1. Introduction

Since plastic was introduced into the global market in the 20th century, it has gained a positive response and dominated over other materials (Williams & Rangel, 2022). Their great functional value stems from their superior physical, mechanical, and thermal qualities; nonetheless, their non-biodegradable nature undermines their utility in environmental sustainability (Ncube et al., 2019). Plastic is mainly produced from fossil fuels, which are non-renewable sources and negatively impact the environmental ecosystem (Geyer et al., 2017). In particular, plastic packaging is well recognized as a contributor to the worldwide concern of plastic waste, its associated adverse environmental consequences, and global warming (Kumar et al., 2021). Solving these problems will need widespread implementation of cutting-edge recycling technology and enhanced methods for recycling plastic packaging. The introduction of recycled material in the production chain can reduce plastic waste (Da Cruz et al., 2014). As plastic production is increasing yearly since its introduction into everyday life products, there is a vital concern about the environmental challenges of these materials throughout their life cycle. Special attention must be paid to the plastic used in packaging (Da Cruz et al., 2012). In 2018, the world produced more than 100 million tonnes of multilayer plastic packaging; by 2025, this will rise to 140 million tonnes (Walker et al., 2020). Plastic packaging will account for nearly 40 million tonnes of trash, and it is projected that by 2025, this will increase to 50 million tonnes (Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2020). In India, plastic waste generates around 3.5 million tons yearly due to increased packaging material consumption, and it is projected to grow from 5% to 7% annually (Bhattacharya et al., 2018). This results in waste plastic being dumped or burned. Multilayer packaging, including flexible and rigid, accounts for 59% of India's plastics output (OECD, 2019). Only 9% of plastic trash worldwide gets recycled, while 91% is sent to landfills, incinerators, and uncontrolled dumps (Geyer et al., 2017). In India, 13% of plastic waste is recycled, with 4% incinerated, 36% in landfills, and 46% in open dumpsites (CPCB, 2020).

Packaging has emerged as the most prominent plastic consumer, accounting for approximately 42% of total plastic production (Mutha et al., 2006). Plastic is a remarkable material with many uses, but it also causes environmental issues (Thompson et al., 2009). Barrier properties in opposition to oxygen, water vapor, light, CO2, and organoleptic properties allow for an extensive shelf-life, thus the present form of the food industry, and diminished food losses (Bishop & Mount, 2016). This necessity makes packaging necessary for scalability, strength, machinability (rigidity, softening, heat resistance, slip, and pliability), advancement, and useability (Sangroniz et al., 2019). In multilayer packaging, polymeric and non-polymeric materials, functioning as paper and aluminum, are mixed to form the various layers (Anukiruthika et al., 2020; Tartakowski, 2010); it allows for customized functional properties using multi-materials rather than single-layer packaging (John Dixon, 2011). Existing film structures may benefit from multilayers because of their ability to lower costs by, for example, substituting less expensive polymers, decreasing film thickness, or using recycled materials (Butler & Morris, 2016). Another benefit of layer stacking is the ability to do what would be impossible in a single layer alone (Butler & Morris, 2016). According to Dahlbo et al. (2018), multilayer packaging accounts for around 17 % to 20 % of plastic packaging. This packaging is becoming more common in packaging cosmetics, food, prescriptions, medicines, and electronics (Anukiruthika et al., 2020).

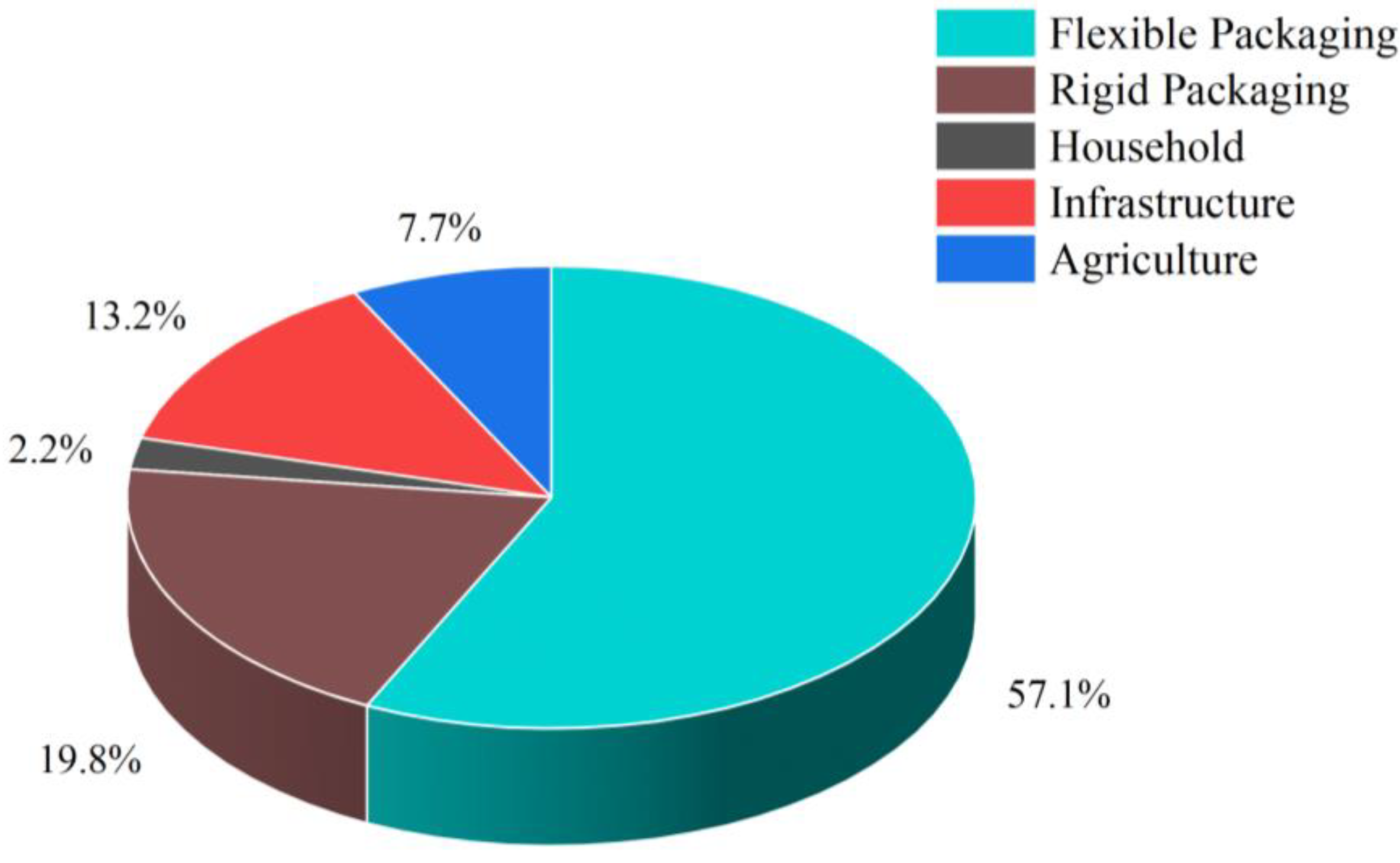

The packaging industry has an increasing market growth, especially flexible packaging, which makes up 52% of India's usage, as shown in

Figure 1, followed by rigid packaging. The food sector leads in using flexible packaging, with 68% in 2019. This shows the rising trends in critical packaging materials from 2019 to 2024 (Porta et al., 2019). Films made of plastic are crucial for the manufacture of multilayer packaging. These films may be made of polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), polycarbonate (PC), or metalized plastic (Wang et al., 2022). The global demands for product safety, quality, and convenience have driven the evolution of the packaging industry (Majidet al., 2018). Multilayer plastic packaging raises a lot of various environmental impacts on the ecosystem (Pauer et al., 2020). Due to the non-biodegradable nature of plastic packaging, virgin plastic must be reduced (Hopewellet al., 2009). Raising the recycling rate of multilayer plastic packaging is one practical answer to this problem; yet, the complexity of this kind of packaging might hinder its recyclability and add to worries about the sustainability of current packaging regulations (Soares et al., 2021). Consequently, efforts are underway to develop more innovative and advanced recycling technologies to resolve the problem (Ragauskas et al., 2021).

This review paper presents the recycling of multilayer plastic packaging, its challenges, opportunities, and future scenarios in upcoming years. It discusses the detailed solutions for increasing the circularity of plastics and the potential advancements that need to be used to recycle multilayer plastic packaging. It also summarizes the current scenario of plastic packaging use, waste generated, and associated environmental impacts on the ecosystem. It then discusses the conventional available recycling technologies for managing mixed plastic waste. The article discusses multilayer packaging: structure, composition, types, standard production methods, and their functional benefits. It then discusses the numerous aspects, policies, and regulations related to developing a growing multilayer plastic packaging recycling sector, including separation, recycling, and collecting plastic packaging.

2. Multilayer Packaging

Multilayer packaging contains polymeric layers and inorganic layers, such as aluminum coatings (Schmidt et al., 2021), makeup multilayer packaging (MLP), which may be flexible or semi-rigid (Dziadowiec et al., 2022). Each of the MLP's levels serves a crucial purpose (Eemeli Hasanen, 2016), and the MLP may have anything from two to twenty-four layers (Langhe & Ponting, 2016). The functions desired, the layers used, and the materials utilized to attain those desires (Pettersen et al., 2020). The innermost layer serves as a sealing layer by directly touching the packaged items or materials (Barry A & Morris, 2016). A polyolefin-type inner layer, for instance, would be an appropriate way to prevent migration and provide an interaction barrier (Butler & Morris, 2016). The specific substances are generally used to conserve the freshness or organoleptic properties to prevent the packaging material's liquid and gaseous exchange permeability (Ibrahim Garba, 2023). The thickness of the film can be increased, or proper barrier layers may help prevent microbiological spoilage, avoid oxidation, gain or loss of moisture, loss of flavor and fragrance, or enhancement of unpleasant outside odors (John Dixon, 2011). To conserve the product quality from light, the light barrier helps, such as inorganic substances like aluminum deposition on a polymer layer or polymer layer filled with TiO2 (Anukiruthika et al., 2020).

Multilayer packaging structure and materials are crucial parameters to define packaging in the modern world, offering sophisticated product packaging solutions to tackle distinct requirements of protection, preservation, and convenience of different products or goods (Mario Scetar, 2021). The multiple layers used in this packaging system to enhance the overall packaging performance and the ability to combine the distinct materials, each having specific functional characteristics to the structure, made the core of multilayer packaging efficiency. The different materials used include polymeric materials, paper, metal films like aluminum, and a coating of specific materials (Sukhareva, & Yakovlev, 2012). Additionally, multilayer packaging is often used for perishable items or foods with a shorter shelf life since it can better maintain the integrity of the product (Agarwal et al., 2023). Multilayer packaging is one of the effective ways to keep a product safe during rigorous storage and handling (Almasi et al., 2020). The general multilayer flexible packaging consists of three distinct layer structures (Schmidt et al., 2022), each material having specific functional properties, as shown in

Table 1 to enhance the performance of the package, as mentioned below.

