1. Introduction

China is a large agricultural country, especially in recent years, with the increase in market demand for fruits, the planting area of fruits has increased annually[

1]. In particular, crabapples are widely planted in Northeast China because of their rich vitamins and unique taste[

2,

3]. Currently, there are few studies on the automatic picking of crabapples in China, and manual picking remains the primary method. To achieve automatic picking, research is conducted on crabapple-picking robots. However, the fruit growth distribution on the tree is relatively random and is blocked by obstacles such as fruit tree branches, leading to issues such as low picking efficiency and difficulty in picking[

4]. Therefore, in order to improve the picking efficiency of the picking robot on the tree and avoid the collision between the robot and the fruit tree branches during the picking process, the study of the multi-objective crabapples picking sequence planning and the obstacle avoidance problem of the picking robot has been conducted.

In recent years, scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted extensive research and experiments on the planning of fruit-picking sequences and obstacle avoidance for picking machines. These studies have yielded promising results that have been effectively applied in practical production settings[

5,

6]. Kurtser et al.[

7] used a target sequencing method to plan the picking order of densely planted bell peppers. Experimental verification under greenhouse conditions showed that the harvest cycle time is shortened by 12% compared with disordered random picking. Li et al.[

8] used a genetic algorithm to plan the order of multi-target fruit-picking tasks on trees, and compared with the disordered random method, the picking time was significantly shortened and the picking efficiency was improved. Ye et al.[

9] used the target gravity and adaptive coefficient adjustment method to improve the Bi-RRT algorithm to achieve collision-free picking of lychees on the tree, and the planning speed of the improved Bi-RRT algorithm was faster than that before the improvement. Cao et al.[

10] introduced target gravity into the RRT algorithm and used GA to optimize the path generated by the RRT algorithm, so as to plan the obstacle avoidance path of the lychee picking manipulator and improve the path quality and planning efficiency.

In order to solve the problem of continuous picking of multi-objective clustered crabapples on crabapple trees and avoid the collision between the robotic arm and the tree branches during the picking process, this paper proposes a method for planning the picking sequence and the obstacle avoidance path for picking, implemented through improved ACO and improved RRT algorithms. The adaptive pheromone factor and heuristic function factor are used to improve the transfer probability, and the adaptive volatility factor is introduced to optimize the pheromone update to improve the ACO algorithm to increase the convergence speed of the algorithm, in order to achieve the planning of the picking order of multi-objective crabapples on the tree. By combining the APF algorithm with the RRT algorithm to introduce the gravitational field, the guidance of the RRT algorithm path search is enhanced, the unnecessary inflection point is reduced, the convergence speed is improved, and the superiority of the improved algorithm is verified by simulation analysis compared with the previous RRT algorithm. Finally, a test platform was constructed to conduct a picking test analysis to verify the effectiveness and feasibility of the improved algorithm proposed in this paper.

2. Environment Setup

2.1. Sugarcane Tree 3D Reconstruction

During the process of picking clusters of crabapples from the trees, there may be obstacles such as tree branches on the picking path, leading to collisions between the robotic arm or end effector and the tree branches. This can result in damage to the robotic arm, end effector, or the crabapple trees and fruits, preventing the continuation of the picking task. Therefore, it is essential to first identify the location of the obstacles and conduct a three-dimensional reconstruction of the crabapple trees within the robotic arm's picking movement space. Given that the crabapple stalks, leaves, and fine branches (with diameters less than 3mm) are soft and will not cause damage to the picking movement robotic arm and end effector, this paper considers crabapple tree branches (with diameters greater than 3 mm) as obstacles.

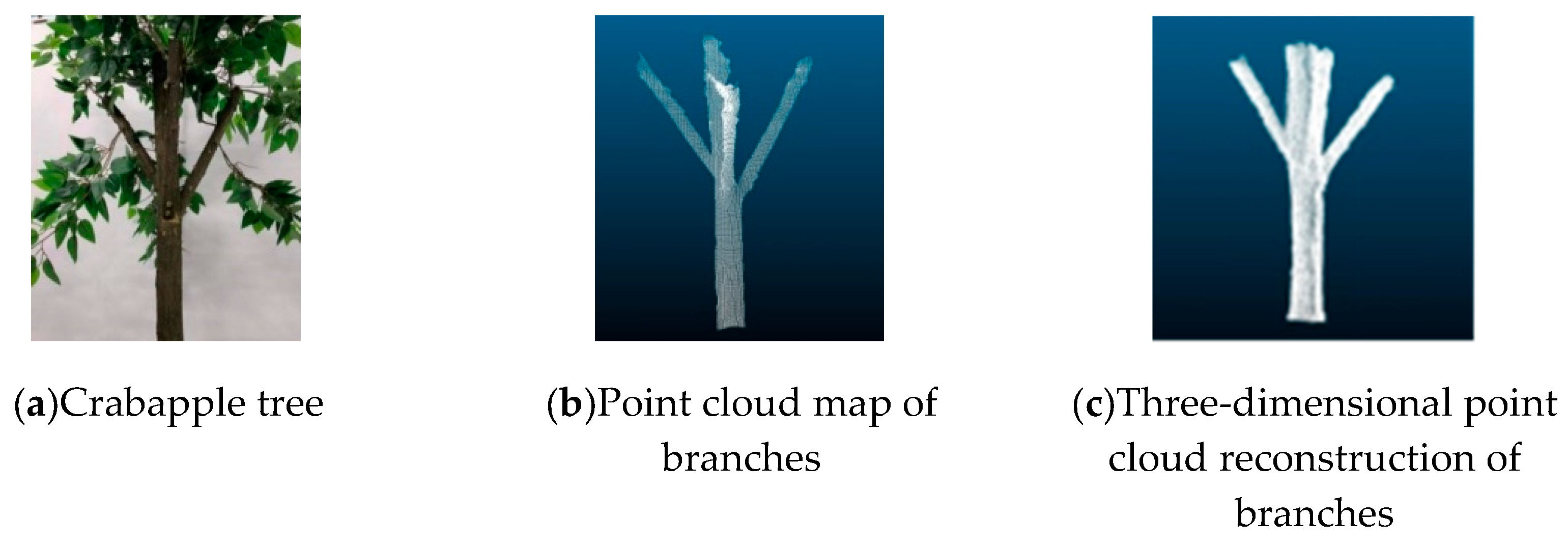

The Realsense D415 depth camera was used to obtain the cloud point map of the crabapple tree. The cloud point map of the tree is filtered by straight pass filtering, statistical filtering, and color filtering to remove the interference of the environmental background, leaves, and thin branches (radius less than 3mm) to obtain the point cloud map of the branches and trunks, as shown in

Figure 1.(b). The filtered point cloud map of the branches of the crabapple tree is matched, so as to realize the three-dimensional point cloud reconstruction of the branches of the crabapple tree as shown in

Figure 1.(c). The information on each branch is shown in

Table 1.

According to the cloud map parameters of each branch point of the crabapple tree in

Table 1, the complete space of the tree branches is constructed, which provides branch information for the collision detection between the next robotic arm and the tree. By constructing the crabapple tree branches and picking a robotic arm model, a more appropriate collision detection model is selected, and the branch information of the tree is provided, which provides obstacle position information for the obstacle avoidance path planning of the arm in the later stage, so as to facilitate the obstacle avoidance path planning of the robotic arm picking.

2.2. Robotic Arm Collision Detection Method

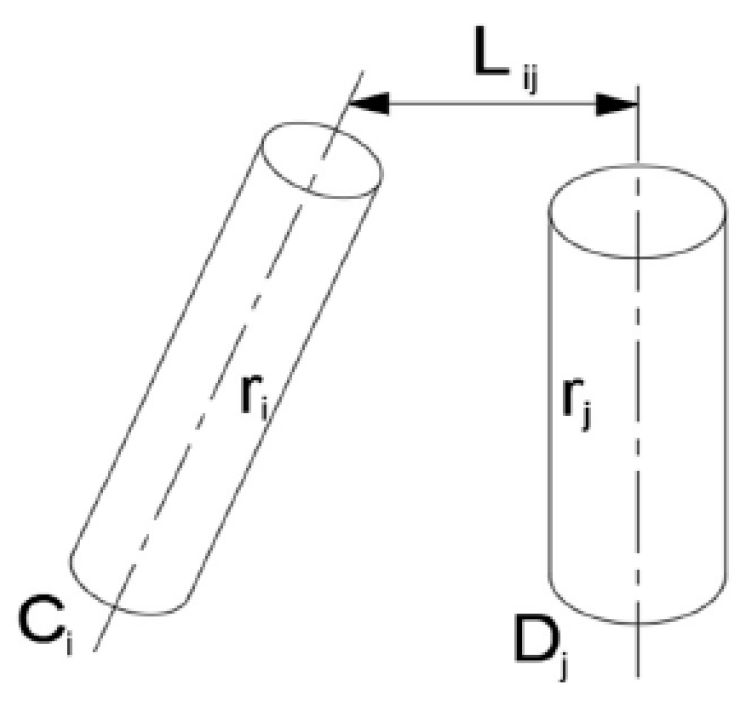

In order to avoid collision during the picking process, the collision detection among the arm, end effector, and branches of the crabapple tree was studied in this paper. According to its shape, a simple and reasonable cylindrical bounding box was selected to envelop it, which can simplify the collision detection process and improve the detection efficiency [

11]. Because the leaves and twigs (radius less than 3mm) of the tree will not affect the picking path and collision picking robotic arm, it can be ignored. The thicker branches of the tree were mainly enveloped by a cylindrical bounding box so that the collision detection problem of picking arm, end effector, and the tree branches could be simplified as the collision detection problem between cylinders, that is, it was converted into the shortest distance between cylinder and cylinder axis. By judging the relationship between the shortest distance between two axes and the sum of the radii of two cylinders, whether the picking robot collides with the branches could be judged. The positional relationship between the two enveloping cylinders is shown in

Figure 2. Among them,

means that the radius of the envelope cylinder between the joint

of the robotic arm and the joint

is

,

means that the radius of the envelope cylinder of the branches of the tree is

, and

means the distance between the axis of the envelope cylinder of the robotic arm and the branches of the tree, by comparing the relationship between

and

, it is determined whether the robotic arm collides with the tree branch.

