1. Introduction

The livestock sector is under constant pressure to meet the growing demand of protein rich feedstuffs and to find potential alternative sources to replace the conventional protein sources, particularly fish meal and soybean meal in animal feeds [

1,

2]. Insect protein is one of the alternatives, which can be produced from insects, or from their larvae. Insect meals can meet all the sustainability requirements, since several organic wastes can be transformed into high quality protein. Several insects can be produced, but at industrial scale black soldier fly and lesser mealworm are dominants [

3].

Insect proteins can be used successfully mainly in monogastric animal nutrition, because their amino acid composition is optimal to substitute soybean meal or fishmeal without compromising the production traits. However, the chitin, protein and fat content, the amino acid and fatty acid composition of the different insect meals is not constant and changes according to the substrate, used for the insect production.

Several studies have been published on the use of insect proteins in poultry feeds as an alternative protein source [

1,

4,

5]. Comparing the protein content of the different insect meals, it ranges between 41 and 68%. The lowest value belongs to the black soldier fly, while the highest to the lesser mealworm larvae [

3]. There are also huge differences in the digestible amino acid contents of the different meals. The average apparent ileal amino acid digestibility of yellow mealworm (

Tenebrio molitor, TM) and Black soldier fly (

Hermetia illucens, HI) larvae were 86 and 68% respectively. The fat content of the insect meals is also high, so it is an important energy source as well. The crude fat content of the above-mentioned TM and HM meals were 28.0 and 34.3 %, their AMEn contents 24.4 and 23.8 MJ/kg respectively [

6]. In some cases, the meals are defatted. These forms contain less energy, but the protein and amino acid contents are higher.

Most of the studies have been done with broiler chickens, using TM and HI meals. Beside the metabolizable energy and amino acid digestibility studies the effects of insect meals on the production parameters, gut bacteriota, meat quality was also evaluated [

1,

7,

8]. Less results are available on laying hens. Some studies have proven that the egg mass was positively affected by the insect meal diets [

9,

10]. The effect on production parameters is contradictory in several cases. In Al-Quazzaz study it was proved that the feed conversion ratio, egg weight, shell thickness, shell weight, egg yolk colour, fertility, and egg mass were negatively affected by 5 and 10% insect meal treatments [

9]. But in Bovera et al. [

10] research egg weight, feed intake and conversion rate were not affected by both 7.3 and 14.6% insect meal in the diet. But the dry matter, organic matter, and crude protein digestibility were lower for the 14.6% insect meal diet, the research hypothesizes that it is due to chitin. In the trial of Secci [

11] significant improvement was observed in the appearance, texture, taste, and acceptance of eggs when the hens were fed 5%

H. illucens (HI) meal. In comparison with the soybean meal-based diet the insect meal treatment was associated with redder yolks (red index 5.63 v. 1.36) richer in γ-tocopherol (4.0 against 2.4 mg/kg), lutein (8.6 against 4.9 mg/kg), β-carotene (0.33 against 0.19 mg/kg) and total carotenoids (15 against 10.5 mg/kg). Finally, feeding insect meal resulted 11% decrease in the yolks cholesterol content in comparison with the soybean meal-based control diet.

The Lesser mealworm (

Alphitobius diaperinus, AD) is known as a common insect pest in commercial poultry farms [

12], but its larvae has also big potential as feed or food because this larva contains the highest protein (58.0-64.8%) and fat (13.4 – 29.0%) content [

13]. Some positive results on its nutritional value and potential usability in farm animal production have been published, but the investigation of it is not so advanced [

14]. Rumbos (2019) made the first review on AD, summarizing the significant findings on its biology, nutritive value, on the public concerns that arise from its utilization as feed, focusing mainly on the aquacultural aspects. Based on study of Kurecka et al. [

14] the harvest of AD larvae and pupae provides high quantity quality insect protein with a low chitin level in all investigated instars. Furthermore, the quality of its larvae protein is similar or superior to that of most other edible insect species. Richli et al [

13] used AD meal (ADM) in replacing soybean meal at 0, 3, 6 and 9% in the diets of fattening pigs between 26 and 86 kg live weight. AD meal caused no significant differences in the fed intake, weight gain or feed conversion of the animals. The only significant change was that ADM increased the polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) content in the backfat. In a recent study with broiler chicken, soybean meal was replaced by 4, 8 and 12% AD and HI larvae meals. Beside the production traits some blood parameters, gut morphometry and meat quality of the chickens were evaluated. Both insect meals at all inclusion rates improved the examined parameters except meat pH, drip loss and shear force [

15].

As far the authors know there are no available research results on AD in laying hen nutrition. Since the fatty acid composition of ADM is different from that of HI meal, beside the production parameters, the egg quality has also been evaluated in detail. Further aim of this study was to use ADM at the potential highest inclusion rates.

