1. Introduction

The rail system is usually the first choice for travelling in people’s daily life because of its punctuality and convenience. Taking the passenger flow of the Shenzhen Metro’s urban rail transport in China as an example, the Automatic Fare Collection (AFC) system recorded over 140 million transactions over a period of 48 days [

1]. At the same time, the maximum number of trains running on weekdays is nearly Seven Thousand. If the timetable is planned appropriately while still satisfying passenger demand, significant unnecessary costs will be minimized [

2].

Passenger demand in the railway system is characterized by spatial and temporal imbalance. Therefore, many researchers have studied the train scheduling process in the impact of passenger demand. From the perspective of time-dependent passenger demand, a variable train composition method was implemented [

3,

4]. Moreover, a non-fixed headway between two consecutive trains is achieved, which is able to face the passenger demand that varies with the peak and off-peak hours [

7,

8]. Based on current research focus, spatial passenger demand can be categorized into two types: passenger flow demand at different stations and passenger flow demand in different directions. When there is frequent congestion at certain stations, implementing skip-stop strategy and appropriate stopping scheme can effectively alleviate platform congestion [

5,

6,

9,

12]. In addition, the express/local train operation strategy (ELS) is also a common approach to solve the problem of station congestion [

13,

14]. The ELS can speed up the cycle running time by the skip-stop behavior of express trains, and also ensure that passengers waiting on the platform can board the trains smoothly by the all-stop behavior of local trains. Due to urban development, passenger flow in the commercial center stations far exceeds that in other stations. The short-turning strategy is adopted to increase the number of trains running in the commercial center section [

8,

10]. The above studies are about the imbalance of passenger flow at stations, and it is worth noting that the passenger flow imbalance in the direction is often caused by the tidal passenger flow phenomenon [

11]. However, studies on passenger flow imbalance in the direction are minimal.

According to passenger travel patterns during morning peak hours, the number of people traveling from the suburbs to the city center is significantly higher than those traveling in the opposite direction. However, during the evening rush hour, many people who work and study near the city center return to their suburban homes, resulting in the tidal passenger flow phenomenon [

15]. To cope with the problem, this paper proposes the train unpaired operation strategy (TUOS), i.e., the number of trains running in both directions is not the same. Compared to the traditional train paired operation strategy (T-TPOS) [

3,

16,

17], the TUOS improves the matching of passenger numbers and train capacity by flexibly determining the number of trains in both directions.

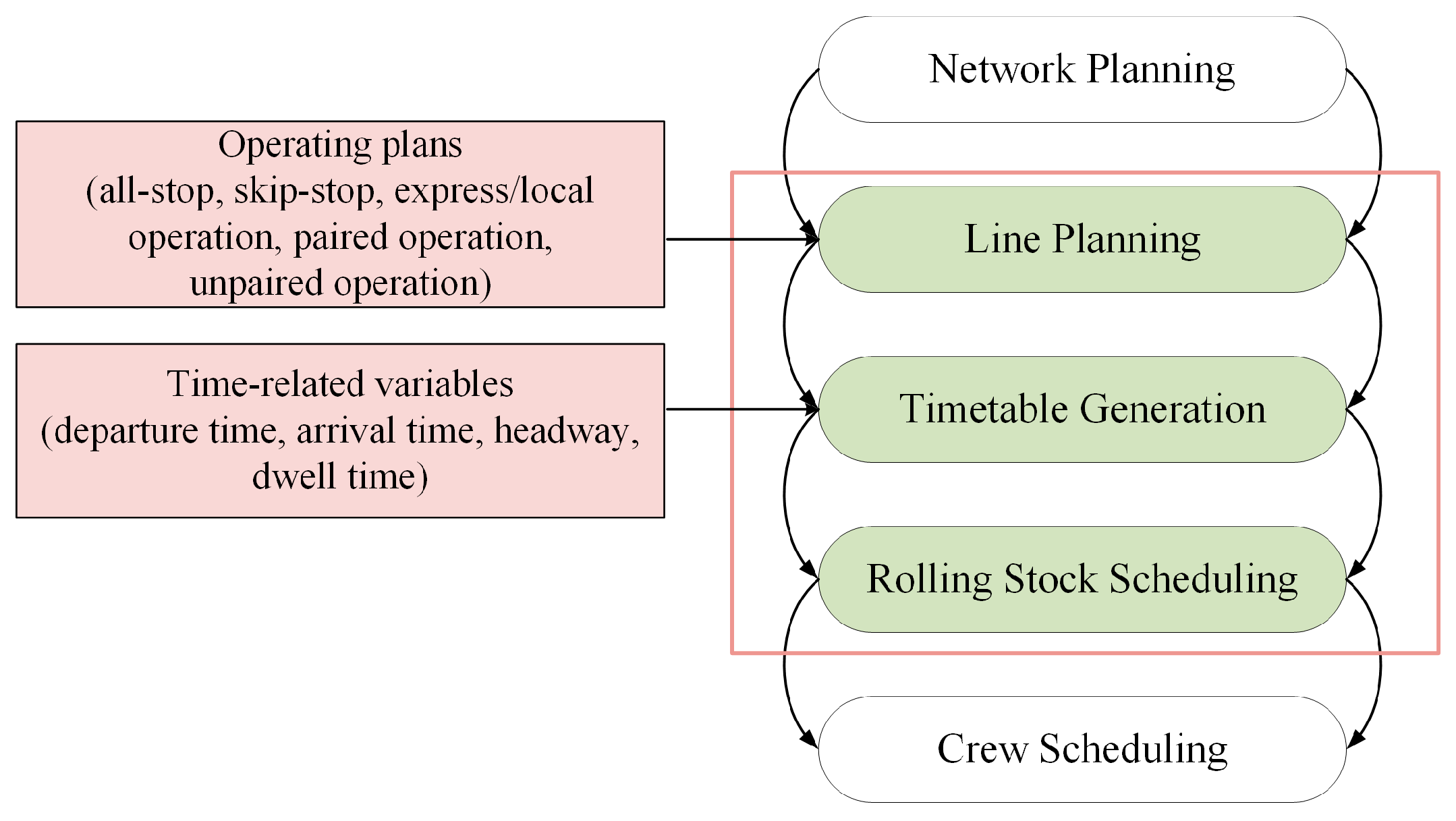

The above discussed is the Line Planning level of the rail transport planning process [

20]. As shown in

Figure 1, after the Line Planning level, the Timetable Generation level should be entered. In other words, the Timetable Generation level is the confirmation of train departure time, arrival time, headway and dwell time. Timetable optimization considering rolling stock scheduling is the focus of current research, which takes into account the quality of passenger service as well as the cost of operating the train [

17,

18]. Therefore, this paper selects three processes in the rail transport planning process for research, which are Line Planning level, Timetable Generation level and Rolling Stock Scheduling level.

Usually, timetable optimization is conducted with the objective of improving passenger service quality and reducing operating costs. passenger service quality is generally defined as total passenger waiting time [

19], total passenger travel time [

11,

21], number of stranded passengers [

20], etc. The operator's operating costs include train operating expenses and train stopping expenses.

So far, few studies have focused on the TUOS. Compared to TUOS, the T-TPOS offers significant advantages in transport organization, but it can lead to a waste of resources due to the lack of passengers in a certain direction in the face of tidal passenger flow scenario. Therefore, we use the tidal passenger flow phenomenon as a background to achieve optimization of timetable. It is noteworthy that the TUOS allows for a flexible allocation of trains in both directions, whereas the ELS can manage stopping schemes and accelerate the cycle running time of train. Therefore, this paper selects the combined strategies of unpaired operation and express/local train operation, abbreviated as the TUOS-ELS.

This paper considers three planning processes of the rail transport planning process, namely line planning level, timetable generation level and rolling stock scheduling level. A multi-strategy optimization method is developed, which will contribute to the future development of rail transit systems The highlights of this paper are as follows:

1. A multi-strategy optimization method (TUOS-ELS) has been proposed, which mainly consists of the train unpaired operation strategy (TUOS) and the express/local operation strategy (ELS). And rolling stock circulation is also considered.

2. The nonlinear model related to timetable and passenger flow is linearized, and the mixed integer linear programming model (MILP) is constructed. According to the actual train operation process, the optimization algorithm framework is designed, and the GUROBI solver are used to solve the optimization problem.

3. Based on shanghai suburban railway airport link line, the timetable optimization under different passenger flow scenarios is investigated, and the optimization results of the TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS are compared.

2. Problem Description

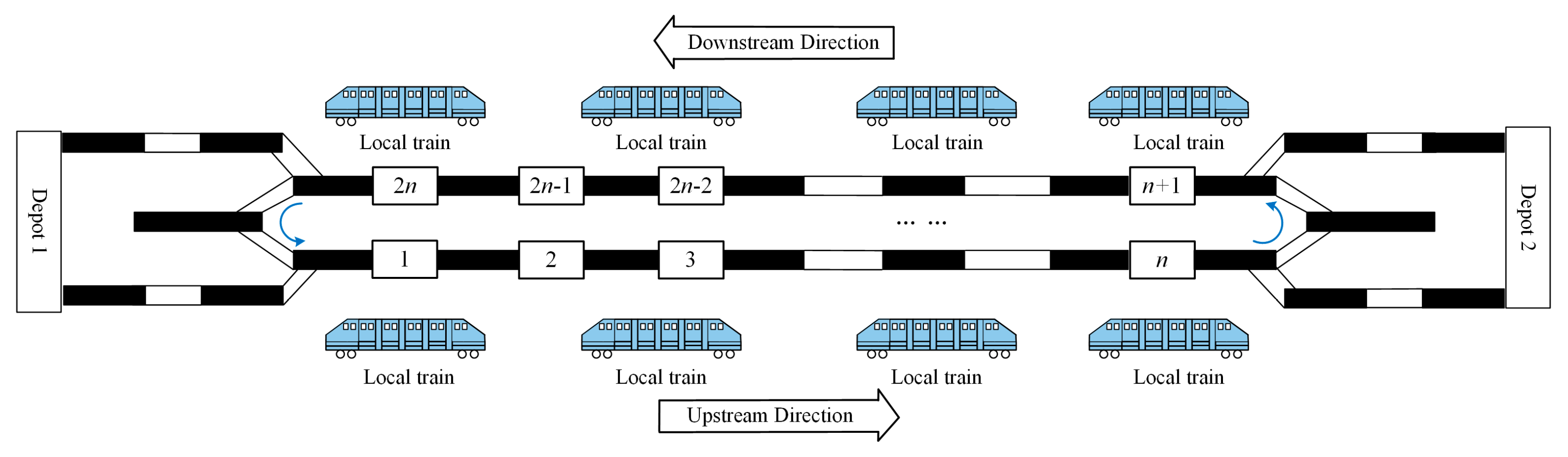

A crowded radioactive railway line linking the city center to the suburb is studied in this paper, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

S is used to represent the stations where the train will perform the task of loading passengers, i.e.,

.

In

Figure 2, it is obvious that the number of trains running in both directions is the same which is called the T-TPOS. The T-TPOS embodies the advantages of simple and easy to realize, but it also has many shortcomings when dealing with the problems caused by tidal passenger flow. If T-TPOS is implemented on tidal passenger flow lines, the total train capacities in the upstream direction (i.e. the main passenger flow direction) will not be able to meet the passengers demand, and will lead to waste of train utilization in the downstream direction (i.e. the non-main passenger flow direction).

In order to solve the problem of uneven distribution of passenger numbers in the direction, the timetable optimization based on the TUOS-ELS is studied to enhance the matching between train capacity and passenger demand. In

Figure 2, the total number of trains running in both directions is 8. With the same total number of trains running, the TUOS-ELS in

Figure 3 is adopted, where 5 trains operate closely in the upstream direction and 3 trains operate more sparsely in the downstream direction. The flexible number of trains and headway between two consecutive trains can accommodate uneven passenger demand. In addition, the determination of the number of trains plays an important role. The ELS is executed in the downstream direction and the express trains can shorten the travel time from the first station to the terminal station. However, there are local trains running in both directions with all-stop behavior to ensure service quality. All-stop behavior means that the train stops at every station it passes through.

This paper considers both passenger service quality and operating costs. When passengers wait on the platform, they only care about whether they can board the upcoming train and their travel time. Therefore, the number of stranded passengers on the platform and travel time of trains were chosen as indicators for service quality. The stopping costs were selected as operating costs. Therefore, the multi-objective optimal solution is obtained by considering the number of trains, headway, departure time and arrival time as decision variables.

This paper focuses on the study of the timetable optimization. The number of trains, the running time between stations, the dwell time, the departure time and the passenger’s traveling behavior are considered. To simplify the model, the proposed assumptions are illustrated as follows:

Assumption 1. Urban rail lines do not provide siding, do not support temporary train additions and subtractions, and do not support overtaking operations at any location on the line.

Assumption 2. Passengers can be informed of stations where the upcoming train will not stop through their mobile devices as well as platform announcements. Passengers may only travel on trains that are valid for them, i.e., trains that stop at both the passenger’s origin and destination, and that do not take into account the passenger’s transfer behavior.

Assumption 3. To simplify the passenger waiting model, it is assumed that the waiting passengers of different OD (Origin-Destination) pairs are mixed at the platform. When the train reaches the platform, the number of the stranded passengers are random.

3. Mathematical Modeling

In this section, due to the necessity to clearly indicate the relationship between timetable, passengers boarding and alighting behavior, train traffic dynamic model and passenger flow model are developed and detailed conceptual descriptions are given. A MILP model is constructed by linearizing the non-linear components, which facilitates an accurate solution to the problem.

