Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

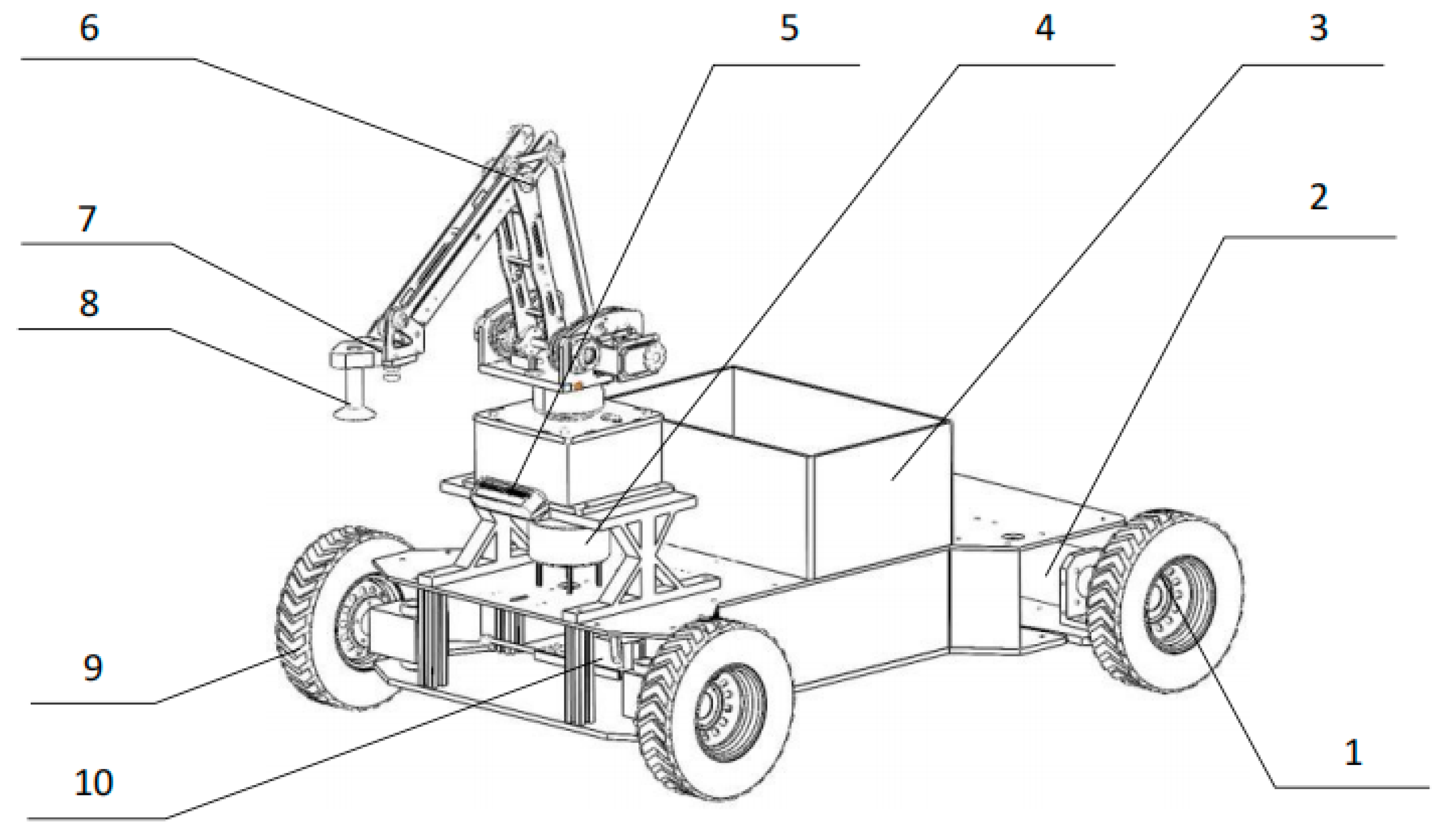

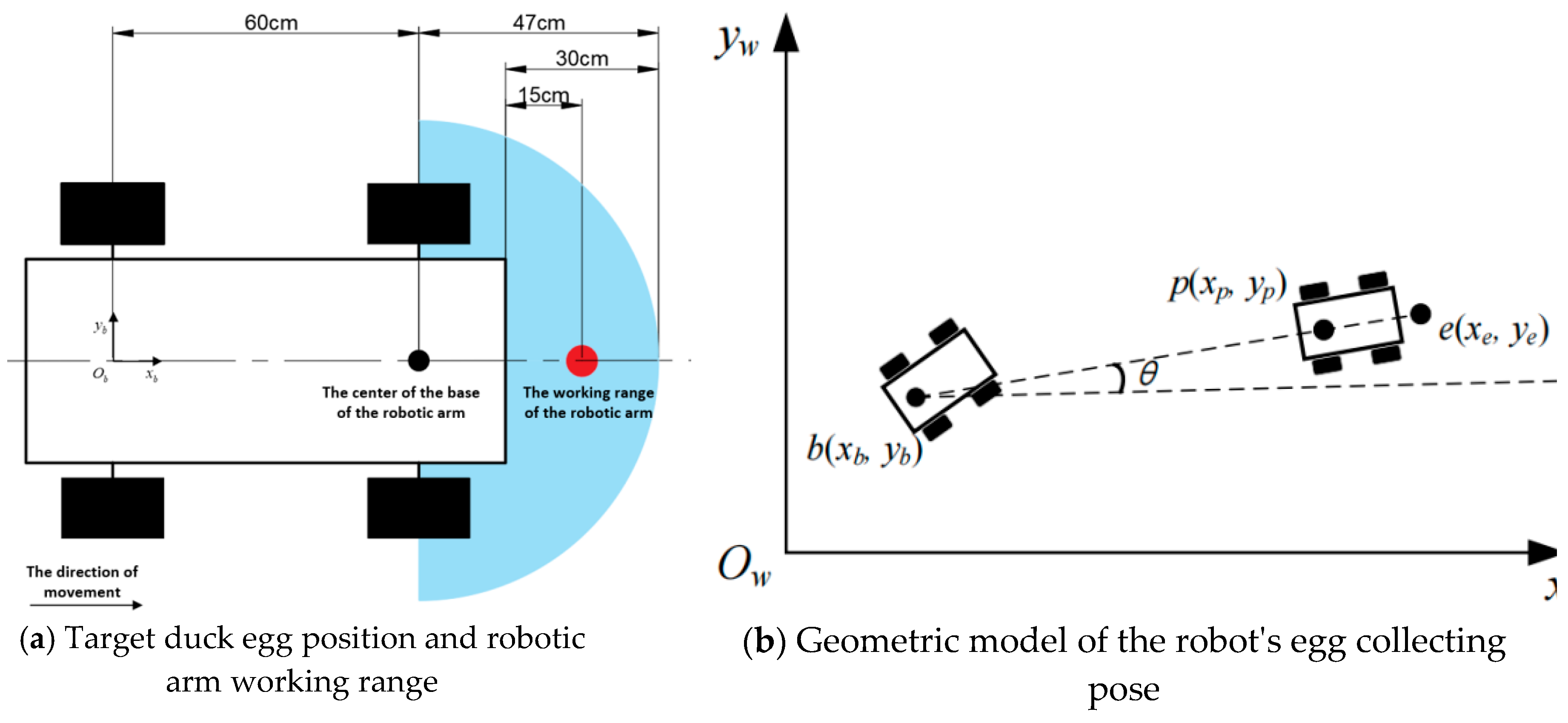

2.1. Design of Egg-Collecting Device

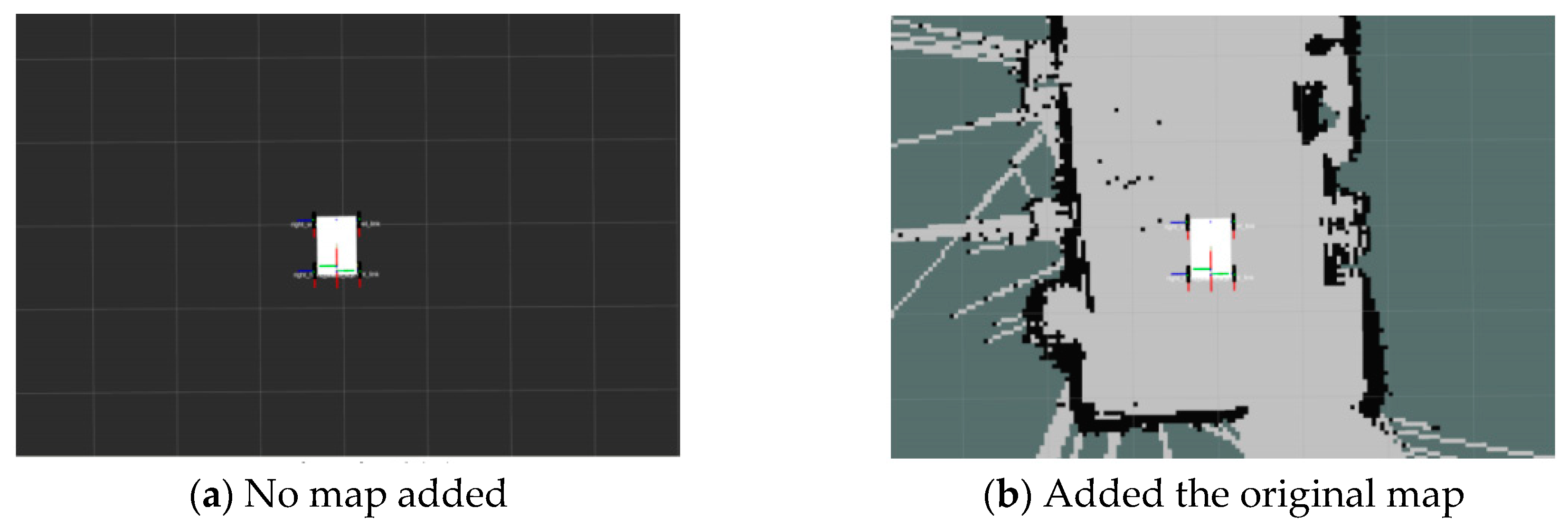

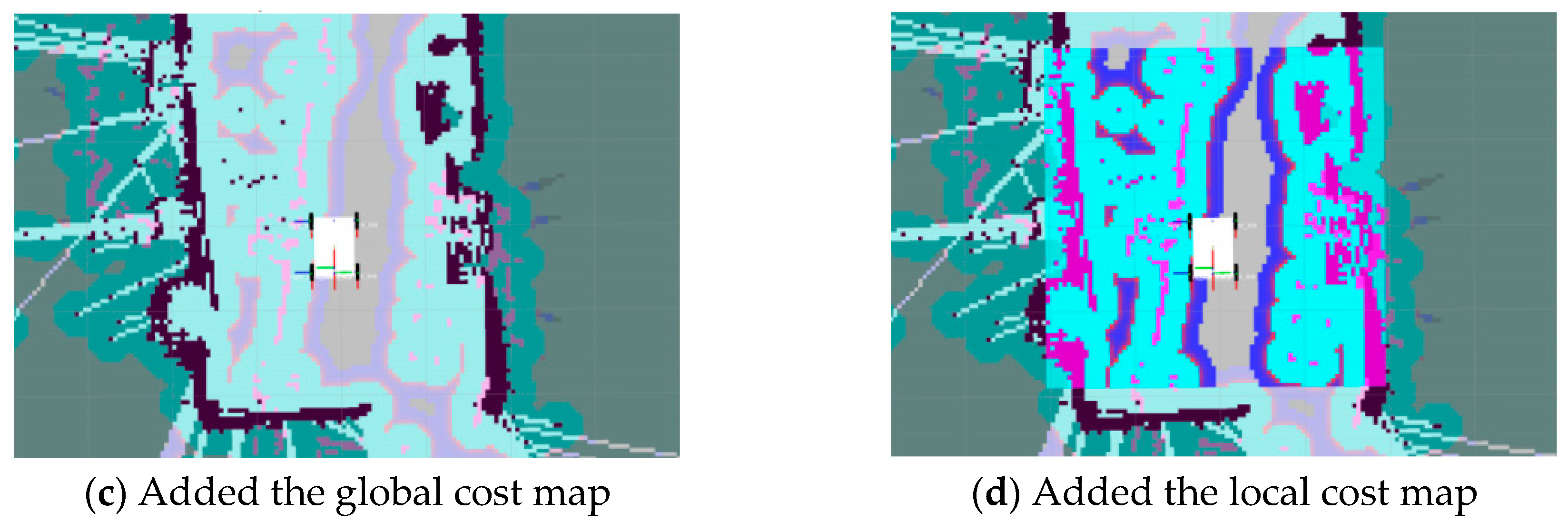

2.2. Map Modeling and Robot Positioning

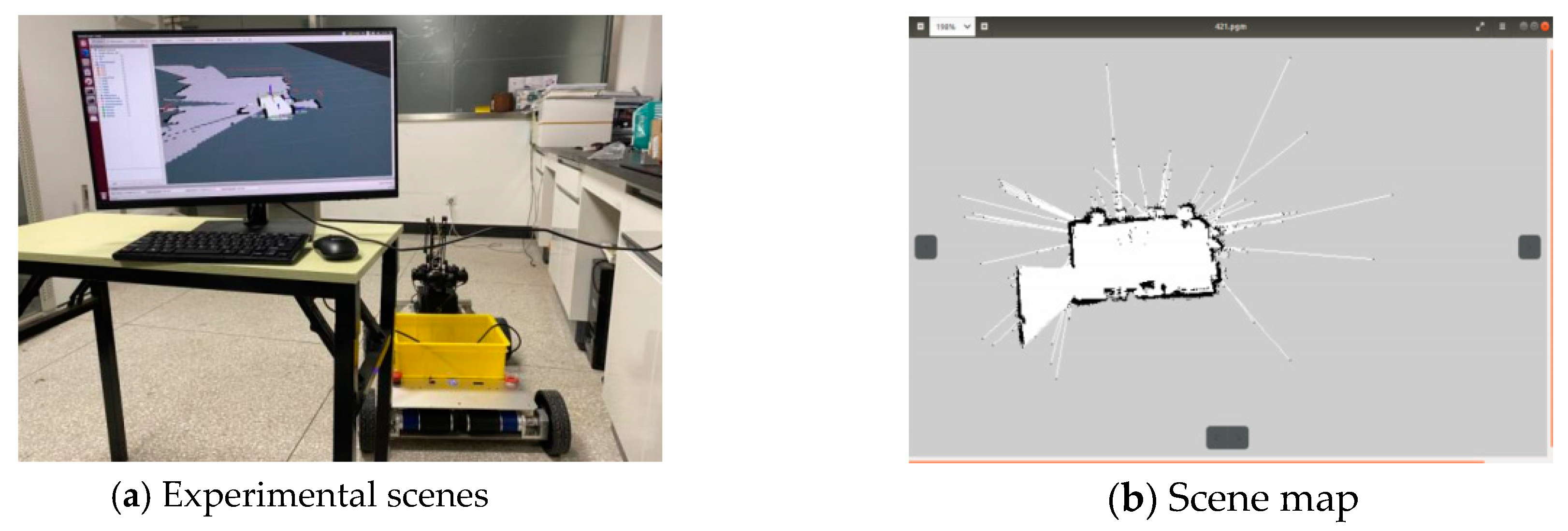

