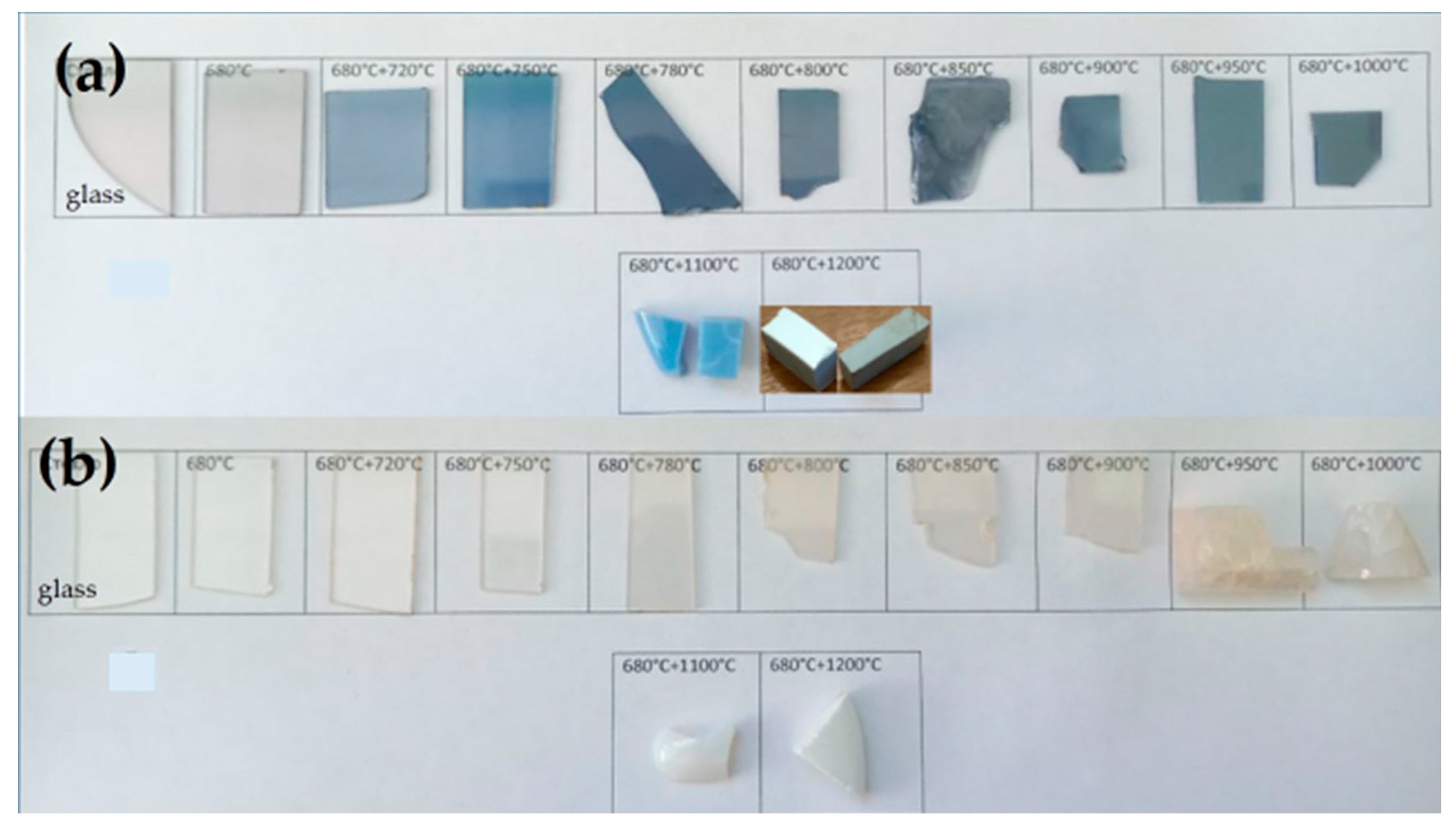

3.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Figure 3 shows the DSC curves of the quenched LAS and LAS

ox glasses, as well as these glasses heat-treated at 680 °C, 700 °C and 720 °C for 6 h. The shapes of the corresponding DCS curves of LAS and LAS

ox glasses are near similar being different in the values of characteristic crystallization temperatures, see

Figure 3 and

Table 1. The DSC curve of the quenched LAS

ox glass shows three peaks with markedly different intensities. The first one is a broad peak of a low intensity with T

max = 802 °C, the second one is a narrow and intense peak with crystallization onset temperature T

on = 851 °C, and crystallization maximum temperature T

max = 874 °C. The third one is a weak exothermic peak with T

max = 1186 °C. The first peak is usually assigned to nucleation of the main crystalline phase, the second one to crystallization of lithium aluminosilicate solid solution (ss) with β-quarts structure (β-quarts ss), and the third one to the transformation of β-quartz ss into β-spodumene ss [

50,

51]. The DSC curve of the LAS glass exhibits a plateau instead of the first peak, see

Figure 3 and

Table 1. All characteristic crystallization temperatures of the LAS glass are lower than those for the LAS

ox glass, while the glass transition temperatures of both glasses are similar, see

Table 3. Therefore, redox conditions of glass melting affect crystallization temperatures and do not affect glass transition temperature of glasses.

Table 1.

Characteristic temperatures of initial quenched and heat-treated glasses shown in DSC curves.

Table 1.

Characteristic temperatures of initial quenched and heat-treated glasses shown in DSC curves.

| Heat-treatment schedule |

Tg, °C |

Ton1, °C |

Tmax1, °C |

Ton2, °C |

Tmax2, °C |

Tmax3, °C |

| The LAS glass |

|---|

| quenched |

698 |

- |

- |

847 |

867 |

1175 |

| 680 °С, 6 h |

699 |

810 |

839 |

882 |

909 |

1142 |

| 700 °С, 6 h |

705 |

764 |

810 |

878 |

900 |

1135 |

| 720 °С, 6 h |

708 |

765 |

826 |

871 |

890 |

1140 |

| The LASox glass |

| quenched |

699 |

- |

802 |

851 |

874 |

1186 |

| 680 °С, 6 h |

695 |

799 |

831 |

876 |

901 |

1136 |

| 700 °С, 6 h |

704 |

779 |

809 |

879 |

899 |

1141 |

| 720 °С, 6 h |

708 |

755 |

828 |

876 |

900 |

1136 |

Preliminary heat-treatments lead to a drastic change in the appearance of DSC curves, see

Figure 3. The character of this change for LAS and LAS

ox samples is the same, differing in the temperatures of thermal effects. Instead of a narrow exothermic peak of high intensity, two broad peaks of lower intensities appear. The characteristic temperatures for both glasses heat-treated at the nucleation stage are presented in

Figure 3 and

Table 1. T

max of the second broad exothermic peak is 35-40 °C higher than this temperature for the initial quenched glass. With increasing the temperature of preliminary heat-treatment, there is a redistribution of intensities of these two peaks in favor of the second one, see

Figure 3. T

max of the second peak and T

g gradually increase, see

Table 1. We will explain the reason of this behavior below while discussing the phase composition of the samples. The characteristic T

g, T

on and T

max temperatures of glasses preliminary heat-treated at 680 °C are similar being somewhat higher for the LAS glass than for the corresponding LAS

ox samples.

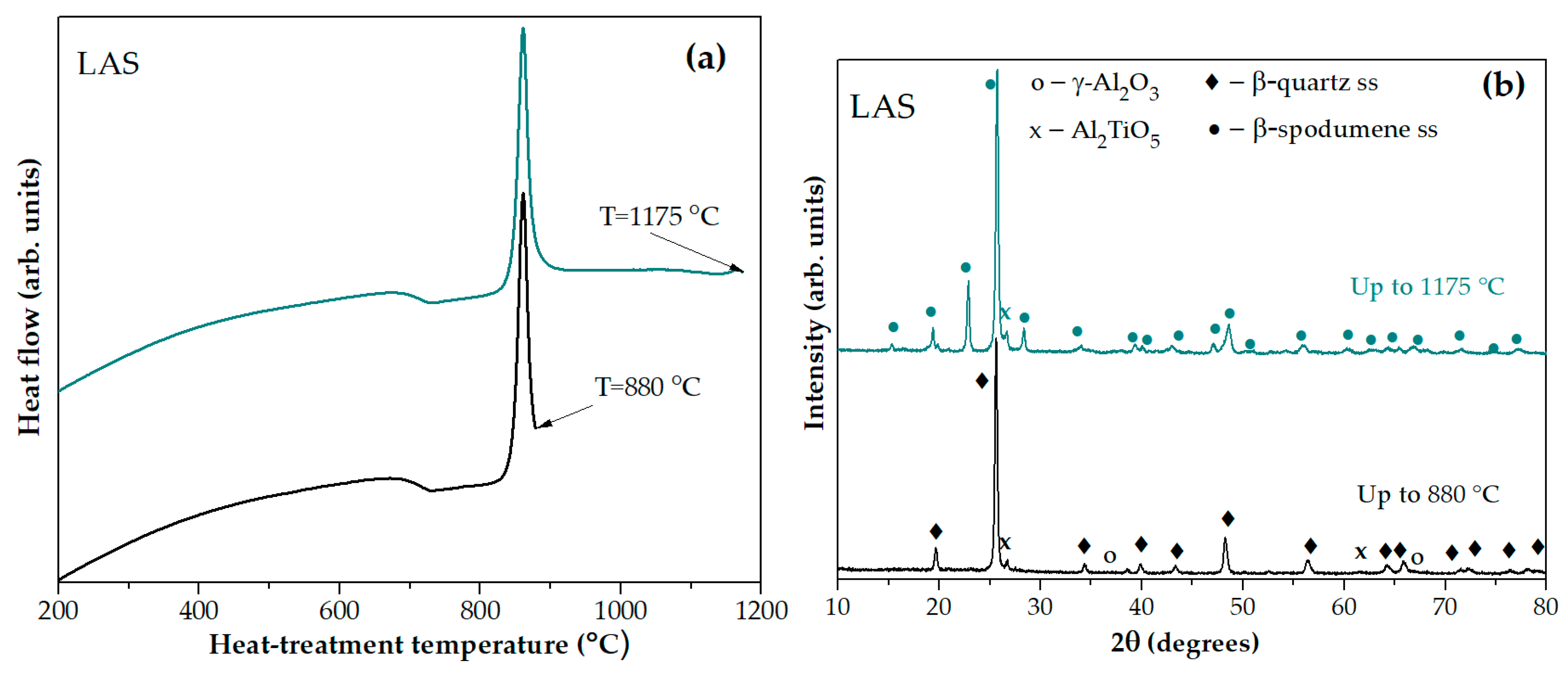

The XRD pattern of the glass-ceramic obtained by heating the quenched LAS glass in the furnace of the DSC instrument up to the temperature of the sharp exothermic peak at 880 °С, see

Figure 4(a), testifies crystallization of β-quarts ss, traces of tieilite, Al

2TiO

5, and spinel, see

Figure 4(b). On the XRD pattern of the sample heated up to temperature of the third exothermic effect at 1175 °С, additional diffraction peaks appear as compared with the pattern of the sample heated up to 880 °С manifesting transformation of the β-quarts ss into the β-spodumene ss while spinel traces disappeared. Thus, the small high-temperature peak evolving at ~1175 °С is due to crystallization of β-spodumene ss, see

Figure 4(b).