3. ACO Algorithm Path Planning and Improvement

For the problem of sequential path planning for multiple crabapples picking in three-dimensional space, the complexity of path planning increases, requiring the algorithm to have strong robustness and global search capabilities. The Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm has shown good optimization results, strong robustness, and global search capabilities in solving the Three-Dimensional Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), which is more suitable for solving spatial multi-objective planning problems. However, the algorithm still has some drawbacks, such as long computation time, slow convergence speed, and the tendency to get stuck in local optimal solutions. Therefore, the ACO algorithm was improved and optimized in this paper, and it was used as a spatial algorithm for the multi-objective crabapples picking sequence planning algorithm.

3.1. Improved Transfer Probability

When the distribution of multiple fruit positions on a fruit tree is relatively random, if the picking robot picks randomly and in no order based on the spatial location information of the fruit obtained, a lot of picking time may be wasted and the picking efficiency may be reduced. Therefore, the spatial locations of multiple fruits on the identified tree will be analyzed and studied, and the picking sequence of multiple clustered crabapples will be planned to save picking time and improve picking efficiency. In this paper, the improved ACO algorithm was used to plan the picking sequence of multiple targets on the crabapple tree.

The analysis of the traditional ACO algorithm reveals that the pheromone factor

and the heuristic function factor

in its transition probability function are constants [

12]. However, research has shown that when

and

are set to be too large or too small, the ACO algorithm may exhibit a decrease in search efficiency, leading to the generation of local optimal solutions or an increased search randomness that hinders the discovery of the optimal solution. Therefore, this paper adopts dynamic heuristic function factor

and pheromone factor

, allowing them to change with the number of iterations. After analyzing the ACO algorithm, it is found that during the initial phase of the iteration loop,

plays a significant role in path search, and thus,

should be set to a larger value while

should be set to a smaller value. As the number of iterations increases, the concentration of pheromones on relatively shorter paths in global path planning is higher. At this point, the concentration of pheromones takes the lead in the path search, and to better find the optimal path and accelerate convergence, the value of

should be increased while the value of

should be decreased. However, as the iteration progresses toward the end, the concentration of pheromones on relatively shorter paths is significantly higher than on other paths. To avoid premature convergence, the impact of pheromone concentration on path selection should be reduced, which means decreasing the value of

and increasing the value of

. This adjustment will facilitate the search for the global optimal route. The improved

and

are:

In the formula: where is the current iteration number, is the maximum iteration number, and A, B, C, D are constants.

The improved transfer probability is:

In the formula:

represents the pheromone concentration at the persimmon picking point to picking point , is the heuristic function,

is the desired degree of Ant from the crabapple picking point to the picking point ,

is the Euclidean distance from picking point to picking point ,

is an ant that has not been collected at the picking point.

3.2. Optimized Pheromone Concentration Updates

In the process of path planning, the update of pheromones is a crucial task, that affects the global search ability of the path, in which the volatile factor

is one of the key factors affecting the concentration of pheromones on the path[

13], when

is too small, the ethereal volatilization of pheromones on the path is slow, resulting in the accumulation of pheromones on the path, causing the algorithm to converge prematurely and fall into the local optimum. When

is too large, the pheromone volatilization on the path is faster, and the search randomness and global search are enhanced, but the convergence time is longer. Therefore, in this paper, the adaptive volatilization factor

is introduced to optimize the update of pheromones, and at the beginning of the algorithm iteration,

takes a larger value to expand the randomness and globality of the search. In the later stage of algorithm iteration,

takes a smaller value to improve the convergence speed of the algorithm. The improved

can be calculated as follow.

decreases with the increase of the number of iterations, and the pheromone concentration disappears faster in the previous stage of the path plan./8zning, and the global search is strong. With the increase of the number of iterations, the path planning tends to be stable and the convergence speed accelerates, and the optimized pheromone update rules are as follows:

In the formula:

represents the increment of pheromone from apricot picking point

to picking point

by ant

.

In the formula: Q is a constant, represents the path taken by ant .

The specific algorithm flow of the improved ACO algorithm is as follows:

1) Initialize the parameters such as the number of picking points n and the number of ants m. The initial pheromone concentration (c is a constant), the sum of the pheromones left by the ants on the path from picking point i to j at the initial moment , the initial number of iterations , and the maximum number of iterations is .

2) Place m ants randomly at n picking points, and add the ant placement points to the taboo table .

3) The improved transition probability principle is used for ant (=1~m), ant k moves to the next picking point, and the moved picking point is added to the until the n picking points are traversed.

4) Calculate the path length of each ant , ( represents the path of the kth ant from picking point to picking point , =1,2,3,...,m).

5) Calculate the path length traveled by ant after completing an iterative cycle, and update the global shortest path.

6) Update the pheromone concentration on the path according to formulas (4), (5), and (6).

7) Prepare to continue the looping again while , if , the loop ends and outputs the optimal solution. Otherwise, return to Step 2).

3.3. Comparison of Ant Colony Algorithm Before and After Improvement

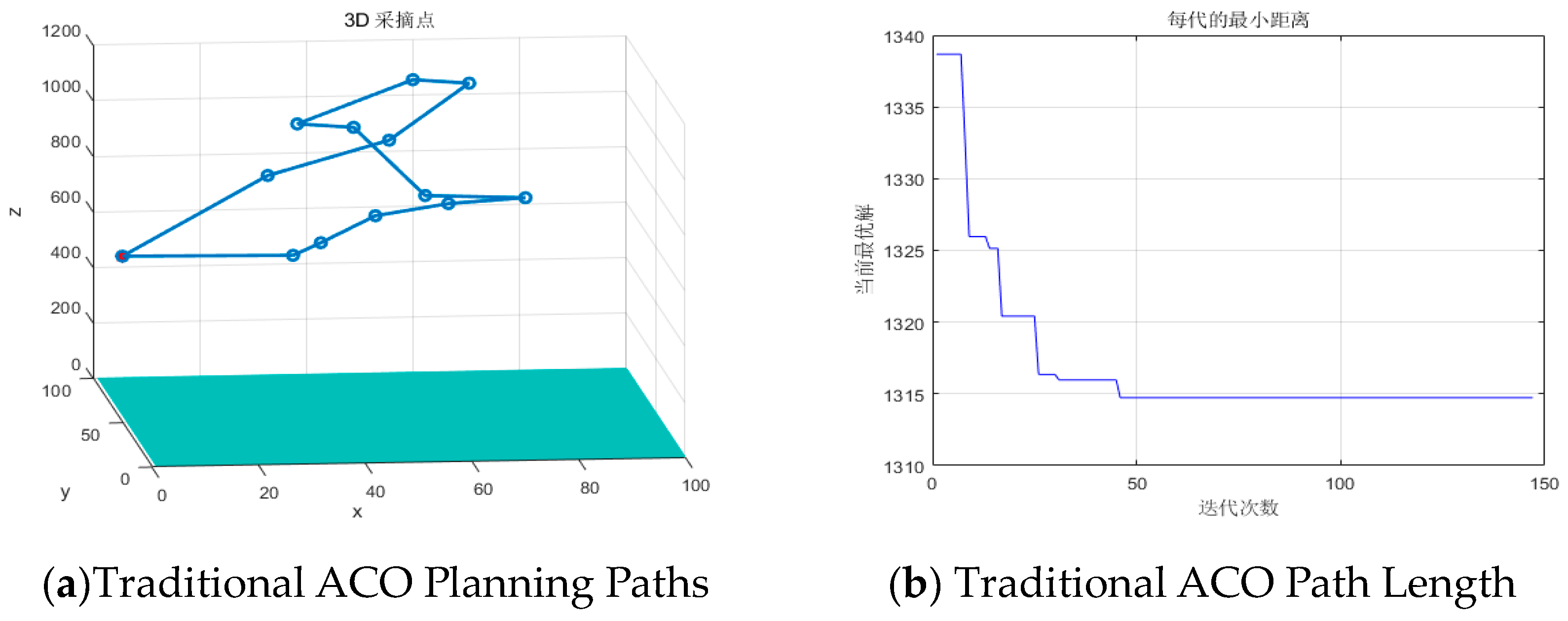

The improved ACO algorithm was compared with the traditional ACO algorithm, and the simulation experiments were conducted to verify the feasibility and superiority of the improved ACO algorithm. The simulation results of the picking sequence planning for multiple target picking points in three-dimensional space are shown in

Figure 3., where the red solid indicates the starting point of the end effector of the robotic arm.

