1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information

The psychological and physical pressure brought on by unstable finances and the inability to fulfill financial commitments is known as financial stress. [

1] Stress of this kind can be brought on by a number of things, including debt, unemployment, unforeseen costs, or insufficient money [

2]. It is typified by ongoing concern and anxiety over money issues, which can have a negative impact on a person's general quality of life [

3]. The idea of physiological well-being includes the preservation of physical health and vitality as well as the appropriate operation of the body's systems and organs [

4]. Conversely, psychological well-being pertains to several facets of mental health, such as emotional stability, cognitive abilities, and the lack of mental illnesses like anxiety and depression [

5].

A person's cardiovascular health, immune system performance, metabolic health, and sleep quality are all aspects of their physiological well-being [

6]. Aspects like mental health, cognitive function, behavioral responses, and social interactions are all part of psychological well-being [

5]. Overall health and quality of life depend heavily on both physiological and psychological well-being, which are intricately linked [

7]. Because it affects these two areas, financial stress can set off a chain reaction of negative health effects that call for in-depth knowledge and practical solutions [

8]. For instance, psychological stress can worsen physical symptoms, starting a vicious cycle of health decline, while physiological stress reactions might set off inflammatory processes that affect mental health [

9].

1.2. Importance of the Study

In the current socioeconomic environment, which is characterized by pervasive financial instability brought on by economic downturns, job insecurity, and growing living expenses, this study is extremely pertinent. For many, the COVID-19 pandemic has made financial difficulties worse, therefore it's critical to comprehend how financial stress affects success and health [

10]. Since a large percentage of the workforce is unemployed or has reduced income, the pandemic has brought attention to how vulnerable many communities are to financial stress, which in turn has increased levels of stress and anxiety [

11]. Knowing how financial stress affects success and health adds to the body of knowledge by offering a comprehensive perspective that incorporates research from a variety of fields, including economics, psychology, and medicine.

This research attempts to close current knowledge gaps and offer a more comprehensive understanding of how financial difficulties impact success and health by examining the connection between financial stress and well-being. Policymakers and healthcare professionals must be informed by this research about the necessity of integrated support systems that handle both financial and health-related concerns. Additionally, it aims to draw attention to how crucial early intervention and preventive measures are in reducing the negative impacts of financial stress on achievement and health, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes and a higher standard of living.

1.3. Objectives and Research Questions

This study aims to investigate the relationship between general health and success

Financial stress

Pinpoint specific physiological, psychological, and success implications, and suggest practical mitigation techniques

The study seeks to provide a thorough understanding of the problem and offer workable solutions to lessen the detrimental effects of financial stress by addressing these questions. Comprehending these associations is essential for formulating focused actions that can enhance health and achievement results for individuals experiencing financial stress.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Lazarus and Folkman's Transactional Model of Stress and Coping offers a fundamental framework for comprehending how people perceive and react to financial stress [

12]. This paradigm proposes that stress results from an individual's engagement with their environment, in which they assess the stressor and their capacity for coping [

12]. This model highlights that stress is a process that incorporates cognitive appraisal and coping processes rather than just a reaction to a stimulus [

13]. It emphasizes the significance of perception and individual variations in stress reactions, implying that coping mechanisms might effectively mitigate financial stress. This approach is especially useful for comprehending how different people may experience different levels of financial stress depending on their social and personal resources.

In addition to the Transactional Model, George Engel's Biopsychosocial model of health views health as a result of social, psychological, and biological elements. This model emphasizes how complicated health and success outcomes can be, and how important it is to take into account a variety of factors while researching the impacts of financial stress [

14]. The effects of financial stress on an individual, for instance, are influenced by a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors, including mental health and coping mechanisms, genetics, and socioeconomic level [

14]. This holistic approach, which incorporates the interaction of several factors that affect health and success results, is essential for comprehending the all-encompassing consequences of financial stress on well-being and achievement

2.2. Previous Studies on Financial Stress

Research has long shown the harmful impacts of financial stress on health, with the majority of early studies concentrating on the connection between financial difficulty and mental health problems. Studies conducted during the Great Depression, for example, demonstrated the significant psychological effects of financial difficulty, such as elevated rates of anxiety and sadness [

15]. These preliminary results paved the way for more research into the wider effects of financial stress on health. Research on the physiological effects of financial stress grew during the ensuing decades, establishing links to various health issues, including cardiovascular disorders.

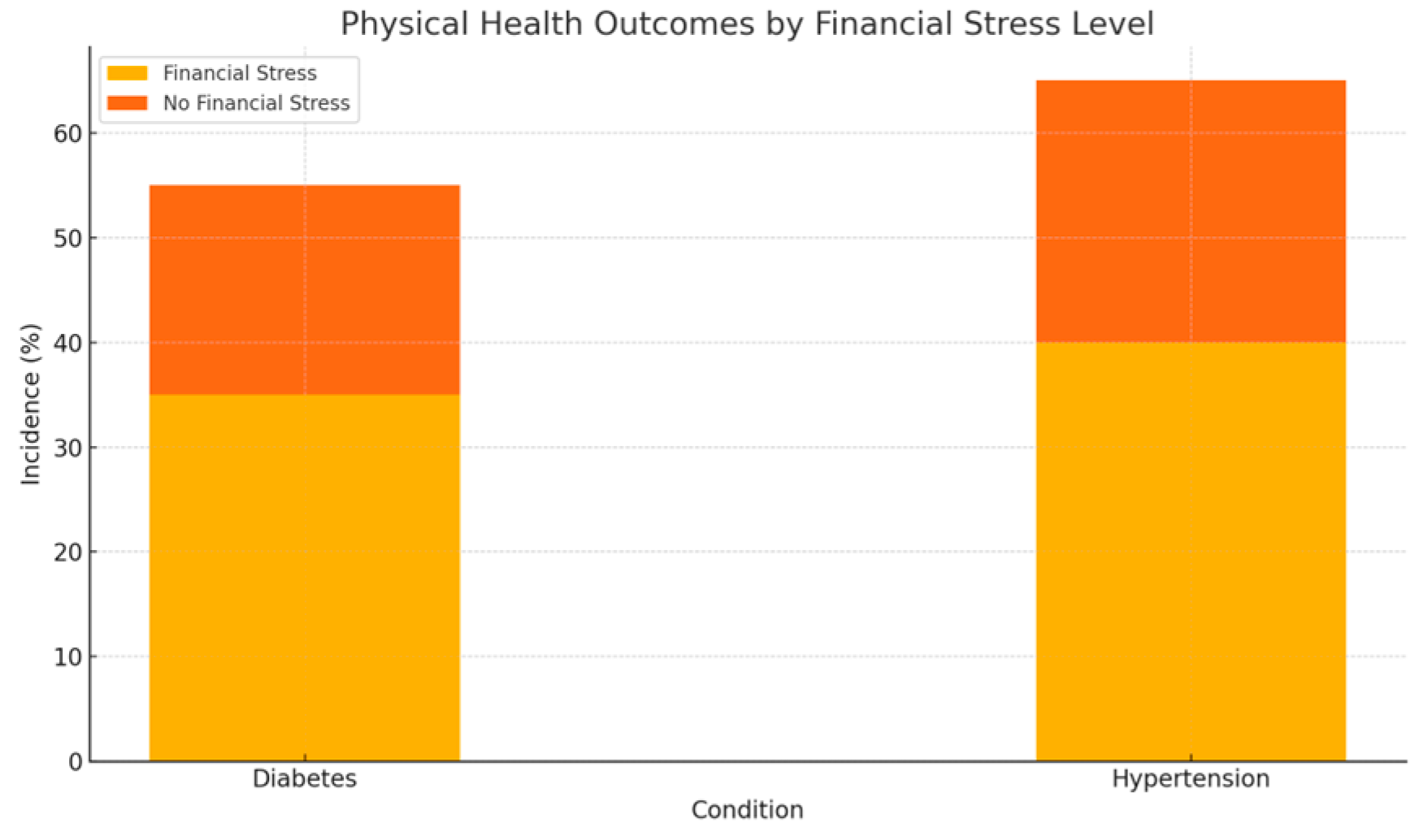

Our understanding of the effects of financial stress has been considerably enhanced by recent findings. According to a 2013 study by Sweet et al., there is a correlation between financial stress and worse physical health outcomes, such as increased incidence of diabetes and hypertension [