2. Materials and Methods

Birds and Experimental Design

A feeding trial was carried out at the experimental farm of the Department of Animal Nutrition and Nutritional Physiology, Georgikon Faculty, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The trial started on 7th November 2023, finished on 22nd December 2023 and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Animal Welfare Committee, Georgikon Campus, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences). A total of 48, 35-week-old Tetra SL laying hens were purchased from a commercial company (Fuchs Ltd., Bakonygyepes, Hungary) and placed into individual wire cages, totalling a surface area of 1056 cm2. The cages were equipped with nipple drinkers and specific individual feeders that presented feed spoilage. The hens got their previous diets in the first two days and the change to the experimental diets happened gradually during a 3-day long adaptation period. The feed and water were available ad libitum. The daily dark period was 8 hours long. The room temperature and humidity were set to 20°C and 50% respectively. The ambient temperature was between 0 and 5°C at that time, so the air movement of the room was set to 130 m3/hour. All the environmental conditions were computer controlled.

Besides a control diet (C), two diets were used, containing the larvae meal of Alphitobius diaperinus at 10% (ADM10) and 15% (ADM15). All diets were fed in 16 replicates. The source of the ADM was the food grade product of AdalbaPro (Ynsect NL processing b.v. Netherlands) and delivered by a Swiss company (RethinkResource GmbH, Zurich, Switzerland). According to the results of our previous digestibility trial the AMEn content of the product at 10 and 15% is 23 MJ/kg. Its standardized ileal digestible (SID) lysine, methionine, threonine, valine, isoleucine and arginine contents are 34.8, 8.9, 18.1, 28.5, 23.1 and 31.5 g/kg. These values have been used in the formulations of the isocaloric and isonitrogenous diets. The SID amino acid and the metabolizable energy contents of the other feedstuffs were evaluated by NIR [

16]. The SID amino acid composition and the AMEn content of ADM have been determined in a previous trial. The composition and the measured nutrient content of the experimental diets is shown in

Table 1. It can be seen, that using the insect meal substituted mainly soybean meal, increased the ratio of corn and decreased the amount of sunflower oil. In order to compose the ADM containing diets isocaloric and isonitrogenous with the control, cellulose was used as a diluting component. The nutrient content of the diet was defined according to the requirements of the hens at that age and production intensity, using the management guide of the breeder company [

17].

Due to the high energy content of ADM, its maximum inclusion rate was 15%. This ratio already increased the ME content of the diet by 0.4 MJ/kg, compared with the two other treatments. All the three diets were calculated as isonitrogenous. The ileal digestible amino acid contents of the diets were not identical, but in all cases covered the needs of hens.

Sampling, Measurements, Calculations

The feeding was ad libitum. The daily amount of feed was 140 g (70 g in the morning and 70 g in the afternoon), and the remnant feed was measured back daily. The egg production of all hens was measured daily and from these data the weekly egg production and feed conversion ratio (FCR) calculated. The production traits were calculated also for the entire 6-week-long period.

Every week one egg from each animal was investigated for different quality parameters by a digital egg tester (DET6500, Nabel Co., Kyoto 601-8444 Japan)). The following parameters have been measured: egg weight, eggshell strength, albumen height, Haugh unit, yolk colour, yolk height, yolk diameter, yolk index, and eggshell thickness. Yolk index is the quotient of yolk height and yolk diameter, which is also a marker of egg freshness like the Haugh unit.

At the end of the trial the fat content and fatty acid composition of egg yolk samples were also measured. The crude fat content was determined with the Randall extraction method (ISO 11085:2015 B), while the fatty acid composition by gas chromatography (Thermo Finnigan Trace 2000) according to the ISO 12966-4:2015 procedure (column type: Omegawax 320, 30m x 0,32mm x 0.25 µm; Supelco).

The eggs from the last day were stored at 4°C and from these eggs an aromatic profile analysis has also been done. Eggs from each treatment were sent to the laboratory of ADEXGO Ltd. in Budapest. The so called “electronic nose” analysis was carried out with an Alpha MOS Heracles NEO equipment (Alphy MOS, Toulouse, France). It is an ultra-quick gas chromatograph that automatically analyse the volatile components from the air, above liquid and solid samples. The raw eggs were homogenized and 2.0±0.1 g sample was measured into 20 ml headspace tubes. After 10-minute-long heat treatments at 50°C 5 ml gas sample was taken and injected into the analyser. For the analysis of the chromatograms AlphaSoft data evaluating software was used. The interval of the alkane length was between C6 and C16. The gases were identified according to the retention time (Kováts retention index) and their intensity was calculated from the area of the peaks. The molecules were identified from the AroChemBase database. The smell profile databases were further analysed by principal component analysis (PCA). PCA is used widely in many fields, such as population genetics or microbiota evaluation to reduce the dimensionality of large data sets. Three replicates were measured from each egg sample.

The egg sensory characteristics of boiled eggs were also evaluated by 11 volunteers of the university staff. The eggs were separated (individual boxes and permanent marked signs) from each other, according to the feed treatments (control, ADM10 and ADM15). Before boiling the eggs were packed into coded cotton nets. All the eggs were put into the boiling water at the same time. The boiling took 10 minutes and after that the eggs were cooled until the egg surface reached the tap water temperature. After taking off the eggshell, the eggs were cut in half and served on coded (A-B-C) plates to the participants. The sensory analysis was organized and conducted according to ISO 4121:1987. Before the test started, the participants were trained how to use the unstructured hedonistic scale questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

The feed intake, egg production, laying rate, FCR and egg quality parameters were compared with two-way ANOVA, with the dietary treatments and the time as main factors, using the software package SPSS 29.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The results on volatile compounds of the electronic nose sensors were analysed by principal component analysis (PCA).