2.1. Types of Multilayer Packaging and Production Methods

2.1.1. Types of Multilayer Packaging

Flexible multilayer packaging: It is manufactured using thin films of polymeric or other materials like metal or paper by lamination or coextrusion (Niaounakis, 2015). It is widely used in the food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries. Each layer gives specific functional barrier properties to the package (Scetar, 2021). This distinct material is combined to protect from moisture, gases, odors, and light. It is highly versatile and can be made in various forms like pouches, wraps, sachets, and bags (Charles & Eldridge, 2016).

Applications: Food packaging (snacks, confectionery), pharmaceutical packaging, cosmetics (shampoo, hair oil), etc.

- 2.

Semi-rigid multilayer packaging: It is manufactured using a mixture of thin, flexible film and thick, rigid polymeric or other materials like metalized film by lamination or coextrusion (Saha & Ghosh, 2022). Each layer gives the specific function excellent barrier properties against external factors.

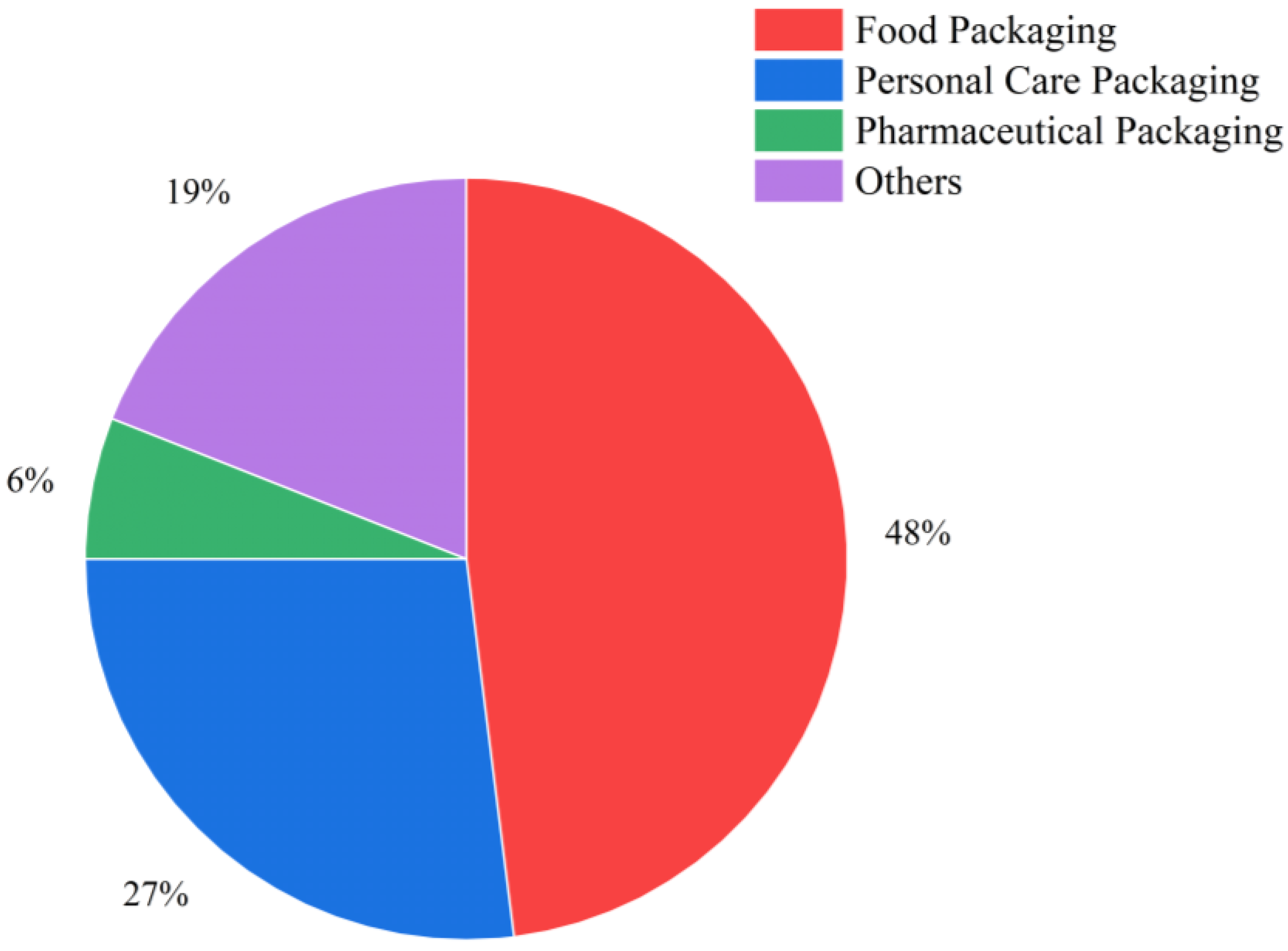

Multilayer packaging combines distinct materials, provides excellent barrier properties, and offers different aging solutions (Gartner et al., 2015). Therefore, the packaging is used in various sectors, as shown in

Figure 2, across the FMCG industries, such as food, pharmaceutical, personal care, and others.

2.1.2. Production Methods

Co-extrusion: The coextrusion method entails melting and fusing two or more polymeric materials previously existing as pallets or grains (Ajitha et al., 2016). The polymeric soften flows are then connected, and the resultant multi-layered extrusion is cooled (Messin et al., 2017). Multilayer films often employ coextrusion processes (Anukiruthika et al., 2020), such as flat die extrusion/cast extrusion, blow extrusion, and sheet extrusion, to name a few examples of these processes

Lamination: In the lamination process, distinct material layers are bound together by adhesive or heat. It may involve the multiple layers pre-produced by extrusion or coating having specific barrier properties. The material includes polymeric films, metallic foil, and paper (Morris, 2016; Wagner, 2016). Many alternative methods may be used to create the lamination, including adhesive lamination, extrusion lamination, hot melt lamination, and wax lamination.

Coating: This technique is very similar to extrusion lamination; however, unlike extrusion lamination, there is no secondary web involved, and the resulting film consists of just two layers (Wang et al., 2022). There are different coating techniques to prepare the multilayer film (Vartiainen et al., 2014). Some are commonly used as aqueous dispersion, solvent-based, vacuum, and hot melt coating.

Barrier properties, mechanical strength, aesthetic appeal, and cost-effectiveness are just a few areas where these techniques may be integrated and adapted to fulfill the needs of multi-material, multilayer packaging (Fabra et al., 2014). The method is selected depending on the desired specific properties in the packaging structure (Anukiruthika et al., 2020).

2.3. Functional Benefits of Multilayer Packaging

The multilayer packaging is a testament to the innovative strides made in packaging technology (Pascall et al., 2022). Multilayer packaging has revolutionized industries such as food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics by leveraging its ability to provide different functional property and their benefits (Marsh & Bugusu, 2007), as shown in

Table 2. Its versatile nature renders it an indispensable tool for ensuring diverse products' longevity, quality, and safety in an ever-evolving market landscape.

This shows that multilayer packaging is an essential part of the packaging of perishable products to make them convenient and safe (Anukiruthika et al., 2020).

3. Challenges in Multilayer Packaging Recycling

3.1. Material Complexity and Compatibility

Multilayer packaging is manufactured by using distinct polymeric or other materials (Tartakowski, 2010). The different materials have particular properties like temperature and decomposition temperatures (Selke et al., 2004). Most of the material used in MLP is an incompatible structure (Massey, 2003), with significant differences in the specific boiling point (Dixon, 2011). This makes it “difficult to recycle” or separate these efficiently (Jönkkäri et al., 2020). For example, a combination of plastic and aluminum film may require specialized technologies for separation and recovery (Kaiser et al., 2018). However, if the materials are compatible (Schmidt et al., 2022), which means having a nearly similar property specific to melting point temperature, i.e., fully miscible, then it is possible to direct regranulation is possible.

3.2. Sorting and Separation Technologies

Insufficient sorting of MLP from plastic waste creates enormous difficulties in recycling them (Lange, 2021). Because the conventional recycling processes cannot manage the multilayer packaging (Garcia et al., 2017), it needs to be separated from the mono-material plastics to recycled it (Cimpan et al., 2015). It requires highly efficient sorting and separation techniques to produce high-quality recycled products (Chen et al., 2021), but these techniques may be energy-intensive, costly, and complex.

3.3. Contamination and Residue Management

The different contaminates from the waste stream and non-polymeric materials can make recycling difficult due to insufficient removal or washing of the waste stream (Horodytska et al., 2018). The primary contaminants are food residue, adhesives, ink, oil or wax, and others present in MLP, which can complicate recycling (Hahladakis & Iacovidou, 2019). These also may impact the quality of the recyclates and recycled products (Tonini et al., 2022). The chemicals, e.g., oligomers, additives, and their sub-products, have subsequently been reported on the recycled plastic granules (Arulrajah et al., 2017). To reduce the contaminants, highly efficient separation technologies are required (Jehanno et al., 2022); it also depends upon many factors, including the recycling process and production.

3.4. Lack of Standardization and Technology

The complexity of the multilayer packaging structure makes it challenging to recycle (Shamsuyeva et al., 2021), and the design of the MLP package plays a significant role in determining the recyclability of packaging (Bauer et al., 2021). Multilayer packaging manufacturers need to consider their end-of-life fate during the design of their products, especially multilayer flexible packaging (Guerritore et al., 2022). Conventional recycling technologies are insufficient to recycle multilayer packaging waste efficiently with high-quality recycling so it can be used in high-grade products (Mulakkal et al., 2021). Some industrial chemical and mechanical recycling technologies include chem-lysis, gasification, and compatibilization (Ragaert et al., 2017). However, these technologies also have many limitations regarding recycling rates, gas emissions, high energy consumption, and high cost.

3.5. Loss of Material Properties

The recycling process for multilayer packaging often results in losing some original material properties (Schyns et al., 2021). This prohibits the potential applications of recycled materials. The recycled materials cannot be used in the same-level products that we have used in low-grade products (Tonini et al., 2022). In the recycling process, if the multi-composite materials were mixed without first separating the layers (Yang et al.,2011), it has been shown that most blends feature inadequate mechanical qualities. When dealing with immiscible mixes, things become more complicated since the interlayers have different characteristics (Roosen et al., 2020). As a result, when it comes to producing heterogeneous polymeric blends, several distinct unit procedures must be carried out to include chemical molecules that exhibit interfacial activity to improve compatibility and render the combinations miscible (Kaiser et al., 2018).