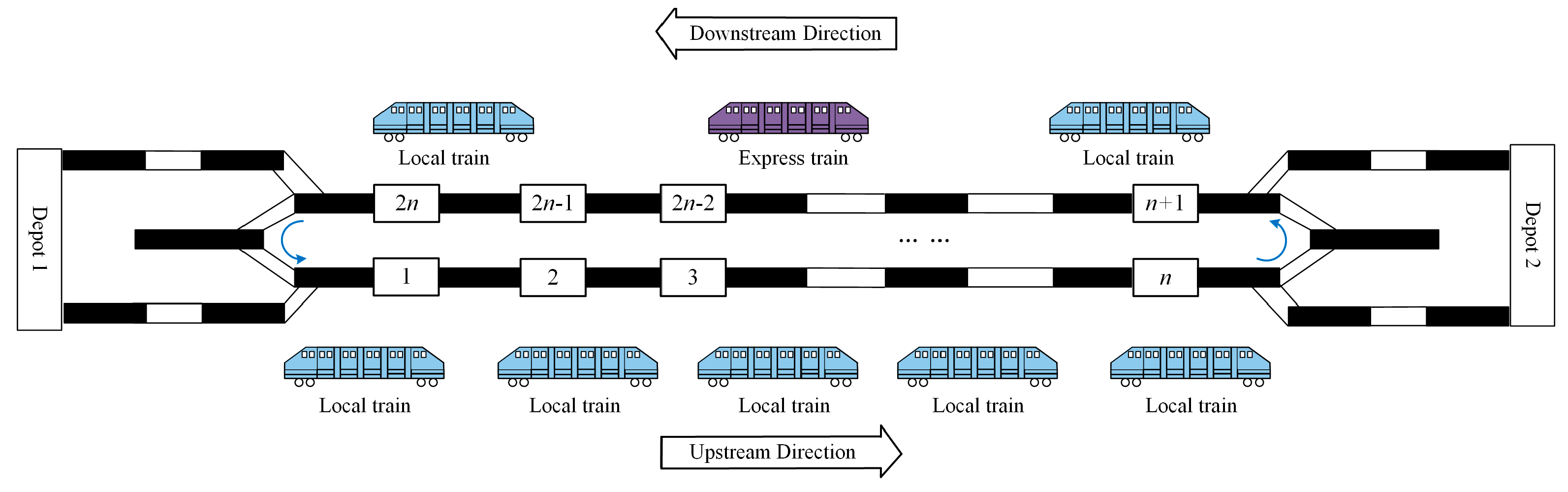

3.1. Train Traffic Dynamic Model

The headway

between two consecutive trains

i and

i-1 determines the number of waiting passengers on the platform. Setting an appropriate headway will avoid the number of waiting passengers in excess of the available platform capacity during peak periods and solve the problem of wasted trains capacity.

where

and

are the maximum and minimum headway, respectively.

I is the set of train serial numbers in both directions, and the number of trains running is determined by the number of passengers.

and

are the total number of trains running in the upstream and downstream directions respectively.

It should be clear how the number of trains is determined. The minimum number of trains

is obtained based on the ratio of the expected maximum number of on-board passengers. The expected maximum number of on-board passengers is calculated with the maximum headway and train capacity

C is assumed to be infinite. And the minimum number of trains during the study period

should also satisfy the maximum headway constraint, as shown in Eq. (2). After that, the maximum number of trains can be known by the minimum headway, as shown in Eq. (3).

where

are the number of on-board passengers of the train

i leaving station

s. After obtaining the maximum/minimum number of trains in both directions, upper and lower bound constraints on the actual number of trains can be acquired, i.e.,

.

The departure time

of train

i at station

s is related to the arrival time

and dwell time

, where the arrival time

is composed of the departure time

at the previous station

s-1 and the running time

from station

s-1 to station

s of train

i , as shown in

Figure 4.

where

indicates whether the train

i stops at station

s. If the train

i stops at station

s,

, otherwise

.

,

are the minimum dwell time and maximum dwell time of the train

i at station

s.

are the minimum running time and maximum running time of the train

i from station

s-1 to station

s.

In order to guarantee the service quality, this paper specifies two train skip-stop behaviors. On the one hand, when three consecutive trains pass the same station

s, at least two trains stop at station

s, i.e., three consecutive trains are not allowed to skip the same station. On the other hand, a train cannot skip three consecutive stations.

In

Figure 4, the time constraints are more clearly reflected. Considering an example involving three trains across four stations, train

i-1 skips station 3, train

i chooses to stop at all stations, and train

i+1 skips station 2.

Since the safe operation of trains is very important, the departure time of train

i at station 3 and the arrival time of train

i+1 at station 3 should satisfy the "departure-arrival" time constraint

, i.e., the first constraint in Eq. (10); the departure time of train

i at station 2 and the arrival time of train

i+1 at station 2 should satisfy the "departure-passing" time constraint

, i.e., the third constraint in Eq. (10); the arrival time of train

i at station 3 and the departure time of train

i-1 at station 3 should satisfy the "passing-arrival" time constraint

, i.e., the second constraint in Eq. (10).

The rolling stock operation constraints are mainly reflected in the train connection relationship and the turnaround operation time. A train can be connected to no more than one other train during its operational cycle:

where

,

are binary variables, if the train

i in the upstream direction produces a rolling stock connection with the train

j in the downstream direction, the

is taken as 1, otherwise the

is taken as 0. If the train

j in the downstream direction produces a rolling stock connection with the train

i in the upstream direction, the

is taken as 1, otherwise the

is taken as 0.

Two trains can be connected only if the connecting time between trains meets the minimum turnback time

requirement:

The rolling stock connection affects the number of times rolling stock exits and enters the depot. The fewer times, the lower the operator’s operating costs.

where

are binary variables. If the rolling stock of the train

i and

j doesn’t enter the depot,

and

are 1, otherwise

and

are 0. If the rolling stock of trains

i and

j doesn’t come from the depot,

and

are 1, otherwise

and

are 0.

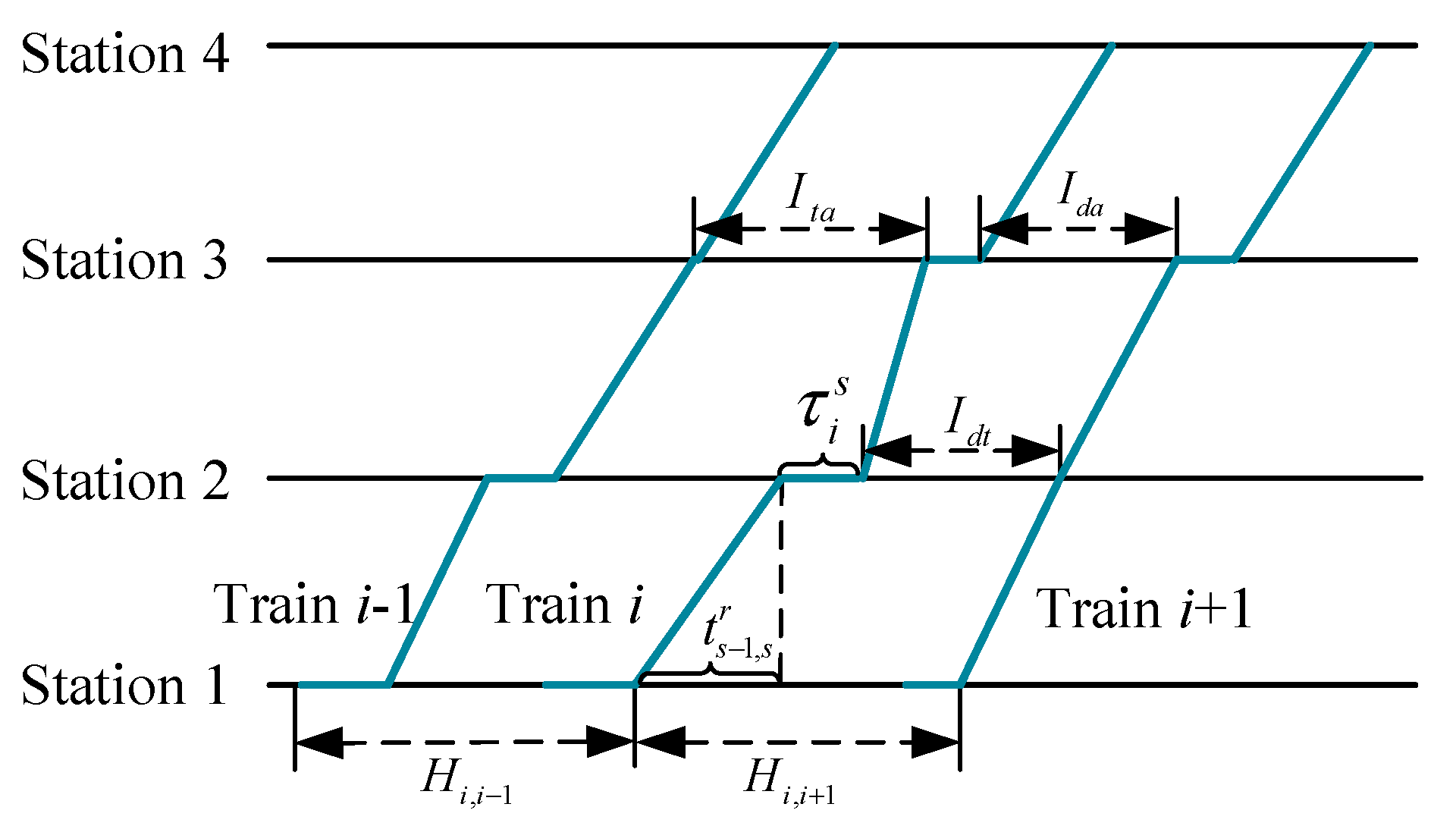

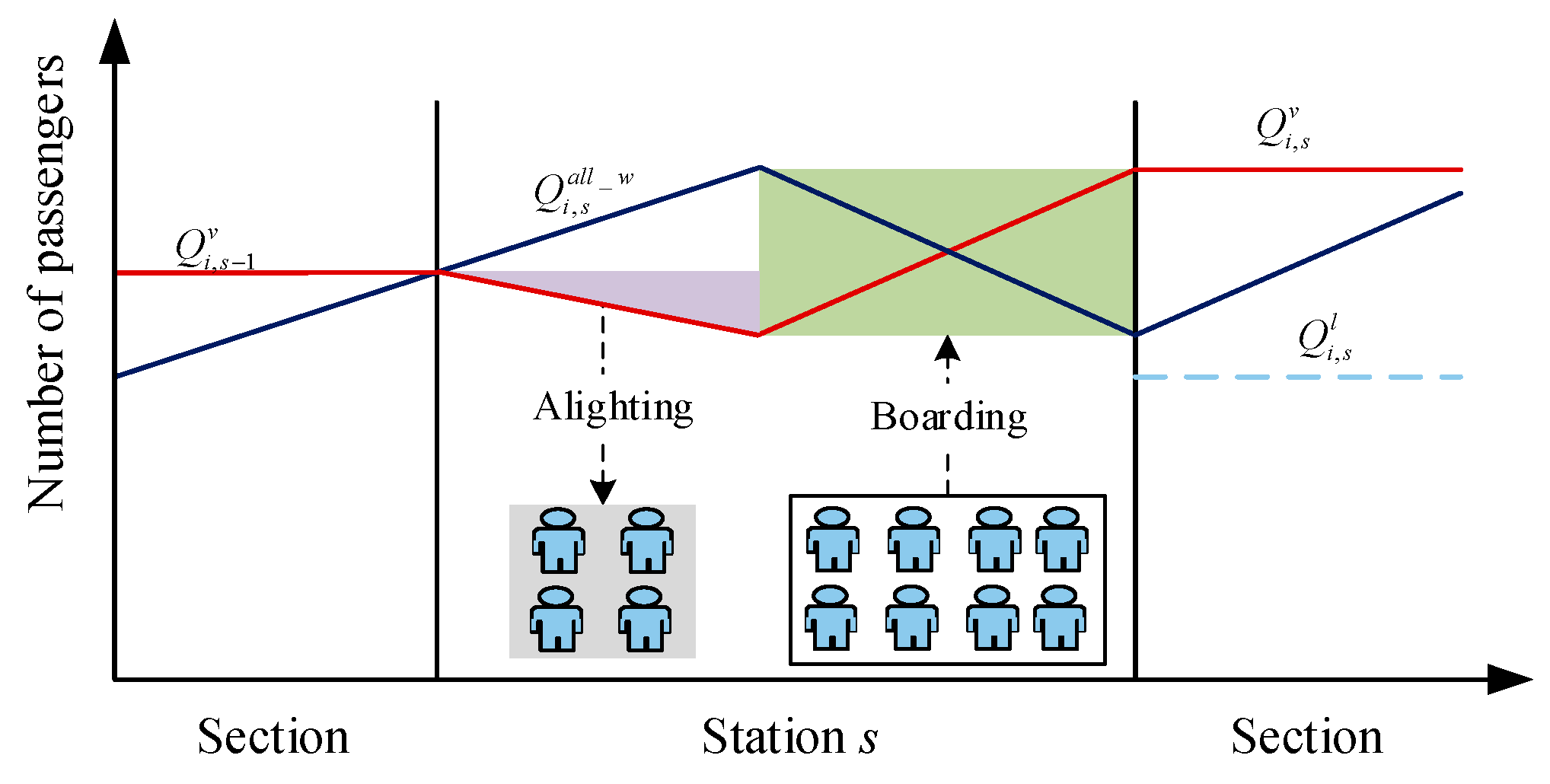

3.2. Passenger Flow Dynamic Model

To illustrate the passenger-station interaction,

Figure 5 was plotted. When a train is running between stations, the number of passengers waiting on the platform increases with the number of new passengers arriving until passenger loading actions take place. However, the number of on-board passengers varies as passengers alight and board.

Taking into account the time-varying passenger demand, it is critical to divide the time interval

to accurately count passenger arrivals. By using the passenger arrival rate

at station

s during the time interval

and the OD arrival ratio matrix

, the number of passengers arriving at station

s going to station

k (

) between the departures of two consecutive trains can be calculated.