Figure 3.(a) indicates the picking sequence planned by the traditional ACO algorithm,

Figure 3.(b) indicates the optimal path length of each iteration of the traditional ACO algorithm,

Figure 3.(c) shows the picking order of the improved ACO algorithm, and

Figure 3.(d) showed the optimal path length of each iteration of the improved ACO algorithm. The test results are shown in

Table 2.

The improved ACO algorithm and its predecessor were planned in a 100×100×1200 three-dimensional space, with the starting coordinates at (0,50,600) (a red solid point), to map out the sequence of multiple crabapples picking paths for the end-effector of a robotic arm, starting and ending at the same point. As shown in

Figure 3.(a) and (c), both the planning algorithms can successfully plan the sequence of picking multiple points without traversing the same picking point multiple times, thus validating the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed algorithm. By comparing

Figure 3.(b) and (d) and

Table 2, it can be seen that the improved ACO algorithm has shorter paths, fewer iterations, and faster convergence speed. Therefore, the improved ACO algorithm in this paper outperforms the traditional ACO algorithm in planning the sequence of picking multiple points.

4. Improve Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for RRT

4.1. Based on RRT and APF Algorithms

The Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithm is a type of random sampling method, in which the starting point is used as the root node and the target point is used as the end node, and the intermediate node is added to expand a random tree by randomly selecting the sampling point in sampling space [

14]. The algorithm has the advantage of probabilistic completeness, which can search for the picking path without solving all the spatial points,and quickly and effectively plan the picking path in the 3D sampling space. RRT algorithm has a strong search ability and is suitable for high-dimensional space. However, it has some disadvantages, such as high randomness of sampling points, which may result in a large number of offset target points, leading to long operation time and uneven paths planned by the algorithm [

15].

Artificial Potential Field (APF) is a widely used obstacle avoidance path planning algorithm, which assumes that there is repulsion on the obstacle and gravity at the target point, and the combined force of gravity and repulsion is used as the direction of motion of the moving object, and the target point has an attraction to the moving object, inducing the moving object to move towards the target point, and the obstacle has a repulsive force on the object, so as to effectively avoid the collision between the moving object and the obstacle [

16]. Its advantage is that it does not need to accurately obtain the spatial location of obstacles and can effectively avoid obstacles in space. However, when the moving object is subjected to the repulsive force and the force of attraction are in the same straight line and in opposite directions, the moving object falls into the local optimal solution and cannot reach the target position, or when the distance between multiple obstacles is close, the robotic arm is prone to unstable states such as wandering and shaking, resulting in vibration and deadlock phenomenon [

17]. Therefore, the APF algorithm is not suitable for obstacle avoidance path planning of the robotic arm alone.

According to the respective advantages and disadvantages of common path planning algorithms, the RRT algorithm and APF algorithm were combined to plan the collision-free picking path of the picking points on the crabapple tree in this paper.

4.2. Improvements to RRT

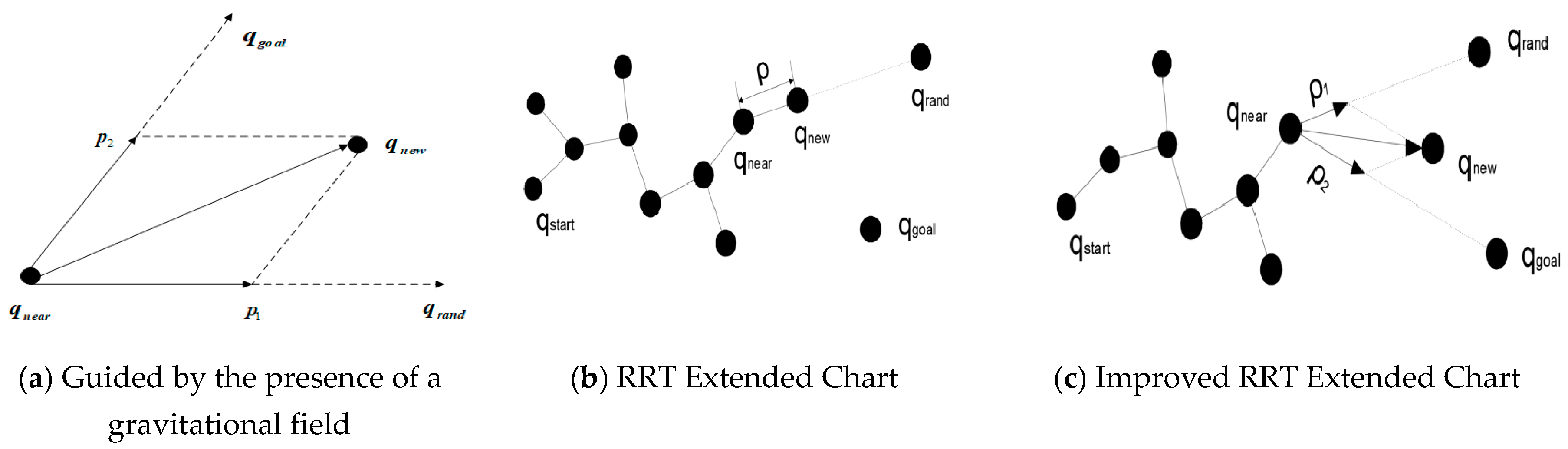

The RRT algorithm and the APF algorithm were combined to enhance the search towards the picking point. Integrating the gravitational field of the APF algorithm into the RRT algorithm, the target point had a gravitational field guiding the nodes of the random tree to deviate towards the target point, which reduced unnecessary redundant nodes and shortened computation time, thus accelerating the convergence speed. The specific algorithm process was as follows:

1) Set as the starting point of exploration, as the final destination point, where both and are points in the workspace ;

2) Set as the root node of random tree ;

3) Sampling points are obtained by random sampling in the working interval for each iteration;

4) Search for the node closest to in the random tree , denote it as ;

5) Starting from , generate a new node with a specific step size in the direction from to , and generate a new node under the gravitational field of the target point with a certain step size from , where both new nodes and are in the working space ;

6) Generate a new node in the direction of the diagonals formed by the parallelogram from to and from to ; then, denote the path from node to the new node as ;

7) Judge whether meets the obstacle avoidance conditions within working area . If it does, set as the new node; if not, return to step 3) to re-find a randomly sampled point ;

8) If the obstacle avoidance conditions are met, repeat steps 3) to step 7) in the next iteration cycle until node

is reached, and

to

paths are output. The comparison chart of RRT before and after improvement is shown in

Figure 4.