2.2.1. SLAM Map Modeling

2.2.2. AMCL Positioning Method

2.3. Egg Collecting Path Planning

2.3.1. Establishment of Egg Collecting Sequence

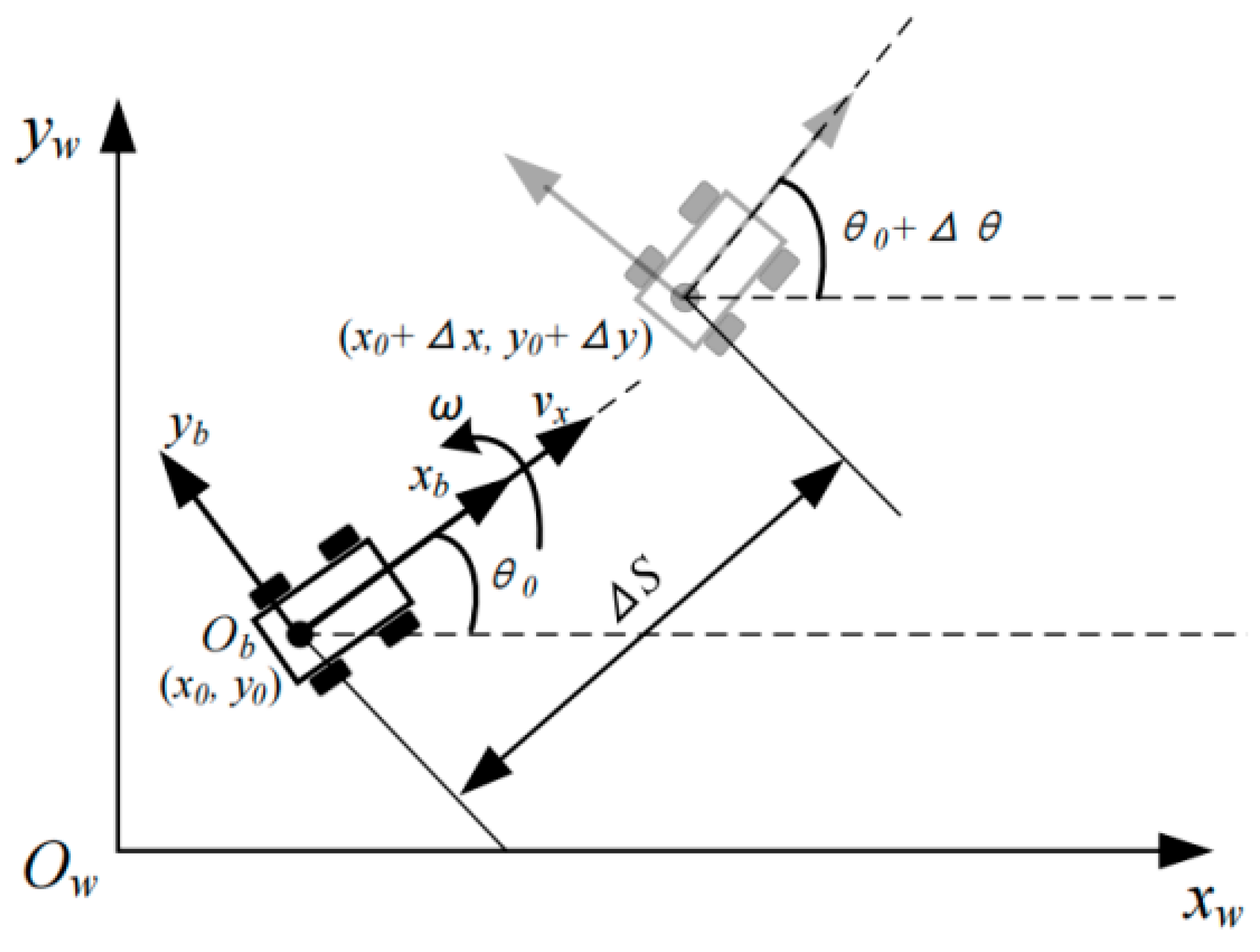

2.3.2. Egg Collecting Navigation Target Point Calculation and Global Path Planning

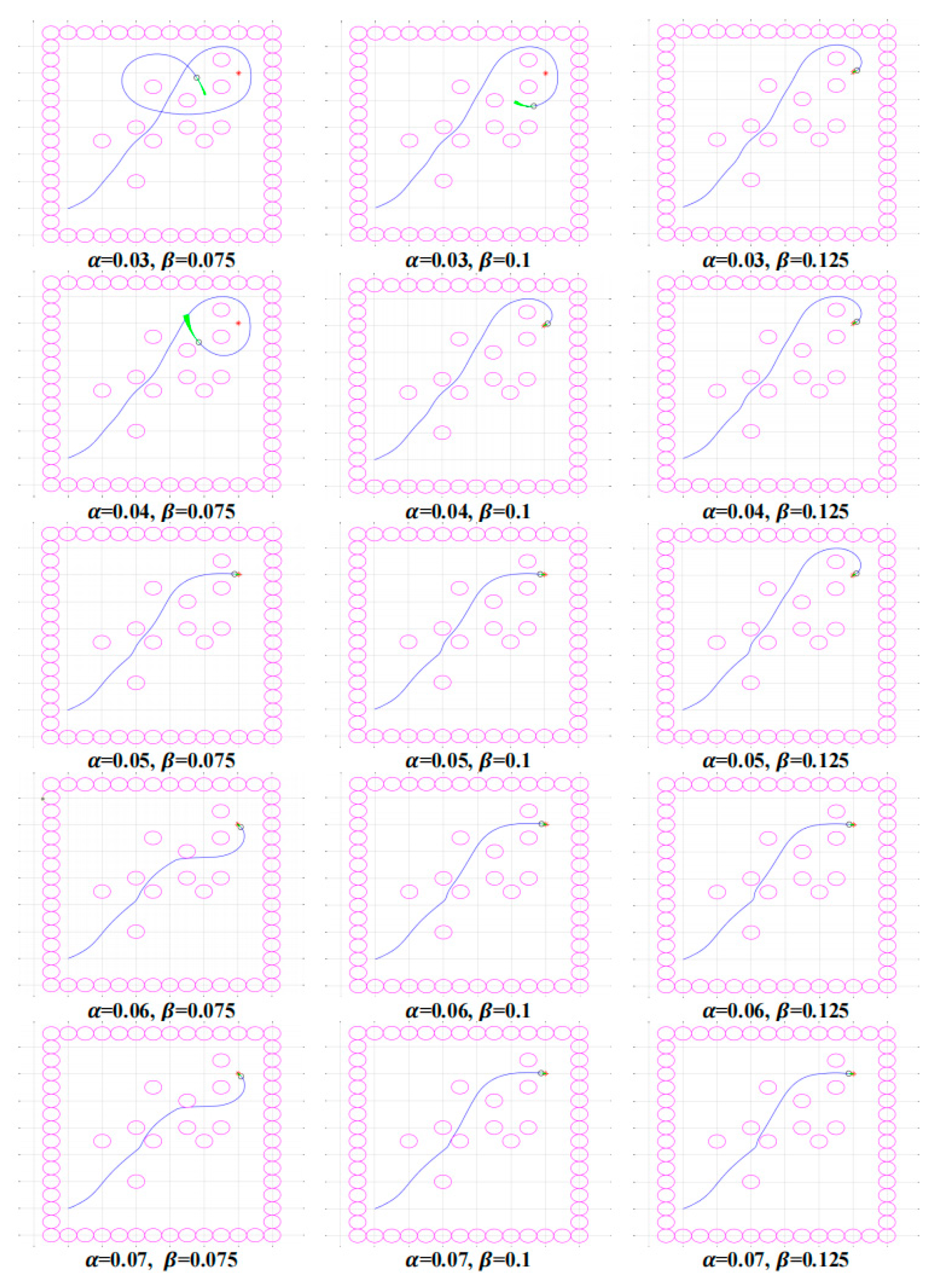