3.6. Economic and Cost Considerations

The complexities of recycling multilayer flexible packaging require several processes (Picuno et al., 2021). Also, it can increase the cost of the recycling operation (Lin et al., 2023). If the price of recycling is at most the value of the recycled materials, it becomes economically challenging to implement effective recycling solutions (Söderholm et al., 2020). The recycled granules also do not have the efficient quality to use in high-grad products to become financially viable to the industries (Anukiruthika et al., 2020).

Addressing the multilayer packaging recycling challenges requires a versatile and multifaced approach, like collaborating with various organizations and research to introduce innovative solutions to all of these challenges and a sustainable solution for multilayer flexible packaging recycling. Moreover, collected household MLP is often found contaminated and has a high moisture content, and they are mixed with organic waste, making the recovery and recycling of MLP a challenge. Fully automated MSW sorting units are required to extract recyclable flexible plastic waste fractions from other materials, including metal, plastic, paper, glass, wood, and biological particles.

4. Conventional Recycling Technologies for Multilayer Packaging

Recycling multilayer packaging from many materials is more complicated than recycling monolayer sheets (Walker et al., 2020). Mechanical and chemical recycling processes, among others, have been investigated in recent years (Maris et al., 2018; Rahimi & Garciá, 2017; Schyns & Shaver, 2021). Since recycling results in complicated mixes, chemicals are often added to improve the blend's cohesiveness by binding the various polymers back (Titone et al., 2022). The summary of the current recycling of multilayer packaging is shown in

Figure 3. It describes the multilayer packaging mainly recycled in two ways (Kaiser et al., 2018). The first is to recycle the multilayer packaging by separating the distinct layers individually and then recycling that layer. The second is to recycle the multilayer packaging together with different multi-material layers. The process includes a series of phases, including adding compatibilizing chemicals (Lahtela et al.,2020). Waste from industry may be recycled by compatibilization since its composition is excellent (Cabrera et al., 2022).

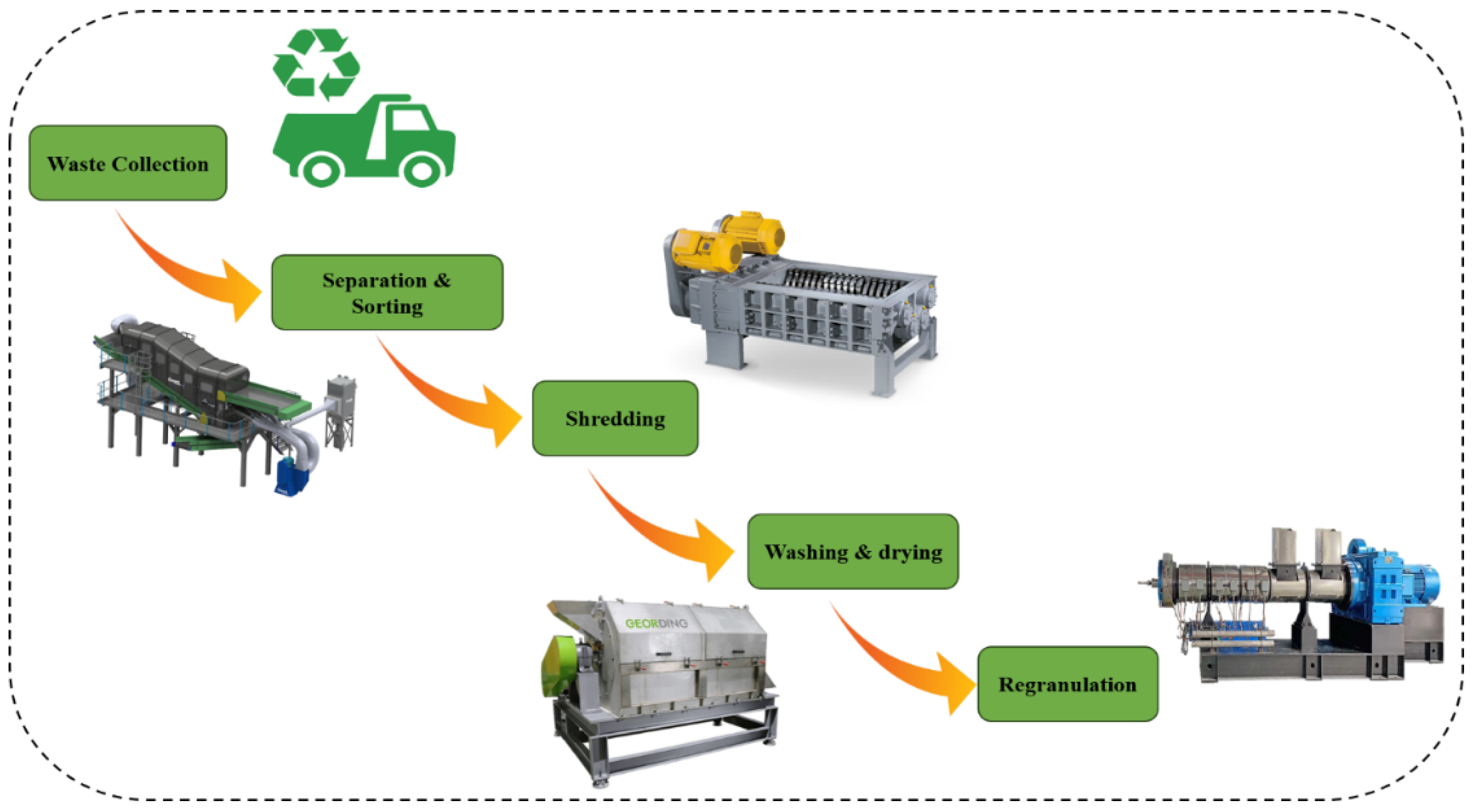

4.1. Mechanical Recycling

The ultimate prevalent process of recycling used for numerous plastic wastes (Post-industrial and post-consumer) is mechanical recycling (Martín et al., 2022), in which the polymer structure is maintained by various mechanical processes such as shredding, cleaning, extrusion, etc. The multi-material contaminates in recyclates produced by mechanical recycling procedures are only suitable for low-grade product materials (Akhras et al., 2022). On the other hand, granules made from recycled materials may serve as an inferior raw material with poor mechanical qualities in the manufacturing of high-value items (Muñoz Meneses et al., 2022). Products from single plastic-type and multi-material trash are often input waste and are typically polluted vaguely by oil wax, food residues, and inks (Kibria et al., 2023). Plastic is cleaned, shredded, melted, and re-granulated as part of the recycling technique, consisting of plastic waste transformation through several physical processes (Serranti et al., 2019). Before re-granulation, decontamination may be accomplished using several methods (Horodytska et al., 2018). The

Figure 4 illustrates the various steps involved in mechanical recycling.

Separation and sorting: Based on shape, density, color, or chemical composition.

Baling: For ease of handling, storage, and transport, the plastic waste is fed into a baler and compressed into bales.

Washing and drying: Elimination of various contaminants.

Shredding: Size reduction of the product flakes.

Regranulation/Palletization: Reprocessing of the flakes into pallets or granulates.

Depending on the requirement or plastic type, the previous mechanical steps like washing, shredding, separation, and extrusion may applied in between the various processes (Serranti et al., 2019). Whenever used for less demanding applications (Muñoz Meneses et al., 2022), such as garbage bags, furniture, buckets, etc., sorting is required because the post-consumer waste stream is more polluted with other residues, such as additives, inks, and incompatible polymers (Hopewell et al., 2009). These residues significantly hinder the recycling and reprocessing procedure (Davidson et al., 2021).

4.2. Chemical Recycling

Recycled polymers, monomers, and hydrocarbon feedstocks, such as high-quality polymers, may be made from the plastic trash that is the raw material in this process (Chanda et al., 2021). Different procedures have developed to varying degrees and may all be considered chemical recycling (Nordahl et al., 2023). Plastic trash has excellent potential as a source for the manufacture of energy sources and chemicals (Evode et al., 2021). The goal is to make high-quality recyclates, monomers, and petrochemical feedstock (Ragaert et al., 2017). Gasification or partial oxidation, hydrogen technologies, pyrolysis, depolymerization, and fluid catalytic cracking are some of the most frequently used processes in chemical recycling (Kaminsky et al., 2021; Davidson et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2022; Kirillet al., 2023). All the processes are ideal for recycling plastic waste and protecting the environment by reducing non-biodegradable waste (Biessey et al., 2023). The most common pyrolysis technique is used for polyolefins (Alejandra et al., 2022), but the products obtained from them are gases and liquids, requiring a high recycling cost (Abdy et al., 2022). However, due to the increased separation expense, recycled materials are instead burned as fuel (Dijkgraaf et al., 2020). The benefits and drawbacks of the most widely used chemical recycling methods that have prompted the development of more advanced alternatives are described in

Table 3 (Cabrera et al., 2022).

It is crucial to remember that most chemical and plastic waste recycling techniques are still in their infancy, are not commercialized, and are pretty expensive (De Sousa et al., 2021). According to the Facts 2020 Report, chemical recycling processes are already used in Germany (0.2%) and Italy (0.1%) for a small portion of plastic recycling (Plastics Europe, 2020). Despite all this, they offer a great deal of future for valorizing dirty and diversified plastic waste, in which case the sorting and split-up may be more technically and economically viable. Therefore, major polymer manufacturers are predicted to spend €7.2 billion by 2030, as Plastic Europe indicates.

5. Opportunities for Advancing Multilayer Packaging Recycling

5.1. Design for Recyclability

Improving the recyclability of multilayer packaging films usually involves improving the package recycling efficiency, which presents a problem (Seier et al., 2023). Various solutions introduced to the market have been refined to promote efficiency and security for goods (Hagelüken et al., 2022). Thicker films are anticipated to be necessary to lessen the complexity of these multilayer packaging films (Recoup, 2021). This goes against the goals and circular economy, and it needs to reduce the environmental impacts and consumption. Multilayer flexible packaging by weight is 10% of the total package (Tartakowski et al., 2010). Although the percentage may not appear significant, at least 40% of food items are packaged flexibly (Marsh & Bugusu, 2007). This demonstrates the importance of implementing the suggested changes and reviews. Their similarity facilitates the incorporation of package manufacturers' recommendations for assessment and redesign across the board (Bauer et al., 2021).