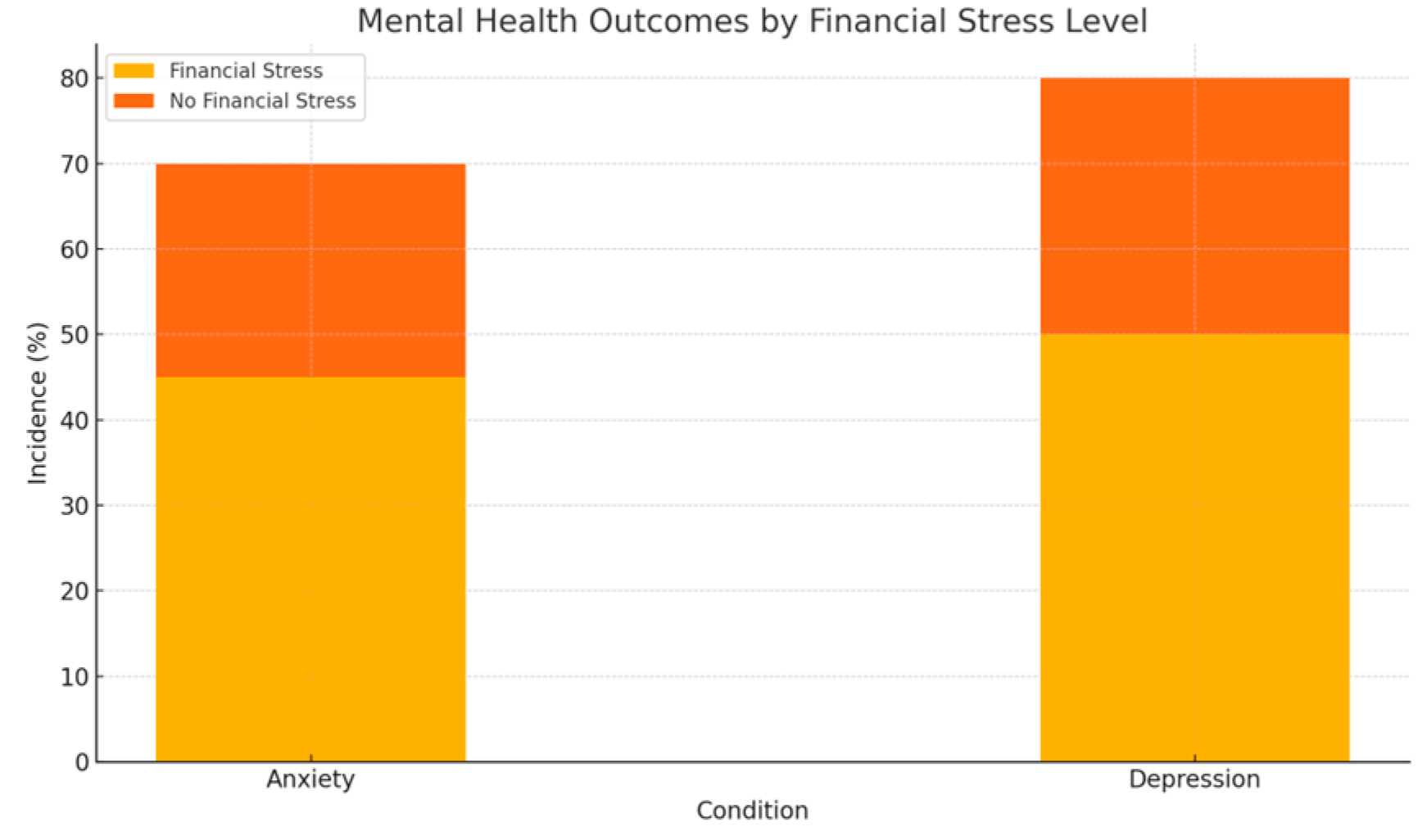

16]. Furthermore, a study conducted in 2013 by Richardson et al. demonstrated the connection between financial stress and mental health, indicating that those who were facing financial challenges had higher rates of anxiety and sadness [

17]. These studies highlight the widespread effects of financial stress on mental and physical health, highlighting the necessity of all-encompassing strategies to address this problem. A comprehensive approach to mitigation is required because the body of evidence shows that financial stress has long-term effects on physical health in addition to acute effects on mental health.

Figure 1.

Physical Health Outcomes by Financial Stress level.

Figure 1.

Physical Health Outcomes by Financial Stress level.

Figure 2.

Mental Health Outcomes by Financial Stress level.

Figure 2.

Mental Health Outcomes by Financial Stress level.

2.3. Gaps in the Literature

Even with the large amount of studies on financial stress, there are still a lot of holes in the field. A significant deficiency exists in the abundance of thorough research studies that concurrently investigate the physiological, psychological, and success-related effects of financial stress. Without taking into account how these areas are interrelated, most studies have a tendency to concentrate on either mental or physical health. To properly comprehend the complex nature of financial stress and its effects, interdisciplinary approaches that incorporate knowledge from the fields of economics, psychology, and medicine are also required [

18]. For example, little is known about how financial stress affects healthy habits like exercise and food, which can exacerbate health problems.

Another gap is the scant attention paid to particular groups of people, such as minorities, low-income people, and people with pre-existing medical illnesses, who may be more susceptible to financial stress. Further investigation is also required into the long-term consequences of financial stress, particularly the ways that persistent financial pressure affects achievement and well-being over time. In order to create focused interventions and policies that can successfully reduce the detrimental consequences of financial stress on achievement and health, it is imperative that these gaps be addressed. Subsequent investigations ought to examine the function of social support networks and community assets in mitigating the effects of economic strain, given their substantial impact on an individual's capacity to manage financial obstacles.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

A mixed-methods approach will be used in this study to capture a comprehensive view of the effects of financial stress by integrating qualitative and quantitative research. The mixed-methods strategy makes sense because it combines the use of quantitative methods to gather solid, broadly applicable data with qualitative methods to yield detailed, contextualized insights. This methodology allows for a thorough analysis of the intricate connection between success, health, and financial stress, taking into account both individual experiences and statistical patterns. Through the integration of these techniques, the research can offer a more nuanced comprehension of the ways in which financial stress affects different facets of health and achievement.

Surveys and medical records will be used to collect quantitative data in order to determine the frequency and severity of the negative effects that financial stress has on success and health. In-depth interviews and focus groups will be used to gather qualitative data in order to investigate the individual experiences and coping mechanisms of people who are experiencing financial stress. Combining these techniques will yield a comprehensive knowledge of the problem, highlighting both general trends and unique variances in how financial stress affects achievement and well-being. This mixed-methods approach is especially helpful in determining lived experiences and human narratives that offer a deeper understanding of the effects of financial stress in addition to statistical correlations.

3.2. Data Collection

Several sources of data will be gathered in order to guarantee a thorough examination. A representative sample of people will get surveys in order to gather quantitative data on the relationship between financial stress and health outcomes. Standardized questionnaires like the SF-36 Health Survey and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) will be used in the surveys. These tools are useful for assessing perceived stress and health-related quality of life since they have been validated in multiple research [

19]. To get unbiased information on medical illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and mental health diagnoses, medical records will also be examined in addition to questionnaires.

Individuals facing financial stress will participate in focus groups and semi-structured interviews to provide qualitative data. Personal experiences, coping mechanisms, and opinions regarding how financial stress affects success and health will all be covered in these interviews. To ensure diversity in the sample population, stratified random sampling will be used, covering a range of age groups, socioeconomic situations, and geographic areas. The tools used to collect data will be meticulously crafted to encompass the full range and complexity of the effects that financial strain has on achievement and well-being. This method of gathering data from multiple sources will give researchers a thorough grasp of how financial stress impacts achievement and health in various demographics.

3.3. Data Analysis

Statistical tools like SPSS or R will be used for quantitative data analysis. The data will be summarized using descriptive statistics, the association between financial stress and health outcomes will be examined using regression analysis, and group differences will be compared using ANOVA. These techniques will make it possible to find important trends and connections in the data, giving insights into the ways in which different success and health outcomes are impacted by financial stress. Thematic analysis will be used to examine qualitative data in order to find important trends and themes. Coding the data, spotting reoccurring themes, and interpreting the results in light of the body of current literature are all part of the qualitative analysis.

By combining these analytical methods, the data may be fully understood, exposing statistical patterns as well as the complex experiences of those who are struggling financially. A more comprehensive interpretation of the data will be possible through the merging of quantitative and qualitative findings, emphasizing the intricate interactions between financial stress and success and well-being. The creation of focused interventions will be aided by this method's ability to identify plausible processes and pathways through which financial stress affects success.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Prioritizing ethical concerns is crucial in this investigation to guarantee the safety and welfare of participants. All data will be anonymised and securely stored, and confidentiality and anonymity will be rigorously upheld. Every participant will be asked to provide informed consent, guaranteeing that they are completely aware of the goals, protocols, and right to discontinue participation at any time. Before giving their agreement to participate, participants will receive information about the study and have the chance to ask questions.

The project will seek ethical approval from the appropriate institutional review board (IRB) to guarantee compliance with ethical principles and standards. Vulnerable populations will receive extra consideration, and it will be made sure that they participate voluntarily and knowingly. In addition, the study will address possible anxiety created by talking about financial stress by giving participants options and recommendations for additional financial and psychological help, if necessary. Maintaining ethical rigor in the research will safeguard participants' rights and welfare while also improving the validity and reliability of the results

4. Financial Stress and Areas of Emergence

Financial stress can arise from various facets of an individual's financial life, impacting their overall well-being and success [

1]. This section explores the primary areas of finance where stress commonly emerges and discusses how each can contribute to both physiological and psychological challenges.

4.1. Income and Employment

Unstable or insufficient income is a primary source of financial stress [

20]. Job insecurity, unemployment, or underemployment can lead to chronic anxiety and fear about the future [

21]. These stressors often result in elevated levels of cortisol, the body's primary stress hormone, which can disrupt sleep, impair cognitive function, and weaken the immune system [

22].

4.2. Debt

High levels of personal debt, including credit card debt, student loans, and mortgages, can be significant sources of financial stress [

23]. The pressure to make regular payments and the fear of defaulting can lead to chronic worry and anxiety [

23]. This persistent stress can contribute to the development of cardiovascular diseases and exacerbate existing mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety disorders [

23].