3. Results

The measured nutrient content of the test product and experimental diets is shown in

Table 3. The larvae meal used in this trial (ADM) was rich both in crude protein and crude fat. It can be seen that there were no big differences between the diets in the main measured nutrient categories and amino acid contents. The crude fat content of the ADM containing diets was 1.0 – 2.4% lower and their starch content 3.4 – 4.4% higher than the control. Among the first limiting amino acids, the isoleucine content of the ADM diets was lower, however the 0.72 and 0.73 % isoleucine in diets ADM10 and ADM15 respectively still covered the requirement of the hybrid, which is 0.67% in the period between 19-45 weeks [

18].

The fatty acid composition of the ADM is shown in

Table 4. This insect larvae meal contained only low amounts of lauric acid, compared with the lauric acid content of the black soldier fly larvae. The dominant fatty acids are palmitic acid, oleic acid and linoleic acid. This fatty acid profile is close to those of animal fats, but ADM contains less stearic and oleic acid, while more linoleic and α-linolenic acid.

The initial and final body weight and the weight gain of hens did not change during the trial (

Table 5.) The production traits are summarized in

Table 6.

The egg production of the hens was high. After the first week adaptation the laying intensity was almost in all groups above 95%. The weekly egg production showed some fluctuation among the weeks, but the feed intake, FCR, egg production % and average egg weight were not affected. The dietary treatments resulted significant differences only in the egg weight and the egg production. In the third week the egg weight and egg production of the ADM15 hens was significantly lower than that of the control. In the last week, the egg weight decreased again significantly in the ADM15 treatment, and this trend was true also for the whole production. On average, the egg weight was 2.3% and 4.2% lower in the ADM10 and ADM15 groups respectively.

The egg quality parameters and results of the two factorial evaluations are summarized in

Table 7. As expected, time had more impact on the different measured parameters. The change in albumen height (Ht), Haugh unit (Hu), yolk index (Yi) and eggshell thickness (Thk) showed no tendency among the weeks. Although a drop was found in the 4th week in yolk colour (Yc), this parameter showed increasing tendency with the time and was significantly higher in the two last week than at the beginning. The reason for the significant diet x time interaction in yolk colour was, that this parameter was not changed in the control group but increased with the time in both ADM treatments. The dietary treatments affected only the egg weight in a similar way as it was mentioned previously in the case of production traits. Feeding ADM at both 10 and 15% resulted significantly lower egg weight compared with the eggs of the control group.

The insect meal did not modify the fat content of the egg yolk (

Table 8). The fatty acid composition, however, was affected by the dietary treatments. Feeding ADM increased the lauric, stearic and linoleic acid and decreased the oleic and α-linolenic acid concentrations of the yolk. The results are not fully in line with the fatty acid composition of the diets. The main fatty acid source in the control diet was corn oil, containing more oleic, stearic, but less α-linoleic acid than the fat of ADM. From this aspect the results on α-linoleic acid are in contrast with the expectations. Although significant, but only marginal differences could be found in the ratio of the long chain omega 3 fatty acids.

Flavour and smell of eggs are determined by the quality and quantity of volatile compounds [

19]. Some molecules can modify the acceptance of eggs negatively, others could make eggs tastier [

20]. For the identification of volatile compounds (VOCs) in food the electronic nose is one of the often-utilized instrumental analytical techniques [

21].