5.1.1. Mono-Material and Compatible Structure

Several established techniques are for lowering material variability to primarily polyolefin material, such as tolerances for ethylene–vinyl alcohol (EVOH), metalized aluminum layers, and coatings (Packaging SA, 2017). A theoretical basis for printed redesign choices is that polyolefins show the most excellent degrees of compatibility with other polyolefins (Bauer et al., 2021). Additionally, it is viable to mix diverse post-consumer polyolefin classes in precise amounts; nevertheless, this produces recycled material granules of subpar quality (Sara et al., 2016). Recyclability is improved using a mono-material approach, which is what polyolefins should do to roughly 90% (Carullo et al., 2023). Traditional mechanical recycling techniques do not accept mixtures of polyolefins with other polymer types or multi-materials like PET or PA (Meneses et al., 2022). With the current recycling infrastructure in Asia (Ng et al., 2023), the difficulty in sorting multilayer packaging (Hopewell et al., 2009), and the incompatibility of most polymeric materials with traditional mechanical recycling methods (Maris et al., 2017), these measures to find a recycling solution appear significant.

The following material combinations have been identified as potentially improving barrier characteristics during multilayer substitution.

- 1)

Mono-polyolefins with EVOH

- 2)

Mon-polyolefins with AlOx or SiOx

- 3)

Mono-polyolefins metalized

From a recycling perspective, unpigmented/transparent mono-polyolefin material is the best flexible packaging choice.

Table 4 shows the compatible pair of polymeric materials to make sustainable multilayer flexible packaging.

5.1.2. Minimization of Barrier Layer

Product sustainability is further tied to the trade-offs introduced by design for recycling about the replacement of certain material qualities, barrier requirements, and affiliated shelf-life (Briassoulis et al., 2017). The layers of metallization or EVOH layer are reduced to prevent quality harm in secondary material qualities due to the push to produce new and unique recyclable material for barriers, primarily against oxygen and light (Wu et al., 2021). However, any changes made to multilayer flexible packaging must not compromise product security or shorten its shelf life due to variables such as moisture or air (Marangoni et al., 2019). For instance, several types of candy are susceptible to air and water, which causes them to get stale and lose their crunchiness (R. et al., 2010).

Table 5.

The following combinations of various polymeric materials to know about adhesion between them. Adapted from (Butler & Morris, 2016).

Table 5.

The following combinations of various polymeric materials to know about adhesion between them. Adapted from (Butler & Morris, 2016).

| Polymer |

HDPE |

PP |

PS |

PA |

EVOH |

PVDC |

| LDPE |

Good |

------ |

------ |

------ |

------ |

------ |

| LLDPE |

Good |

Good |

------ |

------ |

------ |

------ |

| EVA |

Good |

Good |

Good |

------ |

------ |

Good |

| PE-g-Mah |

Good |

------ |

------ |

Good |

Good |

------ |

So, extensive study is required to create recyclable barriers to replace EVOH and other polymers like PA and PVDC (Pauer et al., 2020). As in the case of semi-rigid PP packaging, the percentage of EVOH is limited, making it a recyclable packaging solution (Soares et al., 2021). The range of available options for oxygen and gas barrier properties is limited with AlOx and SiOx (Parhi et al., 2020). These coatings are generally suitable for aseptic packaging, which is necessary in the food sector for preservation, protection, and product convenience (Butler & Morris, 2016).

5.2. Enhanced Sorting and Separation Techniques

The various advanced separation and sorting approaches are discussed for efficiently recycling complex materials, particularly multilayer plastic packaging (Butler & Morris, 2016; Gundupalli et al., 2017). To reduce the adverse environmental effects of plastic waste, these cutting-edge methods may recycle more multilayer plastic packaging faster than traditional methods (Kaiser et al., 2018). The following are the primary techniques: (a) sensor-based and optical sorting and (b) artificial intelligence and machine learning, used for efficient sorting separation of the multilayer plastic packaging waste from the plastic waste to enhance recycling (Jean et al., 2021).

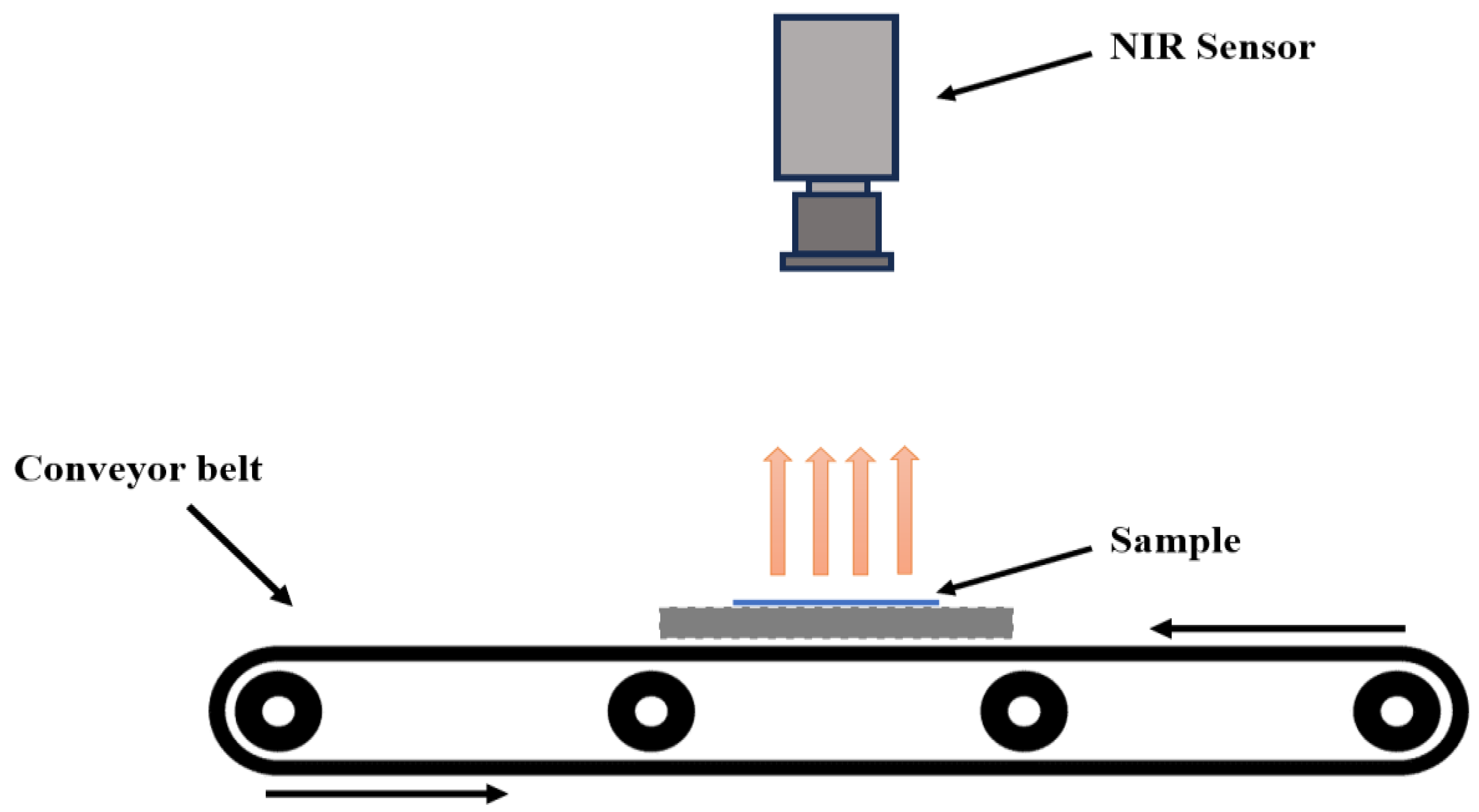

5.2.1. Sensor-Based and Optical Sorting

Sensor-based and optical sorting stains will be vital advancements in complex multilayer packaging recycling in the coming years (Soares et al., 2021). Sensor-based sorting of multilayer polymers using near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is a cutting-edge technology because of its outstanding efficiency in sorting and throughput (Koinig et al., 2021). NIR spectroscopy provides several avenues for obtaining an object's spectral features, providing details about the material's composition and condition (Chen et al., 2021). Polymers and other NIR-active materials may be classified according to their distinctive spectra (Bassey et al., 2021). Also, the ranges of plastic polymers are influenced by surface qualities such as roughness and moisture conditions (Küppers et al., 2019). Films in MLP are analyzed by comparing their spectra to determine which polymers are present after being separated from the recycling facility's three-dimensional debris (Koinig et al., 2021). Researchers looked at the ranges of several multilayer samples to see if they could find a way to quantitatively and qualitatively determine MLP composition (Chen et al., 2020). Different patterns and shapes of consumer plastic packaging trash were then replicated in the sensor unit (Gadaleta et al., 2023), along with various material contaminations identified and classified as MLP (Chen et al., 2021).

Figure 5.

NIR sensor and optical illumination setup. Adapted from (Chen et al., 2021).

Figure 5.

NIR sensor and optical illumination setup. Adapted from (Chen et al., 2021).

5.2.2. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

The algorithms designed by machine learning is performed given assignment based upon the previous data and past-set practice examples like learning module (Janiesch et al., 2021). It is efficient to read its self-responses based on the driving principles of machine learning through a direct connection (Kroell et al., 2021). To get the authorized possible results of various situations, it needs to study the actual case studies during the training of machine code, for example, usually with output and input variables. The pattern or work can get the dynamic output extensions for the machine learning algorithm designed (Sarker et al., 2021). Machine learning stores the visual characteristics of plastic packaging waste, like material type, color, size, and surface properties, to remove the vast amount of plastic waste (Janusz et al., 2021). The packaging data can obtain waste collection information, such as defining the type of material and the form where the material is gained (Ncube et al., 2021). It operates by feeding a sufficient number of various examples to generate functional outputs like a learning model driven by an algorithm (Wen et al., 2022). A machine learning algorithm also gives sorting output of different distinct objects accurately, durably, and speedily from the bulk of plastic waste (Koinig et al., 2024). It can also detect the composition or construction of plastic packaging materials by using robots with artificial intelligence (Fang et al., 2023). Multilayer packaging recycling is one of the most challenging processes (Walker et al., 2020). However, using robots can be done quickly and fully automated with high accuracy for multi-material types of plastic packaging waste. Automation (Kroell et al., 2021). Machine learning and intelligence are principal areas of innovative technology that support the processes of material recovery facility (MRF)

5.2.3. Embedded Labeling in Packaging

Embedded labeling is one of the innovative techniques to improve the traceability of multilayer plastic packaging from other plastic waste by using flexible electronic radio-frequency identification (RFID) (Majid et al., 2018; Aliaga et al., 2011; Salgado et al., 2021). To facilitate the efficient sorting and separation of multilayer plastic trash, the business of pragmatic superconductors is now creating ultra-thin and flexible RFID chips that can be embedded into various substrates, including plastic and paper layers (Packaging Europe, 2020). In the labeling, a flexible electronic chip is embedded directly into the layers of plastic packaging during manufacturing directly onto the plastic packaging materials (Nagarajan Palavesam et al., 2018). This is completed using different processing methods, including distinct printing types or during material extrusion (Marten et al., 2012). It is increasingly popular for multilayer packaging because it makes sorting easier during recycling. Because the MLP is made from different material layers, each having specific functional properties. This makes it challenging to sort plastic packaging efficiently during recycling, mainly in automated sorting techniques (Nemat et al., 2023). The embedded label can make it easier by enabling the tracing of the MLP waste from others by reading the unique code of electronic chips. The sorting machine reads these codes to sort the multilayer packaging.

