Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

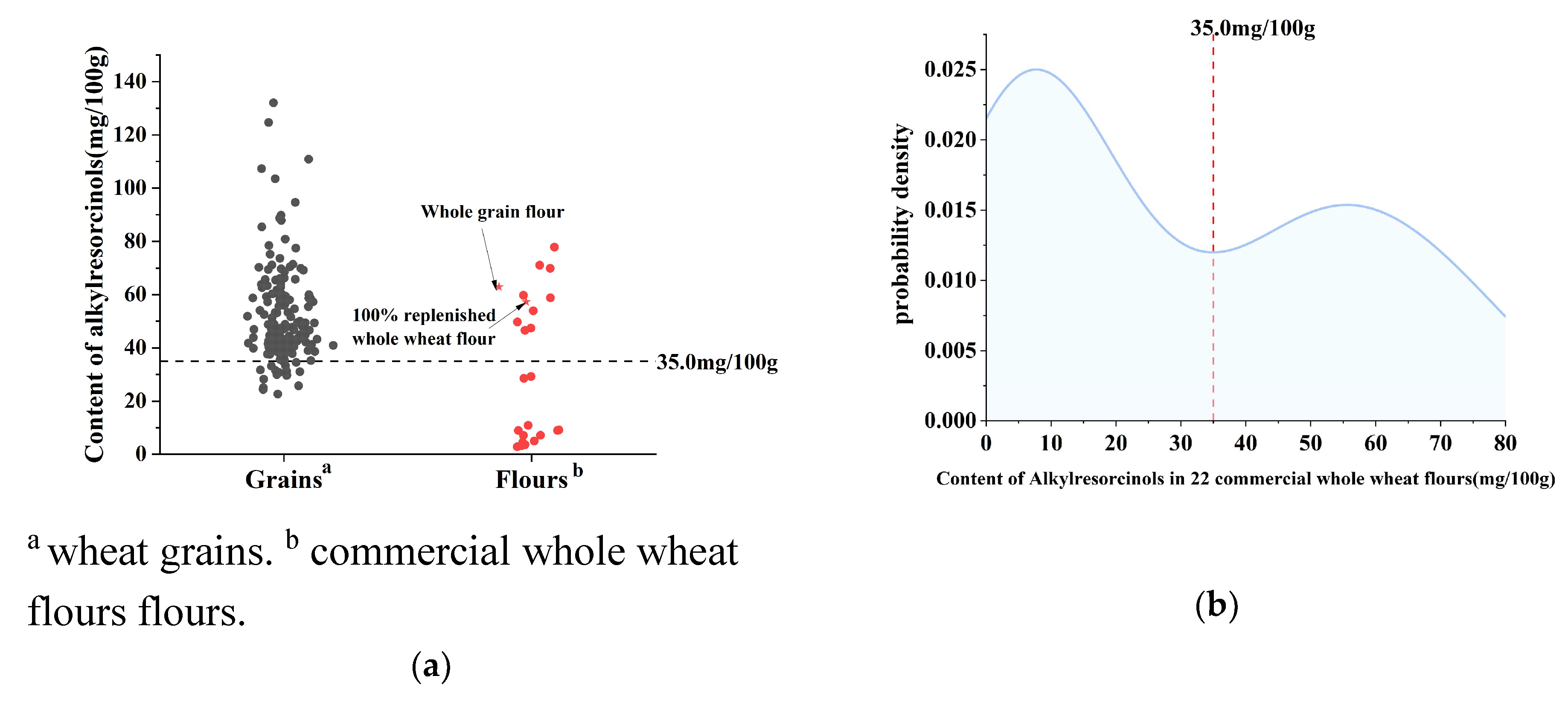

Alkylresorcinols (ARs) are recognized biomarkers of whole grains, exhibiting biological functions such as antioxidant activity and inhibition of cancer cell proliferation, and correlated with nutrients, including fat, dietary fiber, and carbohydrates. ARs can be regarded as a valuable nutritional indicator for evaluating the nutritional quality of whole wheat flour. Objectives: This study aimed to assess the ARs content in Chinese commercial whole wheat flour, establish a nutritional quality cut-off point based on ARs, and screen the 100% whole wheat flour. Methods: In this study, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to determine the ARs content in 17 Chinese wheat grains and 22 commercial whole wheat flours. Meanwhile, the ARs content in wheat grains reported in other relevant studies was also included. Then, the ARs cut-off point of whole wheat flour was calculated, and this value was applied to distinguish the nutritional quality of the commercial whole wheat flour and screen the 100% whole wheat flour. Results: The average total ARs content in the 22 commercial whole wheat flours was 19.8 mg/100 g, ranging from 2.9 to 77.9 mg/100 g, presenting a bimodal distribution, with 40.9% exceeding the cut-off point. Consequently, approximately 40.9% of commercial whole wheat flour can be classified as 100% whole wheat flour. Conclusions: This study provides a nutritional quality cut-off point for Chinese commercial whole wheat flours, indicating a notable variation in ARs content and identifying a substantial proportion that falls short of the established nutritional cut-off point.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Calculation of the ARs Cut-Off Point for Whole Wheat Flour