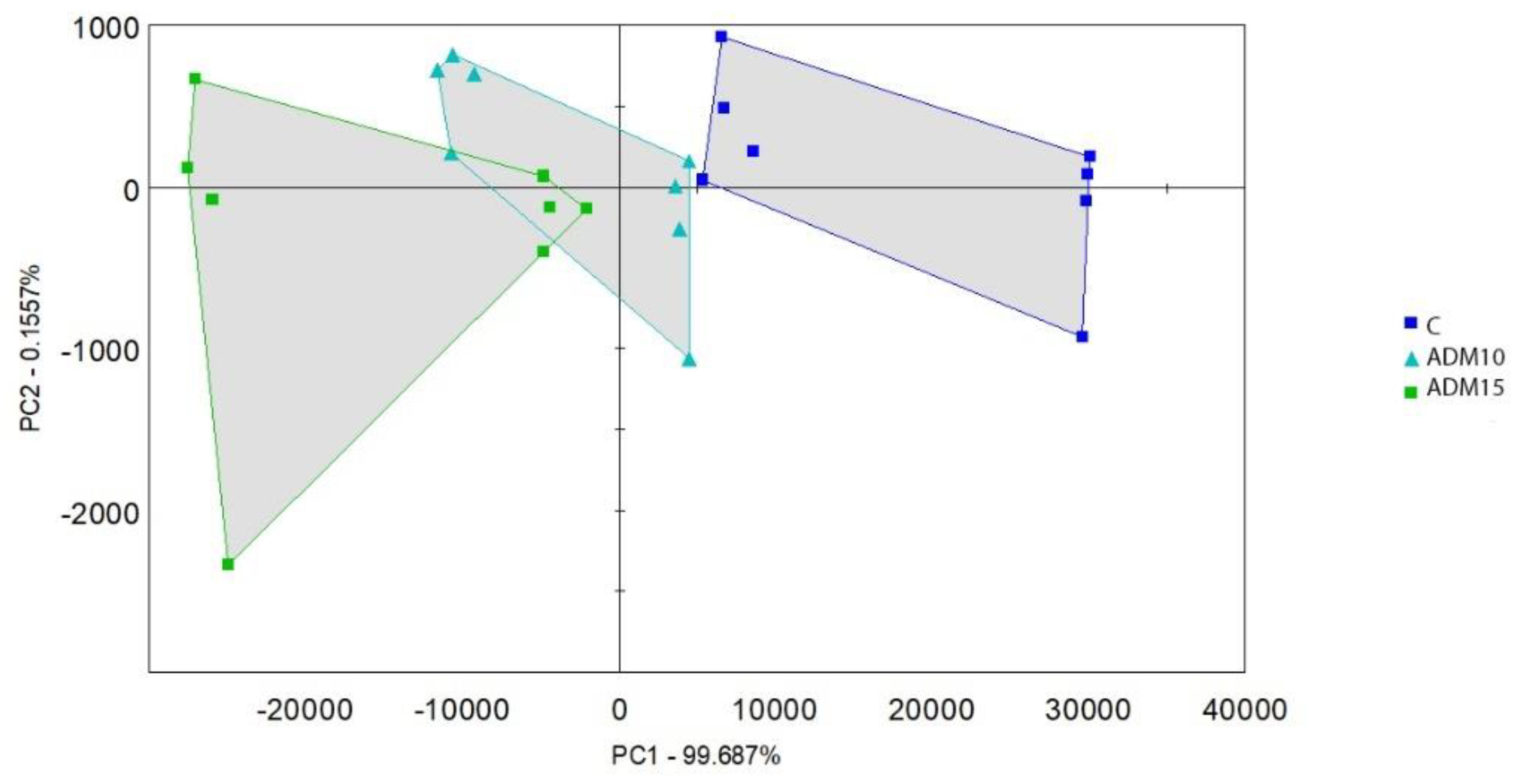

Interpreting the volatile compounds of the control and ADM containing diets principal component analysis was carried out (

Figure 1.). Dietary treatments after 50°C incubation resulted clear separation. Even the two ADM treatments resulted in different compound structure.