There are some additional benefits of embedded labeling as below:

These are more durable than traditional labels.

These can be made to prevent form tampering, counterfeiting

5.3. Advanced recycling technologies

Since the recycling industry cannot sift, identify, and separate the different layers with present recycling methods (Soares et al., 2021), MLP recycling is a complicated process in general (Horodytska et al., 2018). As a result, MLP is often burnt for energy recovery rather than reused, as recycling is not seen as a high priority in the circular economy (Kaiser et al., 2018). As a solution to recycle the MLP, there are two main advanced methods (Soares et al., 2021). The first is to detach the different material layers for further processing of material separately (Kaiser et al., 2018), while the other option is to process all of the distinct material layers together (G. Schyns et al., 2020). These cutting-edge procedures include successive stages and techniques for recycling MLP, which are competent for the eventual deterioration and recycling of complex structures (Taghavi et al., 2021).

5.3.1. Selective Dissolution

Table 6.

The following is the list of solvents for specific materials to dissolve the material for multilayer packaging recycling.

Table 6.

The following is the list of solvents for specific materials to dissolve the material for multilayer packaging recycling.

| Sr. No. |

Thermoplastic Polymers |

Solvents |

Reference |

| 1. |

PE |

Biodiesel, 2-MTHF, Cyclopentyl methyl ether

|

(Samorì et al., 2023) |

| 2. |

PP |

Diphenyl ether, N, N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl) tallowamine, α-pinene and D-limonene |

(Ramírez-Martínez et al., 2022) |

| 3. |

PS |

Benzene, Toluene, and Ethyl benzene

|

(Umoren et al., 2021) |

| 4. |

EVOH |

Isopropanol or ethanol and DMSO/water mixture |

(Sánchez-Rivera et al., 2023) |

| 5. |

PET |

DMSO, N-methyl pyrrolidinone, GVL |

(Walker et al., 2020) |

It is the solvent-based method in which a specific solvent dissolves the distinct polymeric layer in the multilayer plastic packaging (Cecon et al., 2022). The particular solvent targeted the polymeric component removed from the multilayer structure and dissolved into the solvent stepwise (Anja Mieth, 2016). Dissolving polymeric materials for recycling is essential since most polymeric materials come in multilayer plastic packaging made from a particular thermoplastic like PE, PP, PS, PET, or PVC (Hadi et al., 2012). The success of this procedure is based on the essential selection of solvents (Byrne et al., 2016); there are many commercially available solvents, but only a few will dissolve the appropriate material layers in question (Walker et al., 2020). Additionally, it must not alter the other material layers in the packaging; they must continue to exist in the solid phase (Zhao et al., 2018).

To facilitate subsequent recovery, a solvent with a low contamination rate may dissolve a multilayer structure's unique substance (Kaiser et al., 2018). In Europe, the Fraunhofer Institute and APK AG Company are working on several new recycling methods for multilayer polyolefin packaging using selective dissolving techniques (Vollmer et al., 2020). A solvent-based approach was shown to be effective for recycling single-use multilayer packaging. In addition to being a practical, cutting-edge method of MLP recycling (Walker et al., 2020), it also yields superior recycled products compared to virgin materials (Martin et al., 2020).

5.3.2. Delamination

A multi-material multilayer contains adhesive for bonding interlayers; consequently, the recycling process may include delamination steps (Berkane et al., 2023; Horodytska et al., 2018). Zhang et al. (2015) investigated a substrate's delamination from bonding damage in post-consumer liquid packaging. The selected solvent Favaro et al. (2013) utilized to delaminate plastic packaging made of a PE/Aluminum/PET combination was acetone. Due to the bond's strength, physical procedures are often used to separate multilayers (Bamps et al., 2023); shredding and washing may separate essential structures (Perick et al., 2016). Even though delamination techniques and patents to separate layers were gathered by Kaiser et al. 2018 and Anukiruthika et al. 2020, no industrial-scale commercial treatment was identified (Walker et al., 2020). In order to delaminate multilayer plastic packaging (MLP) in a low-energy fashion, the German company Saperatec GmbH is developing cutting-edge technology (Saperatec, n.d.). The procedure asks for a microemulsion containing a surfactant that encourages layer separation after the shredding stage (Vagnoni et al., 2023). By reducing the interlayer stresses between the materials, Saperatec claims that the method may cause structures built of PE/Aluminum, PP/Aluminum, and PE/PET to delaminate (Ügdüler et al., 2021). Since it does not entirely dissolve the developing polymers, it would represent a new kind of separation, as Vollmer et al. (2020) stated. The Australian company ‘PVC Separation’ developed a similar technique of multilayer plastic packaging by a similar method to delaminate multilayers by swelling the polymer layer with low-boiling point solvent first, followed by inserting it in hot water, which causes the solvent to release the necessary polymers (Vollmer et al., 2020).

5.3.3. Compatibilization

Most multilayer packaging is made from various resins, some of which are mechanically unstable (Xie & Sui, 2019). Because of the usability of the polymeric blends, some chemicals are used to increase the mechanical stability of multilayers of packaging, called the compatibilizer (Ghosh et al., 2021), and then further, all the materials are recycled together in a solitary stream without segregation (Mostafapoor et al., 2019). This method improves the structure of the immiscible polymer blends by adding another chemical component (Ragaert et al., 2017). The compatibilizer chemical is selected based on the polymer blend and generally consists of a blocky structure (Ajji, 2003); it depends upon the specific packaging materials (Ragaert et al., 2017). The Dow Company applied this innovatory compatibilization process for multilayer packaging waste by incorporating compatibilizer chemicals (Dow, 2016). "self-recyclable" refers to packaging that may be recycled without additional chemicals, such as those used in separate recycling routes (Dow, 2021). Recently, (Cabrera et al., 2022) assumed that the mechanical recycling of multilayer packaging could perform a new approach as an alternative way to improve recycling methods through eco-design. The work described that future recycling is oriented toward polyethylene-based multilayer packaging films (Kaiser et al., 2018). This approach aims to improve the output from mechanical recycling of multilayer packaging into recycled granules of high quality for subsequent product production.

5.3.4. Feedstock Recycling

In this process, the products are obtained as hydrocarbon feedstock like monomers by treating difficult-to-recycle plastic packaging waste, and it is also an emerging alternative technology (Garforth et al., 2004). It involves several processes: pyrolysis, gasification, hydrocracking, and fluid-catalytic cracking (Ragaert et al., 2017). In depolymerizing complex plastic waste, such as multilayer plastic packaging, the influential technology is pyrolysis (Thiounn & Smith, 2020). Two different forms of petroleum feedstock, naphtha or diesel, are created when the polymer molecules disintegrate into monomers in the absenteeism of oxygen and elevated temperatures (Ragaert et al., 2017). This process is most famous for selectively obtained products such as liquids, gases, or waste, and mechanical recycling is a new development through selective catalytic thermolysis included in chemical recycling (Garcia & Robertson, 2017). Due to its high energy cost, it is not a widespread multilayer plastic recycling practice (Garcia & Robertson, 2017).

However, as technology advances, it may become a viable option for plastics or garbage containing elements that are challenging to recycle from an economical and systematic standpoint materially, hence opening up new avenues and possibilities (Plastics Europe, 2020). Solis and Silveira (2020) evaluated eight mechanisms for their technological readiness level and raw material for diverse plastic waste recycling. Pyrolysis, catalytic cracking, and traditional gasification were the most advanced processes, while other emerging technologies need much more funding to reach a commercial level (Solis & Silveira, 2020). The technology is being developed by companies including Unilever, Borealis, BASF, Recycling Technologies, Sabic, Plastics Energy & Neste, and others, who are betting on its success as a long-term answer for plastic recycling (Vollmer et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it is uncertain how these practices may become cost-effective and environmentally advantageous (Ügdüler et al., 2020).

6. Environmental Policy and Regulatory Framework

India is one of the world's largest producers of plastic waste (Aryan et al., 2019). To address this issue, the Indian government has implemented various policies and regulations to manage plastic waste (PWM Rule, 2021), and one of the essential requirements for plastic waste management in India is the Extended producer responsibility (EPR) framework (Hossain et al., 2021). Multilayer plastic packaging is widely used in various industries due to its lightweight, low cost, and excellent barrier properties, especially in food and beverage packaging (Perera et al., 2022). However, the recycling of multilayer plastic packaging poses significant challenges due to the complexity of its composition, which often includes multiple types of plastics and other materials. This policy and regulatory framework aim to address these challenges and promote the recycling of multilayer plastic packaging.

Regulatory Measures

- 1.

Mandatory Recycling Targets: Industries that produce or use multilayer plastic packaging should meet mandatory recycling targets. These targets should be progressively increased to encourage continuous improvement.

- 2.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Producers of multilayer plastic packaging should be responsible for managing the waste generated from their products. This includes financing and organizing the collection, sorting, and recycling of their products.

- 3.

Green Public Procurement: Public institutions should prioritize procuring products packaged in recyclable multilayer plastic packaging or alternative environmentally friendly materials.

- 4.

Research and Development Incentives: Provide tax incentives and grants for companies and research institutions that develop new technologies or improve existing technologies for recycling multilayer plastic packaging.

-

5.

Implementation and Monitoring

- 6.

Regulatory Authority: Establish a regulatory authority to oversee the implementation of this policy and regulatory framework. The authority will also monitor compliance and enforce penalties for non-compliance.

- 7.

Reporting Requirements: Industries should regularly report on their progress towards meeting the recycling targets. Independent third parties should audit the reports.

- 8.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Conduct public awareness campaigns to educate consumers about the importance of recycling multilayer plastic packaging and how to dispose of it properly.

This policy and regulatory framework provide a comprehensive approach to promoting the recycling of multilayer plastic packaging. It addresses the environmental challenges of multilayer plastic packaging waste and encourages innovation and sustainable practices in the industry (Meherishi et al., 2019). We can make significant strides towards a more sustainable and circular economy by implementing this framework.