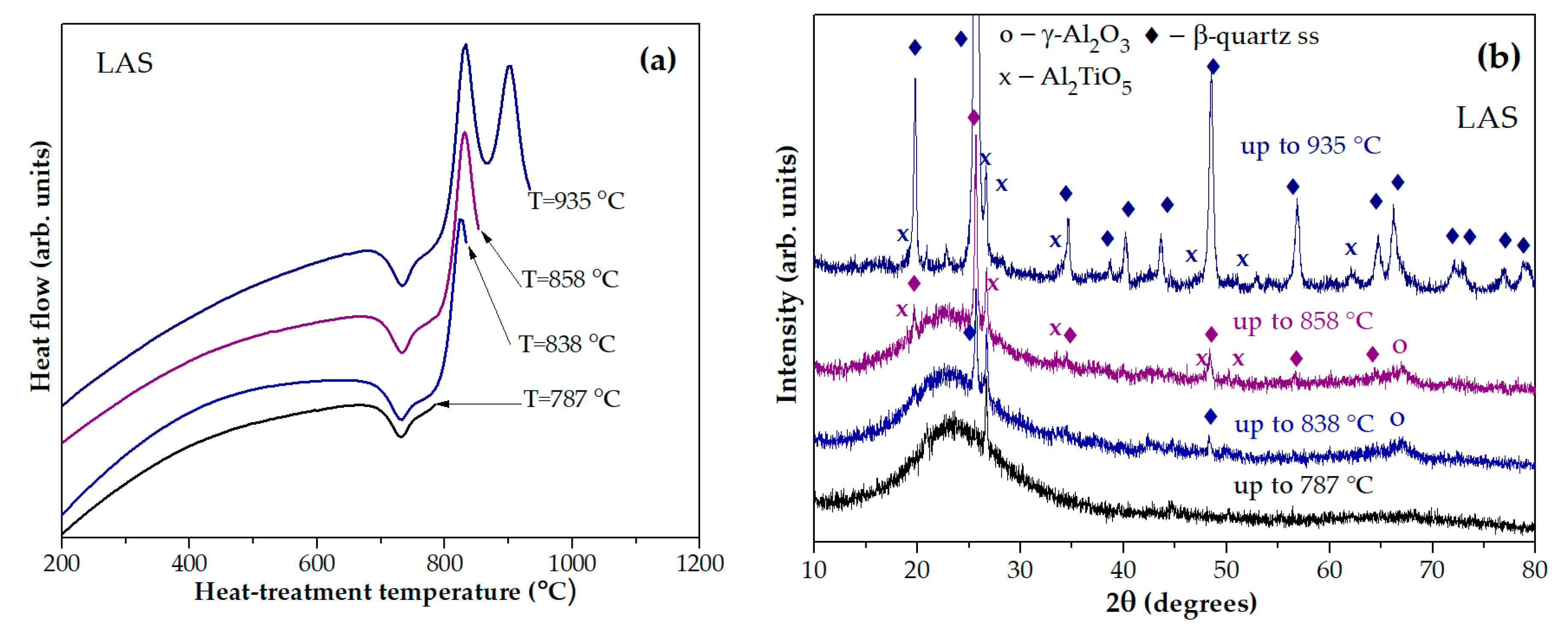

Figure 5(a) shows DSC curves of the LAS glass preliminary heat-treated at 680 °C for 6 h with stops at temperatures of 787 °С, 838 °С, 858 °С, and 935 °С. The corresponding XRD patterns are presented in

Figure 5(b). The material obtained by the heat-treatment at 680 °С, 6 h + 787 °С, 0 h is X-ray amorphous. The sample obtained by the heat-treatment at 680 °С, 6 h + 838 °С, 0 h contains nanocrystals of γ-Al

2O

3 with spinel structure and traces of β-quarts ss. We speculate that this exothermic peak is caused by crystallization of spinel, while traces of β-quarts ss appear during cooling the sample with the furnace because the samples heated to the specified temperature could not be immediately removed from the hot furnace of the DSC instrument. The XRD pattern of the sample obtained by the heat-treatment 680 °С, 6 h + 858 °С, 0 h, corresponding to the end of the first exothermic peak and the beginnning of the second one contains peaks of nanocrystals of γ-Al

2O

3, Al

2TiO

5 and β-quarts ss. The XRD pattern of glass-ceramic obtained by the heat-treatment at 680 °С, 6 h + 935 °С, 0 h proves crystallization of β-quarts ss and Al

2TiO

5. We cannot rule out the presence of γ-Al

2O

3 on this XRD pattern because the most intense peak of γ-Al

2O

3 overlaps the peaks of β-quarts ss and is therefore difficult to detect.

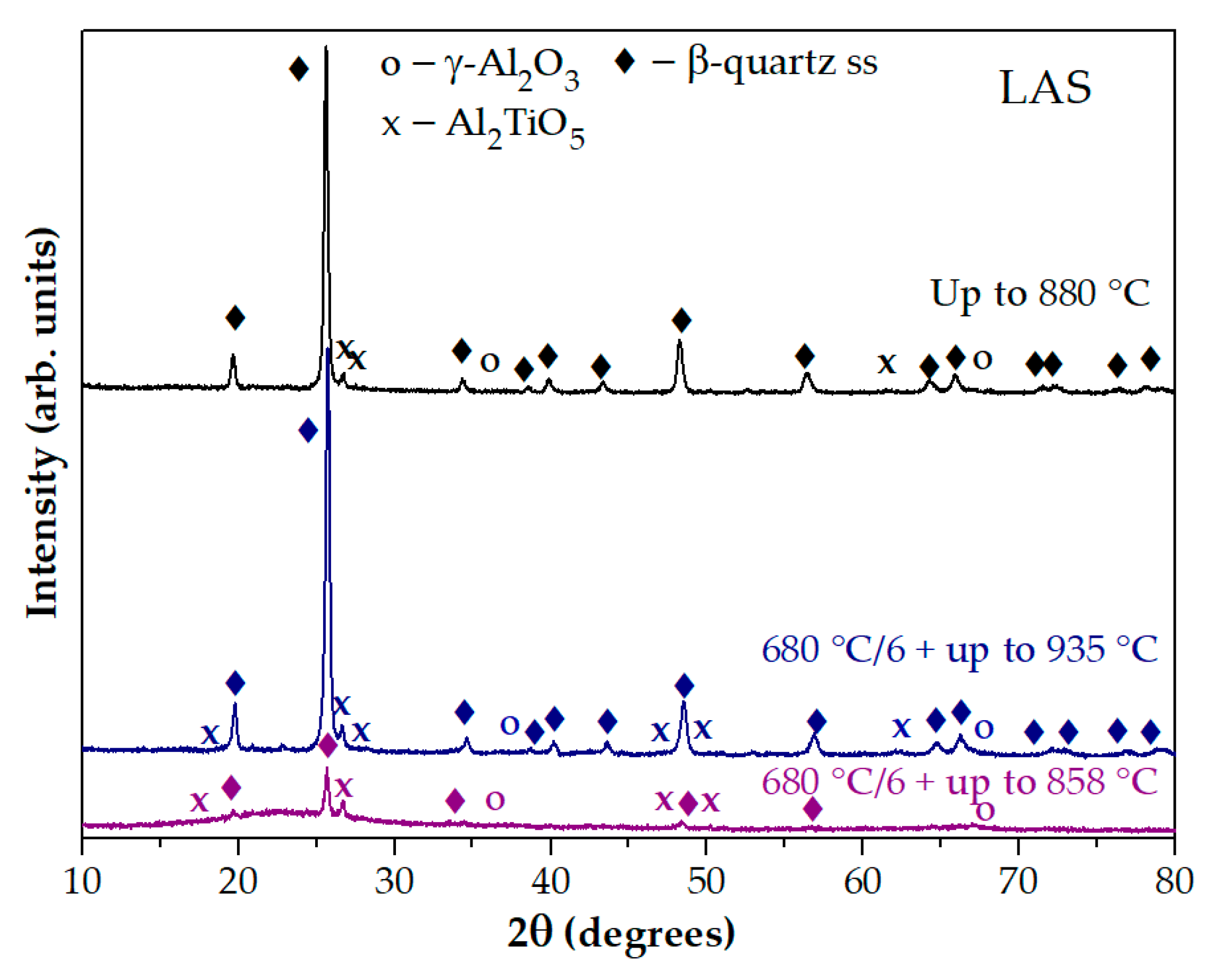

The XRD pattern of the glass preliminary heat-treated at 680 °C for 6 h and heated in the DSC furnace up to 858 °C is significantly different from the XRD pattern of the quenched glass heated in the DSC furnace up to 880 °C. The XRD pattern of the glass preliminary heat-treated at 680 °C for 6 h and heated in the DSC furnace up to 935 °C is similar to XRD pattern of the quenched glass heated in the DSC furnace up to 880 °C, see

Figure 6. Thus, the first peak on the DSC curve of the preliminary heat-treated sample is associated with crystallization of the phase with the spinel structure, and the second peak is caused by crystallization of β-quartz ss and Al

2TiO

5. On the DSC curve of the quenched sample there is no exothermic peak associated with crystallization of the phase with spinel structure. Therefore, preliminary heat-treatments provoke spinel crystallization and increase crystallization temperature of β-quartz ss and Al

2TiO

5.