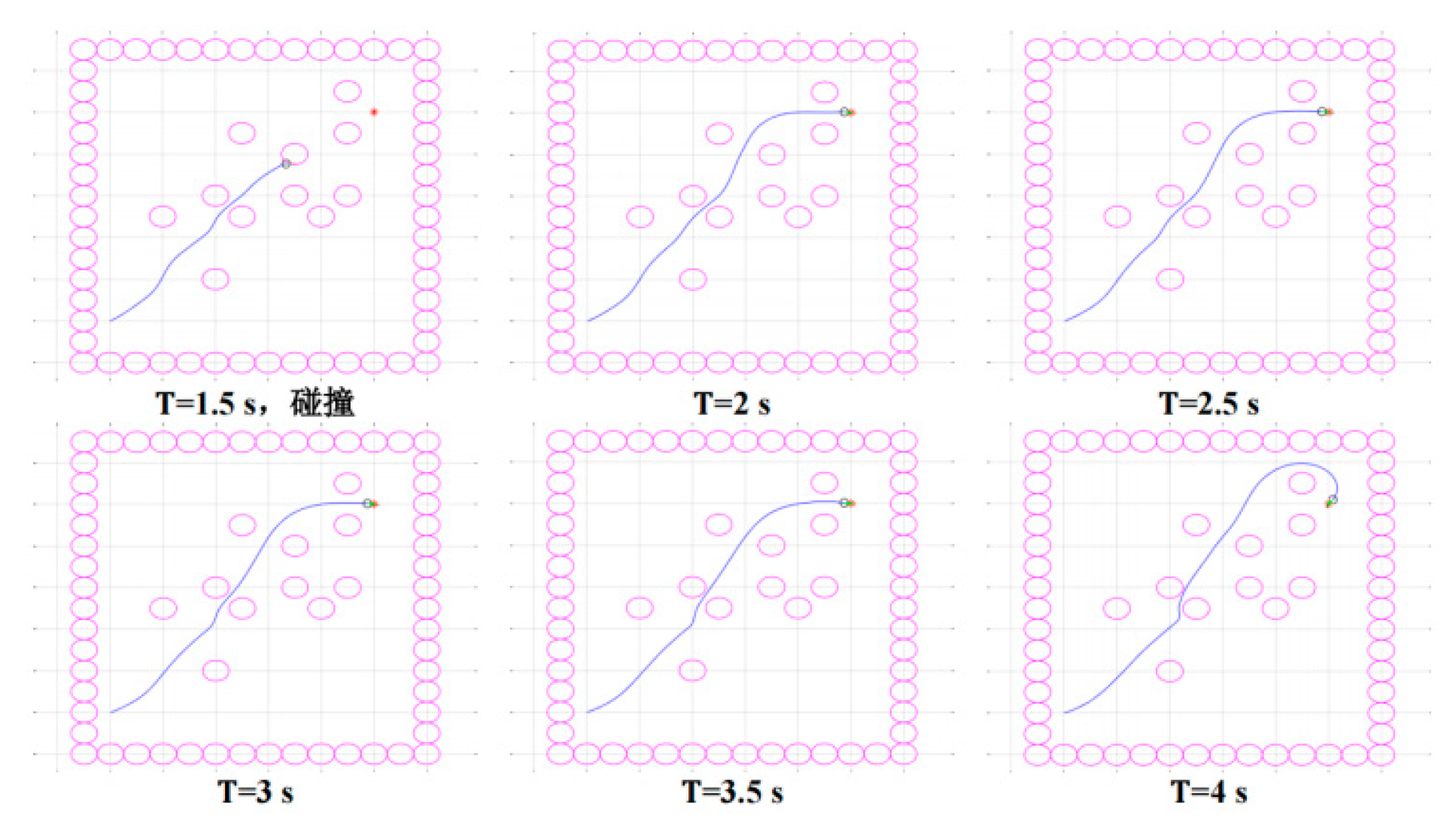

2.3.3. Local Path Planning and Obstacle Avoidance

3. Results

3.1. Test Method

3.2. Test Equipment and Materials

3.3. Test Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- This paper employs the Gmapping algorithm for the purpose of creating a map of the laboratory environment and generating a cost map for the robot. The AMCL method is utilised for the purpose of locating the egg-collecting robot and obtaining its pose information. To address the issue of the optimal sequence for collecting eggs, the ACA is implemented, resulting in the determination of the shortest path length and the optimal order of egg-collecting nodes. The target point for egg-collecting navigation is calculated in order to ascertain its world coordinate position. Subsequently, the Dijkstra algorithm is employed for global path planning for egg collecting, while the DWA algorithm is used for local path planning and obstacle avoidance of the robot. Simulation experiments were conducted on the Matlab platform to identify optimal parameter combinations for the DWA algorithm. The results indicated that a heading evaluation function weight of 0.05, a safety evaluation function weight of 0.1, and a speed evaluation function weight of 0.1 were the optimal parameter combinations;

- (2)