7. Future Scenarios

7.1. Principal Drivers

The multilayer plastic packaging future will be significantly influenced by the ability of recycled granules material in high-grade packaging (food contact packaging), the ecological quality of the recycling process, availability of sorting and collection, recycling capacity, traceability of recycled material, costs of recycled material, worth of recycling process, increase of mono-materials, and practice of other biodegradable and compostable materials.

With a focus on two key elements, the vitality of multi-material packaging recycling and multi-layer plastic packaging is thoroughly investigated.

The first off was brought on by fresh legislation designed to reduce single-use plastic packaging and reform recycling rates. For instance, the EU Plastics Strategy prohibits landfills and incineration as alternative disposal methods for plastic packaging by 2030. Instead, it requires that all plastic packaging be reused or recycled cost-effectively. Single-use plastics will no longer be permitted in Australia as of March 2021 (EPA South Australia). In the following years, legislation limiting packaging waste is projected to be introduced in the United Kingdom, several states in the United States, and other countries, including India (Roland Berger, 2020). This second main factor was motivated by the need for innovative recycling techniques.

7.2. Scenarios Matrix

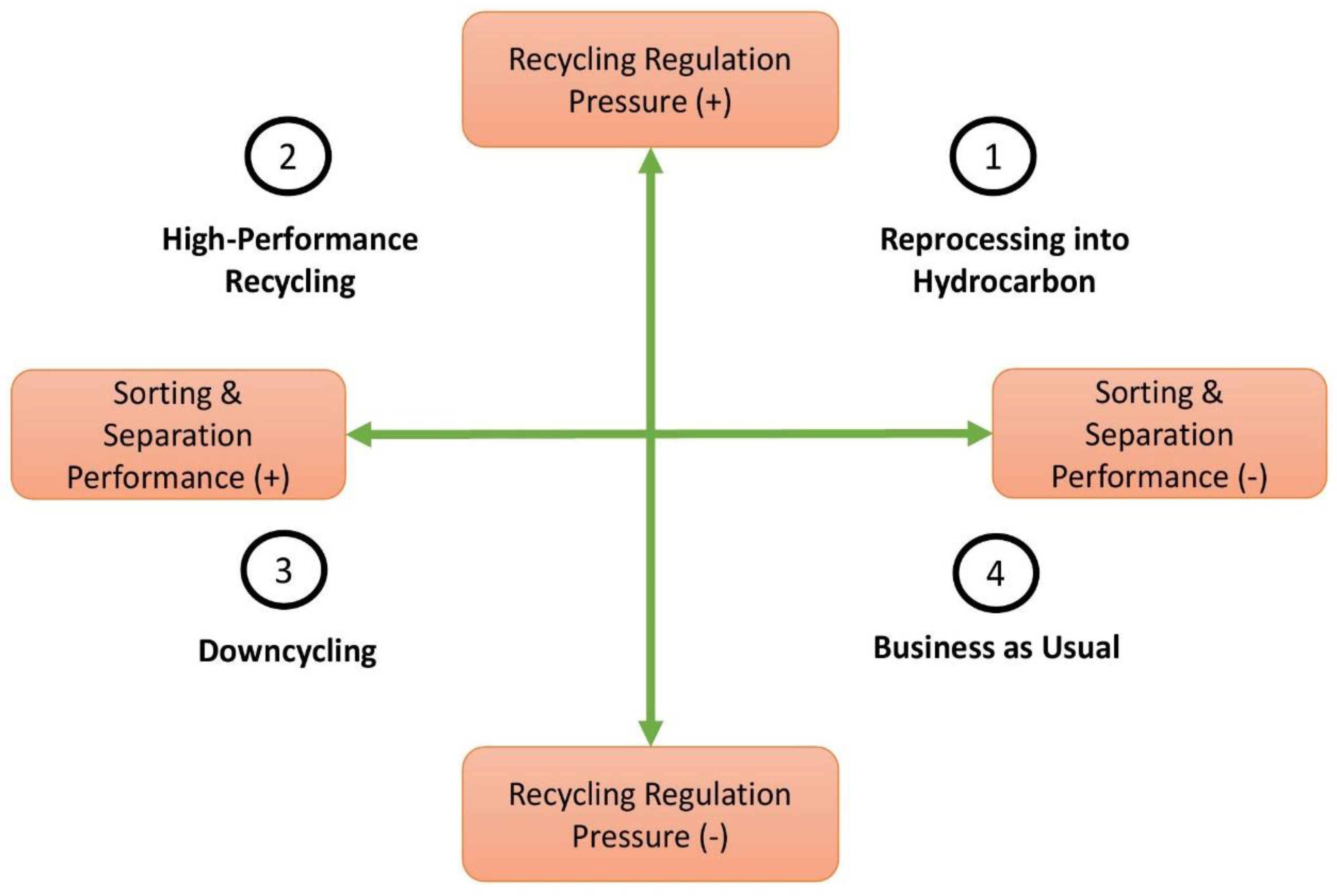

Potential future scenarios for multi-layer packaging (MLP) recycling are shown as primary assumptions in the scenario matrix (

Figure 6). According to the methodology defined, each scenario is described in detail (Soares et al., 2022).

Scenario 1: Recycling into hydrocarbons (feedstock)

Legislators will be compelled to authorize unconventional recycling procedures, such as chemical recycling towards hydrocarbons, due to a strict recycling modulation and an inadequacy of immense-performance sorting technology (+/-).

-

(A)

Assumptions: Once the ultimate goods can be used to create plastic and support the circular economy, the feedstock recycling streams may be labeled as recycling under the relevant directives and laws.

-

(B)

Data: The feedstock recycling streams will be allowed to be labeled as recycling once the end products can be utilized to make plastic and support the circular economy.

-

(C)

Slow/stop: excess energy utilization, skepticism about environmental advantages, expensive initial investment, and untraceable recyclates.

-

(D)

-

Qualitative effects:

Positive: minimizing immense-accuracy sorting logistics and the related costs; addressing possible charges connected with not recycling plastics (such as the EU plastic tax). The manufactured feedstock has several potential applications, such as stopping plastic waste from leaking into the environment and enabling new treatment methods.

Negative: Reprocessing hydrocarbons into materials requires more energy if the feedstock is used to create plastic. There will also be expenditures for implementation, increased logistics, and secondary materials.

-

(E)

Timespan: < 5 years.

Scenario 2: High-performance recycling

A trend in MLP waste management toward immense-performance recycling, in which recycled material has a grade comparable to virgin material, is driven by strict recycling legislation and high-performance sorting technology (+/+).

- (A)

Assumptions: Plastic packaging comprising many materials and layers will be easily identifiable and separated by modern sorting technology. Laws will favor high-efficiency recycling processes.

- (B)

Data: Solvent-based high-performance material recycling techniques need precise sorting to produce the best polymers.

- (C)

Slow/stop: Less money would be spent on sorting and treatment technologies if the market's mono-material packaging trash decreased. Closed-loop recycling for these uses is impossible due to technological limitations, financial barriers, an underdeveloped market for recycled materials, stringent food-contact regulations, and shifting priorities (such as the COVID-19 epidemic and skepticism over the feasibility of sustainability initiatives in certain countries).

-

(D)

-

Qualitative effects:

Positive: Minimize future expenses connected with plastic recycling (plastic tax on not-recyclable plastics); reduce the environmental consequences of alternative disposal techniques like landfills and incinerators. Increase the quantity of recovered material on the market and reduce its price.

Negative: Due to the high initial cost of the technology, the high cost of recovered materials, and the need for improvements to recycling systems (such as improved sorting logistics), it will likely be some time before the technology is widely accepted and financially feasible.

-

(E)

Timespan: 5–10 years.

Scenario 3: Low-performance recycling (Downcycling)

A mechanical recycling route with passive requirements and poor end products is likely if even a tiny amount of sorting is feasible and the legislation does not mandate industry participation in high-quality recycling (+/-).

-

(A)

Assumptions: Large funding for new immense-performance material recycling technologies will not be manufactured since there is no strict government control or support for the recycling process.

-

(B)

Data: Mixed recycling is practiced by specific flexible packaging post-consumer separation systems, leading to inferior end goods (such as those used for playgrounds, roads, etc.).

-

(C)

Slow/stop: There is an increasing demand for new solutions from consumers, an increasing momentum behind creating a circular economy with numerous recycling cycles, and the falling cost of alternative recycling methods.

-

(D)

-

Qualitative effects:

Positive: Taking into account factors like the high cost of raw materials, the low cost of recycling immense-performance materials, the established methodology in few regions, and the feasibility in small-income nations, addressing the costs correlated with not recycling plastic packaging (like plastic tax); developing new material products; lowering the amount of material needed to produce goods; and so on.

Negative: Do not allow the repeated recycling of substances, as this does not support a strong and continuing circular economy.

-

(E)

Timespan: < 5 years.

Scenario 4: Business-As-Usual (BAU)

The multi-material, multilayer packaging garbage management will persist the same, i.e., landfill, energy recovery, etc., due to the insufficiency of defined regulations around plastic waste recycling and the lack of separation and sorting logistics.

-

(F)

Assumptions: Shortly, low-income nations' plastic waste streams will significantly decrease. However, global packaging industry players may continue to take advantage of less regulated states as "business as usual."

-

(G)

Data: Many developing countries still lack adequate legislation for the disposal of plastic packaging trash. High-performance sorting technologies are still far off, yet many countries still have to cope with environmental leakage and dumping.

-

(H)

Slow/stop: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) without national boundaries, global cooperation toward the circular economy, innovation, and recycling technologies that are more affordable and suitable for less developed systems.

-

(I)

Qualitative effects:

Positive: Stay away from switching to an untested technology that comes with extra implementation costs.

Negative: Environmental impact of disposal (namely greenhouse gas emissions, resource-draining, soil contamination, etc.), leakage of plastic garbage into the environment, future costs of not-recycled plastic (like plastic tax), and so on.

Timespan: < 10 years.

8. Conclusions

Due to the complexity of package value chains, which need thorough analysis, the MLP, collection, separation, and sorting is essential for recycling. Consequently, bringing about change in such a diverse set of systems is challenging. Multilayer plastic packaging on a global scale meets the many uses and requirements for packaging. It also became a concern for the recycling sector due to the difficulty of layer separation and, consequently, high treatment costs. Because of this, this packaging is often discarded in mixed plastic streams and then either landfilled or burned with energy recovery. Over half of the experts surveyed for this report anticipate that cutting-edge technologies will be developed predominantly in high-income nations during the next five to ten years to recycle multilayer plastic packaging trash. This comprises advanced sorting technologies and high-performance material recycling, particularly in Europe and Asia. Additionally, chemical recycling possibilities (feedstock) have potential futures. As a result, this kind of method is anticipated to expand as a reliable recycling outflow in the coming years. In addition, downcycling is regarded as a component of the solution for reducing environmental plastic leakage. Therefore, various MLP recycling solutions, including all possible outcomes, even the least preferred one, business as usual, are in store for the future. This packing material will be handled according to the area's resources, laws, and priorities. Additionally, it was determined that improved recyclability would result from increased integration and transparency throughout the whole chain of packaging value. Establishing a more harmonious system calls for coordinated efforts from stakeholders, including brand owners, consumers, governments, the packaging industry, research institutes, and waste management players. Achieving a transparent circular economy in this sector is more difficult because of variables, including the variety of local waste management systems, the vast range in MLP material composition, and the various regulatory frameworks.