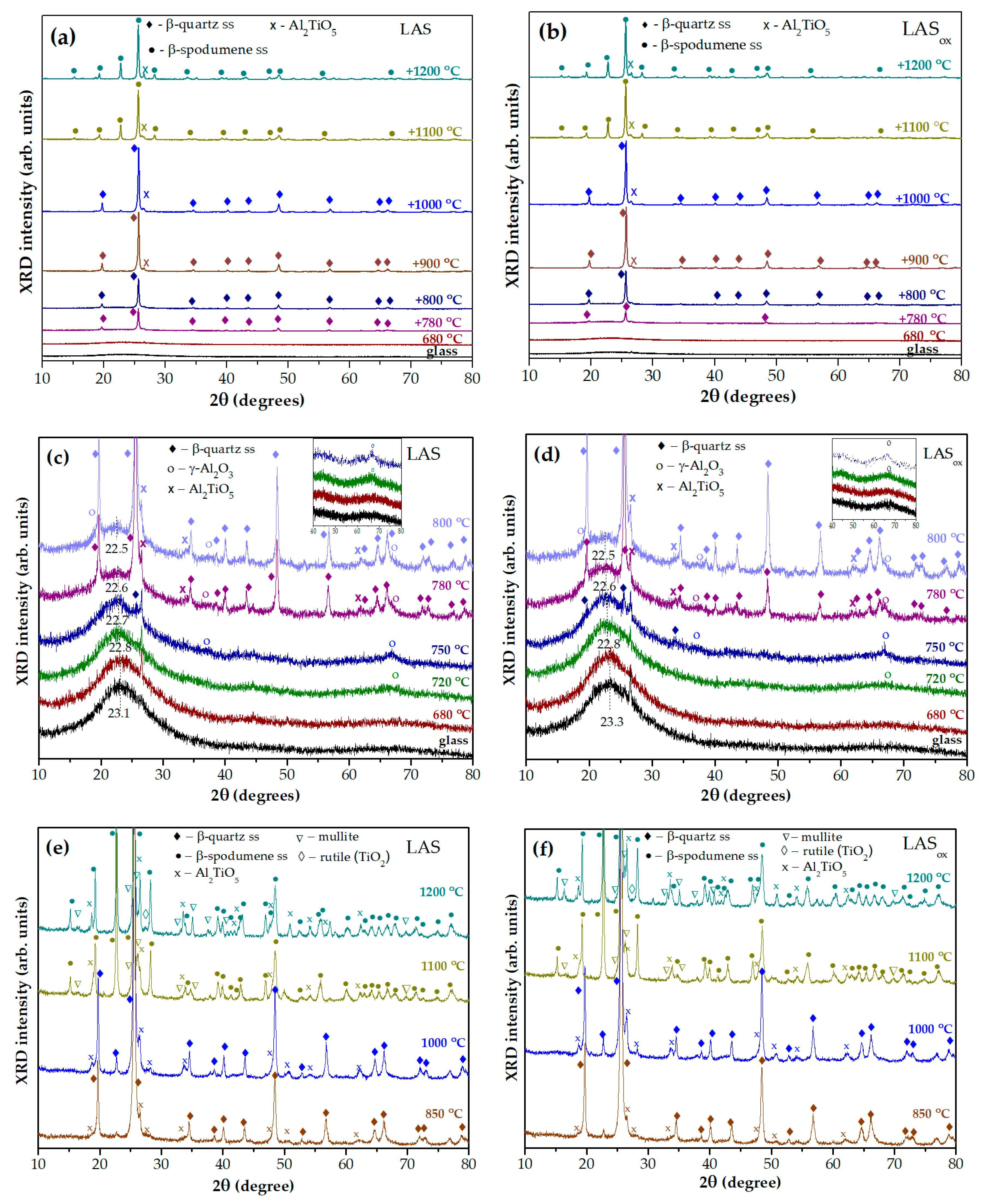

3.2. XRD Study

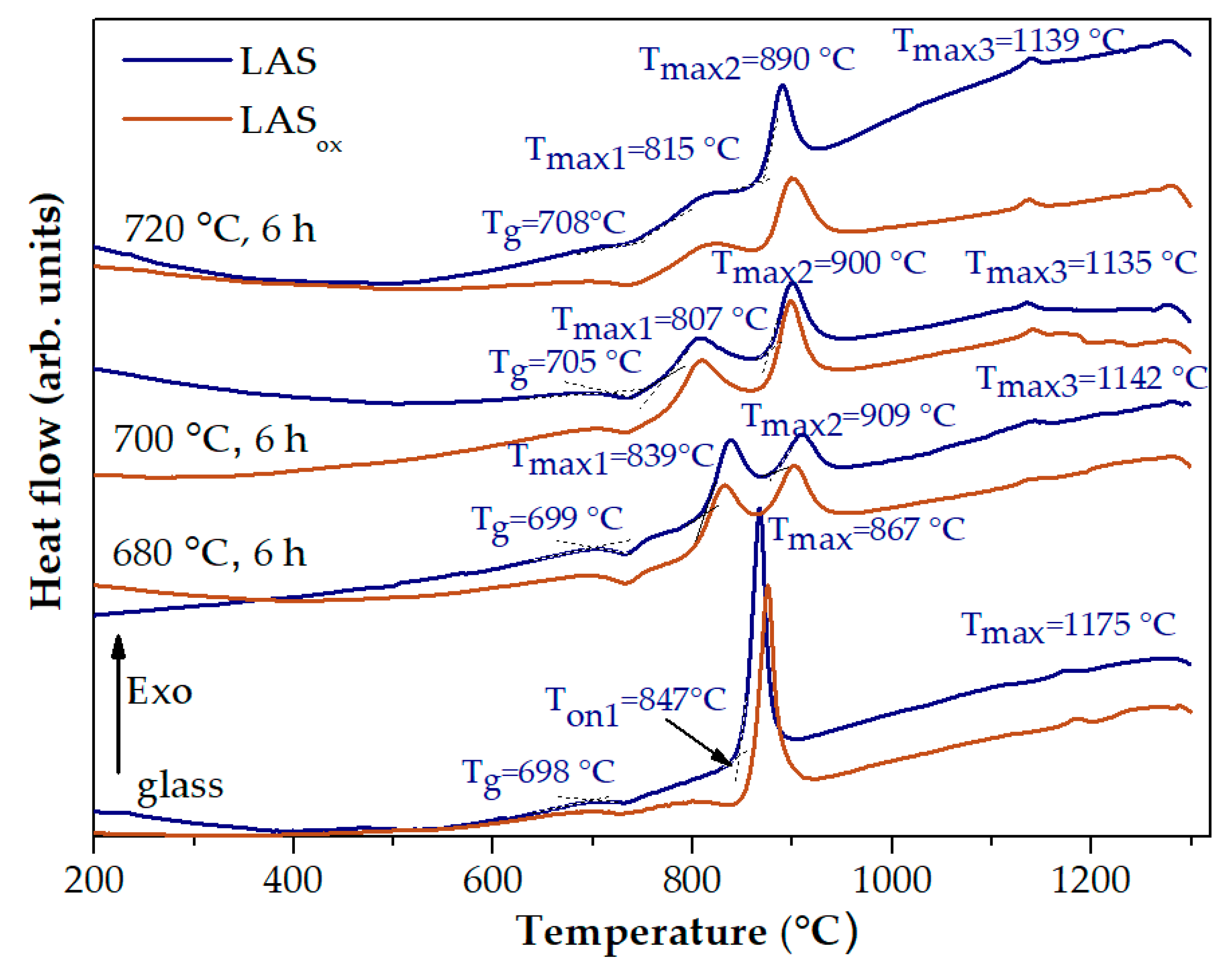

a,b show XRD patterns of initial glasses of the LAS and LASox compositions and glasses of the same compositions, which underwent heat-treatment at the nucleation stage of 680 °C and two stage heat-treatments with temperature at the second stage ranging from 720 °C to 1200 °C. The holding time at each stage was 6 h. The figures allow to follow the formation of the main crystalline phase, β-quartz ss, in the temperature range from 780 °C to 1000 °C and crystallization of β-spodumene ss in the temperature range from 1100 °C to 1200 °C. Figures 7(c,d) give a closer look on XRD patterns of glasses and glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at the second stage up to 800 °C. Initial LAS and LASox glasses are X-ray amorphous with a maximum of amorphous halo located at 2θ=23.1 ° and 23.3 °, respectively. Glasses heat-treated at the nuclation stage of 680 °C for 6 h remain X-ray amorphous, their XRD patterns are similar to those of initial glasses. The two stage heat-treatment with the second stage at 720 °C for 6 h leads to crystallization of a small fraction of crystals with spinel structure, manifested by an appearance of a broad peak with Miller indice hkl (440) at 2θ≅66.8 °.

Figure 7.

(a,b) XRD patterns of LAS and LASox glasses and glass-ceramics: (a) the LAS; (b) the LASox; (c,d) a closer look on XRD patterns of glasses and glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at the second stage up to 800 °C: (c) the LAS; (d) the LASox; (e,f) a closer look on XRD patterns of glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at the second stage from 850 °C to 1200 °C: (e) the LAS; (f) the LASox. The heat-treatment temperature at the first stage is 680 °C, duration of each stage is 6 h. The patterns are shifted for the convenience of observation.

Figure 7.

(a,b) XRD patterns of LAS and LASox glasses and glass-ceramics: (a) the LAS; (b) the LASox; (c,d) a closer look on XRD patterns of glasses and glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at the second stage up to 800 °C: (c) the LAS; (d) the LASox; (e,f) a closer look on XRD patterns of glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at the second stage from 850 °C to 1200 °C: (e) the LAS; (f) the LASox. The heat-treatment temperature at the first stage is 680 °C, duration of each stage is 6 h. The patterns are shifted for the convenience of observation.

Its low intensity prevents estimation of the lattice parameter a and size of spinel crystals. The position of the amorphous halo shifts to a smaller angle 2θ=22.8 ° for both samples. After the heat-treatment at the second stage at 750 °C for 6 h spinel peaks become more pronounced, which indicates an increase in the volume fraction of this phase. The lattice parameters of spinel crystals are anorm=7.918 Å and aox=7.916 Å, and sizes are Dnorm=4.5 nm and Dox=7.3 nm, respectively. The traces of β-quartz ss are also seen on the patterns. Appearance of spinel and traces of β-quartz ss cause a further change in the composition of the residual glass phase, which is manifested by a shift of the maximum of the amorphous halo to smaller angles, indicating that the residual glass becomes enriched in silica. After heat-treatments at the second stage at 780 °C and 800 °C, the β-quartz ss becomes the predominant crystalline phase, while spinel and tieilite, Al2TiO5, nanocrystals are also found in the XRD patterns. The position of the amorphous halo of a residual glass is shifted to 2θ=22.6 °and then to 2θ=22.5 ° with increasing the heat-treatment temperature, see Figures 7(c,d).

The lattice parameters and mean crystal sizes of spinel obtained at different heat-treatment temperatures are presented in

Table 2. We believe that spinel has the composition and structure of γ-Al

2O

3. The lattice parameter

a of the unit cell of the cubic modification of Al

2O

3 usually takes the value

a=7.900 - 7.908 Å [

52]. With a slight oxygen deficiency, the parameter

a of γ-Al

2O

3 becomes equal to 7.911 Å (ICDD PDF card #79-1558) and 7.914 Å (ICDD PDF card 79-1557) [

53]. The lattice parameter

a of γ-Al

2O

3 crystals in glass-ceramics changes from 7.915 Å to 7.925 Å and increases with increasing the heat-treatment temperature. The difference in the parameter

a of γ-Al

2O

3 nanocrystals in LAS and LAS

ox glass-ceramics is very small. Nevertheless, the lattice parameter

a of γ-Al

2O

3 in LAS glass-ceramics is slightly higher than in LAS

ox ones. The spinel crystal sizes increase with increasing the heat-treatment temperature ranging from 4.5 to 14.0 nm, see

Table 2.

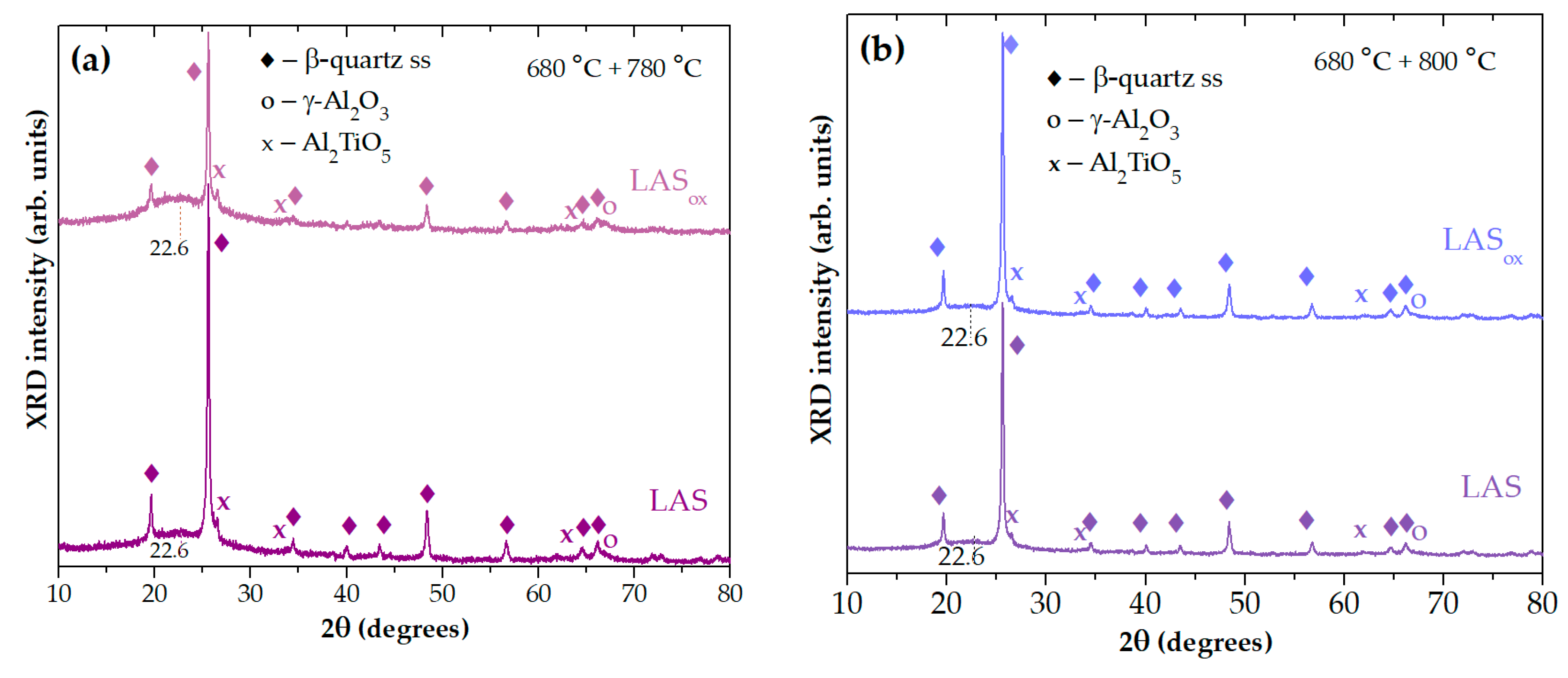

Figure 8(a) shows that in spite of the same phase assemblage of glass-ceramics obtained by two stage heat-treatment at 680 °С, 6 h+780° С, 6 h, the crystallinity fractions in the LAS glass-ceramic is much higher than in the LAS

ox one. This difference is levelled out by the heat treatment at 680 °С, 6 h+800° С, 6 h, see

Figure 8(b).

Table 2.

Lattice parameters and mean sizes of γ-Al2O3, β-quartz ss and β-spodumene ss in LAS and LASox glass-ceramics.

Table 2.

Lattice parameters and mean sizes of γ-Al2O3, β-quartz ss and β-spodumene ss in LAS and LASox glass-ceramics.

| Heat-treatment schedule |

γ-Al2O3

|

β-quartz ss |

β-spodumene ss |

|

a, Å |

D, nm |

a, Å |

c, Å |

D, nm |

a, Å |

c, Å |

D, nm |

| The LAS glass |

|---|

| 680 °С, 6 h+720° С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h+750 °С, 6 h |

7.918 |

4.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h+780° С, 6 h |

7.921 |

8.0 |

5.207 |

5.336 |

26 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +800 °С, 6 h |

7.925 |

14.0 |

5.196 |

5.350 |

25 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +850 °С, 6 h |

|

|

5.189 |

5.370 |

22 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +1000 °С, 6 h |

|

|

5.186 |

5.362 |

28 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +1100 °С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

7.552 |

9.145 |

45 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +1200 °С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

7.541 |

9.143 |

45 |

| The LASox glass |

| 680 °С, 6 h+720° С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h+750 °С, 6 h |

7.916 |

7.3 |

|

|

28 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h+780° С, 6 h |

7.915 |

9.4 |

5.207 |

5.319 |

26 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +800 °С, 6 h |

7.921 |

10.3 |

5.197 |

5.337 |

26 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +850 °С, 6 h |

|

|

5.192 |

5.365 |

21 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +1000 °С, 6 h |

|

|

5.187 |

5.368 |

27 |

|

|

|

| 680 °С, 6 h +1100 °С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

7.550 |

9.153 |

36 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +1200 °С, 6 h |

|

|

|

|

|

7.551 |

9.150 |

36 |

Table 3.