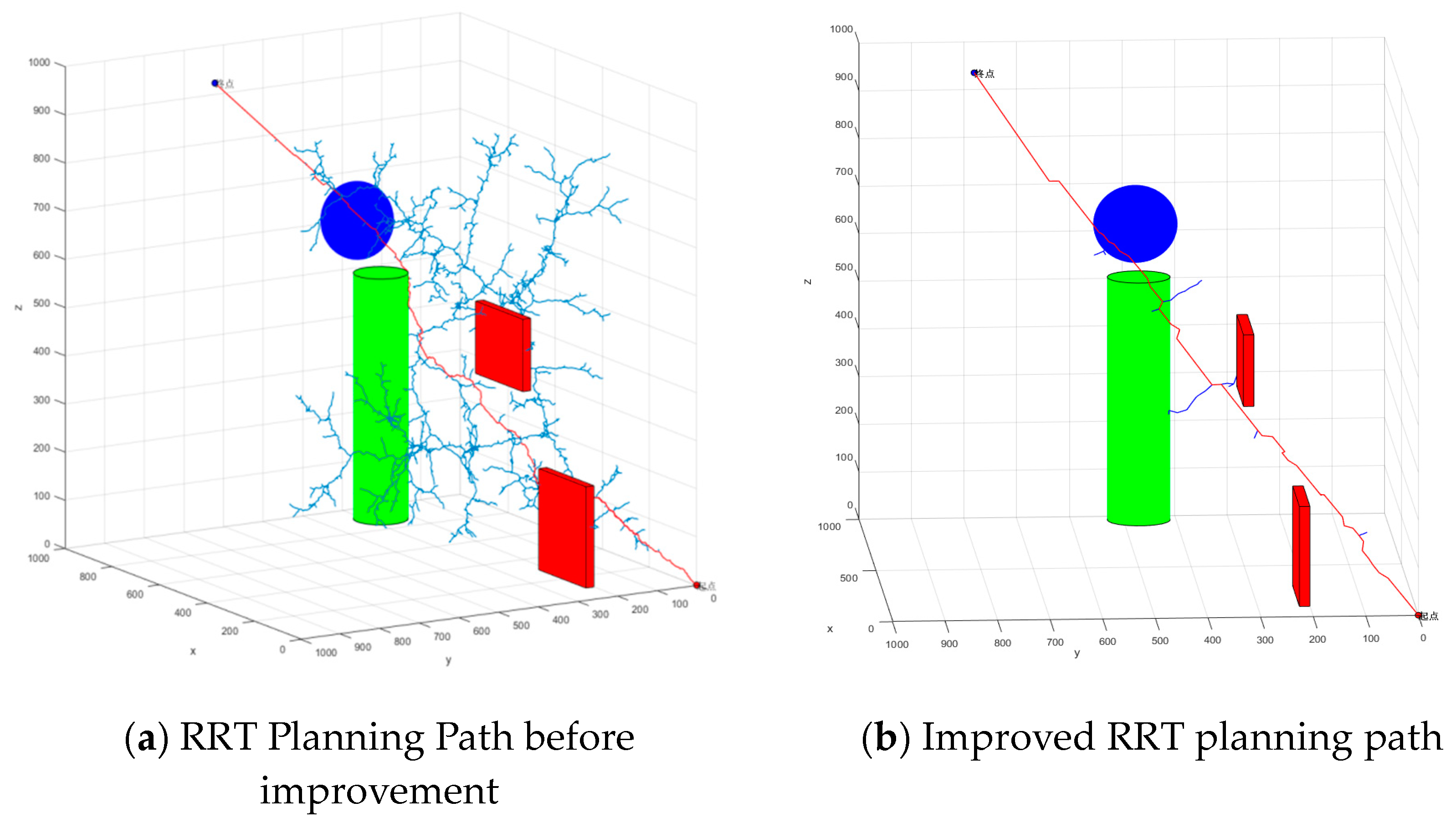

4.3. Comparison of RRT Before and After Improvement

The improved RRT algorithm after adding the gravitational field is compared with the original RRT algorithm, and simulation experiments were carried out to analyze and verify the validity and superiority of the improved RRT algorithm, with red representing the starting point (0,0,0), blue representing the endpoint (700,800,1000), and using three types of models-green cylinders, blue spheres, and red cuboids as obstacles. The simulation test results are shown in

Figure 5., where

Figure 5.(a) depicts the planning path of the RRT algorithm before improvement, and

Figure 5.(b) depicts the planning path of the improved RRT algorithm.

The improved front and rear RRT algorithms are compared in a three-dimensional space of 1000×1000×1000, with a starting point of (0,0,0) and an ending point of (700,800,1000). The collision-free path from the starting point to the endpoint was planned in a three-dimensional space with obstacles. It can be seen from Fig.5, that path planning of the RRT algorithm with gravitational field extends rapidly towards the endpoint to avoid random diffusion of random trees around. At the same time, the path planning search time of the RRT algorithm with gravitational field from the start to the endpoint is 2.17s, while the path planning search time of the RRT algorithm without improvement is 7.34s. Therefore, it can be concluded that the search orientation of the improved RRT algorithm can shorten the operation time and improve the search efficiency.

5. Picking Test and Result Analysis

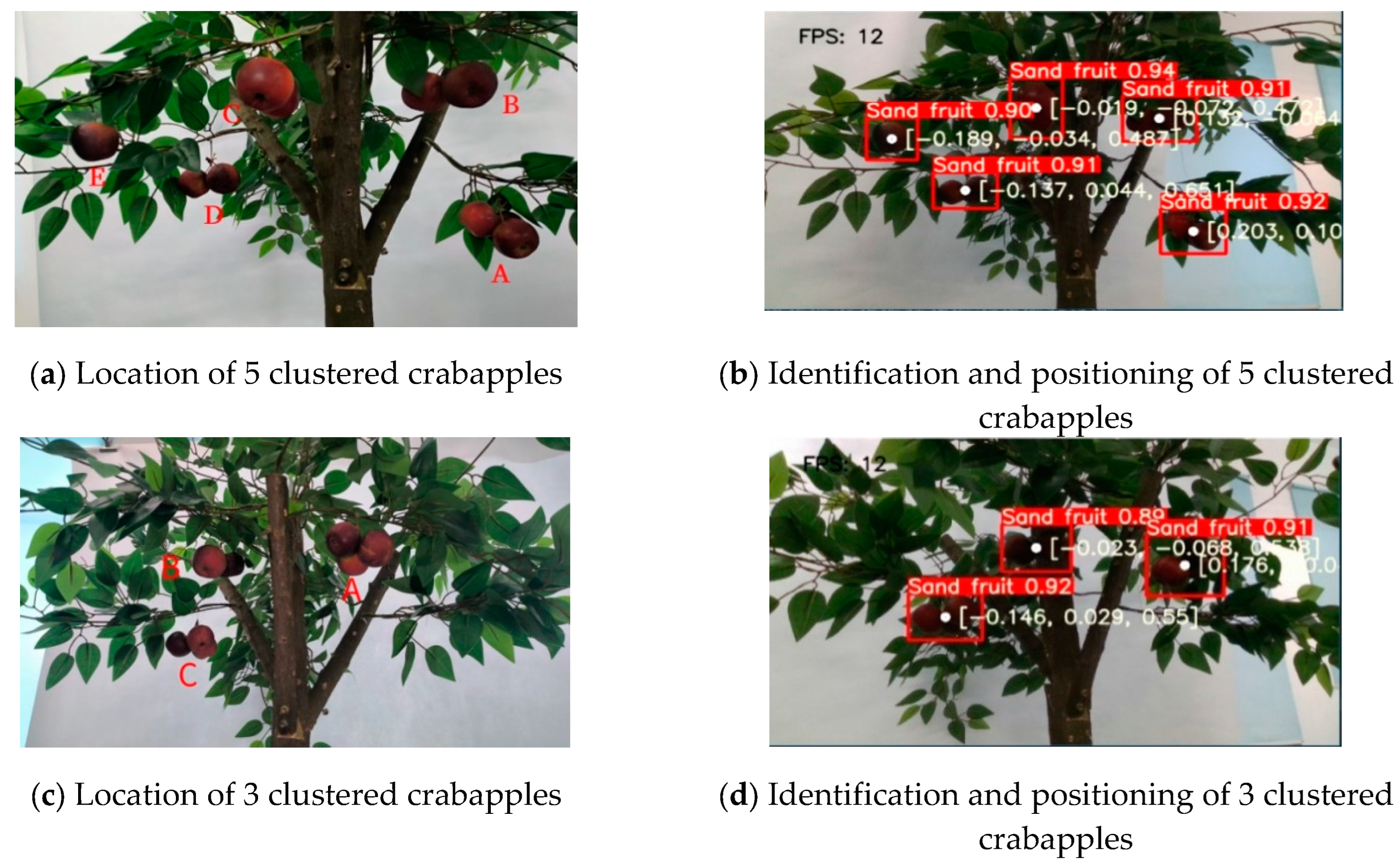

5.1. Identification and Positioning

The YOLOv5 algorithm improved by incorporating CBAM and BiFPN structures was adopted, which utilize the Realsense D415 depth camera for the identification, localization, and detection of crabapples from different angles, fruit quantities, and cluster quantities on trees. The three-dimensional spatial coordinates of crabapple picking points were outputted and saved, as illustrated in

Figure 6.(b) for the random placement of five clustered crabapples on a tree, and

Figure 6.(d) for the identification and localization of three clustered crabapples at random positions on a tree. The corresponding output coordinates are listed in

Table 3. Furthermore, the actual distance from the camera to the fruit was measured using a measuring tool for error analysis.

Comparing the spatial coordinates of crabapples obtained by the D415 camera with the actual measured positions, it was found that there was a certain error between the coordinates obtained by the D415 camera and the actual measurement results, as shown in

Table 3. Specifically, the average error in the X-axis direction is 3.25mm, in the Y-axis direction is 3.375mm, and in the Z-axis direction is 2.875mm. By calculating the relative error for each picking point, it was found that the relative error for each group did not exceed 2%. This indicated that using the D415 camera for crabapples positioning was relatively accurate and met the positioning requirements, thus proving the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed method of using the Realsense D415 depth camera for clustered crabapples recognition and localization.