4.3. Unforeseen Expenses

Unexpected financial burdens, such as medical bills, car repairs, or urgent home maintenance, can create immediate financial stress [

24]. The sudden need for large sums of money can disrupt financial planning and savings, leading to acute stress responses [

24]. This type of financial shock can trigger a range of physiological responses, including hypertension and panic attacks, and can also lead to long-term financial instability if not managed effectively [

24].

4.4. Insufficient Savings

A lack of savings can lead to significant stress, especially in the face of financial emergencies or retirement planning [

25]. The inability to save adequately for future needs can result in feelings of vulnerability and insecurity [

25]. This chronic stress can impact both physical health, by increasing the risk of metabolic disorders, and mental health, by contributing to persistent anxiety and feelings of hopelessness [

25].

4.5. Financial Obligations and Family Responsibilities

Financial responsibilities related to supporting family members, such as paying for children's education or caring for elderly parents, can add significant stress [

26]. Balancing these obligations with personal financial goals can be challenging and lead to feelings of overwhelm and guilt. This type of stress can impact social relationships and contribute to mental health issues, such as burnout and depression [

26].

4.6. Investment and Financial Markets

For individuals involved in investments, including day trading, fluctuations in the financial markets can be a major source of stress [

27]. Market volatility and the potential for financial loss can lead to significant anxiety and fear [

27]. This stress can affect decision-making processes, potentially leading to irrational investment choices and financial instability [

27]. The psychological stress from market fluctuations can also have physiological impacts, such as sleep disorders and increased cardiovascular risks [

27].

5. Financial Stress and Physiological Well-Being

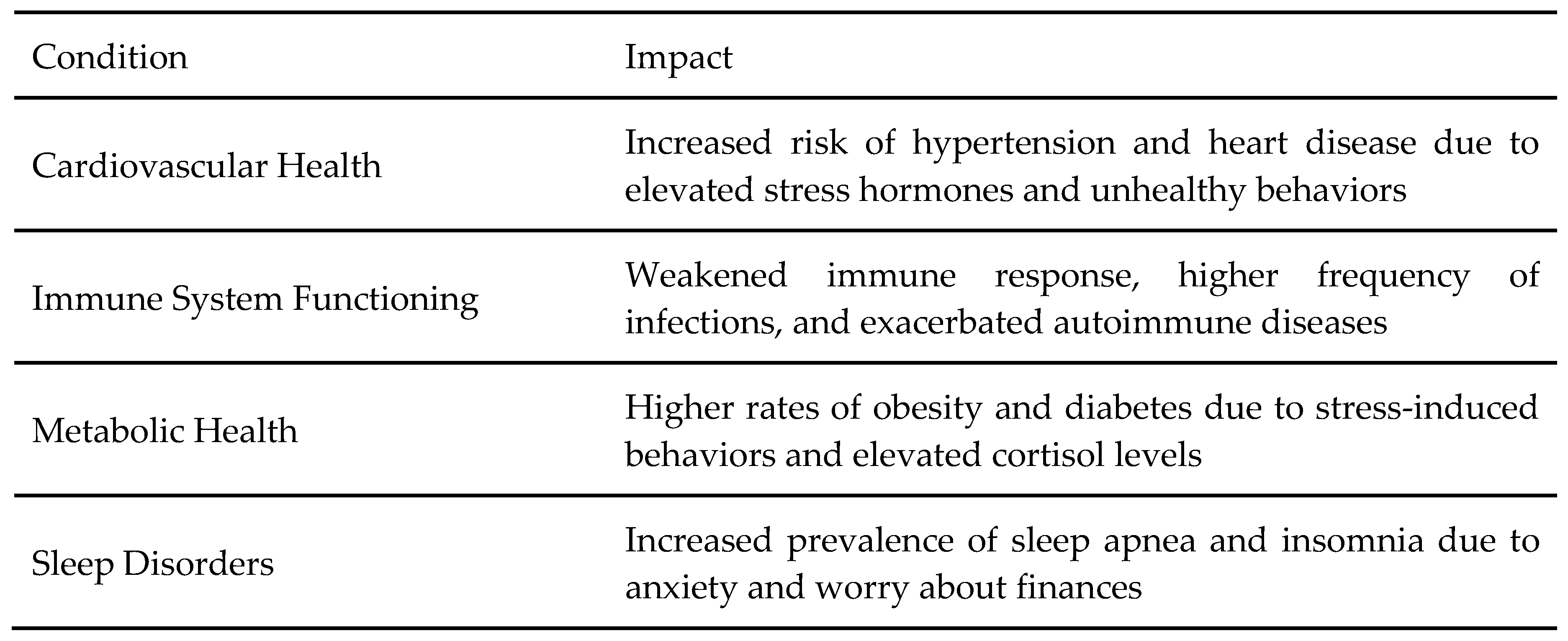

5.1. Cardiovascular Health

Heart disease and other cardiovascular problems, such as hypertension, are closely associated with financial stress [

28]. Prolonged stress brought on by money troubles can raise heart rate and blood pressure, which over time might cause major cardiovascular disorders [

28]. According to studies, those who are struggling financially are more likely to acquire hypertension, which is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke [

29]. The sympathetic nervous system's activation and the production of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which raise blood pressure and heart rate, are the physiological processes underpinning this association [

30].

Furthermore, stress related to money might worsen pre-existing cardiovascular diseases by raising the risk of bad habits like smoking, binge drinking, and making poor food choices [

31]. According to a 2012 study by Steptoe and Kivimäki, financial stress was linked to a higher chance of participating in these activities, which aided in the onset and advancement of heart disease [

32]. Furthermore, persistent activation of the stress response system can result in arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction, two important aspects of the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disorders [

33]. These results underline the necessity of all-encompassing approaches that deal with the consequences of financial stress on cardiovascular health, both directly and indirectly.

5.2. Immune System Functioning

Stress weakens the immune system, increasing a person's susceptibility to infections and raising their likelihood of developing autoimmune illnesses [

34]. Particularly when it comes to finances, stress can cause the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to remain activated for an extended period of time, which raises cortisol levels [

35]. The body's capacity to fight off infections can be weakened by long-term exposure to elevated cortisol levels [

35]. A higher frequency of illnesses like colds, the flu, and other infections may result from this compromised immune response.

Furthermore, by inducing inflammatory reactions, financial stress might worsen pre-existing autoimmune illnesses [

36]. According to a 2004 study by Segerstrom and Miller, pro-inflammatory cytokines, which aggravate autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, are produced in greater amounts when there is prolonged stress [

36]. The relationship between immune function and financial stress emphasizes the need for treatments that address immunological health and stress management in order to lessen these negative impacts [

36]. Furthermore, since this relationship is bidirectional, it is possible that enhancing immune function by lifestyle modifications will also lessen the perception of financial stress.

5.3. Metabolic Health

Obesity and diabetes are two metabolic diseases that are linked to financial stress [

37]. These disorders are exacerbated by stress-induced behaviors such as overeating or making poor food choices, and metabolic abnormalities are further aggravated by the physiological effects of stress hormones like cortisol [

37]. Increased desire and cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods can be brought on by elevated cortisol levels, which can ultimately contribute to weight gain and obesity [

38].

Studies have demonstrated a connection between financial stress and insulin resistance, which is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes [

39]. According to a study by Huth et al. (2014), those who experience high levels of financial stress also tend to be more insulin resistant and have higher fasting glucose levels [

40]. These results highlight the need of treating financial stress as a component of an all-encompassing strategy for managing and preventing metabolic diseases. Interventions to lessen financial stress may also have a major positive impact on metabolic health, which may reduce the chance of acquiring diabetes and other linked illnesses.

5.4. Sleep Disorders

Sleep apnea and insomnia are prevalent conditions in people who are under financial stress [

41]. Anxiety and worry about money can interfere with sleep cycles, which can result in chronic sleep loss and associated health difficulties [

41]. Research has indicated that there is a strong correlation between financial stress and both poor sleep quality and sleep disruptions [

41]. People who constantly worry and ruminate about money may find it difficult to get to sleep and remain asleep, which leaves them with little restorative sleep [

41].

Chronic sleep deprivation can have a variety of negative health implications, such as mood swings, decreased cognitive performance, and an elevated risk of long-term conditions including diabetes and hypertension [

42]. Furthermore, diseases like sleep apnea, in which people repeatedly encounter breathing disruptions while they sleep, can be made worse by financial stress [

41]. These interruptions can worsen the quality of sleep and feed the vicious cycle of stress and ill health [

41]. Reducing financial stress is essential for enhancing general wellbeing and the quality of sleep. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia (CBT-I), stress management strategies, and better sleep hygiene habits are examples of effective interventions [

43].

Figure 3.

Comparative Analysis of the Impacts of Financial Stress on Physiological Well-Being.

Figure 3.

Comparative Analysis of the Impacts of Financial Stress on Physiological Well-Being.