Lattice parameters and mean sizes of Al2TiO5 in LAS and LASox glass-ceramics.

Table 3.

Lattice parameters and mean sizes of Al2TiO5 in LAS and LASox glass-ceramics.

Heat-treatment

schedule |

Al2TiO5

|

| The LAS glass |

The LASox glass |

|

a, Å |

b, Å |

c, Å |

V, Å3

|

D, nm |

a, Å |

b, Å |

c, Å |

V, Å3

|

D, nm |

| 680 °С, 6 h+780° С, 6 h |

3.594 |

9.356 |

9.557 |

321.3 |

6.2 |

3.593 |

9.541 |

9.577 |

321.4 |

8.0 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +800 °С, 6 h |

3.595 |

9.365 |

9.564 |

322.0 |

7.1 |

3.594 |

9.358 |

9.577 |

322.1 |

8.7 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +850 °С, 6 h |

3.592 |

9.378 |

9.560 |

322.0 |

8.3 |

3.595 |

9.385 |

9.589 |

323.5 |

10.2 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +900 °С, 6 h |

3.596 |

9.373 |

9.570 |

322.6 |

9.0 |

3.594 |

9.418 |

9.619 |

325.6 |

12.0 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +950 °С, 6 h |

3.597 |

9.454 |

9.590 |

326.1 |

9.4 |

3.594 |

9.421 |

9.628 |

326.0 |

12.0 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +1000 °С, 6 h |

3.598 |

9.456 |

9.624 |

327.4 |

12.2 |

3.594 |

9.457 |

9.633 |

327.4 |

13.7 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +1100 °С, 6 h |

3.596 |

9.456 |

9.663 |

328.6 |

18.8 |

3.595 |

9.460 |

9.677 |

329.1 |

19.4 |

| 680 °С, 6 h +1200 °С, 6 h |

3.591 |

9.488 |

9.716 |

331.0 |

44.1 |

3.592 |

9.489 |

9.708 |

330.9 |

42.0 |

Figures 7(e,f) show the XRD patterns of glass-ceramics obtained by two stage heat-treatments with a second-stage temperature ranging from 850 °C to 1200 °C. After the heat-treatment at 850 °C the crystallinity fraction increases in such extent that amorphous halo disappears. Volume fractions of β-quartz ss and Al

2TiO

5 gradually increase. β-spodumene ss crystallizes at the expense of β-quartz ss at 1100 °C. Mullite (ICDD PDF card # 79-1458) appears at the same heat-treatment temperature.The lattice parameters and mean crystal sizes of β-quartz ss and β-spodumene ss are presented in

Table 2. Their variation with heat-treatment temperature is similar for the LAS and the LAS

ox glasses.

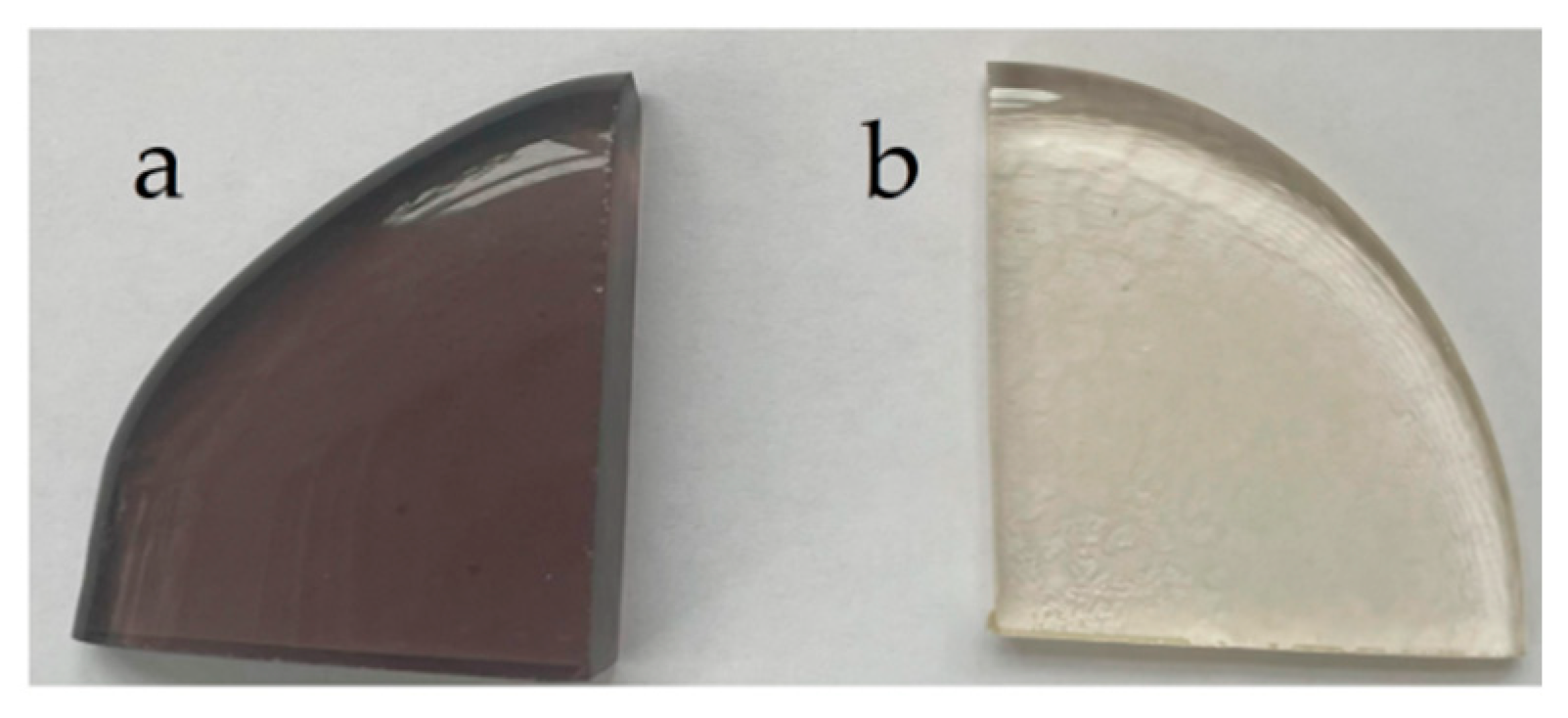

As we mentioned above, the appearance of the surface and the volume of the LAS glass-ceramics obtained by the heat-treatment at 1200 °C are different. The surface is a dense white-colored layer while the volume is grey colored, see

Figure 2. Traces of rutile (ICDD PDF card #78-1509) are found on the XRD patterns taken from the grey part of the LAS glass-ceramic. Appearance of rutile is acompanied by some decrease of the tieilite fraction. We failed to find a difference in the phase assemblages of the surface and volume of LAS

ox glass-ceramic obtained by the same heat-treatment. The XRD pattern shows a tiny fraction of rutile in this sample.

Let us discuss the features of crystallization of tieilite, Al

2TiO

5. As we mentioned above, the onset of crystallization of β-quartz solid solution in glasses at a temperature of 780 °C is accompanied by appearance of a small fraction of Al

2TiO

5 crystals with mean sizes of ~6 and 8 nm for LAS and LAS

ox glass-ceramics, respectively, see

Table 3. Increasing the heat-treatment temperature up to 1200 °C leads to an increase in the size of Al

2TiO

5 crystals up to ~40 nm, a slow increase in their fraction and a change in their lattice parameters, see

Table 3. The values of the lattice parameter a do not change with the heat-treatment temperature within the measurement error and are independent of the redox conditions of glass melting. Lattice parameters b, c and the volume increase with the heat-treatment temperature. An analysis of the evolution of lattice parameters shows that the lattice of Al

2TiO

5 unit cell, which has a shape of a rectangular parallelepiped elongated in [010] and [001] directions, becomes even more elongated in the same directions under the influence of high temperature. The lattice parameters of tieilite in LAS and LAS

ox glass-ceramics are similar as well as the character of their variation with temperature. The redox conditions of glass melting do not influence significantly the structural transformations in tieilite crystals. A pronounced change in lattice parameters after the heat-treatment at 1200 °C found in the present study can be a prerequisite to decomposition of tieilite with exsolution of rutile [

54]. Indeed, as we mentioned above, traces of rutile are found in LAS

ox and in the volume of the LAS glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatment at 1200 °C. The comparison of XRD patterns of the LAS and the LAS

ox glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatment at 1200 °C demonstrates that LAS

ox glass-ceramic contains a smaller fraction of rutile and a higher fraction of mulite than the LAS glass-ceramic, compare Figures 7(e,f).

The sequence of phase transformations revealed by XRD study is similar for both glasses: initial glasses and glasses heat-treated at the nucleation stage are X-ray amorphous; nanocrystals of γ-Al2O3 with spinel structure and sizes ranging from 4.5 nm to 14 nm evolve during heat-treatments in the second stage in the temperature range from 720 °C to 800 °C; the main crystalline phase, β-quartz ss, and the crystalline phase of the nucleating agent, tieilite, appear additionally to spinel during the heat-treatment at 780 °C; β-quartz ss are obtained by heat-treatments in the temperature range from 780 °C to 1000 °C; the glass-ceramic prepared by the heat-treatments at 1100 °C contains β-spodumene ss instead of β-quartz ss and traces of mullite; β-spodumene ss is the main crystalline phase of glass-ceramics produced by heat-treatments in the temperature range from 1100 °C to 1200 °C; tieilite nanocrystals with the mean size ranging from ~6 nm to ~45 nm are found in glass-ceramics prepared in the temperature range from 800 °С to 1200 °C; during the heat-treatment at 1200 °C, the crystals of rutile appear in the phase assemblage of glass-ceramics.

In spite of the same phase assemblage of glass-ceramics obtained from glasses melted in different redox conditions, the kinetics of phase transformations and spinel lattice parameters are slightly different. The spinel lattice parameters in the LAS glass-ceramics are larger than in the LASox glass-ceramics. The crystallinity fractions in the LAS glass-ceramic obtained by two stage heat-treatment at 680 °С, 6 h+780 °С, 6 h is much higher than in the LASox one. However, this difference is levelled out by the heat treatment at 680 °С, 6 h+800° С, 6 h. The rutile crystallinity fraction in the LAS glass-ceramics is larger than in the LASox one, while the mullite fraction is smaller.

3.3 Raman Spectroscopy

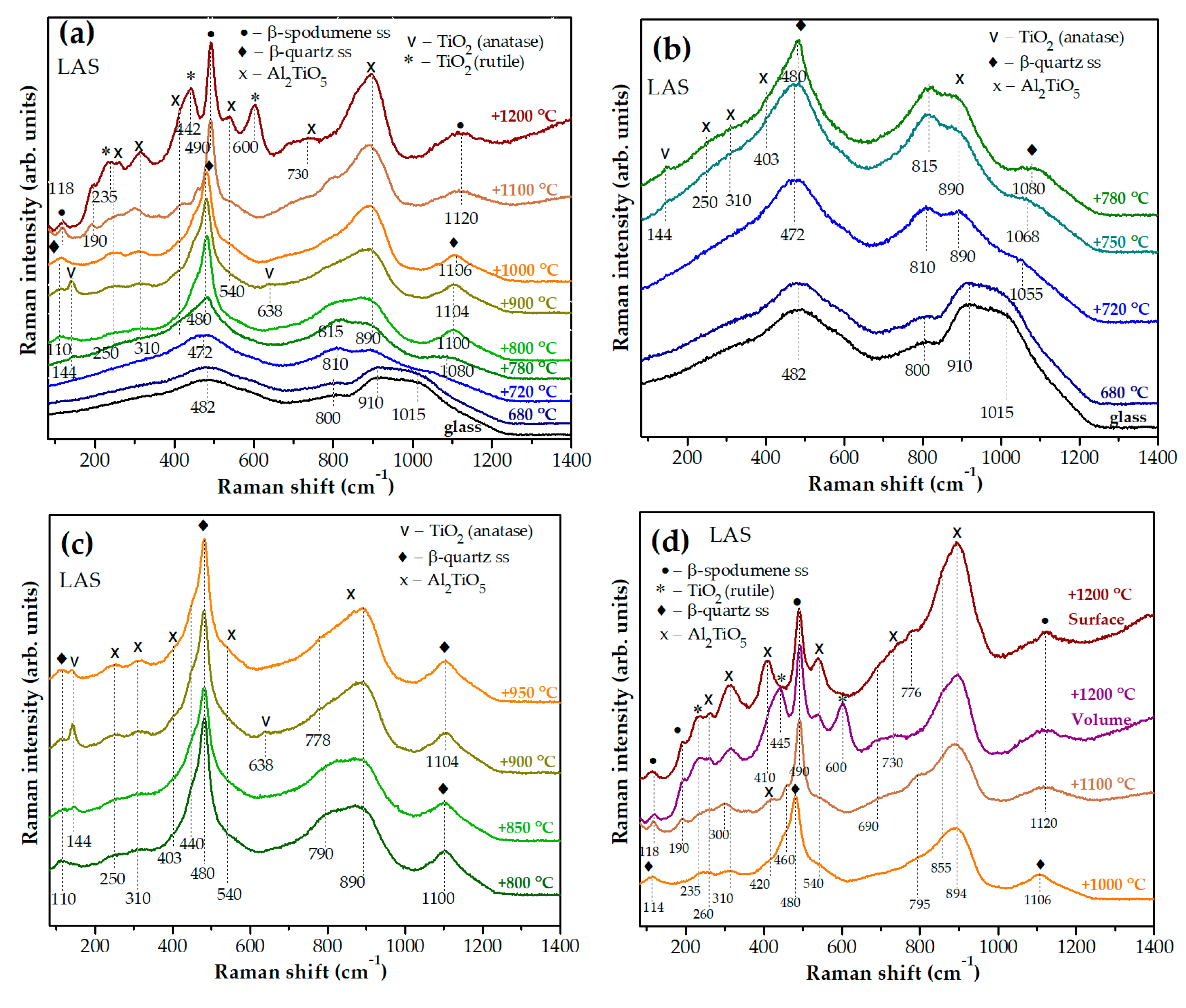

Figures 9(a,b) show Raman spectra of the initial and heat-treated LAS glass. Raman spectra of initial LAS and LAS

ox (not shown here) glasses are similar and contain broad bands with maxima at 482 cm