The total number of passengers waiting on station

s toward destination

k (

) is the combination of the stranded passengers of the previous train (

) and the newly arriving passengers

.

where

are the total number of passengers waiting for train

i at station

s. Moreover, according to assumption 2, the number of passengers who want to board the train

i at station

s toward destination

k affected by the skip-stop action, i.e., the valid number of passengers waiting

, is described as follows:

where

are the total valid number of passengers waiting for train

i at station

s.

During peak hours, the actual number of passengers boarding the train

i at station

s (

) are related to the number of valid passengers waiting at station

s (

) and the train remaining capacity of train

i at station

s (

). The actual number of passengers alighting at station

s (

) is the total number of passengers who boarded the train

i at other stations before station

s and want to alight at station

s.

By the description of the number of passengers alighting in Eq. (19), it is obvious that the number of passengers successfully boarding train

i from station

s with destination station

k (

) must be obtained. Based on assumption 3, all passengers were mixed on the platform to wait for the train

i, which is consistent with the actual situation. To simplify the calculations, the number of passengers who successfully board the train

i is proportional to the valid number of passengers waiting.

The number of passengers stranded by train

i at station

s who want to travel to station

k (

) is given by the following.

where

is the total number of passengers stranded by train

i on station

s.

3.3. Linearization of the Model

When optimizing timetable, the train traffic dynamic model and passenger flow dynamic model are linearized to build a MILP model. From Eq. (1) and Eq. (4)-(25), it can be found that Eq. (10), Eq. (17), Eq. (22) and Eq. (23) are nonlinear constraints.

Eq. (10) can be rewritten in the following nonlinear constraint form:

Introducing a binary variable

transforms Eq. (26) into Eq. (27):

Similarly, the nonlinear Eq. (17) can be transformed into the following linear constraint form:

The total number of passengers boarding the train

i at station

s is calculated by Eq. (22), and the binary variable

is introduced to represent the relative size relationship between

and

. If

, then

is equal to 1, otherwise

is equal to 0.

Eq. (23) can be converted to the following linear constraint form:

where

is calculated when the train adopts the all-stop behavior as well as fixed headway, dwell time, and running time between stations, i.e.,

.

are the valid number of passengers waiting at station

s who are eager to travel to station

k under the all-stop behavior, and

are the total valid number of passengers waiting at station s under the all-stop behavior.

3.4. Problem Model

Based on the train traffic dynamic model and passenger flow dynamic model, the optimization problem model is established in this paper. Enhancing passenger service quality and reducing operating costs are the objectives in urban rail transport.

The optimization objective function

mainly considers stopping cost, the number of stranded passengers on the platform and total train travelling time in both directions.

where

are cost conversion factors for uniform magnitude. The first parts of the Eq. (31) are used to assess stopping expenses and the last two parts are used to indicate the quality of passenger service.

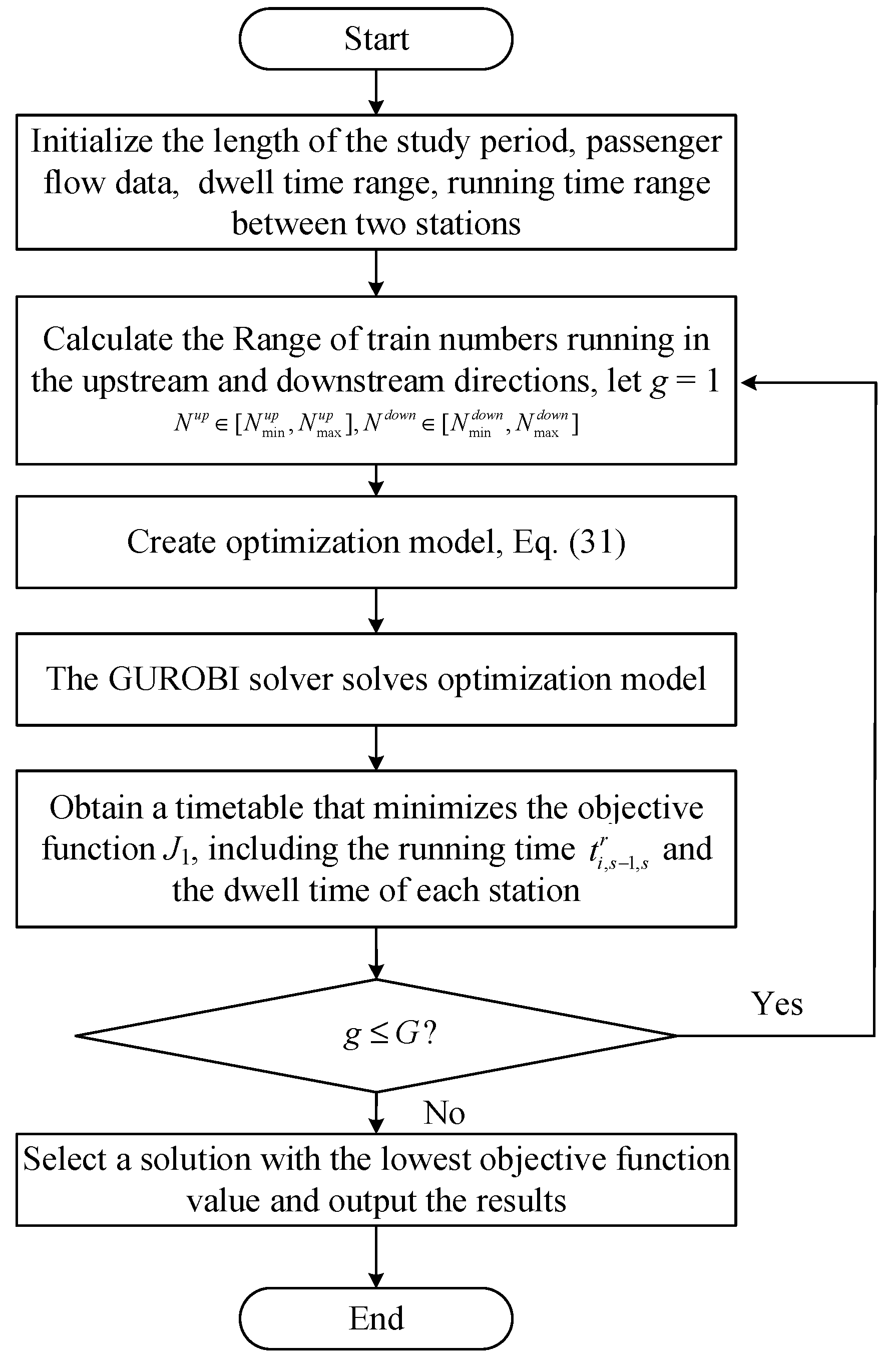

4. Method

The algorithmic framework is taken to solve the optimization model, as shown in

Figure 6. For the timetable optimization model considering passenger flow, which is a MILP model can be solved using the GUROBI solver of MATLAB.

In

Figure 6, the algorithm steps are described. Firstly, the range of the decision variables (the headway, the dwell time and the running time of each train) and the passenger flow data are specified. Secondly, the number of trains running in the upstream and downstream directions is calculated according to Eq. (2) and Eq. (3). And all train number combinations are listed by enumeration, indexed by

g, and

G is the total number of combinations. Then, the timetable is solved according to the objective function

by GUROBI/ MATLAB. Finally, the objective function values are calculated for all train combinations and this result with the lowest objective function value is selected as the optimization result.

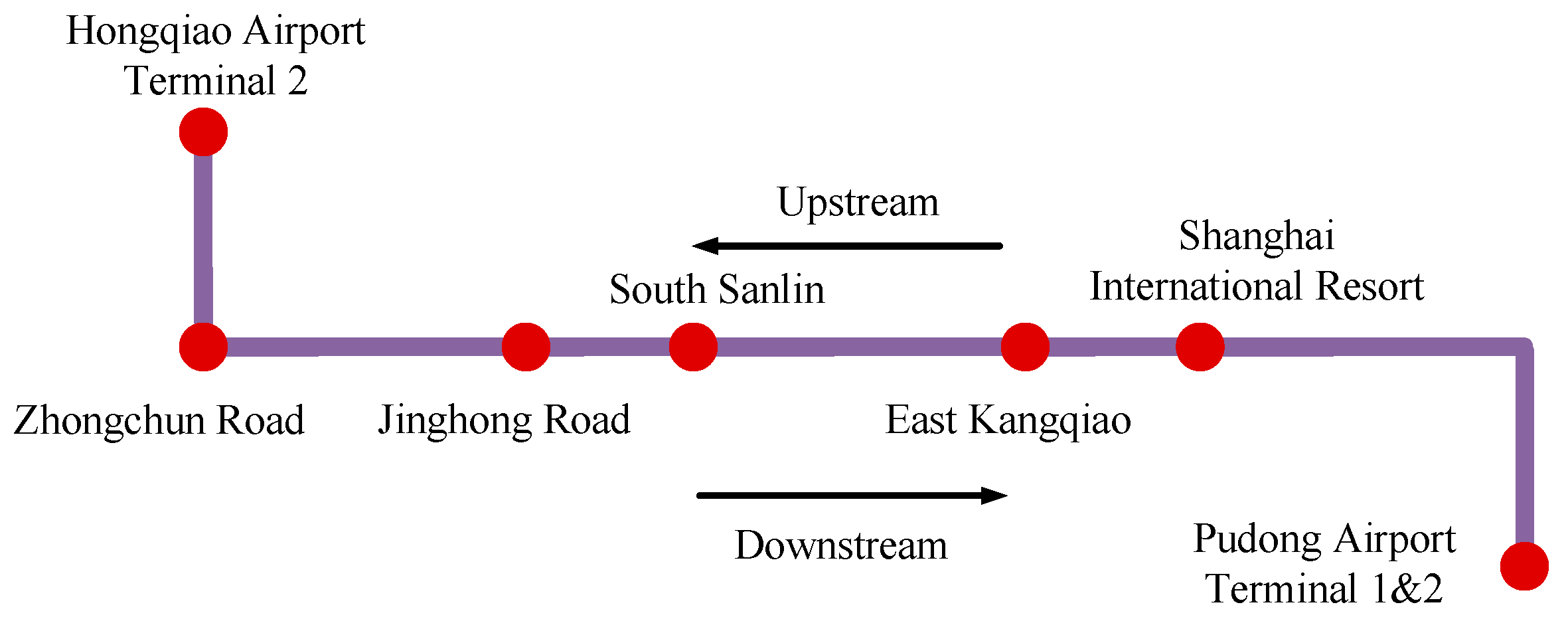

5. Case Study

In this section, simulation analysis is conducted based on the given passenger flow data and actual line data. In this paper, a shanghai suburban railway airport link line containing seven stations and six sections is selected as the research object, as shown in

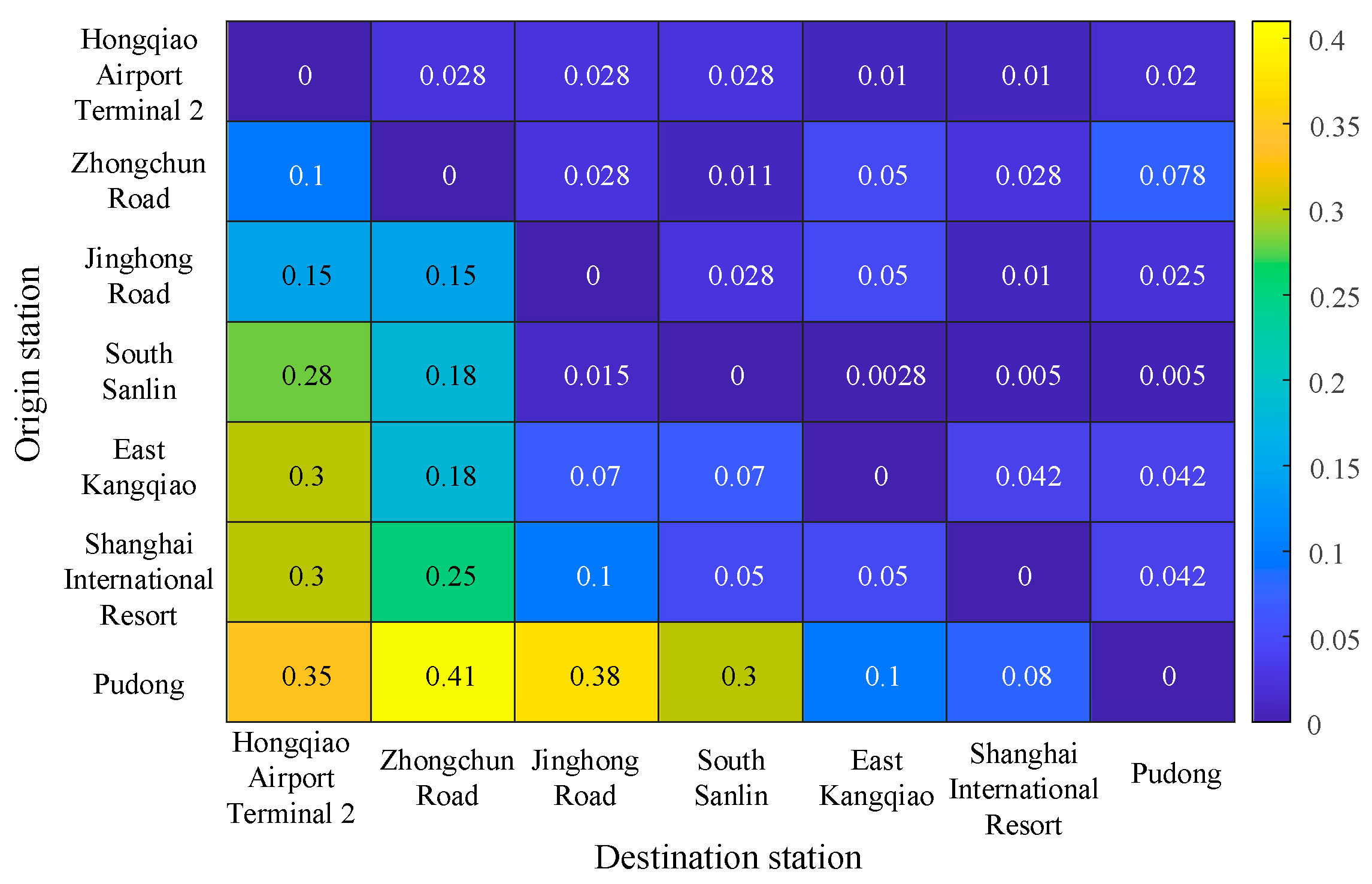

Figure 7. It mainly involves Hongqiao Airport Terminal 2, Zhongchun Road, Jinghong Road, South Sanlin, East Kangqiao, Shanghai International Resort and Pudong Airport Terminal 1&2 stations. Since Pudong Airport Terminal 1&2 is a suburban station and Hongqiao Airport Terminal 2 is an urban station, the number of passengers traveling in the upstream direction far exceeds that in the downstream direction during the morning peak period [8:00, 9:00].