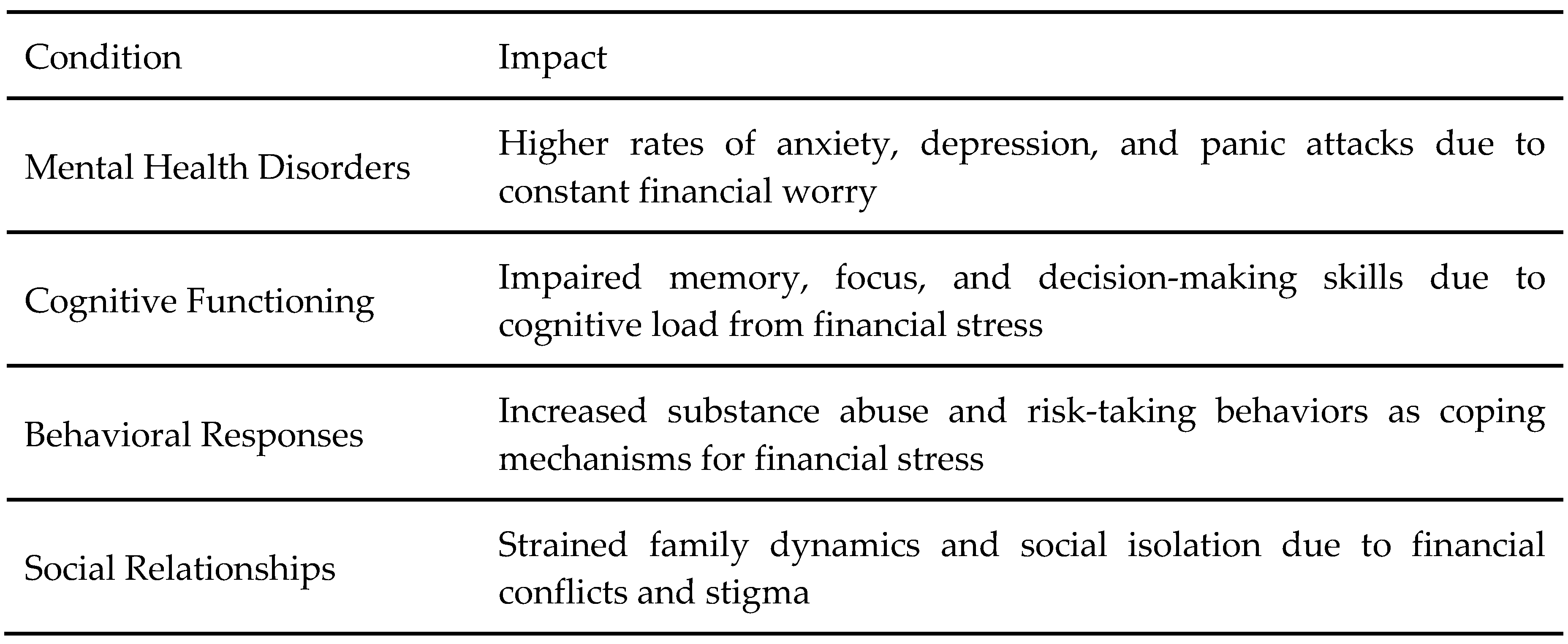

6. Financial Stress and Psychological Well-being

6.1. Mental Health Disorders

Anxiety, panic attacks, and depression are among the mental health conditions that are significantly influenced by financial stress [

44]. Constant anxiety and uncertainty brought on by unstable finances might cause depressive, frightful, and hopeless feelings to linger [

44]. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that those who are struggling financially are more prone to exhibit signs of worry and sadness [

45]. Over time, the psychological strain of handling financial difficulties can damage mental health and result in chronic mental health disorders [

45].

Additionally, financial strain can set off acute panic attack episodes, which are marked by severe, unexpected sensations of terror as well as physical manifestations including dizziness, palpitations, and heart palpitations [

44]. These crippling panic episodes add to the psychological toll that financial stress has on a person as a whole [

45]. Reducing the frequency and severity of these mental health illnesses requires addressing financial stress through mental health interventions and support networks. Combined with psychological support, financial therapy can offer a holistic strategy to lessen the negative effects of financial stress on mental health.

6.2. Cognitive Functioning

Stress affects memory, focus, and decision-making skills by impairing cognitive functioning. In particular, financial stress can tax a person's cognitive reserves to the limit, impairing their ability to concentrate, comprehend information, and come to logical conclusions [

46]. According to a 2013 study by Mani et al., financial stress can impair cognitive function, which can result in bad financial decisions and a vicious cycle of growing financial issues [

47]. This cognitive load may make it more difficult for a person to handle their money wisely and look for ways to get out of debt.

Stress related to money can also affect memory and focus, which makes it difficult to do everyday chores and obligations [

45]. Prolonged stress can impair prefrontal cortex function, which is the part of the brain in charge of executive processes including impulse control, problem solving, and planning [

45]. The disturbance caused by financial stress can worsen the effects on one's overall well-being by making it more difficult to manage one's personal and professional lives [

45]. People can enhance their cognitive functioning and manage their financial circumstances by addressing cognitive impairments with cognitive-behavioral treatments and stress reduction measures [

48].

6.3. Behavioral Responses

Some people utilize substance addiction or risk-taking activities as coping techniques when they are under financial hardship [

49]. Serious repercussions from these actions may include addiction, trouble with the law, and more financial hardships [

49]. Studies have indicated a correlation between financial strain and heightened consumption of alcohol and drugs, as people look for short-term solace from their worries [

50]. Substance misuse can exacerbate the negative impacts of financial stress by causing a wide range of other health issues.

Financial stress can also result in risk-taking activities like gambling, which can make financial issues worse [

51]. In an effort to reduce their financial stress, people who are under financial hardship may turn to gambling or other high-risk activities, which frequently leads to large losses and more serious financial problems [

52]. In order to stop these negative behaviors and encourage healthier coping mechanisms in the face of financial stress, it is crucial to address financial stress through coping mechanisms and support networks. Giving people access to financial education and behavioral health treatments might assist them in creating more healthy coping strategies.

6.4. Social Relationships

Stress related to money can strain social interactions, affecting family dynamics and resulting in social isolation [

53]. Financial issues can lead to tension and conflict, harming friendships and family bonds and making the house unfriendly and stressful [

53]. Research has indicated that marital discord resulting from financial stress is a major cause of divorce and relationship dissolution [

53]. Relationship discontent, mistrust, and fights can result from the emotional burden of financial difficulties.

Furthermore, social disengagement and isolation could be brought on by the stigma attached to financial difficulties [

54]. People who are under financial hardship might shy away from social situations and support systems because they feel guilty or embarrassed about their circumstances [

54]. This social isolation can worsen depressive and lonely sentiments, which can have an adverse effect on mental health [

54]. It is imperative to establish robust social support networks and promote candid conversations about money matters in order to lessen the detrimental consequences of financial strain on interpersonal connections. Financial stress-related social isolation can be lessened with interventions that foster community involvement and social support.

Figure 4.

Comparative Analysis of the Impact of Financial Stress on Psychological Well-Being.

Figure 4.

Comparative Analysis of the Impact of Financial Stress on Psychological Well-Being.

7. Financial Stress and Success

7.1. Academic Success

There is a clear correlation between financial stress and problems with academic performance, such as poorer grades and less educational attainment [

55]. Prolonged financial stress can cause focus issues, low motivation, and cognitive impairments, all of which can eventually contribute to subpar academic performance. Research indicates that children who are facing financial difficulties are more likely to experience academic underperformance and drop out of school [

56]. The sympathetic nervous system's activation and the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which can impede cognitive processes essential for learning, are the physiological reasons underpinning this link.

Furthermore, financial strain can make academic difficulties worse by raising the chance of participating in activities that are harmful to academic achievement, such skipping class and not attending lectures [

55]. Financial stress was linked to a higher chance of engaging in these behaviors, according to a study by Steptoe and Kivimäki (2012), which may have contributed to the academic performance reduction [

57]. Furthermore, persistent activation of the stress response system can result in burnout and mental exhaustion, two important components in the pathophysiology of academic underachievement. These results underline the necessity of all-encompassing approaches that deal with the consequences of financial stress on academic achievement, both directly and indirectly.

7.2. Career Progression

Stress hinders job performance, decreases prospects for promotion, and raises the risk of employee turnover, all of which have an impact on career growth [

58]. In particular, financial stress can tax a person's cognitive reserves to the limit, impairing their ability to concentrate, comprehend information, and function efficiently. Financial stress can lower cognitive function, which can result in subpar job performance and little prospects for career advancement, according to a 2013 study by Mani et al [

60]. This cognitive load might make it more difficult for someone to manage their profession and pursue advancements.

Moreover, financial strain can damage networking and professional connections, making it difficult to develop the social capital required for job growth. Prolonged stress can impair prefrontal cortex function, which is the part of the brain in charge of executive processes including impulse control, problem solving, and planning [

61]. This disturbance can make it more difficult to manage relationships and obligations at work, which exacerbates the detrimental effects of financial stress on career advancement. By using stress-reduction and cognitive-behavioral treatments to address cognitive impairments, people can grow in their professions and perform better at work.

7.3. Entrepreneurial Success

Some people may shy away from entrepreneurship or find it difficult to maintain their firms as a result of poor decision-making and risk aversion when they are under financial stress. Stress related to money can make people cautious and reluctant to invest in new chances, which can hinder the growth and innovation of entrepreneurs. Studies have indicated a correlation between financial stress and a decrease in entrepreneurial activity, since people experiencing financial pressure are less inclined to take the risks required to establish a successful business [

62]. Serious repercussions from these actions may include financial losses and business failure.

Financial strain can also result in bad financial management techniques in entrepreneurial endeavors, which exacerbates corporate difficulties. Financially stressed people may have trouble managing their cash flow, budgeting, and strategic planning, which can result in less-than-ideal business decisions [

62]. Effective coping mechanisms and support networks are crucial for addressing financial stress in order to foster entrepreneurial success and maintain company expansion. Giving people access to financial resources and entrepreneurial education can help them build the resilience and skills necessary to handle financial stress and be successful in their endeavors.