-1, 800 cm

-1, 910 cm

-1 and ~1015 cm

-1. The wing of the latter band extends to 1200 cm

-1. The similar spectrum was obtained in ref. [

27] for the glass of the same composition nucleated by 7 mol% TiO

2 and melted in oxidizing conditions. The bands at 482 cm

-1, 800 cm

-1, and ~1000–1200 cm

-1 are due to vibrations of bonds in the tetrahedrons of the aluminosilicate network in the glass structure [

55], and the band at ~910 cm

-1 is due to vibrations of [TiO

4] tetrahedra embedded in this network [

56]. After the heat-treatment at the nucleation stage at a temperature of 680 °C, minor changes are noticed in the Raman spectrum, see

Figure 9(a,b). The high-frequency band slightly broadens and the band with a maximum at 800 cm

-1 somewhat increases in intensity compared to the band with a maximum at 910 cm

-1, which indicates the development of liquid-liquid phase separation of the initial glass [

27]. The position of the band at 482 cm

-1 does not change with this heat-treatment.

After the two stage heat-treatment with a temperature of 720 °C at the second stage, significant changes are observed in the Raman spectrum, see Figures 9(a,b). The bands with maxima at 910 cm

-1, 800 cm

-1, and 482 cm

-1 move their positions to 890 cm

-1, 810 cm

-1, and 472 cm

-1, respectively. Instead of the band with a maximum at ca. 1015 cm

-1, a band at 1055 cm

-1 appears. Intensity of the band at 472 cm

-1 increases as compared with the similar band in spectra of the initial glass and glass heat-treated at the nucleation stage. Intensity of the band at ~810 cm

-1 increases relatively to the band at ca. 890 cm

-1. The increase in the intensity of this band at the expence of the band with a maximum at ca. 890 cm

-1 is due to the superposition of vibrations of the [TiO

5] and [TiO

6] groups in amorphous aluminotitanate regions on a weak band in the 800 cm

-1 region, corresponding to vibrations of the tetrahedrons of the aluminosilicate network [

30]. These changes are associated with a further development of the liquid-liquid phase separation with the formation of aluminotitanate amorphous regions [

27] and a change in the composition of the aluminosilicate glass network, which is in accordance with a change in the position of amorphous halo in the corresponding XRD pattern, see

Figure 7(c). Crystallization of γ-Al

2O

3 with spinel structure revealed by XRD analysis does not show itself in the Raman spectrum of this glass-ceramic. Running ahead, we will say that spectral features of γ-Al

2O

3, were not detected in Raman spectra of samples obtained by heat-treatments from 750 °C to 800 °C as well, in spite of the fact that XRD analysis reliably identified them. The reason is that bond vibrations in aluminate spinel crystals are very weak compared to bond vibrations in titanium-containing compounds. According to refs [

57,

58], γ-Al

2O

3 exhibits narrow peaks with maxima at 315, 410, 520, 713 and 835 cm

−1 in the Raman spectrum of γ-Al

2O

3 corresponding to vibrations of the Al–O bond in tetrahedral structural units of AlO

4 [

57]. Based on calculations presented in ref. [

59], the strongest Raman peak for γ-Al

2O

3 with spinel structure is located at ~401 cm

−1. There are also several bands of medium intensities ranging from 100 cm

−1 to 900 cm

−1 [

59]. In Raman spectra presented in

Figure 9(b) there is the band with the maximum at 403 cm

-1, which could be the spectroscopic sign of γ-Al

2O

3. However, this band can be also caused by vibrations in tieilite crystals because this band appears simultaneously with other bands at 250 cm

-1, 310 cm

-1, and 890 cm

-1 characteristic of tieilite, which crystallizes in a larger temperature range of heat-treatments than γ-Al

2O

3 (see below). We will just mention that we were able to find the spectroscopic signs of crystals with spinel structure only in Raman spectra of spinel-based glass-ceramics of magnesium [

60] and zinc aluminosilicate systems [

44], where the spinel crystallinity fraction was significantly higher than in the present case.

In the Raman spectrum of the glass-ceramic obtained by the heat-treatment at the second stage at a temperature of 750 °C, the bands with maxima at 472 cm

-1 and 815 cm

-1 are enhanced, positions of the band maxima change from 810 cm

-1 to 815 cm

-1 and from 1055 cm

-1 to 1068 cm

-1, and a very weak band appears at ~144 cm

-1. The latter peak can be attributed to the most intense vibration in the Raman spectrum of the metastable modification of TiO

2, anatase [

25].

In the Raman spectrum of the sample obtained by the heat-treatment at the second stage at a temperature of 780 °C, the band at ~144 cm

-1, caused by vibrations in anatase nanocrystals, narrows, the band at 480 cm

-1 narrows and intensifies, and the band at ~1080 cm

-1 appears. The last two bands are related to vibrations in crystals of β-quartz ss [

25,

27,

61,

62]. As we mentioned above, in the spectrum of this glass-ceramics there is a number of bands with maxima at 250 cm

-1, 310 cm

-1, 403 cm

-1, 540 cm

-1, and 890 cm

-1. They appear simultaneously, and their intensities increase continuously with increasing temperature of heat-treatment. These bands belong to vibrations in tieilite crystals [

27], which is in accordance with the XRD data. The Raman spectrum of glass-ceramic obtained by the heat-treatment with a temperature of 900 °C at the second stage shows two anatase bands at ~144 cm

-1 and ~638 cm

-1 manifesting the maximum anatase crystallinity fraction achieved by this heat-treatment, see Figures 9(a,c). After increasing the heat-treatment temperature at the second stage to 1000 °C, the bands related to anatase disappear. Note that the XRD peaks of anatase coincide in position with the main peaks of β-quartz ss and its small amount cannot be detected by the XRD data [

25,

47].

As the temperature at the second stage of heat-treatment increases, intensities of the bands at ~460 cm

-1 and ~1080 cm

-1 increase, their peaks become narrower, see

Figure 9(c), which indicates the development of β-quartz ss crystallization. Their positions constantly move to longer wave numbers manifesting enrichment of these crystals with silica [

62]. After the second stage heat-treatment at 1100 °C, these bands shift to 490 cm

-1 and 1120 cm

-1, which can be interpreted as recrystallization of β-quartz ss into β-spodumene ss [

47]. Starting from the heat-treatment at 800 °C, a weak band appears at 110 cm

-1 simultaneously with increasing intensity and narrowing the bands attributed to β-quartz ss. According to ref. [

63], this band can correspond to external vibrations in crystals of β-quartz ss [

64]. In Raman spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at 1100 °C and at 1200 °C, weak bands at ~118 cm

−1 and ~190 cm

−1 were observed that can be attributed to external vibrations in crystals of β-spodumene ss [

61,

63], see

Figure 9(d).

Figure 9(d) shows the bands at ~260 cm

-1, ~445 cm

-1 and ~600 cm

-1, which are related to crystallization of rutile [

65] at the expense of tieilite in the bulk of glass-ceramic obtained by the heat-treatment at a second stage at 1200 °C. We did not find the signs of rutile crystals in the spectrum from the white surface of this sample, which is in accordance with XRD data. XRD patterns of glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at 1100 °C and 1200 °C contain small mullite fractions, see

Figure 7(e,f). Raman spectra of synthetic mullites of different compositions have similar spectra with the strongest bands located at 415 cm

-1, 600 cm

-1, and 980 cm

-1 [

66]. They can be hidden in the contours of the corresponding broad bands in Raman spectra, see

Figure 10(f).

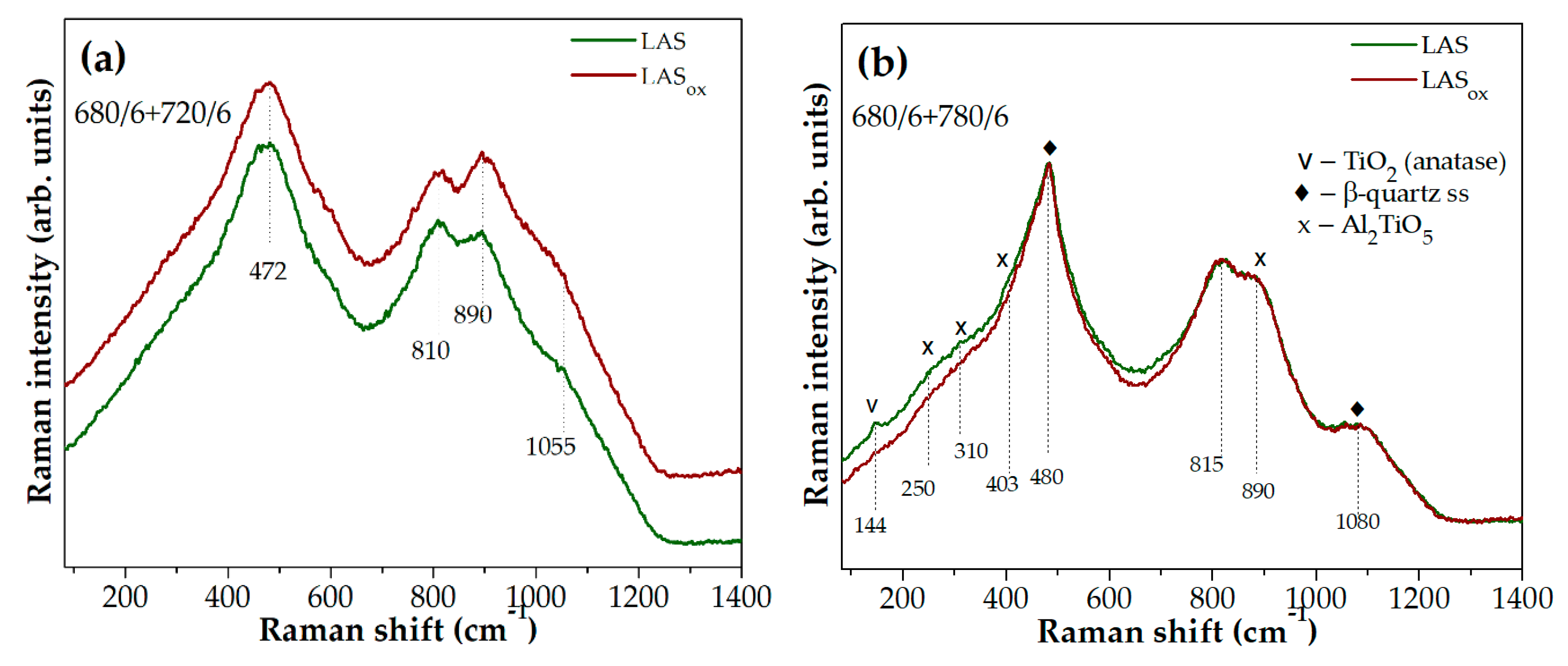

Raman spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by the same heat-treatments that differ most strongly from each other according to Raman spectroscopy data are presented in Figures 10(a-f). Raman spectra of initial glasses, as well as spectra of glasses heat-treated at 680 °C for 6 h are similar to each other, and they are not shown here. The spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by the two stage heat-treatment at 680 °C and at 720 °C for 6 h differ from each other by the ratio of band intensities in the region of high wave numbers, see

Figure 10(a). The increase in the relative intensity of the band with a maximum at 800 cm

-1 compared to the intensity of the band at 890 cm

-1 in the spectrum of the LAS glass-ceramic suggests that the rate of liquid-liquid phase separation in this glass during this heat-treatment is higher than that in the LAS

ox glass, i.e., neutral conditions of glass melting speed up the development of liquid-liquid phase separation in this glass. Crystallization of titanate phases of anatase and tieilite are speeded up in the LAS glass ceramized by the heat-treatment at the second stage at 780 °C as compared with the LAS

ox glass, see

Figure 10(b). The same tendency remains true for glass-ceramics obtained by the heat-treatment with the second stage at 900 °C, see

Figure 10(c). The higher intensity of the anatase peaks in the Raman spectrum of the LAS

ox glass-ceramic obtained by heat-treatment at 950 °C, see

Figure 10(d), means that anatase crystallization in the LAS

ox glass reaches its maximum and will decrease at higher temperatures while the maximum anatase content in the LAS glass-ceramics was reached at previous holding temperature. The traces of anatase crystals remain in the LAS

ox glass-ceramic obtained by heat-treatment at 1000 °C while the LAS glass-ceramic does not show spectral features of this phase, and intensities of peaks assigned to tieilite crystals are higher for the LAS glass-ceramic than for the LAS

ox one, see

Figure 10(e).