Ultimately, a sizable percentage of the globe still lacks access to essential waste management and traditional recycling infrastructures. The increasing utilization of bio-based substances in MLP and all other types of plastic packaging may provide short-term possibilities to cut carbon release and decouple substances from the fossil-derived economy. As a result, using renewable resources in packaging materials may improve sustainability performance, mainly when multi-material or multilayer plastic packaging is necessary.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by Bhushan P. Meshram. Original manuscript was written by Bhushan P. Meshram. Material preparation, data collection, analysis and illustrations were performed by Bhushan P. Meshram, Amit Love, and Omdeo Gohatre. All authors commented and reviewed the first draft of manuscript. The study was supervised by Amit Love. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Author Bhushan P. Meshram acknowledges Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee and MHRD for providing financial assistantship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Author Bhushan P. Meshram would like to thank the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (IIT Roorkee), and Ministry of Education (MoE), Government of India, for providing financial support to carry out this research work during his M.Tech.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anja Mieth, E. H. C. S. (2016). Guidance for the identification of polymers in multilayer-LBNA27816ENN.

- Anukiruthika, T., Sethupathy, P., Wilson, A., Kashampur, K., Moses, J. A., & Anandharamakrishnan, C. (2020). Multilayer packaging: Advances in preparation techniques and emerging food applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(3), 1156–1186. [CrossRef]

- Alias, A., Wan, M. K., & Sarbon, N. (2022). Emerging materials and technologies of multi-layer film for food packaging application: A review. Food Control, 136, 108875. [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, A.R., Aswathi, M.K., Maria, H.J., Izdebska, J., Thomas, S. (2016). Multilayer Polymer Films. In: Kim, J., Thomas, S., Saha, P. (eds) Multicomponent Polymeric Materials. Springer Series in Materials Science, vol 223. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A., Yaghoubi, E., Wong, Y. C., & Horpibulsuk, S. (2017). Recycled plastic granules and demolition wastes as construction materials: Resilient moduli and strength characteristics. Construction and Building Materials, 147, 639-647. [CrossRef]

- Akhras, M. H., Freudenthaler, P. J., Straka, K., & Fischer, J. (2022). From Bottle Caps to Frisbee—A Case Study on Mechanical Recycling of Plastic Waste towards a Circular Economy. Polymers, 15(12), 2685. [CrossRef]

- Alejandra Arroyave, Shilin Cui, Jaqueline C. Lopez, Andrew L. Kocen, Anne M. LaPointe, Massimiliano Delferro, and Geoffrey W. Coates, Catalytic Chemical Recycling of Post-Consumer Polyethylene, Journal of the American Chemical Society 2022 144 (51), 23280-23285. [CrossRef]

- Abdy, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Yang, Y., Artamendi, I., & Allen, B. (2022). Pyrolysis of polyolefin plastic waste and potential applications in asphalt road construction: A technical review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 180, 106213. [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, C., Ferreira, B., Hortal, M., Pancorbo, M. Á., López, J. M., & Navas, F. J. (2011). Influence of RFID tags on recyclability of plastic packaging. Waste Management, 31(6), 1133-1138. [CrossRef]

- Ajji, A. (2003). Interphase and Compatibilization by Addition of a Compatibilizer. In: Utracki, L.A. (eds) Polymer Blends Handbook. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A. S., Tacker, M., Uysal-Unalan, I., Cruz, R. M. S., Varzakas, T., & Krauter, V. (2021). Recyclability and redesign challenges in multilayer flexible food packaging—a review. Em Foods (Vol. 10, Número 11). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Berkane, I., Cabanes, A., Horodytska, O., Aracil, I., & Fullana, A. (2023). The delamination of metalized multilayer flexible packaging using a microperforation technique. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 189. [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D., Tserotas, P., & Hiskakis, M. (2017). Mechanical and degradation behaviour of multilayer barrier films. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 143, 214–230. [CrossRef]

- Butler, T. I., & Morris, B. A. (2016). PE-Based Multilayer Film Structures. Em Multilayer Flexible Packaging: Second Edition (p. 281–310). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Baughan, J.S. Future trends in global food packaging regulation. In Global Legislation for Food Contact Materials; Baughan, J.S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 65–74. ISBN 978-1-78242-014-9.

- Biessey, P., Vogel, J., Seitz, M., & Quicker, P. (2023). Plastic Waste Utilization via Chemical Recycling: Approaches, Limitations, and the Challenges Ahead. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 95(8), 1199-1214. [CrossRef]

- Bassey U. Rojek LHartmann M. Creutzburg R. Volland A, the potential of NIR spectroscopy in the separation of plastics for pyrolysis, IS and T International Symposium on Electronic Imaging Science and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, F. P., Jin, S., Paggiola, G., Petchey, T. H., Clark, J. H., Farmer, T. J., Hunt, A. J., Robert McElroy, C., & Sherwood, J. (2016). Tools and techniques for solvent selection: Green solvent selection guides. Sustainable Chemical Processes, 4(1), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Bamps, B., Buntinx, M., & Peeters, R. (2023). Seal materials in flexible plastic food packaging: A review. Packaging Technology and Science, 36(7), 507-532. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, G., Li, J., Maazouz, A., & Lamnawar, K. (2022). A Journey from Processing to Recycling of Multilayer Waste Films: A Review of Main Challenges and Prospects. Polymers, 14(12). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Kroell, N., Wickel, J., & Feil, A. (2021). Determining the composition of post-consumer flexible multilayer plastic packaging with near-infrared spectroscopy. Waste Management, 123, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- CPCB. (2020). CPCB_Annual Report on PWM 2019-20. PIB.

- Cimpan, C., Maul, A., Jansen, M., Pretz, T., & Wenzel, H. (2015). Central sorting and recovery of MSW recyclable materials: A review of technological state-of-the-art, cases, practice and implications for materials recycling. Journal of Environmental Management, 156, 181-199. [CrossRef]

- Cecon, V. S., Curtzwiler, G. W., & Vorst, K. L. (2022). A Study on Recycled Polymers Recovered from Multilayer Plastic Packaging Films by Solvent-Targeted Recovery and Precipitation (STRAP). Macromolecular Materials and Engineering, 307(11), 2200346. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M. (2021). Chemical aspects of polymer recycling. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 4(3), 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Carullo, D., Casson, A., Rovera, C., Ghaani, M., Bellesia, T., Guidetti, R., & Farris, S. (2023). Testing a coated PE-based mono-material for food packaging applications: An in-depth performance comparison with conventional multi-layer configurations. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 39, 101143. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J. Packaging Materials: 9. Multilayer Packaging for Food and Beverages; ILSI Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; ISBN 9789078637264.

- Davidson, M.G.; Furlong, R.A.; McManus, M.C. Developments in the life cycle assessment of chemical recycling of plastic waste–A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126163–126175.

- Dijkgraaf, E., Gradus, R. Post-collection Separation of Plastic Waste: Better for the Environment and Lower Collection Costs? Environ Resource Econ 77, 127–142 (2020). [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, F. D. B. (2021). The role of plastic concerning the sustainable development goals: The literature point of view. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 3, 100020. [CrossRef]

- Evode, N., Qamar, S. A., Bilal, M., Barceló, D., & Iqbal, H. M. (2021). Plastic waste and its management strategies for environmental sustainability. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 4, 100142. [CrossRef]

- Fang, B., Yu, J., Chen, Z. et al. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: a review. Environ Chem Lett 21, 1959–1989 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J. M., & Robertson, M. L. (2017). The future of plastics recycling. Em Science (Vol. 358, Número 6365, p. 870–872). American Association for the Advancement of Science. [CrossRef]

- Gundupalli, S. P., Hait, S., & Thakur, A. (2017). A review on automated sorting of source-separated municipal solid waste for recycling. Em Waste Management (Vol. 60, p. 56–74). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gartner, H., Li, Y., & Almenar, E. (2015). Improved wettability and adhesion of polylactic acid/chitosan coating for bio-based multilayer film development. Applied Surface Science, 332, 488-493. [CrossRef]

- Guerritore, M., Olivieri, F., Castaldo, R., Avolio, R., Cocca, M., Errico, M. E., Galdi, M. R., Carfagna, C., & Gentile, G. (2022). Recyclable-by-design mono-material flexible packaging with high barrier properties realized through graphene hybrid coatings. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 179, 106126. [CrossRef]

- G. Schyns, Z. O., & Shaver, M. P. (2021). Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromolecular Rapid Communications, 42(3), 2000415. [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, G., De Gisi, S., Todaro, F., Binetti, S., & Notarnicola, M. (2023). Assessing the Sorting Efficiency of Plastic Packaging Waste in an Italian Material Recovery Facility: Current and Upgraded Configuration. Recycling, 8(1), 25. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. (2021). Performance modifying techniques for recycled thermoplastics. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 175, 105887. [CrossRef]

- Garforth, A. A., Ali, S., Hernández-Martínez, J., & Akah, A. (2004). Feedstock recycling of polymer wastes. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science, 8(6), 419-425. [CrossRef]

- Horodytska, O., Valdés, F. J., & Fullana, A. (2018). Plastic flexible films waste management – A state of art review. Waste Management, 77, 413–425. [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J. N., & Iacovidou, E. (2019). An overview of the challenges and trade-offs in closing the loop of post-consumer plastic waste (PCPW): Focus on recycling. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 380, 120887. [CrossRef]

- Hagelüken, C., Goldmann, D. Recycling and circular economy—towards a closed loop for metals in emerging clean technologies. Miner Econ 35, 539–562 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jönkkäri, I., Poliakova, V., Mylläri, V., Anderson, R., Andersson, M., & Vuorinen, J. (2020). Compounding and characterization of recycled multilayer plastic films. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 137(37). [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C., Alty, J. W., Roosen, M., De Meester, S., Dove, A. P., Chen, E. Y., Leibfarth, F. A., & Sardon, H. (2022). Critical advances and future opportunities in upcycling commodity polymers. Nature, 603(7903), 803-814. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Paul Lange, Managing Plastic Waste─Sorting, Recycling, Disposal, and Product Redesign, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (47), 15722-15738. [CrossRef]