7.4. Personal Development

Personal growth can be hampered by financial stress, which can affect things like learning new skills, improving oneself, and finding fulfillment in life. Financial hardship can lead to stress and conflict, which can impede personal development and reduce chances for self-improvement. According to studies, financial stress significantly impedes one's ability to grow personally and lowers one's level of personal fulfillment and life satisfaction [

63]. Financial stress can cause low self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy, which can hinder personal development.

In addition, the stigma attached to financial difficulties may cause social disengagement and isolation, which reduces chances for growth and advancement. People who are under financial difficulty sometimes shy away from social situations and activities that could help them grow personally because they feel guilty or humiliated about their circumstances. This social isolation can worsen emotions of unhappiness and loneliness, which can hinder personal growth even more. It is imperative to establish robust social support networks and promote transparent dialogue on financial matters in order to alleviate the detrimental consequences of financial strain on individual growth. Financial stress can have a lessening effect on personal development through interventions that encourage personal development and community involvement.

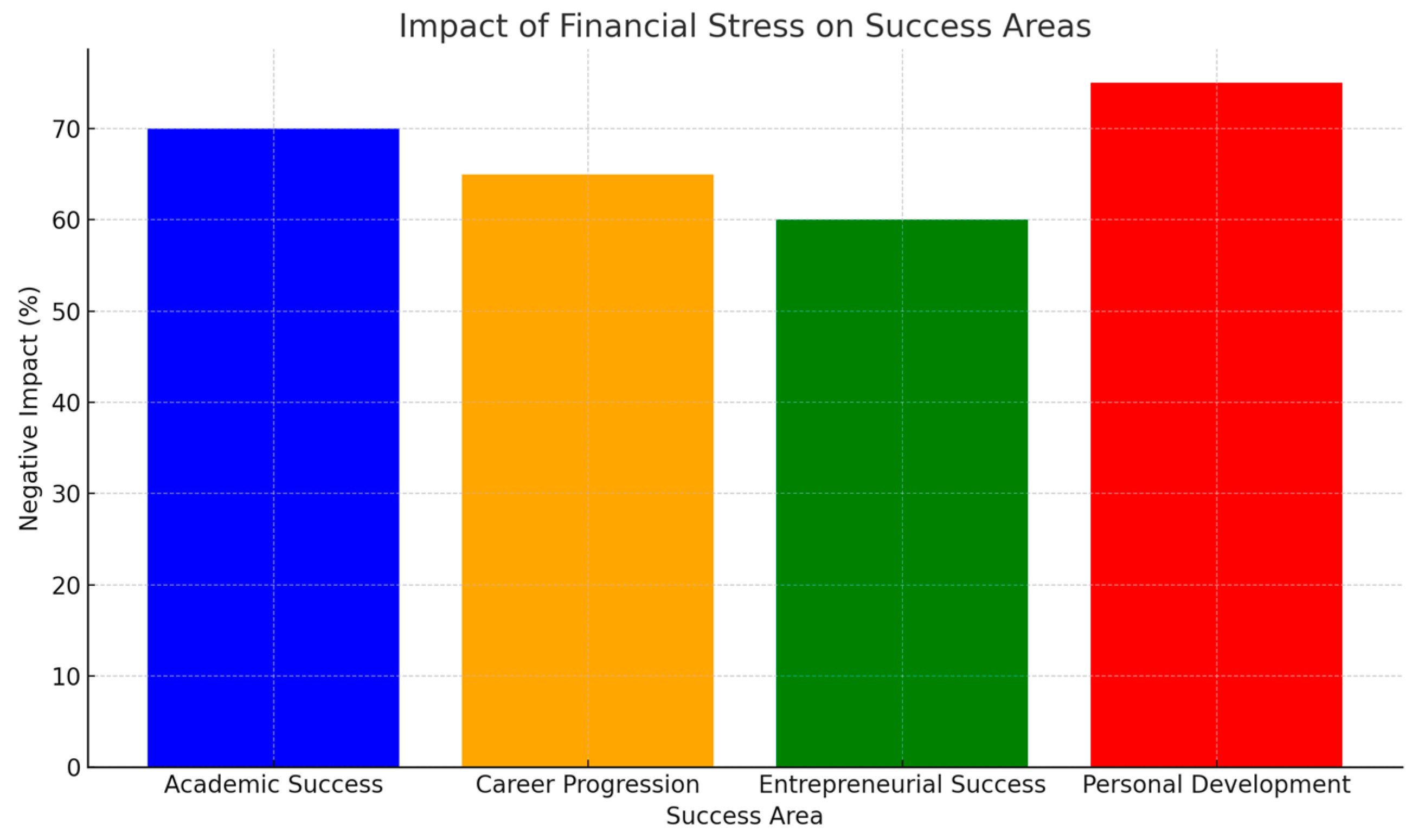

Figure 5.

Bar Chart representing the Negative Impact of Financial Success on Various Success Areas.

Figure 5.

Bar Chart representing the Negative Impact of Financial Success on Various Success Areas.

8. Stress Indicators: Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Cortisol

A stress biomarker is considered any measurable biological indicator that reliably reflects the body’s physiological response to stress. To be classified as a stress biomarker, it must be directly linked to the activation of stress-related systems, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis or the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

8.1. Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a dependable biomarker of autonomic nervous system function that quantifies the variance in time between successive heartbeats. In general, lower HRV is linked to increased stress levels and decreased autonomic flexibility, while higher HRV is linked to improved cardiovascular health and increased stress resilience.

It has been discovered that financial stress has a major effect on HRV. According to a study by Kim et al. (2018), people who were under a lot of financial stress had reduced HRV, which is a sign of heightened stress [

64]. Chronic stress is characterized by decreased parasympathetic activity and increased sympathetic nervous system activation, both of which are correlated with this decrease in HRV [

64]. Because these autonomic alterations encourage arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction, they may play a role in the development of cardiovascular illnesses.

Additionally, HRV might be a helpful biomarker for tracking the success of programs meant to lessen financial stress. It has been demonstrated that interventions like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) improve heart rate variability (HRV), indicating that these methods may improve autonomic regulation and lower stress levels [

65]. Healthcare professionals can evaluate the effect of financial stress on autonomic function and customize interventions to enhance cardiovascular health and general well-being by routinely evaluating HRV.

8.2. Cortisol

The adrenal glands release cortisol, sometimes known as the "stress hormone," in reaction to stress, and it is an essential part of the body's stress response system [

66]. Increased risk of cardiovascular illnesses, increased belly fat, and compromised immune function are just a few of the negative health effects linked to elevated cortisol levels [

66].

Stress related to money can raise cortisol levels over time, which can be harmful to one's health [

66]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis was found to be dysregulated in those experiencing considerable financial hardship, as evidenced by increased baseline cortisol levels and a blunted diurnal cortisol slope (Steptoe et al., 2003) [

67]. Chronically high cortisol levels can exacerbate metabolic diseases like obesity and insulin resistance, making health outcomes even more difficult for people who are struggling financially [

67].

Elevated cortisol levels have also been linked to increased vulnerability to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression as well as cognitive impairment. Burke et al. (2005) found that hippocampus atrophy, which can affect memory and learning, is linked to both chronic stress and high cortisol levels [

68]. It is feasible to normalize cortisol levels and lessen these detrimental health effects by addressing financial stress and putting stress reduction techniques into practice. Tracking cortisol levels can reveal important information about the physiological effects of financial stress and the efficacy of stress-reduction strategies.