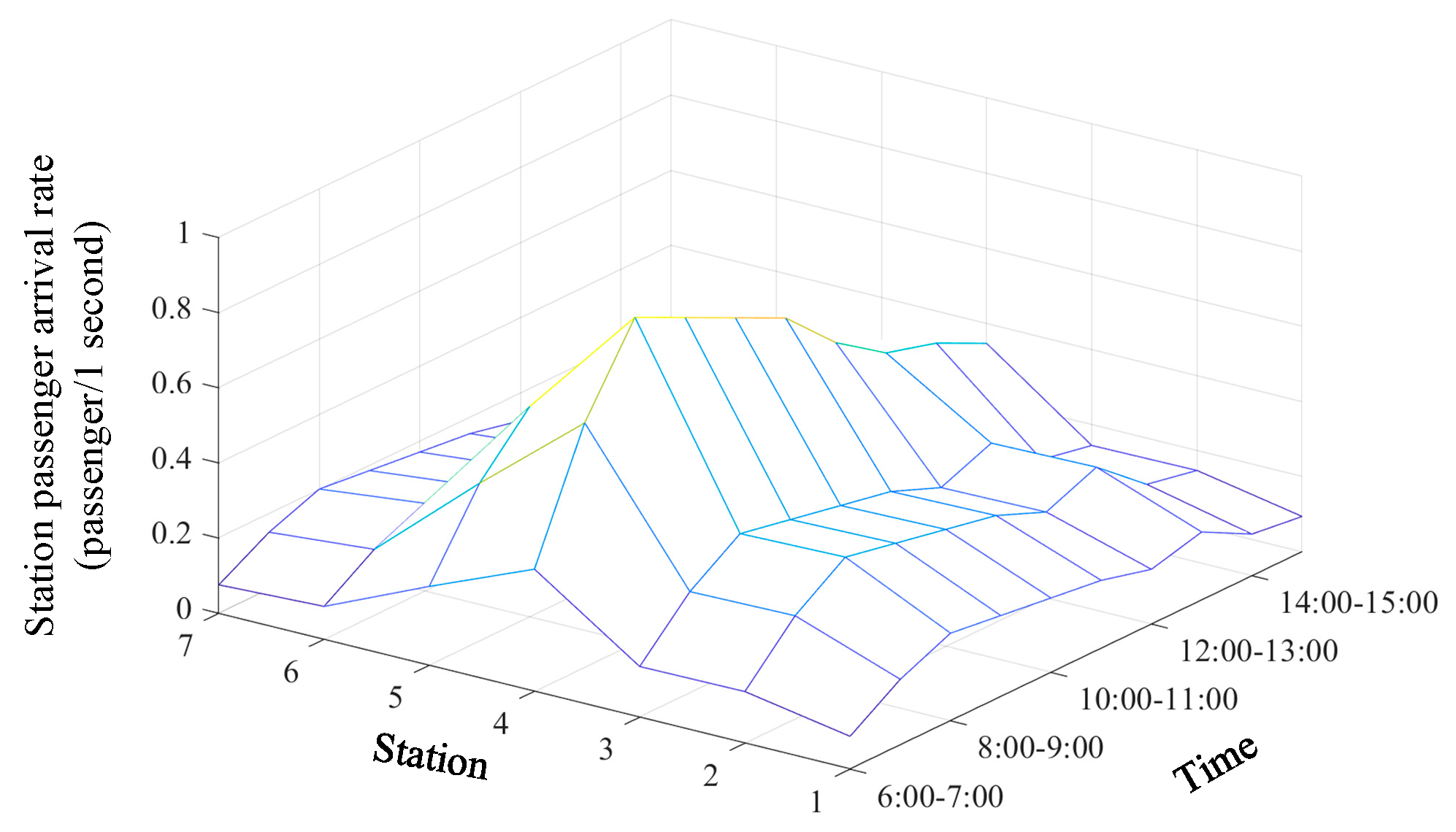

5.1. Simulation Setting

From the time-varying passenger arrival rate at stations shown in

Figure 8, it can be observed that during the period from 6:00 to 9:00, the arrival rate at all platforms increased due to commuting reasons, reaching a peak between 8:00 and 9:00. Before performing the simulation, it is necessary to specify the upper and lower limits of the running time between stations and dwell time. Based on the line data and the distance between two stations, the minimum train running time can be calculated. Additionally, the minimum dwell time limit is specified according to the actual train stopping conditions, as indicated in

Table 1. The remaining time-related parameter settings are shown in

Table 2.

5.2. Optimization of Timetable During Trial Operation

The shanghai suburban railway airport link line is scheduled to initiate trial operations on September 1, 2024, and is expected to be officially operational by the end of 2024. The simulation in this section primarily focuses on optimizing the timetable during the trial operation phase. To demonstrate the validity and accuracy of the proposed model and method, the T-TPOS is compared with the TUOS-ELS. As can be seen from

Figure 9, there is a large difference between the upstream and downstream passenger arrival rates, i.e.,

in Eq. (14). This is a key factor in determining the number of trains running in both directions.