2.1.1. ARs Levels in Wheat Grains Samples

2.1.2. ARs Content in Wheat Grains Reported in Other Studies

2.1.3. Calculation of the ARs Cut-Off Point

2.2. ARs Levels in Commercial Whole Wheat Flour and Application of ARs Cut-Off Point

2.2.1. ARs Levels in Commercial Whole Wheat Flour Samples

2.2.2. Application of ARs Cut-Off Point

2.3. Chemicals and Reagents

2.4. Extraction and Analysis of Alkylresorcinols

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

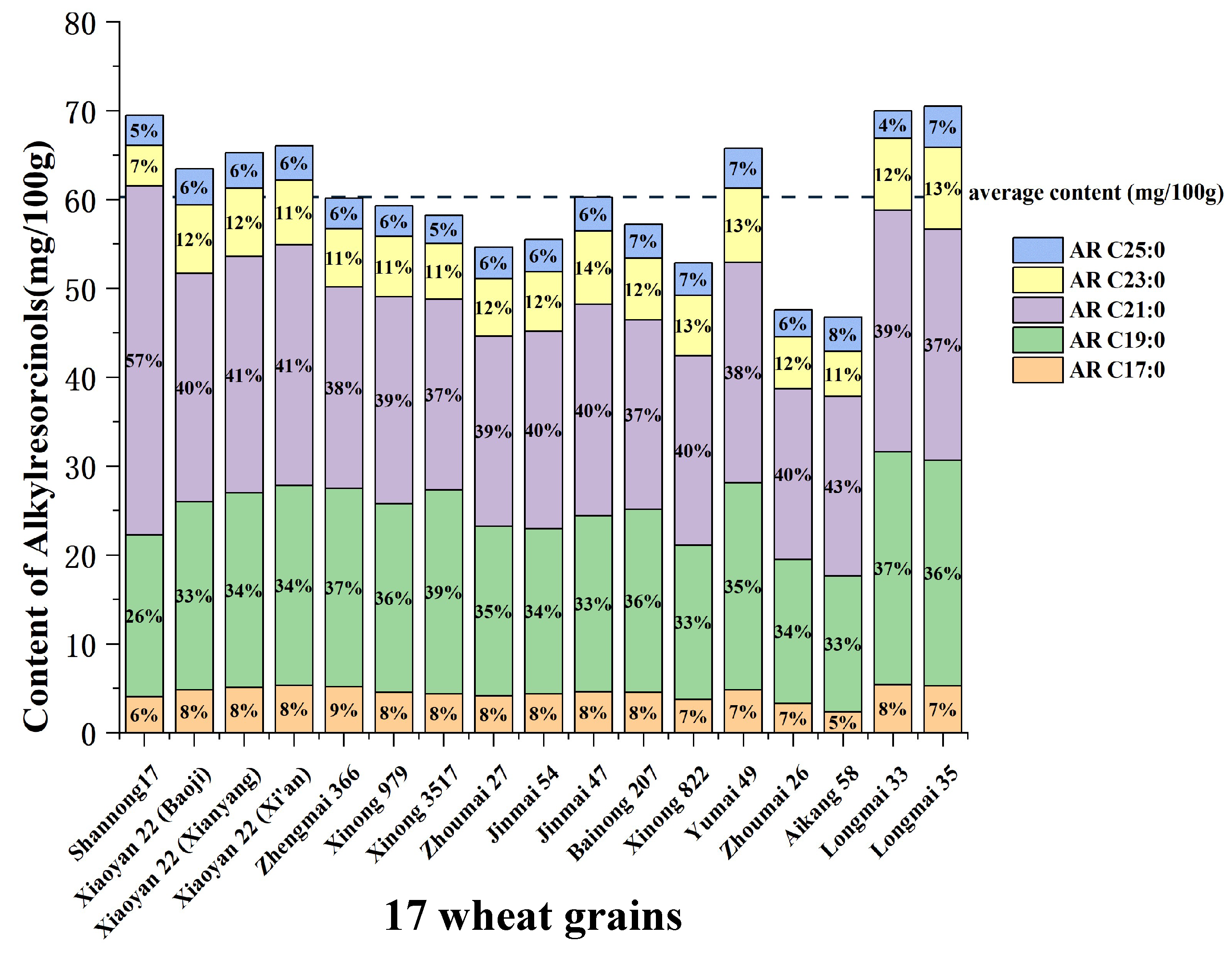

3.1. ARs Levels in 17 Wheat Grains of China

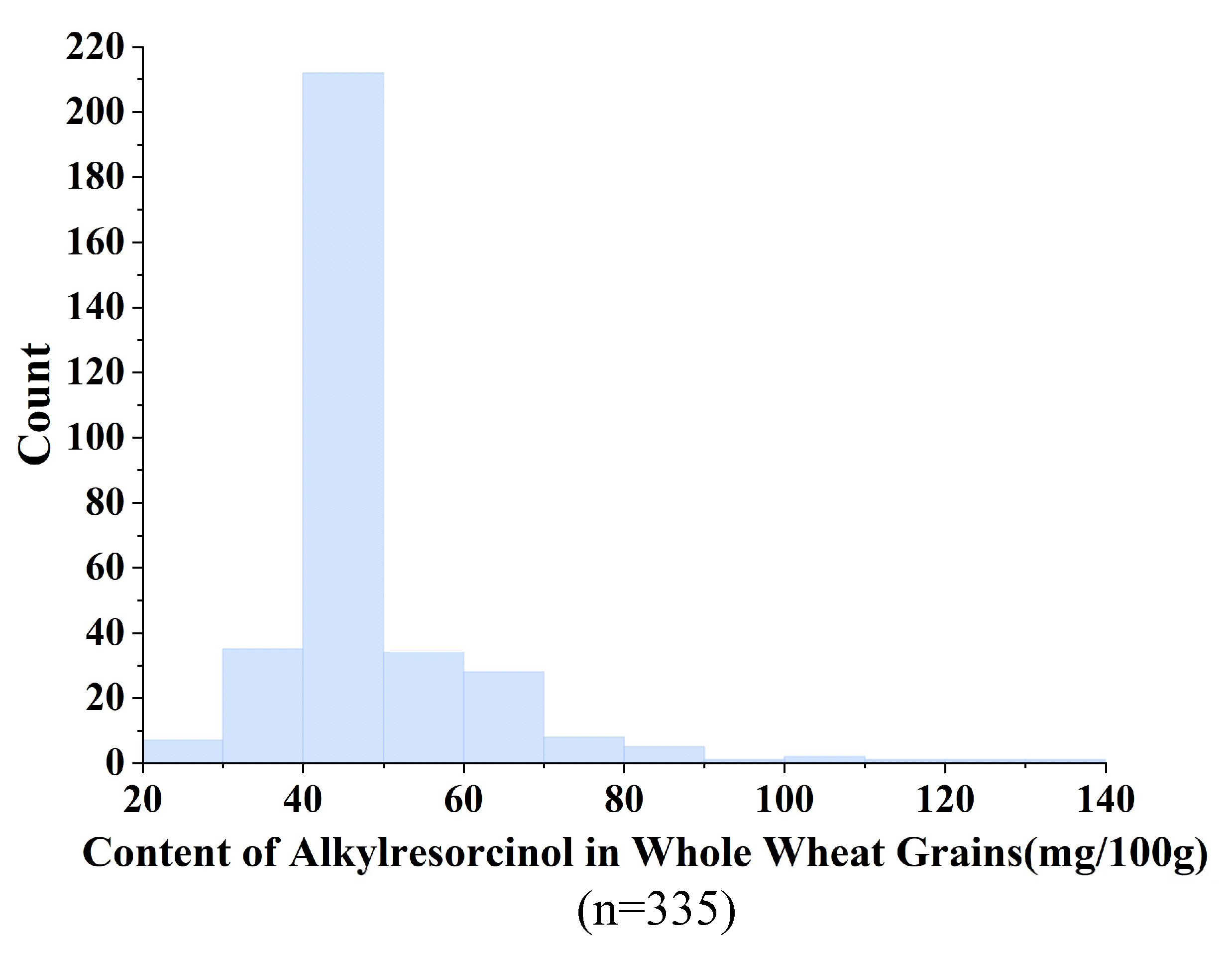

3.2. Calculation of the Cut-Off Point of ARs Content in Whole Wheat Flour

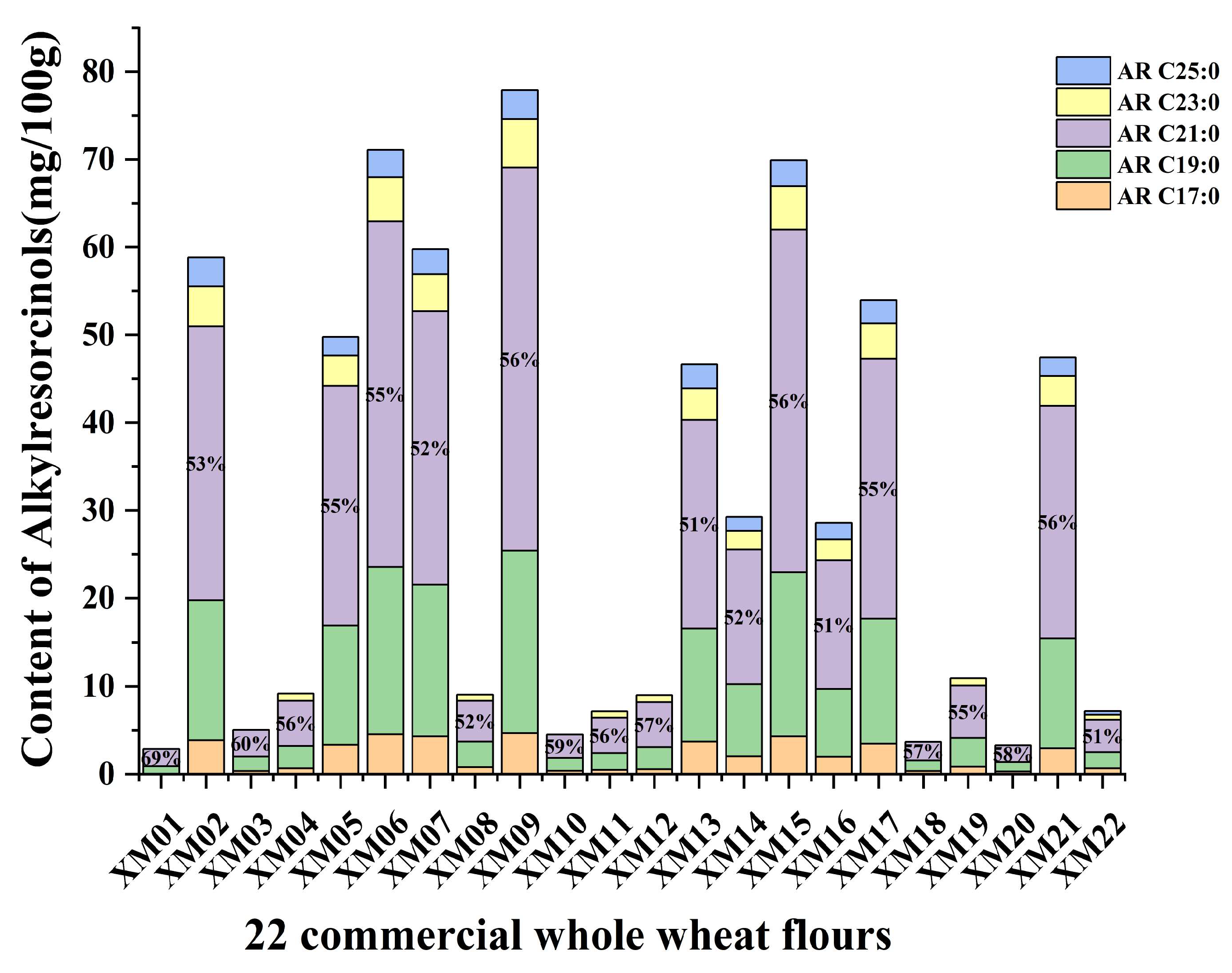

3.3. ARs Levels in Commercial Whole Wheat Flour and Application of ARs Cut-Off Point

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borneo, R.; León, A.E. Whole grain cereals: functional components and health benefits. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Sang, S. Phytochemicals in whole grain wheat and their health-promoting effects. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017, 61, 10.1002–mnfr.201600852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P J. ; Fay, K. A. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P.; Greenwood, D.C.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Riboli, E.; Norat, T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Bmj (Online) 2016, 353, i2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, S.; Mann, J.; Neumann, S.; Ross, A.B.; Reynolds, A.N. Whole-Grain Processing and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A. New hypotheses for the health-protective mechanisms of whole-grain cereals: what is beyond fibre? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 65–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgaramella, N.; Nigro, D.; Pasqualone, A.; Signorile, M.A.; Laddomada, B.; Sonnante, G.; Blanco, E.; Simeone, R.; Blanco, A. Genetic Mapping of Flavonoid Grain Pigments in Durum Wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschick, T.; Wagner, T.; Vetter, W. Countercurrent chromatographic fractionation followed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry identification of alkylresorcinols in rye. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 8417–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Aman, P. Dietary alkylresorcinols: absorption, bioactivities, and possible use as biomarkers of whole-grain wheat- and rye-rich foods. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Shepherd, M.J.; Schüpphaus, M.; Sinclair, V.; Alfaro, B.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Åman, P. Alkylresorcinols in Cereals and Cereal Products. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2003, 51, 4111–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ross, A.B.; Åman, P.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Alkylresorcinols as Markers of Whole Grain Wheat and Rye in Cereal Products. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2004, 52, 8242–8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- W. Ben; L. Yan; Q. Haifeng; Z. Hui; Q. Xiguang; W. Li. Overview of Research on Biomarkers in Whole Grains. Journal of the Chinese Cereals and Oils Association 2022, 37, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- W. Yu-fei. Methods for Determination and Application of Alkylresorcinols in Wheat Grain or Plasma. Beijing: Institute for Nutrition and Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018.

- Z. Yuan-pei. Wheat Growing Regions and Flourmills Relocation in China. Grain Processing 2005, 30, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- W. Yu-fei; Z. Xue-song; X. Xue-song; G. Chao; W. Zhu. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE LIQUID FLUOROMETRIC METHOD FOR DETERMINATION OF ALKYLRESORCINOLS IN WHOLE WHEAT. Acta Nutrimenta Sinica 2018, 40, 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- X. Feiyang. Effect of moderate peeling on nutritional quality and storage stability of wheat flour, Food Science and Engineering Northwest A&F University,2023.