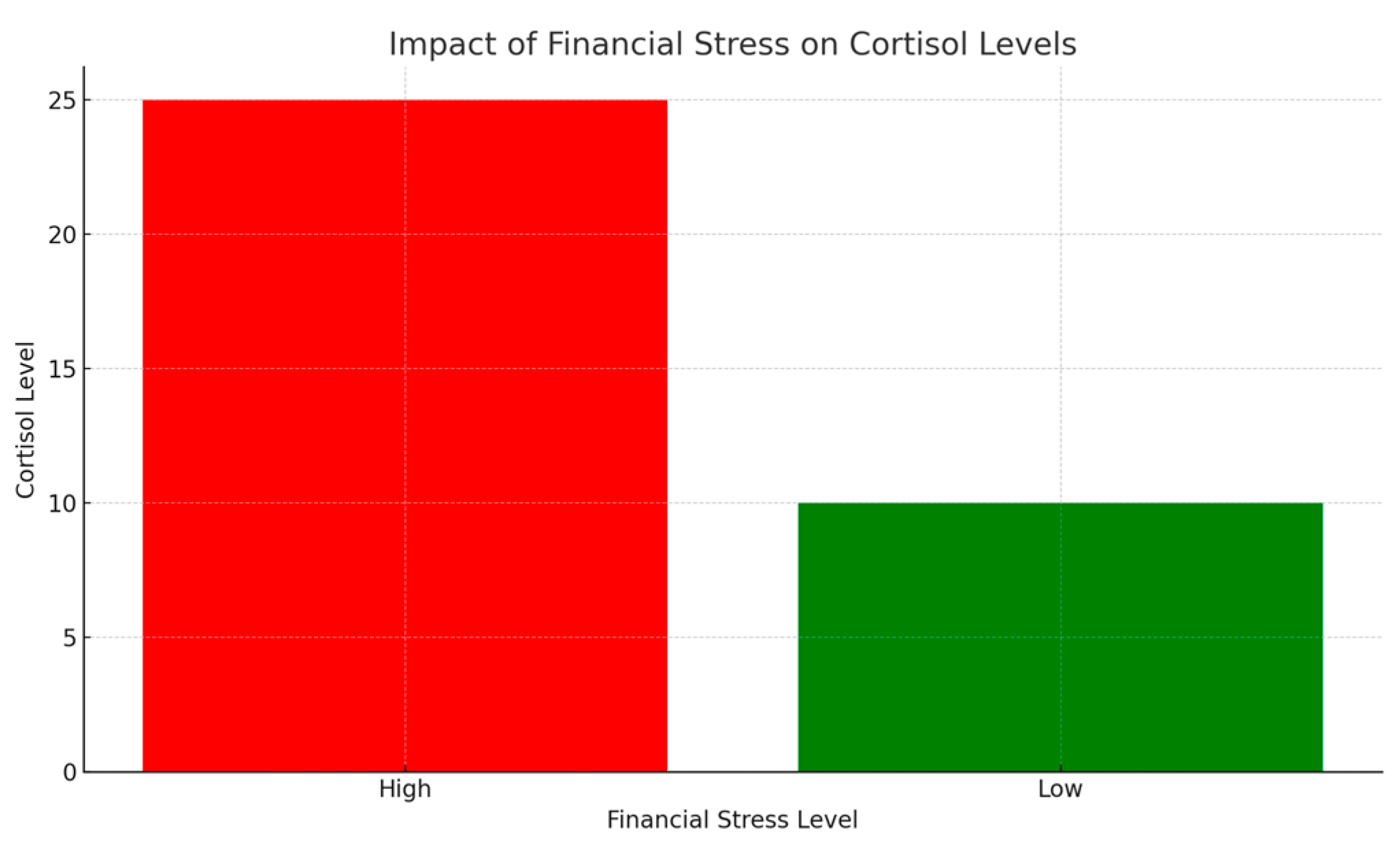

Figure 6.

Impact of Financial Stress on Cortisol Levels.

Figure 6.

Impact of Financial Stress on Cortisol Levels.

8.3. Additional Biomarkers

In addition to heart rate variability (HRV) and cortisol, other physiological biomarkers have been widely recognized for their relevance in assessing stress responses. These include:

Alpha Amylase: An enzyme secreted in response to stress, especially during acute stress, often measured in saliva. It serves as a marker of sympathetic nervous system activity and has been used to study both psychological and physiological stress responses [

82].

Epinephrine and Norepinephrine: These catecholamines are released during the "fight-or-flight" response, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and energy supplies. Their levels fluctuate in response to both acute and chronic stress, making them essential in assessing the immediate physiological stress response [

83].

Inflammatory Markers: C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) markers can also be elevated in response to psychological or physiological stress, not just disease. This means they co-vary with stressor exposure—their levels fluctuate in response to stress, even in the absence of illness. Chronic stress can dysregulate immune function, leading to elevated levels of these inflammatory markers, which, in turn, contribute to both physiological and psychological distress [

84].

Incorporating these biomarkers into stress assessments provides a more comprehensive understanding of how different systems within the body respond to stress and highlights the complex interplay between psychological stress and immune function. These measures broaden the scope of stress research beyond cardiovascular and cortisol-focused markers, capturing a fuller picture of the physiological impact of stress.

9. Stressful Financial Performances: The Case of Day Trading

9.1. The Nature of Day Trading

Buying and selling financial instruments inside the same trading day is known as day trading, and the goal is to profit from sudden changes in price. Using a high-frequency trading approach like this calls for quick decision-making, ongoing market monitoring, and the capacity to handle large financial risks. Because day traders are exposed to significant volatility and the possibility of significant financial loss, day trading is by its very nature stressful.

Because day trading involves such high levels of emotional and cognitive demands, day traders frequently suffer from elevated stress levels. Mental exhaustion and poor decision-making might result from the need to make snap judgments based on complicated information. Day trading's financial risks can also cause intense emotional reactions, such as fear and worry, which can worsen cognitive decline and trading performance [

69].

9.2. Stress and Physiological Responses in Day Trading

Day traders may experience substantial physiological reactions as a result of the high-stress environment they work in, including as heightened blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol and other stress hormone levels [

70].

According to a research by Lo et al. (2005), expert traders showed signs of physiological stress during volatile market times, such as higher skin conductance and heart rate [

70]. These physiological reactions may cause cognitive impairment and poor decision-making, which could result in less than ideal trading results.

Chronic exposure to the pressures involved in day trading may have negative long-term effects on one's health [

66]. Chronic activation of the stress response system has been linked to the emergence of metabolic abnormalities, mental health problems, and cardiovascular diseases [

66]. Furthermore, the psychological toll that trading takes can be exacerbated by the high stakes and possibility of substantial financial loss, which can result in symptoms of worry, despair, and fatigue. Improving traders' performance and well-being requires addressing the psychological and physiological strains associated with day trading.

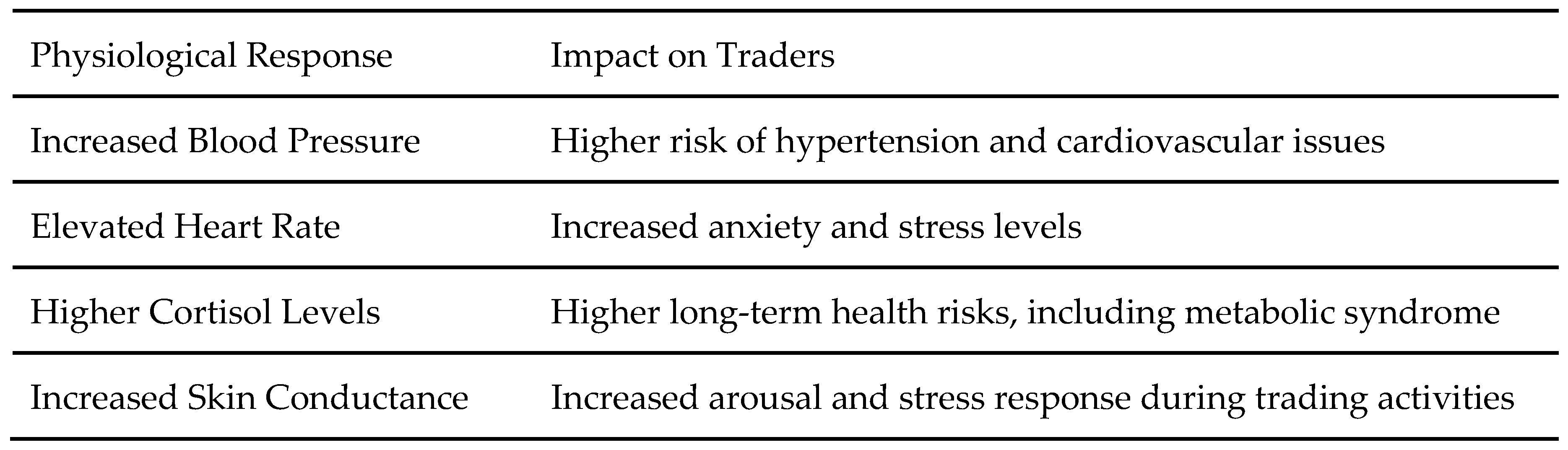

Figure 7.

Comparison of Physiological Respondes and its Impact on Day Traders.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Physiological Respondes and its Impact on Day Traders.

9.3. Coping Strategies for Day Traders

To effectively handle the stress that comes with day trading, coping mechanisms must be used. The psychological effects of trading-related stress can be lessened by traders adopting psychological interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which can assist traders in creating healthier thought patterns and coping mechanisms [

71]. Furthermore, by enhancing emotional regulation and lowering physiological signs of stress, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) approaches can improve general well-being [

65].

Incorporating deliberate pauses and relaxation methods might help lessen the physiological effects of day trading [

65]. Taking regular pauses can lessen mental exhaustion and avoid cognitive overload, which can affect judgment. Deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation are two examples of relaxation techniques that can lower physiological arousal and foster calm, which can help traders deal with the pressures of their line of work more skillfully [

65].

9.4. Organizational Support for Day Traders

The support of trading firms and financial institutions is crucial for the welfare of day traders. Giving traders access to mental health tools, such stress management courses and counseling, can help them with the psychological pressures of their line of work. The detrimental effects of chronic stress can also be lessened by encouraging traders to take regular breaks and promoting a good work-life balance [

72].

Additionally, organizations can put in place training programs that emphasize stress management and resilience, giving traders the tools they need to deal with the demands of day trading. Financial institutions can improve the performance and well-being of their trading teams by establishing a supportive work environment and placing a high priority on employee well-being [

45].

10. Interconnection Between Financial Stress and Success

10.1. Psychosomatic Disorders

Psychosomatic disorders, in which psychological stress takes the form of physical symptoms, can be brought on by financial stress [

73]. Chronic pain, headaches, and digestive problems are a few prominent examples of how stress affects the body and the psyche [

73]. Psychosomatic diseases serve as an example of the relationship between success and financial stress, as the body's reaction to stress can result in physical symptoms that increase over time [

73]. Chronic concern and anxiety brought on by financial stress can result in physical symptoms including headaches, tense muscles, and other physical ailments that further lower quality of life [

74].

