K.B.; K.L Investigation, C.K.B; Writing—original draft, C.K.B; Writing—review & editing, R.A; K. S; S.G.; Funding acquisition, C.K.B; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Monash Graduate Scholarship and Monash International Postgraduate Research Scholarship. It was also supported by funding from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, P., Ho, L.C.Effects of environment on the uptake and distribution of calcium in tomato and on the incidence of blossom-end rot. Plant Soil. 1993, 154, 127–132.

- Adhikari, R., Casey, P., Bristow, K.L., Freischmidt, G., Hornbuckle, J., 2015. Sprayable Polymer Membrane for Agriculture. WO 2015/184490 Al.

- Adhikari, R., Mingtarja, H., Freischmidt, G., Bristow, K.L., Casey, P.S., Johnston, P., Sangwan, P.Effect of viscosity modifiers on soil wicking and physico-mechanical properties of a polyurethane based sprayable biodegradable polymer membrane. Agric. Water Manag. 222, 346–353. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kalbani, M.S., Cookson, P., Rahman, H.A.Uses of Hydrophobic Siloxane Polymer (Guilspare®) for Soil Water Management Application in the Sultanate of Oman. Water Int. 2003, 28, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Hernandez, M. V., Laycock, B., Pratt, S., Donose, B.C., Nikolič, M.A.L., Luckman, P., Werker, A., Lant, P.A.Biodegradation in a soil environment of activated sludge derived polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHBV). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2301–2312. [CrossRef]

- Baethgen, W.E., Alley, M.M. A manual colorimetric procedure for measuring ammonium nitrogen in soil and plant kjeldahl digests. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1989, 20, 961–969. [CrossRef]

- Bläsing, M., Amelung, W.. Plastics in soil: Analytical methods and possible sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 422–435. [CrossRef]

- Brodhagen, M., Goldberger, J.R., Hayes, D.G., Inglis, D.A., Marsh, T.L., Miles, C.. Policy considerations for limiting unintended residual plastic in agricultural soils. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2017, 69, 81–84. [CrossRef]

- Cline, J., Neilsen, G., Hogue, E., Kuchta, S., Neilsen, D. Spray-on-mulch technology for intensively grown irrigated apple orchards: Influence on tree establishment, early yields, and soil physical properties. Horttechnology. 2011, 21, 398–411.

- Ejaz Qureshi, M., Hanjra, M.A., Ward, J., 2013. Impact of water scarcity in Australia on global food security in an era of climate change. Food Policy.2013, 38, 136–145. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.E., Moreno, F., Murillo, J.M., Cuevas, M. V., Kohler, F.Evaluating the effectiveness of a hydrophobic polymer for conserving water and reducing weed infection in a sandy loam soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2001, 51, 29–51. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The State of Food and Agriculture, Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security. 2016, ISBN: 978-92-5-107671-2 I.

- González Petit, M., Correa, Z., Sabino, M.A.Degradation of a Polycaprolactone/Eggshell Biocomposite in a Bioreactor. J. Polym. Environ. 2015, 23, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Harmaen, A.S., Khalina, A., Azowa, I., Hassan, M.A., Tarmian, A.Thermal and Biodegradation Properties of Poly(lactic acid)/Fertilizer/Oil Palm Fibers Blends Biocomposites Ahmad. Polym. Compos. 2015, 576–583.

- Hoang, V. H., Nguyen, M. K., Hoang, T. D., Ha, M. C., Huyen, N. T. T., Hoang Bui, V. K., Pham, M. T., Nguyen, C. M., Chang, S. W. and Nguyen, D. D.Sources, environmental fate, and impacts of microplastic contamination in agricultural soils: A comprehensive review. Science of the Total Environment. 2024, 950, 175276, . [CrossRef]

- Huerta Lwanga, E., Gertsen, H., Gooren, H., Peters, P., Salanki, T., van der Ploeg, M., Besseling, E., Koelmans, A.A., Geissen, V.. Incorporation of microplastics from litter into burrows of Lumbricus terrestris. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Huerta Lwanga, E., Gertsen, H., Gooren, H., Peters, P., Salanki, T., Van Der Ploeg, M., Besseling, E., Koelmans, A.A., Geissen, V.. Microplastics in the Terrestrial Ecosystem: Implications for Lumbricus terrestris (Oligochaeta, Lumbricidae). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2685–2691. [CrossRef]