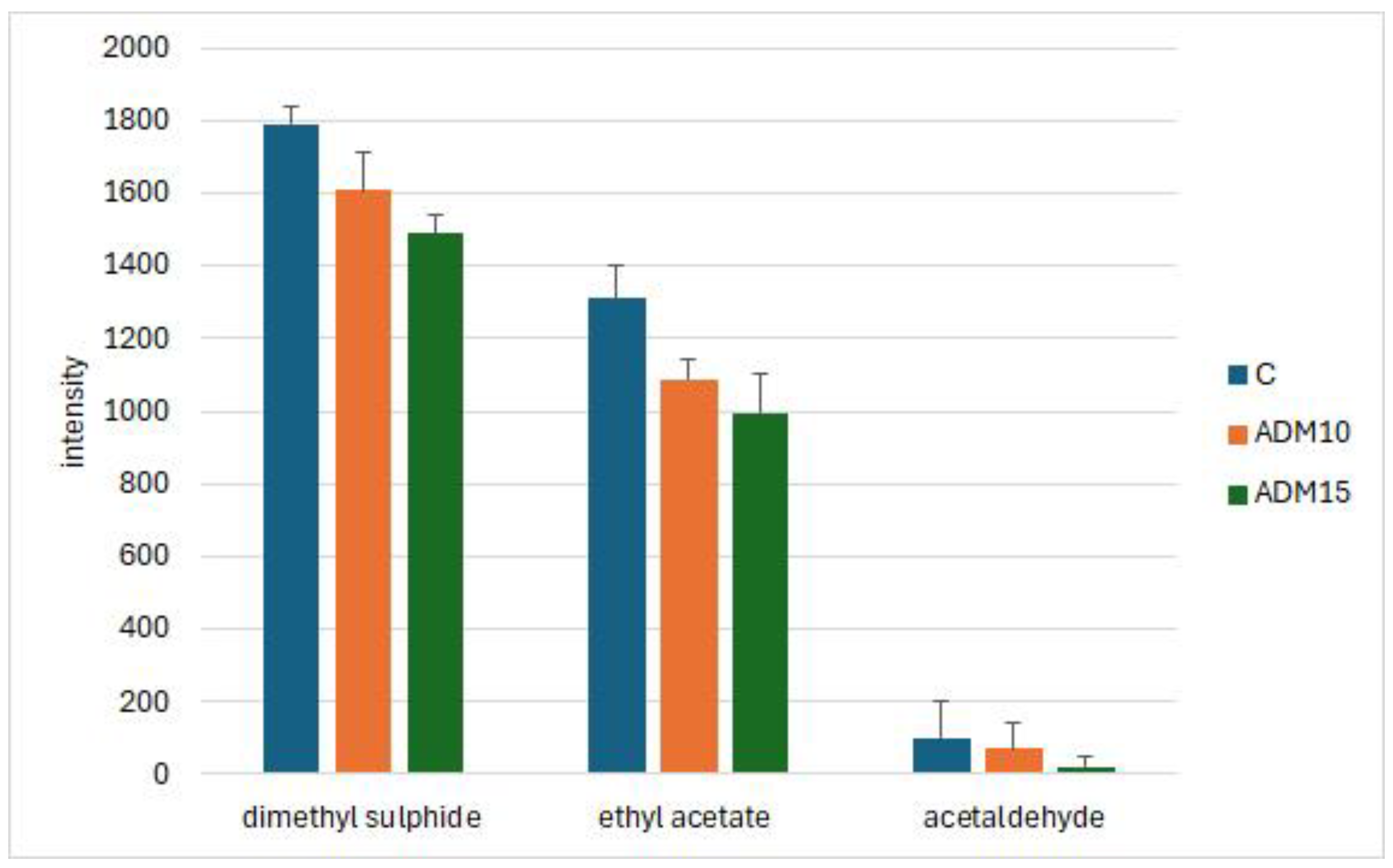

Comparing the intensity of some relevant odour modifying molecules, ADM diets reduced the intensity of dimethyl sulphide, ethyl acetate and acetaldehyde compared with the control eggs (

Figure 2.).

The organoleptic evaluation results are summarized in

Table 9. Only the yolk colour and its preference opinion of the volunteers resulted significantly different results. Both ADM containing treatments resulted higher scores. The overall impression was also better of the ADM eggs, but these differences were not significant.

4. Discussion

Alphitobius diaperinus is a widespread insect, which is generally considered as a pest [

22,

23]. Until now it was known as a source of problems in poultry farms and henneries, where both larvae and adults occur frequently [

24,

25] and is a potential vector for various avian pathogens (Rumbos et al., 2019). However, nowadays AD belongs to those insects that have the biggest potential for insect meal production and is listed as one of the eight insect species that are so far registered for use in the EU [

26]. Only a few studies are known about its ability to be fed with poultry species and most of them were focusing on black soldier fly [

27]. The research results on insect meals are often contradictory, depending on the insect type, the substrate used for the production of larvae, the incorporation rate of the meals and also the species and age of the animals. While Al-Hazzaz [

9] found for example that the 5 and 10% insect meal treatments had a negative effect on the feed conversion ratio of broiler chickens. On the other hand, in the study of Sajjad [

15] found that the incorporation both 12% AD and HI meals into broiler diets significantly (P<0.05) increased the final body weight, average daily weight gain and improved the feed conversion ratio (FCR) of broiler chickens. The daily feed intake did not show a significant difference (P>0.05) among all the dietary treatments. No layer trial results have been published with ADM yet. The results with HI cannot be adapted to ADM because the differences in the protein content, amino acid and fatty acid composition of the two products. In our experiment the maximal potential inclusion rates were used with the criteria, that the experimental diets should be isocaloric and isonitrogenous. Under these criteria maximum 15% incorporation of ADM was possible.

Similarly, to Al-Hazzaz's results, feeding 10 and 15% insect protein meal diet also resulted smaller egg weight, and changed the fatty acid composition of the egg yolk, without effect on the feed intake, live weight and FCR of hens.

Maurer et al. [

28] obtained the same result in an experiment with a black soldier fly where the soybean cake substitution by either partially or fully defatted larvae meal (12 and 24%) in hen diets had no adverse effects on the feed intake.

In our present trial however, ADM was depressive on the weekly egg production and average egg weight. The reason for this could be the difference in the fatty acid composition between the control and ADM containing diets. The fat of ADM contains less linoleic acid and more palmitic acid in comparison with the corn oil, the dominant fat source of the control feed. It is well known that laying hens need higher amount of linoleic acid for their reproduction. The Tetra SL layers of this trial had 1.8% linoleic acid requirements between weeks 19 and 45. According to the calculation the fatty acid content of the experimental diets from the ingredients (AminDat 6.3) the linoleic acid content of the ADM10 and ADM15 diets were 1.53 and 1.69% respectively. The control feed contained 3.2% linoleic acid.

Generally, insects contain a variety of polyunsaturated, saturated, and monounsaturated fatty acids. The dominant saturated fatty acid is palmitic acid (C16:0), whereas stearic acid is present in varying amounts (C18:0). The dominant monounsaturated fatty acid is oleic acid (C18:1). Although the main influencing factor of content of micronutrients and vitamins is insects varies between species and orders, as well as season and the meal given [

29]. Rumbos et al. (2019) evaluated the lipid composition of

A. diaperinus larvae. In the lipid fraction the saturated (SFA) and monounsaturated (MUFA) fatty acids were dominating and to a lesser extent polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA). Palmitic acid (16:0) (15–26% of total fatty acids) and oleic acid (18:1n−9) (20–44%) were the most dominant saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, respectively. The PUFA contained mainly linoleic acid (18:2n−6) with very low levels of α-linolenic acid (18:3n−3) and lack of any of the n−3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) such as 20:5n−3 and 22:6n−3. The authors concluded that the overall fatty acid profile of ADM cannot be evaluated as an ideal one from human nutritional aspects. Our measurements agreed with these values.