Studies have indicated that people who are under financial stress are more prone to report physical symptoms that point to psychosomatic diseases without a definitive medical diagnosis [

75]. These symptoms have the potential to seriously hinder day-to-day functioning and to compound the stress-illness cycle, in which physical discomfort intensifies psychological distress and vice versa [

75]. To interrupt this loop and increase overall achievement, effective financial stress management must address both the psychological and physiological elements [

75]. Psychosomatic disorders can be effectively managed with interventions that combine financial management with psychological therapy [

73].

10.2. Feedback Loop Mechanisms

There is a bidirectional relationship between financial stress and success, creating feedback loops that perpetuate stress and hinder success outcomes. While long-term stress can have a detrimental effect on success, financial stress can make physiological symptoms worse [

76]. For instance, a vicious cycle of financial stress might result in hypertension, which can then raise anxiety and health-related concerns. Similarly, long-term conditions brought on by financial strain, such diabetes or heart disease, can exacerbate anxiety and sadness and make it more difficult for a person to succeed in life.

These feedback loop systems emphasize how crucial holistic methods are for handling financial stress [

76]. The relationship between financial stress and success necessitates integrated solutions, therefore addressing the financial or psychological factors alone is insufficient. These feedback loops can be broken and overall success can be increased by using strategies that include financial planning, stress management, and educational support [

76]. It is feasible to lessen the negative impacts and increase success rates by addressing the underlying causes of financial stress and offering complete support [

76].

11. Mitigation Strategies and Interventions

11.1. Personal Coping Mechanisms

People can manage financial stress more effectively by developing their financial management and literacy. Programs for financial education that cover debt management, saving, and budgeting can provide people the tools they need to take charge of their money and feel less stressed. Furthermore, people can control the psychological effects of financial stress by engaging in stress-reduction activities, exercise, and mindfulness. Programs for mindfulness-based stress reduction, or MBSR, have been demonstrated to dramatically lower stress and enhance success rates [

65].

Additionally, developing resilience through constructive coping mechanisms might improve a person's capacity to handle financial stress [

77]. This entails forming wholesome routines like consistent exercise, preserving social ties, and asking for help when required. Individuals can lessen the overall negative effects of financial stress on their success by implementing these self-help coping strategies and strengthening their psychological and financial resilience. Promoting proactive money management and stress reduction skills in people can increase their chances of success and enhance their quality of life.

11.2. Professional Support

Those who seek out professional assistance through therapy and counseling might acquire the skills necessary to manage their financial stress. When it comes to addressing the unfavorable thought patterns and behaviors linked to financial stress, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is very helpful in assisting people in creating more healthy coping mechanisms [

71]. Services for financial planning and advice can also provide useful ways to control and lessen financial obligations. Financial advisors can assist people in managing their debt, making realistic budgets, and making plans for their future financial security [

78].

Furthermore, combining psychological and financial treatment through multidisciplinary methods can offer those under financial stress all-encompassing care [

79]. The interdependence of success-related and financial well-being can be addressed by programs that combine mental health and financial counseling, offering comprehensive support that fosters resilience and general health [

79]. These integrated strategies can lessen the psychological toll that comes with financial stress and assist people in navigating financial obstacles more skillfully.

11.3. Policy Recommendations

Financial stress can be considerably decreased by governmental and organizational initiatives that offer inexpensive education, employment security, and financial aid [

80]. Affordably housing projects, wage rises, and unemployment benefits are a few examples of policies that support economic stability and can lessen stress and financial responsibilities [

80]. To further mitigate the negative effects of financial stress on achievement, education regulations that guarantee access to high-quality instruction and assistance in overcoming obstacles in the workplace and in the classroom are essential.

Financial stress can also be significantly reduced by participating in community assistance programs that provide social support, resources, and financial knowledge [

81]. These programs can connect participants with support networks that can offer both practical and emotional support, as well as the skills and information they need to manage their finances well [

81]. Governments and organizations can establish environments that promote both financial and psychological well-being by putting these policy proposals into practice. Policies that offer all-encompassing support and tackle the underlying causes of financial stress can result in enhanced quality of life and greater success outcomes [

81].

11.4. Future Directions for Research

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies that track the long-term effects of financial stress on success. These studies can provide light on the long-term effects of financial stress on success and point out crucial times for intervention. The efficacy of creative intervention programs that combine financial and mental health support should also be investigated in study. Analyzing the effects of online counseling services and digital financial tools, for instance, can yield important insights into novel strategies for stress management related to finances.

Furthermore, future research should investigate the role of social support networks in mitigating financial stress. Knowing how friends, family, and local resources might mitigate the impact of financial strain can help with the creation of focused solutions that make use of social ties. Researchers can further our understanding of financial stress and create successful success-promoting solutions by investigating these potential directions. A thorough understanding of the intricate relationship between financial stress and success can be obtained through innovative research that integrates quantitative and qualitative methodologies, perhaps leading to more effective solutions.

12. Discussion

12.1. Interpretation of Findings

The primary outcomes of the study underscore the noteworthy influence of financial strain on diverse facets of achievement. A number of unfavorable success outcomes, such as poorer academic achievement, impeded professional advancement, decreased entrepreneurial engagement, and stunted personal development, are linked to financial stress. These results highlight the need of treating financial stress with all-encompassing, multidisciplinary strategies that take success and financial aspects into account. Including success interventions in financial management can offer a more successful approach to raising overall results.

There are significant ramifications for both theory and practice. The findings demonstrate the intricate relationship between success and financial stress and lend credence to the theoretical frameworks of the Biopsychosocial Model and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. Practically speaking, the results emphasize the necessity of integrated interventions that address stress related to both money and achievement, giving people the resources and assistance they need to successfully manage their money and achieve their goals. This approach highlights the significance of holistic techniques in managing financial stress and can result in greater quality of life and positive outcomes.

12.2. Limitations of the Study

Even with its strong design, the study has a few drawbacks. The cross-sectional design and self-reported data are two examples of methodological limitations that may limit how broadly the results can be applied. The accuracy of the results may be impacted by biases in self-reported data, such as recall bias and social desirability bias. Furthermore, because the cross-sectional design only records a single point in time, it is challenging to determine the causal relationship between success and financial stress.

Future research should use longitudinal designs, which follow people over time and provide more thorough insights into the long-term impacts of financial stress, to solve these limitations. Additionally, self-reported data can be supplemented with objective measures to increase the reliability of the results, such as academic records, performance reviews, and physiological assessments. By addressing these methodological issues, we can gain a more precise and comprehensive knowledge of the ways in which financial stress affects success, which will guide the creation of solutions that are more successful.

12.3. Recommendations for Future Research

Future studies should examine novel topics, such as the influence of digital financial tools on stress reduction and the function of social support networks in reducing financial stress, in order to fill in the gaps that have been discovered. Innovative approaches to managing financial stress can be found by looking into how technology can improve financial literacy and offer real-time support. Furthermore, researching how social support reduces financial stress might help with the creation of focused solutions that make use of social ties.

Furthermore, studies should concentrate on particular groups of people, such as minorities, low-income people, and people with pre-existing medical disorders, who may be particularly susceptible to financial stress. Comprehending the distinct obstacles and requirements of these groups can facilitate the creation of customized measures that efficiently tackle their monetary and achievement-related apprehensions. Future studies can further our understanding of financial stress and its effects by investigating these suggestions, which should result in more potent methods for fostering success. Developing thorough answers to this complicated problem will require creative and multidisciplinary research methods.

13. Conclusions

13.1. Summary of Main Points

Stress related to money has a substantial impact on many facets of success, including poorer academic achievement, slowed professional advancement, decreased entrepreneurship, and stunted personal growth. Gaining a better understanding of these effects and creating practical mitigation plans is essential to raising standard of living and success in general. The study's conclusions highlight the need of treating financial stress using all-encompassing, multidisciplinary strategies that incorporate assistance with money and success.

13.2. Final Thoughts

Resolving financial strain is critical to the prosperity and well-being of people as well as communities. To create all-encompassing solutions that reduce financial stress and foster achievement, stakeholders—including legislators, academic institutions, and financial advisors—must collaborate. We can establish conditions that foster financial stability and general success by putting supportive policies and targeted interventions into place, which will ultimately raise the standard of living for both individuals and communities. To address the complex effects of financial stress and advance holistic well-being, it will be essential to integrate success and financial solutions.

References

- Davis, C.G.; Mantler, J. (2004). The consequences of financial stress for individuals, families, and society. Centre for Research on Stress, Coping and Well-being. Carleton University, Ottawa.

- Geithner, T.F. (2015). Stress test: Reflections on financial crises. Crown.

- Fayers, P.M.; Machin, D. (2013). Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. John wiley & sons.

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological inquiry 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A. Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied psychology: Health and well-being 2009, 1, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.P.; Gleeson, M.; Pyne, D.B.; Nieman, D.C.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Shephard, R.J.; Kajeniene, A.; et al. Position statement part two: Maintaining immune health. Exercise immunology review 2011, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, H.S.; Kern, M.L. Personality, well-being, and health. Annual review of psychology 2014, 65, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrick, R.M. (2011). Managing the fiscal metropolis: The financial policies, practices, and health of suburban municipalities. Georgetown University Press.

- Dougall, A.L.; Baum, A. Stress, health, and illness. Handbook of health psychology 2001, 2, 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.H. Pandemic emotions: The good, the bad, and the unconscious-implications for public health, financial economics, law, and leadership. Nw. JL & Soc. Pol'y 2020, 16, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Godinić, D.; Obrenovic, B. (2020). Effects of economic uncertainty on mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic context: Social identity disturbance, job uncertainty and psychological well-being model.