Figure 10(f) shows that the LAS glass-ceramic prepared by heat-treatment at 1200 °C demonstrates rutile bands of higher intensities as compared with the LAS

ox glass-ceramic.

Though Raman spectra of initial glasses and spectra of glasses heat-treated at 680 °C for 6 h are similar to each other, comparison of Raman spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by two stage heat-treatments unambiguously indicates that, despite the fact that the sequence of phase transformations in the titania-containing phase is independent of the redox conditions of glass melting, the rate of these transformations is significantly higher at ceramming of the LAS glass.

3.5. Morphology Characterization by SEM

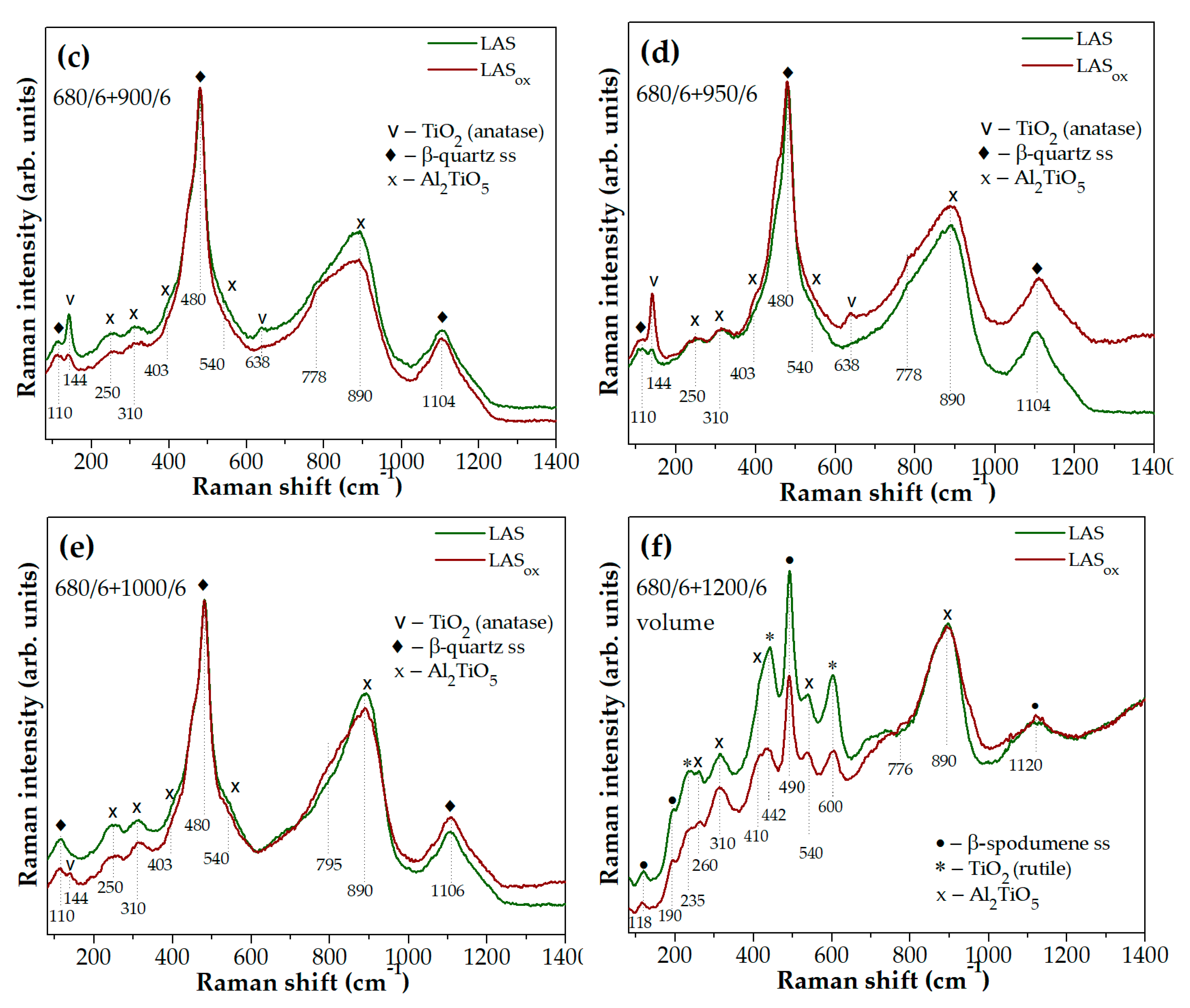

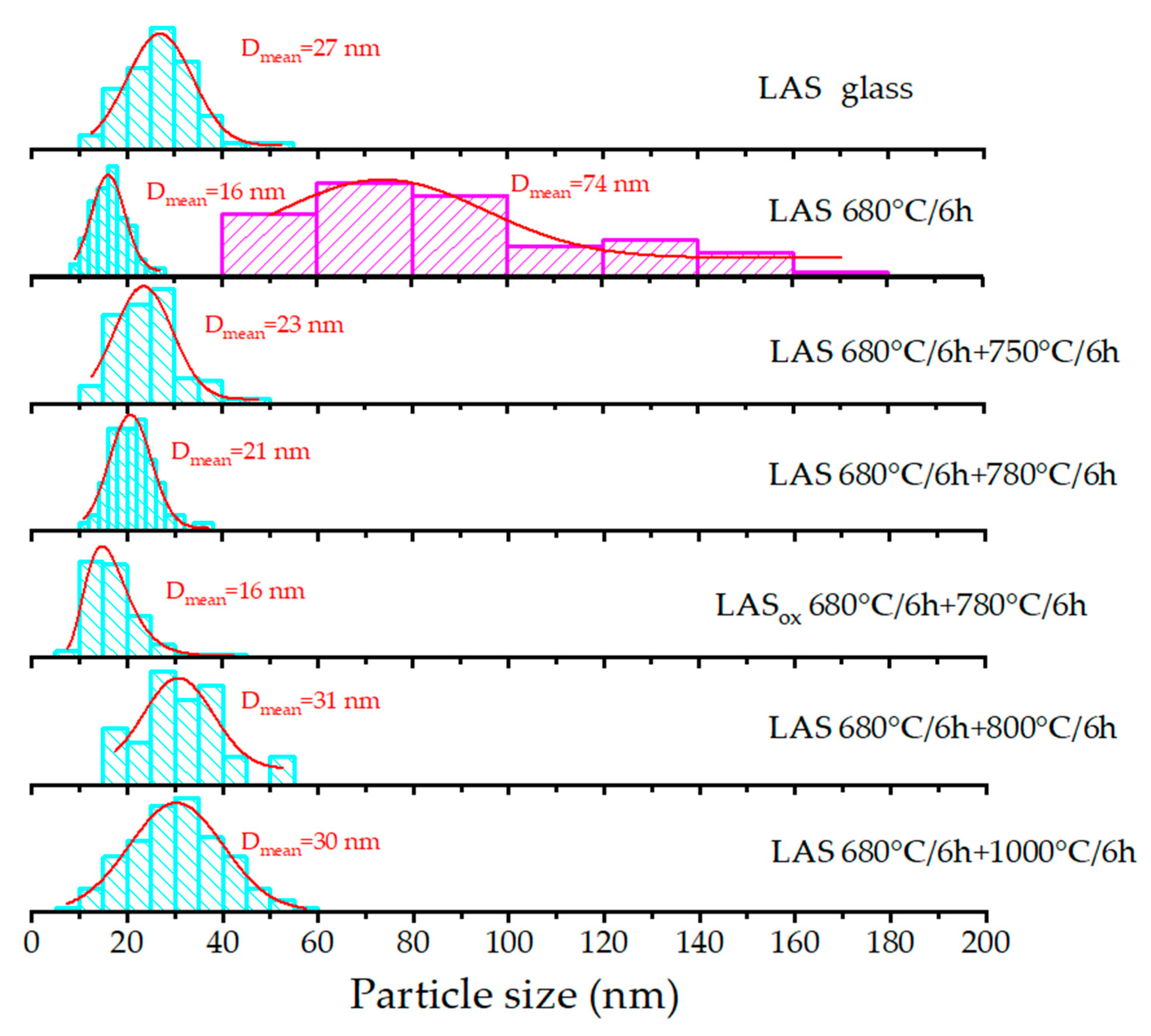

SEM analysis (

Figure 11(a)) reveals the presence of inhomogeneous regions within the bulk of the initial amorphous LAS glass. The calculated size distribution shows a broad profile, with the mean size of the inhomogeneous regions being approximately 27 nm (

Figure 12). These inhomogeneities may indicate liquid-liquid phase separation during the glass formation. The broad size distribution may arise from overlapping size distributions of chemically distinct regions. Such regions are likely precursors to the crystallization of various phases upon subsequent heat-treatments.

Following the single step heat-treatment at 680 °C for 6 h, the LAS glass remains X-ray amorphous. However, its SEM image (

Figure 11(b)) shows increased inhomogeneity, clearly distinguishing two types of regions. The first type consists of small, spherical, bright regions with a narrow size distribution averaging 16 nm (

Figure 12). The second predomonant type features larger, irregular, dark regions with an average size of 74 nm (

Figure 12).

After two stage heat-treatment at 680 °C for 6 h and 750 °C for 6 h, the large inhomogeneous regions are not seen on the SEM image anymore. Numerous spherical particles appear in the SEM image of the LAS glass-ceramic, averaging 23 nm in size (

Figure 11(c)). The broad shape of the size distribution suggests overlap from multiple chemically distinct particle populations, see

Figure 12. XRD analysis confirms crystallization of the spinel phase with mean crystal size of 4.5 nm.

The heat-treatment at 680 °C for 6 h and 780 °C for 6 h promotes significant crystallization of the LAS glass. The SEM image of this glass-ceramic is shown in

Figure 11(d). XRD analysis confirms formation of three crystalline phases, β-quartz ss, spinel, and Al

2TiO

5, see

Figure 7(c), with mean crystal sizes of 8 nm, 26 nm and ~6 nm, respectively, see

Table 2 and

Table 3. The particle size distribution suggests the possible overlap of multiple size distributions corresponding to different phases, see

Figure 12. The mean particle size is approximately 21 nm, which is close to the mean size of the predominant crystalline phase of β-quartz ss.

The two step heat-treatment at 680 °C and 800 °C for 6 h results in more extensive crystallization of the LAS glass, see

Figure 7(e). XRD analysis confirms the presence of crystalline phases of β-quartz ss, spinel, and Al₂TiO₅. The SEM image reveals significant etching of the material, characterized by numerous large caverns, which may indicate silica depletion, see

Figure 11(f). The mean particle size is 31 nm, see

Figure 12, which is also close to the mean size of the predominant crystalline phase of β-quartz ss, which is 25 nm, see

Table 2.

Following the two step heat-treatment at 680 °C and 1000 °C for 6 h, XRD analysis shows the formation of β-quartz ss, mullite, and Al

2TiO

5. Signs of the residual glass phase become less prominent. The particle size distribution, similar to previous samples, exhibits a broad profile, likely due to overlapping distributions from different phases, with an average particle size of 30 nm. The size of the predominant crystalline phase of β-quartz ss is 28 nm, see

Table 2.