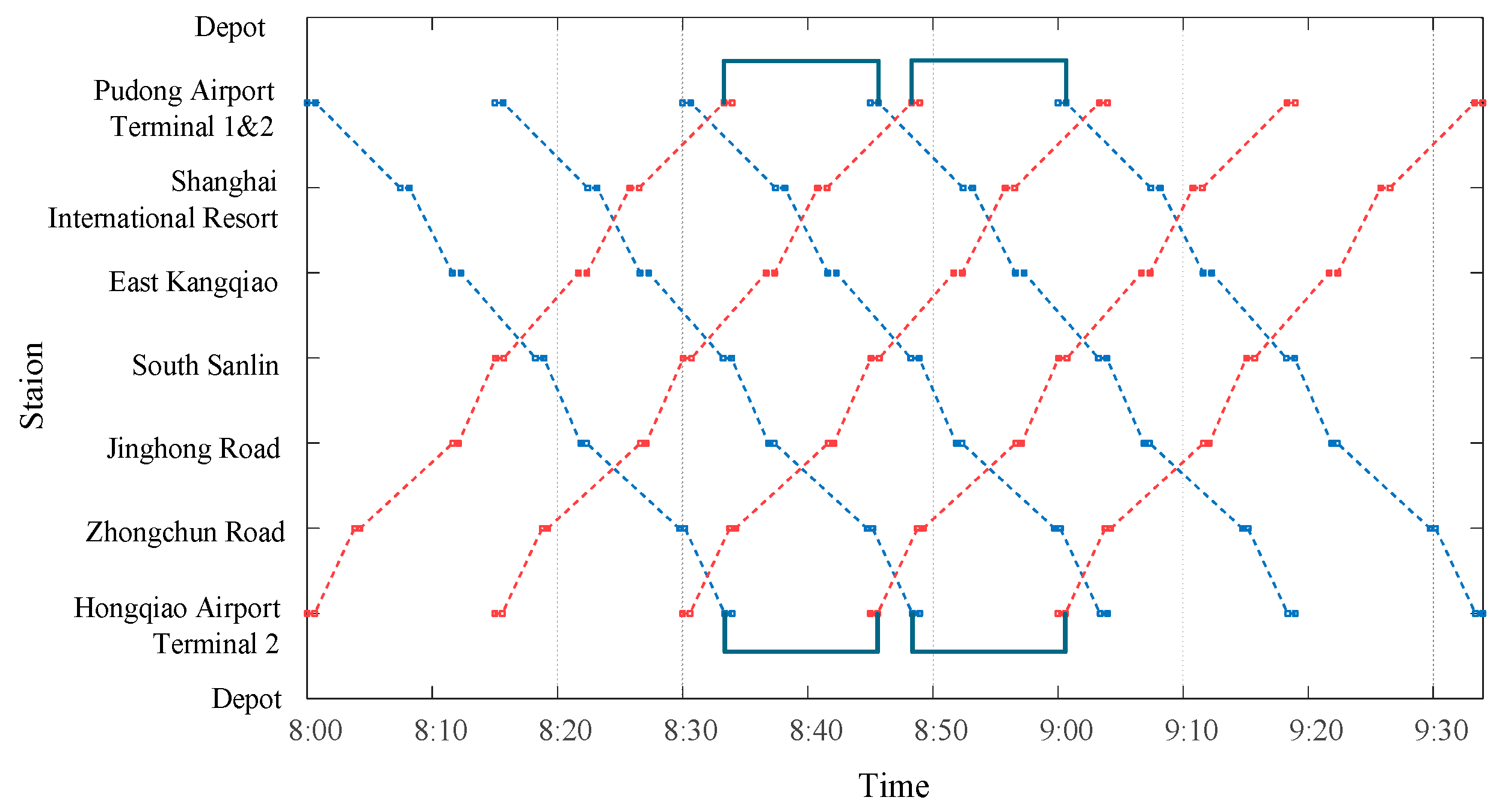

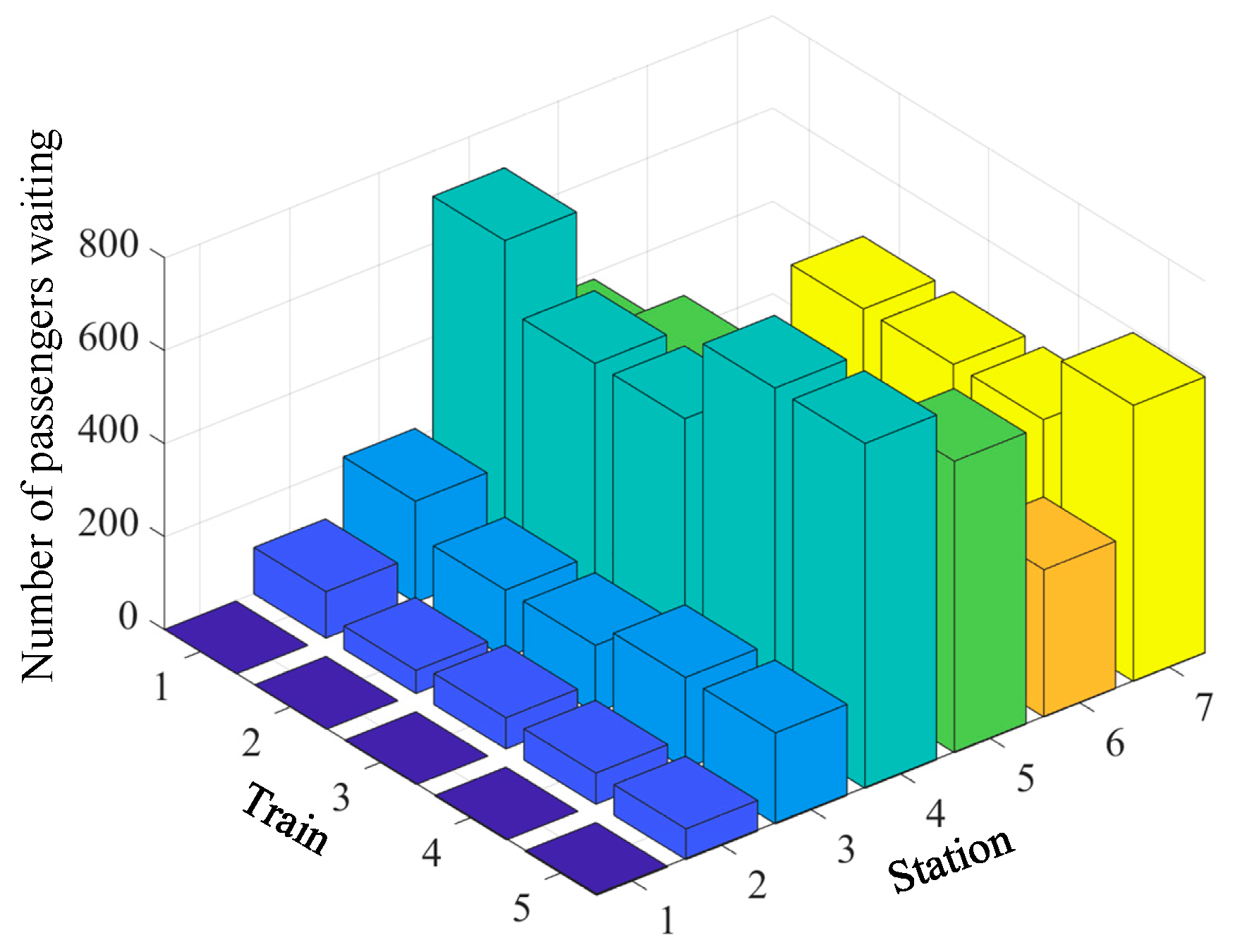

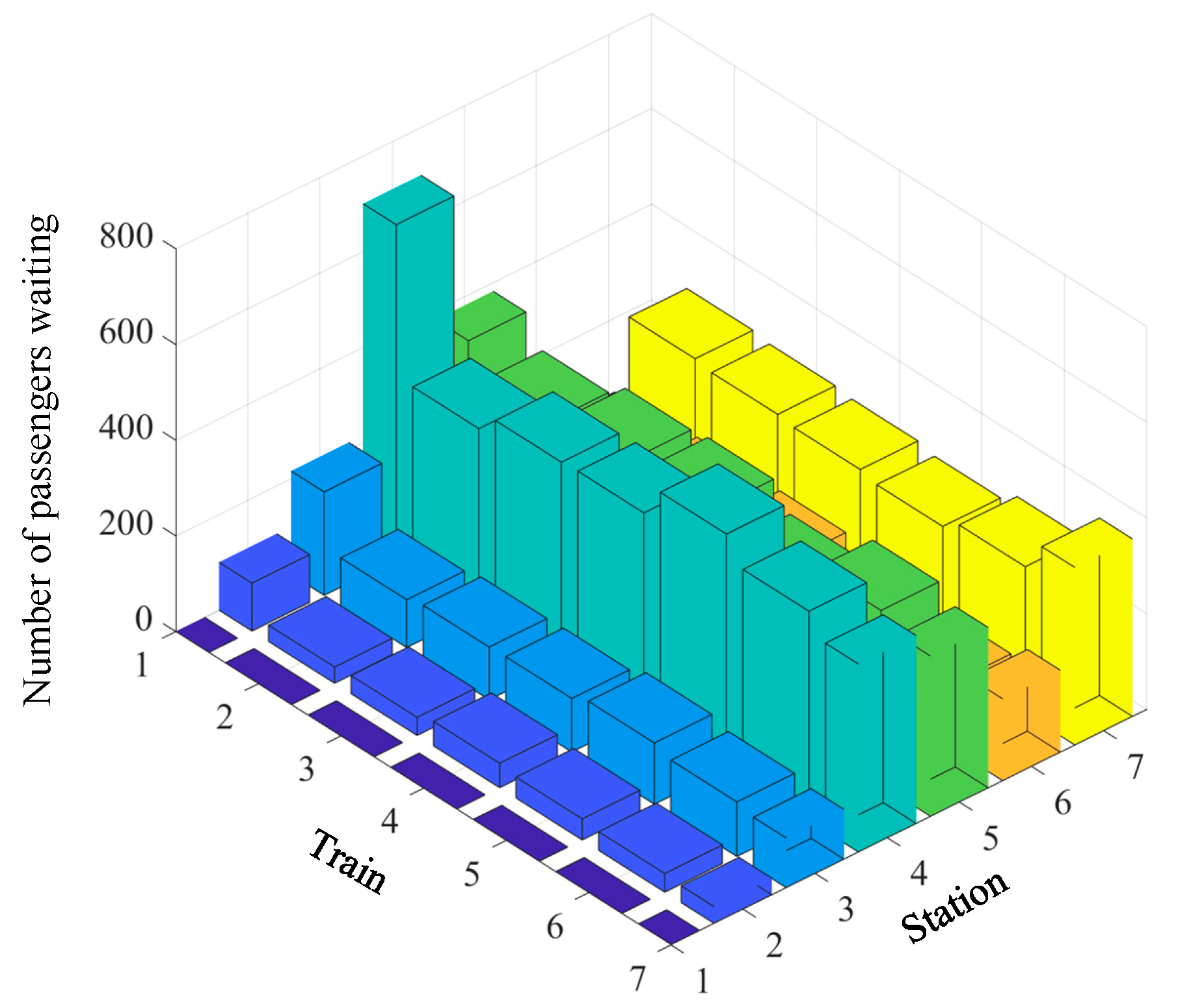

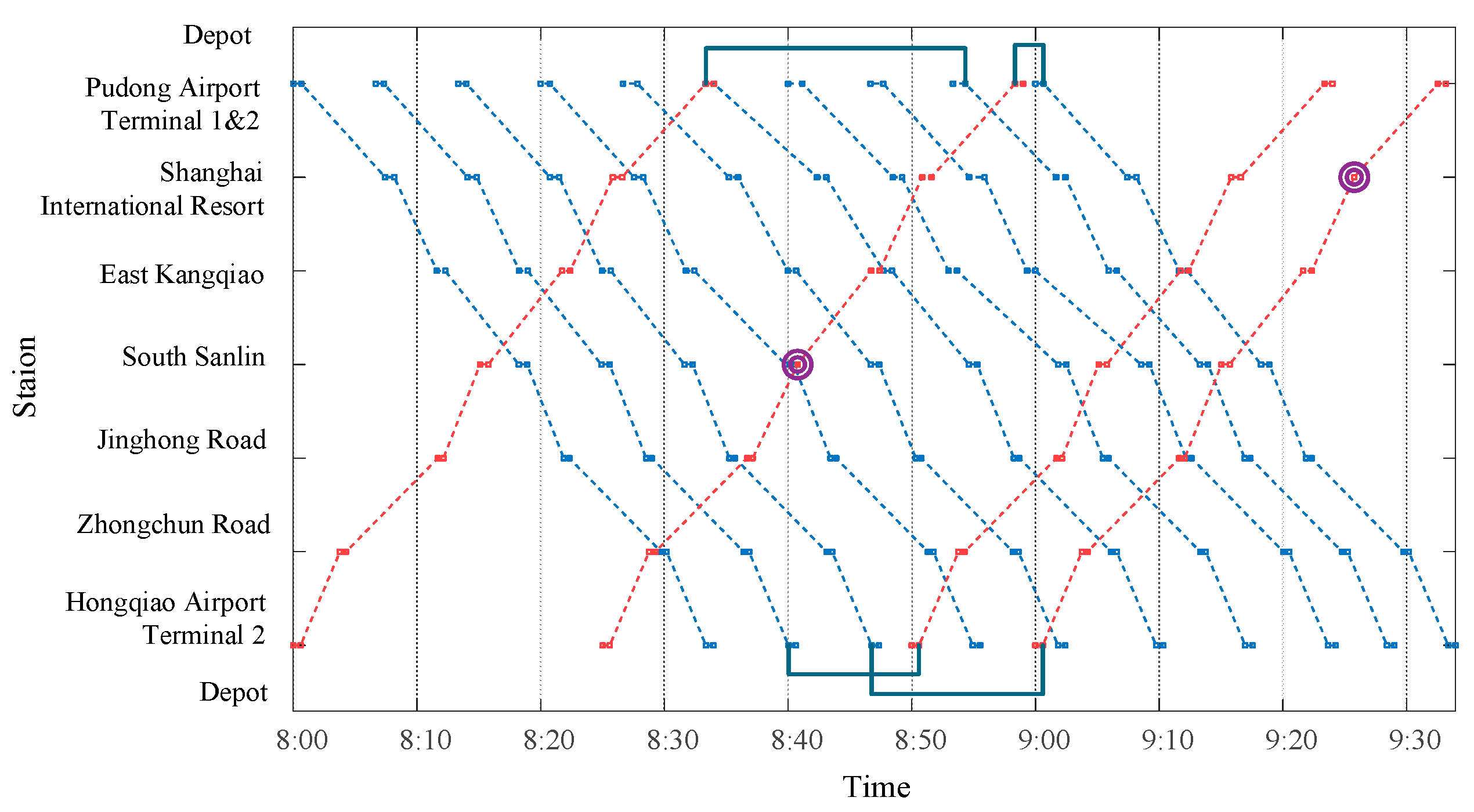

Based on the trial operation timetable of the shanghai suburban railway airport link line, it is evident that the headway between trains is 15 minutes, and an all-stop behavior is adopted. Consequently, five trains operate in both the upstream and downstream directions. The timetable obtained by T-TPOS is shown in

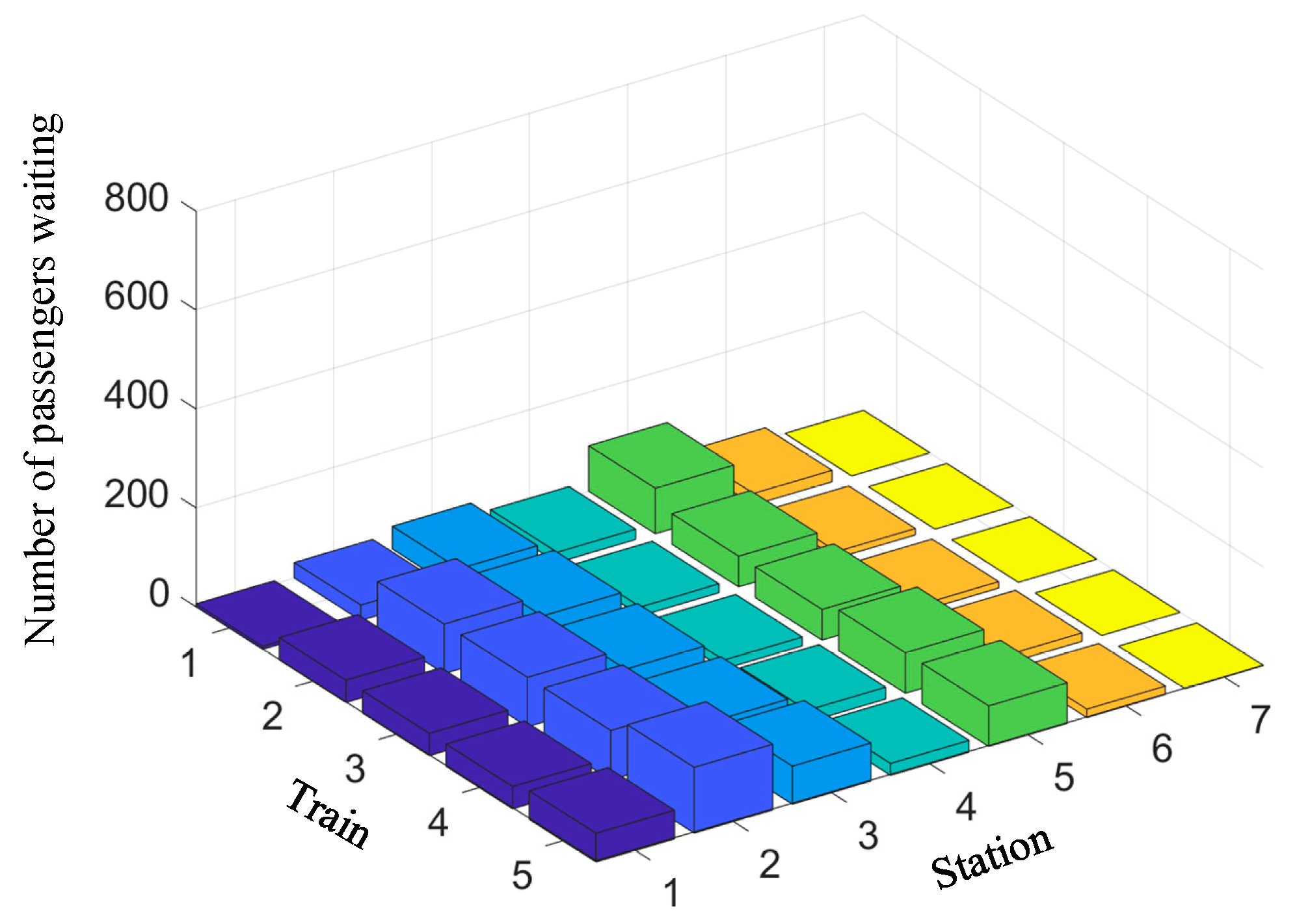

Figure 10. The number of passengers waiting on the stations is shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

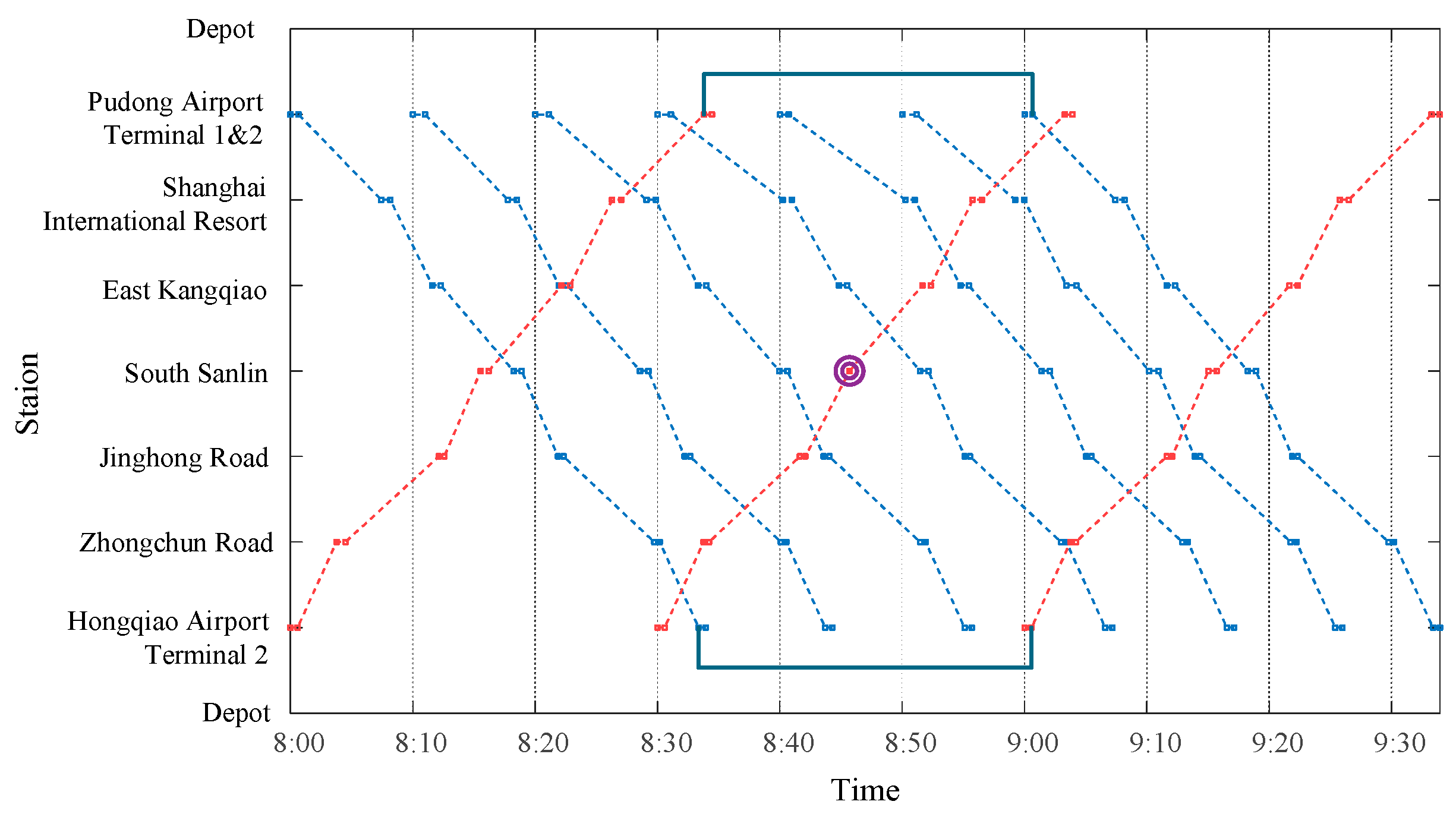

The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS obtained by the GUROBI solver is shown in

Figure 13. In the

Figure 13, the red dashed line and the blue dashed line indicate the time-station paths of trains in the downstream direction and the upstream direction, respectively. The double purple circles indicate the stations skipped by express trains in the downstream direction.