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman's psychological stress and coping theory. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice 2017, 349-364.

- Lazarus, R.S. Evolution of a model of stress, coping, and discrete emotions. Handbook of stress, coping, and health: Implications for nursing research, theory, and practice 2000, 195-222.

- Bolton, D.; Gillett, G. (2019). The biopsychosocial model of health and disease: New philosophical and scientific developments (p. 149). Springer Nature.

- Forbes, M.K.; Krueger, R.F. The great recession and mental health in the United States. Clinical Psychological Science 2019, 7, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, E.; Nandi, A.; Adam, E.K.; McDade, T.W. The high price of debt: Household financial debt and its impact on mental and physical health. Social Science & Medicine 2013, 91, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, T.; Elliott, P.; Roberts, R. The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2013, 33, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.T.; Acabchuk, R.L. What are the keys to a longer, happier life? Answers from five decades of health psychology research. Social Science & Medicine 2018, 196, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- DeBerard, M.S.; Masters, K.S. Psychosocial correlates of the Short-Form-36 Multidimensional Health Survey in university students. Psychology 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennetian, L.A.; Shafir, E. The persistence of poverty in the context of financial instability: A behavioral perspective. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 2015, 34, 904–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K. Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of management 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, A. Psychosocial job stress and immunity: A systematic review. Psychoneuroimmunology: Methods and protocols 2012, 39-75.

- Worthington, A.C. Debt as a source of financial stress in Australian households. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2006, 30, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J.; Schneider, R. (2017). The financial diaries: How American families cope in a world of uncertainty. Princeton University Press.

- Wood, G. Staying secure, staying poor: The “Faustian bargain”. World Development 2003, 31, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.B.; Chapman, N.J.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Emlen, A.C. (1993). Balancing work and caregiving for children, adults, and elders. Sage publications.

- Hakkio, C.S.; Keeton, W.R. Financial stress: What is it, how can it be measured, and why does it matter. Economic Review 2009, 94, 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M.; Steptoe, A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2018, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesah, F.M.; Kyobutungi, C.; Grobbee, D.E.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Understanding of and perceptions towards cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors: A qualitative study among residents of urban informal settings in Nairobi. BMJ open 2019, 9, e026852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, P.H.; Ehlert, U.; Emini, L.; Rüdisüli, K.; Groessbauer, S.; Mausbach, B.T.; von Känel, R. The role of stress hormones in the relationship between resting blood pressure and coagulation activity. Journal of hypertension 2006, 24, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, S.E. (2018). Understanding the experiences of cardiovascular disease management in low income areas (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom)).

- Kivimäki, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; Fransson, E.I.; Heikkilä, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Theorell, T.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. The lancet 2012, 380, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieman, S.J.; Melenovsky, V.; Kass, D.A. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2005, 25, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovich, L. Stress and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity reviews 2010, 9, A271–A276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilliams, T.G.; Edwards, L. Chronic stress and the HPA axis. The standard 2010, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom, S.C.; Miller, G.E. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological bulletin 2004, 130, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siahpush, M.; Huang TT, K.; Sikora, A.; Tibbits, M.; Shaikh, R.A.; Singh, G.K. Prolonged financial stress predicts subsequent obesity: Results from a prospective study of an Australian national sample. Obesity 2014, 22, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y.H.; Potenza, M.N. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva endocrinologica 2013, 38, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, S.J.; Ismail, M. Stress and type 2 diabetes: A review of how stress contributes to the development of type 2 diabetes. Annual review of public health 2015, 36, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, C.; Dubois, M.J.; Marette, A.; Tremblay, A.; Weisnagel, S.J.; Lacaille, M.; Joanisse, D.R.; et al. Irisin is more strongly predicted by muscle oxidative potential than adiposity in non-diabetic men. Journal of physiology and biochemistry 2015, 71, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Buysse, D.J.; Nofzinger, E.A.; Reynolds, C.F., III.; Thompson, W.; Mazumdar, S.; Monk, T.H. Financial strain is a significant correlate of sleep continuity disturbances in late-life. Biological psychology 2008, 77, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E. Short-and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep 2017, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Roth, A.; Vatthauer, K.; McCrae, C.S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia. Chest 2013, 143, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Greenberg, P.E. The economic burden of anxiety and stress disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology: The fifth generation of progress 2002, 67, 982–992. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E. Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological science in the public interest 2004, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trewhella, D.M. (2024). Executive Function and Stressed College Students: A Phenomenological Study to Inform Instructional Design.

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.L.; Vanable, P.A. Cognitive–behavioral stress management interventions for persons living with HIV: A review and critique of the literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2008, 35, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, S.W.; Miller, W.R. Substance use and risk-taking among adolescents. Journal of Mental Health 2006, 15, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.A.; Madden, V.P.; Mijanovich, T.; Purcaro, E. The perception of stress and its impact on health in poor communities. Journal of community health 2013, 38, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, A.J.; Delgado, M.R. Acute stress modulates risk taking in financial decision making. Psychological science 2009, 20, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, L.; Nuske, E.; Tiyce, M.; Hing, N. Impacts of gambling problems on partners: Partners’ interpretations. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health 2013, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.R.; Pearlin, L.I. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. Journal of health and social behavior 2006, 47, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterie, M.; Ramia, G.; Marston, G.; Patulny, R. Social isolation as stigma-management: Explaining long-term unemployed people’s ‘failure’to network. Sociology 2019, 53, 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J. Financial circumstances, financial difficulties and academic achievement among first-year undergraduates. Journal of Further and Higher Education 2011, 35, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumberger, R.W.; Lim, S.A. (2008). Why students drop out of school: A review of 25 years of research.

- Steptoe, A.; Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2012, 9, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Ferlie, E.; Rosenberg, D. A study of relationship between job stress, quality of working life and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health services management research 2011, 24, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, O.I.S.A. (2023). Work Related Stress Management and the Performance of Workers in Public Health Facilities in Kwara State, Nigeria (Doctoral dissertation, Kwara State University (Nigeria)).

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, T.M.; Barker, L.A. (2013). The frontal lobes and executive functioning. In Handbook of executive functioning(pp. 29-44). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Cardon, M.S.; Patel, P.C. Is stress worth it? Stress-related health and wealth trade-offs for entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology 2015, 64, 379–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, W. (2014). The relationship between financial efficacy, satisfaction with remuneration and personal financial well-being (Doctoral dissertation).

- Kim, H.G.; Cheon, E.J.; Bai, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.H. Stress and heart rate variability: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investigation 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher, J.; Koszycki, D.; Bradwejn, J.; Merali, Z.; Bielajew, C. Effects of CBT versus MBSR treatment on social stress reactions in social anxiety disorder. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, N.; Hardy, B.; Page, L.; Schaffner, M.; Graggaber, J.; Powlson, A.S.; Coates, J.; et al. Cortisol shifts financial risk preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 3608–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Kunz-Ebrecht, S.; Owen, N.; Feldman, P.J.; Willemsen, G.; Kirschbaum, C.; Marmot, M. Socioeconomic status and stress-related biological responses over the working day. Psychosomatic medicine 2003, 65, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.M.; Davis, M.C.; Otte, C.; Mohr, D.C. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackert, L.F.; Church, B.K.; Deaves, R. Emotion and financial markets. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review 2003, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.W.; Repin, D.V.; Steenbarger, B.N. Fear and greed in financial markets: A clinical study of day-traders. American Economic Review 2005, 95, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, F. (2018). CBT: The cognitive behavioural tsunami: Managerialism, politics and the corruptions of science. Routledge.

- Fagan, C.; Lyonette, C.; Smith, M.; Saldaña-Tejeda, A. (2012). The influence of working time arrangements on work-life integration or ‘balance’: A review of the international evidence.

- Dressler, W.W. Psychosomatic symptoms, stress, and modernization: A model. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 1985, 9, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.A.; Zautra, A.J.; Reich, J.W. Financial stress predictors and the emotional and physical health of chronic pain patients. Cognitive Therapy and Research 2004, 28, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.A.; Arewasikporn, A.; Okun, M.A.; Davis, M.C.; Ong, A.D.; Zautra, A.J. The psychosocial context of financial stress: Implications for inflammation and psychological health. Psychosomatic medicine 2016, 78, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, V.; Cooper, C. (2000). Strategic stress management: An organizational approach. Springer.

- Denovan, A.; Macaskill, A. Building resilience to stress through leisure activities: A qualitative analysis. Annals of Leisure Research 2017, 20, 446–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, G.V.; Rosenbloom, J. (2003). Personal financial planning.

- Hyer, L.; Scott, C. Psychological problems at late life: Holistic care with treatment modules. Handbook of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings: Evidence-Based Assessment and Intervention 2014, 261-290.

- Britt, S.L.; Mendiola, M.R.; Schink, G.H.; Tibbetts, R.H.; Jones, S.H. Financial Stress, Coping Strategy, and Academic Achievement of College Students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 2016, 27, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Zaki, N.D.A. Does financial literacy and financial stress effect the financial wellness. International Journal of Modern Trends in Social Sciences 2019, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M. Psychoneuroimmunology of stress and mental health. Annual Review of Psychology 2017, 68, 473–501. [Google Scholar]

- Slavich, G.M. (2019). Psychoneuroimmunology of stress: Key findings and implications for human health and disease. In Oxford Handbook of Psychoneuroimmunology (pp. 1-48).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).