Finally, after two step heat-treatment at 680 °C and 1200 °C for 6 h, the SEM image of the opaque LAS sample shows the presence of micron-sized, needle-like crystals and agglomerates of spherical crystals, see

Figure 11(h). The needle-like crystals are very similar to crystals of β-spodumene ss that were crystallized in the lithium aluminosilicate glass of a different composition during its heat-treatment at 1350 °C [

19]. XRD analysis confirms the crystallization of β-spodumene (ss), mullite, and Al

2TiO

5 phases, see

Figure 7(e).

The influence of redox conditions of glass melting on phase assamblage of glass-ceramics is revealed by the comparison of SEM images of LAS and LAS

ox glass-ceramics obtained by the heat-treatment at 680 °C and 780 °C for 6 h. In accordance with XRD data, see

Figure 8(a), the SEM image of the LAS

ox glass-ceramic shows a significantly reduced extent of crystallization, see

Figure 11(e). The particle size distribution for this sample also indicates overlapping distributions, with a mean particle size of 16 nm, which is smaller than the mean particle size of the LAS glass-ceramic.

Considering that the main contribution to the increase in mean crystal size comes from larger crystals of β-quartz ss, the smaller mean crystal size in the LASox glass-ceramic indicates a smaller number of these crystals.

3.4. Optical Spectroscopy

Light losses in phase separated glasses and glass-ceramics are determined by absorption due to coloring ions and light scattering on the interfaces of regions of inhomogeneity inherent for such materials. It is generally accepted that coloration of glass-ceramics containing titania as a nucleating agent is mainly caused by intervalent charge transfer transitions between titanium and iron impurity ions in different oxidation states [

13,

67]. Though we cannot exclude the influence of absorption due to the Fe

3+-Ti

3+ and Fe

2+-Ti

4+ intervalence charge transitions on absorption spectra of our materials, we restricted ourselves to the consideration of absorption due to titanium ions. Similar approach was suggested in [

67]. Titanium ions can be found in glasses in two oxidation states. The presence of Ti

3+ and Ti

4+ ions, and Ti

3+-Ti

4+ pairs defines absorption of glasses under study. Ti

4+ ion has electronic configuration 3d

0 and does not demonstrate absorption bands due to d-d transitions in the ligand field. Ti

4+ ions participate in O-Ti

4+ charge transfer bands located in the UV spectral range at ~300 nm [

68] and in intervalence charge transfer Ti

4+-Ti

3+ transitions responsible for coloration in the visible spectral range [

69]. Ti

3+ ions have electronic configuration 3d

1 and demonstrate one broad absorption band in the visible spectral range due to the

2T

2g → E

g transition of the Ti

3+ ions in octahedral site symmetry. The band often has a shoulder at the long-wavelength side of the absorption band caused by the Jahn–Teller effect [

31,

33,

34,

35,

69]. The absorption band of Ti

3+ ion in tetrahedral (T

d) coordination caused by the E

g →

2T

2g transition is located in the near infrared region of the spectra [

69]. The O-Ti

3+ charge transfer band is expected in UV spectral range at ~240 nm [

68].