- Immirzi, B., Santagata, G., Vox, G., Schettini, E.Preparation, characterisation and field-testing of a biodegradable sodium alginate-based spray mulch. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 102, 461–472. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Tiwari, A.Biosynthesis of planet friendly bioplastics using renewable carbon source. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2015, 13, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Huang, B., Wang, Q., Li, Y., Fang, W., Han, D., Yan, D., Guo, M. and Cao, A.. Effects of fumigation with metam-sodium on soil microbial biomass, respiration, nitrogen transformation, bacterial community diversity and genes encoding key enzymes involved in nitrogen cycling, Science of The Total Environment, 2017, 598, 1027-1036, ISSN 0048-9697, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.K., He, W.Q., Yan, C.R.. “White revolution” to “white pollution” - Agricultural plastic film mulch in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- López-López, R., Inzunza-Ibarra, M.A., Sánchez-Cohen, I., Fierro-Álvarez, A., Sifuentes-Ibarra, E.. Water use efficiency and productivity of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) based on two transplanting dates. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 71, 885–891. [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.S., Jun, Z., Jun, G., Ullah, F., Hassan, M., Ara, S., Changying, J.7. Comprehensive review for the effects of ridge furrow plastic mulching on crop yield and water use efficiency under different crops. Int. Agric. Eng. J. 2017, 26, 58–67.

- Meng, K., Ren, W., Teng, Y., Wang, B., Han, Y., Christie, P., Luo, Y.. Application of biodegradable seedling trays in paddy fields: Impacts on the microbial community. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 750–759. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.M., Espey, M.G., Wink, D.A.. A Rapid, Simple Spectrophotometric Method for Simultaneous Detection of Nitrate and Nitrite. Nitric Oxide - Biol. Chem. 2001, 5, 62–71. [CrossRef]

- Rayment, G.E., Lyons, D.J.. 4A1 pH of 1:5 soil/water suspension, in: Soil Chemical Methods - Australasia.2011, pp. 19–39.

- Roser, M., Ortiz-Ospina, E.. World Population Growth [WWW Document]. Our World Data. 2015, URL https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth/.

- Santagata, G., Malinconico, M., Immirzi, B., Schettini, E., Mugnozza, G.S., Vox, G.An overview of biodegradable films and spray coatings as sustainable alternative to oil-based mulching films. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1037, 921–928. [CrossRef]

- Sartore, L., Schettini, E., de Palma, L., Brunetti, G., Cocozza, C., Vox, G.. Effect of hydrolyzed protein-based mulching coatings on the soil properties and productivity in a tunnel greenhouse crop system. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1221–1229. [CrossRef]

- Saure, M. C.. Blossom-end rot of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) — a calcium- or a stress-related disorder? Scientia Horticulturae. 2001, 90, 3–4, 193-208, ISSN 0304-4238, . [CrossRef]

- Schettini, E., Sartore, L., Barbaglio, M., Vox, G.. Hydrolyzed protein based materials for biodegradable spray mulching coatings. Acta Hortic. 2012, 952, 359–366. [CrossRef]

- Schettini, E., Vox, G., Malinconico, M., Immirzi, B., Santagata, G.. Physical Properties of Innovative Biodegradable Spray Coating for Soil Mulching in Greenhouse Cultivation. Acta Hortic. 2005, 725–732. [CrossRef]

- Schonbeck, M.W.. Weed Suppression and Labor Costs Associated with Organic, Plastic, and Paper Mulches in Small-Scale Vegetable Production. J. Sustain. Agric. 1999, 13, 13–33. [CrossRef]

- Schonbeck, M.W., Evanylo, G.K.. Effects of Mulches on Soil Properties and Tomato Production II. Plant-Available Nitrogen, Organic Matter Input, and Tilth-Related Properties. J. Sustain. Agric. 1998, 13, 83–100. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Z., Wollmann, C., Schaefer, M., Buchmann, C., David, J., Troger, J., Munoz, K., Fror, O., Schaumann, G.E.. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 690–705. [CrossRef]

- Summers, C.G., Stapleton, J.J.. Use of UV reflective mulch to delay the colonization and reduce the severity of Bemisia argentifolii (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) infestations in cucurbits. Crop Prot. 2002, 21, 921–928. [CrossRef]

- Tabasi, R.Y., Ajji, A.5. Selective degradation of biodegradable blends in simulated laboratory composting. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 120, 435–442. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. H. D.. Microplastics in agricultural soils in China: Sources, impacts and solutions. Environmental Pollution. 2023, 322, 121235 . [CrossRef]

- The Australian Processing Tomato Research Council Inc., Australian Processing Tomato Grower, 2017.

- Waggoner, P.E., Miller, P.M., De Roo, H.C.. Plastic Mulching Principles and Benefits. Connect. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1960.

- Weng, Y.X., Wang, X.L., Wang, Y.Z. Biodegradation behavior of PHAs with different chemical structures under controlled composting conditions. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 372–380. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-S.2. Preparation, Characterization, and Biodegradability of Renewable Resource-Based Composites from recycled polylactide bioplastic and sisal fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 347–455. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.Preparation and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Bioplastic-Based Green Renewable Composites from Rice Husk. J. Polym. Environ. 2014, 22, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Zhao, Y., Qin, X., Jia, W., Chai, L., Huang, M., Huang, Y. Microplastics from mulching film is a distinct habitat for bacteria in farmland soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 470–478. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).