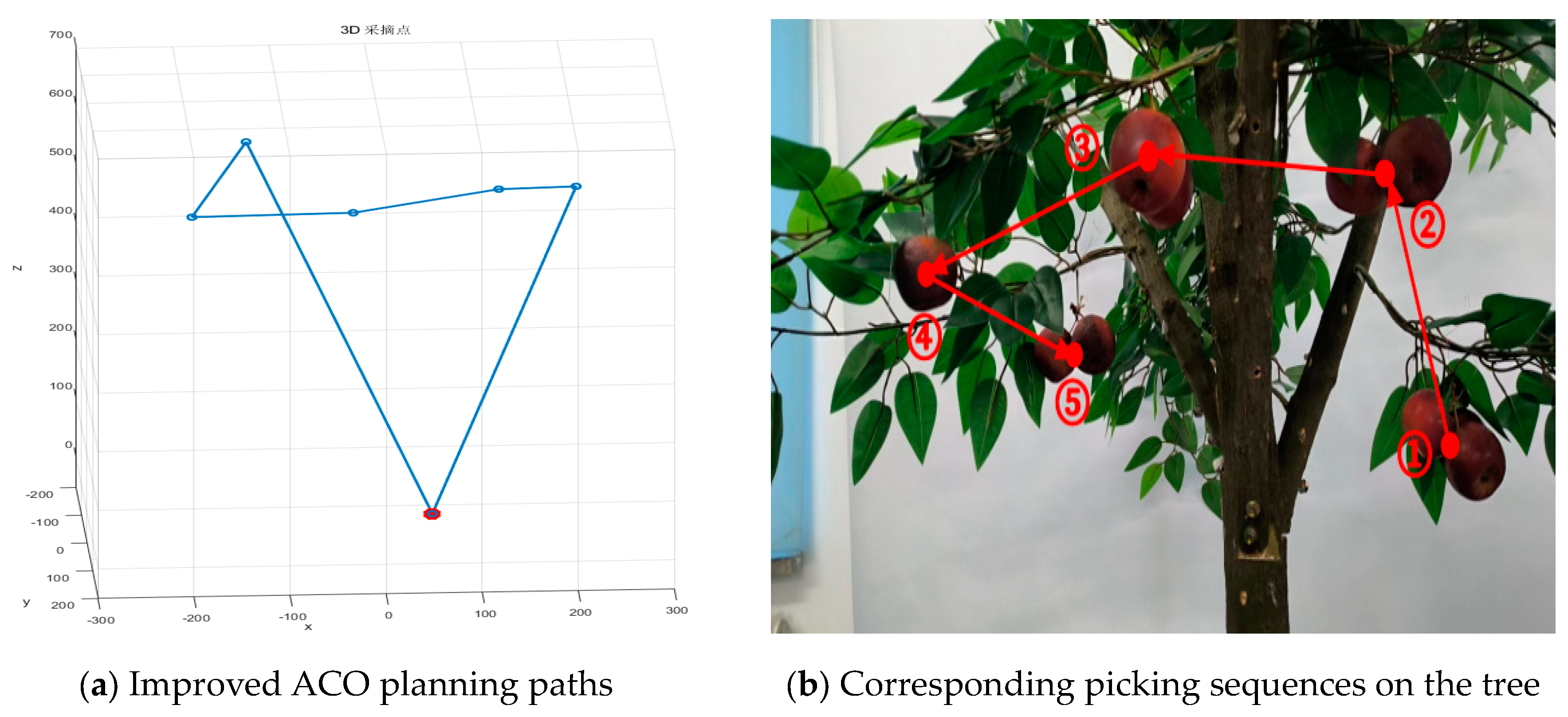

5.2. Multi-Objective Picking Sequence Planning on Crabapple Trees

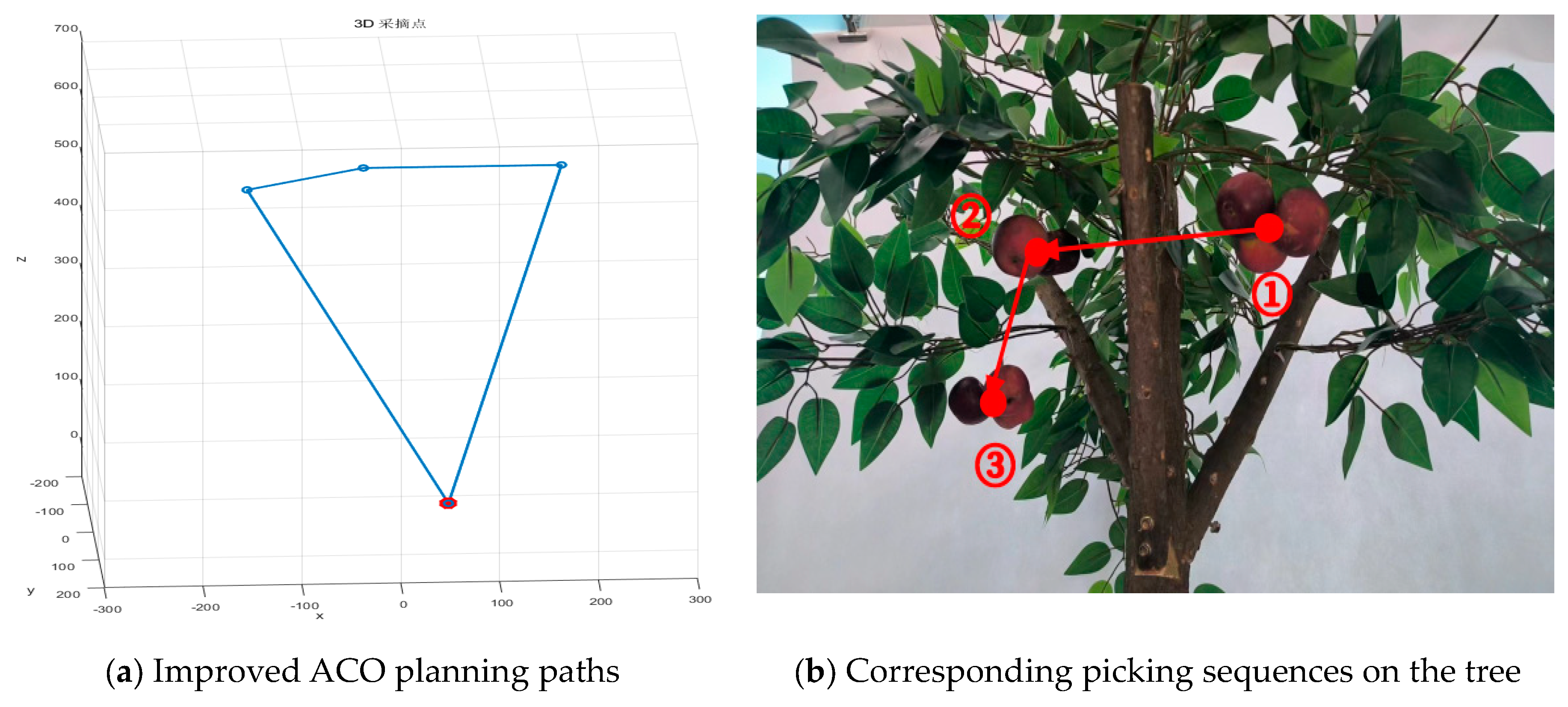

The problem of picking the sequence of multiple crabapples on the tree was simplified to the TSP problem in three-dimensional space. Based on the spatial coordinate position information identified and located in the previous text, the improved ACO algorithm was used to pick the sequence of 3 clustered crabapples and 5 clustered crabapples on the tree respectively. In order to better reflect the picking sequence, the spatial coordinate unit of the clustered crabapples was converted from m to mm, and the initial positions of the end effector of the robotic arm were represented by solid red dots, and the picking points of clustered crabapples were represented by hollow blue dots. The planning results of the picking sequence of 5 clustered crabapples on a three-dimensional fruit tree are shown in

Figure 7.(a). The corresponding picking sequence on the tree was represented by red sequence numbers and red arrows, as shown in

Figure 7.(b). Similarly, the planning results of the picking sequence of 3 clustered crabapples and the corresponding picking sequences on the tree are shown in

Figure 8.