- Landberg, R.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Andersson, R.; Åman, P. Alkylresorcinol Content and Homologue Composition in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum) Kernels and Pasta Products. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2006, 54, 3012–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengtrakul, P.; Lorenz, K.; Mathias, M. Alkylresorcinols in U.S. and Canadian wheats and flours. Cereal Chem. 1990, 67, 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, A.A.M.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Fraś, A.; Boros, D.; Åman, P. Alkylresorcinols in Wheat Varieties in the HEALTHGRAIN Diversity Screen. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2008, 56, 9722–9725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawinek, M.; Jaromin, A.; Kozubek, A.; Zarnowski, R. Alkylresorcinols in Selected Polish Rye and Wheat Cereals and Whole-Grain Cereal Products. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2008, 56, 7236–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzani, C.; Vanara, F.; Bhandari, D.R.; Bruni, R.; Spengler, B.; Blandino, M.; Righetti, L. 5-n-Alkylresorcinol Profiles in Different Cultivars of Einkorn, Emmer, Spelt, Common Wheat, and Tritordeum. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2021, 69, 14092–14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, M.; Magnusdottir, O.K.; Rosqvist, F.; Cloetens, L.; Landberg, R.; Kolehmainen, M.; Brader, L.; Hermansen, K.; Poutanen, K.S.; Herzig, K.; Hukkanen, J.; Savolainen, M.J.; Dragsted, L.O.; Schwab, U.; Paananen, J.; Uusitupa, M.; Åkesson, B.; Thorsdottir, I.; Risérus, U. A Dietary Biomarker Approach Captures Compliance and Cardiometabolic Effects of a Healthy Nordic Diet in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome. The Journal of Nutrition 2014, 144, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.B.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Lundin, E.A.; Zhang, J.X.; Hallmans, G.; Aman, P. Cereal alkylresorcinols are absorbed by humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2222–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. Enjun; X. Yulin; Y.U. Shuang. RESEARCH PROGRESS OF WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR PROCESSING TECHNOLOGY. Journal of Henan University of Technology(Natural Science Edition) 2016, 37, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Jingjie; S. Yue; H. Hanxue. Research Progress in Whole Wheat Flour and Whole Wheat Food. Food Research and Development 2024, 45, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- C. Xiyu; L. Zhen; D. Ying; H. Yang; H. Chenwei; L. Bo. Research progress on key technologies of whole wheat flour processing based on back-blending method. Modern Flour Milling Industry 2023, 37, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Xin; R. Chengang; C. Jiajia; Y. Weizu. Main Milling Processes of Whole Wheat Flour and Their Merits and Demerits Analysis. Cereals and Oils Processing (Electronic Version), -57.

- Y. Siqi; W. Fengcheng; X. Yanan; L.I. Jianhua. A Comparative Study on the Quality of Different Grinding Size Whole Wheat Flour Produced by Entire Grain Process and Bran Recombining Process. Food Sci. Technol.

- Y.Y. Yang. Research on Hygiene, Storage and Processing Quality Improvement Technology of Reconstituted Whole Wheat Flour, Jiangsu University, 2021.

- Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, Z. Non-Destructive Determination of Alkylresorcinol (ARs) Content on Wheat Seed Surfaces and Prediction of ARs Content in Whole-Grain Flour. Molecules 2019, 24, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korycińska, M.; Czelna, K.; Jaromin, A.; Kozubek, A. Antioxidant activity of rye bran alkylresorcinols and extracts from whole-grain cereal products. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliwa, J.; Gunenc, A.; Ames, N.; Willmore, W.G.; Hosseinian, F.S. Antioxidant activity of alkylresorcinols from rye bran and their protective effects on cell viability of PC-12 AC cells. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011, 59, 11473–11482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, A.S.; Coupland, J.N.; Elias, R.J. Antioxidant activity of a winterized, acetonic rye bran extract containing alkylresorcinols in oil-in-water emulsions. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Yiming; Y. Zihui; L. Jie; W. Ziyuan; W. Jing. Protective Effect and Mechanism of Wheat Alkylresorcinols on Insulin Resistance in 3 T3-L1 Adipocytes. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2021, 39, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- G. Yazhou; Y. Xiaoming; L.I. Yueying. Alkylresorcinols from Wheat Bran Induced Autophagy and Apoptosis of HepG2 Cells. Food Science 2020, 41, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- C. Yang; H. Li; H. Li; Y. Wang; L. Meng; Y. Yang. Mechanism study of 5-alkylresorcinols-induced colon cancer cell apoptosis in vitro. World Chinese Journal of Digestology 2017, 25, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Mingsi; L. Jie; Z. Kexue; S. Baoguo; W. Jing. Anti﹣Proliferative Effect of 5﹣Heptadecylresorcinol on MDA﹣MB﹣231 Triple﹣Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2019, 37, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Conklin, D.R.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Sang, S. 5-Alk(en)ylresorcinols as the major active components in wheat bran inhibit human colon cancer cell growth. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 3973–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Winter, K.M.; Stevenson, L.; Morris, C.; Leach, D.N. Wheat bran lipophilic compounds with in vitro anticancer effects. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbini, L.; Lopez, P.; Ruffa, J.; Martino, V.; Ferraro, G.; Campos, R.; Cavallaro, L. Induction of apoptosis on human hepatocarcinoma cell lines by an alkyl resorcinol isolated from Lithraea molleoides. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 5959–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Jie; W. Yu; W. Ziyuan; W. Jing. Whole cereal grains and potential health effects:neuroprotective mechanism of dietary 5-heptadecylresorcinol. 17th Annual Meeting of CIFST; 2020; Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China; 2020. p. 2.