- Janusz Bobulski, Mariusz Kubanek, "Deep Learning for Plastic Waste Classification System," Applied Computational Intelligence and Soft Computing, vol. 2021, Article ID 6626948, 7 pages, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C., Zschech, P. & Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron Markets 31, 685–695 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K., Schmid, M., & Schlummer, M. (2018). Recycling of polymer-based multilayer packaging: A review. Em Recycling (Vol. 3, Número 1). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Kroell, N., Chen, X., Maghmoumi, A., Koenig, M., Feil, A., & Greiff, K. (2021). Sensor-based particle mass prediction of lightweight packaging waste using machine learning algorithms. Waste Management, 136, 253–265. [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M. G., Masuk, N. I., Safayet, R., Nguyen, H. Q., & Mourshed, M. (2023). Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. International Journal of Environmental Research, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W. (2021). Chemical recycling of plastics by fluidized bed pyrolysis. Fuel Communications, 8, 100023. [CrossRef]

- Kirill. Faust, P. Denifl, M. Hapke, Recent Advances in Catalytic Chemical Recycling of Polyolefins, ChemCatChem 2023. [CrossRef]

- Koinig, G., Kuhn, N., Barretta, C., Friedrich, K., & Vollprecht, D. (2021). Evaluation of Improvements in the Separation of Monolayer and Multilayer Films via Measurements in Transflection and Application of Machine Learning Approaches. Polymers, 14(19), 3926. [CrossRef]

- Koinig, G., Kuhn, N., Fink, T., Grath, E., & Tischberger-Aldrian, A. (2024). Inline classification of polymer films using Machine learning methods. Waste Management, 174, 290-299. [CrossRef]

- Mostafapoor, F., Khosravi, A., Fereidoon, A., Khalili, R., Jafari, S. H., Vahabi, H., Formela, K., & Saeb, M. R. (2019). Interface analysis of compatibilized polymer blends. Em Compatibilization of Polymer Blends: Micro and Nano Scale Phase Morphologies, Interphase Characterization, and Properties (p. 349–371). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Meneses Quelal, W.O., Velázquez-Martí, B. & Ferrer Gisbert, A. Separation of virgin plastic polymers and post-consumer mixed plastic waste by sinking-flotation technique. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29, 1364–1374 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Maris, J., Bourdon, S., Brossard, J., Cauret, L., Fontaine, L., & Montembault, V. (2017). Mechanical recycling: Compatibilization of mixed thermoplastic wastes. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 147, 245-266. [CrossRef]

- Majid, I., Ahmad Nayik, G., Mohammad Dar, S., & Nanda, V. (2018). Novel food packaging technologies: Innovations and future prospective. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 17(4), 454-462. [CrossRef]

- Ng, C. H., Mistoh, M. A., Teo, S. H., Galassi, A., Ibrahim, A., Sipaut, C. S., Foo, J., Seay, J., Hin, Y., & Janaun, J. (2023). Plastic waste and microplastic issues in Southeast Asia. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1142071. [CrossRef]

- Lange Jean-Paul, Managing Plastic Waste─Sorting, Recycling, Disposal, and Product Redesign ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (47), 15722-15738. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Severson, M. H., Nguyen, R. T., Johnson, A., King, C., Coddington, B., Hu, H., & Madden, B. (2023). Economic and environmental feasibility of recycling flexible plastic packaging from single stream collection. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 192, 106908. [CrossRef]

- Lahtela, V., Silwal, S., & Kärki, T. (2020). Re-Processing of Multilayer Plastic Materials as a Part of the Recycling Process: The Features of Processed Multilayer Materials. Polymers, 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food packaging–roles, materials, and environmental issues. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R39–R55.

- Messin, T., Follain, N., Guinault, A., Miquelard-Garnier, G., Sollogoub, C., Delpouve, N., Gaucher, V., & Marais, S. (2017). Confinement effect in PC/MXD6 multilayer films: Impact of the microlayered structure on water and gas barrier properties. Journal of Membrane Science, 525, 135-145. [CrossRef]

- Massey Permeability Properties of Plastics and Elastomers A Guide to Packaging and Barrier Materials, Plastics Design Library (2nd Ed), Elsevier Science (2003).

- Mulakkal, M. C., Castillo Castillo, A., Taylor, A. C., Blackman, B. R., Balint, D. S., Pimenta, S., & Charalambides, M. N. (2021). Advancing mechanical recycling of multilayer plastics through finite element modelling and environmental policy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 166, 105371. [CrossRef]

- Martijn Roosen, Nicolas Mys, Marvin Kusenberg, Pieter Billen, Ann Dumoulin, Jo Dewulf, Kevin M. Van Geem, Kim Ragaert, and Steven De Meester, Detailed Analysis of the Composition of Selected Plastic Packaging Waste Products and Its Implications for Mechanical and Thermochemical Recycling, Environmental Science & Technology 2020 54 (20), 13282-13293. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Lara, M., Moreno, J., Garcia-Garcia, G., Arjandas, S., & Calero, M. (2022). Life cycle assessment of mechanical recycling of post-consumer polyethylene flexible films based on a real case in Spain. Journal of Cleaner Production, 365, 132625. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Meneses, R. A., Cabrera-Papamija, G., Machuca-Martínez, F., Rodríguez, L. A., Diosa, J. E., & Mosquera-Vargas, E. (2022). Plastic recycling and their use as raw material for the synthesis of carbonaceous materials. Heliyon, 8(3), e09028. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K., & Bugusu, B. (2007). Food Packaging—Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. Journal of Food Science, 72(3), R39-R55. [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L., Cristianini, M., Padula, M., & Anjos, C. A. R. (2019). Effect of high-pressure processing on characteristics of flexible packaging for foods and beverages. Food Research International, 119, 920-930. [CrossRef]

- Maarten Cauwe, B. Vandecasteele, J. De Baets, J. van den Brand, R. Kusters and A. Sridhar, "A chip embedding solution based on low-cost plastic materials as enabling technology for smart labels," 2012 4th Electronic System-Integration Technology Conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2012, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Meherishi, L., Narayana, S. A., & Ranjani, K. (2019). Sustainable packaging for supply chain management in the circular economy: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117582. [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, M. (2015). Manufacture of Films/Laminates. Em Biopolymers: Processing and Products (p. 361–386). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, S. L., Baral, N. R., Helms, B. A., & Scown, C. D. (2023). Complementary roles for mechanical and solvent-based recycling in low-carbon, circular polypropylene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(46). [CrossRef]

- Ncube, L. K., Ude, A. U., Ogunmuyiwa, E. N., Zulkifli, R., & Beas, I. N. (2021). An Overview of Plastic Waste Generation and Management in Food Packaging Industries. Recycling, 6(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan Palavesam, Sonia Marin, Dieter Hemmetzberger, Christof Landesberger, Karlheinz Bock and Christoph Kutter, Roll-to-roll processing of film substrates for hybrid integrated flexible electronics, Flex. Print. Electron. 3 014002. [CrossRef]

- Nemat, B., Razzaghi, M., Bolton, K., & Rousta, K. (2023). Design-Based Approach to Support Sorting Behavior of Food Packaging. Clean Technologies, 5(1), 297-328. [CrossRef]

- Pascall, M. A., DeAngelo, K., Richards, J., & Arensberg, M. B. (2021). Role and Importance of Functional Food Packaging in Specialized Products for Vulnerable Populations: Implications for Innovation and Policy Development for Sustainability. Foods, 11(19), 3043. [CrossRef]

- Picuno, C., Alassali, A., Chong, Z. K., & Kuchta, K. (2021). Flows of post-consumer plastic packaging in Germany: An MFA-aided case study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 169, 105515. [CrossRef]

- Pauer, E., Tacker, M., Gabriel, V., & Krauter, V. (2020). Sustainability of flexible multilayer packaging: Environmental impacts and recyclability of packaging for bacon in block. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 1, 100001. [CrossRef]

- Parhi, A., Tang, J., & Sablani, S. S. (2020). Functionality of ultra-high barrier metal oxide-coated polymer films for in-package, thermally sterilized food products. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 25, 100514. [CrossRef]

- Perera, K. Y., Jaiswal, A. K., & Jaiswal, S. (2022). Biopolymer-Based Sustainable Food Packaging Materials: Challenges, Solutions, and Applications. Foods, 12(12), 2422. [CrossRef]

- Plastic Waste Management (Amendment) Rules, 2021.Link: https://environment.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/inline-files/pwm_epr_1.pdf.

- Ragaert, K., Delva, L., & Van Geem, K. (2017). Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Management, 69, 24–58. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Martínez, M., Aristizábal, S. L., Szekely, G., & Nunes, S. P. (2022). Bio-based solvents for polyolefin dissolution and membrane fabrication: from plastic waste to value-added materials. Green Chemistry, 25(3), 966–977. [CrossRef]

- RECOUP. (2021). The essential guide for all those involved in the development and design of plastic packaging Plastic Packaging Recyclability by Design 2021. www.recoup.org.

- R. Ergun, R. Lietha & R. W. Hartel (2010) Moisture and Shelf Life in Sugar Confections, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 50:2, 162-192. [CrossRef]

- Samorì, C., Pitacco, W., Vagnoni, M., Catelli, E., Colloricchio, T., Gualandi, C., Mantovani, L., Mezzi, A., Sciutto, G., & Galletti, P. (2023). Recycling of multilayer packaging waste with sustainable solvents. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 190. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rivera, K. L., Munguía-López, A. del C., Zhou, P., Cecon, V. S., Yu, J., Nelson, K., Miller, D., Grey, S., Xu, Z., Bar-Ziv, E., Vorst, K. L., Curtzwiler, G. W., Van Lehn, R. C., Zavala, V. M., & Huber, G. W. (2023). Recycling of a post-industrial printed multilayer plastic film containing polyurethane inks by solvent-targeted recovery and precipitation. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 197. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J., Grau, L., Auer, M., Maletz, R., & Woidasky, J. (2022). Multilayer Packaging in a Circular Economy. Polymers, 14(9). [CrossRef]

- Seier, M., Archodoulaki, M., Koch, T., Duscher, B., & Gahleitner, M. (2023). Prospects for Recyclable Multilayer Packaging: A Case Study. Polymers, 15(13). [CrossRef]

- Ščetar, M. Multilayer Packaging Materials. 131-14 . [CrossRef]

- Soares, C. T. D. M., Ek, M., Östmark, E., Gällstedt, M., & Karlsson, S. (2021). Recycling of multi-material multilayer plastic packaging: Current trends and future scenarios. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 176, 105905. [CrossRef]