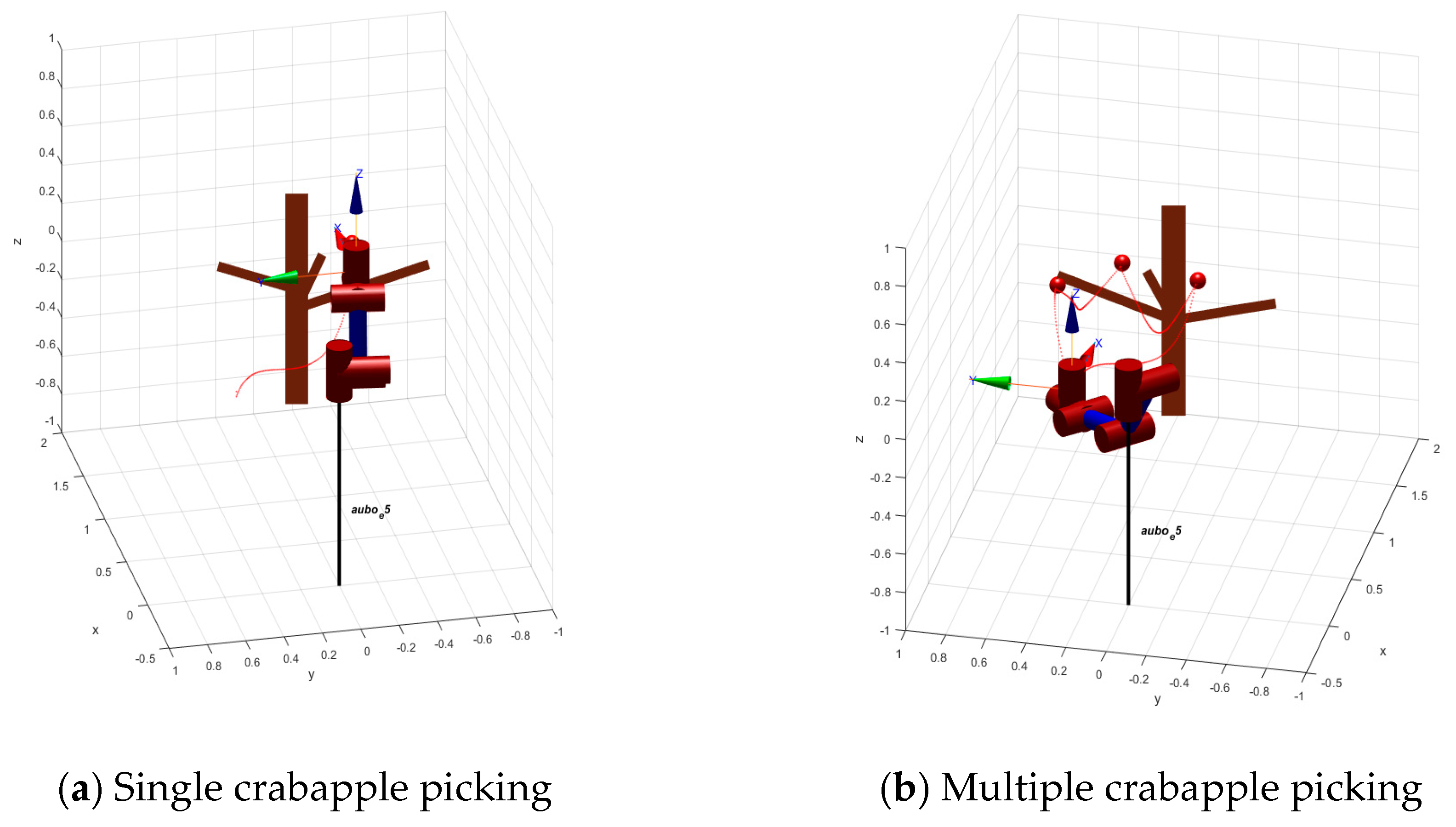

5.3. Simulation Analysis of Crabapples Picking Robotic Arm

Based on the three-dimensional reconstruction of the branches of crabapple trees, the improved RRT algorithm was used to analyze and study the simulation experiment of obstacle avoidance paths for robotic arm picking. In this experiment, Matlab 2020a was used as the simulation platform for obstacle avoidance and picking path planning of crabapples. The AUBO-E5 six-degree-of-freedom robot was employed to pick crabapples, and the D-H model of the AUBO-E robot was created. The robot toolbox in Matlab was used to solve the motion of the robotic arm. The initial position of the robotic arm was [0.57, 0.41, 0.1], and the crabapples were located on the slender branches between the two main branches (with a radius less than 3mm) and on the main branches. The tree was reconstructed in three dimensions, and the improved RRT algorithm was used to plan the path for picking crabapples. The analysis was focused on whether the joints and links of the robotic arm collided with the tree during the picking process. If no collision occurred, the end of the robotic arm would start from its initial position for crabapple picking. If a collision occurred, the path would be replanned. The simulation of picking and obstacle avoidance for single and multiple crabapples on the tree is shown in

Figure 9.

Continuous picking experiments were conducted respectively on single crabapple and multiple crabapples from thin branches (with a radius less than 3mm) between two thick branches of the tree. The experiment results showed that there was no collusion between the robotic arm and the branches of the tree during the picking process. It verified that the improved algorithm presented in this article could successfully plan the obstacle avoidance path for the robotic arm, ensuring that the robotic arm could avoid collision with the thick branches of the tree during picking operations, and complete the predetermined work tasks.

5.4. Multi-Target Clustered Crabapples Picking Experiment

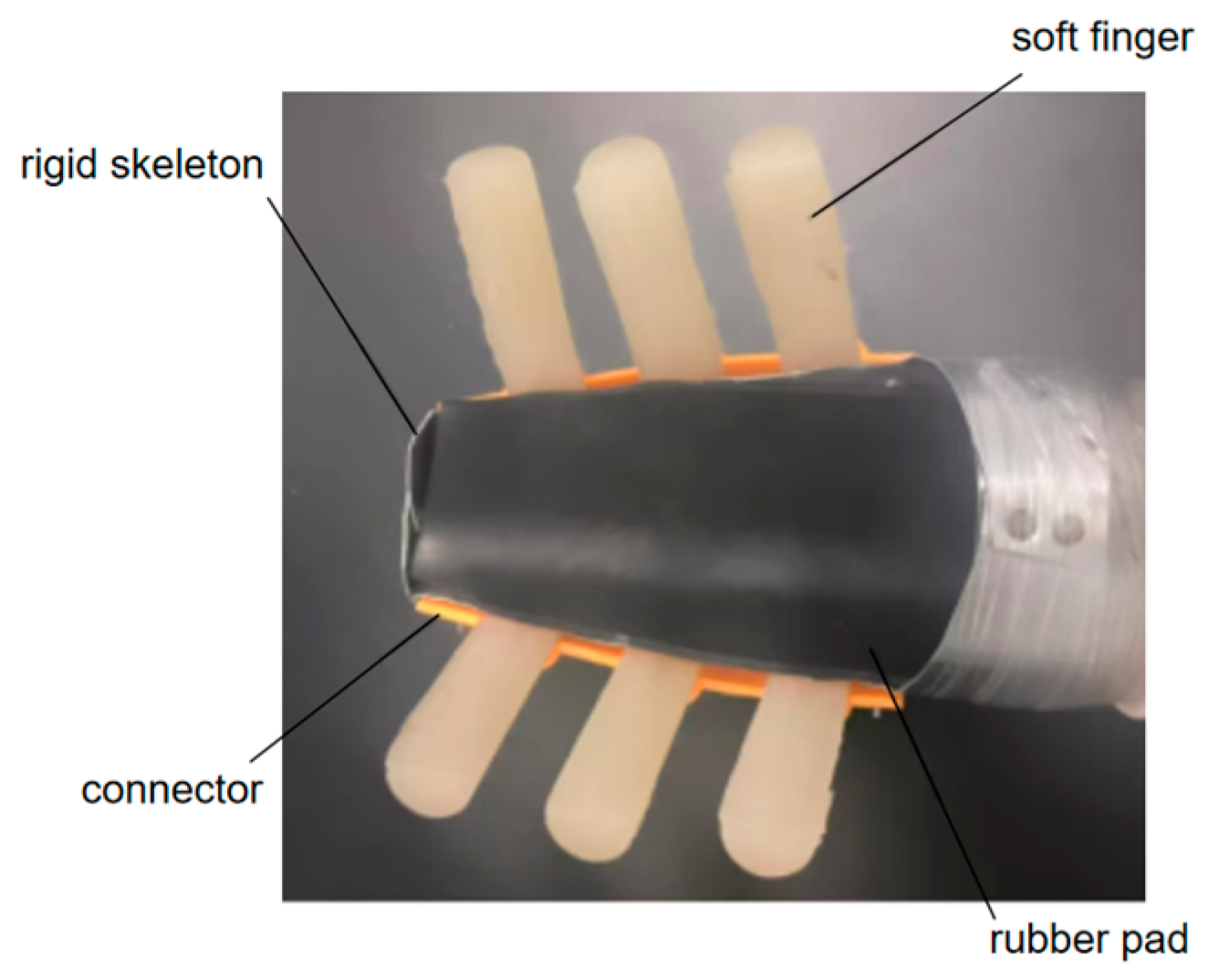

5.4.1. Rigid-Flexible Pneumatic Coupling Picking Manipulator

In order to avoid damage to the crabapples by the end effector and ensure the strength and stiffness of the robotic arm during the picking process, the rigid-flexible pneumatic coupling picking manipulator self-made by the research group was used as the end effector for these picking experiments, as shown in

Figure 10.

The rigid-flexible pneumatic coupling picking manipulator consists of six pneumatic soft fingers, a rigid skeleton, a rubber pad, and two connecting parts. Its working principle is as follows. The 0.08MPa air pressure is used to drive the soft fingers to bend, envelope the clustered crabapples, and cooperate with the rigid skeleton to complete the task of picking the clustered crabapples on the tree. The soft fingers are made of silicone material to avoid damage to the crabapples caused by the rigid structures.