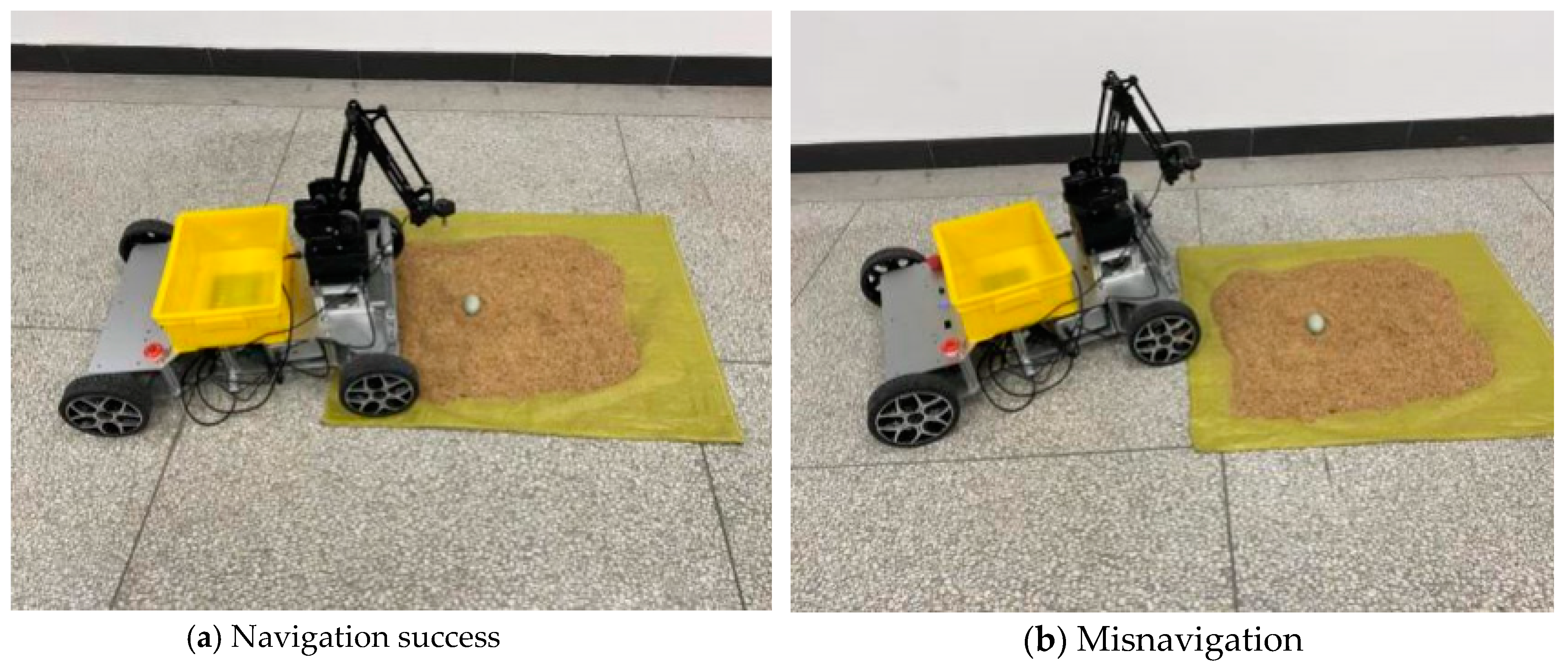

- A test platform was constructed in the laboratory to emulate the operational context of the egg-collecting robot. The robot's continuous egg-collecting navigation performance was evaluated through a series of tests, yielding an accuracy rate of 89.3%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, S.S.; Liu, L.Z. 2023 Waterfowl Industry and Technology Development Report. Chinese Journal of Animal Husbandry 2024, 60, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Song, J.S.; Bao, E.C.; Lin, Y.; Guo, B.B.; Ying, S.J.; Wu, Z.X. Waterfowl (duck) breeding mode and development trend based on environmental control. Journal of Animal Ecology 2024, 45, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Z. Research and judgment on the current situation and future trend of China's laying duck industry market. China Poultry Industry Guide 2024, 41, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Iulia, A.B.; Igori, B.; Ioan, P.; Lavinia, S.; Cosmin, A.P.; David, M.C.; Joanne, L.; Todd, C.; Alastair, D.; Nicolae, C. Mechanistic concepts involved in biofilm associated processes of Campylobacter jejuni: persistence and inhibition in poultry environments. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104328. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.W.; Cai, Y.M.; Yu, G.L. Bacterial and fungal aerosols in poultry houses: PM2.5 metagenomics via single-molecule real-time sequencing. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, L.H. The main problems and countermeasures in the management of layer breeding. Jilin Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine 2023, 44, 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Colin, T.U.; Wayne, D.D.; Benjamin, J.; Aneri, M. Robotics for Poultry House Management. 2017 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Paper No. 1701103, 1-8, Washington, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.; Colin, U. Autonomous robotic system for picking up floor eggs in poultry houses. 2017 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Paper No. 1700397, 1-5, Washington, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bastiaan, A.V.; Sam, K.B.; Joris, M.M.I.; Eldert, J.V. Evaluation of the performance of PoultryBot, an autonomous mobile robotic platform for poultry housess. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 174, 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaan, A.V.; Steven, V.H.; Joris, M.M.I.; Eldert, J.V. Object discrimination in poultry housing using spectral reflectivity. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 167, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaan, A.V.; Joris, M.M.I.; Eldert, J.V. Probabilistic localisation in repetitive environments: Estimating a robot's position in an aviary poultry house. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2016, 124, 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaan, A.V.; Gerard, L.V.W.; Peter, W.G.G.; Eldert, J.V.H. Path planning for the autonomous collection of eggs on floors. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 121, 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.J. Research on key technologies of intelligent collection trolleys for goose eggs. Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.J. The design of a duck egg picking robot in flat mode. Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, X.D.; Mao, S.J.; Yan, Y.C.; Yang, X.K. Review on SLAM algorithms for Augmented Reality. Displays 2024, 84, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lothar, S.; Kunal, K. Promising SLAM Methods for Automated Guided Vehicles and Autonomous Mobile Robots. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, Y.; Yong, K.C. Review of simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) for construction robotics applications. Automation in Construction 2024, 162, 105344. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Li, S.H.; Du, M.M.; Ji, G.L.; Li, K.S.; Liu, D. Terrain preview detection system based on loosely coupled and tightly coupled fusion with lidar and IMU. Measurement 2025, 242, 115924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.J.; Liu, H.B.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, Y.Y. Research on Multi-Sensor Fusion SLAM Algorithm Based on Improved Gmapping. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 13690–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.P.; Fan, Q.Y. Research on real-time positioning based on adaptive Monte Carlo algorithm. Comput. Eng. 2018, 44, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, W.Z.; Deng, Z.H. Global dynamic path-planning algorithm in gravity-aided inertial navigation system. IET Signal Process. 2021, 15, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample number | First navigation | Second navigation | Third navigation | Fourth navigation | Fifth navigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | T | F | T | T | T |

| 5 | T | T | T | T | F |

| 8 | T | T | F | F | F |

| 10 | T | F | T | T | T |

| 17 | F | F | F | F | F |

| 24 | T | F | T | T | T |

| 25 | T | T | F | T | F |

| 29 | T | T | T | F | F |

| Total number of failures | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).