- Z. Yanyu. PREPARATION AND ANALYSIS OF WHEAT ALKYLRESORCINOL AND ITS PROTECTIVE EFFECT ON OXIDATIVE GAMAGED HT22 CELLS: Nanjing University of Finance and Economics; 2020.

- Patzke, H.; Zimdars, S.; Schulze-Kaysers, N.; Schieber, A. Growth suppression of Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium poae and Fusarium graminearum by 5-n-alk(en)ylresorcinols from wheat and rye bran. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, E.S.; Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Nybom, H.; Tahir, I. Alkylresorcinols isolated from rye bran by supercritical fluid of carbon dioxide and suspended in a food-grade emulsion show activity against Penicillium expansum on apples. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2013, 46, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| country | n | range of total ARs content (mg/100g of DM) | references |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 2 | 103.6、107.3 | Feiyang Xiong [13] |

| Sweden | 32 | 22.7~63.9 | Chen Y [8] |

| Sweden | 3 | 48.9~64.2 | Ross A B [7] |

| Austria, France, Kazakhstan, Russia, Spain, Sweden |

21 | 25.1~61.8 | Landberg R [14] |

| United States 、Canada | 59 | 30.8~65.5 | Hengtrakul P [15] |

| Hungary | 176 | 41.0~60.5 | Andersson A A M [16] |

| Poland | 10 | 56.5~87.9 | Kulawinek M [17] |

| Italian | 15 | 73.7~133.3 | Pedrazzani C [18] |

| ID | ARs | Total ARs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C17:0 | C19:0 | C21:0 | C23:0 | C25:0 | ||

| XM01 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| XM02 | 3.9 | 15.9 | 31.2 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 58.8 |

| XM03 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| XM04 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 9.2 |

| XM05 | 3.3 | 13.6 | 27.3 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 49.8 |

| XM06 | 4.6 | 19.0 | 39.4 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 71.1 |

| XM07 | 4.3 | 17.2 | 31.2 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 59.8 |

| XM08 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 9.1 |

| XM09 | 4.7 | 20.7 | 43.7 | 5.5 | 3.3 | 77.9 |

| XM10 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| XM11 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 7.2 |

| XM12 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 9.0 |

| XM13 | 3.7 | 12.9 | 23.7 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 46.7 |

| XM14 | 2.0 | 8.2 | 15.3 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 29.3 |

| XM15 | 4.3 | 18.7 | 39.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 69.9 |

| XM16 | 2.0 | 7.7 | 14.6 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 28.6 |

| XM17 | 3.5 | 14.2 | 29.6 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 54.0 |

| XM18 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 |

| XM19 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 10.9 |

| XM20 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 |

| XM21 | 2.9 | 12.5 | 26.4 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 47.4 |

| XM22 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 7.2 |

| median | 1.4 | 5.5 | 10.3 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 19.8 |

| quartile | (0.5,3.7) | (1.8,14.2) | (3.7,29.6) | (0.6,4.0) | (0.0,2.8) | (7.2,54.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).