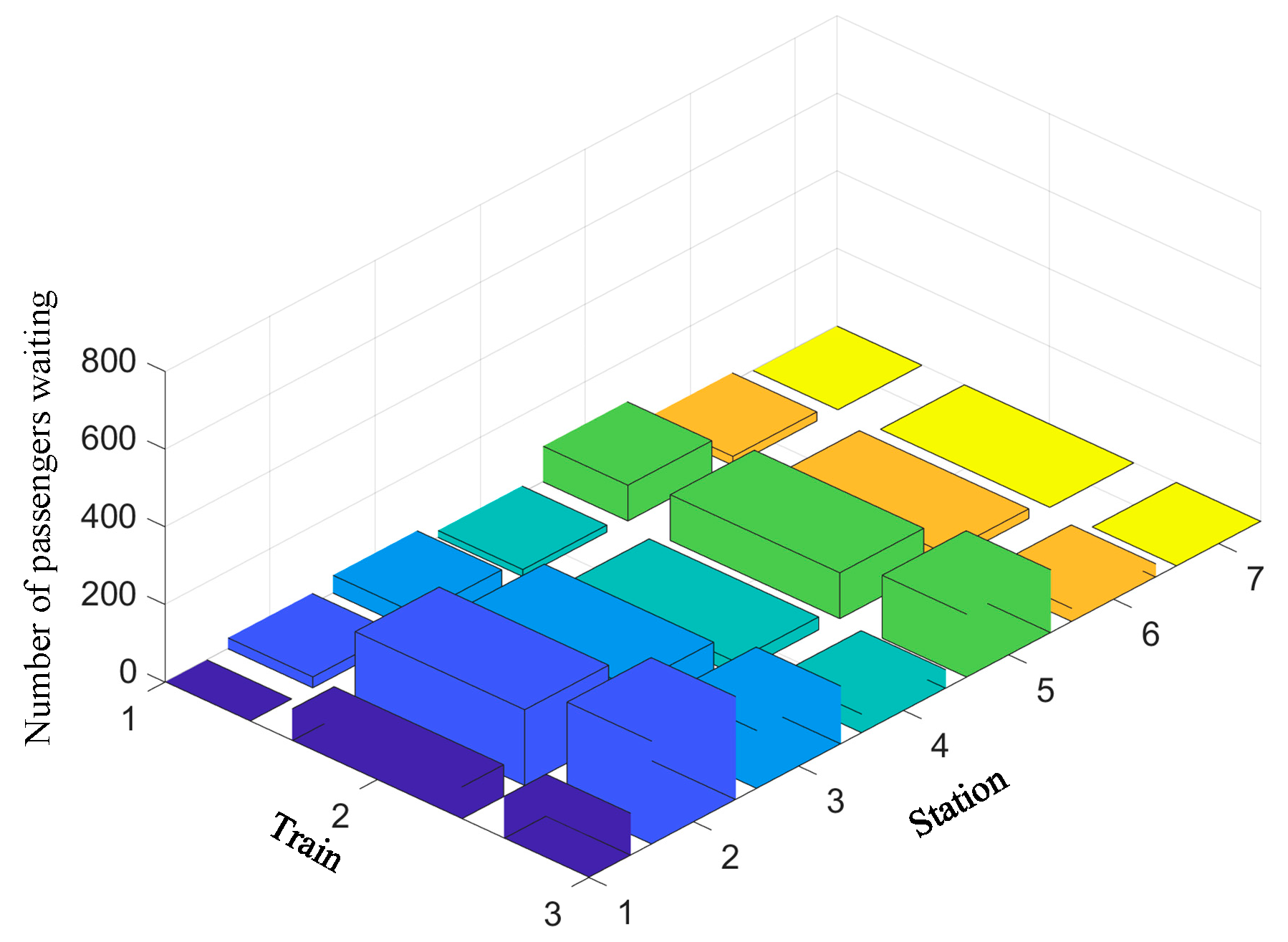

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the number of passengers waiting at each station in the upstream direction and downstream direction, respectively.

The number of stops, the number of stranded passengers and total travel time each train were counted for the two schemes, as shown in

Table 3. Passengers' total waiting time and on-board time are counted in

Table 4. The value of objective function represents the total cost of the operator and the passenger in RMB, which is determined by setting the values of

, i.e.,

. Moreover, the values marked with * are used in the calculation of the objective function.

In

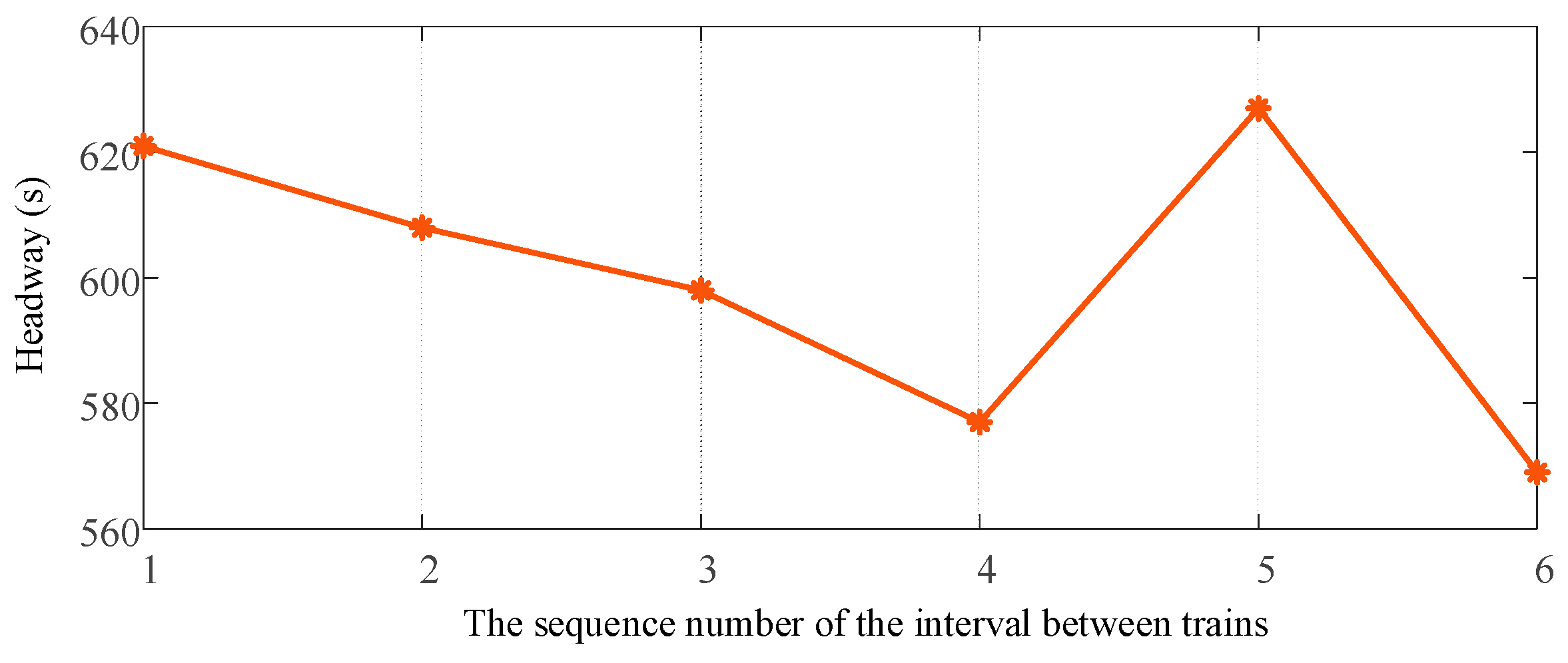

Table 3, TUOS-ELS saves 38.59% in the total cost of the operator and the passenger compared to T-TPOS. The number of trains in the upstream direction was increased from 5 to 7, creating a shortened headway. The obtained headways for each train in the upstream direction are shown in

Figure 16. All headways in the downstream direction are 1800 seconds. As a result, the number of stranded passengers decreased from 2489 to 196, and the total waiting time of passengers was greatly shortened from 2581.1 hours to 1841.1 hours in the upstream direction in

Table 4. However, in the downstream, at the expense of a small number of stranded passengers, the reduction in the number of trains and the use of express train (train 2) have significantly decreased the total travel time of trains from 10185 seconds to 6139 seconds. Moreover, passengers' on-board time were reduced by 8 hours as compared with T-TPOS in the downstream direction.