Feeding the ADM containing diets resulted slight change in the yolk fatty acid composition. Lauric acid could be measured only from the ADM eggs. Beside that oleic acid concentration showed slight but significant decrease, while that of linoleic acid significant increase in the diets contained ADM. The increase in linoleic acid is hardly to explain, since ADM fat contained less from this fatty acid.

In some studies egg weight, shell thickness, shell weight, egg yolk colour, fertility, and egg mass were negatively affected by 5 and 10% insect meal treatments [

9]. The chitin content of insect meals can also cause negative effects on the egg quality [

9,

30]. According to the finding of Secci [

11] some metabolic ways, such as the accumulation of carotenoid and the desaturase/elongase activities can slightly inhibited by dietary inclusion of insect meals. In this trial the traditional egg quality parameters were not affected by the treatments, except egg weight, that was mentioned already at the production traits.

The results of the volatile compound evaluation help to differentiate get more understanding what kind of compounds could be present is the foods and feeds. According to the results of the PCA, feeding ADM with the hens results specific volatile compound profile of the eggs and using electronic nose the insect meal eggs can be identified and differentiate. After 50°C incubation the concentration of dimethyl sulphide and ethyl acetate were the determinant volatile compounds of fresh eggs. Both intensities showed lowering tendency when the ADM containing diets were fed. Dimethyl sulphide and the other sulphur compounds are the end products of proteins and amino acid degradations [

31]. Compared the volatile compound structure of different poultry species. In their studies benzothiazole was the most common sulphuric molecule. Dimethyl sulphide has a smell similar to that of mercaptans. In low amount can be desirable for some beer types, and can be found in cooked sweet corn, sour cabbage or tomato sauce, but at higher concentration cause off-flavour [

32,

33,

34]. Brown et al. [

35] found a correlation between the presence of dimethyl sulphide and the perception of a slightly sour odour in the egg samples. They concluded that measurement of dimethyl sulphide may serve as an objective method for determining acceptability of egg products for human consumption.

Ethyl acetate is usually the dominant volatile ester in the eggs of the laying hens [

31]. It is used also as a food additive and makes fruity, fragrant smell and taste. Its presence at low concentration can be positive, resulting sweet smell and taste. At higher concentration cause acetone like unfavourable smell and taste [

36,

37]. Aldehydes were identified at high concentration in heat treated eggs [

19,

38]. The intensity of acetaldehyde was low in our case, but ADM resulted also lowering tendency of this molecule. Aldehydes are mainly the degradation compounds of unsaturated fatty acids. So, the antioxidant properties of insect meals could protect the unsaturated fatty acids, but it could not be stated from the results of this study.

The electronic-nose results had consequences also on the results of tasting evaluation of the boiled eggs by the volunteers. The main average evaluation scores were by 2.0 and 2.6 higher for the eggs for ADM10 and ADM15. The egg yolk colour was the only parameter, where the evaluation of the volunteers resulted significant differences. The egg yolk colour evaluation was about 20% higher for the insect meal eggs. This result agrees with others, who found also more yellowish egg yolk due to the insect meal feeding [

9,

11].

5. Conclusion

Insect meals are valuable feeds with high protein and fat content. The product, used in this trial (ADM) contained 58% crude protein and 28% crude fat. Its maximum incorporation rate into the diets of laying hens is about 15%, otherwise the energy content of the diets increases above the requirement of the hens. At 10 and 15% ADM failed to modify the production parameters, except egg weight, which was decreased significantly at both inclusion rates of ADM. The reason for it is not clear, but the differences in the fatty acid composition of ADM and corn oil could be the reason. Except egg weight the other routinely measured egg quality parameters (shell strength, shell thickness, Haugh unit, yolk colour, yolk height, yolk diameter, yolk index) are not affected if insect meal is fed. The fat content of yolk was not affected by the treatments, but the ratio of some fatty acids was changed as the effect of ADM: These changes were not in all cases in line with the fatty acid compositions of the diets. Linoleic acid was such an example. The volatile aroma profile structure of the ADM eggs is different from that of the control eggs. It could be also the reason that the organoleptic evaluation of boiled eggs by volunteers resulted preference towards the ADM eggs. In this evaluation the egg yolk of ADM eggs was significantly higher ranked. In summary insect larvae meals can be used successfully in the nutrition of laying hens. Its optimal inclusion rate depends on the price, protein and fat content of the product.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.; F.W.; methodology, T.Cs. and L. W. formal analysis, N.S. and K.D.; investigation, T.Cs.; N.S.; H.B.; B.K.; J.G.K.; K.G.T. and L.P.; data curation, L.W.; T.Cs.; N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Cs.; N.S. and K.D. writing—review and editing, N.S. and K.D.; visualization, N.S. and K.D.; supervision, K.D.; project administration, F.W. and K.D.; funding acquisition, F.W. and K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

„This work was supported by the Flagship Research Groups Programme of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the RethinkResource GmbH.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Animal Welfare Committee, Georgikon Campus, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences) under the license number MÁB-2/2024.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Flagship Research Groups Programme of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences and by the EKÖP-MATE/2024/25/k university research scholarship programme of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the national research, development and innovation fund.”