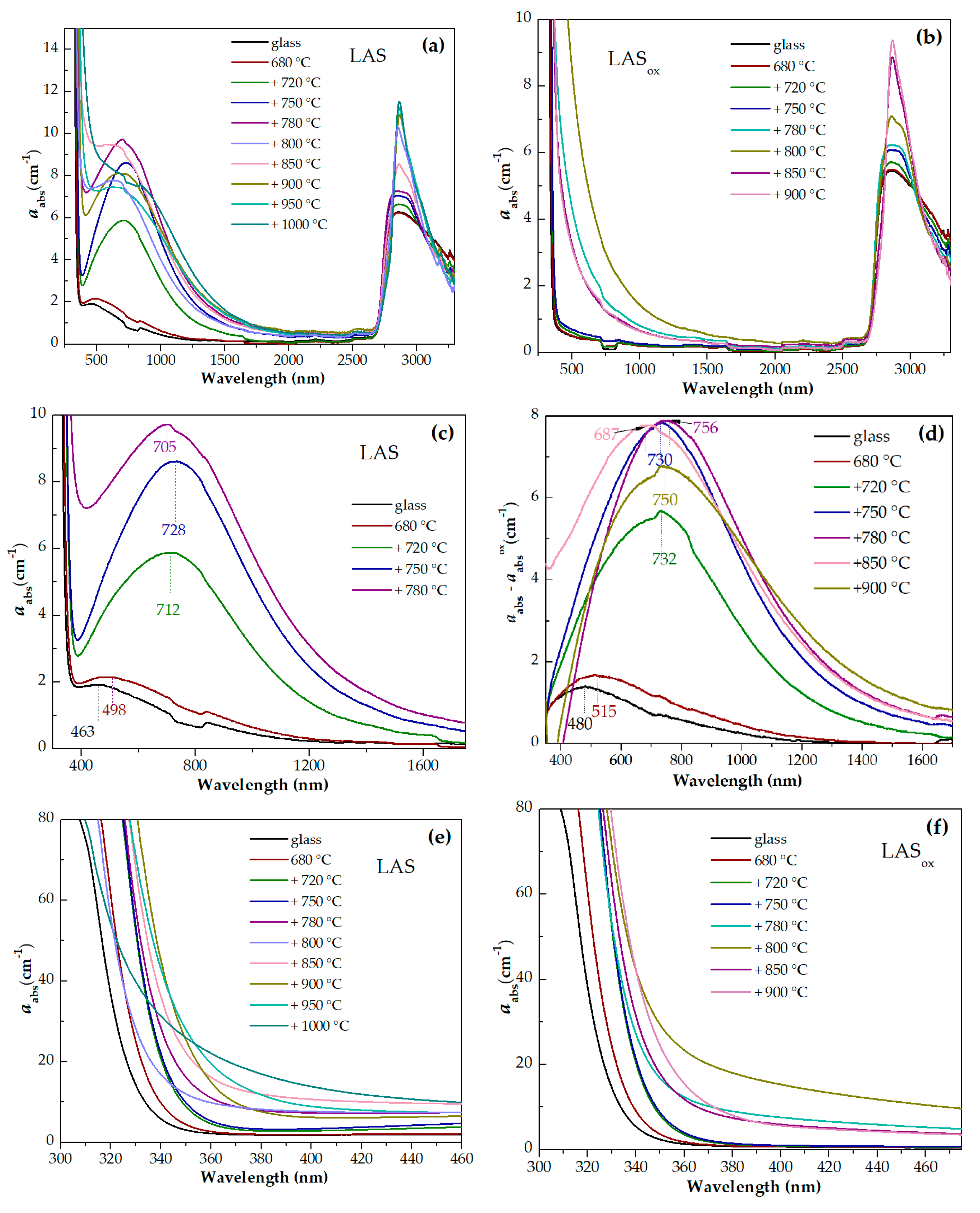

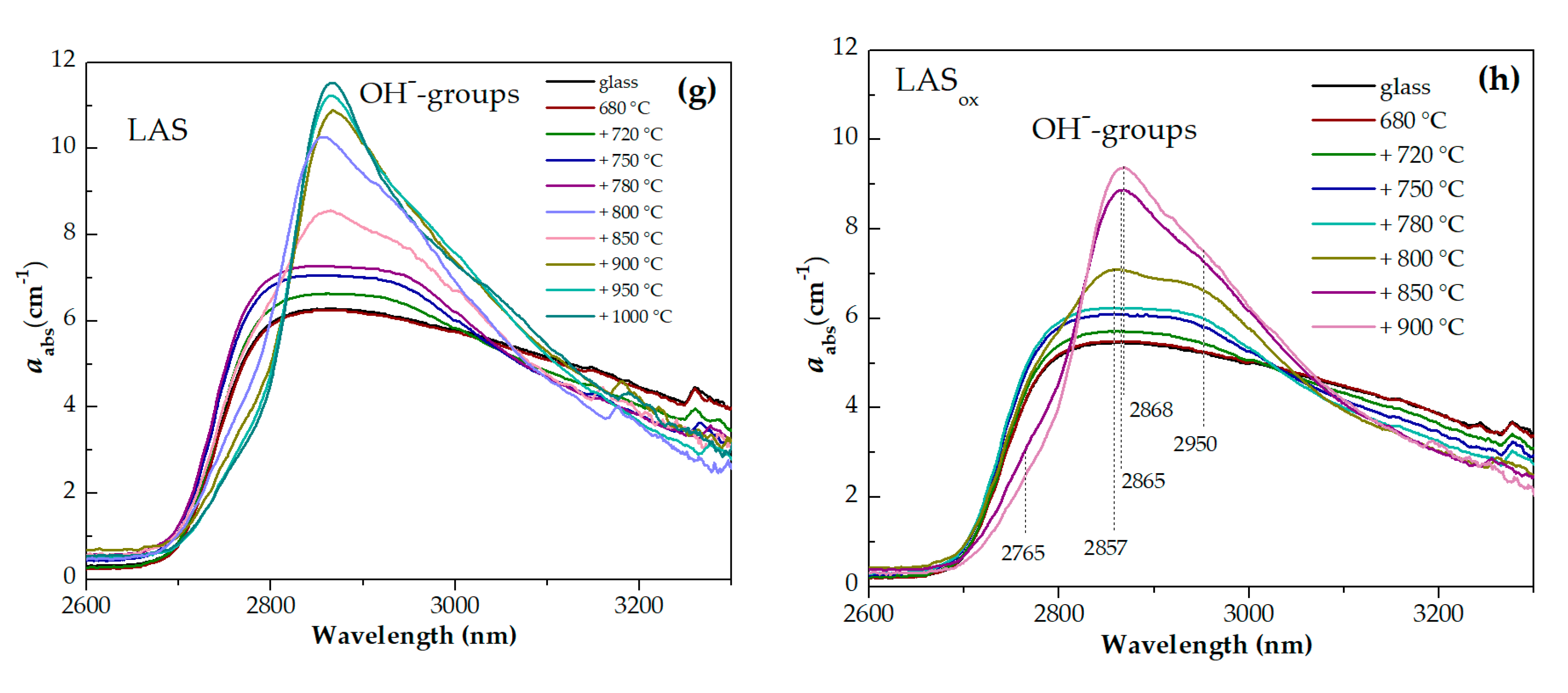

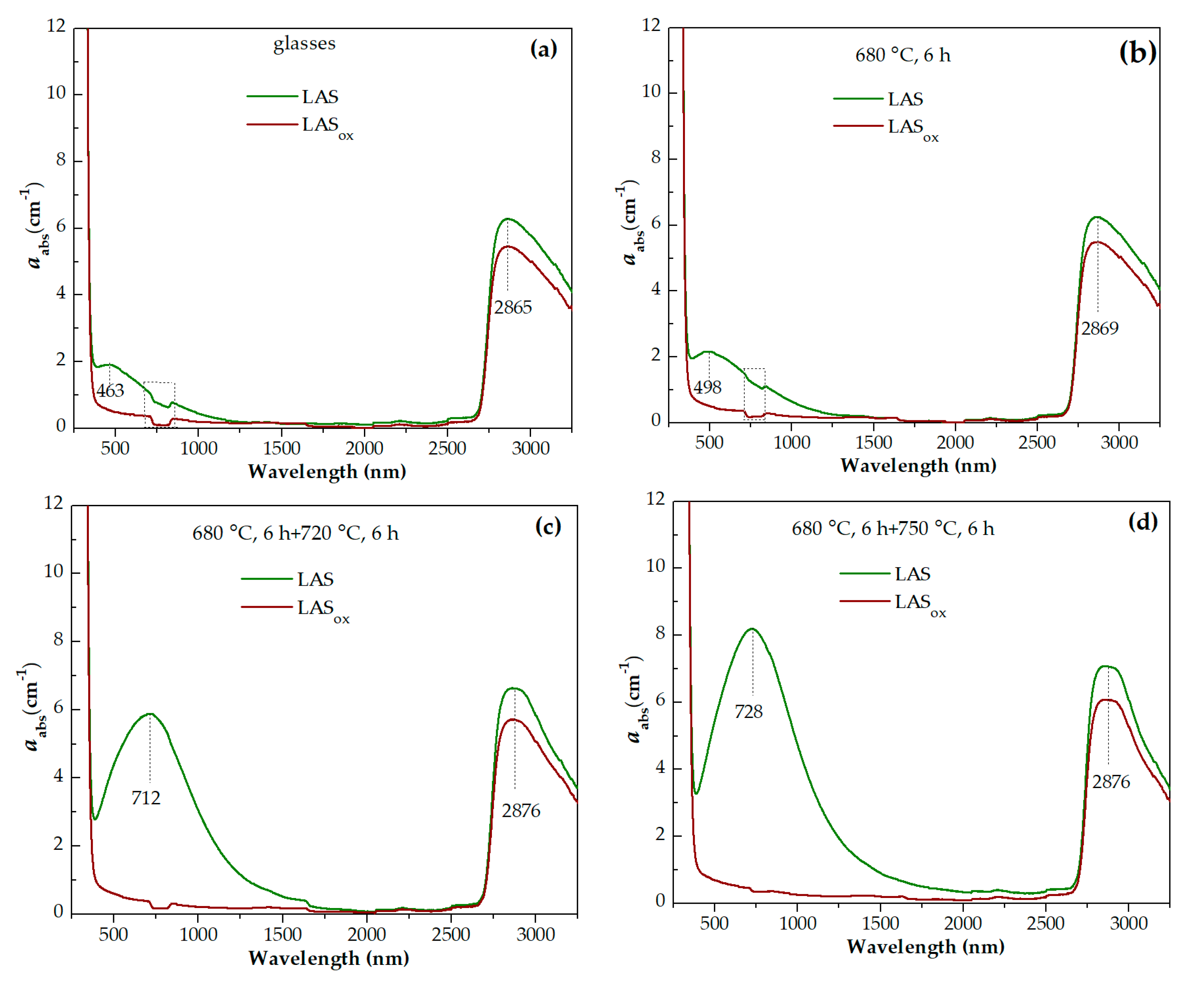

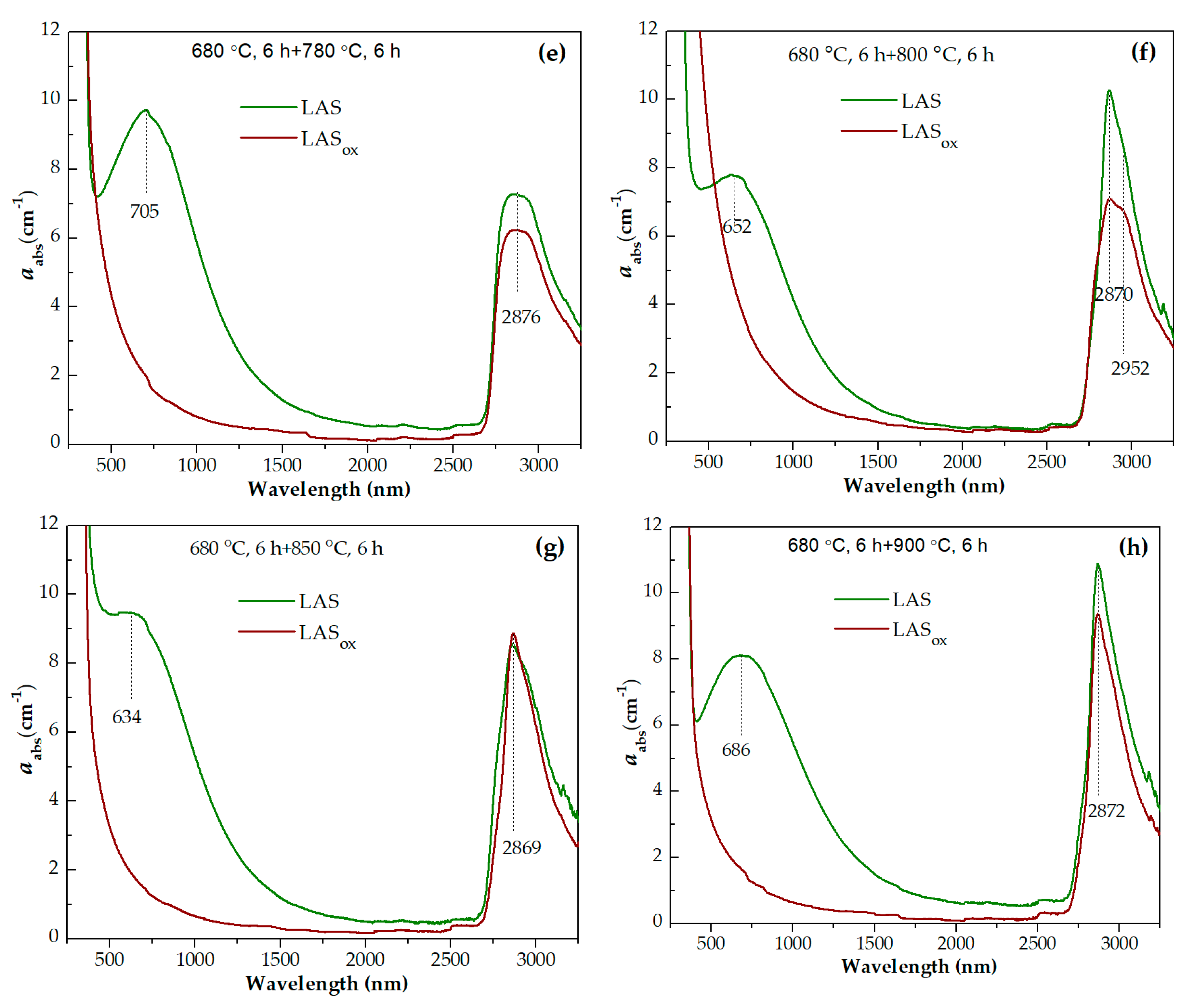

Absorption spectra of initial and heat-treated glasses are shown in

Figure 13a–g. For the convenience of comparison, the spectra of the LAS and LAS

ox glasses and glass-ceramics obtained by the same heat-treatment schedule are presented in Figures 14(a-h). The spectra are formed by the absorption edge in the UV spectral range, see Figures 13(d,e), intense absorption of OH- groups spanning from 2700 nm to 3300 nm, see Figures 13(f,g), and light losses in the visible and near IR spectral range, see Figures 13(a-c), which have different origin in the LAS and the LAS

ox glass-ceramics. Note that the LAS

ox glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at 950 °C and 1000 °C at the second stage cracked during heat-treatment, and their spectra were not recorded.

For the initial LAS glass, the UV absorption edge is observed at ~330 nm. In the spectrum of the glass heat-treated at the nucleation stage at 680 °C for 6 h it moves to longer wavelengths by 5 nm. In the spectrum of glass-ceramics obtained by the two stage heat-treatment with the temperature of 720 °C at the second stage, the position of the absorption edge is found at ~343 nm and has near the same position after heat-treatments at 750 °C and 780 °C. After heat-treatment with the temperature of 800 °C at the second stage, the absorption edge shifts to shorter wavelengths, to 334 nm. After increasing the temperature of the second stage to 850 °C and 900 °C, the absorption edge shifts again to longer wavelengths. Its position is equal to 347 nm and 351 nm, respectively. After heat-treatments at 950 °C and 1000 °C, the position of the absorption edge shifts again to shorter wavelengths, see

Figure 14(d).

The position of the absorption edge for the LAS

ox glass and its variation with the heat-treatment temperature are surprisingly similar to those of the LAS glass, see

Figure 14(a-e,g,h). The position of the absorption edge differs only for glass-ceramics obtained by the heat-treatment at the second stage at 800 °C, see

Figure 14(f). The absorption edge in the spectrum of this LAS

ox glass-ceramic is shifted to longer wavelengths compared to its position in the spectrum of the LAS sample. The nonmonotonic transmittance variation during the crystallization of glasses inclined to liquid-liquid phase separation was described in ref. [

70] and assigned to incoherent scattering that takes place in a material containing amorphous and crystallized regions of inhomogeneity. The authors of ref. [

70] demonstrated that the extinction coefficient can reach a maximum when the crystallinity fraction is 0.5–1.0 and then decrease due to the presence of elements of ordering in the relative position of the crystals.

We used the same raw materials for the preparation of both glasses, which means that the iron content in both glasses was similar. The absorption edge in initial glasses and in glass-ceramics is formed by O

2-→Ti

4+ and O

2-→Ti

3+ charge transfer bands [

68]. Taking into account that O

2-→Ti

4+ charge transfer band is located at longer wavelengths than the O

2-→Ti

3+ one, we may suggest that the content of Ti

4+ ions in the LAS and the LAS

ox glasses is very similar, i.e., the content of Ti

3+ in the LAS glass is rather low. In glass-ceramics containing β-quarts ss scattering losses are superimposed with the absorption edge.

A broad absorption band is found in the spectrum of the LAS glass. Its intensity increases after heat-treatment at the nucleation stage and with increasing the heat-treatment temperature at the second stage up to 780 °C, see

Figure 13(c). After further heat-treatments the absorption band becomes broader, its intensity somewhat decreases. We explain appearance of this absorption band by Ti

3+ ions distributed between different amorphous and crystalline phases. Since the absorption edge and light scattering in the obtained multiphase materials are superimposed on the short-wave part of the absorption spectrum, we subtracted absorption due to these losses from experimental absorption spectra of the LAS samples using the corresponding absorption spectra of LAS

ox samples for substraction. The difference spectra are shown in

Figure 13(d). The spectrum of the initial glass is a typical absorption spectrum of Ti

3+ ions in silicate glasses with a broad peak with a maximum at ~480 nm attributed to d-d transition

2T

2g→

2E

g of 3d

1 electron of Ti

3+ ions in octahedral coordination in the ligand field affected by the Jahn-Teller effect [

33,

34,

35]. The tail with a maximum at ~800 nm is assigned to intervalence charge transfer in Ti

3+-Ti

4+ pairs [

71,

72]. The absorption intensity increases after the heat-treatment at the nucleation stage, the band maximum shifts to ~500 nm, which is connected with participation of Ti

3+ ions in the liquid-liquid phase separation and entering the aluminotitanate amorphous regions. With increasing the heat-treatment temperature at the second stage, the broadband absorption in the visible and near-IR region intensifies, its maximum shifts to ~730 nm in spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at 750 °C and 780 °C at the second stage. Similar to absorption of Ti

3+ ions in corrund crystals [

73,77] we attribute this absorption to Ti

3+ ions in the ligand field of octahedral symmetry (the shoulder at ~480 nm) and Ti

3+-Ti

4+ pairs in crystals of γ-Al

2O

3. In the spectrum of corrundum, the Ti

4+ ions in Al

3+ sites are considered to be charge-compensated by Al vacancies with one vacancy for every three Ti

4+ ions [

74]. An increase of the lattice parameters of γ-Al

2O

3 with heat-treatment temperature found by the XRD analysis can be due to entering the crystals of γ-Al

2O

3 by Ti

3+ ions (ionic radius in octahedral coordination is 0.81 Å) and Ti

4+ ions (ionic radius in octahedral coordination is 0.745 Å). Note that ionic radii of Al

3+ in octahedral coordination is 0.675 Å.

The shape of the absorption band changes with raising the heat-treatment temperature. Judging by the shape of the absorption band, the spectrum is still mainly formed by absorption of Ti3+-Ti4+ pairs. Taking ino account crystallization of β-quartz ss and tieilite, Al2TiO5, this change of the shape of absorption band can be connected with distribution of titanium ions between the crystalline phases. Spinel does not crystallize in glass-ceramics obtained by heat-treatments at 850 °C – 1000 °C at the second stage. So the broadband spectra of glass-ceramics obtained by these heat-treatments are connected with titanium ions in β-quartz ss and tieilite.

The light losses in the LASox glass-ceramics are mostly caused by light scattering, which has a non-monotoneous dependence on the heat-treatment temperature, as we mentioned above.

Figures 13(f,g) show wide asymmetric absorption bands in the spectral region from ~2700 nm to 3300 nm caused by the presence of OH-groups in glasses and glass-ceramics. Heat-treatment at the nucleation stage at 680 °C for 6 h has no effect on the shape and intensity of this band. Two stage heat-treatments with temperature from 720 °C to 780 °C at the second stage cause a successive change in the spectrum of OH-groups. The intensity in the range from 2750 nm to 3050 nm increases and the intensity in the range from 3050 nm to 3300 nm decreases. Further narrowing of the OH-groups absorption band and growth of its intensity is observed in spectra of glass-ceramics obtained during heat-treatments in the range of crystallization temperatures from 800 °C to 1000 °C. Comparison of the absorption bands of OH-groups in glasses melted in different redox conditions and in corresponding glass-ceramics showed that the intensities of the absorption bands of OH-groups are higher in inital and heat-treated LAS glass than in LASox samples. The shape of the absorption band is the same for the materials obtained by the same heat-treatment shedule, see Figures 14(a-h), which is explained by a similarity of their phase compositions.