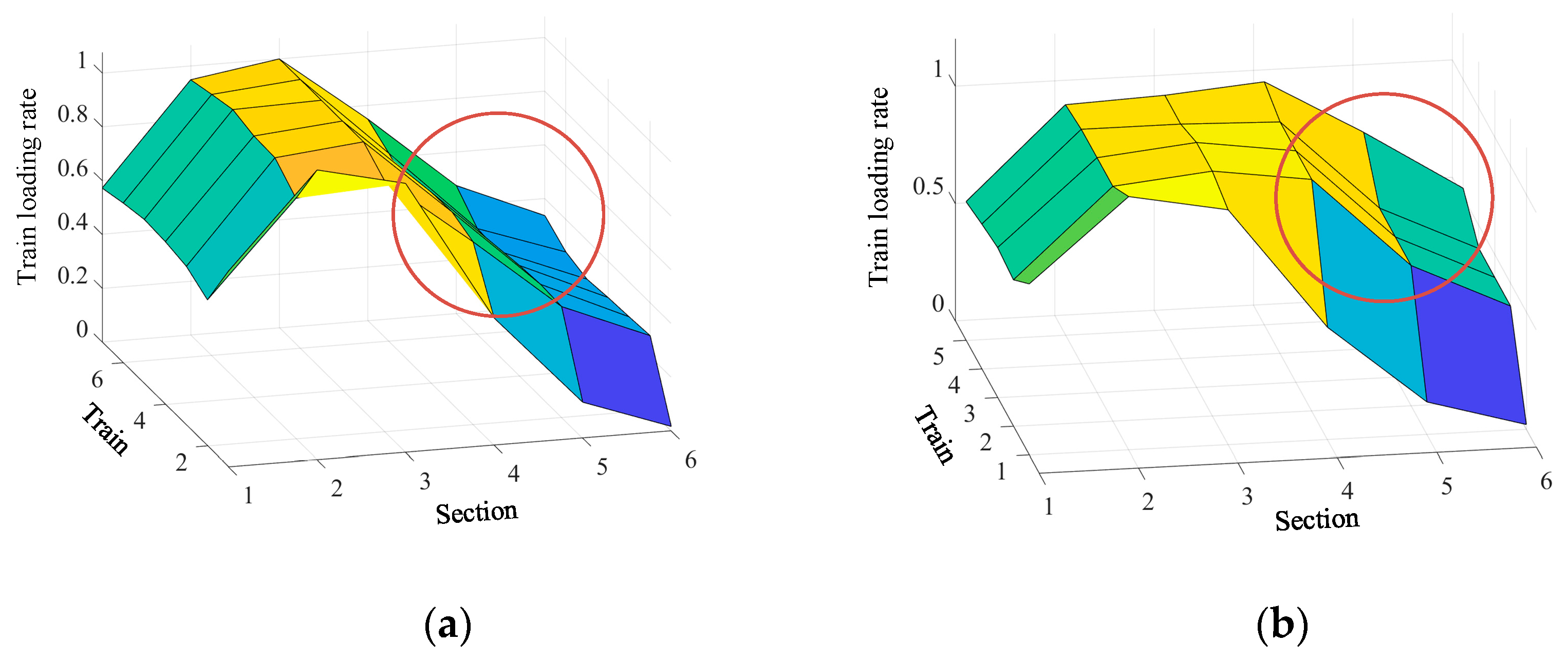

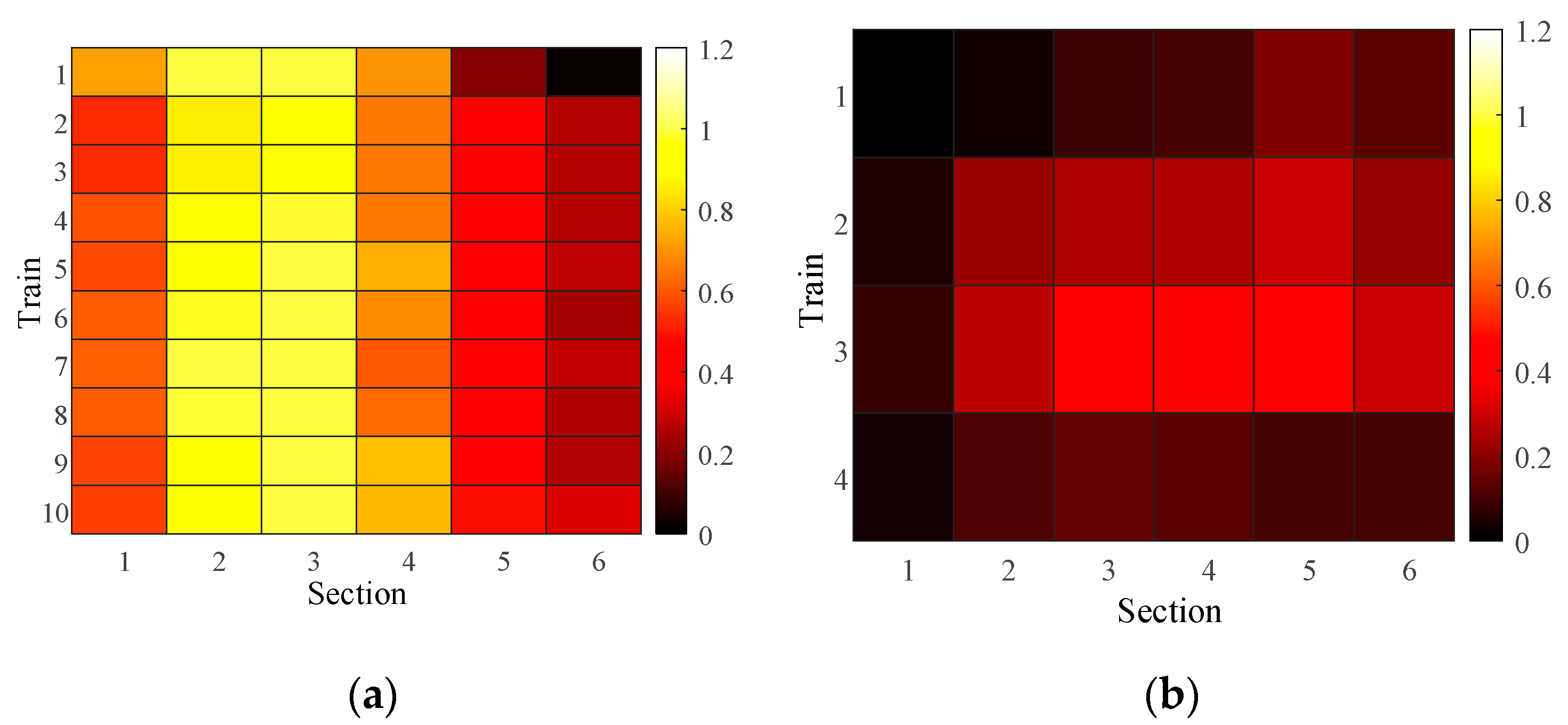

It is worth noting that TUOS-ELS can improve the trains loading rate in both directions. In

Figure 17(a) and

Figure 17(b), The maximum loading rates of TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS in the upstream direction are 107.64% and 107.82% respectively. Notably, the difference of maximum loading rates between the two schemes is not significant. But,

Figure 17(a) and (b) illustrate that the trains loading rate under the TUOS-ELS rapidly decreases during the section from 3 to 6, whereas the trains loading rate under the T-TPOS remains consistently high. Meanwhile, in the downstream direction, the maximum loading rate under TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS are 39.27% and 20%.

Figure 18(a) and (b) clearly demonstrate that the TUOS-ELS effectively enhances the trains loading rate and minimizes capacity waste.

5.3. Optimization of Timetable to Address Varying Passenger Demands

After the official operation of the shanghai suburban railway airport link line, there is typically an increase in passenger demand. To further illustrate the generality of the proposed solution and model, this section examines the timetable optimization to address varying passenger demand. Based on the OD passenger arrival rate

shown in

Figure 9, when

is doubled, such as

and

, it is possible to study the timetable of TUOS-ELS during the official operation period.

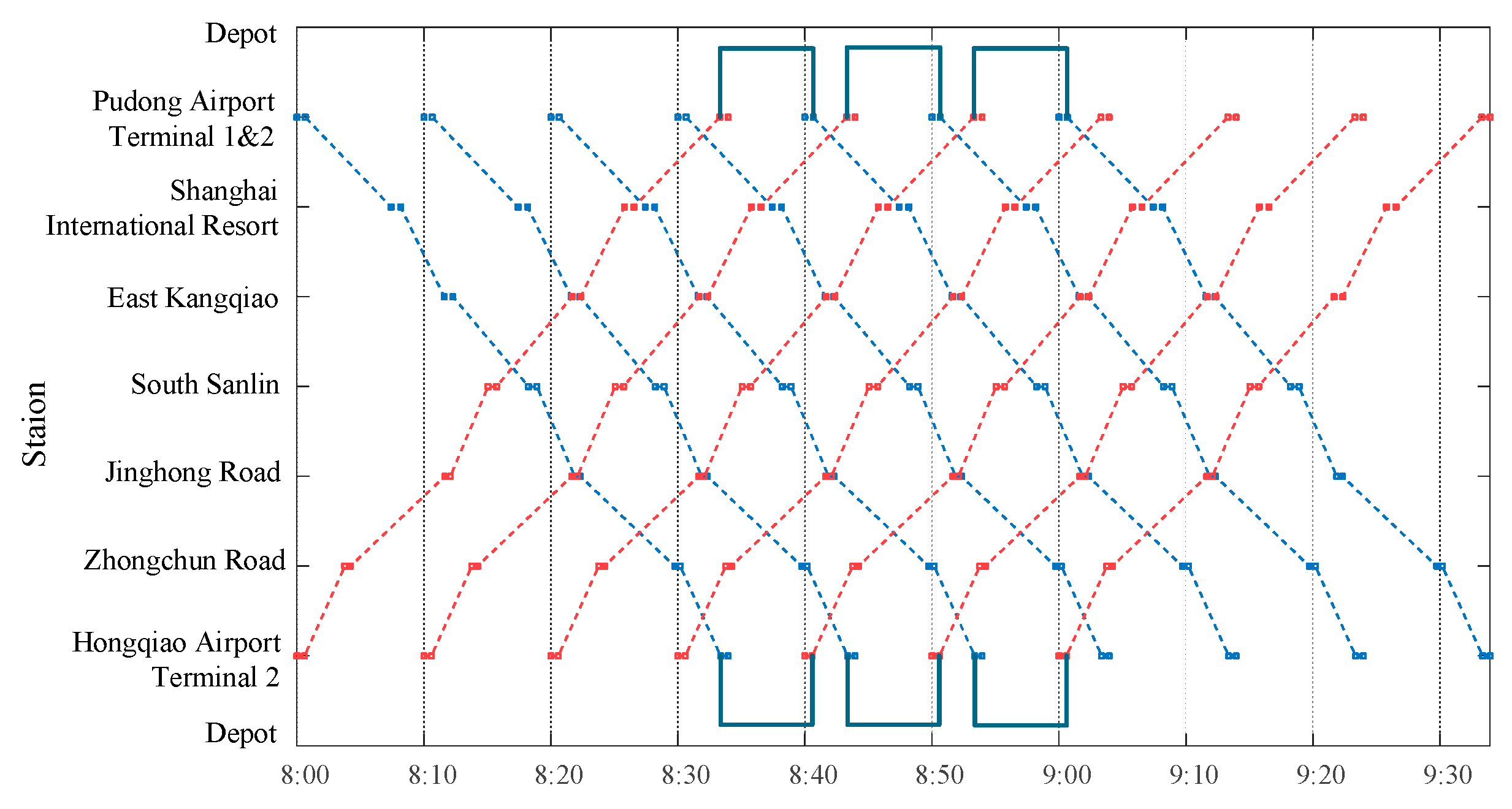

When the OD passenger arrival rate is

in official operation period, the optimization result indicates that 10 trains should operate in the upstream direction, while 4 trains should run in the downstream direction. The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS is shown in

Figure 19. The optimized results using the TUOS-ELS are compared with those obtained from the T-TPOS (

Figure 20), as shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6. The operator's and passenger's travel costs are saved by 35.28% after optimization, and can show the multi-strategies combination method still maintains a stable optimization effect under the scenario of increasing the number of travelling passengers.

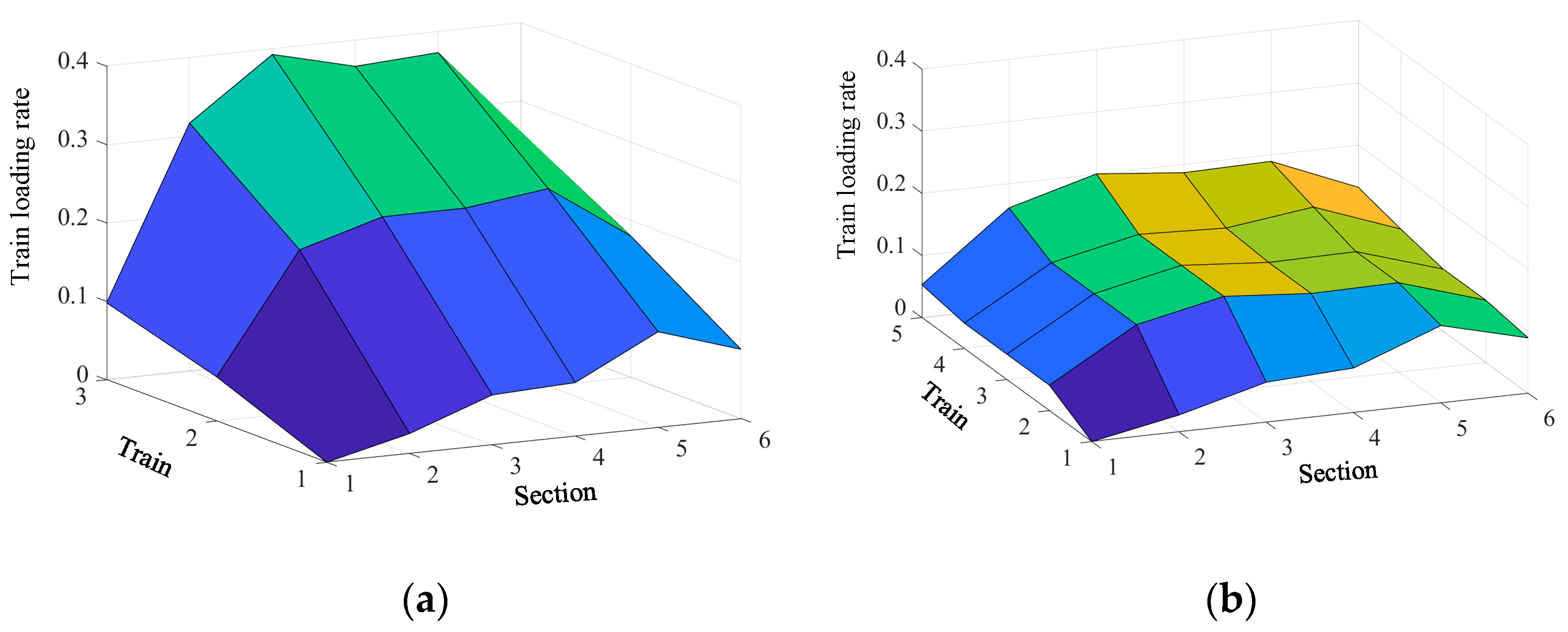

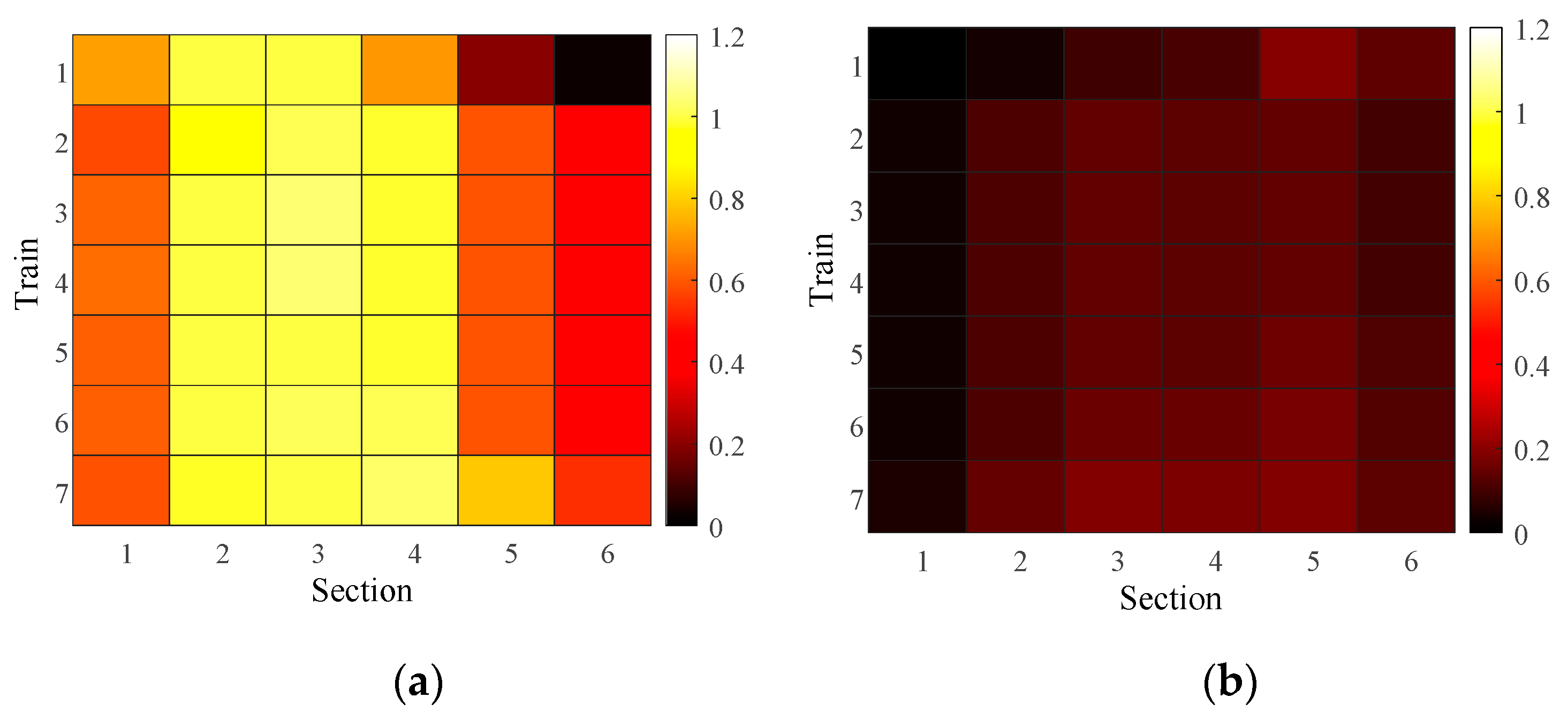

To illustrate trains loading rate in more detail, per-train loading rate heat maps are presented in

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

Figure 21(a) and

Figure 22(a) show the number of passengers loaded on the trains in the upstream direction for both TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS. However, in sections 2 to 4, the trains under the T-TPOS are congested, and the congestion level under the TUOS-ELS is well relieved.