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Waithaka, M.K.; Osuga, I.M.; Kabuage, L.W.; Subramanian, S.; Muriithi, B.; Wachira, A.M.; Tanga, C.M. Evaluating the Growth and Cost–Benefit Analysis of Feeding Improved Indigenous Chicken with Diets Containing Black Soldier Fly Larva Meal. Frontiers in Insect Science 2022, 2, doi:10.3389/finsc.2022.933571. [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A.; Dicke, M.; van Loon, J.J.A. Insects to Feed the World. J Insects Food Feed 2015, 1, 3–5, doi:10.3920/JIFF2015.x002. [CrossRef]

- Mézes, M. A Rovarfehérje, Mint a Fehérjeellátás Új Alternatívája. Állattenyésztés és Takarmányozás 2018, 67, 287–296.

- Vasileska, A.; Rechkoska, G. Global and Regional Food Consumption Patterns and Trends. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2012, 44, 363–369, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.040. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, U.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Lin, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Qi, G. Insect Meal as a Feed Ingredient for Poultry. Anim Biosci 2022, 35, 332–346, doi:10.5713/ab.21.0435. [CrossRef]

- De Marco, M.; Martínez, S.; Hernandez, F.; Madrid, J.; Gai, F.; Rotolo, L.; Belforti, M.; Bergero, D.; Katz, H.; Dabbou, S.; et al. Nutritional Value of Two Insect Larval Meals (Tenebrio Molitor and Hermetia Illucens) for Broiler Chickens: Apparent Nutrient Digestibility, Apparent Ileal Amino Acid Digestibility and Apparent Metabolizable Energy. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2015, 209, 211–218, doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.08.006. [CrossRef]

- Hartinger, K.; Fröschl, K.; Ebbing, M.A.; Bruschek-Pfleger, B.; Schedle, K.; Schwarz, C.; Gierus, M. Suitability of Hermetia Illucens Larvae Meal and Fat in Broiler Diets: Effects on Animal Performance, Apparent Ileal Digestibility, Gut Histology, and Microbial Metabolites. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2022, 13, 50, doi:10.1186/s40104-022-00701-7. [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.; Abdel-Wareth, A.A.A.; Hiramatsu, K.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Luza, D.; Lohakare, J. Flight toward Sustainability in Poultry Nutrition with Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Animals 2024, 14, 510, doi:10.3390/ani14030510. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qazzaz, M.F.A.; Ismail, D.; Akit, H.; Idris, L.H. Effect of Using Insect Larvae Meal as a Complete Protein Source on Quality and Productivity Characteristics of Laying Hens. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 2016, 45, 518–523, doi:10.1590/s1806-92902016000900003. [CrossRef]

- Bovera, F.; Loponte, R.; Pero, M.E.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Calabrò, S.; Musco, N.; Vassalotti, G.; Panettieri, V.; Lombardi, P.; Piccolo, G.; et al. Laying Performance, Blood Profiles, Nutrient Digestibility and Inner Organs Traits of Hens Fed an Insect Meal from Hermetia Illucens Larvae. Res Vet Sci 2018, 120, 86–93, doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2018.09.006. [CrossRef]

- Secci, G.; Bovera, F.; Nizza, S.; Baronti, N.; Gasco, L.; Conte, G.; Serra, A.; Bonelli, A.; Parisi, G. Quality of Eggs from Lohmann Brown Classic Laying Hens Fed Black Soldier Fly Meal as Substitute for Soya Bean. Animal 2018, 12, 2191–2197, doi:10.1017/S1751731117003603. [CrossRef]

- Rumbos, C.I.; Karapanagiotidis, I.T.; Mente, E.; Athanassiou, C.G. The Lesser Mealworm Alphitobius Diaperinus : A Noxious Pest or a Promising Nutrient Source? Rev Aquac 2019, 11, 1418–1437, doi:10.1111/raq.12300. [CrossRef]

- Müller Richli, M.; Weinlaender, F.; Wallner, M.; Pöllinger-Zierler, B.; Kern, J.; Scheeder, M.R.L. Effect of Feeding Alphitobius Diaperinus Meal on Fattening Performance and Meat Quality of Growing-Finishing Pigs. J Appl Anim Res 2023, 51, 204–211, doi:10.1080/09712119.2023.2176311. [CrossRef]

- Kurečka, M.; Kulma, M.; Petříčková, D.; Plachý, V.; Kouřimská, L. Larvae and Pupae of Alphitobius Diaperinus as Promising Protein Alternatives. European Food Research and Technology 2021, 247, 2527–2532, doi:10.1007/s00217-021-03807-w. [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Binyameen, M.; Sajjad, A.; Sarmad, M.; Abbasi, A.; Khan, E.U.; Haq, I.U.; Subhan, M.; Alhimaidi, A.R.; Amran, R.A. Replacing Soybean Meal with Lesser Mealworm Alphitobius Diaperinus Improves Broiler Productive Performances, Haematology, Intestinal Morphology and Meat Quality. J Insects Food Feed 2024, 1–22, doi:10.1163/23524588-00001190. [CrossRef]

- Evonik Industries AG AminoDat 6.1; Hanau-Wolfgang, Germany, 2023;

- Tetra Ltd. Management Guide.; 2022;