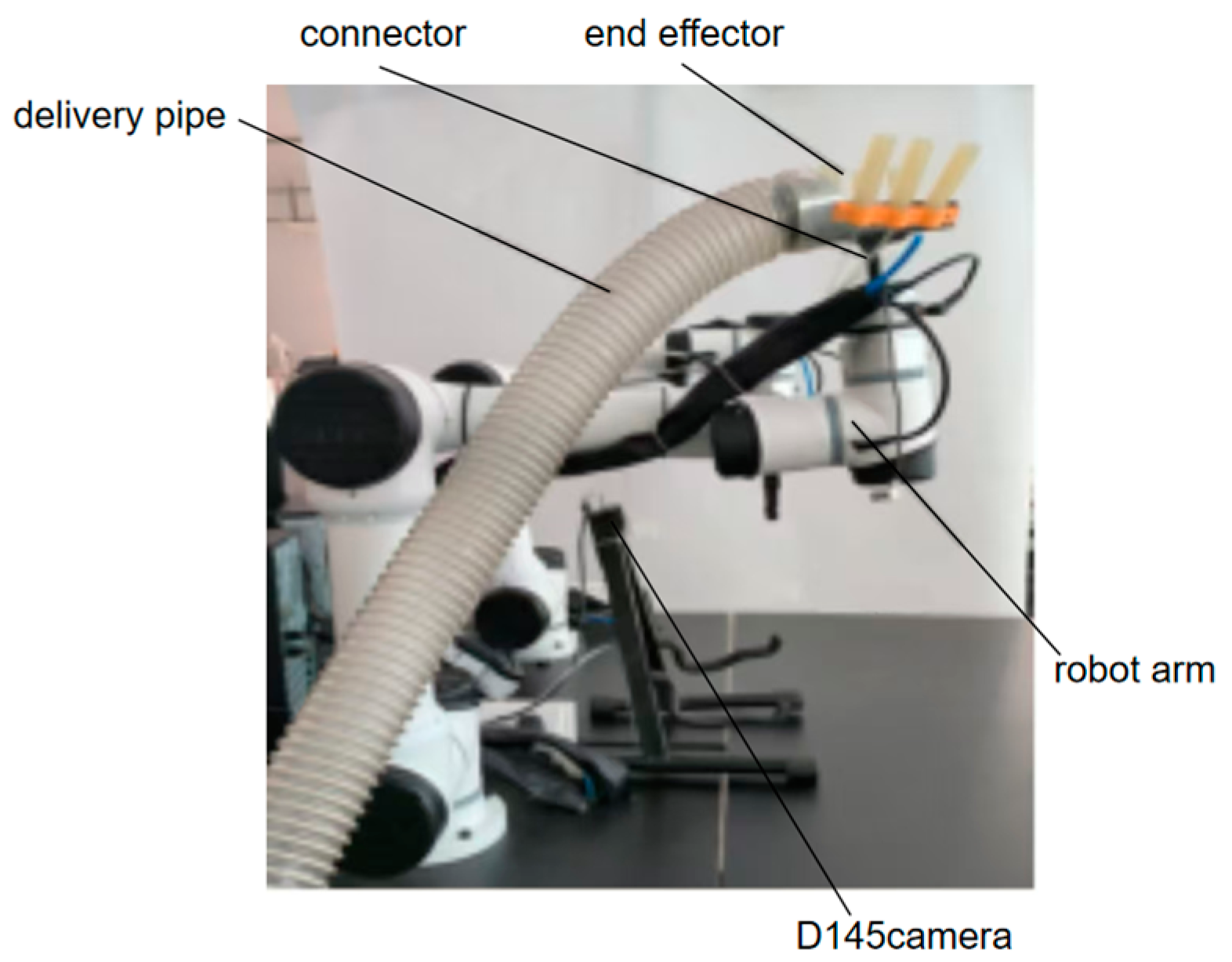

5.4.2. Construction of the Picking Test Platform

In this test, the rigid-flexible pneumatic coupling picking manipulator was installed on the AUBO-E5 robotic arm, and the D415 camera was fixed on the picking platform at a relatively stationary position relative to the base of the robotic arm. The crabapples were identified and positioned, and their identification and positioning information was transmitted to the controller of the robotic arm. The robotic arm and the rigid-flexible pneumatic coupling picking manipulator were controlled to cooperate to complete the picking task by the controller. The picking test platform is shown in

Figure 11.