Figure 21(b) and

Figure 22(b) indicate that trains operating in the downstream direction suffer from the problem of loading a smaller number of passengers. But, in the TUOS-ELS, loading rates of between 40 and 60 per cent are achieved in some sections, significantly increasing the use of train resources.

In summary, the optimization model and the multi-strategies method demonstrate versatility, effectively addressing lower passenger demand (with larger headways) and higher passenger demand (with smaller headways), and they can also be applied to metro lines. In particular, the use of unpaired operation strategy can flexibly improve the allocation of train capacity. While the implementation of express/local trains can shorten travel time, it also facilitates the allocation of capacity to required stations through skip-stopping behavior.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a multi-strategy optimization method of timetable in tidal passenger flow phenomenon. Specifically, the TUOS-ELS including the unpaired operation strategy and the express/local train operation strategy is proposed. TUOS-ELS has the flexibility to solve the problem of uneven distribution of passenger flow in both directions compared to the traditional train paired operation strategy (T-TPOS). Timetables are optimized during the morning rush hour for the trial and official operation period (i.e., increased passenger flow) of the shanghai suburban railway airport link line. With the objective of reducing the number of stranded passengers, the number of stops, and the total trains’ travel time, the objective values of 38.59% and 35.28% can be reduced during the trial and official operation period, respectively. From the perspective of trains loading rate, adopting the TUOS-ELS can improve the crowding of the carriages in the direction of heavy passenger flow and can increase the resource utilization in the other direction. Overall, the multi-strategies optimization method proposed in this paper effectively reduces operator costs, improves passenger service quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y. and P.S.; methodology, B.Y.; software, W.J.; validation, W.J., B.Y. and P.S.; formal analysis, R.D.; investigation, W.J.; resources, B.Y.; data curation, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.J.; writing—review and editing, P.S.; visualization, R.D.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, B.Y.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project of CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles Co., Ltd, project number 2023CCB171.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to all of the editors and reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tang, L; Zhao, Y; Cabrera, J; Ma, J; Tsui, L. Forecasting Short-Term Passenger Flow: An Empirical Study on Shenzhen Metro. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 3613-3622.

- Yin, J.; Yang, L.; Tang, T; Gao, Z.; Ran, B. Dynamic passenger demand oriented metro train scheduling with energy-efficiency and waiting time minimization: Mixed-integer linear programming approaches. Transp. Res. B-Meth. 2017, 97, 182-213.

- Zhuo, S.; Miao, J.; Meng, L.; Yang, L.; Shang, P. Demand-driven integrated train timetabling and rolling stock scheduling on urban rail transit line. Transportmetrica A. 2024, 20, 2181024.

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, X. Operational design for shuttle systems with modular vehicles under oversaturated traffic: continuous modeling method. Transp. Res. B-Meth. 2020, 132, 76–100.

- Yang, L.; Qi, J.; Li, S.; Gao Y. Collaborative optimization for train scheduling and train stop planning on high-speed railways. Omega. 2016, 64, 57-76.

- Xu, X; Li, C.L; Xu, Z. Train timetabling with stop-skipping, passenger flow, and platform choice considerations. Transp. Res. B-Meth. 2021, 150, 52-74.

- Sun, L.; Jin, J.; Lee, D.; Axhausen, K.; Erath A. Demand-driven timetable design for metro services. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 46, 284–299.

- Li, S.; Xu, R; Han, K. Demand-oriented train services optimization for a congested urban rail line: integrating short turning and heterogeneous headways. Transportmetrica A. 2019, 15(2), 1459-1486.

- Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Yuan, Y; Zhang, J.; Yang, L. Approximate dynamic programming approach to efficient metro train timetabling and passenger flow control strategy with stop-skipping. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107393.

- Jin, B; Guo, Y.; Wang, Q. Integrated scheduling method of timetable and rolling stock assignment scheme considering long and short routing. China Railway Science. 2022, 43(3), 173-181.

- Sun, P.; Yao, B.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Huang, Z. Optimization of unpaired timetable with express/local mode for the phenomenon of tidal passenger flow. IEEE 10th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Chengdu, China, 2024.

- Yuan, Y; Li, S; Liu, R. Decomposition and approximate dynamic programming approach to optimization of train timetable and skip-stop plan for metro networks. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 157, 104393.

- Liu, Z.; Pan, J.; Yang, Y.; Chi X. An energy-efficient timetable optimization method for express/local train with on-board passenger number considered. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 2068-1088.

- Zhang, R.; Yin, S.; Ye, M.; Yang, Z.; He, S. A Timetable Optimization Model for Urban Rail Transit with Express/Local Mode. J. Adv. Transport. 2021, 1–15.

- Shi, J.; Yang, J; Yang, L.; Tao, L. Safety-oriented train timetabling and stop planning with time-varying and elastic demand on overcrowded commuter metro lines. Transp. Res. E-Log. 2023, 175, 103136.

- Zhou, H.; Qi, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, J.; Pan, H.; Gao, Y. Joint optimization of train timetabling and rolling stock circulation planning: A novel flexible train composition mode. Transp. Res. B-Meth. 2022, 162, 352-385.

- Zhao, S; Yang, H; Wu, Y. An integrated approach of train scheduling and rolling stock circulation with skip-stopping pattern for urban rail transit lines. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103170.

- Mo, P; Yang, L.; D'Ariano, A; Energy-Efficient Train Scheduling and Rolling Stock Circulation Planning in a Metro Line: A Linear Programming Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 21(9), 3621-3633.

- Tang, L; Xu, X. Optimization for operation scheme of express and local trains in suburban rail transit lines based on station classification and bi-level programming. J. Rail. Transport. Pla. 2022, 21, 100283.

- Cao, Z.; Ceder, A. (Avi); Li, D.; Zhang, S. Robust and optimized urban rail timetabling using a marshaling plan and skip-stop operation. Transportmetrica A. 2020, 16(3), 1217–1249.

- Qi, J.; Li, S.; Gao, Y; Yang, K; Liu, P. Joint optimization model for train scheduling and train stop planning with passengers distribution on railway corridors. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2018, 69(4), 556-570.

Figure 1.

The rail transport planning process.

Figure 1.

The rail transport planning process.

Figure 2.

Traditional train paired operation strategy (T-TPOS).

Figure 2.

Traditional train paired operation strategy (T-TPOS).

Figure 3.

Train unpaired operation strategy (TUOS-ELS).

Figure 3.

Train unpaired operation strategy (TUOS-ELS).

Figure 4.

Description of train running status.

Figure 4.

Description of train running status.

Figure 5.

Diagram of dynamically varying passenger flows.

Figure 5.

Diagram of dynamically varying passenger flows.

Figure 6.

The optimization algorithm flowchart.

Figure 6.

The optimization algorithm flowchart.

Figure 7.

The shanghai suburban railway airport link line.

Figure 7.

The shanghai suburban railway airport link line.

Figure 8.

Time-varying station passenger arrival rate.

Figure 8.

Time-varying station passenger arrival rate.

Figure 9.

OD passenger flow arrival rate.

Figure 9.

OD passenger flow arrival rate.

Figure 10.

The timetable of T-TPOS.

Figure 10.

The timetable of T-TPOS.

Figure 11.

Figure 11. Number of passengers waiting of upstream

Figure 11.

Figure 11. Number of passengers waiting of upstream

Figure 12.

Number of passengers waiting of downstream.

Figure 12.

Number of passengers waiting of downstream.

Figure 13.

The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 13.

The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 14.

Figure 14. Number of passengers waiting in the upstream direction

Figure 14.

Figure 14. Number of passengers waiting in the upstream direction

Figure 15.

Number of passengers waiting in the downstream direction.

Figure 15.

Number of passengers waiting in the downstream direction.

Figure 16.

Headway between trains.

Figure 16.

Headway between trains.

Figure 17.

Train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS. (a) Train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Train loading rate in the upstream of T-TPOS.

Figure 17.

Train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS. (a) Train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Train loading rate in the upstream of T-TPOS.

Figure 18.

Train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS. (a) Train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Train loading rate in the downstream of T-TPOS.

Figure 18.

Train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS and T-TPOS. (a) Train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Train loading rate in the downstream of T-TPOS.

Figure 19.

The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 19.

The optimized timetable of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 20.

The optimized timetable of T-TPOS.

Figure 20.

The optimized timetable of T-TPOS.

Figure 21.

Heat maps of train loading rate under TUOS-ELS. (a) Heat maps of train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Heat maps of train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 21.

Heat maps of train loading rate under TUOS-ELS. (a) Heat maps of train loading rate in the upstream of TUOS-ELS; (b) Heat maps of train loading rate in the downstream of TUOS-ELS.

Figure 22.

Heat maps of train loading rate under T-TPOS. (a) Heat maps of train loading rate in the upstream of T-TPOS; (b) Heat maps of train loading rate in the downstream of T-TPOS.

Figure 22.

Heat maps of train loading rate under T-TPOS. (a) Heat maps of train loading rate in the upstream of T-TPOS; (b) Heat maps of train loading rate in the downstream of T-TPOS.

Table 1.

Operation data setting.

Table 1.

Operation data setting.

| Station |

Minimum

dwell time (s) |

Maximum

dwell time (s) |

Maximum

running time (s) |

minimum

running time (s) |

Hongqiao Airport

Terminal 2 |

35 |

65 |

- |

- |

| Zhongchun Road |

27 |

57 |

382 |

191 |

| Jinghong Road |

27 |

57 |

890 |

445 |

| South Sanlin |

40 |

70 |

356 |

178 |

| East Kangqiao |

41 |

71 |

714 |

357 |

| Shanghai International Resort |

45 |

75 |

412 |

206 |

Pudong Airport

Terminal 1&2 |

39 |

69 |

812 |

406 |

Table 2.

Time-related parameter settings.

Table 2.

Time-related parameter settings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1800 (s) |

400 (s) |

90 (s) |

90 (s) |

90 (s) |

90 (s) |

Table 3.

Comparison results including objective function values.

Table 3.

Comparison results including objective function values.

| |

Total travel time(s) |

Number of stops |

Stranded

passengers |

Objective value (Yuan) |

| Upstream* |

Downstream* |

Upstream*

|

Downstream*

|

Upstream*

|

Downstream*

|

| TUOS-ELS |

14886 |

6139 |

49 |

20 |

196 |

91 |

34245 |

| T-TPOS |

10185 |

10185 |

35 |

35 |

2489 |

0 |

55760 |

Table 4.

Comparison results including passengers' total travel time.

Table 4.

Comparison results including passengers' total travel time.

| |

Total waiting time(h) |

Total on-board time(h) |

Calculation time(s) |

Gap of GUROBI |

| Upstream |

Downstream |

Upstream |

Downstream |

| TUOS-ELS |

1841.1 |

723.6 |

2666.5 |

330.8 |

1000 |

0.45% |

| T-TPOS |

2581.1 |

388.7 |

2189.9 |

338.8 |

- |

- |

Table 5.

Comparison results including objective function values

Table 5.

Comparison results including objective function values

| |

Total travel time(s) |

Number of stops |

Stranded

passengers |

Objective value (Yuan) |

| Upstream* |

Downstream* |

Upstream*

|

Downstream*

|

Upstream*

|

Downstream*

|

| TUOS-ELS |

21293 |

8111 |

70 |

26 |

866 |

210 |

54564 |

| T-TPOS |

14259 |

14259 |

49 |

49 |

`4109 |

0 |

84380 |

Table 6.

Comparison results including passengers' total travel time.

Table 6.

Comparison results including passengers' total travel time.

| |

Total waiting time(h) |

Total on-board time(h) |

Calculation time(s) |

Gap of GUROBI |

| Upstream |

Downstream |

Upstream |

Downstream |

| TUOS-ELS |

2059.4 |

804.3 |

3876.2 |

437.8 |

1000 |

0.5% |

| T-TPOS |

2770.1 |

421.1 |

3121.4 |

496.2 |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).