- Tetra Ltd. Nutritional Guide.; 2022;

- Matiella, J.E.; Hsieh, T.C. -Y. Volatile Compounds in Scrambled Eggs. J Food Sci 1991, 56, 387–390, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb05286.x. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bachir, M. Improvement of Microbiological Quality of Hen Egg Powder Using Gamma Irradiation. International Journal of Food Studies 2020, 9, doi:10.7455/ijfs/9.SI.2020.a6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Sun, B. Recent Progress in Food Flavor Analysis Using Gas Chromatography–Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC–IMS). Food Chem 2020, 315, 126158, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126158. [CrossRef]

- Hosen, M.; Khan, A.R.; Hossain, M. Growth and Development of the Lesser Mealworm, Alphitobius Diaperinus (Panzer) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) on Cereal Flours. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2004, 7, 1505–1508.

- Spilman, T.J. Darkling Beetles (Tenebrionidae, Coleoptera). In Insect and Mite Pests in Food; Gorham JR, Ed.; United States Department of Agriculture: WashingtonDC, 1991; Vol. 655, pp. 185–214.

- Francisco, O.; do Prado, A.P. Characterization of the Larval Stages of Alphitobius Diaperinus (Panzer) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Using Head Capsule Width. Rev Bras Biol 2001, 61, 125–131.

- Lambkin, T.A. Investigations into the Management of the Darkling Beetle; Kingston, Australia, 2001;

- Müller Richli, M.; Weinlaender, F.; Wallner, M.; Pöllinger-Zierler, B.; Kern, J.; Scheeder, M.R.L. Effect of Feeding Alphitobius Diaperinus Meal on Fattening Performance and Meat Quality of Growing-Finishing Pigs. J Appl Anim Res 2023, 51, 204–211, doi:10.1080/09712119.2023.2176311. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.; Shafi, M.; Alghamdi, W.; Abdelnour, S.; Shehata, A.; Noreldin, A.; Ashour, E.; Swelum, A.; Al-Sagan, A.; Alkhateeb, M.; et al. Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) Meal as a Promising Feed Ingredient for Poultry: A Comprehensive Review. Agriculture 2020, 10, 339, doi:10.3390/agriculture10080339. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, V.; Holinger, M.; Amsler, Z.; Früh, B.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Stamer, A.; Leiber, F. Replacement of Soybean Cake by Hermetia Illucens Meal in Diets for Layers. J Insects Food Feed 2016, 2, 83–90, doi:10.3920/JIFF2015.0071. [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.; Fitzpatrick, M.P.;; Dierenfeld, E.S. Nutrient Composition of Selected Whole Invertebrates. Zoo Biol 1998, 17, 123–134.

- Bovera, F.; Loponte, R.; Pero, M.E.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Calabrò, S.; Musco, N.; Vassalotti, G.; Panettieri, V.; Lombardi, P.; Piccolo, G.; et al. Laying Performance, Blood Profiles, Nutrient Digestibility and Inner Organs Traits of Hens Fed an Insect Meal from Hermetia Illucens Larvae. Res Vet Sci 2018, 120, 86–93, doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2018.09.006. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, G.; Jin, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, N.; Liu, C.; He, L. Discriminating Eggs from Different Poultry Species by Fatty Acids and Volatiles Profiling: Comparison of SPME-GC/MS, Electronic Nose, and Principal Component Analysis Method. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2014, 116, 1044–1053, doi:10.1002/ejlt.201400016. [CrossRef]

- Baldus, M.; Klie, R.; Biermann, M.; Kreuschner, P.; Hutzler, M.; Methner, F.-J. On the Behaviour of Dimethyl Sulfoxide in the Brewing Process and Its Role as Dimethyl Sulfide Precursor in Beer. BrewingScience 2018, 71, 1–11.

- Tenkrat, D.; Hlincik, T.; Prokes, O. Natural Gas Odorization; Primo.; Sciyo, 2010;

- Stafisso, A.; Marconi, O.; Perretti, G.; Fantozzi, P. Determination of Dimethyl Sulphide in Brewery Samples by Headspace Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (HS-GC/MS). Italian Journal of Food Science, 2011, 23, 19–27.

- Brown, M.L.; Holbrook, D.M.; Hoerning, E.F.; LegendreE, M.G.; ST. Angelo, A.J. Volatile Indicators of Deterioration in Liquid Egg Products. Poult Sci 1986, 65, 1925–1933, doi:10.3382/ps.0651925. [CrossRef]

- Ragazzo-Sanchez, J.A.; Chalier, P.; Chevalier-Lucia, D.; Calderon-Santoyo, M.; Ghommidh, C. Off-Flavours Detection in Alcoholic Beverages by Electronic Nose Coupled to GC. Sens Actuators B Chem 2009, 140, 29–34, doi:10.1016/j.snb.2009.02.061. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Trinh, C.T. Towards Renewable Flavors, Fragrances, and Beyond. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2020, 61, 168–180, doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2019.12.017. [CrossRef]

- Cerny, C.; Guntz, R. Evaluation of Potent Odorants in Heated Egg Yolk by Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis. European Food Research and Technology 2004, 219, 452–454, doi:10.1007/s00217-004-1000-8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).