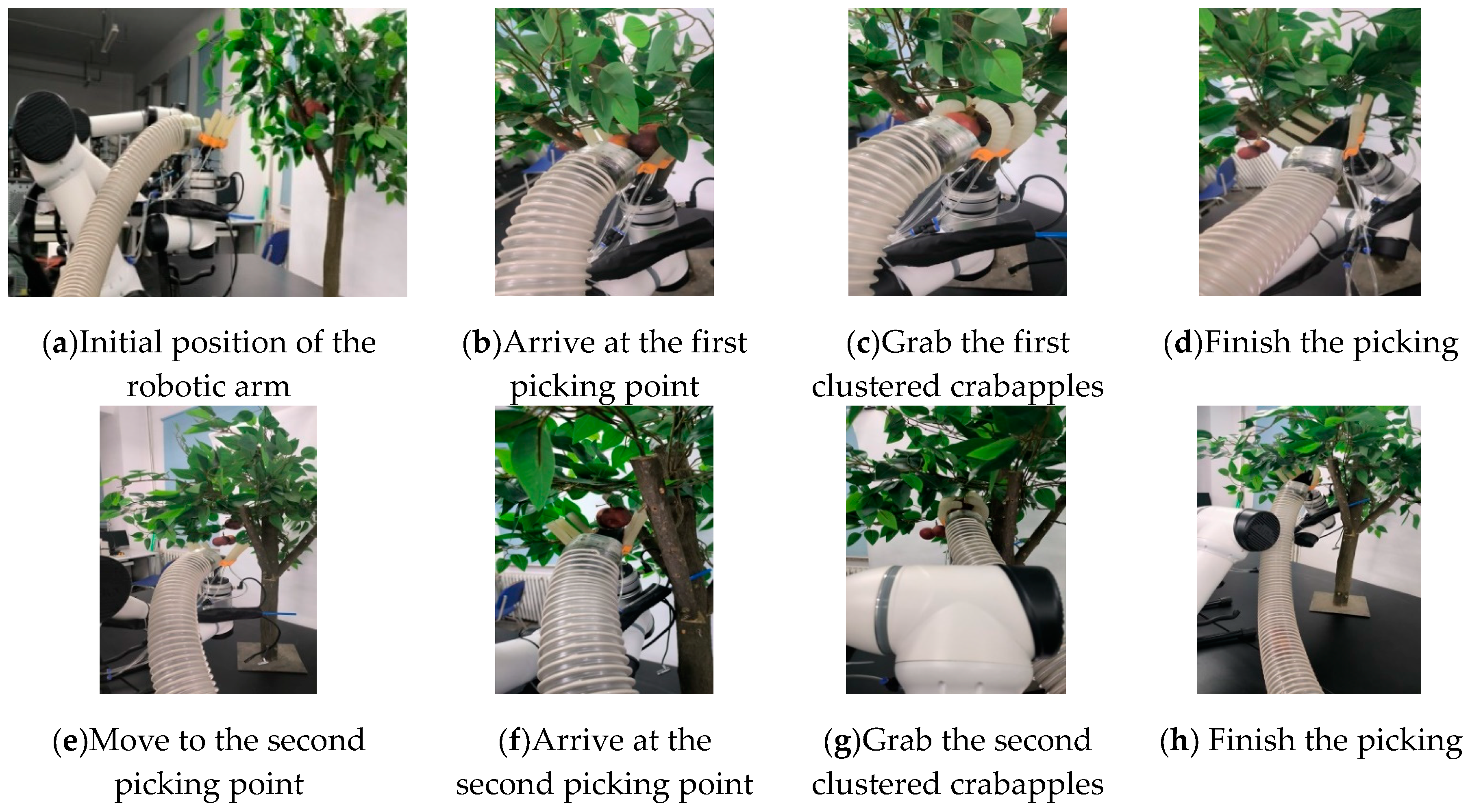

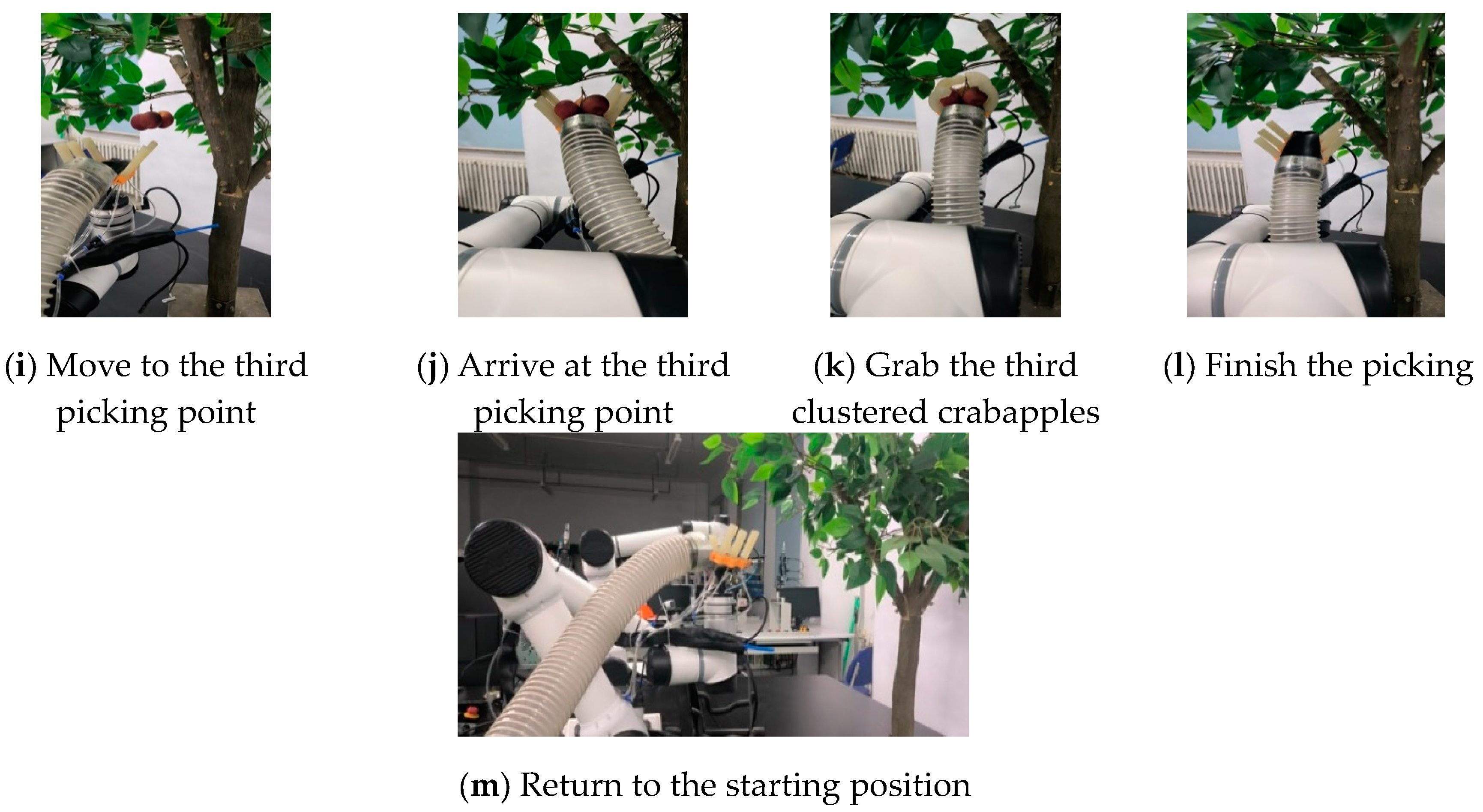

5.4.3. Crabapples Picking Test

In order to verify the feasibility of the picking test platform for crabapples picking, validation tests of the overall picking operation effect were conducted after completing the construction of the test platform. The artificial simulation crabapple tree was used for the picking tests and the crabapple picking test progress is shown in

Figure 12.

From

Figure 12., it can be seen that the end effector moves to the first picking point from the initial position, the soft fingers are used to envelop the clustered crabapples, and then the clustered crabapples are picked through the end effector movement. As the fingers are released, the picked crabapples will be transported to the collection basket through the conveyor pipe. By the improved RRT obstacle avoidance path planning, the end effector is moved to the second picking point to realize the picking of the second clustered crabapples. Then the picking of other clustered crabapples on the tree is completed sequentially, and finally, the end effector is returned to the initial position to wait for a new picking task.

To further verify the feasibility and accuracy of the clustered crabapples picking test, multiple groups of different clusters (ranging from 1 to 6) were placed at random positions. The success rate of recognizing, positioning, and picking clustered crabapples, as well as the number of collisions between the robotic arm and the tree, were used as evaluation indicators for the crabapples-picking robot. The experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

From the experimental data in

Table 4, it can be seen that the average recognizing success rate of the robot for clustered crabapples (1 to 6) is 95.83%, the average positioning success rate is 93.75%, and the average picking success rate is 89.58%. Moreover, there are no collisions between the robotic arm and the main branches of the tree during the picking process, which meets the actual picking needs. Therefore, it can be concluded that the algorithm proposed in this article for recognizing, positioning, and planning the robotic arm’s picking path of clustered crabapples is effective and feasible.

6. Conclusion

In order to achieve continuous obstacle-avoidance picking of multi-target clustered crabapples on the tree, and avoid collision with the tree branches during the picking process, the picking sequence and obstacle avoidance plan for picking clustered crabapples on trees was studied to improve the efficiency of picking and save picking time.

(1) The problem of picking the sequence of multiple crabapples on the tree was simplified to the TSP problem in three-dimensional space. The ACO algorithm was improved by improving transition probability and optimizing pheromone concentration update. Compared with the traditional ACO algorithm, it can be concluded that the improved ACO algorithm has shorter picking sequence paths, fewer iterations, faster convergence speed, and can effectively plan the picking sequence of multiple crabapples on the tree.

(2) To avoid collisions between the robotic arm and the tree branches during picking progress, which may cause damage to the robotic arm and the trees, the APF algorithm and the RRT algorithm were combined and a gravitational field was introduced to enhance the directional guidance of the RRT algorithm path search. Compared to the original RRT algorithm, it can be concluded that the improved RRT algorithm has fewer turning points and faster convergence speed, and can achieve obstacle avoidance picking path planning for the robotic arm.

(3) To verify the effectiveness and feasibility of the algorithm proposed in this article, a picking test platform was constructed to conduct multiple groups of picking tests on clustered crabapples (1 to 6 clusters) on an artificial simulation crabapple tree. The test results show that the average recognizing success rate is 95.83%, the average positioning success rate is 93.75%, and the average picking success rate is 89.58%. Moreover, there are no collisions between the robotic arm and the main branches of the tree during the picking process, and the robotic arm can pick the crabapples according to the planned picking sequence with no collision, meeting the actual picking requirements and achieving the goal of picking.

Author Contributions

Writing-review editing, funding acquisition, and methodology, L.W.; software, data curation, writing-original draft, L.Y.; formal analysis, data curation, X.M.; methodology, conceptualization, project administration, S.L.; software, investigation, Q.W.; data curation, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Special Fund Project of Basic Scientific Research Business Expenses of Central Public Welfare Scientific Research Institutes: CAFYBB2022MB002.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

L.W., L.Y., and X.M. contributed equally to this work. The authors are grateful for financial support from the Special Fund Project of Basic Scientific Research Business Expenses of Central Public Welfare Scientific Research Institutes [grant number CAFYBB2022MB002].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Liu, C.; Gong, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y. Current Status and Development Trends of Agricultural Robots. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2022, 53, 1–22+55. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, J.; Ren, M.; Wang, C. Analysis of antioxidant components and activities of sand fruit juice during processing. Journal of Oiqihar University(Natural Science Edition) 2023, 39, 76–80+94. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Shen, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, G.; Wang, C. Effects of Slice Thickness and Hot-air Temperature on Drying Characteristics, Physico-chemical Properties and Antioxidants of Mumsasiatica Nakai Slices. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2024, 45, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Sun, T.; Yuan, L.; Wu, L. Design and experimental research of pneumatic soft picking manipulator. Chinese Journal of Engineering Design 2022, 29, 684–694. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Yan, J.; Zhang, F.; Gou, Y.; Xu, Y. Research progress of vegetable picking robot and its key technologies. Journal of Chinese Agricultural Mechanization 2023, 44, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Q. Review of path planning algorithms for picking manipulator. Journal of Chinese Agricultural Mechanization 2023, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtser, P.; Edan, Y. Planning the sequence of tasks for harvesting robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2020, 131, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Xie, F. Task planning of multi-arm harvesting robots for high-density dwarf orchards. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2021, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Duan, J.L.; Yang, Z.; Zou, X.J.; Chen, M.Y.; Zhang, S. Collision-free motion planning for the litchi-picking robot. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 185, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.M.; Zou, X.J.; Jia, C.Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Zeng, Z.Q. RRT-based path planning for an intelligent litchi-picking manipulator. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 156, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tian, R.; Wang, X. Research on obstacle avoidance motion planning method of manipulator in complex multi scene. Journal of Northwestern Polytechnical University 2023, 41, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Ning, N.; Song, C.; Ning, W. Path Planning of Mobile Robots Based on Ant Colony Algorithm and Artificial Potential Field Algorithm. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2023, 54, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Ding, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H. Unmanned sailboat path planning based on improved adaptive ant colony algorithm. Journal of Harbin Engineering University 2023, 44, 969–976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.S.; Luo, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.Q. Path planning of a 6-DOF measuring robot with a direction guidance RRT method. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, H.; Andriukaitis, D.; Li, Y.B.; Królczyk, G.; Li, Z.X. Intelligent path planning by an improved RRT algorithm with dual grid map. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 88, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.T.; Dai, J.Y.; Jiang, B.P.; Karimi, H.R. Robot path planning based on artificial potential field with deterministic annealing. Isa Transactions 2023, 138, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Hao, W.; Wu, Y.; Sun, C. Research on Robot Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. Computer simulation 2023, 40, 431–436+442. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).